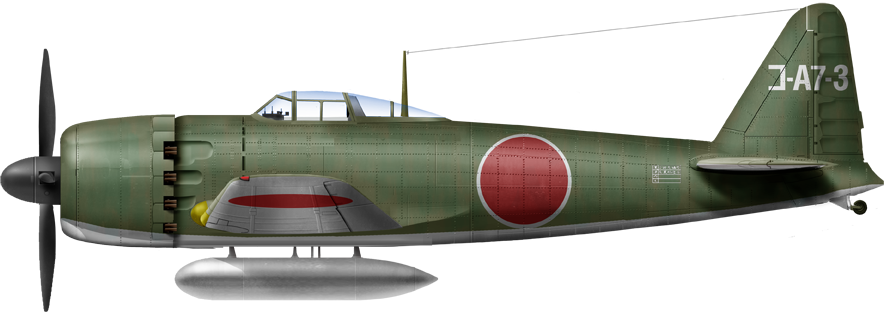

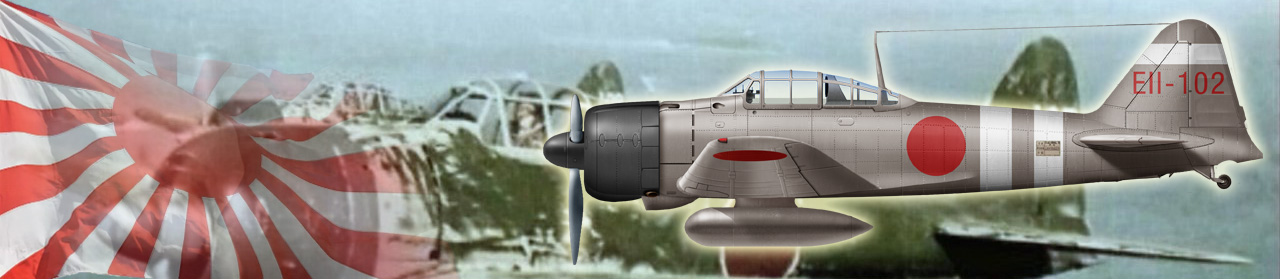

The legendary Japanese fighter

Just named colloquially “zero” and still popularly known as such today, the A6M, or “Mitsubishi Navy Type 0 carrier fighter” (零式艦上戦闘機) hence the number used as nickname, was the brainchild of superstar aviation designer Jiro Horikoshi. A superb dogfighter, combined with perhaps the best trained naval fighter pilots of the world’s at the time, achieved total air dominance in the Pacific until 1943.

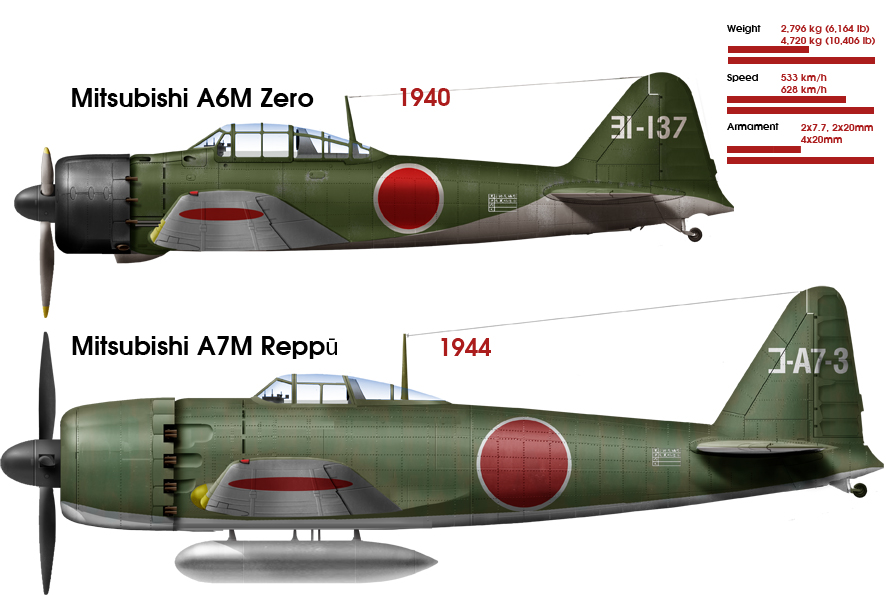

With 10,939 delivered by Mitsubishi, Nakajima and other plants, it was also the most ubiquitous of all WW2 Japanese models, soldiering over a very large area, between aircraft carriers and land bases, from Mandchuria to New Guinea, Malaysia to the Aleutians. The A6M gained an aura of invincibility in the first year of the war, brushing aside all opposition. This was the result of a number of factors, but its advantages became problems when the allies started to field better planes in 1944-45. It’s designated successor, the A7M Reppū never had the time to replaced it, but the A6M went through several iterations and variants to correct its known issues.

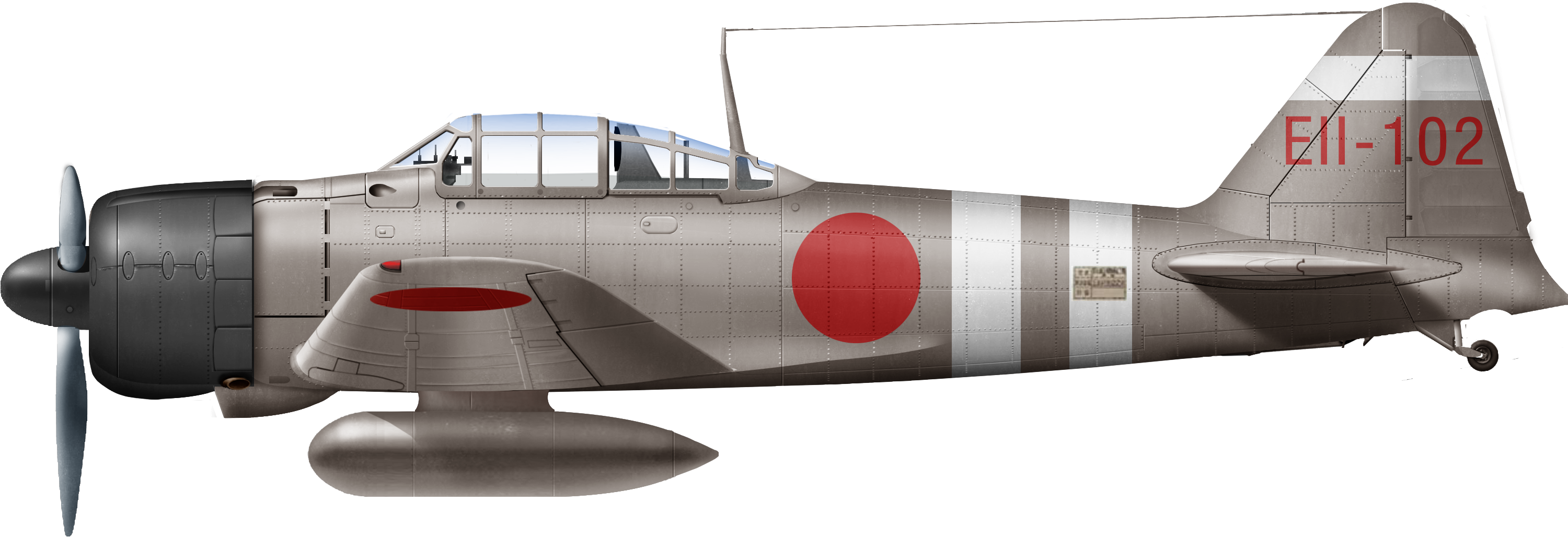

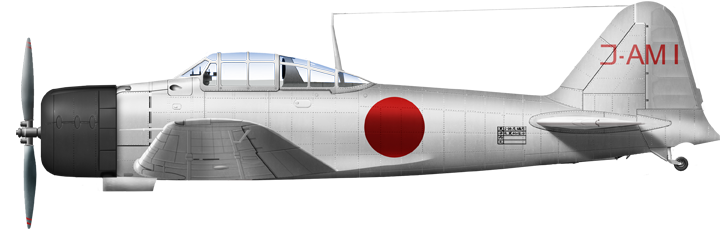

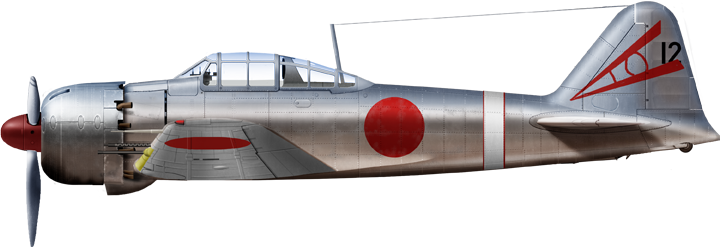

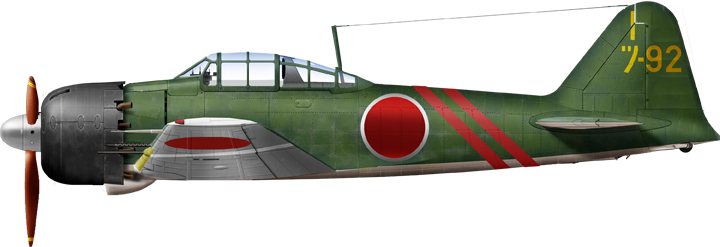

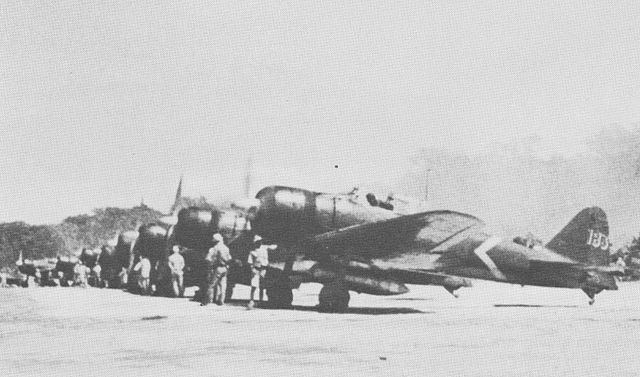

A6M2 in 1940

Design development

A successor to the A5M “Claude”

The A5M “Claude” was the Imperial Japanese navy main monoplane fighter in 1939, a 1st generation model, also designed by Horikoshi with elliptic wings and modern features, all metal fuselage but still antiquated ones, like fixed undecarriage and open cockpit. It was already a superb dogfigher, putting agility over all else. But in 1939, with a more serious opposition over China, pilots started to recoignise its limitations.

This process started early on: The Mitsubishi A5M fighter was just entering service in early 1937, when its replacement was already discussed. On 5 October 1937 was signed and published “Planning Requirements for the Prototype 12-shi Carrier-based Fighter” (or simply “12-shi spec”), sent to Nakajima and Mitsubishi to submit proposals. Both firms started preliminary design work, whereas requirements were still awaited. They were stn in the following months.

A5M4 onboard IJN Soryu in 1941

Genesis context

It happened that the the Japanese Navy was an early pioneers in carrier-borne fighter aircraft with Hosho preceding Argus by months, and fielded the Type 10 fighter, world’s first designed fighter for carrier operation while others were still adapted land-based models. The Type 3 fighter or A1N1 (a Nakajima copy of the Gloster Gambet) while in service, was followed by the 1931 Nakajima Type 90 (A2N) and 1935 Type 95 (A4N), faster but less agile.

So Mitsubishi was left out of the loop for about ten years before going back for the Type 96 A5N(A5N), first all-metal monoplane fighter, while Nakajima, which competed for the same, basically created a copy for the army, the Ki-27. Soon despite initial reserve, pilots found the apparent superiorority of the A5M in 1937 over all opposition. This new model gave Japanese designers, engineers and craftsmen a valuable experience, this time more and more decoupled from Western designs, with new techniques.

Among key points were how to minimize drag and obtain flush riveting, all sorts of weight saving measures without compromising rigidity, plus the ideal installation of radial engines into a new, high-speed, stressed skin all-metal airframe undergoing no short amount of streamlining at any level. The Type 96 (A5M) entered serviced just as a war in China broke and the Navy soon realized its limited range,n which became the main focus for the next replacement. The idea was to lead deeper penetrations for longer and more efficient escort missions into China as the war progressed. It was also realized that the Type 96 would soon be obsolete compared to upcoming Western Models; After all, both the spitfire and Me-109 emerged in 1935 already.

Other key points were the need for a retractable landing gear and heavier firepower, as the A5M two light machine guns were WW1 standard, rather puny compared to the opposition. Pilots complained about the time they needed to best their opponents in a dogfight. Examination of carrier versus land performance for a dedicated model also brought concerns in the Japanese Naval Command about theory and practice in their new and young tool, naval aviation.

To the traditional roles, reconnaissance, defence, spotting and harrassing until the big-guns battleships arrive to finish the job, was a position already dubious at the end of WWI World War 1 but still prevalent among Naval powers. So based on multiple naval games held by the academy and officers, the IJN soon realized that by having a fully independent arm from the army air force would help them reaching their goals more heavily. Without some legal cluttering or hampering capabilities and types, securing air superiority well beyond the reach of naval artillery thanks to a long range, became a main priority, not only for the attack aicraft of the nex generation, the B5N/D3A, but it’s escort, even reinforcing the idea of longer range could be useful for a fighter in open seas. Overall in 1937-38 these new doctrines, further pushed forward by Yamamoto and other promoters in the Navy versus traditionalists, made the Japanese Fleet Air Arm arguably the world’s best, years ahead of other nations. They clearly demonstrated this superiority in all engagements until 1943. Based on these experiences and discussions came the 1937 specifications 12-Shi:

Specification 12-shi (October 1937)

The design staff started with early combat reports of the A5M in China. From there, the IJN specified updated requirements, in October 1937. These were calling for:

- A speed of 270 kn (310 mph; 500 km/h) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft)

- A climb to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in 9.5 minutes.

- An endurance (With drop tanks) of two hours in normal regime

- 6-8 hours at economical cruising speed.

- A better armament with two 20 mm cannons and two 7.7 mm (.303 in) MG plus two 60 kg (130 lb) bombs.

- A complete, modern radio set

- A Radio direction finder for long-range navigation.

- Maneuverability at least equal to the A5M

- A wingspan below 12 m (39 ft) to fit in aircraft carriers hangars.

What’s amazing beyond the numbers, is that these figures were not only unheard carrier-borne fighter, demanding speed, rate of climb and armament, they were equal or superior to any land-based fighters, and cherry on the cake, were coupled with the world’s best range, several fold above all competition and usually proper to bomber, mixed with (which was contradictory) with exceptional agilty (how to reconcile the weight of extra avgas and lightness ?). Mitsubishi was apparently not afraid of the task, and entristed again Jiro Horikoshi to form a dream team of engineers, to study this seemingly impossible proposal. Nakajima which was the natural contender was quick in its reaction after reading these and said the Navy’s demands were impossible, pulling out of the competition right away.

Nakajima’s out, Mitsubishi takes up the gauntlet (April 1938)

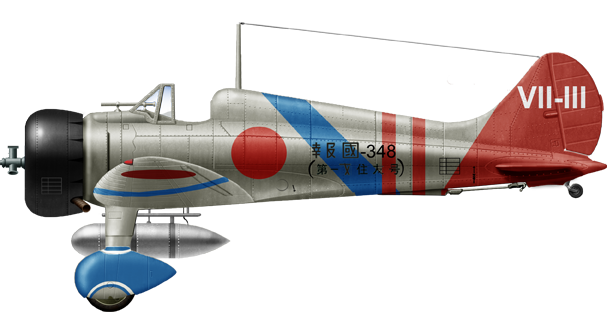

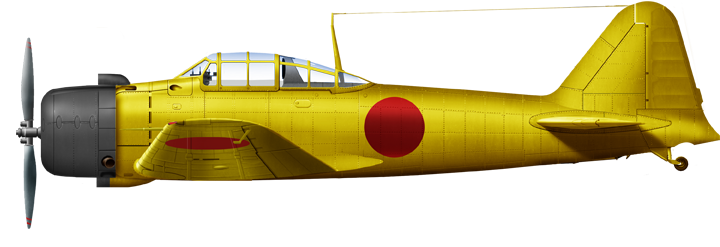

Ki-43 first prototype. It would fly first on January 1939. Note, i can’t find any photo for markings;

Nakajima’s team considered these new requirements impossible and pulled out outright in January 1938. However this must not fool us into thinking this was the official reason. Instead at the time, they looked towards a larger and more lucrative army contract, notably the awaited successor of the Ki-27 “Nate”, which would evolved into, here again, a model relatively similar to the “Zero”, the equally legendary Ki-43 Hayabusa (“Oscar”) (see later). And the agility of the latter even surpassed the A6M, but true, with a far lesser range and not the constraints of a carrier-based model. Both branches would have their respective champion.

Meanwhile, Mitsubishi’s chief designer Jiro Horikoshi, believed the requirements could be met. His take on the matter as that weight saving was to be the ultimate objective of the design. His team basically sat day and night, trying to eliminate every possible elements, replacing it by a lighter solution. Every weight-saving measure was incorporated into the design, requiring also a lot of “out-of-the box” thinking, notably by simplifying parts. Therefore, it at first the team (before having the complete specs) worked on a retractable undercarriage, enclosed cockpit version of the A5M with the latest engine, it was soon clear that very little of the former model could be reused, if at all.

Horikoshi at first simply retained and strengthened his former Type 96 design team with Yoshitoshi Sone and Teruo Tojo for the calculations, Brothers Sone and Yoshio Yoshikawa the structural work, Denichiro Inoue and Shotaro Tanaka the powerplant installation, Yoshimi Hatakenaka the armament plus equipment, Sadahiko Kato and Takeyoshi Mori the landing gear and its equipment. They selected the in-house Mitsubishi MK2 Zuisei 13, capable of delivering 875hp.

The pilot controversy (April-May 1938)

IJN Shokaku pilots in 1941

On April 10, 1938, a draft design of a new fighter sparked a lively discussion around technical decisions to made by designers, and terms of reference itself. Conservative pilots criticized the closed cockpit, arguing that it would severely restrict visibility while pilots managed to convince earlier Mitsubishi designers to also renounced it for the A5M2b modification, mostly to allow the pilots to look over the side of the cockpit forward, to find the correct glide path.

Composition of the armament and priority of flight qualities, which were maneuverability OR speed also fuelled the debate. On that matter, Lieutenant Commander (and Ace) Minoru Genda believed for a carrier-based fighter agility was key, over speed. For him, this way the fighter would be able to impose a battle on the enemy, winning a “turning contest”. He advocated achieving less power and if necessary, also heavy weaponry. Ace Lieutenant Commander Takeo Shibata led the opposing faction, stating that the A5M already demonstrated the Japanese already outperform other fighters.

Battles in China showed -and all pilots agreed on this- that the main problem, in order to engage opposition, was first to get there. Due to its short flight range, the A5M could just not escort bombers up to the objectives. So Shibata wanted both high straight speed and range to be paramount in the new design. Speed for hims was also a factor to impose its own battle tactics on slower opponents. Shibata also argued well-trained pilots with a faster aircraft would have a double edge in combat, even with marginally lower maneuverability.

This controversy between the two aces was not resolved at a meeting held on April 13, 1938. Circles close to the the Imperial Navy High Command started to voice their frustration over the pilot’s internal war and many started to advocate for a freeze of the 12-Ci program, rewrited them as well.

Jiro Horikoshi however intervened, and promised to ease all oppositions with his design. Based on early calculations, he was able to convince the Navy and the pilots alike that his new high-performance would have at the same time, the desired speed, range and maneuverability to please all pilots. Kaigun Koku Hombu (IJN aviation procurement bureau) officially approved the basic layout of the new model. But even construction of prototypes was greenlighted, Mitsubishi’s design team already had the design well refined in Oyomachi, Nagoya.

Impossible Challenges

Demands were so radical, though, it obliged to almost start from scratch. The company also took into consideration innovationd in several fields to achieve its goals, notably the use of a new top-secret aluminium alloy, developed by Sumitomo Metal Industries in 1936. This “extra super duralumin” (ESD) was indeed lighter, yet stronger, and more ductile than other alloys used at the time. The only problem -a serious one for using it at sea- was corrosive attack which made it brittle.

The problem was soon solved by consulting chemical companies and securing an equally innovative anti-corrosion coating, to be applied after fabrication. Among other measures, it was soon obvious that no armour protection was affordable given the limitations, for the pilot. Any special protection for critical points of the aircraft or the engine were ommitted as well as self-sealing fuel tanks. These measures, radical, helped reaching the specifications, but their cost was not apparent at first. It was paid dearly in 1943, five years later.

The Mitsubishi Type 0 given the year, was however lighter and more maneuverable than any fighter that came before, added to the longest range for any fighter plane (single-engine) at the time, in WW2. Tactically it was an enormous advantage for the Navy, that could escort their strike aircraft all the way to their objective, stay in defense, assist destroying opposition, and escort them back safely. No other country at the time has such fighter. The Zero was also capable of searching out possible targets hundreds of kilometres away, patrol much longer, etc. The tradeoff in weight and weak construction was known. It was discovered later it was quick to catch fire and exploding after a few rounds.

The reasoning was however, that speed and agility was the best defense. Given the cultivated aggressiveness of Japanese pilots, the new fighter was fitting them like a glove. The A6M in the end, secuced the navy as being the 2nd generation fighter it needed, by combining in addition of this agility, heavy armament and long range, a low-wing cantilever monoplane layout, a etractable, wide-set conventional landing gear, and an enclosed, well designed cockpit.

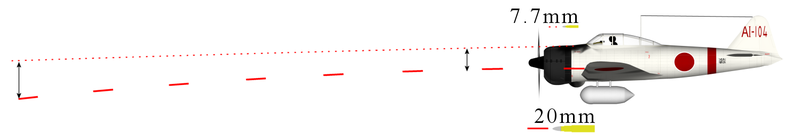

Outside advanced techniques with this extra-super duralumin, work was greatly facilitated by getting rid of pilot armour and self-sealing fuel tanks, thanks to the attack mentality of pilots of the time. Armament however as asked for was to be seriously upgraded. This ended by the choice of a pair of licence-built Oerlikon 20mm cannon (as the Type 99) located in the wings, which needed serious strenghtening at this place, exclusing also the fitting of satisfying arrangement of folding wings. The fuselage retained two Type 97 7.7mm machine guns in the hood.

Design Development

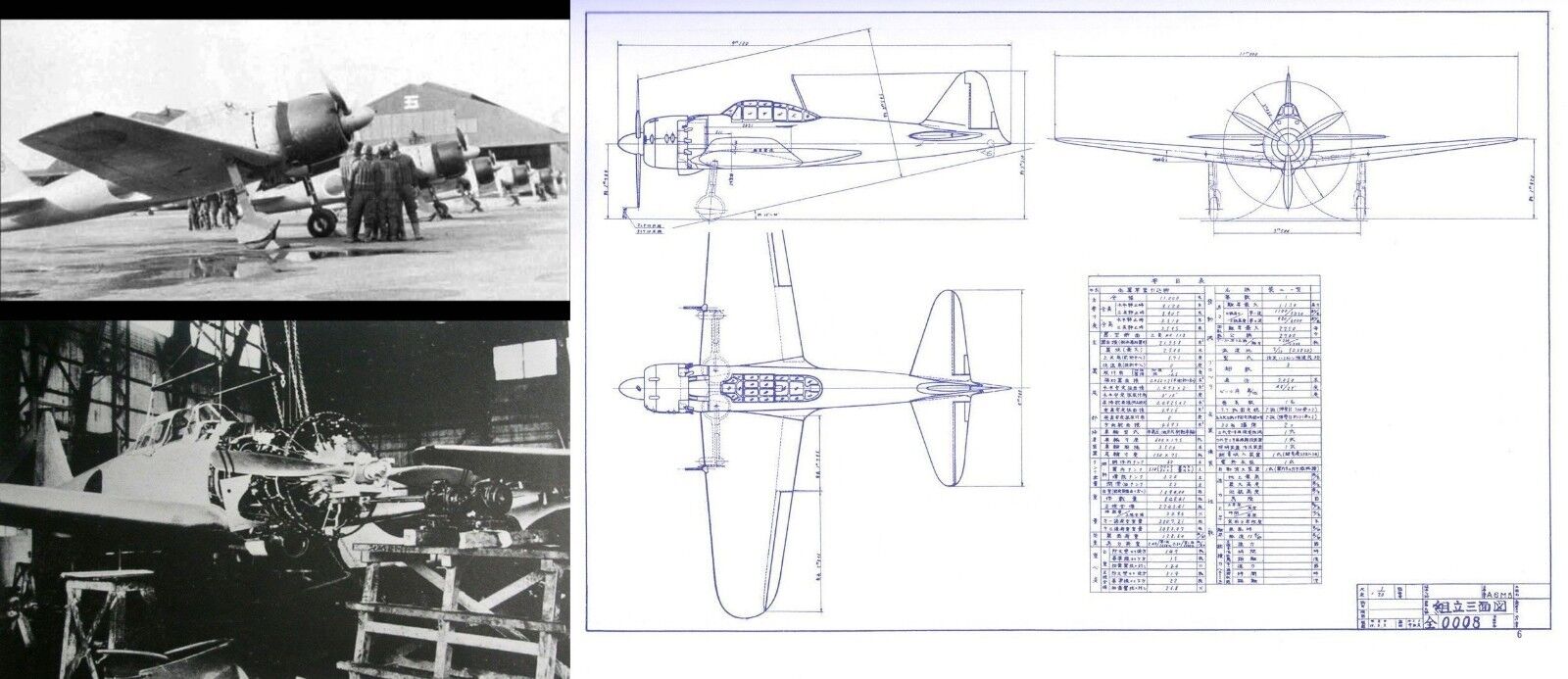

The young and very talented design team behind the Mitsubishi A6M1 Type Zero. A smiling Dr. Jiro Horikoshi is at the center. His assistant, Yoshitoshi Sone, is at the left. (Mitsubishi Kokuki K.K.)

Construction of the first prototype started circa in November 1938, completed in March 1939. This very first Type 0 weighed… 43,801b which was ludicrously light even compared to the gracious Spitfire prototype (53,32lb). So despite a modest output and helped by a sober consumption, the model maintained both long range and good performance and agility in all corners. That however meant future, heavier powerful engines could not be fitted without extensive redesign. So the offensive first, agility first doctrine eventually contained the seeds of its own downfall and never having a true successor.

Nakajima understood quickly these limitations and after trying to upgrade the Ki-43 by creating an interceptor derivative, the Ki-44, soon started again from a blank page with the Ki-84 whereas Mitsubishi condemned the Navy to stick with the A6M until the end of the war. The A7P (see later) indeed would never be ready in time. The Navy was nevertheless quite impressed with the prototype, which started unofficial tests at Mitsubishi’s Nagoya factory on 16th March 1939. Various systems were started and closed, flight commands, starter, ect.

Full engine tests started on the 18th, before being towed by ox-cart to Kagamigahara airfield for full air tests. Test pilot Katsuzo Shima had the privilege of “deflouring” the A6M, lifting off at 5.30 pm, 1st April 1939 for the maiden flight. Problems were detected with the braking system. Excessive vibration too in flight, which were common for new models. After extra bracing and solving minor issues, the Navy staff was invited for official tests of the model now called the “A6M1”, using an identical prototype.

On April 25, 1939 the first flight showed a limited top speed due to unsufficient output, compared to new fighters created in Germany, Great Britain or the USA now gearing up for 1000 hp+ gines. On May 1, Kaigun Koku Hombu instructed the powerplant team to install on the first prototype, now inactivated for further factory tests, the Nakajima Sakae 12 rated for 940 hp. While being refitted on October 18, the second prototype was tested with a three-blade propeller, seemingly superior and full armament set. These were factory tests though, performed whereas on October 25, the model was was accepted by the fleet. Weapons testing started later in October, with excellent results as for acuracy, nine hits sercured out of 20 shells, in flight on a 19 m2 ground target.

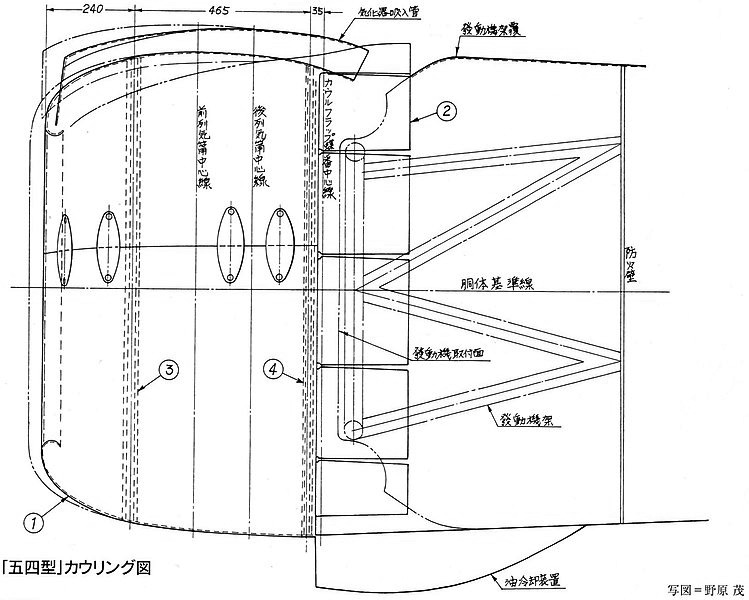

The third prototype was in fact the very first pre-series A6M2 fitted with the Sakae 12 engine. To install it, the engine mount and hood were reworked to accomodate the larger Sakae and for minimizing and keep forward visibility, designers made the hood a very tight fit, a veritable glove around the engine. The first consequence was unsufficien engine cooling, an issue the designers took considerable effort to solve. The team also worked to eliminate a noted tendency by test pilots to a flat spin and so the tail was redesigned, with its cord moved back, the horizontal tail shifted up resulting in this elongated “tail” and almost triangular shape, and increased length. The original configuration can be seen on the production A6M2-N “Rufe”.

This third prototype was vital to secure mass production, at Nagoya aircraft factory No.3. The Navy the lack of outright speed at 304 mph instead of 315 mph as asked for, had all the remaining requirements met and teething issues worked on actively, so it was officially accepted on the 14th September 1939. And it was time: War raged in Europe since the 1st. This order came even before the completion of the full test cycle, and it gained its Full military designation, to be communicated to all branches of the administration, as “A6M1 Type 0 Carrier-borne Fighter”.

Name and designation

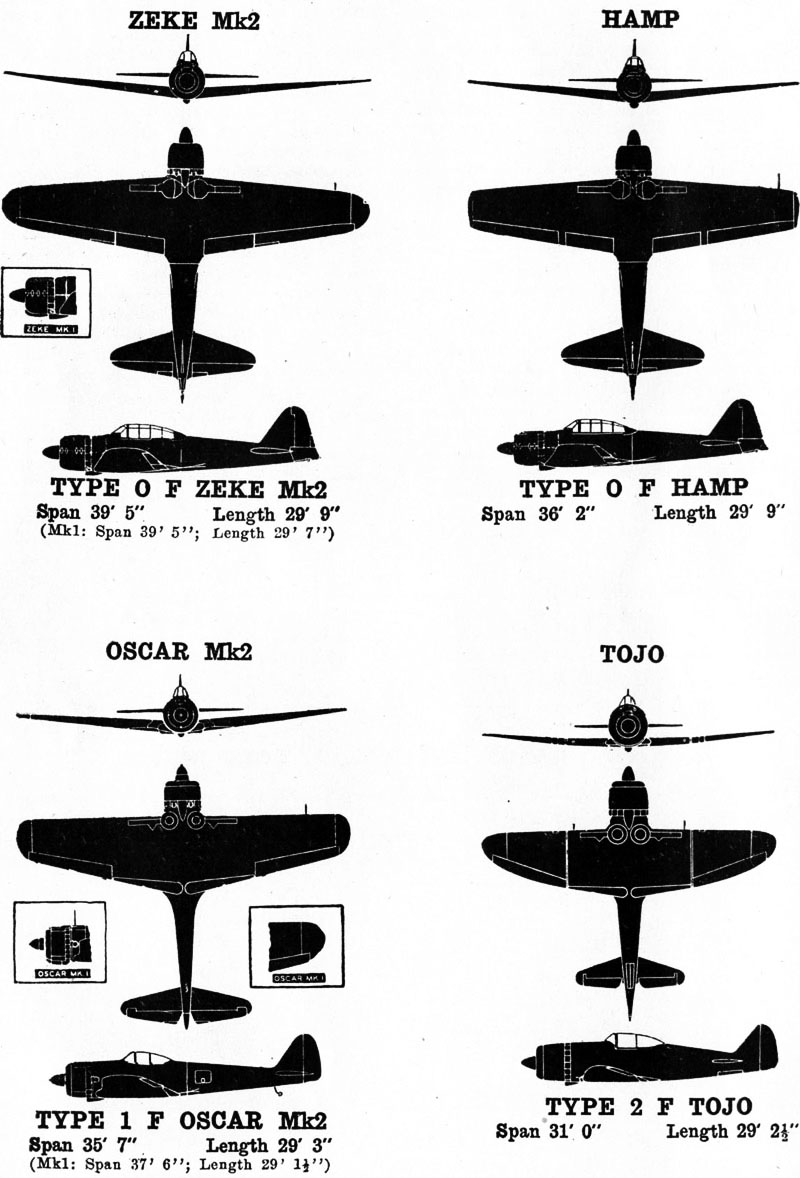

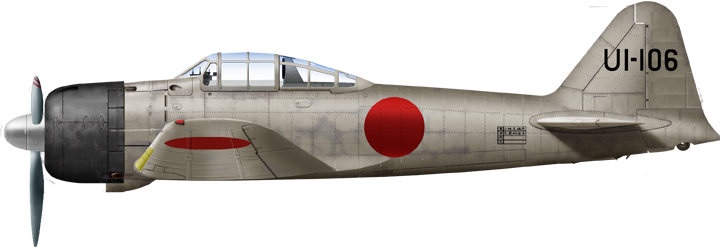

ONI comparison between the “Zeke” and “Hamp”, believed to be a completely new aircraft.

And this brought us to the famous name of the model. Unlike later WW2 models which for propaganda reasons received nicknames instead of the cold navy designation (the army did the same), the usual practice for pilots and personal was to call it the “Rei-sen” an abbreviation of the full designation. It was by no means official or had any meaning. Also, A6M referred to A for the type (fighter), 6 as the sixth fighter model designed by Mitsubishi, and of course “M” standing for Mitsubishi.

The ‘0’ however, derived from the last digit by virtue of the unique Japanese calendar in reality came from the year 2600 (1940) and the “Rei Shiki Sento Ki” shortened to Rei-Sen or Reisen could mean “zero” by simplification. It became popular, but was not official in US Intel either. In 1941, the Allies applying code-names to all models had the A6M2 designator chosen being ‘Zeke’ last letter in the alphabet in reference to the “model 0”, “Zek” being a contraction from the biblical name “Ezekiel” although “zero” while not official became far more popular.

The cut-wings version A6M3-72 was designated ‘Hamp’ and the A6M3-22 ‘Zeke Mark 2’, the A6M2-N ‘Rufe’ (see later). ‘Zero’ in western sources mostly became first popular by US use, as British personnel in Singapore/Malaya called them first as ‘Navy Noughts’. The model became so feared (a bit like the Tiger tank of the Wehrmacht), that the handy nickname of “Zero” became a reference for all Japanese fighters in the general public and the press, obscuring many other models, including those of the army. It has been maintained the same way over many years in popular culture, as basically the only known model by the general public. Even among pilots, especially in 1942, “Zeros” were seen everywhere despite they encountered the “Oscar” or its successors. Despite it’s many design changes, the A6M5 also kept the famous name.

Initial Reception

ONI, the “Hamp”, A6M2

ONI, the “Zeke”, A6M3

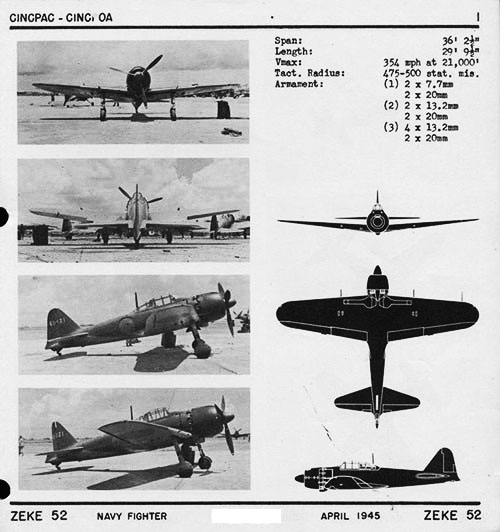

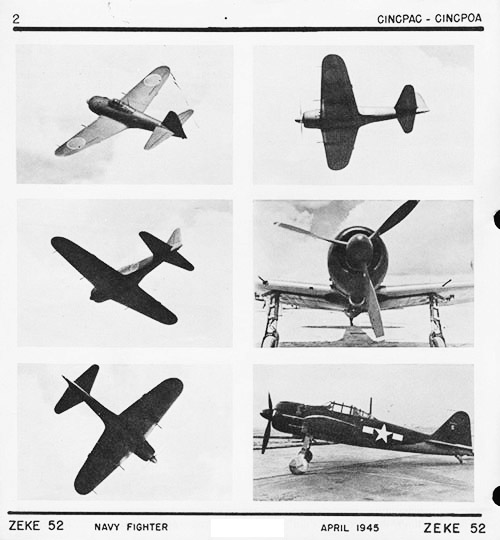

ONI depictions of the “Zeke 52” (A6M5)

The pre-production batch was received for military testing at Yokosuka kokutai, stationed at the Oppama airfield. This instructor/test unit was the most famous in Japan, staffed by the most experienced pilots of the IJN. They were all fully able to appreciate the model, and in their initial reports, spoke highly of its flight characteristics, rivalling in superlatives terms. The A6M1 was trouble-free in addition, which added to the immense trust they had for it, apart a serious incident on March 11, 1940 when test pilot Okuyama flying the second prototype tested overloading the engine with revolutions in a steep dive.

The second approach from 1,500 m to 900 m at 50° angle generated such vibrations and noise the suddenly exploded, leading the prototype to burst into pieces, with the pilot thrown out of the cockpit at 300 m. His parachute opened, but the schock was such the pilot was pulled out of the belts and fell into the water at great speed, killed instantly. Exact cause could not be determined although some expressed that perhaps the aileron balancers broke resulting in the initial vibration that destroyed the aircraft. This, the initial order delivery schedule was pushed from May to July 1940, leaving time to strengthen the attachment points of these balancers, as well as the rudders.

Final tuning as production took place added pressure from the high command and military personal, as its amazing flight qualities spread like live fire from Oppama among aviators. Some went off working hours to see and test it of possible, while Mitsubishi was trying to manage the best flight range as requested probably the most stringent and demanding specification. Extra rosy reviews came also from Yokosuka kokutai test pilots despite Mitsubishi’s insitence that their “product” was still unfinished.

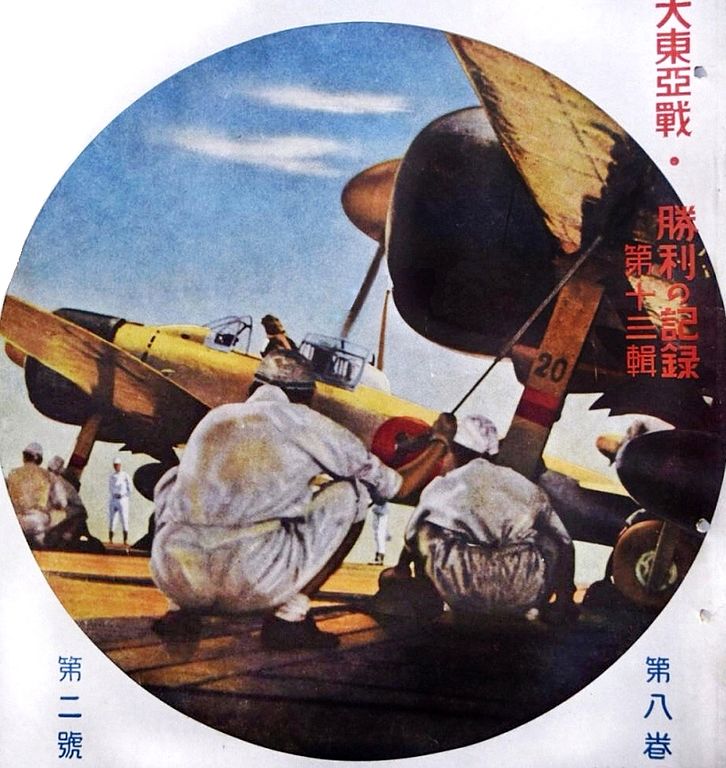

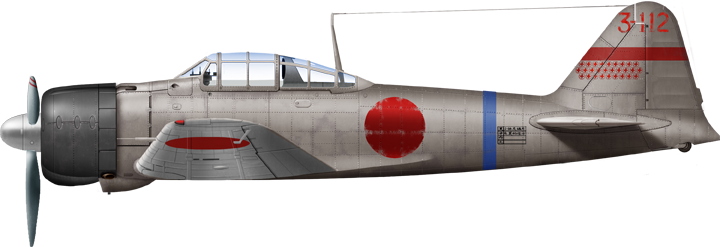

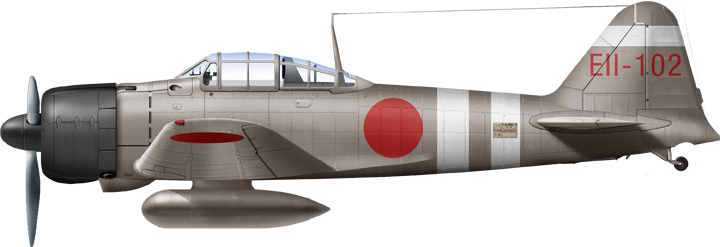

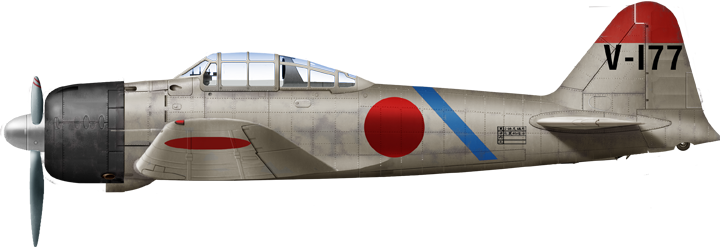

On July 21, 1940, Kaigun Koku Hombu announced the reception of the first batch of six pre-production fighters, which flew to Hankou in China, staffed with pilots from Yokosuka Kokutai led by Tamotsu Yokoyama. The small contingent was integrated into the 12th Rengo Kokutai. Back in Japan, the next batch of pre-production aircraft were sent straight to IJN Kaga for carrier qualification. After successful completion, the A6M2 model 11 was accepted into service, gaining the “Reisen” moniker. These nine carried fighters also departed for Hankow, reinforcing the 12th Rengo Kokutai (which had a first loss due to AA at the time).

Problem with engine cooling were solved by using tin deflectors installed on the cylinders of the first row meanwhile. Their effect was to directing air jets to the cylinders of the second row. This became the standard for all variants, whatever the engine, but another issue was revealed in front-line conditions which was the frequent jamming of the ventral fuel tank discharge system. This unwanted “ballast” created drag under the fuselage, reuniting the aerodynamics qualities of the aircraft to some extent.

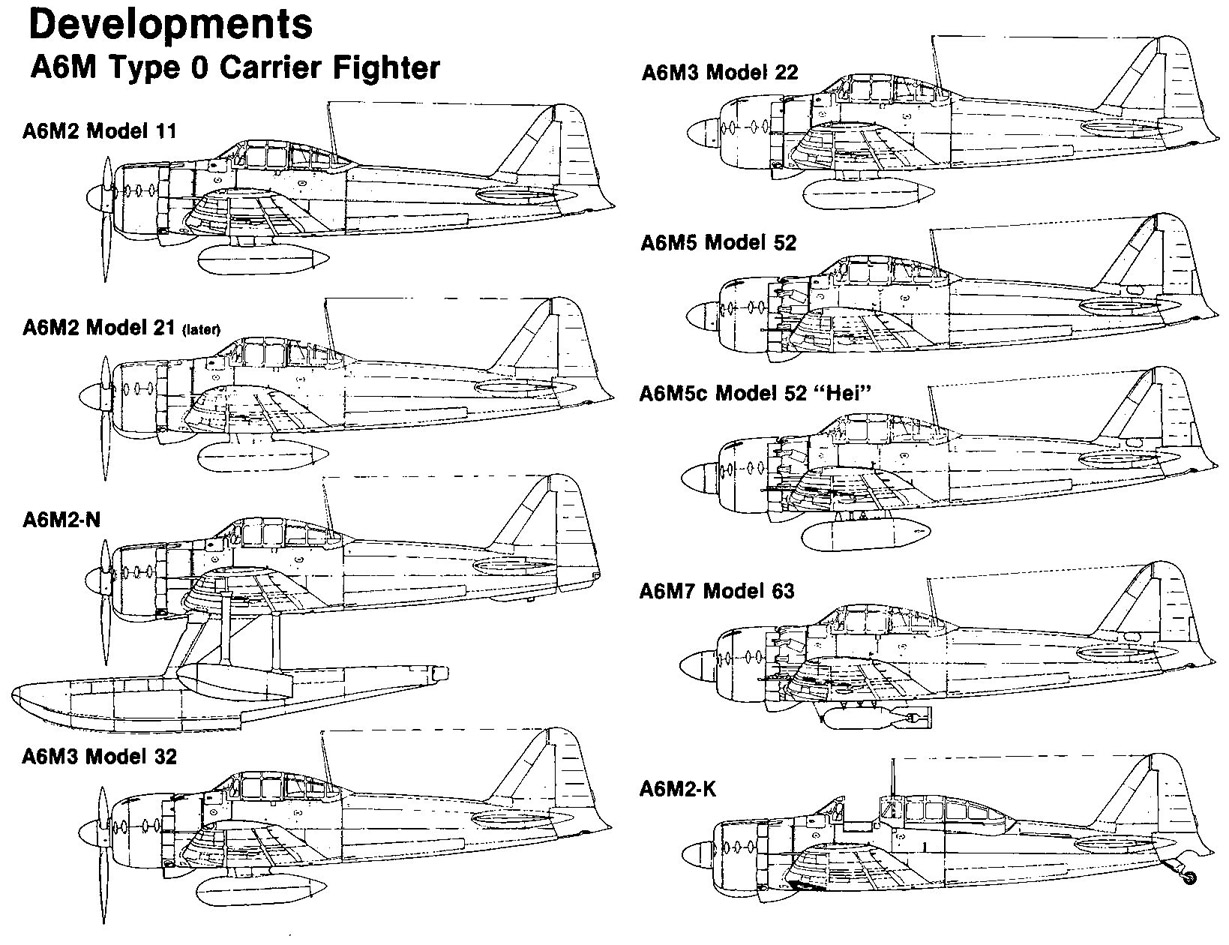

Design evolution

Variants

Mitsubishi being asked, despite the acceptance and first order, to solve the lack of speed, concentrated on the next iteration in 1940, the A6M2. Same model but with a the more powerful 940hp Nakajima Sakae 12 engine. The A6M2 was mostly modified with extra bracing for the larger, heavier engine, and the first 15 pre-production models were sent to Hankow, China for operational trials, starting on 21 July 1940. First combat missions started, showing a clear cut superiority over any model of Chinese fighters. Only two Zeros were lost in these early operations and it was by AA fire, traded for many, many kills, fighters and bombers alike. They ruled the skies over China, at least in dedicated coastal areas. More inland, the Ki-43 made it’s combat debut also, leading to interesting comparisons.

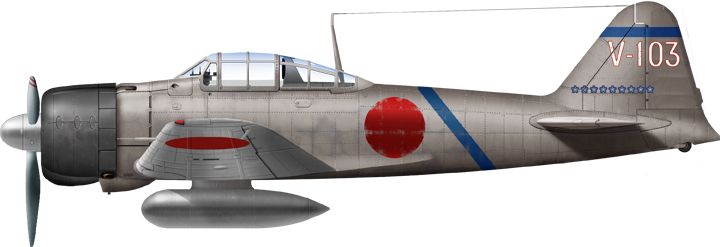

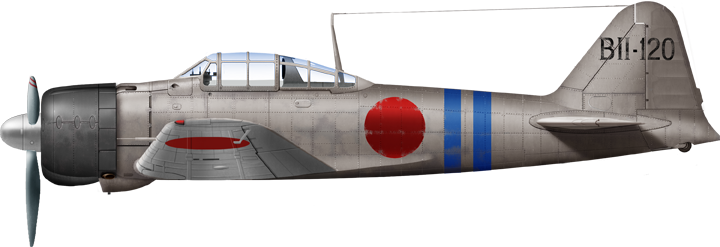

Mitsubishi built 47 more A6M2 Model 11 by November 1940 and started working on the Model 21, to answer a regular critique. The wing structure intil that point did not supported the complicated gear for wings folding. A first measure found was folding wingtips. The passage from “11” to “21” denoted this airframe change, the other digit, the engine change. The A6M2 Model 21 thus became standard at the time of Pearl Harbour, 18 mo,nths after its combat debut. There were 328 of these in JNAF units, the bulk of some 521 naval fighters aboard carriers of the Kido Butai (1st fleet air arm). The A5M was now relegated to light carriers, land-based units and theaters, notably in China.

1941 saw an effort by the design team to try overcoming the A6M initial design limitations, to keep its superiority over Allied fighters. This led to the design of the first real all-out improvement, the A6M3 Model 32 which was redesigned around the 1,130 hp Sakae 21 engine. For simplification the folding wingtip section was removed for a simplified clipped wing. The centre of gravity was also moved back towards the bulkhead and this reduced in turn the fuel tank volume.

Later came the Model 22 which saw the return to the folding-tip wing and fitting an extra 12 gallon fuel tank in each wing to reclaimed the lost range (it was still superior to any allied fighter). Meanwhile, engineers worked on an even greater improvements, the Model 52. The Model 22 had a fairly short operational life and production with just 560 delivered between 1942 and 1943, including those by Nakajima.

For most naval air historians the A6M5 Model 52 was really the “game changer”, less compared to the Model 32 it replaced, but compared to the A6M1 as a whole. Helped by some weight saving in the wing, heavier gauge wing skins were possible to make for higher dive speed (a point which was lacking previously, the F4F could escaped that way, being way more rigid), and the engine had a new cowling caracterized by individual exhaust stacks for additional thrust. This became in 1943 the standard, most numerous and used version overall.

The Model 52 became outdated however by 1944 as already by mid-1943 it did not fared well compared to the beast that was the F6F, so further modifications were pressed on, all severely hampered by the limitations of the initial design. Meanwhile, Mitsubishin came with the A7M Reppu and J2M Raiden, the latter entering service unlike the first in small quantitied, and Kawanishi with the excellent and N1K Shiden, but these complicated design failed to obtain masse production and Mitsubishin’s factories were stuck with a 1940 model that cannot be upgraded any longer.

To try improve altitude combat capabilities and enabling some interception capabilities at a time the Empire was on the defenseive, Jiro’s team managed to pull out the ramarkable A6M4, first with a turbo-supercharged engine and the A6M6 using water-methanol injection. The Navy also wanted a more serious fighter bomber from it’s standard model leading to the development of the A6M7 and eventually to the A6M8 fitted to endure the massive 1,350 hp Kinsei engine, almost twice the power of the original Suisei 13 and its 875 hp. Their development was complicated by shortages of all sorts plus bombings, and in small quantities.

Design Features

-The Zero also revolutionized the way naval fighter could operate, by bringing an amazing radius of action, twice the previous figures in the IJN: 1,180 miles. Ex. The FAA Sea Hurricane was limited for example to 600 miles, the sea spitfire just 550, and the F4F 845 miles.

-The zero blended the limit between carrier-borne fighters and land based equivalents. When the zero was in service, the F4F was 4 months late in its introduction. For the first time a naval fighter, usually inferior to its land counterparts, could dominate the skies and dogfight with any model in the air at that time. This gave the fighter a “long arm”, ability to escort the attack planes to target, engaged the CAP in a long dogfight further straining gazoline, and came back escorting all the way. It could strile by keeping the carriers out of arm’s way. This range completely deceived US commander in 1942. ONI figures were totally underestimated at around 800 miles and surprise total in operations. Having a 500 miles radius of action around a carrier was unheard of, and decisive. Their appearance seemibly in many places at once made the US think the Japanese had far more zeros than in reality.

-Thus, it was clear the US intel needed to have their hands on a zero at all costs. It became as much top priority as for the British cracking for example the Enigma code. However in almost all cases, down Zeros were so light they disintegrated, leaving practicall nothing to study but scattered small remains on miles on end. The first occasion it nearly happened was over Parl Harbor in Dec. 1941, as two of these were shot down, but the first landed on its belly, but slided and crashed into N.4 hangar at Kamehameha. At least the rear section survived well enough to be studied. Another crash-landed on its way back to the Kido Butai, also making a controlled belly-landing on Nihao Island. The pilot, Shigenori Nishikaichi was captured by local Hawaiians, but managed to escape, returned to his planes and burned it entirely, before being caught and killed. The first would be captured in Alaska. This was a crucial blow as the Japanese lost their secrecy and pilots were duly briefed on the strenghts and weaknesses of the nible champion.

-August 1940: Start of service. Sept. 13 first victory over China 30 Chinese fighters I-15/I-16. 30 min. dogfight over chongking. Saburo Sindu claimed 20+ Chinese down without any loss, but four zeros damaged.

-The “zero” had a indirect major shortcoming: Its production. Interservice rivalry first objected to adopt the A6M despite it’s qualities, and even for the Navy itself, Japan lacked the engineers, the economic muscle, and the industrial culture needed to rapidlt ramp up to wartime production the way the US did. By late 1943 still, the Zero, was still hand made by skilled laborers. The models were only made in Nagoya and parts conveyed by mostly primitive means: Oxen were carrying these between facilities ! Due to the absence of airfield or railway nearby, not good roads and the fear to damage tghe delicate fighter on trucks, so they were carried the old way for 34 miles being final assembly.

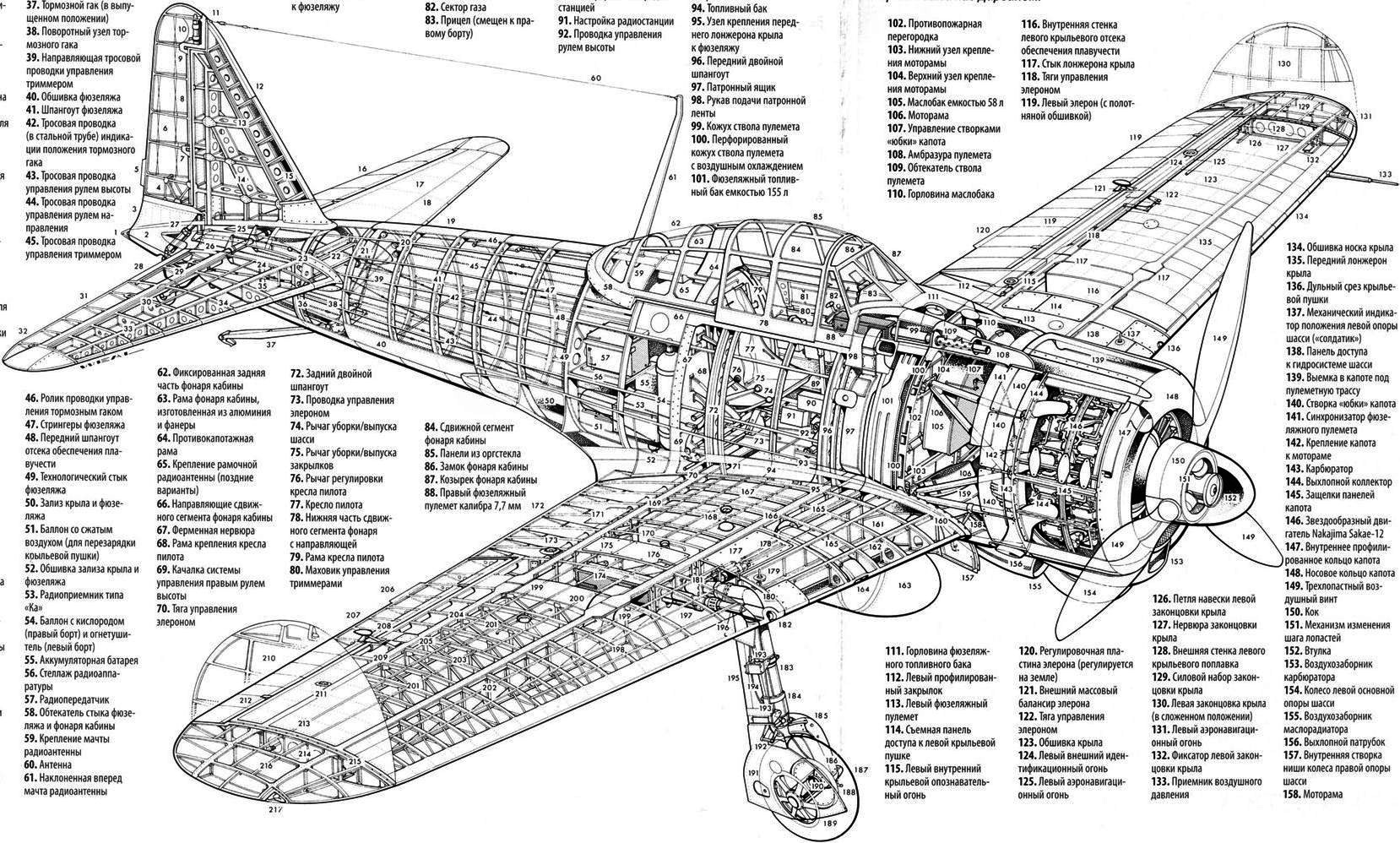

General structure

(To come if i can find infos)

Engine

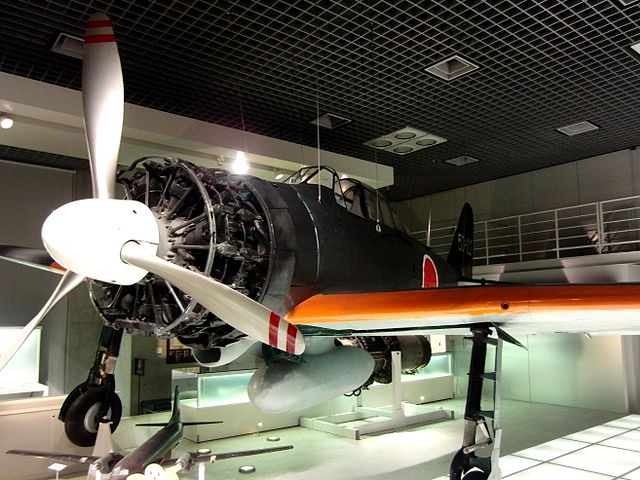

A6M5 Sakae engine without cover. A distant licenced mix of Hawker Siddeley, Bristol Jupiter and Wright Cyclone designs studied and improved over the years.

The A6M1 engine was not the one initially planned for production, but a quick in-house production model to speed up testing. It was the Mitsubishi MK2C Zuisen 13: A 2-row, 14 cyl. radial air-cooled, supercharged engine with a cubic capacity of 28.017 liter (1,709.7 cubic inch displacement) and rated for 780 horsepower. It was half the final evolution of the Type 0 A6M7.

The first standard engine of the production A6M2 Model 12 was the air-cooled, supercharged, 27.874 liter (1,700.962 cubic inch) Nakajima Hikoki K.K. NK1C Sakae 12. This was a two-row, fourteen-cylinder radial rated at 925 horsepower coupled with a three-bladed Sumitomo constant-speed propeller through a 1.71:1 gear reduction. The Navy found it lacked power and wanted to swap to the next model in development.

Various hood and cowling designs between types

This gave the A6M2 Model 22, powered by the Nakajima NK1F Sakae 21 (hence the model name) 14-cylinder radial rated for 1130 hp and equipped with a two-speed supercharger. A single A6M3 was tested with a Sakae 12 to but posed weight distribution and center of gravity issues. Differences between the Sakae 12 and 21 were the bulbous reduction gear housing around the front of the crankshaft (absent from the Sakae 12). The Sakae 21 had the Naval designation NK1F, first letter standing for the manufacturer, Nakajima, K for “air cooled”, 1 for the sequence number within given class of engines and F for the version of the engine. The Sakae 12 was also called NK1C.

Specs were as follows: Cruise speed 207 mph (333 kilometers per hour), max 277 mph (446 kilometers per hour, Sea Level) or 335 mph (539 kilometers per hour) at 16,000 feet (4,877 meters) with a ceiling at 37,000 feet (11,278 meters), maximum range to 1,175 miles (1,891 kilometers). This was less than the A6M1 and go go downards until measures were taken to reclaim the lost fuel.

Cowling of the experimental A6M8

The standard A6M3 was given the Sakae 21, with a new 2-stage mechanical supercharger, improved gearbox, upflow carburetor rated at 1130 hp on the Model 21. This was the “chopped-wings, low range” Zero of the whole serie. The A6M3 M22 regained some range. The A6M4 was a rare, mostly experimental variation with a turbocharger which never worked properly mostly due to materials issues. The A6M5 kept the same engine with minor improvements, and the A6M6 tested the Sakae 31a engine with water-methanol injection, never passing out the prototype phase, but pushing the figure to 1,210 hp (902 kW).

The A6M7 had the 1,130 hp Sakae-31 engine. By 1944 when it was tested, this was 1,000+ hp shy of most allied fighters. This engine remained the most powerful on offer before Mitsubish came out, two years late, with the Kinsei 62 engine, capable of 1,163 kW (1,560 hp). It was adopted by the prototypes A6M8 but never saw action. Thus, the Zero made all its WW2 career with 1,000 hp like some Italian fighters. It was not a problem as long as the superstructure remained light, but demands for protection and better armament rose weight considerably and performances stayed on the same range all along, with decreasing range to boot.

Armament

The Production A6M1 was given a couple of Dai Nihon Heiki K.K. Two Type 97 7.7 mm (.303-caliber) light machine guns were mounted in the hood, firing in slight channels, and synchronized with the propeller arc. These were licenced Vickers Type E .303 machine gun, so they were liquid-cooled. 600 rounds in sore for either, with tracers. This was coupled with two Type 99 20 mm autocannons mounted in the wing, but with just 60 shells per gun. Both were licensed Oerlikon FF guns. No rack was installed to carry bombs unlike what was planned (aktghough fittings were there), but a belly extra fuel tank as the range was already insane for the time.

Specifications for the 1937 12-Shi fighter called two 20mm cannon, two 7.7mm LMG, racks for two 60kg bombs, and with A6M3 Model 32 no modifications were made but in the channels which the LMGs fired through as the engine hood grew in size. Ammunition supply for wings cannon was a main criticism, and it was increased from 60 to 100 rounds per gun. Same for the Model 22. The Model 22KO or A6M3 Model 22a had longer-barrel cannons. Some Model 22s experimentally tested a 30mm cannons, in combat at Rabaul. But vibrations were just to much for the wings.

The 7.7mm machine guns had a capacity raised to 680 rounds each and close to the Army Type 89 MG with belt ammunition for a 1000rpm rate of fire and effective range of 600m. They had a muzzle velocity of 2460ft/sec and weight 26lb each. Replacement on the field and service was easy. Not so much for the 20 mm wing guns.

Divergence path between the 7.7 and 20 mm.

The wing Type 99 cannons of the Model 22 used drum-magazine types (100 rounds) belt-fed later to reach 150 rounds. The Model 22a or Model 2 Shiki 3 with a longer barrel reached 490rpm at 2,000ft/second, and useful range of l000m. The 30mm Type 5 tested by just three A6M3 Model 22 were limited to a 45-round magazine, with a muzzle velocity of 2460ft/sec, but as said before was not adopted.

The pilot could aim via a Type 98 reflector gunsight mounted in front of his position, the tube going through the front glass, but for post-action briefings an optional Type 89 camera-gun could be fitted to the port wing root. The Type 89 Motion Picture Gun 2nd remodeled No/3899 from Roku Sakura.

Armament was augmented on the A6M5a, with belt-fed Type 99-2 (long barrel) 4-shiki, to 125 rounds per gun. The next A6M5b replaced the right LMG by a single 13.2 mm Type 3 gun with a 790 m/s (2,600 ft/s) muzzle velocity and, 900 m (3,000 ft) range, 800 rpm, 240 rounds in store. That was an appreciable increase of firepower, but asymetric. The A6M5c was even more powerful and engineers managed to shoe in two extra 13.2 mm (.51 in) Type 3 machine guns (same model as on the hood) in the wings, outer portion from the cannons. Although ammo was limited they had on paper more firepower than their adversaries given the fact 20 mm superior to 0.5 in HMGs. However the left hood 7.7 mm gun was deleted, making room for extra ammunition for the right Type 3 HMG. In addition the underwing was reinforced to accept four racks carrying each a small 60 kgs incendiary bomb or rockets. The “special type” bakusen was a modified fighter bomber substituting to the drop tank rack, a bomb rack to lift a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb.

Eventually the little-known A6M8 fitted with the most powerful engine of the serie, had a brand new cowling now with a pair of 13.2mm Type 3 HMGs and those in the wings replaced by two more of 20 mm for four total, each with a 125 rounds belt. Unfortunately, Only two prototypes were built, this model never saw combat. This was a sharp contrast to its Army rival Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa which at its beginning only carried two 7.7 mm LMGs.

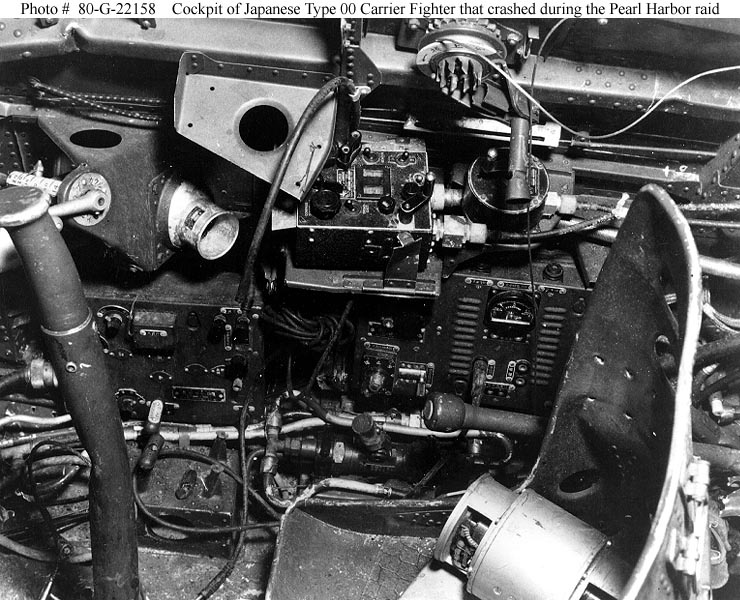

Cockpit, Equipments & Avionics

On the A6M2

The Zero cockpit was clear and simple to read, with the lightest materials possible, and common dials for several metrics to save space and weight. It also made for a less complicated electric wiring, less chances of a shortcut and fire. The two most important dials for the pitch and yaw and speed indicator were placed right between the central console, either side of the 7.7 mm machine guns, which took some internal space but could be serviced by the pilot. The rest of instruments, 13 different dials mostly related to the engine’s rpm and oil, avgas indicators among others, was located below. Extra gauges and dials were located on the right side, along with control levers. See also a 360° view.

On the A6M5

Normal provision was a full radio fit with a direction finding equipment. The radio direction indicator was located at the lower left of the instrument panel with a console on the right side of the cockpit, close to the inertia panel of Zerostarting handle. The proper radio control unit was located on a console rear of it. The loop antenna was installed behind the pilot’s head, under the glass cover, and can be manipulated through a control handle a the rear of the radio control unit. The wooden mast (because lighter) rear of the cockpit supported the radio aerial connected to the fin top. To serve the radio a transformer and battery were located inside the fuselage, behind the pilot’s seat. The Model 11 standard model was the Type 96-Ku-1 radio, complemented by the Type 1 Ku-3 direction finder. The Model 22 was likely equipped the same way.

Final assessment

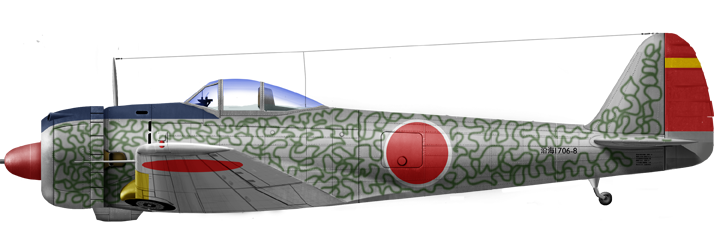

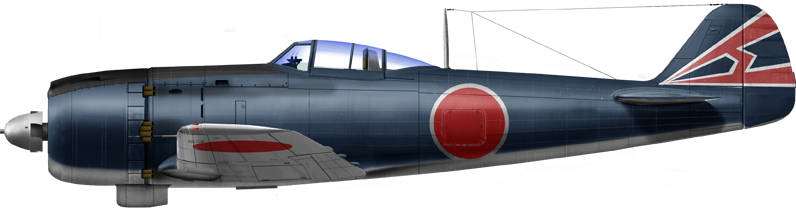

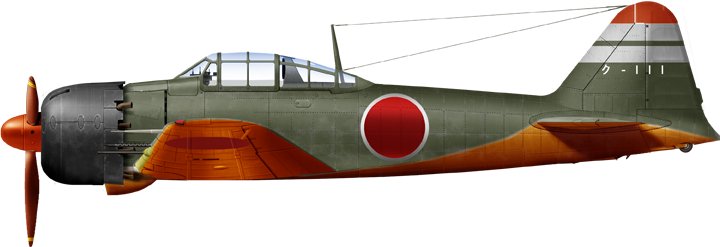

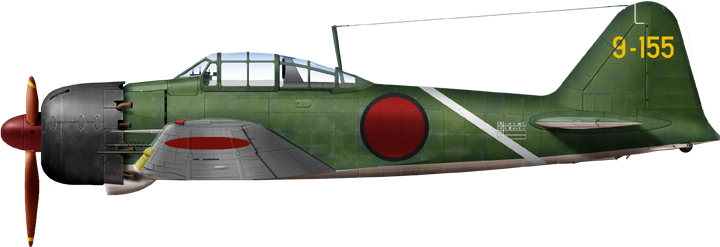

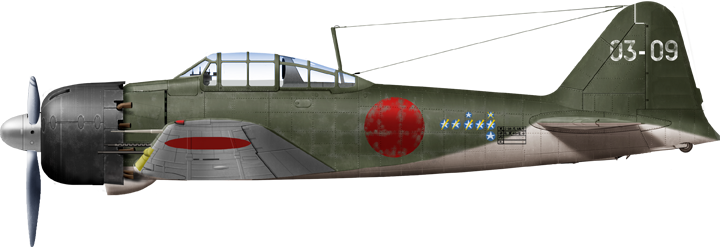

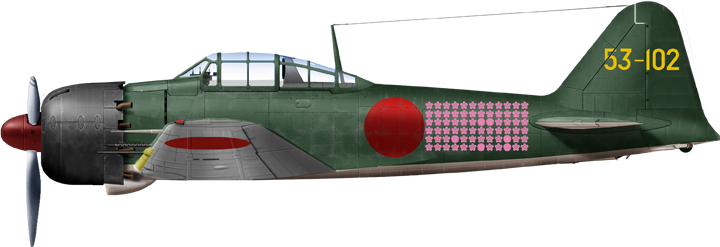

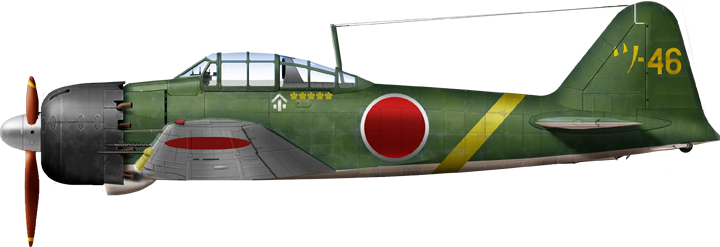

IJN Ace Nishizawa’s A6M5 UT105, 7 May 1945. The worn out dark olive green paint factory applied is well visible here.

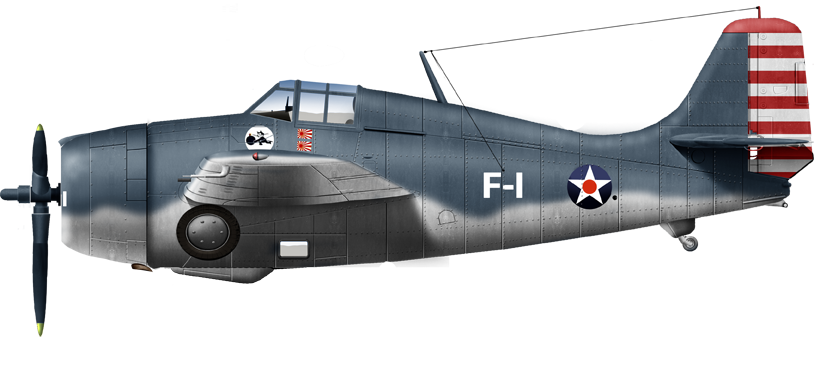

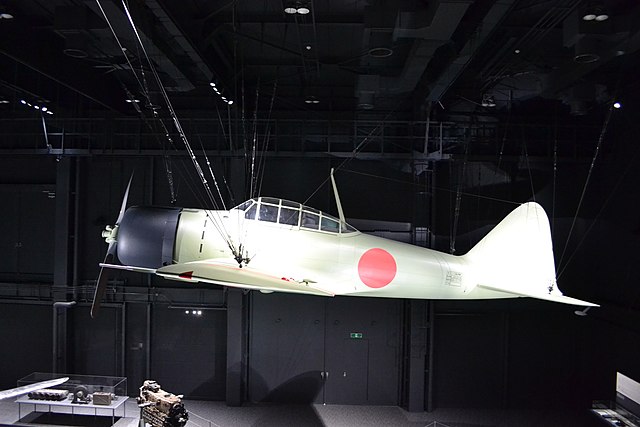

When it was introduced in early 1940, the “Zero” was one of the most modern carrier-based aircraft in the world. Its oppositon in the Royal Navy was the heavy Fairey Fulmar and in the US Navy the Brewster F2A Buffalo, to the point of being superseded by the Grumman F4F Wildcat. Until the introduction of the F6F Hellcat from mid-1943, the Zero was almost “untouchable”.

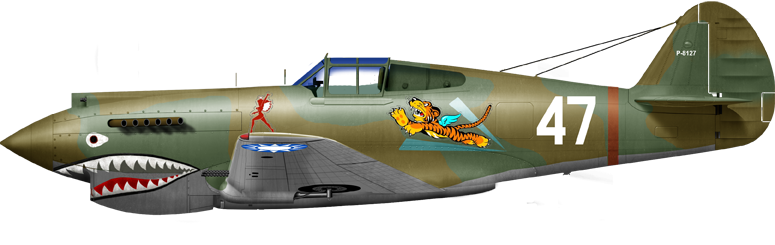

Its main advantages as a dogfighter were a fairly high-lift, low-speed wing and very low wing loading. It also had a very low stalling speed (below 60 knots or 110 km/h, 69 mph). Its “phenomenal” maneuverability as recoignised by its foes over China and Chennault’s “Flying Tigers” already in 1940 (equipped with the Curtiss P40 Warhawk) allowed the A6M to out-turn any Allied fighter of the time. Eearly models were fitted with servo tabs on the ailerons, after pilots complained about too heavy commands at above 300 kp/190 mph. That was the price for lightness as, these features were planned bu not included. However, servo tabs were retired, as with this lightened control forces pilots had much confidence to overstress their airframe, making quite vigorous maneuvers while not always grasping how flimsy was their fighter to endure G-Forces.

In fact, first information seeping through about the new Japanese “superfighter” arrived peacemeal in Europe and America, both in vague and contradictory terms. The existence was noted in reports by many observers, notably Colonel Claire E. Chennault, working still as an adviser to Chiang Kai-Shek, before meeting them in person with the “Flying Tigers”. These messages were not given the same importance given the isolationist policy of the US at that time. This majority simply wanted to prevent an increase in military spending, and spread the opinion that this new mystery fight was just a “pale copy” of European models. There were some ground for it, with only proofs such as licensed/copies of the Hamilton-Standard propeller, Bendix chassis, Palmer tires, “Sperry”, “Pioneer” and “Collsman avionics, “Oerlikon” cannons and “Vickers” derived light machine guns. At the same time, the press was far more enthusiastic about the new Lightning, Corsair, and Mustang in development, they assumed would be infintely superior.

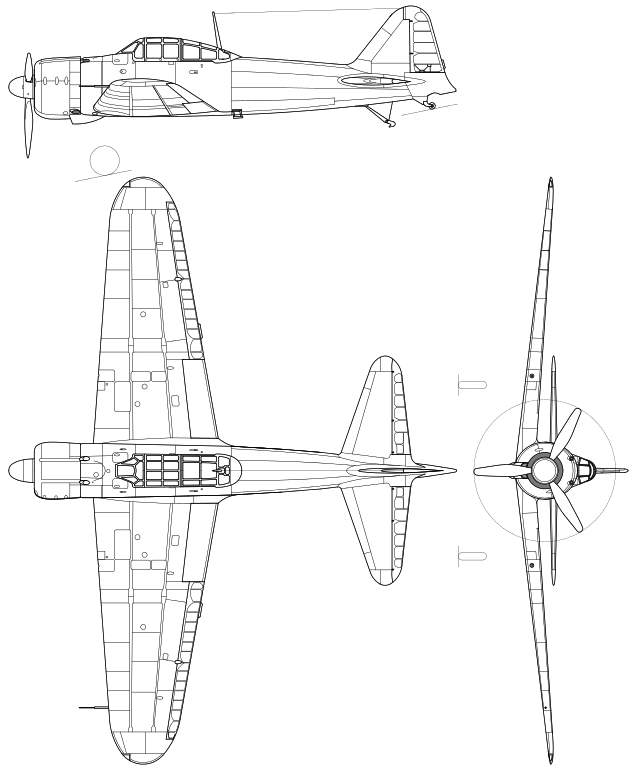

A6M2 drawing

However the rampaged of the Zero in air battles in China also convinced the Japanese military that Japanese aviation overall could gain incontested air supremacy, not only over China, but over Asia at large. The common belief at the time was that a single Reisen even in the hands of an experience pilot, could down from two to five enemy aircraft in a first encounter. Such calculations were recalled during heated discussions when considering war against the USn despite contradictory opinion (generally from the Navy and Yamamoto in particular) about the economic superiority of the United States.

The hope of a short war, just like in Germany in 1939 was that six months would be sufficient for Japan to expand rapidly in all the pacific and create a “glacis” containing enough resource for a possible war or attrition although most believed (hoped) that the “decadent west” and rampant pacifism would prevail. Qualitative advantage was seeked for already in all branches of the military, navy included (examples were many, like the “long lance torpedo”, the Yamato super-battleships, giant aircraft-carrying submarines, superior destroyers and cruisers, etc.).

The “superfighter” fully met this picture. But its high qualities, praised at the start and proven time and again until late 1942, brought the IJNAF it’s own demise, as specialists of Kaigun Koku Hombu missed the moment when work on its successor, from a black page, was to start. It should had started right in 1941, but at the time the military simply did not believe their wonder machine would become obsolete within the “six month” campaign credo. A fatal mistake as the Zero soldiered on until 1945 with significant but not game changing improvements.

Production & Variants

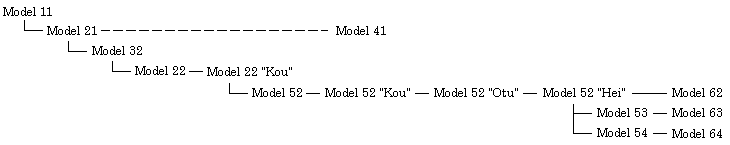

Technical tree of all versions

In the end, Mitsubishi, which facilities were tailored initially for peacetime and had a rather low output and limilited possibilities only produced 3,879 out of more than 10,000. This is, ironically its competitor, Nakajima, who assembled the remaining 6,215. The remainder were 844 spread between trainers and floatplanes, also built by Nakajima, which had larger and better facilities.

A6M1 (1939)

Initial prototypes, two which carried this A6M1 designation. The A6M1 was really the ideal “pure” zero as it was first thought of. It’s super light structure made the best of the 700+ hp of its tiny original engine, manoeuvrability was superb with a turning circle barely larger than that of the A5M, and extraordinary range for any fighter. The two prototype A6M1s were powered by the air-cooled, supercharged, 28.017 liter (1,709.7 cubic inch displacement) Mitsubishi MK2C Zuisen 13, 2-row, 14 cylinder radial rated for 780 horsepower (takeoff). It was coupled with a two-bladed variable pitch propeller, later three-bladed Sumitomo constant-speed propeller after early trials (license-built Hamilton Standard). The second prototype was called c/n 202 and contributed to the September 1939 acceptance trials by the Navy. Next would be production (pre-prod batches initially) A6M2s. Name Rei Shiki Sento Ki, or “Rei-Sen,” was chosen.

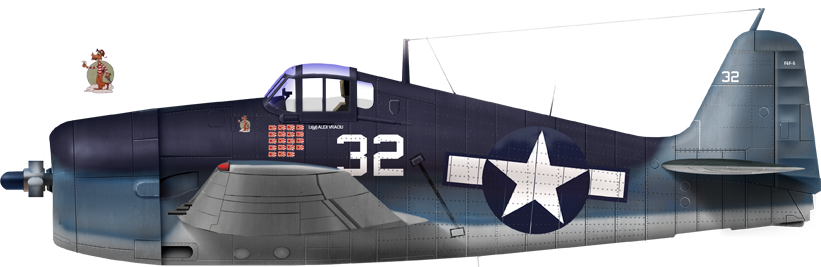

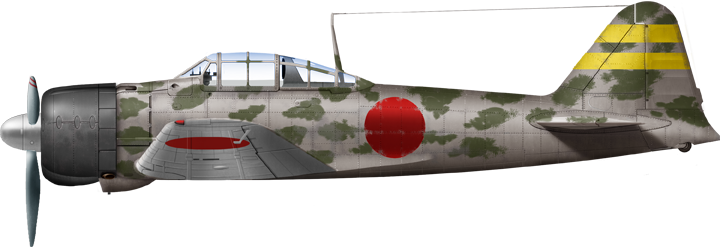

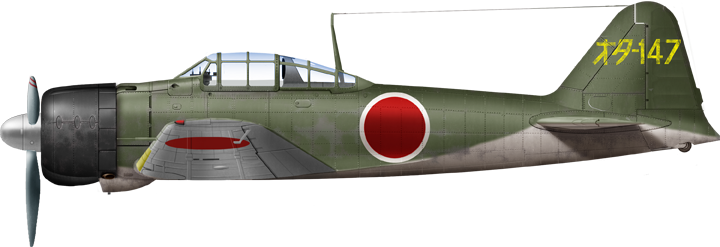

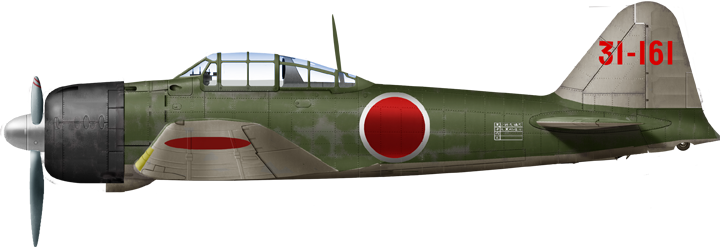

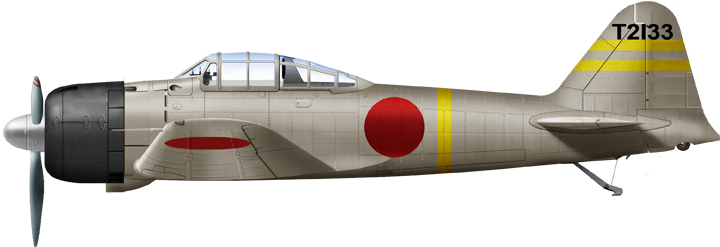

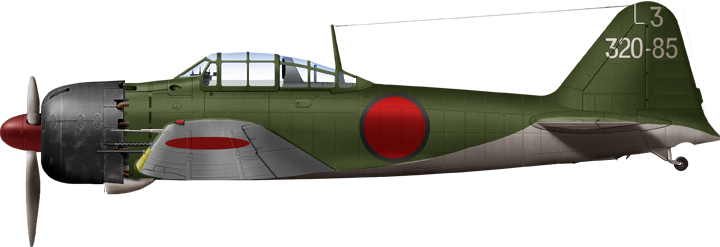

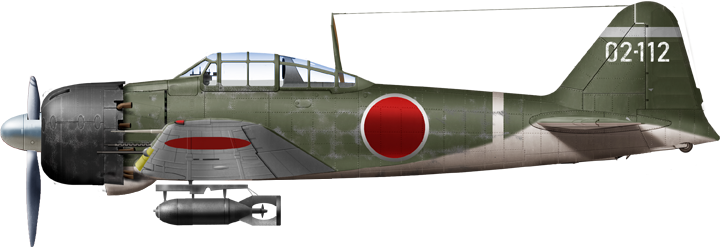

A6M2 M11 and M21 (1940)

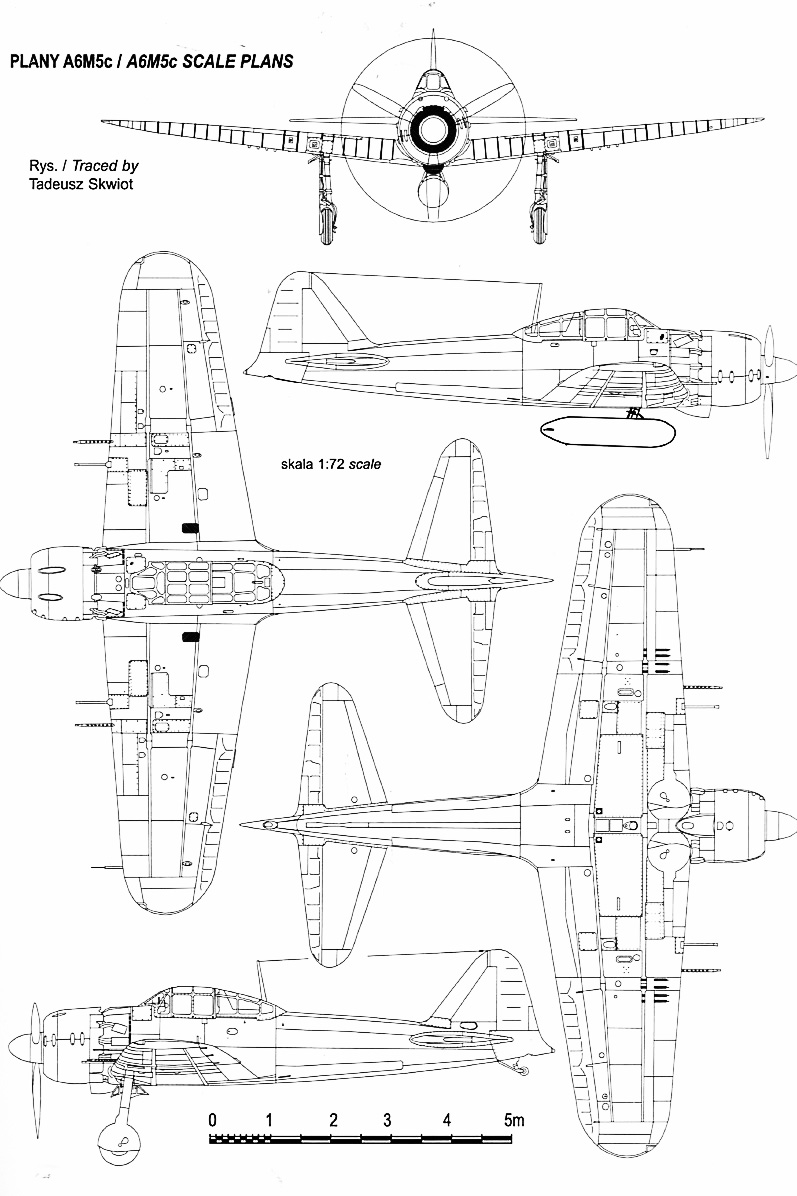

Tech cutaway of the A6M2

A total of only sixty-four A6M2 model 11 with serial numbers from 3-67 were built. The first wave of modifications saw the strengthening the rear spar of the wing from the 22nd model. From 37th location of the exhaust pipes was moved away to the fourth flap regulating engine cooling and fifth. The port’s cross section for the wings guns was reduced, the cabin air inflow holes for ventilation were relocated at the leading edge of the right wing console. The 47th introduced a modified glazing of the cockpit rear canopy.

Tests on board Kaga the fit in a standard lift to be very tight, with a gap too small to safely move it from the hangar to the flight deck and back. Personnel successfully coped with this problem nevertheless, fing ways for a perfect firt on the lift each time, but doubts came about the same in the heat of battle. So Mitsubishi introduced wingtips manually fold. Minor improvements consisted in changing the cross section of the cannon ports, cabin ventilation air intake, leading to the A6M2 model 21.

From the 127th the Model 21 received a new aileron balancer adjustable on the ground after the April 17, 1941 crashed that killed Lieutenant Shimokawa due to vibrations (see abiove). From November 1940, it was also built by Nakajima (Koizuma plant) in two years, for a total of 740 A6M2 model 21 at Mitsubishi and 800 for Nakajima, which developed from it the A6M2N “Rufe”.

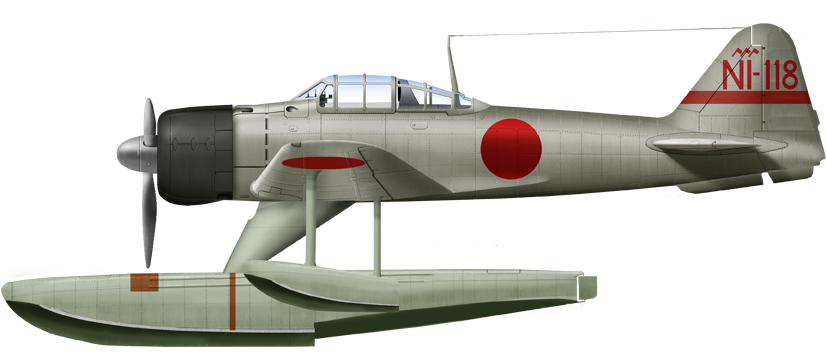

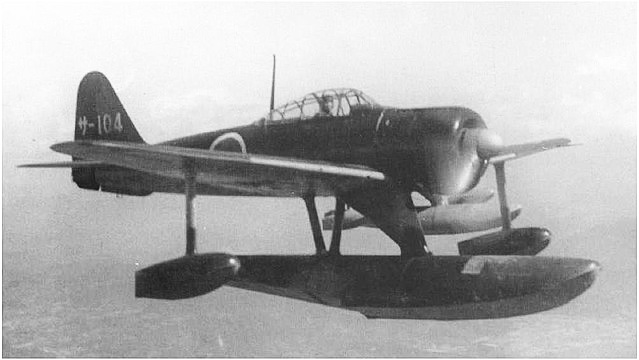

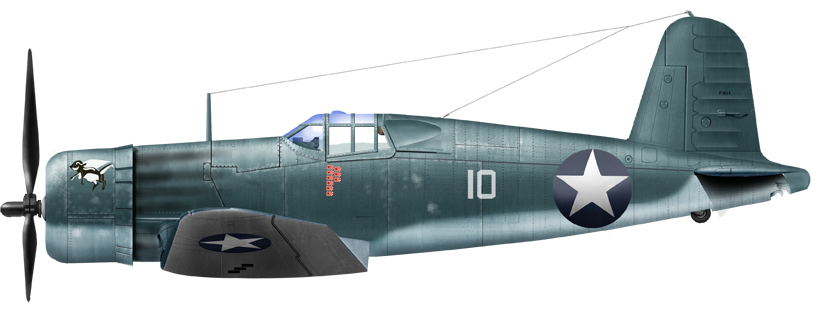

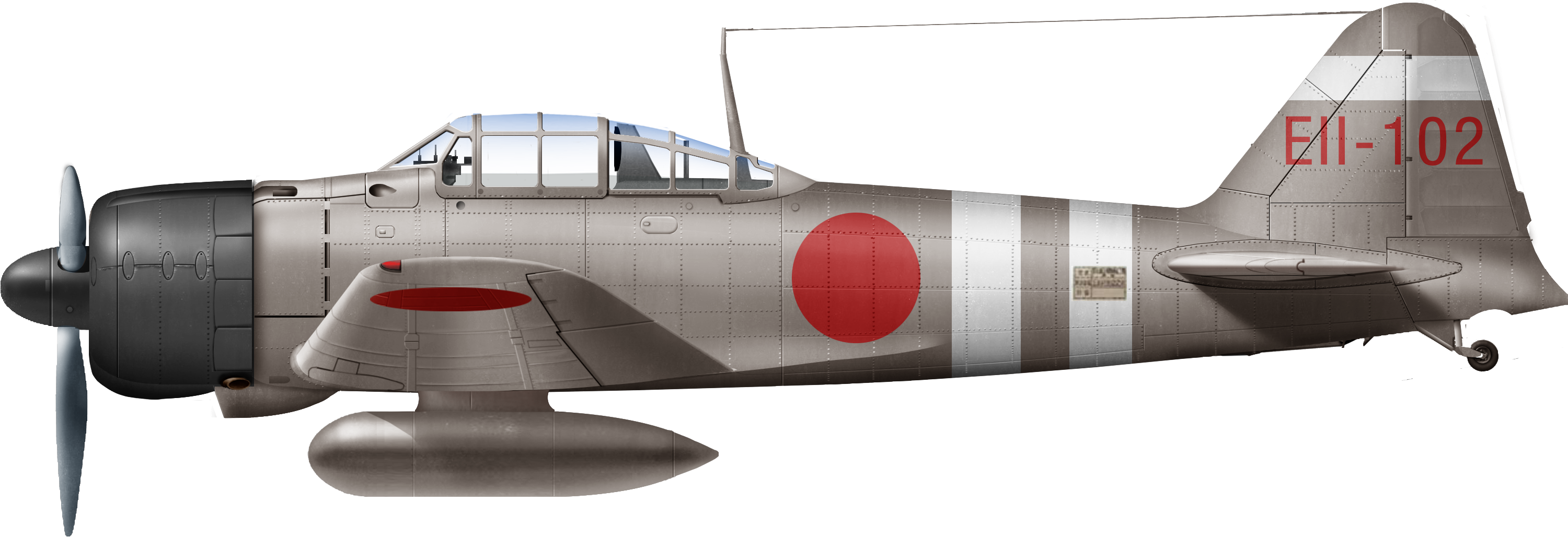

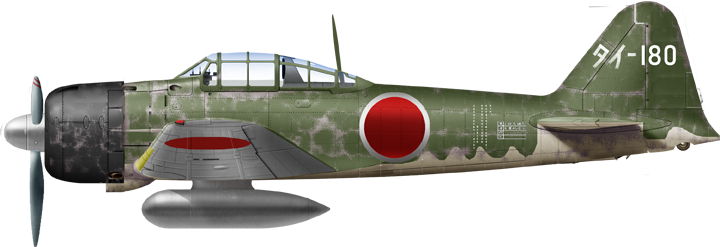

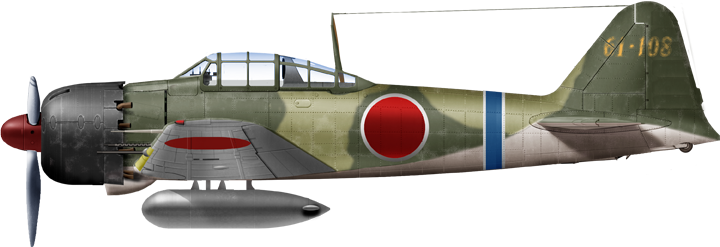

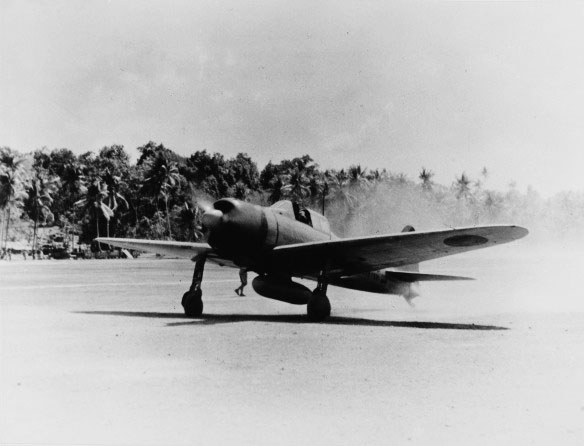

The “zero floatplane”: A6M2-N “Rufe”

The A6M2-N floatplane was developed as requested by the Navy to support amphibious operations (operated by one of the many IJN seaplane tenders), or defend remote bases. Based on the A6M-2 Model 11 technically, it had a modified tail to keep stability with a much higher drag, cauised by the added floats: One large under the fuselage to keep balace and two small underwing. 327 total were built, and it was deployed in 1942 as the “Suisen 2” (“Hydro fighter type 2”). Its first actions were mostly defensive, in the Aleutians and Solomon Islands. They were found surprisingly good at harassing PT boats at night, causing the latter to increase AA and adopt projectors. They were also found useful to drop flares on them, allowing destroyers to fire on them.

A6M2-N also were used to protect fueling depots in Balikpapan and Avon Bases in the Dutch East Indies, sparing land fighters or the Shumushu base in the North Kuriles, relatively “quiet” sectors. They were operated notably in several operations from IJN Kamikawa Maru in the Solomons and Kuriles and the Hokoku Maru and Aikoku Maru during the Indian Ocean raids. The Aeutians saw the first kills, RCAF Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, Lockheed P-38 Lightning and B-17 Flying Fortress. They were found versatile enough to be used for patrols, as fighter-bomber and short reconnaissance support during amphibious landings, spotting targets of opportunity for escorting vessel’s artillery.

The “Otsu Air Group” used them alongside the Kawanishi N1K1 Kyofu (“Rex”) from the Biwa lake, Honshū area. The French forces in Indochina managed to captured and test one of these, until crashed after being overhauled.

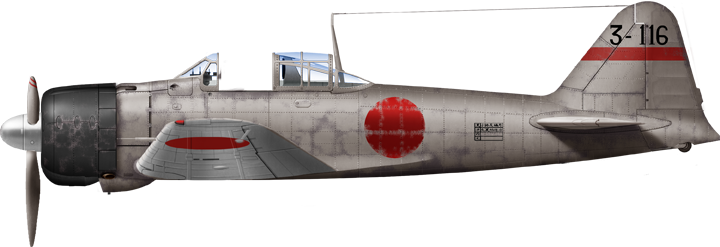

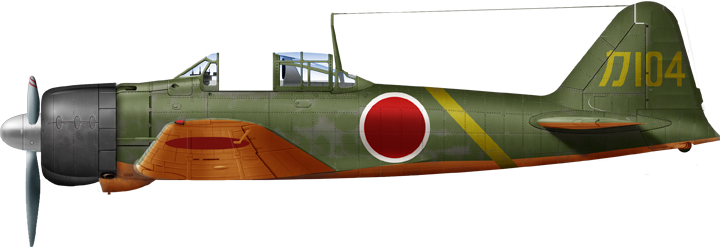

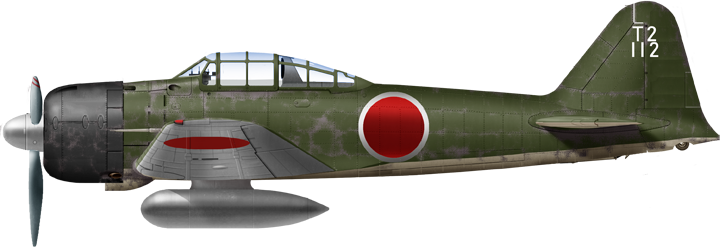

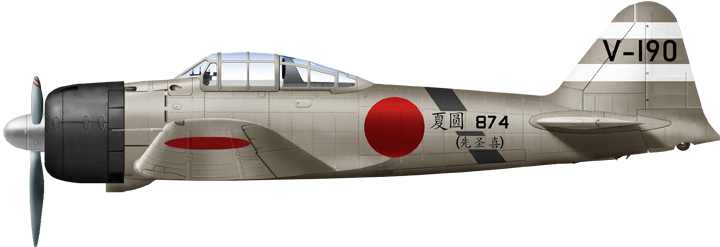

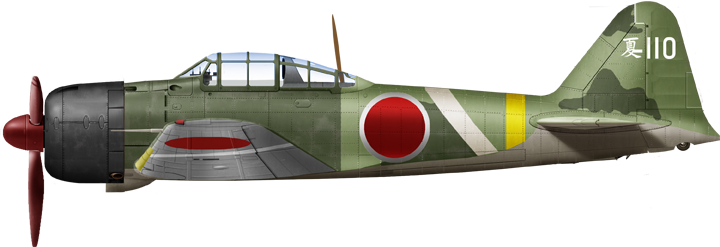

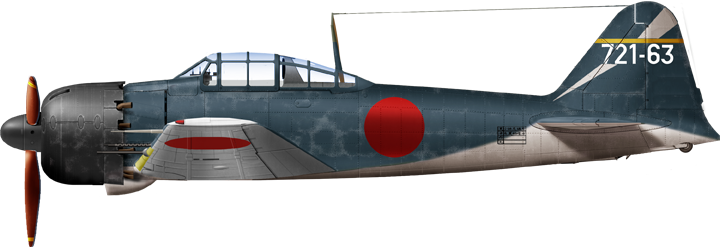

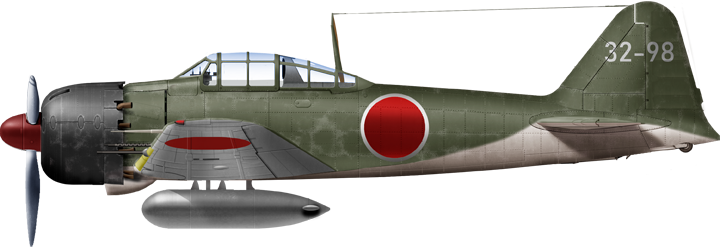

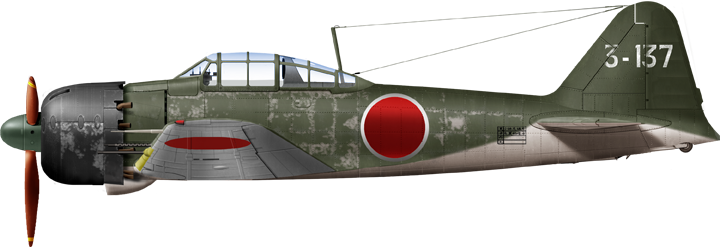

A6M3, the chopped off wings version

A6M3 M21

By mid-1941 the company agreed with pilots that the recently introduced A6M1 needed modernization. It turned out the pilots wanted to strengthen firepower but it was not done due to structure issues, and improving maneuverability was not considered, however speed qualities were. The adoption of the Sakae 21, with its two-stage mechanical supercharger and improved gearbox plus upflow carburetor for a, output of 1130 hp, improved high-altitude characteristics, but the increased weight diminshed somewhat agility.

To compensate the fuselage’s fuel tank was reduced from 98 to 60 liters, whcih reduced the range accordingly. An advantage early in the war, it was not that important. The hood was also modified, to accomodate a new supercharger air intake above the engine, raised with now machine gun’s characteristic channels. An automatic, larger propeller of 3.05 m was also installed from 4th production model, and ammunition load (by default of armament) went from 60 to 100 shells per barrel for the main wings 20 mm guns. It was in larger drums, protruding beyond the wing, so now covered by a fairing. Ailerons were also modified, without the initial and fragile complex two-stage control system.

A6M3 M32

The A6M3 entered service in June 1941, so even before Pearl Habour, and had their first tests in China. Reports shows performances were increased to a lesser extent than expected. Many pilots also wanted to abandon the wing folding mechanism. Designers when decided to have the wingtips cut off along the folding line for it to still fit. Speed also increased a bit, and the wings surface lost, about a square meter deteriorated maneuverability to the price of increase climb rate at 6000 m in 7 min 19 s (7 min 27 previously). The A6M3 model 32 as a new model however experienced teething problems with the Sakae 21 engine, and production of just 32 was only reached by July 1942, with 343 total. This was pinprick compared to the next, main production version which was the one mostly encountered by pilots.

The “chopped off” wings version was assumed by the allies to be a new model and received the codename “Hap” (nickname of the USAAF General Henry Arnold), which ordered it was changed to “Hump” and eventually discarded in December 1942, and eventually with better intel, was called “Zek 32”.

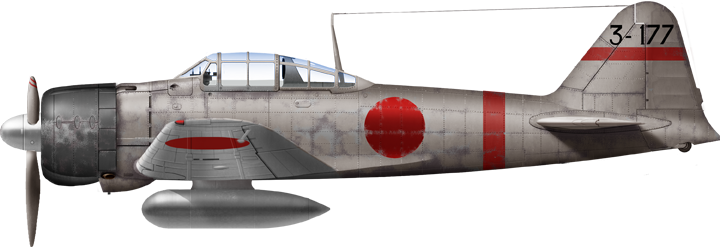

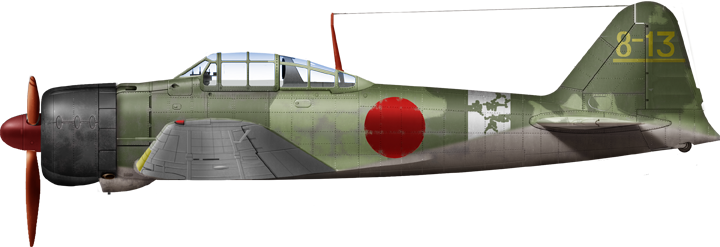

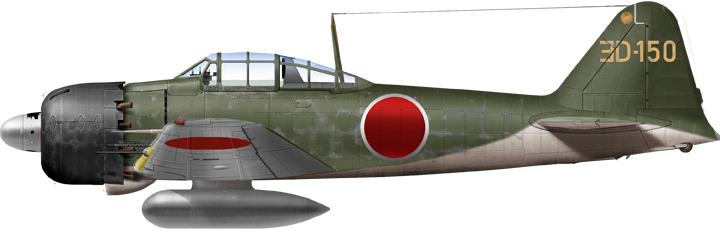

A6M3 M22

When the Zero Model 32 arrived in frontline units a fierce battle developed over the Solomon Islands, compounded later by the crippling losses at the Battle of Midway and lack of airfield network in the combat area. This the admiralty returned to the demand of reclaiming range of the Zero, tat least close to the one of the A6M1. For this purpose, the A6M3 model 22 appeared with two additional fuel tanks holding each 45 liters located in the wing, near the weapon bays. Not to impair maneuverability wings were back to their elongated folding wingtips. In all, 560 model 22 were produced, including some Model 22a, improved with their type 99 model 2 guns with elongated barrel. Three aircraft also tested a new 30-mm guns, but the wings were just too “delicate” to withstand their recoil. Both variants of the A6M3 m32/m22 were built by Nakajima, to increase radically production numbers.

A6M4: The high altitude interceptor

The A6M4 model 32 was a new version using a turbocharger was used. Only two prototypes were built tested at the 1st technical arsenal of the fleet. Mitsubishi in fact forgotten all details about the designation “A6M4” and exact production records and Jiro Horikoshi himelf did not recalled the details. The model was developed in secrecy in a separate workshop around a small team. “A6M4” appeared on a captured Japanese memo at the Air Technical Arsenal dated 1 October 1942, only mentioning a “cross-section of the A6M4 intercooler”. Design and testing of this turbo-supercharger performed by First Naval Air Technical Arsenal at Yokosuka generated a report and at least one photo of a prototype exists, showing a turbo unit mounted in the forward left fuselage.

The main problem was then to get suitable alloys for the manufacture of the turbo-supercharger and its ducting. Bad quality materials caused ruptures, fires and degrading performance which cancelled further developments. The navy never accepted it, so the potential numbers Model 41/42 were never formalized, whereas the arsenal still used the designation “A6M4”. This experience was not lost as it povided technocal backrgound for further tests and engine designs. If production was never launch, Japan would never have its interceptor variant, the Zero staying a low-alt dogfighter to the end. But the J2M became that “bomber killer” ask for later, and work done on the A6M4 contributed to it.

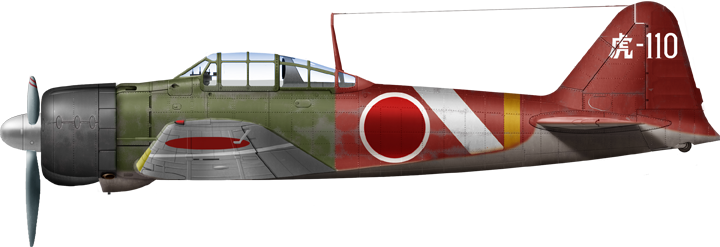

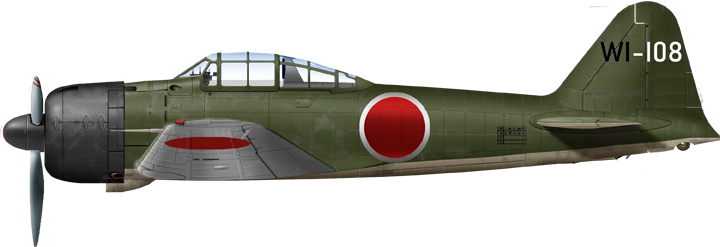

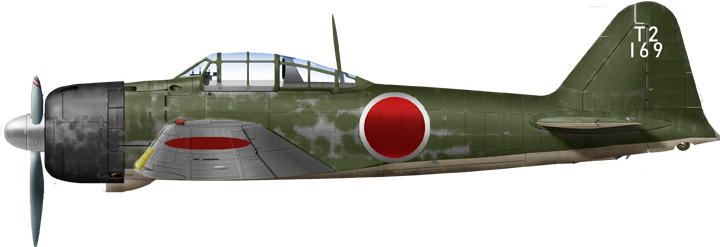

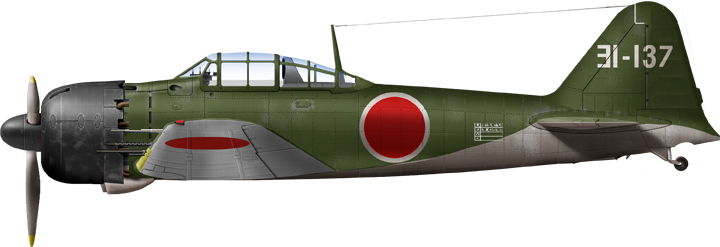

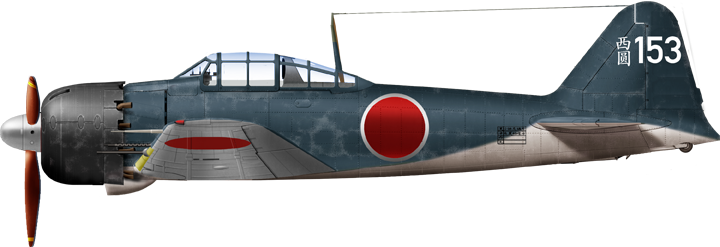

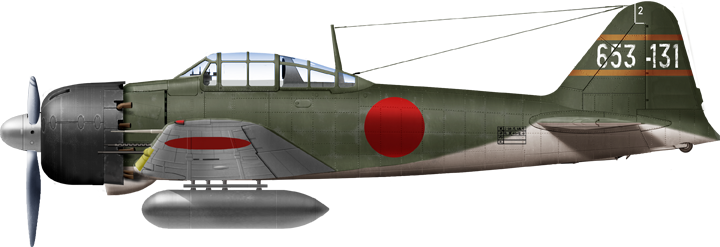

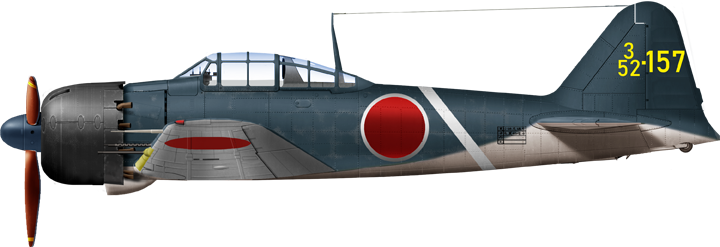

A6M5

This was by far, the best known, best produced and numerically largest variant of all. But it was also the challenger of the new F6F Hellcat, among others. Its genesis went back to late 1942, when pilots reported on possible improvements on the A6M3. What became the Model 52 started over the same issues of getting rid of the mediocre wingtip folding system but shortening the wings while increasing speed. The aileron trim tab and flaps were revised first, and Nakajima, due to the poor daily rate of Mitsubishi, took on the bulk of the production. So the model could have been seen as the “Nakajima A6M5”. The prototype was created in June 1943 based on a production A6M3, making its maiden flight on August 1943. Performances were average, but better than initial models, thanks to hood and exhaust modifications, topping at 565 km/h (351 mph)) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) with a climb rate of 7:01 minutes.

It seems that early production models were still fitted with the same exhaust system and cowl flaps as on the Model 22, but the upper cowling was redesigned towards the Model 22, while a new exhaust system was worked on, providing better thrust by spreading stacks aft with better distribution. The new exhaust system was completed by “notched” cowl flaps, and heat shields aft, not to damage the fuselage. From the 4274th model, another incremental improvement came with wing fuel tanks adopting for safety, carbon dioxide fire extinguishers. Still not self-sealing, that was at least one protection measure, sorely lacking. From #4354, a new radio, the Model 3 with its aerial Mark 1 with a shortened antenna mast were standardized. From #4550, the lowest exhaust stacks were made even compared to those above, but the first pilot flying it, reported these burned the forward edge of the landing gear doors and compromised the tires so from the next plane, #4551 Mitsubishi install even shorter lower exhaust stacks. Nakajima manufactured the Model 52 at Koizumi (Gunma Prefecture). The

A6M5a, Model 52

The M52 Ko, appeared from #4651 at Mitsbushi.

-Its armament was modified, getting rid of the Type 2 drums for the belt-fed Type 99-2 4-shiki, with 125 rounds per gun (25 more) and the underwing could be better streamlined, with the elimination of the bulge. The ejection port for spent cartridge cases was moved also away.

-Another modification which was well awaited, was about extra rigidity, with a thicker wing skinning installed, for greater diving speeds.

A6M5b, Model 52

The 52 Otsu was mostly concened by an armament change over the hood:

The old 7.7 mm (.303 in) Type 97 gun (750 m/s (2,500 ft/s) the right forward was replaced by a single 13.2 mm Type 3 gun capable of 790 m/s (2,600 ft/s) for muzzle velocity and a 900 m (3,000 ft) range, 800 rpm and storage for 240 rounds. It needed also an enlarged opening and channel, creating an asymmetric appearance on the cowling.

-The other main modificaton was a revised gas outlet near the windscreen.

-Each wing cannon received a fairing on the leading edge.

-An armored glass 45 mm (1.8 in) thick was fitted to the windscreen as protection.

-A larger propeller spinner was fitted.

-The ventral drop tank was changed, having fins and suspended instead on a slanted pipe.

The first of A6M5b or “M52 Ko” was tested and ready by April 1944, production ending in October 1944.

A6M5c (Model 52 Hei)

The final production variant of WW2.

-An extra 13.2 mm (.51 in) Type 3 machine gun was added in each wing, outboard of the cannon, with the right reinforcements. The left hood 7.7 mm gun was deleted and not replaced. But this version overamm had three 13 mm and two 20 mm guns, ending as the best armed Zero in service.

-In addition, it was modified to carry four racks underwings, to be used to carry rockets or small bombs, located outboard of the 13 mm wings guns.

-Major change, the engine, a Sakae 31 engine, for increased performances

-For protection, an extra 55 mm (2.2 in) thick piece of armored glass was installed at the headrest.

-Also a 8 mm (0.31 in) thick plate was installed behind the seat. At last the pilot got the protection it deserved.

-The central 300 l (79 US gal) drop tank was changed to a four-post design.

-Wing skin was thickened for better dive performances, with detailed structural improvements.

The first A6M5 made its maiden flight in September 1944, but it was not a good dogfighter and was used at the time mostly as an intercepting to reach B-29s and for “special attacks” (Kamikaze raids).

The ultimate sub-version was a “pure” interceptor, the A6M5-S (A6M5 Yakan Sentōki) and dedicated night fighter. The armament was changed as a single 20 mm Type 99 cannon was installed behind the pilot aiming upward, and inspired by the Luftwaffe’s Schräge Musik installation which prototype and plans were carried by submarines. There was no radar and thus this variant was basically “blind” and only vectored from the ground to a probable location.

There were also experiments of a bakusen, a fighter bomber, with Model 21 and 52 converted with a bomb rack holding a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb, replacing the drop tank. Numbers so converted are unknown.

Also, the Model 52 was converted into the specialized A6M5-K two-seat trainer at the end of the war, in short numbers as advanced trainer by Hitachi, but mass production never started.

A6M6

The A6M6 Type 0 Model 53 was developed to take advantage of the Sakae 31a engine with a newly designed water-methanol engine boost, plus self-sealing wing tanks, something that was expected; Preliminary testings however were disappointing, with not notable increase of power and unreliability of the fuel injection system. Testings went on until it was dedided to cancel this version, amidst priorities. Only a single prototype was produced. This version shows how much the IJN was desperate to see a power increase on its warbird, by all means possible. But the basic structure was simply not to accept larger engines. There was no way around a complete redesign.

A6M7

This brings us to the natural successor of the Zero, the A7M Reppu, developed better below. However engineers at Mitsubishi were not done yet. The A6M7 Type 0 Model 62/63 was at least a rare variant to see service, the very last. It was designed to meet a new Navy requirement for a dedicated attack/dive bomber version operable from smaller aircraft carriers and/or replace the Aichi D3A2 on a lighter package than the Suisei. The A6M7 was completely modified for for dive bombing, with a reinforced vertical stabilizer, special bomb rack underbelly and racks underwings for two 350 litre drop tanks plus bomb swing stopper underside the wings. It received naturally the last engine, the Sakae-31 capable of 1,130hp at take-off. Gun/MG armament was also the same as the A6M5c. The model was capable of carrying a single 500kg bomb. Production started by May 1945 but the need for it radically declined and it was used more in the “special attack” (kamikaz) role, in particular over Okinawa.

A6M8

Basically the same attempt of power improvement as the A6M6 but with a Mitsubishi Kinsei 62 engine capable of 1,163 kW (1,560 hp), making a 60% power increase compared to the A6M2. The cowling and nose were completely redesigned. The carburetor intake was massively enlarged as on the B6N Tenzan with a long duct, exhausts modified, and large spinner similar to the Yokosuka D4Y which shared the same engine. The larger cowling also had the advantage of allowing larger nose MGs, both 13.2mm Type 3 models. Eventually, four 20mm Type99 shiki-2 cannons were fitted in the wings, two paired, with the same ammunition figures of 125 rounds, belt-fed.

To regain range also, this ultimate Zero carried two 150 l (40 US gal) drop tanks underwings. Under the fuselage two new racks were installed, designed to be capable of holding 250 kg (550 lb) bombs. However the most ever powerful zeros never saw service: Only two prototypes were completed in April 1945. Despite an IJN order for 6,300, production never materialized and US troops captured the two prototypes having completed all their tests flights.

Detailed specs

Specs A6M5 (1943) |

|

| Crew: | 1: Pilot |

| Fuselage Lenght | 9.06 m (29 ft 9 in) |

| Wingspan | 12 m (39 ft 4 in)11 m (36 ft 1 in) |

| Wing area | 22.44 m2 (241.5 sq ft), Aspect ratio: 6.4 |

| Airfoil type | Root MAC118/NACA 2315, tip MAC118/NACA 3309 |

| Weight Empty/Gross/Max TO: | 1,680 kg (3,704 lb)/2,796 kg (6,164 lb)/2,796 kg (6,164 lb) for the A6M2 |

| Max takeoff weight: | 1,671 kg (3,684 lb) |

| Propeller: | 3-bladed Sumimoto constant speed metal propeller |

| Engine: | Nakajima Sakae 21 engine 14-cylinder air-cooled radial 1130 hp (see notes) |

| Fuel cap.: | 518 l (137 US gal; 114 imp gal) internal and |

| Top speed: | 600 km/h (370 mph, 320 kn), 533 max, 333 cruise at 4,500 m (14,930 ft) |

| Climb rate: | 15.7 m/s (3,090 ft/min), 6,000 m (20,000 ft) in 7 minutes 27 seconds* A6M2 |

| Wing Loading: | 107.4 kg/m2 (22.0 lb/sq ft)* |

| Endurance: | 1,870 km (1,160 mi, 1,010 nmi)* A6M2 |

| Ferry Range (straight A to B): | 3,102 km (1,927 mi, 1,675 nmi)* |

| Service ceiling: | 9,800 m (32,200 ft) |

| Wing Loading: | 93.8 kg/m2 (19.2 lb/sq ft) |

| Power/mass: | 0.3161 kW/kg (0.1923 hp/lb) |

| Armament | 2× 7.7 mm (0.303 in) hood, 2×20 mm wings guns |

| Other payloads | 1x 330 l (87 US gal; 73 imp gal) drop tank* A6M2 |

The A6M in action

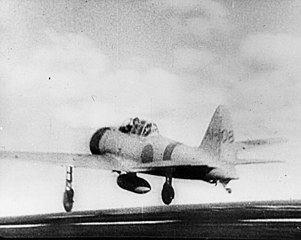

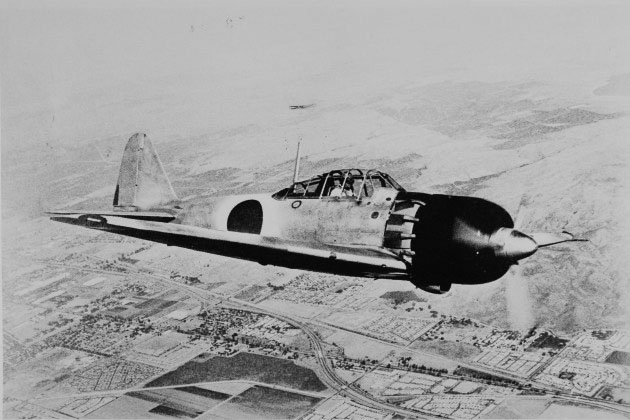

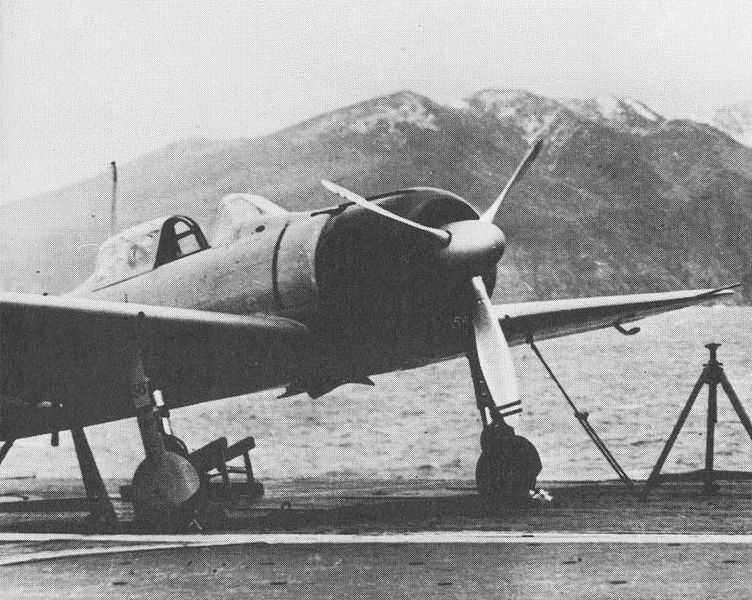

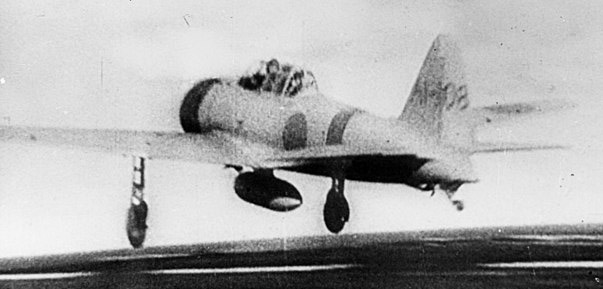

Type 0 A6M2 taking off from IJN Akagi for the Pearl Harbor attack

First engagements over China (1940-41)

As said above, its the flight group Yokohama Kukutai, that cemented the reputation of the aicraft over China, based in Hankow. The kill ratio obtained at the time was simply demential. It was way above that of the F6F later in the war, and was not kept as high due to the degrading quality of the pilots, opposition and context later in WW2. So the overall picture was far less favourable, and after starting on a 12 to 1 kill ratio, from mid-1942 it rapidly started to fall, until reaching by late 1942 and early 1943 something closer to 1:1. By mid-1944 it has been radically inverted to 1:12, and even dug deeper.

The first pre-series A6M2 with the 12th Rengo Kōkūtai started operatuins by July 1940 and on 13 September 1940 had at last their first victories when 13 A6M2s led by Lieutenant Saburo Shindo, escorting a group of G3M “Nell” bombers over Chunking repelled the attack of 34 I-15s and I-16s and claimed 27 of them for no loss. However four Zeroes sustained some damage, and until their retirement in September 1941, they had claimed 99 Chinese aircraft, local conservative figures, and 266 according to Japanese sources. A massive divergence which is quite common at the time and did not help historians today.

By early 1941, the presence of the A6M spiked, well helped by a superior range, many based at Hankow and recently captured airfields to help Japanese forces progessing into the mainland, and from carriers close to the coast, the assigned area of operation of the IJN. But this grow was done at more a limited pace from mid-1941, with the introduction and testing of the A6M3, of which only a few preseries saw action. Air groups were soon back on carriers and back home for extensive training in preparation for future operations. In fact it was even supposed to be withdrawn already in the late summer of 1941 (So late August to early to mid-September). Therefore, in the fall of 1941, all sights of the A6M made by AVG Flying Tigers were actually cases of mistaken identity. However there is the Gerhard Neumann case, a German-born refugee which was part of Chennault’s team. He allegegly reconstituted several downed/forced landed zeros as late September 1942, so a full year after Japanese allegedly retired it from the area;

However, there are missing records for some IJNAF units, which could have led to believe they stayed behind, probably with the earlier A6M2, now superseded on first line service by the A6M3. And there were the Tainan Kokutai Zeros, operating as far as north of Hainan Island. On November 22, 1941, a composite fighter squadron attached to the 22nd Air Flotilla HQ was created to participate in the fall of Singapore, 14 A6M2s model 21 (Tainan Air Group) plus 13 A6M2, same model, from the 3rd Air Group flew via Saigon and Hainan Island to be based at Soc Trang, south of Saigon by December 1941. Two made emergency landings on the Luichow Peninsula. But they were not lost to enemy action from the AVG, only recuperated from scattered part by Neumann. The Chinese AF was indeed the first to have a more precise opinion on the warbird, when an A6M2 the pre-production batch, serial V-110 was recuperated in good general state on the Fainan Island, examined on 18 September 1940 by a mixed US-Chinese team led by Neumann. The crucial intel however was very slow to enter ONI database (The US weren’t at war back then).

The A6M3 and early pacific operations 1941-43

In late 1941 in preparation of the operation against Pearl Harbor, all A6M3s were stationed on carriers and in home island reserve units. Apart a few A6M2s in Indochina as seen above, the Zero was entirely focused on the upcoming pacific theater. On 7 December, from all six fleet carriers of the Kido Butai, some 521 Zeros took part in early operations, including 328 in first-line carrier units. Not all took off that day, only a fraction, as a second wave was prepared, and the remainder were kept for CAP. The Model 21 became the common encounter in these early weeks in December 1941 and January 1942, which staggering range of 2,600 kilometres fooled the US intel and high command. At Pearl, PBY searched in vain for the carrier fleet, which in reality was stationed far more to the north, based on the supposed range of the A6M. The appearing over distant battlefronts of the A6M seemed to indicate they were far more of them than in reality.

These encounters soon created a psychosis in USN and USAAF pilot’s mind, as the previously “pale copy of…” seemed on the contrary invincible. Zeros becalme quickly the bete noire of Pacific pilots, and “zeroes” were seen everywhere, even though these were often “Oscars”. This alleged superiority was not completely well funded, as its early opponents like the Brewster Buffalo on the British side, never were a match to start from. But when the FAA started to introduced the spitfire in this theater of operation, pilots were surprised of the almost supernatural dogfighting abilities of the A6M, comparating quite well with the Me-109. Some even found it superior. By late 1942 when the FW.190 appeared on the western front, both were easily compared. The A6M3 could out-turn the Spitfire with ease and sustain a climb at a very steep angle while having thrice the range.

A lot was learned at Corea Sea in May, at Midway in June, and Guadalcanal from August 1942. Allied pilots soon developed tactics playing their strenght. Avoiding dogfight and instead swoop down from above in a high-speed pass and firing a quick burst, then back up to altitude. The F4F Wildcat applied them with success at Guadalcanal and practiced a type of high-altitude ambush, using the early warning system provided by Coastwatchers and radar. They were deduced from reports in China of those used by Chennault, the “boom-and-zoom” tactics against the equally agile Nakajima Ki-27 “Nate” and Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar”. AVG pilots used their P-40s strenghts in the same way the F4F.

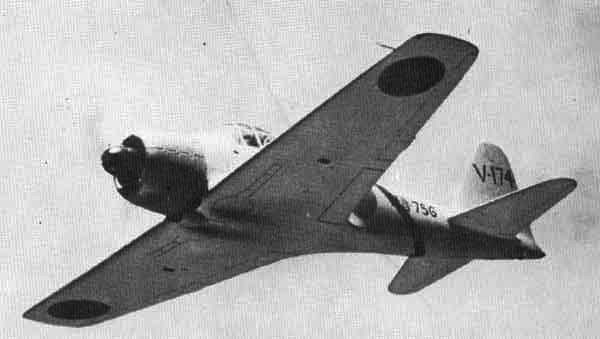

The captured restored A6M5 in flight in 1944. After the Aleutian A6M2, it brought significant improvement to allied intel on the new model, that most pilots found impressive for its low power compared to allied standards.

Lieutenant Commander John S. “Jimmy” Thach, USN ace, also introduced the “Thach Weave”, a formation of F4Fs some 60 m (200 ft) apart. If one was attacked, the remainder two would turn toward each other and surge behind the attacker. If the Japanese pilot then turned to disengaged, it would present its flank by the bait’s wingman. This was the main tactic used at the Battle of Midway and also in the Solomon, until the gradual retirement of the Wildcat. Both Coral Sea and Midway saw a large portion of the best and more experienced IJN pilots lost. Something the Kido Butai never recovered. Already during later engagements like at Santa Cruz and in general over Guadalcanal, pilot experience started to swing to the US side.

Although many officers were critical of the Wildcat, speaking of a “sluggish cat” with too short ammunition storage, Japanese pilots had a somehwat different opinion: Japanese ace Saburō Sakai for example was impressed by the toughness of opponents, as the only brake to the Zero’s total domination:

I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7 mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm cannon switch to the ‘off’ position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying! I thought this very odd—it had never happened before—and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman’s rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now.

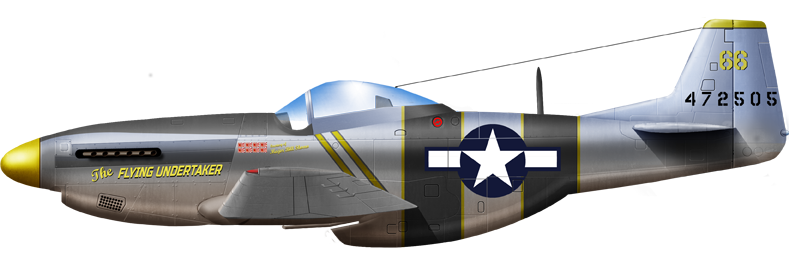

The A6M4 and late pacific operations 1943-45

The later years, after the arrival of the F6F and F4U in very large quantities and with better, more experienced pilots, the A6M5, despite being the largest production of the type, largely thanks to Nakajima, already overworked with Army fighters and countless others, met it’s demise. Despite all attempts to modernize it, the light initial structure could not be up-engined, up-armed or beefed up much in any ways. Many attemps made until the end of the war led to small experimental series only.

Until the epic Battle of Leyte in October 1945 when the IJN committed its last reserves, the number of fleet carriers dwindled dow gradually, and the great replacement plan of the new armored Taiho class and lighter Unryu class failed to materialize. Post-Midway, the fleet still had the two large Shokaku class, the Jun’yo, Zuiho, Chitose pairs, and a cohort of smaller escort, on which the A6M could still operate, but both Taiho and Shinano had fairly short careers (a single sortie for the latter!), while none of the new and promising Unryu class was really operational in time, most even never completed.

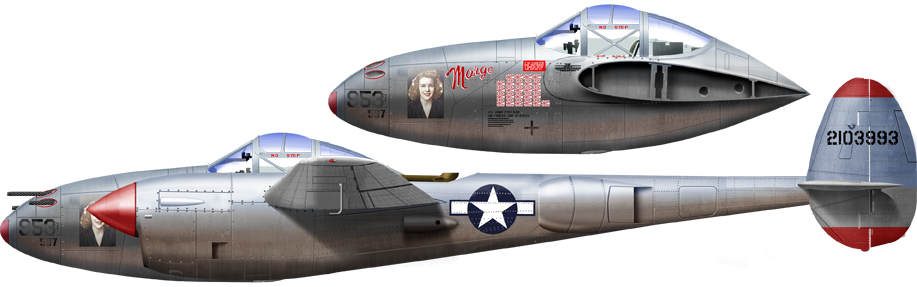

After the catastrophy of Midway, further losses at Santa Cruz and the long attrition campaign of the Solomons (notably the 1st and second battle of Guadalcanal), the Kido Butai was gradually eviscerated. Already outmatched (marginally depending on the pilot) by USN/USMC models, the USAAF also introduced a perfect “zero killer” as the powerfully armed Lockheed P-38 Lightning, which four “light barrel” AN/M2 .50 cal. Browning machine and 20 mm autocannon in the nose could be fatal in a single short burst to the A6M, whicle being able to pick its targets thanks to their speed, and even equalling the A6M in range thanks to their configuration.

The amazing raid to eliminate admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Operation Vengeance) is a good example of this. 18 P-38G fighter aircraft from the 339th Fighter Squadron arrived on the aerial convoy of 2 G4M1 bombers covered by six A6M3 fighter aircraft, after making a 600 miles out to the target, 400 miles back (1,000-mile total with extra fuel allotted). So after arriving, pilots were already too short of gazoline, to engage in any dogfight and used their speed and surprise to shoot down the two bombers, without engaging the Zeros, and then quickly turn back, loosing one P38G for a single A6M3 damage during the engagement.

The A6M5, still somewhat underarmed compared to the six Brownings 0.5 of the Navy fighters was hard-pressed but it’s main asset remained always in the hands of a skillful pilot as still, it was able to maneuver at least as well any opponents, and being still deadly in competent hands. Many aces of the 1940 era were still alive, although promoted and spared combat as commanders, to form the new generation of 1943, 1944 and 1945 pilots. Shortages of materials also started to impair construction and cause some delays, while quality generally dwindlded down, notably for the engines. While the A7M2 Reppū was awaited all along 1944 and into 1945, the A6M5 went on soldiering until the famous June 1944 “Turkey Shoot” of the Marianas, where the last commander and flying officers with enough experienced were shot down.

By October 1944, the “bait fleet”, Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s “Northern Force”, could only sent a limited number of fighters, to lure out Halsey’s TF 38. Ozawa’s tempting decoy actually had only 108 aircraft on the six carriers. The largest par of which were indeed A6M5s. Overwhelmed by several fold more fighters sent by Halsey, in two waves, they were nearly all shot down but a few.

A6M5 Model 52C prepared in Kyushu for a Kamikaze operation over Okinawa.

Afterwards, apart some incursions around iwo Jima and last ditch attacks over the Philippines, the longer Okinawa campaign coincided with the start of Kamikaze operations. In these, the improperly trained pilots of the 1945 wave, were soon mixed with students reciving the most basic training.

These A6M5 were not the best platform for such missions as they carried a small bomb load if any, and the ventral space was used by a droppable fuel tank. In Kamikaze attacks, not all fighters were destined to end as “missiles”. Trained pilots were preferred to escort the composite flights, and defend it against incoming fighters, always detected in advance by radar, until low-altitude flights were attempted by more experienced groups. The A6M5 was seconded in these operation by the fresh (May 1945) A6M7, better provided in bombs, and properly used for Kamikaze attacks, not escort.

The army rivals: “Oscar” and “Frank”

Unlike the Navy, and just as for the previous A5M/Ki-27 duel, the inter-service rivalry prevented the adoption of a Navy fighter. Both branches had similar specifications and Nakajima knew about Mitsubishi’s prototype in development. They choose to adopt the same basic philosophy as the Army asked the company to develop the fighter quicker. Compared to the Zero there were two major differences: It was to be even less rugged (land based fighters were less “tough” than their carrier counterparts) and had less range. Perhaps it’s why development ended sooner, and Nakajima’s prototype flew a month earlier.

In early 1942, unlike the Navy which just upgraded the A6M while a successor was in the works, the Navy decided to create a brand new fighter, the Ki-84 Hayate (“Frank”), which in many was was superior to the A6M5. In fact it was perhaps the very best Japanese fighter of WW2, more powerful and beter protected the Zero could ever dream to be. Its equivalent, the A6M7 “Reppu”, for several reasons, was never ready in time (see later).

Ki-43-IIb Hayabusa “Oscar” (1st Air Combat Regiment, 1st Company, 1st Squadron, Home Defence 1943)

Compared to the A6M3, it’s contemporary, the Ki-43, which first flew in January 1939, earlier than the A6M, on April 1, 1939. Also it was also lighter, and in comparative tests, out-turned the A6M2/3/5 at low altitude, but was slower at 320 mph versus 330 mph (A6M3) or 351 mph (A6M5) with aslo a slower climb rate. Alsi it’s armament was way too light, with just two 7.7 mm MGs versus the Zero’s two 20 mm (0.787 in) wings cannons. It proved also difficult to uprade with armor and self-sealing tanks without degrading it’s performances, unlike the A6M5.

On the long run, before replacement came with the Ki-84 in 1944, the Ki-84 was out-done by the A6M5 in any corner, even the late Ki-43-III “Ko” (Mark 3a) introduced in December 1944 with the JAAF. It had a slightly improved Sakae engine, individual exhaust stacks for 354 mph at med altitude but the same twin HMGs. The Ki-43 “Otsu” (Mark 3b) had the Mitsubishi Ha-112-II radial engine and two 20 mm (0.79 in) Ho-5 cannon, but the structure could not handle these and the Ki-84 in development looks more promising.

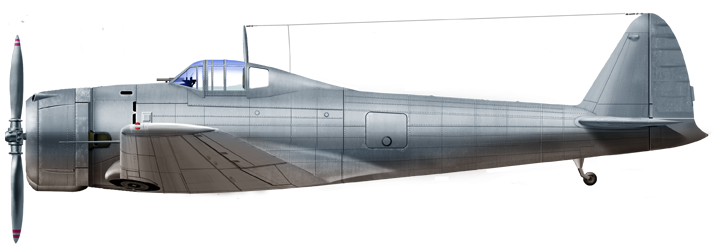

In between the Ki-43 and Ki-84 appeared the Ki-44 Shoki “Tojo”. Nakajima’s engineers in 1940 started developing a new interceptor as a private venture based on the Ki-43 cell, heavily modified, with a new engine. Eventually, a Japanese Army Air Force specification was emitted, calling for a maximum speed of 600 km/h (370 mph) at 4,000 m (13,130 ft), reached in five minutes. The new interceptor featured the in-house Ha-41 14-cylinder double-row radial engine intended for bombers inistially.

As it was larger, the fuselage was strenghtened and enlarged, but otherwise shared many points with the Oscar still. All in all, production was slow, with an average of 50 monthly, peaking at 85 in April 1944 and really starting in February 1942, with many-production models made from August 1940. The 1223 “Tojo” mostly made operated from Japan to intercept bombers, and was the equivalent of the later Navy J2M. It’s development work paved the way for a more agile, less specialized model that became the Ki-84.

Ki-84 Hayate “Frank” (1943) (Author’s illu)

The Hayate was probably the best mass-produced fighter of the IJA (Imperial Japanese Army) in WW2. In performances it was superior to the liquid-cooled powered Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien “Tony” but inferior to the Ki-100, the same re-engineered with a radial, something a bit counterintuitive. The IJAAF Ki-100 by coupling a Mitsubishi Ha-112-II radial to a Ki-61 fuselage in 1945 was marginally better as an interecptor. It was too little, too late however.