The largest Chilean cruiser of WW1: Esmeralda – The previous Cruiser Esmeralda, a 1884 British-built ship was soled to Japan on 5 february 1895 to Japan, and became the Izumi, participating to the Battle of Tushima. Before that, in 1891, the Chilean admiralty was embroiled into a vivid naval rivalry with Argentina, the first, eventually closed after difficult negociations in London. There was second one, the “battleship race” initiated by the Brazilians in 1907.

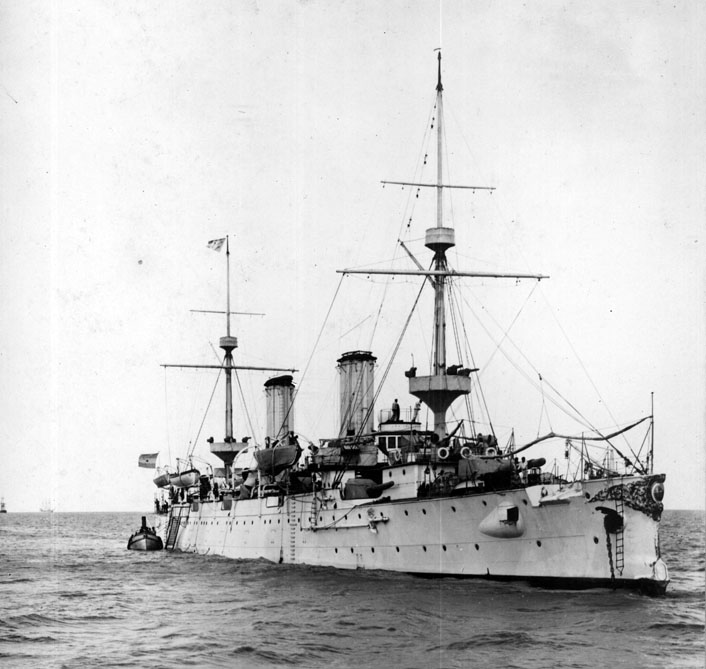

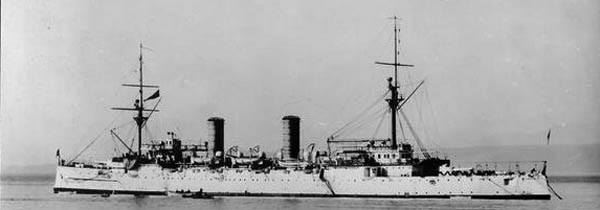

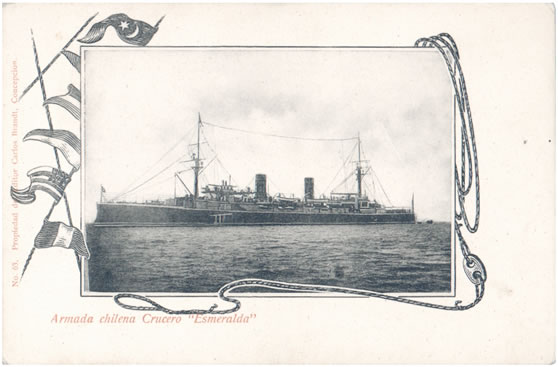

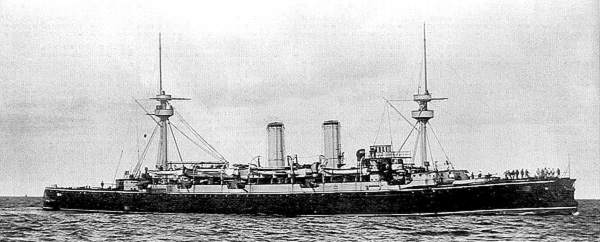

Esmeralda in 1896

Context: The Argentine-Chilean naval arms race

⚙ The naval Arms Race | |

Armada de Argentina Armada de Argentina |  Armada de Chile Armada de Chile |

| Libertad class (BB) 1887 Veinticinco de Mayo (PC) 1890 Nueve de Julio (PC) 1891 Buenos Aires (PC) 1894 Garibaldi (AC) 1895 San Martín (AC) 1896 Pueyrredón (AC) 1897 General Belgrano (AC) 1898 Rivadavia, Moreno* (AC) 1901 |

Capitán Prat (BB*) 1887 Presidente Errázuriz (PC) 1887 Presidente Pinto (PC) 1887 Blanco Encalada (PC) 1892 Esmeralda (AC) 1894 Ministro Zenteno (PC) 1894 O'Higgins (AC) 1896 Constitución class (BB) 1901 Chacabuco (PC) 1901 |

The first rivalry called the Argentine–Chilean naval arms race, started by the Chileans which purchased in 1887 three important vessels, the battleship Capitán Prat, and the Presidente Errázuriz and Presidente Pinto, protected cruisers made in France and UK respectively. The Argentinians ordered two armored ships, the Libertad and Independencia and the next years the armored cruiser Veinticinco de Mayo and Nueve de Julio. Chile replicated in 1892 with the Blanco Encalada, another protected cruiser, and in 1895, the Argentines ordered the Buenos Aires, followed by the Chileans with the cruisers Esmeralda and Ministro Zenteno, Argentina with the Garibaldi (From the prolific Italian class of the same name), Chile in 1896 came with the O’Higgins and the Argentines bought two more of the Garibaldi class, San martin and Pueyrredón, and hammered the point by also ordering again two more ships of the same type, the Rivadavia and Moreno. In 1901, Chile, not to be undone, ordered two battleships, second-class Swiftsure class pre-dreadnoughts, named Constitución and Libertad, and the protected cruiser Chacabuco. Argentina was to order two even more massive battleship to Ansaldo when negociations in Great Britain put this madness to an end. Indeed Chile was using an increasing part of its gold reserve to pay for them, risking the country’s future economy for what was considered, even inside the country as a naval folly.

Large model of the Esmeralda, kept in Swiss archives.

Increased tensions, near state of war and near-bankrupcy of both rivals pushed the UK, by then, THE respected superpower on the international stage, to start a negotiations process with Argentina and Chile, and argued for a resolution. This was largely due to their strong economic interests in the region, massive exports of raw materials (including Chilean nitrates for explosives and Argentine grain) and also its own trade goods to both countries, likely to be severely disrupted. Talks were at first held in Santiago de Chile, between the British ambassador and Argentine ambassador and local foreign minister and President, Germán Riesco.

Three Pacts were agreed, signed on 28 May 1902, ending the dispute. Naval armaments were limited, and both countries were forbidden of any new acquisitions for five years, unless giving an eighteen months advance notice. Those under construction were resold to the builder, UK. Chile’s battleships became the Swiftsure class, Japan obtained a cruiser, and the last two Garibaldi class armored cruisers were also resold to Japan (Kasuga class). The two planned Argentine Battleships were never ordered, Garibaldi, Pueyrredón and Capitán Prat were partially disarmed.

Name:

The Esmeralda could originate to pay homage to the Line Regiment 7 “Esmeralda” which in 1820 participated in the Pacific War, or to Vasco Da Gama’s Galleon during his second expeditions to the Indies in 1503. It was also given before 1894 to a 1753 and 1733 Spanish Frigates involved in the region, or the one captured by the Chileans in 1820 (likely) or the 1855 steam Corvette which participated in the second war of the Pacific. There was also a 1885 unprotected Cruiser of the same name. After the 1890s protected cruiser was discarded, the name was passed onto a 1946 frigate and the sailing schoolship of the Chilean Navy as of today. It is perhaps the most remembered ship name by the Chileans.

Genesis of the design

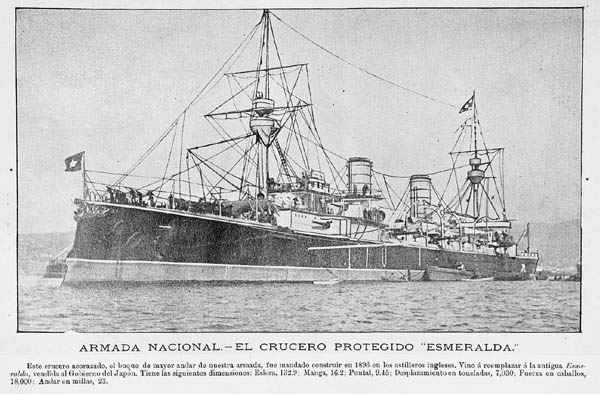

Both to replace the previous Esmeralda, sold to the IJN on 15 November 1894. The funds also helped purchasing a more modern ship. The Chilean Admiralty obtained a vote for the parliament to purchase another cruiser, despite the expensive Chilean Civil War (1891) and finally ordered her on 15 May 1895. Previously, they had seen the Argentinians purchase the ARA Buenos Aires on 27 November 1893, added to the earlier Veinticinco de Mayo and the more recent Nueve de Julio which entered service also in 1893. ARA Buenos Aires has been a Philip Watts design built on private funds by Armstrong-Elswick. Meanwhile the Blanco Encalada, purchased for £333.500, just entered service. She was closely based on the Japanese Yoshino cruiser design, with some alterations.

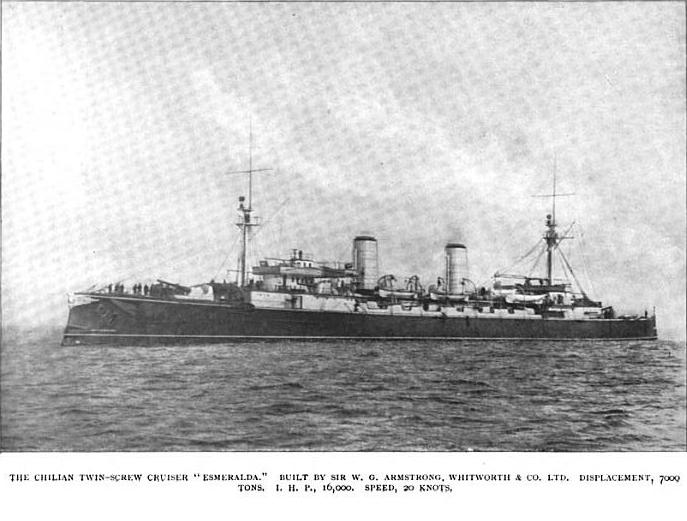

For the Esmeralda, the Chilean looked at both the Argentine designs and their own Encalada, a 4,420 tons ship. The Buenos Aires, purchased on stocks was displacing more, 4,788 long tons, and armed about the same, with two main guns (8 in) and ten secondaries (6 in) for the Chilean cruiser, whereas the Argentinian choose to mix four 6-in and six 4.7 in (119 mm)/45 QF guns instead. They loose in broadside weight but gained much in terms of rate of fire. Therefore for the next design, the Chileans choose an even heavier 6-in battery, to just overwhelm their adversary in a single broadside, expecting to disable much of the secondary battery at the same time. A very ambitious ship, the Esmeralda was also the first fitted with torpedo tubes, and significantly heavier and better managed Harvey armor. She was also to be as fast as the Buenos Aires, one knot faster than the Encalada, although design figures were only reached by overheating the boilers. All this made the displacement rose to 7,032 long tons (7,145 t), nearly 3,000 tons more than the previous cruisers.

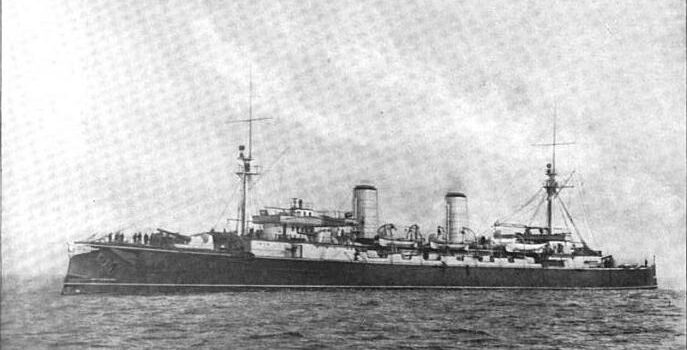

ARA Buenos Aires.

After the Esmeralda was released, Argentina opted for an Italian design instead of British one, the 6800 tonnes Garibaldi-class, which sported 10 in guns instead of 8-in, had a larger battery of 6-in (10), and added to this six fast-firing 4.7 in guns to keep and edge on the rate of fire, plus a good overall armor, but at the expense of speed.

Design of the Esmeralda

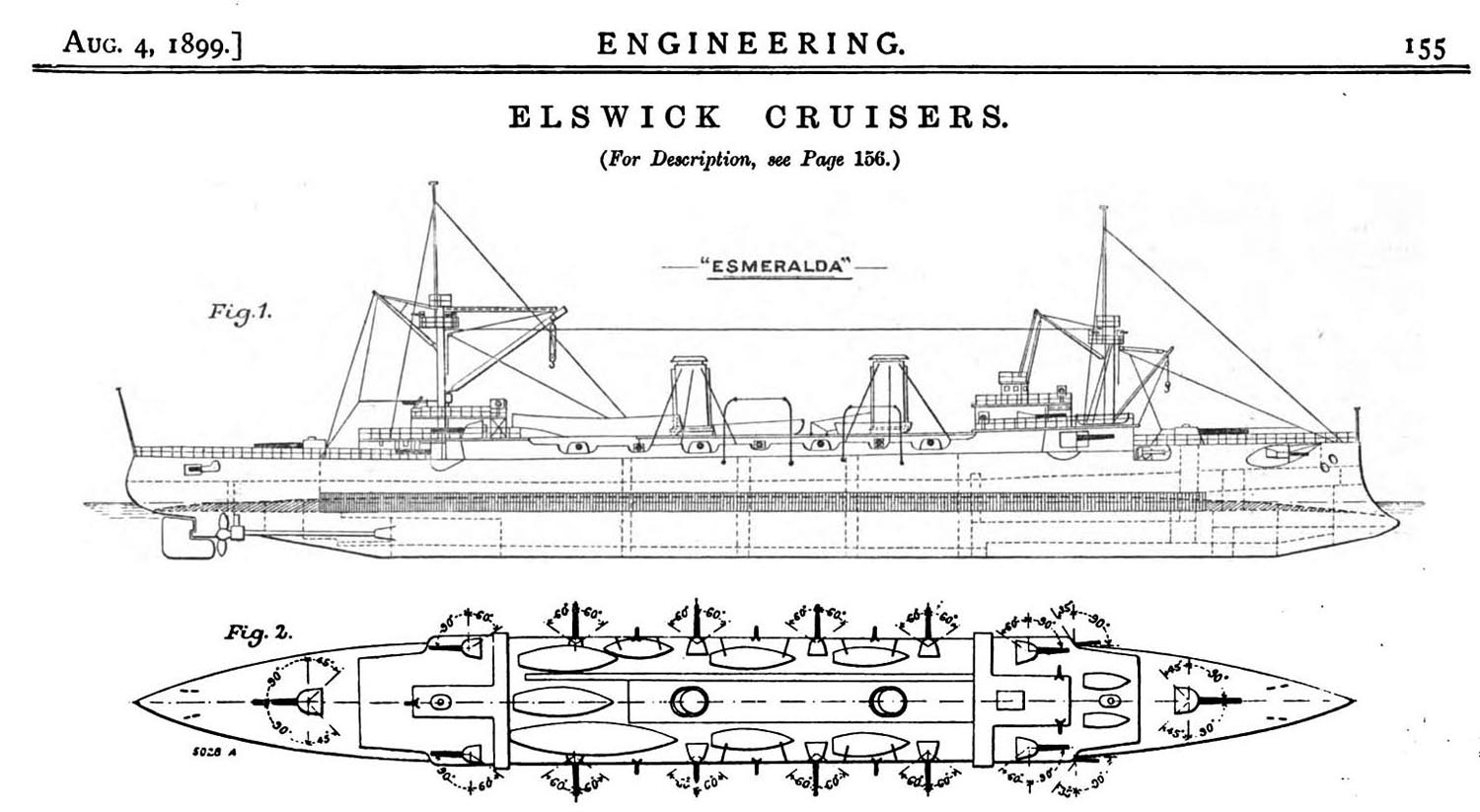

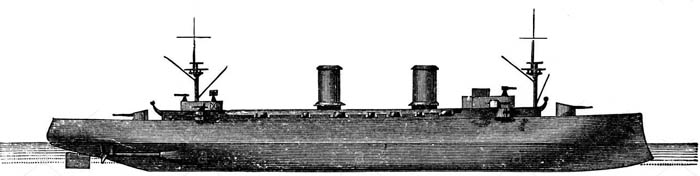

Blueprint of the Esmeralda, part of a 1890s review of Elswick cruisers

Philip Watts, the lead designer of Vickers Armstrong gained over time the patina of late recoignition by authors and historians alike for his role in the worldwide advances in cruiser designs, as during his career he probably drawned more cruiser blueprints than anyone else in History. The main reason was the fantastic capabilities of the Vickers yards to deliver these classes of ships on the export market almost like sausages, and to both camps if necessary, like in the Chilean-Argentinian case. The foggy and controversial figure of Basil Zarahoff was not stranger to this either, also feeding on tension areas like later between Russia and Japan. Watts designed 19 cruisers for customers on a broad spectrum, from Romania to the United States, Italy, Portugal, Brazil and Japan (and many battleships including the HMS Dreadnought). He was replaced in 1912 by Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt and became an adviser for the admiralty.

Nevertheless, the Esmeralda being much longer (20 meters), larger (2 meters) and with a higher draught, the flush-deck hull was also taller, which avoided the use of a turtleback forward deck and wave breaker in front of the forward main gun, for example.

Another difference, outside the armament, was the enclosed deck superstructure, allowing to built enclosed corner casemates, whereas the Encalada secondary guns were all in open air sponsons. Construction-wise, the ship was steel-hulled, wood and copper-sheated.

Brassey’s depiction of the Esmeralda

Armor protection of the Esmeralda

Brassey’s drawing of the Esmeralda

Protection was rather standard but with haigher figures than the previous cruisers: The armoured belt was 152 mm thick (6″), extending 350 feet in the central section and connected to an armoured deck between 25,4 and 50,8 mm (1-2″). There was no specific protection for the machinery or ammo rooms. In addition there were 18 ASW built-in compartments. She was considered one of the most powerful cruisers in the world, incorporating the latest technological advances.

Armament of the Esmeralda

Stern view of the ship in the 1900s

The main armament comprised the classic 208 mm (8 “/40), four guns in all in thick shields fore and aft.

The secondary armament was impressive, all made of 152 mm ,6 “/ 40) guns, sixteen in all.

To deal with torpedo boats, eight 12-pounder cannons, nine 6-pound cannons, 2 3-pound cannons and 8 Maxim machine guns were installed.

In addition these ships had three torpedo tubesof 18 inches (457 mm) on the water line, one in the prow, two in the hull, submersible.

Powerplant of the Esmeralda

She was fitted by two propellers connected to four-cylinder, TE (triple expansion), and later two modern cylindricical model replaced them diring her 1910 refit, with two multitubular Niclausse models. Thanks to this increase in power, she could reach 23 knots.

History

After her service commission, she joined the main cruiser Squadron. Nothing is noted about her service years. On May 2, 1910, she sailed alongside the O’Higgins on a state cruise to Buenos Aires, to participate in the Naval review of the centenary of the Argentine Republic. Later on September 14, she participated in the Great Naval review celebration, on the occasion of the centenary of Chile. Both gestures underlined the good will between countries after the 1890s naval race, but this coincided with the “dreadnought race”.

In 1910, still, until the end of the year, Essmeradla was taken in hands in a dockyard for refitting. She was given new cylindrical boilers, multicubular models from Niclausse and the removal of four of her 152 mm (6-in) cannons from the main superstructure. She stayed active during WW1 and the early 1920s but was outdated by technological advances she was discharged and decommissioned in 1930, after which she was sold on auction for scrapping in 1933.

Specifications of Esmeralda (1897) |

|

| Dimensions | 132.89 m/142.72 m oa x 15.98 m x 6.25 m |

| Displacement | 7,032 long tons (7,145 t) FL |

| Crew | 500 |

| Propulsion | Two shaft VTE, 6 cylindrical boilers, 16,000 ihp-18,000 ihp on forced draft |

| Speed | 22,25 knots (42.13 km/h; 26.18 mph) |

| Range | 8,000 km? 550 t normal/1350 t wartime coal reserve |

| Armament | 2 x 208 mm/40 (8-in), 16 x 152 mm/40 (6-in), 8 x 12 Pdr, 9 x 6 Pdr, 2 x 3 Pdr, 8 Maxim MGs, 3 TTs. |

| Armor | 6 in (152 mm) belt, armored deck 25,4-50,8 mm (1-2 in) thickness |

Author’s illustration of Esmeralda in the early 1900s.

Read More/Src

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-21 and 1922-47.

web.archive.org – from armada.cl

Garrett, James L. “The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone”.

Sater, William F. “The Abortive Kronstadt: The Chilean Naval Mutiny of 1931”.

Scheina, Robert L. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987.6.

Somervell, Philip. “Naval Affairs in Chilean Politics, 1910–1932”.

Worth, Richard. Fleets of World War II. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 0-306-81116-2. OCLC 48806166.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esmeralda_(1896)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chilean_cruiser_Esmeralda

See on ISSUU (escuadra nacional, p.115)

More photos:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Esmeralda_(ship,_1895)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign