The last American cruisers

The title seems a bit exaggerating, but there were indeed no new cruisers construction since 1907 and 1920. An immense gap explained by a strong focus on battleships, and on the other hand, the new US fleet destroyers which filled that scouting role to some degree. However towards the end of WW1, naval operations soon showed these fleet destroyers were limited in range, and needed also larger coordinating ships. Therefore, the admiralty requested a new scout cruiser/destroyer leader which became the Omaha class.

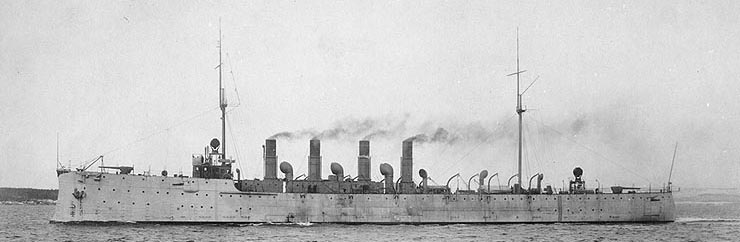

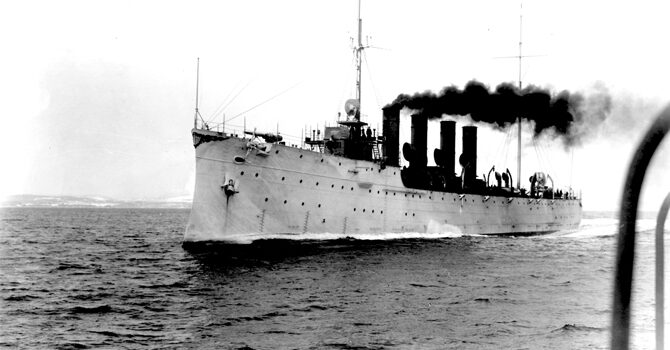

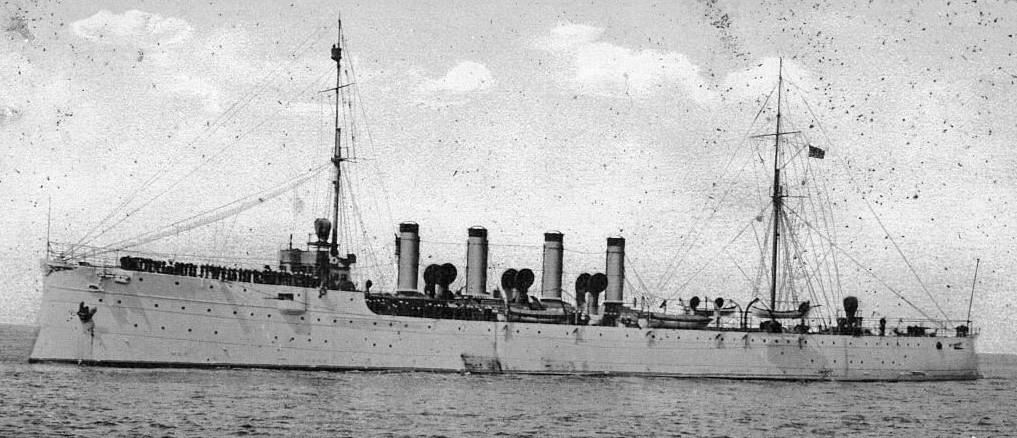

The three Chesters were the only USN ships ever to be denominated as “scout cruiser” (as CS or SCR). Their main characteristics were a high speed and little armor as well as reduced armament. Distant relatives, the first three Omaha-class ships were designated “scout cruisers” as ordered, but the classification system was soon revised and they were commissioned as “light cruisers” or “CL”.

In their service, USS Birmingham would be remembered as the world’s first ship worldwide to launch an airplane. This happened in 1910 and the feat was performed by pilot Eugene Ely, also later making the first landing in 1911, this time on the larger USS Pennsylvania, fitted with a platform. The three cruisers spent their prewar years patrolled the Caribbean, with some artillery support during interventions like the operation of Veracruz in 1914. After neutrality patrols, when the USA went at war, they maintained patrols and escorted convoys from 1917. After a life without notable incident they were quietly retired and decommissioned in 1921-1923, but kept in mothballs until sold for scrap to comply with London Naval Treaty limitations in 1930. By that time their active career had spanned barely 14 years.

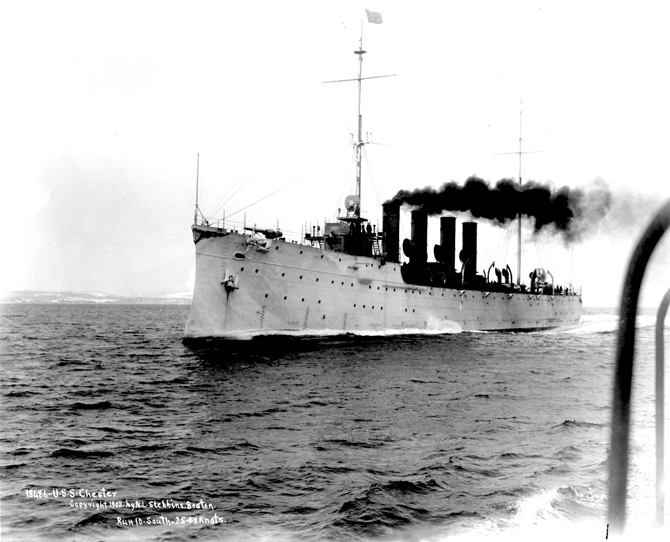

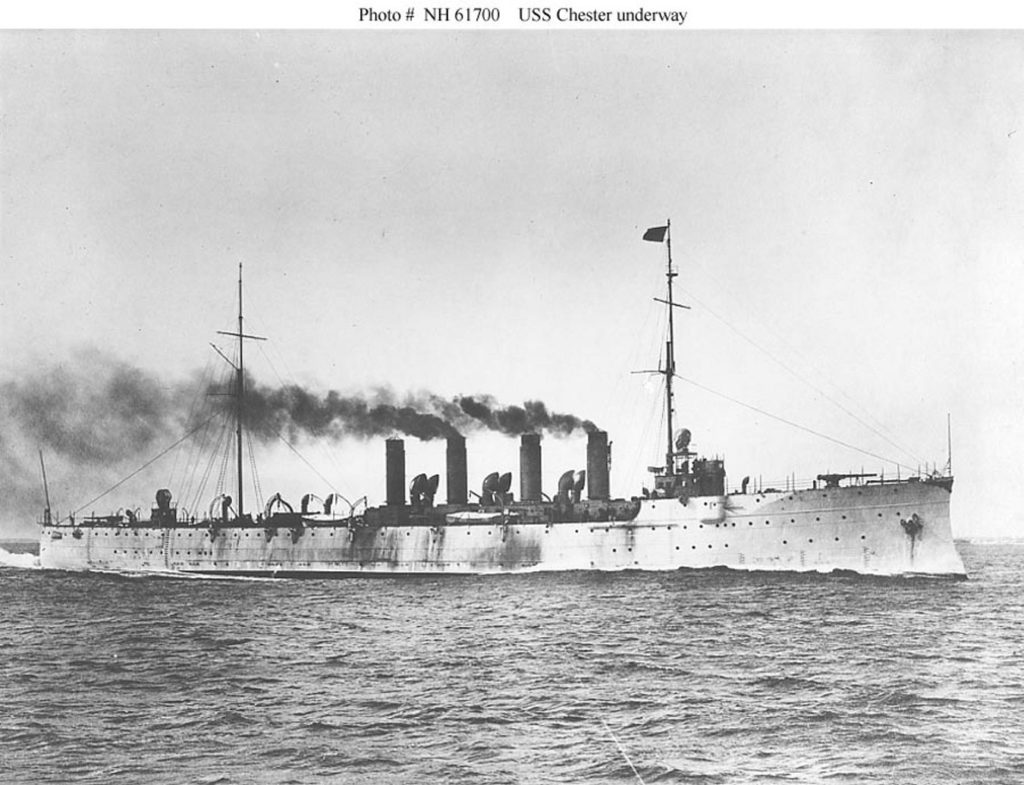

The USS Chester, racing towards the sinking Titanic

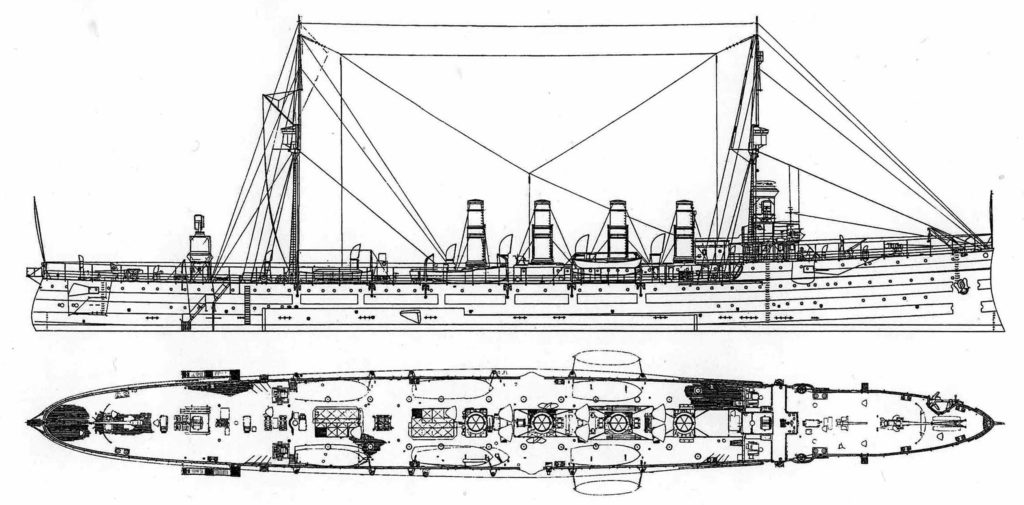

Design of the Chester

Hull and armor

Protection was bare minimum to resist small caliber and shrapnel at 2 in (51 mm) for the belt which was 9.5 ft (2.9 m) high above the waterline, and down around the engine and engine rooms, with 6.5 ft (2.0 m) high around the boiler room area and 3.25 ft (1 m) below. No protective deck was found as the ship was not a protected cruiser, but there was a stray of 1 in (25 mm) plate armor on the roof deck above the steering gear. In short, the Chester class was not even immune against destroyer fire, despite their large size and high freeboard.

Propulsion

The Chester, Birmingham and Salem all tested different propulsion system in order for the Navy to test each configuration. It was customary with the USN and allowed later to combine advantage on future series. USS Chester innovated in the matter by receiving steam turbines. This was the very first ship in the USN to be fitted with Parsons types. USS Salem on her part received Curtis turbines and Birmingham stayed with traditional triple-expansion engines. Requirement speed was 24 knots (27.6 mph; 44.4 km/h) only for USS Birmingham, the triple-expansion one, but one knot more for the two turbine cruisers.

On the boilers front, all three ships differed also: USS Chester had 12 coal-fired Normand boilers mated with the Parsons direct-drive, rated for a total of 23,000 shp (17,000 kW), and four shafts. On trials she was able to reach 26.52 knots (30.5 mph; 49.1 km/h) on about 16,000 shp (12,000 kW).

USS Salem had like her sister ship the same number of coal-fired boilers, this time of the Fore River model, mated to Curtis direct-drive steam turbines. Design power as specified was 23,900 shp (17,800 kW), but this power was passed on two shafts. Max speed on trials was 25.95 kn (29.9 mph; 48.1 km/h) on a total of 22,242 shp (16,586 kW).

Lastly, USS Birmingham, the TE version on her part was fitted with twelve coal-fired Fore River boilers. Working pressure was 275 psi (1,900 kPa), and the engines were two four-cylinder vertical triple-expansion models, which were rated for 16,000 ihp (12,000 kW) as designed, and two shafts. On trials she reached 24.33 kn (28.0 mph; 45.1 km/h) at 15,670 ihp (11,690 kW).

All three ships had relatively similar coal arrangements, with a coal capacity of 475 tons in peacetime, and up to 1,400 tons in wartime.

Armament

Primary armament: It consisted in two 5-in (127 mm)/50 cal. Mark 6 guns. They were of the same model used on the Battleships and cruisers of this era.

In service by 1904, these guns were weighting 10,550 lb (4,790 kg) with breech, for a length 255.65 in (6,494 mm), and barrel length of 250 in (6,400 mm) bore, 50 calibers. It fired 50 lb (23 kg) armor-piercing shells, with an elevation ranging from −10° to +15° to −10° to +25° between the Mark 9 and Mark 12 mounts (The Mark 6 gun used both). Average rate of fire was comprised between 6 and 8 rounds per minute and muzzle velocity for the 50 lb AP shell was 3,000 ft/s (910 m/s) and for the 60lb HE shell 2,700 ft/s (820 m/s), at a maximum firing range of 19,000 yd (17,000 m) at 25.3° elevation.

Secondary Armament:

This comprised six 3 in (76 mm)/50 caliber rapid fire (RF) guns and two 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes. The original uniform gun design was of twelve 3-inch guns, an idea supported by the Navy’s General Board to simplify fire control and have a standard among main and secondary armaments of dreadnoughts as well. In the end however two 5-inch guns were substituted for six of the planned 3-inch guns. The idea was to give these scout cruisers a better capability to fight light cruisers. But this was a simplification overall as they were the first US cruiser design not fitted with smaller 6-pounder and less guns.

All three ships underwent a major refit in 1917 as the USA were found at war: USS Salem received a 20,000 shp (15,000 kW) General Electric geared steam turbine installation which saved coal consumption, as she was the only one without turbines. They all were rearmed with four of the new model 5-inch (127 mm)/51 caliber guns. Secondary armament was upgraded too, with two 3-inch/50 caliber guns plus two 3-inch/50 AA guns, but torpedo tubes were kept, whereas they had been removed from nay cruisers at that stage.

The Chesters in action

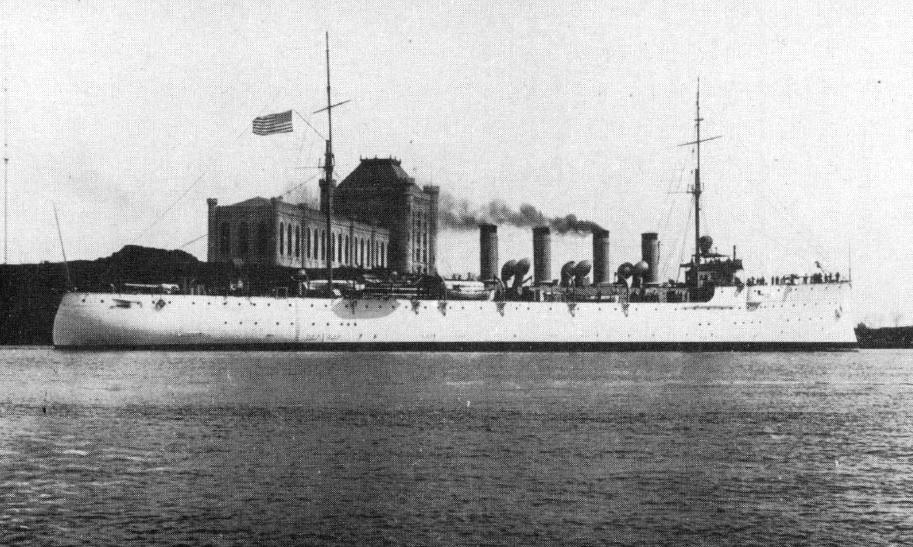

USS Chester

From her commission and first crash course, USS Chester trained off the East Coast and Caribbean, and participated in the Fleet Reviews of February 1909, October 1912, and May 1915. She also carried a Congressional committee to North Africa in 1909, and was part in 1910 to the special South American cruise for the centennial of Buenos Aires. She patrolled off Mexico, Santo Domingo, and Haiti, carrying by all times a Marine batallion for occupation in 1911. By April, 1912, she escorted the SS Carpathia back to New York, after picking up the survivors from the RMS Titanic. She was placed in reserve in 1911 – 1913, and was back in the Gulf of Mexico to protect US Citzens and property during the revolution, and took part in the occupation of Veracruz. On 2 January 1914 she hosted President Woodrow Wilson holding a conference with John Lind (Mexican affairs).

On 21 April, Admiral Henry T. Mayo was ordered to send the Chester from Tampico, to Veracruz and she arrived Around midnight, under captain William A. Moffett. He took the inner harbor, running straight in showing a breath-taking display of seamanship and nerve and was later awarded the Medal of Honor. She landed safely her batallion and provided support fire during its advance in the southeastern sector of Veracruz. She targeted notably the Naval Academy and later carried refugees to Cuba as well as mail and storage for the local squadron until June 1914. Afterwards she went into reserve to Boston and overhaul, which lasted until April 1915.

By late 1915 – early 1916 USS Chester departed for the Mediterranean for a relief aid operation in the Middle East and to protect US Citizens on the Liberian coast during the insurrection. She retuned to the reserved until 24 March 1917. She operated on off the East Coast until 23 August, and from Gibraltar escorted convoys bound to Plymouth, England. On 5 September 1918, she correctly identified a U-boat. She tried to ram the German submersibles, but the latter dove quicker. However she managed to damage her own port paravane. In 1918, after a career without notable incident, USS Chester carried the Allied armistice commissions inspecting German ports. In 1919 she would ferry US Army troops to support actions of the “whites” in northern Russia. She later would depart Brest in April 1919, with veterans to New York and later was sent at Boston NyD for overhaul, and decommissioned, until 10 June 1921. By 1927, she was renamed USS York at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, scrapped on 13 May 1930.

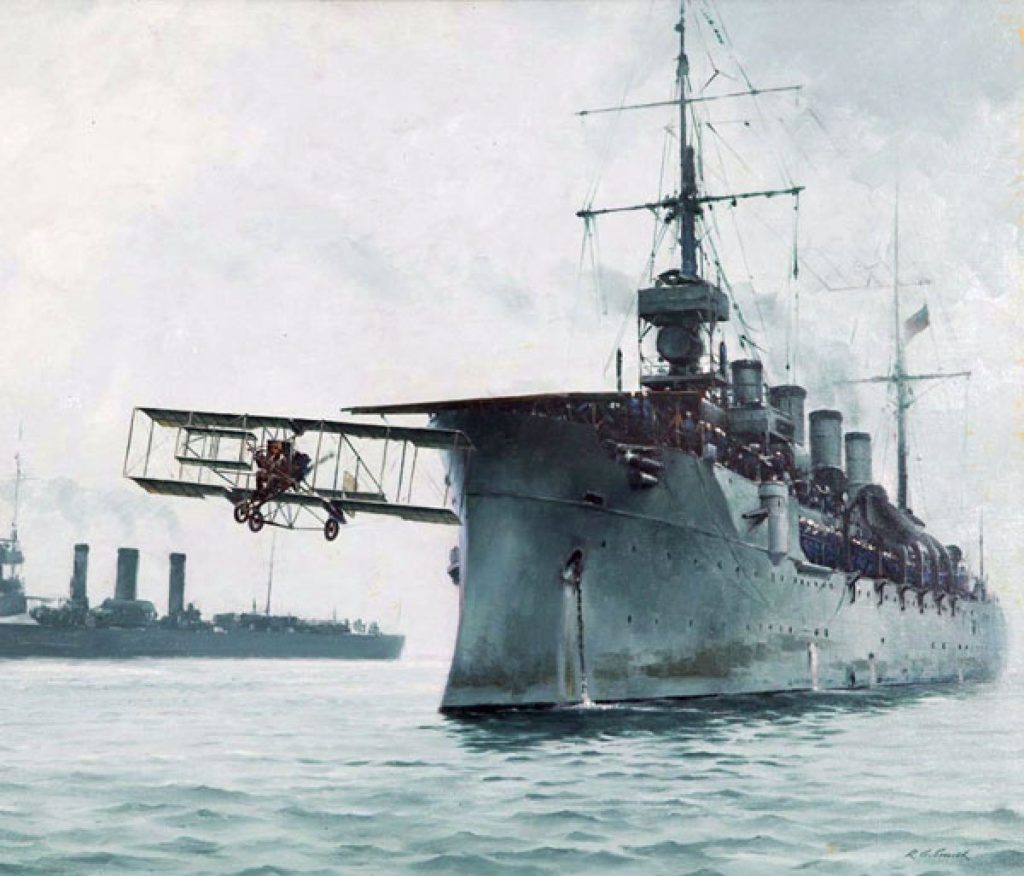

USS Birmingham

Birmingham was commissioned on 11 April 1908, taking her service under captain Burns Tracy Walling. She served in the Atlantic Fleet until June 1911, then was placed in reserve at Boston. Later from her deck, a daring civilian pilot Eugene Ely attempted the first ship-borne takeoff, on 14 November 1910, in a Curtiss Model D biplane designed by Glenn Curtiss and piloted by Eugen Ely. By 15 December 1911, the cruiser was fully recommissioned and toured the West Indies and was stationed at the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Philadelphia NyD in April 1912. Until 11 July, she made the infamous “Ice Patrols” and was later versed to the previous Reserve Group. In 1913 she carried carried Commissioners of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

She left the yard on 2 February 1914, and resumed operations with the Atlantic Fleet as flagship of the Torpedo Flotilla. From 22 April – 25 May, she operated with the fleet in Mexican waters. During this time, one of her two Curtiss Model F flying boats performed the first military mission by a US heavier-than-air aircraft, while scouting for mines off Veracruz on 25 April. In 1916, she became flagship of Destroyer Force Atlantic Fleet, and Torpedo Flotilla 3.

World War I and fate

Following American entrance into World War I, Birmingham patrolled along the northeast U.S. coast until 14 June 1917, when she sailed from New York as part of the escort for the first US troop convoy to France. After returning to New York she was fitted for service in Europe and in August reported to Gibraltar as flagship for Rear Admiral A. P. Niblack, Commander, US Forces Gibraltar. She escorted convoys between Gibraltar, the British Isles, and France until the Armistice. After a short cruise in the eastern Mediterranean, she returned to the United States in January 1919.

From July 1919 to May 1922, she was based at San Diego, California as flagship of Destroyer Squadrons, Pacific Fleet, and then moved to Balboa, Canal Zone as flagship of the Special Service Squadron. After cruising along the Central American and northern South American coast, she returned to Philadelphia and was decommissioned there on 1 December 1923, being sold for scrap on 13 May 1930.

In a painting titled “The Beginning” by the late, great aviation artist R. G. Smith, 24-year-old civilian pilot Eugene Ely takes off in a 50-horsepower Curtiss biplane from a wooden platform built over the bow of the USS Birmingham (then designated as Scout Cruiser #2) at anchor in Hampton Roads, Virginia. Ely landed moments later on Willoughby Spit.

USS Salem

USS Salem was the Navy’s first turbine-powered warships. So she was to be tested and evaluated in detail. She departed Boston on 17 October 1908 for a test campaign on the Atlantic coast. Together with USS Birmingham and Chester she formed the Scout Cruiser Division, patrolling in the Atlantic. She toured Funchal on the island of Madeira. This was the further away she went at that time. She joined the 5th Division, Atlantic Fleet and in 1910, she was stationed in Haitian waters. She was back to NYD on 11 September and placed in reserve at the Boston NyD by April 1912, as a receiving ship. She would return in the Atlantic Fleet and toured Gibraltar.

In 1913-14 she remained in Philadelphia until placed in reserve to be on duty again by 23 April 1914. She joined the Special Service Squadron in Mexican waters, took part in the Veracruz operation, and returned to the Atlantic Fleet, but returned in reserved on 1 December as receiving ship at Boston NyD by March 1915. She cruised in the Caribbean by May 1916, and off Mexican and Dominican ports, transported Marine detachments and other taks before being decommissioned again on 2 December 1916.

Recomm. in 21 April 1917 she left Philadelphia NyD for Boston NyD and entered a drydock to have her original Curtis turbines replaced by General Electric turbines. This was completed by 25 July, and she departed for a crash test from Boston to New London (Ct) and a force made of sub-chasers to protect Atlantic convoys. She served as flagship for two convoys up to the Azores and back. She headed later a flotilla of 12 sub-chasers at Key West. Patrols stretched from Florida to the Yucatán Peninsula. By 27 November, the squadron was disbanded and after a short overhaul at Boston, Salem sailed to the west coast, and as CL-3 (from 17 July 1920) she was decommissioned at Mare Island, struck on 13 November 1929, sold in 1930 and BU in California.

Read More/Src

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1860–1905.

Burr, Lawrence. US Cruisers 1883–1904: The Birth of the Steel Navy. Oxford : Osprey, 2008.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester-class_cruiser

Photo archives https://www.navsource.org/archives/04/001/04001.htm

http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/ships/birmingham/birmingham.html

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2011/september/humble-beginnings-where-are-carriers

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign