US Navy Fleet Aircraft Carriers (1942-50): USS Essex, Yorktown, Intrepid, Hornet, Lexington, Bunker Hill, Wasp, Franklin, Ticonderoga, Randolph, Hancock, Bennington, Shangri-la, Bonhomme Richard, Antietam, Boxer, Lake Champlain, Princeton, Tarawa, Kearsage, Leyte, Philippine Sea, Valley Forge, Oriskany

US Navy Fleet Aircraft Carriers (1942-50): USS Essex, Yorktown, Intrepid, Hornet, Lexington, Bunker Hill, Wasp, Franklin, Ticonderoga, Randolph, Hancock, Bennington, Shangri-la, Bonhomme Richard, Antietam, Boxer, Lake Champlain, Princeton, Tarawa, Kearsage, Leyte, Philippine Sea, Valley Forge, OriskanyWW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classThe world’s largest capital ship program

In March 1941, the first of the most prolific series of heavy aircraft carriers in history started with the laying USS Essex’s keel in Newport News. The genesis of these exceptional ships started in June 1939, in the decision to support the three Yorktowns of the Pacific fleet, of which the third, USS Hornet, was still nearing completion (launched December 1940).

For the most part, they resumed the qualities of the previous ships, but this time without worrying about treaty limits. They were defined as a wartime emergency fleet aircraft carrier class, including a number of event-induced upgrades.

For 32 ships programmed, 8 cancelled, 24 were laid down, 17 were completed early enough to see the Second World War and 14 actually seeing combat. USS Essex was completed much earlier than anticipated, on December 31, 1942. But only operational from May 1943, soon joined by not only 13 other sister ships, but the fast ones of the Independence class ☍ (CVL) which were created at the origin as an interim, until the Essex came.

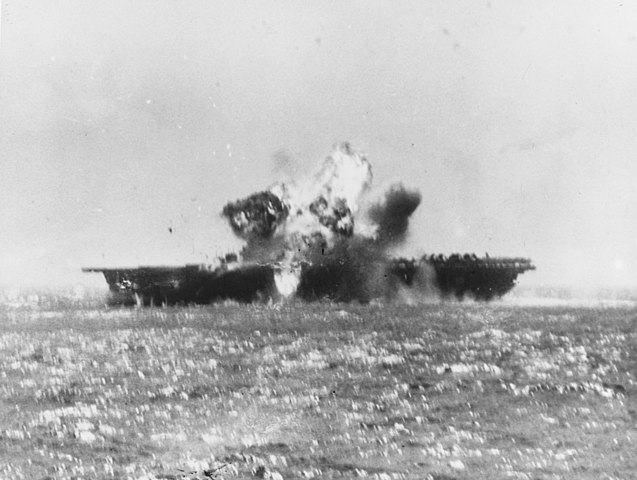

Eventually they will complete the latter well, despite initial reticences of the admiralty. The Essex from mid-1943 to Septemer 1945 played a central role and despite furious reprisals by Kamikaze attacks and heavy damage, none was lost (like USS Franklin).

After Japan’s departure of naval treaties in 1936, the U.S. realized it needed to bolster its naval strength and the Naval Expansion Act of Congress was passed on 17 May 1938, enabling a new 40,000 tons limit for aircraft carriers, the “escalator clause” aslo applied to battleships. This extra tonnage allowed to built the Hornet as a copy-paste of the Yorktowns, as well as the new USS Essex as lead ship of a new class.

They were awaited like the Messiah, with many other programs slowed sown or suspended (notably battleships) to compensate for the loss of Lexington, Yorktown, Hornet, and later Wasp(in the Atlantic) leaving only USS Enterprise (badly damaged several times by the way) and Saratoga (too) to hold the line for months.

Suffice to say that the Essex class would bring a well expected breath of fresh air to the beleaguered US Navy.

But the Essex also formed the backbone of the USN in the Cold War. Until their gradual replacement from frontline duties by the supercarriers of the 1960s, they played their role in Korea but also in Vietnam for many. Gradually modernized and rebuilt to operate jets and helicopters they were still relevant in 1970. One also became also the Apollo program main recovery ship. There were two sub-classes: Ticonderoga, the “long hull” design, and USS Oriskany, which was entirely rebuilt for modern jets and was used as a standard for conversion (Completed September 1950) called SCB-27. As of today, four were preserved: USS Yorktown (Patriot’s Point, Mount Pleasant), USS Intrepid, in New York City, USS Hornet, in Alameda, and USS Lexington at Corpus Christi.

Genesis of the Essex class

Design work on a new (unnamed) carrier design started already in 1939, under the leadership of Commander Leslie Kniskern, appointed as chief design officer, Bureau of Ships. Kniskern coordinated a large amount of data from naval architects, aviation facilities, catapults or arresting gear specialist companies, aviation service, plus a small, but dedicated aviator board. Also the Carrier Desk Officer of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Commander James Russell put its weight in the balance. Russell knew well all pre-war aircraft carriers, landing and taking off from all of these, and just completed at this point a two years tour aboard USS Yorktown, following her initial fitting out. He was both an aviator and naval officer, and almost became Kniskern’s main advisor during the initial process.

Since earlier carrier classes were all the product of international naval treaties restrictions, endlessly playing with nerve-ratching limits, with the Washington Treaty ending in 1936 it became possible to increase carrier tonnage authorized by Congress in 1938. Bureau of Ships just restarted its top design priorities, making a requirement now only limited by the locks at the Panama Canal, the deciding factor for an upper limit in size.

Next in line, came the definitions (with aviators) of the “sunday punch”, composition of the air group onboard that would be responsible for all the tactical operations. The larger size brought hopes to bring up the total number onboard of just 100 aircraft, plus spares. Next came in hierarchical order its composition, the balance within this projection of force between fighters (both for strike escort and as local defence – CAP), bombers and torpedo-bombers.

Eventually, by tweaking with other aspects of the design and making some compromises, it was found best to reduce this initial requirement to a compliment of 90 aircraft, notably due to the fact they all needed to be spotted on the flight deck at the same time, for a fully armed deck-load launch, single strike which was precisely called the “Sunday Punch”. The concept was developed during academy war games years, and allowed the greatest tactical efficiency in operations. In practice though, it was never applied exactly like the theory, at least at Midway, when emergency dictated a launch in “penny packets”, but at least in the less strainous conditions from 1943 when Essex-class ships carried out their first strikes, it was applied.

Another fact entering the equation was the growing size and weight of naval aircraft. In 1939, the USN park still comprised several biplanes, notably the F3F, F2F, FF, Curtiss SBC Helldiver, etc. but the Douglas TBD Devastator that was just entering service was massive compared to these, up to 10,194 lb (4,623 tons.) fully loaded, with a wingspan of 50 feet. This would require more square footage, more free deck forward for take-off. Catapults were also part of the design but stayed as an option, as slowing down the ship’s “full strike” delivery. At the time, simply pointing the ship towards favourable ocean winds across the deck was enough, with full throttle, wheels blocked starts.

Requirement to spot 90 planes on the deck ready for launch still was a daunty challenge for all designers, using scaled-up version of the Hornet as a starting point. Extra space was soon found by eliminating the two starboard gun sponsons (compensated later by the island’s twin turrets), extending the flight deck. The island itself was made sufficiently off-board and narrow to free deck space, and since USS Wasp experimented with an external aircraft elevator now met widespread approval. This deck edge elevator still, could fold up for the Panama canal crossing. All the tricks in and out of the book were proposed and adopted to maximize flight deck space (see later about the “sunday punch”).

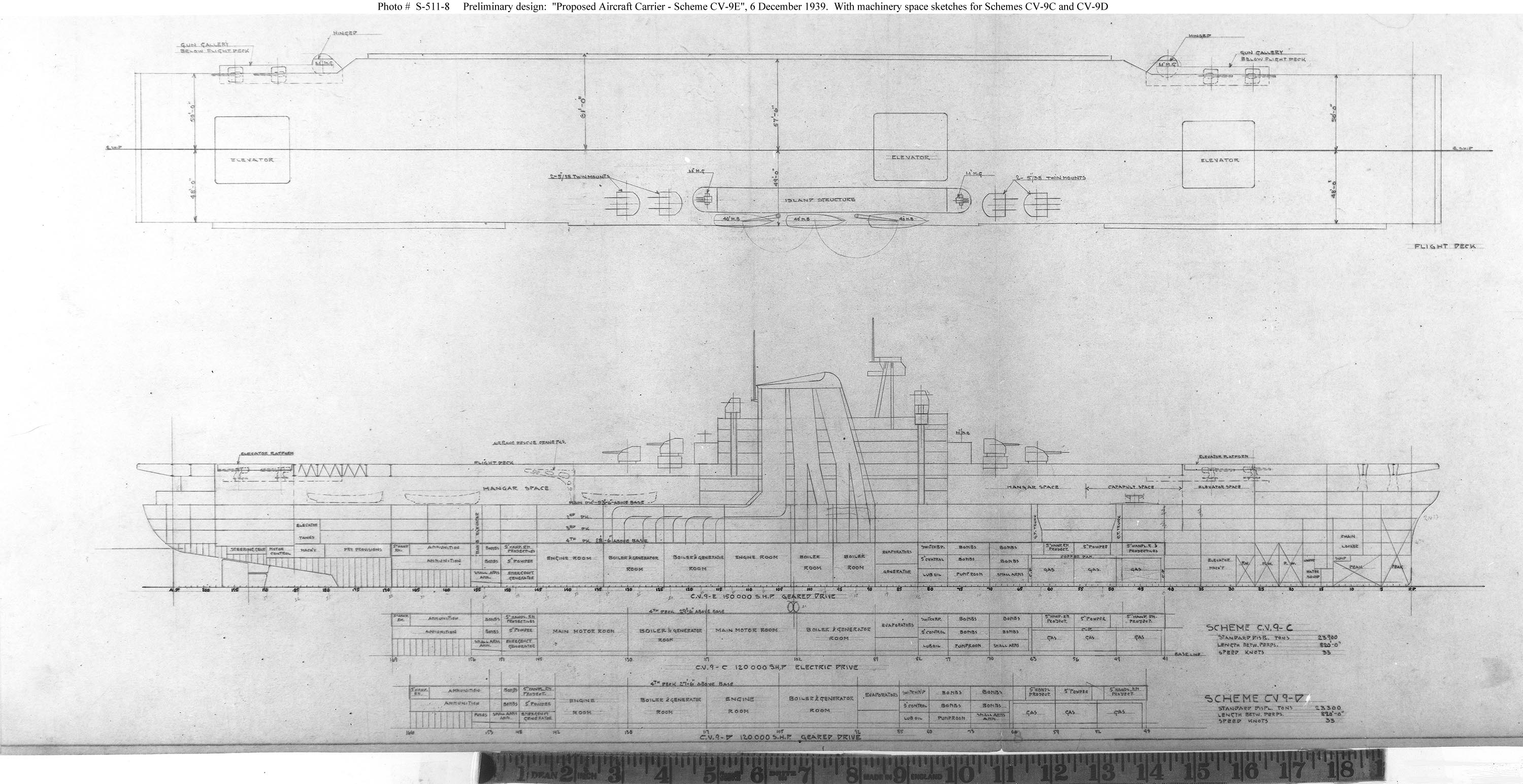

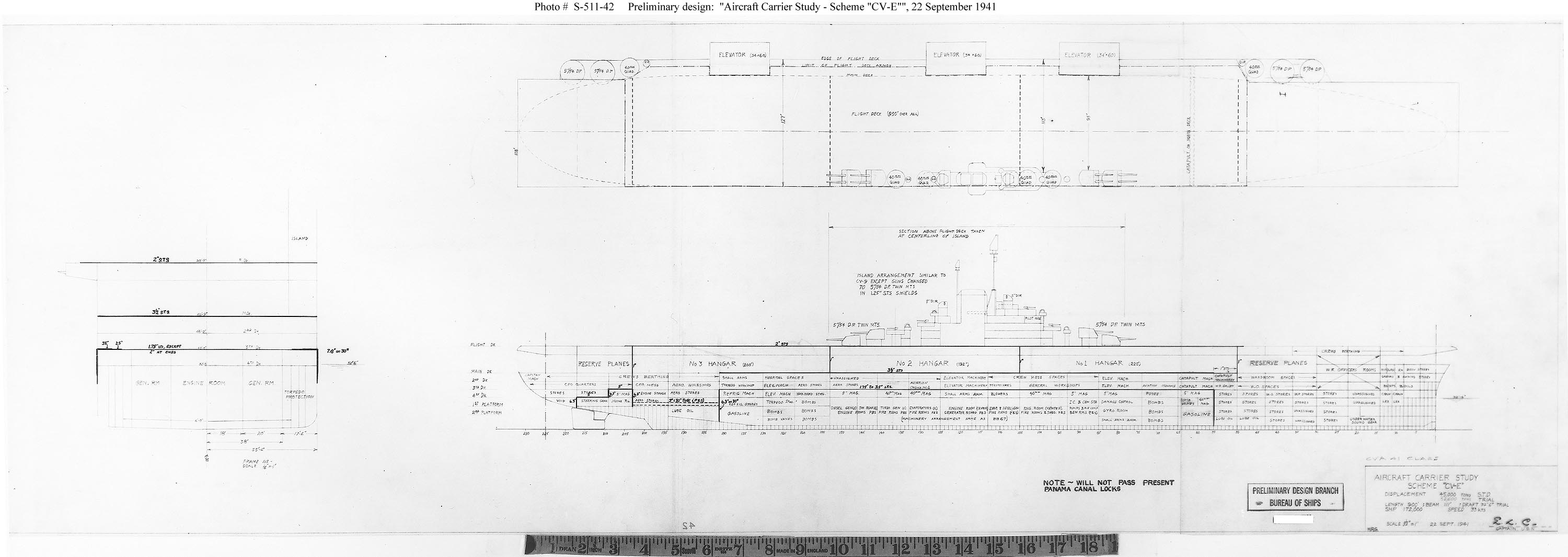

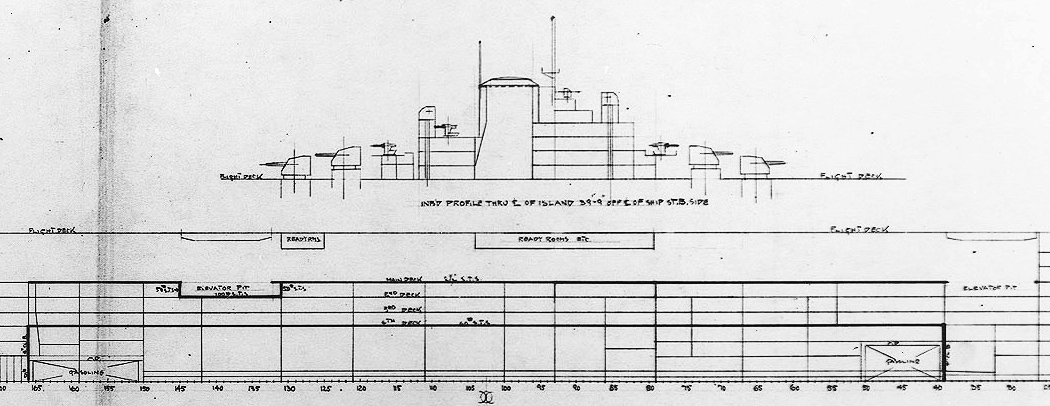

Preliminary design, proposed Scheme CV9E, 6 december 1939. Note the position of the lifts, all centerline, and same size, the combination of island turrets and single mount 5-in/38 in sponsons, and large funnel.

