Category: ww2 spanish armada

Seaplane carrier Dédalo (1920)

Dédalo (1920) Spanish Armada (1920-1940) The world’s first “helicopter carrier” The title, which is abusive given the hybrid nature of…

Cervera class cruisers

Spain 1925-1950 – Principe Alfonso, Almirante Cervera, Miguel de Cervantes The interwar Spanish Cruisers Called different names by historians according…

WW2 Spanish Destroyers

Spanish Armada – 25 destroyers (1885-1947) Spanish destroyers: Pioneers From Audaz to Alvaro de Bazan: Argentine ARA Juan de Garay…

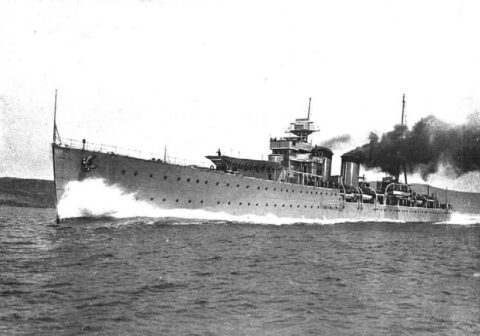

Blas de Lezo class cruisers (1922)

Spain – Méndez Núñez, Blas de Lezo. The ‘C-class’ Spanish cruisers: Blas de Lezo class Blas de Lezo in 1929…

WW2 Spanish Submarines

Spanish Armada – 17 submersibles (1865-1945) Iberian pioneers of Submersibles The submarine has many fathers. Among the pioneering nations, Spain…

Canarias class cruisers

Spanish Republic – Nationalists Canarias, Baleares (1936) The Spanish 8-in cruisers The two heavy cruisers Canarias and Baleares were the…

Cruiser Navarra (1920)

Spain Reina Victoria Eugenia aka Republica (1931) aka Navarra (1936) Too late for the Great war The Reina Victoria Eugenia…

España class Battleships (1912)

Spanish Armada Between the great war and civil war After the crushing defeats of 1898 in the hands of the…

dbodesign

dbodesign