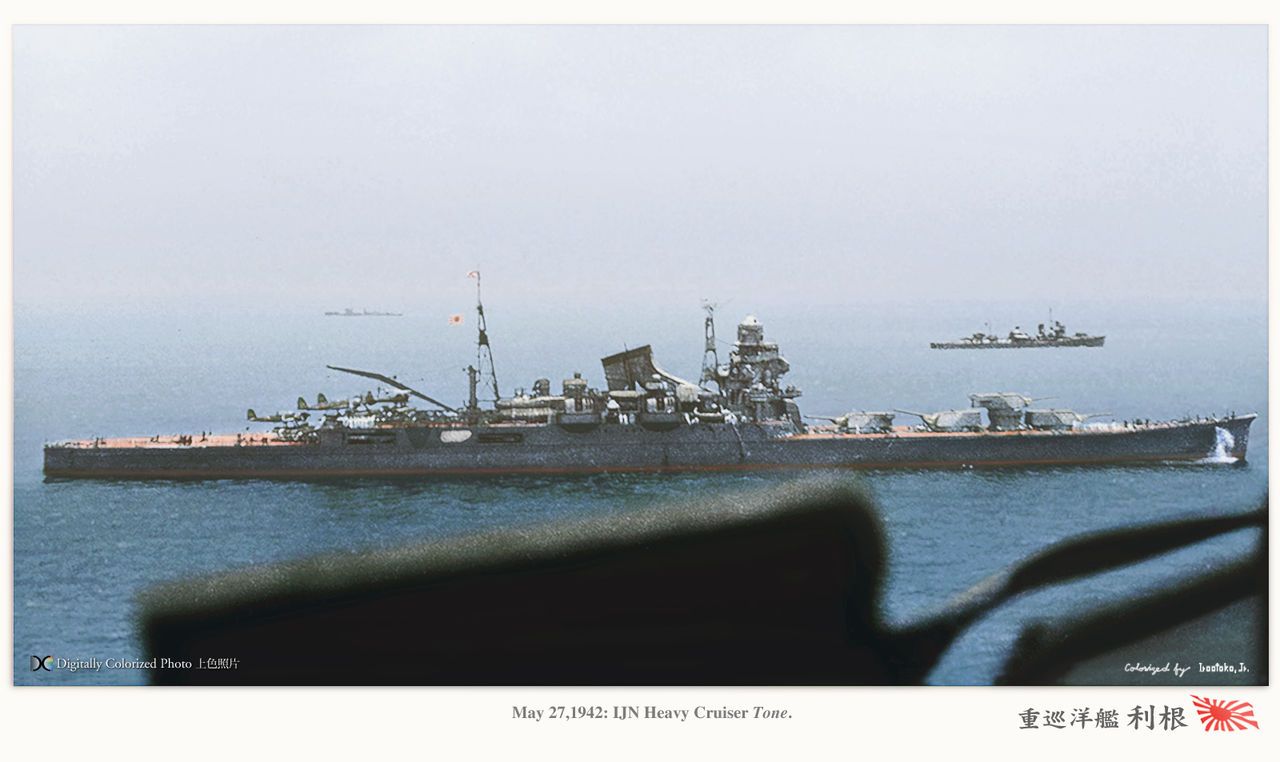

Heavy Cruisers Tone, Chikuma.

Heavy Cruisers Tone, Chikuma.WW2 IJN Cruisers:

Furutaka class | Aoba class | Nachi class | Takao class | Mogami class | Tone classTenryu class | Kuma class | Nagara class | Sendai class | Katori class | Agano class | Oyodo

Tsushima | Asama | Tokiwa | Yakumo | Izumo | Kasuga | Hirado

The last IJN heavy cruisers

The Tone class cruisers, IJN Tone and Chikuma were part of the 1932 supplemental plan. However, in 1938-39, Japan tore off all treaties and reconsidered a new naval plan. It was decided for example to complete them as heavy cruisers, with their initial 155 mm (6-in) triple turrets discarded for 8-in twin turrets, while their hull was strengthened considerably, reaching a displacement way over all treaty limits.

Their hybrid nature was unique, with all their artillery concentrated forward mostly to compose a thicker, but more compact citadel. This had the effect of creating improved living quarters as well as leaving their aft deck free for extra aircraft accommodations and extensive reconnaissance capabilities with six instead of one to four floatplanes. So, despite their appearance, they were scouting cruisers rather than converted “hybrid” ships like the battleships Ise and Hyuga. Both cruisers were very active in WW2, between Wake, the East Indies, the raid on Australia or the Indian Ocean, Midway, Guadalcanal, Rabaul, the Philippines sea, and Leyte. IJN Tone survived the war and was destroyed at Kure but Chikuma was lost in the Battle off Samar on 25 October 1944.

From Light to Heavy Cruisers by treaty

The 4th fleet incident and consequences

The development of the Tone class was very much chaotic. They started as planned in FY 1932 as treaty-bound light cruisers, very much similar to the Mogami class, a repeat with a few improvements, sticking to the apparent 10,000 tonnes standard limits.

In 1936, rising nationalism and militarism in Japan led to the nation leaving the Washington Treaty altogether. From then on, Japan would disregard all limitations imposed by the 1921 treaty of Washington, the 1930 treaty of London, and the 1935 second London Conference. Naturally, the first sensible measure was to go back to an 8-in (203 mm) armed heavy cruiser. The switch from “light” to “heavy” was made simply by swapping to 8-in guns, by treaty virtues. In any case, after the many design modifications implied, this led to a much heavier design.

The motivation behind this redesign, which delayed the launching of both vessels by years, was twofold. Initially, the Tone-class cruisers were simple repeats, ordered as the 5th and 6th Mogami class cruisers, with small improvements, making them a subclass rather than a full-fledged class of ship.

Construction began based on these prospects in the Mitsubishi Naval Yard, on 1 December 1934 and 1st October 1935 for Tone and Chikuma respectively. However, while the ships were under construction, the IJN Mogami was just making her sea trials, revealing serious weaknesses in the hull design. A design change was further compelled by the “Fourth Fleet incident” on 26 September 1935. It occurred during an exercise when the 4th fleet under command of Hajime Matsushita was playing the “opposing force.” During the sortie, very foul weather started to disturb operations, and soon degenerated into one of the fiercest typhoons Japan ever experienced. Two ‘Special Type’ destroyers, Hatsuyuki and the Yūgiri had her bow ripped off by waves while all the heavy cruisers taking part received grave structural damage. The admiralty concluded it needed to quickly reinforce all its ships, even if it meant retiring them for lengthy reconstructions. This was the fate of the Mogami class and many others. It was also decided to change future (and just started) design construction, with the Tones bearing the brunt of these changes.

