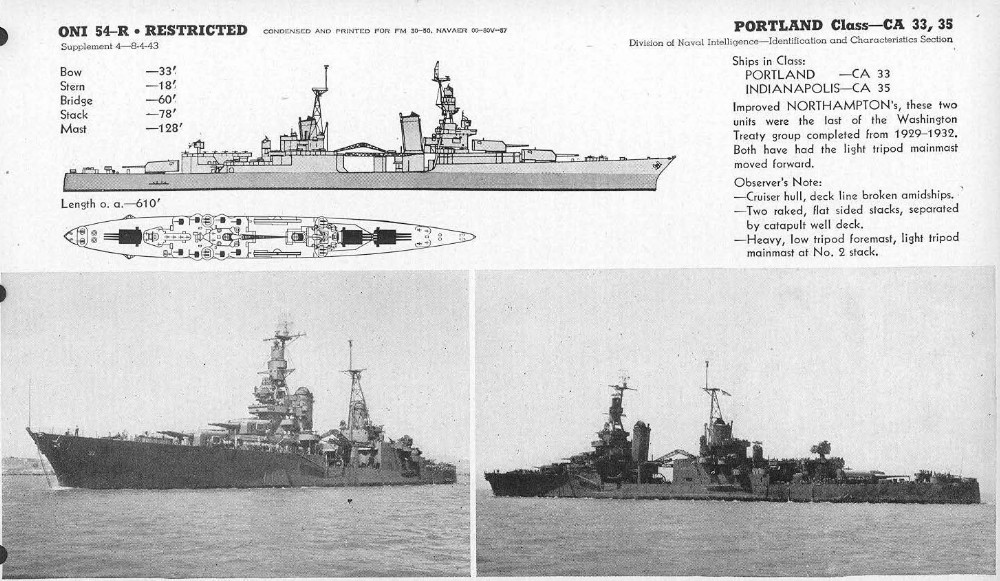

The Portland class: The 2nd generation.

Designed after the Northamptons, the two heavy cruisers Portland and Indianapolis were contemporary of the New Orleans class which still looked like the Northamptons. But in reality they improved on many points and especially that of protection, so much so that they are considered by most authors now like the “second generation” of american post-Washington cruisers, the third one being represented bu the Brooklyn/Whichita in direct line with the wartime cruisers (Cleveland and Baltimore).

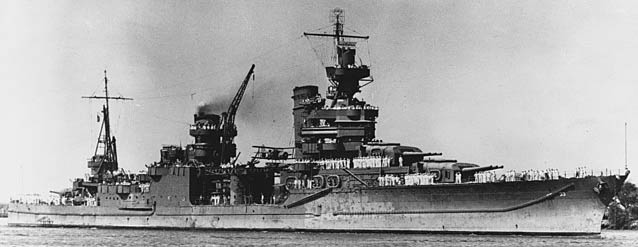

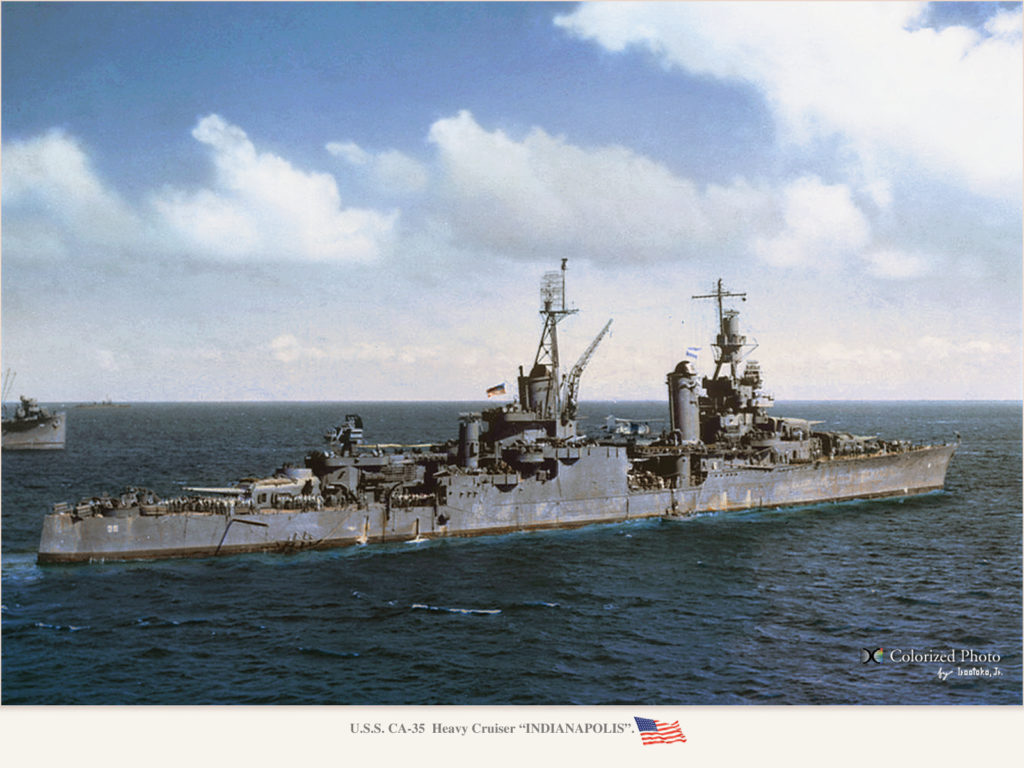

They were roomier, larger and much heavier than the Northamptons, with a tonnage fully exploting the treaty limit but in reality reaching 10,260 tonnes standard. There was no additional armor margin left within the treaty limitations for future upgrades, more than questions of stability. This impacted their AA upgrades notably, but they still fared well during WW2. Portland soldiered in the pacific campaign, making all the most important battles and being several times damaged, earning 16 battle stars before being discarded in 1959. She certainly was one of the most decorated, battle-hardened, long serving cruiser in USN history. USS Indianapolis on the other hand became (in)famous for being sunk by a Japanese submarine after delivering the Bomb A (“Little Boy”) at Tinian, on July 29, the last major warship to be sunk in WW2. Survivors were left stranded for days fending off relentless shark attacks, leading later to an inquiry.

