The US Navy is remembered in WW2 for its amazing industrial effort to rebuilt a fleet after the losses at Pearl Harbor, with a scale that steamrolled the Japanese, reclaimed the Atlantic and mastered the Mediterranean. It was the instrument of the “pax americana” of the cold war. But one important aspect of the operations at sea was amphibious, and that was something relatively new for the US Navy. A whole guidebook and its doctrine, plus the landing crafts, landing ships and support ships that came with it had to be written. The US Navy proved up to the challenge, and that of combined operations with other allies on a multitude of occasions during the war. This, and the task force centered around the aircraft carrier were perfected during the war and became so evident during the cold war that we take them for granted. But all has to be done from scratch in 1942.

Lessons were learned and tools were perfected, so much so that at Okinawa in February 1945, the Japanese faced a perfectly oiled machine, improved at each operation, while themselves found more ways to defend with limited resources. Amphibious Operations became after WW2 even one of the speciality of the US Navy and its allies, so much so that it became de facto a supplementary deterrence. For those who thought these skills were lost, Inchon was there to showcase a “by the book” landing operation with decisive effect (until the Chinese intervened, North Koreans were on the run), even if it Operation Chromite was extremely risky. In this long article we are about to see all amphibious operations (briefly for the best known) in which the US Navy participated in WW2, the doctrine, and the ships and crafts that were built in support of these.

The US Marines relative knowhow

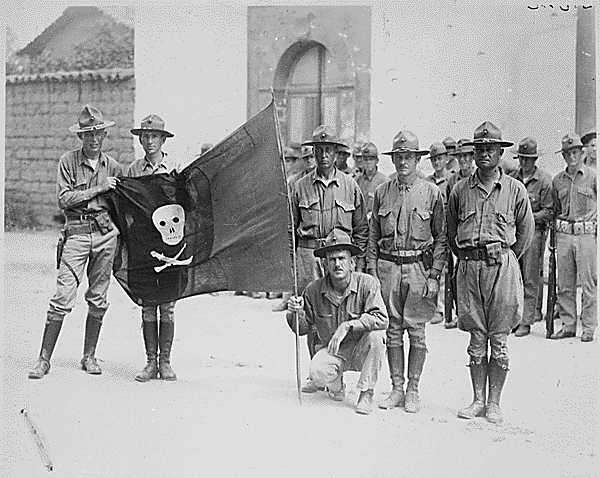

US Marines in Nicaragua, 1932, showing their captured Sandinist flag

Indeed, the only component of the Navy that had any significant experience in 1939, was the US Marines, former continental Marines of 1777. But “amphibious” operations were performed the old way: In 1898 in Cuba, US Troops which landed at Baiquiri just walked on the pier (they were the first, on June 22). At Vera Cruz in 1914, whaleboats carried 502 Marines (2nd Advanced Base Regiment) and 285 “Bluejackets” (armed Navy sailors from USS Florida and Utah) to the shore.

Landing parties always has been part of each navy rule book and the battleships and cruiser’s dismounted saluting guns, machine guns and rifles were used to form “landing parties” complementary to the Marine troops, also an old institution going back to the XVIIth Century. The “Projection of power” however only counted on these small boats and the support of big guns and there were few innovations.

During the great war, the US Navy entered late in the game and missed taking no part in the only significant Amphibious operations of the time, the famous Gallipoli Operations of 1915 of course, also the less well known Battle of Bita Paka, Siege of Tsingtao and Battle of Tanga, while the British even pioneered commando operations at Zeebruge. US Marines did took part in the fighting, but on land, like the famed “Devil Dogs” at Belleau Woods. During the interwar, US Marines participated in a few operations in south and central America called the “banana wars”, in Panama, Cuba, Veracruz, Haiti, Santo Domingo, and Nicaragua, all in the frame of the Monroe doctrine.

Summary

⚔ Operation Torch

⚔ Operation Husky

⚔ Operation Baytown

⚔ Operation Avalanche

⚔ Operation Shingle

⚔ Operation Overlord

⚔ Operation Anvil Dragoon

⚔ Operation Watchover

⚔ Goodenough Island Battle

⚔ Operation Cleanslate

⚔ Operation Toenails

⚔ Makin Campaign

⚔ Operation Galvanic

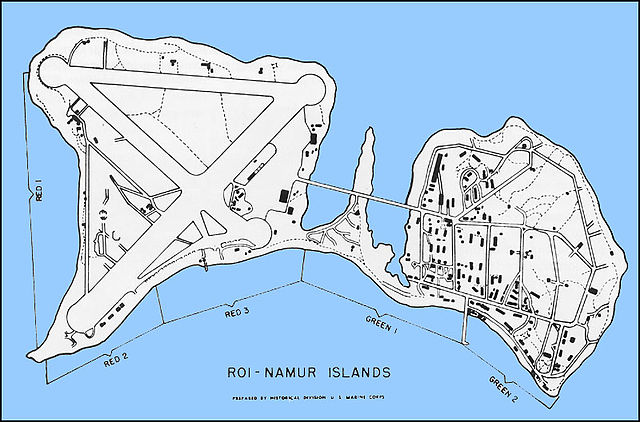

⚔ Operation Flintlock

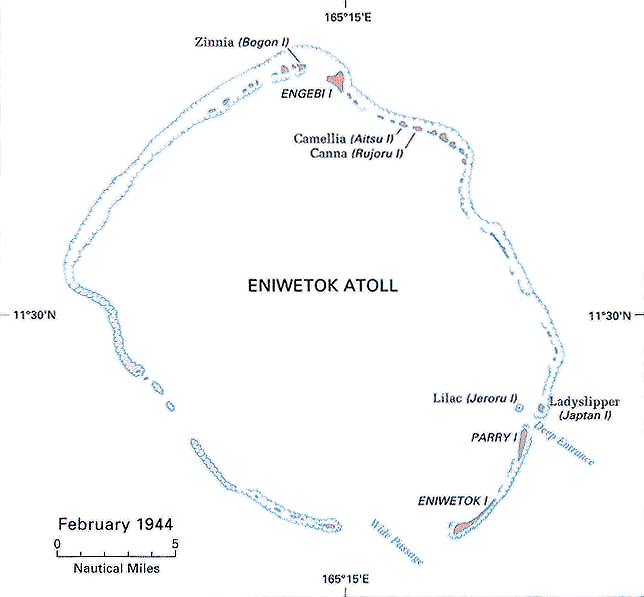

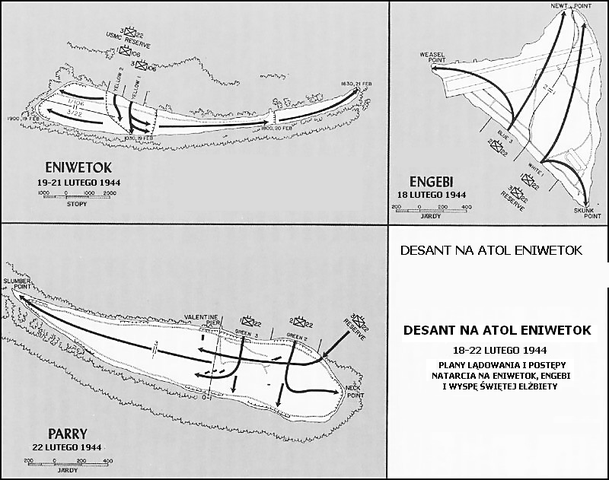

⚔ Operation Catchpole

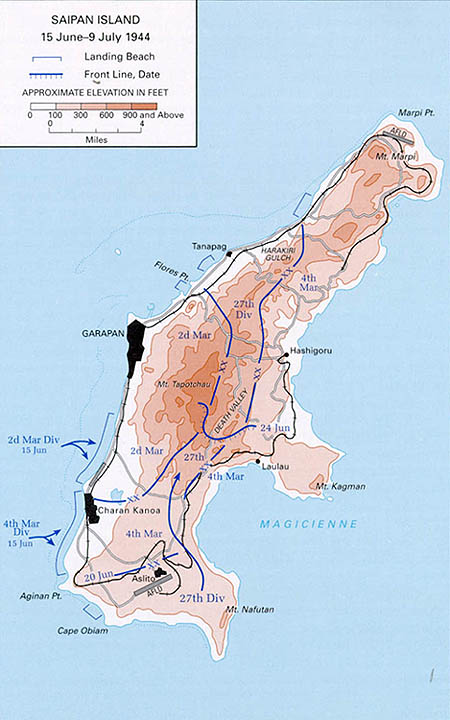

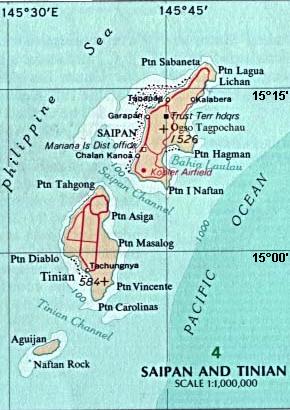

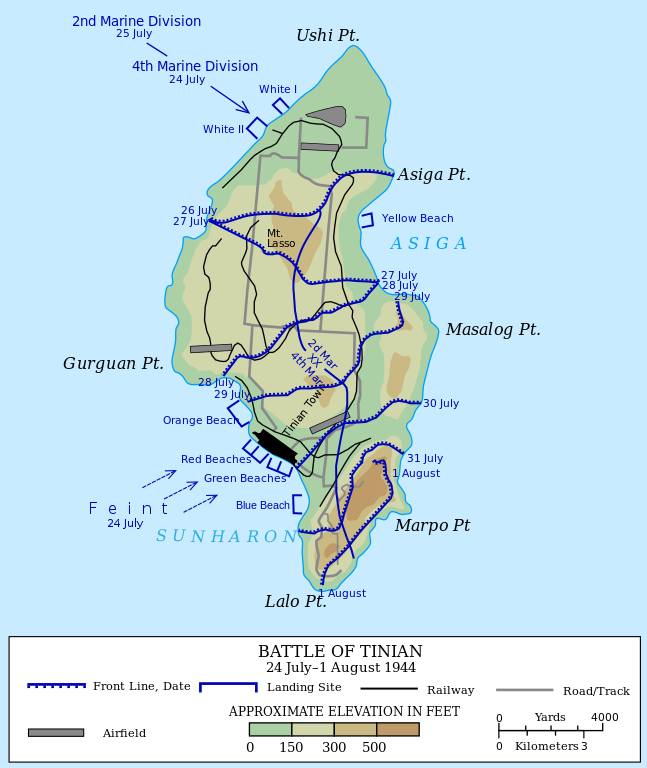

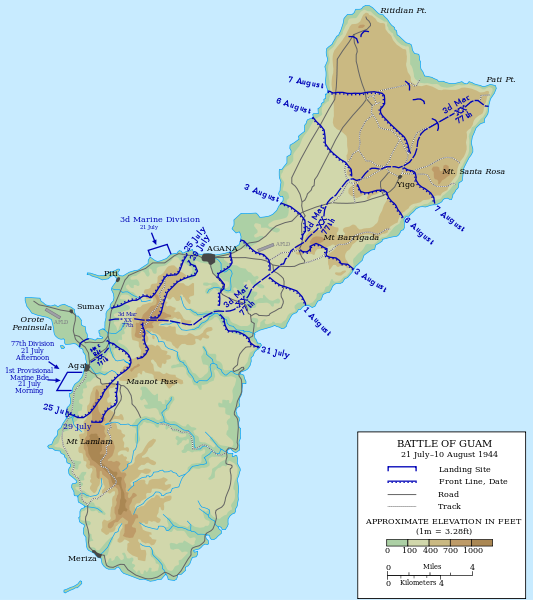

⚔ Operation Forager

⚔ Operation Detachment (Feb. 1945)

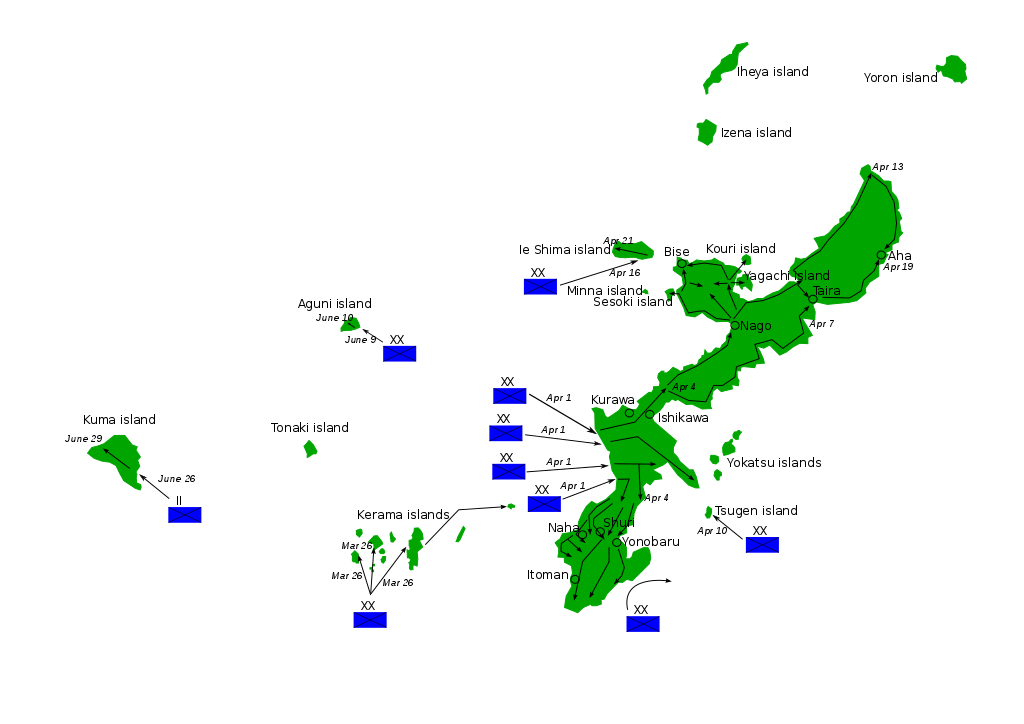

⚔ Operation Iceberg (Feb. 1945)

⚔ Operation Downfall – The 1946 Invasion of Japan

Early Doctrine

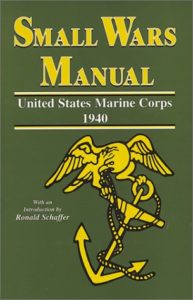

This was consolidated in the “Small Wars Manual” in 1935. The latter fixed tactics and strategies for engaging in certain types of military operations, at the destination of the USMC. The corps was long seen as the nation’s overseas police and initial response force. For sea-based power projection, it had to be tailored for “sudden and immediate call”. Both its “natural fit” and experience of a series of guerrilla wars and military interventions which started in 1890, the USMC started to systematically analyze the character and requirements of these operations., formulated in an official report by Major Samuel M. Harrington of the Marine Corps Schools.

This was consolidated in the “Small Wars Manual” in 1935. The latter fixed tactics and strategies for engaging in certain types of military operations, at the destination of the USMC. The corps was long seen as the nation’s overseas police and initial response force. For sea-based power projection, it had to be tailored for “sudden and immediate call”. Both its “natural fit” and experience of a series of guerrilla wars and military interventions which started in 1890, the USMC started to systematically analyze the character and requirements of these operations., formulated in an official report by Major Samuel M. Harrington of the Marine Corps Schools.

It was published in 1921 and later expanded by another report from Major C. J. Miller (154-page) concentrating on the 2nd Marine Brigade’s operations in the Dominican Republic (“Diplomacy and Spurs in the Dominican Republic in 1923”). Both were serialized in The Marine Corps Gazette with additional articles on the subject, making their way also in “Proceedings” at the U.S. Naval Institute.

These were published together in the manual “Small Wars Operations” of 1935, revised in 1940 as the “Small Wars Manual”, now a classic of military science which remains relevant today in terms of doctrine. It was still encouraged reading by James Mattis (1st Marine Division) in 2011. Elements of landing operations can be found in chapter V. “Initial operations” and X. “River operations”.

So the American experience of amphibious operations fundamentally saw little progress in their operative form, but the doctrine saw the obvious advantages at taking a port which had existing infrastructures, even if defended, and diversionary attacks on an undefended beach. In the first case, the ships just closed to the pier, while in the second case, men needed to be trans-boarded onto small boats, so there was two steps, covered by the Navy’s guns as a fleet could be spotted from the shore and reinforcement sent in between.

The use of new assets like specialized crafts (like the British X-lighters of 1915) was not at the order of the day, nor the integration of air power, limited to reconnaissance for planning and gunnery spotting (the 1st Marine Aviation Force was created in July 1918). The use of submarines for commando operations was also not there yet. The “small wars manual” was a much more global frame, also encompassing occupation duties.

There was a conceptual breakthrough in 1921 when Major “Pete” Ellis wrote “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia”, a secret manifesto proving inspirational to Marine strategists, to win a war in the Pacific. It was visionary as in this scenario the US Navy had to fight its way in the Pacific, taking back Japanese held islands, the Marshall, Caroline, Marianas and Ryuku island groups. It defined the concept of forward bases. Ellis stressed high-speed movement of waves of assault craft covered by heavy naval gunfire and close air support, with decision taking place on the beach itself.

He stressed the need for infantry covered on the beach by machine gun units, light artillery, light tanks, and combat engineers to defeat obstacles. He also saw the need to have protected landing craft against shrapnel and machine gun fire, taking the failure at Gallipoli as an example. But in peacetime, there was no point at making a pre-emptive occupation of these islands, which would have needed a considerable manpower. Oddly enough, this was the Army that made the best effort in designing a small landing craft for riverine operations during the interwar: These partially soft boats (made on wood and canvas) were to be stored and transported by trucks on the spot. Their early studies and efforts would culminate later in the LCVP and LCM.

So basically, if some studies were ordered in 1940 and the book reprinted, no significant efforts were made to formulate a new doctrine or forge a more specialized amphibious component. It largely depended on, of course the participation of the US to the war, which was at that point not evident, and to the nature of operations (countries in the hands of the axis and grand strategy). The first real tests were of course almost simultaneously Operation Torch, 8 November 1942 in North Africa, and earlier at Guadalcanal on 7 August the same year.

Until then, the Corps was preoccupied in Central America, and the Navy was slow to start training in how to support the landings, but in 1940 the British needs and the lend-lease program naturally led to US Industrialist to answer request for landing crafts. The tools eventually were ready even before the US entered WW2, but not the doctrine. The Navy would learn it on the fly, until 1945, and make it almost an art form, a precision machine, despite the adverse nature of the operation itself. It also included riverine operations (like the crossing of the Rhine in 1945).

The two developments trends

-The first one, “indigeneous” was only concerned by small operations (as we saw above) either in the Carribean, prewar US Marines peacekeeping interventions and the island chains of the pacific, where the function of a landing was to provide facilities for an advanced base of operations, for fleet and naval aviation support. Troops and equipments needed to be transported over great distances and landed without an opportunity to regroup. Transport ships were to be “combat-loaded”, with matériel landed first, more accessible.

But of course it was only for a low-intensity area of operation. The interwar saw the US Marines and US Army try to work out a serie of small, easy to deploy and carry small boats. They were just an evolution of the old boats carried on the larger ships, a method still used by the Germans in Norway in 1940. But these early landing crafts were supposed to be fast loaded and then put to sea using davits. The effort was translated during wartime into the LCVP and LCM.

-The second line of development concerned the “mothership”, the small boats carriers themselves. It was assumed before the war that merchant vessels would be requisitioned for the task, converted with heavier and more adapted davits and booms, plus defensive armament. In the late 1930s, the maritime commission started to look at a specialized marine transport, tailored for the task. It would incorporate a stern ramp for rapid loading of lighters usually carried on deck. These became the attack transports USS Doyen and Feland, large enough to carry a Marine battalion each of the Marine Expeditionary Force.

The commission looked at their next choice and liked the minelayer USS Terror as having lots of internal room to carry vehicles. Thus in 1943, two minelayers derived from the Terror and four netlayers were converted as LSVs or “Landing Ship, Vehicle”. But no development of ramp-loaded vessels was done subsequently. In the meantime, due to the lend-lease effort and considerable British needs, precise, on the topic, generated a large fleet of beaching ships and crafts, better tailored for the European theater. The British Amphibious warfare development and design was earlier in the game and had a great deal of influence over US planners. Some British ships were even leased and tried.

With the European invasion came a great density of tanks and vehicles, and this far outmatched all the lighters, ramp ships or converted merchant vessels put to sea combined, so the Royal Navy had the idea of a dedicated vessel called the tank, landing ship, the first improvised and tested, starting with lake Maracaibo shallow-draught tankers. It was a success that was translated into a tailored design, but only the USA had the industrial capacity to deliver it. And so was born the LST.

Further down the line, two types were envisioned: An Atlantic type Tank Landing Craft (LCT) crossing the ocean under its own power, and a smaller one carried by a mothership, in effect a powered floating drydock seaworthy enough to make the crossing. The “TLC carrier”. These became respectively the LST, LCT and LSD. The first evolved into an even larger type, the LSM. In these denomination, S meant “ship” and therefore autonomy while “C” meant “craft” and the need to be carried on site by a ship. Another wartime innovation was the birth of the LCI(L), a dedicated ship to carry infantry. Its origin was again, British, the latter searching a rapid disembarkation type for a Dieppe type limited amphibious operations. Its basic hull form was so great it was found an excellent basis for many derivatives and for support tasks.

The large motherships required ended as conversion of the mass-produced Victory and C3 classes, easing maintenance and training. None had the stern ramp. Landing operations required the troops to climb down rope ladders and nets into the small crafts, requiring optimal meteo, calm seas. The “attack” denomination was linked to their special accommodations with quick-service davits.

It was discovered in operations also that ships could not be close enough to the coast for effective close support gunnery, and so a family of landing craft vessels was developed for the task of providing close in artillery support and AA defense. Some were armed with guns and mortars, and beached like the rest, others unleashed a preparation barrage of rockets. Others provided AA cover.

The need for fast delivery attack motherships also motivated the conversion of older vessels for the task, with smaller capacities: These were conversions for the US Marines of a large quantity of former WW1-vintage ‘four piper’ destroyers, camouflaged and called the “green dragons”, as were many LCI(L) operating in the Pacific. Another interesting close support vessel was the PGM or “Motor Gun Boat” converted from SC and PC sub-chasers.

Towards 1943 also, the US admiralty realized that command and control needed specialized ships and soon conversions were made, for a number of specialized command ships called ACG. They were disarmed and required and escort, but had extensive C&C facilities radios, surveillance and fighter control radars, and the need became so acute that in 1944, the Coast guard donated a number of their Bibb class vessels to be converted as such, not counting the numerous destroyers converted as picket ships.

The light seaplane tender Biscayne was also converted. Down to the beached, for local C&C, specialized vessels were also converted from landing crafts, but also patrol and minecraft more of less “in the field” and never receiving a proper designation. This experience led to new ships being built or converted for the task during the cold war.

US WW2 Amphibious Operations (Europe)

Operation Torch – 8 November 1942

This was the largest amphibious operation of the war so far, and first engagement of US Troops in the Western hemisphere. Indeed in August, In Guadalcanal US Marines already landed in force, in Japanese-occupied Guadalcanal.

The naval forces were under overall naval command of H. Kent Hewitt. Naval participation of Canada, the Netherlands and Australia was counted in addition to the US Navy and Royal Navy, in total 350 warships escorting and covering 500 transports for a total of 850.

In total 107,000 troops were landed, among which 35,000 in Morocco, 39,000 near Algiers and 33,000 near Oran. The US main landing, Western Task Force, was aimed at Casablanca. It was composed of American units with Major General George S. Patton in overall command and Rear Admiral Hewitt for naval forces and came in part directly for the US Coast. The Center force, comprised notably the 1st Infantry Division (famous big red one), 1st armoured division and 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, targeting Oran.

The eastern TF (Algiers), comprised mostly British troops, the 78th IR, two British commando units and US troops, the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. The British vehicles troops, ships and planes supposedly used large stars and strips flag. It was tactic to quell the supposed anglopobia of Vichy troops in the this sector after the attack on Mers-El Kebir. The invaded territories were indeed French-held, but upon the armistice conditions, neutrality should be defended by force.

It was an awkward situation which at least promised a fight that was supposed to be brief, if any, for US troops. An attempt to send a delegation to start a parley was quickly take prisoner. On 7 November, pro-Allied General Antoine Béthouart attempted a coup d’etat against the French command in Morocco but was also arrested, while the General Girault, smuggled up in Eisenhower’s HQ refused to take any part in the operations after being refused the overall command of allied forces in North Africa. De Gaulle was not informed.

In short order, the landings were successful, but fired were shot depending on the loyalty of local commanders. At Port-Lyautey (Safi Beach in particular) for example, resistance was fierce. US troops landed under heavy artillery, MG and snipers fire. This was the only place where no preliminary bombardments took place. That error was not repeated and further landings were made with heavy preparation, the ships present bringing this firepower. The naval forces present at Torch comprised the following:

Western Naval Task Force: All USN, 3 battleships, 5 carriers, 7 cruisers, 38 destroyers, 8 fleet minesweepers, five tankers, under command Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt. They covered the 91 vessels strong Assault Force, including 23 “combat loaders”, early LSIs.

USS Ranger‘s Wildcats (Western TF) made ready to take off during Operation Torch.

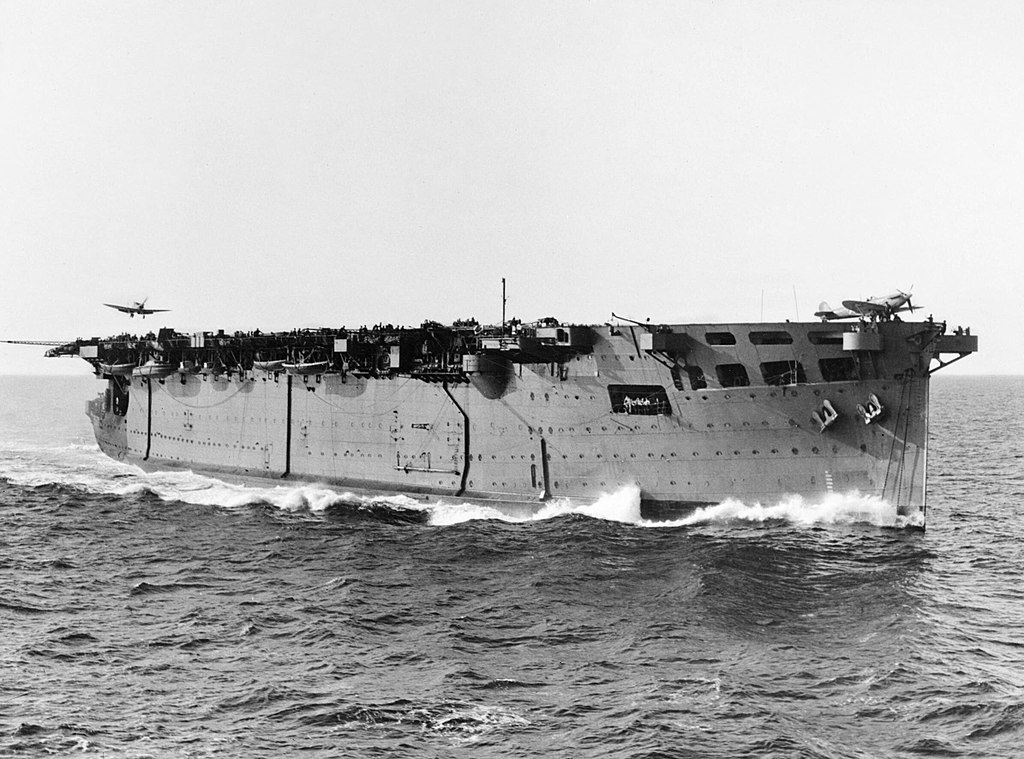

USS Argus (eastern TF) during Operation Torch.

HMS Nelson (Eastern TF) shelling its objectives during the 9 November.

Naval aviation proved useful not only to down all and any French planes in the area, as there were many attempt fro the local French air force to bombard the ships, and in-between they destroyed road convoys bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. The naval episode was called the Naval Battle of Casablanca. This was a sortie of French cruisers, destroyers, and submarines to opposing the landings, and a cruiser, six destroyers and six submarines were destroyed, by gunfire or aviation, while the incomplete French battleship Jean Bart duelled with USS Massachusetts, which was left unscaved while two U.S. destroyers were damaged. Once the main French naval base remaining here was silenced, the landing forces were safe, apart for remaining aviation further inland.

There was also a naval action during Operation Reservist (center TF, Oran) which failed as the two Banff-class sloops which entered the harbor were both sunk by crossfire from French vessels. The Vichy French naval fleet later broke from the harbor and rushed towards the invasion fleet, only to be sunk or driven ashore. Shore batteries had to be silenced too, as some fired on the invasion fleet as well. Arzew battery was a major threat for example, and was took by the 1st Ranger Batallion. Further inlands, airborne landings were tasked to secure airfields. Others were attacked by air.

At the end of naval operations, the French lost a light cruiser, 2 flotilla leaders, 5 destroyers, 6 submarines and 1,346 men (KiA) while the allies lost the escort carrier HMS Avenger (sunk with loss of 516 men) 4 destroyers, 2 sloops, 6 troopships, a minesweeper and one auxiliary anti-aircraft ship lost, plus 1,100 KiA combined. The axis lost most of their 24 submarines deployed here (14 Italian, 14 German). This was by no means a promenade.

One of the worries of the high command was a sortie of the remaining fleet at Toulon, which was always possible and would have potentially grave consequences by falling on one of the three isolated fleets. But it never happened fortunately for several reasons, and on November 27th, the Germans, fearing the fleet would escape after Darlan’s swapping alliance in North Africa (he was the de factor successor and representative of the head of Vichy France, Marshall Petain, in North Africa), invaded the free zone and attempted to invade Toulon, resulting in the scuttling of the fleet.

The Jean Bart in Casablanca

Of the many lessons of this first large amphibious endeavour, it was shown that preliminary shelling was always a pre-requisite, that the terrain needed to be analysed in detail, out of the maps (in person). At Oran (Center TF), periscope observations had been carried out, but no reconnaissance parties landed on the beaches to determine local maritime conditions. As a result, if landings at the westernmost beach were delayed, eastern beach saw damage to landing ships caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars.

Intel about local conditions became standard procedure afterwards and were systematically used in amphibious assaults, until Operation Overlord and Anvil Dragoon. It was called the “pre-invasion reconnaissance” and often carried out by marine commandos by night, often coming from a submarine and inflatable boats. It not only consisted in looking for natural obstacles but also man-made ones, and disabling them in some cases.

Operation Husky – 10 July 1943

US Forces preparing to embark on LSTs in French Tunisia before departing, in 1943.

The Second major amphibious operation in the Mediterranean was thee Allied invasion of Sicily, once the remainder of Italo-German forces not captured in Tunis fled to this island. Codenamed Operation Husky, it saw the Allies take the island by combining a large amphibious and airborne operation in the south, followed by a six-week exploitation on the rare coastal roads, and the fall of Messina at the northeast tip, looking to the Italian peninsula, on 17 August.

It was preceded by a diversion operation, a serie of deceptions among which the famous Operation Mincemeat. The landings took place during the night of 9–10 July 1943. Italo-German opposition has been fierce at first while disagreements between the two main allied commander, Montgomery and Patton, led to some interrogations on the follow-up. As the result of the Operation, Benito Mussolini was toppled from power as the Allied invasion of Italy was set in motion. Italy soon stopped offensive operations and started to negociate peace (secured in September 1943). The operation also diverted considerable German forces from the Eastern Front at the time of the vital battle of Kursk. More forces were later permanently fixed in Italy until the end of the war.

Naval forces at Husky:

These were under overall command of A. Cunningham, divided into several Task Forces:

The Covering Force (to prevent a sortie of the Italian Navy), the Eastern Naval Task Force which carried the Eastern Task Force (8th British Army) and tasked of Naval gunfire support along the invasion roads, and the Western Naval Task Force which carried the 7th U.S. Army and for fire support as well.

The 8th U.S. Amphibious Force (Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt) comprised two destroyers squadrons, DesRon 7 (USS Niblack, Benson, Gleaves) and 8-16 (USS Wainwright, Mayrant, Trippe, Rhind, Rowan) as well as “Shark Force” (Dime Force, TF 81, Rear Admiral John L. Hall Jr. wich landed the First US Division at Gela), the Cent Force TF 85 (Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk), landing the 45th Division at Scoglitti, the Joss Force (TF 86, Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly), landing the Third Division at Licata.

Were deployed also the Cruiser Division 13 and Destroyer Squadron 13, escorting nine British LCG(L) and eight LCF(L), and four LST Groups, two LCI Flotillas, several LCT Groups, deployed with HMS Princess Astrid and Prince Leopold. On the US side (86.3 Escort Group, Commander Block), were carried by USS Seer (AM-112) and USS Sentinel (AM-113). The escort counted small ships, 7 PCs, 26 SCs, and 6 YMS (minelayers). The 86.5 Train comprised the USS Moreno (AT-87), Intent, Evea and Resolute with USS Biscayne (AVP-11) as flagship. 86.9 was Joint Loading Control (Captain Zimmerli) in addition to the Kool Force (Floating Reserve).

They landed a multinational forces, 160,000 strong with 600 tanks, 14,000 vehicles and 1,800 artillery pieces, in majority American, but also with British, Indian and Canadian contingents as well as Free French. Together with the navy and air, plus support personal about 475,000 took part in the operation.

A Canadian Sherman lands from an LST in Sicily.

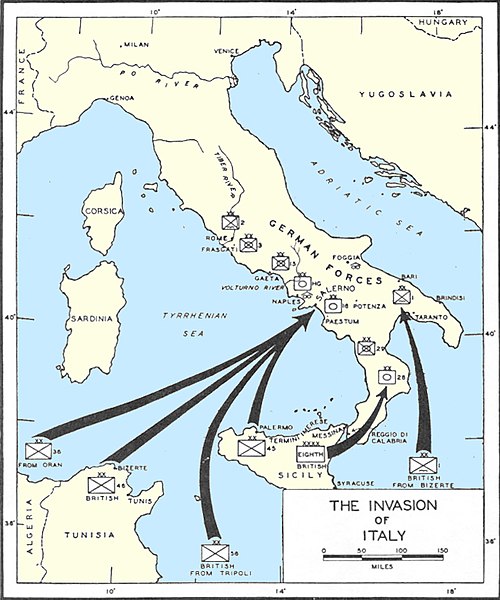

Operation Avalanche – 9 September 1943

Operation Baytown, 3 September 1943, British troops lands at Reggio from US LCIs used by the Royal Navy.

Operation Baytown – 3 September 1943: After Sicily, the next logical step was of course Italy itself. At the time it was planned, Italy was still a belligerent and Mussolini in power. It is not treated here, as being the British side of these allied landings.

Baytown was a diversionary landing, by the British XIII Corps, which included the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, in the “tip of the boot”.

As Montgomery predicted, the landing met little opposition, as German troops in the area rapidly withdrew northward. The 8th army only met a few blocking units, machine guns nest in well prepared positions, minefield, ect. The pincer movement with the second allied landing northwards never took place, but Operation Avalanche materialized anyway. In between Operation Slapstick saw the British 1st Airborne Division British, not coming from the air but a landing in the port of Taranto (Major-General George Hopkinson). They were opposed by their perfect nemesis, the 1. Fallschirmjäger Division but their mission was a sucess.

Operation Avalanche was the meaty bulk of these landings, on 9 September. On the naval side, it was under responsibility of the Western Task Force (Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, USN), covered by Force H (Vice Admiral Sir Algernon Willis, RN). The forces landed that day in Salerno comprised the U.S. Fifth Army (Mark Clark) with the support of the British X Corps (Lt. Gen. Richard L. McCreery). Also landed on the southern beached the U.S. VI Corps (Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley), to be buffered by the Army Group Reserve, the U.S. 82nd Airborne and the U.S. 1st Armored “Old Ironsides” Division. Opposing forced were led by Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, which had under command the XIV and LXXVI Panzer Corps.

LCTs landings at Salerno, 9 September.

-Task Force 80: Western Naval Task Force carried the Fifth Army (Brit. X Corps + US VI Corps)

-Task Force 85: Northern Landing Force, British X Corps.

-Task Force 81: Southern Landing Force, US VI Corps

The decision had been taken to assault without previous naval or aerial bombardment. It was to achieve surprise. But this was not achieved and the Germans expected the assault, having previously well prepared their positions, between minefields and MG nests. Offensive was slow, and the 16th Panzer division nearly pushed back the troops at sea unil stopped by a vigorous naval artillery barrage. On September 12–14, six divisions counterattacked and the situation degenerated. Clark directed from the frontline during the beach head defense, earning a Distinguished Service Cross, but he was nonetheless criticised by his poor panning. Only with the Salerno beachhead secured, the Fifth Army could push northwest, towards Naples, on 19 September. From then on, Avalanche was over, the campaign of Italy was now ongoing. There will be more landings through: The mountainous geography of Italy favoured the defenders, but the coast, helped the allies which had the mastery of the sea to bypass these strongpoints and defensive lines, thus favouring more landings northwards.

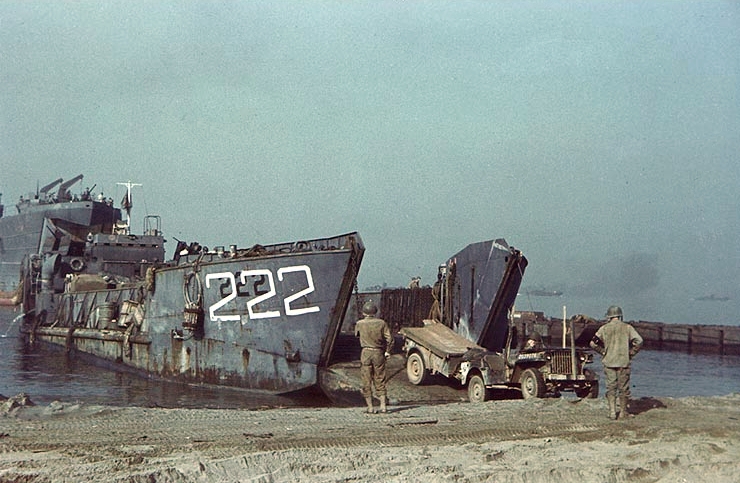

Color photo of a Jeep landing from LCT 222

Gen. Mark Clark onboard USS Ancon during the landings on 12 September. Ancon (AGC-4) was one of the command ships related to the Appalachian/Mt McKinley class (15 ships).

Operation Shingle – 22 January 1944

The Battle of Anzio was associated to the landing itself – Operation Shingle, started on 22 January 1944, culminated with the capture of Rome on June, 6, 1944. The success of an amphibious landing supposed two factors: The terrain itself, unfit for a landing with its reclaimed marshland surrounded by mountains, and surprise, swiftness for the invaders once landed. While the first was achieved, the second was not. Mark W. Clark, commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, was supposed to made it clear to General Lucas, but the latter preferred to take days to consolidate his positions in case of a counter attack, and to have all his men and vehicle, instead of pushing right away. At that stage, so far north, there was nothing stopping the allies to reach Rome, the Germans were elsewhere. But as an infuriated Churchill put it, “I had hoped we were hurling a wildcat into the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale”.

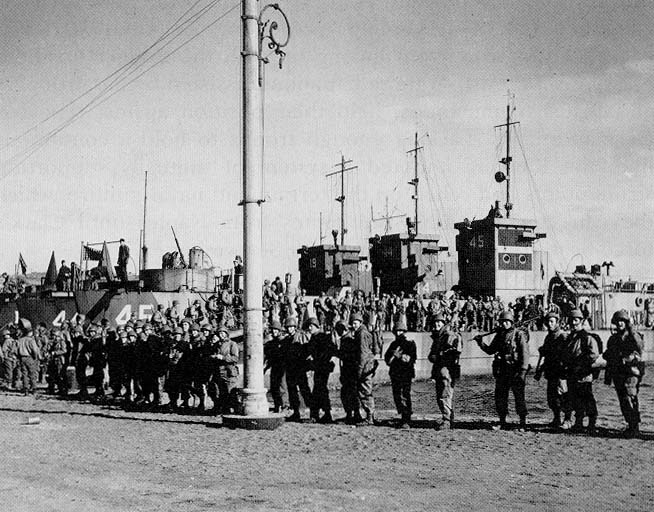

The 3rd ranger batallion, out of the LCIs.

Instead, Axis forces soon mobilized and went there in force, notably Kesserling’s 4th Parachute Division and the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, noth elite units well versed in ambushes and defensive operations. As a result, Rome which could have been reach in the evening by Luca’s spearhead, would have to wait for five months. After Lucas’s push was stopped by these units, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier and 71st Infantry Divisions had arrived on the beachead and hell was unleashed. When this threat was dealt with, allied forces soon had to deal with the linchpin of German defenses here, Monte Cassino.

Order of battle

Rear Admiral Lowry’s flagship, the amphibious command ship USS Biscayne, anchored off Anzio

Task Force 81: Allied naval commanders Rear Adm. Frank J. Lowry, USN and Rear Adm. Thomas H. Troubridge, RN.

Thier responsibility was to carry and land 40,000 soldiers (US, British, Canadians and 5,000+ vehicles) in several waves.

-Troubridge commanded “Peter Force”, British and Canadians protected by an invasion fleet of two cruisers, 12 destroyers, 2 gunboats, 6 minesweepers, and four transports carrying 63 landing crafts making the landings in rotation. It took place at “Peter beach”, 9.5 km north of Anzio (6 miles).

-Semi-independent was Ranger group (6615th Ranger Force, Col. O.Darby) landed by a single transport, a submarine chaser and 7 landing craft, attacking directly the port of Anzio.

-Lowry commanded the X-Ray Force:. The largest contingent, it comprised the 3rd Inf. Division and 504th parachute regiment, dropped in advance in some objectives. The force was landed by an small armada of 166 landing craft, protected by 2 light cruisers (USS Brooklyn and HMS Penelope), 11 destroyers, 2 DEs, 24 minesweepers and 20 subchasers to secure the advance and the flanks. It landed east of Nettuno, 6 miles east of Anzio.

The initial landings were unopposed, albeit a few Luftwaffe strafing runs which cost 30 killes and 97 wounded to the allies, from the few German forces present there in addition to aviation: 200 Germans had been taken as POWs. The 1st Division made it 2 miles (3 km) inland and the Rangers captured Anzio’s port while Nettuno fell, while the British 3rd Division penetrated 3 miles inland.

For the first time, armed liberty ships would take their share of the fighting: On 22-30 January 1944, SS Lawton B. Evans, shelled by German shore batteries and aviation endured a prolonged barrage, but the crew fought back with their own armament, and managed to shot down five Germans. This was the last large amphibious operation in the Mediterranean threater before Anvil-Dragoon in August.

Supplies brought by LSTs in Anzio.

Operation Overlord – 6 June 1944

By far the most famous landing of WW2, in scope and significance. For two years, Stalin asked the allies to open a second front in Europe, much to the annoyance of Churchill which knew his forces were not ready for such an endeavour. Two attempted plans were made however to at least give the chage to Stalin, code-named Operation Roundup and Operation Sledgehammer in late 1942 and 1943, but neither was found to be practical or guaranteed to succeed. The force buildup was not there yet.

In late 1942, the “green” US troops needed to gain experience, and were proposed the mildest theater of operation possible at that time, French North Africa. It was a good introduction, until Rommel set the tone at Kasserine Pass. This front at least solved the question of the axis presence in North Africa for good, but for many high ranking staff officers in the US Army, the next phases of Sicily and Italy were an unnecessary diversion. By mid-1944 it was clear that German forces deployed in Italy were not a great diversion of what was the opposing mass in combat in the east, and after the failure of Anzio and slow progress in front of Cassino, preparations for a landing in France were back, front and center. Since landings were no longer a priority in Italy, a large part of the amphibious forces were redeployed in Great Britain (and returned in August for Dragoon).

D-Day in brief

I will not dwelve in detail in the operation, which is well-known, covered by hundreds of books, movies and documentaries. Suffice to say that the allies, months before, decided Normandy was a better spot, since it was unexpected, and surprise was ensured by Operation Fortitude, part of the larger Operation Bodyguard, an elaborate plan to keep believing the Germans D-Day would take place in the Pas de Calais (the nearest point to British shores). The massive fleet created, in addition to the airfields, storage depots, training areas throughout the British countryside, ensured US troops would be trained enough and supplied enough during the early phase.

After all, the allies had to breech the bespoke atlantic wall, and commando operations took place: US, like the Rangers at pointe du Hoc, British, No. 47 (Royal Marine) Lovat’s Commando (Operation Neptune) at Asnelles, even Kieffer’s Free French at Ouistreham. It was preceded by night airborne assaults, mostly to secure strategic bridges, securing a perimeter which would give some provisional immunity to the beachhead, prevent reinforcements and communication (in part also assured by the French resistance).

Preparations

Training exercises for the landings, which were complex because quite large, needed to land sufficient forces to deal with any panzerdivsion counterattack withing 72h, and coming from many poorts along the coast, over a much larger distance, down to Normandy. This process started as early as July 1943. The town of Slapton in Devon was evacuated by December and used as a playground for the invasion forces, using various landing craft testing ways to deal with beach obstacles.

Even this training phase went with tragedies, like a friendly fire incident on 27 April 1944 costing 450 deaths and the following day, LSTs with 749 American soldiers sank by German E-Boats in a sector presumably “safe”, made by Force “U” during Exercise Tiger.

Other large rehearsals took place at the Combined Training Centre in Inveraray, Scotland, far from German actions, in whch took place already command training. Other naval exercises took place in Northern Ireland and the medical teams in London. Paratroopers made notably a large demonstration drop on 23 March 1944, observed by the allied top brass.

Sherman DD (Duplex Drive); One aspect which doomed that solution was the bad weather on the 6 June. The waves just went above the skirts, flooding the tank. Most of the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions’s Sherman 32 DDs sank: For the first 27, all but two made it to the beaches. Seeing this, the remaining DDs of the 743th were landed conventionally on the beach later, at Utah.

Sherman DWG (semi-amphibious).

Mullberries, “funnies” or DD tanks are interesting subjects in themselves but a bit off-topic there, they will be treated by themselves in standalone posts.

Order of battle, naval forces, Operation Neptune

The landings were to take place at Utah, Omaha (US sector) to the west, including the cotentin peninsula, and Gold, Juno and Sword, British sector, east of the seine river estuary. Key ports here, Cherbourg and Le Havre, has been turned into fortresses and it would take almost until the end of the war for them to fall, in the hands of French partisans. They were simply bypassed.

Operation Neptune was the naval part of the operation.

It has three goals:

-Prepare the landings by preparatory artillery fire to neutralize the atlantic wall (in complement to previous aerial bombardments and commandos)

-Secure the flanks of the invasion forces (notably against U-Boats, and E-Boats)

-Provide cover during and after the landing, by on-demand artillery support inland.

This was was distinct from the assault transports action and numerous landing ships and landing crafts deployed that day and the next.

Since the Royal Navy provided the bulk of naval support, the operation was placed under Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay.

It was split into the Western Naval Task Force (Admiral Alan G Kirk, USN) and Eastern Naval Task Force (Admiral Sir Philip Vian), British/Canadian sectors.

The WNTF brough the First Army (Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, split between the VII Corps (Utah) and V Corps (Omaha). The British (Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s Second Army XXX Corps). All ground forces were under the overall command of Montgomery, and air command to Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory. The First Canadian Army also included units from Poland, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

In all, 5,000 landing and assault craft departed for the operation, covered by 289 escort vessels (from aicraft carriers, and battleships to destroyer escorts, corvettes and frigates) plus 277 minesweepers which secured the advanced and flanks. It was feared notably R-Boote (German coastal minesweepers) would spread deriving minefields with magnetic mines. In the end, nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel for the first day adn second, 875,000 men disembarking by the end of June. There were enough landing ships and crafts for the army itself, but to establish a steady supply, artificial harbors were needed.

Sherman tanks landing from an LCT in June 1944

Exploitation

The exploitation afterwards needed another operation in itself, before any port could be secured (previously North african ports and Italian ones were captured): The Artificial ports (Mullberries) at St Laurent s/mer (Omaha Beach) and Arromanches (Gold, british sector) would do the trick. The British came out with several ideas of their own to breach the defenses and minefields on the beaches, or bring support to the troops. The famous “hobarth’s funnies”. The exploitation phase soon ran into another unexpected obstacle, the Normandy’s bocage (hedgerows), wich favoured the defenders, at least until Operation Cobra unlocked the front in july 1944, followed by the falaise pocket push in August. From these two artificial ports, a supply line fed the advancing allied forces eastwards, until they reached the German border: The famous red ball.

Lessons from the landings

The final operation was to take 24h for its realization itself, starting with paratroopers taking off at the preceding noon, and transports in the furthermost ports departing, 24h before arriving on the beaches. So only bad weather, more of less expected in the channel in early June, had the entire operation cancelled by C-in-C Dwight D. Eisenhower, based on weather predictions on the 5th, and took place eventually due to latter unfavourable tide, -still in less ideal conditions- on the 6th.

Adverse conditions

As a result, troops became seasick, paradroppings were scaterred (hampered by low visibility), DD tanks almost all sank, and accidents were many, including troops falling from ladder ropes along the transport’s flanks when transiting into their landing crafts. Some of these were also lost due to collisions between them, and with beach obstacles.

Near disaster at Omaha

It was discovered at Omaha that the German defenses were pretty puch intact, since the blockhaus has not been hit by a scaterred bombing carpet. In addition, the landing chief officers competely missed his sector, and troops from the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions faced the entire 352nd Infantry Division, rater than the expected single regiment. Strong currents and lack of clear recognition marks along the coast also aggravated this.

Intense mortar and machine-gun fire decimated the troops even before they exited the landing crafts. Once their ramp was down, nothing stopped the bullets and troops jumped from the sides, sometimes drowning. For a refresher, see the opening scene of “saving private ryan”. Omaha for such reasons almost turned to a disaster, not receiving also its tank support designed to deal with such leftover fortifications. Most of these were the aforementioned DDs, now down to the bottom. A destroyer eventually, went to beach itself to provide the closest fire support possible, helping to solve the deadlock. Some battleships later even filled part of their hulls to rest at an angle, artificially raising their artillery range, covering more distance inland. This technique was already used by the Russians in the Baltic during WW1 (battle of moon island).

At Utah, troops had better success, notably because tanks were landed in a second wave and played a great role during the busting of theses defenses. The abruptly high sand dunes at Utah and even more at Omaha were dealt for by the infantry, using notably the so-called “bangalore torpedo”, but at a high cost. Although still not a “walk in the park”, British landings were comparatively easier. At the end of the day, the beaches were all secured, and surprise worked well as expected. It was explained also by still largely unfinished preparations on the Atlantic wall, according to Rommel which supervised the operations, about 18% ready on D-Day, while the allies had a total superiority in the air.

German response

The Luftwaffe here proved no threat, but a single strafing from two isolated Messerschmitt fighters on D-Day itself. On the naval side, there were peace-meal attack by E-Boats, U-Boats and midget submarines that were expected, and dealt for. Indeed the Kriegsmarine still had on Cherbourg, Le Havre, Ouistreham, Port-en-Bessin, Grandcamp-Maisy and the Channel Islands some 163 Raumboote (R-Boote), 57 Vorpostenboote (V-Boote or patrol crafts), 42 artillery barges (Artillerie-Träger), 34 S-Boote and 5 Torpedoboote.

A counteroffensive was mounted with the 8th fleet of destroyers coming from the Gironde estuary down south, led by Admiral Krancke (Marinegruppe West). These were Type 36A destroyers, making their way to Brest, and in place for their raid during the night (see later). Also, the 6. Artillerieträger-Flottille was deployed but quickly silenced by the allied armada’s fire. From Le Havre and Cherbourg, the 4th and 5th TB flotilla and 15th patrol fleet were deployed. The former launched their torpedoes and folded up quickly, under heavy fire. They nevertheless sank off Ouistreham the Norwegian destroyer Svenner.

The night raid by the 8th DD flotilla was a failure. Called the Ushant raid, it took place in the night of 8-9 june, simply because of intercepted communications (Enigma), as eight allied destroyers waited for the four Germans.

German Coastal artillery also that day opened fire, some still intact after the deluge of the allied armada in the opening hours of the invasion. Those of Cotentin Peninsula (Azeville, Crisbecq) made a direct hit on American warships but for the most they fell under allied control rapidly during the day. The battery at Longues-sur-Mer was active for the longest, until captured the 7th by the British. Afterwards, various field artillery positions ran fire on the beaches during the 7th, 8th, even 9th until captured (like the one at Brecourt Manor by the 101th AB). This was the consolidation phase of the beach heads.

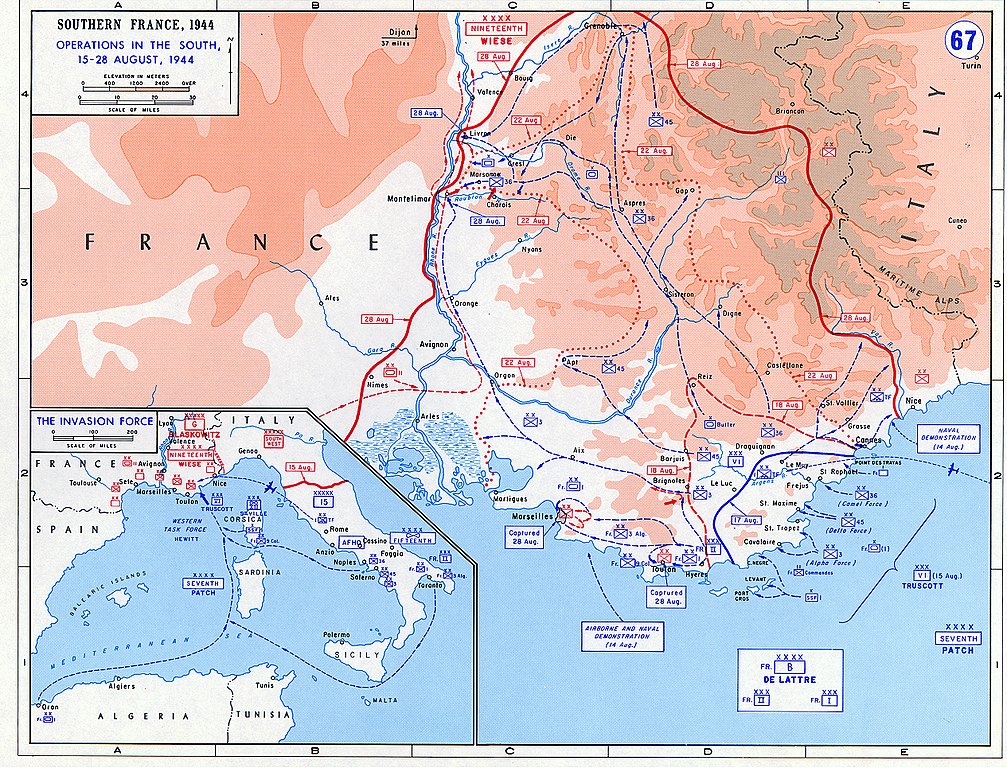

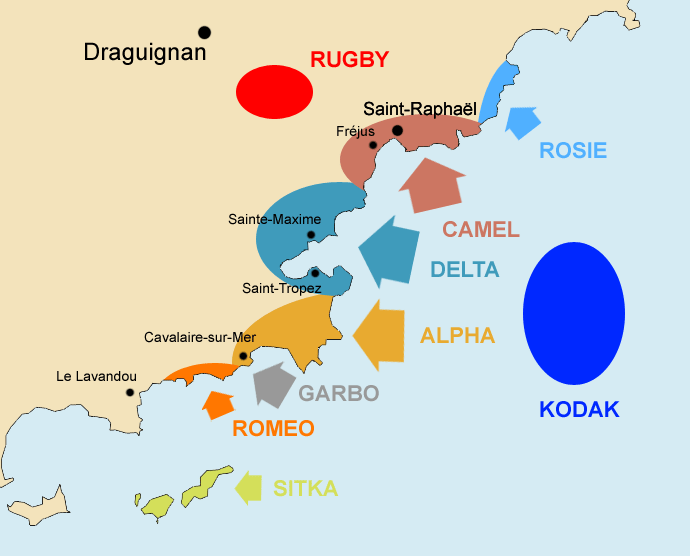

Operation Dragoon – 15 August 1944 – Southern France

Operation Dragoon was the last US-led landing in Europe. Afterwards, amphibious operations mostly concerned river-corssing operations, made with small boats and amphibious trucks (DUKW) and tracked LVTs. Dragoon was smaller in scale compared to Overlord, and certainly the “forgotten landing” in the sense it was completely overshadowed over time, almost brushed aside. This was due to the fact it seemed less important in the eyes of the general public not being the first landing in France, closer to Germany, and meeting far less opposition or long, arduous stand in the Bocage. Allied forces in the south of France progressed even more rapidly than planned, leading to the Alsace-Lorraine campaign in the autumn and winter.

Initially, it was planned to take place at the same time as Overlord, to take retreating German forces in a pincer, and it was called for this reason Operation Anvil. However, Churchill vehemently opposed it, as drawing out resources much needed in Italy. He wanted in place a push eastwards, to the Balkans, in order to severe the fuel supplies of the German army and ultimately link up with Soviet forces of the southern front. However resources were later concentrated to D-Day and lacked for Anvil, which was postponed until 14 July, and then 1st August, renamed Dragoon. De Gaulle also strongly advocated for a landing in Souther France in which the 1st Free French Army would take a great part, contrary to Overlord, where the French presence was limited to a single commando unit. Many amphibious vessels, including the numerous LSTs were re-routed to the Mediterranean once the artificial ports in Normandy were working properly.

Details of operation Dragoon. One deciding factor was to take the French ports of Marseille and Toulon, considered essential to supply the growing Allied forces in France.

Arguably it was also almost a perfect landing, a “textbook” operation with many refined techniques that were brought to bear in August. It was also helped by several factors:

-German defense were not bolstered like the Atlantic wall. They relied on older existing fortifications, to which were added a few blockhaus along the coast.

-The German forces settled there were less numerous and equipped to face the allied invasion.

-There was very limited Luftwaffe support.

-Pre-landing preparations has been done well

-Weather conditions were pristine

Opposing Forces

The 151,000 personnel that landed in the first waves lost about 7,300 men after the landing (Just 95 killed and 385 wounded initially) and, meeting a force about their size, 85,000 strong, albeit largely spread on 90 km along the coast.

It was Heeresgruppe G, comprising only the 19th Army (Friedrich Wiese), gradually stripped in 1944 of nearly all their valuable units and equipment, especially to bolster the defense in Normandy. Most of its forced were far north when Dragoon was launched, the remaining 11 divisions were well understrength. There was only the 11th panzer division left to deal with US and Free French armor, but it had just a single panzer battalion, the other being in Normandy. The Luftwaffe on paper had 200 aircraft in the south of france, but few fighters; Most were second-rate bombers and transport planes. The Kriegsmarine had about 45 small ships, mostly captured ex-French vessels, and played a negligible role. In Toulon however, there were three U-Boats and several torpedo boats (see below).

On the allied army side, three-division led by Major General Lucian Truscott (VIth army, General Patch) had to secure a bridgehead on the first day. Their flanks were protected by French, American and Canadian commando units. 50,000–60,000 troops and 6,500 vehicles were planned to be landed in several waves. Airborne landings would on Draguignan and Le Muy were to secure communication hubs in order to prevent German counterattacks. The exploitation phase was a push northwards along the Rhône, with the objevctives of taking Lyon and Dijon and then link with the western divisions from Normandy. French Army B (Jean de Lattre de Tassigny) was to take the French ports of Toulon and Marseille to ensure future supplies.

USS Nevada in 1944

On the allied naval side, the Western Naval Task Force (Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, USN) was to cover the amphibious fleet carrying Dragoon Force to the beaches. It comprised the battleships USS Nevada, Texas, and Arkansas, British HMS Ramillies, French Lorraine, 20 cruisers and the air cover provided by 9 escort carriers (Task Force 88). There was a long range cover, 3470 allied planes in majority based in Corsica and Sardinia. The French resistance (FFI) also played their role, helped by the OSS, by sabotaging bridges and communication lines, seizing important traffic hubs and directly attacking isolated German forces.

German naval response

It was two-fold: From the surface fleet, from Toulon, and the coastal fortfications. The Kriegsmarine could send 25 surface ships, a few mostly E-Boats and many patrol crafts, reinforce by the 10th Torpedoboat Flotilla from Genoa, counting four torpedoboats fit for service, but it never sailed. Only two actions against the invasion force were made: On 15 August off Port-Cros, USS Somers was attacked by two German warships and sank them by gunfire. On 17 August off La Ciotat, two others met PT boats and gunboats and a destroyer escort. There was a hour-long gun battle in which the two German vessels were sunk. The U-boat force in Toulon had been reduced to eight units, five being destroyed after an allied air raid in the port. During the night of 17 August, a single U-Boat sailed out to attack, but ran aground close to the harbor was scuttled. The other two were just scuttled to avoid capture when the harbour was taken. The best success was from the Luftwaffe in fact, the day of the landing, when a Dornier 217 (KG 100) launched a rocket-boosted Henschel Hs 293 which sank USS LST-282, the only real loss of the allied amphibious fleet.

LST-282, off St Raphael. Hit by a German glide bomb, it sank and burned seriously, being a complete loss (navsource.org).

The other threat, really serious however, was from the naval fortifications in German hands.

Back in 1941-42, to please their German masters, the Vichy regime accepted to bolster the fortifications along the Cote D’Azur: These were 75 coastal guns of heavy and medium caliber placed in various positions along the coast, while Toulon itself was protected by a large fortification complex, housing heavy gun artillery batteries in turrets. From November 1942, the Germans improved this, repairing and modernizing all positions and adding more guns taken from the scuttled French fleet, notably the 340 millimetres (13 in) from the battleship Provence. But since they pointed at sea, they never served as no allied ship approached the port. Instead, the city was taken by land, liberated by Free French forces.

The landing zones.

A textbook landing

Compared to D-Day, Dragoon almost looked like a walk in the park. This was due notably to the excellent preparations made before the landing itself: Preliminary commando operations were carried out on Hyères Islands, Port-Cros and Levant to silence Germans guns there. It was performed by the joint US-Canadian First Special Service Force, three regiments strong (Operation Sitka).

On 16 August however when darkness fell, camouflaged, previously unseen German guns at Cap Benat shelled troops landing in Port-Cros and were soon silenced by HMS Ramillies.

At Cap Nègre, westwards, Operation Romeo saw French commandos destroying German artillery positions during the night preceding the landing, helped by diversionary flank landings by other commandos. Operation Span was a deception plan to confuse German defenders, with fake landings and paratroopers, which also helped the real landing.

But the same night, special forces were also landed to the invasion beaches, spotting all obstacles and noting the configuration of the place, before reporting to the HQ. They learned that these beaches had been heavily mined, so at noon, the LCIs advanced forward of the first wave of landing craft, and fired a barrage of rockets to explode these land mines. All in all, the whole operation was overwhelmingly successful, swift, with little opposition and light casualties in contrast to Overlord.

The exploitation, although made somewhat difficult by the hilly terrain, was also far quicker than expected: After the Battle at Montélimar which saw the remainder of German forces, until then in orderly retreat, making a last stand, Taskforce Butler on 21-26 august was now only stopped by the lack of supplies. Remaining forces were hunted down by the VI Corps, flanked by the French II Corps until Dijon fell in early September. Link was made with Patton’s Third Army on 10 September, but by then German defense became way stronger than expected, leading to the battle of Colmar.

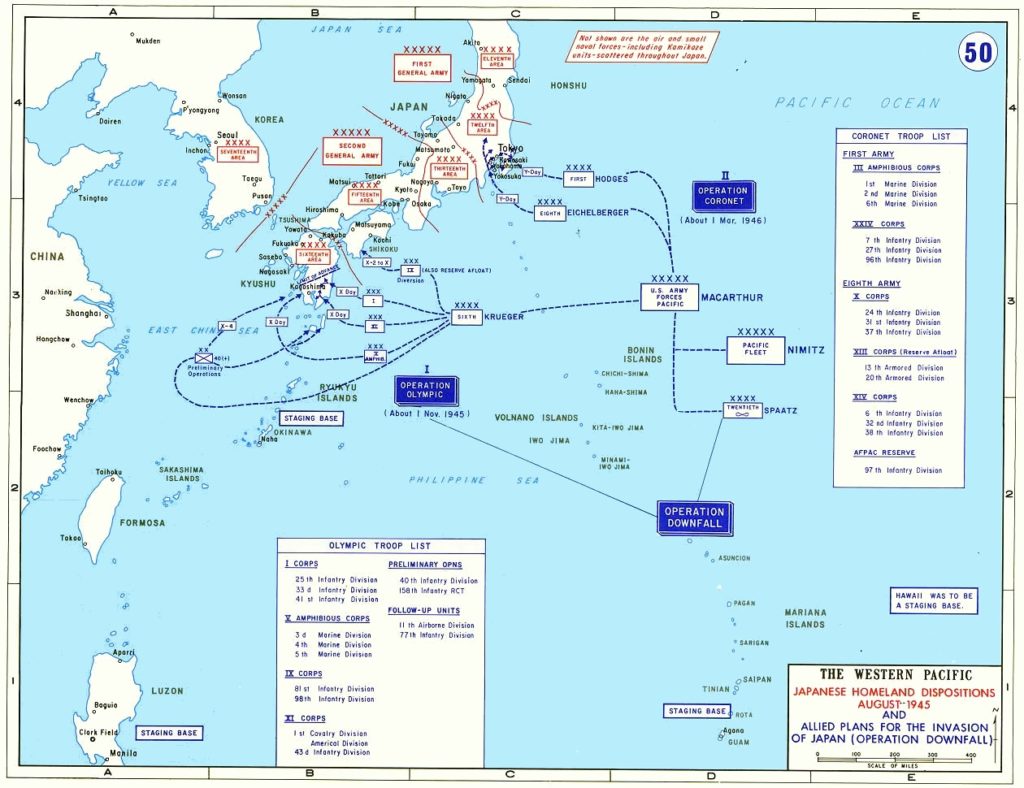

The largest amphibious operation that never took place: Operation Downfall (1 November 1945/March 1946)

A bit off-topic as this one is related to the pacific campaign, Operation Downfall was to be the largest amphibious operation in history. By its scale and the number of nations involved, with all the might of the allied armies reuinted from the European Front, it was to led to the conquest of the Japanese home islands, and in particular Tokyo, forcing the Japanese government to capitulate. As it progressed, the operation known as Downfall comprised two main landings, called Operation Olympic, and Coronet.

However with a twist of history, the atomic program (Operation Manhattan), at first aimed at catching up with nazi germany’s own program was re-purposed as the ultimate threat to Japan. A bomber for the recently taken island of Tinian, a B-29 bomber called “Enola Gay”, dropped the first workable A-Bomb called “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, 6 August 1945. The event indeed triggered reactions withing the government but the full scope of the event was not yet fully known. Because of this, a second bombing, by “Boxcar” dropping “tall boy” on 9 August 1945 ensured it was not taken as a random catastrophe. At the same time took place the invasion of Manchuria by Soviet Forces, steamrolling any opposition and putting an end to the Japanese occupation of both China and Korea. The rift between the civilian faction (and the Emperor) and the Military junta eventually led to a resignment and open peace negociations.

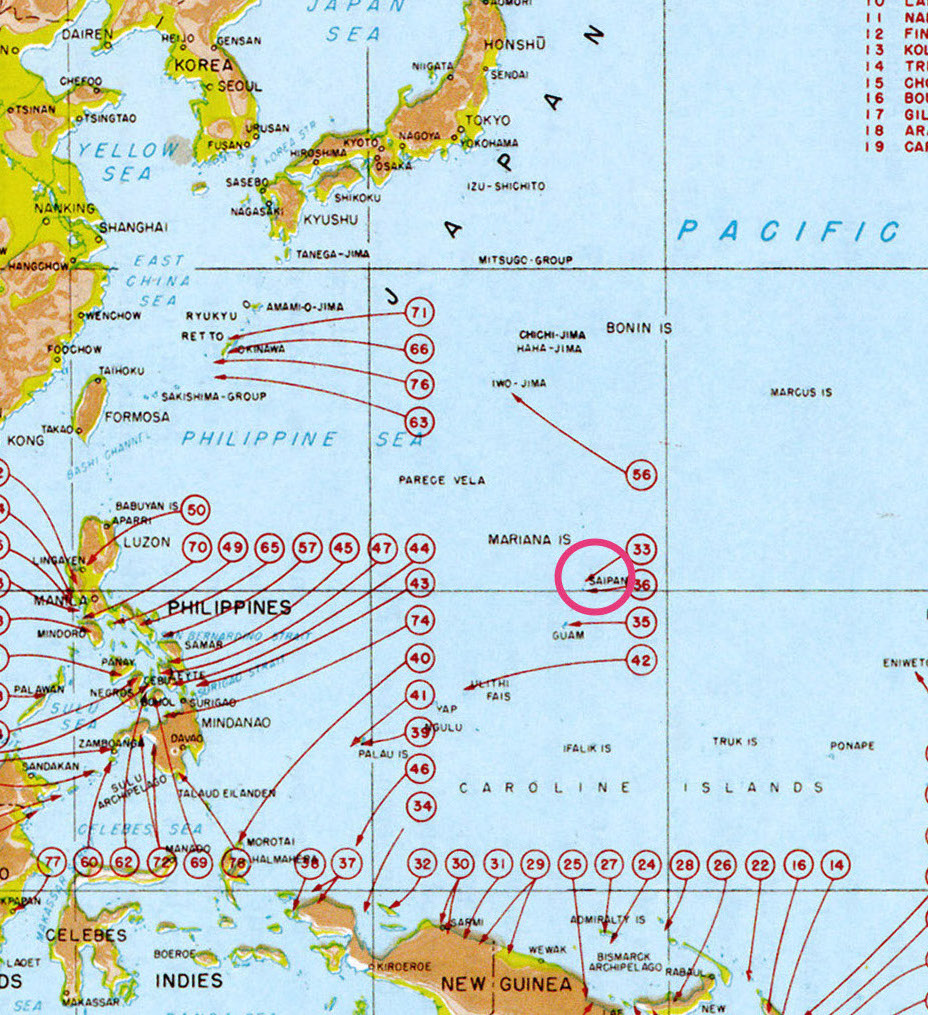

However, since a year, the allied HQ knew that the logical end to the island hopping campaign progressing in the Marianna-Palau and towards Iwo Jima would be the proper invasion of the home island chain. Not only Kyushu in the south, a logical step after Okinawa, but the main islands as well. The reason of this massive approach was to avoid a slow progression from the south island much alike in Italy. Like there, analysts predicted the mountainous terrain, combined with the fierce resistance shown at Tarawa and later at Peleliu, would cost US and allied forces dearly.

The forces engaged here were ust mind-boggling. On the allied side, it was expected to commit not only the USMC, which perhaps could grow to 15,000 at that time, but the bulk of the US Army as well. For the invasion of Kyushu alone, it was estimated 14 divisions were necessary. For the Downfall as a whole, statisticians estimated it would require more than 30 divisions for a successful invasion. It was estimated the help of Soviet Forces would be needed for a diversion assault on the northern, coast and Hokkaido, but at Okinawa, 1,300 Western Allied ships deployed during the Battle of Okinawa until June 1945 was relentlessely attacked by Kamiakaze, leaving 368 ships badly damaged, and 28 sunk, including 12 destroyers. In the Pacific the Soviets could only muster some 400 ships at best, not fit for amphibious operations.

So Downfall would needed more time for these forces to be mustered.

On the Japanese side, it as estimated the home island could musted all lical garrisons, so 4,335,500 strong, combining also all special units of the IJA and IJN. More so, 31,550,000 civilian conscripts, the tipping point a fanatically hostile population, has been enlisted and were trained on a regular basis since early 1945 to wield simple weapons such as bamboo spears. In addition the Japanese still kept the bulk of their recent tanks fresh from the factory on the home island for the expected assault. It was still a pinprick compared to allied armour, but these late Japanese tanks were certainly better than the old light models encountered during the island campaign, and a total of about 5,000 were available.

In the end, the common figure given by analysts was a stream of loss replacements of about 100,000 monthly. This figure looked unacceptable by President Truman, now in office, and pressed for the use of the atomic bomb, which did not made the unanimity either and remained controversial to this day. Some staff members included Curtiss LeMay estimated conventional bombings would have the same effect on the long run, making the landing operation superfluitous, but for occupation only.

Read more/Src

Links

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_amphibious_assault_operations

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_United_States_Marine_Corps

//www.britannica.com/topic/Mulberry-artificial-harbours-World-War-II

//www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-north-africa-campaign/operation-torch/allied-ships.html

//ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=100

//www.combinedops.com/Torch.htm

Color photo collections:

//metro.co.uk/2019/06/05/d-day-colour-dramatic-pictures-altered-make-horrors-war-even-bleak-9822050/

//www.buzzfeednews.com/article/gabrielsanchez/22-remarkable-color-pictures-from-the-battlefields-of-d-day

//www.defense.gov/Explore/Features/story/Article/1947561/wwii-operation-forager-provided-key-warfighting-lessons/

Books

Alexander, Joseph H., and Merrill L. Bartlett. Sea Soldiers in the Cold War: Amphibious Warfare, 1945-1991 (1994)

Bartlett, Merrill L. Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare (1993)

Dwyer, John B. Commandos From The Sea: The History Of Amphibious Special Warfare In World War II And The Korean War (1998)

Ireland, Bernard. The World Encyclopedia of Amphibious Warfare Vessels: An illustrated history of modern amphibious warfare (2011)

Isely, Jeter A., Philip A. Crowl. The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War Its Theory and Its Practice in the Pacific (1951)

Millett, Allan R. Semper Fidelis: History of the United States Marine Corps (2nd ed. 1991)

Moore, Richard S. “Ideas and Direction: Building Amphibious Doctrine,” Marine Corps Gazette (1982)

Reber, John J. “Pete Ellis: Amphibious Warfare Prophet,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (1977)

Venzon, Anne Cipriano. From Whaleboats to Amphibious Warfare: Lt. Gen. “Howling Mad” Smith and the U.S. Marine Corps

US World War II Amphibious Tactics: Army & Marine Corps, Pacific Theater (Elite Book 117), Gordon L. Rottman, Peter Dennis

US World War II Amphibious Tactics: Mediterranean & European Theaters (Elite Book 144)

World War II River Assault Tactics (Elite Book 195) Gordon L. Rottman, Peter Dennis

Videos

Peleliu

Tarawa

Operation Overlord

This is part one of a five part documentary series highlighting the development of the Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) and its use in amphibious operations in WWII.

On the LVTs and their use

More: //youtu.be/OyArvXFiawk

USMC amphibious Ops

US WW2 Amphibious Operations (Pacific)

A map overview of the Island hopping campaign, second phase, 1943-45

Operation Watchtower — 7 August 1942

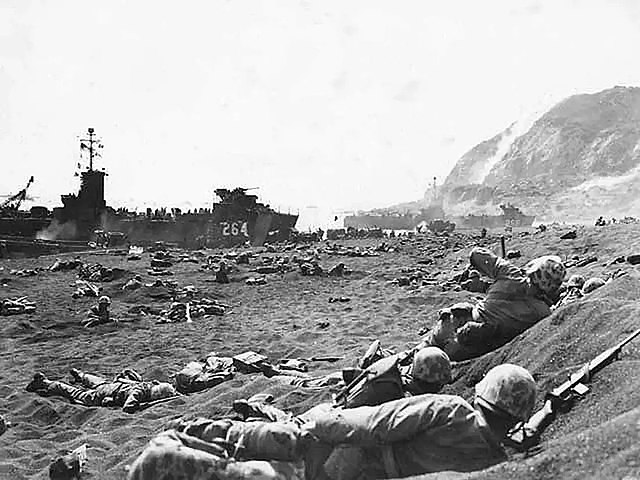

U.S. Marines lands from LCP(L)s onto Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942. Note these are essentially British crafts in US service.

This was the first large scale all-US operation was the start of the long campaign of Guadalcanal. To put things in perspective, US Force in the West only invaded North Africa in November that year, so two months later. So this was the very first active deployment of US infantry and armour anywhere on enemy soil, apart smaller anecdotal actions.

Bad weather favored the initial plan, and the allied expeditionary force landed by night on the beaches, on 6-7 August. The “Midnight Raid on Guadalcanal” gave the USMC a solid footing. Several waves after infantry was there, small crafts started to ferry supplies and armor. Japanese air patrols from Tulagi completely missed Allied ships due to severe storms and a crowded sky. The landing force split into two groups, one assaulting Guadalcanal, and the other Tulagi, Florida, and other islands while the fleet bombarded the invasion beaches. The present U.S. carrier aircraft hammered positions on the nearby island, destroying 15 Japanese seaplanes at Tulagi. Gavutu and Tanambogo were invaded by 3,000 U.S. Marines (Brigadier General William Rupertus). The IJN naval/seaplane bases on the three islands fought hard but were taken. Tulagi fell on 8 August, Gavutu and Tanambogo the following day.

On Guadalcanal resistance was low. On 7 August, C-in-C General Vandegrift announced his 11,000 U.S. Marines were safely ashore between Koli and Lunga Point. They secured the airfield on 8 August afternoon. IJN Naval construction units and combat troops (Captain Kanae Monzen) panicked, had previously abandoned the airfield area. They took refuge at the Matanikau River and Point Cruz.

Nevertheless, the IJA (Sadayoshi Yamada) attacked several times. They sank the transport USS George F. Elliott and badly damaged the destroyer USS Jarvis but lost 36 aircraft.

Admiral Fletcher weary of loosing his carrier fighter strength and worried about his fuel levels withdrew from the Solomon Islands area on the evening of 8 August. Turner also decided to withdraw his ships whereas only half of the supplies and heavy equipment were ashore, but he planned to came back an unload supplies during the night of 8-9 August.

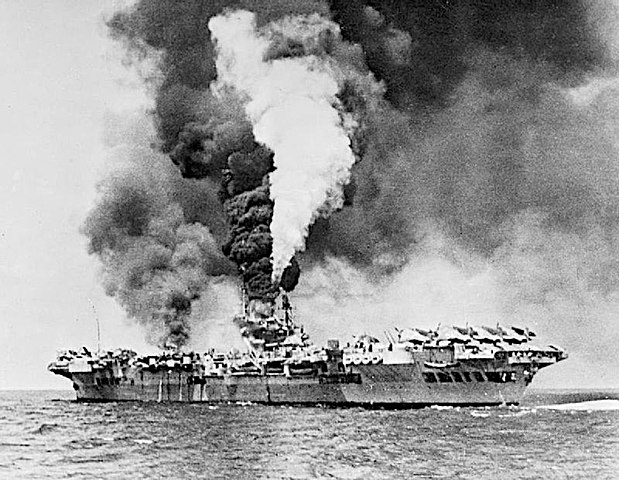

The loss of USS Wasp, 15 September.

Something however marred these plans: The Battle of Savo Island.

As a result, most of the escort was destroyed and Turner never returned, leaving the Marines to fend for themselves isolated for weeks, with very limited equipment. The Battle of the Eastern Solomons on 25 August allowed however small air-dropped supplies at Henderson field. It was done by USS Enterprise’s aircraft and established a precedent. Japanese daylight supply runs became impossible, forcing night supply runs, notably the famous “Tokyo night express”. Other US reinforcements took place in 14 and 18 September. Later took place the Battle of Cape Esperance (11 October), enabling another US reinforcement, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October, a tactical victory for the Japanese (Hornet sunk, Enterprise badly damaged). Mostly land actions and local landings led to the Matanikau Offensive, Koli Point action, and Carlson’s patrol, and this culminated in the epic Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (12-15 November), one of the rare capital ships duels of the Pacific campaign. It was followed by the Battle of Tassafaronga (30 November) and tactical Japanese victory but to the price of no reinforcements. This was the final straw for the Japanese, which started to withdraw (Operation Ke). This was followed by US exploitation, the Battle of Mount Austen, Galloping Horse and Sea Horse, and the naval Battle of Rennell Island (29-30 January 1943) and final evacuation.

Carlson’s raiders coming ashore at Aola Bay on 4 November 1942. Note the LCVPs.

Battle of Goodenough Island – 22 October 1942

Also called Operation Drake, this early operation in the pacific was aimed at chasing off the Japanese garrison on the small island of Goodenough in Papua. The mostly Australian force (headed by US Marines commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Arnold, carried by USN ship) clashed with with a Japanese Kaigun Rikusentai (Special Naval Landing Force). The latter were stranded here since the Battle of Milne Bay (August 1942). This was prior to the Buna campaign. The Japanese eventually withdrew to Fergusson Island on 27 October. The island was later developed into a major Allied base.

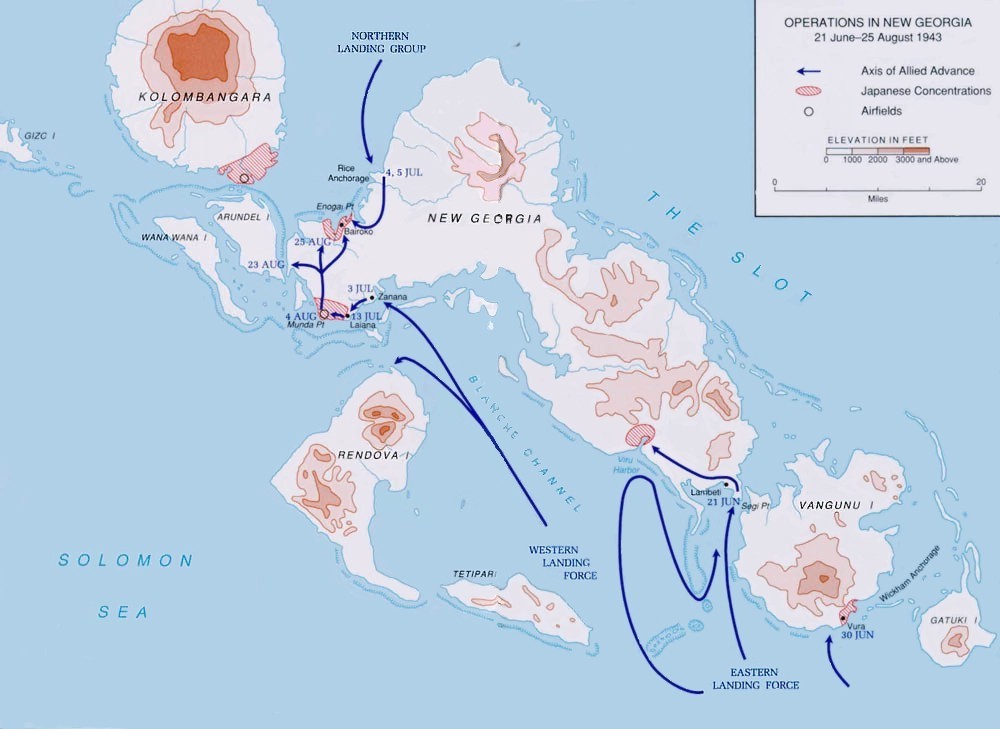

Operation Cleanslate – 21 February 1943

The invasion of New Georgia was part of Operation Cartwheel. The Allied strategy in the South Pacific was to isolate Rabaul. The New Georgia group was located in the central Solomons. New Georgia island by itself was the linchpin of the area, but actions and landings took place in all the island chain. It started on 30 June 1943 with a landing in the Kula Gulf (north) and in the Munda area. Smaller diversion landings were made at Viru Harbor on the southern coast and Wickham Anchorage (in Vangunu Island) and Rendova, for support. All the supplies were brought there. In the north, Enogai and Bairoko were assaulted in turn in July 1943 and eventually the airfield on Munda Point was capture, enabling air cover over the whole region. By early August the main campaign was over.

However next came the landings on Arundel Island, in late August til early September. Japanese forces withdrew and those at Kolombangara were destroyed peacemeal or bypassed, as Marines landed at Vella Lavella from mid-August, reinforced later by New Zealand troops. It was all over on 7 October 1943 when Vella Lavella was secured. Naval and air actions comprised the battles of Kula Gulf, Kolombangara, Vella Gulf, Horaniu and Vella Lavella.

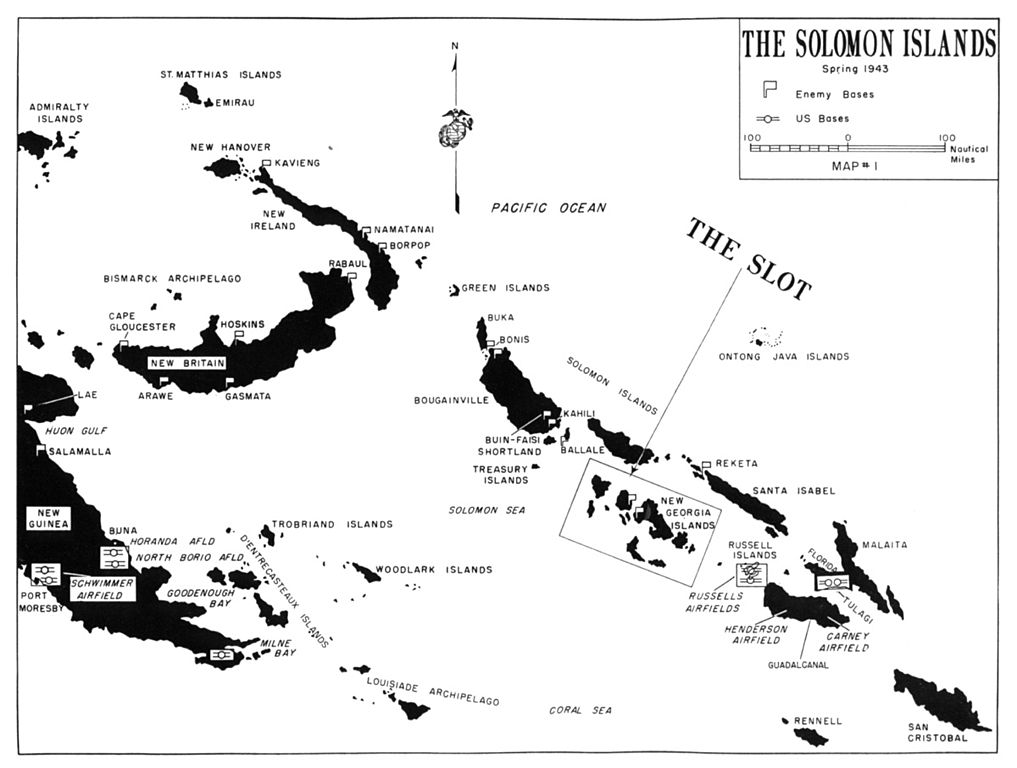

Operation Toenails — 30 June 1943

The invasion of New Georgia (30 June-5 August 1943), first major Allied offensive in the Solomon Islands after Guadalcanal. The Solomon Islands comprised two main chains of large islands separated by the ‘slot’ (late called “ironbottom sound” after all the naval engagements that happened there). The north-western sector comprised the group of Bougainville. The southern sector comprised New Georgia islands, Guadalcanal and San Cristobal. The first, the New Georgia group comprised in order, Vella Lavella, Kolombangara, New Georgia itself, Rendova and Vanguni. They were thmselves surrounded by smaller islands and islets. None were really explored or mapped, with primitive and isolated populations, with the whole era covered with thick jungle.

New Georgia was a juicy target, possessing a major base at Munda (western tip of New Georgia) with an existing airfield. A large Japanese base was installed at Vila (south-western shore), on Kolombangara. Destroyers and fast transports were ised for night supplies, the ‘Tokyo Express’. New Goergia defences were bolstered by Rear-Admiral Minoru Ota, with reinforts of the Navy’s Special Naval Landing Forces and in March-April, the IJA 38th and 51st Divisions.

By late May a South-East force was created with overall command on the Army and Navy. General Noboru Sasaki by then the commander of the 38th Division was in overall command. By late June he had around 11,000 men while the navy provided two units and 140mm 120mm and 80mm coastal guns. In the end main bases were located at Munda and Vila. A smaller force was located at Enogai (north coast of Munda) with naval guns. Garrisons were located at Rendova Island, Viru, and Vangunu. Most of the aviation was moved to Rabaul (66 bombers and 83 fighters) which on 30 June still had a small naval force with a single cruiser, 8 destroyers and 8 submarines.

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, Commander South Pacific Amphibious Forces

American preparations started when Guadalcanal was still not secured, as on the night of 4-5 January, Admiral Ainsworth’squadon shelled Munda. On 21 February, a first landing was made in the Russell Islands (Operation Cleanslate) and two support airfields constructed by the seabees. On 6 March, Rear Admiral A.S. Merrill shelled Vila and Munda and two Japanese destroyers were sunk (Naval battle of Kula Gulf, 6 March 1943). On 9 March Munda was systematically bombed and soon Kolombangara followed. For three month USN aviation bombed and strafed all targets of opportunity. On the night of 6-7 May interception of a Tokyo Express with mines in the Blackett Strait hit four Japanese destroyers, two lost. Admiral Ainsworth repeated that on 12-13 May, and shelled Munda and Vila.

Meanwhile the Japanese launched air raids in the invasion fleet around Guadalcanal, starting on 7 June. They lost 23 aircraft (for 9 Allied down), followed by two others, less successful. The 16 June raid grouped 120 aircraft, damaging two warships and a transport, but all but 20 returned safely, for 6 allied aircraft lost. Most of Rabaul air force was decimated.

Halsey meanwhile issued the general instructions for the invasion, setup on 3 June. Munda would be left alone at first, the Western Landing Force assaulting Rendova Island, and the smaller Eastern Landing Force invade Viru Harbour to captured the base Segu Plantation. The Seabees were charged to create an airfield and naval base here. The Northern Landing Group (Colonel Harry Liversedge) landed at Rice Anchorage on 5 July, capturing Enogai and Bairoko, the coastal gun battery and base. The US 43rd Infantry Division was supported by two battalions of US Marine Raiders, the 1st Commando Fiji Guerrillas, a field artillery battalion and the Marine Corps 9th Defence Battalion (Major-General John H. Hestor), covered by Vice Admiral A.W. Fitch and Rear Admiral R.K. Turner in overall command.

The assault on Makin (Sept. 1943)

Makin raid (August 1942):

On 17 August 1942, 211 Marines of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion (Colonel Evans Carlson, Captain James Roosevelt) landed on Makin, from two submarines: USS Nautilus and USS Argonaut. The small Japanese garrison was wiped out while installations were destroyed, for 21 lost, mostly dueing air attack. 9 were also captured, prisoners moved to Kwajalein and later beheaded. Instead of sewing confusion, the raid mostly alerted the Japanese on the important for the US of the Gilbert Islands and stepped up reinforcements and fortifications.

After Carlson’s raid, Makin received a company of the 5th Special Base Force (about 800 men) in August 1942. The seaplane base was further developed, while coastal defenses were beefed up. By July 1943 Makin seaplane base was now completed, large enough to serve a small squadron of heavy Kawanishi H8K “Emily” flying boat bombers. They were protected by a full squadron of Nakajima A6M2-N “Rufe” floatplane fighters, and Aichi E13A “Jake” reconnaissance seaplanes to organized daily long range search. IJN Chitose and 653rd Air Corps were also landed here to beef up the air defences.

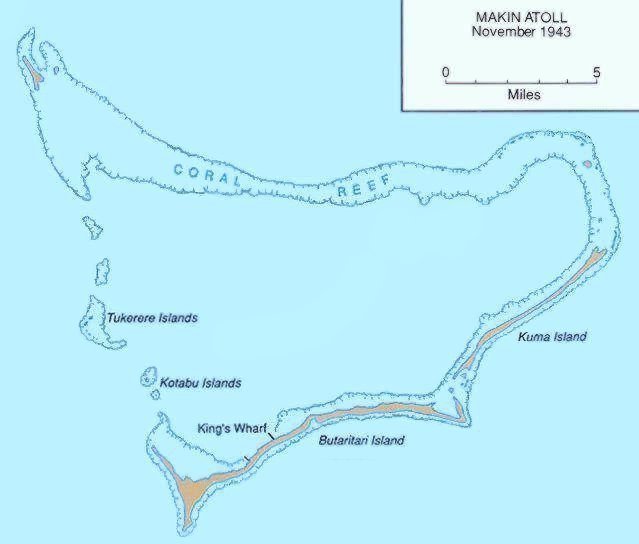

Makin attoll map

Planning: From Nauru to Makin

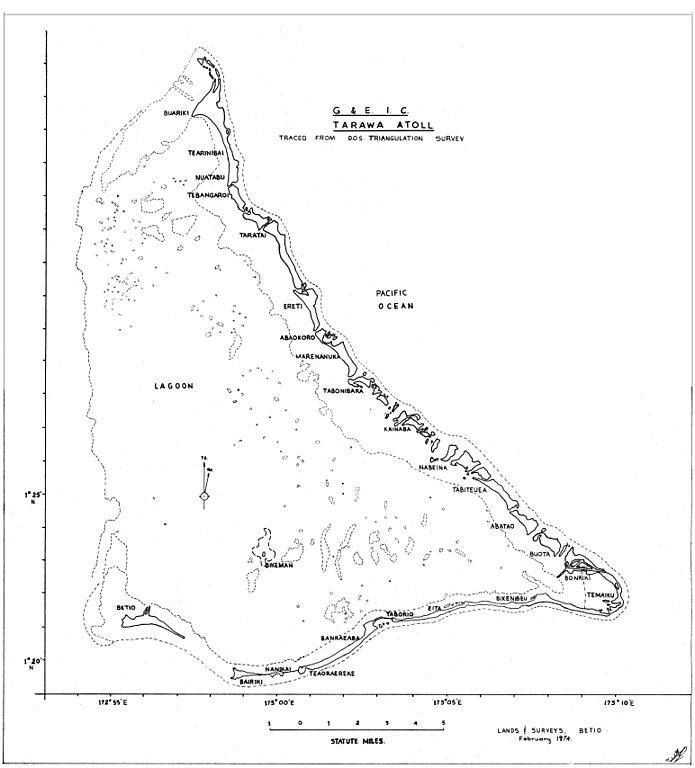

Meanwhile, the US Command prepared their operation: In June 1943, Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (CINCPAC), to submit his plan for the conquest of the Marshall Islands. He agreed with Ernest J. King (Chief of Naval Operations) that any plan to attack the Marshalls directly from Pearl Harbor would have required more men and ships. King and Nimitz wanted instead a step-by-step approach, via the Ellice and Gilbert Islands. The Gilberts were just 200 miles (320 km) of the Southern Marshalls, to were ideal to be converted bases for a support of B-24 bombers in Ellice Islands. In addition of long range support, long range reconnaissance would have been also required to assault the Gilberts. On 20 July 1943 Tarawa and Abemama atolls (Gilberts) and Nauru Island were targeted, under Operation Galvanic.

On 4 September, the U.S. 5th Fleet’s amphibious forces became the V Amphibious Corps (Major General Holland M. Smith), with two divisions: 2nd Marine (from New Zealand) and U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division (Hawaii). The latter was a former New York National Guard called into federal service in October 1940 and transferred to Hawaii training for a year and a half. Captain James Jones Commanded the Amphibious Reconnaissance Company. He made an initial periscope reconnaissance of the Gilberts from USS Nautilus, trying to observe the best beachheads and fortifications to draw a detailed plan of attack. The primary goal of the 27th (Operation Kourbash) was Nauru Island in August, but in September 1943 the lack of adequate support of simultaneous landings at Tarawa and Nauru, too far away, and transports, made Admiral Nimitz shifting changing it to Makin Atoll (northeast Gilberts). After their losses at Guadalcanal, the Japanese could not reinforce both islands, which received orders to fight to the last man.

The invasion

The USN invasion fleet was Task Force 52 (TF 52), Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner. The fleet left Pearl Harbor on 10 November 1943, and covered the landing force, Task Group 52.6, mainly the 27th Infantry Division transported by the APA USS Neville, Leonard Wood, Calvert, Pierce, and Alcyone, LSD USS Belle Grove, LSTs−31,−78,−179. Opposing them were Japanese forces divided between Makin’s Butaritari islet, in all 806 men (6th Special Naval Landing Force, 111th Pioneers, Fourth Fleet Construction Department and 3rd Special Base Force three Type 95 Ha-Go Light Tanks plus 108 aviation personnel without planes (Lt.j.g. Seizo Ishikawa).

Butaritari had fortificatins centered around the lagoon shore, near the seaplane base. The west and east tank barrier were 12 to 13 feet (4.0 m) wide, 15 feet (4.6 m) deep, protected by a single anti-tank gun in a concrete pillbox, six MG nests, 50 rifle pits. The east one was 14 feet (4.3 m) wide, 6 feet (1.8 m) deep, reinforced by log antitank barricades at its ends and protected by a double apron of barbed wire with intricated gun emplacements and rifle pits. Butaritari’s ocean side counted several 8-inch (203 mm) coastal defense guns and three 37 mm AT gun positions, 10 MGs nests, 85 rifle pits. Despite this, the Japanese were outnumbered and outgunned by a wide margin.

Air operations started first, on 13 November 1943, USAAF B-24 bombers (7th Air Force) taking off from the Ellice Islands and a wave of Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers and Grumman TBF Avengers from USS Liscome Bay, USS Coral Sea and USS Corregidor escorted by Wildcats. The landing took place after a preparation of artillery led by USS Minneapolis, at 08:30 on 20 November. There was a turret explosion on USS Mississippi, killing 43 sailors however. Red Beach was conquered first, after which the assault troops moved inland, on the ocean side, slowed down only by sniper fire and rough, cratered terrain and debris after the bombardment. The tank support (193rd Tank Battalion) on Red Beach was quickly bogged down (photo).

Next, landing craft approached Yellow Beach from the lagoon. In proximity, small-arms and MG fire started, but miscalculation of the lagoon’s depth and tide conspired to have their boats running aground, to they had to walk their way over final 250 yards (230 m), exposed in waist-deep water. Weapons became water-soaked, but mircuslously three men were killed. Meawnhile, the japanese as ordered retreated to their prepared final stand along the tank barriers inland.

The originaly plan was to lure out Japanese on Red Beach, allowing troops landing safely on Yellow Beach, taking them from the rear. But it did not worked and instead the 27th Division braced for hours of hard fighting, reducing all Japanese fortified strongpoints in turn. The small island also preluded safe tank tank support, as well as aerial and naval artillery support. After two days of dogged resistance, the Japanese were eliminated or captured and the island was fully secured after four days. The Makin operation showed coordinating actions of two separate landings were difficult if the defenders did not behaved as planned. Narrow beaches precluded also supply operations and became a severe handicap the second day.

The irony was most casualties came not from land operations, after all the 27th I.D. was way superior (66 KiA, 100 wounded), but the Navy: 697 dead. In addition to the turret accident on USS Mississippi, they all came from a single loss:

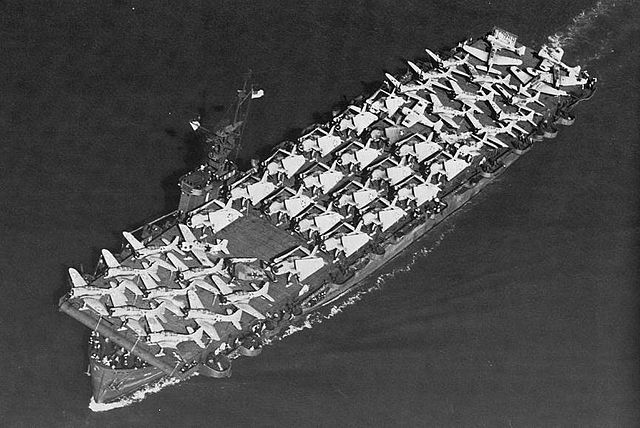

USS Liscome Bay (Casablaca class escort aircraft carrier). At dawn on 24 November, she was spotted and sunk by the Japanese submarine I-175, which came unnoticed just prior to the invasion off Makin. She sent a single torpedo to target, off a torpedo spread, but was a lucky hit for the Japanese as it detonated just outside the escort carrier aircraft, blewing up its bomb stockpile. The entire ship detonated, broke in two and sanl to the bottom in a short notice. Only 272 were rescued, 644 (including flagship admiral, TG commander Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix, Captain Irving Wiltsie, plus Pearl Harbor Navy Cross recipient Cook Third Class Dorie Miller). An investigation shown the destroyer screen (USS Hull and USS Franks) were not in place when this happened. The TG also was not zigzaging to make support operations easier.

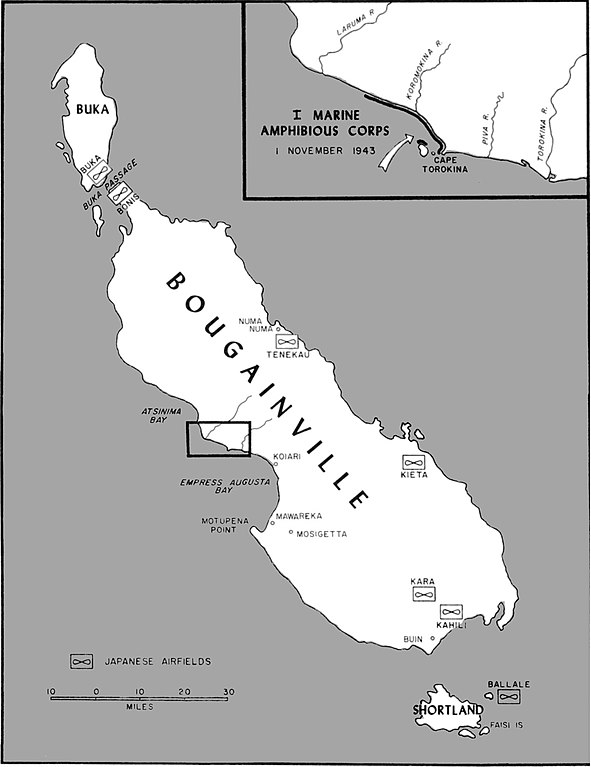

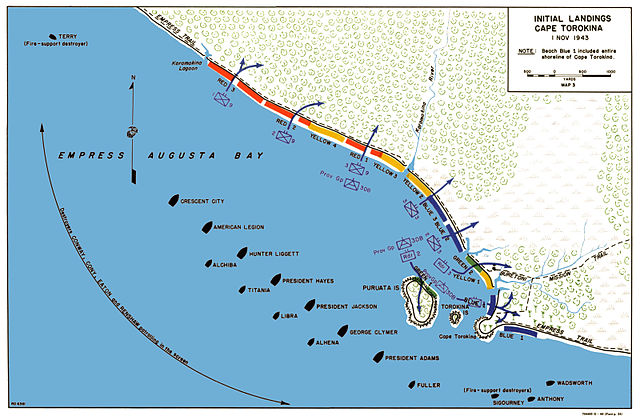

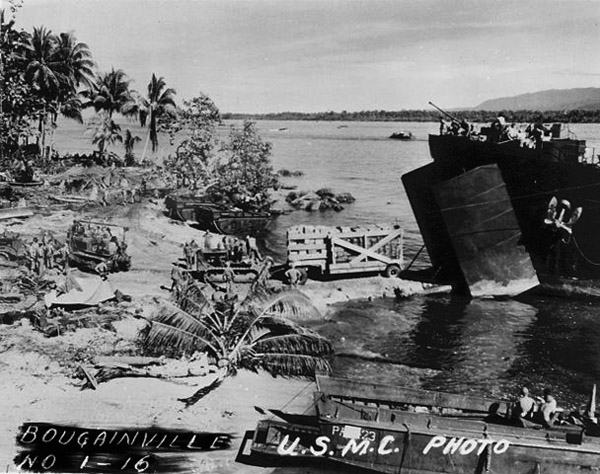

Operation Cherry Blossom – 1 November 1943 – Bougainville

These were the Landings at Cape Torokina. It took place at the start of the Bougainville campaign. Amphibious landings were carried out by elements of the United States Marine Corps in November 1943, on Bougainville Island. The grand strategy was to close on Rabaul (Operation Cartwheel). It came after the securing of Guadalcanal and the central Solomons. The plan was to establish several bases for power projection north, towards Rabaul.

Mnths before, the campaign of Bougainville seriously eroded Japanese airpower as we saw. On 1 November, a landing force (US 3rd Marine Division with smaller unit)s landed at Empress Augusta Bay, western shore of Bougainville. It met with only limited resistance. A Japanese air raid from Rabaul was vigorously fought off by US and New Zealand fighters. A perimeter was established the first dayn and the first wave unloaded all its supplies for immediate operations inland.

During the night of 1/2 November, a IJN naval force clashed with US cruisers and destroyers in what became the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay. The Japanese were defeated and returned to Rabaul. On 2 November a second wave from the transports secured more supplies. US troops ashore consolidated their beachhead, launching patrols in the surronding to locate enemy forces. The perimeter was secured meanshile with barb wire, minefields and machine gun emplacements, completed bt 3 November. Torokina Island was also occupied.