The legendary 16:1 navy butcher bird

The Grumman Hellcat would be forever associated with the second phase of the Pacific war. It replaced the hard-pressed F4F Wildcat on board all USN fleet carriers (the F4F would continue operating on escort carriers until 1945), and between the experience of veterans transitioning on this new model and the lack thereof on the Japanese side, explains in large part the impressive tally reached by this model, which was unprecedented.

By looking at it first, the F6F had however none of the good-looking grace the best fighters of WW2 are generally associated with. It was a barrel-like, brutish, massive and heavy, miles aways from the angelic Spitfire, the slender Mustang, or even the graceful zero. A dogfight between the two was like a ballerina versus a heavyweight boxer. But it was beloved by its pilot for its raw, unalterated power, firepower, reliability and amazing ruggedness, as befitting to to a Navy Fighter, accustomed to the tremendous forces of a deck landing.

Compared to the Mitsubishi A5M-4 and A5M-5, still lacking protection, it became a “butcher bird”, able to take a lot of punishement before tearing apart its opponent by volleys of its six heavy machine guns. Not only the Hellcat absolutely dominated the Zero, often piloted by Rookies from mid-1944, but also everything flying over the Pacific, from the IJA or IJN. Some fighters were a match in agility and speed, but none was that solidy built.

New York’s company funded by Leroy Grumman had created a world-best naval fighter, ideal for its time. The Hellcat in 1945 operated more and more in a fighter-bomber role, loaded with rockets, in company of the legendary F4U Corsair, and went on during the Indochina and Korean wars of the 1950s. Although replaced by the smaller, but faster F8F Bearcat on CV decks, they nevertheless soldiered on until the early 1960s.

The 1938 naval fighter plan

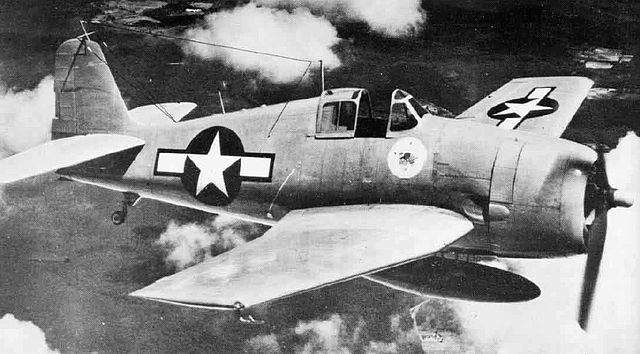

Well before the US went at war, the Naval Aviation Command proved far-sighted. In February 1938, was ordered to several aircraft manufacturers a modern combat aircraft, carrier-based which was to give a decisive answer to the Japanese desire to master the skies over the Pacific Ocean. Bell presented it’s mid-engined Airabonita, Grumman its “Skyrocket” but only Chance-Vought secured a contract to produce its XF4U Corsair prototype, only on paper stage in 1939.

However the company was committed on other projects and its XF4U1- was not ready before early 1940. By mid-1940, testings were ongoing, showing great promise. The new fighter contained many innovative design solutions, including the powerful Pratt & Whitney 2800 “Double Wasp” delivering 2000 hp. But all these novelties led to a long cycle of modifications and further military testing. When the Corsair was ready for combat use in 1941 at last, its low vertical landing speed, due to the effect created by the low wing and lack of vibility forward, was found to be too much for a moderately skilled pilot.

Even if the pilot managed to lead him onto the deck of an aircraft carrier, a safe landing was still not guaranteed and like a kicking mule, the Corsair jumped over all brake cables and fly right over them. The accident rate was so high that the F4U was just sidelined to ground airfields and the USMC. There were well-founded fears were that the navy would have its new naval fighter within the timeframe specified in the contract. Fortunately since 1938 Grumman was working on a less advanced model than the complicated Skyrocket, and while souring relations with Japan the USN command turned again to Grumman, and decided fundamentally refine the Wildcat, modified to be fitted with a powerful and heavy Wright R-2600 engine, the largest on offer at that time.

Design Development

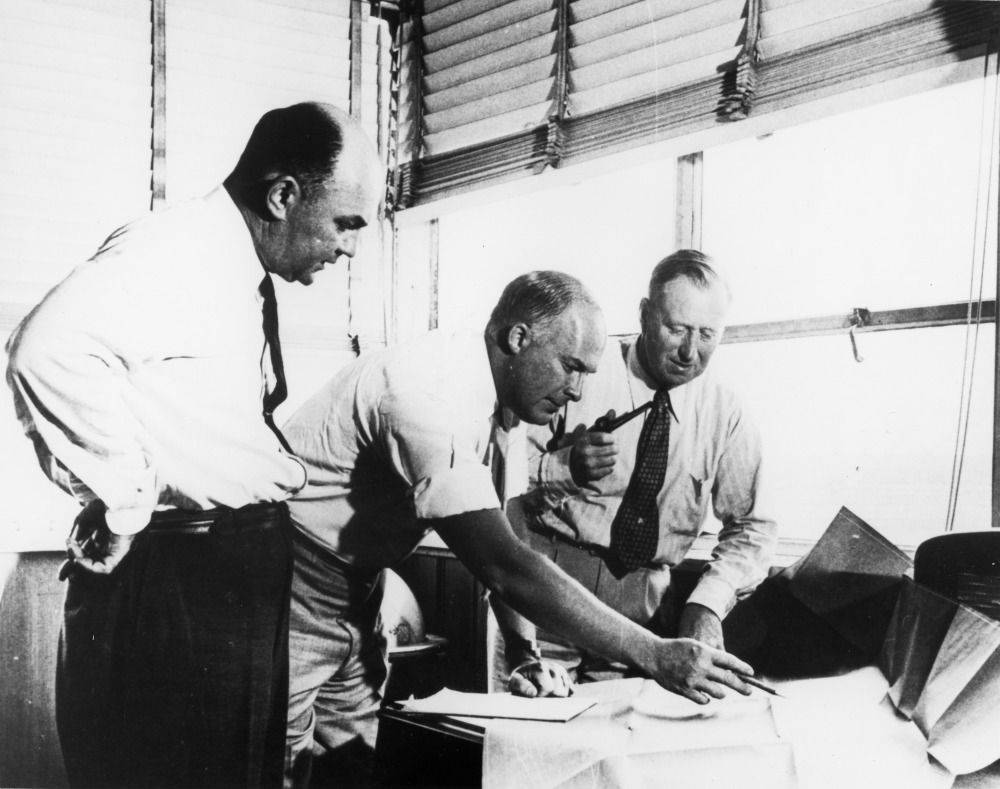

Leon Svirbul, William Schwendler & Leroy Grumman at work on the G-35 project

As part of the 1938 G-33 project already Grumman’s designers had been at work to modernizing the Wildcat in February, so in March, first estimates of an enlarged version appeared and the new project received the designation G-35. This work was carried out under the direction of William Schwendler and Richard Hutton and showed the replacement of the engine would not give expected results due to the inscreased weight and dimensions, requiring an extension of middle fuselage section. The 35% increase required a larger propeller, stronger frame and larger tail.

Work went along well but slowly in 1939, and in 1940, chief executive Leon Svirbul traveled to the Pacific Ocean, meeting pilots already flying the Wildcat on the carriers USS Hornet, Enterprise and Yorktown. At the same time the design office produced a report from all documents accumulated during the work on the G-4 and G-33 projects. This was to decided the fate of the Wildcat modernization, and the design team head William Schwendler became the strongest supporter of the creation of a brand new fighter instead, suggesting to save time, to develop it still as an extrapolation of the Wildcat.

Between Svirbul’s report and Schwendler’s proposal, Grumman’s, CEO Leroy Grumman, realized that fitting a new engine on F4F was an uphill battle, and only a half measure. Navy leaders still oreferred this program as a backup, or an interim solution as the Corsair was still preferred at this point, being head and shoulders superior to the Wildcat, and during the showdown with the Zero, LeRoy Grumman eventually convince the Navy to go for an entirely new aircraft instead, from a clean plate.

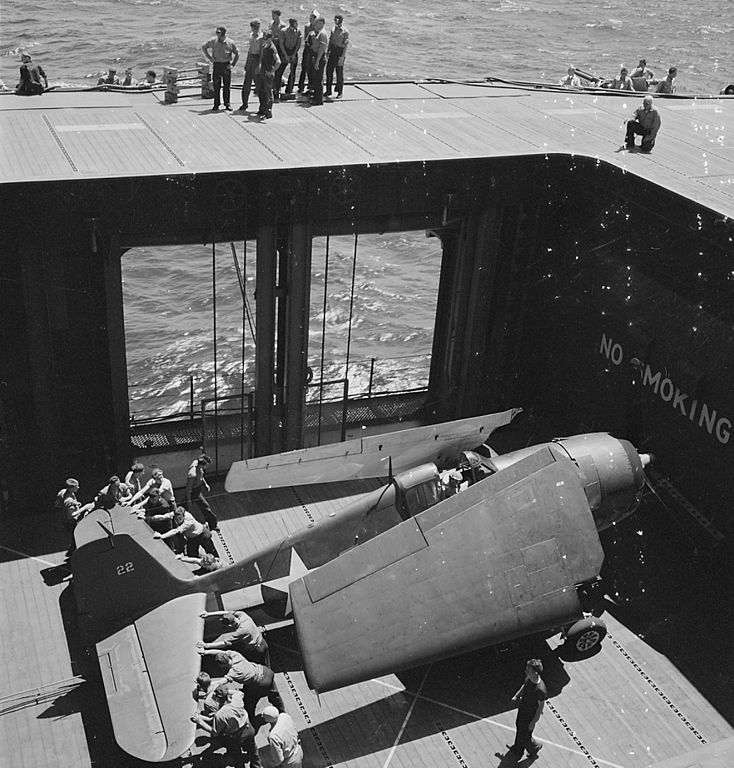

Soon a full-scale model was made and presented to the general staff on January, 12 1941. The Commission recommended some modifications as increasing the length and wing area, making it in effect the largest of all existing deck fighters. Again, the sto-wing system was also retaken, at the time used by the Wildcat and Avenger with the same success. A patent was also acquired from Boeing for a new wheeltrain with high pneumatic pressure, retracting while making a 90° turn.

Grumman had been dealing with a replacement to the F4F Wildcat as soon as the latter was about to enter production in late 1938. Based on in-house specs, some contacts in the Navy already had a look at the model, which looked already promising on paper. In fact, based solely on the reputation of Grumman, and connections in the Navy and official agreement for the prototype XF6F-1 was indeed endorsed on 30 June 1941, but the way was still long to delivery. The Navy was now willing to see this new project’s completion, but at the time for a service entry in 1944 or even 1945 as the current Wildcat was supposed to do its office long enough if modernized.

Meanwhile, Leroy Gumman and his team were confident their new fighter could be furher upgraded and use the Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone two-line, 14-cyl. radial 1,700 hp (1,300 kW) engine. A brand new and promising unit, similarly planned for the new Grumman torpedo plane (XTBF) worked on at the time. It was to be coupled with a three-bladed Curtiss Electric propeller. The model was tested in a wind tunnel, helping to refine aerodynamic details, whereas Leroy, suspecting a possible massive war production in the future, insisted to keep shapes simple, with straight lines.

The new projected model had many innovations, starting with a brand new undercarriage. Instead of the clunky old hand-wrenched system retracting fuselage retracting, making Grumman models since the “Fifi” quite stubby, for the F6F, Leroy wanted to adopt a more streamline fuselage imposing to move the undercariage in the wings. Being much heavier the new F6F needed to be sturdier as well, and it was judged more potent to have the new wheeltrain retracted under the wings, helping with stability and resilience when landing. Instead of the schock in the fuselage, close to the engine, the landing forces would be spread into the wings instead. This wide-set system was automatic, causing less distraction to the pilot, and used pressurized water for the complicated arms system turning the whole train to 90° while withdrawing in reverse into the wings.

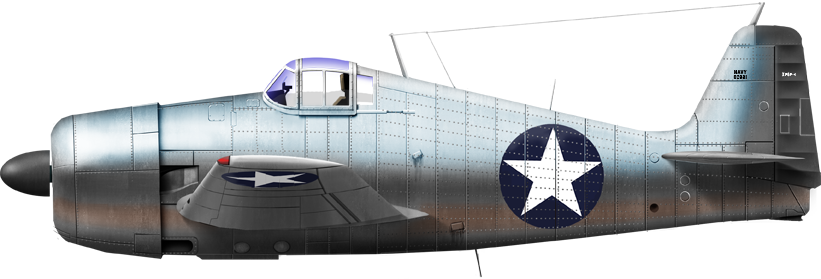

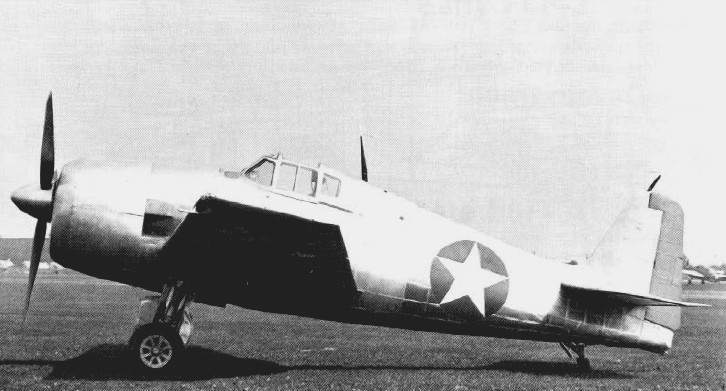

XF6F-1, with the 1700 hp Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone (June 1942)

The wing was also mounted lower on the fuselage and the larger wings were still folding, using the now trademark “Sto-Wing” system of diagonal hub similar to the earlier F4F. 30 June 1941, 13 months after the first take-off of the Corsair, Grumman at last received the urgent order it needed to justify his work, to “modernize the F4F” (longer flight range, better protection and armament) assorted with two prototypes, designated XF6F-1. On the first prototype, the Wright R-14-2600 “Cyclone” engine was imposed, and the second, XF6F-2, was to test high-altitude flight with a modified Wright R-2-2600 engine using a turbocharger. The latter was given a bottom-mounted blower intake for the twop oil coolers left and right of the engine.

On the proposal of Navy aviation specialists, visibility from the cockpit became a curcial point, important for deck landings, so the axis of the engine was deflected downward, relative to the general fuselage axis. In horizontal flight, thus, this imposed a slightly lower tail section. The cockpit itself was placed much higher, which, with the engine deflected downards created a “sloped back” caracteristic, and realized the excellent visibility in flight and landing that were researched. The low angle of attack of the wing consoles was another novelty, a decision made on the assumption that a large wing angle providied heavy lift on takeoff but was detrimental in flight by increasing aerodynamic drag.

The F6F was also on request given had larger capacity fuel tanks, giving it almst twice the range of the former Wildcat. Power was such that a 90 kgs bullet-proof shell protected the pilot as well as an armored jacket protected the oil tank and the oil radiators. The flaps and wing folding mechanism, the machine guns reload systems were all hydraulically operated. The brake landing hook and tailwheel had an electric drive. The armament at first was fixed to four Colt-Browning М2 machine guns like the Wlidcat, located in the folding part of the wing consoles. All in all, and fitted with all it’s navy gear, the new plane weighted 60% more than the Wildcat, and enormous increase. Test bench revealed the first prototype was better suited with the Wright R-2600-16 engine rated for 1700 hp at first.

A pilot’s plane

All through mid 1942, Leroy Grumman, alongside his engineers Jake Swirbul and Bill Schwendler, worked intimately with the U.S. Naval force’s Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer). But it also called for experienced F4F pilots, driven by the Navy to Grumman out of ttal confidence in the new project. It was time: For the first months of 1942, dogfight reports came in, and pilots loss amounted. All agreed on one point: The F4F was simply not as agile or as fast as their main competitor, the A6M. Although resilient, the Wildcat was a honest fighter, but certainly not good enough top beat the “Zero”. In fact even admiral Nagumo allegedly said of the US bird it was “obese like an old Sumotori…”. In short, a replacement was wanted fast, notably because there were new reports coming about army fighters that were already even better than the Zero, and the latter to the point of receiving a major upgrade. Odds were stacking against USN fighter pilots;

Colorized photo by irootoko Jr. of an F6F-3 from USS Lexington (CV-16) in 1944

Leroy Grumman and his team were perfectly aware of this. Between resumes of the reports and encounters with pilots, the picture they had was clear. The new fighter was to be designed in order to counter the Zero’s assets. It was to provide air dominance over the Pacific, planning to defeat any opposition in the years to come. On 22 April 1942, Lieutenant Commander Butch O’Hare visited Grumman siege in New York and talked at lenght with Grumman engineers, and making a full review of how the F4F fares against the Mitsubishi A6M Zero in dogfight. O’Hare was a celebrity in the US, one of the first aces of the Navy from February 20, 1942, when he became “ace in a day”, rampaging through a Japanese bomber formation. Part of the CAP he engaged nine bombers incoming to attack his aircraft carrier and practically drove them off by himself. He already also had encounters with the Zero and was well aware of its capabilities.

Also based on pilot’s report, BuAer’s Lt Cdr A. M. Jackson advised Grumman engineers to mount the cockpit higher in the fuselage for a better visbility. The forward fuselage was therefore slanted down marginally to the motor cowling to add to this visibility. It was an excellent advice as the Vought XF4U Corsair meanwhile, had a straight nose with the cockpit well behind. At last on January 7, 1942, after Pearl Harbor, and without waiting for the end of the prptotype tests, the the Navy Command ordered Grumman 1,080 F6F-1 combat aircraft.

In search for more power

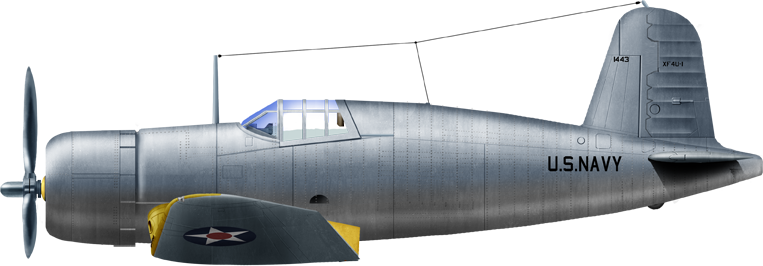

Chance-Vought XF4U-1. Although given a far better engine and faster, it was too dangerous and difficult to master for young pilots.

In view of detailed records of encounters between the F4F and A6M on 26 April 1942, BuAer urged Grumman to swap from the previous powerplant to the new and even more promising 18-cyl. Pratt and Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp, now just adopted by Vought for its XF4U since 1940. Grumman then plan to adopt the new engine for its second XF6F-1 prototype, which fuselage was even deeper. This needed also the reinforce significantly both the fuselage and the airframe. Also for it was adopted a three-bladed Hamilton Standard propeller.

Grumman assessed the new production model XF6F-3 would be 25% heavier than the XF6F-1. The Cyclone-engined XF6F-1 (BuNo 02981) first flew on 26 June 1942 while the Double Wasp XF6F-3 (BuNo 02982) flew on 30 July 1942, just a month after. Comparative tests were doubtless in their conclusion. This first flight, less than a year after the start of design work, lasted for 25 minutes with chief pilot Robert Hull on board, veteran test pilot since 1936 with Grumman. It revealed minor stability issues quickly addressed. Ease of operation and landing characteristics were also noted as excellent. For its size and weight, it had generally an excellent horizontal maneuverability.

And yet, pilots stressed for more engine power as dictated for the first encounters over the Pacific, notably over the Midway Atoll showing that to defeat the zero horizontal speed and rate of climb had to be higher, much higher in fact that those displayed by the XF6F-1 prototype. This required radical decisions, either to install a more powerful engine or to significantly reduce the weight of the airframe. Of course, the second option was strongly rejected not to degrade combat qualities in such context.

XF6F-2. The first XF6F-1 prototype was revised and fitted with a turbocharged Wright R-2600-16 Cyclone radial but the F-2 had the turbocharged R-2800-21.

Thus, Pratt & Whitney was contacted to provide for it’s latest engine in production, the “Double Wasp”. Indeed, even during design work on the XF6F-1, William Schwendler believed it would be too heavy and suggested right away the Pratt-Whitney R-2800-10 Double Wasp, same unit installed on the XF4U-1. Leroy Grumman agreed and went back with the proposed modification to the navy. However, since its delivery was already book months in advance, delays would amount.

The Navy however insisted on using the abvailable Wright R-2600 engine, as its production was fully mastered and reserved were in sufficient quantities for mass production. Using his official and personal connections, Leroy eventually still managed to secure the delivery of the Double Wasp, not anting to reproduce the experience of Brewster… On June 3, 1942, in fact, even before the first XF6F-1 flight, the military which wanted to keep the engine for themselves signed the decision not to adopt it.

It’s on 30 July 1942 that the F-2 was first flown by Robert Hull, for 11 minutes. In appareance it only changed by the location of the turbo receiver and pitot tube moved from the top to the bottom of the right wing tip. Another modification was the reduction of the external exhaust pipes lenght. The new XF6F-3 was the first receiving the official nickname “Hellcat” while mechanics started to call it the “aluminum tank”.

XF6F-3, with the new 2000 hp Wright R-2800 Double Wasp (July 1942)

Despite the massive mass increase, the F-3 was head and shoulders more powerful and fast. The navy arrived to the same conclusion but still wanted a few alterations. The first production F6F-3, fuelled by a R-2800-10, flew on 3 October 1942. It was soon delivered in larger quantities, and reached the first active unit, VF-9 based on the brand new USS Essex, in February 1943. The “Hellcat” arrived just at the right time to fill the decks of a new serie of large fleet carriers. It was a match in heaven for this second, crucial part of the Pacific war until Victory.

While the F3 was about to come into production, an unexpcted event happened: 4000 km from there, in the frozen peaks of the Alaska chain, a lone PBY Catalina on regular patrol spotted a crashed wreck on the small island of Akutan, belonging to Aleutians. The observers made another, closer pass and realized there was a hinomaru on the wing… Making a closer flyover one pilots identified it as a “zero”. Cordinates were immediately transferred to the base and in a few hours later a team arrived on the island to examine the wreck.

They found pilot Tadeyoshi Koga dead in the cockpit, dying during his crash landing caused by engine failure after an air battle. What was remarkable, was that he landed so well, the plane was almost intact. It was quickly dismantled and taken back to California for close examinations, with ONI teams at work 24/24 for this massive intel breakthrough. In August 1942, Grumman aviation experts came in San Diego to witness the flight of the just restored A6M, tests showing their Hellcat had an horizontal flight speed advantage and was generally not that not inferior to what had gained the aura of a flying wherewolf. Back to Grumman the team only reinforced Leroy Grumman that he was on the right way, also confirmed his new engine choice and general concept.

The ‘turbo Hellcat’, F-2 to F-6 (1944)

XF6F-4

The F-4 was a late-1942 development while production was just setup for the F-3. The XF6F-3 was indeed fitted with a two-stage, two-speed supercharged 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-2800-27 Double Wasp radial piston engine in order to increase performances overall, and allow the Hellcat to carry a more powerfully armament (hopefully cannons) and heavier bomb payload.

On 17 August 1942, indeed, the first prototype XF6F-3 crashed after the oil system feed failure, and made a belly-landing. Thanks to the pilot’s skills and location, the aircraft on suffered only minor damage. It was decided to modify it immediately, by fitting the new Pratt-Whitney R-2800-27, copprising a two-stage booster. On October 3, 1942, the rebuilt model now called XF6F-4 made its first flight and this cionducted engineers to get rid of the compressor, due to insufficient reliability.

The new F-4 had also four Colt-Browning M20 20 mm autocannons and 200 rounds of ammunition, and was abundantly tested at the Naval Aviation Test Center, showing the new armament was not compared fafourably for a day fighter. It was decided to stey with the six guns arrangement. True, it turned out that the guns were preferable for night and assault. After completing tests the XF6F-4 was reconfigured into what became essentially the F6F-3N version, night fighter.

Meanwhile at Grumman, the still existing XF6F-1 was re-equipped with the Pratt-Whitney R-2800 engine and put to the XF6F-3 standard. It first flew on September 13, 1942 with a slightly modified stabilizer. Work on it stopped while the F6F-3 had in standard the Pratt-Whitney R-2800-10W engine.

By the end of 1943, modifications of the “tubo” XF6F-2 for better high-altitude performances were tried. The lack of reliable turbochargers had this implementation constantly postponed. Only by adopting the patent of emigrated Swiss engineer Rudolf Birmann, a new promising model was developed, and tested on January 7, 1944 by Carl Albert with a Pratt-Whitney R-2800-21 fitted with the new P14B turbocharger, connected to a four-bladed propeller. Successful tests led to its proposed adoption by the F-3, but at the time the Navy saw no need for an high-altitude fighter. On July 6, 1944, this led to the first flight of the XF6F-6, essentially an F6F-3 fitted with the Pratt & Whitney R-2800-18W (2100 l. C) with direct injection. Two prototypes were developed. One reached 6675 kph at 671 m. Again, no serie was approved as the F4U Corsair showed already the best performance with the same engine.

From the F-3 to the F-5

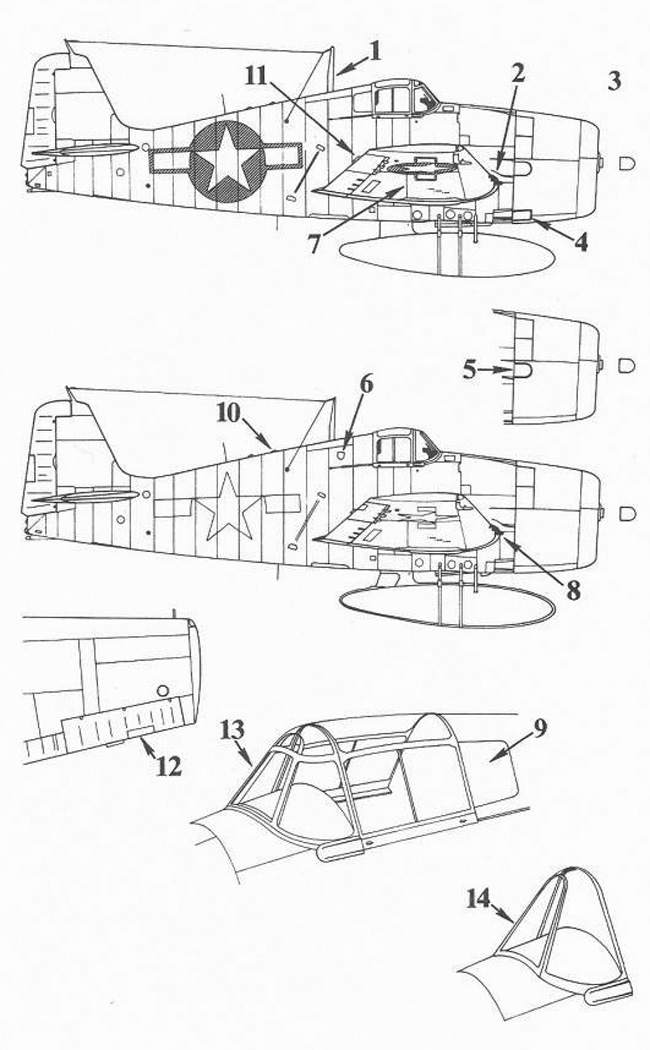

Diferences F6F-3 vs. F6F-5

The F-3 was constantly modified as production started. But it was not a smooth affair. Leon Svirbula, the “production genius” at Grumman saw tough times. The main production facilities were concentrated in Betpage, and could not produced the Hellcat, as its lines were alread full with the latest Wildcats (soon taken over by GM) and the Avenger plus less known models such as the Widgeon seaplane. In August 1942 he therefore supervised the construction of a new factory on Long Island, New York. Finding steel of limited supply was eventually a battle won with the help of the city authorities, selling a railway viaduct on Second Avenue, and remains of the exhibition pavilion. These helped setting up the factory and staff was recruited straight from the street of NYC. Later, Clark said, “The Hellcats” were built by cobblers.” speaking of the labour quality. But production began nevertheless without even waiting for the completion of the roof, capitalizing on summer. Official inauguration meanwhile took place on 1 June 1942 and the factory was “ready” in September.

This new plant was gargantuan, and many improvements were made to make the production of the F-3 as smooth and streamlined as possible, while making provision for easy “on the fly” serial improvements. Many were made in fact: The first production aircraft was tested on October, 4, 1942 by test pilot Selden “Connie” Converse. During a landing test on an aircraft carrier, a brake hook was torn off however, showing some improvements to make. A month later the rear part separated entirely and was destroyed. After strengthening the tail, additional tests showed no more issues.

Once this was of the way, Leon Svirbula howed way to massively increase production, in such a way no manufacturer in the US ever shown. It was in blatant, abolsolute contrast of Brewster, also near NYC. At the end of January 1943, the first six were distributed, 35 in February, 81 by March, 130 by April. They missed the propeller bow and main landing gear guards. Their niches were redone and the engine cover was slightly reworked. The initiial few first serial models were in fact assembled at Betpage.

Changes made were as follows: From #273, the lower surface of the left wing was reworked as new landing lights. From #910 the antenna mast was relocated behind the cockpit, perpendicular to the aircraft centerline. From #909 this antenna was tilted forward and fairings for the two internal machine guns in the wing console replaced by covers. From #1265, flaps of the engine cooling control system in the lower part of the cowling were deleted. From #1501 the convex stamping on the side exhaust festoons was made flush. From #1900 the R-2800-10W engine received a new injection sustem using a water-methanol mixture. From #2651 the antenna mast was again slightly offset to the left.

The cockpit canopy was also modified, from a frame with four plexiglass panels and with a 38 mm armored glass plate on the frontal arc. Between the plexiglass front panel and bulletproof glass there was a space into which hot air was forced in, to prevent ice formation. The new front part was made of three transparent pieces, all of bulletproof glass. A special liquid was also used as antifreeze agent, sprayed on it in winter.

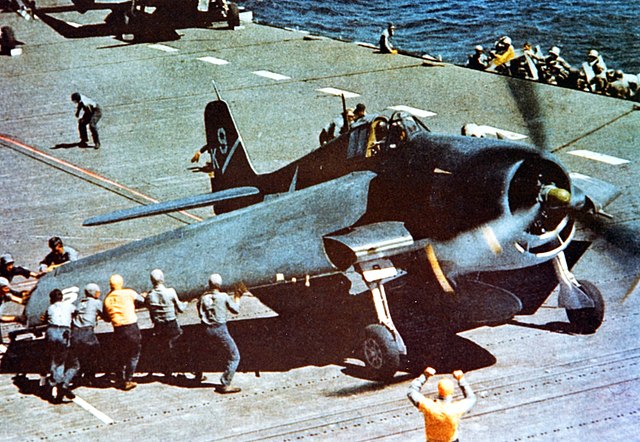

The F6F-3 had no bomb rails or rocket racks underwings, causing some criticism from Navy commanders that wanted the attack capability offer by the F4U. This, Grumman led improvements on the airframe in order to be fitted with six racks with tested made directly in combat units and modifications in naval aircraft repair shops. The F-3 received in 1943 Bomb racks for two 454 kg bombs under the belly, plus six to eight racked underwings for unguided HVAR rockets.

By January 1944, some 60% F-3 were equipped with the new Pratt-Whitney R-2800-10W engine, now able to reach the massive output of 2231 HP for a short time. From April 1944 this was standardized.

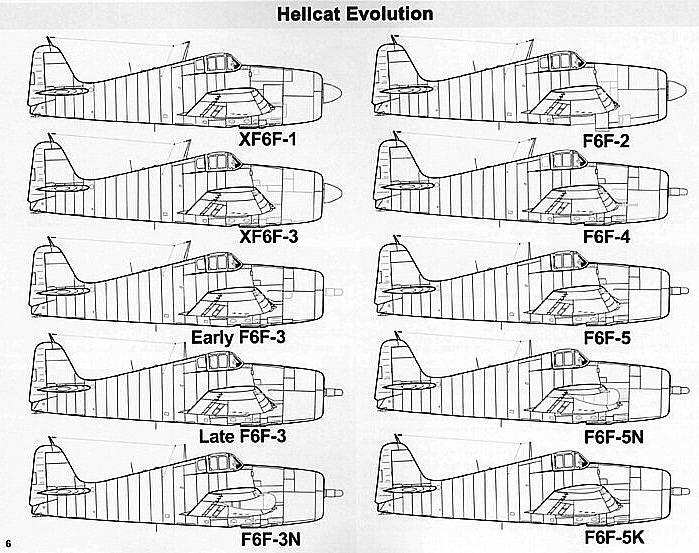

All variants of the F6F.

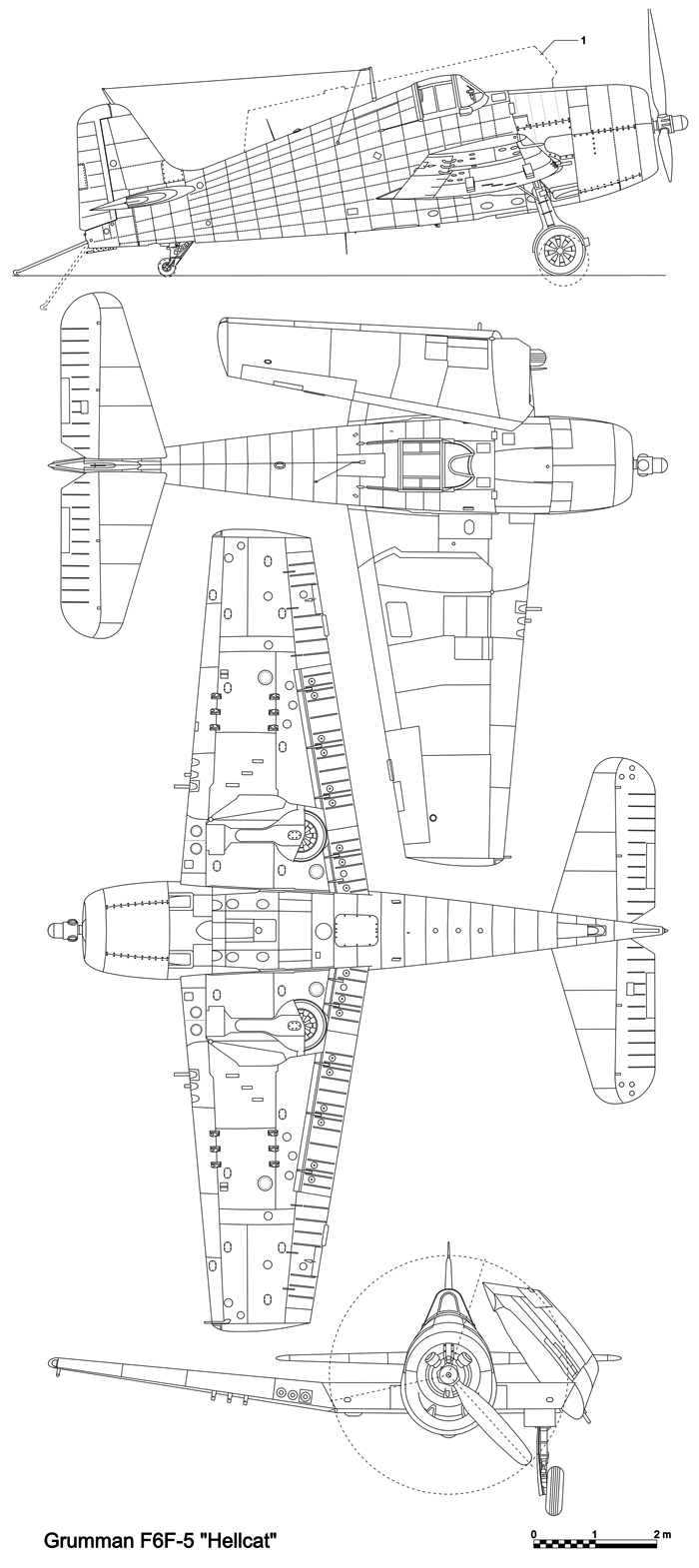

Design

Grumman XF6F-1 Hellcat 1942

The basic design was ready in 1941, and by July 1942, after the prototype was tested, a Zero fighter shot down during the Aleutian campaign was was discovered damaged in Alaska. It was put back together and tested, and ultimately caused a few changes in the final build of the F6F. The F6F compared to the F4F was a big plane, and in wing surface alone, was the largest of all allied naval fighter. It was just a tad inferior to the might P-47 Thunderbolt, and share the same engine. Many in fact compared it to the naval version of the “Jug” and it was as durable.

Landing Gear

The landing gear was of course, due to the larger model compared to the Wildcat, no longer rectrating in the fuselage and opening in a “vee” when landing. Instead, Leroy Grumman chosed both stability and ruggedness as well as simplicity, with a classic type retracting in the wings. What was unique was it turned 90° to enable the roadwheels to insert faultlessely, fitting flush inside the wells. The arms mechanism ensured that when deploying the wheeltrain down, gravity assisted the pilot operation. During the turn operation however, the main leg’s cache caused a lot of drag until reaching it’s final position and the pilots felt it. The same happened when retracting it, but it gave a backup “feeling” indication the operation was successful. The leg was of course damped by it’s own oil-based coil, and had a second damping arm lower on the inner wheel leg.

Catapult hook, tailwheel and tailhooks

Under the inner section of the wings were located on both sides, little but very strong hooks to be grabbed by the catapult slings cable. The shape of it allowed the cable to simply fall back by gravity when fully extended off. However, Hellcats, like Wilcats before, were rarely catapulted. Typically in a “sunday punch”, the fighters, which needed less lenght, would be parked and just take off free. It’s only for certain operations, notably the CAP (Combat Air Patrol) fighter left when the air strike was in the air, were quickly brought up by the forward elevator and launched by catapult to win time.

The tail hook was approx. one meter long (3.2 feets) and hinged mid-lenght vertical of the tail, in a small recess. It disappeared entirely when in flight to keep the bottom as flush as possible. When down, it formed a 90° angle, being lower than the extended tailwheel. The latter was located forward of the hook, and was also completely retracted flush inside the tail bottom end, with just a small protrusion to mark it’s location. Its of course improved top speed. The tailwheel was also composed of a free-rotating wheel support, and a tractraable arm suspended by two legs. These structural elements, like most in the plane, were strong but also perforated to spare weight.

F6F Cockpit/flight deck*

(To come)

*The FAA recently proposed to swift to gender neutral terminology for better inclusion of female and nonbinary persons in the industry. I left have no problem with that, however on my side, i still refer to the old term according to WW2 terminology. No offense intended. At the time female pilots could in theory handle these models, but only for taxiing them in some cases from the manufacturing facility to a military airbase or transit field, pending deployment. Never frontline service. But this concerned mostly large aircraft, bombers and the like. Smaller ones like these could have been transported by rail and in the case of Grumman, the facility was close to the sea and NY Navy yard. From the factory tarmac to the flight deck was a stone throw.

Engine(s)

The F6F-5, most common production variant, was powered initially by the Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10W Double Wasp, a 18-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine with an output of 2,200 hp (1,600 kW) with a two-speed two-stage supercharger and water injection.

The Hellcat engine burned 150 octanes fuel, whereas Japan used 87 octanes fuel, allowing better performances of it.

There were three intakes, caracteristic of the model, below the main opening, and these cooled the carburettors and one the oil cooler. This, combined with the relatively low-mounted engine compared to the pilot’s seat make the fuselage so tall.

Another aspect of the engine were its four cooler flaps below. They were generally closed in flight, only opened when on the ground for maximal cooling, as the top engine cawls, with some overlapping over inserts for the main exhaust pipes. They were closed half way for takeoff, and closed in flight too.

This power was passed onto a three bladed standard Hamilton propeller, 13 ft 1 in (3.99 m) diameter constant-speed propeller. This Hamilton Standard “Gidromatic” type had a variable pitch (the prototype was given “Curtiss Electric” model). It was typically painted black with yellow tips.

Protection and equipments

As a naval plane, to Navy and 1942 standards, the F6F was extremely well protected. It also had plenty of space in its cavernous fuselage for a lot of gear.

As for protection, navy pilots affectionately dubbed it the “aluminium tank”, as they venerated its ability to take enormous punishment.

Armament

Main: 6x 0.5 in cal. M2 Browning

Initially the first version only had four MGs and carried in all 1400 rounds. Later models increased had six but the supply was still 1400 rounds, only distribution changed. The metallic rounds belts comprised a tracer every ten rounds as customary for this weapon, enabling the pilots to better vizualise the path of its fire. The six HMGs were of course calibrated to cross at a certain distance. Their placement was staggered, as shown by the barrels protruding from the wing’s froward edge, was due to the need to feed all three, so there was room for three ammunition belts running from the large ammunition bin inside the inner part of the wings. They were reloaded by simply opening a hatch, affixed on a swing arm to stay open during the operation. It was hindged to the front to avoid any gap provoking its opening in flight.

Cannons (F6F-5N only)

F6F-5N at NAS Jax, 1944-45

The night variant, F6F-5N was the only one of all to be fitted with two 20 mm (0.79 in) autocannons, with 225 rounds each, plus four Browning M2 0.5 in (12,7 mm), all in the wings.

Bombs:

4,000 lb (1,800 kg) full load, with on the Centerline rack:

-One 2,000 lb (910 kg) bomb or a Mk.13-3 torpedo

Underwing:

-Two 1,000 lb (450 kg), 500 lb (230 kg), 250 lb (110 kg), or Six 100 lb (45 kg) (Mk.3 Bomb Cluster).

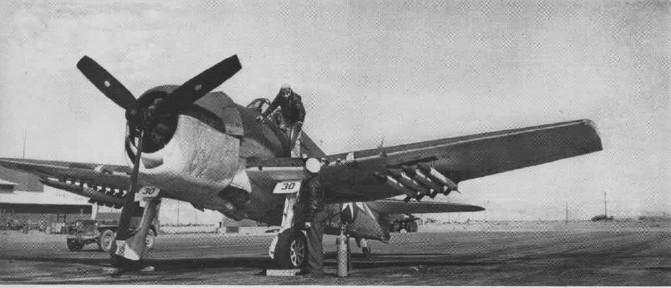

Rockets: 6x

F6F-5 sporting rack with 5-in HVAR rockets

The F6F-5 was modifioed to received six underwings racks, three either side, for six 5 in (127 mm) HVARs or later in the war, tow 11.75 in (298 mm) Tiny Tim unguided rockets.

External Tanks:

There was a single, normal 150 gallons (568 l) fuel external tank, well profile and affxed under the center line belly. It was held up by a single releasing pin, in the liasison between the aft leg and the fuselage. The forward section was held in place by simple belt straps. When the pilot spent it, generally before the main tank to avoid fighting with it under the belly, it was dropped by the rear, slipping through the straps.

However it could be supplemented by two smaller 100 gallons droppable fuel tanks underwings. These were placed on the removable main bomb racks under the inner wings section. Their small size fed the main wings fuel tanks and the leg dropping system was the same. They were likely used by the wing commander, generally which stayed longer during an attack (those spending their ordnance generally flying back without waiting).

Cameras: The “recce hellcat”: F6F-3P

It was developed by order of the Naval Aviation Command. The “P” stands for “photo” (reconnaissance) and two cameras were installed in the fuselage, one offering a panoramic with a long focal length mounted on the left side aft of the wing’s bleeding edge, and on the other side with as standard combination a 304.8-mm and a 609.6-mm vertical panoramic cameras. These were frequently used in 1944-45, especially over Kyushu.

Radar(F6F-5N):

F6F-3N testing a wing-mounted radar, 1943

Early tests were performed with the F-3 in 1943-44. But it was produced only on numbers with the F-5 variant. The F6F-5N night fighter was fitted with the smaller and lighter AN/APS-6 radar in a fairing on the external starboard wing. This final version of the night fighter was so successful it became the last aboard US Carriers, until 1948.

The “night hellcat” was however at first the F6F-3N: At the beginning of 1941 work started on an airborne radar station to be fitted on a fighter. The radar was created by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with assistance of the British. It was designated AIA. After upgrades in 1942 it became the Sperry AN/APS-6. Weighting 113 kg () with the transmitting-receiving unit and search antenna, finding the suitable installation was required at Grumman, soon contacted for tests. AIn the spring of 1943, the Naval Aviation Command offered Grumman to modified a F6F-3 with this radar as a night fighter.

On 3 June 1943, static tests of the XF6F-3N prototype, with the radar in a dielectric pod mounted on the forward edge of the right wing started at the Aviation Aeronautical Test Center, Quonset Point. In addition the cockpit received a new instrument panel with red, anti-reflective illumination. The front part of the pod received armored glass. This was completed with a AN/APN-1 radio altimeter, IF/AN/APX-1 IFF identification system, landing light and radar display in the cockpit. The latter showed two digital marks, one indicating the distance to the target and the other its position relative to the pilot. Detection was about 122 m vertically, 7.2 to 8 km in front of the plane.

The add weight slowed down top speed to 32 kph (). The electronic equipment could be destroyed by a charge activated by a simple command activated by the pilot in case of a crash-landing in hostile territory. One F6F-3N was also fitted in addition wirh with a powerful searchlight on the left wing, symmetric to the radar. In the same facilities the F4U-2 also tested the same system. Eventually as production started to swift to the new F-5 standard, the remainder of the F6F-3s, about 50% of the total, could actually be produced as night fighters, but it was discontinued. The F-5 saw the same, improved installation and became the new standard.

The F6F-3E was in effect a sub-version of the night fighter, fitted with the alternative Westinghouse AN/APS-4 radar, lighter than 30 kg but with a larger horizontal search area, a narrower vertical area. The target display however was mediocre, and forced the abandon of this version after just 18 converted.

