The Curtiss SO3C was supposed to be the main reconnaissance and spotting floatplane in service on board capital ships, cruisers and aircraft carriers of the US Navy, in its convertible versions. However it was a rather mediocre seabird, for multiple causes in part imptuable to the Navy itself. Plagued by many issues that were never satisfactorily resolved and only served on a few cruisers for a short time (2-3 months) most, being lost in accidents. The 800 built in 1942-44 were passed to lend-lease or converted to ground uses, replaced whenever possible by the Vought Kingfisher, older but far better, or even the SOC biplane it was suppose to replace. Together with the poor results of the SB2C Helldiver, it did not improved the image of Curtiss with the Navy.

Genesis of a rather mediocre seabird…

Although Curtiss was quite a household name, at least for USAAF, experiences with the USN were far less stellar, although it started rather well, with the prolific JN-4 “Jenny” back in 1915, and following the end of the war and drastic orders reduction, the firm was still able to win contracts for the main onboard fighter, the F8C-1 and F8C-3 Falcon (1927-28) and later the F8C-4 Helldiver dive bomber, or the appreciated Curtiss SOC Seagull (1934), a reliable convertible biplane that Curtiss naturally wanted to replace and proposed the Navy a monoplane.

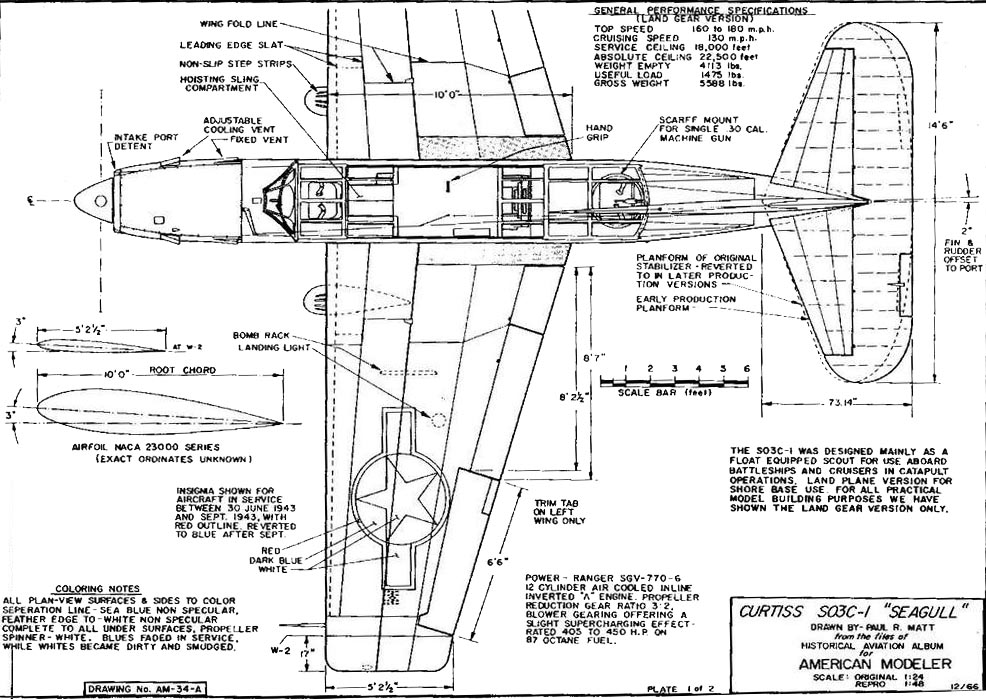

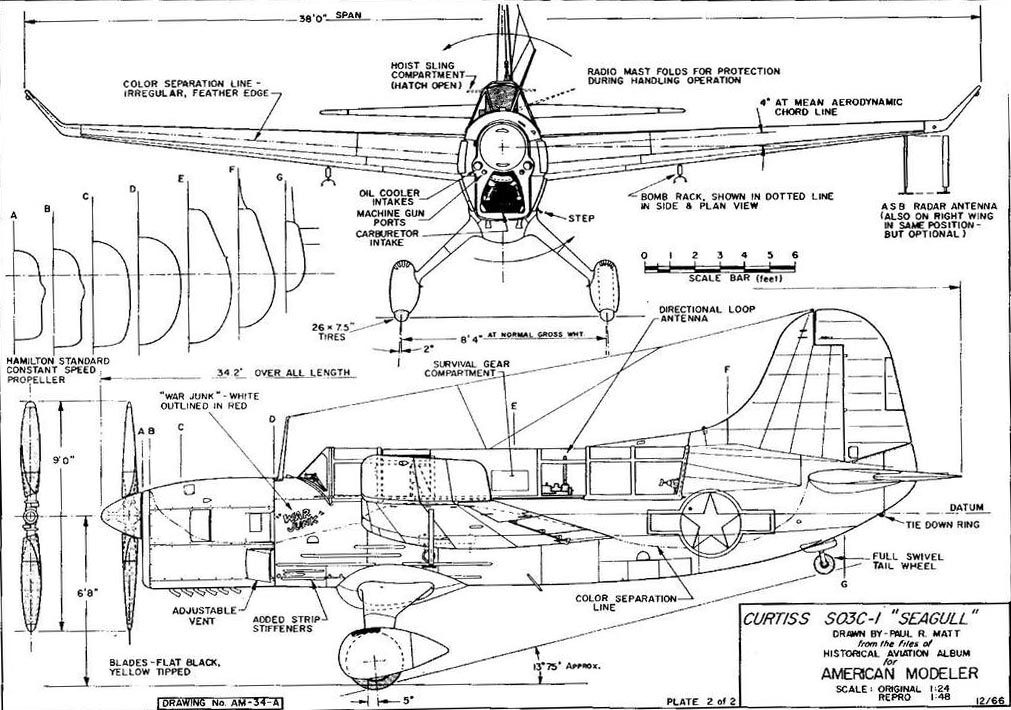

Back in 1937 when it was needed to replace the Curtiss SOC, the former and Vought were asked by the USN to study a prototype each, and on basis specs: Mid-wing monoplane and crew of two (pilot.observer), fuselage single main float to be replaced by a land gear with ease, and wings able to be folded back for storage in cruisers or aicraft carriers, and 6,300 Ibs max at takeoff. But the most stringent requirement was a very specific engine: The existing and still largely experimental air-cooled 7 liters inverted V-12 from Ranger Aeronautics. A promising design, yet untested, which was lighweight, well-profile to reach better speeds, and overall promised to be very fuel-efficient, thus almost doubling the range. Something that was highly praised for a navy scout.