USS Indianapolis at Pearl Harbor circa 1937

Design development

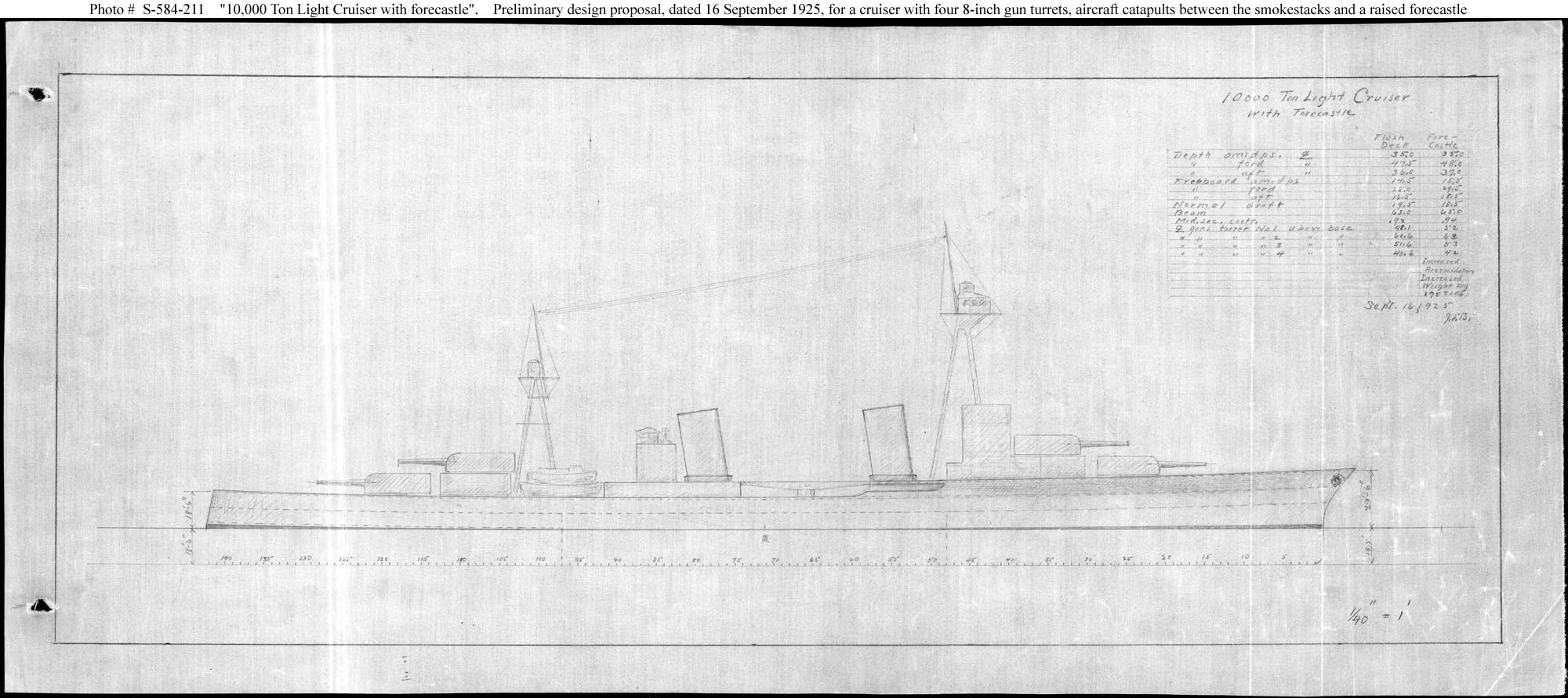

The initial early 1925 design study 9 about the forecastle variant of the Pensacola design, which led to the Northamptons. The next were an evolution of this.

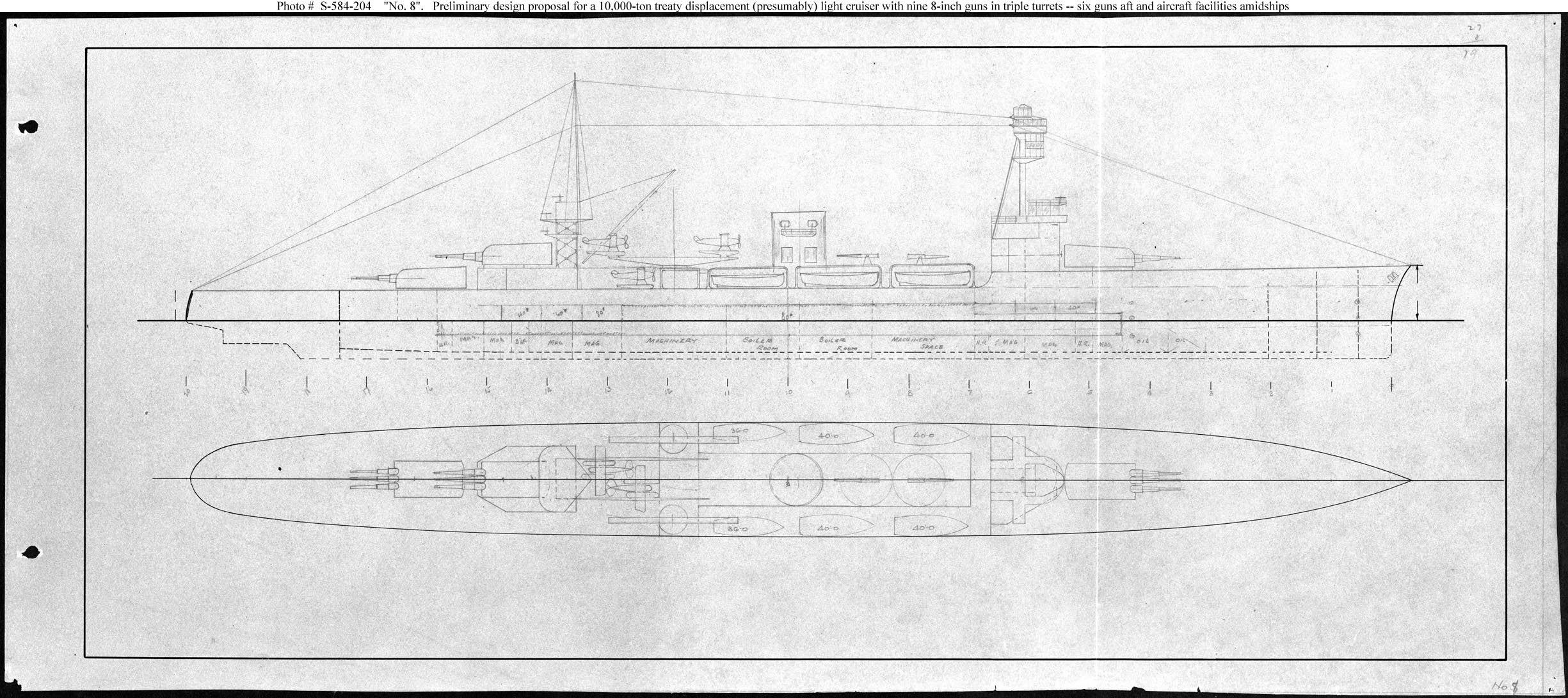

Another proposal of 1925, N°8 proposal with two aft 8-in guns turrets to improve on stability.