Production

Bethpage plant production of the F6F-5 in 1944

The F6F series was intended to take harm and the pilot securely return to base. A shot safe windshield was utilized and a sum of 212 lb (96 kg) of cockpit protection was fitted, alongside defensive layer around the oil tank and oil cooler. A 250 US lady (950 l) self-fixing gas tank was fitted in the fuselage. Standard deadly implement on the F6F-3 comprised of six .50 in (12.7 mm) M2/A Browning air-cooled automatic rifles with 400 rounds for each firearm. A middle area hardpoint under the fuselage could convey a solitary 150 US lady (570 l) expendable drop tank, while later airplane had single bomb racks introduced under each wing, inboard of the underside inlets; with these and the middle segment hard point, late-model F6F-3s could convey an absolute bomb load more than 2,000 lb (910 kg). Six 5 in (127 mm) high-speed airplane rockets (HVARs) could be conveyed – three under each wing on “zero-length” launchers.

Two night-contender subvariants of the F6F-3 were created; the 18 F6F-3Es were changed over from standard-3s and highlighted the AN/APS-4 10 GHz recurrence radar in a case mounted on a rack underneath the conservative, with a little radar scope fitted in the primary instrument board and radar working controls introduced on the port side of the cockpit. The later F6F-3N, first flown in July 1943, was fitted with the AN/APS-6 radar in the fuselage, with the radio wire dish in a bulbous fairing mounted on the main edge of the external traditional as an improvement of the AN/APS-4; around 200 F6F-3Ns were built.

Hellcat night warriors asserted their first triumphs in November 1943. An aggregate of 4,402 F6F-3s were worked through until April 1944, when it was replaced by the F6F-5. Early production F6F-5 were tried with eight 5-in HVAR rockets in 1944.

F6F-5 detailed design

The F6F-5 highlighted a few enhancements, including an all the more remarkable R-2800-10W motor utilizing a water-infusion framework and housed in a somewhat more smoothed out motor cowling, spring-stacked control tabs on the ailerons, and an improved, clear-view windscreen, with a level protected glass front board supplanting the F6F-3’s bended plexiglass board and interior defensive layer glass screen. also, the back fuselage and tail units were fortified, and aside from some early creation airplane, the vast majority of the F6F-5s assembled were painted in a general very dark ocean blue. After the initial run, in 1945 not so many F6F-5s were buult until V-Day, and the small windows behind the primary cockpit were deleted.

A couple of standard F6F-5s were likewise fitted with camera gear for surveillance obligations as the F6F-5P. While all F6F-5s were fit for conveying a deadly implement blend of one 20-mm (.79-in) M2 gun in every one of the inboard firearm straights (220 rounds for each weapon), alongside two sets of .50-in (12.7-mm) assault rifles (each with 400 rounds for every firearm), this setup was just utilized on later F6F-5N night fighters. The F6F-5 was the most well-known F6F variation, with 7,870 being built.

Different models in the F6F series incorporated the XF6F-4 (02981, a transformation of the XF6F-1 fueled by a R-2800-27 and outfitted with four 20-mm M2 gun), which previously flew on 3 October 1942 as the model for the projected F6F-4′. This form never entered creation and 02981 was changed over to a F6F-3 creation aircraft. Another test model was the XF6F-2′ (66244), a F6F-3 changed over to utilize a Wright R-2600-15, fitted with a Birman-made blended stream turbocharger, which was subsequently supplanted by a Pratt and Whitney R-2800-21, additionally fitted with a Birman turbocharger.

The turbochargers ended up being questionable on the two motors, while execution enhancements were minor. Likewise with the XF6F-4, 66244 was before long changed over back to a standard F6F-3.[34] Two XF6F-6s (70188 and 70913) were changed over from F6F-5s and utilized the 18-chamber 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) Pratt and Whitney R-2800-18W two-stage supercharged outspread motor with water infusion and driving a Hamilton-Standard four-bladed propeller. The XF6F-6s were the quickest form of the Hellcat series with a maximum velocity of 417 mph (671 km/h), yet the conflict finished before this variation could be mass-produced.

The last Hellcat carried out in November 1945, the all out creation being 12,275, of which 11,000 had been implicit only two years. This high creation rate was credited to the sound unique plan, which required little adjustment once creation was in progress.

Variants

XF6F-6

- XF6F-1, initial prototype (1,600 hp (1,193 kW) Wright R-2600-10 Cyclone 14)

- XF6F-2: Turbocharged Wright R-2600-16 Cyclone, then R-2800-21, Birman turbocharger

- XF6F-3: 2nd prototype (2 charges supercharged 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10 Double Wasp)

- XF6F-4: F6F-3 with two-speed turbocharged 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) R-2800-27

- XF6F-6: 2 protos with 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) R-2800-18W, 4-bladed propellers

- F6F-3 (British Gannet F.Mk.I/Hellcat F.Mk.I) 2,000 hp R-2800-10 Double Wasp

- F6F-3E Night fighter version (AN/APS-4 radar)

- F6F-3N night fighter version (AN/APS-6 radar)

- F6F-5 Hellcat (Hellcat F.Mk.II) R-2800-10W engine

- F6F-5K: Converion into radio-controlled target drones

- F6F-5N night fighter AN/APS-6, 2x 20mm M2 cannons

- F6F-5N (British N.F.MkII) Night fighter version (AN/APS-6 radar) 2x 20 mm AN/M2 cannon, 4x 0.50 in

- F6F-5P Photo-reconnaissance aircraft, cameras rear fuselage

- Hellcat FR.Mk.II British Hellcats photo reconnaissance version

- FV-1 Proposed designation for the Canadian Vickers cancelled

Combat use

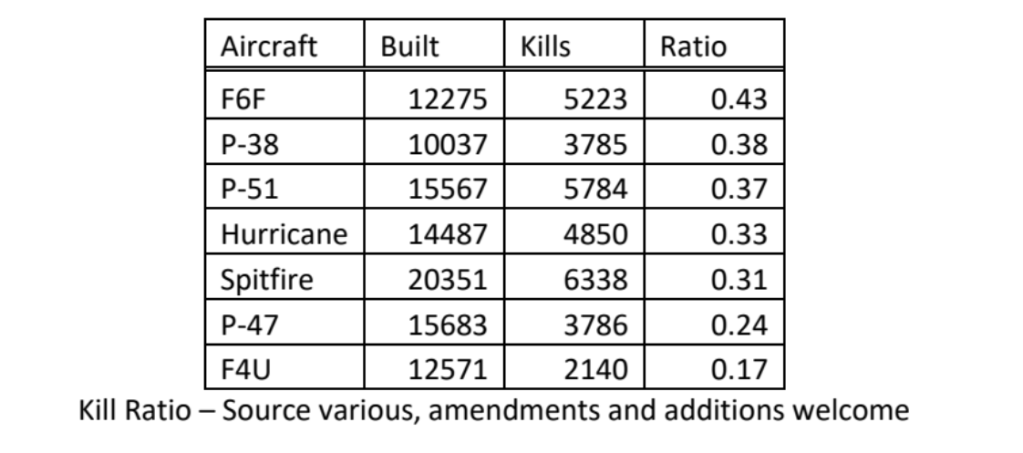

The Hellcat compared to the rest: Butcher bird, really ?

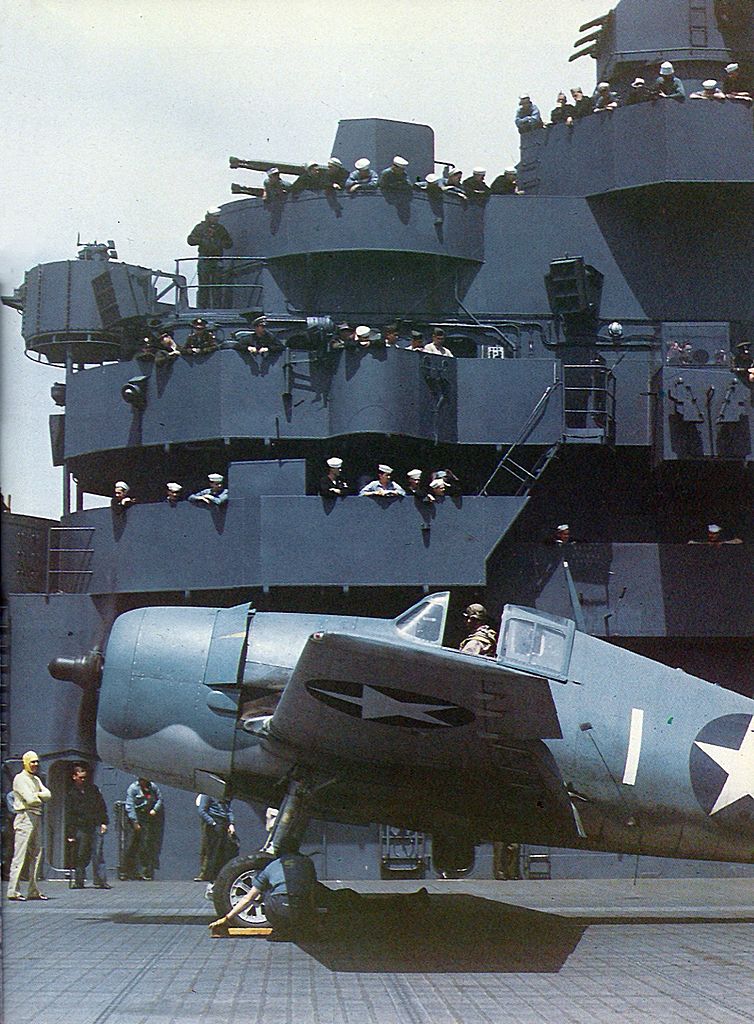

A hangar-catapulted Hellcat. This solution was tested on several carriers but eventually dropped as too problematic notably for hangar handling.

The Grumman Hellcat has cemented for most naval and aviation historians alike the reputation of being the best naval fighter of WW2, and third best allied fighter. It killed more planes in the pacific than any other allied fighters, USAAF, USN, USMC, or FAA. But it third for the tally globally in WW2 (5223 kills vs 5784 (P51) or 6338 (Spitfire)), although having best ratio or any fighter of this war (comprising the P38 Lighting, Mustang, M109, Fw-190, Zero and Oscar). It had many advantages for this cause:

- It was really powerful. A 2000+ hp engine meant better performances in all quarters*

- It was well armed, with six cal.05 M2HB HMGs, of the sturdy, never-failing Browning. Not guns, but still enough.

- It was rugged to the extreme, both for safe rought deck-landings, but for overall protection

- It had a better visibility overall (mostly compared to the Corsair, eliminated in 1943 from carrier operations)

- It had low cost, fast construction and easy maintenance

*In some ways, the Hellcat introduced the concept of “power reserve” familiar to us for modern fighters. There was more than required to have the aircraft flying and efficient in safe conditions, on-specs, and plenty of it for extreme manoeuvers, the pilots confident of the extreme sturdiness of the structure. In fact so much, the human factor was often the limitating one… It was in fact the last nail in the coffin of “old school aviators” inherited from WWI placing agility over power.

There were certainly more to this, but that was, in essence, it’s four strong points. It was still an inferior dogfighter to most IJN and IJA fighters until 1945 (see below), but with experience, pilots learned to play its strenght over the enemy’s weaknesses, with amazing results. The best ever navy pilots, to this day (see later), were flying the Hellcat. It also proved a valuable fighter bomber, explaining its long postwar career. Also when replacing the F4F on fleet carriers, it was paired with the new Essex-class aicraft carriers filling the ranks of TF 38/58 and thus, really was the “standard” fighter to the end.

Aboard USS Saratoga, 1943

Compared to the allies, the FAA indeed never had a comparable fighter: The early war Fairey Fulmar was a jack of all trade, and as they are often too compromised to be a valuable fighter. The Sea Gladiator was a biplane, totally dominated in speed and power, the Sea Hurricane, a monoplane, too, and the Sea spitfire and seafire were too fragile for carrier operations. It’s only rivals appeared in 1945 and after: The Hawker Sea fury and Blackburn Firebrand. In fact the FAA fully embraced the Hellcat, at first known as the “Gannet” (Later “Hellcat”), and soon a main asset in British pacific operations in 1944-45, together with the Corsair (see below all this).

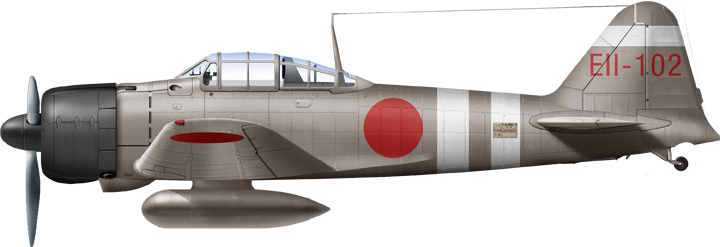

Versus the A6M “Zeke”

Main adversary of the Hellcat, the Zero was however too weakly built in comparison.

In 1943, when the Hellcat start to arrive in active units, the IJN was still transitioning two models essentuially to newer versions (for the zero) or new models entirely. Japanese designed Jiro Horikoshi’s masterpiece is a legend of aviation, which not only achieved the greatest kill ratio and tally of all Japanese Aviation (army and navy combined), but the most produced Japanese plane overall, with more than 10,000 delivered until 1945 and constantly upgraded. A full article is being written on it, so we will not dwelve on its caracteristics or development history.

The “Zeke” has been a nightmare for all allied aviation -including fighters- from December 1941. Rarely seen over China, it remained mostly unknown until Pearl Harbor. In the early months of 1942, the A6M1, then A6M2, earned the mastery of the air relatively quickly. Only one model was more or less capable of opposing it, with the right pilot: The F4F Wilcat, precedessor of the F6F. Like it’s larger sister, the F4F was very sturdy with good enough agility for its time, and in some occasion and in the right hands, was nearly a match. But many found it sluggish.

But as the Hellcat was refined, using former F4F pilot’s experience, advices and dogfight as a reference point, it became clear that it’s number one designated adversary, the Zero could be beaten at it’s own game, but by a completely different philisophy: Not achieving better agility by lightness, but by brute power. Performances combined to the general sturdiness, in the right hands, were to be enough. It would have to wait until mid-1943 to really figure this out. Nevertheless, the F6F was far more than an upgraded F4F: It had on the onset 800 more horse power for 391 mph, 60% more, but also 45% more than the Zero. Its climb rate of 1,300 ft/minute was greater, notably 400 ft/minute greater than the Zero. Also instead of two, it had three 6–0.50 caliber guns and more armor around the pilot and critical engine parts.

In between, the Zero was improved constantly, with its major upgrade also coming in 1943: The A6M5. The previous A6M4 Type 0 Model 41/42 which arrived in mid-1942 already became a nightmare for the F4F, but the next iteration was by far the most modified and best of them all. Also called the Model 52 it became the main adversary of the Hellcat. The goal was to shorten the wings to increase speed, dispense with the folding wing mechanism and revised all wings and tail mobile parts, plus the engine, 1200 hp Sakae 31, but also for the last, A6M5c, One 13.2 mm (.51 in) Type 3 in each wing outboard of the cannon, deleted cowl 7.7 mm gun, 55 mm (2.2 in) thick piece of armored glass, 8 mm (0.31 in) armor behind the seat, Wing skin thickened. It first flew in September 1944 most being used to intercepting B-29s.

At some point report came from encounters with the very latest “Zero”, the A6M5, showing that the Hellcat was quicker at all elevations. The F6F out-climbed the Zero hardly over 14,000 ft (4,300 m) and rolled quicker at speeds over 235 mph (378 km/h). The Japanese contender could out-turn its American adversary effortlessly at low speed and partook in a somewhat better pace of move under 14,000 ft (4,300 m). The preliminaries report closed:

Do not dogfight with a Zero 52. Do not try to follow a loop or half-roll with a pull-through. When attacking, use your superior power and high speed performance to engage at the most favourable moment. To evade a Zero 52 on your tail, roll and dive away into a high speed turn.

The navy recoignised in short the A6M5 was a better dogfighter, so pilots would have to just learn to fight the Hellcat’s fight, not the Zero’s fight, never entering its own game. This, combined with a greater experience overall and comparatively dwindling reserve of skilled IJN pilots explained the “great Marianna Turkey shoot” in June 1944 and all the following mass ecounters.

In October at Leyte (Battle of Cape Engano), the Ozawa’s bait force and Kido Butai (a shadow of its former self) launched a combined 108 aircraft at TF 38. Unsurprisingly they were delt for upon arrival, radar-warned, by scores of Hellcats fighters squadrons. Not a single one went close enough to do any damage to the fleet, a 100% kill ratio on this single wave. Some of these carriers, like IJN Chitose only had A6M fighters aboard, most being the Type 52.

Versus the Ki-43 Hayabusa “Oscar”

The Ki-43 was the successor of the 1st gen. monoplane Ki-27 “Nate”, Army equivalent to the A5M, and answered the A6M based on similar specifications. The A6M would have turned better for the Army and help the Japanese aircraft industry to share and reach greater production scale, but alas, inter-service rivaly prevented that. Engineers of Nakajima, traditional provider for the army’s fighters since 1930, tryied to emulate everything that was so special about Jiro Horikoshi’s graceful and feather light “zero”. The resulting design first flew in January 1939 but development took time and it only arrived in active units by October 1941, almost two years after, with 5,919 produced until replaced by the Ki-84.

The Hayabusa was basically all the preferred philosophy for IJA pilots, quite similar to IJN pilots in one main respect: Speed and supreme agility over all else (including sturdiness and armament). The “Oscar” as it was known by US intel, was a natural dogfighter and showed it time and again, delivering the same type of performances the “Zero” achieved. It was powered by a small Nakajima Ha-115 14-cyl. radial 970 kW (1,300 hp) engine, to reach 530 km/h (330 mph, 290 kn) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft). Not really an interceptor, more a ballerina armed with two 7.7 mm LMGs initially it was constantly upgraded, becoming heavier but each time with a more powerful engine to cope up. The last versions were armed with two 12.7 mm (0.500 in) Ho-103’s in the forward fuselage and the 1944 Ki-43-IIIb was armed with two 20 mm (0.787 in) Ho-5 cannons again in the fuselage. Better, but still weak compared to the Hellcat. Its wings were just too frail to accept machine guns… In fact, Nakajima only obtained their achivement by creating somehing structurally lighter than the Zero…

The Ki-43 “Oscar” was encountered in many occasions from 1943 as based in most Pacific island, later cut off from Japan. If many were destroyed on the ground and many sent to China, the Hellcat had plenty of occasions to deal with these in all operations up to 1945, the last used as Kamikaze. Slower, fragile, lightly armed, their only advantages were their dogfighting abilities… if they could come close enough. On this matter, the nimble fighter was able to outturn the legendary A6M2/3/5 at low altitude. It could outurn also everything flying, including the Hellcat, thanks to its ‘butterfly’ flaps, allowing for extremely tight turns in combat. But even in that area, experienced pilots were increasingly rare in 1944 to achieve all its potential. Even caught in a dogfight, the Hellcat’s sturdiness would have gave plenty of time for the pilot to “cash-in” without much harm, then disengage and find a spot to deliver a short burst, often sufficient to fatally cripple the flimsy machine, without armor and self-sealing tanks. At least the Oscar was the mount of the IJAF top ace, Satoru Anabuki, with 39 confirmed kills. It’s still pale in comparison of IJN’s Saburō Sakai (64)…

Versus the Ki-84 Hayate “Franck”

The Ki-84 was the natural successor to the army’s Ki-43 “Oscar”, and paralleled the A6M5 in many ways, notably engine power. After a first flight in February 1943 it was delivered from 1944, a very long development time which was in part it’s undoing. Nevertheless, Nakajima’s engineers managed the impossible and tried to keep as much agility they could from the magnificient hayabusa, but on a much stronger frame and twice as powerful engine. The Ki-84 (3,514 delivered) thanks to a Nakajima Homare Ha-45-21/25 18-cyl. radial delivering 1,522 kW (2,041 hp) at sea level, reached 687 km/h (427 mph, 371 kn) at 7,000 m and had a much better range and time to altitude. Since the danger was now coming more from USAAF Bombers, speed and acceleration came forward of its qualities of a dogfighters. Encounters thus became more frequent as the USN approached the home islands and in particular Kyushu.

It appeared from these, the Ki-84 showed excellent performance and high maneuverability, considered to be the best Japanese Army fighter to see large scale operations, and proved indeed a match for all models including the F6F and F8U. It proved also excellent to down high-flying B-29 Superfortresses, in part thanks to its powerful armament and better resilience (better than the Zero in that matter). They first were met over Leyte at the end of 1944 and it made good of its two 12.7 mm hmg in the nose and 2x 20 mm cannons in the wings, albeit a bit “light” compared to the F6F. In 1945 the last version had foir 0.50 caliber HMG in the nose and wings plus two 20 mm cannons in the wings, and other 30 mm cannons, or two 20 mm in the nose and two 30 mm in the wings, plenty of firepower when a F6F was cornered. Although records are ellusive on their kills over F8U and F6F, it appeared that they were superior in dogfights to the Corsair, having the advantages in armament, acceleration and climb rate.

Versus the German “butcher bird”

First off, the F6F was compared both to the A6M and probably best German “butcher bird” at the time, the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. Let’s start with a chief test pilot recollections registered in Patuxent Naval Air Test Center “Report of Comparative Combat Evaluation of the Focke-Wulf 190A-4”, after being just back from fleet carrier duty in early 1944, later promoted, Rear Adm. C.C. “Andy” Andrews, U.S. Navy. He was asked to start comparative tests between the F8U Corsair, F6F Hellcat and FW-190. Here are some points:

It was more heavily armed, with four 20mm cannon and two .30-caliber guns. With less ammo, it could just “point and destroy” it’s opposition, which was perfect given the rapid nature of the dogfights in 1944. Less time on the target to pepper it. On both points the six HMGs of the F6F and F8U were at a slight disadvantage. It was also less powerful, but made it for its smaller size, but still lacked speed and agility. Forward vision was poor compared to the two others. Its roll rate was slightly superior to the F6F-3. Diving abilities were poor. Being smaller and lighter, less sturdy, the Fw-190 vibrated excessively high diving speeds, quite alarmingly. It was not the case for the F6F. The Fw 190 also stalled with very little warning but recovered easily. It was also easier to achieve full power in the Fw 190 with its unilever control, better than the F6F-3, not the Corsair. Instraight line it was faster than the F6F-3: It came from 0 to 290 knots at 200 feet to 356 knots at 25,000 feet versus 0- 200 feet to 17 knots at 25,000 feet. Also, designed as an interceptor, it’s climb speed was way better than the Hellcat and Corsair: 165 knots versus 130 knots for the F6F-3.

F6F-3 over California, 1943

Pilots who made the test comparisons all agreed the Fw 190 was extremely easy to fly and designed for pilot convenience but not equal to the F4U-1 and the F6F-3 in dogfight, although it had many advantages, notably because it could outrun the F4U-1 and the F6F-3 in a 165-knot climb or faster. The simplicity of its cockpit was notable but it had more automatic features and pilots disliked having less direct control over variable settings and engine performance, yet again preferring F6F-3 in combat. This move to automation, less evident in Japan for technical reasons whereas the lack of pilot was as acute, dictacted to a radical drain of pilots towards the end of the war. Manufacturers were pressed to introduce these to speed up training and simplify the life of young recruits.

These comparisons between the FW-190 and F6F or Corsair are not fortuitous: British FAA pilots flying the Hellcat in several occasions met the FW-190 in combat, as much as the already hard-pressed BF-109.

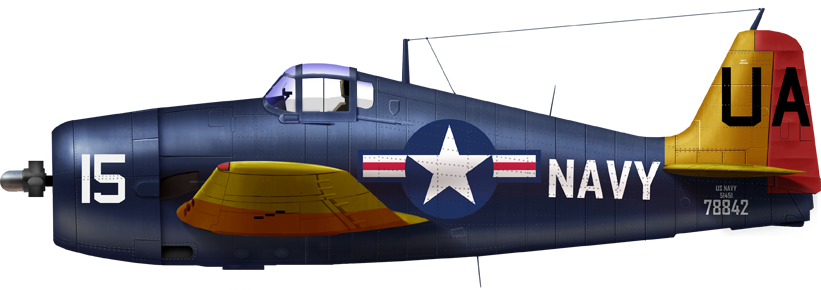

USN Hellcats

The U.S. Naval force very much wanted the more accommodating flight characteristics of the F6F over the Vought F4U Corsair, despite the latter’s better speed. This was detected early on, during deck landings, a basic achievement prerequisite, and the Corsair was rather delivered by the Navy to the Marine Corps to fight from land. The Hellcat stayed standard USN until the F4U series started to improve on some topics in late 1944, with deck landing issues solved by other ways like visual aids and experience returns from the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm operating it from 1943. notwithstanding its great flight characteristics, the Hellcat was just more forgiving to “rookies”, and that was its main selling point. After the crippling losses in 1942, the USN needed a brand new generation of pilots.

The Hellcat was robust enought to take the roughest landings as well as being shot at longer than expected, all leaving a fighting chance to inexperiences pilots. To keep up the airframe was adequately designed, and constantly improved during production as failings were analyses, built at the extreme to endure the routine of deck landings a gazillon times. Like the Wildcat, it was also intended for simplicity of production

Early Operations

F6F-3 of VF-2 (USS Enterprise) after a crash landing, burning, 10 Nov. 1943.

It saw activity against the Japanese on 1 September 1943, when USS Independence own fighters destroyed a Kawanishi H8K “Emily” flying boat, heavily protected. On 23 and 24 November, they were pitted in a more serious test over Tarawa, reporting 30 Mitsubishi Zeros destroy for the loss of just one F6F. For “rookie pilots” that was unexpected and rapidly constructed its reputation. Over Rabaul in New Britain on 11 November 1943, both Hellcats and F4U Corsairs fought all opposition during day-long battles notably with Army models and A6M Zeros, claiming 50.

Hellcats were carried by the Essex-class capital ships of TF38/58 and main instrument engaged in the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944. The famous “turkey shoot” really cemented for eons it’s repution of “butcher bird”. So many Japanese airplane were destroyed that what happened in the Marianas gave supreme confidence in the pilots, passed onto younger recruits.

Statistics

Kill ratio of allied fighters

In 1945, the F6F would represent 75% of all kills recorded by the U.S. Naval force in the Pacific. Radar-prepared Hellcat night-contender groups showed up in mid 1944. USN/USMC F6F pilots flew 66,530 sorties and scored 5,163 reported, accepted kills, so 56% of all USN/US Marines kills of the conflict overall, at an expense of 270 Hellcats in battle, giving the ultimate ratio of 19:1 guaranteed kills. Claimed were frequently misrepresented during the conflict and pilots claimed much higher figures, hard to confirm due to the ace and victory rules of the time.

So that amazing proportion was even a conservative one. Some argues it could be as high as 25 to 28:1. All things being equal the Hellcat performed well against the best Japanese fighters of the time, with a 13:1 kill ratio against the A6M Zero alone, 9.5:1 against the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate, best army fighter, and 3.7:1 against the Mitsubishi J2M, late Japanese interceptor in 1944. These success seemes impressive, but always had to be compared to the fact that from june 1942 onwards, they confronted progressively inexperienced Japanese pilots, enjoying the benefit of expanding superiority.

As japanese aviation started to vanish from the air (rather than sending inexperienced recruits dogfighting, units were retained for Kamikaze attacks), the air superiority role of the Hellcat started to be secondary and in 1945 sorties were usually for ground-assault where they still excelled, with rockets but more commonly bombs. In all, Hellcats dropped 6,503 tons (5,899 tons) of bombs until V-Day. Another aspect was it’s record-beating readiness ratio thanks to extremely well tought maintenance: “Its readiness factor” often exceeded 98%, appraoched by no other allied plane.

Throughout World War II, 2,462 F6F Hellcats were lost to all causes – 270 in dogfights 553 to ground and shipborne AA fire, 341 because of technical issues and various causes (like those burned in decks and hangars of CVs). Of the all out figure, 1,298 were lost of all causes combined, and many outside of the battle zones. And as production is concerned, it’s delivery pace was superior to any other naval plane, all manufacturers considered in WW2. So many were cranked up that at some point the Navy had no pilots for them. They were parked, waiting. In fact the industrial management team was so efficient that workforce turnover was very low, skilled labour stayed until the end of the war and managed to keep insane construction speed, helped by the initial design, only using simple geometric shapes and straightfoward, streamlined assembly.

The pilot’s take on the Hellcat

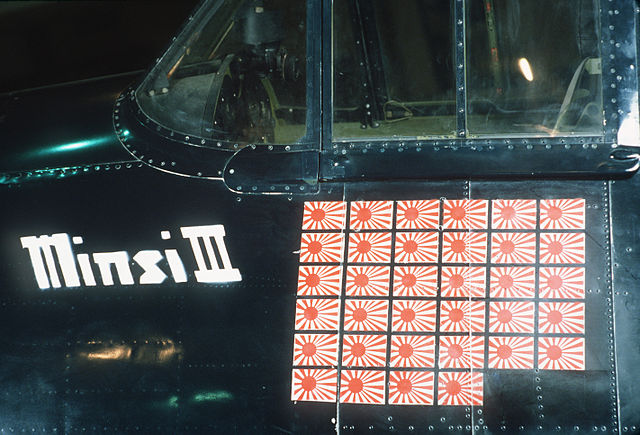

Dave McCampbell “Minsi III” hunting board

There was an unsurpassed expert pilot in the USN, Captain (ace) David McCampbell, with 34 victories, which once portrayed the F6F as:

“… an extraordinary military aircraft. It performed well, was not difficult to fly, and was a steady weapon stage, however what I truly recall most was that it was tough and simple to maintain.”

Hamilton McWhorter III, another USN pilot, and flying expert of World War II, credited with 12 victories, the only one turning into a twice ace in his first sortie.

Hellcat’s aces

There were some 305 Hellcat aces in the pacific, far more than in the Wildcat. Some earne dthem only on the F4U, like Ira Cassius “Ike” Kepford (16 victories) from VF-17 or Roger R. Hedrick (12), awarded the DFC which flew on VF-17/VF-84 with both, as P. L. Kirkwood. Other started their career on the F4F and transitioned like Elbert McCuskey and “Swede” Vetjasa read more.

- David McCampbell: 34 MH VF-15

- Cecil E. Harris: 24 NC VF-18

- Eugene Valencia: 23 NC VF-9

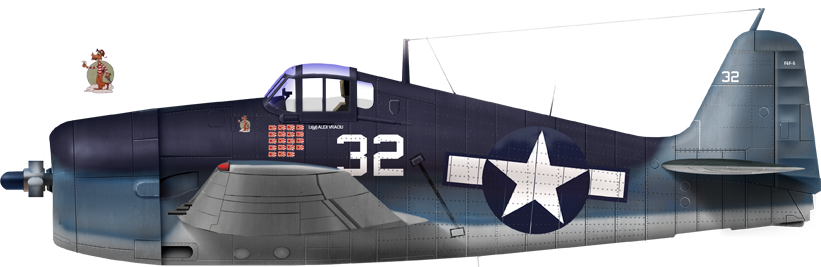

- Alexander Vraciu: 19 NC VF-6/VF-16

- Cornelius N. Nooy: 19 NC VF-31

- Patrick D. Fleming: 19 NC VF-80

- Douglas Baker: 16.3 SS VF-20

- Charles R. Stimpson: 16 NC VF-11

- Arthur R. Hawkins: 14 NC VF-31

- John L. Wirth: 14 NC VF-31

- Lt. Elbert McCuskey: 13.5 NC VF-3/VF-42/VF-8

- George C. Duncan: 13.5 – VF-15

- Roy W. Rushing: 13 – VF-15

- John R. Strane: 13.0 – VF-15

- Dan R. Rehm: 13 AM VF-8/VF-50

- Wendell V. Twelves: 13 – VF-15

- James A. Shirley: 12.5 – VF-27

- Daniel A. Carmichael Jr.: 12 – VF-2/VBF-12

- Roger R. Hedrick: 12 DFC VF-17/VF-84

- William J. Masoner Jr.: 12 – VF-19/VF-11

- Hamilton McWhorter III: 12 – VF-9/VF-12

- P. L. Kirkwood: 12 VF-10

Fleet Air Arm Gannets/Hellcats

FAA F6F-3 pending delivery at Bethpage, 1943

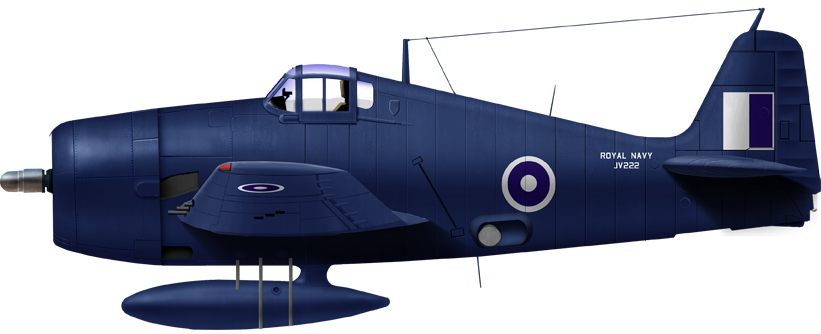

The British Fleet Air Arm (FAA) obtained some 1,263 F6Fs under Lend-Lease, named Grumman Gannet Mark I and by mid-1943 “Hellcat” to avoid confusion, the F6F-3 being becoming the “Hellcat F Mk. I”, the F6F-5, “Hellcat F Mk. II” and the night fighter F6F-5N “Hellcat NF Mk. II.” Read also

They saw activity off Norway, in the Mediterranean (notably Operation nvil Dragoon in August 1944 and over Italy until 1945, and naturally in the Far East. Some operated as recce models, with a visual surveillance gear The F6F-5P (Hellcat FR Mk. II) in the Pacific. FAA Hellcats moslty fought land-based airplane in the European/Mediterranean and their hunting board was far les impressive than USN pilots. They still globally revendicated 52 confirmed kills during 18 elevated battles in May 1944-July 1945. 1844 Naval Air Squadron (HMS Indomitable), British Pacific Fleet, was the best scorere with 32.5 kills.

Only two of the 12 groups flying the Hellcat in September 1945 actually kept them to the last, and were disbanded in 1946. All in all, Hellcats served with the 706 Naval Air Squadron Crew Pool & Refresher Flying Training School, 709 NAS Ground Attack School, 778 NAS Service Trials Unit, 891 NAS (not operational at V-day) as 1847 NAS, merged into 1840 and also never operational. In the East Indies NAS 800 (HMS Emperor) was the first operational unit flying the models, followed by 804 (HMS Ameer, HMS Emperor, HMS Shah, HMS Ravager), 808 (HMS Khedive), 888 (detachments only), 896 (HMS Empress), 898 (HMS Attacker/HMS Pursuer). In the Atlantic/Med threaters it was operated by the 881 NAS (HMS Pursuer), 892 (HMS Premier) and 1832 (HMS Indomitable). Pacific units operated it in the 885 NAS (HMS Ruler) 1839 (HMS Indomitable), 1840 (HMS Speaker), and 1844 (HMS Indomitable).

Postwar Use

F6F-5K Drone in 1946

F6F-5K used in the Bikini tests, 1946

Due to the end of the war, the production line was reduced to just completing the last variants and the last order was cancelled. The F6F was still maintained in active service in 1946, but gradually replaced by the F4U in 1947-48 and only maintained onboard as a night fighter, even though jets started to appear alongside. In 1949 it was officially retired from frontline service, and if some lingered a bit longer in training units, they were placed in reserve, all replaced by the Beacat which served a bit longer, until 1950.

Also in 1950 many were sold to the French Aéronavale, and the rest, were either scrapped, or converted. In 1946, the Blue Angels acrobatic team was created with veteran pilots, and they flew the F6F-5. It became the first model ever used by the famous unit. Their oiriginal glossy dark ocean blue became the basic color sported by all models ever since, as the yellow-orange fonts.

Operator guiding a taking off F6F drone

Modified F6F firing an experimental air-to air missile at Point Mugu, CA.

Another use of the Hellcat, long after the war, was as a Drone. It started early on, with the Bikini test, where the first, taking off with sensors onboard to test the result of a squadron flying right close to an atomic mushroom and fallout area. In 1948, the Hellcats were retired from all units, conversion started, with elaborated radio-command systems. The USAAF and well as the USN as some experience in these, already testing RC bombers for “suicide” missions in 1944-45. Instead, the F6F-5K were used as flying targets for the new jets. They were all brightly colored to be spotted easily by observers.

Several hundred of them were so converted, and some were guided from the ground, notably for missile tests, but other were guided in the air, by a control plane. In 1952, Unit 90 of Guided Missile used F6F-5K drones, each carrying 1 ton of bombs, to destroy bridges during the Korean War, heavily defended by AA. This was one of their rare wartime mission. These drones departed from USS Boxer, radio-controlled from an AD Skyraider.

In one occasion, in August 1956, a rogue F6F-5K “outwitted” a bunch of jet fighters. Operator lost control of the Drone, and signalled it as a potential hazard as the latter could run out of gas and crash into Los Angeles. The Oxnard Air Force Base’s 437th Fighter-Interceptor’s Northrop F-89D Scorpion which caught on the Hellcat, failed to shot it down. They tried their Mk 4 Folding-Fin Aerial Rockets (FFAR) “Mighty Mouse Rockets” assisted by their AN/APG-40 radar, but the drone, after circling over the city and then veering over the countryside, had a life of its own and started zig-zaging, effectively defeating the radar. They fired at first 64 rockets, failed and then their remaining 30 rockets manually, without results. Without guns, and out of fuel, they had to abandon the chase and go back to Oxnard, tail under legs. Meanwhile, the F6F-5K ran out of gas too and eventually narrowly missed Palmdale Regional Airport, glide-crashed in the desert nearby. Attempts to shot it down cost the area some 1,000 acres destroyed, forests and scrubland set ablaze, homes and property damaged. It took 500 firefighters to extinguish all the fires started by the rockets, 208 of them along the way, for nothing… src.

Drones will be used allon along the 50s and early 60s to test a variety of missiles, until its age made it less relevant. Douglas AD-4 Skyraider tested the AIM-7 Siwewinder against these drones, with modified racks underwings, carrying four of them from 1953 to 1956. This was one of its last contribution, to the mainstay of US and NATO’s air-to-air missiles inventory for the duration of the cold war and beyond.

Foreign operators

The Hellcat being a piston-engine model designed in 1942, it seems spent in 19148 when the last flew from US carriers, and only in their night fighting version. The rest were spent as drone, but many were kept in reserve in case of possible exports. But compared to perhaps more famous models, notably the F4U, Sprifire or Mustang, the F6F seemingly was not much used postwar for long or by many nations. The most active and largest postwar operator outside the US was France.

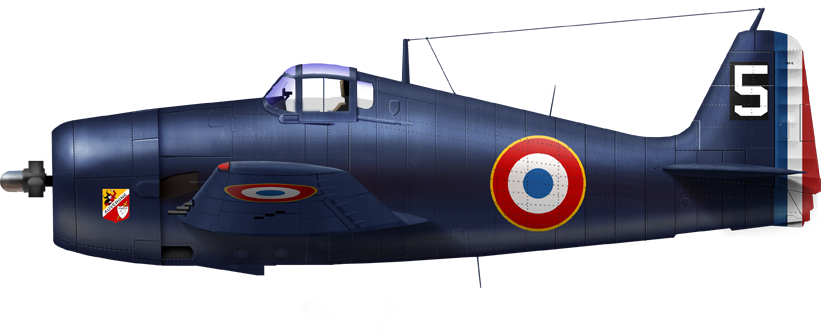

French Hellcats

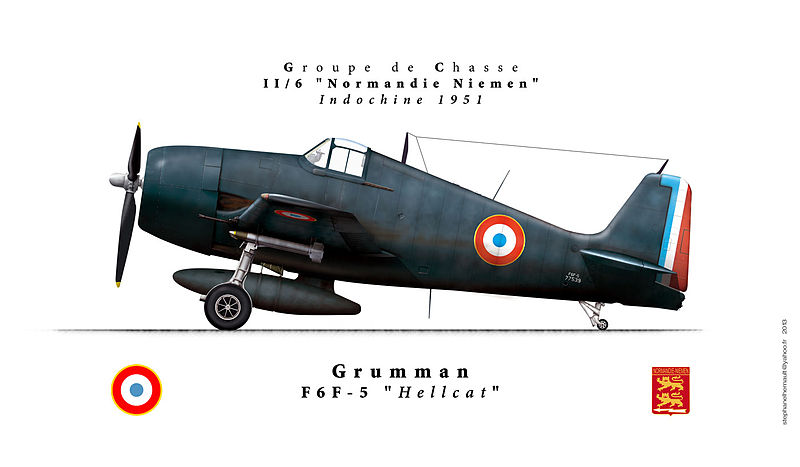

F6F-5 of the Normandy-Niemen Sqn. in Indochina, 1951

French F6F-5 of the Flotille 1F, FS Arromanches, 1951

In 1945 indeed, France already was gearing to war in Indochina and needed a modern fighter bomber park for its support operations. In this conflict, a commission These were the two pacific veterans, the F6F and F4U, and the F8F Bearcat. The French in 1946 indeed used Supermarine Seafire going with their postwar carrier, the Arromanches, former Colossus, leased from August 1946 and for five years, later purchased. She was the largest of all acquisitions with the smaller dixmude (ex-Biter) and two ex-Independence class. But in 1950, the Seafires, after four years of constant operations, were worn out, and had both landing issues and range limitations. Plus they had a limited payload in operation. The other support model used until 1950 was the now antiquated SBD Dauntless.

Thus, a commission sent in the US in the hope to purchase a large park of reserve/surplus planes, and settled on three models from the USN, outside those converted or modernized for new uses. The French Navy and French Air Force acquired first the F6F. They both deployed the Hellcats in Indochina from 1950 to 1952. The Aéronavale F6F-5 Hellcats kept their 1944 dark Sea Blue livery as USN planes until 1955, but with a French roundel and anchor. Four squadrons operated the F6F-5 under French colors, notably the pretigious Normandie-Niemen squadron, before transitioning to the F8F Bearcat.

They were used by the 11F (ex-1F) and 12F combat squadrons and in the 54S, 57S and 59S training squadrons. These saw heavy action over Indochina, notably oprating from FS Arromanches, Lafayette and Bois-Belleau. They were retired in 1960 and never took part in the Algerian war as pretended by some shaky sources.

The choice of the Hellcat was not immediate. Here is a recollection of the officers in charge of procurement in 1950:

Second in command of the 1/5 “Vendée” fighter group, present in Indochina from 1949 to 1950, I was called upon to participate, in the spring of 1950, in a commission convened by CATAC Tonkin and chaired by its chief, Colonel Mentrée. This meeting was attended by members of a combined US Navy/US Air Force mission, responsible for investigating the choice of combat aircraft that these branches planned to provide to the French Air Force in the Far East. (…) Questioned as a “fighter” expert, I proposed that the choice should bear on navy fighters, mainly for their take-off and landing characteristics, which in my opinion should be considered as essential, the others characteristics – armament, radius of action, air-cooled engine also being favorable to this choice. The American mission having then evoked the possible supply of Hellcat and/or Bearcat, this perspective was unanimously accepted by the commission, taking into account in particular the Spitfire experience.

Colonel Jean-Marie VAUCHY « Le choix du Bearcat » (1998)

Around December 1950, we were suddenly told that we were going to change equipment and be equipped with F6F5 Hellcats. It is true that our Spits were getting closer and closer to exhaustion and that their availability was collapsing. We therefore detached 2 lieutenants from the sailors of the naval aviation of Hyères who used this type of plane and a month later they returned to Saigon (…) this Hellcat was a peaceful machine, looking a little clumsy, practically devoid of faults, solid, heavily armed and equipped in surplus with the famous P&W R2800, an engine which gave the impression, once started, that it was about a diesel that nothing seemed to be able to stop.

General Jean RAJAU « Histoires de transformation des pilotes en Indochine » (2002)

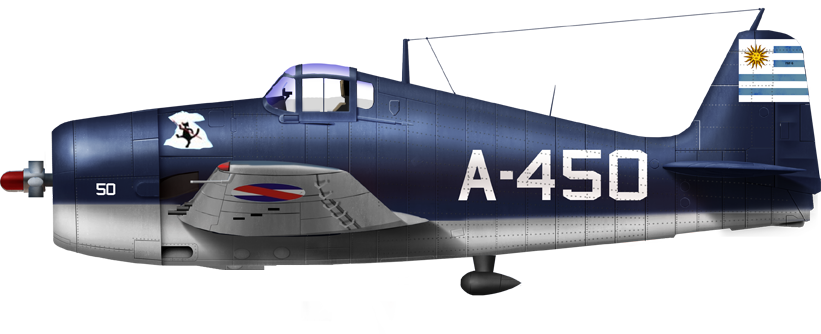

Uruguayan Hellcats

The Uruguayan Navy also used them until the early 1960s. Deliveries started in 1947, with recently mothballed models and twelve Uruguayan aviators were invited to test it; Other solutions were envisioned by the government, namely the Bearcat but the US Government rather pushed to the adoption of a mix of F6F-3, 5 and 5 FN. Eventually twelve F6F-5 were adopted and beloved by their pilots, as reported from Fort Worth, Texas, where they trained. Once in service, they however over time showed engines issues, perhaps as being worn out or lacking skilled maintenance teams. These went on to serve with the xxx until 1960, May, 25 during a military parade. At that point three were lost already.

Contrary to some sources they were not painted green but retained their originaly glossy dark ocean blue livery with light gray undersides, and national ensigns, including the anchor as they served all with the naval aviation.

Legacy

Due to its large production and historically significant career, about 66 F6F were preserved over the years or restored in flying conditions as of today. To compare to the F4U, this is a few, the latter having over 220 preserved. Nevertheless, the F6F can be seen in all significant aviation museums in the states, but also around the world in static version. Many joined private collections or memorial flights in the states, rekligiously maintained and exhibited to the public, doing stunts and blasting their loud Pratt & Whitney. Personally i encountered a former Indochina war version when in Ferté-Alais, France, and was struck by the particular noise of the engine, and surprising speed for something that squarish. Seen from close, it was indeed massive, deserving the nickname “jug” as well as the P-47.

In the United Kingdom there is a single F6F-5 #79779 in the Fleet Air Arm Museum in RNAS Yeovilton. For the US, plenty, F6F-3s at the National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola in Pensacola, Florida, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia, San Diego Aerospace Museum in San Diego, Californiaand the Naval Air Station Wildwood Aviation Museum at Cape May Airport in Lower Township, New Jersey. F6F-5 at the Naval Air Facility Washington at Joint Base Andrews (former Andrews AFB) in Maryland, New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, USS Yorktown/Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Air Zoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan, National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola in Pensacola, Florida, Cradle of Aviation Museum in New York. It is on loan from the USMC Museum in Quantico, Virginia.

Those in flying conditions, F-3 are at the Collings Foundation in Stow, Massachusetts and one privately owned in Houston, Texas. The F6F-5 are flown at the Commemorative Air Force (Southern California Wing) at Camarillo Airport (former Oxnard AFB) in Camarillo, California, Fagen Fighters WWII Museum in Granite Falls, Minnesota, Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington, Erickson Aircraft Collection in Madras, Oregon and Palm Springs Air Museum in Palm Springs, California.

US Navy Gallery:

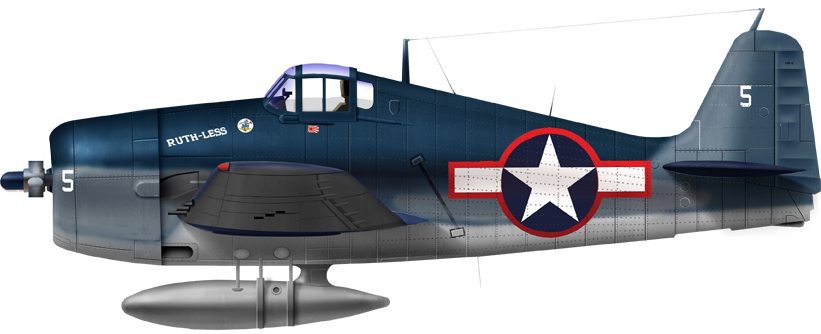

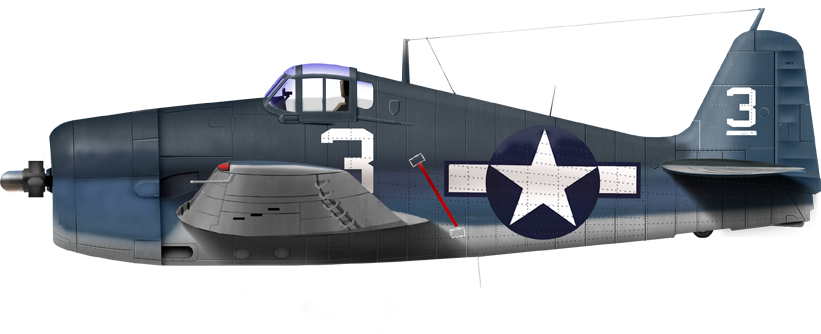

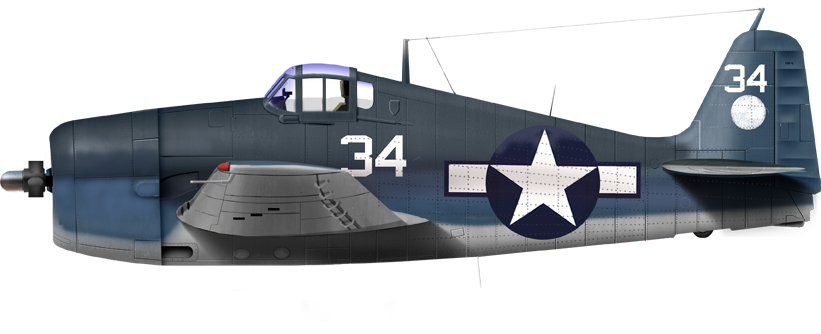

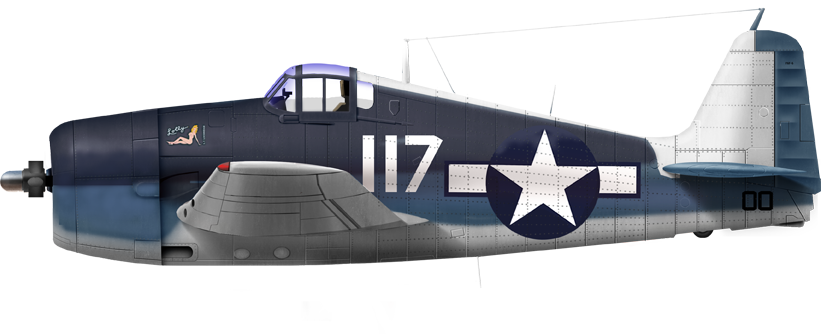

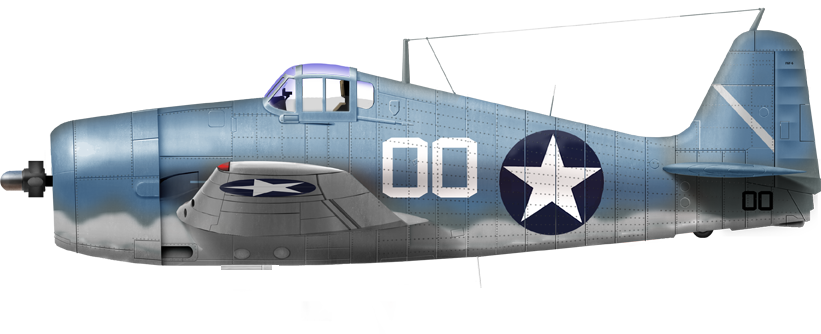

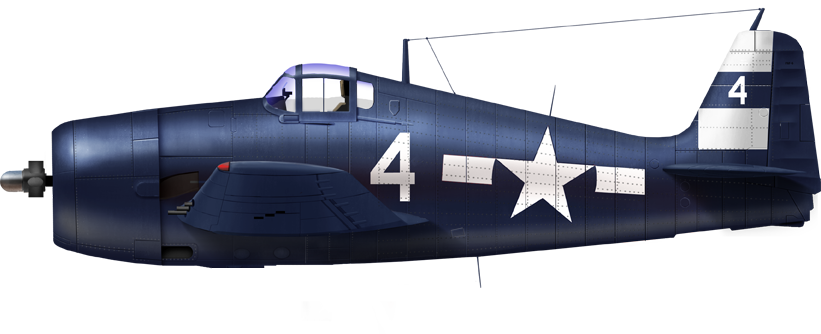

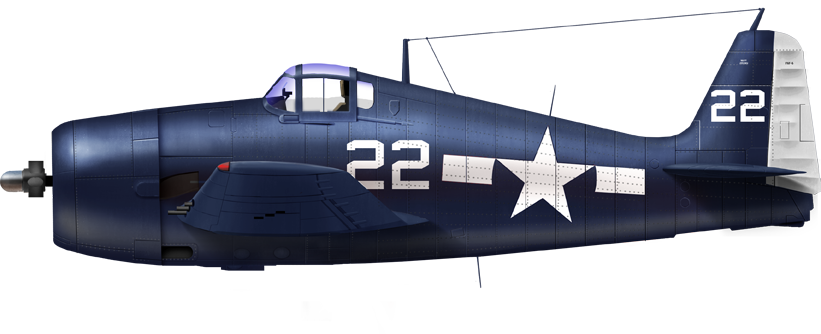

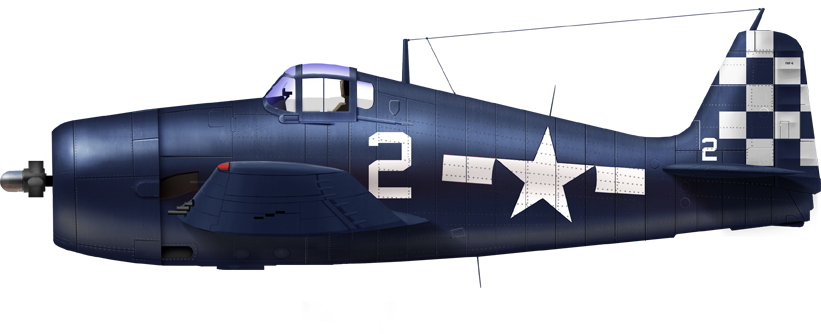

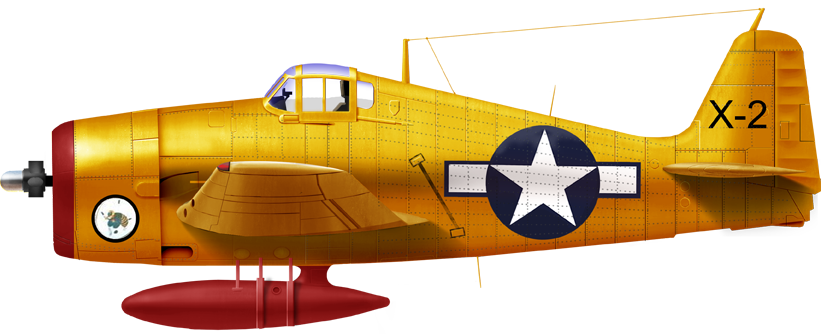

F6F-3 from VF-38 “ruth-less”, summer 1943

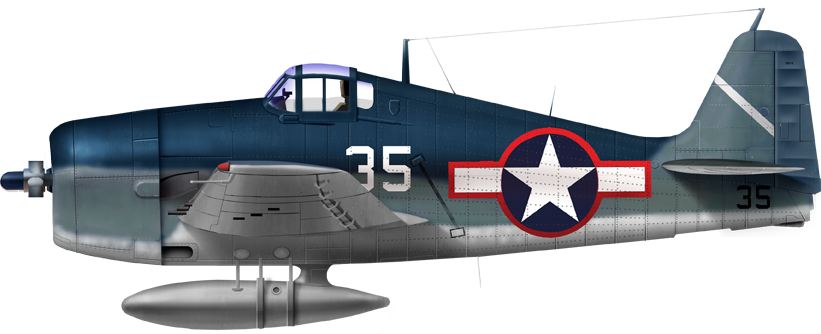

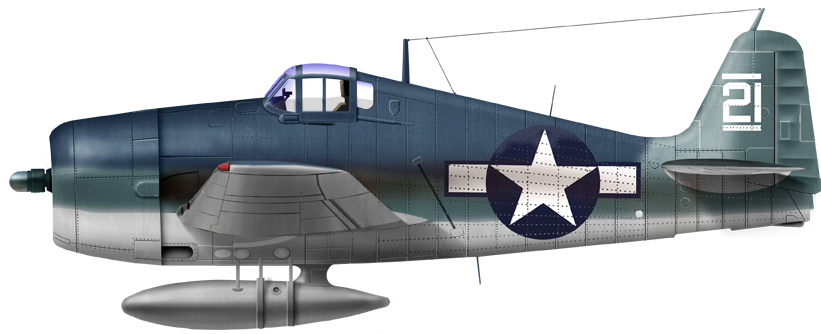

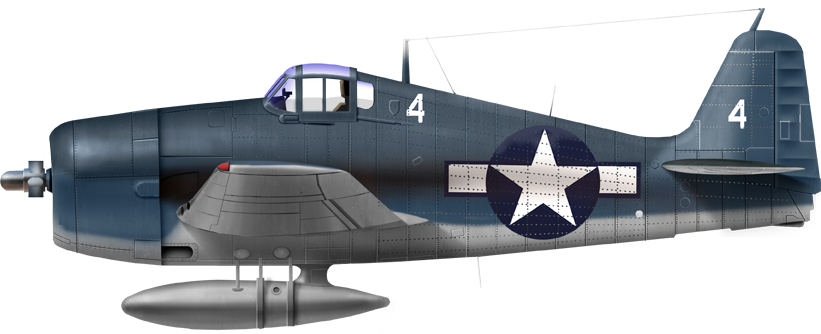

F6F-3, VF-5 USS Yorktown, August 1943

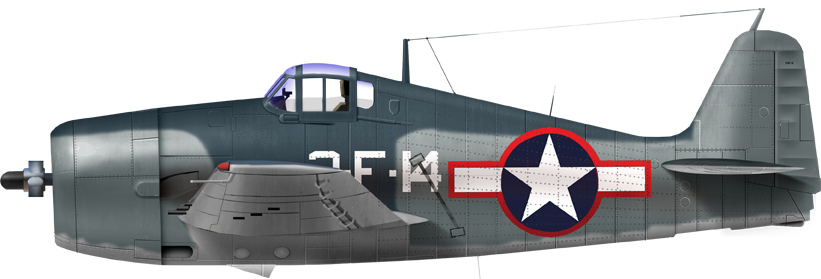

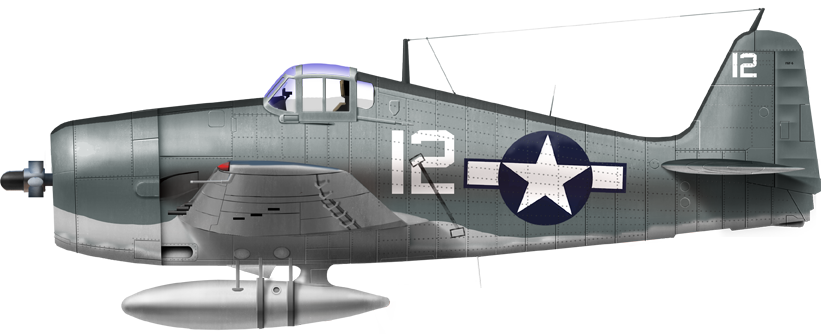

F6F-3, VF-8 USS Intrepid, summer 1943

F6F-3, ace ‘Harold E-handsome Hal’ Vita, VF-9 USS essex, September 1943

F-3 VF-6 USS Enteprise 1944

F-3 from USS Hornet, March-Sept. 1944

F-3 “lolly” in September 1943

F-3 James H. Flatley CVAG 5, USS Yorktown, May, 6, 1943

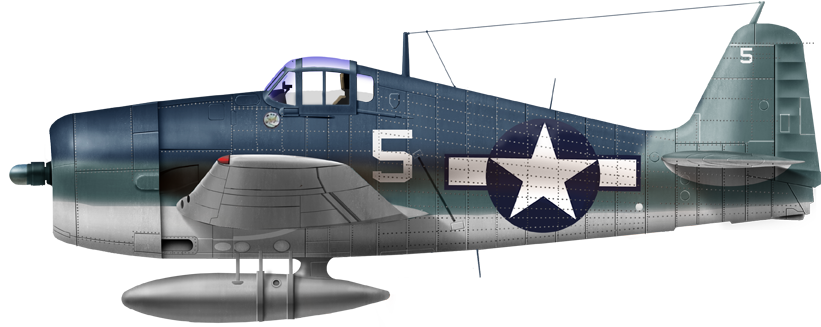

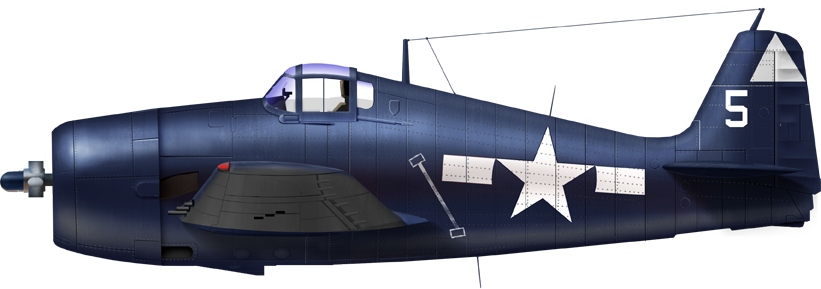

F6F-6 white 5 Hadden VF-9, February 1944

F-3 (FV-9) USS Essex, 1944

F6F-3 Lt.L.A. Edmonston, VF-34, Nissan Island, May 1944

F6F-3, VF-7 USS Hancock, June 1944 shakedown cruise

Unknown F6F-5, 1944

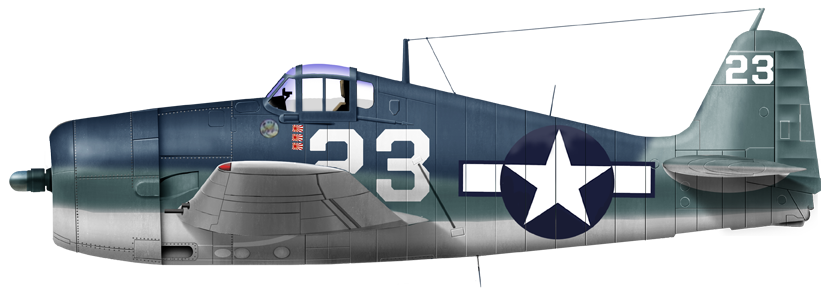

F6F-3N (night fighter version) from VF-2 USS Hornet June 1944

F6F-5 VOF-1, VCE-72 USS Tulagi, Op. Anvil Dragoon, Southern France, August 1944

F6F-5, VF-20, CV-6 USS Enterprise, August-November 1944

F6F-3 USN Ace Alex Vraciu, USS Lexington (CV16), summer 44

F-5 VF-18 USS Intrepid, September 1944

F-3 VF-8 USS Bunker Hill, October 1944

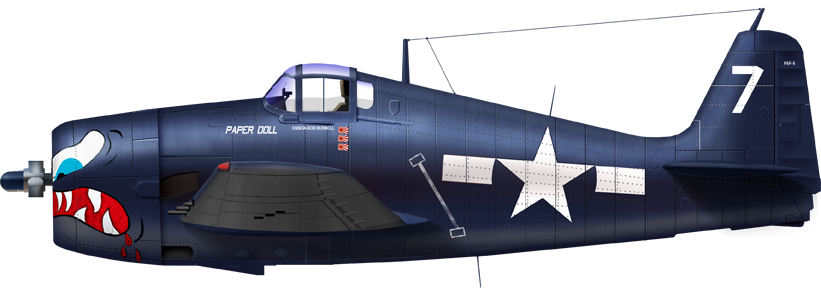

F6F-5, VF-27 Robert Burnell, USS Princeton, October 1944

F-5 VF-14 US Wasp, May November 1944

F-5 VF-18 USS Intrepid, July, November 1944

F-5 Hamilton McWorther VF-9, USS Hornet, March 1944

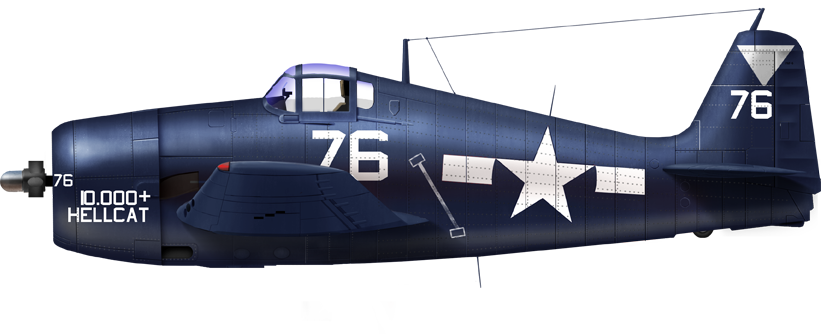

10,000 th Hellcat in production in 1944

F-5 USS Suwanee, 1945

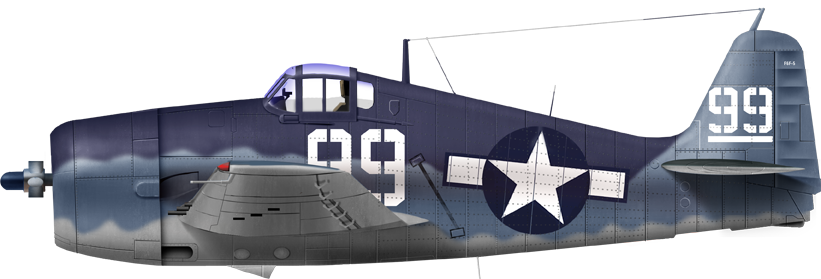

F-5 VF-17 (CV-12) USS Hornet, March 1945

F6F-5P, VF-84 USS Bunker Hill 1945

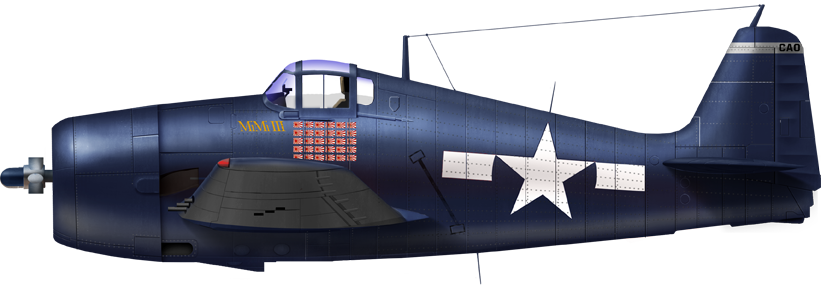

F6F-5, VF-15 USS Essex, 1945. “Minsi III” flown by top ace David Mc. Campbell. The tail “Cag” was a unique marking proper to him, the Cmmander Air Group. A modern replica was done of this livery on a flying F6F today as part of the Commemorative Air Force.

F6F-5, VF-23 USS Langley 1945

F6F-5 Lt. Navy ace Hamilton Mc Worther (VF12) uss Randolph, January 1945.png

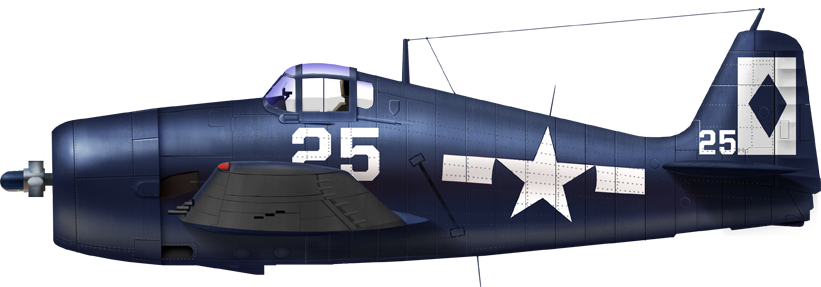

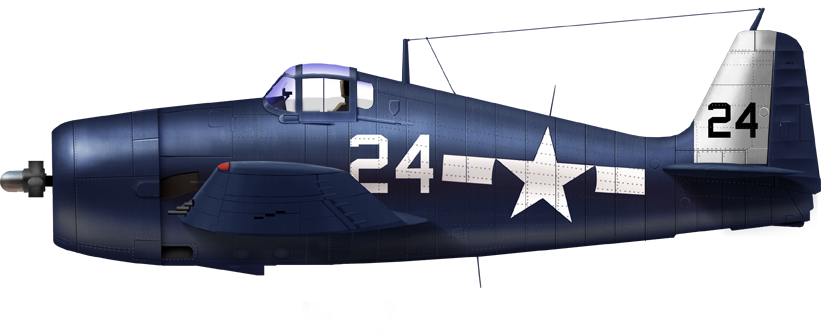

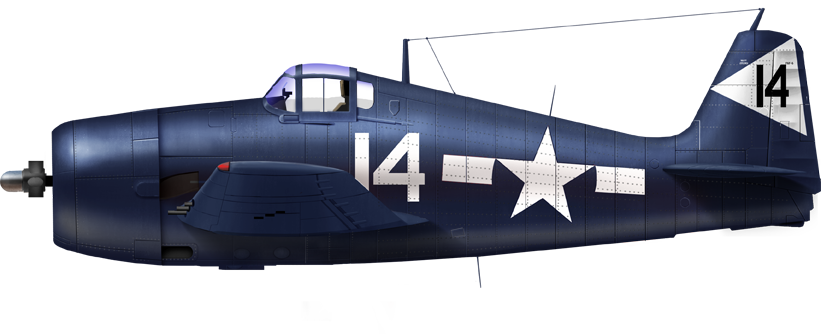

On Independence class carriers, 1945

F6F-5 from USS Bataan, CVL-29

F6F-5 from USS Monterey, CVL-26

F-5 from USS Cabot, CVL-28, 1945

F-5 from USS Cowpens, CVL-25

F-5 from USS Belleau Woods, CVL 24

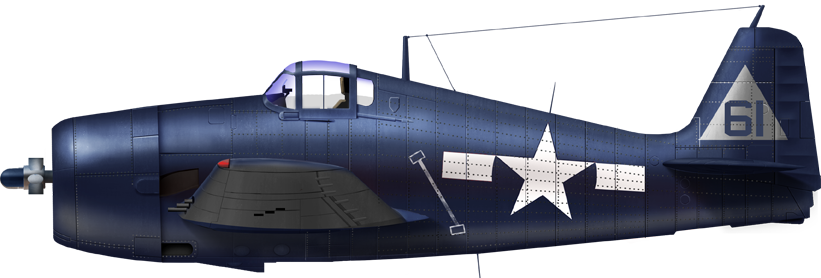

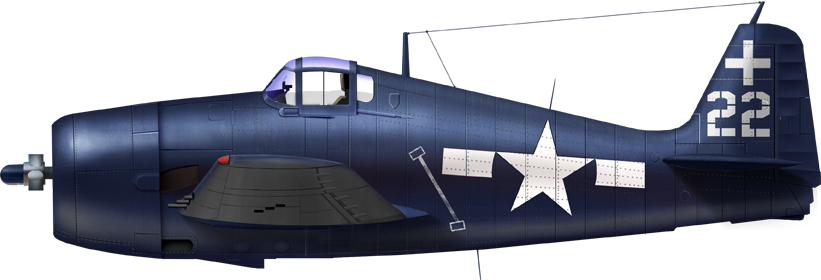

F-5 from USS Independence, CVL-22

Gallery: Wildcat in FAA service

Hellcat MkII FAA, Sqn. 888 HMS Indefatigable 1945

(More to come).

Gallery: Cold War Wildcat

F6F-5P from VF-5B, USS Coral Sea 1948

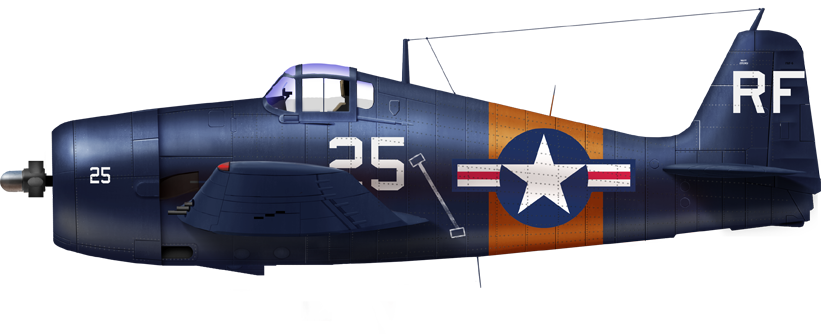

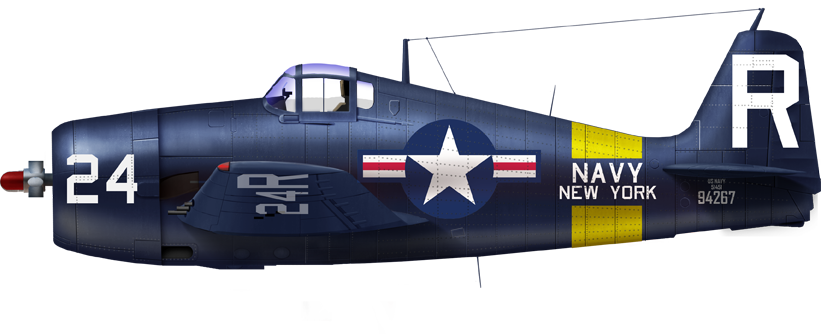

F6F-5 NAS New York Training unit, 1947

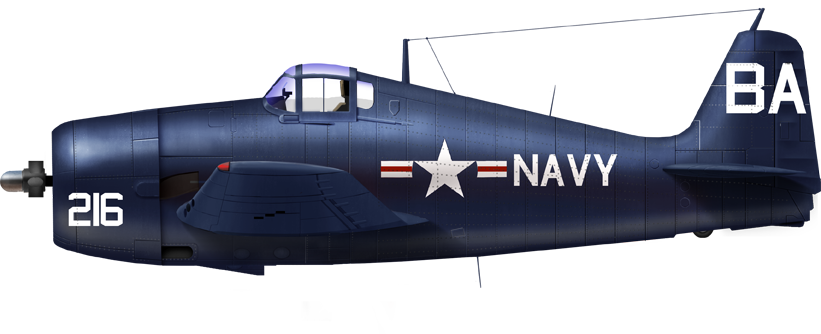

F-5 USN reserve, NY NAS, 1948

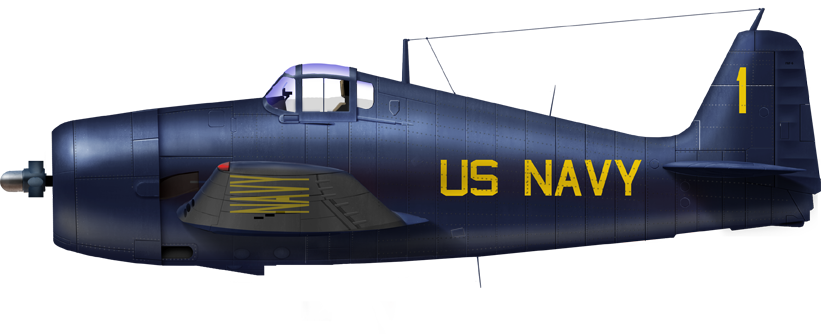

F-5 of an unknown postwar unit

F6F-5 Blue Angels, 1946

F6F-3 drone NAS Johnsonville, Penn.

F5K drone, VU-1 Oahu, Hawaii, Sept. 1959

F-5 of GC-II/9 “Auvergne” at Tan Son Nhut, French Indochina, 1952

Uruguayan F-5 CC. Omar Aguirre, 1952

Photos

Cdr David McCampbell, cdts navsrc