The new design that emerged from both company’s seemed to match the requirement, with a fuselage larger enough for three crew member under the main canopy, stressed aluminium throughout (unlike the SOC, still canvas-wrapped) and the liquid-cooled inline V12 engine asked for. For aerodynamical reasons, Curtiss also tended to appreciate speed gains reached with such engines, as proven by its winning participation in the famous Schneider cup floatplace races at that time, but still expressed doubts about its unproven nature.

After, all, apart Packard, in the USN or USAF, everybody trusted the very reliable radials provided to almost all models in service. With insight, the Navy’s choice of that Ranger engine proved disastrous to say the least, and would have doomed Vought’s own model as well. While all aerodynamic problems were claimed as fixed, in part using radical approaches, the unreliable and underpowered engine remained it’s undoing.

The Curtiss SO3C model (a code corresponding to the constructor and its function) was developed on paper and submitted in August 1937 and by May 1938, awared a contract to proceed with a working prototype. Whis was done with celerity. The XSO3C made its first flight, with fixed undercarriage, above the Curtiss-Wright airfield on 6 October 1939. The test pilot was not impressed, and pointed out rapidly very serious flaws, grave inflight stability issues, and a very weak, overheating engine, the Ranger air-cooled, inverted V-shaped inline engine. Contrary to for example Pratt & Whitney, which stuck with classic radials, Ranger at the time (“Ranger Aircraft Engine Division”) was a subsidiary of Fairchild, specialized in inline engines (see later). In short, this engine fell short of all expectations in service.