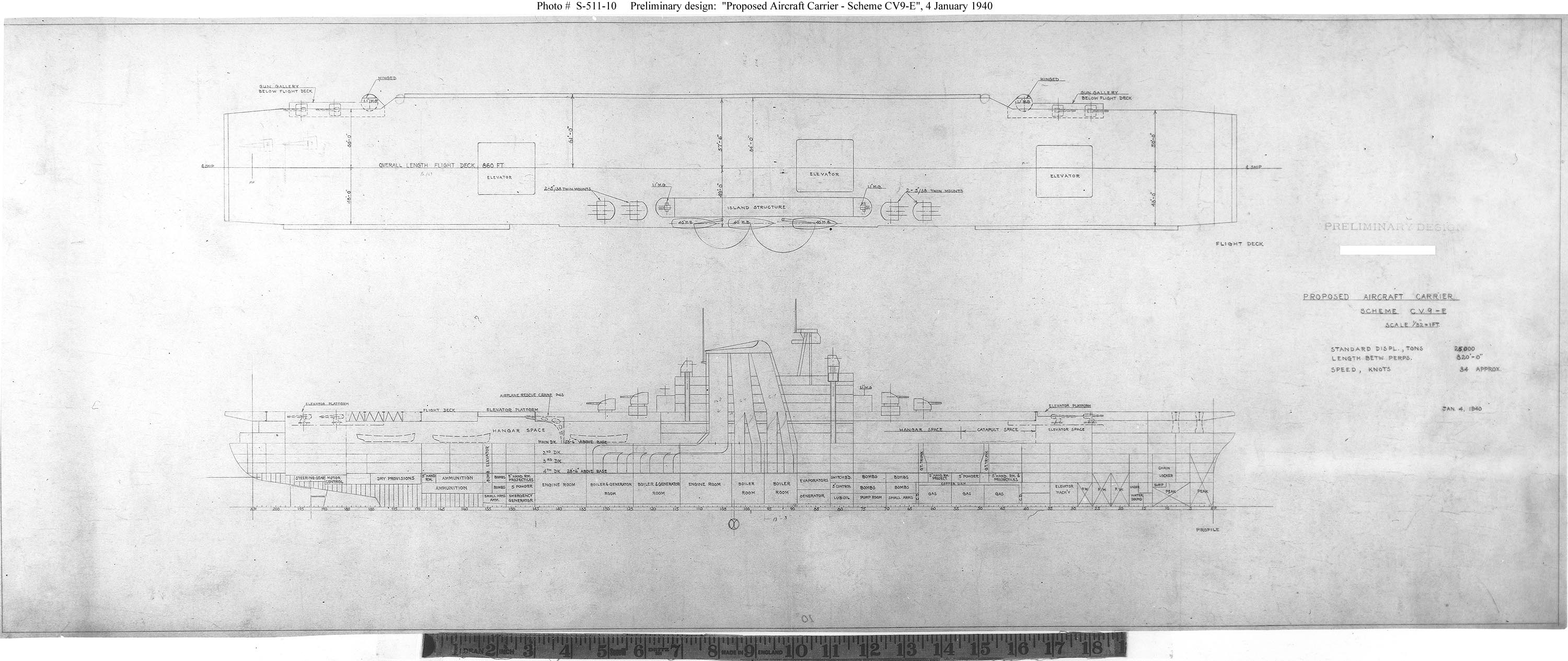

Same, dated 4 January 1940, the lifts are now heavenly spaced on the 860 fts flight deck, and there are towo islands fire positions for quad 1-inch MGs. The fire director tripod is reminiscent from the Yorktown class as well.

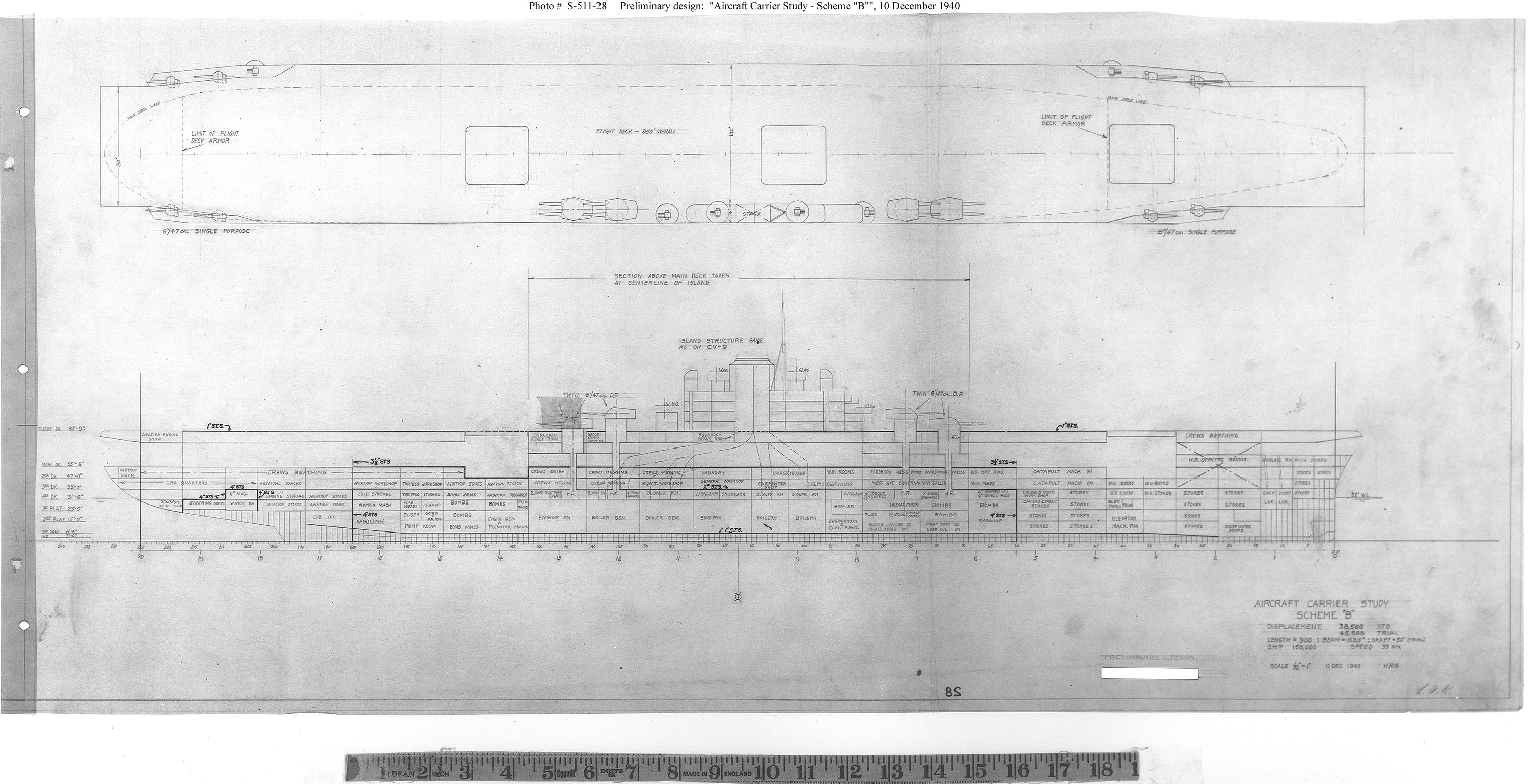

Preliminary design, aircraft carrier study “B”, signed 10 Dec. 1940. The armoured “self protection” alternative project. It Introduces many changes, notably with an all 6-inches/47 guns (sixteen, in four twin turrets and eight pivots, masked singles on sponsons). The funnel is smaller and with rearranged truncated exhausts, an simpler tripod mast. The most striking aspect is about the armour, 3 inches 1/2 of STS steel on the main armor deck/hangar floor, 1-1/2 inch on the flight deck, 4 inches over sensible parts like avgas tanks, steering gear, ammo magazines, creating a citadel starying at waterline level, with a 2-1/2 inches roof and 4 inches bulkheads. The closest the USN went for a semi-armoured aircraft carrier.

The question of whether or not to armoring the flight deck was at the heart of vigorous dicussions. Naval architecture requires to balance metacentric height, that an armoured deck would inevitably compromise. Possible solution was to compensate on the lower hull, using ballasts and bulges, but again, Panama Canal limit prevented additions. The massive armored flight deck and its structural supports needed would also reduce the useable hangar deck space inside.

Despite the US knew about the British bold step with the Illustrious class and its fully armoured hangar (the price of a much smaller air group) decision was made early on NOT to protect the flight dekc but concentrate rather on the lower hangar deck, and fourth deck (above the machinery, tanks and stores) which made better sense, and not sacrificing any of the air group’s full strenght.

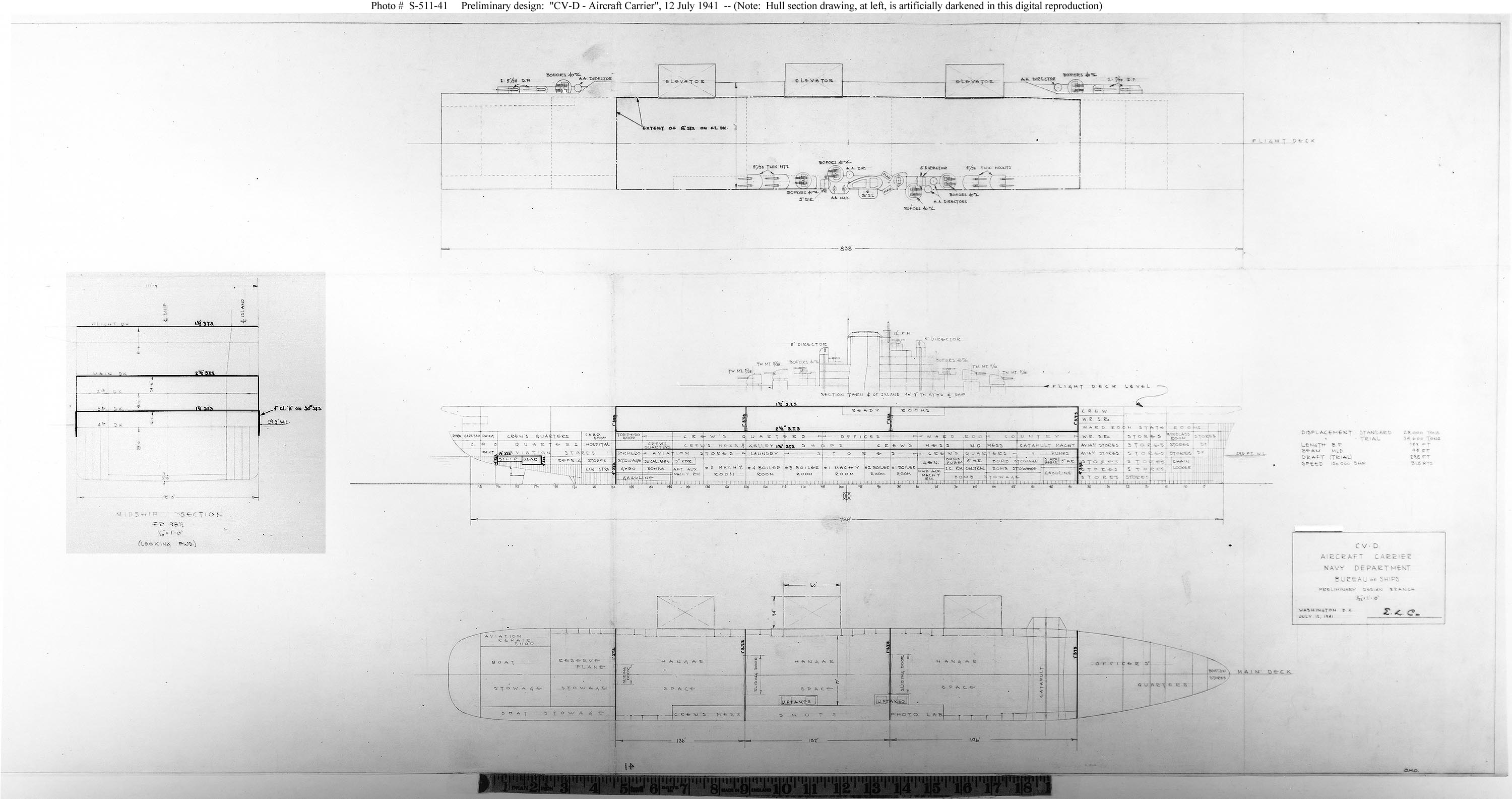

Preliminary BuShip design “CV-D Aircraft Carrier” July, 12 1941. A return to the 4-in/38 armed carrier, but taking in a revised version of the previous armour, this time creating a “armoured hangar” like the Illustrious class, but reduced to 1/2 of the total lenght of the ship, and compartimentalized into three sub-sections. Also there are now three external lifts. Armour is lighter, 1-1/2 inches STS for the flight deck, 1 inches for the bulkheads and subdivisions, 2-1/2 inches for the hangar floor, 1-1/2 inches for the roof of the citadel below (still with 4 inches bulkheads).

In conversations about maximizing the flight deck size, Commander Russell pushed hard for the an all rectangular shape, to the bow. This was part to reach more space for spotting aircraft and giving pilots a full width for take-off, especially when at very end of it. Naval architects of course resisted the idea due to the placement of structural support on the corners, as the hull needed to be at its narrowest.

But it evolved once it was assured the flight deck would not be armored, and Commander Russell pushed architects to come wih a solution. The latter argued a single middle support would fail structurally in heavy seas but the “aeronautic board” convinced them that an occasional buckled deck was worth a safer, larger take-off platform. The rectangular flight deck was eventually approved as well, and the bluckling up in heavy weather was realized through typhoons southeast of Japan in 1945, six carriers suffering that damage as predicted.

CV-E design scheme, 22 September 1941

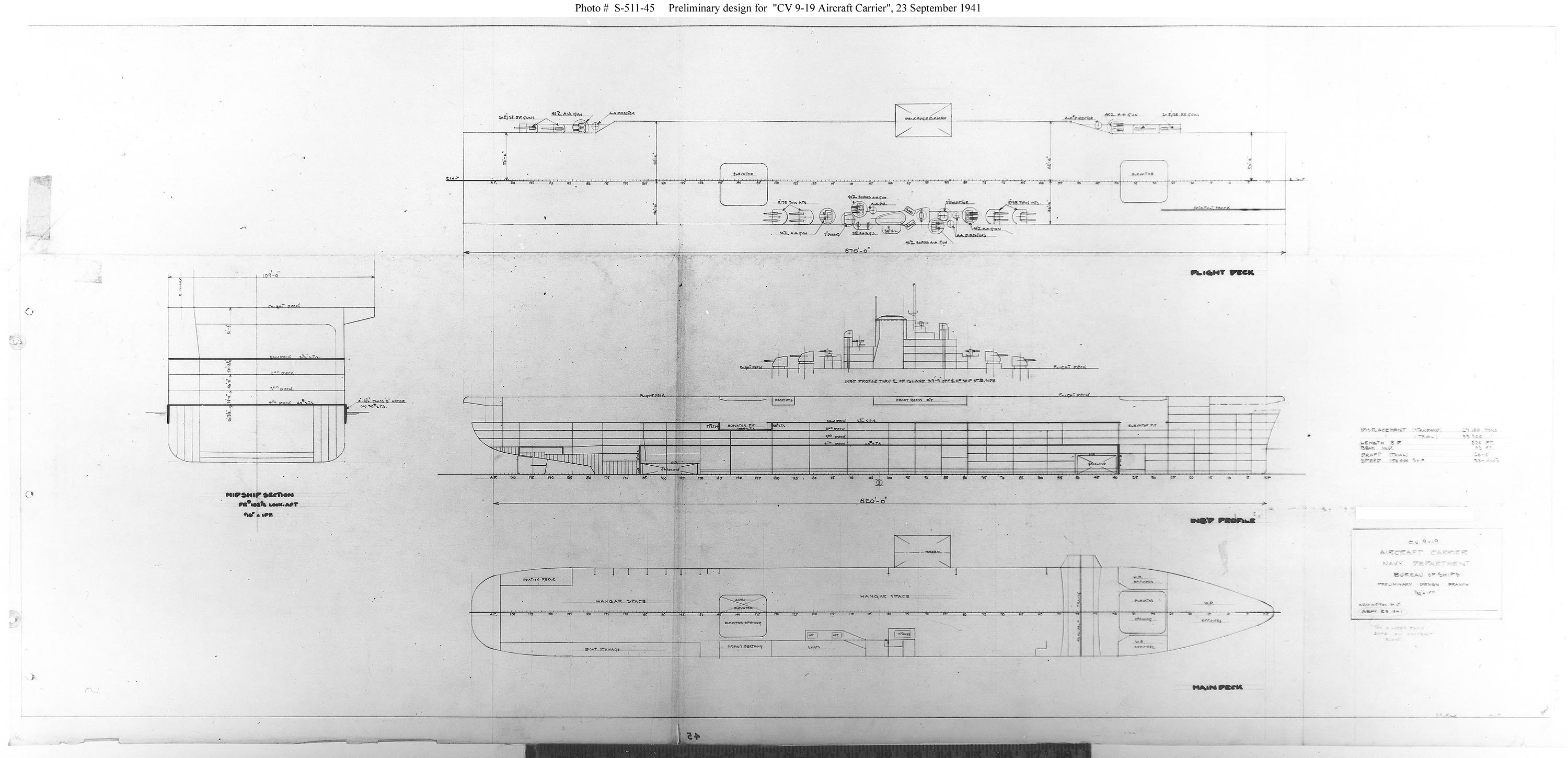

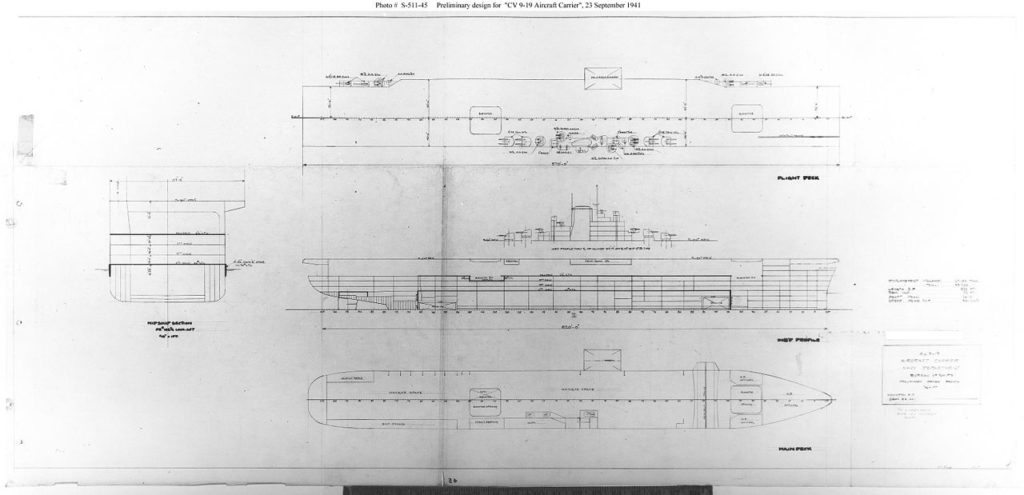

Final, more detailed preliminary design, “C9-19 aircraft carrier”, 23 September 1941. Further work has been made for the hangar armour scheme. It is extended to guarantee a large air group to be protected, into three sub-sectoions, and similar bulkheads as before but a heavier flight deck, 2 inches thick, a,d 3-1/2 inches for the hangar floor/upper armored deck. The citadel below had sloped bulkheads at 6.3° to 20° and ASW bulkhead tubes, still 5-inches over the magazine and steering gear. For the first time future radar positions are shown. It is mentioned the 5-in/54 in twin mounts replace the 5-in/38 encased in 1.25 inches STS armor. Also two internal, one external lift.

Final plan approved for CV-9, September 1941. Very close to the previous scheme, but apparently back to 5-in/38 turrets.

Construction programme

CV-9 was to the prototype for a 27,000-ton of standard displacement aircraft carrier class. It was obviously larger than Yorktown class, yet still smaller than the converted Saratogas, but with a fully dedicated design, authorizing a much larger air rgoup to be carried. This went into two waves of authorizations, when the US were still at peace: CV-9, CV-10 and CV-11 were ordered from Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company on 3 July 1940. Under the terms the new Two-Ocean Navy Act or Vinson-Walsh Act to establish the composition of the Navy and authorize more constructions (June 1940), ten more of the Essex class were programmed, eight ordered on 9 September, CV-12-15 from Newport News, CV-16−19 from Bethlehem Steel’s Fore River Shipyard, then CV-20, CV-21 just eight days after Pearl Harbor, from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and Newport News.

As the US were at war, the Congress appropriated funds for no les than nineteen additional Essex-class carriers, ten in August 1942: CV-31, 33-35 (Brooklyn NyD), CV-32 (Newport News) CV-36 & CV-37 (Philadelphia Navy Yard), CV-38-40 (Norfolk Navy Yard). In June 1943, an extra three was authorized: CV-45 (Philadelphia NyD), CV-46 (Newport News NyD) CV-47 (Fore River Shipyard). In 1944, six more were authorized, CV-50 to CV-55, all cancelled as it was now clear the Pacific war was turning favourably and they were now surplus. Of all those above, only two were completed and trained to be active in WW2, the rest only had a cold war career.

Naming Trivia

The Essex-class carriers confirmed the tendency of naming CVs after historic battles, started with the Lexington class. The first eight however were assigned names from older historic ships (Essex, Bon Homme Richard, Intrepid, Kearsarge, Franklin, Hancock, Randolph, Cabot) and others renamed during construction after losses: USS Lexington (CV-2) at Coral Sea, Yorktown (CV-5) at Midway originally (former Bon Homme Richard) Wasp and Hornet later. Lexington and Yorktown were both historic ships and historic battles.

USS Wasp(ii) was the former Oriskany but replace CV-7 sunk near Guadalcanal, Hornet(ii) the former Kearsarge after CV-8 lost at the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands. Valley Forge was renamed Princeton after the loss of USS Princeton (CVL-23) at Leyte Gulf (October 1944). Ticonderoga and Hancock’s name were swapped under construction due to the John Hancock life insurance company’s massive bond at the condition the ship was under construction in the company’s home state (Massachusetts). USS Shangri-La was another curiosity: Obviously not a historical battle, it came from a facetious remark by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt suggesting that men from the Doolittle Raid flew from the the namesake ficticious Himalayan kingdom based on the bestseller 1933 novel “Lost Horizon” at the time. She was also the last scrapped, in 1988.

The ships never laid down CV-50-55 being canceled, this left nine hull still unfinished in August 1945. Of these, six were completed and two, USS Reprisal and Iwo Jima were scrapped. Oriskany was a bit different as she was the very last laid down and in such an early stage of construction it was decided to take her in hand for radical modifications, making her into a brand new and improved design. So she was completed in 1950 and acted as a prototype to convert the others. With 32 fleet aircraft carriers (considered as capital ships), 26 laid down, 24 commissioned, this still made the USN hhaving arguably the largest of such programs in history.

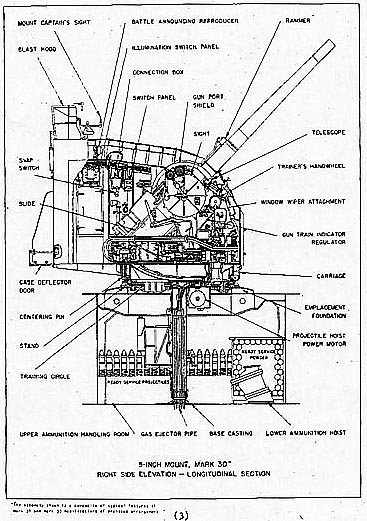

Detailed design

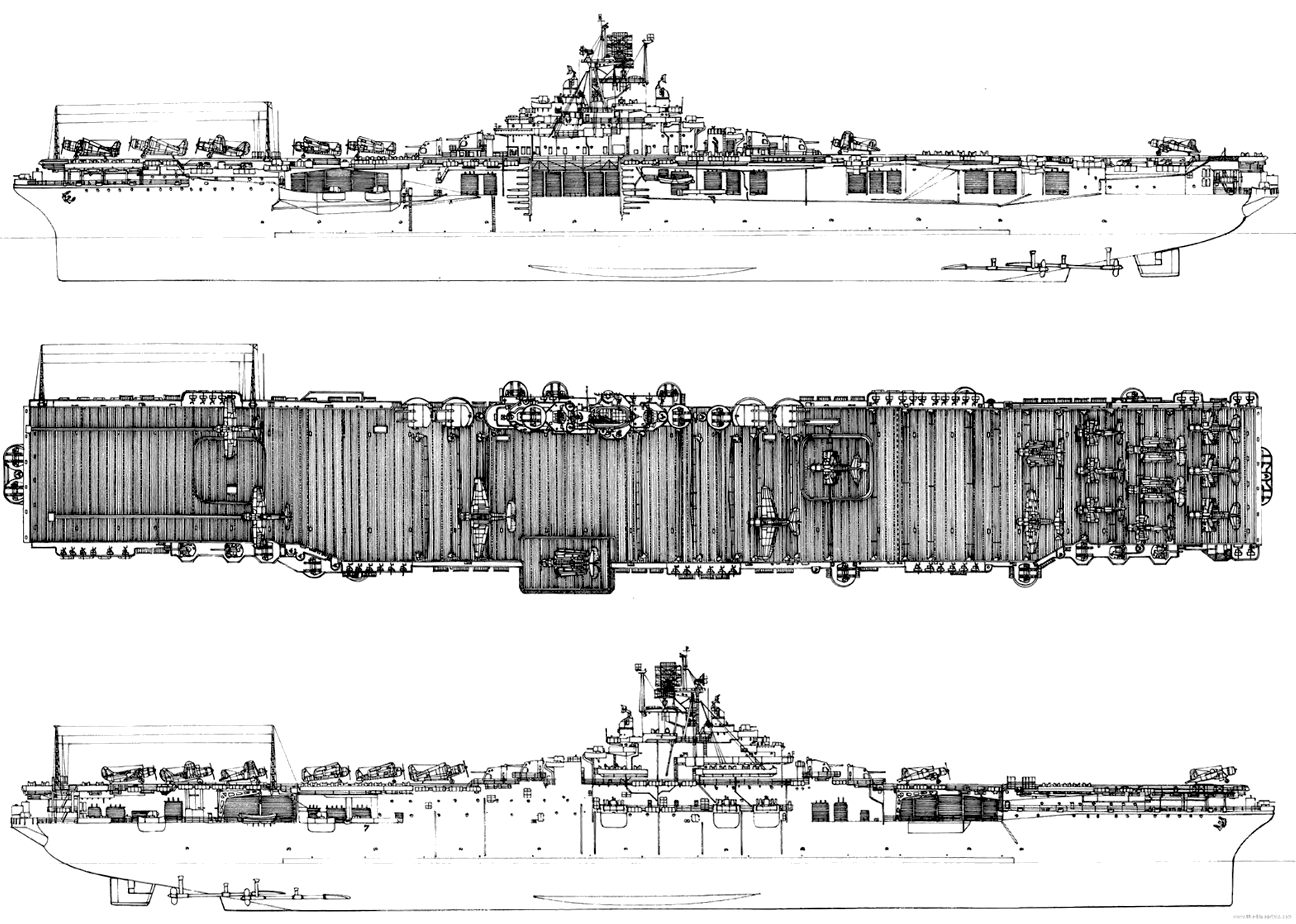

These ships remained very fast, with a large straight wooden flight deck and side lifts, carrying twice as much aviation fuel and ammunition, and an equally larger aviation group of 100 aircrafts. Their main island was pushed, overhanging to the side. The hangar was hardly larger however with a full capacity of 91 aircraft and maximum capacity of 108, including typically 36 fighters, 37 dive bombers dive and 18 torpedo bombers.

Their high pressure boilers turbines developed 150,000 hp for 32.7 knots, better than the Yorktowns but also 10,000 tonnes more in displacement. They were roomy if not comfy for the crews, and had a better protected hangar with two armored decks as well as additional armor over the machinery, tanks and ammunition holds. Finally and above all else, the larger Essex had room for a better AA from the start with a battery of four twin 5-in/38 standard turrets, plus eight quad 40 mm quadruple mounts and around forty six 20 mm Oerlikons “by default”. It was further reinforced for those out in 1944-45, with 18-31 and quadruple 40 mm mounts (up to 124 guns !) and from 61 to 70 of 20 mm, even in twin mounts plus twelve quad Browning .5 cal. (USS Lexington ii.)

Armor design development

On the armour side, debates raged and still went on today among experts and historians about the effect of the strength deck location. British designers looked at the Essex class design and saw the peculiarities of the hangar deck armor inefficient, whereas historians such as D.K. Brown saw the American arrangement superior in many ways. In the late 1930s, the location of the strength deck at hangar deck level reduced topweight and resulted in smaller supporting structures, thus more internal aircraft capacity, for the same displacement.

And so, the first, larger supercarriers necessitated a deeper hull. This shifted the center of gravity and stability lower enough so that the strength deck could be lifted up to the flight deck. This freed US naval architects to move the whole armor scheme higher while still sticking to severe stability specifications, and keeping seaworthiness intact.

“Design 9G” among the developments leading to the final Essex design included an armored flight deck with reduced aircraft capacity at 27,200 tons. It was 1,200 tons more than “Design 9F”, the final one while “9G” was furher developed and became in wartime the development basis for the first true USN armoured carriers, the 45,000-ton Midway class.

Specifications called for the use of Special Treatment Steel (STS) all around, whenever possible also. Armor plating evolved a great deal since the 1860s, and metallurgy science also in the XXth century, notably alloys driven by the need of new aviation materials. This was a new nickel-chromium steel alloy, giving the same protective qualities as “Class B” armor. It was more resistant to splintering and allowed to be used as a full structural plate rather than and add-on for protection (therefore a deadweight). STS became a de facto structural material like no USN ship before, wherever it was desirable, so on hangar deck, fourth deck, pilot house, bulkheads, steering works, magazines and avgas tanks.

Hangar space design & arrangements

As compared to battleship design, the hangar deck became the ship’s main deck, and having a lighter flight deck meant it could be raised a bit higher, allowing to suspend below the roof all needed spare parts and of course having gantry cranes, enough clearing space above folded wings, and enough work space for the crews. Designers included however a kind of half-deck also, Gallery or Mezzanine Deck suspended from beneath the flight deck which were used as aviation squadron ready rooms, plus Combat Information Center (later moved below the armour deck in the “long hull” versions).

The flight deck surface was wooden, as custom practice, notably to avoid excessive metal heat in tropical climates and south pacific waters in general. It was made of teak beams, laid athwartships or crossways, in steel channels. On each twelfth cross-channel, steel tie-down slots were installed to lash down aircraft, crating a spot. These had also the advantage of easy replacement using few tools, having the deck ready for flight operations quicky, something that was praised in 1943-45 after Kamikaze attacks. An armored deck however, would have require shipyard repairs, so keeping the ship longer out of operations.

In the preliminary designs attention was paid at the size of the flight and hangar decks for balanced operations while preserving the maximal air group onboard. Aircraft design went through an incremental storm, more than doubling in weight for far better performances but also much higher landing speeds. Flight decks needed more takeoff space and the fleet carriers to come were all provided even pre-war had flush deck catapults although little actual catapulting drills were don eoutside experimentation.

With the war breaking out, the darwinian imperative of the sky’s mastery saw weight increasing massively, especialy on US planes, with increased armor and armament and larger aircrews. The Grumman TBF behemoth was a spendid example of this upgrade. Compared to the Devastator it replaced, at 5.6 tons empty versus seven tons. By 1945, catapult launches were far more common, some reporting up to 40% launches by that means, notably to allow the fighters, F6F and F4U to act as fighter-bombers, carrying heavy loads.

The hangar area design led to endless discussions and conferences between the naval bureaus, noyably pondering about the size, place and weight of the supporting structures to carry the increased aircraft weight when landing, taxiing or parked, and on the inside, the stringht to support spare fuselages and parts for all planes aboard “under the roof”. The whole was still to provide enough room for all types stored, wings folded, with enough clearance under the tails and wings tips, and a clean working space.

The question of elevators

One particular innovation propoer to USS Essex were a portside deck-edge elevator, in addition to two inboard elevators. This deck-edge elevator proved successful on USS Wasp and soon incorpprated in several preliminary designs. Experiments were made with hauling aircraft by crane also, to a ramp between the hangar and flight decks, but this was way too slow for a realistic deployment. BuShips and the Chief Engineer of A.B.C. Elevator Co. combined their skills to design a better engine for this port side elevator, since it was only supported from one side, taking a massive strain an all bearing and components. Otherwise it was standard in dimensions with 60 by 34 ft (18 by 10 m) in surface.

The two other inboard elevator also traveled vertically with four column bearings, and smaller motor. Engineers made sure to place the elevators as to not creat a large hole in the flight deck when the elevator was in the “down” position. It was a reflection of past uses and a critical factor to stay operable during combat operations. Relocated to the side, it could add its weight to deck operations this time, whateer the aicraft parking and towing on the deck. This side elevator also increased the effective deck space in “up” position, creating an extra parking place out of the flight deck. Its machinery was less complex, with 20% less workload.

Internal accomodations

Compared to the CV-4 class, improvements were made, notably for the ventilation system but also lighting, or trash burner design. They had also better facilities for handling ammunition. Several measures made them safer to manage. The additions of ASW compartiments made for a greater fueling capacity. There was also a much more effective damage control equipment, which benefitted always well trained teams. This was proven at least on two occasions, when ships of the class were seemeingly doomed bt survived thanks to their crew’s damage management, and better equipments.

Despite all these extras raising the tonnage, engineers works out ways to limit weight when possible as well as greatly simplified and streamlined construction for mass production. There was an extensive use of flat and straight metal pieces, as well as intensive use of Special Treatment Steel (STS) (nickel-chrome steel alloy, equal to Class B armor plating), fully structural to save weight.

The initial complement of 215 officers and 2,171 enlisted men without the air group pilots and teams, was well absorbed by the roomy interiors, however, like most USN vessels in 1945 with all additions, this total crew was closer to 4,000. Boat stowage was limited as the ship relied on inflatables stored everytwhere possible. But the few boats were carried on the starboard aft section. The aviation repair workshop was located after the hangar, on the port side.

Aircraft facilities

F6F in the Hangar of USS Yorktown, with bombs being installed by the crew, 1943

Since preliminary design for USS Essex, attention was paid on the size of the flight and hangar decks, taking in account takeoff space, heavier aircraft and the current doctrine of “deck-load strike” (launching as rapidly as possible as many aircraft that can be spotted on the flight deck). Interwar first-line carriers were given flush deck catapults, yet still it was rare. By 1945, catapult launches were far more common as doctrine evolved into the way of using these in coordination with spotted planes behind.

Also the hangar area design and its greater strenght were a prerequisite both to support heavier models’s landing, but also internally to carry 50% of each operational plane spare parts aboard, so 33% of the total carried aircraft, all under the flight deck. And there was to be also a sufficient working space below.

F6F Hangar-catapulted onboard USS Hornet

The portside deck-edge elevator was probably the standardized, greatest innovation of the design, combined to two inboard elevators. Already tested on USS Wasp, it was adopted, located on the port side and offering many advantages as well as being less costly in maintenance than regular inboard elevators, as well as not offering a “gate” inside the hagae to burning fuel, debris, or a bomb.

The external lift, located opposite to the island on the port side, measured 60 by 34 ft (18 by 10 m) in platform surface, with a 18,000 Ibs. capacity. The two inboard elevators were squared (but with rounded corners), both 48′ 3″ x 44′ 3″ with a capacity 28,000lbs due to their sturdier four bearings. One was located forward, offset to the centerline to starboard, close to the catapult. It was basically the “hangar-to-launch” elevator supposing for the lifted plane to be lifted up facing aft, then a 90°turn. The second was located was further aft, also offset to centerline starboard, close to the island’s aft twin 5-in/38 turrets.

There were sixteen Mark 4 hook arrestors for both long and short landings, the idea being to spot as many landed planes as possible in stacked at the front, then middle and aft, and offering more possibilities for a landing plane missing the first cables. In all, the USS Essex was provided circa 30 of these, some alternated with heavy-duty models with twin rollers. There were more than on the Yorktowns, but the novelty was a set of arrestor cables across the bow with a performance specification to conduct flight operations while steaming in reverse, which proved handy after typhoons when ships with bukled-up decks had to recuperate their aircraft.

Two catapults were installed, one H4B starboard forward, close to the elevator and one H4A in the hangar. USS Essex was delivered with none. The quicky transverse catapult inside the hangar was located behind the forward elevator. This was a controversial addition, but coherent with previous ships, concerning the Yorktown, Intrepid, Hornet, Bunker Hill, and Wasp. It was launching on the port side. Still in development in 1941 it was omitted on CV-9 but added to the next batch. Use was limited and they were eventually dismounted ath the first occasion. In 1944, all ships had two H4B catapults forward, one Port and one starboard. The ships also carrier 231,650 Gallons in four separated and well below the hull tanks as well as 625.5 Tons or naval ordnance in well protected stores: 0.5 and 0.3 cal. ammunition, bombs, torpedoes and rockets.

USS Essex refitted to standards in 1944

Protection

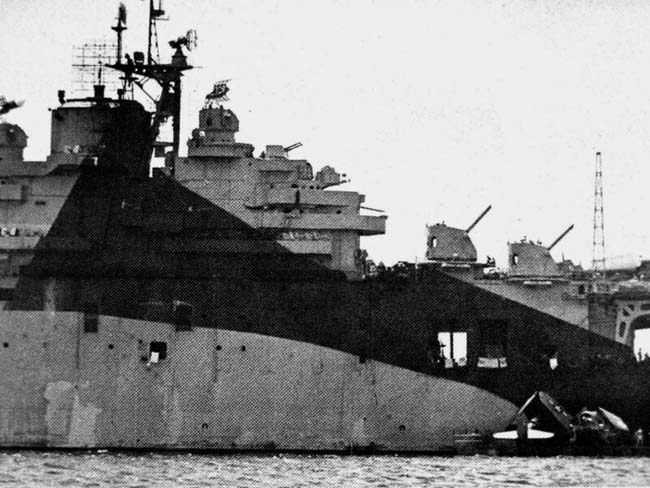

Closup of the preliminary design study

The long discussion leading to the final design secured a compromised protection scheme compared to some of the proposals, notably making them as the first “armoured carriers” of the USN. But as a large air group was the deciding factor, the armour scheme was kept “lighter”, yet still better studied than on the Yorktown class. The large use of STS armor notably as strenght or add-on protection was new.

- Armor Belt: 2.5 to 4 inches (64–102 mm) backed by .75 in (19mm) STS

- Main armor deck: 2.5 in (64 mm) +STS for the hangar deck

- 1.5 in (38 mm) for the STS 4th deck

- 2.5 in STS above the steering gear and aft ammunition magazine.

- ASW compartimentation, longitudinal bulkheads

Preliminary design cut section armour figures

The final September 1941 design showed an “open hangar” without bulkheads, but strenghtened elevator pits, hangar floor, and then a two-level “citadel”, the upper one below the hangar deck comprised four decks with armour, larger at the 4th deck, at waterline level, then a second citadel below with proper bulkheads. The avgaz tanks were located deep down, just behind the aft bulkhead. Another pair of avgaz tanks were situated behind the forward bulkhead. The forward inboard elevator had no armoured pit, as it was situated beyond the hangar armoured deck. Officers quarters and mess were situated alongside and forward.

ASW protection received special attention. There was the usual alternated, compartimented powerplant with all boilers and turbines in their own space, but all the spaces below the waterline had a long-studied, intricated internal design integrating the hull’s outer armor plate. The underwater armor extended 17 feet deep below the waterline, with as specified the capability to resist 500 pounds (230 kg) of TNT. At the time this was not enough for the latest Japanese torpedoes, but at least it was designed to moderate the blast and confine the flooding. There were two outer fuel oil tanks sandwiched with two inner void spaces and the frames staggered to avoid transmitting the blast wave too deeply inside. There was an embryo of concept such as the “raft” created in the 1970s to cancel noise in submarines. Of course, a mandatory triple bottom used against magnetic mines ran for almost all the lenght of the ship.

The thin main flight deck armor prevented widespread damage inthe hangar, but not always. Matters were made complicated by the trajectories of shattered planes destroyed in flight by AA.

On the topic of protection, there was a mix of passive (STS armor) and active measures also concerning the aviation ammunition storage and avgas tanks protection, which also reuired a lot of attention: Contraty to navy “heavy” fuel oil, aviation gasoline or “avgas” was highly volatile. Several features were incorporated to safely handling the 240,000 gallons onboard:

The fuel was spread between three tanks, one centerline, saddle-shaped and on both sides, plus another saddle-shaped alongside both of the other two. This allowed to empty these from the outside toward the middle for stability, as they were gradually filled with seawater for ballast but also acting as protection buffers with the center tank.

-The fuel was not pumped directly to the fight deck or hangar deck. Instea, seawater was pumped into the fuel tanks. As the level rose at the bottom the fuel was floating on top, forced up before delivery. This allowed avgas volatile compound vapors lingering in the hangar, at risk of a single spark, with the adantage of seawater to keep the tank pressure always the same, allowing also to drain the risers and empty the fuel supply system on the hangar deck with less risk in case of a fire.

The need of ventilation, also to avoid these gasoline vapors building up in the hangar was recoignised early enough and adressed in part by not armoring the flight deck, allowing for large openings along the edges of hangar deck that could be closed off when needed with rolling shutters. This feature became life-saving on several occasions during the Kamikaze onslaught in 1944-45.

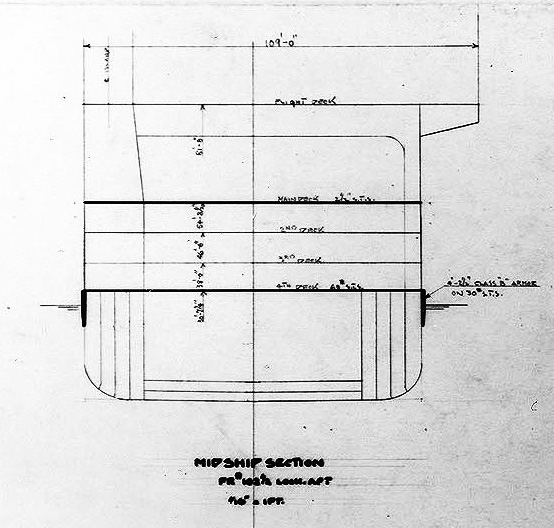

Powerplant

Sailors of an Essex-class carrier cleaning up the propeller at Puget Sound.

While much more powerful than the Yorktown class, the Essex class powerplant was about the same, but upgraded. Indeed, several design innovations were incorporated, with new Steam turbines (chosen over turbo-electric designs) with new gears, placed in four boiler rooms, two engine rooms on the center-line. Each boiler room contained two Babcock and Wilcox boilers.

The four shafts (same four-blade, bronze casted, approx. 12 feets (3.65 meters) in diameter, 27,000 pounds (12,247 kg) propellers*) were driven by four Westinghouse geared turbines, with each paired low-pressure and high-pressure turbines connected to double-reduction gears. They were fed by steam coming from eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers working at 565 psi and 850°F (450°C). The low-pressure turbines were used for cruising, at lower power and shaft revolutions, but bypassed with the steam fed directly to the high-pressure turbine when higher power ws required. This was sufficient for an output, as designed, or 150,000 shp, so far making them the most powerful aircraft carriers until the Midways in 1945.

This compared well to the Yorktown’s 120,000 shp by using Parsons steam turbines coupled with nine B&W boilers. The Essex class boilers were larger and far more efficient, and like in the North Carolina class, the gearing system was brand new and innovative.

Out of it, engineers expected the ships ro reach their design speed of 33 knots (37 mph 60.6 km/h), more than the 32.5 knots of their predecessors. Their large hull was also able to accomodate more oil, enough to reach a Range of 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h) thanks to a total capacity of 4758 tons, up to 6330 tons. This was an impressive autonomy, almost twice as large as for the Yorktown class, allowing them practically to cross half the globe in one go, transiting for example from Pearl Harbor to UK via Panama. They were perfectly fitted for Pacific operations.

However in service it was rather 15,440 Nautical Miles as reported. They were also slower than expected, USS Essex making 32.93kts on Trials, with 154,054 hp measured on a shaft, also on Trials. They were relatively good seaboats, reacting well at the helm due to the size of their sole large rudder, but still, they heeled and lost speed on hard turns, and needed 765 Yards (700 m) at 30 knots to make a full turn, not that bad given their 250 m long hull.

For electrical lighting onboard, they relied on four 1,250kW Ships Service Turbine Generators, and two emergency 250 kW Diesel Generators to avoid being totally “dead in the water”. In theory there were backups for pumps to keep the ship afloat. However between explosions and fires some ships like USS Franklin practically lost all power.

* One of these is on display (U.S.S. Intrepid) at the Hudson River and W. 46th Street.

Armament

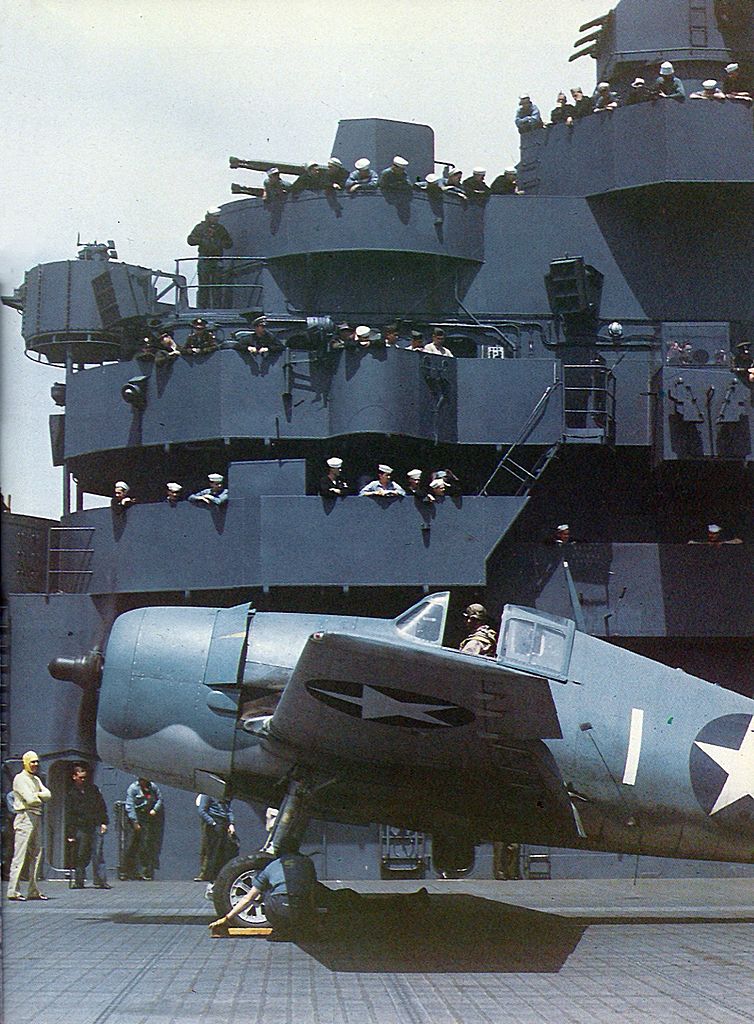

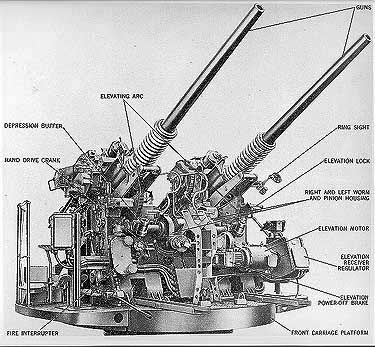

40mm quad watching over parked F6F and TBFs.

The original design planed no less than twelve 5 in/38 caliber gun mounts, four in enclosed twin mounts turrets fore and aft of the island, starboard side, and four single open mounts on the port and starboard corners aft and forward, in sponsons, later reduced to four on the port side only. Both the 40 mm and 20 mm were adopted in the final 1941 design. There was little need of additions in 1944, but the “long hull” at least gave a better arc of fire to the forward quad AA mount.

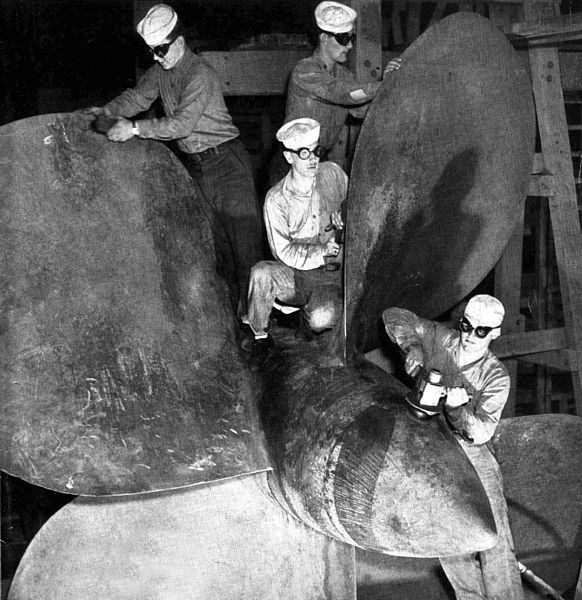

5-inch/38

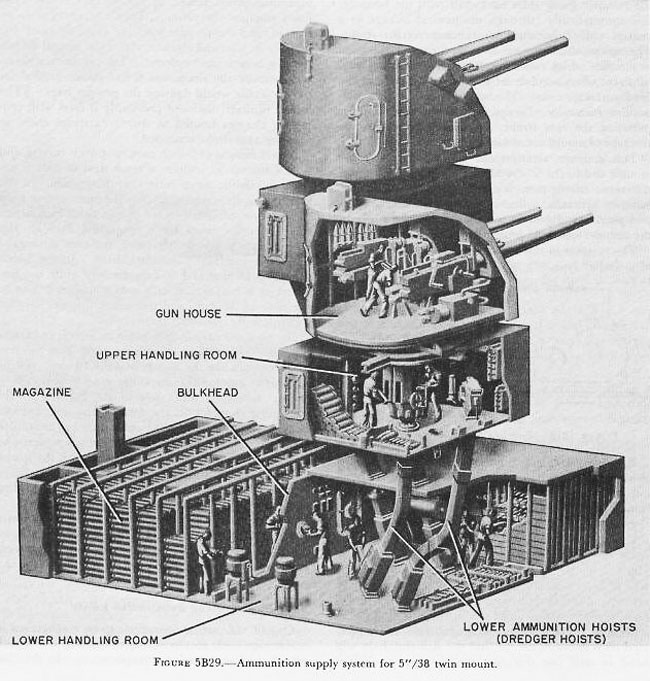

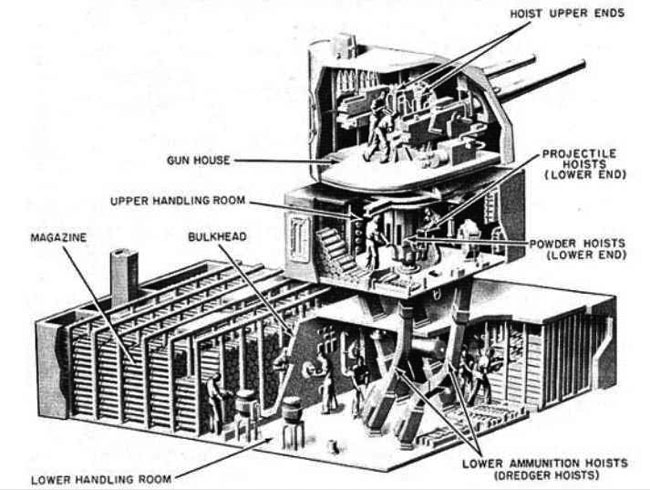

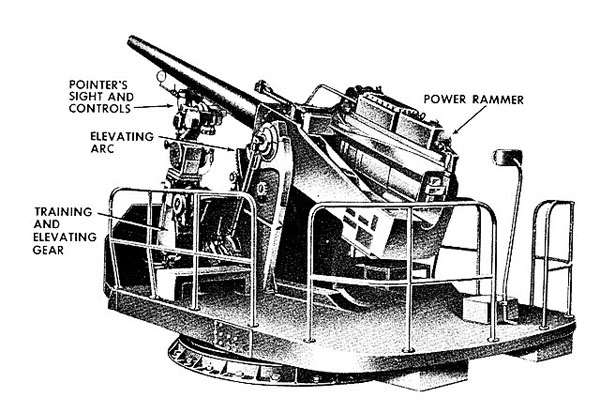

Detailed ONI cutout of the 5-in/38 turret

The ubiquitous 5 inches/38 caliber (127 mm) used by the US Navy. They will be detailed in a dedicated post. These guns had a maximum range of seven miles and a rate of fire of fifteen rounds per minute. The 5-inch guns could fire VT shells, known as proximity fuzed-shells, that would detonate when they came close to an enemy aircraft. The 5-inch guns could also aim into the water, creating waterspouts which could bring down low flying aircraft such as torpedo planes.

Gene Slover’s, US Navy Pages, Naval Ordnance and Gunnery Vol 1 ordnance on the 5-in/38

Several photos and tech views (ONI) of the 5-1/38 in turret and pivot mount.

40 mm/60 mark 1.2 Bofors AA

40 mm Bofors with Mk.12 mount quad in action, USS Hornet.

No less than seventeen quadruple Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns were planned, although designs from 1940 integrated the 1.1 in/75 or 28 mm “chicago piano” quad mount instead. There wre three on eiher side of the island starboard (two aft, one forward), superfiring over the 5-in turrets, another one at the bow, another at the stern, both in the axis with a restrictive arc of fire, two in sponsons aft starboard, and two starboard. The 1.1 were never installed, 40 mm were ready instead, and were a significant improvement over the Lexington and Yorktown classe’s AA armament, which also included 0.5 cal. Browning HMGs. The latter were also planned, even integrated into the tripod platform, but never installed.

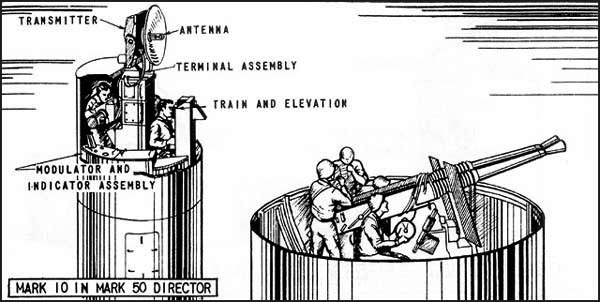

Mk10 radar, 40mm Bofors ONI

20mm/70 Oerlikon Mark 1.2

No less than 65 single Oerlikon 20 mm cannon completed this firepower. They were installed in sponsons alongside the flight deck, the island, fore and aft generally in multiple rows. The largest of these was the starboard aft sponson, behind the N°4 5-in turret and counting ten of these AA guns.

Radars

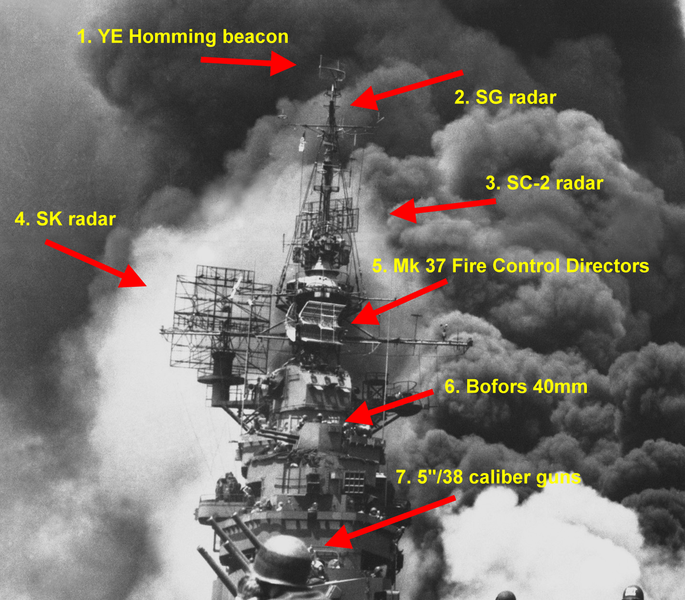

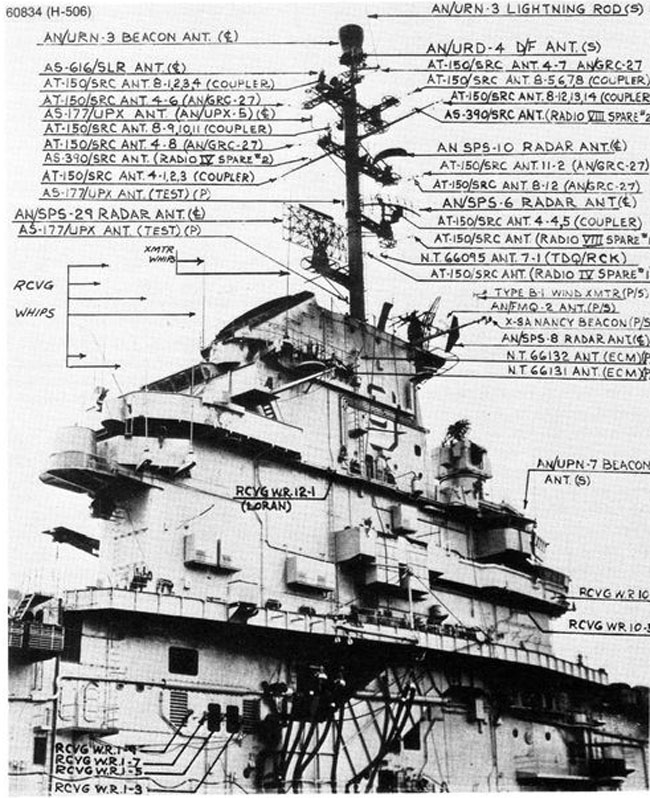

ONI Essex refit close view of the island’s specifics

It is not quite easy to really assess precisely, per ship and date, the electronics suite onboard. Only refits details gave clues. What is certain however, is that all Essex class ships were provided with the latest radars and electonics suite.

USS Essex(CV-9): Had the common SK surveillance radar flatbed antenna, the SC-2, SG radar and two Mk 4 fire control system radars installed atop Mk34 directors fore and aft on the island’s superstructure.

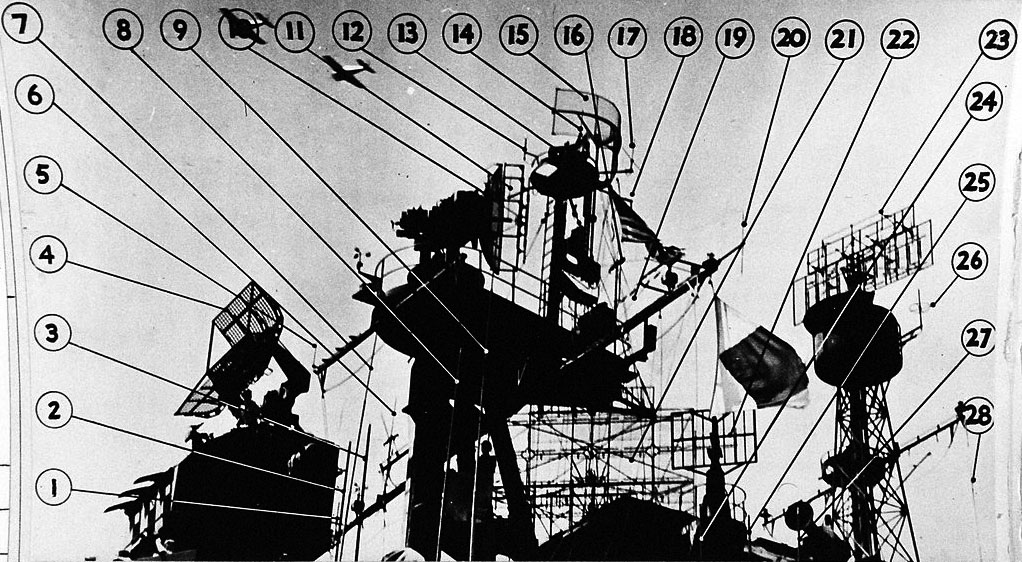

A picture of the antenna arrangement on the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-16) in 1944/45. Following antennae can be identified:

1-3 , 5-9, 11, 14, 16-20, 24, 25, 28, 29: various radio communication aerials;

4: Mk 4 fire control radar on Mk 37 director;

10: SM radar;

11: SO IFF antenna on the SM radar;

12: CPN-6 radar beacon;

13: SG surface-search radar;

15: YE homing beacon;

21: SK-1 air-search radar with BT-5 IFF;

22: homing beacon;

23: SC radar with BT-5 IFF;

26: ABK-7 identification radar.

src: U.S. Navy Naval Aviation News March 1946

SC-2 Radar

A smaller additional radar (15′ x 4’6″ (4.6m by 1.4m)) to the main model, introduced in 1942 and mostly used by destroyers due to its smaller weight. It was so good that it was seen in use until 1963. Same basic set as the SK but smaller antenna composed of 6×2 dipoles. It was lost in altitude resolution but sill had a PPI display and integral IFF. The 1944-45 models had also antijamming features. Its wavelenght was 1.5 m, pulse width 4 microsecond and Pulse Repetition Frequency 60 Hz, its scan rate 5 rpm, and power 20 kW.

Max Range was 80 nautical miles (150 km) to detect a medium bomber, 40 nm (70 km) for a fighter; On sea, it could detect a battleship at 20 nm (40 km) which was close to useless to react due to the gunnery range.

Accuracy was 100 yards/3° (90m) and resolution 1500 feet/10°(460m), altitude accuracy 2000 feet (600m) for a total weight of 3000 lbs (1360 kg). First batch (Mark 2) was completed in December 1943, second in December 1944 (Mark 4). On the Essex-clas it was generally installed on the mainmast while the SK was installed on a side platform overhanging to starboard.

SK Radar

USS Bunker Hill radar suite

The SK radar was a large bedframe style air search radar introduced in 1943 and used on large ships. Essentially an SC-2 radar set, but with a larger antenna fitted with 6×6 dipoles. it could detect a target like a medium bomber at 10,000 feet ceiling and 100 nautical miles distance. Elevation could be estimated from positions of maximum and minimum signal strength, difference of signals between antenna rows. Used an A-scope with 15/75/375 miles range scale, PPI-scope with 20/75/200 range and even IFF Mk.IV, provided by the vertically polarized antenna, atop the main antenna. It was replaced in 1945 by the SK-2, recoignisable to its large parabolic antenna fed by a dipole. The SK was specific to carriers, destroyers and escorts, replacing the 1941 CXAM-1 radar set.

SG Radar

SK Radar and other Essex class island details

A small surface search radar (later SG-1) usually installed on destroyers and CVs as well. Located on the mainmast, it had an A-scope and PPI-scope displays and was able to pick up submarine periscopes at 10,000 yards. 64 km overall range, working at 3000 Mhz, working at 1.3 to 2 µs pulse width. It was introduced in 1942 and produced until late 1943 but served for two decades.

SM Radar

Introduced in late 1943 it was complementary to the SG, a small pole radar combining a flatbed array and parabolic antenna for surface search or a full parabolic model. It was used as a main control radar, and often two were installed to manage the main guns.

SK-2 Radar

Replacement for the SC, it was a lighter but still very large parabolic antenna, main surveillance air and surface radar of the USN, standard in 1944. They were Long Wave Search Sets in the same familiy of the SC and SC-1.

SC-2 Radar

Replacement for the SG in 1944, it had a smaller, lighter and more rectangular bedframe antenna. Also used on destroyers, but present on the axial mainmast onf Essex-class ships commissioned in 1944-45.

CV10, 12, 16, 18 were presuably given the same SK and SC-2, but also the new SG and SM radars as well as two new Mk.12.22 fire control radars.

CV13, 14 and 15, CV19, 20, 31 and 38 were given the 1945 eletronics suite: SK-2 radar (the parabolic one), SC-2, two SG radars, the SM radar, and two Mk 12.22 FCS radars.

CV21, 32, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40, 45, 47 were equipped with the SK-2, the new SR radar, the SG, but also the new SG-6, and a variable number of SP, SX control radars as well as two Mk 12.22, but also two Mk 29, six Mk 39, nine Mk 28 radars and TDY ECM suite all post-war. They were seen in action in Korea and Vietnam.

Accomodations & features

USS Lexington’s Chart Room

USS Lexington’s Helm

CV-16 Combat Information Center in action

Air Group of the Essex class: The “Sunday Punch”

The carriers’ main advantage (informally known as the “Sunday Punch” due to components proportions) was their all-time offensive power comprising 36 fighters, 36 dive bombers, and 18 torpedo bombers as planned, and acted. Only the initial models carried changed: The F4F Wildcat, SBD Dauntless and TBD Devastator initially planned all discarded for the new generation when the ships entered service. On USS Essex, completed in December 1942 (a fiction as we saw already) were supposed to carry two squadrons of F4F Wildcat, two of SB2U Vindicator (even older!) and/or as complement to SBD Dauntless, and SOC Seagull. The old Vindicator was retired in late 1942 and there is no photo or document proof it was used from her flight deck. It is never mentioned for the other carriers of the class.

The case of the Curtiss SOC seagull is more nunanced. This reconnaissance biplane floatplane was recalled after the fail of its designated successor, the Seamew, due to its abysmal performances. It was generally at this point in 1943 often replaced by the kingfisher when available. And it existed with floats or wheeltrain, so perfectly able to operate from the deck as well. It was related to the use of hangar catapults on the Yorktown class, not repeated in the CV-9 design (This transverse hangar-deck catapult was found however in CV-10, 11, 12, 17, 18, and later removed). But again, the complete lack of photo evidence supposed otherwise. Its already more likely for the Kingfisher although, again, there is no photo or data showing this. The transverse catapults were rarely used in practice as it disturbed mooth hangar operations, a main reason for their removal a the first occasion.

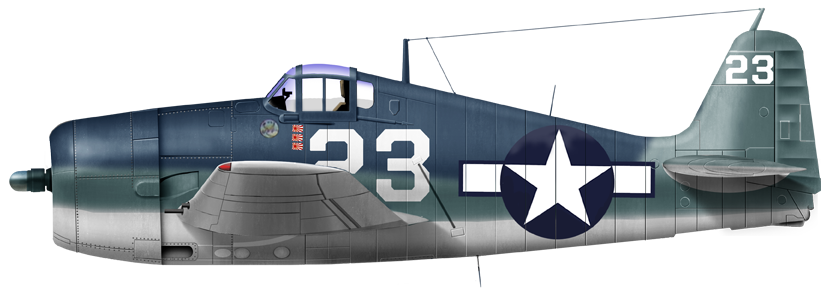

F6F-3, USS Yorktown, 31 August 1943.

-The case of the F4F-3 Wildcat is more interesting. Its designated successor, the F6F was indeed in December 1942 was still not in service, introduced in 1943 an constantly upgraded until November when appeared the F6F-3N night fighter variant. On USS Essex, the first production F6F-3 (R-2800-10engine) which flew on 3 October 1942 reached operational readiness with VF-9 in February 1943. So during her initial post-commission time USS Essex, which was given former USS Ranger’s air group reequipped with the F4F-3 Wildcat in April 1942, but the group was redeployed on USS Essex and only in April 1943 CVG-9 was deployed to the Pacific Fleet, with the F6F and all pilot qualifications made. So, if any indeed operated from USS Essex (again, no photo to back this up) in this transitional phase, it would have been only to test the flight deck and facilities, not in an operational way as the F6F was chosen instead.

Regular air group

Avengers and Hellcats of Carrier Air Group 5 warming up on the flight deck of USS_Yorktown (CV-10) circa late 1943. The Essex class carriers inaugurated the F6F in combat, since USS Essex having them practically at shakedown stage. A marriage made in heaven for the remainder of the war as the plane started to be used massively as fighter-bomber towards the end.

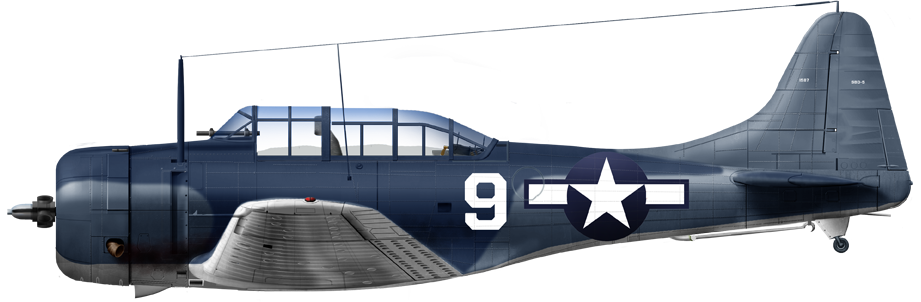

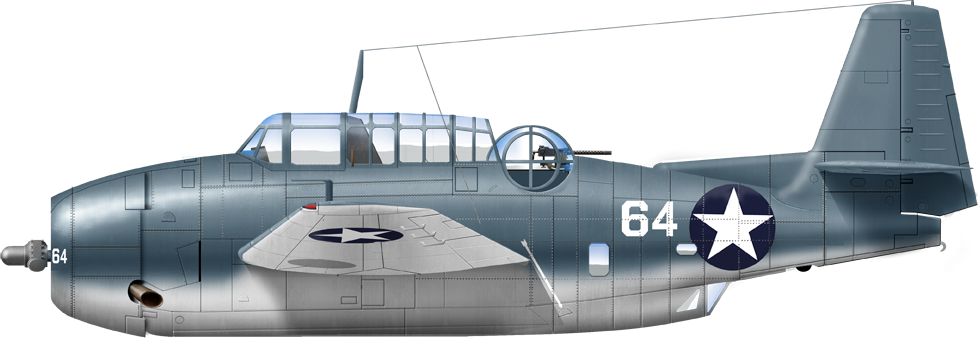

The Grumman F6F Hellcat would be the standard fighter, the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver (at least from early 1944) the standard scout/dive bomber, and the Grumman TBF Avenger its torpedo bomber since the start, also used in other attack roles.

SBD-5, VB-5, CV-10 (USS Yorktown, October 1943). The case of the Douglas SBD Dauntless was another interesting one. This one however is well documented. The Dauntless soldiered on the early Essex class carriers since the Helldiver’s protracted and complicated development dragged on. Dauntless were kept aboard until replaced by the helldiver during replenishment phases or prolongated drydock maintenance/modernization in the US, apparently from early May1944, after the second offensive against Truk. USS Lexington (CV-16) and Yorktown CV-10 used aparently only four SBDs for reconnaissance. The Grumman TBF was used for strikes up to that point. So on some carriers the SBD soldiered for almost one a half year, seeing notably the end of the Solomons campaign and several island-hopping campaigns.

SBD catching wire when landing on USS Essex in 1943.

Grumman F6F Hellcat, VF9, USS Essex 1944. On 30 AUGUST 1943, Task Force 15 (Rear Adm. Charles A.

Pownall in command) with USS Essex (CV 9), Yorktown(CV 10), and Independence (CVL 22), launched nine strike groups in a day-long attack on Japanese installations on Marcus Island in the prototype fast carrier strike. TBF-1

Avengers from Independence sank three small Japanese vessels. This second raid against Marcus marked the first attack by Essex- and Independence-class carriers and the combat debut of the F6F-3 Hellcat. (src).

Grumman TBF Avenger, GGG USS Essex 1944

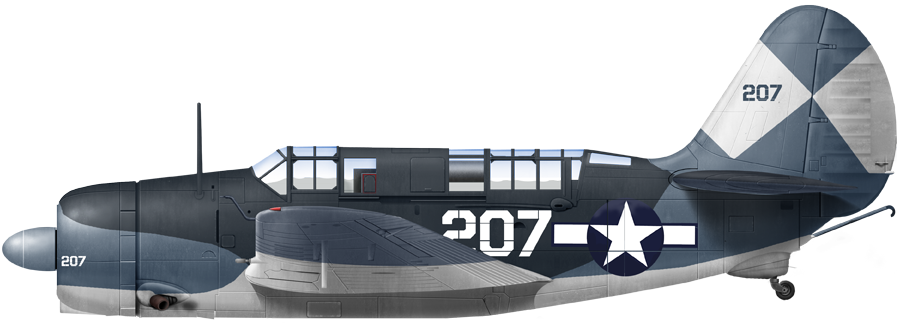

Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, VB-83, USS Essex April 1945

From USS Bunker Hill onwards, the Vought F4U Corsair was introduced into fighter-bomber squadrons (VBFs) as Japanese moslty lost air power at that point. These were the precursors to modern fighter-attack squadrons or VFAs, pioneering doctrine and tactics, and put to good use in Korea. In 1945, all of carrier-based combat aircraft gradually acted as ground attack aircraft, and almost systematicaly mounted underings 5-inch High Velocity Aircraft Rockets (HVARs). They rampaged everything with these, compensating the lack of accuracy by sheer instant firepower on any objective. In the summer of 1945, entire air groups rampaged through industrial areas and ports, but also all remaining shipping over the Japanese home islands.

SNJ AT6-Texan, before first landing on USS Bunker Hill 1943. Upon commissioning, flight decks were tested first by North American AT-6 Texan, the standard advanced trainer of the time.

USS Boxer, launch in 1944

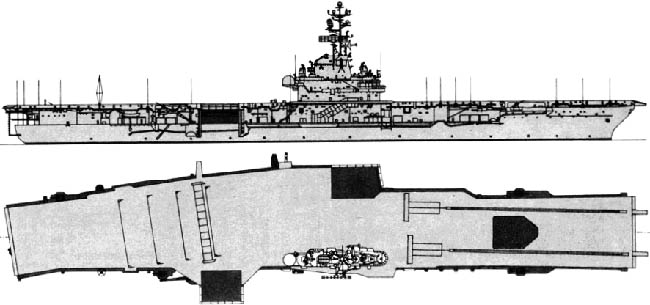

Essex class (1942) specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 265.8 x 28.3/45 x 8.38m (872 ft oa x 147.5 ft oa x 27.4 ft) |

| Displacement | 27,208 long tons standard, 34,881 tons FL |

| Crew | 2862 |

| Propulsion | 4 sets Westinghouse geared steam turbines, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Speed | 150,000 shp, 32.7 kts |

| Range | Oil 4758-6330 tons = 15,440 nm/15 kts |

| Armament | 4×2+4×1 5-in/38 Mk 12, 8×4 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, 46x 20mm/70 Mk 4, 91 aircraft |

| Armor | Belt: 64-102mm (4 in), hangar deck: 64 mm (2.5), main deck: 38 mm (1.5) |

The Ticonderoga “long hull” improvements

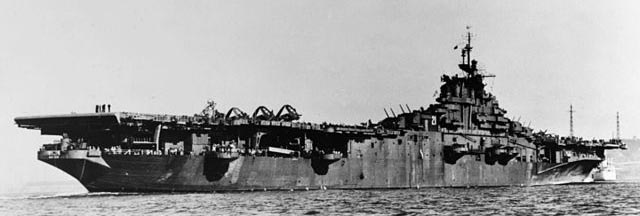

USS Bunker Hill, 1945

Basically, from CV-14 onwards, which inaugurated this new standard, all Essex-class would be fitted with a longer clipper bow, with increased rake and flare, projecting largely forward of the flight deck edge. The main idea was to procure a better arc of fire for the forward quad 40 mm AA but also improve seakeeping, notably for the flight deck.

But this was not limited to this. Addition of AA was considerable, with plans to almost double the initial 1942 design. They notably gained new sponson 40 mm quad mounts, three starboard close to the island, two aft, lower on the hull side, and as much on the port side. They also were given new, more modern electronics suite, notably with the distinctive SK-2 radar. The USN made no distinction, only Historians and specialists. However this became a new standard and some of these changes were incrementally ported on earlier “short-bow” Essex-class ships nearing completion or back in the yard for an overhaul.

To sum it all up:

- Longer bow, about 10 m increase in overall lenght

- Safer ventilation

- Safer aviation-fuel systems

- Combat information center moved below the armored deck

- Addition of a second flight-deck catapult

- Removal of the hangar deck catapult

- 3rd Mk 37 fire-control director

- New radars suite, notably the SK-2 main surveillance radar

- Increased AA, both 40 mm and 20 mm

Simplifications in design were also an ongoing process, as well as building itself: USS Essex for example needed 15 months to be built, versus USS Hornet (ii), just 12 months, but about 20 months to completion, versus 38 for prewar standards. For comparison a modern CV like USS G.Ford needs 48 months from the keel laying to launch. This was still a far cry compared to Vancouver Kaiser’s yards delivering Jeep Carriers at breakneck pace (3 months to launch for the last one, 5 to completion). The Essex class were infinitely more complex in all areas.

Ticonderoga sub-class (1944) specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 270.7m oa (888 feet), same. |

| Crew | 3000+ |

The Oriskany’s complete redesign

On this chapter, the USS Oriskany appeared as a game changer: The name was assigned to CV-18, renamed Wasp so the when CV-34 keel was laid in 1942, the latter unherited it. “Mighty O” was close to cancellation, as she was laid down on 1 May 1944 in New York and launched on 13 October 1945. So at this point the war was over, and she was already surplus. However she was too advanced for simple cancellation and to be scrapped, so as construction was suspended on 22 August 1946, 85% complete, the admiralty wanted to try digested war lessons, and considerably improve upon the design, dating back to late 1940 essentially.

Therefore, USS Oriskany was redesigned, basically as a prototype for further conversions, named as the SCB-27 modernization program (see later). This was started on 8 August 1947, and engineers still needed to tore down the ship down to a 60% completion stage to have more freedom. A lot of her structure was removed, as to make her able to operate the new generation of carrier aircraft, notably jets.

Engineers were acutely aware these new jets and late-gen piston-powered planes needed a longer, roomier and overall much stronger flight deck, as the structure behind. Both was massively reinforced. Also stronger elevators were fitted, as well as new and much more powerful hydraulic catapults. The arresting gear also followed that trend and was heavy-duty.

Also, the island structure was completely rebuilt, taking in account a lot of observations and reports made abour carrier operations management on board.

The island also supported a new generation of radars, for air and surface surveillance, first warning, tracking, and fire control.

USS Essex SBC-27 electronics suite, ONI

The deck anti-aircraft 5-in/38 turrets were removed. It came as no surprise. Basically they were a prewar request due to limited confidence in fighter’s ability to create an efficient defense bubble around a carrier (and not anticipating the heavy support brought by the surrounding ships). Better weaponry was studied which arrived to maturation in between, the last before the missile age. So it reflected a compromise: The ship still retained eight 5-in/38 guns in sponsons, and forteen 20-mm Oerlikon as a “last-ditch reassaurance” in very close quarters, but it was all completed by the latestn radar-assisted twin mount 28 3-inch (7.6 cm) 50 caliber guns that were to replace the Bofors. The deletion of not only these turrets and Bofors mount allowed to keep the deck “clean” with more space alongside the smaller, more compact island.

Blisters were added to the hull (bulges) not to improve ASW defence, but just raise the cross-sectional in order to boost buoyancy and stability (incidentally also making there for a larger fuel aviation bunker volume). On USS Orikany they were required for the simple reason of the addition of much topside weight, due to a completely revamped and wider, heavier flight deck.

3-in/50 twin guns on USS Oriskany – ONI

After all this, USS Oriskany was commissioned in the New York Naval Shipyard, on 25 September 1950. She would not only validates the SBC reconstruction standard soon applied on nearly all Essex-class vessels, but she would also take part in the war in Korea, Vietnam (7 battle stars), decommissioned in 1976 but only stricken in 1989. But instead, she was repossessed by the Navy and eventually ended after a long mothball in the Beaumont Reserve, sunk as an artificial reef on May 17, 2006, the largest ship ever for this purpose.

USS Oriskany in 1990

USS Oriskany (1950) specifications |

|

| Dimensions: Flight deck, long overall | 911 feet (277.7 meters) |

| Dimensions: Flight deck, width overall | 195 feet (59.5 meters) |

| Dimensions: Hull’s largest beam | 106.6 feet (32.5 meters) |

| Dimensions: Draft | 30.8 feet (9.4 meters) |

| Displacement | 44,700 tons full load |

| Crew | Circa 4360 |

| Propulsion | No change |

| Speed | 33 knots |

| Armament | 8x 5-inch (12.7 cm)/38 in sponsons, 14×2 3-inch (7.6 cm)/50, 14x 20mm AA guns |

| Armor | Waterline belt 2.5–4 in (64–102 mm), Deck: 1.5 in (38 mm), Hangar deck: 2.5 in (64 mm), Bulkheads: 4 in (102 mm) |

The Essex class in operations: Organisation, Tactics, Supply/repair

Essex class airstrikes tactics

F4U corsair, back in 1945 on Essex-class carriers for fighter-bomber tasks.

Tactical employment changed as the war progressed. In 1942, the doctrine implied a single CV, or a pair launching an combined air strike. This allowed to keep together a sizeable CAP for close defence. But this was the theory. The pair worked well in that under attack it multiplied the AA protective screen and split the enemy efforts by dispersing the targets. Combat experience however in 1943 hurt this theory enough that noew doctrine were to be tested.

Discussions went on and as the new Essex class were soon available, tactics adapted towards more combined strength. The combined AA fire of the entire task group and their combined screen created a protective umbrella against marauding enemy aircraft. The carriers thus were rarely separated, especially from 1944. The size of the escort grew considerably also, with the delivery of more cruisers and destroyers.

Two or more of task groups supported each other, making by their sum a fast carrier task force. Lessons learned with the operation of a single group of six CV, or split into two groups of three, or three groups of two, helped to test many new tactics which all eventually were codified in task force operation manuals in 1945.

The evolution of the fast carrier task force, combined with preparatory strikes, peripheric strikes to isolate the island targeted, then on-groung close support, combined with a protective CAP, and the cruisers and battleships reconnaissance planes to search beyond radar range, do search and rescue missions, or ASW patrols, were all defined in 1944-45.

The use of radar also considerably shortened the response time to an incoming threat, CAPs being projected in an “inner” and “outer bubble”, one launched far in advance for a long-range interception, the other kept for closer defence, and the combined task force AA being the ultimate “steel wall” at closer range. It should be noted that from late 1943, the Essex-class had a smaller night-fighter CAP with specially trained and equipped F6F Hellcats. It well complemented the first radar warning which worked at all time, day and night.

The fast carrier force organization

“Murderers row”, TF 38 at Ulithi Atoll, 3rd fleet carriers at anchor, 8 December 1944.

By far, of course, TF 38/58 (the name only reflecting a change in leadership), also called the “fast carrier task force” was the pivot of all USN counter-offensives in the Pacific from August 1943, concentrating all Essex-class carriers, which really were its bedrock. At that stage the only aircraft carriers left from the interwar were USS Saratoga and Enterprise, including in this same unit. At its peak in December 1944, it concentrated more combined firepower than any other task force in history, with 17 carriers, 6 battleships, 13 cruisers, 58 destroyers, and a total of 1,100 aircraft, increased for the Battle of Iwo Jima in early 1945. But it was born in August 1943, built around USS Saratoga under the command of Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman.

USS Essex as completed Dec. 1942

USS Essex in the pacific 1943 (world of warships)

Task Force 38 and Task Force 58

TF 38 was really the barinchild of Admiral Mitscher. However the overall command alternated between two Raymond Spruance and William “Bull” Halsey, two very different personalities. Spruance, calculating and cautious, and “Bull” Halsey, far more aggressive and gambling his assets. These were dividing personalities. Officers in general preferred to serve under Spruance while most common sailors preferred Halsey, certainly more accessible. TF 38/58 fell under overall command of Admiral Chester Nimitz.

The name reflected its belongings: With Spruance’s Fifth Fleet, under Mitscher, this was Task Force 58 (6 January 1944). And under Halsey, Third Fleet (Vice Admiral John S. McCain Sr) it became Task Force 38. Planning for upcoming operations was completed when each admiral and staff rotated out of active command, allowing a higher operational tempo and misleading the Japanese into believing naval assets were much greater than in reality. That demoralization however did not bear fruits as much as expected.

Vice Admiral Marc A Mitscher aboard USS Lexington CV-16 June 1944

The Task Force was often split between Task Groups (TG) to simultaneously attack different objectives related to the main one (in general assaulting an island). Their role, before the amphibious fleet was there, was to interdict the sky to the enemy in the while area and destroy all visible installations on the island itself. This traduced into distant sweeps aiming at destroying all surrounding Japanese airfields, notably to ensure no attack will come over the Amphibious fleet when assaulting the beaches.

It was especially vital with the rise of Kamikaze attacks from mid-1944 to mid-1945. The logical conclusion was that when closing with Japan itself, notably for the assault of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima were taken care of by separate TGs. The latter operated still close enough to mutually cover themselves in case of a massive air attack on one or the other TG. This ensure the Task Force to always keep maximum protection and maximum striking power at all times. The main objective of the fast carrier task force was to enable operations for the much larger 3rd or 5th Amphibious Force tasked to provide support to the Marines, and maintained operational at sea by Service Squadrons to resplenish it (see below).

Task Force 38 off the coast of Japan 1945

The first “textbook” operation by TF 38 was Operation Hailstone, a massive combined air strike combined with surface vessels attacks on Truk Lagoon on 17–18 February 1944. This was a crippling defeat for the latter, with the main airfield obliterated, all installations visible in the harbor and around it, and all shipping as well, including many military vessels. With TF 58, the fast carrier force comprised nine CVs and eight CVLs, the latter operating in support, dedicated to the CAPs, leaving the fleet carriers to lead the air strike.

Detailed organization on 1st May 1945

The FIRST CARRIER TASK FORCE, PACIFIC (Com1stCarTaskForPac) was under command of Vice Admiral M. A. Mitscher (30)

The SECOND CARRIER TASK FORCE, PACIFIC (Com2ndCarTaskForPac) was commanded by Vice Admiral J. S. McCain (21).

| CardDiv 1 | R. Adm. F. C. Sherman | CV 9 ESSEX CV 15 RANDOLPH CVL 22 USS INDEPENDENCE CVL 25 COWPENS |

| CardDiv 2 | R. Adm. C. A. F. Sprague | CV 13 FRANKLIN CV 19 HANCOCK CV 38 SHANGRI-LA CVL 30 SAN JACINTO |

| CardDiv 3 | R. Adm. T. L. Sprague | CV 10 YORKTOWN CV 16 LEXINGTON CV 36 ANTIETAM CVL 24 BELLEAU WOOD |

| CardDiv 4 | R. Adm. G. F. Bogan | CV 17 BUNKER HILL CV 11 INTREPID CV 39 LAKE CHAMPLAIN CVL 28 CABOT |

| CardDiv 5 | R. Adm. J. J. Clark | CV 12 HORNET CV 18 WASP CV 21 BOXER CVL 26 MONTEREY |

| CardDiv 6 | R. Adm. A. W. Radford | CV 14 TICONDEROGA CV 20 BENNINGTON CVL 27 LANGLEY CVL 29 BATAAN |

| CardDiv 7 | R. Adm. D. B. Duncan | CV 6 ENTERPRISE CV 31 BON HOMME RICHARD |

CarDiv 11 (based around Saratoga) and CarDiv 12 (around USS Ranger) were both part of the Commander Carrier Training Squadron, Pacific, under R. Adm. R. E. Jennings. USS Enteprise ws the sole interwar aicraft carrier still in active, frontline duty (Carrier Division 7) until 1945.

Supply and repairs- Service Squadron Ten:

USS Essex refuelled at sea underway by USS Tallulah off Luzon, late 1944 (navsource)

Service Squadron 10 comprised hundreds of support vessels which resupplied and maintained TF 38/58.

Alongside the numerous changes of advanced bases for replenishing the ships of TF 38/58, there was a whole organization for the supply chain across the Pacific and back to Pearl Harbor and the homeland, as much as an impressive feat in itself as the rest. It concerned supplies of food, fuel, ammunition and all possible naval and air ordnance, aviation gasoline, navy oil, a galaxy of spare parts, and all in between. Due to the frequency of “supply runs” made by the fast carrier force, this organization comprised all the ships needed to maintain a fleet fully operational far from any base. In 1944 for example, to keep a steady operational pace under halsey, refuelling at sea was pioneered and perfected.

The years of the interwar Navy Bureaus and shipyards believed that a repair ship or tender could provide everything needed beyond minor repairs. but in actual combat, crew’s ingenuity proved time and again, the ships could be maintained at sea and repaired whenever they were, with all the skills necessary to not to sail back home for drydocking. By December 1942 was created the predecessor to Service Squadron Ten, comprising all the ships needed for relatively extensive repairs: They fitted for example USS New Orleans (CA 32) with a temporary bow (made of coconut logs!) after the Battle of Tassafaronga, so she could sail to Australia.

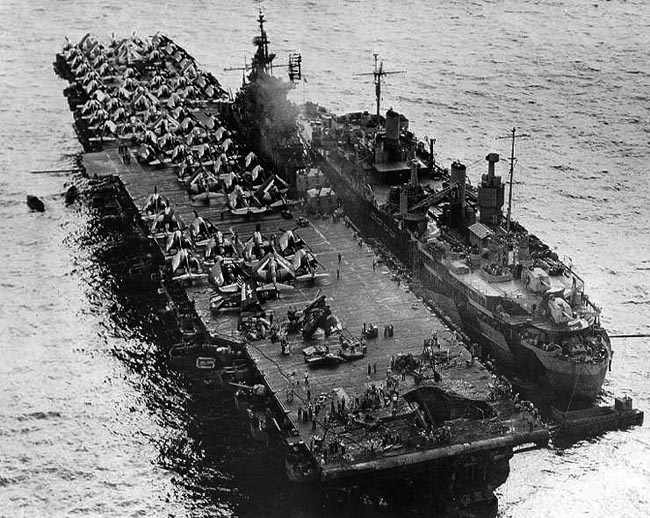

Occurence of ships having their bows blown off, sterns blasted away, massive hull gashes and such a structural mess and internal chaos that all previous expectation fell of battle damage fell short. With a closer, more extensive help, Essx-class ships could remain at sea as long as possible, before completing if needed the task in Pearl Harbor, and then Home for the most serious devastation. It was only a matter of local capabilities. The effort of the crews of all these specialized ships is as heroic in their efforts as any servicemen. Service Squadron Ten notably, attached to T38/58 enabled the it to keep “ressurecting ships” the Japanese believed and announced sunk, time and again.

USS Randolph under repair, Ulithi 1945

Squadron Ten comprised a fleet of floating drydocks, repair ships, tenders, crane barges and auxiliaries, allowing them to perform all major repairs needed to battle damaged Essex-class aircraft carriers. Floating drydocks in particular, large enough to accomodate a battleship, proven absolutely critical in restoring these to seaworthy and operative conditions. By February 1945, for example a superb demonsratin of the collective skill and knowhow of this was performed when repairing for example 60 feet of flight deck on USS Randolph (in 18 days !), creating a new bow, replacing guns, electrical equipment burned by fire, even structural beaming. In February 1945 alone, some 52 USN vessels were repaired in floating drydocks. Randolph repairs at sea would remain at the pinnacle of the genre in US history, allowing the ship to sray on duty insetead of departing for a long trip and much longer repairs at home which would have retired her from operations until the end of the war.

SBC-27/125 cold war reconstructions

USS Philippine Sea July 1955

Note: This post is split in two, the cold war SBC-27 and career will be seen separately in 2022. The following career focus here on WW2 and the years preceding their reconstruction.

The term “SCB” refers to “Ship Characteristics Board (Program)”.

Foreworld

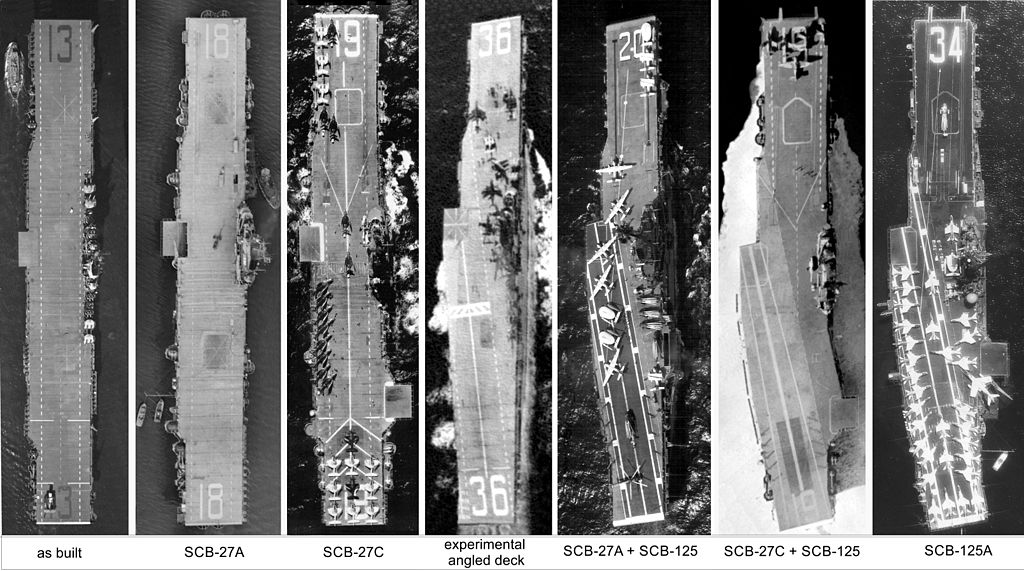

The range of modernizations of the class in the post-war era, exemplified by their flying deck

The construction of the Essex-class aicraft carrier, as well as other mass-built ships for the USN during the war led in 1947 to an assessment of what was to be mothballed and kept in reserve afterwards. The need of the USN gradually decreased in the peace time context, and gradually all carriers, after some service notably for veteran repatriations in 1946 were placed in decommission and reserved in the Atlantic and Pacific. In June 1950 however, the Korean war started and in addition to all Essex-class vessels still in operation, it was chosen to reactivate many of those in mothballed. Since aviation and radar technology made headway in between, it was assessed what ships would be taken in hands to be converted. Most were, the only exception would be the most battered carriers in 1945 like Randolph and Franklin.

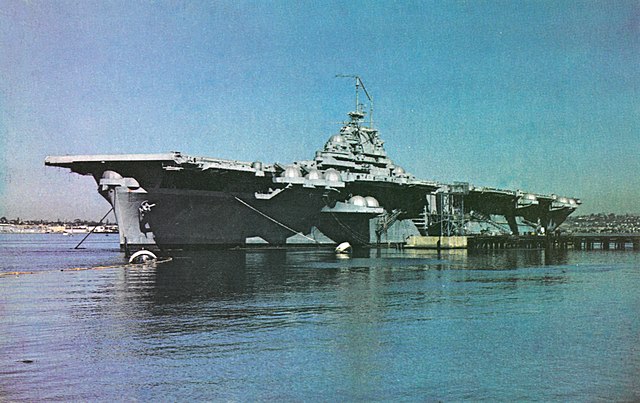

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) moored at San Diego, 1970.

It was soon assessed that the spacious hangars could accommodate jets, but still various modifications were necessary to significantly improve the capability of the ships to handle these heavier, faster jets. Among the modifications detailed for the Oriskany, only SBC-27 carrier, the improvements included for the first time jet-blast deflectors (JBDs), a optical landing system (a British wartime innovation) but also greater aviation fuel capacity thanks to the additional hull bulges and the new angled flight deck really separating and better managing landing and launching aircraft operations. This was the only way to make due with a fundamentally limited flight deck, both in lenght and width. It really became the bedrock of cold war carrier operations at large as the system is always the same as of today, the flight deck only getting wider in proportion (double), with side lifts.

The navy could work with 15 ships, extra ones being deleted due to exetensive wartime damage. These mostly ten short-hulls, along with five long-hulls. The last nine completed stayed as they were in complement to the three Midways. Together they really became the backbone of the post-war US Navy’s combat strength, so they was no rush before laying down the keel of a new generation of “supercarriers” completely tailored to operate jets long-term: The 1954 Forrestal class.

The Truman administration poswar economies sent three active and umodified Essex class into mothballs in 1949, but most were recommissioned after the Korean War start and the ten short-hulls and thirteen long-hulls saw active Cold War service, as eight SBC-27A, and six SBC-27C plus USS Oriskany (total 15). The last six received a second modernization wave called SBC-125/125A and other went into this upgrade later as well, in all, all but one in fact, the last recommissioned in 1958 (see later for further details).

![]()

USS Ticonderoga (CV-14) through Sunds Strait, 24 April 1971.

USS Oriskany was really the prototype for all these changes, and a first batch of eight earlier ships were rebuilt to the Oriskany design standard (SCB-27A program) in the early 1950s, then six more to the 27C design, differing by their catapults mostly. The USS Antietam, “in her juice” still when rebuilt in 1952, received an experimental 10.5-degree angled deck, which really was groundbreaking at the time. She also was fitted with and enclosed “hurricane bow” (no longer separated bow and flight deck lip), both distinctive features of the new SCB-125 program, undertaken at first concurrently with the last three 27C conversions. It was applied to the 27A /27C but USS Lake Champlain. USS Shangri-La also became the first operational angled deck aircraft carrier in operations in 1955, Oriskany ironically was the last angled-deck conversion, leading to a rather unique SCB-125A refit, consiting in bringing her to the both the 27C standard and 125 standard, with an aluminum flight deck to keep the weight down.

The Korean War saw the deployment of mostly unconverted carriers, notably “expending” the battered Bunker Hill and Franklin. From 1955 seven unconverted Essex class vessels were converted as a cost-saving measure to anti-submarine warfare carrier (CVS). Also when the Forrestal-class entered service, eight SBC-27A converted shios were redesignated CVS in turn, taking the rol of the unconverted ships, soon mothballed. Also, two 27C conversions became CVS also in 1962, and two again in 1969.

SCB-144 program: The kast upgrade they received was a bow-mounted SQS-23 sonar. The admiralty waited until there were a sufficient number of serviceable supercarriers to have them decommissioned, from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. The very last active ship was USS Lexington, still in 1991 a training ship. Four were ultiately preserved as museums (see below). The “prototype” USS Oriskany was studied for a possible conversion and the Reagan administation contemplated another wave of modernization that woul be applied to all the remaining vessels still not broken up. But that plan was eventually scrapped. Their design, more than 40 years old, was now showing.

SBC conversions in detail

USS Essex mothballed at Puget Sound Shipyard, 1948

Popularly known in the navy as the “Two Seven-Alpha” or “Two Seven-Charlie” it really saved the whole Essex class from the scrapyard, also ensuring the best use of taxpayers money in a peace time context where the cold war was getting “hotter” several times. All in all, this endeavour, still costly, but less than building new carriers from scratch, allowed the fleet to keep a disposable stock of aircraft-carrying multipurpose platforms. They had well-understood limits, notably they only could operate first-gen jets, but not the heavier next ones for which the “super-carrier” fleet was created.

SBC-27:

The sum of modifications made on USS Oriskany, namely:

1-Flight deck structure significantly reinforced to handle 52,000 pounds (23,587 kg) planes(*)

2-Stronger, larger elevators

3-Standard, but improved hydraulic catapults)

4-Mk 5 arresting gear

5-Removal of 5-in/38 turret, all 40 mm, most 20 mm guns.

6-Eight Twin 3-inch/50 gun mounts installed with prox. fuses

7-Same new clipper bow for all ships

8-New bridge island taller, but more compact

9-Brand new electronics and radar suite

10-Ready rooms (gallery deck) moved to below the armored hangar deck

11-Large escalator starboard side amidships for flight crews up

12-Aviation fuel capacity increased to 300,000 US gallons

13-Pumping cap. to 50 US gallons (189.3 L)/minute

14-Two emergency fire and splinter bulkheads

15-Fog/foam firefighting system

16-Improved water curtains + cupronickel fire main

17-Improved electrical generating power

18-Improved weapons stowage and handling facilities

19-Removal of the armor belt

20-Fitting of blisters, 8-10 feet (2.4-3.0 m) width increase

*The twin-prop North American AJ Savage as given as an example, and this allowed to carry also later the Tracker, but also the Skywarrior and F-8 crusader fighter, while they even operated in the 1970s the modern A7 Corsair II.

SBC-27A

1-All SBC-27 modifications (two years conversion)

2-New H 8 slotted-tube hydraulic catapults

SBC-27C

1-New C 11 steam catapults

2-Wider bulging abeam (103 feet)

3-Jet blast deflectors

4-Deck cooling

5-Fuel blending facilities

6-Emergency recovery barrier

7-Storage and handling for nuclear weapons

8-No.3 elevator to the starboard deck edge

SBC-125

1-New Angled deck (later ported to SBC-27C ships)

2-Enclosed hurricane bow

3-More powerful C 11-1 steam catapults

4-Addition of aluminum flight-deck cladding

5-Mk 7-1 arresting gear

6-Mirror landing system

7-Primary Flight Control moved to aft end of island

8-Air conditioning

9-No.1 elevator lengthened (for SCB-27C)

10-No.3 (aft) elevator moved starboard deck edge (SCB-27A)

Later Air Groups:

![]()

CVW-19 ticonderoga air group, 1970

These will be seen much in detail in the future SBC-conversion/Cold war Essex-class page. The Essex class after the war operated virtually nearly all planes and jets types of the 1950s-60s but the heaviest, which became the norm in the mid-1960s and confined to super-carriers. Instead, they continually operated models such as the piston-planes Skyraider and A4 Skyhawk in Vietnam, all and types of helicopters. In between, they operated the F7F Tigercat, FR Fireball and F8F Bearcat from 1945, F2H Banshee, F9F Panther, F6U Pirate, F3D Skyknight during the Korean war, the TBM-3S Avenger, AF Guardian, D-W Skyraider, F9F-P Cougar, TBM-3R Avenger, HUK Huskee, HUP, HO4S/5S/HRS Chickasaw helicopters after it, and in the early 1960s, the F3D Skyknight, F9F Cougar, FJ Fury, F7U Cutlass fighters, AU Corsair, AD Skyraider, AJ Savage attackers, HUK Huskee, HSS Seabat/HUS Seahorse helicopters (also in the SCB-125/SCB-125A) which saw action in Vietnam. The very last LPH conversions of the late 1960s-early 1970s carried typically 30 to 40 helicopters (HUP, HO4S/HRS Chickasaw, HO5S, HUS Seahorse, HR2S Mojave).

The Essex clas now: Four Museum ships

Four Essex-class ships were preserved, reconsitioned and opened to the public as museums ships at New York City, in texas, California, and South Carolina, so covering three cardinal points on the east coast (2) gulf of Mexico (1) and west coast (1), later joined by USS Midway at San Diego.

USS Lexington (Corpus Christi, California)

USS Lexington at Corpus Christi, CA.

USS Intrepid, New York.

USS Intrepid museum (panoramic), NYC.

A well-known and appreciated rendez-vous point for history buffs and tourists in NyC. It present on the flight deck all types of aircraft in the USN and many more.

USS Yorktown (Patriot’s Point, South Carolina)

USS Yorktown could be visited today at Patriot’s Point, Mount Pleasant, in South Carolina.

USS Hornet, Alameda

USS Hornet amchored in Alameda, California

Overall, the seventeen Essex class commissioned before V-Day and fourteen deployed in combat operations played a very large part in the victory in the Pacific, redefining the capital ship concept for the decades to come (and it’s still central today). Collectively, the Essex-class ships amassed 88 battle stars despite their entry somewhat “late” in operations. The absolute record-holder would ever be USS Enteprise and its unsurpassed 20 battle stars.

The following career list excludes aircraft carriers commissioned after the end of WW2: USS Princeton (CV-37, commissioned 18 November 1945), USS Tarawa (CV-40, 8 December 1945), USS Kearsage (CV-33) (March 1946), USS Leyte (CV-32, 11 April),USS Philippine Sea (CV-47, 11 May 1946), USS Valley Forge (CV-45, 21 November, USS Oriskany (CV-34, 25 September 1950) rebuilt and modernized before commission.

USS Essex (CV-9)

USS Essex (CV-9)

USS Essex CV-9 leaving San Francisco on 15 April 1944

USS Essex was the first aircraft carrier of the famous class to be completed, on 31 December 1942, symbolic date that was pushed up artificially as she had been launched in July, so barely six months had passed since. For such complex ship, especially the lead vessel of a new and important, large and very complex class, that was unrealistic on a technical standpoint, only symbolic. Indeed, she made quick yard trials, which showed she needed many fixes, masking the fact she was bearly fit for service. Under her new captain, the crew trained in February-March, she made her shakedown cruise and although officially commissioned much earlier it was around April that she was ready for service and ordered to the pacific in May 1943.