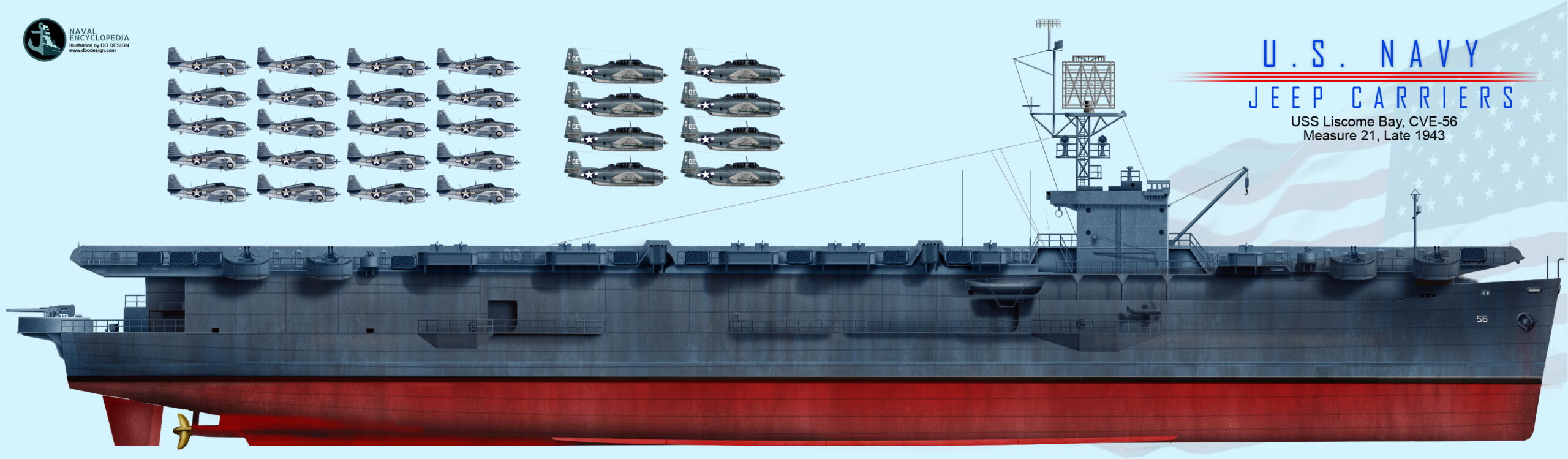

US Navy 50 Escort Aircraft Carriers (1942-44): USS Casablanca, Liscombe Bay, Coral Sea, Corregidor, Mission Bay, Guadalcanal, Manila Bay, Natoma Bay, St. Lo, Tripoli, Wake Island, White Plains, Solomons, Kalinin Bay, Kassan Bay, Fanshaw Bay, Kitkun Bay, Tulagi, Gambier Bay, Nehenta Bay, Hoggatt Bay, Kadashan Bay, Marcus Island, Savo Island, Ommaney Bay, Petrof Bay, Rudyard Bay, Saginaw Bay, Sargent Bay, Shamrock Bay, Shipley Bay, Sitkoh Bay, Steamer Bay, Cape Esperance, Takanis Bay, Thetis Bay, Makassar Strait, Wyndham Bay, Makin Island, Lunga Point, Bismarck Sea, Salamaua, Hollandia, Kwajalein, Admiralty Islands, Bougainville, Matanikau, Attu, Roi, Munda.

US Navy 50 Escort Aircraft Carriers (1942-44): USS Casablanca, Liscombe Bay, Coral Sea, Corregidor, Mission Bay, Guadalcanal, Manila Bay, Natoma Bay, St. Lo, Tripoli, Wake Island, White Plains, Solomons, Kalinin Bay, Kassan Bay, Fanshaw Bay, Kitkun Bay, Tulagi, Gambier Bay, Nehenta Bay, Hoggatt Bay, Kadashan Bay, Marcus Island, Savo Island, Ommaney Bay, Petrof Bay, Rudyard Bay, Saginaw Bay, Sargent Bay, Shamrock Bay, Shipley Bay, Sitkoh Bay, Steamer Bay, Cape Esperance, Takanis Bay, Thetis Bay, Makassar Strait, Wyndham Bay, Makin Island, Lunga Point, Bismarck Sea, Salamaua, Hollandia, Kwajalein, Admiralty Islands, Bougainville, Matanikau, Attu, Roi, Munda.WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classThe world’s largest carrier program

In late 1942, the USN urgently needed more aircraft carriers to face its obligations both in the Atlantic and Pacific. Conversion of existing C3 cargo hulls took time despite their seemingly easy and limited nature, and there was some desperation on how to increase the output.

In the early summer of 1942, Vancouver shipyard’s owner Henry J. Kaiser, already famous for the amazing output to deliver Liberty ships suggested the American government to manage the mass construction of a batch of 100 per year. His mass-construction simplification process and technology of continuous assembly and modular approach was, as he argued, adaptable to warships.

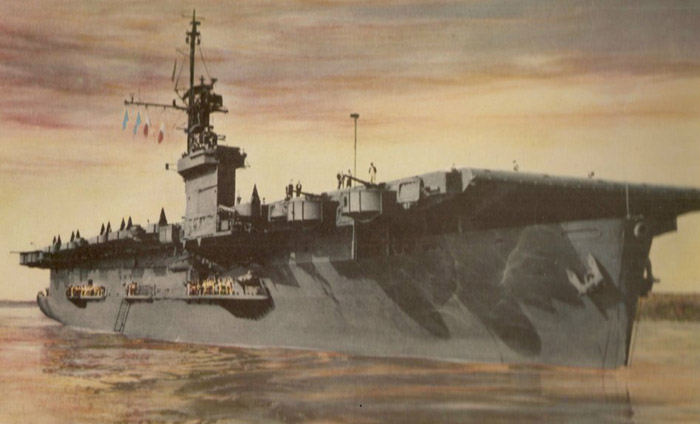

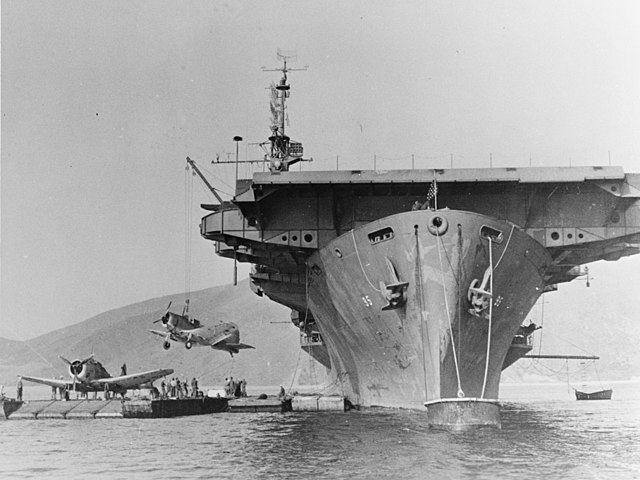

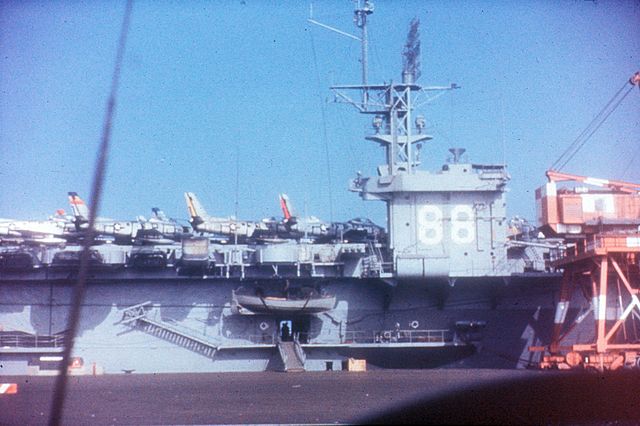

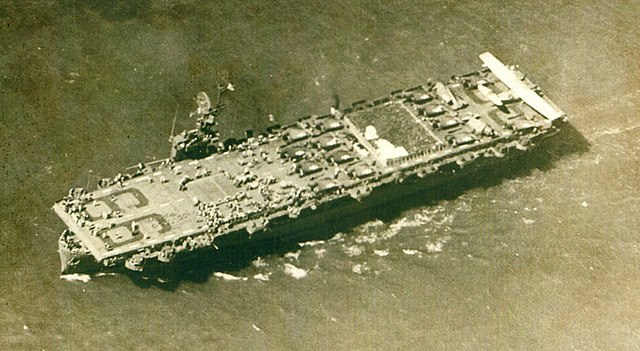

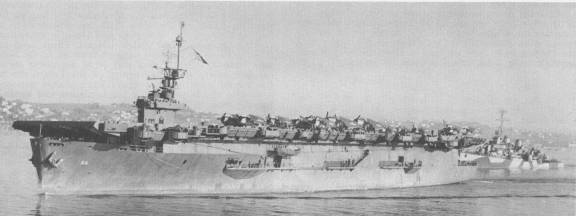

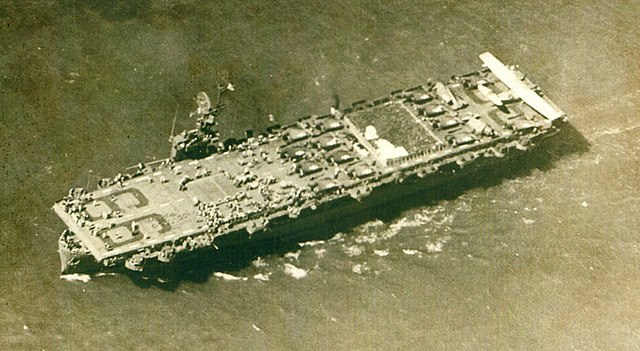

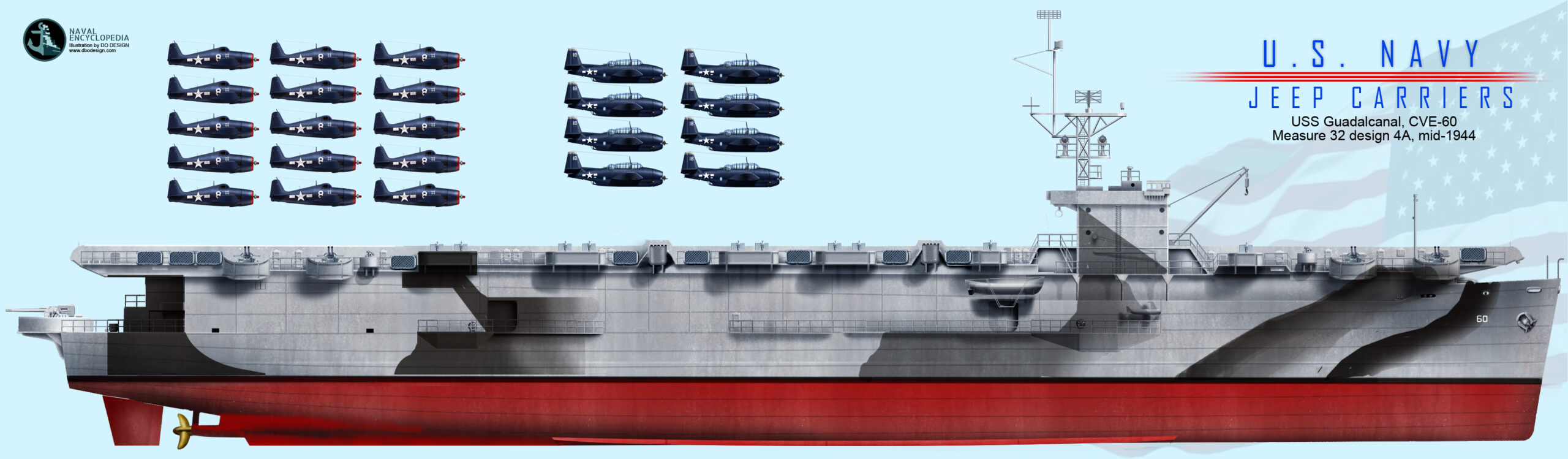

USS Guadalcanal(CVE-60) in 1944

President Roosevelt has become interested in the project, since in mid-1942, fleet carriers in construction were still far from ready and the need was urgent anyway. He confered with the yard’s team, Kaiser eventually being granted an offer to finance the construction of 50 aircraft carriers at once.

The Bogue class having been extensively tested successfully, it was proved that such vessels could provide air cover for the Pacific landing squadrons while continuing to serve in the Atlantic. Rather than scatter other series between several models of converted freighters, Henry J. Kaiser, the wealthiest holder of the largest and most prolific shipbuilding yards in Vancouver, Canada, proposed to the Admiralty to produce 100 escort carriers in record time (less than a year), based on his method of building Liberty Ships.

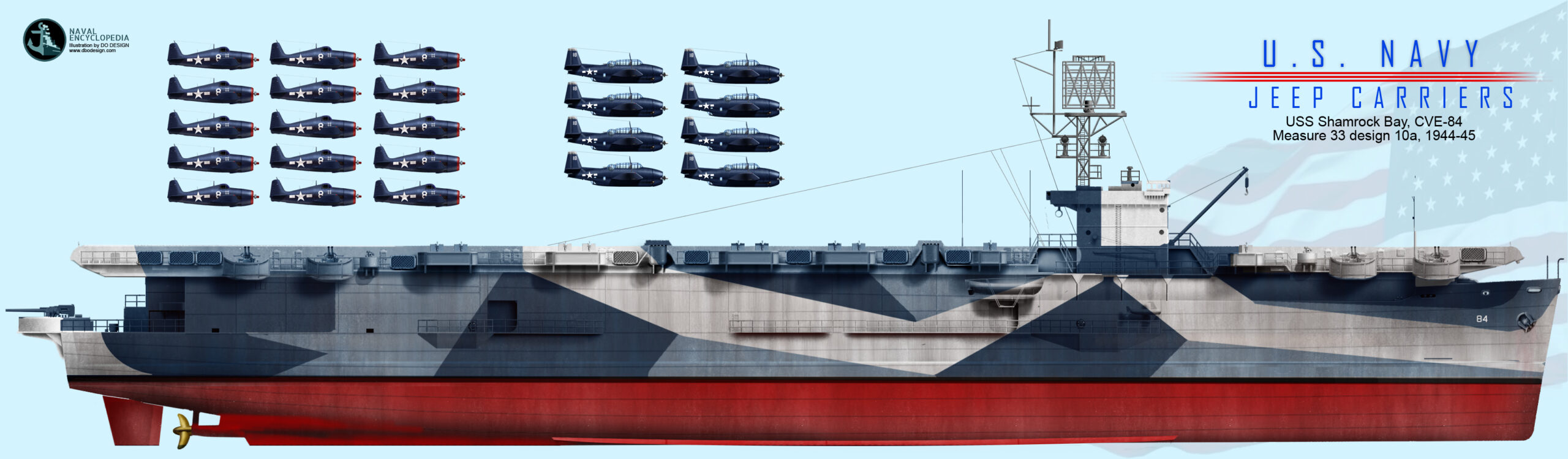

The Casablanca became the most prolific class of aircraft carriers in history. Although narrower and crampier than the Bogue class, their larger holds made it possible for them to carry more planes and fuel. They were also much faster thanks to their turbines, coming from fast cargo ships designed to escape U-Bootes. They were actually built in record time, the first, the USS Casablanca, laid down in November 1942 and into active service by July 1943 whereas the last one, the USS Shamrock Bay, was laid down in November 1943 and active in March 1944 (So in just in 5 months !).

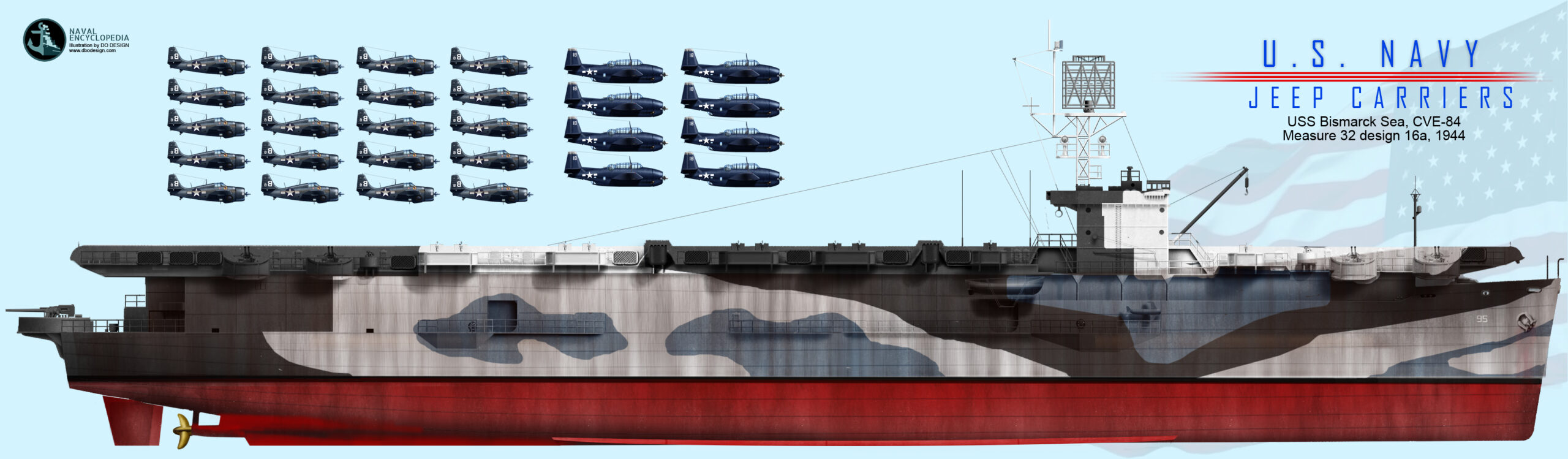

They were ready in time for the great pacific operations, and 5 would be sunk in combat, USS Liscome Bay in November 1943, Gambier Bay and St Lô the same day during the battle of Leyte – victim of the Japanese guns. Kamikazes would also claim the USS Ommaney Bay in January and the USS Bismarck Sea in February 1945. After the war, some served for a time as ASW support and carriers thanks to their onboard helicopters. Most were broken up in 1960. They were a pure product of wartime and never intended to last long.

Genesis of the need, specifications and design

In WWI already, UK experimented in converting light cruisers to airplane carriers, as HMS Cavendish and depite the project was cancelled, it became subject of interest in the earlu interwar, more promising in some ways that the ponderous battleships conversiosn for fleet use. In 1925 already, the USN General Board considered the conversion of cruiser hulls to aircraft carriers. Treaty limitations still allowed for uncommitted construction tonnage to enable more carriers than authorized, using the treaty loophole of less than 10,000 tons ships. The IJN also took that alley, resulting in the Ryujo. About this uncommitted tonnage for small carriers, the board eventually reported:

“Incomplete studies of the subject by the Bureau of Construction and Repair and the meagre information available concerning the performance of airplanes from carriers of approximately 10,000 tons displacement does not justify building them at this time.”

“light” carriers resurfaced by May 1927 when LCdr. Bruce G.Leighton analyzed the problem in “Light Aircraft Carriers, A Study of their Possible Uses in So-Called ‘Cruiser Operations,’ Comparison with Light Cruisers as Fleet Units.” He already distinguished between CVL’s and CVE’s roles, between capital ships attack, fleet support and ASW patrols and reconnaissance. He considered them “worthy substitute for the light cruiser, or even preferable”.

In March 1939, Capt. John S. McCain, Sr. onboard USS Ranger (which experimented precisely the viability of such intermediate-light designs), wrote to the Secretary of the Navy about the ututility of eight “pocket-size” fast carriers (which Ranger was not) in orer to supplement fleet CVs rarther than replacing them.

Rear Admiral Ernest J. King answered his letter about a complete lack of enthusiasme for the idea and a diverisons of resources, suggesting instead that the Range was not the way forward due to her meagre air group and that the USN should pursue the largest air group reachable on the allocated tonnage instead (which was the goal with the Essex class). The Bureau of Construction and Repair however in 1940-41 as the war was on full swing, considered the feasability of converting fast passenger ships with short flight decks. By November 1940, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) confirmed SecNav when reporting the Chairman of the U.S.Maritime Commission that the characteristics of aircraft have changed in sauch a way no converted merchant vessel would be satisfactory as an aircraft carrier.

But some lowered ranks in the navy did not dropped the ball and “short-circuit” the hierarchy by directly calling President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former naval officer, scretary of the navy, and always interested by it, actively enter the controversy. He pointed out that UK was now fighting a merciless war on the Atlantic against U-Boats and as many U.S.-built military aircraft arrived in leand-lease, as well as 50 destroyers, her urged the need for an escorting and aircraft-carrying ship for faster delivery rather than in the usual cargo crates. By mid-February 1941, Rear Admiral William F. Halsey wrote to CiC Adm. King:

“A previously stated expectation, that the Navy would be called upon to provide transport for Army aircraft, has now materialized in the current diversion of Enterprise and Lexington to transport 80 pursuit planes from the West Coast to Hawaii. To continue with primary reliance on aircraft carriers for such work, as is our present neces-sity, seriously endangers the availability of air-offensive power in the Fleet.”

Adm. Husband E. Kimmel endorsed it from his position as Commander, Aircraft Battle Force to the CNO. By October 21, 1940, the CNO received a memorandum from the President’s Naval Aide about testing the conversion of a merchant into an aircraft carrier. But it was bolder than just an aicraft taxi: It was to carry indeed 8 to 12 helicopters of the new Sikorsky type -not yet operational- or airplanes tailored for small decks and hangars. The idea of a quick conversion to spread an air cover ahead of convoys and detect U-Boats, dropping smoke bombs for the escorts to pick up.

The CNO on 30 December 1940 dediced to ask the chairman of the Maritime Commission to investigate this possibility. By 2 January they consulted their lists and found two refugee Danish ships offering such conversion capability. Later investigation however demented that prospect. The conference determined that the intended ships should be of standardized design for plans to be easily ported on mass-construction ships, and that the air group and types question should be further investigated.

They also estimated that defence should included four AA pom-poms and one 5-inches surface gun. But the converted merchant ship idea was definitely “in the tubes”. On January 6, 1941, Adm. Harold R. Stark, the current CNO, wanted a new conference in his Washington office to further discussed the matter. The autogiro type was soon eliminated (The IJN howewever will adopt it nevertheless) and that dropping smoke bombs only was a waste of time (as well as blimps). A better loaded aircraft with depht charges or bombs would be a better ASW proposal overall. The short deck idea was thus also dropped (This would not deter the Royal Navy to convert MACs (Merchant Aircraft Carriers)).

The meeting also concluded that diesel should bu used to eliminate smokestacks. The Maritime Commission was consulted for the conversion of C-3 cargo ships. They in response, answered that the Mormacmail and the Mormacland were suitable for conversion and available. This was reported to President Roosevelt and that a full conversion would last three months and acquisition was sanctioned on March 6, 1941. On June 2 was commissioned USS Long Island (AVG-1), and plans were made to convert the Mormacmail, but the Bureau of Aeronautics wanted a 350 feet deck to land its SOC SeaGulls. Long Island had a 362 feet deck, one elevator, a small hangar and 16 planes.

Mormacland was eventually sent to the RN as HMS Archer when completed by November 1941. Long Island essentually replaced USS Langley as a new test and training ship. It soon underlines the need of a broader deck and two elevators instead of one, as a longer flight, better AA and higher hangar. On December 26, 1941, the Secretary of the Navy approved the conversion of 24 merchant hulls as part of the 1942 shipbuilding program (The Bogue class). In March, her ordered the conversion of cruiser hulls (the ten CVLs or Independence class). However for large series, there were at the time only twenty C-3 hulls available for conversion and ten were already planned for the Royal Navy. Meanwhile USS Charger (CVE-30) tested more ideas andreplaced CVE-1 as training ship with closer caracteristics to the Bogues and subsequent CVEs.

The remaining four CVEs of the 1942 program were converted from Cimarron class fast fleet oilers (T3 class) later the Sangamon class, larger, with a larger flight deck of 503 feet by 85 feet, and enough hangar space to accomodate two small squadrons. They were rushed-completed for Operation Torch.

Meanwhile, the experience of the Atlantic convoy shed some light on possible CVE improvements, notably on carrier operations and tactics to adapt to the new U-Boats tactics, the placement of the catapult and elevators. Service experience with the Sangamon class brough some interresting returns. Reports were written on their daily used of TBF-1 Avengers, SBD-3 Dauntless and F4F-4 Wildcat in support of landing operations while in TF 34. Reports about their commitment in combat air patrol and anti-submarine patrols were noted.

All in all as commented the Atlantic Commander in Chief (CinCLant)

“The CVE’s proved to be a valuable addition to the Fleet. They can handle a potent air group and, while their speed is insufficient, thev can operate under most weather conditions and are very useful ships.”

. This report was not lost to Ernest King and revised his opinions.

This was balanced by Captain Calvin T. Durgin which reported:

“Due to their low speed, lack of protection and light armament, it is considered hazardous to employ a CVE group in operation where there is likely to be an effective enemy opposition.

Such a group can, however, be used to advantage, and is capable of inflicting substantial damage to the enemy in assault where the enemy air and sea opposition is negligible or when it is

being contained by other superior forces. When this situation exists, the CVE is well equipped to provide all support until landing strips are established ashore, and it can be effectively employed for bombardment spotting, combat air patrols over beaches and surface forces, for all forms of air reconnaissance missions and for bombing, rocket and strafing attacks.”

By the time the four Sangamons rejoined the Pacific at the end of 1942, the carried fleet was down to USS Enterprise and the Saratoga.

President Roosevelt before that announced new escort carriers would be built when visited by Shipbuilder Henry J. Kaiser. He impressed the President with his plan for mass production of escort carriers, a plan browing and under supervision by the Maritime Commission since early 1942.

Succession

USS Casablanca (CVE-55), the first of these, was commissioned July 8, 1943, leading a serie from CVE-55 to CVE-104. The order was complete by July 8, 1944, an impressive achievement. But the Sangamon class led to study a larger variant planned for the 1944 building program which became the first Navy-designed escort carriers for which hull and propeller model tests were carried out at the David W. Taylor Model Basin. The design was approved December 10, 1942 and the contract was let on January 23, 1943. The Commencement Bay (CVE-105) class was born. They measured 557 feet for a 19 knots speed, trial displacement of 23,100 tons. Most were commissioned just before V-J Day and incorporating all lessons learned since USS Long Island while the CVE type at large earned the respect of the Fleet by its service.

By December 13, 1944, the Escort Carrier Force, Pacific, was created and fell under command of RAdm. Durgin which evaluated the Sangamon class in North Africa. This was the result of the large number of escort carriers now available to the Fleet, thanks to the Casablanca class. Experience at Palau, Morotai and Leyte all pointed out better planning was necessary not to jeopardize their usefulness and unleash their full potential.

Scot MacDonald, based on reports by VADM. (THEN RADM.) Calvin T. Durgin, Commander, Escort Carrier Force, Pacific for NAVAL AVIATION NEWS, Dec. 1962. Src

About Henry J Kaiser

Henry John Kaiser (May 9, 1882 – August 24, 1967) was an American industrialist, “father of modern American shipbuilding”. He started in the construction industryand notably worked on the Hoover Dam. He formed Kaiser Aluminum and Kaiser Steel and later established the Kaiser Shipyards as a logical follow-up. Of course his most famous creation were the 2700+ Liberty ships of World War II, out-building what German U-Boats can sunk. After the war he turned to Kaiser Motors and the booming post-war automobile industry. He also diversified in the 1960s to other sectors.

Henry John Kaiser (May 9, 1882 – August 24, 1967) was an American industrialist, “father of modern American shipbuilding”. He started in the construction industryand notably worked on the Hoover Dam. He formed Kaiser Aluminum and Kaiser Steel and later established the Kaiser Shipyards as a logical follow-up. Of course his most famous creation were the 2700+ Liberty ships of World War II, out-building what German U-Boats can sunk. After the war he turned to Kaiser Motors and the booming post-war automobile industry. He also diversified in the 1960s to other sectors.

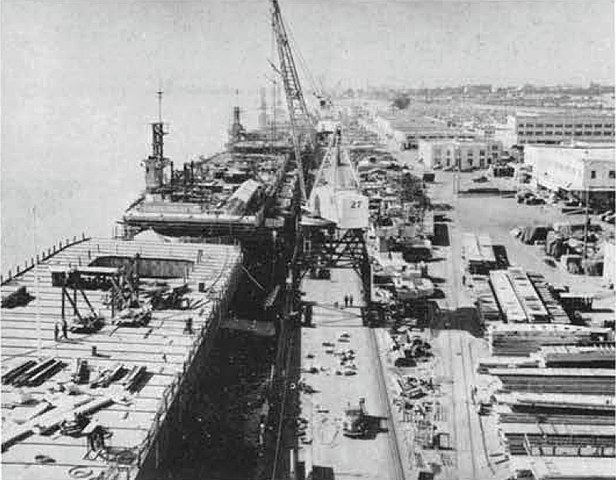

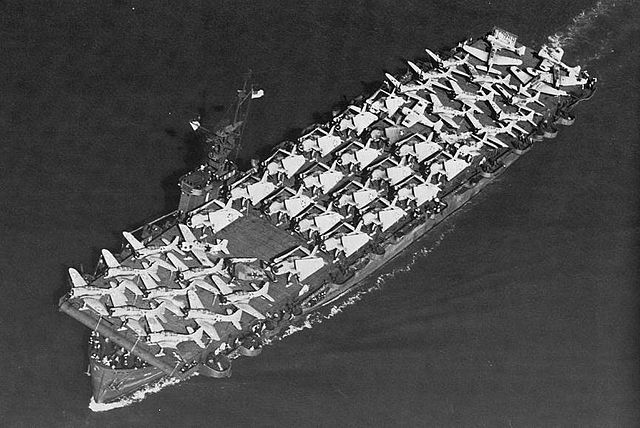

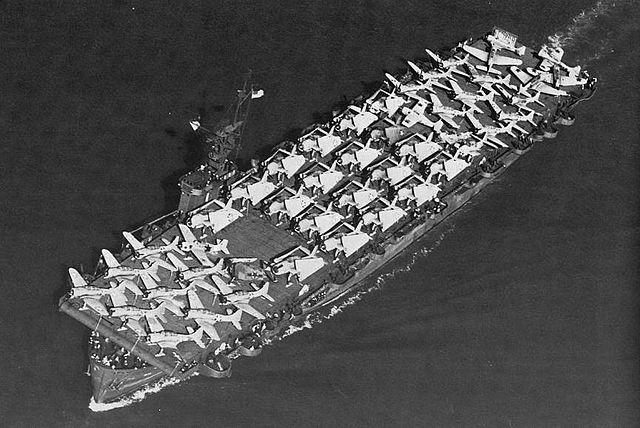

Escort carriers fitting out at Kaiser Shipyards circa April 1944

Of course it’s for his shipyards Henry J Kaiser was best known.

The Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond, California became the fastest and largest ship producer in the world, but it was not done on a single day: Henry J. Kaiser had been building cargo ships for the U.S. Maritime Commission already by the late 1930s. After September 1939, he started to receive additional orders from the British government and knowing his capability would be soon overrun by orders he established his first Richmond shipyard, in December 1940.

This soon accompanied by an innovative medical care (later “Kaiser Permanente”). The four Richmond Kaiser Shipyards built 747 ships in World War II which was an unsurpassed industrial effort for shipbuilding. His ships became the world’s cheapest built in 2/3 less time and at 1/4 cost. Robert E. Peary was became the recold holder of faster ship of that size ever assembled, in less than five days (it was a state-sponsored competition among shipyards). All in all by 1945 the yard built $1.8 billion worth of ships.

He achieved this feat by adapting production techniques specific to cargo ship construction with an emphasis on hyper-standardization and taylorization at any level, with an average construction time of 45 days. The Liberty ships were succeeded by the faster Victory ships. He changed his assembly techniques by visiting Ford, which convinced him to swap to welding instead of riveting. Not only it took less strength (and thus, was a job open to women) and was easier to teach, especially for unskilled laborers. Sub-assembliy and modularity was also key in the process.

The choice of Kaiser/Vancouver yard

The success rate of the first led to the establishement of no less than three others shipyards, in Ryan Point (Vancouver), Columbia River (Washington state) and Swan Island (Portland, Oregon). He built also smaller vessels and one was turned in just 71 hours and 40 minutes at Vancouver yard on November 16, 1942.

Perhaps it’s no mystery that this was Kaiser/Vancouver which was chosen by Kaiser for his proposal to the president of a hundred Kaiser hulls converted as escort carriers, just reusing the techniques he mastered well, with assistance for the Navy for all the proper military fittings and installations. Although this was done in the completion phase.

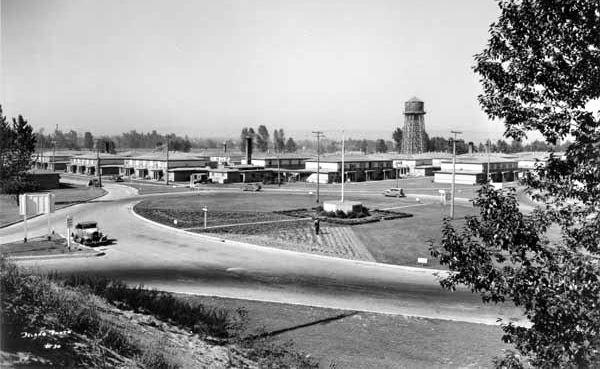

The Vancouver Shipyard was an emergency shipyard, constructed along the Columbia River in Vancouver, Washington (not Canada !) for the U.S. Maritime Commission in 1942. The shipyard was located on the Pacific Northwest as the Oregon and Swan Island ones (both in Oregon). This yard started production in March 1942 over an area of 200 acres (81 ha) and five different types were delivered, but the most famous one by far were the Casablanca-class escort carriers, the yard’s largest “production line”. On Google Maps

Vanport, Oregon, nicknamed “Kaiserville” in 1943. This mushroom city was a feat of wartime public housing setup in Multnomah County.

This yard had a payroll of 38,000 workers which came mostly from Vanport, Oregon were considerable housing was raised to house the workforce in the area. In fact as it often happened in a yard built in such a “remote” location, a city practically emerged from the ground up, fed by additional personal and services dedicated to this workforce. The city was however almost destroyed by the 1948 Columbia River flood.

After the war, the Shipyard had no more orders (as the others in Oregon) and they were sold to Gilmore Steel for just $3.25 million.

At Kaiser Vancouver (now part of Portland subburbia), each new carrier was to be delivered as an “empty box” with a landing deck, catways, fittings for future sponsons, truncated exhausts, a wide and completely empty hangar and lift, and a small island with a lattice, also empty. The completion supervised by the Navy comprised all the electrical lighting and wiring, and basically everything above the main deck, so from the hangar floor.

“Wendy Welder” at Richmond Shipyards. Feats of rapid construction were far less impressive for escort carriers due to the higher level of technicity.

One problem with welded hulls which surfaced after presidential approval for construction, and was more obvious after the war, was the issue of brittle fracture. This caused the loss of some Liberty ships in cold seas: Under both heavy load, bad weather and welding defects, welds failed, and hulls cracked, sometimes in two. Minor changes and more rigid welding control was only implemented from 1947, eliminated Liberty ship losses until 1955.

Kaiser also took part in the Joshua Hendy Iron Works of Sunnyvale in California building the standard EC-2 triple expansion steam engines used on all Liberty ships (the Victories had turbines). This led to the establishement of California Shipbuilding Corporation.

Anyway, welding did not affected the escort carrier life as apparently no significant accident was ever recorded and the losses by gunfire (St Lô) or Kamikaze attacks (xxx) were due to regular battle damage and fire rather than any structural issue. None broke in two as the result of severe impacts.

Construction Challenges

Term of building of the first 10 ships was 241-287 days, last ships of the class were built in 101-112 days or three months and a half on average. This was less stellar than Liberty Ships, but for warship construction of that scale and role, totally unheard of (and never surpassed). For comparison, a Yorktown class carrier took four years, an Essex-class two and a half. The same pre-fabrication and sub-assembly lines were used in a “leaf-pattern” to feed the central assembly line where the hull was assembled. This part was the fastest, and close to Liberty ships’s average delivery rates. It was the completion part which took most time.

As indicated above, the “empty box” delivered to the Navy needed to received many additional systems. Sensitive aviation fuel lines needed to be properly installed and checked, as well as the holds containing ammunitions (from bullets to depht-charges bombs and rockets), the intercom tested as well as communications lines to the AA gunners, machinery and central operation, and all the electronic equipments around the radars, displays, etc. They needed to be carefully calibrated. Crews were far larger than on Liberty ships (62 on average, counting the gunners and navy personal) versus on escort carriers: 910–916 officers and men total, including 50–56 for the air group, pilots and maintenance crews alike. This was more than ten times and implied far more accomodations, food and amenities to setup.

Vancouver Shipyards production setup

The hull chosen was the S4-S2-BB3 type according to the Maritime Commission Board registry. This was not even a wartime, but a prewar (for the US) project and registration. The U.S. Maritime Commission type S4-S2-BB3 emerged in 1941 as the Atlantic Convoys developed as the will to participated to the British desperate chase for aircraft carrier superiority. Planners estimated that military air cover was a crucial component of convoy escort and devise a type of small escort carrier based on the more civilian C4 type. The latter were 4th in rank and largest generic cargo type (hence the “C”).

The C4 were inspired by a designed originally for the American-Hawaiian Lines in 1941, and by late 1941, plans were taken over by the US Maritime Commission which designed a dedicated cargo/troopships in 3 shipyards: Kaiser Richmond, CA Yard No.3 Kaiser Vancouver, WA and Sun SB & DD in Chester PA. These were the largest cargo ships ever designed by MARCOM, with a single screw steam turbine and 9,900 shp, capable of 17 knots. The S4 was equipped ironically with a VTE which seems a step back, but sturdy enough to procured a top speed two knots above, at 19 kts.

Internally by the Commission the S4 were also described as “Kaiser-built Escort Carriers, Special Attack ships, Operation Crossroads”.

According to Kaiser-Vancouver logs here is the detail:

Legend: Hull# | Original Name | Type | MC# | Delivery Date | Pennant and final name:

301 | HMS Ameer | S4-S2-BB3 | 1092 | Jul-43 | CVE 55, renamed Alazon Bay, later Casablanca, scrapped 1947

302 | Liscombe Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1093 | Aug-43 | CVE 56, torpedoed and lost in the Pacific 1943

303 | Alikula Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1094 | Aug-43 | CVE 57, renamed Coral Sea, then Anzio, scrapped 1960

304 | HMS Atheling | S4-S2-BB3 | 1095 | Aug-43 | CVE 58, renamed Anguilla Bay, later Corregidor, scrapped 1960

305 | HMS Atheling | S4-S2-BB3 | 1096 | Sep-43 | CVE 59, renamed Mission Bay, scrapped 1960

306 | Astrolabe Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1097 | Sep-43 | CVE 60, renamed Guadalcanal, scrapped 1960

307 | Bucareli Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1098 | Oct-43 | CVE 61, renamed Manila Bay, scrapped 1960

308 | HMS Begum | S4-S2-BB3 | 1099 | Oct-43 | CVE 62, renamed Natoma Bay, scrapped 1960

309 | Chapin Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1100 | Oct-43 | CVE 63, renamed Midway, later St. Lo, kamikazied and lost at Leyte Gulf 1944

310 | Didrickson Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1101 | Oct-43 | CVE 64, renamed Tripoli, scrapped 1960

311 | Dolomi Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1102 | Nov-43 | CVE 65, renamed Wake Island, kamikazied off Okinawa 1945, scrapped 1947

312 | Elbour Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1103 | Nov-43 | CVE 66, renamed White Plains, scrapped 1959

313 | HMS Emperor | S4-S2-BB3 | 1104 | Nov-43 | CVE 67, renamed Nassuk Bay, later Solomons, scrapped 1947

314 | Kalinin Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1105 | Nov-43 | CVE 68, damaged at Leyte Gulf 1944, scrapped 1947

315 | Kassan Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1106 | Dec-43 | CVE 69, scrapped 1960

316 | Fanshaw Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1107 | Dec-43 | CVE 70, damaged at Leyte Gulf 1944, scrapped 1959

317 | Kitkun Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1108 | Dec-43 | CVE 71, damaged off Mindoro 1945, scrapped 1947

318 | Fortaleza Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1109 | Dec-43 | CVE 72, renamed Tulagi, scrapped 1947

319 | Gambier Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1110 | Dec-43 | CVE 73, sunk by gunfire at Leyte Gulf 1944

320 | HMS Kedive | S4-S2-BB3 | 1111 | Jan-44 | CVE 74, renamed Nehetna Bay, scrapped 1960

321 | Hoggatt Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1112 | Jan-44 | CVE 75, scrapped 1960

322 | Kadashan Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1113 | Jan-44 | CVE 76, scrapped 1960

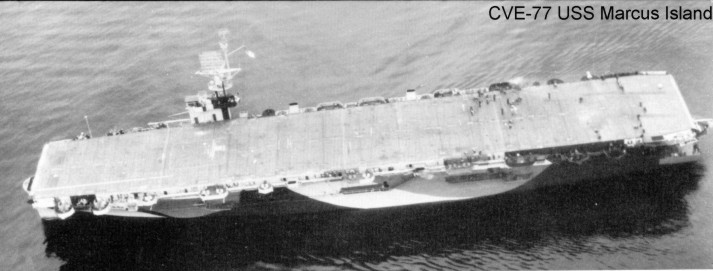

323 | Kanalku Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1114 | Jan-44 | CVE 77, renamed Marcus Island, scrapped 1960

324 | Kaita Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1115 | Feb-44 | CVE 78, renamed Savo Island, scrapped 1960

325 | Ommaney Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1116 | Feb-44 | CVE 79, kamikazied and scuttled off Mindoro 1945

326 | Petrof Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1117 | Feb-44 | CVE 80, scrapped 1959

327 | Rudyard Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1118 | Feb-44 | CVE 81, scrapped 1960

328 | Saginaw Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1119 | Mar-44 | CVE 82, scrapped 1960

329 | Sargent Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1120 | Mar-44 | CVE 83, scrapped 1959

330 | Shamrock Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1121 | Mar-44 | CVE 84, scrapped 1959

331 | Shipley Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1122 | Mar-44 | CVE 85, scrapped 1961

332 | Sitkoh Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1123 | Mar-44 | CVE 86, scrapped 1961

333 | Steamer Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1124 | Apr-44 | CVE 87, scrapped 1959

334 | Tananek Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1125 | Apr-44 | CVE 88, renamed Cape Esperance, scrapped 1961

335 | Takanis Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1126 | Apr-44 | CVE 89, scrapped 1960

336 | Thets Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1127 | Apr-44 | CVE 90, later LPH 6, scrapped 1967

337 | Ulitaka Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1128 | Apr-44 | CVE 91, renamed Makassar Strait, to be sunk as target 1959 but grounded and broke up

338 | Wyndham Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1129 | May-44 | CVE 92, scrapped 1961

339 | Woodcliff Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1130 | May-44 | CVE 93, renamed Makin Island, scrapped 1947

340 | Alazon Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1131 | May-44 | CVE 94, renamed Lunga Point, scrapped 1960

341 | Alikula Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1132 | May-44 | CVE 95, renamed Bismarck Sea, kamikazied and lost off Iwo Jima 1945

342 | Anguilla Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1133 | May-44 | CVE 96, renamed Salamaua, damaged in Lingayen Gulf 1945, scrapped 1947

343 | Astrolabe Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1134 | Jun-44 | CVE 97, renamed Hollandia, scrapped 1960

344 | Bucareli Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1135 | Jun-44 | CVE 98, renamed Kwajalein, scrapped 1960

345 | Chapin Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1136 | Jun-44 | CVE 99, renamed Admiralty Islands, scrapped 1947

346 | Didrockson Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1137 | Jun-44 | CVE 100, renamed Bougainville, scrapped 1960

347 | Dolomi Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1138 | Jun-44 | CVE 101, renamed Matanikau, scrapped 1960

348 | Elbour Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1139 | Jun-44 | CVE 102, renamed Attu, sold for scrap 1947 but resold as Gay, scrapped 1949

349 | Alava Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1140 | Jul-44 | CVE 103, renamed Roi, , scrapped 1947

350 | Tonowek Bay | S4-S2-BB3 | 1141 | Jul-44 | CVE 104, renamed Munda, scrapped 1960

Impact of the Casablanca class on the war

It cannot be overstated as much WW2 involved an industrial colossal effort, several times greater than WWI, the first large scale industrial global war, and unlike any conflict of the past. At least the cold war only asked an incremental, peacetime evolution were output was gradually overshadowed by quality. In WW2, this was a Darwinian prospect. By December 1941, the “free world” seemed defeated on all fronts. Tanks and planes were produced by tens of thousands to be thrown into the furnace, but also ships – not small boats, but very large ones, demultiplying air power, seemingly the great winner of WW2.

Fifty aicraft carriers was an unprecedented number for that kind of vessel, never surpassed so far. It can be argued that they were so fast-buult, so simplified and low-cost they became “consumable” carriers a bit like the Liberty ships from the same yards, built with the same techniques, and as promised, a batch of 50 joined the 143 aircraft carriers built in the United States during the war. Perhaps the closest and only comparable endeavour today are the US Burke class destroyers, by cost and complexity several fold above the capabilities of the nimbler carriers.

By bolstering air power at low coast and quickly, these “Jeep carriers” spared the already hard-pressed Essex-class and Independence class making the bulk of the offensive fast carrier force of the Vth fleet in 1943-45. They provided indeed air cover for the numerous amphibious fleets deployed in the island-hopping campaign of the pacific, but also supply fleets, vital to keep TF38/58 operational on the long run, and the long supply chain which needed escort since Pearl Harbor to the far outreach of the Pacific, down to the US shores.

These 50 escort carriers were also split and part (a small one however) also took part in the vital role of escorting convoys in the Atlantic, since ASW warfare’s best answered soon appeared to be aviation, not least because U-Boats were more easily spotted from the air (and strafe them), but also to shoot down the Luftwaffe’s long range spotting planes such as the Fw200 Condor. The fifty carriers played this unglamorous but vital part of operations until construction stopped in July 1944. After the war, there fortune were diverse, many were stricken outright, other as late as 1960-64, still used as specialized ships (like aviaton transport), and then joined the civilian market, converted as freighters.

Design of the Casablanca class

General construction

Casablanca in many respects reminded Bogue but had smaller displacement, two shafts and was faster. As a design basis the fast dry cargo carrier of S4-S2ВВ-3 type was used, but, unlike the predecessors, new carriers were built quite new, instead of earlier carriers converted from merchant hulls.

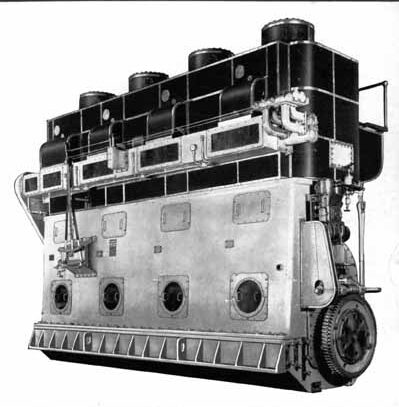

Powerplant

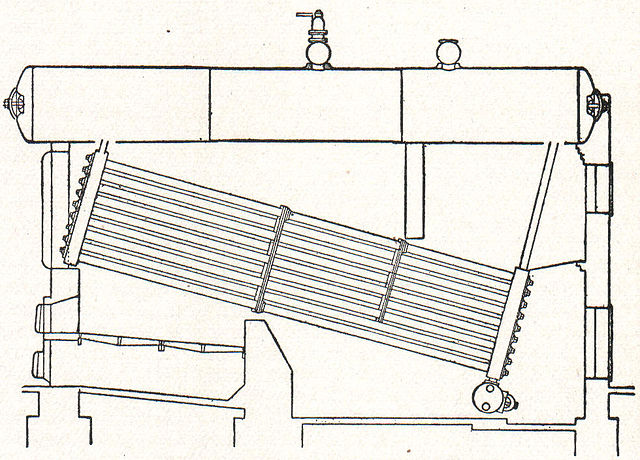

There were two propellers screws, on shafts driven by two Skinner Unaflow reciprocating, vertical quadruple expansion (9000 shp) steam engines. The final commercial evolution of the uniflow engine in the US was reached by the late 1930, up the early 1940s by the Skinner Engine Company from the Compound Unaflow Marine Steam Engine operating in a steeple compound configuration making it almost as efficient as a diesel. This was usual on car ferries on the Great Lakes and the Casablanca-class used two 5-cylinder Skinner Unaflow engines, but not steeple compounds.

They were fed by four Babcock & Wilcox boilers. These were the common marine type, with a main balloon and series of small tubes below for expansion, double-ended.

Total output was 9,000 shp (6,700 kW). This allowed a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). There was a provision onboard of 2,228 tons fuel oil (in addition of the 120,000 gallons/454,000 liters aviation gasoline) for a Range of 10,240 nmi (18,960 km; 11,780 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph).

The exhaust pipes were not truncated but rather ducted to the sides, two each side amidship and far apart to better vent smoke above the deck, at an ideal height for dispersion, as the wind blew stronger just over the deck surface, propelling the fumes outwards of the ship.

Armament

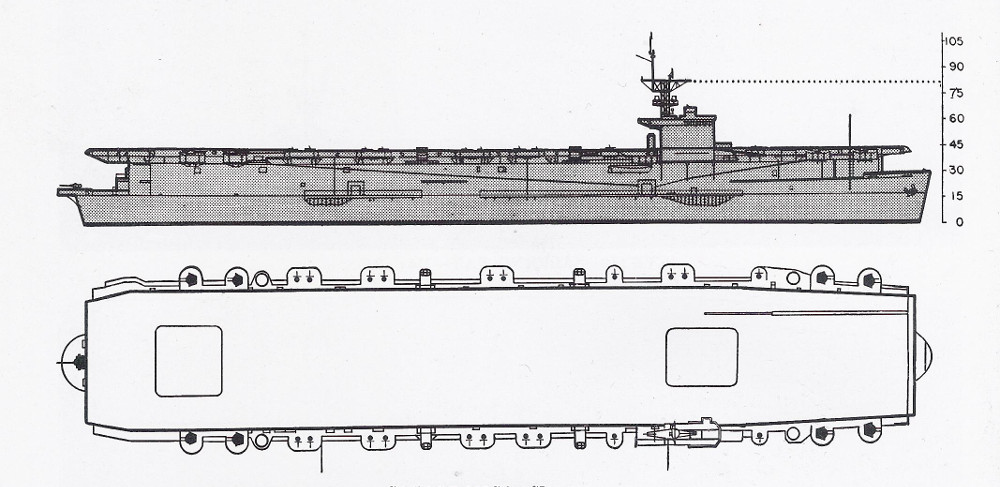

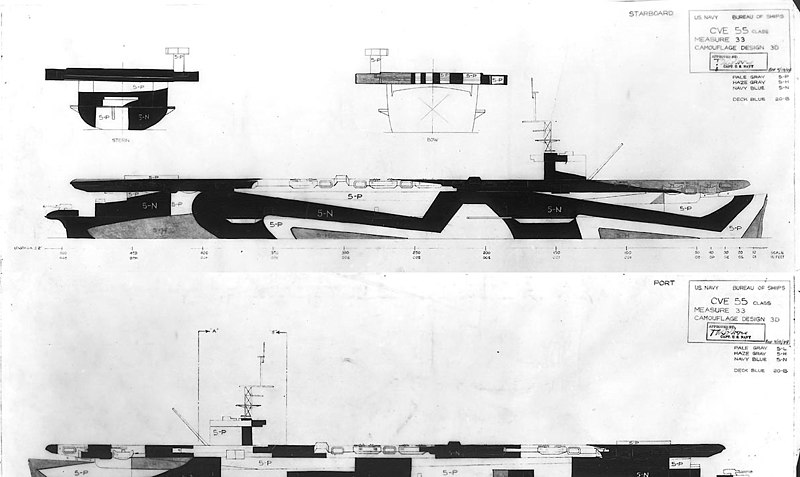

ONI Rendition of the ship – schematics.

It relied on the same usual “troika” of USN vessels of that era, with a single stern 5 in (127 mm)/38 cal dual-purpose gun, two quad 40 mm (1.57 in) Bofors anti-aircraft guns, and twelve 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannons around the flight deck’s sponsons.

Main: stern single 5-in/38

5-in/38 in action on USS Hollandia, 1945

This standard piece of ordnance shared by the whole US Navy and seen much as the best of its kind (a true dual purpose). The only issue of the Casablanca design was it’s location, a headache for engineers. It was placed on the poop deck and only could cover the rear 180° arc, with the landing deck partly above. The second issue was the lack of a protective shield against strafing or shrapnel in a naval engagement. More

40 mm Mounts

The twin mounts -there was no room for quad ones- were located fore and aft of the flight deck. These twin mounts were just in practice halved quad mounts. All parts were interchangeable. They had hydraulic-coupled drives to avoid salt contamination. These Mark IV twin mountings were derived from the Dutch Hazemeyer triaxial mounting from the minelayer Willem van der Zaan which took refuge in Britain in 1940. It was a self-contained mounting with its own rangefinder, radar and analog computer. There were two Mark IV water-cooled guns using track/pinion for elevation and training and a Ward-Leonard system for auto-tracking. It was somewhat delicate to use on small ships exposed to water spray, so more comfortable at the height of the carrier’s flight decks. It seems that crews preferred to use the manual mode over the power mode. It could elevate 25 degrees per second at 90°. The rest of the specs were the same as the common 40 mm/56 Mark 2.

More

20 mm Mounts

Standard L70 Oerikon piece, single mount, shielded, and placed along the deck’s side galley. This changed overtime, but the usual plan was two single sponsons forward of the bridge (one each side), behind the twin Bofors covering the angles, and two others behind or abadft the island, then twin mount sponsons all along the deck aft. The usual figure was four of these either side, so eight for sixteen single mount, and four single sponson mounts. This was increased during the war, making more room for extra single or twin sponsons. There were also four directoros for the AA artillery located on either end of the ship, close to the Bofors mounts. More.

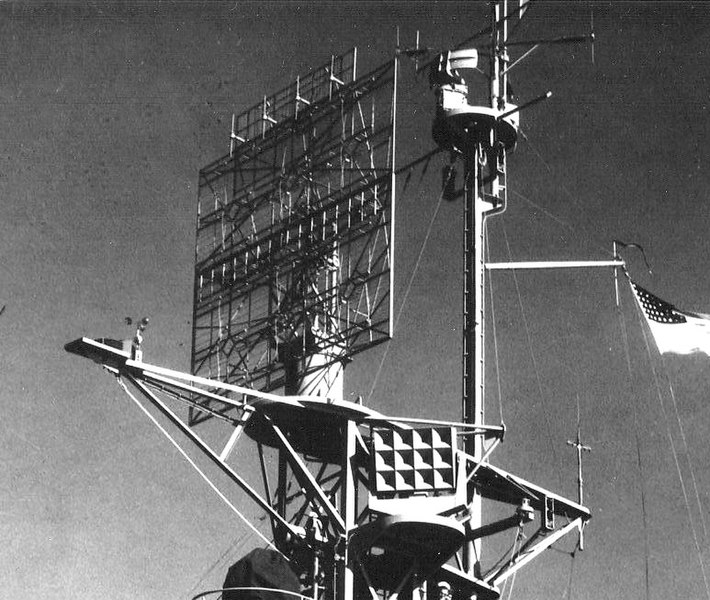

SC and SG Radars and other electronic equipments

The SC air search radar was standard on most small to medium ships of the USN. It was completed by an SG surface search radar.

The 100 Kw SC CXAM-type radar had a Pulse Width of 5 microsecond, 60 Hz frequency, 5rp scan rate and detection of a bomber 30 nm (60 km) away, of a battleship at 10 nautical miles (20 km), a destroyer at 3 nautical miles (6 km), which was the bare minimum, greatly improved with the SC-1.

The SG was also 1st-gen model, small cut parabola at the front of the lower platform of the derrick. It was a 50 Kw model with the pulse Repetition Frequency of 775, 800 or 825 Hz, 4/8/12 rpm frequency, and 15 nautical miles (30 km) aerial range 22/15 nautical miles (30 km) for a surface ship from a battleship to a destroyer.

Both were located on the derrick mast over the bridge.

Some units had their radar upgraded to SC-2 or SK (respectively) later in the war (1945).

Aircraft facilities

They were fitted with two inboard elevators and a single steam catapult installed at the forward end of the flight dekc, to the right (port) unlike the Essex class which had it to the right, but in conformity to earlier designs. There was a single hangar with safety sprinklers and a damage control CP. Like other designs of the time, the avgas tanks were buried deep into the hull. The elevators had not the same size, the aft one was larger to accomodate planes without wings folded. Both rectalngular with rounded edges, the forwards one was in the axis, turned the aft one across. In total they carried 27 planes less spares, although the limited hangar space could not allow much to be suspended under the roof.

Air group

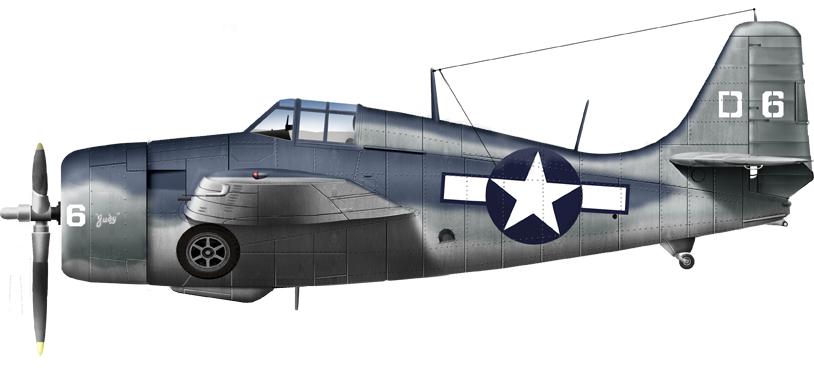

East Aircraft FM-2, VC-2, USS White Plains 1944

Globally, this air group was more diverse was usually assumed. It was composed of the F4F GM Wildcat as main fighter, but in some cases the F4U Corsair was operated as the F6F Hellcat. The SBD Dauntless dive bomber (SBD-5) was more common as the TBF Avenger. For reconnaissance some had one or two Curtiss SOC Seagull, F4F-P Wildcat but more rarely the F4U-P Corsair and F6F-P Hellcat.

The air group varied in time and role: For thos kept for convoy escort in 1943, notably in the Atlantic, the ypical air group comprised nine F4F-8/FM-2 and ten up to 12 TBF-1/TBM-3 Avenger.

By August 1944, USS Kasaan Bay had aboard 24 F6F-5 and 7 F6F-3N, so a very specialized batch of Hellcats, including a heavy reconnaissance component. This was 31, presumably many were a “permament park” on deck.

By April 1945 USS Fanshaw Bay typically had the “standard” air group comprising twenty-four F4F-8/FM-2 for air defence and six TBM-3 for any surface/ASW threat, showing air defence was paramount, notably to protect the assault fleet against Kamikaze attacks.

USS Savo Island at the same time however had twenty F4F-8/FM-2 and 11 TBM-1C plus four TBM-3, mostly used for attacks, notably over Japan. The latter were gradually equipped with rockets, but consumed bombs as standard.

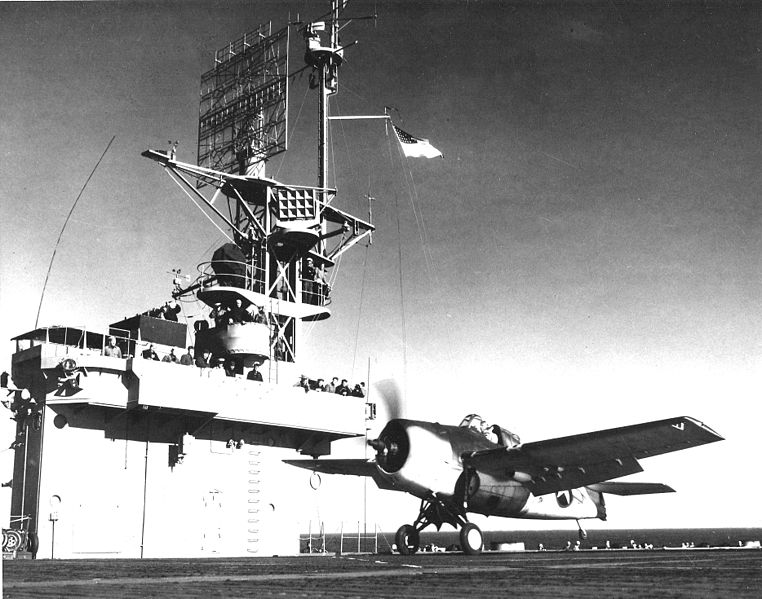

Fighters: General Motors FM-1/2 Wildcat

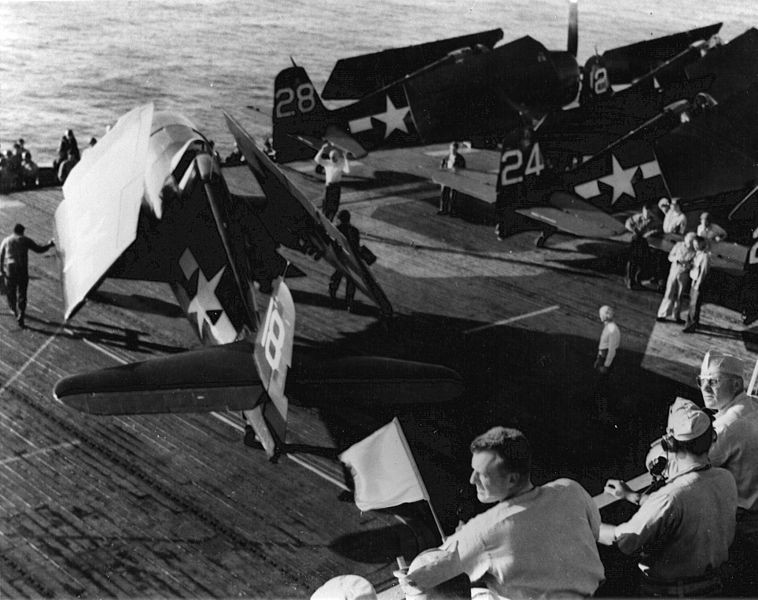

FM-1 Wildcat takes off from USS Kassan Bay in 1944

FM-2 VC-10 onboard USS Gambier Bay October 1944: She was sunk at the battle of Samar

Eastern Aircraft FM-2, “judy” VC-14 USS Hogatt Bay (CV-75), Emirau Island (Bismarck Archipelago), May 1944.

Fighters: Grumman F6F Wildcat

F6F-5 taking off from USS Kasaan Bay off France, June 1944. The F6F was far less common aboard due to her larger size, and only adopted notably in some cases and missions, like landing cover, owing a possible appearance or enemy planes. Since it was far more rare for CVs escorting convoys, the nimbler Wildcat was the norm.

Same as above, F6F from VF-74 from VCE-69, France 1944

Fighters: Vought F8U Corsair

F4U-4 Corsairs of VB-3, USS Solomons, making their qualifications in july 1945

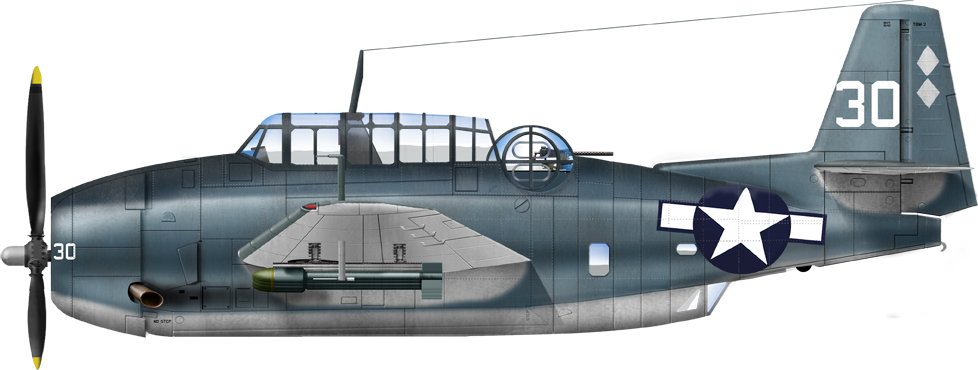

Torpedo-Bombers: Grumman/GM TBM Avenger

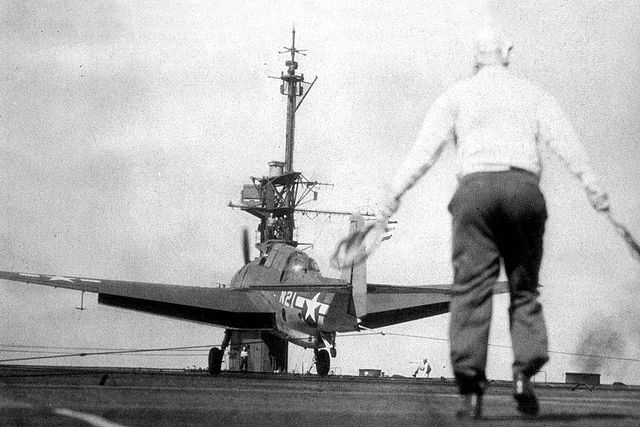

Grumman TBF landing on USS Marcus Island, 5 March 1944. This was a first. This “juggernaut” became common as standard torpedo bomber, but in around 1/3 of the entire air group, completed by Wildcats most of the time. It was preferred over the Helldiver, but its large weight meant for taking off, it needed the whole deck lenght, and landing was always a more perilous exercize compared to roomy fleet carriers.

Douglas SBDs and Grumman TBFs on an escort carrier in 1943

TBM flies above USS Saginaw Bay, 14 June 1944

Dive-Bombers: Curtiss SB2C Helldiver

An SB2C on USS Kwajalein during a Typhoon in late 1944. The Helldiver was not liked much and if part in some occasions of CVE’s air groups, it was reserved for special operations and in particular in amphibious landing cover, both to deal with any ground objectives, but also with an always possible enemy fleet attack, as shown during the battle of Samar (Taffy 3 defence).

Unfortunately i can’t find a profile of one.

Reconnaissance: Curtiss SOC Seagull

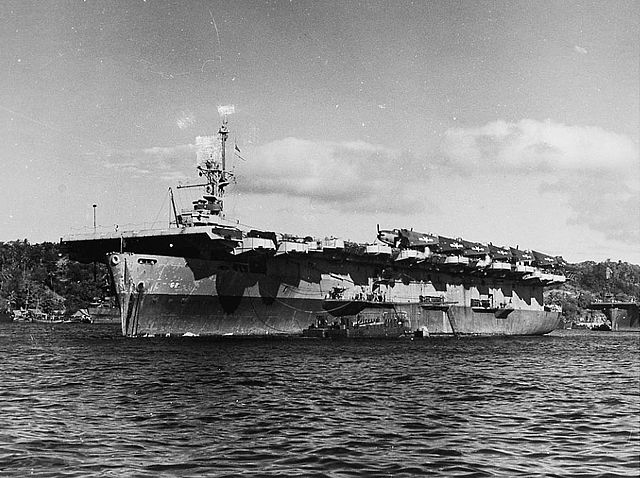

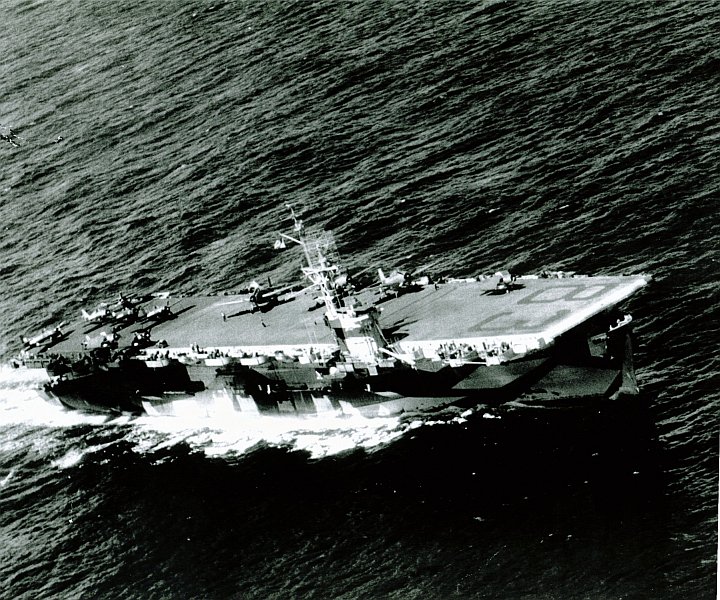

The U.S. Navy escort carrier USS Savo Island (CVE-78) underway in May 1944, location unknown. Note dismantled SO3C Seamew, a J2F Duck (minus its engine), and SOC Seagull and three F6F Hellcats lining the port side, with spare floats lashed down aft.

Tactics and combat actions

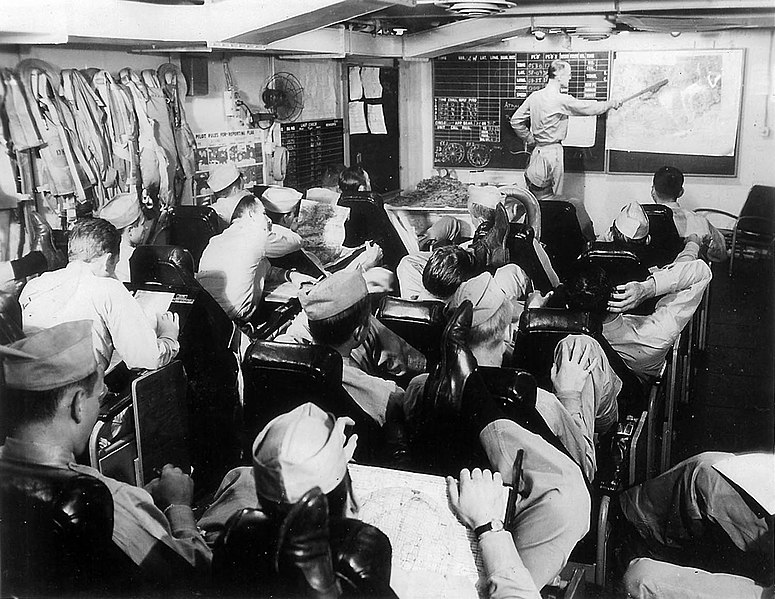

Pilot Briefing aboard USS Kasaan Bay in 1944.

When the first of these ships were commissioned in the summer of 1943, the face of the war in the Pacific already had drastically changed, as the USN was no longer “hanging by the nails” with a few interwar careers and cruisers to stand up to the IJN. The first two Essex class fleet carriers just arrived and relieved this fatigued force centered around the battered USS Enterprise and Saratoga, as well as the first seven CVLs (Independence class) that brought a breath of fresh air to the US Forces, enabling to consider a steady counter-offensive.

A hard to fit new type

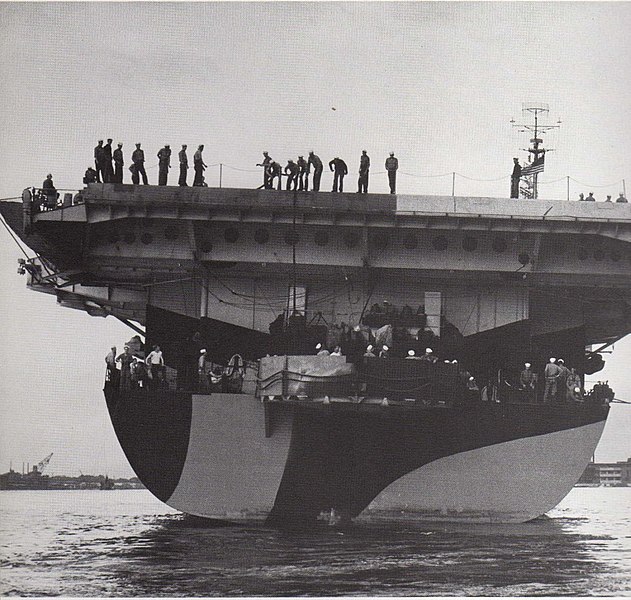

USS Casablanca (ACV-55) about to be launched on 5 April 1943

Tactically, discussion in the admiralty board, submitted with this unexpected mass-built design, had little doubts about its use. Too slow to take part in main combat operation with the fleet (That was the role attributed to the core of TF38/58) they were relegated to two other forces: The assault fleet, mostly comprising troopships and their escort, and the slower auxiliary fleet, supply and depot vessels, repair ships and oilers. Both were to be protected by the fast carrier fleet, taking a more active role allowed by its speed.

The bulk of the assault and auxiliary fleet was made of civilian-grade ships capable of 15 knots on average. Thus the 19 knots of the Casablanca were perfectly adequate. The seocnd point was about their air group. It was not large enough for the air naval doctrine at the time. The “100-planes assault” or “sunday punch” was the new norm for fleet carriers, enabling a better coordination. The CVLs were mostly there to provide a CAP and resupplying losses. But the small groups of the CVEs limited them to air defence, which was shown in the majority of their composition, which was mission-dependent. They usually had a full fighter squadron, but a half-squadron for attack.

For those potentially deployed in the Atlantic, a perhaps more balanced air group as envisioned, with the TBF Avenger used as main ASW patrol/strike plane. The Luftwaffe was not really a threat by late 1943 over this theater. But for the sake of standardization the Casablancas were kept for the Pacific, which was not the case for the Bogue class.

USS Guadalcanal in the Battle of the Atlantic: Its TBMs about to be launched for an attack on U-544. The combination 5-in rockets/depth charges was found the best in early 1944.

Thus, a distinction was made for those assigned to assault forces: Their air group in proportion comprised a more balanced ratio of attack planes versus fighters in order to participate to the air support during the assault. Something that partly freed the fast carrier force for more important objectives, preventing reinforcements and distant strike assets (like airfields on other islands) for example or diversionary actions. In short the CVEs provided the “close air support” for the invasion force, both a permament CAP in case of Japanese aircraft from other airfields/bases not neutralized by the fast carrier force (which happened often, with unexpected Kamikaze attacks), and direct and on-demand air support.

A place found and secured

USS Bismarck Sea CVE-95 loading Douglas SBD Dauntless bombers from a barge circa in 1944.

The initial role as planned early in 1941 by President Rooselevelt was a quick conversion of merchant vessels to taxi all sortts of aircraft delivered via lend-lease. They could simply be flown instead of delivered by crate, transported to an airfield, assembled and tested, which was the usual way in peacetime. The Casablanca class carried all sorts of aircraft types, including very large ones. Here USS Thetis Bay loaded with eight Catalinas and a dozen smaller types under their shadow.

When the first CVEs were starting their training, meanwhile in the Pacific the Invasion of New Georgia was near its completion (30 June-5 August 1943). This was the first major Allied offensive in the Solomon Islands after Guadalcanal, a closing point to the gruelling match that was ongoing since last August 1942 and seeing many battles. Also the operations they missed were the Gilberts invasion from 20 July 1943 at Tarawa and Abemama atolls, Nauru Island (Operation Galvanic).

It’s by the end of the year that most CVE were at last fully ready for combat, with their pilots qualified. The invasion of Makin Island in September (Marines landed from USS Nautilus) and the full invasion in November supported by the first CVEs, and among these, three Casablanca-class vessels, which air group was mostly intended for assault, with Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and Grumman TBF Avengers. These were USS Liscome Bay, USS Coral Sea and USS Corregidor.

The former was the sole loss (and first of the class), spotted at dawn on 24 November by the Japanese submarine I-175, arriving unnoticed prior to the invasion and by a single torpedo hit off a full spread. The torpedo detonated just outside, blewing up its aerial bombs stockpile, trigerring a detonation that broke her in two, with 644 going down, including flagship admiral, TG commander Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix and Captain Irving Wiltsie, plus Pearl Harbor Navy Cross recipient Cook Third Class Dorie Miller (with a new fleet carrier named after him). The latter investigation shown the destroyer screen composed of USS Hull and USS Franks were not in place when this happened and they were not zigzaging, to make support operations easier.

USS Anzio (CVE-57) at Pearl Harbor, 5 October 1944

On the 15th, escort carriers provided direct support for landings on Mindoro and the next two days. By January 3-22, 1945 some 17 escort carriers covered the approach of the Luzon Attack Force as part of Task Group 77.4. They made preliminary strikes in the assault area and covered the landings, supported the inland advance. RAdm. Sample with six carriers, provided air cover and support at San Antonio (near Subic Bay) and by February, Adm. Durgin directed his carriers at Iwo Jima.

Damaged Hellcats F6F-5 aboard USS Admiralty Islands, 20 July 1944

In March he commited his reinforced carrier group at the Okinawa campaign at the head of Task Group 52.1 (18 escort carriers). Missions included pre-assault strikes, occupation support of Kerama Retto, pre-assault strikes on Okinawa, landings support, CAP and ASW patrols, daily close support.

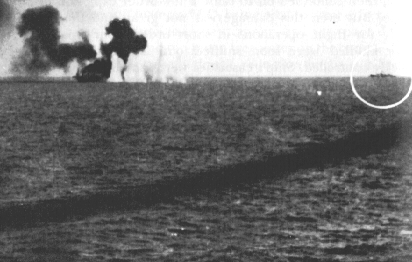

USS Gambier Bay under fore at Samar, 1944

Losses of CVEs were not heavy according to WW2 standards. Five were lost in the Pacific and one Bogue class in the Atlantic. The losses were due mostly to unexpected attacks: Naval surprise for St Lô at Leyte, she never was supposed to deal with heavy warship gunfire, Kamikazes that went through or submarines sneeking in, classic loss clauses that had few remedies but better patrolling from escorting destroyers and heavier combined AA, better CAP tactics, or just avoiding negligence in the face of clever tactics as shown by the Taffy-3 case.

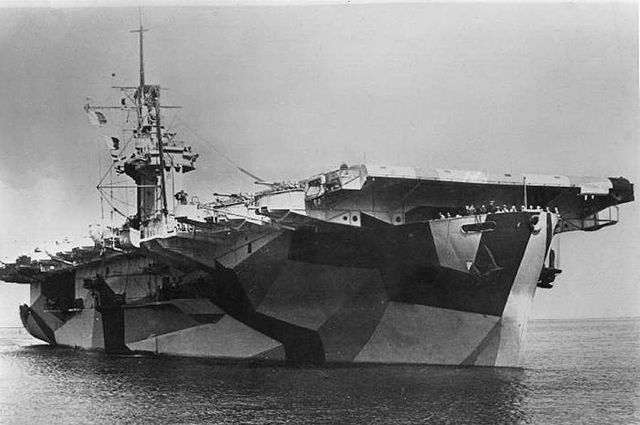

Camouflage Liveries

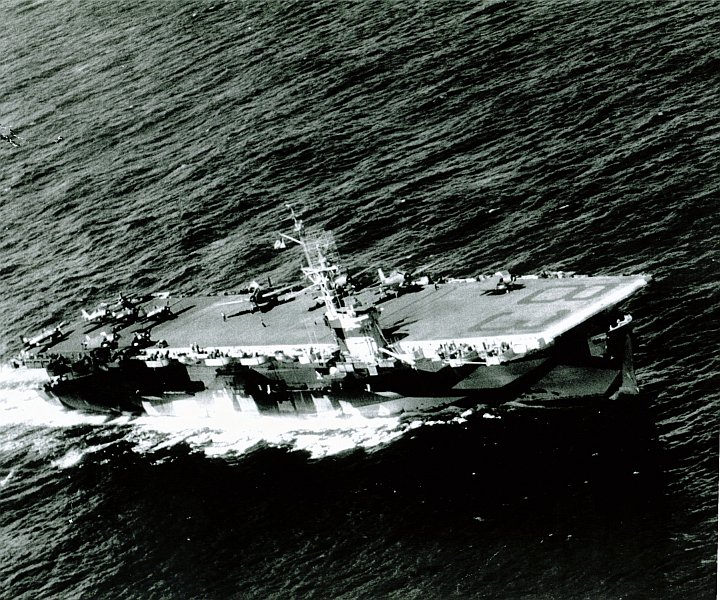

Camouflage Pattern MS-33 Design 3D for the Casablanca class.

Old author’s illustration of USS Casablanca in 1944. More recent ones ar coming, and a poster with the fifty carriers.

USS Gambier Bay as she was when sunk at the battle of Samar in Taffy 3, Leyte October 1944.

USS Casablanca (1942) specifications (to edit) |

|

| Displacement | 8,188 t. standard -10 902 t. Fully Loaded |

| Dimensions | 156.16 m long, 33 m wide, 6.32 m draft |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft Skinner Unaflow turbines, 4 Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Speed | 9,000 hp, 19 knots |

| Armament | 1 x 5 in (127mm), 8 x 40 AA (4×4), 12 x 20 mm, 27 aircraft |

| Armor | None |

| Crew | Circa 860 |

The Casablanca class coldwar career (1946-1964)

USS Thetis Bay (CVHE-1) 1950s

A bunch of these carriers stayed active for a few more years after their initial decommission in 1946-47, which was the fate of all there fifty ships. With the war of Korea however an inspection commission examined those in the best general state to be refurbished and recommissioned, at least as aircraft/helicopter carriers/taxis.

There were:

USS Corregidor: Reactivated 19 May 1951 decomm. again 4 September 1958

Cape Esperance: Reactivated 5 August 1950, decomm. 15 January 1959

Thetis Bay: Reactivated 20 July 1956, decomm. 1 March 1964

Windham Bay: Reactivated 28 October 1950, decomm. 15 January 1959

First F-86s arrive in Korea on USS Cape Esperance, Nov 1950

USS Leyte CVA-32 and Reserve Fleet escort carriers at the South Boston Naval Annex 25 July 1953

Many were still around in 1958, in long preservation, and were simply discarded and scrapped or expended as targets like Makassar Strait in 1961.

Note: They will be the object of a separate article in the cold war section.

USS Thetis Bay (CVE-90) had the longest career, as from September 1945 she joined the “Magic Carpet” fleet, and by August 1946, joined the Tacoma group, Pacific Reserve Fleet.

She was reactivated from May 1955, leaving the Pacific Reserve Fleet, towed to the San Francisco Naval Shipyard to be converted under project SCB 122, the first USN assault helicopter carrier. On 1 July, she became CVHA-1, in support of attack transports for vertical assault capabilitie, recommissioned on 20 July 1956 with the aft section of her flight deck cut away. She trained with the Marine Corps Test Unit No. 1 in Camp Pendleton and taking part in amphibious training exercises off of the California coast.

The evaluation complete, she departed for the Far East on 10 July 1957. She would returned there in 1958. In 1959 she became LPH-6 and was repaired after Typhoon Billie while in Taiwan. She put to good use her 21 Marine Corps Sikorsky H-34s to ferry aid and transporting civilians after a massive flooding. Back in the US she took part in the first large-scale night landing of ground forces by carrier-based helicopters. She was back in the Pacific’s 7th fleet in 1961, and in 1962-63 operated off the Atlantic coast and Caribbean. She took part in the Cuban Missile Crisis‘s naval “quarantine” having a marine landing team ready for action. In late 1963 she helped Port-au-Prince after a storm, providing medical aid and food supplies.

In January 1964 she was sent to the Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility in Philadelphia for inactivation work, struck 1 March 1964, sold by December 1964, BU 1966.

Gallery

A model of USS Gambier Bay

USS Sargent Bay CVE-83 underway 1944

US Navy escort carriers at San Diego circa in June 1944

USS Admiralty Islands CVE-99 ferrying planes 31 December 1944

Resources

Links

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Casablanca_class_aircraft_carriers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casablanca-class_escort_carrier

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/usa/us_cv_casablanca.htm

http://www.usmm.org/c4ships.html

https://www.maritime.dot.gov/taxonomy/term/51?page=2

https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/kaiser_shipyards/#.XDUjKs9KjjA

https://www.columbian.com/news/2013/aug/19/war-effort-clark-county-kaiser-shipyard/

http://shipbuildinghistory.com/shipyards/emergencylarge/kvancouver.htm

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ships/ships-mc.html#s4

http://www.hazegray.org/navhist/carriers/us_esc2.htm

https://www.navsource.org/archives/03/055.htm

https://www.navsource.org/archives/03/055co.htm

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/c/casablanca.html

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/histories/naval-aviation/evolution-of-aircraft-carriers/car-9.pdf

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/ships-us/ships-usn-l/uss-lunga-point-cve-94.html

http://www.navsource.org/archives/03/063.htm

http://www.navsource.org/archives/03idx.htm

https://www.navysite.de/cve/cve55class.htm

https://uboat.net/allies/warships/class/110.html

https://tmg110.tripod.com/usn_cve.htm

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/C/a/Casablanca_class.htm

https://ww2db.com/ship_spec.php?ship_id=297

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/cve-55.htm

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/how-casablancas-class-aircraft-carriers-shook-world-war-ii-188673

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Casablanca_class_aircraft_carriers

Books

John Gardiner Conway’s all the words fighting ships 1921-47

The Escort Carrier in the Second World War: Combustible, Vulnerable, Expendable!, By David Wragg, page 180

Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World, Norman Polmar, page 160

The modeller’s corner

General query on scalemates.com

https://www.cybermodeler.com/naval/casablanca/casablanca_all.shtml

https://sdmodelmakers.com/casablanca-class-escort-carrier-model.html

Videos

The Casablanca class in action:

USS Lunga point in the Mndanao sea, 3 January 1945

USS Casablanca (CVE-55)

USS Casablanca (CVE-55)

USS Casablanca at Puget Sound, July 1943, freshly completed.

Construction of this famous lead ship was awarded to Kaiser in Vancouver, Washington as seen, with a contract signed on 18 June 1942 and symbol given AVG-55, as she was already the 55th escort carrier ordered at this point for US alone.

On 20 August she became ACV-55, for “auxiliary”. Laid down on 3 November 1942 as originall (HMS) Ameer, via lend-lease she was known there MC hull 1092, first of 50 vessels, and there was a special ceremony with the director, company’s staff and many officials of the Maritime Commision and USN.

Note: I’ll spend a longer time on this one to showcase a typical career to the full. The next ships’s careers would be seen on a more succnt way.

On 23 February 1943, the second one, Liscome Bay, was transferred under lend-lease in place of ACV 55, and was renamed “Alazon Bay” (Alazan Bay in reality, Kleberg County, Texas) and changed again for Casablanca on 3 April 1942 as her sister was in between, renamed Lunga Point. Launched on 5 April that year, quickly built as promised, she was sponsored by no less than First Lady Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt.

After a quick fitting out, always for that kind of ship, she was transferred to the Navy on 8 July and this time, officially commissioned on 15 July. Firts captain was Steven Ward Callaway. He was chosen as the one who will “write the book” for hundreds of captains on similars ships to follow.

It was however discovered during her sea trials a serious defect on her single propeller, both crippling speed and agility, so she was useless basically before being drydocked for replacement. Kaiser was not surprised in some ways as such teething problems were awaited; This ship was the first to hit water after all. For some time before being drydocked she was retained by the Navy as a training vessel in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, providing there too, a model of pilot certifications proper to these fifty carriers.

Until August 1944, she basically trained all carrier squadrons for the whole class and a training vessel for crews intended for the other Casablanca-class before commission, which took just two weeks between mastering the equipment and handle these. She also generatd tons of useful data on how she handled for prolonged periods at sea, general readiness and equipment’s use. Lessons learned were implemented on the fly on the new ships in construction;

By the summer of 1944 at last, USS Casablanca was drydocked to have her propeller corrected. Following certifications, she carried out at last her first war mission, departing on 24 August with personnel, airplanes, and aviation gasoline, from NAS Alameda (California), passing under the Golden Gate Bridge and off San Francisco before heading for Manus (Admiralty Islands). After a transport mission, taxiing aicraft and making at least her first long range mission she was back on 8 October 1944 to resume at Puget Sound her role as training carrier, as she was found quite valuable for the role. Due to this she had little occasion to see combat. She started to train pre-commissioning crews for the larger Commencement Bay-class also. A storm damaged her enough to need repairs in San Diego from 22 January 1945. On 12 February Captain John Lewis Murphy took command.

Back in the same role on 13 March, she was re-routed for a new transport mission, making a stop to Pearl Harbor, and proceeded to Guam, to unload part of her cargo, followed by another stop at Samar in the Philippines, but also Manus, and Palau. From 12 May she went back home to West Coast and her first overhaul, carrying bacl wounded personnel. They were mostly diverted to Pearl Harbor on 24 June. The summer of 1945 saw her transporting more personal and material to Pearl Harbor and Guam. While mud-way to the latter, the crew heard about Japan’s surrender.

By late 1945 she retook her old rolme as training carrier, providing pilot qualifications off Saipan and was later retrofitted into a troopship toparticipate in Operation Magic Carpet fleet, repatriating servicemen from around many locations in the pacific. She arrived in San Francisco on 24 September and was back in Pearl (September-October) for a second run to stopping at Espiritu Santo, Nouméa.

Her last run was between 8 December and 16 January 1946 (San Francisco-Yokohama). Back on the West Coast she departed on 23 January to Norfolk, and be mothballed in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet from 30 May 1946, then fully decommissioned on 10 June, struck on 3 July and sold on 23 April 1947 for scrap, to a Chester Company. Her active life had been of just three years, exemplifying the way the whole class was throught to be a quick wartime expedient and little else.

But the role she played out of harm was invaluable for the whole class, giving quick and efficient training on all crews, something few aicraft carriers procured in their active life but perhaps the British HMS Argus.

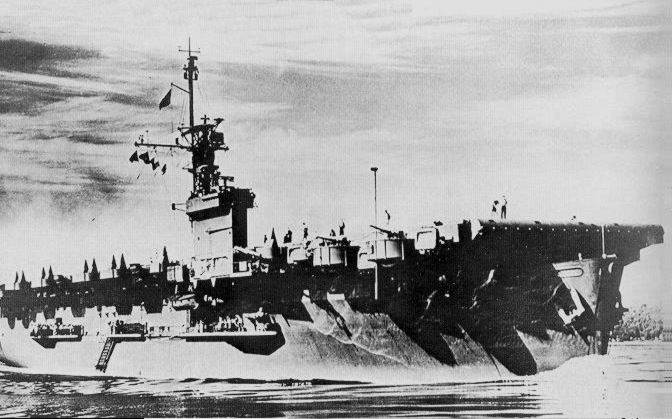

USS Liscombe Bay (CVE-56)

USS Liscombe Bay (CVE-56)

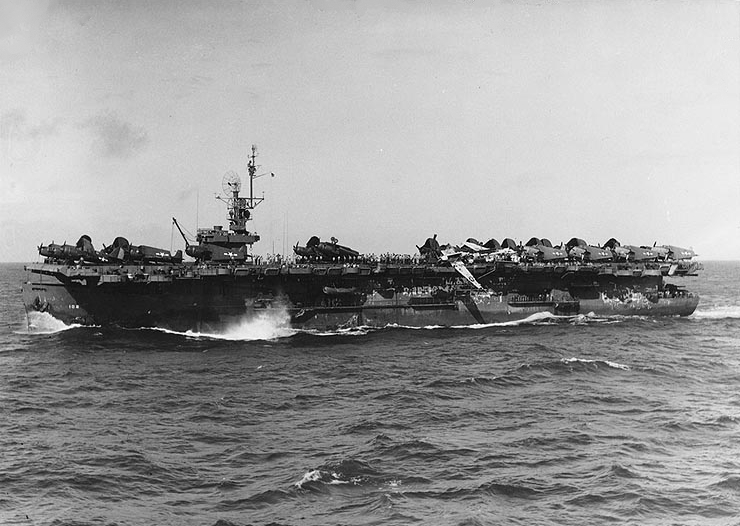

USS Liscome Bay underway in 1945

USS Liscombe Bay (CVE-56) was named after a bay on Adak Island, in the Aleutian Islands. She was commissioned in April 1943.

After commission she moved to San Diego and than took aboard 60 aircraft before proceeding to San Francisco followed by training operations. On 11 October 1943, she became flagship, Carrier Division 24 (Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix). On the 14th she received her air group and departed for Pearl Harbor, arriving on 27 October. After additional drills she was sent to join the invasion fleet of Operation Kourbash as part of Task Force 52 (RADM Richmond K. Turner), to the Gilbert Islands, her first and last mission.

USS Liscome Bay supported the invasion of Makin and proceeded to various bombardments with her air group on 20 November until Tarawa and Makin were captured. For more than 72h, her air group provided constant close air support, bombing Japanese positions, making 2,278 sorties. As part of Operation Galvanic they strafed and bombed airbases, and were called for quick support in ground operations as well as providing CAP for the landing area. USS Liscome Bay stayed with the rest of her task force to support Marines still fighting on Butaritari, whereas the rest of the fleet retired.

The invasion scrambled Admiral Mineichi Koga to send four Japanese submarines preying southwest of Hawaii, five near Truk and Rabaul to the Gilberts. Nine Japanese submarines were underway, but soon six were lost.

On 23 November I-175 (Lieutenant Commander Sunao Tabata) arrived off Makin and spotted the three escort carriers. She approached from 20 mi (32 km) southwest of Butaritari at 15 knots while the TG was traveling in a circular formation, seven destroyers, USS Baltimore, USS Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Mississippi, surrounding the three carriers. Liscome Bay was just in the center. But due to the risk of collisions they were not zig-zagging.

At 04:34, 24 November the destroyer USS Franks investigated a signal beacon, dropped from a Japanese plane, creating a screen gap and soon radar operators on New Mexico spotted a small blip (I-175 CT as she dove into position) and flight quarters were sounded at 04:50, but the crew returned to routine general quarters at 05:05 as 13 planes were prepared for dawn launching, readied on the flight deck, fueled and armed. Seven more were in the hangar but not readied, still she had a lot ammunitions stored below decks. Just as the TG made its turn to the northeast USS Liscome Bay had her side exposed to I-175, which fired a spread of three Type 95 “long lance” torpedoes.

At 05:10, the starboard lookout reported the torpedo wake, but there was little to do. It struck behind the aft engine room just as the carrier was turning, a lucky hit which detonated the bomb magazine. The resulting explosion created daylight over the whole area, with a mushroom nearly half a mile high, engulfing the ship. Shrapnel rained down 5,000 yards (4,600 m) away all around. New Mexico, just 1,500 yards (1,400 m) off had a fire starting by falling flaming debris, a sailor on USS Coral Sea being hit by… a fire extinguisher from Liscome Bay. The mushroom cloud above the ship soon reached several miles while nobody could see USS Liscome Bay anymore.

Her stern had been detached, clean through by the force of the detonation, the aft engine room was flooded instantly, the hangar and flight decks were heavily damaged, the superstructure and radar antenna collapsed on it, while a wild fire was soon out of control in the forward part of the hangar, igniting every planes parked on the flight deck which exploded in turn or fell off the deck. Fire-main pressure was lost an no pumps or fire fighting equipments worked. Other ammunition dumps soon started to detonate one after the other while gasoline was spread on the surrounding waters, catching fire. Thus, those jumping into the water had to escape underwater.

At 05:33, she listed to starboard and sink rapidly with still 53 officers and 591 salors and personal aboard. The list included Captain Irving Wiltsie, Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix, Doris Miller.

The rest of the task group started evasive maneuvers, and at 05:40, USS Morris, Hughes and Hull arrived to the rescue, only catching men dead or dying. At 06:10 USS Maury spotted two torpedo wakes, 15 yards (14 m) from her while USS New Mexico’s radar operator spotted another echo, Hull and Gridley chaging on it. Macdonough went back to rescue a few more survivors until 08:00. In all 272 survived, albeit badly burnt or injured by shrapnel. This was more casulaties than the entire Japanese garrison on Makin.

On 4 February 1944, I-175 was detected and sunk by USS Charrette and Fair.

USS Anzio (Coral Sea) (CVE-57)

USS Anzio (Coral Sea) (CVE-57)

USS Anzio (CVE-57), ex Coral Sea underway.

USS Anzio (CVE-57) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. The ship was named after the Battle of Anzio, a World War II battle in Italy. She was commissioned in March 1944 and served in the Pacific theater of operations during World War II.

Anzio first saw action during the Marianas campaign in June 1944, providing air support for the invasion of Saipan. The ship also participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, where she provided air cover for the invasion of the Philippines.

In 1945, Anzio was assigned to the Western Pacific, where she took part in the Okinawa campaign. During this campaign, she was attacked by a kamikaze plane on April 12, 1945, but managed to avoid serious damage.

After the war, Anzio was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in April 1946 and later sold for scrap in 1959.

USS Corregidor (CVE-58)

USS Corregidor (CVE-58)

USS Corregidor (CVE-58) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was named after the Battle of Corregidor, a significant battle fought during the early stages of World War II in the Pacific.

Corregidor was commissioned in May 1944 and initially served as an escort carrier for convoys in the Atlantic. In August of that year, she was transferred to the Pacific theater of operations and provided air support for the invasion of the Palau Islands in September.

The ship also participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, where she provided air cover for the landing forces in Leyte. In November, Corregidor supported the landings at Ormoc Bay, and then took part in the invasion of Lingayen Gulf in January 1945.

After the end of the war, Corregidor was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in March 1946 and later sold for scrap in 1959.

USS Mission Bay (CVE-59)

USS Mission Bay (CVE-59)

USS Mission Bay (CVE-59) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was commissioned in October 1944 and named after Mission Bay, a large man-made saltwater lagoon in San Diego, California.

During World War II, Mission Bay served in the Pacific theater of operations and participated in the invasion of the Philippines in December 1944. The ship also took part in the Battle of Okinawa in April 1945, where she provided air support for the landings and conducted anti-submarine patrols.

After the war, Mission Bay was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in June 1946 and placed in reserve. In 1951, the ship was reactivated and converted into an amphibious assault ship, redesignated as LPH-6. She served in the Korean War and the Vietnam War before being decommissioned in 1970 and sold for scrap in 1971.

USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60)

USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60)

USS Guadalcanal underway 28 September 1944.

USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was named after the Battle of Guadalcanal, a significant battle fought during the early stages of World War II in the Pacific.

Guadalcanal was commissioned in March 1944. In September of that year, she was transferred to the Pacific theater of operations and took part in the invasion of Leyte in the Philippines.

The ship also participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, where she played a significant role in the sinking of the Japanese battleship Musashi. In January 1945, Guadalcanal took part in the invasion of Luzon in the Philippines and provided air support for the landings.

After the end of the war, Guadalcanal was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in January 1947 and later sold for scrap in 1959.

USS Manila Bay (CVE-61)

USS Manila Bay (CVE-61)

USS Manila Bay (CVE-61) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was named after the Battle of Manila Bay, a significant naval battle fought during the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Manila Bay was commissioned in May 1944. In December of that year, she was transferred to the Pacific theater of operations and took part in the invasion of Lingayen Gulf in the Philippines in January 1945.

The ship also participated in the Okinawa campaign, where she provided air support for the landings and conducted anti-submarine patrols. In July 1945, Manila Bay was present during the initial occupation of Tokyo Bay.

After the end of the war, Manila Bay was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in May 1946 and later sold for scrap in 1960.

USS Natoma Bay (CVE-62)

USS Natoma Bay (CVE-62)

USS Natoma Bay (CVE-62) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was named after Natoma Bay, a small bay on the coast of California.

Natoma Bay was commissioned in July 1943 and initially served in the Atlantic, providing air support for convoys and conducting anti-submarine patrols. In November 1943, the ship was transferred to the Pacific theater of operations.

During World War II, Natoma Bay participated in a number of operations, including the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the invasion of Peleliu, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. She also provided air support for the landings at Lingayen Gulf and Okinawa.

After the end of the war, Natoma Bay was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in March 1946 and placed in reserve. In 1951, the ship was reactivated and converted into an amphibious assault ship, redesignated as LPH-8. She served in the Korean War and the Vietnam War before being decommissioned in 1970 and sold for scrap in 1971.

USS St. Lo (CVE-63)

USS St. Lo (CVE-63)

USS St. Lo (CVE-63) was named after the Battle of Saint-Lô during the Normandy Campaign, commissioned on 23 October 1943 as USS Midway and renamed on 10 October about the battle. She also freed the name for the Midway armored carrier class. She would be the first and last ship in the USN bearing that name. As USS Midway, she left Astoria in Oregon on 13 November 1943, made her sea trials, shakdown cruise, and went back to dry dock post-fixes on 10 April 1944. She made a new shakedown on the west coast and two trips to Pearl Harbor and one to Australia carrying aircraft. At last for her 4th trip she departed wit the Composite Squadron 65 (VC-65) and met Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan’s Carrier Support Group 1 in June 1944, ready for the Mariana Islands campaign. During the trip she covered the convoy and once arrived started a serie of airstrikes on Saipan with her FM-2 Wildcats claiming their first 4 kills, damagine one more dueing their combat air patrol (CAP).

On 13 July 1944, she was sent in Eniwetok, for replenishment and on the 23th she sailed for the invasion of Tinian wit the same combined air support and CAP plus ASW patrol (ASP), and operated off Tinian until returning for supplies at Eniwetok on 28 July.

USS Midway remained in Eniwetok Atoll until departing on 9 August for Seeadler Harbor, Manus, in the Admiralty Islands.

On 13 September, she ws assigned to TF 77 for the invasion of Morotai. Two days after her air group sorties for air strikes and close support of troops ashore until the 22th. In after a refueling she resumed air operations in the Palaus and was back to the new forward resupply base (FRB) in Seeadler Harbor on 3 October, learnign she had been renamed USS St. Lo. (probably with some frustration by the crew) Communication codes had to be changed but pennant remained the same. At least the crew was briefed after the Battle of Saint-Lô which happened on 18 July 1944. Soon, her career was to end, but nobody knew at the time. Her service has been relatively “cushy” without much Japanese opposition until then. But it’s ironic that she was lost just a couple of weeks under her new name.

St. Lo departed Seeadler Harbor on 12 October to take part in the invasion of Leyte with the same mission, convoy air coverage, air strikes on arrival, close air support, CAP and ASP. This commenced on 18 October. Her area of operation was Tacloban, northeast of Leyte under command of Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague in a unit known as “Taffy 3” (TU 77.4.3) with six other escort carriers of her class (including Gambier Bay) and three destroyers, four destroyer escorts as their only defence. St. Lo was off the east coasts of Leyte and Samar launching strikes on 18 to 24 October between concentratons, installations and airfields.

Before dawn, 25 October while about 60 mi east of Samar USS St. Lo launched four Avengers deployed in ASP and prepared her air group for the initial airstrikes of the beaches. The Battle started at 06:47. Her ASP would play a role in these events as it’s Ensign Bill Brooks, pilot of one of these TBF Avengers which first spotted and reported the large “Center Force” (Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita) approaching from the west-northwest, just 17 miles away. Lookouts on St. Lo also reported one of the famous “pagoda-like” superstructures on the horizon, likeli from IJN Kongo. A dedperate call was made by Rear Admiral Sprague which ordered Taffy 3 to turn south at full speed. But with only at best 19 kts, the carriers were not aboit the cut it. Kurita closed in and opened fire at 06:58.

Immediately all air groups engaged in ground support were redirected to Kurita’s force. They had to brave their AA and attacked them, using at best the surrounding rain squalls to hide and emerge for new passed, landing to resupply and taking off again with every ordnance they possesses. This went on with all available plane and with the order to proceed to Tacloban airstrip to rearm and refuel as carriers were now managing to dodge salvos, making landings impossible.

At 08:00, the heavy cruisers were racibg forward, closing in on USS St. Lo’s abnd closing by her port quarter, at 14,000 yd (13,000 m) when starting precision furing, while the carrier answered with her only 5 in (127 mm) gun (claiming three hits on IJN Tone).

There was a 90 minutes mayhem, only interrupted by desperate destroyers attacks and smoke cover. Kurita’s forward forces closed to 10,000 yd (9,100 m) bot on her port and starboard quarters straddling her when she was visible through smoke screens. Kurita’s efforts were marred by these smoke screens, destroyer and attacks combined, having suddenly to change course or dodge ordnance. Soon aicraft arrived from Taffy 2 too in the south, ans those of Taffy 1 were also ordered to arrive asap.

Eventually the IJN cruisers and destroyers broke off, turning tail at 09:20. At 10:50, as St.Lô seemed saved, the Shikishima “Special Attack” (Kamikaze) Unit entered the fray. For 40 minutes they targeted the six carries despite fierce AA opposition and except USS Fanshaw Bay, they were all hit. St Lo was hit by a single A6M2 Zero (presumably Lt. Yukio Seki) which crashed on her flight deck at 10:51, after been deviated from over USS White Plains by AA damage. The fighter was carrying a bomb which in effect penetrated the thin flight deck, exploding on the hangar port side, meeting countless aircraft being refueled and rearmed.

The world’s famous photo showing “St Lô explosion”. This was not the resulting explosion but the initial strike of the Kamikaze. She was rocked afterwards by a serie of equally violent deflagrations caused by the cookoff of so many ordnance in the hangar, fuelled by high-octane aviation gasoline. The first major explosion following created a fireball rising 300 feet above the flight deck with the largest object seen above that fireball being aft aircraft elevator, sent to 1,000 feet above. The photo (which was soon on life magazine cover) was taken by a combat cameraman aboard USS Kalinin Bay (CVE-68). It is now open source, part of the USN collection and library of congress collection. It has been featured in countless books and documentaries, as the most iconic picture of the Battle of Leyte.

Unsurpringly gasoline fire started, ingniting all fuel lines and live ammunition stockpiles causing secondary explosions, until reaching the torpedo and bomb magazine wich caused a massive deflagration, with a mushroom hundreds of feets high (as caught by a world-famous photo) which sealed the fate of USS St. Lo: She sank 30 minutes later, carrying with her 113. Of the rather numerous survivors fortunately, sadly 30 more would later die of their burning wounds. USS Heermann, John C. Butler, Raymond and Dennis picked up 434 survivors that day. More were rescued later. USS St. Lô was the only carrier to be lost after a Kamikaze attack that day. Today, the wreckage of St. Lo is a popular dive site off the coast of the Philippines, where she sank.

USS Tripoli (CVE-64)

USS Tripoli (CVE-64)

USS Tripoli (CVE-64) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy, named after the Battle of Tripoli during the First Barbary War.

Tripoli was commissioned in April 1944 and served in the Pacific theater of operations during World War II. She participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, providing air support for the landings in the Philippines, and later in the Battle of Okinawa.

After the end of the war, Tripoli was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in March 1946 and placed in reserve.

In 1950, Tripoli was recommissioned and served in the Korean War, providing air support for ground troops and conducting anti-submarine patrols. In 1958, the ship was converted into an amphibious assault ship, redesignated as LPH-10.

Tripoli served in the Vietnam War and was involved in the Mayaguez incident in 1975, where she provided support for the rescue of the SS Mayaguez, a US merchant ship seized by Khmer Rouge forces off the coast of Cambodia. She was decommissioned in 1995 and sold for scrap in 2000.

USS Wake Island (CVE-65)

USS Wake Island (CVE-65)

USS Wake Island (CVE-65) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy, named after Wake Island, a coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean.

Wake Island was commissioned in July 1944 and initially served in the Atlantic, providing air support for convoys and conducting anti-submarine patrols. In November of that year, she was transferred to the Pacific theater of operations.

During World War II, Wake Island participated in a number of operations, including the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Battle of Okinawa, where she provided air support for the landings.

After the end of the war, Wake Island was used to transport US servicemen back home. She was decommissioned in June 1946 and placed in reserve.

In 1954, Wake Island was transferred to the French Navy, where she served as Dixmude. She was decommissioned in 1960 and later scrapped.

USS White Plains (CVE-66)

USS White Plains (CVE-66)

USS White Plains (CVE-66) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy, named after the city of White Plains, New York.