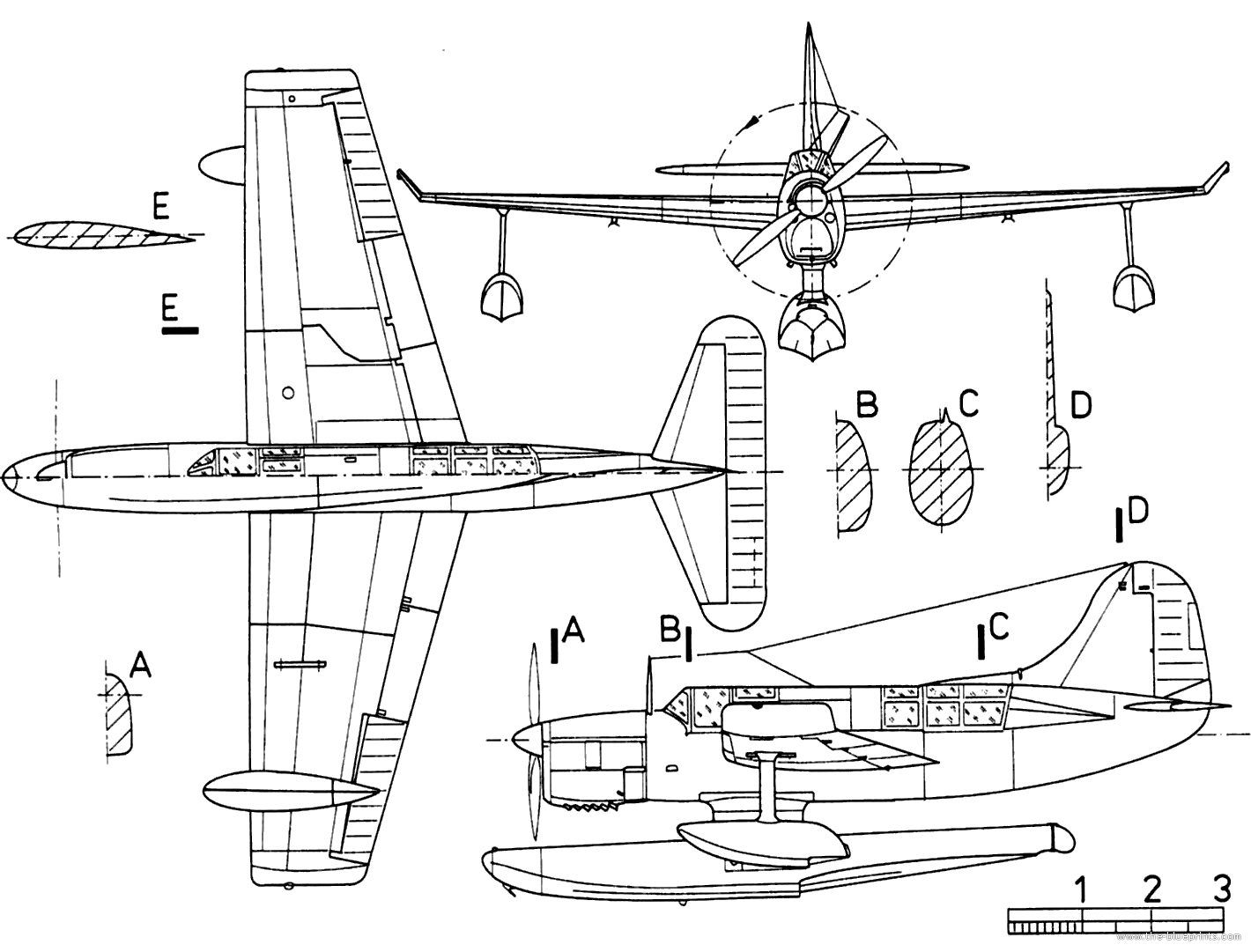

Vought XSO2U-1. Same engine, but lightly better performances only due to aerodynamics. This is the later float version. The early one was fitted with the wheeltrain undercarriage caracterized by a lighweight double V struts attachments. It was also sleeker, faster of 3 mph, but heavier of 300 Ibs.

XSO-3C-1

An official competition took place to replace the SOC, notably competed by Vought. Later, it was tasked to find its own successor with the OS2U Kingfisher. Despite its engine issues (the same Ranger V-770), the XSO2U-1 was not considered overall superior to the XSO3C-1, much heavier for a meager gain in speed. however, Vought’s production capacity was already taken up by manufacture of the OS2U Kingfisher.

An initial order for 300 was placed right after Curtiss was chosen and the contract awarded. However well before the first left the factory, by March 1940, Curtiss sent the prototype to the Navy for final trials, completed with the undercarriage and floats, in order to test both configurations. They showed rather grave cooling and stability issues. The cooling issue in particular has been observed with the Vought prototype as well. In fact, the engine overheated so much its test was curtailed to avoid an engine fire in flight.

As time progressed, Curtiss was hard-press to fix his new bird’s glaring problems, and by intensively using wind tunnels, started in late 1939 and continuing in early 1940, found the best approaches to improve the aerodynamic instability. If one solution was rather class, designing a taller tail, other were less: Engineers choose to add a dorsal fin section that extended over the rear observer’s cockpit. This was a long and iterative process.

The problem of stability resurfaced when the sliding canopy was open, breaking this tail surface, which was practicaly each time the plane was in mission, as this was the observer’s post. For cooling, the air intake below the propeller was enlarged.

Curtiss XSO3C in wind tunnel, 1940

The second way to deal with the stability problem was rather unique, and proper to this model. With the inline engine, this made the Seamew immediately recoignisable: The introduction of upturned wingtips. This radical solution had to resurface many, many years later with the famous “winglets”, and this was solution deduced from wind tunnel tests. This made the wingtips of the SO3C, from rounded, to squared, then raised by following a curve, not with a clear break. On 31 July 1941, the prototype was making floating tests and failed completely, sinking. Recuperated and repaired in Buffalo it failed again in November.

Finally the Ranger XV-770 engine could not be replaced yet, nor improved easily by Ranger, proved in the end a dismal failure, even after many attempted modifications. It delivered far less than paper specification, in addition to overheat, and resulted in poor flight performance, only equalled by its terrible maintenance record. This alone doomed the SO3C, which otherwise could have replaced as intended the SOC Seagull, but ended recalled and replacd by the biplane it was supposed to replace ! These problems, back and forth with the wind tunnel team and engineers from Ranger made the development dragging on, with more flights, until late 1941.

XSO3C-1 tested in a lake

Production went on meanshile ansd the first were delivered in mid-1942. NACA tests at Langley Field solved some issues, notably those related to stability, but the engine remained the main problem. By that time; the USN had adopted the custom of complementing official USN acronyms by names. In the SO3C case, it was the “Sea Mew” but originally in 1940 it was “seagull”, as replacing the older SOC. Strangely “seagull” was retroactively given to the SOC when it came back into service to replace the …seamew.