1936: Japan leaves the Naval treaties

The second major driving force in the change of the Tone’s design was Japan’s refusal to comply with the limitations of the last Naval Treaty. In 1933, after the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing grave financial crisis that wrecked the economy of the whole world, amidst acute social discontent, Japan saw the widespread rise of extremism. The rise of Hitler to power was mirrored in Japan by a more proactive military clique, starting with a coup d’état attempt in Japan by March 1931, launched by the radical Sakurakai secret society within the Imperial Japanese Army, aided by civilian ultranationalist groups. By March 1935, Hitler himself announced that Germany would no longer abide by Part V of the Treaty of Versailles regulating the size and composition of German armed Forces, while Mussolini’s Italy started a colonial campaign in Abyssinia, a sovereign nation, leaving the league of nations powerless to prevent it.

Japan’s policies from then on were largely decided by militarists and decisions towards the navy were influenced by the Vinson-Trammell Act voted in 1934, or the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. So by 1934, Japan announced they planned to leave the treaties in two years and although at the Second London conference of 1935, delegates showed a willingness to negotiate, they eventually left the conference by January 1936 while considering that older treaties expiring on December 31, 1936, they were in their right to follow their own path without violating the law.

That’s why notably Japan refused to allow British inspectors to know about a rumored colossal new secretly built battleship. In the same vein, they were now able to rebuild all their cruisers well above old tonnage treaty limits, which they did, plus new ones well above the 12,000 tonnes mark standard as well as a new design of “super cruisers”. note.

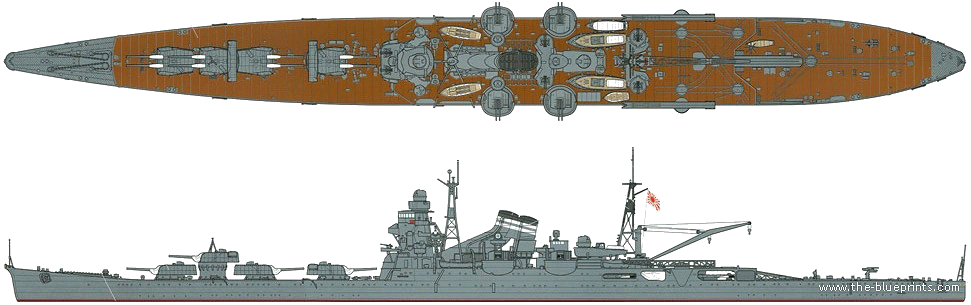

Design

The first point dictated a series of design revisions, notably reinforcing the hull with extra bracing and thicker plating in sensible places, and since cracks in the hulls of the new Mogami indicated grave shortcomings in electric welding for the seams, it was decided to go for more traditional and proven techniques to hold the hull together. The second major change, from the Mogami to the Tone in their definitive form, was to not only swap to 8-in turrets, basically, (with the engineers taking the model used on the previous Nachi and Takao classes) but due to a request from the admiralty for better protection around the ship’s vitals, the old idea of concentrating artillery like on the 1927 Nelson class and just launched Dunkerque class was brought up.

It was decided that the new cruisers would reduce their main armament from five triple turrets as initially planned (and as the ONI believed) to four concentrated forward and just a single raised turret in the no.2 position (or “B” turret), thus reducing top weight over the deck and devoting it to onboard aviation on the freed aft space as the admiralty was ready to sacrifice firepower to test the concept of a “reconnaissance cruiser”.

Hull and general characteristics

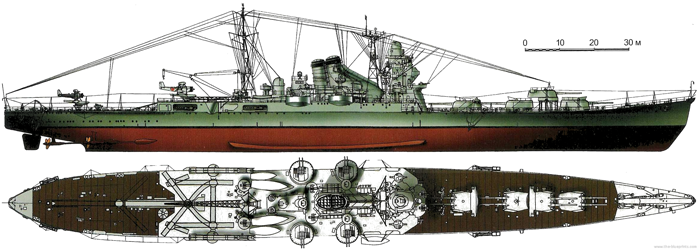

The Tone looked like a Mogami on which the main armament was fully rearranged forward, pushing back the superstructure of the Mogami, but keeping the same basic hull form, just shortened and strengthened. The hull measured 189.1 meters long (620 ft 5 in) – versus 201.6 m (661 ft 5 in on Mogami) and the beam 19.4 m (63 ft 8 in) versus 20.2-20.6 m (67 ft 7 in) on the rebuilt Mogami and Susuzya sub-classes. The narrower width was a decision to maintain a favorable hull ratio and preserve speed. For draught, however, it was increased to 6.2 m (20 ft 4 in) on the Tone versus 5.5 m (18 ft 1 in) on the Mogami’s.

This resulted in deeper vessels with a tonnage jumping to 11,213 tons (11,392 tonnes) standard and 15,200 tons (15,443 tonnes) fully loaded, versus originally 8,500 tons standard load and 10,980 tons at full load for the Mogami’s before reconstruction. The gap of 1,500 tonnes towards the maximally allowed tonnage was a reserve for upgrades. But by doing a 200 meters vessel based on such displacement, troubles inevitably lie ahead. The Tone was shorter, narrower, and yet far heavier, with most of the extra tonnage going into structural reinforcement and thicker construction plating, plus riveting instead of welding in many places, also making the whole hull heavier. Though the construction of Tone was more advanced, she had far more wielding seams than Chikuma, making her a bit lighter.

Despite the concentration of a forward of the armament, the main superstructure was not pushed back that far, being ahead of the mid-section, with the truncated funnels and a well-spaced main mast aft, creating a rather aesthetical result. Seen from afar, it was difficult in fact to distinguish them from other heavy cruisers. Indeed, compared to the Nachi/Takao her forward deck was just longer by the length of a turret.

Protection

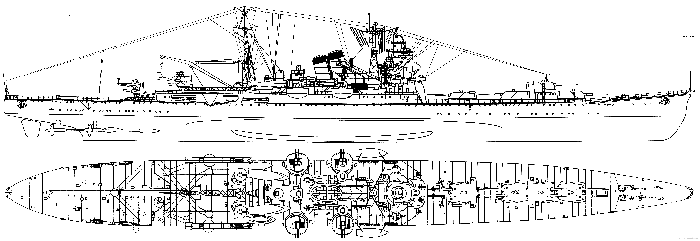

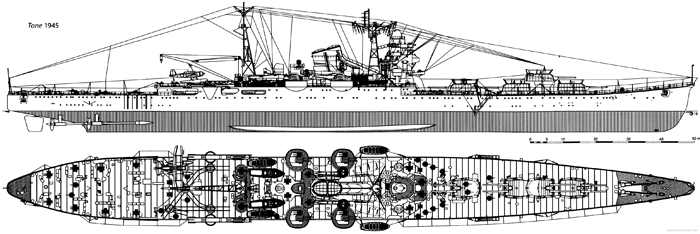

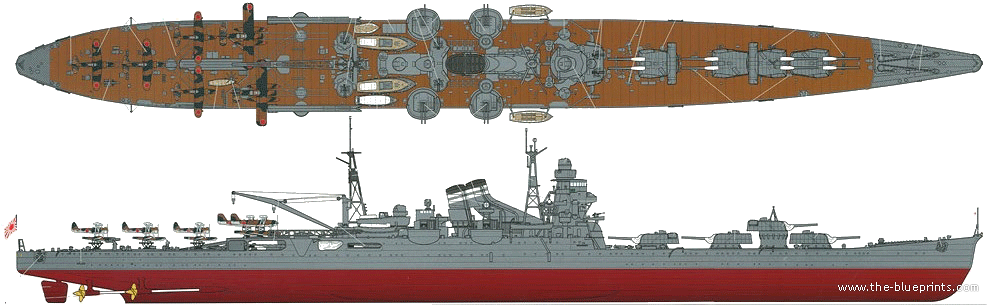

2-views of the class

Tone had some welding done on her hull before changing track, but Chikuma was an all-riveted design, like the Nachi/Takao. The undulating hull was dispensed with, and the superstructure was less extensive to spare weight, and preserve stability. The main belt armor was 150 mm (5.9 in) thick along the machinery spaces, and even 225 mm (8.9 in) next to the magazines; It extended down underwater to 9 feet (2.7 m) and tapered down much to meet the anti-torpedo bulkhead, and itself ended down to the inner double bottom, covering most of the length. Here are the details:

- Main belt, citadel: 145 mm (5.7 in)

- Belt, machinery space: 150mm (5.9 in)

- Belt, ammo spaces: 225 mm (8.9 in)

- Armoured deck: 30 mm flat section, 65 mm slopes and above ammo/machinery/steering spaces (2.6–1.2 in)

- Main turrets: 25 mm (2 in)

- Main turret barbettes: 25 mm (2 in)

Powerplant

The main engines of the Tone class were similar to that of Suzuya and Kumano in order to cut build time. They had four propellers, driven by two Gihon geared turbines, themselves fed by eight Kampon double-ended, oil-fired boilers, for a total output of 152,000 shp (113,000 kW), providing a top speed of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph). It was two knots less than the 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph) of the initial Mogami class (though this dropped after their reconstruction).

These cruisers had a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), the same as the Mogami, but at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). Technically they carried more oil to achieve the same range at a faster top speed. The very last planned cruisers, the Ibuki class, had the same powerplant, but also for 35 knots and a lesser range, 6,300 nmi (11,700 km; 7,200 mi) at 18 knots. These were minor improvements over the last pair of the Mogami class.

Armament

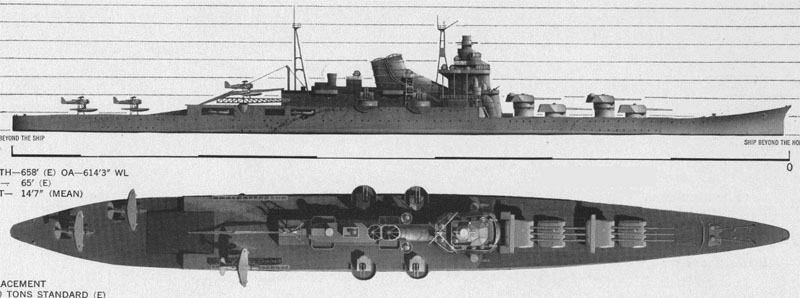

ONI plate showing the 1939 supposed appareance of the Tone class. See the old style bridge and triple turrets.

After the 1936 modifications, they ended with 8-in turrets all forward, a powerful torpedo armament plus their extended scout capacity, inspiring the reconstruction of the Mogami in 1942. Their anti-aircraft artillery started initially with twelve 25 mm AA guns in six twin mounts, getting up to thirty in early 1942 and fifty-seven by 1944, though it still did not prevent the Tone being sunk by aviation.

Main

Regarding the main artillery of the Tone class, the substitution of twin 203 mm (Model 2) turrets from triple 155 mm turrets took place during construction. The twin turrets were said to be of the E3 type, with identical characteristics to those of the Mogami “modified E2” installed during reconstruction on the Mogami class, except the compensation for the barbettes diameter difference, 5.70 m for the 6-in triple but only 5 m ( feet) for that of the 8-in models.

These were of the 20 cm/50 3rd Year Type naval gun type, and their design started in 1926 before being put into service for the 2-Go in 1932. These built-up guns had an inner A tube encased by a second tube in a full-length jacket. Breech loaded with two cloth bags of smokeless powder and Welin breech block, on a Type E gun mount. They fired at 30° to 25 km (15 miles) with a muzzle velocity of 1247 ft/s (380 m/s) for AP shells. On paper, the Type E allowed a maximum elevation of 70° but 55° was more practical on the Tone class.

Secondary

These were the ubiquitous dual-purpose 12.7 cm/40 (5 inches) Type 89 naval guns found on all IJN vessels of the time. They were located on four sponsons on the broadside.

AA armament

There too, the AA armament comprised twelve Type 96 25 mm (0.98 in) AA guns in six dual mounts. Over time (see modifications) they were increased to triple ones and single ones in 1944 were added to reach a total of 64 on Chikuma by 1945. For lighter AA, Japanese Navy Type 93 13.2 mm heavy machine guns in several twin or single mounts were added.

Torpedo armament

The Tone class, like the Mogami and previous classes, carried an impressive torpedo armament, made up of no less than twelve 610 mm (24 in) torpedo tubes (with reloads) in four triple banks placed in niches along the superstructure aft. They fired the legendary Type 93 “long lance” but the Tone class unlike many other cruisers never had the occasion of using them in battle in a decisive way.

Onboard Aviation

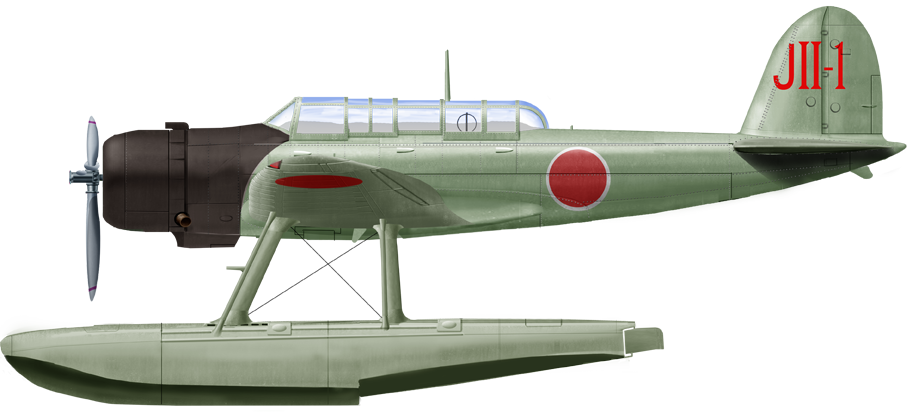

Aichi E13A1 model 11, IJN Chikuma, 1941

These Tone class cruisers were the first to carry so many floatplanes, though their air group changed over time. At first, it seemed they carried six Nakajima E8N biplanes (as seen in some pictures) or a mix of three E7K1, and three E8N1 “Dave”, all obsolete in 1942. However, during the attack on Pearl Harbour they both flew a mix of E13A and Nakajima E4N2 Type 90-2, to have long and short-range reconnaissance. They were replaced by five Aichi E13A monoplane floatplanes. The number dropping from six to five as the new planes were larger. The aircraft accommodations comprised two catapults installed on either side of the quarterdeck aft, on sponsons, and the handling of the planes was done by a lattice crane anchored on a crane pole at the base of the mainmast.

Seaplanes were strapped in chariots rolling on rails with hubs crisscrossing this aft deck and a ramp going to the lower deck long track, being able to store two more. There was no hangar through. These aircraft needed to be protected from the elements and were maintained at sea, with their mechanics constantly fighting the problem of highly corrosive saltwater and extremes of temperatures on deck.

Traditionally in IJN doctrine, seaplane tenders/carriers were used for amphibious operation’s air support, but the cruisers traditionally provided the “eyes of the fleet”, sending their floatplanes in all probable directions of the enemy. With radar nonexistent in 1936 when these cruisers were redesigned, the capacity of bringing six reconnaissance planes allowed them to be excellent spotters.

Construction and modifications

IJN Tone in 1941 and 1945, showing the differences.

IJN Tone was ordered in FY 1932 but was delayed and eventually laid down on 1 December 1934 at Mitsubishi NyD, launched on 21 November 1937 after a redesign, and Commissioned on 20 November 1938.

IJN Chikuma, like Tone, was ordered in the 1932 Fiscal Year, but was delayed and only started at Mitsubishi NyD, laid down on 1 October 1935, and then was completely redesigned, launching therefore much later on 19 March 1938 and Commissioned on 20 May 1939.

On March 1943, both cruisers received two twin 25mm/60 Type 96 and Type 1 2-go radars. In January 1944 they received also both two extra twin 25mm/60 and four twin plus four single 13.2/76mm AA HMGs. By July 1944 IJN Tone received four extra single 13.2mm/76 and four triple 25mm/60 plus twenty-five single plus two Type 2, 2-go radars and a type 3 1-go radar.

In July 1944 her sister Chikuma also received four extra single HMGs and four triple 25mm/60 plus twenty-three single and the same radar suite. The survivor in February 1945 IJN Tone received seven single 25mm/60, the 21-go radar, and later four extra triple 25mm/60 96-Shiki and a third Type 2 2-go radar.

Tone in 1938

Chikuma in 1941

Author’s illustration – IJN Tone

⚙ Specs 1941 |

|

| Dimensions | 201,5 m x 18,50 m x 5,9 m draft |

| Displacement | 12,400 t. standard; 15,200 t. Fully loaded |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Kampon turbines 12 admiralty boilers, 152 000 hp. |

| Speed | 35 knots |

| Range | 7,750 nmi (14,350 km; 8,920 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | From 130mm (magazines) down to 25 mm decks |

| Armament | 8 x 203 mm (4×2), 8 x 127mm (4×2), 30 x 25 mm AA, 12 x 610 mm TTs (4×3), 6 floatplanes |

| Crew | 850 |

Sources/ Read more

Books

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-1947

Anthony P. Tully, ‘Solving some Mysteries of Leyte Gulf: Fate of the Chikuma and Chokai ‘, Warship International No. 3, 2000

Wildenberg, Thomas. “Midway: Sheer Luck or Better Doctrine”. Naval War College Review 58, no. 1 (Winter 2005).

Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press (NIP).

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. NIP.

Jensen, Richard M. (2001). “Re: Fate of Chikuma and Chokai”. Warship International. International Naval Research Organization.

Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. NIP.

Lacroix, Eric; Linton Wells (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. NIP.

Whitley, M.J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. NIP.

Links

.militaryfactory.com

ww2db.com

combinedfleet.com – Tone description

world-war.co.uk

forum.worldofwarships.com

Navypedia

combinedfleet.com: Chikuma: tabular record of movements

combinedfleet.com: Tone: tabular record of movements

www.cofepow.org.uk

The model’s corner

Tamiya’s 1/350 Ship Series No.24 Tone

Needless to say, the class has been generously served by all Japanese manufacturers at many scales, from 1:200 by GPM to tabletop games scale at 1:2000/3000, and through the 1:350 and 1:700.

The Tone on scalemates (all kits)

The Chikuma on scalemates (all kits)

3D renditions on Behance

The Tone and Chikuma in action

IJN Tone was at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, before participating with her sister ship (same division) in the Battle of Solomon Islands in August 1942, Santa Cruz Islands, at the Second Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942.

Tone and Chikuma were engaged in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, under the command of Admiral Kurita. During the engagement, IJN Chikuma suffered attacks from US Navy aircraft and sank on 25 October 1944. Tone survived the epic battle, and was based in the home Islands, notably Kure, but remained mostly inactive due to the lack of fuel oil. She was bombed by USN aviation in Kure, during the great raids of the 3rd Air Force in July 1945, and sank in shallow waters on the 25th. She was later captured, loaded with explosives, and blasted on site, and her remains remained there until 1948. She was scrapped afterward.

IJN Tone

IJN Tone

IJN Tone in 1941

IJN Tone entered service on 20 November 1938 and was captained by Captain (later Vice Admiral) Hara Teizo. She was attached to Yokosuka Naval District, and by 20 October 1939 Captain Hara was appointed the CO of Chikuma as an additional duty. On 15 November 1939, Captain Onishi Shinzo took command while the ship underwent gunnery drills and exercises. In December of that year, she joined the Maizuru Naval District with her sister ship now operational, and ready for missions, and by 15 October 1940 Captain Nishida Masao took command. Exercises went on in home waters (she saw no deployment in China). By 10 September 1941m Captain Okada Tametsugu took command while Nishida was reassigned to IJN Hiei.

Pearl Harbour & Wake

On 26 November 1941 at last, after three years of training, both cruisers were mobilized for Operation “Z”: As part of CruDiv 8, Tone and Chikuma departed Hitokappu Bay and Etorofu Island in Kuriles with Vice Admiral Mikawa Gunichi’s Support Force’s BatDiv 3 and the First Air Fleet Striking Force (Kido Butai). Thus, both Tone and Chikuma would take part in the attack on Pearl Harbor. On 7 December 1941, they both launched one Aichi E13A1 “Jake” floatplane for a final weather reconnaissance over Oahu. At 06:30, they launched several Nakajima E4N2 Type 90-2 as pickets and patrollers south of the Striking Force. Tone’s floatplanes flew to Lahaina but found no targets present. On 16 December, CruDiv 8 was ordered to participate in the second attack on Wake Island (the first was repulsed). Tone launched two Nakajima E8N for ASW patrols before and during the operation to watch for a possible reinforcement fleet. After the fall of Wake, CruDiv 8 returned to Kure for upkeep and a refit.

New Guinea and Australia

From 14 January 1942, CruDiv 8 was sent to Truk in the Carolines, to cover the landings of Japanese troops at Rabaul in New Britain. Later, it took part in shelling and giving AA cover for two more operations on Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea. Ten days later, Tone’s floatplanes attacked the Admiralty Islands, and on 23 January 1942, two E13A1 floatplanes and one E8N2 from Tone attacked and bombed Buka Island. On 1st February, following the attack on Kwajalein, in the Marshalls, by Vice Admiral William Halsey from USS Enterprise, Tone departed Truk with the Kido Butai in pursuit, but found nothing.

Chikuma and Tone also took part in the Raid on Darwin, Australia (19 February). Their floatplanes loaded with bombs took part in the attack, while others covered the area for possible reinforcements or targets. Tone’s floatplanes reported weather conditions before the raid but its radio failed and it went back without reporting. Another replaced it and met, and then shot down a RAAF PBY Catalina, the first “kill” of Tone’s air group. TONE’s floatplane No.2 also located two ships off Cape Foureroy, which were later sunk by D3A1 dive-bombers from IJN Akagi. From 21 February 1942, CruDiv 8 escorted CarDiv 1 and DesRon 1 to Staring Bay for refueling before joining Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake’s BatDiv 3’s and CruDiv 4’s from Palau to refuel, and create a new battle group to attack the Dutch East Indies.

Battle of the Java Sea

On 25 February Operation “J” was launched, the Invasion of the Netherlands East Indies. Leading it was a battlefleet under the command of Vice Admiral Kondo (flagship IJN Kongo), and BatDiv 3/2 (Kongo-Haruna) was detached along CruDiv 4 (Atago-Takao) joined later by DesDiv 15 from Timor, chasing off ABDA damaged vessels while the remaining forces force supported carrier attacks on Java with CruDiv 8, DesRon 1 and six tankers.

On the 27th, USS Langley (AV-3) and her escorts, USS Whipple (DD-217) and USS Edsall (DD-219) were located by floatplanes and soon attacked by 16 GM41 “Betty” bombers from Takao NAG Denpasar, Bali, and escorted by six A6M2 fighters from Tainan NAG.

They badly damaged Langley, which was abandoned. Edsall picked up 177 survivors, and Whipple 308 as both navigated to meet USS Pecos (AO-6) off Christmas Island to transfer their rescued crews when more bombers arrived, forcing them to scatter. They were en route on 1 March 1942 when Tone spotted USS Edsall some 250 miles (400 km) SSE of Christmas Island. She was reported by the E13A as a Marblehead-class light cruiser and Kondo ordered BatDiv 3/2 and CruDiv 8 to intercept her. She was spotted at 16:02 16 miles away, heading north when Chikuma caught her and opened fire. She was soon followed by the capital ships but they failed to sink her. In the end, she was finished off by 26 D3A1 “Val” from Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu.

On 2 March 1942 CruDiv 8 and BatDiv 3/2 rejoined the Carrier Striking Force, and on the 4th, Tone’s floatplanes and those of Chikuma took off to bomb Tjilatjap. On 6 March, IJN Tone rescued a British seaman adrift after his ship was sunk off Java on 27 February, and he was duly interrogated. On the 11th after the surrender of the Dutch East Indies, they arrived at Staring Bay, Kendari, Celebes.

Indian Ocean Raid

Operation C was prepared with a starting time of 26 March 1942. The involved ships soon departed for the Indian Ocean and separated. CruDiv 4’s Chokai and CruDiv 7’s Suzuya, Kumano, Mikuma, Mogami, the light cruiser Yura, along with IJN destroyers attacked merchant traffic in the Bay of Bengal on 1st April. On the 5th, Tone covered the Kido Butai as they launched 315 aircraft against Colombo, Ceylon. HMS Tenedos, the armed merchant cruiser HMS Hector and 27 aircraft were destroyed in the attack. Later, Tone’s floatplanes took part in a wide search in which HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire were spotted and then also attacked and sunk. Tone returned to Japan by mid-April 1942, but was immediately assigned to chase Admiral Halsey’s TF 16.2 in the wake of the Doolittle raid.

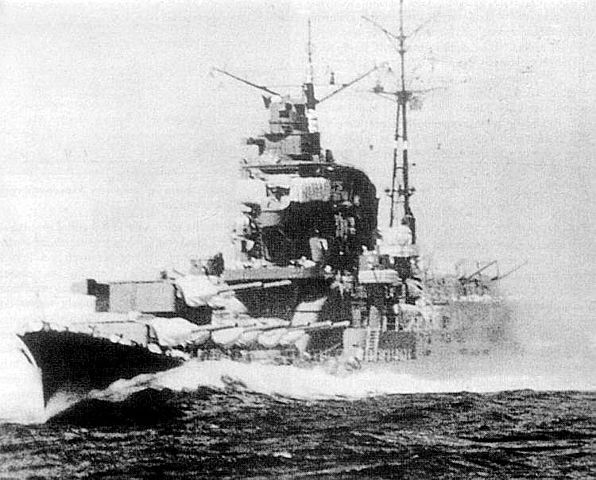

Battle of Midway

During Operation Mi, Tone was still part of CruDiv 8, protecting Nagumo’s Carrier Striking Force. On 4 June, Tone and Chikuma each launched “Jakes” to search within a 300 miles (480 km) area for American carriers. Tone’s floatplane No.4 was delayed in takeoff, but this allowed it to spot the US Carriers on its return. Despite this bit of good luck, its message had to go through the command structure and was not immediately delivered to Nagumo. This crucial delay is what doomed his fleet as his air group was prepared with bombs for a second strike against the island and had to entirely convert to torpedos to launch an air strike instead on the US carriers. This took place while the US air attack began. Tone meanwhile was part of the covering fleet, and was also attacked by US carrier aircraft but sustained no damage, although it lost a “Dave” during the battle, which was likely shot down.

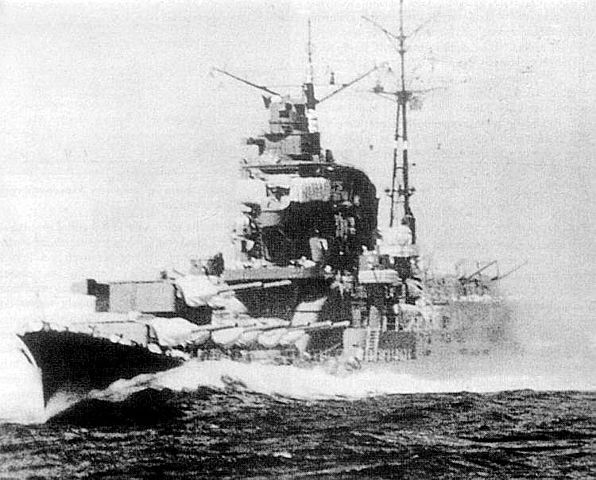

Tone during the battle of the Eastern Solomons, 24 August 1942

With her sister resupplying back home, Tone was detached to support Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya’s Aleutian invasion force. But the anticipated American counter-attack never materialized, leaving CruDiv 8 patrolling the area for nothing before going back to Japan and being prepared for future operations. Here, Rear Admiral Chuichi Hara commanded CruDiv 8 starting on 14 July 1942. As a result, both the Tone and the resupplied Chikuma were sent to Guadalcanal shortly thereafter.

Ordered south on 16 August with the reconstructed Kido Butai ( Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Zuihō, Jun’yō, Hiyō, and Ryūjō) and joined by the BatDiv 2’s Hiei, Kirishima, and the seaplane tender Chitose plus the cruisers Atago, Maya, Takao, Nagara, they soon took part in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. On 24 August 1942, CruDiv 7 (Kumano and Suzuya) joined the “reinforcement fleet” when the next morning a Consolidated PBY Catalina spotted IJN Ryūjō, and she was shortly thereafter attacked by planes from the USS Enterprise but managed to evade them.

Meanwhile, seven floatplanes from Tone and Chikuma were launched to try to locate the US fleet. While a plane from Chikuma spotted them in good order, it was quickly downed. It took a second float plane to spot the US fleet later that day. However late, this information enabled the Kido Butai to launch an air strike focusing on USS Enterprise, which was hit and assumed sunk. In the meantime, a strike from Saratoga sunk IJN Ryūjō. Tone, escorting the carrier at the time, was also attacked by was able to dodge a strike by two Avengers. She was soon able to return to Truk.

Battle of Santa Cruz

By October 1942, Tone patrolled north of the Solomon Islands, expecting the recapture of Henderson Field. However, with this not occurring, on the 19th, escorted by IJN Teruzuki, she was detached for an independent mission, intending to locate the US fleet. For the first time, she was able to play the role intended for her and her sister since 1936. She found nothing and was reunited with her sister off the Santa Cruz Islands. There, as usual, at dawn, both launched their reconnaissance air group, but at the same time, a Kawanishi H6K “Emily” from Jaluit Atoll sighted a carrier off the New Hebrides. On the 26th, 250 miles (400 km) northeast of Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe orders another flotplane recce flight of seven to scout south of Guadalcanal, which succeeded in locating the US fleet. Abe then ordered an air strike, succeeding in sinking USS Hornet, also damaging USS South Dakota and the cruiser USS San Juan. However, two of the four aircraft launched by Tone during the attack were shot down.

After the battle, Tone returned to the Guadalcanal area, supporting Japanese reinforcement efforts until mid-November 1942. She was next assigned to patrols around Truk in January and mid-February 1943. After which, she returned home for a refit on 21 February. There she was rearmed and given a radar set and was back in operations with CruDiv 8 on 15 March 1943, under orders of Rear Admiral Kishi Fukuji, in Truk. On 17 May, Chikuma and Tone escorted IJN Musashi back to Tokyo for the state funeral of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

Back in Truk by 15 July, Tone went on patrolling these waters, and though she was ambushed by US submarines several times, she never suffered any damage. From July to November 1943, she was detached to take part in many troop transport runs to Rabaul. She kept patrolling the Marshall Islands and took part in the unsuccessful chase of the American fleet which raided the area. She was back in Kure on 6 November for a refit, with extra modifications. After post-refit sea trials and training in home waters in January, her Captian learned that CruDiv 8 had been disbanded since the 1st. From now on, the inseparable sisters were reunited in CruDiv 7, which also comprised the Mogami-class IJN Suzuya and Kumano, all under Rear Admiral Shoji Nishimura. Tone was back in Truk on 2 January and in February, where she assisted with the evacuation of the Palau islands.

On 1st March 1944, she was assigned to commerce raiding in the Indian Ocean, and on 9 March, her floatplanes spotted the British freighter SS Behar, which she soon closed on and sank. She still took aboard some 108 survivors, against orders to leave them at sea, showing the captain’s humane qualities, something rare in the IJN. 32 survivors were disembarked as POWs in Batavia. Meanwhile, Admiral Naomasa Sakonju (flagship IJN Aoba), ordered that the remaining prisoners be “disposed of”, and beheaded at sea. (Which would lead to Sakonju’s execution for war crimes.) Captain Haruo Mayazumi, for his actions in the atrocity, was sentenced to seven years imprisonment. On 20 March 1944, RADM Kazutaka Shiraishi took command of CruDiv 7 while Tone was back in Truk.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

Tone resupplying from a fleet oiler in 1944

On 13 June 1944, Admiral Soemu Toyoda ordered the start of “Operation A-GO”, the defense of the Mariana Islands. Tone was assigned to Force “C” (Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet), and was in the Visayan Sea before heading to the Philippine Sea, heading for Saipan. On 20 June, Haruna, Kongō, and Chiyoda were attacked by USS Bunker Hill, Monterey, and Cabot. The Japanese air cover was destroyed in the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”. The battle was lost.

IJN Tone retired to Okinawa and afterwards returned to Kure. She stayed there for a refit on 26 June-8 July 1944, with more AA and radars being added. She ferried troops to Okinawa and was reassigned to Singapore in July, now the ideal place to resupply the oil-hungry IJN cruisers.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

On 23 October 1944, Tone was assigned with IJN Kumano, Suzuya, and her sister ship Chikuma to be part of the Center Force for the upcoming Sho-Go plan. She left Brunei with Admiral Takeo Kurita’s First Mobile Striking Force, but as they proceed, the fleet was attacked by ambushing Gato and Tench class submersibles in the Palawan Passage. Atago and Maya were sunk, and Takao was badly damaged, leaving her namesake class gutted. Entering the Sibuyan Sea on 24 October, the Center Force was struck by eleven raids from TG 38.2.

Musashi was sunk, and as her escort, IJN Tone came under attack as well. She was targeted by scores of Avengers, but despite gallant dodging by the crew, the USN tactic of pincer attacks worked and she was hit by bombs. At Samar later it was the turn of Yamato, Nagato, Haruna and Myōkō to be damaged while attacking Taffy 3 and retire. Tone then attacked USS Heermann but could not get past a fierce air attack, and was damaged again, forcing her to break off and escape back through the San Bernardino Strait without further damage, but Tone’s sister ship Chikuma was lost, along with the cruisers Chōkai and Suzuya.

The end in Japanese waters

Tone under attack in 1945

On 6 November 1944, Tone departed Brunei towards Manila, but was rerouted to Mako in the Pescadores, before arriving in Japan, entering Kure and the dry dock in Maizuru. There, she received extra AA and a Type 22 radar. However her unit, CruDiv 7 was disbanded on 21 November. She was reassigned to CruDiv 5, with IJN Kumano. On 18 February 1945, she was sent to Etajima but was moored there due to the shortage of oil, acting as a training ship. There was a first air raid on 19 March where she was slightly damaged but was able to be repaired. She then returned to Kure.

The wreck of Tone in August 1945. Note the camoufage, well visible on her main B turret here.

On 24 July 1945, TF 38 launched the largest air strike against Kure of the war. The goal was to finish off what remained of the IJN. 9 torpedo bombers from USS Monterey targeted IJN Tone, which was immobile. She was quickly hit by three bombs along with several near misses which shook her to the core. Her hull fractured, causing much flooding, and she sank and settled to the bottom, though a part of her was still above water and able to deliver still some AA fire. Due to this, she was attacked again on 28 July, this time by Corsairs and Hellcats loaded with rockets and AP bombs coming from the USS Wasp, Bataan, and Ticonderoga. This destroyed her completely. Struck on 20 November 1945, and her remains were removed in 1947–1948.

The downfall: A camouflaged IJN Tone at Etajima, July, 29, 1945. She was badly damaged by an air raid on the 24th and finish off by another the day before this photo was taken. colorized by irootoko jr.

IJN Chikuma

IJN Chikuma

IJN Chikuma was completed at Mitsubishi on 20 May 1939 and assigned to CruDiv6 (or “Sentai 6”), Second Fleet later to be renamed as CruDiv8 in November 1939. She took part in initial training, gunnery drills, shakedown cruise, and then regular combat exercises in Japanese home waters. It seems that, unlike her sister Tone, she did operate off southern China on three occasions, between March 1940 and March 1941. In late 1941, she trained with Tone in order to play her part in the attack on Pearl Harbor, launching an Aichi E13A1 “Jake” floatplane for weather reconnaissance over Oahu before the attack.

Chikuma in 1941

This was completed by sending a flight of Nakajima E4N2 Type 90-2 Reconnaissance Seaplane as pickets south of the Striking Force. Nine anchored American battleships were reported. By 16 December, CruDiv 8 took part in the second attempted invasion of Wake Island. Chikuma lost one flotplane to AA but the crew was rescued. After some time in Kure, on 14 January 1942 she departed for the Caroline Islands, covering landings at Rabaul in New Britain and like her sister supported the attacks on Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea followed by the Admiralty Islands.

Her role in the attack was completed by sending a flight of Nakajima E4N2 Type 90-2 Reconnaissance Seaplane as pickets south of the Striking Force. Nine anchored American battleships were reported. By 16 December, CruDiv 8 took part in the second attempted invasion of Wake Island. Chikuma lost one floatplane to AA but the crew was rescued. After some time in Kure, on 14 January 1942, she departed for the Caroline Islands, covering landings at Rabaul in New Britain and like her sister supported the attacks on Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea followed by the Admiralty Islands.

The US raid on Kwajalein led to an unsuccessful pursuit in which she took part. Next, she took part in the Raid on Port Darwin in Australia, on 19 February, and started operations linked to the Japanese invasion of Java. On 1 March 1942, a floatplane located the 8,806-ton Dutch freighter Modjokerto from Tjilatjap, and both sisters escorted by Kasumi and Shiranui intercepted and sank her. They also later spotted USS Edsall, which was fired on by Chikuma from 11 miles (18 km), though she missed. Hiei and Kirishima joined in, but Edsall’s Captain managed to dodge all their 297 14-inch, and 132 6-inch shells plus the 844 8-inch and 62 5-inch rounds from the cruisers. More so, when the range closed, the latter fired her 4-inch guns at Chikuma. Eventually, the combined fire added on by dive bombers from Sōryū and Akagi crippled her, before she was finished off by Chikuma.

On 4 March, Chikuma also sank the 5,412-ton Dutch merchant Enggano and a day later, her floatplanes loaded with bombs took part in the attack on Tjilatjap. After the surrender of the Dutch East Indies, she was resupplied and prepared for the raid in the Indian Ocean. It started on 5 April 1942. CruDiv 8 covered the Kido Butai, launching 315 aircraft on Colombo. Later they claimed HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire. Next, an air raid hit Trincomalee. Later, HMS Hermes and her escort HMAS Vampire, the corvette HMS Hollyhock, an oiler, and a depot ship were spotted and sunk at sea. The fleet went home by mid-April 1942, but they were immediately sortied again to try to catch TF 16.2 after the Doolittle Raid.

Like Tone, Chikuma also took part in “Operation Mi”, which evolved into the Battle of Midway. CruDiv 8 was under the supreme command of VADM Nagumo’s Carrier Striking Force and on 4 June, both launched their Aichi E13A1 “Jake” on a 300 miles (480 km) area in search of the US carriers. Tone’s aircraft spotted them but failed to identify this as a carrier group. Chikuma’s floatplanes found USS Yorktown and shadowed her for three hours. Crucially, this allowed guidance for the D3A “Val” strike that heavily damaged the carrier in the evening. Two other floatplanes from Chikuma still kept an eye on the burning Yorktown through the night but one plane was lost. The remaining aircraft then directed the I-168 which finished off Yorktown in the morning.

Chikuma and Tone were detached to support VADM Boshiro Hosogaya’s Aleutian invasion force but arrived for nothing and after cruising these cold waters, returned to Ominato on 24 June. RADM Chuichi Hara took command of CruDiv 8 in July and both sisters were sent to take part in the invasion of Guadalcanal. On 16 August joined the Kido Butai, two battleships and four cruisers in what became the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. On 24 August 1942, they launched seven floatplanes which located the US fleet in the area. It was one of Chikuma’s that reported the force, but the message was delayed like at Midway. Soon USS Enterprise was badly damaged and the Japanese objective of neutralizing all US carriers remaining in activity was nearly complete. In return though, Ryūjō was sunk by USS Saratoga. Chikuma afterward was based in Truk.

Chikuma under air attacks at Sant Cruz, 26 October 1942

Towards the end of the year, she patrolled north of the Solomon Islands but on 26 October 1942, RADM Hiroaki Abe’s task force launched seven floatplanes to try to see the US fleet south of Guadalcanal, and duly located them, before sending an air raid that sunk USS Hornet, damaging USS South Dakota and San Juan. Chikuma in return had to dodge several Douglas SBD Dauntless attacks from Hornet’s air group. Knowing what happened to other cruisers, she fired her torpedoes just before a 500 lb (230 kg) bomb hit precisely her starboard forward torpedo room. If the “long lances” had been stacked on her, the explosion would have probably broken her in two. She was also hit by two other bombs. One floatplane and its catapult were blasted away at sea. All in all, she suffered 190 killed and 154 wounded, including Captain Komura.

IJN Chikuma, escorted by IJN Urakaze and Tanikaze managed to make it to Truk for emergency repairs. Her machinery was still in good order, but her hull and superstructure had been badly damaged. Next, she sailed back to Kure with the damaged carrier IJN Zuihō during the battle. Repairs were added for refit and her modernization, with new AA and radar, was complete by 27 February 1943.

Chikuma’s main artillery in action

On 15 March 1943, RADM Kishi Fukuji took command of CruDiv 8, and she was back to Truk on 17 May, covering IJN Musashi back to Tokyo, which was carrying the body of Admiral Yamamoto for a state funeral. IJN Chikuma was back in Truk by 15 July and like her sister, dodged several submersibles ambushes along the way. Until November, she performed troop transport runs to Rabaul and patrols in the Marshalls. On 5 November 1943 while refueling in Rabaul she was attacked like her sister by a combined raid of 97 planes from Saratoga and Princeton. A single SBD managed to score a near-miss and caused minor damage. She was in Kure on 12 December. CruDiv 8 was disbanded on 1 January 1944, and now both cruisers were reassigned to CruDiv 7 with Suzuya and Kumano (RADM Shoji Nishimura). She was in Singapore by 13 February, before moving to Batavia on 15 March to be sent for a raid in the Indian Ocean with her sister. On 20 March 1944, RADM Kazutaka Shiraishi replaced Nishimura and made Chikuma his flagship.

On 13 June 1944, a large operation was launched to defend the Mariana Islands, and Chikuma was part of Force “C” (VADM Ozawa, Mobile Fleet), going via the Philippine Sea towards Saipan. On the 20th, there was an air attack on the fleet by Bunker Hill, Monterey, and Cabot, while the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” claimed what was left of the Kido Butai’s veteran airmen. Chikuma soon retired to Okinawa, ferrying troops. After ferrying army troops to Okinawa, she was reassigned to Singapore in July as flagship, CruDiv 4. For her next (and last) operation, she took part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, meeting her fate:

On 23 October 1944, Chikuma led CruDiv 4 (Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone) from Brunei toward the Philippines under VADM Takeo Kurita’s First Mobile Striking Force. In the Palawan Passage, Atago and Maya were sunk by submarines, and Takao was damaged, greatly reducing the amount of Heavy Cruisers Kurita had at play. In the Sibuyan Sea, Musashi was sunk and Myōkō, Nagato, and Haruna were damaged. But it was on the 25 October off Samar that Chikuma, part of the force engaging Taffy 3, a seemingly easy target, tried to sink US aircraft carriers and co-claimed USS Gambier Bay.

Chikuma under bombs, dodging attacks at Leyte

However, as she tried to retire, she was harassed by USS Heermann, combined with a fierce air attack, in which even US fighters were involved. In this though, IJN Chikuma held her own, crippling Heermann until four TBM Avenger torpedo-bombers, led by Lt. Richard Deitchman (USS Manila Bay) lodged a Mk13 torpedo on her stern port quarter. The blast was enough to sever her stern, disabling her port screw and rudder. Crippled, Chikuma was now circling at 18 knots (33 km/h) and down to 9 knots.

At 11:05, five other TBMs, from USS Kitkun Bay hit her portside amidships, with two torpedoes that cracked open her hull and rapidly flooded her engine rooms. At 14:00, slowed down to a crawl, she was attacked by three TBMs from USS Ommaney Bay and Natoma Bay, led Lt. Joseph Cady. They managed to send two torpedoes into her port side. IJN Nowaki took off survivors, but there are conflicting sources of how she was scuttled by her or sunk due to the air attacks. But the survivors’ respite was short: The following day, Nowaki was sunk by gunfire from USS Vincennes, Biloxi, and Miami and three destroyers, sinking 65 miles (105 km) SSE of Legaspi in the Philippines, she took with her 1,400 men: all of Chikuma’s survivors. The sole survivor of the cruiser was not picked up by Nowaki previously and simply drifted ashore to safety. She was officially stricken on 20 April 1945.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign