Category: ww2 USN Aviation

Curtiss F11C Goshawk

US Navy Fighter, 27 USN, +3 protos +129 exports The Curtiss F11C Goshawk is now a somewhat forgotten USN naval…

Boeing F4B (1928)

US Navy Fighter (1928-34), 187 built (and 366 P-12) Development For the Navy, the Boeing Type 99 The based model…

Boeing FB (1923)

US Navy Carrier Fighter (1933), 37 built The Boeing FB.5 was a biplane fighter used by the United States Navy…

Martin T3M (1926)

US Navy Torpedo Bomber (1926-32), 124 built. The Martin T3M is a 1926 carrier-borne torpedo bomber, introduced a year before…

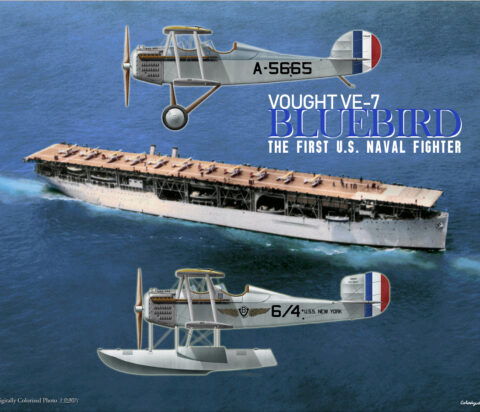

Vought VE-7 (1917)

Vought VE-7 (1917) Naval Fighter – 128 built The Vought VE-7 “Bluebird” was an early biplane of the United States….

Curtiss SC Seahawk (1944)

Catapult-launch observation floarplane, Curtiss 97B USN Carrier Fighter (1944-1949, 577 built) The USN last onboard floatplane The Curtiss SC Seahawk…

Curtiss SB2C Helldiver (1942)

Curtiss SB2C Helldiver (1942) US Navy Dive Bomber (1943-45), 7,140 built The Curtiss SB2C and its “bad rep” A bit…

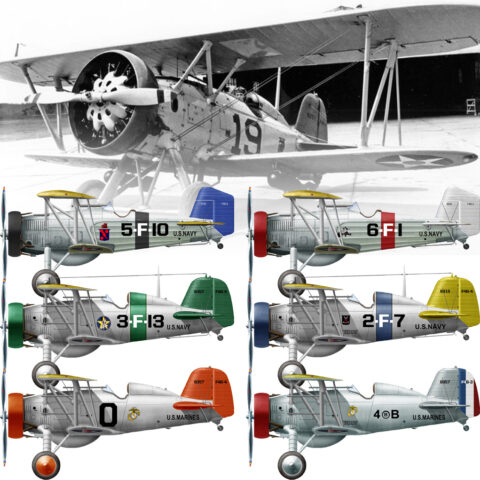

Grumman F2F (1933)

Grumman F2F (1933) Single seat biplane naval fighter Design Development The outstanding performance of the Grumman FF-1 “Fifi” two-seat multirole…

Curtiss SBC Helldiver (1933)

Curtiss SBC Helldiver (1933) USN Carrier Dive Bomber 1935-1940 (257 built) Curtiss biplane dive bomber The Curtiss SBC Helldiver was…

Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger (1941)

Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger (1941) US Navy torpedo-bomber (1941-1968), 9,839 built The well named “avenger”, Juggernaut of retribution The Grumman TBF…

dbodesign

dbodesign