The company in early 1943 was asked to solve the remaining numerous issues of production models. One of the most critical, outside the engine’s numerous shortcomings, observed in service:

1-Inability to make a water takeoff with full gasoline load. But this was the result of a design revision after production started to increase the tank capacity in a drastic way. The original model was not designed for such gasoline load, but almost half of it. As a result, pilots tended to only less than half-fill the tank to take off.

2-In rough waters, the float flexed so much so, given it’s implementation very close to the nose, the propeller would actually strike it…

3-The take-off attitude was mediocre as the Seamew tended to be “sticky” to the excess, the pilot having to punch the engine full-throttle, causing overheating but also very steep, causing a full aileron control loss. In case of any lateral gust of wind, it could not be recovered and the crash was guaranteed.

At the end of 1943, Curtiss introduced a lightweight version, stripped of many features like the catapult specific equipments (meaning it was now only usable on carrier decks or coastal bases), equipped with a more powerful SGV-770-8 engine. Designated SO3C-3 (internal denomination Model 82C) the USN ordered 659 of the new version, until it was decided it was still not good enough.

Curtiss also worked on a derivative, hunting down more weight, to reintroduce lost features and make it catapult-capable again, as the SO3C-4, and was confident enough of its adoption by the British Royal Navy as the Seamew Mark II. Alas, reports came out from the initial preserie of this new batch as been not that successful, especially compared to the kinfisher for example, and the Navy decided to cancel the order after 39 has been delivered. In its place, the older Seagull went on into service until 1945…

Design

The XSO3C-1 aircraft was of all-metal construction except for the fabric-covered control surfaces. The crew of two, pilot and navigator, was seated in tandem in fully enclosed cockpits, but far apart. The navigator had a revolving seat, in order to operate the radio and maps inside the englassed section towards the pilot, or backwards to man the single defensive machine gun.

It had a main axial float and supporting smaller floats under struts located to the ends of the wings. The wheeled chassis was was a “V” type one, quite visible with its large fairings, an obsolete feature at the time, and a small tailwheel. This was not a successful configuration for landing, but the only one possible for a quick change between the wheeltrain carriage and floats.

The engine had a very unusual appearance, and indeed presented, while ambedded in the fuselage a relatively small frontal surface, making for an excelent penetration as shown NACA tests. Even the placement of the cylinder exhausts, under the nose rather was on the sides, proved another good profiling decisions.

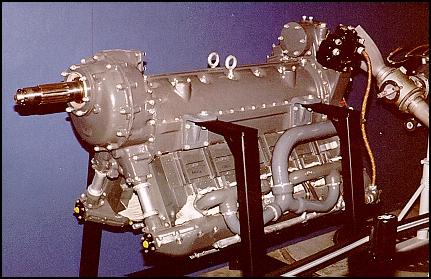

The Ranger V-770 engine

Ranger V-770 Inverted Engine

The Ranger Aircraft Engine Division of the Fairchild Engine & Aircraft Corporation was created in 1925 to produce the promising Harold Caminez’s 447 engine, which developed 120 hp but used innovative technologies to manage the internal cooling, the main concern with such engine configuration. After a Fairchild 6-307A, the Ranger 6-370B, then 390B and finally the 135 hp 410B, Ranger was practically the only provider of aircraft inline engines with Packard in the US.

Then finally the company based in Farmingdale, New York, produced the inverted 6-cylinders L-440 rated for 175 hp, which went to a variety of Fairchild trainers and the Navy seaboat Grumman Widgeon, which was appreciated in 1940 by the Navy and probably draw some attention of Curtiss early on. Indeed, as part of the requirements were specified an inline engine, less susceptible to corrosion was seawater, as it was placed in front, over the float, unlike many other seaplanes using the overwing position, out of harm of sea spray.

Ranger was contacted to simply double the number of cylinders, in a more conventional V-12 configuration to reach the desired output of 520 hp. The inverted V-770 engine was to be its crowning achievement and quite unique in US history.

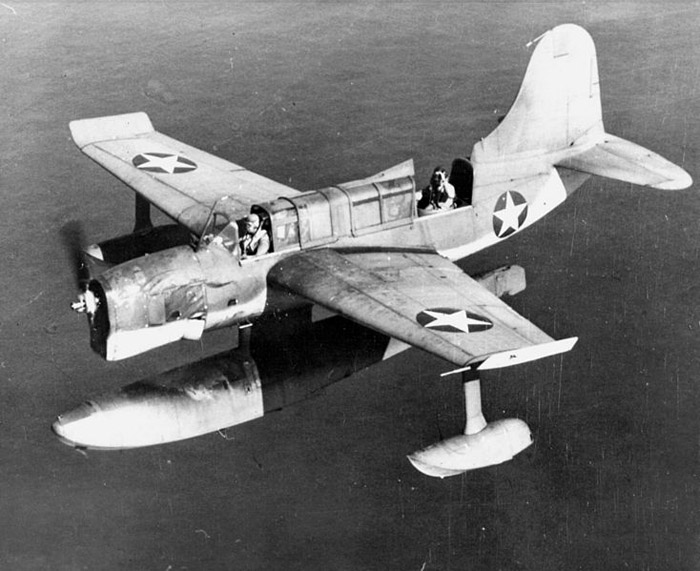

Fresh production SO3C-2 in flight

The V-770 was used on the Vought XSO2U-1 prototype to replace the SOC biplane, just like the XSO3C, and was its main competitor, flying earlier, in July 1939. However, if the engine was equally disastrous on this prototype, the SO3C was chosen only the ground of industrial capacity. There is little doubt the serial SO2U would have been equally mediocre overall.

The V-770 featured:

-A two-piece aluminum alloy crankcase

-A steel cylinder barrel

-Integral aluminum alloy fins

-Aluminum alloy heads.

Armament of the Seamew

Technical Plan

The Seamew carried only two machine guns: One light, a Browning 0.30 in M1919A4 (7.62 mm) forward firing in the nose canopy with interruptor gear, and a single 0.50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning heavy machine gun located in the rear cockpit. However it had a limited arc of fire due to the enclaved position of the rear cockpit, even with the glass canopy sloded open forward: Between the tail and fuselage, it perhaps had a 30° arc either side, limiting defence to “lucky shots”. In addition, on paper, the Seamew could carry two 100 lb (45 kg) bombs or alternative 325 lb (147 kg) depth charges underwing. There was a version with a ventral bomb rack on the C-2 (in landplane configuration) but its poor performances meant it probably never carried bombs.

curtiss SO3C Caracteristics |

|

| Dimensions: | 11.58 x 11.23 m x 4.58 m (36 x 38 x 4.57 ft) |

| Wing area: | 290 sq ft (27 m2) |

| Weight: Light | 4,284 lb (1,943 kg) |

| Weight: Max take-off | 5,729 lb (2,599 kg) |

| Propulsion: | Ranger V-770-6 600 hp inverted V12 (450 kW) |

| Performances: | Top speed: 149 kn (172 mph, 277 km/h) Cruise speed: 107 kn (123 mph, 198 km/h) Service ceiling: 15,800 ft (4,800 m) |

| Range: | 1,000 nmi (1,000 mi, 1,850 km) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) |

| Endurance: | 8 hours |

| Wing loading: | 19.8 lb/sq ft (97 kg/m2) |

| Power/mass: | 0.10 hp/lb (0.16 kW/kg) |

| Armament – MGs | 1x 0.3 cal M1919 fwd, 1x 0.5 cal. aft M2 |

| Armament – Bombs/Depth Charges | 2x 100 Ibs bombs (45 kgs) or 325 lb (147 kg) DC underwing |

Production & Variants

- XSO3C-1 Prototype, landplane later modified as a floatplane.

- SO3C-1 early Production variant: 141 built.

- SO3C-1K: C-1 modified as target drone (RN Queen Seamew I)

- SO3C-2: Landplane variant, with arrester gear and ventral bomb rack: 200 built.

- SO3C-2C*: Lend-lease variant. Better radio, 24V electrical system (Seamew I): 259 ordered, 59 delivered.

- SO3C-3**: Reduced weight variant. 39 built, 659 cancelled.

- SO3C-4: Proposed variant with arrester hook and catapult capable.

- SO3C-4B: Paper Lend-lease variant of the SO3C-4 (Seamew II).

*More powerful engine, wheeled hydraulic brakes and other improvements.

**Among other modifications its catapult operation ability was removed.

Combat use

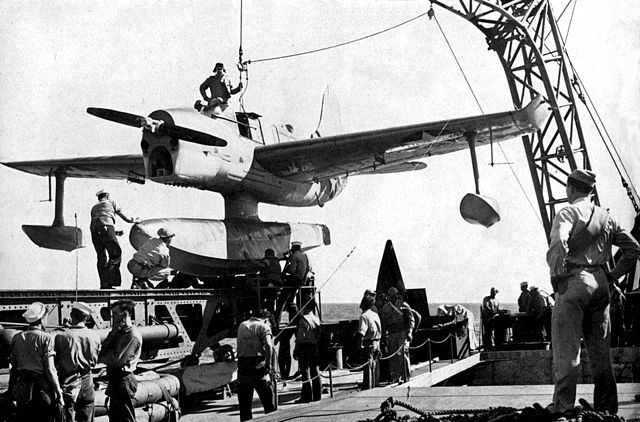

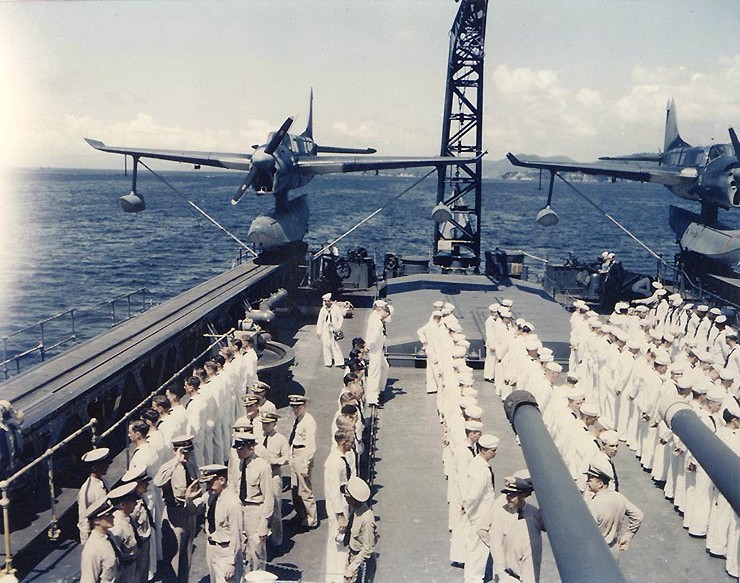

SO3C Seamews on catapults, USS Biloxi 1943

In USN service

It’s the lend-lease British Seamew that led in return an adoption of the name in the USN. Its poor performance in the US Navy had it replaced after introduction, mostly on cruisers, as it was used perhaps for a year before replacement. Many were converted to be as radio-controlled targets (SO3C-1K). After having hope with the SO3C-3 promoted by the company as curing all the previous version’s issues, the US Navy tested the new model for a short time before cancelling the 650+ order outright. In early 1944 all cruisers definitely had replaced the Seamew by the older, but trusted SOC seagull, until then used by training units, and restored to first-line service. When sufficient numbers of Vought Kingfishers were available, they also replaced the SOC Seagull on cruisers (battleships were a priority).

Deliveries started July 1942, on the cruiser USS Cleveland (CL-55) with Scouting Squadron 12 (VCS 12). They saw action for the first time in November 1942 for Operation Torch. At least they provided intel for the troops and in some occasions even strafed and attacks French positions. Next, USS Columbia (CL-56) had two SO3Cs, one being lost when falling off a catapult on 3 January 1943, and replaced with a SOC-1 Seagull. By 12 January the two took off for a practise flight, and the second SO3C was lost and sea but the pilot rescued, a replaced by a SOC-1. A pattern that was reproduced on many cruisers. The SO3C was quickly lambasted in general for its poor performances, but was kept in service fault of somethiong else at least until the older SOCs came up from reserve and training units. The Coast Guard started to received those replaced.

The cruiser USS Montpelier (CL-57) received them by late 1942. One was lost on 1 January 1943 when its two depth charges prematurely detonated with the schock of catapulting, killing the pilot, Ens William T. Thompson. She also carried SOC-1s, but in 1944. USS Denver own two SO3Cs also arrived in late in 1942 and later four, but three were soon lost in accidents. By mid-summer 1943 she only had SOC-3s. USS Biloxi (CL-80), abundantly photographed and filmes with her SO3Cs had them already during her shakedown cruise in October 1943. One crashed in a landing attempt off Trinidad. By early 1944 she had two Vought OS2U-3 Kingfishers. They also served on USS Boston (CA-69)from the training ship USS Absecon (AVP-23) in early 1943 but she only had a single SO3C and two Vought OS2U-3s.

SO3C-1, 10 July 1943

By late 1943 the Seamew was totally unpopular as being unreliable, sluggish and short-ranged, still unstable and difficult to maintain. The cost of training new pilots and human lives, simply, was not worth the maintenance of this model oon USS Cruisers. All get rid of these as quickly as they could, simply waiting an accident. By 1944,, the sight of a float version of this machine was fairly rare, all the remainder has been converted to undercarriage versions for various roles.

In British service as the Seamew Mark I

Curtiss Seamew Mk.1

The SO3C-1s with fixed undercarriage were ordered by the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm under Lend-Lease and in service were called Seamew Mark I. But crews, soon showing its clar limitations nicknamed it the “Sea Cow”.

Female test pilot Eleanor Lettice Curtis in her book “Forgotten Pilots” precised that even though the manufacturer certified the standard fuel tanks can carry 300 gallons, in service the abysmal engine performance meant to take off the pilots only carried 80 gallons, which was setup as the maximum for Air Transport Auxiliary trips. This of course severely curtailed its actual range to a mere fraction of the 1,150 miles promised (or 8h flight).

The crews also soon discovered its tail needed to be raised before becoming airborne, as it needed a safe distance to recover and having sufficient aileron control. An experienced Brituish pilot stated that “it is hard to imagine how, even in wartime, such an aircraft could have been accepted from the factory, let alone given valuable cargo space across the Atlantic.”.

The first batch delivered was planned woth a centreline bomb rack and arrestor gear, but the former was eliminated due to weight issues, or bombs never carried. The Seamew Mk.I, even though a SO3-2C variant, saw 250 allocated by lend-lease, but only 100 actually delivered as the the last batch was refused by the British, which instead ordered more Kingfishers Mark Is. Although it was provided from January 1944, the British declared it obsolete in September and it was gradually removed from service in 1945. None were when WW2 ended. The “Queen Seamew” was proposed bu also refused.

Seamews were in service with the No.744 and No.745 NAS, RCAF Yarmouth in Nova Scotia (Canada), patrolling the martime lanes there, and with No.755 NAS in Hampshire, the sold unit based in UK. No ever reported a victory against any U-Boats although they detected some. They carried in that role two 325 lb (147 kg) depth charges underwing.

The end of a honeymoon

SO3C-1K N°4744 target drone at NAS Santa Ana, 1946

The Seamew promised a lot but totally undelivered, and is one of those WW2 US manufacturing wartime abject failures, to be added to the Brewster F2A Buffalo, the SB2A Buccaneer (same company), or the dive bomber SB2C Helldiver, also from Curtiss (seen by some inferior to the SBC biplane it replaced!). Despite the fact this failured was in large part impputable to the navy itself, like asking fior a new and untested engine and revising specs during prduction to double the fuel tank load, this double disappointment meant Curtiss-Wright (the fusion was done in 1929) had more trouble regaining USN consideration for postwar acquisitions (see later).

After being a long main dear supplier of the USN, Curtiss propulariy plummitted, whereas it nonetheless the far better Curtiss SC Seahawk to replace the Seamew, this time a well-performing seaplane for which the Navy seldome intervened. But it was to be the company’s last production model ever.

From then on, although competing in several programmes, Curtiss-Wright Co failed to attract any orders: The Curtiss XF14C (1944) single engine monoplane fighter, XBTC (1945) torpedo bomber, XF15C (1945) mixed propulsion fighter, XBT2C (1945) torpedo bomber were tested but never adopted. The 1948 XF-87 Blackhawk was even its first jet, a prototype, large four engine fighter for the US Air Force but performance problems were its undoing, and it was cancelled after some 87 were ordered. This was the last Curtiss model to see actual production (two prototypes), followed mostly by paper projects in the 1960-70s.

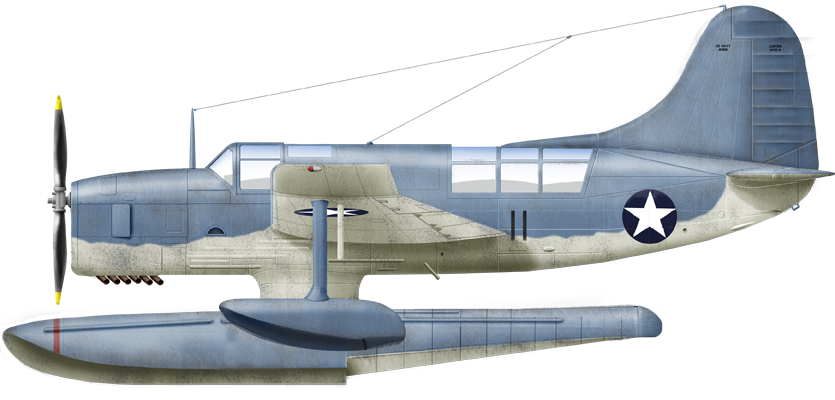

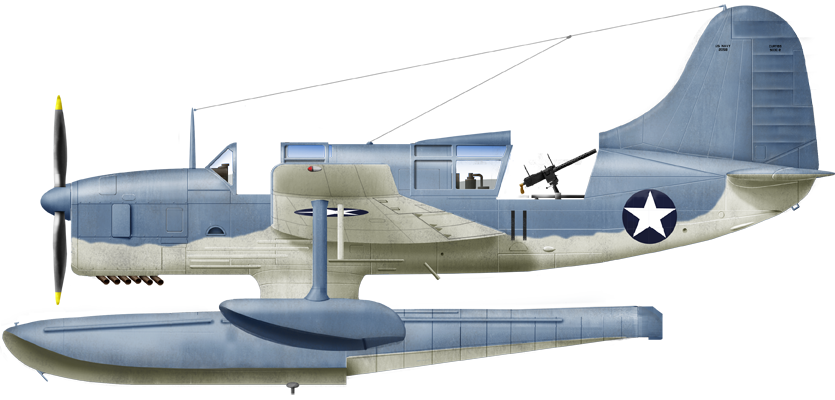

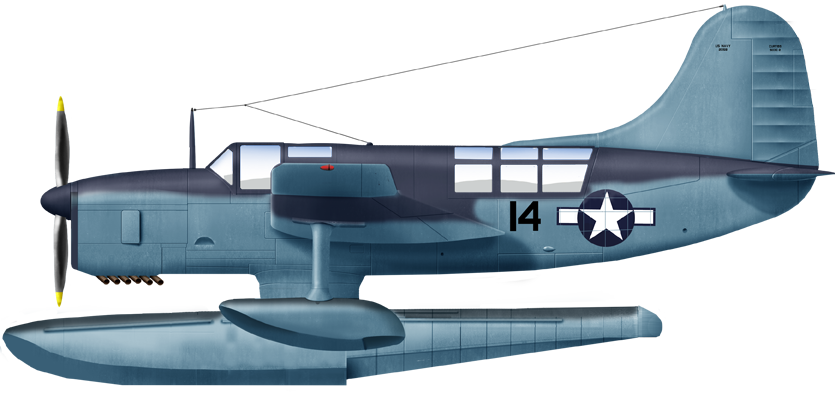

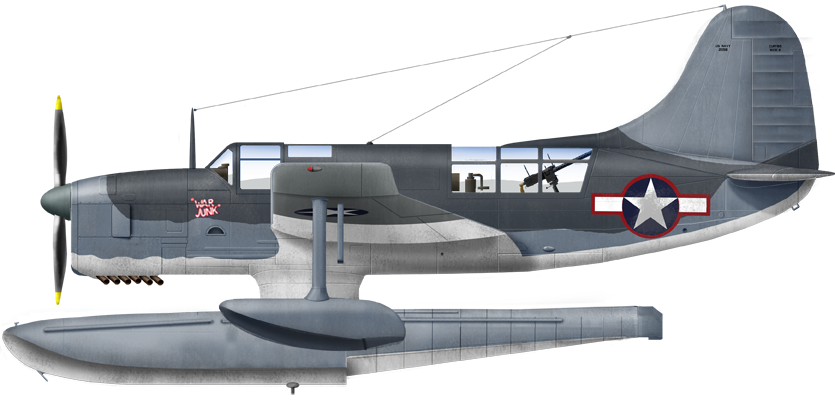

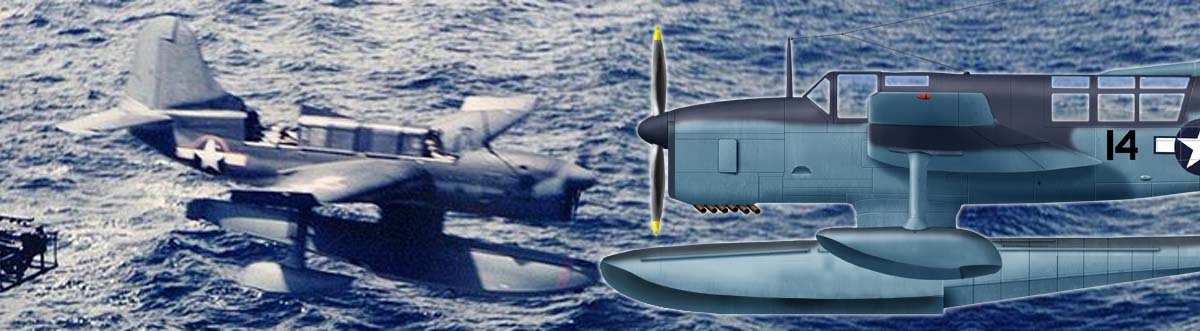

Illustration profiles:

SO3C-1 VCS-12 USS Columbia 1942

SO3C-1 VCS-12 USS Denver 1943

Unidentified SO3C-1, 1943

SO3C-3 VCS-13 USS Biloxi 1943

SO3C-2 SOSU 3th NAS North Island California 1942

Curtiss Sea Mow MK.I, FAA, 1944.

SO3C-1K drone, VJ-11, 1945

Photos

SO3C-2, national archives movie extract

SO3C-1 in flight

SO3C-2 in flight early 1942

SO3C-2 in flight late 1942, straight from the factory. Notice the hastily painted production number.

SO3C-1, 9 September 1942

SO3C-3

Fake montage for the presse of a SO3C over USS Lafayette (former SS Normandie, capsized in NyD) in 1943

Curtiss SO3C-1 in flight c1942

SO3C-1-flight

SO3C_on_catapult_of_USS_Columbia_1943

On USS Biloxi, 1943

So3C-2 on an escort CVE

Src/Read more about the Curtiss SO3C:

Bowers, Peter M. Curtis Aircraft, 1907–1947. Putnam & Co

Curtis, Lettice. The Forgotten Pilots. Nelson & Saunders

Donald, David. The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Orbis Publishing

Donald, David. American Warplanes of World War II. London: Aerospace Publishing

Ginter, Steve. The Reluctant Dragon – The Curtiss SO3C Seagull/Seamew (Naval Fighters No.47)

Green, William. War Planes of the Second World War, Volume Six: Floatplanes.

Larkins, William T. Battleship and Cruiser Aircraft of the United States Navy.

Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to American Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor Press

Swanborough, Gordon and Peter M. Bowers. United States Navy Aircraft since 1911. Putnam & Co

Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft since 1912 London: Putnam & Company Ltd.

On aviastar.org

cgaviationhistory.org

historyofwar.org

militaryfactory.com

aerocorner.com

On airwar.ru

warmachinesdrawn.blogspot.com

Rex hangar channel video about the Seamew

The Models Corner:

1/48 Czech Model, resin

Scalemates query. Lot of choices and scales.

Sword 1/72 on 1999.co.jp

aircraftresourcecenter.com

modelplanes.de

flight-manuals-online.com

hyperscale.com/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign