Genesis: The Dunkerque (Dunkirk) class (Dunkerque and Strasbourg) were the first French battleships launched since the Great War. Following the 1922 Treaty of Washington, and the Treaty of London (1930), France took advantage of the tonnage allocated to her in terms of battleships and cruisers, making a compromise to allow more vessels to be built in the allocated tonnage.

The global tonnage question was also a matter of pride, and to be relegated to the same level as Italy was considered by the naval staff as insufficient to say the least. Due to her Empire, France needed a fleet at least 20% of the size of the Royal Navy. But the truth was France made it out of the great war impoverished and near bankrupt. Germany would never pay the financial repairs agreed at the Versailles Treaty, so much so that the industrial Sarre (Saar) and Ruhr were occupied by French and Belgian troops to be repaid “in nature”.

Despite the anger upon this apparent downgrading of the French Navy, the exhausted country was in not way able to fulfill the alternative plan wanted by the admiralty. More so, the spectre of pre-1912 young school era mistakes was still looming over it and French politicians of the IIIrd republic looked with suspicion the naval staff initiatives. However it’s a politician, Georges Leygues (photo), which will forge a fleet at the same time coherent and modern, and probably the best the country ever had for decades. The Dunkerque class was like a symbol of it, but its development took years (and the treaty ban for a start).

Despite the anger upon this apparent downgrading of the French Navy, the exhausted country was in not way able to fulfill the alternative plan wanted by the admiralty. More so, the spectre of pre-1912 young school era mistakes was still looming over it and French politicians of the IIIrd republic looked with suspicion the naval staff initiatives. However it’s a politician, Georges Leygues (photo), which will forge a fleet at the same time coherent and modern, and probably the best the country ever had for decades. The Dunkerque class was like a symbol of it, but its development took years (and the treaty ban for a start).

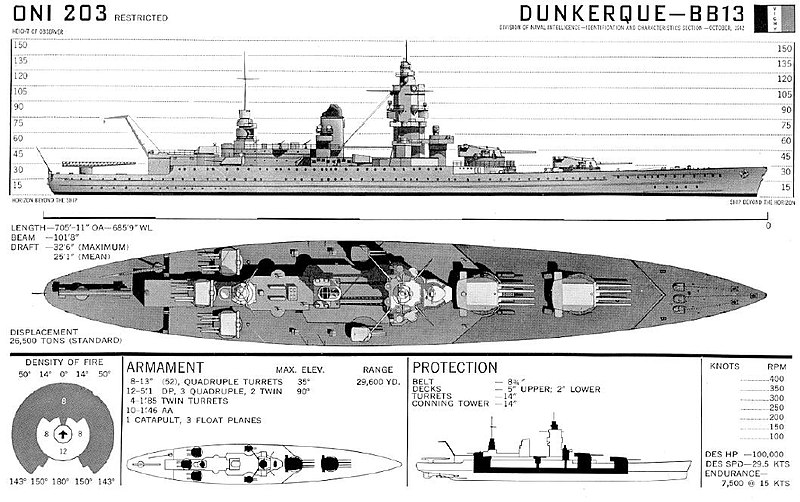

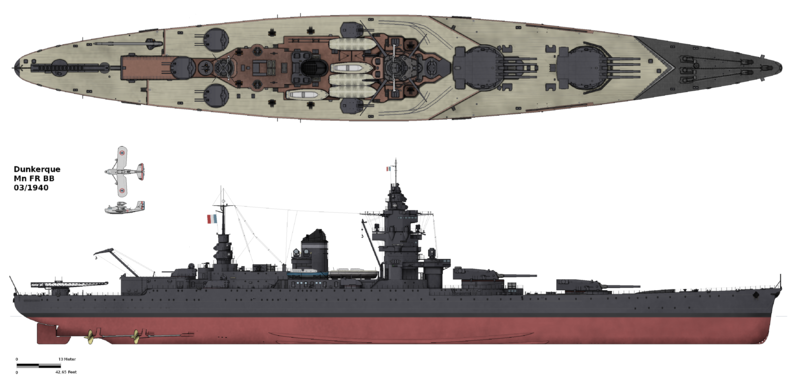

US Navy Recognition plates of the Dunkerque

Development of the new French Capital ship

First off, the Washington ten years ban prevented the signatories, including the French and Italians to built any battleship before 1932. But given the fact both accepted a reduction in size (especially the French), a derogatory measure was approved and France and Italy were allowed to replace two old battleships after 1927. This allowed considering many designs from then on. However, the new Dunkirk were not “battleships”, nor really true battlecruisers, as for this tonnage, protection was sacrificed for speed. The new battleships would emerge as a compromise between both types, as the Scharnhorst will.

The question of tonnage

Both France and Italy concentrated on modernizing their old battleships and keeping their allocated replacement tonnage of 70,000-long-ton to design brand new ships. The choice was soon either two 35,000 tons ships or three 23,000-long-ton (23,369 t) or even four 17,500-long-ton (17,781 t) ones, “pocket battlecruisers” as the future German Deutschland class.

In fact all these cases were carefully examined by the admiralty in turn, but they had in common the trademark French quadruple turrets.

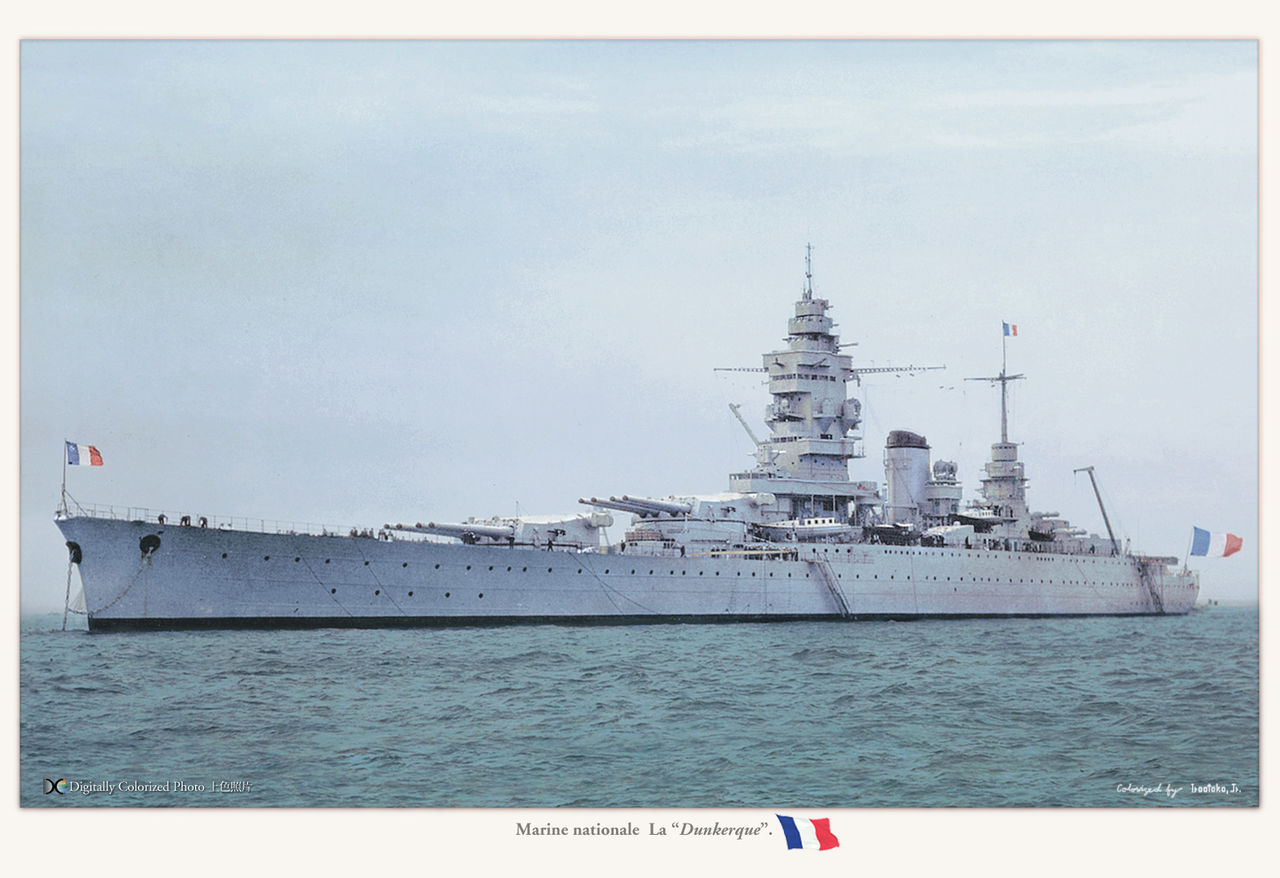

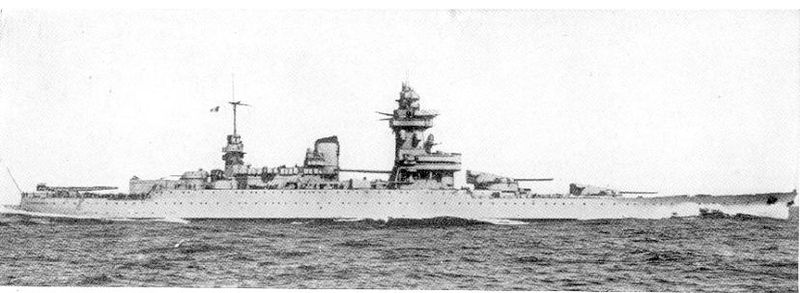

Dunkerque as built, photo colorized by Irootoko Jr.

The question of armament: “Quad or die”

Before even the start of the great war, as the Bretagne class dreadnoughts were under construction with five twin 340 mm turrets, Charles Doyère, head of the Shipbuilding dept. since 1911 and one of the 1912 program writers, proposed the Normandy class. He proposed right away quadruple 340 mm turrets, a world first, ahead of the triple turret innovated by Italy and soon copied by Russia and Austria-Hungary, and the US later for the Nevada4 class.

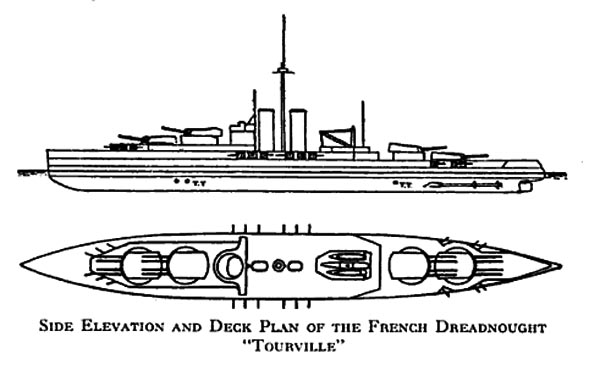

Lyon class blueprint, they would have been completed in 1918-19 if the war has not broke up.

It was a practical reasoning: Since size of the available construction holds was limited, also also limited size and tonnage, using quadruple turrets would it possible to have two more guns in the same space, one same dimensions as the Bretagne class and for a lower weight. This allowed to improve armor, raising it to 340 mm on the turrets armor’s front, down to 250 mm for the two aft turrets.

The Normandy class was promising and was laid down in 1913, launched in 1914, but none was completed. The following Lyon class was larger (as a lengthening of the holds was planned in the years 1915-16), allowing one more turret for a staggering 16 guns volley (4×4). At the time they would have been completed however in 1918, navies planned already 18-in guns (457 mm) which would have far out-ranged the French battleships. Also, the question of shell dispersion was still not well considered at that time.

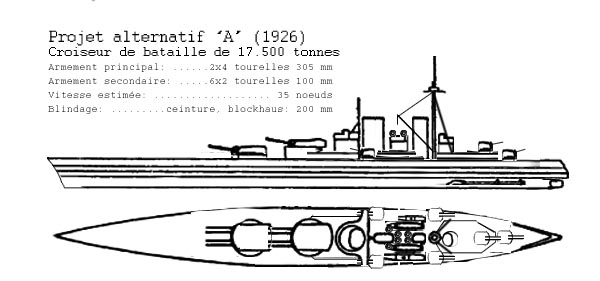

Design A: 17,500 tonnes pocket battlecruisers (1926)*

When in 1925 the Italians launched their Trento-class cruisers, French Vice Admiral Salaun considered the construction of 17,500 tons large cruiser, armed with two quadruple turrets with a seemingly obsolete caliber, 12 inches (305 mm) all forward. They would have been capable of 34 to 35 knots and with a partial armor able to defeat 8-in (200 mm) calibers shells (those of the Trento).

*Note: Letter denominations are for easier understanding, they were never official.

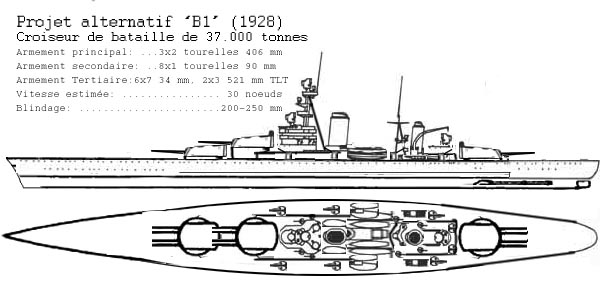

Design B1: 37,000 tonnes battlecruisers (1927)

Next, three 37,000-ton battlecruisers designs were drawn in 1927-1928. Blueprints showed a very enlarged Suffren-class cruiser at 254-metre (833 ft) long, with the same tripod foremast but three quadruple 305 mm turrets, two forward, one aft and eight single 90 mm Mle 1926 HA guns, plus 37 mm AA mounts and torpedo tubes, 220 to 280 mm armour and 33 knots.

The story of the croiseurs de bataille de 37,000 tonnes is convoluted: In 1927-28 Vice-Admiral Violette was Chief of General Staff of the Navy, and launched studies for capital ships, and specifically “battle cruisers of 37,000 tonnes”. 35,000 tonnes was considered a “normal” displacement, 37,000 tonnes fully loaded versus the “standard” as defined by the Washington Treaty, of 32-33,000 tonnes. Blueprints showed a silhouette inspired by the Suffren class cruisers wit two raked funnels and three turrets, including two superimposed at the front, one aft, and a secondary artillery of 130 mm quadruple turrets. Heavy AA comprised single shielded 90 mm guns M1926 as used on Colbert and Foch. They had two side catapults an single crane between the funnel and a hangar for four seaplanes total. The design has many similarities with the future Dunkerque.

A Russian amateur depiction of the 37,000 tonnes battlecruiser, the hull as seen from above and turret size is probably innacurate.

Two types were designed in fact: -The 1927-28 design had twelve 305 mm guns in three quadruple turrets, twelve 130 mm guns. The latter were forward, abreast and behind the forward main artillery turrets, a third superimposed over “Z” main artillery turret aft, eight 90 mm, twelve 37 mm AA, 2×3 TT. Protection ranged from 220 to 280 mm, with 75 mm deck and ASW compartimentation with 20-50 mm sandwiched layers, coal and oil tanks and void ones, similar to the heavy cruisers plus machine compartimentation as the Duquesne class in separated groups. A top speed of 33 knots was planned and the hull was to be 254 m long.

-The second type of 1928, was more a battleship with three twin 406 mm turrets, four 130 mm quadruple turrets, lower propulsion for 27 knots, but better armour.

Construction for both however was dropped at the time as beyond the capacity of existing shipyards. The largest at the time was the Salou basin in Brest, 200 m long. British shipyards were at the time large enough at 270 m, Germans one reached 290 m. Île-de-France (1927) was just constructed and measured 245 m long and this was not enough. For the planned Normandy, famous transatlantic of 313 m, Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, Penhoët was forced to built a new construction hold, hold n ° 1. but its construction was beyond the French Navy budget at that time, so the project was postponed, and relaunched later on more reasonable dimensions, with compromises.

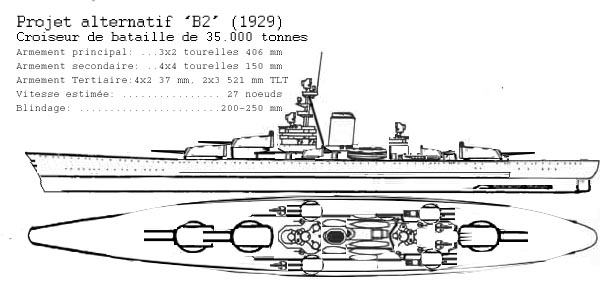

Design B2: 35,000 tonnes battlecruisers (1928)

The second, 1928 alternative design called for a capital ship armed with three twin 406 mm turrets and four quadruple 130 mm turrets which was more capable of dealing with other battleships. It was shorter at 235 metres but wider, armor was thicker but the powerplant was smaller, thus reducing the top speed to 27 knots. However the choice was easy to make as there was no dock large enough to build a 35,000-ton hull longer than 250 metres (820 ft) at that time. In fact building the required docks would have cost the same as the two battleships, just when more stringent naval restrictions were discussed.

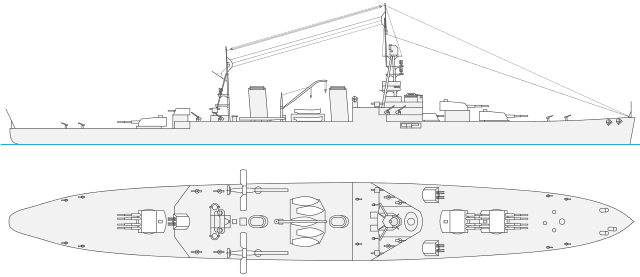

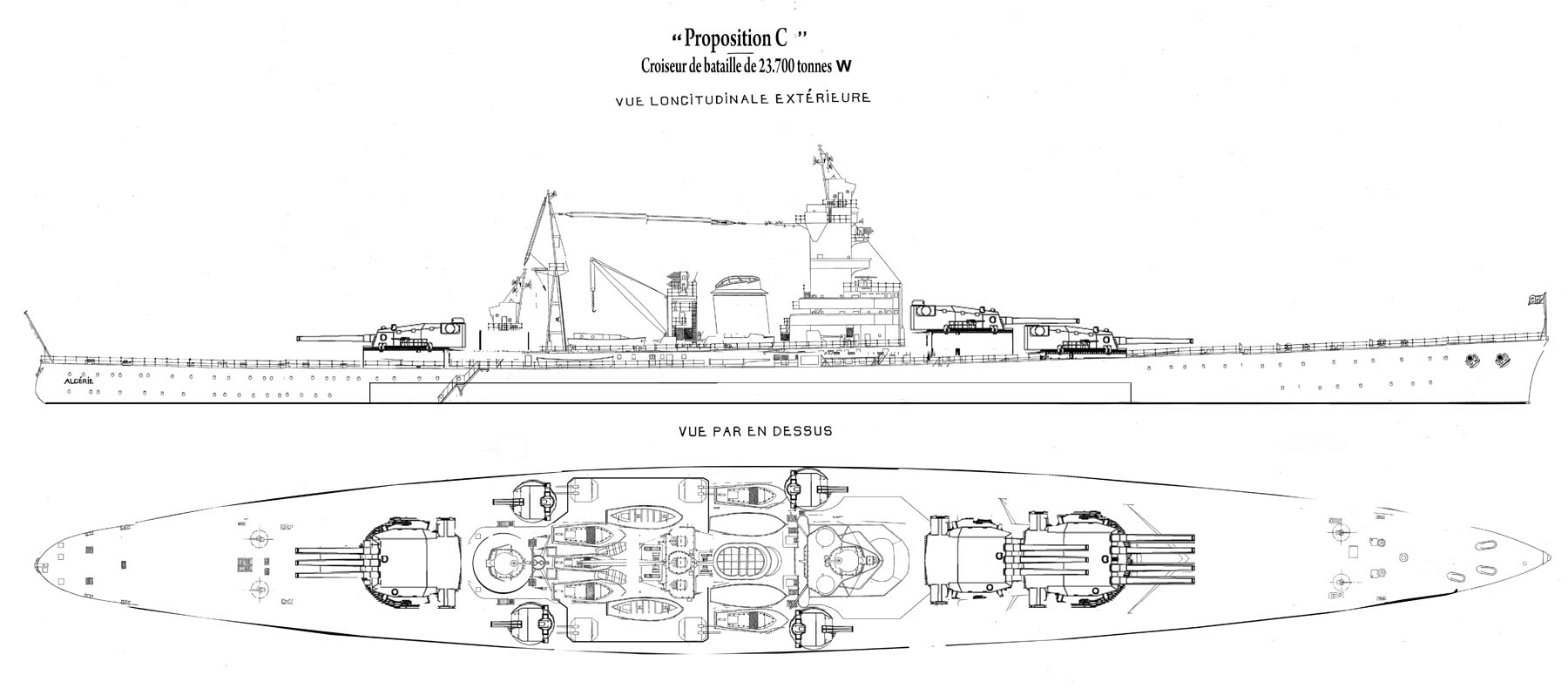

Design C: 23,700 tonnes light battlecruisers (1929)

Author’s reconstitution from the original Algérie blueprint

The last chapter of this development came when the new chief of staff of the Marine Nationale, Vice Admiral Violette, ordered the Service Technique des Constructions Navales to design a modern “armoured cruiser” of 23,690 tons, a ship with a triple and quadruple turrets forward and one triple aft, all armed with the same 12 in caliber but protected with 8 in plates only.

They were to be also armed by four twin 138 mm turrets and eight twin 100 mm AA turrets for 29 knots, and a general appareance which recalled the Algérie. In fact the design had the most influence over the Dunkerque proper development.

In Geneva, indeed, a Committee for Disarmament from the League of Nations planned a Washington treaty expansion into 1936, and United Kingdom strongly urged to cap displacement and maximum caliber to 25,000 tonnes and 305 mm for new capital ships. The French Government protested it needed larger ships and at that time pushed for larger designs, but the French Admiralty nevrthless, allowed to sturdy a contingency design to use the available tonnage, of 23,333 tonnes. Therefore a 23,690 tonnes “protected cruiser” was worked on by 1929. It was to have three 305 mm turrets, triple and quadruple and eight 138 mm guns, in twin half turrets as those of the Mogador class, and twin DP 100 mm (Algérie). With a sungle funnel and superstructures recalling the latter, it was closing on the silhouette of the Dunkirk.

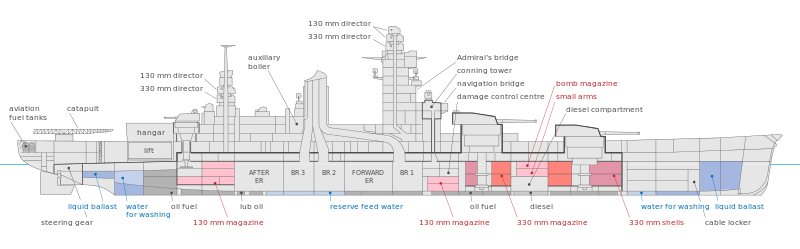

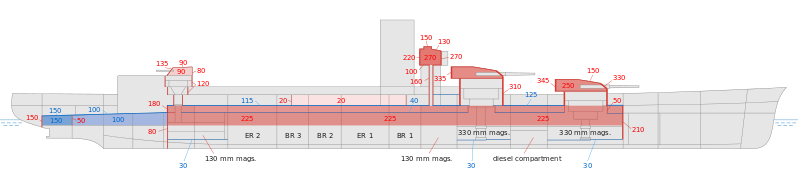

Armour scheme of the Dunkerque class

Final displacement choice and the Deutschland class

What really decided the admiralty for good was the threat of Reichsmarine’s “pocket battleships” recently launched of the Deutschland class. Both ships “cheated” over the 10,000 tons Versailles treaty limit. They were superior to any cruiser yet fast enough to escape battleships.

It was like a reinvention of the battlecruiser concept and perfectly suited for commerce raiding. Only three ships back then were able to catch these, the British battlecruisers Hood and the two Renown class. There were doubts also to the will or capacity of the Royal navy to protected French colonial routes in case of war with Germany. So new designs were immediately scrambled to deal with the new situation and protection against German 280 mm shells was at the center.

With the choice of a speed of 30 knots, the final design displacement was a relatively easy choice: 23,000 – 25,000 tons, which fitted British limitations and allowed to built three capital ships for the allocated tonnage. Although the London 1930 treaty prolongated the “battleship holiday” to 1936, the Washington’s derogatory measure still applied and negociations took place between France and Italy in regards of their respective plans.

Bilateral discussions ended in March 1930 with the acceptance of a 23,333 tonnes standard capital ship until 1936. The French had from then free hands for the Dunkerque. The new design was quickly drawn, with a 213 m hull, 27.5 m wide to fit in the existing dockyard, and 30 knots. A 230 mm armored belt and well thought ASW and machinery compartimentation, plus two quadruple 305 mm/55 gun turrets forward. However after a parliament submission, it was rejected.

By 1931 Admiral Durand-Viel became C-in-C and reworked the design for a new submission: This time, tonnage was augmented to 26,500 tons and the hull slighly larger to accomodate a caliber capable of dealing with Italian ships, 330 mm/50 guns. Armor was also slightly increased, and an additional 130 mm DP turrets were procured. The design was accepted in 1932 and the Dunkerque was ordered on 26 October and laid down on 24 December at the Arsenal de Brest shipyard.

The choice of the main artillery

The last unfinished battleships built by France were the Normandy class (1915), followed by the Lyon class. Both had in common a main artillery in quadruple turrets, but in separated pairs. The solution, unique to France, made it possible to maximize protection of vital parts related to artillery and ammunition supply.

The Lyon class, with their four quadruple turrets, would have had 16 pieces for their main artillery, a world record for a battleship. The weight of these turrets was not negligible either. However in the new tactical developments post-Jutland the advantage favored hunting fire, which explains the original chosen solution of the front artillery for the Dunkirk class, whose genesis went back to 1925 and the British Nelson class that showed the way.

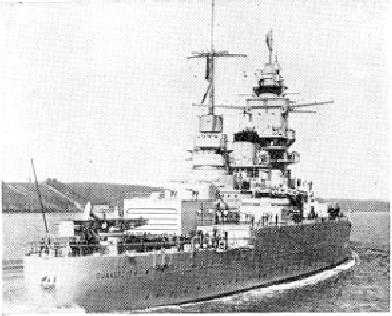

Dunkerque in 1938, src: ONI203 booklet for identification of ships of the French Navy, Nov. 1942

Italian’s replica to the Dunkirk

However, when these ship’s construction was well advanced, Italy announced the construction of the Litorrio, in response to Dunkirk, with armor this time equivalent to their main artillery.

As a result, plans were made for the next class, the Richelieu to answer them in turn, to which the Italians replicated during ww2 with the Roma class. The two Dunkirks stemmed from a reflection on the usefulness of battleships, since no major naval battle had a lasting impact on strategic level, the latest being that of Jutland. In general all naval battles of WW1 with few exceptions have been battlecruiser engagements.

Also the defense of trade links in the French colonial Empire seemed to be paramount in 1930 and cruisers always had been considered better suited to this task. These ships were therefore designed specifically for this purpose. Even after the release of the heavier Scharnhorst, their artillery and armor remained nearly adequate. The Dunkirk was launched in 1935 and her sister-ship Strasburg in 1936. They were in operation in 1936-37.

Design of the Dunkirk, in detail

Dunkerque, stern view 1940 – ONI, USN Identification group Nov. 42.

Powerplant, speed and range

Propulsion consisted in four 4.20m bronze propellers at the end of the shafts turned by Parsons gear turbines, with the steam coming from 62 boilers made at Indret. The powerplant was divided into four groups but five rooms: Forward was located the No. 1 boiler room under the forward Bridge turret two boilers, then came the front turbines, in two groups made of Parsons turbines mated on the external shafts, medium pressure a low pressure turbine. The third space contained two more boiler rooms right under the main funnel. Then came the central room boilers and rear room boilers and aft turbine room, with the high pressure inner shaft Parsons turbines.

Innovative Compartimentation

Sets of turbo generators were installed in the two turbine rooms. This arrangement was quite an innovation for the time. It was pioneered already by the projected 17,500 tonnes battlecruisers, and implemented on the first French 10,000 tonnes cruisers of the Duquesne class. This arrangement was not a substitute for protection but rather a rational way of managing power in case of a hit. A single hit was now unable to disrupt the whole power system. Even turbines were placed far apart and between boilers and rooms and turbines thick bulkheads prevented flooding.

Performances

Both battlecruisers were planned to achieve a top speed of 15.5 knots with just 25% of the available output, limited on two shafts, and 22.5 knots with four. Indeed the two high-pressure turbines were only started to reach 35-50% of the normal power, rated as 112,500 hp. This allowed, when all were in action, to propel the ship at 29.5 knots. Speed tests of May 1936 on Dunkerque and in July 1938 for Strasbourg, shown they were capable of sustaining 31 knots, notably on the “9th hour” run, at outputs, respectively of 132,000 hp to 135,000 hp.

Radius of action

Maximum capacity was comprised between 4,500 tonnes to 5,000 tonnes of oil (peace time and wartime) but it was in practice limited to 3,700 tonnes, leaving compartments to fill counterbalance load as an ASW protection. It was also determined not to fill these fully as this attenuated the torpedo hit shockwave. Autonomy as listed was 7,850 nautical miles at 15 knots. It went down to 2,450 nautical miles at 28 knots sustained for long hours.

Sea trials also shown smoke interference with the bridge control facilities from the flat-topped single funnel. Both battecruisers would receive in 1938 a funnel cap in “volute”, larger than the old whistled top. It was also determined during the winter of 1939-1940 in the Atlantic both ships were not perfectly suited for heavy weather, taking gushes of water quick. The same problem was identified at the same time on KMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau so they were fitted with their so-called “atlantic” bow.

Armour protection

All or nothing scheme

Total protection figure on both ships represented 35.9% of the total displacement, the highest percentage for a French war vessel at that time, but was of the “all or nothing” scheme.

The armoured belt extended over 126 m (60% length), and was 225 mm thick leaving an unprotected fore deck. The forward bulkhead was 210 mm thick and aft one 180 mm thick, while the upper armored deck was protected by 125 mm and lower one only 40 mm. The conning tower/bridge was 270 mm at the front, 220 mm aft and 210 mm on top, while the main turrets’ bases were protected by 310 mm barbettes while the turret faces had 30° sloped 330 mm thick faces, 345 mm back. The superfiring turret was protected by a 335 mm face and 150 mm roof. The secondary turrets were given 120 mm for their barbette, and the turrets themselves were protected by a 135 mm face, 80 mm back plate and 90 mm on the roof. The twin turrets only had for that part 20.5 mm.

The Superior Council of the Navy wished to modify the Strasbourg during construction. Plans were altered. The battlecruiser armoured belt was raised to 283 mm, the forward bulkhead thickened to 260 mm, and aft one down to 210 mm; The main turrets’s barbettes were now 340 mm thick, faces 360 mm, back 352 mm (A) 342 mm (B) and roof 160 mm. This represented a 749 tonnes displacement increase, to 37.2% for the total.

Underwater protection

The principle of underwater protection consisted in a lateral “sandwich” of armored partitions ranging from from 16 mm to 50 mm in plating thickness, plus compartments, mostly filled with a rubber-based compound called “ebonite foam” or left empty, to be used as fuel tanks. The outer part of the ASW longitudnal compartment close to the armored belt was 1.5 m tall, filled with foam ebonite. Partition between them was 16 mm thick. Following compartments were a filled one 0.9 m deep, fuel tank 3.90 m deep new 10 mm thick separation, 0.70 m deep void compartment and this ended with a 30 mm torpedo partition, using plates with special steel. Under the 330 mm turret barbette, the torpedo partition was 50 mm and the fuel tank was replaced by ebonite-foam filled for a grand total of 7.50 m wide ASW partition. This was also innovative, way above existing battleship’s protection, rarely beyond 5 meters in width. This protection proved efficient at Mers el-Kébir (July 6, 1940), preventing damage from fourteen submarine grenades which exploded near the hull of Dunkerque when she evaded the port.

Armament

For the first time, French battleships used a quadruple turrets, and it was also a world’s first which interested naval experts around the world. This was a radical choice, which had its logic, but also tradeoffs as we are about to see.

Main artillery

The long-planned quadruple arrangement dated back at least from 1911. The turrets were arranged forward, following ideas derived from the experience of WW1, also tried on the Nelson class. This arrangement was also adopted by the Richelieu class and contemporary King Georges V class, while the next planned (Gascoigne class) had both turrets rearranged fore and aft.

The admiralty thought quadruple turrets as a way to reduce weight and improve the armor, in this never-ending puzzling problem of how to combined best armament vs. protection vs. speed, something all admiralties tried to resolve. The two forward turret arrangement made it possible of a free range forward, presenting a small target when approaching an adversary. When the Dunkerque was started, it became overnight the most powerful modern battleship compared to its Italian or German rivals, and faster than any other battleship other than pure battlecruisers like the Hood.

The forward-only artillery was possible in a relation with inferior navies, likely to retreat. The artillery disposition however was quite radical and very soon doubts would appear over its merits, starting as early as December 1937. While Dunkerque was undergoing testing, some in the naval staff voiced a design revision for the next 35,000 tonnes design, which will resurface with Gascoigne in 1938. The battle of Rio de la Plata showed indeed with the Amiral Graf Spee duelling against three cruisers, that evolution of the fight imposed to fight in retreat, while on paper its artillery was superior and could keep its adversaries at a distance. The latter closed in, the light cruisers even acting “as destroyers”.

But before these considerations, on paper, the main goal for this artillery was to allow a more radical “all or nothing” approach for protection. The armored citadel was much reduced as it was reduced only between the main turrets, resulting in a weight saving allowing to increase plates thickness. This was so refined, these armor figures even went further and beyond the scheme planned for the Normandy class in 1912. This why both ships were eventually classes as “battleships” and not battlecruisers, as their protection figures equates, or went beyond the artillery caliber, characteristic of a battleship.

The use of two quadruple turrets however, had drawbacks.

-If one of these turrets was knocked out, half of the main artillery would be gone. The turret design therefore integrated an armored partition 25 to 40 mm thick inside the turret, just like hull compartimentation, preserving half of the guns. It showed its effectiveness when a 16-in shell (381 mm) hit the Dunkerque at Mers-el-Kébir. A hit in the barbette was also a huge risk and to further reduced risk of propagation the two front turrets were located 27 m from each other versus 19-23 m on HMS Nelson. Calculations also included the beam versus gunnery size and weight. It was of 406 mm/32 m on the master beam versus 340 mm/31 m master beam, so comparable.

-The other factor was shell dispersion. It was however only really a problem in case of a full broadside (when all guns fired at the same time). It happened for exhibitions, trials and reviews, but in operation, the phenomenon of dispersion was clear enough to stage firing (ex. two guns from both turrets, then the two next, or firing outwards guns only). Unfortunately, the accuracy of both ships was never seriously tested. Perhaps only the gunnery duel between the Vichy-Held Jean Bart against USS Massachusetts in November 1942 gave some clues.

Secondary artillery

The Dunkerque’s secondary artillery was concentrated aft, more as an afterthought to avoid too daring destroyers and light cruiser to close to torpedo range. Again, the Nelson class solution was studied. But the Dunkerque class innovated by adopting a dual purpose anti-ship and long-range anti-aircraft model. Brand new, it was fixed at 130 mm in caliber, and for better concentration, placed in three armored quadruple turrets. There was one axial above the hangar and two broadside, little armored.

The 130 mm gun was considered however too weak in anti-ship use and too slow for effective AA fire. This caliber was used by the Chacal class and Bourrasque and Adroit class destroyers since the 1920s, whereas the following Bison and Fantasque classes were armed with the 138.6 mm guns. The same was planned for the 23,690-ton ‘protected cruiser’ project of 1929. It was considered a middle ground in secondary caliber range, between the 6-in and 5-in, also adopted by the U.S. and British (5.25-inch (133.35 mm) navy.

Dunkerque’s 130 mm DP guns fired a 33.4 kg Shells (OPf Mle 1933) at a 20,800 m range, when elevated to 45°. Initial velocity was 800 m/s. When elevated to 75° in AA mode, they fired a 29.5 kg Steel Explosive Shell (OAS Mle 1934) at 840 m/s and 15,000 m practical ceiling. A total of 6,400 rounds were carried (400 per gun). The guns could also fire a Lighting Shells (OEcl Mle 1934 30 kg) and the rate of fire was around 10-12 shots per minute while turrets traversed at 12°/s and elevated at 8°/s.

The Dunkerque’s secondary artillery was fragile and complicated, and unsatisfactory in both areas. The US Navy put some emphasis on semi-automated loading systems, allowing their ubiquitous 5-in (127 mm) /38 caliber twin mount (North Carolina, South Dakota, aircraft carriers, many cruisers) was able of 15 rpm, and up to 22. But moreover it was better served by the radar-assisted firing direction system Mk37 FCS during the war. Some of its technologies were not available to the French in 1930.

The Royal Navy’s 5.25-inch (133.35 mm) found on the five King George V-class battleships and Dido class cruisers, was initally as slow as the French models and criticized, but the war allowed them to be much improved, tanks to the RP10Mk2 FCS and HACS AA firing control system first seen on HMS Anson and Bellona class cruisers. In contrast, the older French FCS did not had time to mature and never worked properly. Compared to it, French 75 mm, 90 mm AA gave satisfaction. It should be noted also that the French had no access to a radar, which was fitted on the Richelieu in 1942, and eventually found its way on the Strasbourg juste before her scuttling.

AA artillery

French Hotchkiss naval 37 mm Modele 1925.

Until the fully automatic twin mount 37 mm AA ACAD M1935 was available (capable of 150 rpm) the naval staff settled for the older semi-automatic Model 1933, capable of only 15-20 rounds per minute. It was by comparison much lower than the British Pom-Pom (200 rpm) and standard Bofors 40 mm (120 rpm). They were mounted either side of the 330 mm B turret in single positions, two other abreast the funnel and aft on a twin mount platform between the axial secondary turret’s back and aft telemetric tower, so eight in all, four single, two twin.

In addition, the Dunkerque class carried thirty two 13.2 mm machine gun in quad-mount, none of them. They were derived from the well-proven Hotchkiss model also adopted by the IJN. It was a dependable, sufficient model for the aviation of the 1920s (but no longer in WW2), based on the same gas-operated trademark system derived from the 8 mm mle 1914, which proved extremely reliable. The choice of a 13.2 x 99 cartridge was changed to a 13.2 x 96 cartridge just as the Dunkerque class were fitting out. They were fed overhead by 30 round curved box magazines and were able of 450 rounds per minute, 200-250 rpm sustained due to magazine changes and overheating.

French Hotchkiss 13.2 mm M1929.

Fire control

The fire control arrangement of the Dunkerque was inspired by the British Nelson class, with a massive tower superstructure instead of a tripod, strong enough and high enough for the telemetric turrets to stand above the funnel’s smoke. The tower bridge was so high (even reminiscent of IJN battleships !) that for the first time an interior elevator was fitted to access all levels instead of simple ladders and steep stairs (still mounted externally as backup). The tower supported three telepointers on the same axis, for a total weight of 85 tonnes. Aft, just before the three secondary turrets, was fitted a much lower second tower, with two telepointing stations on the same axis.

On the front tower comprised first telepointer A for the main artillery (45 tonnes) fitted with a 12 m triplex OPL (Precision Optics of Levallois-Perret) rangefinder. In 1940 it was considered obsolete and replaced by a 14-meter OPL model. The second unit was used for the secondary artillery and comprised two telepointers, 25 tonnes each. The lower one was intended for anti-ship use (6 m duplex OPL stereo rangefinder) while the upper one (20 tonnes, 5 m duplex OPL stereo rangefinder) was for AA guidance.

The aft tower comprised two telepointers with an OPL duplex stereo rangefinder of 8 m (main artillery telepointer B), and a 6 m for the secondary artillery. These turrets were protected against gas, closed tight, and had splinter lining. Additionnal turret roof models were fitted on Strasbourg later: A 5 m OPL rangefinder for the upper turret and conning tower roof for Dunkerque, plus two smaller telepointers (SOM stereoscopic rangefinder) installed on the front tower’s for night firing. In 1940, a 12 m duplex OPL stereo range finder was fitted in both turet roofs and a 6 m OPL stereo range finder on the 130 mm secondary turret roofs.

Optical watch was allowed on three stations either side of the bridge, intended to spot surface ships, around navigation bridge, and five watch stations used for AA optical detection on the sides, plus five used to detect mines and torpedoes. For night illumination, Strasbourg had six 120 cm projectors: Four were located on a platform between the funnel and aft tower, two forward of the main tower. Dunkerque had seven of these.

Onboard aviation

Aviation facilities comprised a hangar, catapult and crane to retreive the floatplane at sea and place it on the catapult. They were modern and well designed, and high enough not to be disturbed much by heavy weather’s spray. The single catapult was 22 m long, 360° traverse. It launched its payload thanks to a compressed air piston, fed by a unit installed in the axis of the aft deck; Its capacity allowed to propelled a 3,500 kg plane at 103 km/h.

The crane had a lifting capacity of 4.5 tonnes. The battleships carried initially three Gourdou-Leseurre GL-832 HY models. In the mid-1930s they were replaced by two single Loire 130, accommodated with folded wings in the two-storey hangar. It allowed a third to be ready on the catapult at all time, or transferred and tightly moored on the roof of the hangar, where a fourth could be accomodated as well. The hangar housed all necessary repair and maintenance facilities as well to service the planes.

The Loire 130 was a small, compact one-engine seaplane powered by a Hispano-Suiza V12, 720 hp unit. The plane weighed just 3,500 kg fully loaded, but was slow, reaching only 210 km/h, over 6,500 m and capable of flying however for 7h30 at 150 km/h. They had two defensive 7.5mm machine guns, but could strafe submarines or small ships with their two 75 kg bombs.

The Dunkerque class in action

Both battleships were quite active until the fall of France, with their short peacetime career well occupied by squadron exercises. They were based in Toulon and in North Africa. During the conflict, the two ships chased German raiders in the south Atlantic (including KMS Graf Spee which they had been specifically designed to cope with), and protected merchant traffic.

Strasbourg underway, side view – Src ONI203 booklet for identification of ships of the French Navy Nov. 42

In December 1939, Dunkerque took the gold reserves of the Bank of France to Canada. The Atlantic task force force, based in Brest and formed by these ships and heavy cruisers and destroyers, was transferred in the Mediterranean in the light of the changing attitude of Italy in June 1940. They were now based at Mers el Kebir, Algeria.

Dunkerque

Dunkerque

Construction and trials

Plans and blueprints of the ship were drawn by the Technical Service for Shipbuilding and Weapons (S.T.C.A.N) and she was laid down in the form of the Salou in Brest, December 24, 1932. The hull was floated on October 2, 1935 and launched, then completed and fitted out, ready for testing on February 1, 1936. She was fully armed and equipped by December 31 while her first official trials took place in May 22 1936, completed by October 9, 1936. She was commissioned in May 1937, but not officially entered service. Further testing, fixings would go on for nearly a year.

Pre-service trials and exercizes

In her first sortie, Dunkerque was sent to represent France on May 23, 1937, at the Spithead naval review, Portsmouth, for the coronation of Georges VI, as the new head of the United Kingdom.

On May 27, she was parading off the Ile de Sein (Britanny) for a combined naval review with the Mediterranean Fleet.

By August 15 1936 she entered the Brest arsenal dockyard for maintenance, which was long and complex, but completed between September and October 1937, concluded by artillery drills. On January 8, 1938, one of the workers died, wedged between a 130 mm turret and the battleship railing. On January 20, 1938, she sailed out for transatlantic cruise to the West Indies and back to Dakar on the W African coast.

Back home, she paid a visit to her namesake city, staying there as an attraction in July 1-3, 1938. She was at Brest later and Saint Vaast la Hougue one day after. On July 17, she hosted the British Royal family in Boulogne and bring them to Calais.

Prewar Service

Dunkerque entered officially active service on September 1, 1938, joining the Atlantic squadron as a flagship for her first mission. On November 18-20, she teamed up with the aircraft carrier Béarn, escorted by the torpedo boats Boulonnais, Foudroyant and the sloop Somme, in exercises off Brittany. She entered drydock for maintenance from November 29 until February 27, 1939. She made a few escort missions until April. Until April, 16, she was in the Caribbean, together with the cruiser Jeanne d’Arc. Bith ships were mobilized during the Sudetenland crisis, searching for the German pocket battleships off the Spanish coast during the civil war.

In May 3-6, 1939, she teamed with Strasbourg to visit Lisbon, Portugal. From May 23 to June 14, she toured British ports, and was back in Le Havre on June 20.

Wartime Operations: 1939

After a maintenance maintenance during the summer, she was scrambled in operations on September 2, 1939. She sailed out with the 1st squadron, escorting the minelayer Pluto to Casablanca and Jeanne d’Arc to the French Caribbean (Antilles). She was back to Brest on September 6 while her seaplane HS.21 was lost at sea, while searching for the CGT SS Flandre. Two days later, another of her seaplane was damaged in operations.

At that time, Dunkerque was part of the Raid Force: Dunkerque, Strasbourg, the cruisers Montcalm, Georges Leygues, Gloire and several destroyers. It operated from Brest, under command of Vice-Admiral Gensoul, onboard Dunkerque. In October-November 1939, she joined the Royal Navy to protect maritime trade, trying to spot German surface raiders.

The combined forces comprised Strasbourg and the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes in the South Atlantic, searching in particular for the KMS Admiral Graf Spee, notably patrolling off the Cape Verde Islands. Meanwhile the other half of it combined Dunkerque and HMS Hood, operating in the North Atlantic. They were scrambled to look for the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, recently sinking HMS Rawalpindi on November 23, 1939. By December, Dunkerque transferred gold reserves at the Banque de France to Halifax, Canada. At hr return, she escorted a British convoy, teaming with with HMS Revenge; She was back to Brest on December 30, 1939.

Wartime Operations of 1940

Early in 1940 the attitude of Italy was unclear. The Force de Raid sailed to the Mediterranean, starting operations in April 1940 at Mers-el-Kébir, to almost immediately sail back north, to Norway, due to the German invasion starting on April, 9.

By April 12-24, Dunkerque stays on high alert in Brest. She then returned ton Mers-el-Kébir for further operations, starting on June 13, 1940. She sailed to Sardinia, shelling the coast. however after the French debacle the British started to worry on the fate of the French fleet. After the French signed an armistice, the admiralty rushed orders for preparations to to seize the French fleet or neutralize it by all means necessary (Operation Catapult).

Mers-el-Kébir

Force H (Admiral Somerville) was made responsible by Winston Churchill for execution of the plan. Operation Catapult also concerned the British ships anchored in British Ports. French Forces at Toulon were important, but the objective was well defended, whereas Force de Raid was in Mers et Kebir and other elements in Alexandria and many other places. The Royal Navy concentrated on the best units.

Therefore by July 3, 1940, in the afternoon, the Royal Navy’s Force H faced off the best squadron of the French Navy off Mers el Kebir. Due to Admiral Gensoul cold reception, discussions under an ultimatum dragged on, and crews were uncertain of their fates; In the hypothesis the British fleet would fire, the French ships had no chances. They were anchored with their prows (and big guns) facing the cliffs and could not manoeuver.

The umtimatim eventually expired, and under Churchill’s insistence the matter was settled quickly, Admiral Sommerville eventually opened fire. Dunkerque, as soon as the first cannon shots were heard, struggled to drop its moorings and heated its powerplant. Meanwhile, and due to the short distance, she was accurately framed and hit four times, by 381 mm shells. The first hit “B” turret, the concussion being enough to kill all personal. The right secondary half-turret wwas hit and disabled while the other remained operational. The aviation hangar and catapult were damaged, and another 130 mm twin turret was disabled. Another hit destroyed the heat lines, depriving the ship of all electrical power. To avoid sinking, her captain manoeuvered her to the other side of the harbor and grounded her, as water was filling her bottom.

Meanwhile Provence was also grounded to avoid sinking and Bretagne was blasted, capsized and sank. Meanwhile Strasbourg was ready sooner, avoided being hit and scrambled to the harbor entrance, escorted by 5 destroyers. She escaped, framed by 381 mm shells from HMS Hood and attacked by Fairey Swordfish bombers from Ark Royal, (see later).

Dunkerque’s protection was tested during this “battle” showing her 225 mm armored belt did not stand a change against the 16-in (381 mm) shells fired from 16,000 m. Admiral Esteva, Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy of the Mediterranean discovered the damage was however less extensive that all feared. Willing to reassure the population he spoke of minimal damage, and this was publicized in the press in Oran, and soon known of the British Admiralty. Soon Admiral Somerville was ordered to return at Mers El Kebir and definitely write off the Dunkerque.

To avoid bombarding civilians at the fishing village where Dunkerque was stranded, Sommerville decided on July 6, 1940 to scramble the aviation: Three waves of Swordfish from Ark Royal took off to drop torpedoes. Dunkerque’s most evident damage was caused by the explosion of depth charges carried by an auxiliary patrol boat which took a torpedo hit while moored alongside the battleship. The hull was blasted open, making 200 victims in addition to those of the previous attack. Sommerville then departed, satisfied of the result, and Dunkerque would stay there until February 1942. Summary repairs has been carried out with some difficulties, enough for the battleship to sail to Toulon and placed in dry dock for further repairs.

By November 1942 and operation Torch, situation degenerated. The French fleet in Toulon was prepared for the worst. By November 27, 1942 indeed, the Germans invaded swiftly the “free zone” and scrambled to Tooulon, in order to seize the fleet (Operation Lila). However as they burst into the arsenal, almost all of the docked vessels were in the process of being scuttled by their crews. Dunkerque was by then still in dry dock in the Vauban basin, repairs far from completed. She never returned to active service after Mers El-Kebir.

Strasbourg

Strasbourg

The famous sister ship saw her keel laid down on November 25, 1934, at hold No. 1, Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire Penhoët. It was the same place where the famous liner Normandy was built. The French battleship was launched on December 12, 1936 and headed to Brest for fitting out, armaments and testings, lating until June 1938. After the nearly year-long period of exetended exercises and furthers tests and modifications, she was admitted in active service by the fall of April 1939. Together with her sister shi, she formed the 1st Line division. In May 1939, she teamed with the 4th cruiser division and headed for Scotland, Liverpool, Glasgow, Scapa Flow and Rosyth in an effort to reassure the public, the French Navy can add her might to the Royal Navy when facing Germany.

Force de Raid in the Atlantic

On September 3, 1939, she joined her sister ship in Gensoul’s Raid Force in Brest. Outside both battleships, the unit also comprised the 4th cruiser division and several of the large French destroyer of the Mogador class and others. The Raid Force soon was split into two groups, and Strasbourg teamed with Force Y, based in Dakar. Assisted by the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes which became her eyes, and screened by the heavy cruisers Dupleix and Algerie (Admiral Duplat), this forced started a sweep off the Cape Verde Islands which lasted until the end of November 1939, trying o locate and intercept the Graf Speed. Strasbourg will left Dakar, leaving behind 800 powder pods, used in September 1940 by the Richelieu, possibly a reason behind her 380 mm guns serious misfires. Admiral Graf Spee was finally intercepted in December.

Strasbourg was back in a recompleted Raid Force, and joined the Mediterranean in late April 1940 amidst tensions with Italy and a dark fate on land. The armistice of June 1940, saw her anchored poop facing the berth, and the sea, at Mers el-Kébir. She was in the process of being demobilized.

Operation Capatult: A miraculous escape

During operation Catapult in July, Gensoul received a British ultimatum to either join an English port, French port in the West Indies or to scuttle. Force H on this fateful July 3, 1940, afternoon’s end, as discussions went on without end with Gensoul, eventually opened fire. Soon, shells falling from 16,000 m framed ost ships with deadly accuracy. Two battleships and the Dunkerque were hit several times in succession by heavy shells. Howver amidst the chaos, Strasbourg crews out-did themselves to extract the ship from its precarious position, and warm her machinery enough to sail past the other ships, capsizing or burning, started to exit the harbor.

Captain Collinet, indeed before even news of the ultimatum when Force H was spotted, carefully prepared its mooring chains to be dismantled and drop its anchors, while the machinery was kept warm. Fortunately for this, Strasbourg was prepared to set sail as soon as the first shells hit the pier. She was joined by an escort of five destroyers amidst the chaos, making a small but efficient task force in case of a battle with Force H. Modagor was the only one sank that day, her rear pulverized by a 16-in shell. Strasbourg miraculously escaped shells and magnetic mines previously laid at the entrance by Ark Royal planes.

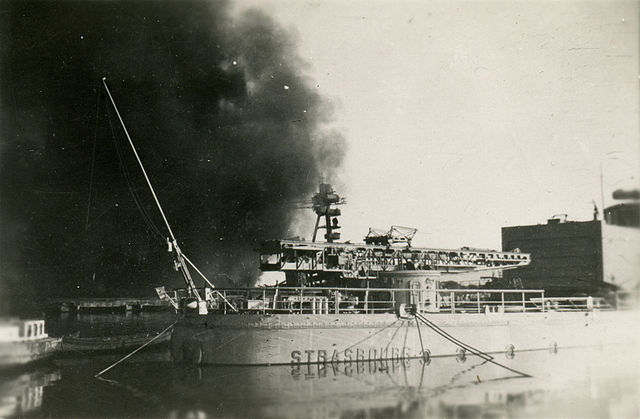

Strasbourg at Mers El Kebir, under fire – Author Jacques Mulard (cc)

Strasbourg was at sea, heading north-east at 28 knots, framed by the destroyers, which in case, could either lay smoke of distract pursuing British ships. Somerville indeed followed the actions closely and detached HMS Hood to chase the Strasbourg. It was even question of catching her with the Ark Royal’s planes, but distance grew as fast as light fell, and the whole pursuit was abandoned after dark. Indeed, Fairey Swordfish were indeed launched from Ark Royal, spotted the Strasbouth at full speed, but fail to placed themselves at a favorable position in order to launch a torpedo attack.

Strasbourg would head to the Sardinian coast before heading for Toulon that she reached the next evening. She had “only” five stokers died in a compartment, quickly asphyxiated by a smoke backflow caused by exhaust valves blocked by shrapnells. Needless to say, with only Strasbourg left, the 1st line division was dissolved and Admiral de Laborde on 25 September 1940 hoisted his mark on Strasbourg.

Flagship of the Vichy Navy

The proud battleship which skillfully and miraculously escaped hell at Mers el Kebir became the de facto admiral ship of the Vichy “high seas fleet”. Due to severe restrictions, notably of oil (reserved to the Axis), she was left at anchor and her only sortie sanctioned by the German-Italian armistice commission was in November 1940 to escort back to Toulon the battered battleship Provence, summarily repaired from Mers el-Kebir. In early 1942 however, Strasbourg became the first French warship to receive an “electromagnetic detection equipment”, in fact the first French radar.

The Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942, caused concerns for the fat of the fleet, now completed with the arrival of the Dunkerque, still in repairs at that time. German motorized divisions soon occupied the free zone and by November 27 made it into the arsenal of Toulon. Enough time has been spared to allow the fleet to be scuttled, 90 ships in total. Strasbourg was scuttled by opening sea valves and completed by demolition charges as the crew evacuated; It was still perilous as Germans troops and armored vehicles, including tanks, were now rolling in the arsenal in between the ships. It is reported that some gunners not only trailed, but fired at German vehicles as she sank, and that she was hit by a Panzer in return. The action saw 1 officer killed and 6 sailors wounded.

Strasbourg scuttled at Toulon (unknown author) cc.

The axis took possession of the arsenal, bitter as the scope of the loss and failure in their mission, but at the same time admitting the French “made their duty”. This fleet layong not deep into the port was too tempting to resist of course bailing out the last damaged ships. The more interested were the Italians, after crippling losses of the Regia Marina. They will indeed managed to refloat and starting repair several ships, but failed to have a single one back into service. Strasbourg was certainly the most tempting of these prizes and efforts were made to refloat the hull. But repairs stalled and she was eventually refloated on 17 July 1943, this time for scrap metal value.

Strasbourg after an air raid in Toulon harbor, short by USN reconnaissance 18 August 1944 (cc)

In Late 1943, the armistice came for Italy, and the Germans had nothing to make of Strasbourg, returned to Vichy authorities. Thoughts were made of sinking her at the entrance as blockship. The final chapter of this story came in August 1944 at the occasion of the landings in Provence (Operation Anvil Dragoon). Toulon was attacked by US aviation, hit by several bombs and sank again, on 18 August.

She was again refloated in 1945, and her rusted hull was towed off the Giens peninsula to be used as target, and for tests on underwater explosions. She survived and was left in the harbor to be eventually scrapped in May 1955.

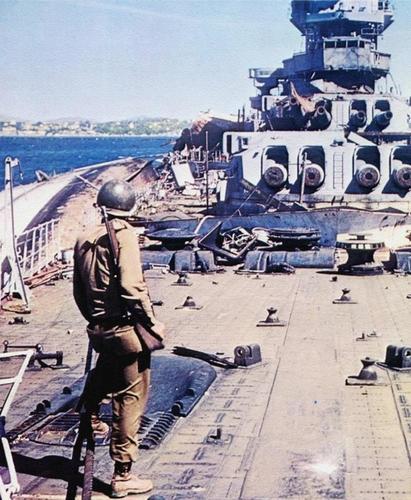

Strasbourg examined by US Troops in Toulon, September 1944. src ww2 in color

Characteristics

Displacement: 26,500 t. standard -36,380 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 215.10 m long, 31.10 m wide, 8.7 m draft.

Machines: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 6(32) Indret boilers, 135,600 hp. Top speed 31 knots.

Armour: 225-280 mm belt, 30 mm anti-torpedo partitions, 115-137 bridge, 330-360 mm turrets, 330 mm CT.

Armament: 8 x 330 mm cal.50 (Model 1931), 3 x 4 + 2 x 2 135 mm DP, 8x 37 mm AA, 32x 13.2 mm AA, 3-4 Loire 130 seaplanes.

Crew: 1380

Links, sources, read more

Conways all the world fighting ships 1921-1947

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunkerque-class_battleship

John Jordan, Robert Dumas- French Battleships 1922-1956

//forum.warthunder.com/index.php?/topic/492757-strasbourg-the-forgotten-sistership

Dunkirk with the Atlantic squadron in early 1940. src Alex. PL for Robert Dumas “Les cuirassés Dunkerque et Strasbourg” Marines Editions et Réalisations 1993- 24 November 2013 (cc)

Author’s illustration – The Dunkerque (“Dunkirk”) at Mers-el-Kebir, July 1940

Spectacular photo of the Strasbourg after the Toulon scuttling, with the port still burning – Anonymous, released under CC licence.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Finally! I really like this ship, thanks for writing the article. Nice work as always.

You’re welcome !

Indeed it was a starter for almost three years, rewriting long overdue. 🙂

Best,

Very interesting! Do you have dimensions for the Design A: 17,500 tonnes pocket battlecruiser (1926)? I have never heard of that design.

Hello D. Gregory

Nope, unfortunately interwar naval archives are notoriously difficult to obtain. Only some blueprints were released, and even them are no longer available on the official documentary service. In addition i think at this stage, the project was not developed enough to have precise specifications, this was “a general overview” before more development was done. You start generating precise specs when there is at least more precise blueprints. Tonnage, speed and armament are a general direction to follow, you have months of development before size specs are generated (unless they are dictated in advance by drydock dimensions)…

Best !