USA (1945)

USA (1945)USS Saipan (CVL-48), Wright (CVL-49) – service 1947-1980

WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classLight Carriers based on heavy cruisers

Two light carriers, Saipan (CVL-48) and Wright (CVL-49), were built for the USN during the war, and these were conversions, just like the nine Independence-class light carriers, based on cruiser hulls to gain a precious time in construction. However, they were not converted upon existing cruisers hulls, but just adopted these hulls to gain design time, and were built from the keel up as carriers using heavy cruiser hulls. However by the time their program was approved and construction launched, the context of the war already changed in the Pacific. Less an emergency program, the only two ships wre completed postwar after being suspended. Missing WW2 they still found use in various roles, as mixed heli-carriers until the end of the Korean War, then converted into a command ship (Wright) or major communications relay ship (Saipan) afterwards to fill these niche roles for the Navy and also take part in the Vietnam war, until the late 1970s, stricken in 1980.

Origin of the project

Their origin is not the same context that presided over the creation of the Independence class, but a prevision: This design was originally made to offset expected wartime losses of the Independence-class light carriers. They were were designed from the keel up as aircraft carriers, another big difference, and this time the Navy imposed the choice of a larger cruiser hull, the more suited Baltimore class. Plus they encompassed many improvements based on early experience with the Independence class. They were the prefect counterpoint of the earlier program.

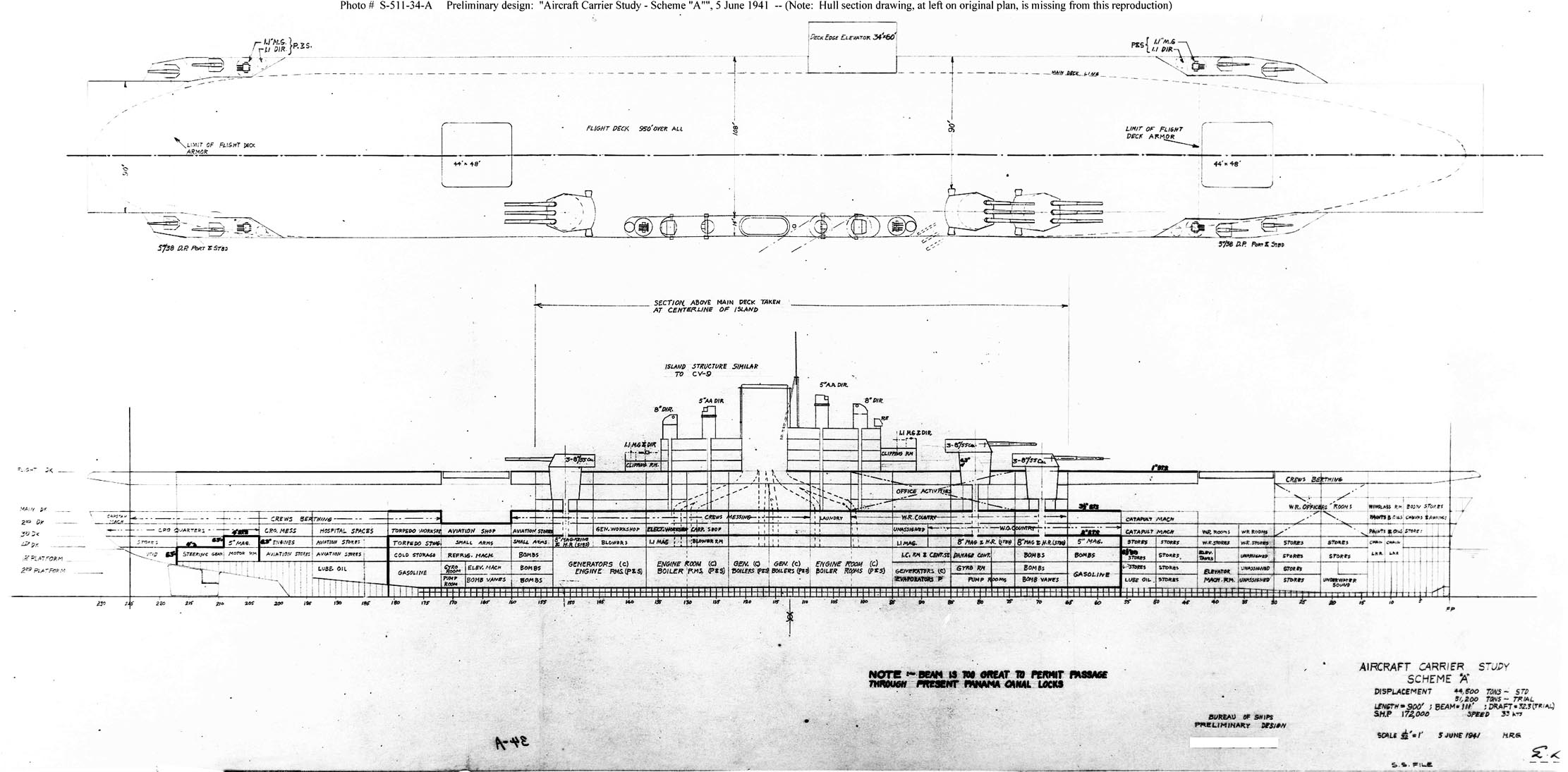

“A” scheme preliminary design study (Essex), June 1941: 44,500-ton, 900 ft, 3×3 8″/55 guns, 8x 5″/38 – navsource

Let’s remind a bit here: When WW2 broke up in September 1939, this had two consequences: Freeing parties of the tonnage limitations from the Washington treaty confirmed in London, and thus, giving the USN more leeway to go past their previous carriers class. Now freed in numbers (but not at first) and tonnage, the admiralty board asked for a design to succeed the 1936 Yorktown class, already the pinnacle of prewar carrier design. They suceeded to the rather mediocre USS Ranger with the perfect combination of speed, air group and self defence. But they were capped by tonnage, both in numbers and individually, in such a way the awkward choice was made to “liquidate” the remaining tonnage after USS Enteprise, too low for a siter ship, and create with it a “shortened” variant, the USS Wasp. As soon however as war broke up, a sister ship was added, USS Hornet, completed at breakneck speed in October 1941.

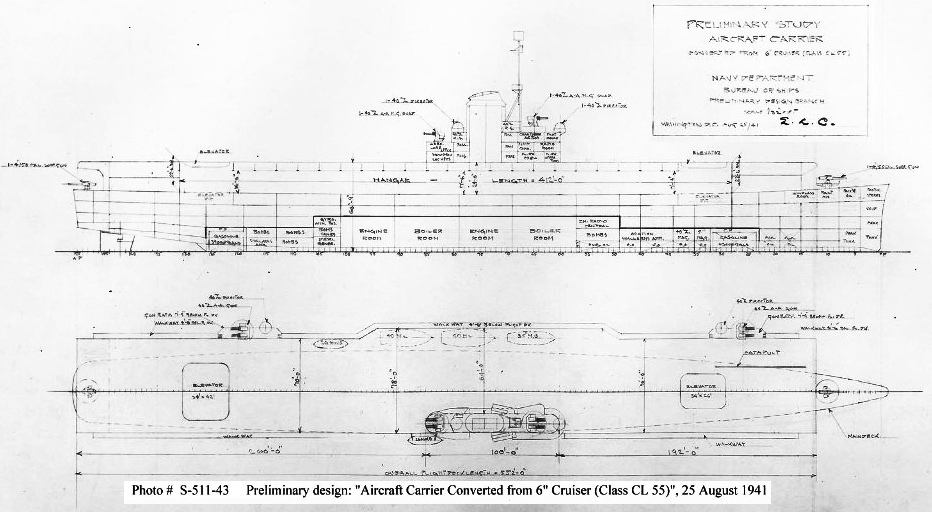

“Aircraft Carrier Converted from 6″ Cruiser (Class CL55)” S-511-43 Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board during the development of the Independence class small aircraft carrier design. This scheme, dated 25 August 1941, provides a flight deck similar in size to that ultimately adopted, with a larger hangar, smaller aircraft elevators, a conventional island and an anti-aircraft battery of four 40mm quadruple mounts.

So well before that in late 1939 the admiralty board looked at a successor class which would not be capped in individual tonnage as much and soon had to be capable to deliver a 100-plane flight in a short time, something later called the “sunday punch”.

Further refinements were made to the design that became the future Essex class, with some extra armour, a well thought protection overall, and new armament in the new 3-in/38 twin DP turrets.

The design progressed and the first hull was actually laid down …in March 1941. As a reminder, the US were still neutral at that point. The Congress was a hard time seeing any benefit in the construction of new carriers that fast. By December of course, thunderstruck at Pearl Harbour. The USN had a clear advantage in battleships before, more than three to one, to Japan, but was at disadvantage in aircraft carriers. Suddently there were no battleships available, and too few carriers already requested for the Atlantic. Suddenly new carriers were needed fast, fast, fast.

The Essex class were understood as perfect new fleet carriers, but they were large, complex, and would required years to completion. Most estimated a completion date ranging from December 1943 to December 1944 at best for the first three. With two “divisions” of three carriers each, plus the two Lexingtons, Admiral King estimated the Pacific was was still winnable.

USS Wasp, intended for the Atlantic, was recalled, and only Ranger stayed there.

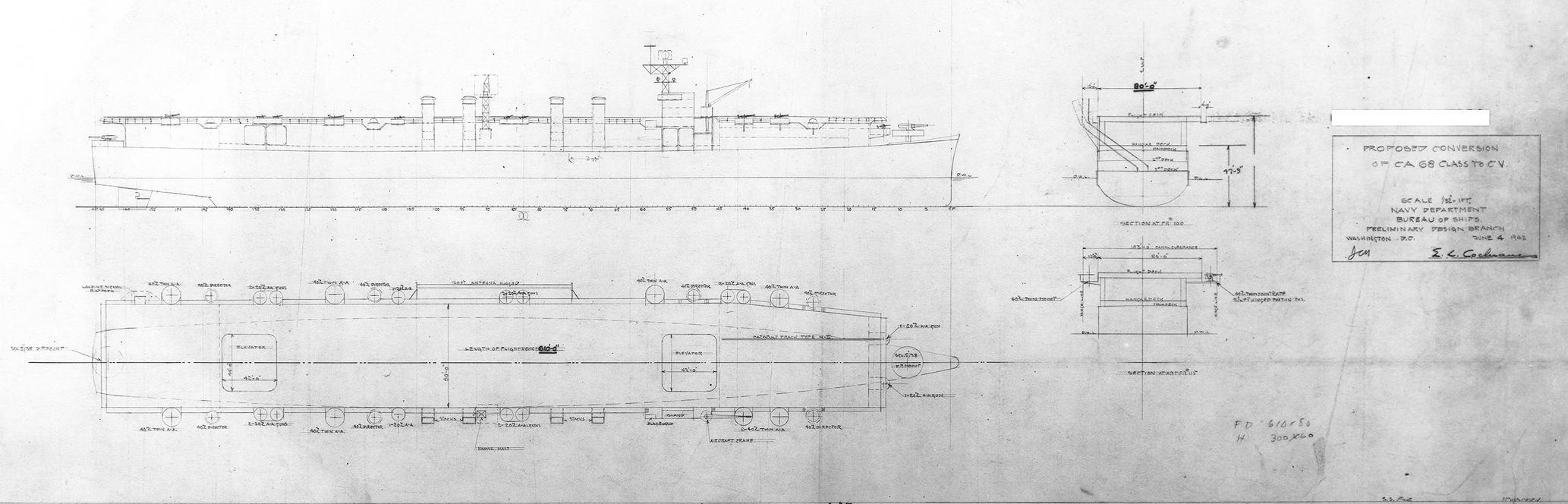

CVL S-511-54-A Proposed Conversion, Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board during consideration of aircraft carrier conversions of other types of warships. 4 June 1942, scale 1/32, Naval History and Heritage Command.

But there was still a gaping hole of 1.5 years without any new carrier in case there would be losses. The conversion idea went back to the summer of 1941, when president Franklin D. Roosevelt was suggested in July 1941 to convert existing hulls to gain time and completing in the matter of less than a year, perhaps as few as nine months, a whole fleet of new fast carriers. The solution was the same as for ships already converted for escorts missions in the Atlantic, USS Long Island (converted in 4 months) and USS Charger: Taking up an existing hull and building upon it, on paper, a hangar, a flight deck and a small island. It seemed feasible to shortcircuit the hull construction stage to gain time.

However converting a cargo is not going to deliver the type of fleet carriers the Navy needed, in air group or speed. Converting a liner was also an idea, and in fact the US just had a few of these mothballed at its potential disposal, including the recently acquired USS Lafayette (ex-Normandie). Some proposed it as a troop carrier and others as fleet aircraft carrier and it somewhat made some sense, but after gutting the interior, structures, etc. It was always better to built on a virgin hull, just launched.

There were not that many options in shipyards that filled the bill, but the newest, fastest ships large enough that could be “requisitioned” were the Cleveland class light cruisers. This was an enormous program in scope with 50 hulls ordered coast to coast. The president was suggested to requisition ten hulls for conversions, as it was reasoned that they needed to be more numerous to compensate for a smaller air group. The whole deal was about how fast they could be converted into fleet carriers. Some speculated five months was feasible. This was good enough for the presidnt to force the decision out, despite opposing voices in the navy arguing these would have such small air group as being “useless” in operation while pilots feared its flight deck would be too small and narrow for operations. But they were still aircraft carriers and could be obtained in a few months, instead of years for the Essexes. That was enough. If the Essexes completion was to drag on, it would have been easy to convert ten more hulls.

But at that stage, still before Pearl Harbor, there was still no emergency and on 13 October 1941, the General Board opposed its veto to the project. A new study was presented by Buships in Octpber 1941 and the president, tired of this opposition, and after Pearl Harbour, the tone changed completely. Admiral King greatly accelerated construction of the first three Essex-class carriers, wheras the new conversion gained all priority.

Already at that stage many in the board proposed to wait a bit and order these conversions on the new class hulls, offering more advantages. But they were overruled given the tight sechedule and large number of hulls available. USS Independence was renamed from USS Amsterdam, the requisitioned CL-59, laid down on 1st May 1941. USS Cleveland herself has been laid down back in July 1940 and would be launched in November 1941. Most of these would be built in New York. After the greenlight was given, nine more hulls were requitioned for conversion, with the important internal greenlight of Admiral King in January 1942, reviewing the plan favourably.

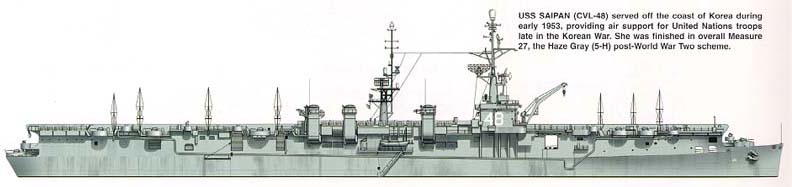

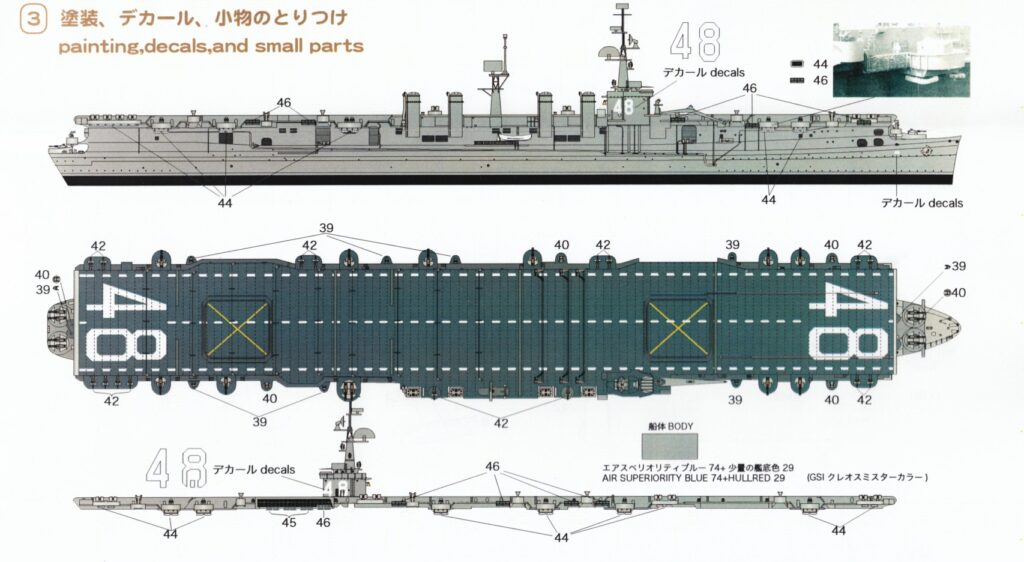

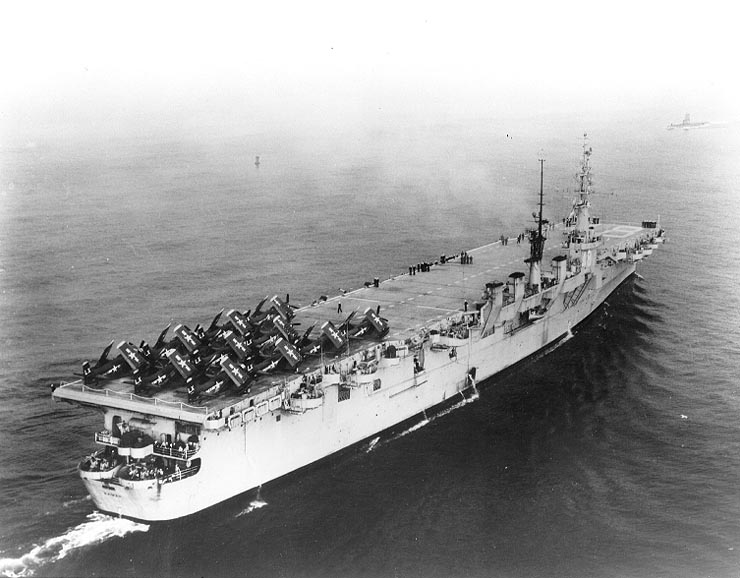

Illustration of the USS Saipan as she was in Korea, 1953

The end result was however, not as promising as expected. First off, the USS Essex were completed much faster than planned, completed symbolically the last day of 1942. It was now clear more would come in 1943 alone. Second, the Cleveland hull conversion proved more difficult than anticipated. Instead of the optimistic four months, USS Independence (CVL-22), launched in August 1942, was completed in December 1942 so in five month, but still needed many more to be commissioned in August 1943. These “interim carriers” arrived almost after the Essexes, not the scenario expected. In between between Coral Sea, Midway and Santa Cruz, the US carriers did far better than anticipated. Still, the situation was perilous as the Carolines campaign progressed: By late 1942, only USS Ranger was available, but she was deployed in the Mediterranea (Operation Torch), USS Saratoga was in repairs for a long tim, USS Lexington, Yorktown, Hornet, Langley (and Wasp in the Atlantic) were no more. That left only USS Enterprise to shoulder the whole Pacific campaign at this point…

The replacement carriers

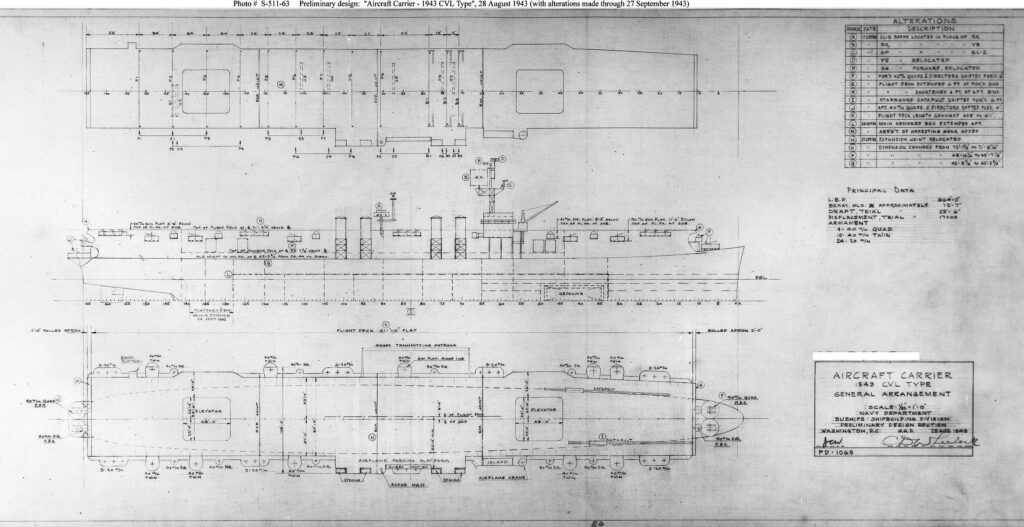

1943 CVL Type Preliminary design plan prepared during initial development, 28 August 1943. Alterations in 27 September 1943, 17,000-ton, 664-ft, 1/32 scale (Naval History and Heritage Command). src

Long story short, as soon as the Independence class conversion was approved, the board never really ceased to criticize the design but suggested nevertheless a planned replacement for the expected (heavy losses) in combat.

And they insisted upon it would be based this time on a larger, more sensible hull, while keeping the same concept of hull conversions in a few months. The new base chosen was of course the new heavy cruisers of the USN. A category that was “sealed off” since 1936 and USS Wichita, London treaty obliged. The Navy in addition wanted its new, fast-firing 8-in gun, but its development time meant the Clevelands would be ready much sooner. The first Baltimore class hull, a 14,000 tonnes standard design, was indeed only laid down on May 1941, so a full year after USS Cleveland. And the Navy needed its new cruisers fast to deal with the unexpected on the Japanese side, notably a long rumored “cruiser killer”. So that ruled out most of the earlier hulls…

Thus, the “replacement program” soon was postponed, until 1943. By that stage, the Essexes were practically there, as the Independences, and Admirall King revived the late 1942 Board proposal. Two new carriers would be built yearly based on his own estimations, to make up for potential losses of the class, which was less than initially feared. However even with approval, the new ships needed to be completed not later than December 1945. This left plenty of time to even start the hulls in the first place, given that in addition, since the yards building Baltimore cruisers all were intructed to complete these as cruisers, choice was made instead to just take the design and launch two brand new hull. The whole remaining of 1943 and most of 1944 were thus occupied in ironing out the designs issues of the previous conversions. Now, Independence class reports were piling up.

Construction and delays

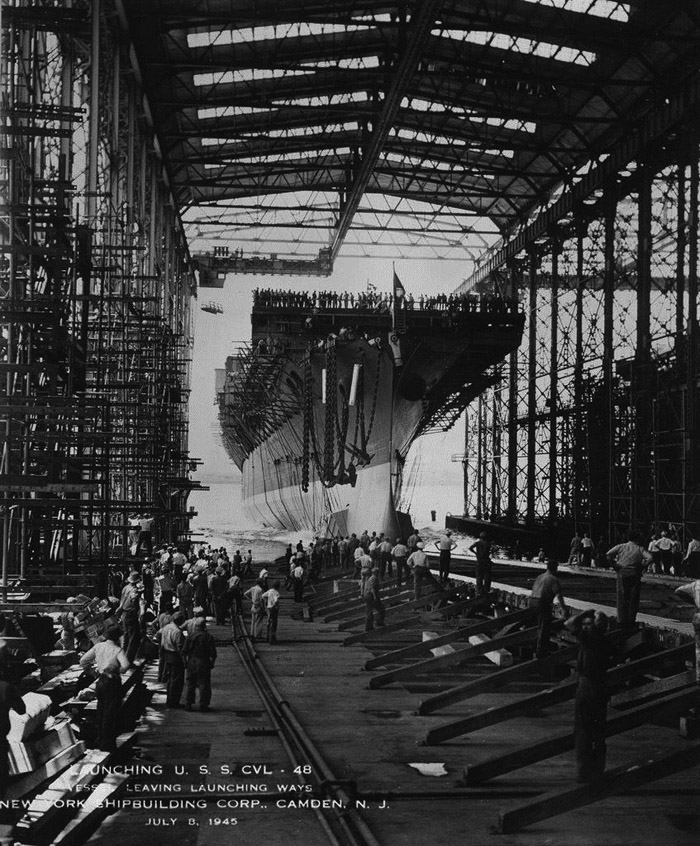

Launch of USS Saipan, July 1945. The war was still going on.

Eventually an order was placed at last to New York SB yard, the very same experienced by producing the bulk of the Baltimore class. But due to overload, they keels had to way further to be laid down, in July and August 1944 at last. At that stage the design was now fixed, enriched by all the adjustments made after plenty of experience combat reports. By late October 1944 after the Battle of Leyte, more crucial data was provided after notably the loss of USS Princeton and heavy damage on others, such as USS Belleau Woods.

This helped adding more safety features as the ships were completed. The problem was, they were launched respectively (USS Saipan and Guam) in July and September 1945, almlost a year since keel laying, which was way above average and simply reflected the activity at the yard. There simply were not enough resources or workers on hand, and the program was hit by a lower priority. De facto, if USS Saipan still could be completed by December 1945 by some miracle, it was out of question for her sister. Still, the end of the war even in August seemed a long way away.

The Japanese surrender of course, on 15 August, changed everything. The secretary of the Navy was now asked to axe all ships in construction for programs that were no longer relevant. Ships just arrived badly damaged were not repaired and secheduled for decommissions and all yards had to send reports on construction progress of various ships. There were hundreds of hulls in construction, ranging from the Midway class carriers, to the USS Kentucky battleship, cruisers, light and heavy, AA cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and escorts or all sizes.

Generally those close to launching were earmark for demolition on slip, those in completion, completed when practicable. As the war ended, previous shortages of personal even grew faster.

Program such as the “replacement carrier” were now completely out of touch with the new situation.

The Navy was left with two relatively small fleet carriers not completed yet, answering only a niche need and certainly not the best suited to follow the recent evolution in fighter bomber design and crucially, jets. Their initial design dated back from 1942 and little thoughts were given to the evolution of their air park. The optimistic figure of 48 (some even wanted 60) aircraft retained for completion data included the famous “troika” that ruled the skies for the USN: Hellcat, Helldiver, Avenger.

Their size and modus operandi was perfectly understood in minute details of handing and everything onboard was “calibrated” for them, from the hangar room to the lifts, catapults and deck space management. The figure of 48 in addition precised all those contained by the hangar alone, not even considering deck planes. Many found it feasible to launch a 70-strong air strike in two waves, starting with 20+ parked on deck, completed after lifting up the rest. This was not that bad compared to an Essex “sunday punch”.

Commission ceremony, USS Saipan

But after the war ended of course priorities completely changed. The whole doctrine manual for these ships, as they had been intended to serve, was good for the trashcan and the Board needed to reflect on several points:

-Was the class even worth the cost operating for what they brought on the table

-Could their air group be upgraded

-If not, could they be useful for something else

These point would haunt the early cold war years of these unfortunate ships. Needless to say, no such points were discussed for the equally late Midway class. Given their immense size (early estimates 130 aircraft !), there looked like the future. In comparison the Saipans looked like the unwanted ugly ducklings.

Design of the class

USS Saipan, general appearance early in her career (before the removal of her 20mm guns). Color Boxart.

The Saipan class was based on the hull and machinery of the Baltimore-class heavy cruiser hull, rather than Cleveland-class light cruisers (base for Independence class). This allowed better seakeeping, improved hull subdivision, enhanced protection and greater magazine volume, but also stronger flight deck as well as larger hangar for expanded air group and even a slightly better speed Compared to the Independence.

Unlike the Baltimore class, their hulls were made without bulges however, and protection was modelled after the Essex class, stronger than on Baltimore.

The 8 feet wider beam just were more suited to cope with the added weight of the hangar and flight deck; they made more sense at all levels for a conversion.

The Flight deck measured 186.2 meters long (611 ft) for 24.4 meters wide (80 ft), representing a 4,543 m² area (50,000 ft sq). This flight deck was strengthened to take 9 tons (18000 ibs) aircraft.

The hangar measured 86.6 meters long (284 ft), 20.7 meters wide (68 ft) and 5.4 meters high (17.7 ft). In surface, it represented 1,793 m² (19,300 ft sq) and 9,680 m³ (341,800 ft cu) in volume. There were two lifts in center line, each squarish at 14.6 x 13.4 meters (50 x 44 ft) and rated to lift a 13.6 t (27,200 ibs) aircraft. Forward were installed two H2-1 catapults. Inside the hull, several tanks enabled a total fuel stowage of 543,100 liters. Shortly after completion, their H 2-1 catapult was replaced by a 1 H 4B catapult.

And there was the new island, similar to the Commencement Bay class which was designed earlier. It had three enclosed decks and an open one used as main bridge, covered with a light structure.

On top was a small structure, and behind a massive metal mast, with a conical base, instead of a simpler lattice. There was an internal ladder to access the platforms above.

In 1945, this main mast supported two light projectors, a main navigation radar aft, an upper platform with an aerial radar forward with height finder, navigation radar on a pole, surface radar and various antennae. An aft mast was also built, which was a difference with previous designs, a bit further aft on deck, in between funnels. It supported the main long range aerial radar and two fire control radars on the fore mast built atop its main platform. This was the most extensive mast plan of any of these “light carriers”.

It diverged from the 1943 planned original, which presented a lattice mainmast instead, main aerial mounted on it, then a small aft mast anchored on the side, also between funnels, with lighter aerials.

Hull and general design

USS Saipan in 1956

The carrier as completed was almost closer to USS Ranger in displacement at 14,500 tons standard, 19,000 tons full load and longer at 664 ft (202 m) at the waterline, 683 ft 6 in (208.33 m) overall with a shorter flight deck at 600 ft (180 m) (fd). This lack of overhang limited the capabilities of the deck but allowed to fit extra AA at the bow and stern. In beam the class reached 76.8 ft (23.4 m) at the waterline and 115 ft (35 m) overall for a draft of 28 ft (8.5 m). The crew comprised 1,700+ officers and men initially, went up to 1850 and then down to 1317 (plus 522 flag as CC2) after command ship conversion.

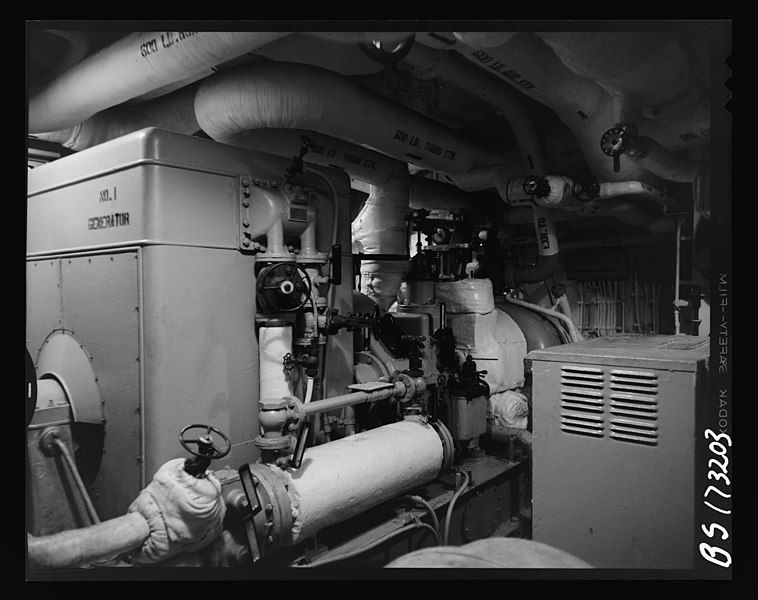

Powerplant

Close View of the truncated funnel after refit, 1956

Same powerplant as the Baltimore class cruisers, two General Electric geared steam turbines producing 120,000 horsepower on four drive shafts, four propellers. They were fed by the steam from four Babcock & Wilcox superheating boilers. The powerplant was maintained for all their career, but in the end, they experienced the same issues of personal skills as other ships of that generation like the Iowa class battleship, albeit these machinery were better known: The Baltimores were declined into the Boston and Albany classes missile conversions and in service as long.

Top speed was 33 knots (61 km/h). They were perfectly able to fit in the fast carrier force in 1945.

Armament

40 mm quad mount training, 1946

At this stage, it was envisioned, even in the 1943 blueprints, not tou mount 5-in guns. For simplifications, and in space available, it was found more sound to only use 40 mm Bofors, in quad and dual mountings as primary defence. Indeed instead of a single 5-in/38 fore and aft (which in 1944 proved to have fuses issues when dealing with Kamikaze), two quad 40 mm mounts were installed. Firepower by square feet was far more efficient. There was a single more quad mount aft of the funnels, starboard. The remaining 11 dual mountings were placed all along the flight deck port and starboard. This was completed by sixteen dual 20 mm guns AA. 12 were mounted in two six mounts platforms at the edges of the landing deck. However the latter were promptly removed as judged obsolete against new aircraft types. They were retired in the 1950s.

Later as AGMR2 she received four twin 76mm/50 Mk 33 and her whole Bofors array was removed but as CC2 she still had four twin 40mm/60 Mk 1 Bofors. In complement she carried 6 helicopters (3 CH-46, 3 HH-43).

The whole AA defence in shooting drills, 1947. Note the folded wings TBM avenger on the left.

Protection

It was inherited from the original design, and consisted in:

4-in (102mm) belt, closed by same thickness bulkheads, main deck, in STS (Special Treatment Steel). The steering gear compartment was protected by and extension of 4-in (102 mm) belt and bulkheads, and it was topped by a 2.5 inches (64 mm) roof and 0.8-in (19 mm) deck. The main bulkheads over main deck were down to 2-in (37 mm). The light underwater protection system was inherited also from the Baltimore class design and able to stop a torpedo blast.

Sensors

USS Saipan’s island, early in her career

Both carriers were completed at different dates and so were equipped with the best postwar radar suite, differing between themselves:

CVL48 Saipan had the SP, SK-2, SG radars and the TDY ECM suite. CVL49 Wright had the same SP, SG radars and TDY ECM suite but also the SR and SR-2 radars in place of the SK-2.

At the end of the 1950s bot carriers underwent a major upgrade: Sixteen 20mm/70 Oerlikon were removed as well as their SK-2 radar, TDY ECM suite and fore funnel was removed. Both received the same updated electronics suite: One SPS-6 radar and one WLR-1 ECM suite.

Of course on the long run, this will changed considerably. After conversion into command ships, a brand enw suite was installed (see career).

Air Group

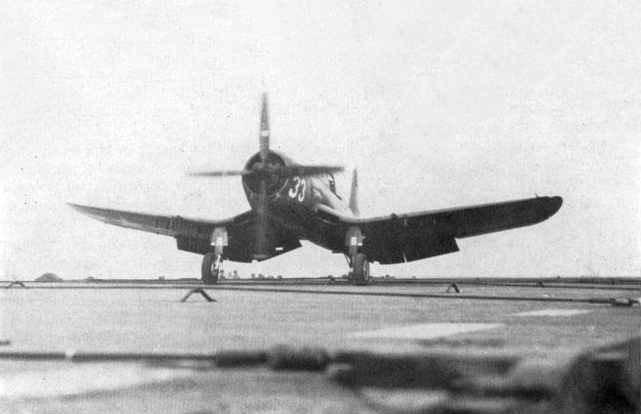

F4UB Corsair, first landing on USS Saipan, 18 August 1946

Planned complement of 48, then back to 42 aircraft in 1945:

-18 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters

-12 Curtiss SB2C Helldiver scout-bombers

-12 Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo planes

It is generally assumed in 1946, her sister Wright also carried a total of 36 F6F and F4U fighter bombers, 12 TBM Avengers for antiship and ASW purposes.

The carriers operated (often only for qualifications or tests) also the F7F Tigercat, FR Fireball, F8F Bearcat fighters, reconnaissance variants F4U-P Corsair, F6F-P Hellcat and F8F-P Bearcat and ASW models such as TBM-S/TBM-W Avenger and the TBM-R Avenger cargo.

Her and her sister also operated the Douglas AD Skyraider and AD-Q Skyraider.

F8F Bearcat from VF-1L lands aboard Saipan in 1947.

Grumman F8F Bearcat, VF-1L, USS Saipan 1947

Douglas AD Skyraider, VA-1L, USS Saipan 1948

McDonnell FH Phantom, USS Saipan 1948

The FH Phantom made its combat debut for catapulted launches and recoveries qualifications on USS Saipan. She made her firsty carrier launch earlier on 21 July 1946, from Franklin D. Roosevelt, without catapult. A bit forgotten today, the “first Phantom” (before the famous sixties F4 Phantom II), was developed from 1943 as quickly and simply as possible for mass production. It looked like a lot a Navy variant of the Lockheed P80 Shooting Star and it seems both services were in competition on that matter. The latter had beaten the second as for its first flight, 8 January 1944. The first XFH-1 flew on 26 January 1945. But despite its simplification, there were tons of issues to fix before service introduction, in 1947.

It’s really in 1948 that production commenced, and ended quickly, after 62 produced. It was discarded in the US by 1949 already, considered obsolete. Compared to the new F-86 Sabre and navy projects with swept wings at the time, it certainly was the case.

⚙ Specifications 1945 |

|

| Displacement | 14,500 standard, 19,000 tons full load |

| Dimensions | 664 ft wl/683 ft 6 in oa x 600 ft x 76.8/115 ft x 28 ft (208.33x 23.4/35 m oax 8.5 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts GE TED, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 120,000 shp (90,000 kW) |

| Speed | 33 knots (61 km/h) |

| Range | |

| Armament | 42× Bofors 40 mm guns (5×4, 11×2), 16×2 20 mm AA |

| Armor | HT steel belt 102+16mm, bulkheads 102mm, main deck 64mm |

| Air Group | 42: 18 F6F Hellcat, 12 Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, 12 Grumman TBM Avenger |

| Sensors | SP, SR, SK-2 SR-2, SG radars, TDY ECM suite |

| Crew | 1,700+ officers and men |

Cold War Conversions

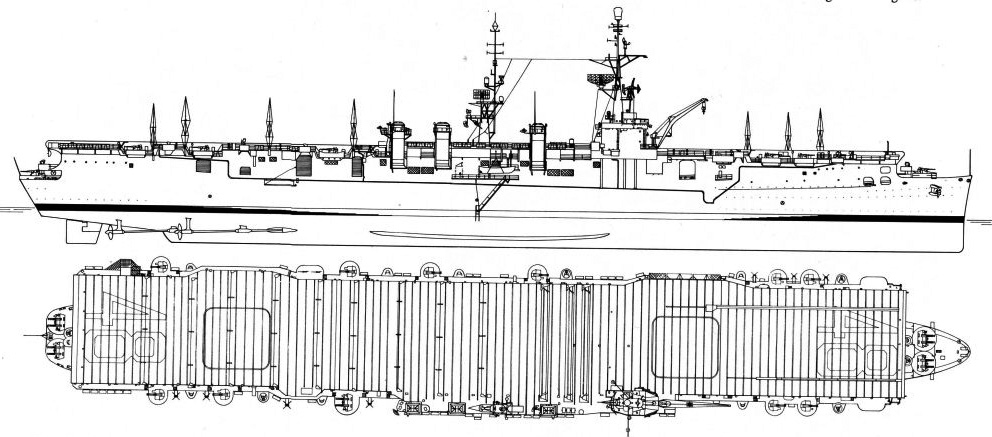

USS Wright as CC-2

In 1961 the admiralty board estimated that the new Soviet SSBNs presented a threat great enough to make traditional land-based US command centres insecure, likely first targets in war. The Navy thus proposed a floating command center, being permanently moved off coastal areas. In an emergency the President could also be carried aboard thanks to their large flight deck, and the ships would have all the facilities of a ground base to communicate with all military branches. The key technology there was a newly developed tropo-scatter radio.

Under FY62 program, USS Wright, now obsolete as carrier, was rebuilt as the command ship CC2, acting under the National Emergency Command Post Afloat (NECPA), and caracterized by its large antenna farm. Plans to convert Saipan as NECPA ship CC3 after CC1 Northampton was cancelled since the Vietnam war disctated tthe use of a second major communications relay ship, to relieve USS AGMR2 Arlington. However by the spring of 1970 a reevaluation of operational Soviet strategic submarines in the North Atlantic changed the balance and attention turned to airborne command posts instead.

Read More:

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ship 1922-47 and 1947-95, US section.

Naval Historical Center (27 October 2001). “Saipan-class small aircraft carriers, (CVL 48-49)”. Washington, D.C. U.S. Navy, Naval Historical Center.

Links

navypedia.org/ us_cv_saipan.htm

ibiblio.org/ s511-cv.htm

ibiblio.org/ cvl48cl.htm

navsource.org/

wearethemighty.com/ heres-the-navys-plan-for-light-carriers/

thoughtco.com uss-saipan-cvl-48-4034651

navysite.de/ cvl48.htm

navsource.org/archives/02/48.htm

en.wikipedia.org Saipan-class_aircraft_carrier

commons.wikimedia.org/ Saipan_class_aircraft_carriers

Videos

Model kits

picccc

USS Saipan

USS Saipan

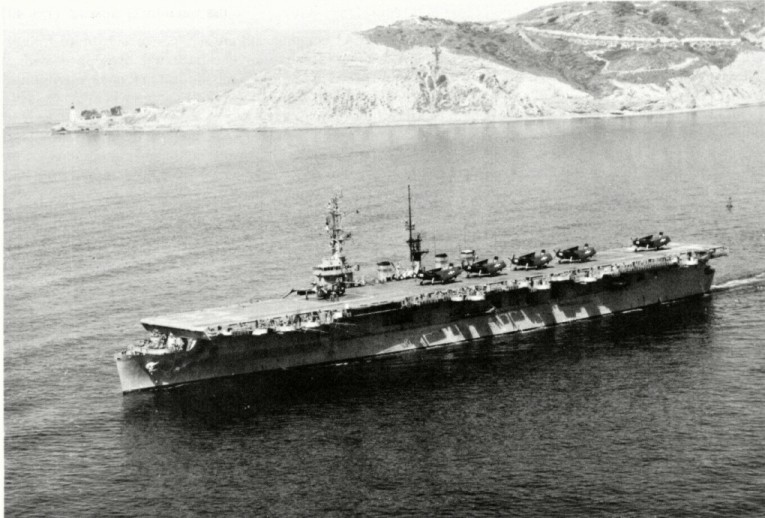

USS Saipan in initial shakedown training, Gulf of Mexico 1946

USS Saipan was laid down on 10 July 1944 at New York Shipbuilding Corp. Camden in New Jersey. She was launched on 8 July 1945, commissioned on 14 July 1946 under command of Captain John G. Crommelin. Having no longer an active purpose, she at least trained student pilots out of Pensacola in Florida, the latter landing and taking off with AT-6 Texans. This went on from September 1946 to April 1947. Afterwards she was reassigned to Norfolk in Virginia which became her homeport for a cruise on the Gulf of Mexico, exercises in the Caribbean and back to Philadelphia for overhaul. By November she returned to training midshipmen in Pensacola and by the fall of the year in late December she returned to the east coast and joined the Operational Development Force.

In February 1948 she started a serie of jet operational techniques platform and for carrier support tactics. She was also used for electronic instrument evaluation. 7-24 February, she was requisitioned to carry the Venezuelan Presidential inauguration and back. After exercises on the Virginia Capes she sailed in April to Portsmouth and returned to the Operational Development Force. On 18 April, she relieved USS Mindoro as flagship, CarDiv 17. 19 April, saw her leaving Norfolk for Quonset Point in Rhode Island. On 3 May she received the Fighter Squadron 17A, and performed squadron pilots qualifications with the new FH-1 Phantom. This was taunted as the world’s first carrier-based jet squadron.

FH-1 Phantom with folding wings moved around by a tractor, 1948

At Norfolk she was relieved as flagship and by June, returned to the east coast, and was overhauled in July at Norfolk until December. On the 24th she embarked two squadron of XHJS-1 helicopters and three Marine Corps HRP-1 helicopters to Greenland, rescuing 11 airmen downed on the ice cap, proceeding from Cape Farewell, launching the helicopters in a brieg good weather window. In between, a Navy C-47 with JATO (jet assist takeoff) and skis landed and departed with the airmen.

On 31 December she was back at homeport for crew’s leave, sailing on 28 January 1949 south, Guantanamo Bay, Hampton Roads (10-19 March) development force operations, and reserve training cruise to Canada. In May she resumed work for the Operational Development Force, then August, a second reservist cruise in Canada, and also qualifying the first Royal Canadian Navy pilots in carrier landings.

CVL 48 with her FH-1 Phantom on deck.

Mediterranean:

November 1949 to March 1951 saw her on the east coast in various operating. 6 March 1951 she became flagship, CarDiv 14 and joining the 6th Fleet for three months for her first deploployment in the western Mediterranean until May and back on 8 June. Next she served on the western Atlantic up to Greenland, Second Fleet operations, midshipman cruises (summers 1952, 1953) and an overhaul.

Korea:

October 1953 she was ordered to the Pacific, San Diego on 30 October, Pearl Harbor, Yokosuka, and joining the Korean squadron supporting the truce agreement.

She was reassigned to TF 95 for coastal surveillance and reconnaissance south of the 38th parallel. January 1954 she detached her air group to support Japanese manned LSTs with Chinese POWs from Inchon to Taiwan. February saw her in amphibious exercises, Ryukyus and in Inchon at stand by to evacuate Indian troops from Panmunjom. March saw her supporting amphibious exercises in the Bonins.

Bringing AU-F1s Corsairs to Da Nang to be passed to French Aeronavale pilots, Indochina war.

Assisting the French in Indochina:

In Japan she embarked 25 F4AU Corsairs, 5 H-19A helicopters at Yokosuka and on 18 April, VMA-324 pilots landed at Tourane (Da nang Air Base) to reinforce the French Aéronavale in the dyring days of the siege of Dien Bien Phu. The pilots leaved them to French pilots, but this was already too late. After offloading spares and maintenance personnel, USS Saipan sailed for Manila and on 20 April, delivered the five helicopters to the Philippines, then resumed operations off Korea. On 8 May she returned for R&R in Sasebo. On the 25th she sailed back to her homeport via the Suez Canal, completing her first world cruise on 20 July.

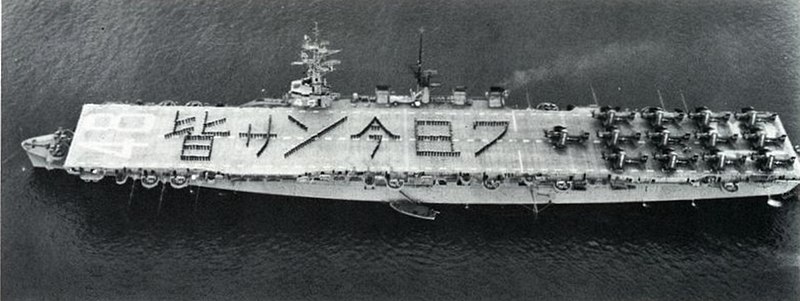

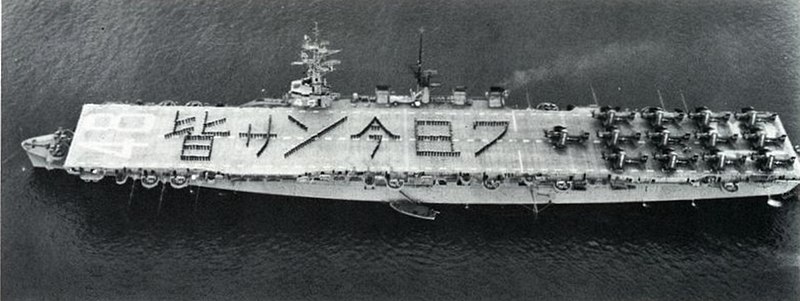

USS Saipan at Hong Kong and Nagasaki, Feb. and May 1954

Hurricane Hazel:

October saw Saipan ain the Caribbean when Hurricane Hazel struck the Greater Antilles, and she was mobilized for relief work from 13 to 20 October 1954 to Haiti, being thanked by the Haitian government. 1 November was the start of a new overhaul until April, back to the Caribbean. In June she returned to aviation training at Pensacola, for qualification exercises. In September she rushed for more relief efforts in Mexico after another hurricane, using in October, her helicopters for search and evacuation or landing rescue personnel and help, notably at Tampico. Back to Pensacola she stayed there until April 1957, with two training cruisers, 1946-1947, 1955–1957. Carrier pilots trained more on USS Wright, Cabot and Monterey. She was scheduled for inactivation, and sailed to Bayonne, New Jersey, being decommissioned on 3 October 1957. It could have been the end of her career, but the Navy still might have plans for her.

Saipan in 1954-55

USS Saipan loaded with helicopters, 1955

Conversion as a command ship:

AGMR2 Freshly converted, sea trials.

While in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, she was redesignated AVT-6 on 15 May 1959, and was mothballed until March 1963. When plans for conversion were ready she moved to the Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Co. in Mobile to become the command ship CC-3, and then the “Major Communications Relay Ship” AGMR-2, on 1 September 1964 and by 8 April 1965 USS Arlington (one of the US first radio stations) the conversion being complete by 12 August 1966. She was homeported back to Norfolk, recommissioned on 27 August 1966.

Fitting out took a while and she started by January 1967 a shakedown cruise in the Caribbean. February saw her in the Bay of Biscay (France-Spain) and northern Europe for NATO coordination exercizes until March. In April, Caribbean, Hampton Roads for last training. She was scheduled to join the western Pacific and the Vietnam war.

USS Arlington, interior details

USS Arlington in Vietnam:

Sailing out on 7 July 1967, via Panama, Pearl Harbor, Yokosuka, Subic Bay, she teamd with USS Annapolis on station off Vietnam. Her first mission in the Tonkin Gulf was from 21 August to 18 September 1967, doing message handling for the 7th Fleet as part of combat support, and sailed out to assit shios with their communication suite, having a worskhop facility and specialist. Given her deck she could also lift off the electronic equipments from ships to ships. In the Philippines she received a new satellite communications terminal. On 2 October she sailed to Taiwan, stayed three days, and returned to the Tonkin Gulf until swapping to the “Market Time” area, South Vietnam and 34 days on station. Sailored enjoyed 5 days R&R in Hong Kong and back to Subic Bay, then back to the Tonkin Gulf by December 1967 “Yankee Station”. On 27 December she sailed north in January 1968 to Yokosuka and back in actuion on 19 January.

Her mission at Yankee Station was interrupted for exercises in the Sea of Japan. The second station was from 13 February to 10 March and bac to Yokosuka, then resuming her mission in April. She departed to visit Sydney and was back in mid-June 1968. 20-22 July she had R&R in Hong Kong and was back to Yokosuka. By mid-November 1968 she completed two more Yankee Station mission and departed for Pearl Harbor in December, and there preformed communications tests.

Manned Spacecraft Recovery Force:

Her extensiove communication suite meant she could be used on another role: The space race. The USN was customary of “leasing” ship to the NASA program for various tasks. On 18 December, she departed Hawaii to join TF 130 mobilized for the Pacific Manned Spacecraft Recovery Force. She became its primary landing area communications relay ship for Apollo 8. She was back to Pearl on December 1968, then sailed for the Philippines and resumed her former job at Yankee Station by January 1969. In February she had upkeep at Yokosuka, trained off southern Japan, Ryukyus and R&R in March in Hong Kong, before resuming combat in Vietnam 6-14 April 1969.

She also tested her Apollo communications equipment and was back to Pearl Harbor, in May, she reintegrated TF 130, departing on 11 May in support for Apollo 10, joining the recovery area 2,400 miles south of Hawaii. Recovery was complete by 26 May. After a trip back to Hawaii she was redirected to Midway Atoll as communication relay ship for the Nixon-Thieu conference, 8 June 1969.

On 27 June 1969 she was back to Vietnam, but reordred on 7 July for Apollo 11 mission, arriving on 21 July, testing her equipment and sailing to Johnston Island. On 23 July, she embarked President Richard Nixon for a visit and on 24 July, supported the capsule recovery, then sailed for Hawaii and from there, Home via the west coast.

USS Arlington in 1966

On 21 August 1969 she joined her new homeport in Long Beach, then San Diego for inactivation. She was decommissioned on 14 January 1970, joining the Inactive Fleet before being stricken on 15 August 1975, sold by DRMS for scrapping on 1 June 1976. Despite she did not served in WW2, she won the WW2 Victory Medal anyway as well as the Navy Occupation Service Medal, National Defense Service Medal. But she also won for Korea, the Service Medal, UN Korea Medal and Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

After conversion as USS Arlington for her Vietnam service she won two Meritorious Unit Commendation with stars, two National Defence Service Medal with stars, then Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal and Vietnam Service Medal (7 campaign stars) as well as the Republic of Vietnam Meritorious Unit Citation (with Gallantry Cross) and Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal.

USS Wright

USS Wright

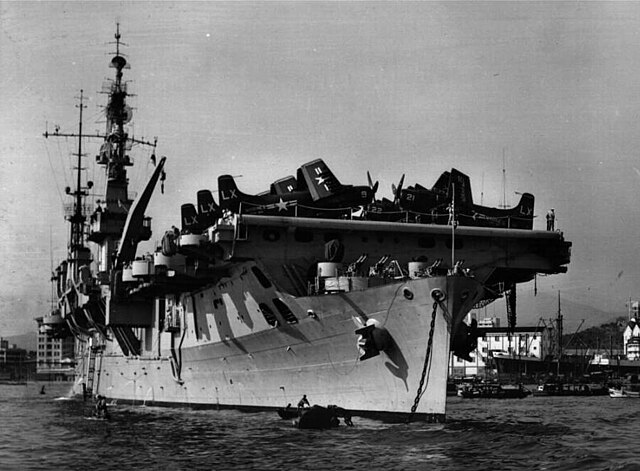

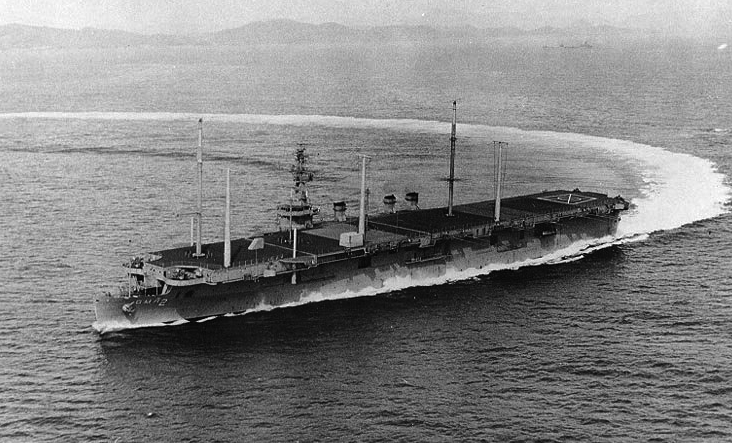

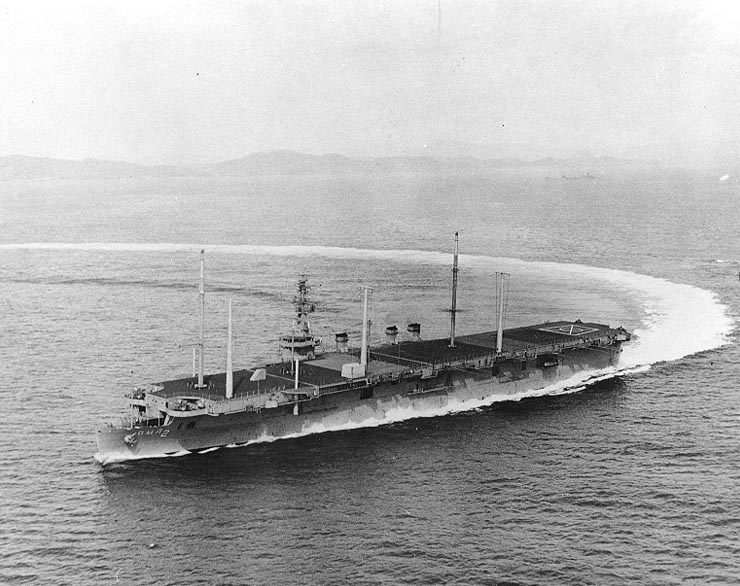

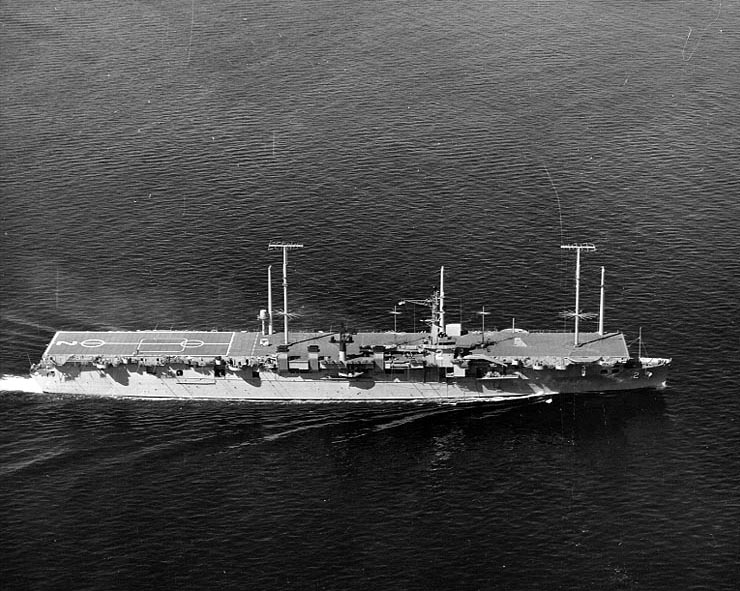

USS WRIGHT underway with AT-6 Texan training aircraft for initial carrier qualifications, 1947

USS Wright was laid down on 21 August 1944 in Camden (New York Shipbuilding Corp.), launched on 1 September 1945, commissioned ate Philadelphia on 9 February 1947 under Captain Frank T. Ward.

On 18 March 1947 she sailed to Norfolk, and NAS Pensacola on 31 March for air defense drills, gunnery practice, pilot qualification for the Base, relieving her sister USS Saipan. During her 40 short cruises off the Florida coast she presented various landing configurations and carried 1,081 naval reservists in three 2-week cruises.

On 3 September 1947 she had aboard 48 Midshipmen and later 62 Army officers on 15 October, sailing with USS Forrest Royal off Pensacola for landing/catapulting exercises with F6F Hellcats equipped with rockets. On 24 October she sailed to Philadelphia until 17 December for post-shakedown fixes and returned to Pensacola to resume work under the Chief of Naval Air Training for the Atlantic. Same in 1948 and a 4 months overhaul at Norfolk on 26 January 1949, relieved by USS Cabot.

F4U-5 Corsair of VF-23, Nov.1948

After a Cuban refresher training she was back in Norfolk on 1 August 1949, moved to Newport for ASW training in Narragansett Bay and visited New York City before returning to carrier qualifications, air defense tactics or exercises off Rhode Island or Key West and Pensacola. She trained with the 2d Task Fleet in October 1949 and by 7 January 1951 embarked the remainder of Fighter Squadron 14 (VF-14).

6th Fleet and Mediterranean service:

Mediterranean, 1950s

USS Wright sailed from Norfolk on 11 January 1951 with the fast carrier task group to Gibraltar and first 6th Fleet TOD. She stopped in Oran, Algeria, Augusta Bay, Sicily, Suda Bay, Crete and Beirut, Lebanon. While back she stopped at Golfe Juan in Franc and multiplied in between exercises with the 6th Fleet. On 19 March 1951, she departed for Newport.

She had an overhaul at Norfolk Naval Shipyard and when back, joined the Atlantic Fleet maneuvers off Cuba, ASW tactics, and carrier operations in Narragansett Bay, plus fixes at Boston Naval Shipyard. Next she was in a convoy exercise 25 February-21 March 1952 and sailed in the Panama Canal Zone and British West Indies.

She became flagship, Carrier Division 14 and sailed on 9-27 June 1952 with TG 81.4 for ASW exercises on the Atlantic seaboard. They all gathered afterwards at New York City. At Quonset Point she trained the Naval Reserve while practicing hunter–killer tactics/pilot training from July to 26 August. She met later VADM Felix Stump and his 2d Task Fleet for northern Europe and combined NATO defense exercises/maneuvers. She was detached, escorted by USS Forrest Royal she carried Marine Night Fighter Squadron (VMF(N)) 114 to Port Lyautey in Morocco in September. She was in the Firth of Clyde on 10 September.

She took part to Operation Mainbrace with the RN, with destroyers and the British carriers HMS Illustrious and HMS Eagle until reaching the Netherlands on 25 September. Four day later she headed back home. With RADM W. L. Erdman (Carrier Division 4) aboard, she spent weeks in carrier qualification from Newport to the Virginia Capes, followed by another run to the Mediterranean via Golfe Juan on 21 February 1953, until 31 March. Back home, she trained off Newport and Narragansett Bay, then the Gulf of Mexico and in Houston she hosted some 14,000 visitors in May. She later trained off Mayport.

Wright’s Pacific service

USS Wright and USS Leyte in Quonset Point

After a major overhaul at Philadelphia from 31 July to 21 November 1953, refresher training (4 January-16 February 1954) she left Rhode Island on 5 April for Norfolk, loading stores and supplies for her Pacific Fleet transit. She was in Panama on 20 April, and reached San Diego before proceeding to Pearl Harbor and then headed to Yokosuka, arriving on 28 May. On board she had Marine Attack Squadron 211, starting operations with the 7th Fleet off Korea, Okinawa before R&R in Hong Kong (24-30 September). She left Yokosuka on 15 October for HP San Diego, overhauled at Long Beach Naval Shipyard until 23 February 1955.

Attached to CarDiv 17, Pacific Fleet she stayed off California until 3 May before joining TG 7.3 (flagship USS Mount McKinley) escorting the atomic test fleet (Operation Wigwam). Back on 20 May, she sailed to Pearl Harbor and back for a final inactivation overhaul at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in July, then Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton (Washington) on 17 October for final long term preservation, decommissioned on 15 March 1956, Pacific Reserve Fleet.

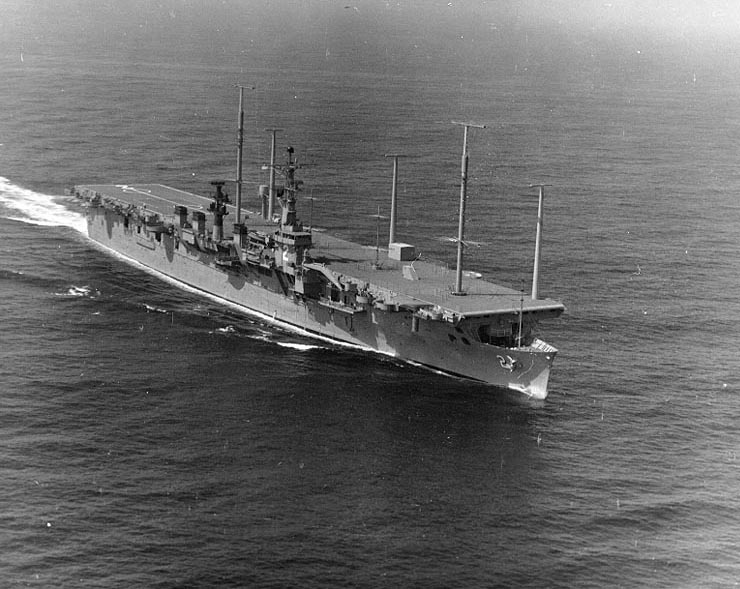

Conversion as command ship CC-2

CC-2 Wright in June-September 1963

USS Wright was reclassified on 15 May 1959 as the auxiliary aircraft transport AVT-7 but remained inactive, until 15 March 1962. At that stage it was decided instead to have her modernized and converted as command ship in Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. She was redesignated CC-2. The conversion lasted a year and her hangar wazs completely modified so she can serve as a mobile command post afloat, with large rooms filled with screens, maps, reunion rooms, pltotting rooms, early computers, and living facilities. She was to serve as a commands and staff ship, usabled for strategic direction and operations around the world, able to contact and coordinate any land, sea, air forces. Antennae were the only most visible part. Inside she had newly built communications means for rapid automatic exchange and processing but also storage and display of command data, with the technologies of the sixties. A whole area of the hangar was dedicated to special command spaces, extensive electronics equipment. The new, specially designed, massive communications antenna arrays were fixed on the flight deck, anchored through it down to the hangar. Facilities were provided on the remaininh hangar and deck space to operate three helicopters, mostly responsible of personal transport between land and the ship.

When recommissioned at Puget Sound on 11 May 1963 she was under command of Captain John L. Arrington II and started trials and training off the Pacific Northwest coast, until 3 September, departed Seattle for San Diego. Later for three weeks she trained there, and back to Puget Sound (30 September) for post-shakedown availability.

By November she was relocated to Norfolk, departing on 26 November, stopped at San Diego to carry engineers and personnel to complete calibration of her communications and-air conditioning equipment. While off northern Mexico she assisted the Israeli merchantman SS Velos, flying there a medical officer to treat a seaman suffering from kidney stones. Wright transited via Balboa and Panama on 8 December, St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, arrived at Hampton Roads Army Terminal, 18 December. She trained briefly at the Virginia Capes and spent Xmas at Hampton Roads.

For six years, USS Wright stayed off Norfolk, in constant drills to perform best in her task of National Emergency Command Post. She had several maintenance overhauls at Norfolk, with alteration to better perform. She sailed off the Virginia Capes, and to Bar Harbor in Maine, but also made cruises down to Rio de Janeiro or Punta del Este. She was a regular sight also at home, at Newport, Quonset Point, Jacksonville, Mayport, Fort Lauderdale, Port Everglades, Boston, Portsmouth, New York City, Atlantic City, Annapolis, Philadelphia, or Little Creek. She was in permanent alert status with USS Northampton (CC1), also a former Baltimore class cruiser based ship.

USS Wright in 1967

On 11 to 14 April 1967 off Uruguay she provided communication for President Lyndon B. Johnson Latin American summit conference, at Punta del Este. On 8 May 1968 she assisted USS Guadalcanal after her machinery failure off Norfolk. She would received the Captain Edward F. Ney Memorial Award for her largest mess afloat status, best food standards in the Navy also in 1968. She coordnated US response during the Pueblo crisis in February 1969 while off Florida.

However the strategic and tactical situation changed. In 1970 it was now clear that the first AWAC planes were as efficient, faster and cheaper to maintain than such a large ship. It was decided to have her decommissioned on 27 May 1970. Placed in reserve at Philadelphia she was stricken only on 1 December 1977, sold to DRMS for scrapping, 1 August 1980. She won less awards than her sister, but still, the Korean/UN/Rep. of Korea Service Medals and 2 stars for the National Defense Service Medal in her career as command ship.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

It would have been nice for the US Navy to have preserved at least 1 of the 11 of the Independence or Saipan Light Carriers or 1 of the 80 plus Escort Carriers. Some much history lost forever…….

Indeed, Dedalo was decom. 1989 but it’s always deficient support and finances that kills preservation projects (in that case in 1999).