US Navy Escort Destroyers (1942-44): 105 planned, 97 completed (8 cancelled, 46 to Britain)

US Navy Escort Destroyers (1942-44): 105 planned, 97 completed (8 cancelled, 46 to Britain)The GMT (also known as the Evarts class from its lead vessel) or “short hull” were the first escort destroyers of the US Navy. A new type of ship solely dedicated to ASW escort (British request for the Atlantic) but the majority were pressed in the Pacific.

In all, the USN would build a colossal mass of such vessels (563), with iterative improvements made during the war, identified by their acronyms, GMT, TE, TEV/WGT, DET/FMR.

Just like the also numerous escort aircraft carriers (such as the Bogue or Casablanca class of Kaiser Yards), they were really the unsung heroes of WW2.

Their career was rather meteoritic, as they were put on the disposal list once their job was done postwar, and the immense majority scrapped after 1947.

The latter classes were considered better and saw exports and further cold war service, for many until the 1970s.

This post is about the GMT “short hull” at first ordered for the British Royal Navy. When pressed in USN service, the majority went for the Pacific. https://naval-encyclopedia.com/ww2/us/gmt-class.php #ww2 #destroyerescort #evartsclass #pacificwar #battleatlantic

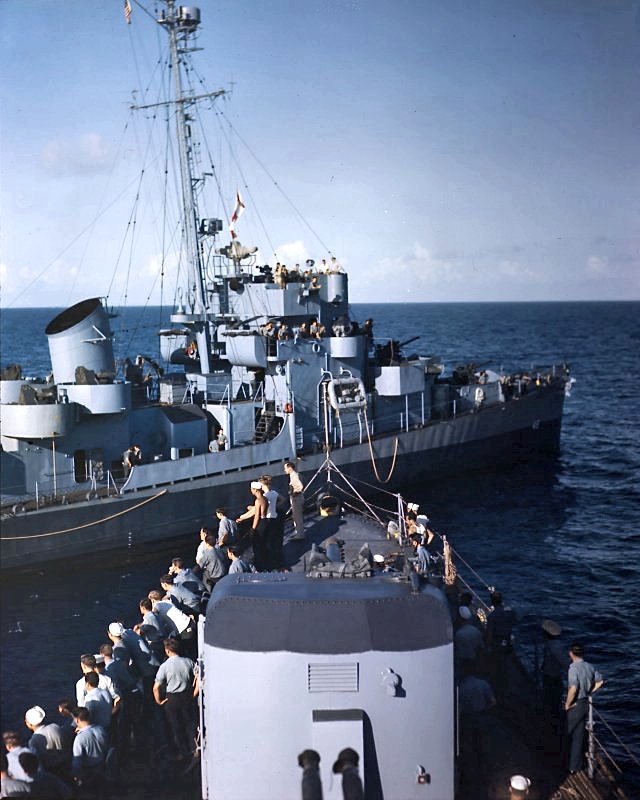

USS Andres (DE-45) at sea underway, color photo seen from a destroyer (prow, seen from the bridge). This photo was used to illustrate the Camouflage Measure 22.

So, what is an escort destroyer, why they were built, under what designs, that’s what this article would try to cover, as well as all the details and nitty-gritty aspects. A first post, to be followed by others until the end of the year. For space reasons, their career will be abbreviated with the essentials and sticking points, with exceptions for the most outstanding ships each time.

Development

Introduction: Unsung Heroes

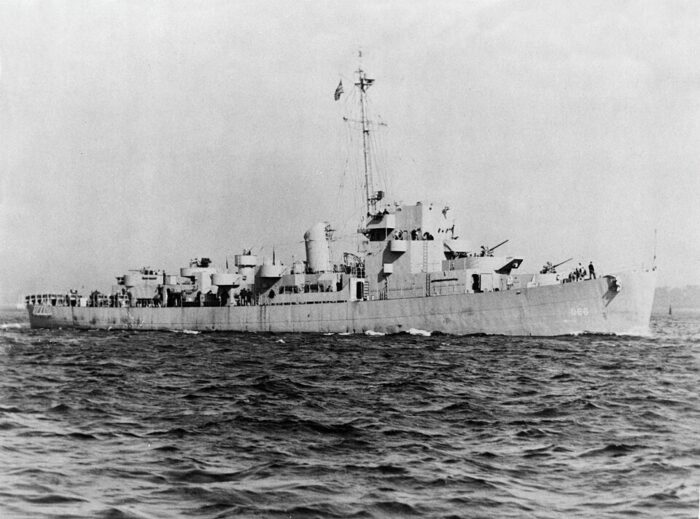

USS Evarts, the lead ship, in August 1944.

Indeed, as they assumed the very same unglamorous work and escaped, for the most, the attention of the public. Until today, they remain a far less “sexy” subject to pick for aspiring or established naval historians. Yet, their contribution to the victory in Europe could not be understated. They, even more than regular destroyers, broke the back of the U-Boat arm. They ensured the thousands of men and material flow uninterrupted from the arsenal of democracies to the frontline, until the final push on Berlin. The effort to win the battle of the Atlantic was of course, a shared effort with many moving parts, like Ultra, new detection systems, new tactics (such as the hunter-killer groups based on escort carriers) and just out-producing Germany in what was remains the longest and most intense battle of attrition in History. In the Pacific, they also freed fleet destroyers from escorting amphibious groups or the immense logistic train of TF 38/T58 and many other fleets in operation in the Pacific, and equally shared the laurels for the victory in the Pacific.

Yet, their construction was not certain at first. The “escort destroyer” as a category went from nowhere. In WWI the ASW effort was shared by whatever ships could be scrapped for that escort work, at a time these techniques to counter submarines were in their infancy, sloops and sub-chasers. Britain was strong on the first (and Q-ships) while the US provided, via its industrial might, thousands of the latter. The “four stacker” flush deck destroyers of the Clemson and Wickes class developed an ASW capacity by being armed with the first depth charge racks from the start, and tested Y-Guns. But there was no thought of an intermediary type at the time, the sub-chasers were coastal only, unfit for Atlantic service.

The British Way of ASW escort

The Battle of the Atlantic pretty much started in the first day of the war in September 1939, ships were sunk, and the first U-Boat kills were recorded. By the time, ASW escort was more grounded as a concept, and many started to work on ways to improve it before the war. Indeed in 1935, the Anglo-German naval treaty, concluded in the wake of appeasement measures with Nazi Germany, nullified the Versailles Treaty and its restriction on submarines. Germany had been covertly working until then (see the recent article on the Type VIIA) with IvS at the Hague (Netherlands) on new designs, built and operated by Turkey, Finland or Sweden. In 1935, the Type I, Type IIa/b and Type VIIA were in construction. A possible new war and a new submarine warfare scenario was no longer far-fetched.

There were ideas of resurrecting the convoy system, converting trawlers, used sloops of the RN for the task, but the first attempt to create a dedicated ASW vessel came really in 1938 when it was suggested that if simple enough, it could be manufactured in civilian yards rather in already overtaxes Naval Yard across Britain. A whaler was chosen as base model for a new corvette, making sense for the North Atlantic in winter. The Flower class Corvette thus was built already when the war broke up. It was on one hand, praised for the numbers it procured to hard-pressed convoy escorts, at first only fleet destroyers, but after a first year of service in late 1940, it was clear there were many issues with the design. They were slow, vulnerable with a single shaft, wet and uncomfortable for a larger crew than a standard whaler of that size, among others.

However, these civilian yards were now familiarized with the construction of a standardized ship to near-military standards. This was a nation-wide experience that was praised at the time. A valuable asset now in the hands of the government, for the war effort that was put to good use on the next, more ambitious design by the admiralty, the River class Frigates. This time, the design was far more advanced, more military. This was a proper two-shaft vessel, much larger, with better range and speed, better armament and facilities. The upgrade from the plucky corvette was immense.

They were built by From 1941 onwards, from a selection of yards (the previous “test” allowed to pick up the best at their game) in addition to Canadian and Australian Yard. The Corvettes would evolve in to the “improved flower” and castle class eventually in 1943, whereas the Rivers were followed by the Loch and Bay class in 1944-45, reusing the same recipe. In between, British established naval yards had radically augmented their capacity to wartime standards, and could now deliver additional vessels than destroyers and submarines. This led to perhaps the most influential design as far as ASW is concerned for our subject.

Indeed, all these developments were followed by the US Admiralty under CNO Admiral King. But if not impressed by the Corvettes, which seemed quite desperate as a concept, the Frigates drew some attention. But it was the Hunt class that really “sold” at least the concept of an escort destroyer to Admiral King. It predated the River class Frigates in fact, and was planned after the corvettes, in a more conventional way to escort convoy, built by established military yards. The hunt class were called “destroyers” indeed, but they were, when planned in 1939 in effect the world’s first escort destroyers. The RN indeed before even the war started, and the writing was already on the wall for many, identified the need for two types of destroyer, one for escort and fleet duties, and another for escort work.

Indeed, all these developments were followed by the US Admiralty under CNO Admiral King. But if not impressed by the Corvettes, which seemed quite desperate as a concept, the Frigates drew some attention. But it was the Hunt class that really “sold” at least the concept of an escort destroyer to Admiral King. It predated the River class Frigates in fact, and was planned after the corvettes, in a more conventional way to escort convoy, built by established military yards. The hunt class were called “destroyers” indeed, but they were, when planned in 1939 in effect the world’s first escort destroyers. The RN indeed before even the war started, and the writing was already on the wall for many, identified the need for two types of destroyer, one for escort and fleet duties, and another for escort work.

It was theorized that in case of war, vintage WWI and 1918-1920 destroyers such as the V-W class and former leaders still active in the fleet, would take that role, freeing more modern fleet destroyers of the A-B class and following to work with the fleet. The new design was to replace these ageing vessels, that could be converted for ASW work but were not optimal for the role. Even less so were fleet destroyers. Their torpedo armament and heavy artillery and machinery, speed were made for fleet actions, not slow-paced convoy escorts with only submarines to care for with depth charges. It was understood that in the budget-stricken context of peacetime England, these new escort destroyers could not be funded, but in wartime, they would be ready under short notice. After 1 September 1939, that is precisely what happened.

The Hunt class were greenlighted and orders were placed at Cammell Laird, Yarrow, Vickers, John Brown, Swan Hunter, Scotts, White, and Stephen. These were already almost as large or larger than the WWI vessels they were supposed to replace, at a symbolic 1000 tonnes standard, 1400 tonnes FL, but very different from classic destroyers: instead of solid single 4.7 inches main guns and two banks of torpedo tubes, they had two twin (dual purpose) 4-in/45 QF Mk.XVI HA instead (the Luftwaffe threat was taken seriously), no TTs and instead pompom AA guns, and several racks and throwers for a large complement of depth charges, plus a slightly more developed sonar room and extra facilities. The Hunt class however was the victim of serious miscalculations in design and were fatally flawed in terms of stability, and needed urgent and radical corrections afterwards.

The Hunt class were greenlighted and orders were placed at Cammell Laird, Yarrow, Vickers, John Brown, Swan Hunter, Scotts, White, and Stephen. These were already almost as large or larger than the WWI vessels they were supposed to replace, at a symbolic 1000 tonnes standard, 1400 tonnes FL, but very different from classic destroyers: instead of solid single 4.7 inches main guns and two banks of torpedo tubes, they had two twin (dual purpose) 4-in/45 QF Mk.XVI HA instead (the Luftwaffe threat was taken seriously), no TTs and instead pompom AA guns, and several racks and throwers for a large complement of depth charges, plus a slightly more developed sonar room and extra facilities. The Hunt class however was the victim of serious miscalculations in design and were fatally flawed in terms of stability, and needed urgent and radical corrections afterwards.

To the Type I (1939-40) succeeded the much improved Type II (1940-41) and Type III (1941-42). In total, 84 military-grade vessels. In general concept, they were not that different from the sloops that were built prior (1931 Shoreham, 1936 Grimsby, 1938 Egret) or at the same time (Black Swan class). The hull of the latter was however provided a longer forecastle, and if provided with turbines, they were limited to 19 knots, whereas the Hunt class could reach 27 knots, less than fleet destroyers, but enough to race towards a submarine, chase it off, and then coming back to the convoy at flank speed. This was not possible for a flower or river class, and precious assets for a more active and efficient escort job.

The US policy for ASW

The 110-ft wooden SC boats

WWI experience and Interwar stance

This brings us back to the state of ASW policy in the US at the time, in 1939. First off, neutrality applied, and no ASW program was actively maintained the US. The experience of WWI was still there, and the US had been instrumental to design late depth charge types, as well as the “Y Gun”, the first DC projector. The closest to the dedicated, dirable ASW ship known so far was the Eagle Boat developed by Ford in 1918 as an inexpensive, coastal waters all metal, affordable escort. They contrasted with the mass of wooden-built SC boats that ended on the civilian market postwar, as a one-off ASW asset for the entente (Sc 110 ft series). The Eagle boats were slab-sided vessels made for quick construction from prefabricated elements, armed with guns and depht charges. The emphasis on guns is a reminder that most U-Boats in WWI were caught surfaced, as they spent most of their time surfaced.

The Eagle Boats, 60 crude vessels by Ford, which arrived too late for WWI and left a sour taste to the Navy.

But the Eagle Boat left a bitter taste to the USN. Ford was obviously unaccustomed to marine construction, and overpromised on a product that was presented off the hat, from his design team, with little feedback or liaison with the USN or naval yards. It was more an exercise in diversity in terms of mass construction. Not only after the contract was signed in March 1918, no boat was delivered on schedule (the first was not even delivered by November) but when they do, the Navy refuse them. Not because the war was over, and the order cancelled, it was, partly, contractual obligation meant the Navy had to accept delivery on contractual terms if the boats were indeed delivered at least for the first order.

But they were rejected out of poor quality. They were just unacceptable, as crudely made ships with no marine qualities, plagued by leaky fuel oil compartments and disjointed hull plates. At sea, they were just horrible. The contract was curtailed to just 60 and Ford was forced to make many adjustments, loosing time and money in a postwar context where it had to lay off a lot of workers. In the interwar, they saw some services for other roles, many being transferred to the US coast guard, which shared the responsibility in WWI for ASW warfare. Many were scrapped in the 1930s. A few ended as targets. In WWI, just a single boat in Miami was still used as a stationary training vessel. Eight more still around were put in shape by December 1941 and saw service in 1942 during the “second happy time” of Dönitz’ grey wolves. When the war started, they were the only dedicated ASW patrol vessels of the USN.

This Eagle Boat experience, combined with the end of the first Atlantic Battle, neutrality and post-1929 budget cuts, brought no incentive to develop ASW means for the USN. In case, the numerous and now vintage Wickes-Clemsons would be used for escort in case of war. They all had depth charge racks and throwers. In 1940 already, fifty of them were lent to the RN for ASW escort work. They were proposals for a replacement for the Eagle Boats, this time, designed and built by dedicated Yards and naval architects (Ford never returned to naval construction). Discussions about these were notably more prevalent during the “quasi war” with Germany in 1941 when the US shared the burden of escort work in their own territorial waters and beyond in the Atlantic.

A quasi-war in September-December 1941

USS Reuben James

There have been many incidents already, some close calls, and despite instructions not to do so, US Captains, seeing ships in their convoys being savaged by U-Boats could not stay still. They made runs at the supposed U-Boat position, not dropping anything but at least “keep their heads down”, and trying to just scare these out under their watch, while not breaching a more fragile neutrality stand. But despite this, many US merchantmen were sunk in the months from 11 March (start of lend-lease), then July 11 (start of active escort) to 07 December 1941. Then military ships became sometimes accidental targets for U-Boat commanders, despite Hitler’s instructions relayed by Dönitz. In September there was USS Greer (4th) 175 miles from Reykjavík, which was signalled a U-Boat, went for it but abstained to drop depth charges, however confirming its position by sonar to other allies.

Attacked by a British aircraft, U-652 then turned against USS Greer, fired a torpedo that she dodged. Greer then dropped DCs and evaded a second torpedo before making in to port. President Roosevelt publicly denounced the event on 11 September to prepare US opinion. On 20 September, this was USS Truxtun that suddenly spotted a U-Boat at 50 yards in fog. She dropped depth charges after she dove deep. Then there was USS Keany in the night of 16-17 October spotted a U-Boat in the middle of the convoy, surfaced, launching three torpedoes at her. Her skipper, Capt. Anthony L. Danis, dodged two, but his boat was hit by the third. The damage was immense, but she survived and limped back to Hvalfjordur for emergency repairs. On October 27’s speech, Pdt. Roosevelt announced

The shooting war has started. And history has recorded who fired the first shot …”

On 31 October, when that escort work became more tense than ever (it was now called in the press a “quasi war”), just 37 days before Pearl Harbour, Destroyer No.245 (DD 245) USS Reuben James (“the Rube”) under Commander Edwards, was torpedoed and sunk by U-552. The torpedo broke her back after an ammunition magazine detonated. She was the first US ship lost in WW2, even though the country-continent still not seen itself at war. Interrogated later back in Germany, skipper Kapitänleutnant Erich Topp explained he could not see the ship flying the regulatory ensign of the United States and was seen in the process of dropping depth charges on another U-Boat. Only 44 survived. The event made headlines in the US and changed the policy against U-Boats for an even more aggressive stance. Now this was a “free for all” against any detected U-Boat, unrestricted. Still, this was not an event to the scale of the Lusitania. The US would remain neutral until Pearl harbour.

Roots: The British BDE program (1941)

So back to the US admiralty, the start of WW2, from September 1939, cancelled overnight all restrictions inherited from the Washington treaty and London conference. There were massive construction plans now free from tonnage limits in quantity and quality, for cruisers, destroyers, battleships and aircraft carriers, but no formal escort destroyer planned yet. The main drive did not come from US needs at the time, as the country was still not at war as we saw above, even by late 1941 when the Atlantic escort turned into a full combat engagement. However, this did not meant anything was studied.

The GMT and follow-up designed indeed originated in a series of design studies for escort vessels, ordered by the General Board in 1940. A major factor in US interest was the success of the British Hunt class, particularly after the Mills-Cochrane mission to the Royal Navy. Early projects were dropped in view of the small saving they represented compared to a much more capable conventional destroyer, notably refurbishing the vintage Wickes-Clemsons.

Moreover, destroyers were already in production and so could be had sooner. What saved the concept was British interest in light second-rate destroyers. On 23 June 1941, so before Roosevelt changed the US escort policy, the British Supply Council in North America asked the Secretary of the Navy to release some escort destroyers, with a long-term programme of 100 units.

The principal changes requested were a dual-purpose main battery (three 3-in/50 rather than two single-purpose 4-in/50) and triple torpedo tube to face potential surface raiders. The latter would be provided out of stocks released by escort conversions of existing ‘flush-deckers’ that were going to be converted as pure escorts. Although later, new production was required. The bridge was a British type, with the conn one level above the helm. Despite Bureau of Ships arguments, repeating that destroyers could be delivered far more readily, the President approved the production of 50 British destroyer escorts (BDE) on 15 August 1941.

It was logical that came from the British, which carried most of the escort burden in 1940. Roosevelt was also instrumental in this, agreeing in July 1941 not only to take part in the convoy escort, notably of US ships bound to Britain and convoy up to the mid-Atlantic, where British ships would completely take over, but also to ease the British Government access to US shipyards proposals for a new type of escort. The model indeed wanted by the British were an adaptation of their own Hunt class design, at least the improved Type II by then in construction. The British Mills-Cochrane mission already in 1940 toured US shipyards to take proposals.

The resulting US class was nominally divided into six classes for more than 500 ships built, but they were actually variants of a single design.

It was agreed the BDE would have been powered by geared turbines, for a speed of 24kts. This was an important, if not stringent specification. However, gear-cutting presented a production bottleneck, and diesel engines of submarine type had to be substituted. They added 33ft on length and 130 tons. Moreover, landing craft orders squeezed diesel production. The original design had called for eight 1500hp diesels, four driving through electric motors and four through small gears.

Now the geared diesels were eliminated, at a cost of 4.3 kts. Ships of this type were ‘short hulls’ or ‘GMTs’, for ‘GM Tandem’ (diesel)) drive. The next propulsive system to be explored was turbo-electric: the original horsepower was retained, but the hull had to be lengthened; it turned out that the lengthening balanced off the increase in displacement and the speed of these TE units was about 24kts. The longer hull was standardised for ease of production; other propulsive alternatives explored were a geared turbine using relatively small gears ((WGT’), the original diesel-electric system in a long hull “DET’), and a geared diesel drive ((FMR’, for reduction geared, also half Dower). So if you still wonder why these odd acronyms, they were all used as propulsion variants due to supply issues.

Construction

Orders, of course, greatly exceeded the original fifty: at its peak, the DE Programme envisaged the completion of 1005 units — 105 “GMTs”, 54 “TEs”, 252 “TEVs” (“TEs” with 5-in guns), 293 “WGTs”, 116 “DETs” and 85 “FMRs”, Many of these were ordered specifically to ensure the completion of 260 units during 1943; in fact over 300 were delivered that year, Mass cancellations began In the autumn of 1943: 305 in September and October, another 135 in 1944, and 2 in 1946. Many “DEs” were converted to fast light transports (APD); 44 “TES” and 51 “TEVs”, against a programme of 50 of each. ‘There was also a programme for twenty conversions to radar pickets, of which only seven were completed, at the end of the war (DE51, 57, 153, 213, 223, 577 and 578), Many others were converted in the 1950s as part of the North American air defence system.

DE armament varied greatly during the war. The original design embodied space and weight reservations for the installation of two enclosed 5in/38 in place of the 3in/5S0, and the “TEVs” and “WGTs” were completed to this standard. At one time it was planned to convert all “DEs” as weapons became available, but this programme was abandoned for the “GMTs”; these ships were the only DEs which never mounted torpedo tubes.

Ironically, too, the Royal Navy, which had originally specified tubes, asked that they be deleted from DEs transferred to it. On the other hand, it was the Royal Navy which specified the installation of Hedgehogs, with which all DEs were fitted. Externally, all but the “TEVs” and “WGTs” had the original high British-style bridge, similar, incidentally, to that of the 180ft minesweeper/PCE — another class built originally to an Admiralty requirement. In the ships designed for Sin guns, a lower bridge was employed, similar to that originally installed in the Sumner class destroyers and in a few destroyer reconstructions; it, too, was derived to some extent from contemporary British practice.

This type of bridge was not installed in 3-in ships converted to 5-in guns — USS Camp, following an April 1945 collision, and 11 out of a projected 40 “TEs” (DE217—219, 678-080, 696-698 and 700-701; the ‘TE’ conversions were carried out in the autumn of 1945). Nor was it installed in the radar picket “TEs”, which received a pair of in guns as well as a new CIC and a heavy radar mainmast. In many ships the triple TTs were removed, replaced on refit by four Army model single Bofors guns. Moreover, a few late-production ships were completed without the tubes: six “WGTs” (DE448—450. 510, 537 and 538) had a single quadruple 40mm aft, 3 twin 40mm, and 10 single 20mm. In four “I’s” (DE575—578), tour Army type 40mm replaced the triple tubes.

Design of the class

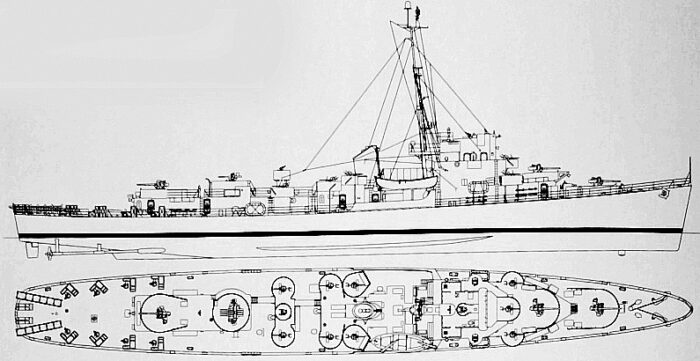

So the first design under study are the “GMT”, meaning “GM Tandem” diesels. They were also called the “short hulls”. Unlike the Hunt class, which had their classic forecastle, the American-built DEs (or more precisely BDE as they were initially built partly ion British specifications) had flush-deck hulls for ease of construction. This was the same a destroyer such as the Fletchers, Gearing and Allen M Sumner and a design solution that was kept for decades even in the Cold War.

Hull and general design

The design was specified as seen above in June 1941 by the British military mission which requested 100 BDEs based on a U.S. Navy conceptual design for a 280′ (85m) ship, armed with two 5″/38 dual-purpose guns and a triple torpedo bank, as well as extensive antisubmarine gear and a top speed of 24 knots.

Shortages of both 5″/38 guns and machinery led to design as a stopgap the “Evarts class” armed with 3″/50 guns instead (on superfiring posts), still adequate against surfaced submarines. They used diesel engines, making for a shorter hull, and which proved badly underpowered with a top speed far short of the objective. But their antisubmarine gear was generous and incorporated the latest improvements. This class however became infamous for its tendency to roll.

A profile of USS Edward C. Daly at Mare Island NyD, California, just commissioned, photo for the archives.

Hull design

The Evarts class ended larger than the Hunt class, despite a lighter armament, albeit at first turreted 5-in guns were planned. They would be installed on the later classes. One crucial aspect for US engineers of BuShips, was to study the shortcomings of the Hunt class type I, which had completely mismanaged stability calculations resulting in a grave instability while in service. Yet, the new ships needed a tall bridge as requested by the British, combining an enclosed steering bridge and a watch open bridge above. The forward armament was lighter, better balanced, and superfiring, but the flush deck hull designed enabled sparing weight in general and improved stability.

The GMT class displaced 1192 tonnes standard for 1,360 tons fully loaded. They measured 283 ft 6 in or 86.41 meters at the waterline for the length and 289 ft 6 in (88.2 m) overall. For a beam at 35 ft (10.7 m) and an average draft between 9ft and 10 ft 1 in (2.7-3m) when fully loaded. They were thus noticeably larger than the Hunt class (85 x 5.8 x 3.27 m) albeit the superior beam was to spare some draught, enabling missions closer to the shore and in shallower waters if needed.

They had no transom stern, but instead a mix of rounded and transom, with some declivity. The hull lines were a variant of the “pear shape” used for the Fletcher class from Gibbs & Cox, with the greatest beam reached about 2/3 aft. The structures were measured, notably for weight reasons, and deck space was generous. The prow had a typical stem, in-between clipper and straight at the same angle as Fletcher class destroyer again, and ended in the same way. Flare was limited. As usual, the forward draught was inferior to the aft draught, and the proportion of stem above water was 3/4 compared to the submerged part. Aft, the proportion above/below the waterline was about 50%. There was a keel tail, two long shafts with twin struts, for finer exit lines, a small axial rudder aft (too small as it appeared later) and two angled down anti-roll keels. Both the GMT and TEs were very close in design, near sister ships, nearly indistinguishable before 5-in guns turrets were installed when available in 1944. The only difference was their hull length.

Design Description

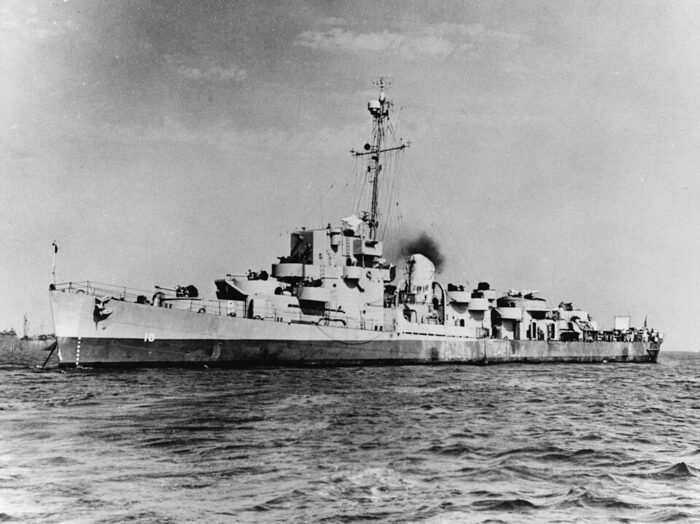

Now their general outlook superficially looked “overloaded”. The tall bridge asked by the British was its distinctive feature, reproduced on the next TE (Buckley) class. However if it led to an excellent peripheral vision to spot surfaced submarines, it also caused some stability issues and this was corrected on the next TEV, WGT and follow-up designs.

The two forward guns were installed behind bulwarks in a deck position and a superfiring post closer to the bridge. The latter had in fact two open bridges, one was lower, around the enclosed navigation bridge, and the other on top, with tall walls, and a series of windscreens. All around were installed scopes. There, two signal lamps but no large light projector for night operations, albeit the powerful signal lamps could be used that way.

Then came the unique, tall and raked mainmast behind the bridge. It supported the usual lights and had a small support for a radar on top. There was also a gaff supporting the main combat flag and extra signal flags. Next came the rear superstructure amidships and single raked and topped funnel. Access to the rear was typical of US destroyers to keep the aft deck dry: It was accessed though a bulwarked wall with door.

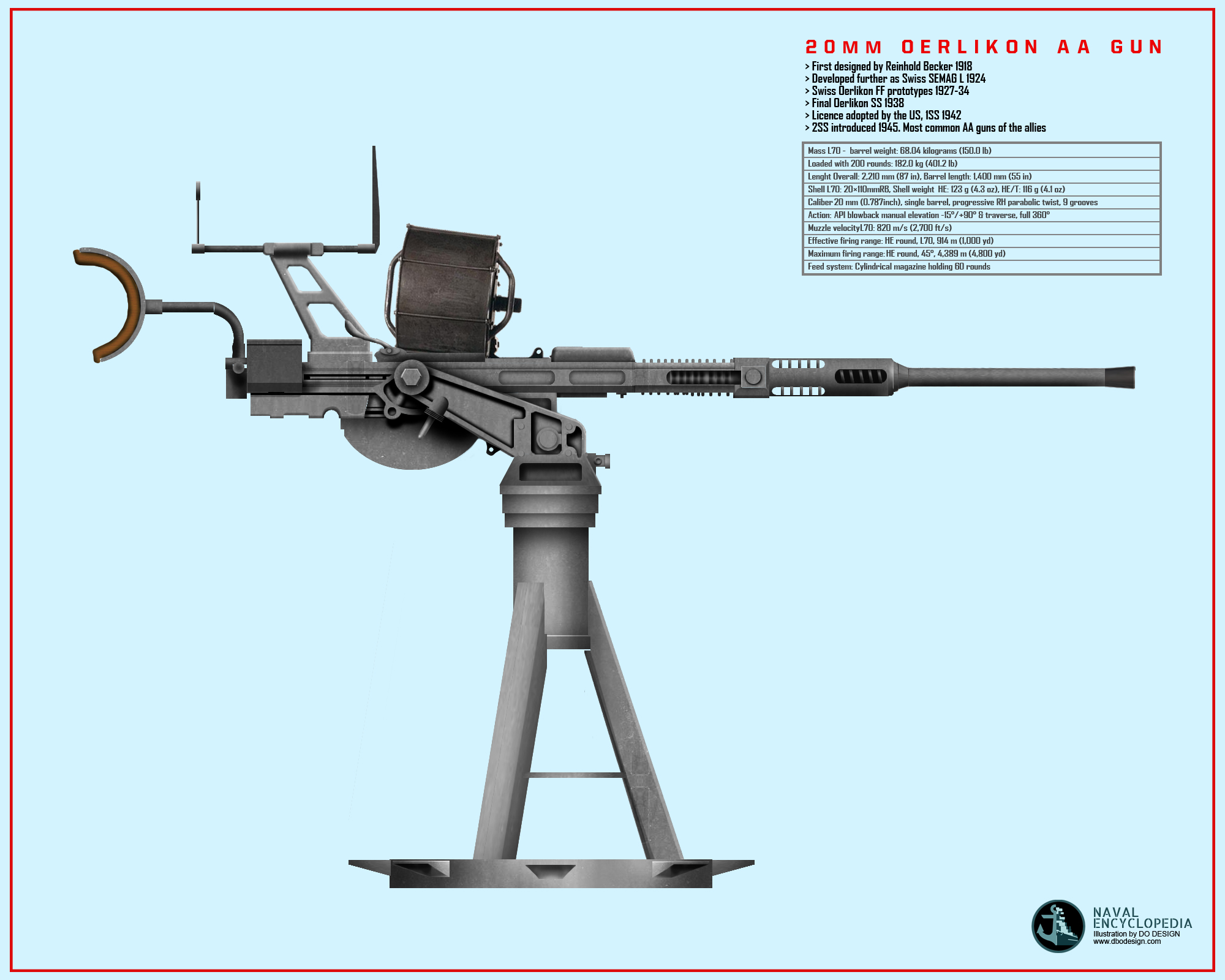

The rear structure supported the aft 3-in gun position, in an upper position. Just aft of the funnel were located several Oerlikon 20 mm AA gun positions. Later in service, to these six amidship positions were added a Bofors mount aft, and three more 20 mm positions close to the bridge, covering the forward quarter. Indeed, the amidship mounts had a poor arc of fire forward due to the tall bridge. These ships had limited space and only carried an unpowered, open whaler for rescue and liaison at sea, under davits on the starboard side. There were four main rafts of the Carlin type as well, installed at the foot of the bridge forward, and two amidship aft.

Powerplant: GM 61-278A

Official documentation of the GM 61-278 cross-section (pinterest)

The sticking point of these designs was of course their powerplant. The GMT meaning “GM Tandem” relied on a diesel-electric drive, and electric distribution, and thus, gearbox. This was to give them a longer range and far more flexibility to operate. In practice, this traduced into the need of four General Motors Model 16-278A diesel engines. They were coupled with an electric drive on two propellers. The Diesel GM 16-278A was created in 1938 in the Cleveland Diesel Engine Division of General Motors. It was a pure Marine diesel engine, 2-stroke, and scheduled to be used on submarines, tugboats, Patapsco-class gasoline tankers, but also destroyer escorts. The problem was there were never enough.

The primary drive was to replace the older Winton Model 201A, deemed unreliable. The 16-201A was designed to go on submarines, notably the Porpoise class in the USN. The Model 248 at large was offered in 8, 12 and 16-cylinder in V type layouts. In all case, it was a two-stroke, Uniflow-scavenged engine using a gear driven Roots blower forward, providing aspiration for the cylinders. This was also a medium speed marine diesel, originally designed to operate at 750 rpm.

Displacement was increased on the Model 248A with prewar production redesign for simplification resulted in the Model 278 which diverged by its aluminium pistons. It was then redesigned again for increased cylinder displacement and horsepower, creating the 278A, this tome with steel pistons, freeing aluminium for aircraft production. The Model 278A in the case of these GMT class ships was of the 16-cylinder variant. It remained in production until 1950 and parts provided for maintenance for a decade afterwards.

Four were distributed to each of the 97 Evarts-class destroyer escorts including 32 Captain-class. They were all identical, but were completed by:

Two 8-268A (350HP) electrical systems

Two 3-268A (150HP) electrical backup system while docked.

The Cannon class had the same arrangement.

This procured a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) with many ships proving they were capable of 21–22 knots on trials. As for range, it was good for such small ships, at 5,000 mi (4,300 nmi; 8,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). Based on a diesel oil storage between 131 and 197 tonnes, the range was also declared of 6,000 nautical miles at 12 knots.

For perspective, in one go, this was enough for a New-York to Alexandria trip without stopping. In reality, it fell rapidly, as these boats never maintained a steady speed during the trip. As good shepherds, they used to venture in and out of the convoy and do prolong ASW chases for long hours with good reliability and easy maintenance, pick up men of sunken ships left behind, and then return to the convoy at flank speed. Plus, there was the added advantage of having four powerplants for redundancy. See also

Protection

USS Charles R. Greer (DE-23) underway at sea circa in 1945 (AI colorized)

Being escort ship, they had, like destroyers, no armour to speak of. Meaning any 8,8 cm round from the Type VII would enter any point of the hull or structures like butter, same even for 20 mm FLAK rounds. But a surfaced U-Boat would have to deal with four fast-firing 3-in main guns and be overwhelmed by the fire of seven combined many 20 mm Oerlikon. So the accent was made on damage control underwater. Like all vessels of the time, they received heavy compartmentation with bulkheads completely separating the engine room with two pairs of diesels separated one from the other, and from the drive unit, and fore and aft section of the ship. On paper, they could survive even with their bow or stern severed, a case which was shown by many destroyers in WW2.

There were side compartments that could be filled with oil, absorbing the blast damage, and a double hull. However, the main guns were unprotected. The Oerlikon AA guns had the standard flat shields.

Armament

The early configuration of DE13-18 showing a 28 mm Quad Mark I aft, three main guns, including two forward and no Hedgehog, then nine 20 mm AA gun (casemate pub.)

As ASW escorts built in US, despite British initial requirements, they were armed with US ordnance, enough to deal with surfaced or submerged U-Boats and to repel any air attack, as the main 3-inches guns were dual purpose and could deal with the possible FW-200 Condor of the Luftwaffe at high altitude. To deal with lower altitude attacks, there wee an array of 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns. This was rounded by the new standard Hergdehog Mark 1 anti-submarine mortar for a quick reaction, post-diving attack, used typically when a U-Boat was spotted at a distance, making for the deep. And for passes on long hours of gruelling chase, they were generously provided with 160 Depth Charges at a maximum, dispensed by two stern racks and six to eight side projectors (Y-Guns or Depth Charge Thrower).

3 inch/50 Mark 20 guns

If the Mark 2 entered service all the way back to 1915, the Mark 20 was a much more modern variant nearly at the end of the line, of successful dual purpose light-medium 76 mm naval guns. Always un protected and on single mounts, they could elevate to +85° giving them a range of 14,600 yd (13,400 m) at 43° elevation and 30,400 ft (9,300 m) AA ceiling. They needed a crew of a few men only with one gunner using a peep-site and Optical telescope. The Mark 20 was capable of around 20 rounds per minute, with manual loading and ramming. They had 13 pounds (5.9 kg) HE shells easy to handle, and existed in AP, AA with VT promixity fuze in 1944, and HE or illumination, with some of the latter always ready to counter the surface night tactics of U-Boats. It’s unlikely the Mark 20 were replaced at any point by automated Mark 22 (1944).

28mm/75 Mk.1

Shortage of Bofors forced the installation (according to navypedia) of the infamous “Chicago Piano” Mark 1 for DE13 to D18. The compensated by having no less than nine 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns.

The 28mm/75 calibre gun, Mark 1, was an early U.S. Navy anti-aircraft (AA) autocannon system developed in the 1930s as part of an effort to provide ships with more effective defence against increasingly capable aircraft. Despite its innovation for the time, the system was ultimately unsuccessful and was quickly rendered obsolete. This quadruple automatic anti-aircraft gun mount had an intermediate caliber of 28 mm (1.1 inch) for a barrel Length of 75 calibres (~2.1 meters) and the Quad-barrel mounting was probably the Mark 1 Mod 2 capable of 125 rounds per minute per barrel (cyclical), lower in practice at 2,700 ft/s (823 m/s) for an effective Range of c3,000 yards (2,700 m) against aircraft. It was fed by 5-round clips. The nickname came from the quad-barrel configuration, resembling a pipe organ or gangster-era machine gun. It was intended to bridge the gap between .50 calibre machine guns and heavier 3″/50 or 5″/38 dual-purpose guns.

40mm/56 Mk 1.2

The ubiquitous heavy puncher and perhaps the best AA gun of WW2 at least on the allied side. A twin mount was installed aft on the superstructure.

The 40 mm (1.57 in) Bofors needs no presentation, legendary for its hitting power and reliability, it is still in service today. This 56 calibres (2.24 m/7.35 ft) gun has a rate of Fire of 120 rounds/min (cyclic) and 80–100 effective, only limited by the manual handling of the 4-round clips, gravity-fed. Muzzle Velocity is 881 m/s (2,890 ft/s) and effective range 5,000 m (5,500 yd) against aircraft. The Mk.1 was the Twin mount, mostly unshielded unlike the Mark 2 quad mount.

Read more

20 mm/70 Mark 4 Oerlikon

On the GMT class they were distributed on several positions aft of the funnel initially, but the standard by 1944 was to have

Read More

Depth Charges

Standard issue were eight DCT (Depth Charge Thrower or K guns located aft on either side, four facing the aft quadrant and four facing the broadside. This was completed by two 10-DCs depth charge racks aft for a grand total of 120 up to 160 depth charges. This was enormous and larger than any other US ship, denoting of their speciality. Before the arrival of the Hedgehog installed in place of “B” mount, this was their only ASW armament.

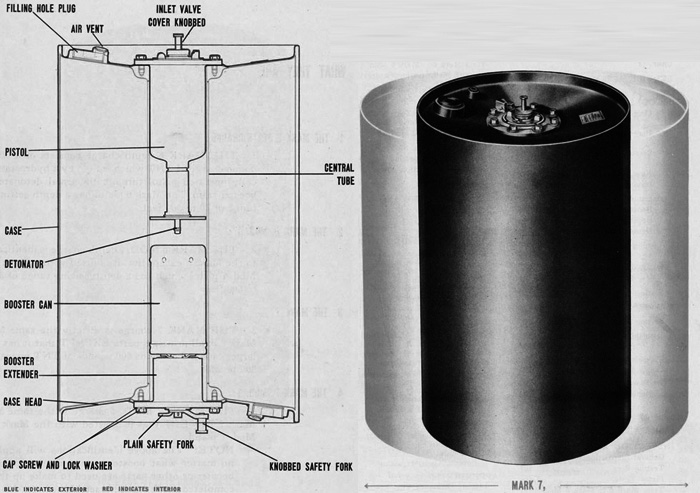

Mark 7:

The models used were likely the Mark 7 as completed. Design in 1937 and entering service the following year, they weighted 745 lbs. (338 kg) and carried a 600 lbs. (272 kg) TNT warhead worth a sink Rate and Terminal Velocity of 9 fps (2.7 mps). It had settings from 50 to 300 feet (15-91 m).

Basically a redesigned Mark 4 which became standard on all destroyers, Destroyer Escorts and ASW ships in the early part of World War II. Its redesign was for simplifying construction. Mod 1 arrived from August 1942 and doubled the depth setting to 600 feet (183 m) given reports of U-Boats capable of reaching more than 250 m. Mod 2 had a warhead ported to 400 lbs. (181.4 kg) TNT with a greater sink rate of 13 fps (4 mps).

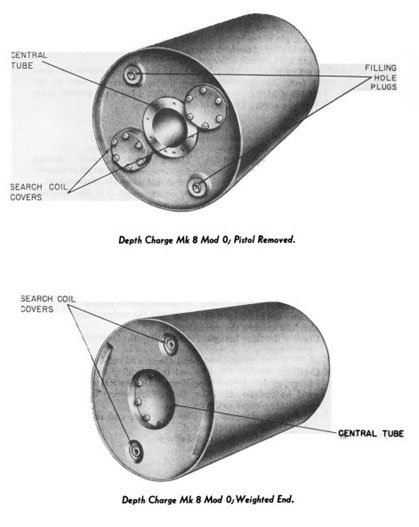

Mark 8:

Designed in 1941 and introduced in 1943, this model used a magnetic pistol and was built with an aluminium casing to avoid magnetic interference. This was far more advanced “proximity” model, far more accurate than preset depth charges of old. Weighting “only” 525 lbs. (238 kg) it still carried 270 lbs. (122 kg) of TNT and had a sink rate of 11.5 fps (3.5 mps) with settings between 50 and 500 feet (15-152 m). The USN considered it 7x more lethal than the Mark 6 or even the following Mark 9. But when it exploded…

It was indeed unreliable and maintenance-heavy. So much so that a backup hydrostatic pistol was fitted and by 1945 the model was retired from service. The magnetic pistol armed itself when detecting the hull from 35 feet (11 m) to 200 feet (61 m) and then exploded when 20-25 feet (6-7.5 m) close. Too light, it was assorted by 150 lbs. (68 kg) lead weight. Great hopes were placed on this model, almost a USN “secret weapon” to win the war in the Atlantic, with 76,000 built, but crews soon discovered its flaws, and it was quickly withdrawn after the war with some 57,000 still in storage by September 1945.

Mark 9:

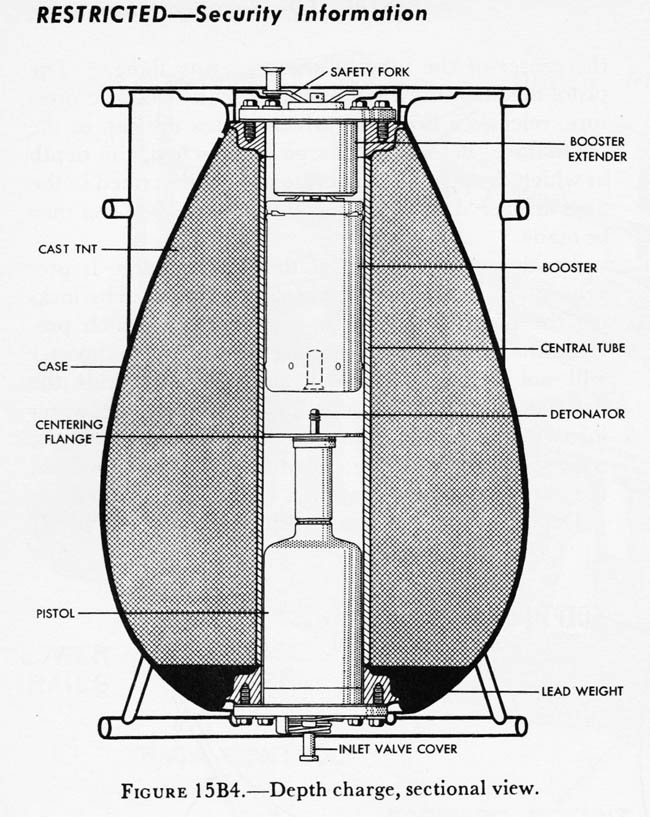

Same generation as the Mark 8, this became the standard-issue DC from 1943 to 1945 and well beyond. Essentially similar technically as the previous Mark 7, they had however a “teardrop” shape enabling as tested a much greater sink rate, with fins to create a stabilizing spin enabling it to even sink more accurately. The Mod 2 could be setup to 1,000 feet (305 m), the warhead TNT was replaced by Torpex and the sink rate could be reduced if needed to 15 (4.5 mps) by fitting spoiler plates on the nose, acting as brakes. They were provided as kits for slower warships (DEs, Frigates and Sub-Hunters), to allow them to escape the explosion plume.

Depending on the version, Mod 0, 1 and 2, it weighted 320 lbs./145 kg, 320 lbs./145 kg and 340 lbs. (154 kg) respectively, with a warhead ranging from 200 lbs. (91 kg) TNT to 190 lbs. (86 kg) on Mod 2. Sink rate also varied, respectively 14.5 fps (4.4 mps), same and 22.7 fps (6.9 mps).

Settings were about the same as the Mark 7, from 50 to 300 feet (15-91 m) or 600 feet (183 m).

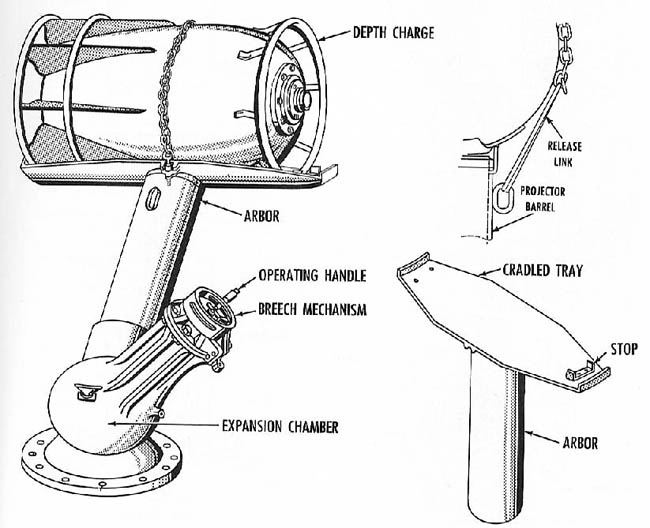

About the K Guns (Mark 6)

The USN standard Depth Charge Thrower (DCT) in WW2 could be either the Mark 6 or the Mark 9 “K-gun”. A successor to the 1918 “Y gun”, this new model was geared towards quick reload and more power to throw the DC as far away as possible from the ship’s hull.

The Projector Mark 6 was introduced in 1941, firing a single Mark 6, 9 or Mark 14 depth charge. Distances achieved range from 60 to 150 yards (55 to 137 m), in just 3.4 to 5.1 seconds. Generally all destroyers equipped had them placed by three either side aft on the deck, close to the aft deckhouse. Four to six for destroyers, but up to eight on destroyer escorts. They soldiered on until the 1950s and production was such they were also provided largely by lend-lease.

Each K-Gun was composed of an arbor (holder) inserted into the projector to hold the depth charge, loaded next onto it. It fell into the sea but was not recoverable, unless a cable was attached to it, but it was considered a hazard. They were expandable cheap metal pieces. These were partly made of a tube measuring 61 cm x 15 cm, closed on one end and ending with a tray 12 by 31 inch (30.5 x 79 cm) on the receiving end. It was conceived to fit into the projector barrel and became the main projectile when fired. They weighted at first 70 lbs. (32 kg) down to 65 lbs. (29.5 kg) on later models, increasing range.

The K-Gun propellant used was black powder. The arbor was loaded into a 3″ (7.62 cm) tubular casing. The loads varied between the ordered range, either 60, 90 and 150 yards (55, 82 and 137 m), varying the charge.

The Mark 9 was had a built-in arbor tested in 1944 on USS Asheville (PF-1), but the system was complex compared to expandable arbors, and it was too costly to justify production.

It is estimated that thousands of tons of arbors laid in the Atlantic seabed after WW2, probably now all rusted away as they received no special treatment.

Sensors

There too, it was pretty well rounded for their mission, covering all aspects surface, air and undersea passive or active detection.

SL Radar

Typical small 150 kW, 1300 lbs (590 kg) surface search radar designed for destroyer escorts.

The 300 lbs (136 kg)antenna was 45″ by 48″ (1.14m by 1.22m) parabolic in radome and PPi scope, 20 rpm and 100 feet/1 degrees accuracy.

Resolution 600 feet/6 degrees or 200 meters/25 degrees, 30 meters/1 degrees

Specs: Wavelength 10 cm, pulse Width 1.5 microsecond, Pulse Repetition Frequency 800 Hz

Range: 15 nm (30 km) low-flying bomber, 20 nm (35 km) cruiser, 13 nm (24 km) destroyer, 10 nm (20 km) submarine

829 SLs were manufactured in 1943-10, 480 SL-1 by 1944-7. They equipped the present destroyers and their successors. British crews were trained on them at first.

SA Radar

Standard small air search radar and first warning detector. Tailored for destroyers escorts and frigates, some were also found on destroyers. They were of the bed frame type, and relatively small. The SA-1 equipped rather destroyers.

Specs:

SA had an estimated reliable range of 40 miles on medium bombers at 10,000′, with antenna at 100′. Range accuracy is ± 100 yds. Bearing accuracy, ± 1° (lobe switching). No elevation.

The SA has 12 components and weighs a total of approximately 1500 lbs. The SA antenna measures 5′ x 8’8″. Including pedestal, it weighs 500 lbs.

The antenna should be mounted as high as possible, preferably 100 feet or more above the water, thus, on top of the mainmast of the GMT.

To operate, one operator per shift is required. PP required is 1950 watts at 115 volts, 60 cycles.

They were small enough to be fitted on sub-chasers and minesweepers as well.

See also

Type 128D SONAR

The type 128 was tested 1937 in Acheron. It was retractable, under dome, and also equipped the A, L, and Hunt-class destroyers. So it was only fitting it was provided for the early GMT class escort destroyer as well. It was equipped with a range recorder and could be controlled from the bridge. However, it was discarded as soon as the more modern Type 144 was available.

Type 144 SONAR

This improved sonar set had a fixed gyro-stabilized oscillator using a gyro compass for bearing indication. It is fully integrated with the Hedgehog or later Squid ASW mortars. The Type 144Q later appeared with a second oscillator trained with the main oscillator, but elevated down further for close range, around 400 yards. The 144 had a much better range of 2800–3000 yards (1800-2800m) depending on conditions. The ship needed to go slow to use it without many interferences. Note that some sources specifies a QGA sonar, US-pattern. It was perhaps installed postwar.

HF/DF

To detect enemy radar or radio emission and triangulate positions, the mast was topped by the characteristic cross-style antenna of the “Huff-Duff”, a British model built in the US as the FH 4 antenna. It was used as a MF Direction Finding array.

⚙ GMT Destroyer Escort specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1192t standard, 1,360-1,416 tons (fully loaded) |

| Dimensions | 289 ft 6 in x 35 ft x 9 ft (88.22 x 10.7 x 2.7 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 4 × GM Model 16-278A diesels, electric drive |

| Speed | 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) (top 21–22 knots) |

| Range | 5,000 mi (4,300 nmi; 8,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 3× 3 in/50, 7× 20 mm AA, Hedgehog, 160 DCs |

| Sensors | SL, SA radars, Type 128D/Type 144 ASDIC, HF/DF FH 4a |

| Crew | 156 |

Misc. aspects on the GMT class

Naming

The GMT class were named after recently died USN servicemen, in a way to honour families and for maintaining the esprit the corps. Only those awarded a special decoration posthumously or citation, such as the Navy cross, were considered. The lead ship DE-5 was named after Milo Burnell Evarts, born 3 September 1913 in Ruthton, Minnesota, enlisted in the Naval Reserve 31 August 1940, and was commissioned 12 June 1941 as ensign. On the night of 11-12 October 1942, in the Battle of Cape Esperance, Lieutenant (junior grade) Evarts was killed in action when his ship, light cruiser BOISE (CL-49), was damaged. Disregarding the danger of explosion from the fires which broke out in the gun turret of which he was in charge, Evarts stood to his station until killed. He was

The GMT class were named after recently died USN servicemen, in a way to honour families and for maintaining the esprit the corps. Only those awarded a special decoration posthumously or citation, such as the Navy cross, were considered. The lead ship DE-5 was named after Milo Burnell Evarts, born 3 September 1913 in Ruthton, Minnesota, enlisted in the Naval Reserve 31 August 1940, and was commissioned 12 June 1941 as ensign. On the night of 11-12 October 1942, in the Battle of Cape Esperance, Lieutenant (junior grade) Evarts was killed in action when his ship, light cruiser BOISE (CL-49), was damaged. Disregarding the danger of explosion from the fires which broke out in the gun turret of which he was in charge, Evarts stood to his station until killed. He was

posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for his unyielding devotion to duty.

The Navy Cross is the second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. Created in 1919 it is bestowed by the Secretary of the Navy. More common are selected men in the largest pools recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, and Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

There were also recipients of the Silver Star:

The second ship of the GMT class (DE6) was named after Lawrence Edward Wyffels, born on 20 January 1915 in Marshall, Minnesota. He enlisted in the USN on 17 March 1936, served on USS Enterprise (CV-6) and advanced to carpenter on 25 June 1942. He was killed in action on 26 October 1942 when Enterprise suffered bomb damage at the Battle of Santa Cruz Island. Disregarding his own safety, Carpenter Wyffels courageously fought the blaze ignited by bombs and repeatedly entered burning compartments to rescue the wounded trapped inside. Carpenter Wyffels was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for his intrepid devotion to duty.

However, there is a “club within the club” for destroyer escorts named after MoH (Medal of Honour) recipients. The Navy and Marine Corps’ Medal of Honour is truly the highest award decoration, but it changed a lot since it was created for enlisted men by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles on 16 December 1861. It was presented only for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty”.

However, there is a “club within the club” for destroyer escorts named after MoH (Medal of Honour) recipients. The Navy and Marine Corps’ Medal of Honour is truly the highest award decoration, but it changed a lot since it was created for enlisted men by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles on 16 December 1861. It was presented only for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty”.

General Evaluation

As the trailblazer for 560 destroyer escorts all very similar, the Evarts proved excellent for convoy escort in all configuration and for any threat, both in detection and firepower.

They were quick and cheap to build and thus became vital for wartime production surges with over 97 built for the GMT alone. Production was even further simplified and processes, parts supply streamlined to accelerate further construction times. It was halved in 1945.

Despite their tall bridge, the gravity calculations and all weights down into the hull helped in general to keep a stable sea keeping: Despite their small size, they were reasonably good in rough Atlantic conditions. They also proved a god of survivability with a smaller profile compared to an average destroyer and a well compartmentalized hull helping them absorb damage better than expected. However, they had weaknesses such as their still limited speed and firepower: They proved very vulnerable to surface ships and their AA was deficient against combined aircraft attacks.

The one-shaft design of some of “short-hull” versions was also criticizes. They were also cramped and offered uncomfortable living conditions during long deployments.

As said at the start, they served in both Atlantic and Pacific theatres, they proved critical in escorting convoys to Europe and North Africa, started with all 1943 Mediterranean operations, notably Husky, and the 1944 Italian landings, also protecting convoys against German U-boats from the US to Britain to prepare D-Day.

USS Sederstrom fitted out at Mare Island in July 1943.

As Germany was almost defeated in the spring 1945, many of the ex-Europan theater’s GMTs were sent to the Pacific, as well as many of those completed in 1944. They saw combat in the latter part of the island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific, and were featured at Okinawa and Iwo Jima (proving ill-equipped to face Kamikaze). But of course their greates contribitionwas to the Royal Navy as the Captain-class frigates. They arrived at a crucial time for the RN to win the Battle of the Atlancic, proving as capable as the Hunt class.

However in 1945 their legacy is stained by the fact they started a whole lineage. Much was learned to modify latter classes, more capable and better armed such as the Buckley and Cannon classes.

(More to come in next updates)

Appearance

USS Halloran (DE 305) showing her freshly painted MS ??? camouflage on 7 June 1944 at Mare Island.

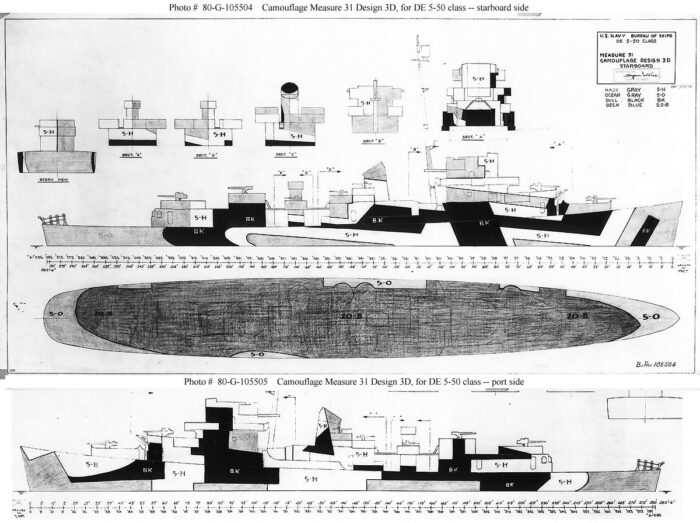

In terms of camouflage, measures consisted in the following:

Order CF-160: MS 32/3D external for the class and under order CF-161, measure 31/1D for the details and decks (vertical surfaces)

Order CF-4 from May 1944 precise 32/9D for the horizontal surfaces and CF-5 (MS 32/21D) was applied from December 1943.

Order CF-6 was applied from January 1944 for measure 31/3D and CF-88 for MS.33a/35D from March 1945.

Order CF-184 for MS 3-/22D was applied from December 1943. Order CF-185 for MS.32/6D was applied in 1944.

See more

USS Evarts for example was applied MS 21 as completed, all Navy blue. It was colourful mix of patterns and styles with MS 31/3D from 1944.

MS 21:

Navy Blue 5-N for all Vertical surfaces without exception. Horizontal Surfaces Deck Blue, 20-B. Wood decks be darkened to the colour Deck Blue. Deck Blue paint shall be used in lieu of stain.

MS 31/3D:

Paint all exposed vertical surfaces a pattern of Haze Gray 5-H, Ocean Gray 5-O, Black. Horizontal Surfaces, all decks and horizontal surfaces with Deck Blue, 20-B and Ocean Gray 5-O.

Canvas covers visible from the outside vessel dyed to Deck Blue.

DE-5-50 MS31/3D, preferred by modellers. This particular scheme was applied with variations.

profiles awaited

Preserved: USS Slater

No Evarts class was preserved, however a single DE represents in the US the entire 500+ mass of these. Since there were many similarities between all these ships, it is a precious source of information. The USS Slater (DE-766) is a Cannon-class destroyer escort that has been meticulously restored and preserved as a museum ship. It’s one of the last remaining destroyer escorts afloat in the United States and serves as a powerful tribute to the sailors who served aboard similar ships during World War II.

Commissioned: May 1944 and named After Frank O. Slater, a sailor killed during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, this Cannon-class was active in the Atlantic Ocean during WWII, and is now preserved at Albany, New York, moored on the Hudson River near downtown.

It is currently operated by the Destroyer Escort Historical Museum, and has been fully restored to her WWII appearance, down to authentic paint schemes, weaponry, and interior details.

In fact, it underwent one of the most comprehensive naval vessel restorations in the country, largely by dedicated volunteers and naval veterans, of these 500+ vessels that left neglected (in contrast more destroyers of WW2 had been preserved). It is opened seasonally for guided tours, which include access to the ship’s bridge, gun mounts, crew quarters, engine room, and more.

Visit the website

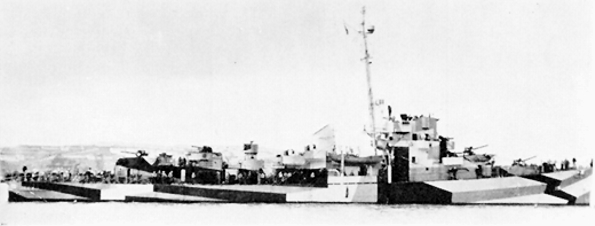

The British GMTs: Captain class

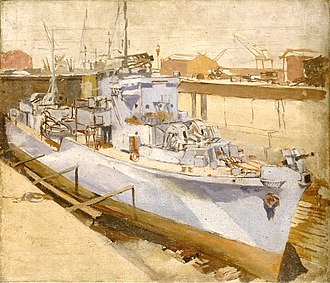

HMS Lawford in 1944 (IWM). The Captain class are somewhat preferred by modellers, given their large choice of camouflages. It was rather dull for the GMT in US service

“Our story starts back in 1940 when the German Army overran Norway and France which enabled them to station their U-Boats in Norway for easy access to the Arctic oceans, and on the west coast of France which gave them the gateway to the whole of the Atlantic Ocean. It was now the period when Great Britain stood alone against the might of the Nazi war machine, and with their U-Boats starting to make themselves a nuisance in the Atlantic, they were also starting to produce new U-Boats at an ever-increasing rate. Great Britain in 1941 found herself short of suitable escort vessels capable of deep ocean convoy duties having to rely on corvettes, a few sloops, trawlers and occasionally fleet destroyers which were not as plentiful since their heavy losses during the first year of the war.

In September 1940 after approaches by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the President of the USA Franklin D. Roosevelt authorised the exchange of fifty old first world war four stack flush deck destroyers from the US Navy reserve fleet for ninety-nine year lease of six Caribbean Islands, these old destroyers were really past their best and many spent a lot of time in repair yards with constant breakdowns. As for their crews who spent a lot of their time at sea wet through due to them shipping seawater which found its way down to the mess decks, but they helped to fill some of the gaps in our escort fleet until the arrival of new ships.

HMS Curzon in 1945, showing another camouflage, note the extra AA guns fully elevated

In March 1941 the USA Government passed the Lend/Lease Act which would enable Great Britain to procure merchant ships, warships and munitions etc; to help with our war effort. In June 1941 Britain asked the USA to design, build and supply an escort vessel that was suitable for anti-submarine warfare in deep open ocean situations. The United States Navy had been looking into the feasibility of such a vessel since 1939 and a Captain E.L. Cochrane of the Bureau of Shipping who during his visit to Britain in 1940 looked at our Corvettes and Hunt Class Destroyers had come up with a design for such a vessel, so when Great Britain came along with their request the US Navy decided to put the plans into motion.

Captain Cochrane had to make several alterations to his original design and method of production but in the end came up with the finished article at half the cost of a fleet destroyer. President Roosevelt authorised the construction of the new vessels in August 1941.

Orders for fifty units were placed with four shipyards in November 1941 at Boston, Mare Island, Philadelphia and Puget Sound, and were initially designated British Destroyer Escort (BDE) but this was reduced to Destroyer Escort (DE) when the United States entered the war, and of course they found they also required an Anti-Submarine warfare ship and the DE fitted their needs perfectly, which resulted in a system of rationing whereby out of every five DE’s completed four would be allocated to the US Navy and one to the British Royal Navy. By the middle of 1943 1,005 of these ships had been placed on order, but only 563 were finally built, the rest being cancelled. Those that were built were distributed between six classes mainly distinguished by their power units and various armaments, these were Evarts, Buckley, Cannon, Edsall, Rudderow and John C. Butler, but here we are only concerned with the Evarts and Buckley classes as these were the only types used by the British Navy. All the British ships bar one were built at Boston, the Evarts at the Charlestown Navy Yard and the Buckleys in the newly built Bethlehem Steel Yard at nearby Hingham.

Of the 563 ships built, the British Royal Navy received 32 Evarts and 46 Buckleys. The Free French received 6 Cannon Class (after WWII permanently transferred to the French Navy). The US Navy used the huge balance of 465 the largest number of which served in the Pacific theatre of the war.

Although these vessels were to be produced mainly for anti-submarine warfare the US Navy designated them as Destroyer Escorts and in addition to their Anti-Submarine weapons they were fitted with torpedo tubes on the superstructure midships, thus sticking to the Destroyer mentality.

The British on the other hand viewed these ships as unequivocally anti-submarine units, so the use of torpedo tubes did not arise, and as they were of a smaller size than a Destroyer they designated them as Frigates. The Lords of the Admiralty in their wisdom dubbed these ships as “Captains Class Frigates”, (note the plural Captain) but during conversations between individuals the name always got spoken as singular Captain, which seems to come easier to the tongue. The Admiralty when searching for individual names for the ships put very old names to the most modern vessels, and used the names of captains of the period covered by the Napoleonic wars.

Sub Lieutenant Anthony Large, BEM, South African Naval Force (Volunteers), of Durban, South Africa, taking a bearing on the ship’s compass on board HMS HOLMES whilst she was helping to guard the Allied supply lines to and from the Normandy beachhead. He won his British Empire Medal as a rating.

HMS Thornborough in 1944 (IWM)

The Captain-class frigates were a group of 78 warships that served primarily with the Royal Navy during World War II, though they were originally built in the United States as part of the Lend-Lease agreement. These ships were based on the U.S. Navy’s Buckley-class and Evarts-class destroyer escorts, but were classified as frigates in British service.

Built under Lend-Lease they remained in Service with the Royal Navy in 1942–1945 with a total of 78 frigates built at Evarts-class and Buckley-class destroyer escorts.

Their roles included convoy escort, ASW, patrol and training. They were powered like the Evarts in Diesel-electric but later Captains used turbo-electric if ex-Buckley.

They were armed by three 5-inch guns, had US patten depth charge throwers, and British Hedgehog ASW mortars.

Top speed was 20 knots for a crew of 180 officers and men.

The Captain class were a generic name for a variety of different ships, the Evarts-class were called the “Short-hull” Captain-class and ran on Diesel-electric (32 total) and the Buckley-class were called the “Long-hull Captain” and used Turbo-electric drive, with 46 ships transferred.

HMS Riou in 1944 (IWM)

The Naming Convention was after famous Royal Navy captains, of the Napoleonic era and in particular those that served under Admiral Nelson such as HMS Bentinck (K314), HMS Essington (K353), HMS Hotham (K583), HMS Holmes (K581). They concentrated on Atlantic convoy escort duty, either as direct escort or hunter-killer groups against U-boats but also took E-Boat escort missions before, during and after the Normandy Invasion (D-Day) in support and coastal operations as well, and remained in hunter-killer groups with escort carriers until 1945, but many also served in the English Channel and North Sea, as they were too small for the Atlantic escort. Their primary area of operation was around the British Isles, Bay of Biscay and Irish Sea, or the GIUK gap (Faroe-Greenland-Iceland). None was preserved as museum ships, albeit they played a vital role alongside the River and Flower class in the Battle of the Atlantic, protecting Allied shipping. After the war, most were returned to the U.S. Navy and scrapped or sold off as surplus. They were however mass-produced with some shortcoming in production, so never intended for durability. This is still a very limited amount of service of three years on average.

There will be a dedicated article on them in 2026 or 2027.

Career of the GMT class

USS Evarts DE-5 (1942)

USS Evarts DE-5 (1942)

USS Evarts was laid down at Boston Navy Yard on 17 October 1942, launched on 7 December 1942 and completed on 5 April 1943. She was the lead ship of her class and more than 500+ destroyer escort built until the last day of the war. Initially when launched, she was intended for transfer to Great Britain (BDE-5). But she was later retained for use in the U.S. Navy, and commissioned on 15 April 1943, under command of Lieutenant Commander C. B. Henriques, USNR. After antisubmarine training and experiments with radar in Chesapeake Bay, EVARTS began steady service as a convoy escort, during much of which she flew the flag of Commander, Escort Division 5. After five voyages to Casablanca, she sailed from Norfolk 22 April 1944 on her first run to

Bizerte. Two days before reaching that port, her convoy came under heavy attack by enemy torpedo planes, and EVARTS joined in the protective antiaircraft barrage which splashed many of the attackers.

During the homeward bound passage of this same voyage, on 29 May 1944, EVARTS was detached from the convoy to aid escort carrier BLOCK ISLAND (CVE-21) and fellow DE BARR (DE-576), both of whom had been torpedoed. She arrived at the given position to find BLOCK ISLAND had sunk, but screened BARR, under tow, to safety at Casablanca. A second voyage to Bizerte was uneventful, as were the one to Palermo and the three to Oran which followed.

Completing her convoy escort duties 11 June 1945, EVARTS acted as target in exercises with submarines at New London until arriving at New York 11 September. On 2 October 1945 she was decommissioned at New York. After limited reserve time, she was sold for scrap on 12 July 1946, after a career of less than three years.

USS Wyffels DE-6

USS Wyffels DE-6

Wyffels DE-6 was laid down on 17 October 1942 at Boston NyD, launched on 7 December 1942, like Evarts, and completed, commissioned on on 21 April 1943. Like her sister she was at first intended for transfer to Great Britain when laid down as BDE-6 but retained, redesignated DE-6 on 25 January 1943 and renamed Wyffels on 19 February. Lt. Robert Messigner Hinckley, Jr., was in command. After sea trials in April, she was in an escort from Boston (8 May 1943) and afterwards, exercises out of Bermuda. In June, she alternated Norfolk-based escorts with drydock time. On 27 June 1943, she departed Hampton Roads for the 1st of elevent wartime escort missions, escorting convoys in the Atlantic and to Mediterranean ports.

The first saw her sailing to, and return from Casablanca with investigation of sound contacts. On 29 July, she was detached to guard a tanker, SS British Pride, which had fallen behind after an engine failure. She circled her nervously in protection while repairs were made, and escorted the straggler back to her convoy, which slowed down a bit to enable her catching up. This arrived frequently given the age of many of these merchants, sometimes pre-WWI, running on coal at obligated minimmal speed.

Between August 1943 and April 1945, Wyffels apart a few exercises off New England, conducted ten escort convoy missions to and from North Africa in support of the campaign that from Operation Torch in November, ended with the capitulation in May 1943 for the entire Deutsche Afrika Korps and Italian Army of Africa. On her Atlantic crossings, she kept marshalling reluctant merchantmen, protected stragglers, investigated any contact or sound source. In winter and miserable, stormy weather, heavy seas, pitch dark skies and seas, she tried her best locating and protecting stragglers, complicating her task. The only good news was that this weather prevent U-Boat from catching up.

On 11 May 1944, Wyffels escorted UGS-40 (56 merchant ships) bound for Bizerte when after sunset, she was signalled to go on general quarters, with some escort ship laying smoke, and her own radar picked up approaching planes. Benson (DD-421) and then Evarts (DE-5) opened fire on a fully fledge axis attack, mostly torpedo bombers making a run at about 200 feet. Wyffels opened fire as they passed down her port side. One suddenly appeared out of the smoke, dropped an ill-aimed torpedo and disappeared. But at 21:24, Wyffels engaged a Junkers (Ju-88 ?) approaching her starboard bow at 100 feet altitude, and opened a blistering crossfire. Hit, the Junkers went on kamikaze mode, banked to the right, barely missing her. Next she was sfrafed by another passing directly over her forecastle and starboard and disappeared. The combat went on for 10 more minutes, not a single hit was recorded.

In 1944, Wyffels continued Atlantic convoys missions and by 1945 this was far more quiet. On 13 April 1945, Wyffels returned home from her last wartime convoy mission, informed that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died. She lowered her colors to half mast. After an overhaul to Charleston later she was sent to Miami on 11 May, operated off Florida and Bahamas as school ship for student crews in basic gunnery and ASW. On 28 August 1945, she was decommissioned, leased to the Republic of China as T’ai Kang. Transferred for good on February 1948 and active until struck on 12 March 1948. She was awarded a single battle star for her service, “Atlantic”.

USS Griswold DE-7 (1943)

USS Griswold DE-7 (1943)

Griswold DE-7 was laid down on 27 November 1942, launched on 9 January 1943 and commissioned on 28 April 1943. She was named after Don T. Griswold, Jr. born 8 July 1917 in Bryan, Texas (Iowa State school, Naval Aviation Corps). On 6 June 1942 at the Battle of Midway, his Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless scored a hit on IJN Mogami but shot down by AA fire and posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. More

She was intended for Pacific service unlike her earlier sisters, for which she was awarded three battle stars. After shakedown in Bermuda, she was prepared and departed Norfolk for the Panama canal, then Bora Bora, Society Islands, in July 1943. She escorted convoys through the South Pacific until April 1944. On 12 September, she chased an IJN submarine in a 4-hour attack. Although debris and an oil slick rose to the surface, she was not credited the kill (unconfirmed postwar by Japanese sources).

3 months later she recorded a kill. It started at 22:00 on the night of 23 December off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal. She investigated a periscope sighting with sonar operators picking up the contact and spent next 5 hours attack after attack until oil slicks and air bubbles after the 7th attack told her she had a hit, confirmed shortly before 03:00 on 24 December when a periscope poked out of the water. She then led an 8th attack, with 12 depth charges and spotted an heavy oil slick dotted with debris which rose to the surface; It was later confirmed as I-39.

After overhaul at Mare Island, she was back in the Pacific on 3 June 1944 between escort missions and training off Pearl Harbor into 1945. From 12 March to 6 May 1945, she was stationed at Eniwetok, as flagship, Commander, Task Group 96.3, Comdr. T. F. Fowler. She sailed later for Okinawa, arrived on 27 May, commanding the ASW screen, shooting down two kamikaze on 31 May and 5 June. On 29 June she departed Okinawa escorting a convoy to Leyte Gulf, then Ulithi for screening work. She was present in Tokyo Bay on l0 September. She was back at San Pedro in California on 8 October via Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor. She was decommissioned there 19 November 1945 and was struck from the Navy List 5 December. Scrapping after she was sold, commenced on 27 November 1946.

USS Steele DE-8 (1943)

USS Steele DE-8 (1943)

USS Steele (DE-8) was laid down on 27 November 1942, launched on 9 January 1943 and completed, commissioned on 4 May. She was named after Lyman Steele, a Marine Corps officer who was killed during the Battle of Belleau Wood in World War I. In 1943–1945 she served primarily in the Pacific Theater. She also conducted escort missions between U.S. West Coast, Pearl Harbor, and forward bases. She screened convoys and supported operations in areas including Eniwetok, Majuro, Kwajalein, and Ulithi, performed anti-submarine warfare patrols, assisted in search and rescue operations. She was discarded on 21 November 1945, struck from Navy List on 5 December 1945, sold for scrap in 1947. She gained 2 battle stars.

USS Carlson DE-9 (1943)

USS Carlson DE-9 (1943)

USS Carlson (DE-9) was laid down on 27 November 1942, launched at Charleston NyD on 9 January 1943 and commissioned on 10 May 1943. She was named after Chief Machinist’s Mate Daniel William Carlson (1899–1942), killed at the Battle of Midway aboard USS Hammann. Carlson was assigned to the Pacific fleet during World War II, spent time as convoy escort, taking part in Guadalcanal and northern Solomon Islands campaign, Okinawa campaign and the Battle of Iwo Jima.

From 6–17 April 1945 from Okinawa to Saipan and back she escorted transports and reinforcements, and was on screening station between Okinawa and Kerama Retto. A dangerous assignement: The first night, she was attacked by a torpedo bomber, narrowly dodged her by the bow. Three more times over next two weeks her AA gunners repelled other attacks. After another trip to Saipan she screened on various stations off Okinaw under heavy kamikaze attacks with one fighter hitting Carlson. But it hit the water first, and lost all momentum before striking her hull, and failed to explode so famage was light. She left Okinawa on 29 June 1945 for Leyte and the replenishment group for TF 38. On 16 September she headed home for San Pedro in California. She received two battle stars for World War II service. She was decommissioned, discarded on 10 December 1945 and Sold 17 October 1946.

USS Bebas (DE-10)

USS Bebas (DE-10)

USS Bebas was laid down on 27 November 1942, launched a Boston NYd on 9 January 1943 and commissioned on 15 May 1943. She was named after Gus George Bebas, born on 24 February 1914 in Chicago, Illinois, ensign in the USN reserve in 1938 and Curtiss SBC Helldiver pilot in VB-8), USS Hornet, and at Midway on an SBD, he narrowly missed Tanikaze and scored a near miss on Mogami, earning a DFC. He was killed in training on 19 July 1942. Completed as BDE-10, Bebas was reallocated to the USN. After Bermuda training and shakedown, fixes at NyC, in June and back to Bermudan in July, she started missions of coastal escort from Casco Bay, Maine, and Boston, New York, Norfolk. She left Hampton Roads on 24 August for the Pacific, Panama on 1 September, Galapagos, Society Islands and arrive dat Espiritu Santo (New Hebrides) for operations in October-November and escorts to and from Nouméa (New Caledonia) and then to Guadalcanal. She assisted the bombed Liberty ship John H. Couch on 11-12 October. It happed while off Lunga and Koli Points, Guadalcanal after she investigated a “fire explosion at sea”. She recovered her crew and shelled her.

Next she was picked up for “killer operations and local escort” duty under the Fiji Island garrison, until January 1944. She then returned to the Solomons, New Hebrides, New Caledonia areas and in April was back home for overhaul at Hunters Point. She departed on 30 May via Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Islands, Eniwetok, 27 June and until late July and was in another hunter-killer task group around USS Hoggatt Bay (CVE-75), in the Western Carolines and and Philippines, Leyte, then Palaus-Ulithi by October, and after refit at Espiritu Santo returned to the Palaus, Ulithi, Eniwetok in 1945. On 2 February 1945 she escorted the tankers USS Cossatot (AO-77) and SS Egg Harbor for Ulithi and two nights later her radar operaor picked a “definitely suspicious” contact, that she sailed to investigate after permission, signalling general quarters. She made a hedgehog attack then another, until her sonar operator heard one sharp and two muffled detonations, this was then followed by a 3rd “hedgehog” pattern but one hour later she spotted long wood fragments and made a box search through the night. A PBM Martin Mariner joined the search over 600 square miles (1,600 km2) until an oil slick was found on the previous night attack site. USS Bond (AM-152) joined her to continue the hunt until it was closed off on 6 February. No kill confirmed postwar.

She then took part in the invasion of Okinawa, and on 12 May, rescued Lt. Robert R. Klingman, USMC, of VMF-312 (F4U Corsair) and tried to protect USS New Mexico (BB-40), killing one “Oscar” crashing nearby. She screened refueling groups for carrier strikes and returned to Hawaii for overhaul from 3 August, learning V-day on the 15th. On 4 September she headed for the west coast of the United States, San Francisco on 9 September, San Pedro, decommissioned on 18 October 1945, stricken on 1 November 1945, sold in January 1947 for scrapping. Three battle stars.

USS Crouter (DE-11)

USS Crouter (DE-11)

USS Crouter was laid down at Boston NyD on 8 February 1942, maunched on 26 January 1943 and commissioned on 25 May. She was named after Mark Hanna Crouter (born 3 October 1897 Baker, Oregon), USN Academy 7 June 1919, XO on USS San Francisco, KiA at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. She was deployed to the Pacific, escorted convoys to and from Nouméa, from September 1943, to Efate and Espiritu Santo, Viti Levu (Fiji Islands) and between Nouméa and Port Purvis, Florida Island (Solomons) until March 1944. After home overhaul she departed Pearl Harbor for Eniwetok in June-July 1944 an back to Pearl Harbor for ASW exercises, rescuing men from a crashed PBY Catalina on 15 July. She operated with submarines from Majuro from 13 August and 24 October 1944 and was at Eniwetok on 26 October for escorts to the Ulithi Atoll, Kossol Roads, Saipan until 15 March 1945. In the Philippine Islands she joined the transport convoy for Okinawa, and arrived on 1 April 1945 for the invasion. She joined a hunter-killer group from 19-28 April 1945 and claimed two aerial kills. She was back in training with subs in Guam on 21 May 1945, until 18 September 1945. Decommissioned 30 November 1945, sold for scrapping on 25 November 1946, BU 1947, 1 battle star.

USS Brennan (ex-HMS Bentinck) (DE-13)

USS Brennan (ex-HMS Bentinck) (DE-13)

USS Brennan was ordered as HMS Bentinck, BDE-13 at Mare Island Navy Yard, laid down on 28 February 1942 and launched on 22 August 1942, commissioned on 20 January 1943, for the USN.

USS Brennan was ordered as HMS Bentinck, BDE-13 at Mare Island Navy Yard, laid down on 28 February 1942 and launched on 22 August 1942, commissioned on 20 January 1943, for the USN.

Her namesake was John Joseph Brennan (14 June 1920 Philadelphia) LaSalle College, USN Reserve 6 July 1940, USS Wyoming, USS Illinois, USS Quincy, then Armed Guard Crew 34 New York, freighter Otho. ON 3 April 1942 he went down defending against U-754. USS Brennan after shakedown off southern California, sailed to Miami in March, as TS for student officers and DE crews, until the end of her career, with many port visits, Haiti, Jamaica, Cuba. On 2 May 1945 she collided with Gulfmaid in the Florida Strait, repaired in July. On 15 September 1945 she sailed to New York Navy Yard for inactivation. She was decommissioned on 9 October 1945, struck from the Navy List 24 October 1945; sold for scrap July 1946.