North Carolina class Battleships

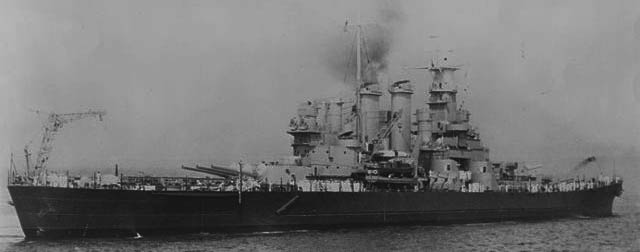

Fast Battleships (1940): USS North Carolina (BB-55), Washington (BB-56)

Fast Battleships (1940): USS North Carolina (BB-55), Washington (BB-56)

The first USN fast battleships

USS North Carolina’s bow, Pearl Harbor, 16 November 1942

The North Carolina class battleships were a revolution for the US Navy: After the long vacancy of the Washington Treaty banning new battleships for ten years and prolongated by the London Treaty until 1936, there was a considerable gap in studies which the Admiralty Board knew both BuEng and C&R needed to gap quickly when new designs would be authorized. The design process really started in 1935 and was finalized in 1937, resulting in two very innovative capital ships unlike anything built before. They not only inspired the next North Dakota and Iowa class, but the reconstruction of the battleships sunk at Pearl Harbor as well. These two ships in addition had a short but intense career in the Atlantic and Pacific, including one epic old-syle gunnery duel at Guadalcanal. USS North Carolina earned 15 battle stars and was the bodyguard of USS Enteprise, at some point the only USN aircraft carrier left in the Pacific.

An introduction

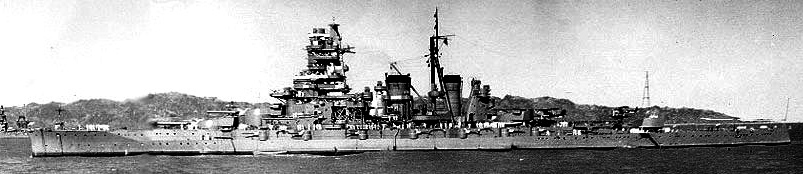

The genesis of the North Carolina class Battleships is quite an interesting one. After the end of the the great war, expanded naval construction programs bumged a considerable way, and the US’ 1916 program called for six Lexington-class battlecruisers and plus South Dakota-class battleships. However by December 1918, Woodrow Wilson’s government asked for an additional ten battleships and six battlecruisers. The General Board proposed on its side two battleships and a battlecruiser for FY1921, plus three battleships, a battlecruiser, four aircraft carriers and thirty destroyers in FY 1922 and 1924. The UK was planning the G3 battlecruisers, N3-class battleships, while Japan was busy laying the keels of Nagato, Tosa, Amagi, Kii and Number 13 classes, with the last class started in 1928.

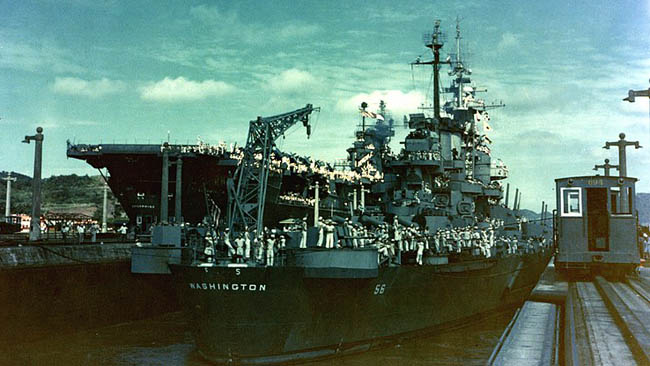

USS Washington in Septemer 1945, colorized by irootoko Jr.

However these staggering costs pushed Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes to invited delegations from the major maritime powers in Washington, D.C. to end the current naval arms races. The 1922 Washington Naval Treaty provisioned a standard displacement for battleships of 35,000 long tons (36,000 t), maximum gun caliber of 16-inch, and geeral tonnage limitations. The five concerned naval powers would have to acccept a construction holiday of ten years with no replacement for ships not aged at least twenty years old. The 1936 Second London Naval Treaty restricted gun size on new warships to 14-inch, and both influenced the design of the North Carolina class.

C&R early designs (1916-1920)

Paper battleships cost little to the US Taxpayers. And thus, even though the treaties were still running there were plenty of planned battleships, as refreshers, to just keep the pace of technological developments, but in a vacuum as if new constructions were rare (the Nelsons were completed in 1926, and the Dunkerque started in 1931), at least reconstruction -framed within the treaty limits- permitted to update older designs, for not loosing the design skills required in case this construction ban would be lifted. So there are bsically two phases: Prior to London treaty, and after.

In reality however, engineers in the 1920s started with a design they knew: The cancelled North Dakota class. Also in between, the new class of heavy cruisers authorized by Washington were seen as an “interim” serie replacing capital ships in less essential roles. They allowed, all along the 1920-1930s engineers to stay sharp in updated designs, knowing that it was always possible to add an heavier artillery and armor on a beamier, larger heavy cruiser to essentially create a modern battleship. So the “long” vacancy from 1920 (FY 1925 designs) to the North Carolinas development start (summer 1935) on paper lasted for 11 years but in reality C&R and BuEng (Bureau of Construction & Repair and Bureau of Engineers) worked on intermediate designs.

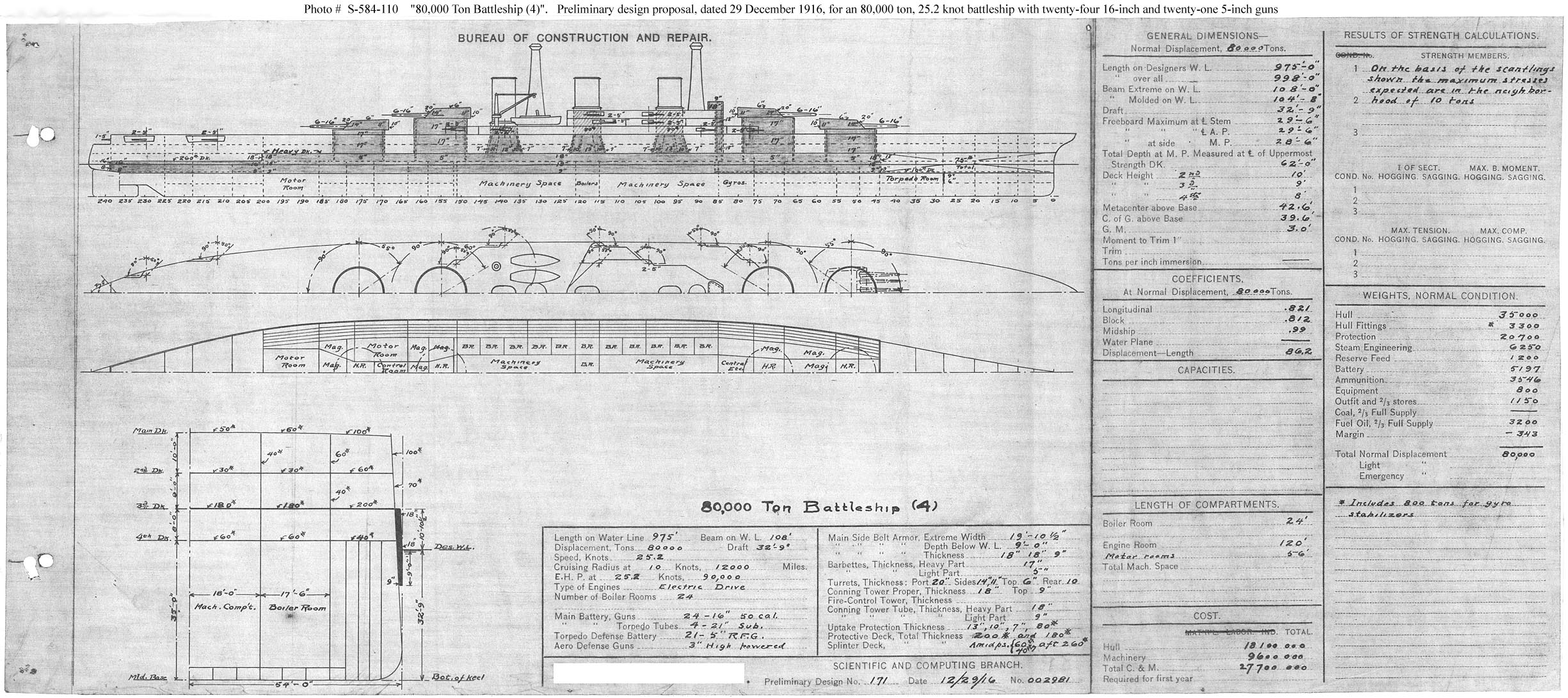

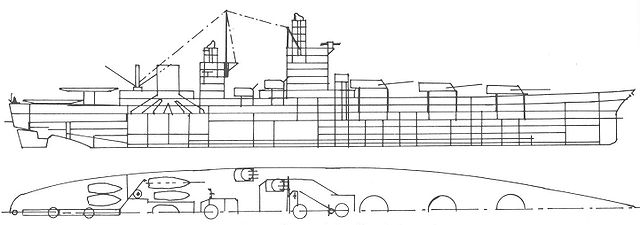

80,000 tonnes battleship design 4, 29 Dec. 1916 preliminary proposal to be authorized FY 1922-24. It was given twenty-four 16-in guns located in six-gun turrets… and was able to reach 25 knots, with an armor thickness of 18-20 inches… No wonder politicians for the time, at the behalf of their taxpayers electors, had to stop the arms race.

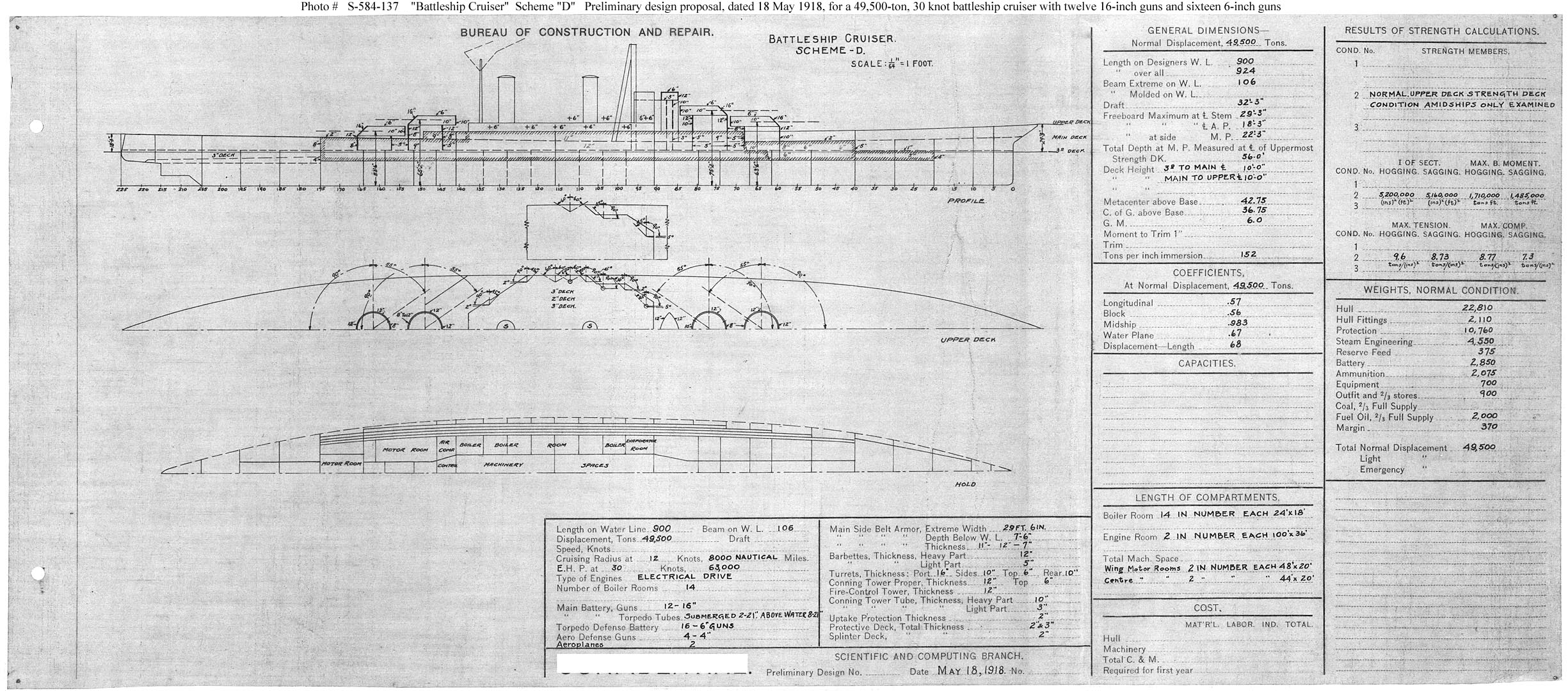

An interesting early 49,500 tonnes “battleship cruiser” that we can traduce as the earliest attempt by C&R to design a fast battleship (18 May 1918). Four triple turret with 16-in guns and 30 knots, max armor 12 inches.

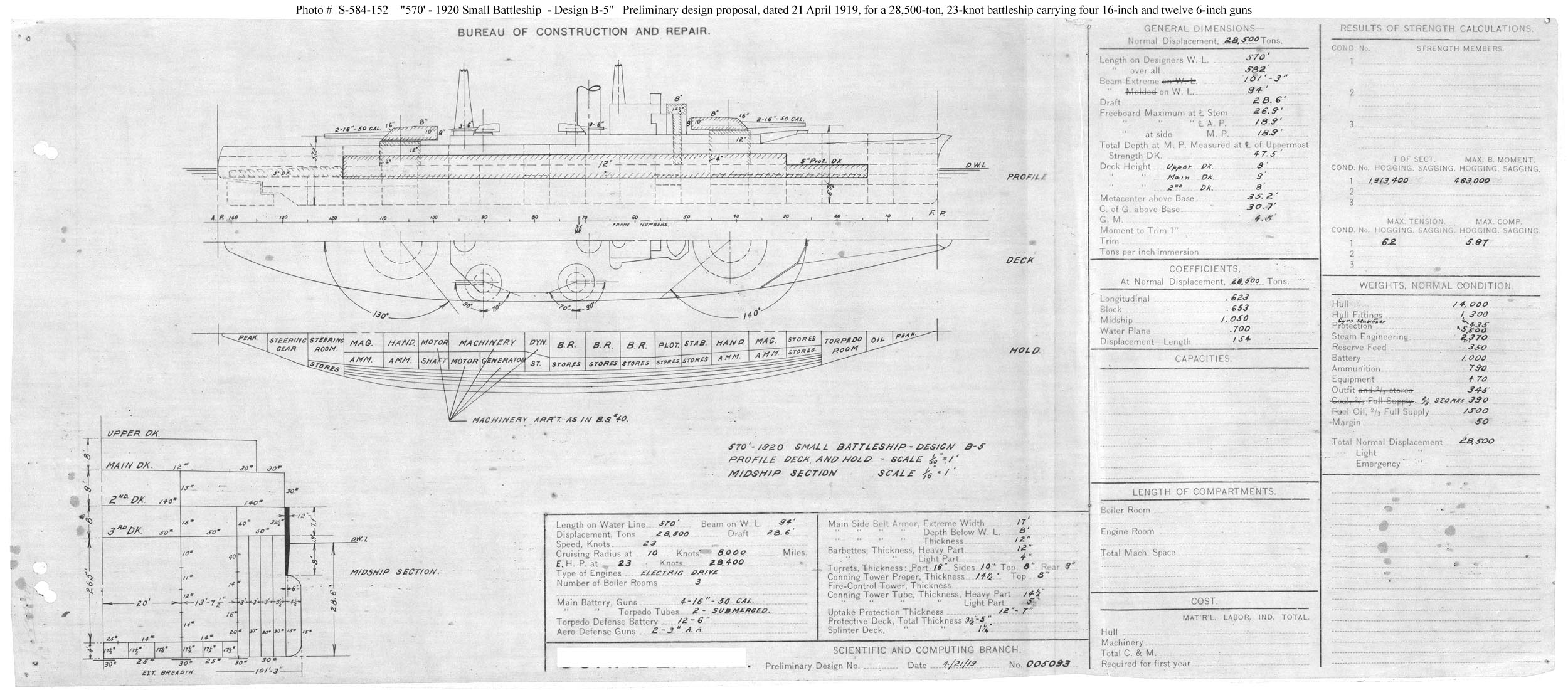

A bit later, 21 April 1919 and at the complete opposite side of the spectrum, the design B5 ‘570’ FY1920 small BB design, 28,500 tonnes with just four 16-in guns and 28 knots. This was a peacetime, coastal defence but high seas battleship. Probably a last-ditch attempt to avoid a treaty ban, looking way more reasonable to the congress.

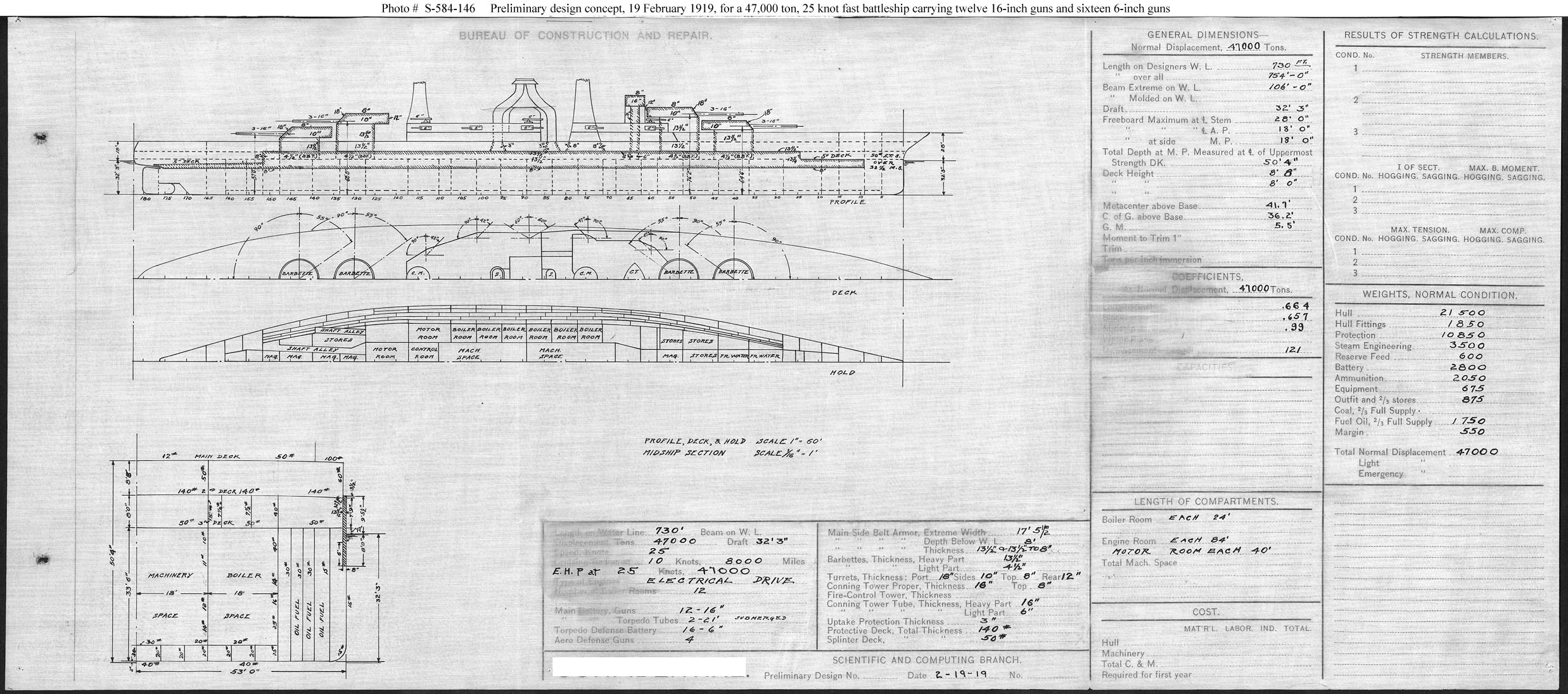

47,000 tonnes 1919 fast BB design, preliminary concept later refined into the North Dakota class. A more reasonable take which was eventually cancelled by the treaty. Based on this, C&R at least had a basic template so start again in August 1933, at the supposed end of the ban. It was in fact prolongated at London to December 31, 1936.

Post-treaty Context (1926-1936)

In the ten years before the expiration of the Washington Treaty, so from 1926 to 1936, it was realized that Italy, Japan, but also Germany were advancing ambitious construction programs. Japan eventually withdrawn at the end of 1934, so promptly taking the veil of secrecy regarding her programs, creating a sense of growing paranoia amongst British and American analysts.

Post-ban designs (1935-39)

The General Board asked for a new battleship design in May–July 1935. Three design studies were submitted:

Design “A”: It was a 32,250-long-ton (32,770 t) proposal and one of the best known as it was so different than the “final product”, more compatrable to the British Nelsons and G3. Unlike “B” and “C” this had a fair margin below the treaty limit, so allowing for duture upgrades, something the admiralty board appreciated (for good reasons looking at the cruisers). It would have carried nine 14-inch guns, all forward and a tall bridge tower. The all firing forward solution was a response to the “bar the T” tactic and popular to keep a short citadel, sparing weight. Elevation was 4.5 degrees and the secondary battery comprised twelve 5-inch (127 mm) in triple mounts, which recalled the Repulse design of 1917. The two others were more balanced and slighty faster, but also beyond treaty limits:

>”A”: 32,150 long tons (32,670 t), nine 14-inch (356 mm) guns (3×3) all forward, 30–knots, 14-in armor

>”B”: 36,000 long tons (37,000 t), 30.5 knots 14 in prot. 12x 14-inch guns (3×3)

>”C”: 36,000 long tons (37,000 t), 30.5 knots 8x 16-inch/45-caliber (4×2)

The Bureau of Ordnance announced is choice of the new “super-heavy” 16-inch shell and all three designs evolved to take in account the larger guns, so they were renamed “A1”, “B1” and “C1”. “A1” was just 500 long tons below the 35,000-ton limit, the two other reached 40,000 long tons.

Named “fast battleships” by the General Board, their speed and adjustment variable. The Naval War College was also consulted, and suggested 23-knot, something they mastered well in tehri war games and allowing them to remain compatible with older standard super dreadnoughts. Five more design studies were proposed with smaller machinery until September 1935. Speed started at 23 and went up to 30.5 knots, and the main armament started with eight, nine 14 inch or 16-inch guns for a standard displacement between 32,000 and 41,100 t, so beyond the treaty limit.

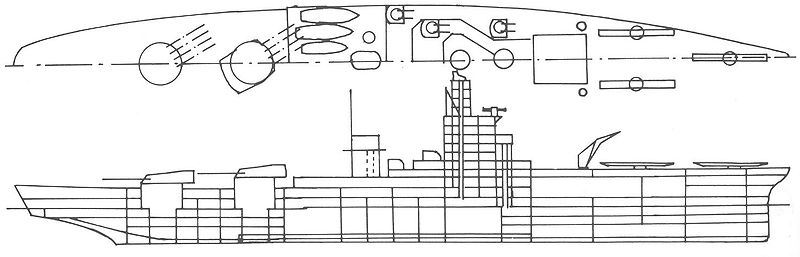

Scheme F: Eight main guns in quad turrets aft, hybrid seaplane carrier forward. It was an attempt to create a viable aircraft carrier/battleship hybrid, still well under the treaty limits with a standard displacement of 31,750 long tons (32,260 t). Three catapults wxere completed by while a hangar located under the lanching deck, and containing ten seaplane bombers, wings folded. Two aft turrets carried 14-in guns.

The “D” and “E” designs were true ‘fast battleships’ with a main 16-inch battery. Design “F” however was an oddball, a radical hybrid recallling the old British Furious when transitioning in 1917, and it was reportedly favoured by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. However the airmen section of the admiralty board estimated these catapult-launched seaplanes would necessarily be inferior to any land-based equivalents due to their floats to be retrieved at sea. The project resurfaced later wih the Kearsage concept.

Scheme VII and its 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h) was just one knot faster than the “standard” battleships and what was gained for a smaller powerplant allowed to reinforced both firepower and protection with twelve 14-inch/50 in four triple turrets and an immune zone proof against 14-inch gun between 21,400 and 30,000 yards, so close to max range as it was believed were ideal in battle.

Designs “G” and “H” showed a return to 23-knot standard of 1919, and with nine 14-inch guns in triple turrets. “H” by C&R seemed better balanced, but the General Board in the end favored faster types designs. With 35,000 tons, two finalized designs emerged, a modified “A1” capable of 30 knots but more lightly armored, or a slower one with better protection and heavier guns. Five more studies were presented in October, all with 14-inch guns and close to 30-30.5 knots. Four turrets, little armor. “K” design managed to have a 15-inch (380 mm) belt, a 5.25-inch (133 mm) deck and 17–27 km citadel immune zone against 14-inch shell. Naval constructors pushed for this one, a formula they mastered, and it respected the treaty 35,000 tons limit, but with no margin for future upgrades, which the admiralty resisted. “L” and “M” tried to save weight by using three quadruple like French designs three turrets, so twelve 14-in guns.

Designers soon realized how hard it was to deliver a potent design based on 35,000 tons standard. For 30 knots ideally as desired, armor and armament should be sacrified. A lower speed allowed for heavier guns, but still inadequate protection against the latest 16-inch shells. One solution was to concentrate artillery on a reduced lenght to fit a smaller citadel, like the numerous all guns forward projects of the time, a la Nelson or Dunkerque.

The Preliminary Design section five of October 1935 eventually settled on “A”, looking for additional armor and a smaller “B” with 14-inch guns, 30 knots, four turrets. Officers in the admiralty board wanted in addition not a single or two ships for incremental innovations, but four to match the rebuilt fast Japanese Kongō class.

The Secretary of the Navy at the time agreed, as was the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William Standley and even the president of the Naval War College Admiral William S. Pye. Still a few active senior officers and line officers engaged in strategic planning (War Plans Division), one even believing these Kongos could be dealt with aviation, and preparing airfields for heavy bombers on strategic islands like Wake was a prerequisite. The General Board eventually in late October 1935 selected “K” for further development.

The question of Japanese warships

The Admiralty Board discussing the design informally voiced construction of battlecruisers for carrier escorts, also to oppose the IJN Kongō class. Admiral William Standley, and also the president of the Naval War College Admiral William S. Pye, both respected figures, plus senior officers and line officers engaged in strategic planning also approved this, although a few argued that an aerial attack could be a solution also against the Kongōs. The General Board selected eventually settled on the “K” design as a base for further developments, of which resulted the North Carolina class battleships. In the next part of this study we will focus on other aspects of USN Battleship designs.

As a signatory to the Washington treaty Japan was nevertheless required to report all details of her new construction programs, including their displacement, armament as well as armour scheme and propulsion details. However the latter choose secrecy instead and the sens of dread that emerged from this, was to give birth to the most wildtest rumors, notably those of 16-inch or greater guns and super battleships. Also it was known that they were turning Truk attoll into a super base, the “Gibraltar of the Pacific”, able to support the whle fleet and well defended between fortifications and airfields.

In January 1938, the British Ambassador made an official inquiry if Japan was involved in a project above 35,000 tons, but met a brickwall. Indeed under previous provisions Japan was now no longer required to do transmit any information, after they withdrawn from it. By December 1938, the Japanese Navy Minister, M. Yonei, declared after all this pressure that there was no “ship of 40,000 or 45,000 tons” laid down as suggested by western intelligence. Which was of course fals as the Japanese already worked on the Yamato class, planned to be 60,000 tons, so twice as large…

The quest for a perfect hull ratio

Artist impression, USS North Carolina

Back to the US in 1935, empirical researched looked to predict maximum possible speed using the length-to-speed ratio. This figure was at first developed for 12 m race yachts, and the formula was speed = √1.408 (waterline length). There was nio computing power to back up this data, and so design speed estimates were based on model studies based on various hull forms in testing pools, and large model propellers, or self-propelled models, with the scaling up of model performance was not straight forward. Fluid dynamic was a still extremely difficult field of research, and he water behavious and viscosity at larger scale differed notably due salinity, temperature, and the gravitational field, and cannot deduced accurately from model ship basin tests.

The models were understood as to be large enough to generate a comparable flow around the hull, in order to calculate drag. For capital ships, model hulls exceeding 20-feet long were necessary, notably to generate Reynold’s Coefficients in excess of 2000, boundary between laminar and turbulent flow.

The question of propeller cavitation

It was also apparent that propeller cavitation was a very important consideration beyond 30 knots. Propeller design became another field of experiment and its importance only grew as iits efficiency falls off drastically beyond a certain speed, not only of its own revolutions, but the nature of turbulent water surrounding the propeller itself. A badly calculated shape would result in propeller damage or destruction. Shape, but also the material used (bronze casting in that case) had their importance.

Tests in 1935-37 proved the prediction of high speed propeller cavitation was less intense that initially predicted, and attention focused now on propellers tests. Destroyers for this prove ideal, as large models for capital ships, and for example in 1938 the 1500-ton USS MAURY (DD-401) tested a new propeller, stripped of everything, and with its powerplant boosted to 52,000 shp, reaching 42.8 knots off San Francisco, which was unheard of at the time for an USN destroyer (this was routine for the French and Italians already, even for cruisers).

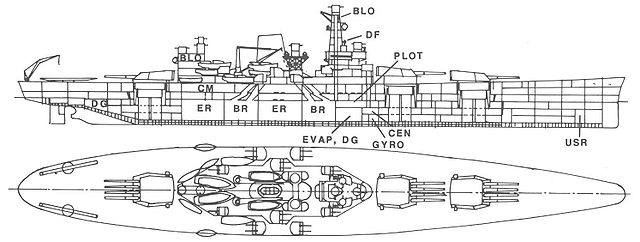

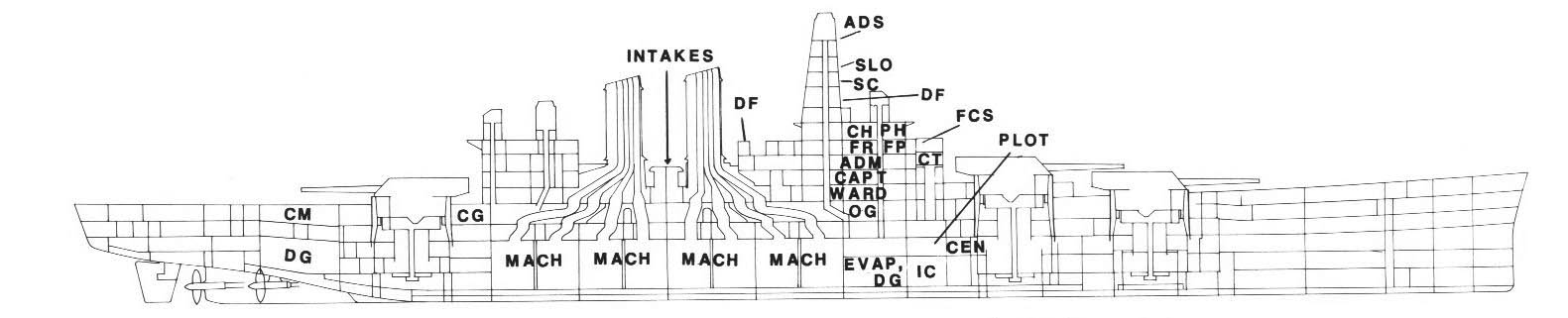

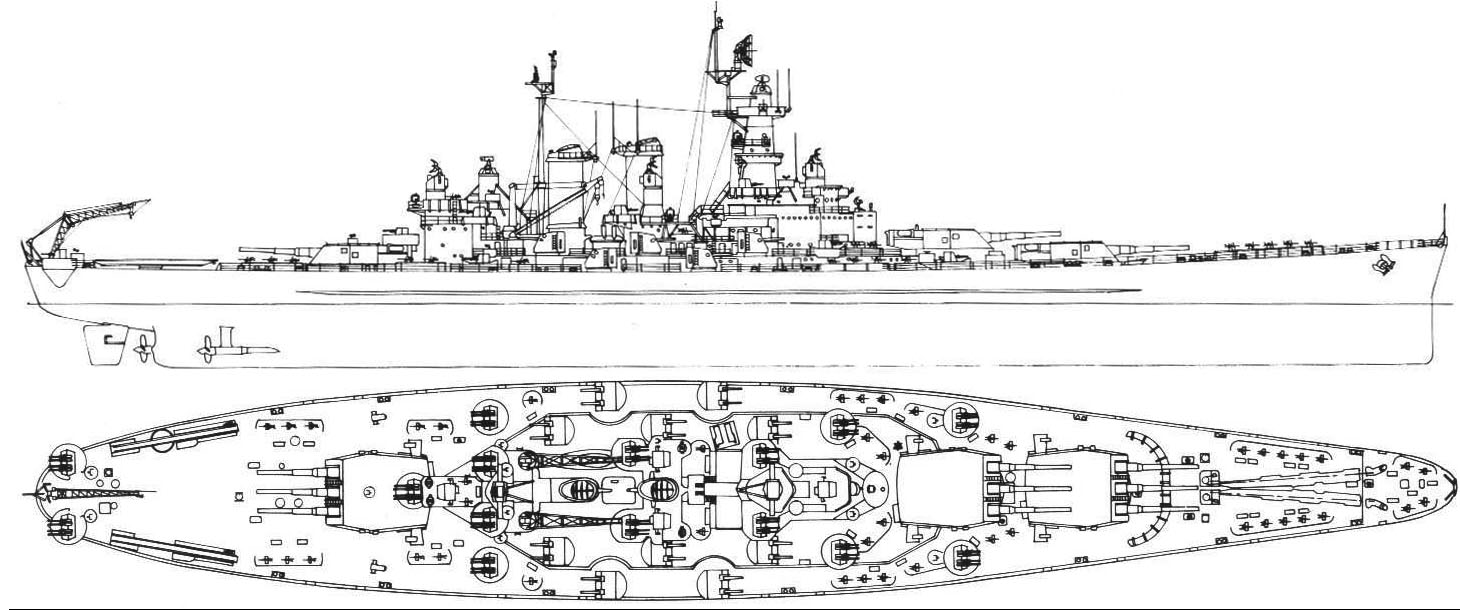

INI Recoignition drawings of the class

Hull shapes also evolved, during the interwar and blisters were added (as shown by British practice since 1916) to stop torpedo damage, as well as the introduction of triple bottoms against mines (until the, partial double bottoms were the norm). Conversion to oil-fired boilers meant also additional fuel could be carried in these new protective blisters and outer hull, playing both an extra protection role (heavy marine fuel was proven excellent to absorb a torpedo blast), and allowing more range as well.

The British Queen Elizabeth and Revenge classes showed blister additions up to 13.1 feet and several models tested to not try to diminish too much the initially more favourable length-to-beam ratio which could cost 2 knots. HMS RENOWN, bilstered, was able to reach and sustain 29 knots after a complete refit in 1936-39 and convertion fuel oil. This allowed to create narrower bulges while still providing 40% range increase. The US naval attaché in London was well aware of this, and BuEng/C&R were all given reports of these points to work from. The idea emerged soon that these bulges were later external additions, but to maximize hydrodynamic efficiency, they needed to be incorporated in a refined hull design from the start. Hull shapes had to evolve as to take in accont thes incompressible greater beams, with the upper limit of the Panama canal gates. Battleships were slow by nature, and until 1935, they obeyed hydrodynamic principles associated with a top speed not beyond 25 knots (as shown on the Nelson class).

The case of Saratoga

To better appreciate sustained speed beyond this limit, experiments were conducted on capital ships in 1933-34 and USS SARATOGA, just converted as a fleet carrier, successfully transited from San Pedro in California to Pearl

Harbor at 33.4 knots on average based on a sustained 212,000 shp output (180,000 shp as designed). She was also able to reach 35.6 knots for over 16 hours, figures that are still world records, even later exceeded on the same route on 7-10 December 1941 with 218,000 shp. But there was a catch: Saratoga was designed initially as a battlecruiser, so having already a favourable lenght-to-width ratio. She was redesigned and lightened even more, while still having the capacity for a voluminous fuel storage. She became the only ship of that size worldwide to effectively outrun her escortind destroyers on short bursts, with several times the endurance.

Some in the admiralty boad wanted badly to capitalize on these gain and looked at this class as the possibility of designing stupendously fast capital ships, even with added armpur and heavy artillery. Tests on model hulls beyond 20 feet were performed at the David Taylor Ship Model Basin which eventually in 1937 gave the updated ideal speed ratio as Capital ship speed = 1.19 √length at waterline.

Consequences of the London Naval Treaty (1936)

As the clock ran out on the Washington Naval Treaty, liberal factions in the United States and Great Britain moved to replace it with a new agreement. Conservatives dissented, pointing out the ambitious building programs of Japan, Germany, and Italy which were turning out warships of the latest and most modern design. The liberal factions won out for the time being, leading to the Naval Treaty of London which was ratified on 26 March 1936 (signed only by Britain, France, and the United States). The Washington Treaty “maximums” of 35,000 tons and 16-inch main caliber were retained, as before. The only additional limitation was that aimed at the German’s pocket battleships by limiting cruisers to 8000 tons and 10-inch main caliber (the Deutschland Class pocket battleships then under construction carried 11-inch rifles). The London Naval Treaty came into force on 1 January 1937 and was intended to run until 31 December 1942.

The treaty ratification came as a significant “setback” for political conservatives pointing to what they felt was a rapidly eroding numerical advantage enjoyed by the Anglo alliance. When taken together, the Axis threat could engage either Great Britain or the United States on fairly equal terms. From 1934 onwards, U.S. naval planners went ahead with designs for “super battleships” of 45,000 tons in response to the Japanese pull-out from the Washington accord. The London Naval Treaty, therefore, had been a great setback in light of the intelligence information being gathered at the time (6). Construction of the colossal YAMOTO Class battleships was known within the higher echelons of the Navy Department, but could not be made public.

Finalization of the design (1936-37)

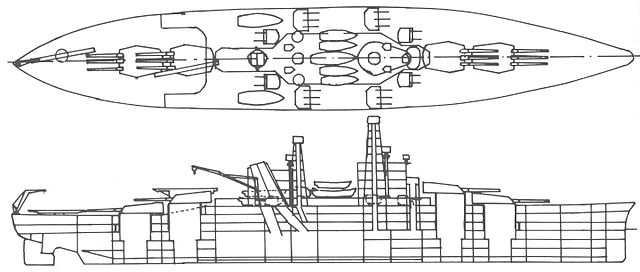

With 35 final designs proposed and discussed, numbered with Roman numerals and added letters, from I to XVI-D, they started to integrate “paper” reduction voluntarily ignoring some added wights not clearly entering the definition of standard displacement. These five designs were completed on 15 November 1935. The base requirement was to provide at least storage room for 100 shells per main battery gun and extra 100 rounds not figured in the treaty-mandated limit. Playing also with the ASW void spaces versus standard fuel tanks capacity, tap water, food, was also looked upon to “scratch any pound possible”.

These final designs all were about 35,000 long tons. Five of these designs went below 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), down to 26.5 knots, and even with the design “VII” only 22 knots (based on 50,000 shp and a 640 ft/200 m max hull) for the gain of twelve 14-inch guns in triple turrets and a better protection against 16-in guns. The usual size however was rather 710 ft (220 m) up to 725 ft (221 m), so closer to the final design, and 27 knots. Gun mountings also included variations from eight, to twelve 14-inch guns, including in quadruple turrets and at last one with two quadruple 16-inch gun turrets.

Scheme XVI, back to the old trusted formula of four triples. Few major differences in the blueprints drafted later included all exhaust trunked into two funnels as opposed to one and 5-inch/38 caliber secondaries in dual turrets.

Design “XVI” 27-knot, 714 ft (218 m) long hull proposal, submitted on 20 August 1936, still had twelve 14-inch guns but a weak 11.2-inch (284.5 mm) belt and was opposed by the Bureau of Ordnance based on high speeds hull model testings showing inadequate protection in parts neither covered by water or armor. Especially above the shell and charges magazines which was extremely problematic in the classic 20,000-30,000 yd (9.9 and 14.8 nmi; 18 and 27 km) defined immune zone area. Advances in aerial bombs also doomed the ship due to its weak deck protection. BuOrd asked to review the formula used to calculate the armor effectiveness as unrealistic. It was discussed to add notably patches of armor around the magazines and deepening the belt near the bow and stern to compensate for the excessive tapering down or absence of armor, still to be kept within the the 35,000 long ton limit. The General Board ruled it out in the end.

In October 1936 Design XVI-B, C and D were further refinements of the “XVI” design proposal. With an extra 11 feet (3.4 m) of hull lenght for greater speed, and eleven 14-inch guns, 10.1-inch (260 mm) belt, the second with ten guns, but a 13.5-inch (342.9 mm) armor belt, and the third, “C” scratched an extra knot for 1/10 inch extra belt thickness. The General Board eventually wettled without surprise on “XVI-C” which as thought had the ideally best-in-weak protection level and more properl fitted with the clasic “standard” battleships in battle line but still be detached to operate with aircraft carriers and commerce raiding groups wit cruisers.

C&R team at work, 1937 (navsource)

Admiral Joseph Reeves in charge of the USN aircraft carrier strategy expressed however his concerns that “XVI-C” was still too slow to escort the aicraft carriers of the Lexington class able of 33-knot (61 km/h; 38 mph). He advocated for an extra “XVI” design development with added underwater protection to spare armpur weight, plus patches of armor where it was most required, at lower range of 19,000 yd (9.4 nmi; 17 km) and beyond up to 28,200 yd, then 30,000 yd. Reeves confered with Standley, and both approved and milited for this last modified “XVI” with a switch clause from quadruple 14-inch to triple 16 in (406 mm) turrets as the “escalator clause” in the Second London Naval Treaty was discussed at that time. Later in 1937, an increase in armor was found by finding more on-paper weight savings, which included a belt slope to 13° and then 15° and the perfect alternated propulsion machinery layout which maximized ASW protection.

The The Escalator Clause The Second London Naval Treaty stuck to the 14 inches gun limit, but the US delegation obtained to add the “escalator clause” in case any country previously signator of the Washington Naval Treaty not adhering to the new London treaty limit. So according to it, France, the United Kingdom and the United States were allowed to increase to 16 inches in case Japan or Italy refused to sign the treaty on 1st April 1937. Standley’s requirement to switch to 16-inch after the ships’ keels were laid, was a hard task for engineers, which had to design from the onset, larger barbettes, guns turrets and everything in between, then planned tp fit either guns. Japan eventually as feared rejected the London Treaty limitations by official means on 27 March 1937, and te “escalator clause” was invoked. Roosevelt though was under heavy political pressure fro the congress as such upgrade not only seemed costly, but he did not wanted the US to appear starting a naval arms race, and as a result he was initially reluctant.

The second Vinson Act (1938)

The Naval Act of 1936 eventually authorized the construction of the first American battleships in 17 years, albeit at the time still under the double limit of 35,000 tons and 14-inch guns. The escalator clause was soon invoked in April 1937 but construction only started for BB-55 at New York Naval Shipyard with the keel laid down in October. This allowed plenty of time to alter the blueprints and make the necessary revisions from twelve 14-inch to nine 16-inch rifles. Neverteless, their protection could not be increased and stayed at the level of 14-in shells immunity. There was knowledge about the Japanese Nagato class.

16 months after the ratification of the new London Naval Treaty, intelligence reported Axis rapid development of new capital ships in excess of any treaty limitations, suggesting allied powers now were condemned to stick with inferior designs. Conservatives back in the U.S. toughts another war very likely and in that regard, saw the London Treaty as an hinderance. In May 1938, Republican Congressman Carl Vinson argued for what was called the “second Vinson Act”, asking for building a new fleet to increase the US fleet capital ship size of 20%.

This new Vinson Act wanted to lift in effect the London Treaty limitations. On June 30, 1938, the “sliding scale” clause was asked for as an addition to the 1936 agreement, asking to increase the maximimal authorize tonnage to 45,000 tons, a decision fuelled by Japan’s refusals to British inquiries, taken as an admission of guilt and further fed the growing allied paranoia. Mr. Yonei’s response eventually came 11 months later, far too late to prevent the Second Vinson Act to authorize this new ceiling of 45,000 tons, with six new ships ordered that would be the four SOUTH DAKOTA and first two IOWA Class, all to be soon laid down based on a modified North Carolina design. It should be noted that it was also Carl Vinson (a 1980 aircraft carrier was named after him) drafted with David Walsh the Vinson-Walsh Act enacted on July 19, 1940, raising the US fleet to “wartime level” and justifying the mass-built 18 fleet aircraft carriers (Essex class, later doubled), additional battleships (2 Iowa, 5 montana class), 33 cruisers, 115 destroyers and 43 submarines mass-built from 1941.

Detailed design (1940)

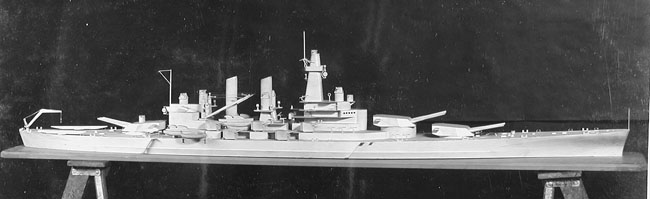

Test model of the last design

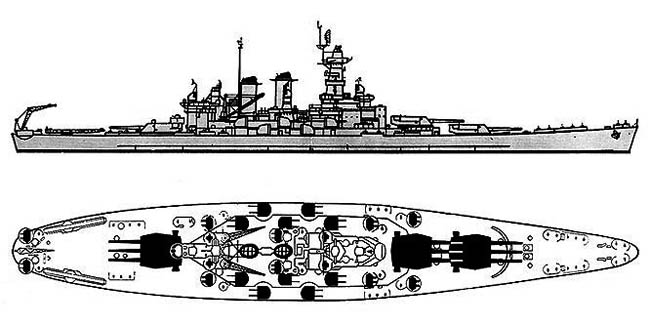

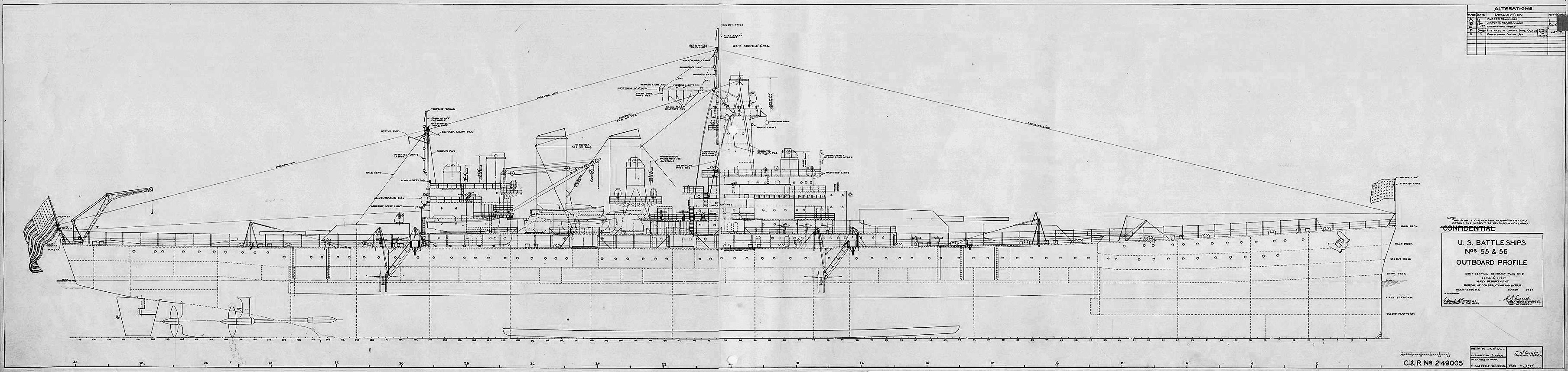

The final design, refined by the first constructor in 1936 and until late 1937, New York Naval Shipyard for the lead ship, showed a hull 713 feet 5.25 inches (217.456 m) long at the waterline, 728 feet 8.625 inches (222.113 m) overall with the largest beam at 108 feet 3.875 inches (33.017 m) but at the waterline 104 feet 6 inches (31.85 m) with the inclination downards of the armor belt. In 1942 standard displacement was rated for 36,600 long tons (37,200 t) and 44,800 long tons fully loaded (45,500 t), although declared in 1937 at 35,000 tons. Maximum draft was 35 feet 6 inches (10.82 m), but at 42,329 tons load, mean draft went to 31 feet 7.313 inches (9.635 m). The ship was large and buyoant enough to retain a good metacentric height of 8.31 feet (2.53 m). Crew complement and accomodations initially planned for 1,880, 108 officers and 1,772 ratings. In 1945 between the numerous anti-aircraft armament addition, new electronics and FCS, and flagship accommodations with a full displacement to 46,700 long tons, crew rose to 2,339: 144 officers and 2,195 enlisted, and increase of 459 than needed to be accomodated. In 1945 the ship feel cramped. Postwar, it was reduced to 1,774.

Hull construction

Their hull main feature was a bulbous bow, and an unusual stern design, both for the time. The stern was due to the location of the two inboard propulsion shafts in skegs, theorized to improve flow conditions aft, around the propellers and improved cavitation as shown by previous studies (see above). The new stern was also the result of hydrodynamic, empiric researches backed by mathematical models (see above also) with initial model basin testings, looking for the best stem configuration.

It suggested that the new skeg arrangement would reduce water resistance, but it was later infirmed during testings for the Montana-class design; It indicated in contrary, an increase in drag. However these skegs still improved structural strength there, by acting as girders, providing structural continuity for the torpedo bulkheads as well. They formed a tunnel increasingd propeller efficiency but also helped support the ship in drydock.

They also contributed lessen vibration problems that would plagued their initial commissioned service, and required extensive testing and modifications. It was acute near the aft main battery director and eventually required the fitting of additional reinforcing braces. Skegs would be improved and became the staple of next American battleships which dealt better with vibration problems, eventually eliminated entirely on the Iowa class. Needless to say, vibrations nullified any practical use of the fire controls sights at high speed. The new design also incoporated four rudders, about ten feet off centerline, and positioned abaft of the inboard propellers.

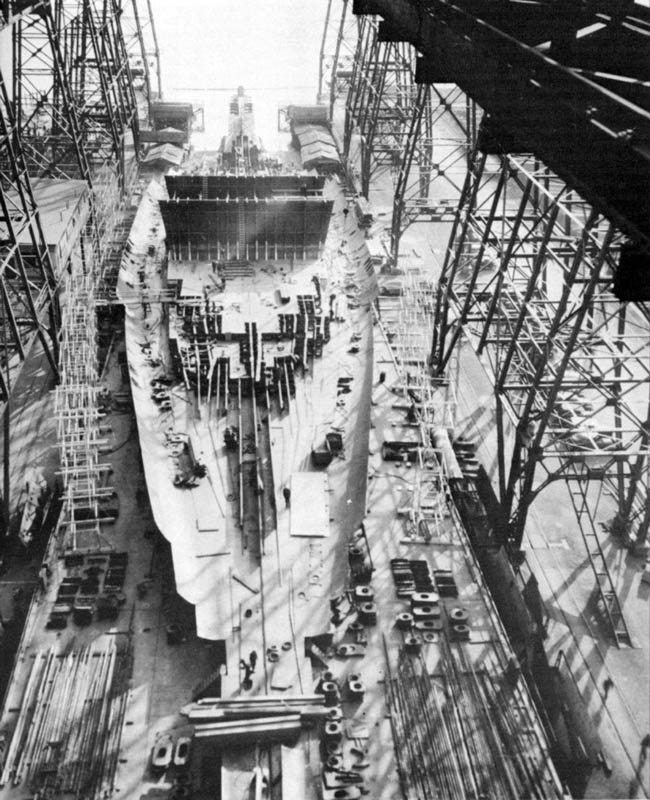

Fitting out of USS North Carolina

The bulbous bow was another innovation, also deduced from empiric models basin trials, which were needed to reduce drag and increase water penetration, necessary to mitigate the larger beam and take the best of the available power.

It was designed to reduce resistance but also increase hull efficiency by as much as 5% at high speed, and this feature was retained (and prefected in the next designs). This was also the result of the successful redesign of the Lexington class and amazing performances of the USS Saratoga. Another contemporary ship that tried it for the first time was the French liner SS Normandie, which could probably make 30 kots on 200,000 shp as opposed to 212,000 for the Queen Mary. Before that, the British already tested a “flared forefoot” with HMS Hood and the Repulse class.

The other novelty of the design, was the clear sweeping flush deck, unbroken from bow to stern, without portholes nor disgraceful recesses for casemates. As all the armament was in turrets on the battery deck, with electrical output was almost quadrupled compared to 1918-19 designs, it was all-electric lighting inside the hull, but all moving structures were also moved electrically, as the turrets and FCS, and the ballistic computer below decks. The superstructures however kept portholes, notably to spare energy. All these were radical improvements showing the long path of reflexion taken since 1926. The North Carolina design was in fact the base design, later improved on the next two classes, one with lesser speed and better armour (North Dakota), still treaty-bound, and a wartime one totally unbound, and pushing the three cursors of speed, protection and armament forward to its logical end (the Iowa class).

Powerplant

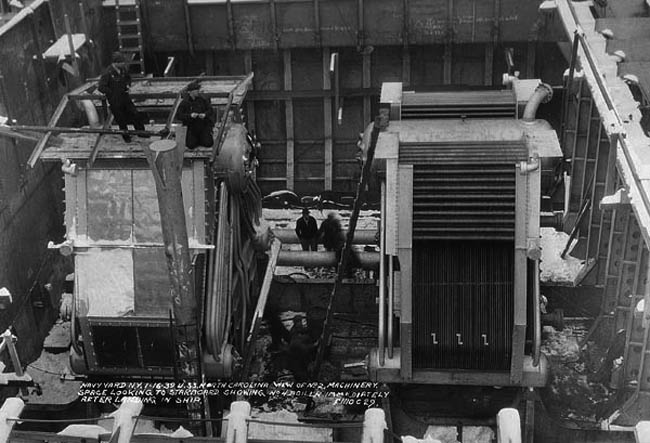

Reduction gears of USS North Carolina’s turbines (tumblr)

The the North Carolina class did not innovated much in that field, going with a refined, modernized version of the turbo-electric transmission and steam turbines fed by boilers developed for the cancelled North Dakota class. Her powerplant comprised four General Electric geared turbines fed by eight Babcock & Wilcox, three-drum express type boilers. Developments in turbine equipment were added like double helical reduction gears (photos) and high-pressure steam with injection of higher grade oil.

The boilers had a 575 psi (3,960 kPa) working pressure, amounted to 850°F (454 °C), enough to melt most metals. To reached the required 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), the total output as design was to be 115,000 shp (85,755 kW), on paper in 1936, but in between when the ship was constructed, this reached 121,000 shp (90,000 kW). The changed however only improved marhginally her performances as on sea trials, and little modifications could be done on the turbines, already installed. Higher pressure and temperature steam did not provided the efficiency awaited. Going astern (in reserve) her machinery produced 32,000 shp (24,000 kW) still, but both ships were plagues by vibration issues.

The whiole machinery was distributed among four separate engine rooms in the centerline. This helped mitigating flooding but also provided more useful room on either side for ASW protection, which was far greater than earlier vessels. Each room contained a turbine and its two boilers, undivided. This was done as if one was flooded, the others remained fully operational, as independent unit.

However these engine rooms were alternated in layout with the first and third arranged with the turbine on the starboard side and reversed in the second and fourth rooms port. The forward-most engine room powered the starboard outer shaft, the second the outer port shaft, the third, the inner starboard shafts and the fourth, the port-side inner shaft. These were four bladed bronze models, 15 ft 4 in (4.67 m) diameter for the outer pair and 16 ft 7.5 in (5.067 m) for the inner pair. Steering required a pair of rudders.

N°2 machinery space during construction

When commissioned, a top speed was reached on trials of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). Of course this was with fored heating and limited equioment. In 1945, they had been overloads with extra equipments and this went down to 26.8 knots (49.6 km/h; 30.8 mph) when testing a full run. This overload also resuced the cruising range, which went from 17,450 nautical miles (32,320 km; 20,080 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) in 1941 down to 16,320 nmi (30,220 km; 18,780 mi) in 1945. At 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) sustained, this fell to just 5,740 nmi (10,630 km; 6,610 mi). Now wonder the USN spent a great deal crating supply and workshop fleets for the pacific, thet are an often overlooked but so important aspect of the operations at sea.

Electrical power was improved several fold, provided by eight state of the art generators. Four were naval grade turbo-generators providing 1,250 kilowatts each and the other four diesel generators rated for 850 kilowatts each. Two smaller diesel generators also provided 200 kilowatts each, used for emergency power if the rest of the system were damaged, at least allowing lighting, pumps and basic systems to repair the ship. Total electrical output was 8,400 kilowatts, at 450 volts, alternating current. This power was to provide all turrets, down to AA mounts, radars, and all other sytems on board.

Armor scheme full details

General scheme:

The North Carolina class repeated the “all or nothing” armor scheme, and in its final form, stille weighed 41% of the total displacement. There was the classic “armored raft”, or central citadel extending from the first barbette, to aft of the rear gun barbette under the secondary armored deck. It used also addon plating of Special Treatment Steel (STS). The three-layer armor deck confifuration was aso an innovation: The first deck function was just explode prematurely delay-fuzed projectiles. The thicker second protect the ships’s internals and the third below protect against shell splinters that would have get through the second deck and acted as upper support for the torpedo bulkheads.

It enclosed the “raft” and protected ammunition magazines and the machinery, with additional STS provisions above the steering and these magazines. The turrets were extremely well armoured, with a 16-in face. This was even greater due to the sloping, butparabolic hits were expected. Sixteen–inches was the thickest armor that factories were able to produce at the time, in 1937. However in 1939, they upgraded the process to produce 18-inch (457 mm)-thick plates without any addition. The admiralty ruled out their installation for obvious delays in drydock from 6 to 8 months.

USS Washington under construction, 6 January 1939

An advanced ASW protection:

The side protection system was also innovative and inspired by what was done in other navies, with peculiarities. It incorporated five compartments, divided by torpedo bulkheads and augmented by a large anti-torpedo bulge, still internal and running all the way along the “armored raft”. The outer two compartments and innermost compartment plus the bulge were all designed as empty but third and fourth compartments were designed to be filled with liquid, either seawater or fuel, but the latter was of course obvious in operations.

This whole side protection was reduced in depth after the raft, on both ends forward and aft of the main barbettes. There, the fifth compartment was elmininated and instead an outer empty compartment was sandwitched between two liquid-filled spaces backed by another empty compartment, but these sections received additional 3.75-inch (95 mm) plating.

Amidship, at the greater beam, the whole underwater protection sustem was 18.5 ft (5.64 m) deep, and could withstand 700 lb (320 kg) TNT warheads. The triple bottom underneath, also new, was 5.75 ft (2 m) deep. The bottom layer 3 ft (1 m) thick was filled with fluid (oil there) for ballast, and the upper 2.75-foot (1 m) layer was kept empty. The triple bottom was also subdivided into many longitudinal and transverse sections to stop any flooding.

- Main: 12-inch (305 mm) amidships/15° inwards +19mm STS

- Lower edge: 6-inch (152 mm), no armor forward or aft.

- Main (citadel roof) 1.45-inch (37 mm)

- Battery deck 0.62-inch (16 mm)

- Citadel bottom: 3.6-inch (91 mm)+1.4-inch (36 mm) STS

- Communications tube 14-inch (356 mm)

- Sides 16 inches (406 mm), front-rear 14.7 inches (373 mm)

- Roof 7 inches (178 mm)

- Bottom 3.9 inches (99 mm)

- Main- faces: 16-inch (406 mm)

- Main- Sides: 9-inch (229 mm)

- Main- Back: 11.8-inch (300 mm)

- Main- Roof: 7-inch (178 mm)

- Main- Barbettes: 14.7/16/11.5 inches front/sides/back

- Sec. 5-in/38: 1.95-inch (50 mm) STS plating

- Internal Torpedo Bulkhead outer section 3.75-inch (95 mm)

- Triple bottom

Belt

Armored Decks

Conning Tower

Turrets

ASW protection

North Carolina overhead

North Carolina stern view

Armament

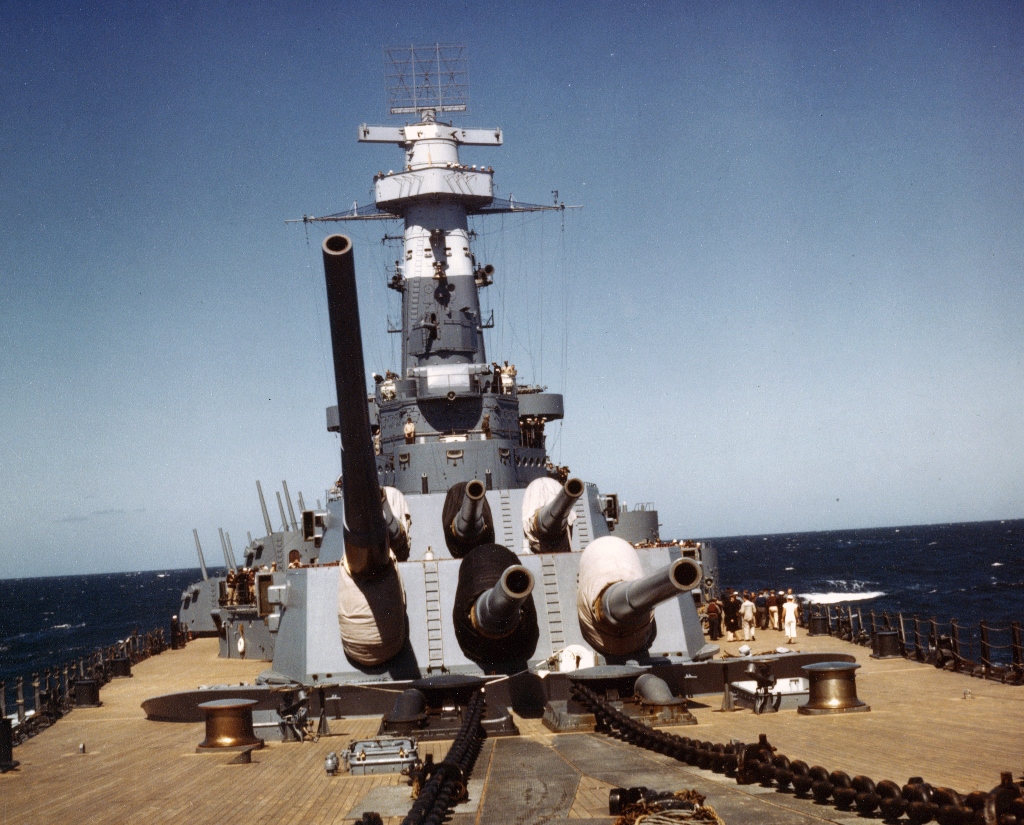

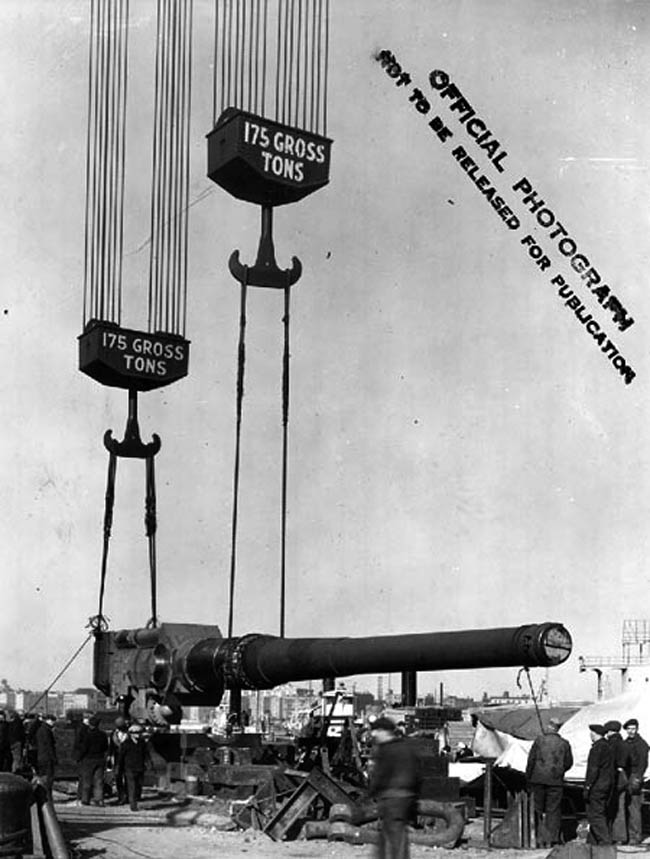

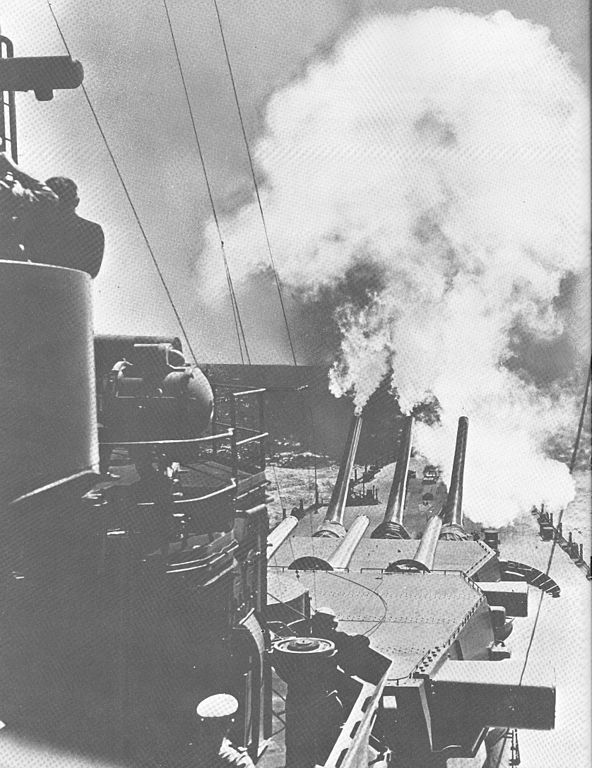

Main Guns: Nine 16-in/45 Mk6

Another important innovation were the brand new mounts and turrets that were designed from 1936 for these ships and repeated with some improvements on the next classes. They were completely identical between the North Carolina class and the South Dakota classes but diverged on the Iowa class, arguably reaching a pinnacle of the genre.

The were nine 16 inches/45 caliber (barrel lenght) or 40.6 cm, much improved versions of the Colorado-class battleships main guns developed in WW1, so they were designated Mark 6.

The interwar allowed a long process of refinement, and the Mark 6 main ability was to fire the new 2,700-pound (1,200-kilogram) armor-piercing (AP) shell developed by the Bureau of Ordnance and pushed foward by the admiralty board.

Bow view, 16-in Mark 6 color – naval historical center archive

Final installation of the same

Shells:

- AP Mark 8 2,700 lbs. (1,225 kg), 40.9 lbs. (18.55 kg) bursting charge

- HC Mark 13 1,900 lbs. (862 kg), 153.6 lbs. (69.67 kg) BC

- HC Mark 14 1,900 lbs. (862 kg), same.

Muzzle Velocity: At full charge, this new heavy shell exited the barrel at a muzzle velocity of 2,300 ft/s (700 m/s). At a reduced charge, at 1,800 ft/s (550 m/s) – like special training shells.

Barrel life was estimated 395 shells before the barrel was to be relined or replaced, and only when using the heavy charge, heavy AP shell. With practice shells this went up to 2,860.

Traverse: The brand new turret, flat and roomy, turning at 4 degrees per second, and trained 150° on either side.

Elevation: Maximal inclination was 45 degrees, depression −2 degrees, but zero for the superfiring turret.

Rate of fire: Two rounds a minute.

Barrel: 736 in (18,700 mm) long overall, 720-inch (18,000 mm) for the bore and 616.9-inch (15,670 mm) for the rifling.

Load mechanism: Welin breech block opening downwards

Maximum range: -Heavy AP shell at 45 degrees: 36,900 yd (33,700 m).

-High capacity (HC) shell1, 900-pound (860-kilogram) 40,180 yards (37 km).

16-in Mark 6 design specifics

The guns weighed 192,310 lb (87,230 kg; 86 long tons) not including the breech. It comprised an A tube, jacket, three hoops, two locking rings, liner-locking ring, yoke ring and screw box liner and some elements were autofretted. The bore was chromium plated. The chamber volume was 23,195 in3 (380.1 dm3). The primer cartridge can be fired either electrically or by percussion. The propellant charges varied per shell, with the AP, the Full Charge weighted 535 lbs. (242.7 kg), the HC reduced Charge was 295 lbs. (133.8 kg) and the Eeduced Charge Flashless weighted 315 lbs. (142.9 kg).

The manufacturer provided to modified versions during the war, in addition of the spare barrels, at least 54 spares given the two vessels, plus those of the North Dakota classes, plus two modified types: The first, called “mod 1” had tapped holes in the breech end, for securing the hinge lug to the gun. Mod 2 had a set of adapter sleeves to rebarrel the Colorado class which also needed spares and would take advantage of the new AP shell. However in all, “only” 120 guns of all mods were manufactured, so the 54 original guns, 54 spares and 18 mod 2 versions or extra spares.

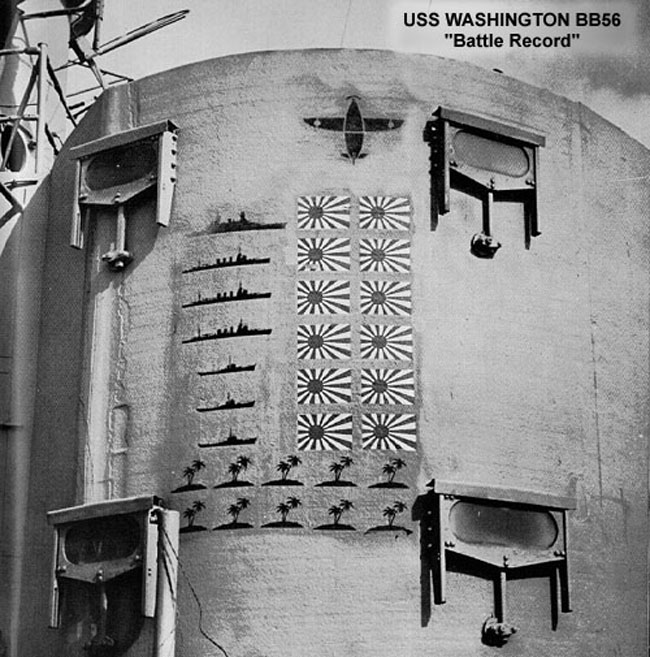

Performances of the 16-in Mark 6

With the AP 16-inch/45 Mark 6, notably compared to 50 caliber Mk.7 was for a slower velocity shell with a steeper trajectory and at 35,000 yards (32 km), it would strike a plate at an angle of 45.2° as opposed to 36° with the 50 caliber, giving it an edge in deck armor penetration. Pitted against other capital ships, we have the example of the Battle off Casablanca in November 1942, when USS Massachusetts (BB-59) pierced the deck armor of the French battleship Jean Bart and her main battery turret. At the Battle of Guadalcanal, USS Washington (BB-56) sank IJN Kirishima with at least nine direct AP hits since it was at short range, in near flat trajectories.

Turret specifics

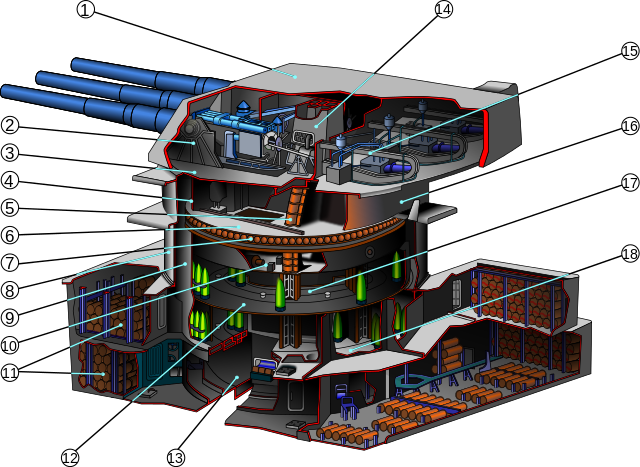

Colored and redrawn version of the ONI cutaway, Iowa class turret. (cc)

The turret weighed slightly over 3,100,000 lb (1,406,136 kg; 1,384 long tons). It had its theoretical 360° traverse stopped automatically on her bearings to avoid firing by accident in the superstructure or any other obstacle. The gun crew accessed from an hatch below the turret, through the gun deck. There was enough room inside for am emergency medical care kit, gas masks, electric communication and control panel, backup communication tubes, and even a basic backup sight. All three guns were separated by internal bulkheads installed in between the deck lug on the girder, but still open aft to circulate between the rammer and back of the turret.

Turret installation, USS Washington

Bewow the gun girder was located the primary well of the barbette, with the inner rotating structure and projectile hoists, with a plan floor resting on a roller path with ball bearings, the internal support barbette below, the stationary fondation, projectile ring, machinery floor and below, the loading chamber, with the powder handling room. In total, this represented the equivalent of a generous five stories tall building. The turret and its barbette and loading mechanism weighted as much as a late WW2 Sumner class destroyer (2,250 tonnes). There were 47 men inside each gunhouse alone, so nearly 150, not counting those affected to the loading below of the shells and charges making for a total of 177. The total number of those in charge for the main guns, even excluding those affected to ballistic duties (spotters, telemeter pointers, speakers, data transmitters, plotting room officers, computer servants, etc.) those three guns represented almost one third of the crew alone.

Secondary Guns: Twenty 5-in/38

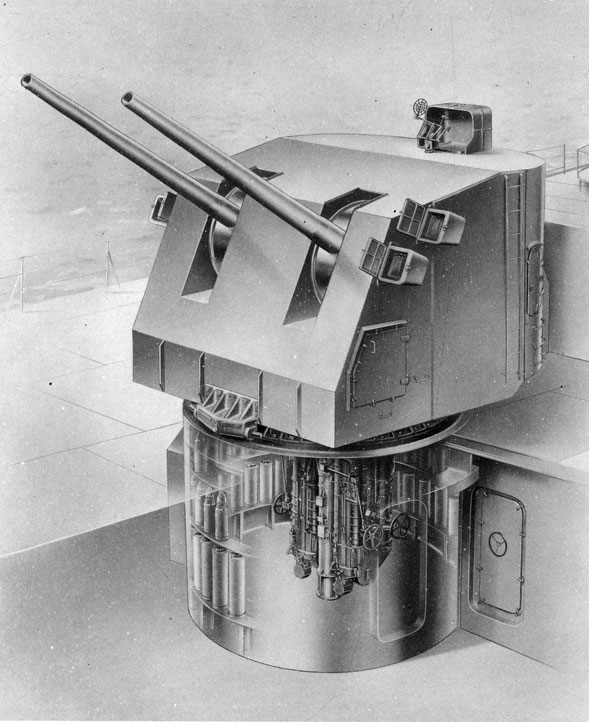

ONI 5-in/38 turret

The ten Mark 28 Mod 0 turrets ith their enclosed base ring mounts supporting twin Mark 12 guns were plced as follows: Two on deck level amidships and three on the battery deck alternated, on either side, so ten turrets in all for twenty guns, all independent. Probably the best ordnance piece of equipment on the allied side, and credited as such by admirals in their role especially at the end of WW2 with the level of Kamikaze attacks, these famous weapons systems were taking advantage of the standard 5-inches (127 mm) classic gun caliber used by the USN since even before the dreadnought age.

These new ones were initially designed to be mounted on destroyers the new 1930s destroyers. Read More: 123

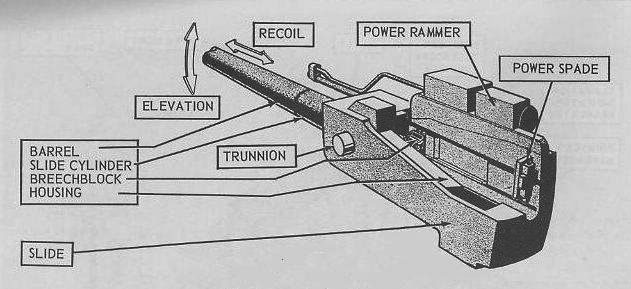

Gun assembly (ONI, cc)

But it soon appeared so successful that a myriad of US ships received them, in fact from destroyers to cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers until 1945. “highly reliable, robust and accurate” they were the perfect dual purpose guns, as their anti-air abilities established in 1941 gunnery tests on board North Carolina proved an amazing accuracy agains fast flying tarets up to 12,000–13,000 feet (3.7–4.0 km) twice as far as the older 5-inch/25 AA model used so far. Fuses shells soon also added a great bonus, and later in WW2, progresses in radar-assisted guidance made them supremely deadly. It’s not at random they were still active on modernized FRAM destroyers in the 1990s around the world… This installation in a “W” pattern not only was convernient to give them the best arc of fire, but also ensured no inteference with other systems, helped with the broad beam at this point.

Quickspecs:

-Guns Weight 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) without breech.

-Mount weight 156,295 pounds (70,894 kg).

-223.8 in (5,680 mm) long overall

-Bore length 190 in (4,800 mm)

-Rifling length 157.2 in (3,990 mm).

-Muzzle velocity 2,500–2,600 ft/s (760–790 m/s)

-Barrel life 4,600 rounds

-Depression/Elevation −15 and 85° at 15° per second.

−Traverse 150-150° on either side for battery guns (with interruptor gear)

−Traverse 80-80 degrees for deck turrets, both at 25°/sec.

-Rate of fire as designed 15 rpm

-Vertical sliding-wedge with 15 in (38 cm) recoil

-127×680mmR 53-55 lb (24-25 kg) shell

AA Guns: Forty 40mm/70 *1943

It is important to note before they were installed, but only from September 1942 when USS North Carolina, torpedoed at Guadalcanal, was under repairs in Pearl Harbor. Her original suite was of just four quadruple 1.1 inches (the infamous “28 mm chicago piano”).

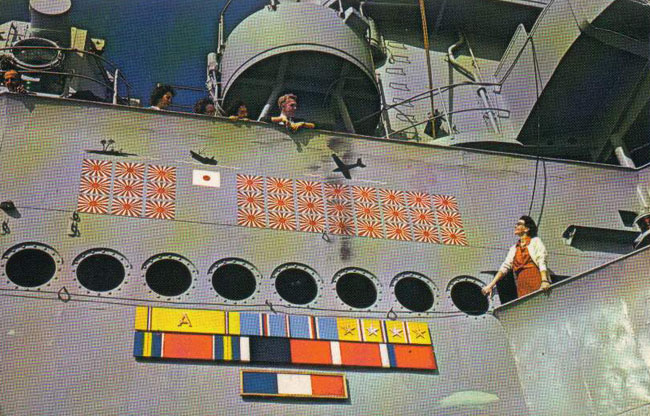

On both vessels, two additional quadruple 1.1 in mounts were added, in place of the two searchlights amidships when the war broke out. USS North Carolina had all these removed, ten quadruple 40 mm guns installed in place, and fourteen by June 1943, fifteen (on the roof of the third main turret in November 1943).

USS Washington amazingly still had her six 1.1 in quads until mid-1943, and like her sister ship, ten quad 40 mm guns were installed and fifteen in August 1943, so 60 Bofors in all. Each mount needed a crew of seven, so 105 in all.

40 mm mounts overhead

40 mm quad mounts at the stern

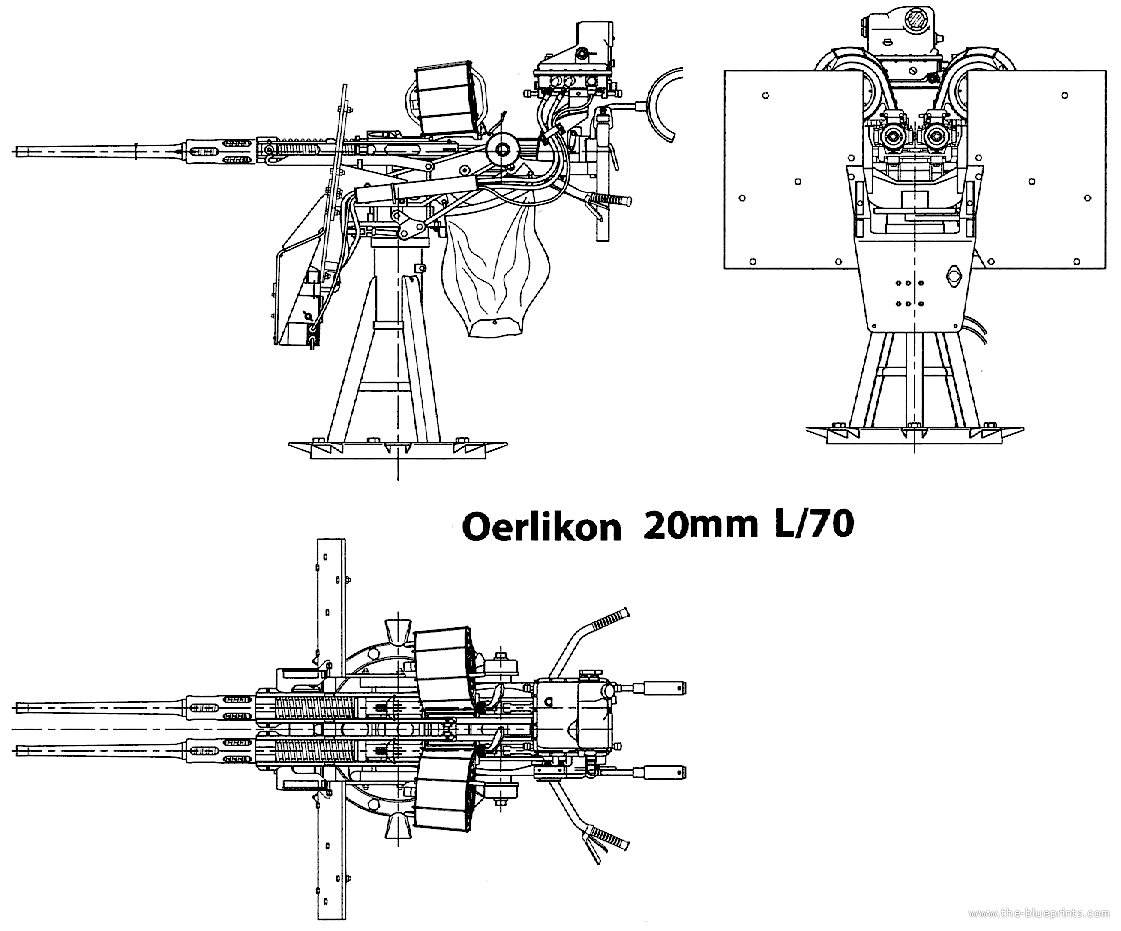

AA Guns: Forty 20mm/70 *1943

-Before the Oerlikons were installed, USS North Carolina carried twelve .05 cal./90 Browning M2 heavy machine guns in single tripod mounts along the decks, in positions later occupied by the Oerlikons. These derived from the Model 1921, modified to preduce the M2 in 1932. Appreciated for thei high rate of fire, their range was limited to 5,000 feet (1,524 m) for the effective range, but it went to 15,000 feet (4,570 m) in “spray and prey” mode. Needless to say these were removed and replaced by Oerlikons, but this went with a catch: The M2 could be operated by a single man, assisted by a reloader in case, while the Oerlikon needed three. This went with changed in accomodations.

-In 1942, the 20 mm were placed as follows: Two unprotected, then six protected along the anchor chains at the bow, six along the superfiring B turret, six on the forward battery deck, then four (unprotected), four protected, and six protected at the angular end of the battery deck, three over turret C, and abreast, two unprotected at gun barrel end level, and four unprotected at the stern. They were forty in 1945, twenty of the Mk24 and twenty of the Mk10.

Twin 20 mm mount

Single 20 mm mount

Fire Control & Electronics

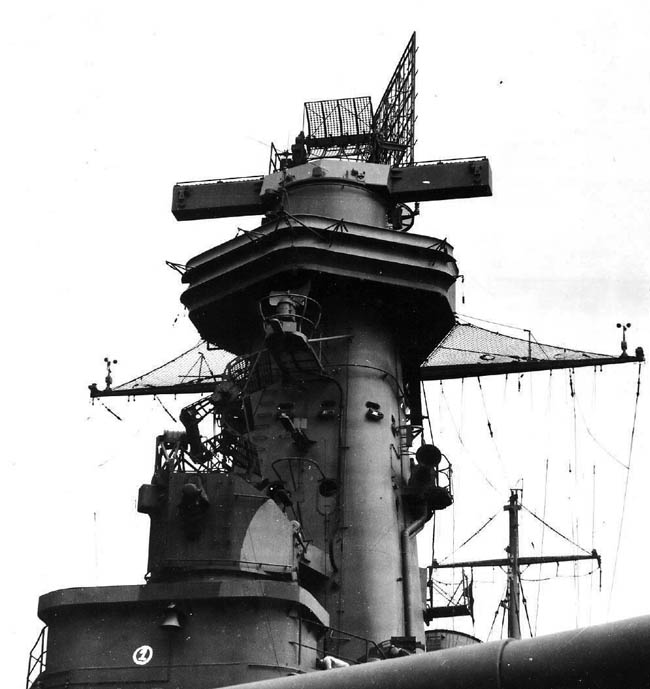

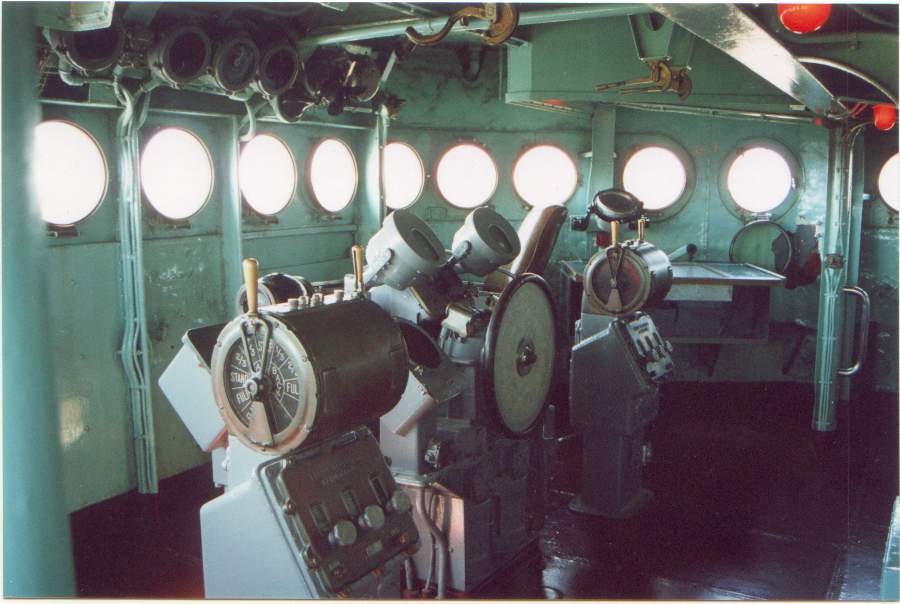

Tower foremast view

The tripods and cage masts were replaced by a streamlined superstructure, something not so new as it was already experimented in the rebuilt New Mexico class. It was a three-level superstructure, with a massive tower almost looking like a keep forward, based on the main structure, and pointing at 120 feet above the waterline. The bridge was located mch lower, but still with room to see generously above the superfiring turret, and two levels: The classic enclose bridge dotted with portholes, and not squared windows as in the past, chosen both for structural integrity and standardization. There was an open bridge above doubling all the commands but with additional pivot lookout googles and flag management, so one could be used as admiralty bridge at all times.

If the tower fore and aft provided superb platforms for the fire controls, the several levels provided room for additional equipments, yardarms and halyards to run up signal flags but also battle lookouts and searchlights as well as automatic antiaircraft weapons and the secondary conning station plus radio/radar antennae, still not designed or planned in 1937. The choice of such superstructure, which was also retaken with little changes for the next classes, was also a radical improvement over the “cramped” bridges of the previous dreadnoughts, arranged in tight spaces between turrets and funnels, with little room between the armored conning tower and mast.

The two main battery fire control directors, on top of tjeir respective towers fore and aft, were assisted by four secondary battery directors (for the 5-in/38), ideally positioned aloft. They had commanding fields of vision which allowed them to exploit their rather excellent arc of fire to the fullest. The 5-inch gun mounts indeed were clustered around the superstructure to allocate them the widest possible fields of fire and provide the ship at last with a superior antiaircraft capability. This was the final recoignition, still dubious for some in the admiralty board, of the primacy of the aircraft threat above all others. Indeed this was the first time secondary battery did not prioritize surface targets. This was an afterthough for these 5-in/38. Still, their depression allowed on paper to do short work of any incoming small torpedo vessel or destroyer. In reality, the Japanese “long range” torpedo out-ranged them.

Onboard aviation

OS2U Kingfishers on their catapults aft, with a Ceremony in honor of the king onboard USS Washington.

From their entry into service to early 1945, both battleships were fitted with two catapults mounted aft, and a single service crane at the poop, for three floatplanes: One ready on each vatapult, and one in between on the “neutral spot” to be loaded onto a catapult after it was fired. According to navypedia, Curtiss SOC were used before the Kingfisher but i found no photos to back this up.

They carried until 1945 the standard Vought OS2U Kingfisher. This monoplane was not supremely agile, powerful or fast, but capable of a considerable range for a single engine model. It was trusted for a variety of missions with its crew of two:

-Reconnaissance and observation. The long glass canopy offered an observer/radio/gunner and pilots excellent visibility despite the low wing mount. What was spotted was communicated by radio.

-Gunnery spotting: A more precised and codified role to offer gunfire adjustments from a better position. This role faded in 1944 as better radars allowed precise long range gunnery tracking.

-Search and rescue: A role that became prevalent during air battles. Many stranded pilots were saved by this plane although carrying capacity was reduced.

-ASW patrols. They could carry small depth charges underwings, but this was rarely done in practice; In general their military payload was light and they only carried a defensive 0.3 cal. and two in the wings for strafing attacks. At best they could force a submarine to submerge.

In 1945, they opted for the Curtiss SC Seahawk. Faster at 313 mph (504 km/h, 272 kn) they still had a 625 mi (1,006 km, 543 nmi) range and limited armament of two wings .50 in (12.70 mm) M2 and two 325 lb (147 kg) bombs under-wing. They operated them until 1947.

Construction

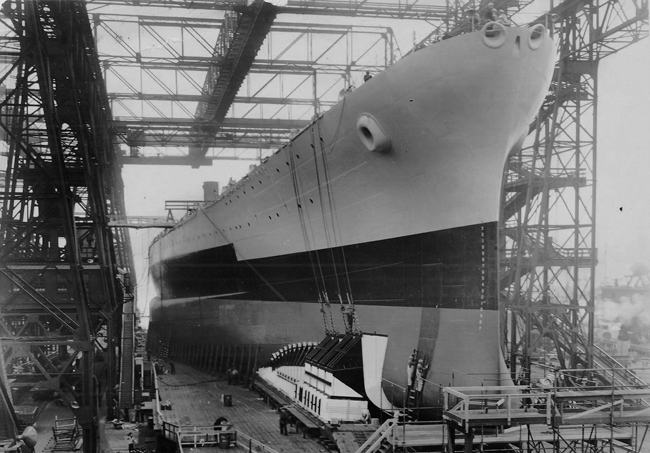

North Carolina prepared to launch 1940

Launching, June 1940

Shakedown cruise, May 1941

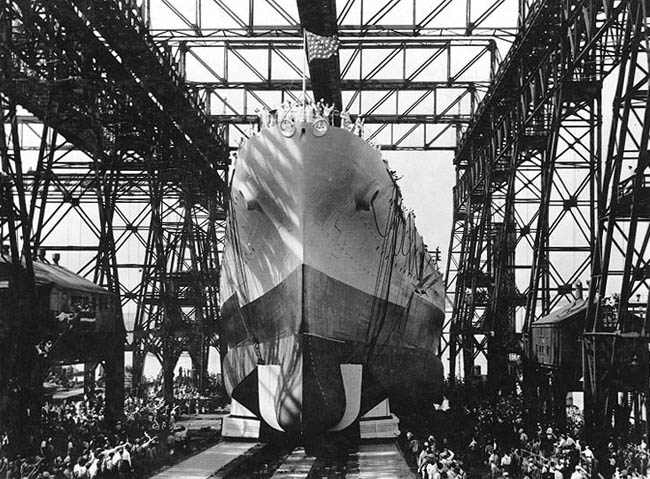

Launch of USS Washington, NARA

North Carolina (BB55) was ordered and built in New York Naval Yard in Brooklyn, laid down on 27 October 1937, launched on 13 june 1940 and completed on 9 april 1941. The delay was due to her numerous vibrations fixed; delayng her shakedown cruise and earning her the name of “showboats” as nicknamed by the New Yorkers, often in and out. Stricken in 1960 she was preserved and became a museum ship.

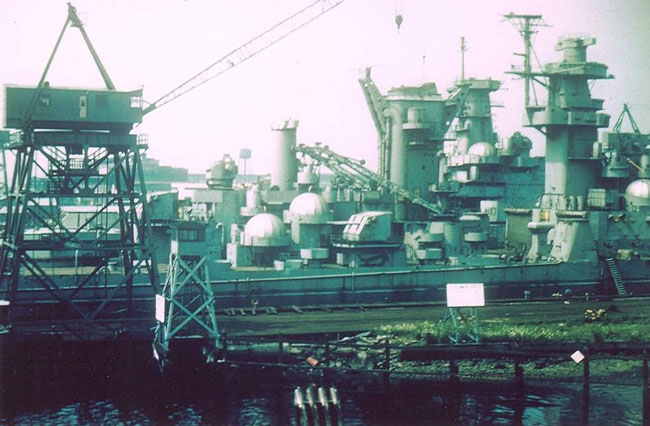

O, her side, BB56 (USS Washington) was started in Philadelphia Naval Yard on 14 june 1938, launched earlier than her sister ship on the 1st June 1940, and completed later, on the 15 May 1941, going through the same fixes. She was stricken 6.1960 and did not hade the chance of a preservation. Instead, she was scrapped in 1961.

Wartime modifications

USS North Carolina in 1945

By late 1941, North Carolina was given an extra quadruple 28mm/75 Mk 1 or 1.1 in “Chicago Piano”, making a fifth mount, completed by twelve 0.5 in M2 HMGs.

In March 1942, USS North Carolina was given 33 single 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon guns in complements to the 1.1 inches and radars were installed: A large surface/aerial warning radar CXAM, two Mk 3 for the main fire contro l systems and three Mk 4 radars for the 5-in AA control.

In April, North Carolina received seven extra 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon guns, and Washington at the same time received in turn twenty 20mm/70 Mk 4 AA and the same electronics suite and radars as her sister ship. In July 1942, both received sixteen extra 0.5 in M2 (12.7mm/90) heavy machine guns, but they still retained their 1.1 in AA batteries. In September USS Washington received twenty additional 20 mm Oerlikon Mk.4 for a total of forty, which she kept until the end of the war.

In November 1942 North Carolina still kept five quadruple 28mm/75 and 28 0.5 in M2 HMGs in addition to ten quadruple 40mm/56 Bofors Mk 1.2 AA and six additional 20mm/70 Mk 4, plus the SG radar and Mk 4 radars.

At the same time, her sister ship USS Washington kept 28 M2 HMGs and received two additional quadruple 28mm/75 Mk 1 and the same SG and Mk 4 radars.

In April 1943, USS Washington received at last 29 Oerlikon 20mm/70 Mk 4 (by now all 0.5 in M2s were discarded) and her sister ship in June received four quadruple 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, also presumably replacing her 1.1 in mounts. In July, USS Washington still retained six quadruple 1.1 in /75 and obtained in additional ten quadruple 40mm/56 Mk 1.2 Bofors. In August, she would also receive five additional quadruple Bofors, likely to replace her 1.1 in quads.

By november 1943, USS North Carolina received an additional Bofors quad mount (possibly above her B turret), and in March 1944, n new Mk 3 radar as well as seven 20mm/70 Mk 4 AA, a second SG radar, a new SK radar and new fire control radars, two Mk 8s and the Mk 27. Her sister ship had to wait until April 1944 to receive an additional Oerlikon gun, a a new quad 20/70 Mk 4, SG (2nd), another quad bofors, and the same radars. By September 1944, modifications were mostly of electronics: USS North Carolina Received four Mk 4 radars, the new SK-2, a,d four Mk 12.22 radars plus the TDY ECM suite. Her sister ship received the same also.

By the summer of 1945, USS North Carolina had 33 20mm/70 AA guns in all and nine quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, but she received eight twin 20mm/70 Mk 4 AA guns for the first time, and the new SR, SCR-720 radars. By tat time, her full load dispacement reached 46,700 tonnes. Her sister ships had to wait for the autumn to reach the same standard, her own dispalcement reaching 46,796t.

After the war, in January 1946, BB55 and BB56 had forty Oerlikons Mk 2, twenty Mk.10 and eight twin 20mm/70 Mk 24, three Seahawk seaplanes, two SG, two SK-2, one SR, one SCR-720 radars and the Mk 3, two Mk 8, four Mk 12.22, plus Mk 27 fire control radars and the TDY ECM suite. In 1946-1948, thir AA was considerably reduced: Only two quadruple 40mm/60, twenty 20mm/70, eight twin 20mm/70 Oerlikon MK.24. USS Washington however kept a quad 20mm/70, and sixty-three single 20/70, plus eight 20mm/70 Mk 24 mounts.

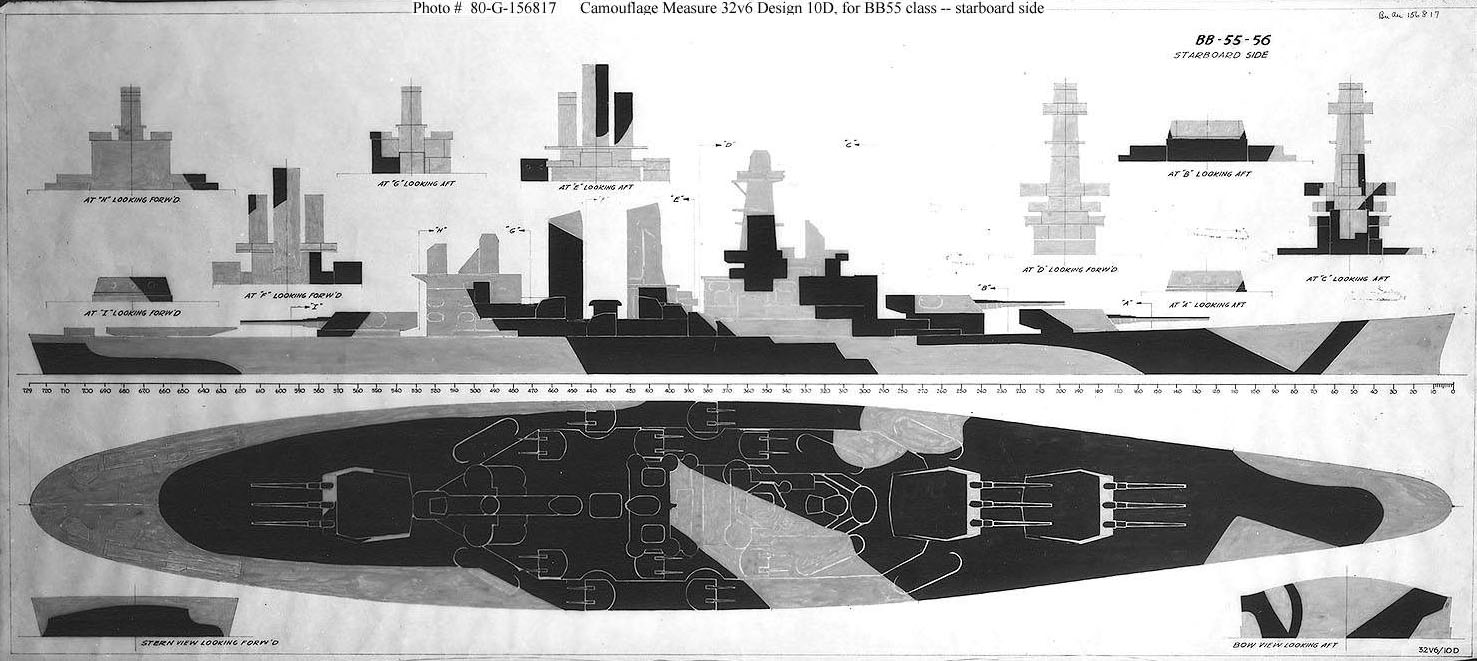

Measure 32 V6 Design 10D for the BB 55 class

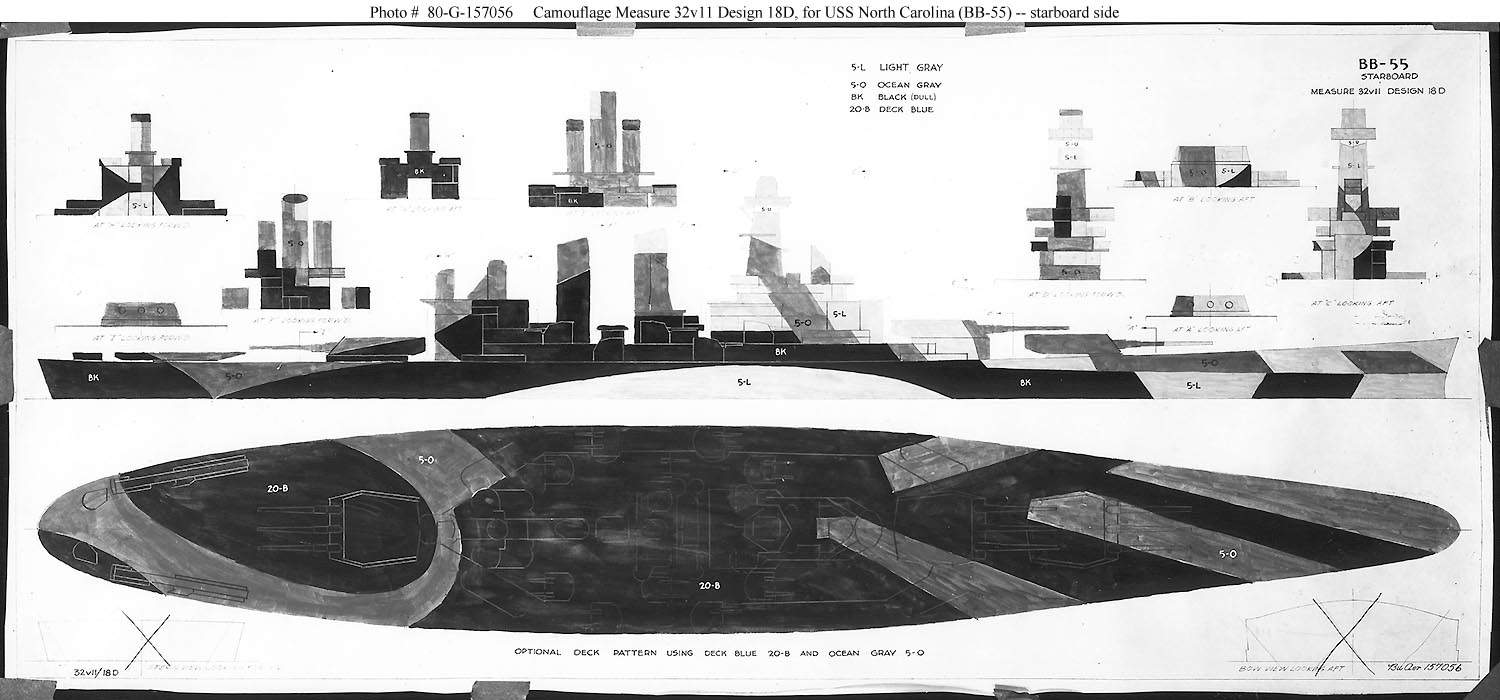

Measure 32 V11 Design 18D for the BB 55 class

North Carolina class specifications 1941 |

|

| Dimensions | 222.12 m long, 33 m wide, 10 m draft |

| Displacement | 37,500 t. standard -44 377 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft GE turbines, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 121,000 hp. |

| Speed | 28 knots |

| Range | oil 6260 tons, 17,450 nm at 15 knots |

| Armament | 9×3 406, 10×2 127 mm, 4×4 28 mm (1.1 in), 12 x 12.7 mm AA |

| Armor | 330-406 mm max |

| Sensors* (late 1942) | CXAM, 2x Mk 3, 3x Mk 4 radars |

| Onboard aviation | 3 Vought Kingsisher seaplane, 2 catapults |

| Crew | 1,880 |

Resources

Links

steelnavy.com

On web.archive.org

warshipprojects.com

Additonal photos on tumblr.com

BB55 on navsource.org

BB56 on navsource.org

Src: pdf “development of the world’s fastest battleship” by J. David Rogers.

Books

USS North Carolina (BB-55): From WWII Combat to Museum Ship (Legends of Warfare) David Doyle

USS North Carolina Squadron At Sea David Doyle

The Battleship USS Iowa (Anatomy of The Ship) Stefan Draminski

Burr, Lawrence, and Peter Bull. US Fast Battleships 1936–47: The North Carolina and South Dakota Classes. Osprey

Moss, Stafford. “A Comparison of Machinery Installations of North Carolina, South Dakota, Iowa and Montana Class Battleships. Warship International

Friedman, Norman. U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis

Garzke, William H., and Robert O. Dulin. Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. Annapolis

McBride, William H. “The Unstable Dynamics of a Strategic Technology: Disarmament, Unemployment, and the Interwar Battleship.”

Muir Jr., Malcolm. “Gun Calibers and Battle Zones: The United States Navy’s Foremost Concern During the 1930s.”

“North Carolina” in the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command.

Whitle, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis

“Washington” in the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command.

Videos

Comparison on the battleships new jersey channel

Drachinfels on North Carolina

Naval Legends (WoW) uss north carolina

On C-Span.org

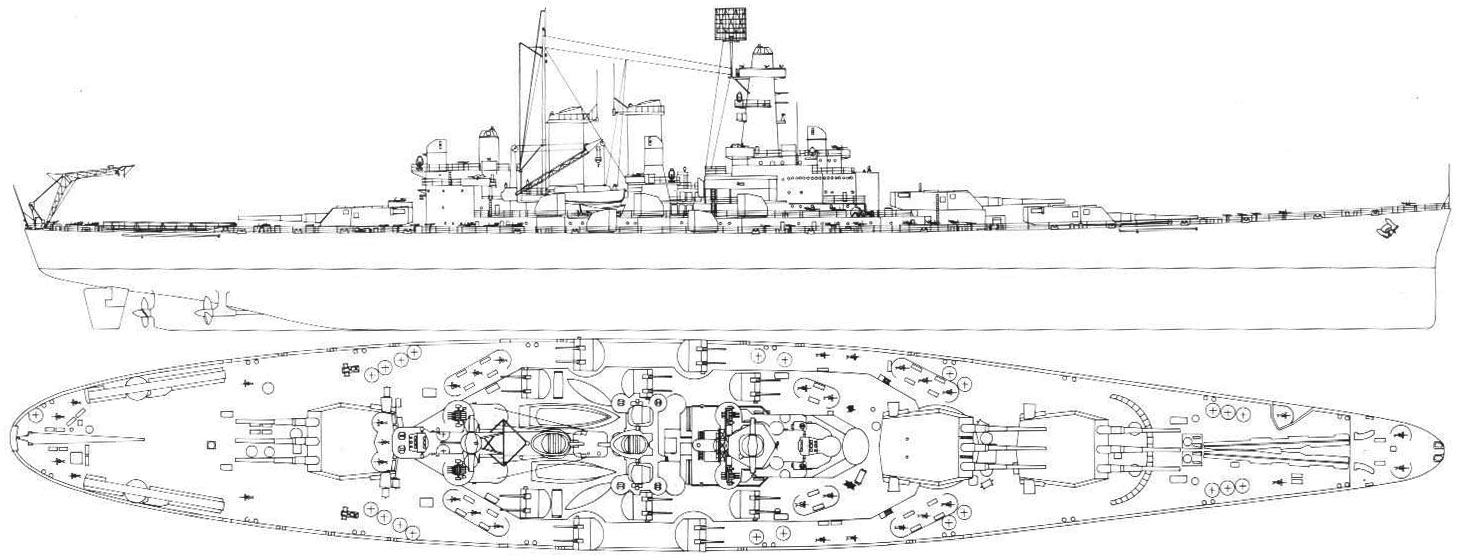

Profiles

Old profile of USS Washington in Guadalcanal, late 1942. More modern, HD ones to come.

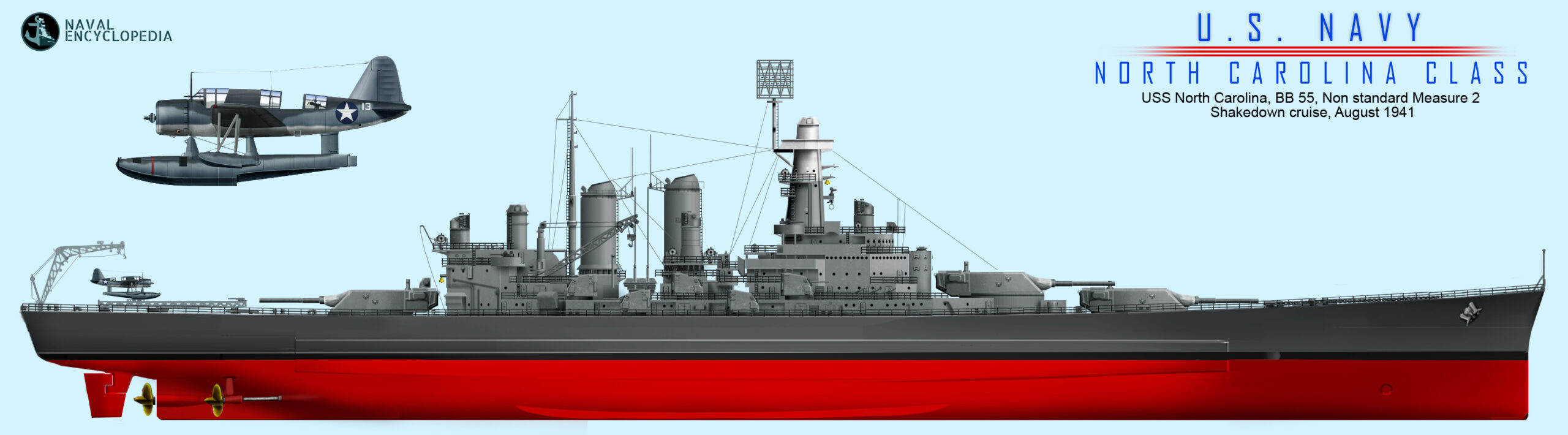

USS North Carolina as comissioned, non standard Measure 2, August 1941

3D

north carolina on cgtrader.com

The Battleship USS North Carolina (Super Drawings in 3D) Paperback – May 19, 2015, by Stefan Draminksi (Author).

The modeller’s corner

Review of the 1/700 ship on modelwarships.com

All kits on scalemates.com

Warship Pictorial 29.

USS North Carolina Technical Reference 1 2nd Edition Perfect Paperback – May 25, 2007

by Randall S. Shoker (Author), Randall Shoker Chelsea Shoker (Illustrator)

1:400 U.S. North Carolina Class Battleship Emulational DIY 3D Paper Card Model Building

The North Carolina class in service

USS North Carolina (BB 55)

USS North Carolina (BB 55)

Commissioning ceremony, 9 April 1941

USS North Carolina was commissioned on 9 April 1941 after much a troubled start, the “showboat” suffered from severe vibrations issues that needed to be adressed. The commissioning ceremony was attended by the Governor of North Carolina (J. Melville Broughton). Her first Captain was Olaf M. Hustvedt. After preparation, she sailed out for her shakedown cruise in the Caribbean Sea as it was the custom, and took her position in the Atlantic fleet neutrality patrol strategy this year and until the rest of 1941.

Underway for her shakedown cruise

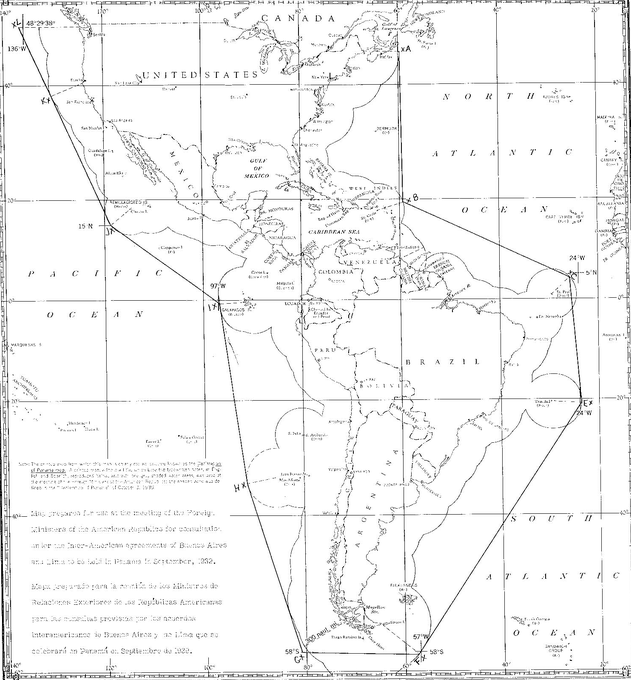

She ventured along the coast, from Newfoundland to the Carribean, according to the Declaration of Panama (1939). The latter as assorted by a map with specific marks, some personally drawn by President Roosevelt and points prepared by a draftsman howing the precise 300 nautical miles from the coast to patrol, in some points exceeding 300 nautical miles offshore. Not to risk her in particular in the late “quasi-war” further east as U-Boat activity became increasingly aggressive, she stayed on this 300 nm coastal area practicing. This was too late for a fleet problem, but she trained wth cruisers, aircraft carriers and destroyers, perfecting navigation, safety, gunner drills in case of war.

Declaration of Panama 1939, establishing neutrality patrol zones

After 7 December 1941 North Carolina stated extensive battle training and was prepared to depart for the Pacific. In April 1942, she was however still deployed in the Atlantic coast. King affected her to Naval Station Argentia from 23 April, the centerpiece of a quick reaction force that was to intervene to prevent a potential sortie of the KMS Tirpitz in case she would make a breakout and prey on convoy lanes in the North Atlantic. However at that stage she was, and remained in Norway.

North Carolina departed in late May 1942, replaced by the brand new battleships USS South Dakota, just commissioned. USS North Carolina headed for Panama and crossed the Gates in June 1942. Teaming with the aicraft carriers USS Wasp and Long Island, escorted by nine destroyers she was assigned from 15 June to Task Force 18 (USS Wasp), and joined by four cruisers. TF 18 was under command of Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes. With that, she departed for the Carolines to take har part (and make histroty) in the long campaign of Guadalcanal.

Firing her main guns, May 1941

USS North Carolina’s captains

-Olaf Mandt Hustvedt (left) to oversee the fitting out of the new battleship North Carolina (BB-55). He became North Carolina’s first commanding officer upon her commissioning on 9 April 1941. On 23 October 1941, Hustvedt became chief of staff for the Commander-in-Chief, United States Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King.

-Captain Wilder Dupuy Baker (next) was the commanding officer of the battleship North Carolina (BB-55) from 5 December 1942 to 27 May 1943

-Captain Frank George Fahrion (last) was the commanding officer of the battleship >North Carolina (BB-55) from 6 September 1944 to 26 January 1945.

Guadalcanal campaign

USS North Carolina was reassigned to TF 16 centered around USS Enterprise, USS Portland, USS Atlanta, and six destroyers, part of TF 61 (Vice Admiral Frank Fletcher). They headed for creating a cover force, assiting the landing of the 1st Marine Division as they were tasked to seize the airfield constructed by the Japanese. This operation setup a pattern that was repeated until the last days of the war: The mastery of air power through scattered island airfields.

TF 61 in addition to TF 16’s USS Enterprise, also comprised USS Saratoga and USS Wasp. But BB-55 was assigned specifically USS Enterprise on 7 August. Her role was triple: 1-Protecting the carrier from air attack with her AA, 2-Repel any possible surface counter-attack, 3-Bring out reconnaissance and ground support for the Marines.

Soon, the Fear of Japanese land-based torpedo bombers had Fletcher withdrawing his precious carriers on the 8th at a safer position. A Japanese cruiser squadron attacked the night of 9 August, destroyed the escort and savaged the few convoy ships still present. Would Fletcher had left his fleet close, the USN wpuld have avoide a major defeat resulting from the Battle of Savo Island. As a result, the Marines became completely isolated, relying on the few supplies that had been loaded. The Navy considered creating a combat force centered on USS North Carolina with five heavy, one light cruiser, four destroyers, but Fletcher eventually ruled out this and preferred to protect his carrier task forces.

aft view, 1943

Overhead view

front starboard view

First shots: Battle of the Eastern Solomons

USS North Carolina firing over bow

USS North Carolina, would not have to wait much to have her artillery barking in anger: Soon she would take part in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons (24–25 August). A group of Japanese carriers was spotted on the 24th. Fletcher decided to scramble the USS Saratoga’s air group, which soon found and sank the light carrier IJN Ryūjō. The Japanese counterattack however arrived soon, and USS North Carolina’s radars were the first to detect this incoming air force which fell on the task force after 16:00.

The Japanese at first tried to sink USS Enterprise, but North Carolina’s AA fire repelled this attack, in coordination with other ships. USS Enterprise meanwhile sped up to 30 knots in order to have margin for qick manoeuvers as prescribed, leaving however the much slower battleship behind.

Ultimately USS North Carolina was left some 4,000 yards (3,700 m) astern but she was nevertheless targeted by a group of seven Aichi D3A dive bombers at 16:43. They all missed however.

BB 55 In October 1942

USS North Carolina emerged from this first battle unscathed, with just one man killed on the deck by a strafing plane. Meanwhile, she could not protect USS Enterprise, which was hit by three bombs. Meawhile this was traded for the sinking of the IJN Chitose by USS Wasp’s air group. The battleship’s AA gunners that day claimed to have shot down from 7 and 14 aircraft. Historian Richard B. Frank view of the eighteen D3As shot down that day were in large part due to Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters for half, the by ships, and mostly gunners of USS Enterprise.

Norman Friedman relieved also the excellence of the battleships 5-inch guns both on Enterprise and North Carolina in most of the kills, despite difficulties to track targets with their stil primitive fire control radar. In the case of North Carolina, excessive vibration at high speed did not facilitated her task. The sky was also busy with many friendly and hostiles often dogfighting. The effectiveness of her 5-in battery was also noted by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, creating a “steel wall” that was perhaps as indimitating as deadly for Japanese pilots. They were credited for at least five aircraft down.

Underway in the Gilbert islands, November 1943

Attacks from submarines

USS Enterprise being detached for repairs, USS North Carolina was reassigned to defend USS Saratoga (TF 17), with the help of USS Atlanta and two destroyers. They remained off Guadalcanal for several weeks, and during that liong stay, Japanese submarines sneaked in and attempted two attacks on the battlehip. On 6 September, one torpedo was spotted, passing some 300 yd (270 m) off her port side. The second attack on 15 September, attributed to I-19, found its mark: I-19’s captain, feeling a rare opportunity, fired all six bow torpedoes in quick succession, at USS Wasp (TF 18). Tactically, Japanese submarines were tasked to sink US warships above all else, and Yamamoto insisted that the priority targets were always aicraft carriers, that were missed at Pearl Harbor.

Perhaps three torpedoes hit USS Wasp, all of the dreaded Type 95 “long lance” torpedoes, high speed, long range and heavier payload, from 5 nautical miles (9.3 km) away. One hit USS O’Brien that was in their path, a fourth hit USS North Carolina. It struck ther 20 ft (6.1 m) below the waterline, port side. The warhead detonated, creating agaping hole some 32-by-18-foot (9.8 by 5.5 m), blewing up and distorting the heavy plating. Five men were killed. However the excellent ASW protection of the battleship realy showed its value here: The torpedo in fact was absorbed by her deep bulkhead and compartientation, never reached the central machinery spaces. The blast only disabled the forward turret.

The Flooding still made the ship listing of 5.5 degrees to port, corrected but using pumps on starboard and counter-flooding. She was otherwide still fully operational and remained on station with USS Saratoga at 25 knots. For USS Wasp that was another affait however. The inlucky ship had to be evacuated and scuttled. O’Brien also sank, but a month later as her badly damaged hull suddently ruptured. TF 17 withdrawn while North Carolina proceeded to Pearl Harbor for repairs, from 30 September to 17 November 1942.

firing a broadside, circa 1944

In heavy seas, December 1944

Degraded camouflage

Follow-up Operations (1943)

After returning to the South Pacific, USS North Carolina resumed her screening off USS Saratoga and USS Enterprise, completed repaired and hard-pressed as the last operational. The fleet was just strengthened by USS Washington, now flagship of Rear Admiral Willis Lee, the “fleet’s marksman” which contribution to its future successes was invaluable. The two battleships operated together as part of Lee’s TF 64 and covered troopships and suppky convoys to the Solomon Islands in December 1942 and Janury 1943.

In such occasions, BB 55 escorted seven transports with the 25th Infantry Division onboard, en route to Guadalcanal on 1-4 January and later that month, the convoy force now bolstdred by the arrival of USS Indiana, was unfortunately too far south to reach the cruisers hard pressed at the Battle of Rennell Island.

In such occasions, BB 55 escorted seven transports with the 25th Infantry Division onboard, en route to Guadalcanal on 1-4 January and later that month, the convoy force now bolstdred by the arrival of USS Indiana, was unfortunately too far south to reach the cruisers hard pressed at the Battle of Rennell Island.

USS North Carolina was bac to Pearl Harbor in March 1943 for a refit until late Febrary and including the installation of new radars and a modern fire control equipment, a move that will prove instrumental later. She joined at her return TF 36 (Rear Admiral Glenn B. Davis) with USS Indiana and USS Massachusetts. They covered the amphibious assault to isolate Rabaul (Operation Cartwheel) by late June, early July 1943. In September 1943, she returned to Pearl Harbor for a rest, maintenance, and be prepared for the impending attack on the Gilbert Islands.

Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign

False bow, May 1944

For the assault on the Gilberts Islands, USS North Carolina was part in the reorganized TF 50 sub-divided into several task groups or “TG” and she sailed out on 10 November affected as before to USS Enterprise (TG 50.2), reinforced by USS Massachusetts, Indiana, two light carriers (CVL) tasked mainly to provide a CAP and six destroyers, mostly tasked of screen patrol and ASW. One could only see how the protection of this sole fleet carrier, with two extra CAP carriers and three battleships bristling with AA, was improved after the previous losses. CV6 air groups took off to pound Makin, Tarawa, and Abemama from 19 November.

By 8 December, BB 55 was detached to create an all-battleships force, TG 50.8 (Lee) with USS Massachusetts, Indiana, South Dakota, and Washington, to bombard Nauru. The fleet latter resupplied and prepared for the Marshalls campaign. North Carolina escorted the recently commissionned fleet carrier USS Bunker Hill during her strikes on Kavieng (New Ireland) later that month.

On 6 January 1944, TF 58, the famous “fast carrier task force” was created (Rear Admiral Marc Mitscher took command) and USS North Carolina went on as an escort escort as part of TG 58.2. She covered the assault on Kwajalein, and the pre-invasion bombardment, before joining the bombardment group on Roi-Namur with her sister ships and USS Indiana, Massachusetts. She claimed a Japanese cargo in the harbor.

After four days of combat, TF 58 launched a large raid on Truk, the central Pacific IJN staging area, North Carolina being part of TG 58.3. Operation Hailstone was the “Japanese Peal Harbor”, a stunning success with a large tally.

After the Marshalls and Gilberts were in US hands, TF 58 coninue to pound many islands in the central Pacific, in order to prepare the Mariana Islands campaign. Resplenishing at Majuro, TF 58 sailed out in late March on Palau and Woleai (31 March, 1 April), North Carolina claming an aircraft. She departed newt to support the assault on Hollandia (New Guinea campaign) until 24 April and escorted afterwards USS Enteprise for a new raid on Truk (29–30 April) where she claimed another planes, more damaged.

The two Kingfisher floatplanes were sent to retrieve pilots, but the sea state destroyed one, the other prevented ti take off with the additional crew, later picked up by USS Tang. On 1st May, Lee’s battleships were reorganized as TG 58.7 to bombard Pohnpei island. TF 58 was back to resplenish in Majuro and Eniwetok on 4 May while the batteship went on to Pearl Harbor, notably to fix her rudder.

Mariana and Palau Islands campaign (Summer 1944)

Battle of the Marianas, June 1944

Back in Majuro, she was prepared for the Marianas campaign, assigned to TG 58.7, and sailed out on 6 June 1944 to reach Saipan. She bombarded the islandas well as Tanapag Harbor, sinking the small ships present, and destroying Japanese installations. On 15 June, marines landed, and she was called for AA support during the fierce aerial Japanese counterattack, shooting down one of these. Meanwhile, the attack on Saipan mobilized in return the Japanese 1st Mobile Fleet, which sailed out to fell on TG 58.7.

USS North Carolina on 18 June was present, in what became the Battle of the Philippine Sea (19–20 June). Cotituted with an all-battleship strike force with four cruisers and thirteen destroyers, she headed some 15 nautical miles west of the carrier groups to wait for the Japanese. An aerial attack started first, North Carolina and Washington AA guns claiming in common several Japanese aircraft. Between three carriers and hundreds of precious pilots lost, the Japanese were soundly defeated. BB 55 remained on station for two weeks and retured to Puget Sound Navy Yard.

Late campaign (1945)

_salvo_in_1941.jpg)

Color photo of a broadside in 1941

She left the drydock, making a short post-overhaul trial in October 1944 while the Philippines campaign was going on. After sailing to Ulithi on 7 November, assigned to TG 38.3, under Third Fleet command, she had missed the epic Battle of Leyte, but accompanied the carriers on their strikes on Leyte, Luzon and the Visayas, preparing more landings. USS North Carolina shot down her first kamikaze at this occasion. This went on until the attack on Mindoro, by 15 December and USS North Carolina on the 18th weathered Typhoon Cobra with little damage.

Resupplied in Ulithi, she followed the fast carrier task force south, hitting Formosa and the coast of French Indochina as well as occupied China and the Ryuku Islands, all in January 1945. After Formosa on 3–4 January, Luzon on 6-7 January, French Indochina on the 10th, and in February 1944, she escorted the carriers during their air strikes on Honshu, in preparation for the attack on Iwo Jima. The fleet and B 55 (now TF 58 again) made training exercises off Tinian, refueled at sea and went north to launch strikes on the Tokyo area on the 16-17 of February, before refuellig again. TG 58.4 rampaged newt the Bonins, isolating Iwo Jima.

USS North Carolina, Washington, and Indianapolis were detached and reassigned to TF 54 to cover the assault, and stay on station with on demand fire support until 22 February.

Iwo Jima & Okinawa

Underway in 1945

After refuelling on 24 February, she escorted the carrier force striking the Japanese Home Islands, now to isalate Okinawa, the linchpin of the Ryuku islands. This started on 25-26 February, followed by attacks on iwo Jima, refulling on 28 February and raided Okinawa, resupplied in Ulithi (4 March 1945) North Carolina joining TG 58.3.

On 16 March the feet refuelled and launched attacks on Kyushu then withf=drew to refuel on 22 March. despite her AA cover, USS North Carolina could only witness the bad fits and destruction of USS Wasp and Franklin. She was soon tasked with escorting them back to Ulithi.

After the landing on Okinawa (1 April) she stayed for close support, assigned to TG 58.2 and shot down three kamikazes. However during one of these fierces AA barrages, a 5-in shell landed on USS North Carolina, killing three, wounding 44. This was her gravest incident so far, and was a “blue on blue”.

On 7 April, she shot down a single Japanese bomber and 11 April, shot down one probable, and two more on 17 April, before being sent as bombardment group at Okinawa. She departed afterwards for Pearl Harbor.