Just as the Northamptons design was approved, the admiralty board started right away to look at a third class of heavy cruiser. Years after the 1920s designs that led to the controversial Pensacola class (design finalized 1926) which emphasized armament and speed over protection and stability the six vessels Northampton class (ordered 1927) improved on many point already with a forecastle, better balance on many areas and better accomodations. But armor protectin was still a weak point in the design, and there was not much room for improvement over the waterline due to metacentric height issues. The configuration of three triple turrets was their legacy, and became a standard, likely to be retaken for the next classes. So the Portland class as initially defined was just an evolution of the Northampton designs, originally designated “light cruisers”, with the range to counter German-style commerce raiders.

They were quickly redesignated CA- (“heavy cruiser”) given the new 1930 London naval treaty adjustments for gun calibers. So the eght ships ordered on a simple early blueprint FY1930 as CL-33 and following, became CA-33 from 1st July 1931.

In all, fifteen 8in cruisers were authorised for the 1929 programme, Fiscal Years 29 (CA32-36), 30 (CA37-41) and 31 (CA42-46) and the original eight cruisers envisioned were close copies of the modified Northampton-class with just a few incremental changes from the experience gained in 1929, but only two ended with this design, called Portland class, since the admiralty wanted a radical departure over previous design and go back to a more heavier armor protectrion. So much so that these ships even were designated for a time “armored cruisers”. They becalme eventually the New Orleans class, with the remaining batvh of sis cruisers FY1933 and following. In fact the first three of these, USS New Orleans, Astoria, and Minneapolis were ordered originally as Portland-class but soon reordered on a design based on the new USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37).

Although the New Orleans really targeted protection and went to a radically new, smaller design, the Portland looked very luch like Northamptons, with very few immediately apparent differences. Indeed, the basic design was the same to gain time, but much time and effort has been deveoted for two years working o the protection scheme, notably by allowing almost twice as much weight to the armour, and thus, reaching the standard tonnage limit right away. It was not the case for the previous ships, barely above 9,000 tons.

The main reasoning behind the split between the first two (CA-33, 34) and the next six of the second group to be completely redesigned with better protection (criticism had been considerable, this weak protection seeping in the press which dubbed these Treaty ‘Tinclads’), as the first group was too far advanced to be modified when this decision was taken. A balance was made and the “Portlands” ended as interim cruisers in order to avoid creating a gap in the programme. The other reasons were the pecularities of procurement policy when ordering to admiralty (public) or private yards: Three of the first group were contracted to Navy Yards ans thus could be redesigned without incurring hard-cash payments unlike CA33 and CA 35 ordered from private shipyards. The on-cost would be ‘lost in the system’ as per the government’s use.

Design orientations of the Portland class

Thus, the two private yards Portlands (Ordered on 17 Feb and 31 March 1930 to Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation, Fore River Shipyard and New York Shipbuilding Corporation respectively) differed in many ways from the Northampton design which was kept as a basis. That why we lack the intermediate proposals and design schemes. Work was done on more advanced blueprintts, with just some upadtes communicated to the admiralty board. The original intention was to decrease the hull length by 10ft (8ft forward and 2ft aft) while keeping the internal arrangements, using the free weight to increase the magazine side armour to 5in and amored deck by 0.5in. The beam remained unchaged, but the bulbous bow would be eliminated to gain some weight again. The light splinter-proof gunhouses would remain the same also.

The problem of being underweight was now fully understood and measures were taken while the side protection of the magazines asked for was raised to 5.75 in, still possible as they laid low into the hull. Although still not fully immune to 8 inches shells, this seriously decreased the chance of a lucky hit. The side belt (2.25in) was thought to be increased by adding a layer, but later dropped due to cost issues, and still adding weight.

For the machinery Yarrow boilers were unsed instead of what was onboard the Northampton class, the armament was also a repeat but this time the torpedo tubes originally planned were eliminated well before completion. Also, this was compensated by the addition of four 5in guns (8 total), as were rearmed the Northamptons.

Like the latter, they had generous accomodation and two-tiered bridges to act as Fleet Flagships. The superstructures were still very similar, but the bridge was doubled by an open one with massive overhanging deflectors, keeping the crew from the spray and guns blasts. The front mainmast was made lower as the aft one, both were also lighter and cleared of spotlights relegated to the funnel to improve stability.

Hull & general design

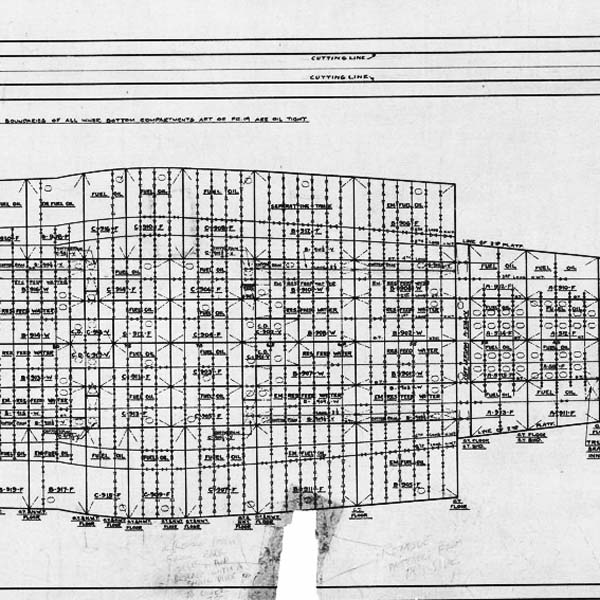

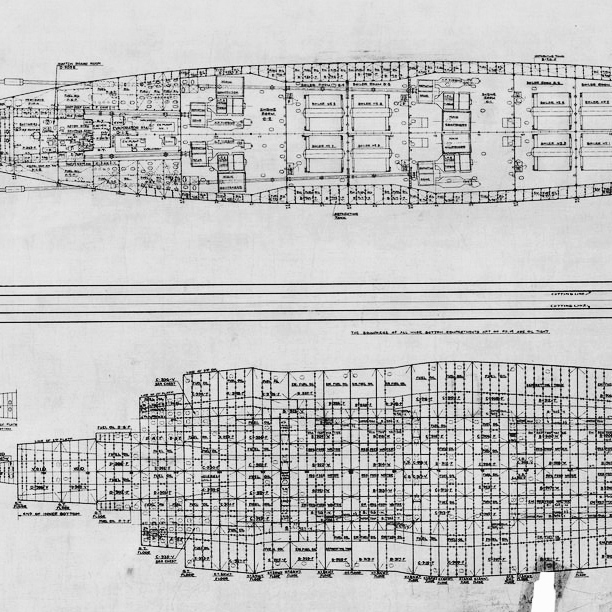

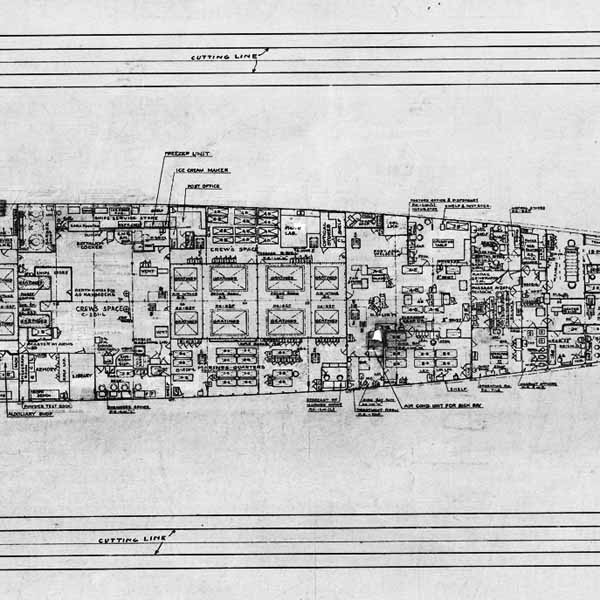

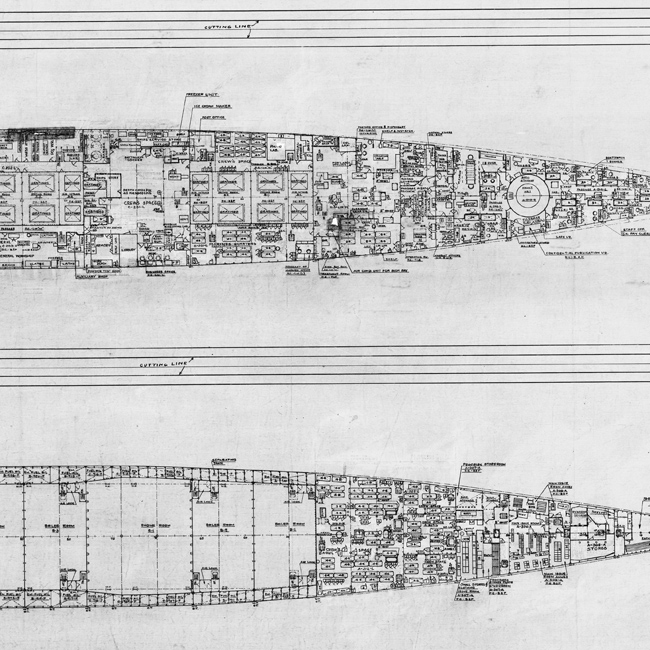

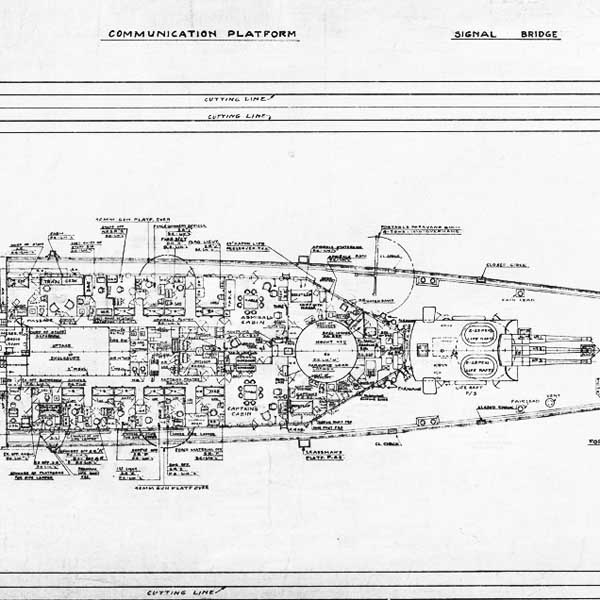

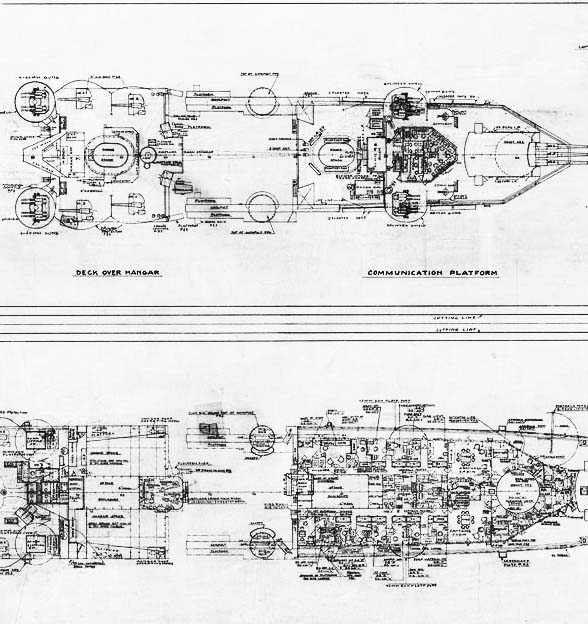

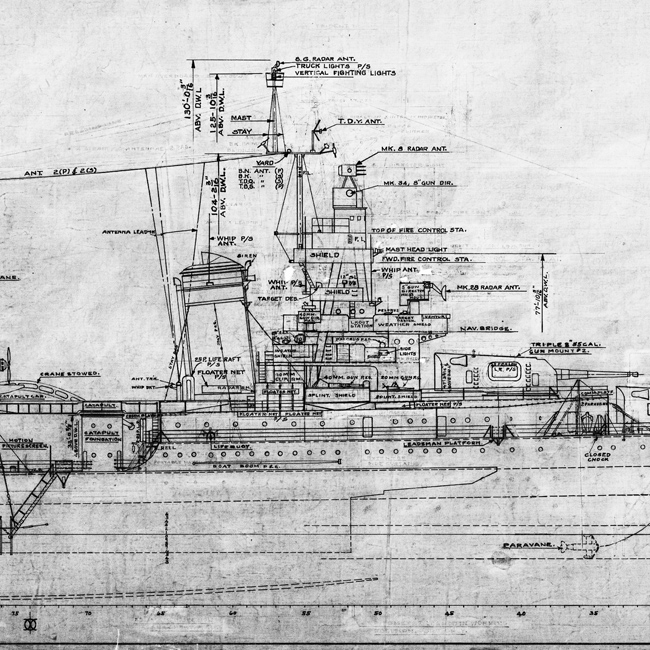

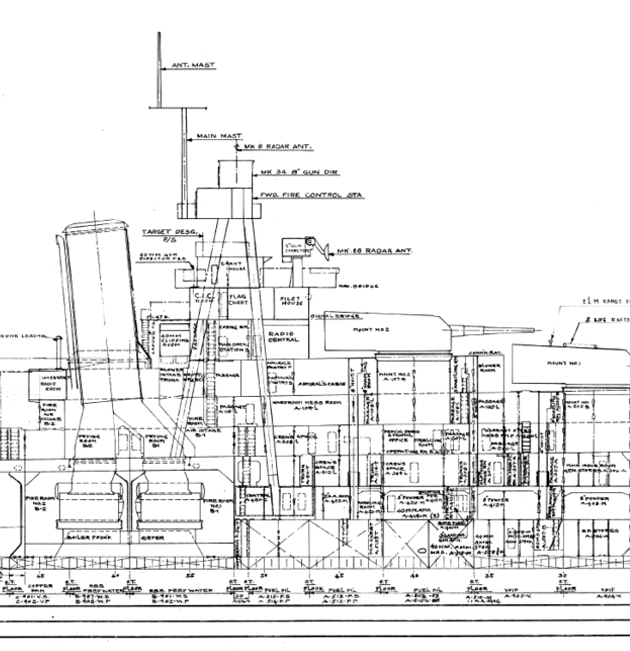

Ship’s original blueprints, signed 1932.

The Portland-class hull was 610 feet 3 inches (186.00 m) overall long and 592 feet (180.44 m) at the waterline, way more than the Portlands. The beam was ported to 64 feet 6 inches (19.66 m) slightly less than the northamptons at 66 ft 1 in (20.14 m), but making for a more lenght-width favourable ratio, therefore for a better to speed. Her buoyancy was supposed to be better as a result also, with a draft of 21 feet (6.40 m), up to 24 feet (7.32 m) deeply loaded, way more than the 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m) of the Northampton, compensating largely in terms of metacentric height and greatly improving stability. They also had a revised bow shape and extended forecastle, further improving sea-keeping abilities. The forward main tripod mast was also reduced in height and weight and there was single pole aft.

They were also designed for a standard displacement of 10,096 long tons (10,258 t), 12,554 long tons (12,755 t) fully loaded. As already stated before this was much greater than the 9,050 long tons (9,200 t) of the previous class, translated into 900 tonnes for more armour and structural strenght, but also counting the extra weight of the longer and drafter hull. Both were in any case, way more strongly built, a radical reparture over the “tin clad” generation, and yet not to the level reached in the New Orleans class.

Both ships however ended lighter than expected by the constructor, at 9,800 long tons and 9,950 long tons respectively. They still have the caracteristic two heavenly spaced raked funnels, a forward tripod foremast, and small tower bridge, pole mast aft. Top weight was therefore better mastered and distribited.

Powerplant

The Portland were equipped with the same powerplant basically, four propeller shafts drove by four Parsons GT geared turbines, in turn fed by eight Yarrow boilers. Total output was 107,000 shaft horsepower (80,000 kW) for a design speed of 32 knots (59 km/h). Range was 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at a cruiser speed of 15 knots (28 km/h). The previous Northamptons had Forster Wheeler boilers but very comparable performances. No significant improvement was made on this topic, apart range decreased (about 2000 nm) as well as top speed (0.7 knot) due to the added weight and deeper draft, compensated by the longer hull.

Both ships as completed however showed on trials they rolled badly, until fitted with bilge keels in drydock at the first occasion. This further improved stability and procured a roll compatible with a relatively stable gun platform. Over time, modifications made to made their superstructures lighter improved this, but only to compensate for the added weight of the wartime AA battery.

Armament

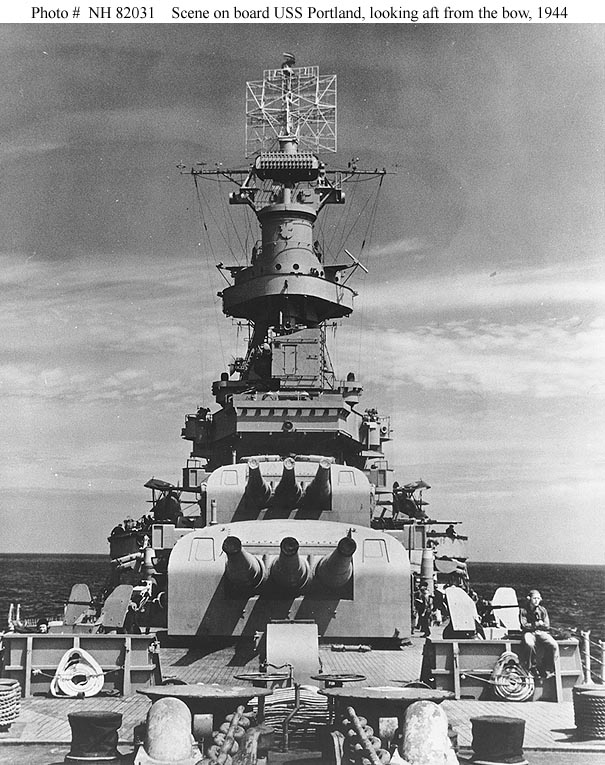

USS Portland’s bow in 1944

Like the previous ships, the Portland still featured the same 8-in triple turrets, completed by eight 5-in/25 DP guns and two QF 3 pounder Hotchkiss guns use dmore for saluting than AA purposes. Woefully obsolete, this was improved in 1941 by the addition of eight single Browning 0.5 in (12.7mm/90) heavy machine guns for AA defence.

Main guns: 3×3

Mark 9 8″/55 caliber guns in solidary mounts (not independent elevation for the barrels) like previous cruisers. The turrets were about the same models also, a superfiring pair fore, a single deck turret aft.

These early guns were introduced on the Lexington class. The 440 inches (11 m) bore (55 caliber) barrels weighted 30 tons, including the liner, the tube and its jacket plus five hoops. They were fitted with down-swing Welin breech blocks closed by compressed air, which came from the gas ejector system in order to accelerate reload.

-335 pounds (152 kg) AP shell

-260 pounds (118 kg) HE shell

-Muzzle velocity 2,500 feet per second (760 m/s)

-Maximum firing range 30,050 yards (27,480 m)

-Charge: two silk bags 45 pds (20 kg) (smokeless powder)

-2,800 feet per second (850 m/s) muzzle velocity (HE)

-Range 18 miles 31,860 yd (29,130 m) max at 41°

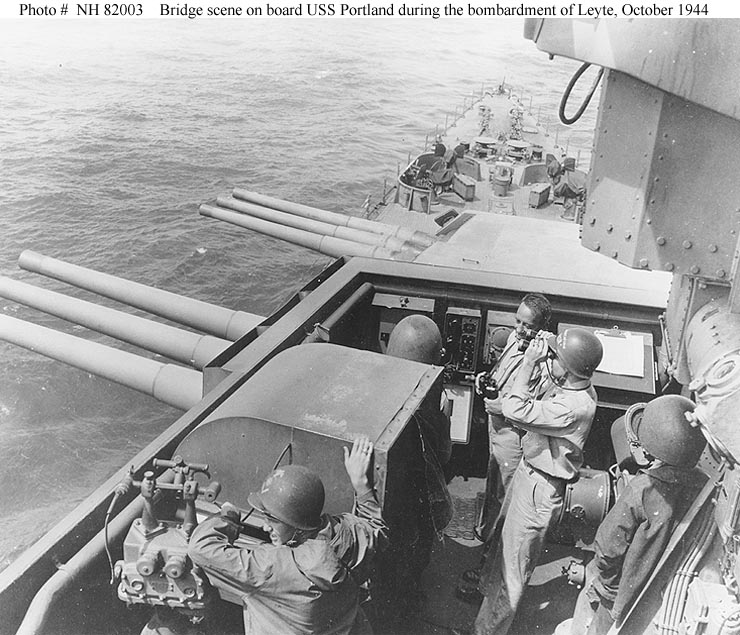

Gunnery at Leyte, October 1944, seen from the open bridge;

Secondary guns: 8x 5-in/25

This 2 ton 11 ft 10 in (3.6 m) gun (10 ft 5 in for the barrel itself) was rifled, 127 mm. Contrary to the Northamptons armed with only four when completed, they all had their eght pieces early on.

Shells: 52-54.5 lb (23.6 to 24.7 kg) HE/AP.

Elevation -10° to +85° range 14,500/27,400 feets (13,300 m) at 40/85°

Muzzle velocity 2,100 ft/s (640 m/s) manual

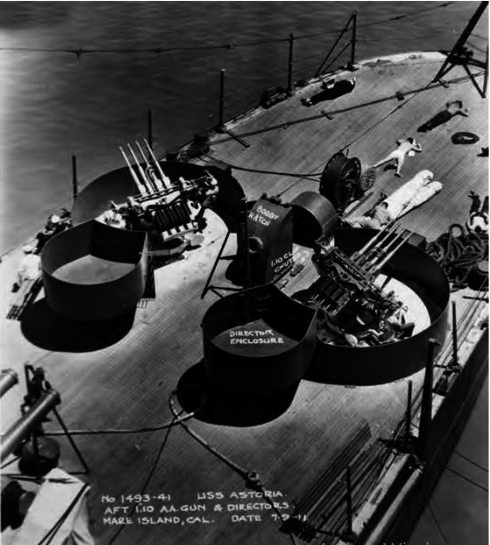

AA guns: Great changes over time.

1-1 inches AA guns (here on USS Astoria’s aft deck)

When completed, the cruisers only had two QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss. These venerable pieces ordnance were not supposed to be used for AA purpose bu merely as salute guns, possibly also dismounted for landing parties.

Basically, the engineered trusted the heavy 5-in guns for AA defence, as it was assumed ships attacks (when the ships were first designed in 1929) were lilely to come from high altitude bombers. The large targets would be dealt for at long range. From paper to reality however common sense prevailed and in 1941 at last, a better AA was planned. The 1.1 in (28 mm) guns intended to be adopted were still not realy or available in large numbers. As an interim measure, eight single cal. 0.5 Browning heavy M1920 machine guns were placed on the fighting top, aft tower and bridge in 1941. They were intended to deal with low-flying planes whih went through the 5-in barrage.

Later, in early 1942 the ships received their well-awaited four quadruple 28/75 Mk 1 light AA cannons. At a latter date, likely, the Brwownings wree replaced (or completed) with twelve single 20/70 Mk 4 AA Oerlikon guns.

From May 1943, 40mm/56 Mk 1.2 replaced the 1.1 inches “Chicago Piano”, as they were way more effective. They stayed until the end of the war on the same spots. Soon, the same metacentric height problem that plagued other cruisers of the previous classes and there were limits to what could be added. In 1944 extra AA gus were naturally added, at first four twin 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, and five 20mm/70 Mk 4 on Portland.

Indianapolis followed soon with twelve 20mm/70; two extra quadruple 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, then eight twin 20mm/70 Mk 4, and a full displacement reaching in excess of 15,000 tons. Not to be undone, USS Portland at the end of the war had four quadruple 40mm/60 Mk 2 and four twin 40mm/60 Mk 1 AA guns, plus seventeen 20mm/70 Mk 10 AA guns.

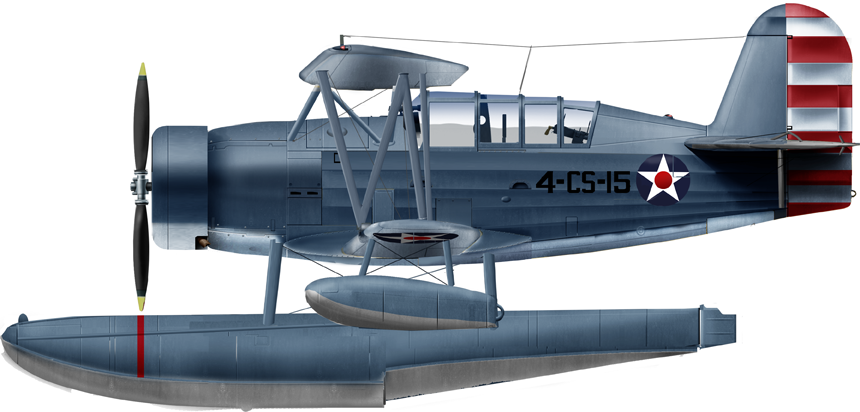

Onboard aviation

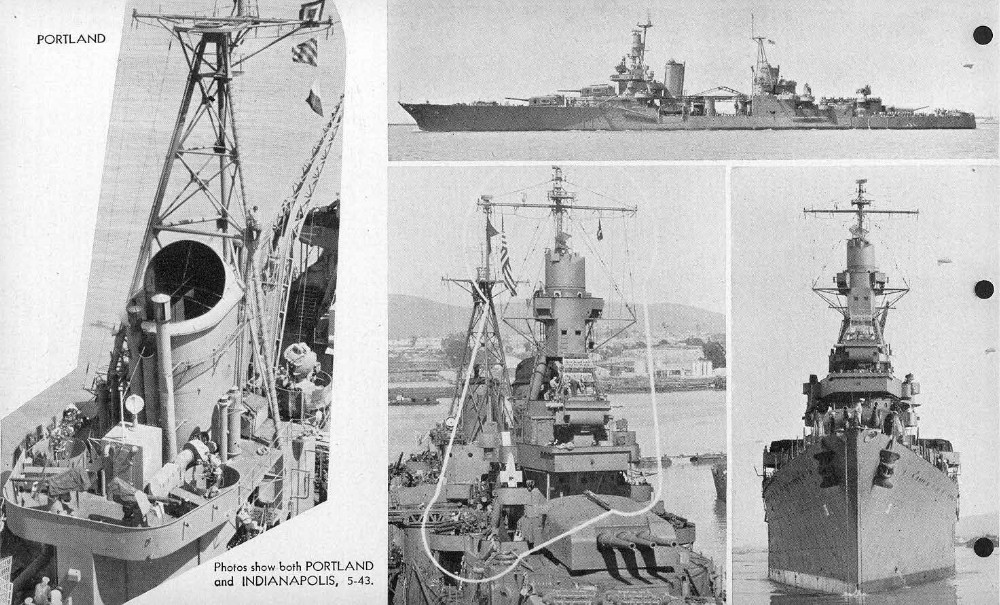

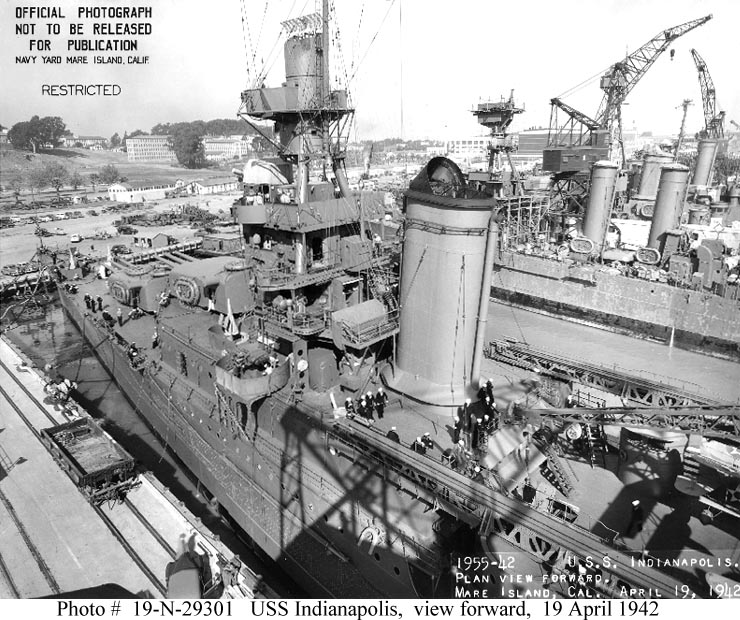

Mid-section of USS Indianapolis in April 1942 showing the crane, catapults and partially wings-folded (outwards one) Curtiss SOC seagulls.

Curtiss SOC seagull onboard USS Indianapolis, 1942, author’s illustration.

Like previous ships of the Northampton and Pensacola class, the Portlands were completed in 1932-33 started with the common observation floatplane of the time, the Vought O2U and O3U Corsair (1928), although according to navypedia, they were equipped with OL models before swapping on the O2U.

-The Curtiss SOC Seagull (1934) was introduced probably from 1936 and kept until around 1943, with perhaps the intermediary of the Curtiss SO3C Seamew, which is not documented.

The Seamew was a known “pig”, both slow and unreliable. Introduced as a replacement of the Seagull in 1939-40, it was soon replaced by the same in many cases. Photos shows however only the SOC ad at the end of the war the SC-1 Seahawk.

–Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk probably introduced when available during a refit in 1944, and until decommission. Onnboard USS Indianapolis as her remains shows when a exploratory dive was made. From May 1943, USS Portland only carried two planes and Indianapolis a single one.

Like the Northamptons, they had hangars wide enough to shelter four aircraft abreast the aft funnel, served by a single gooseneck lattice crane in front of the aft funnel, and two amidship catapults located behind the forefunnel. Even after refits and installation of better radars at the end of the war, their planes were still used notably for artillery spotting, liaison and recoignition of the vessels spotted at long range by radar. By 1944 both only had one catapult left to free weight for the installation of more AA, on the port side. Also, the seahawk was a faster and nimbler aircraft.

Fire control systems and radars

The Portland class started the war without radar. They were however fitted in early 1942 with an SC, Mk 3, and Mk 4 radars. By May 1943, they received SK radars in addition. In the autumn 1944 their electronics suite was duly modernized and both were installed Mk 3, Mk 4 radars and Mk 8, Mk 18 radars. In 1946 Portland was limited to the SG, SK, Mk 8, and Mk 18 radars.

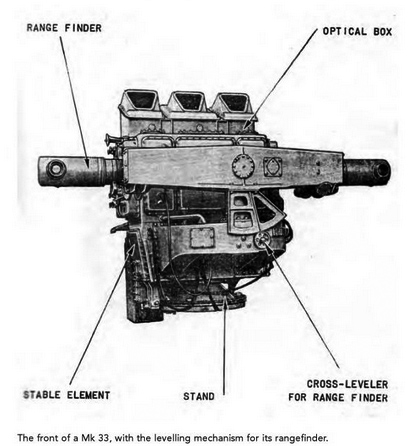

Mark 33 Director

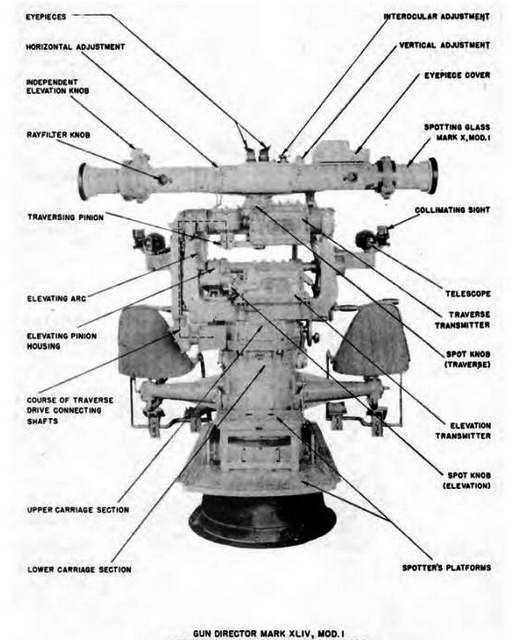

Mark 37 director, radar-assisted, installed during their wartime reconstruction. Note the victory marks. It was completed by a Ballistic computer Mk.1/Mk.1A below decks. The circled box is a Nancy IR signalling unit.

The crew inside a Mk.37 director. We are far from automation here. Decribed as badly cramped, they were superseded -with much relief- after 1945 by the smaller, less labor intensive Mk.67 and 68. The separation between the pointers and trainers were a major issue as they were complicated to coordinate. There was also no cross-leveller contrary to a Mk.33 or 28. The control officer had a telescope like the pointer and trainer, later replaced by simple binoculars so he could concentrate in scanning for targets instead. The post-war version also had a Mk25 radar integrating a scanning-r=target acquisition mode.

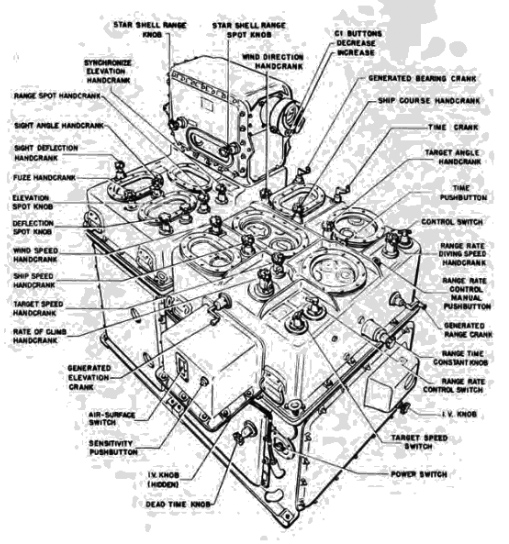

Mk1A ballistic computer, the cruiser’s standard at the time. Associated to the Mk 37 director it was crewed by three operators: A range, an elevaton and a star shell operators. They were supervised by a plotting-room officer. There was a stable element close to the computer generally manned by a level operator and cross-level operator (Historic Naval ships assoc. R.S. Pekelney)

AA gun gun director Mark 54, associated with the 28 mm and then 40 mm.

Reconstructions

D.ONI recoignition plates for the modernized Portland class, 1944-45

Indianapolis in Mare Island 19 April 1942, aft view (first modernization)

Same, forward view from the same vantage point

Modifications were made early on as USS Portland received an extension to the fore funnel, but this was limited. The major alterations came in wartime. Lie their precessors, at each opportinity of overhail and drydocking back home, modifications were made, starting in early 1942: Four quadruple 1.1in were fitted abreast the bridge and close to the 5in guns. Later, twelve 20mm guns were added instead of the twin 0.5 in cal HMGs. They were fitted with radars: SC, Mk 3, Mk 4 radars.

In May 1943, both were sent in drydock for a complete rebuilding: The bow received additional AA, which more than doubled, superstructure were completely rebuilt, lightened and lowered with an open deck. The bridge was extended, the after superstructure lightened, CT eliminated as well, tripod mast removed, replaced by a lattice structure close to the aft funnel. The AA saw four extra quadruple and four twin 40 mm Bofors, plus 12 supplementary 20 mm Oerlikon guns. These modifications later served as models to rebuilt the remaining Northamptons. Also in May 1943, light tripods were added forward of the second funnel and a large Naval director installed aft, whereas new SG, SK radars were installed.

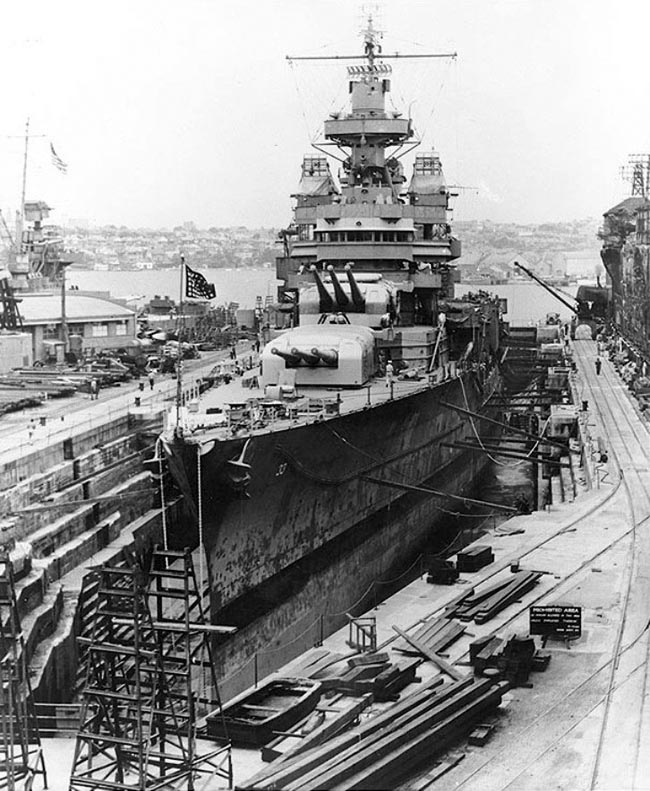

USS Portland in drydock at Cockatoo Island Dockyard late 1942

USS Portland at Mare Island Naval Shipyard 30 July 1944

Portland (CA33), was very active and deployed during most major naval operations of the Pacific. She survived the war and was broken up in December 1959.

Specifications (1941) |

|

| Displacement | 9,800-9,950 t FL |

| Dimensions | 592/610 ft (180/186 m) wl/oa x 66 ft 3 in (20.19 m) x 21-23 ft (6.4/7 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons steam turbines, 8 White-Forster boilers, 107,000 hp |

| Speed | 32.7 kn (37.6 mph; 60.6 km/h) |

| Range | 13,000 nmi (14,960 mi; 24,080 km) at 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) |

| Armament | 9 x 8-in (203mm) (3×3), 8 x 5-in (127mm), 4 seaplanes* |

| Armor | Belt 5 in, Deck 2.5 in, Barbettes 1.5 in, Turrets 2.5 in, CT 1+1⁄4 in |

| Crew | 917 |

USS Portland in 1945, the horizontal livery in effect since the end of 1944: Light gray/medium gray/dark blue – Illustration by the author. More to come, HD and modern.

Sources/Read More

Links

world-war.co.uk

pwencycl.kgbudge.com

Book: Naval Anti-Aircraft Guns and Gunnery By Norman Friedman

On globalsecurity.org

On navypedia.com

On history.navy.mil

On history.navy.mil

On ww2db.com

uboat.net

On worldnavalships.com

On DANFS

historyofwar.org

nytimes.com about the court martial

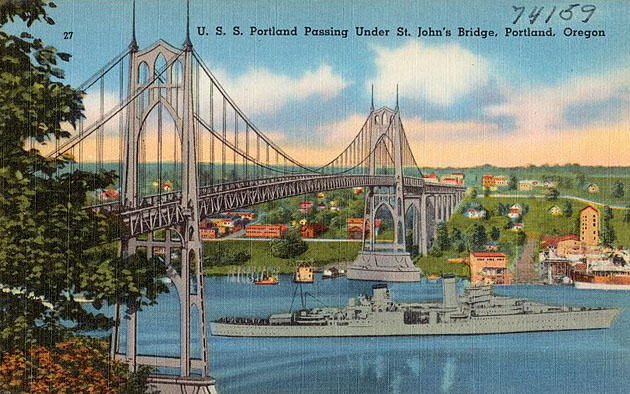

USS Portland under the St Johns bridge of her namesake city in Oregon.

Books

Conways all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Baker, A. D. (2008), Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Gunnery in the Dreadnought Era Annapolis

Bauer, Karl Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991), Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990 Greenwood Press

Hixon, Walter L. (2003), The United States and the Road to War in the Pacific: The American Experience in World War II 3 Routledge

Kearns, Patricia M.; Morris, James M. (1998), Historical Dictionary of the United States Navy Scarecrow Press

Miller, David M. O. (2001), Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World: Zenith Press

Morrison, Samuel E. (2001), History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Vol 15) Castle Books

Silverstone, Paul (2007), The Navy of World War II, 1922-1947 Routledge

Stille, Mark (2009), USN Cruiser vs IJN Cruiser: Guadalcanal 1942 Osprey

Videos

Movie trailer (2016)

Missing The USS Indianapolis Documentary

podcast by dan carlin

On the The National WWII Museum channel

The modeller’s corner

The Indianapolis 1945 matchbox 1/700 kit

USS Portand’s career

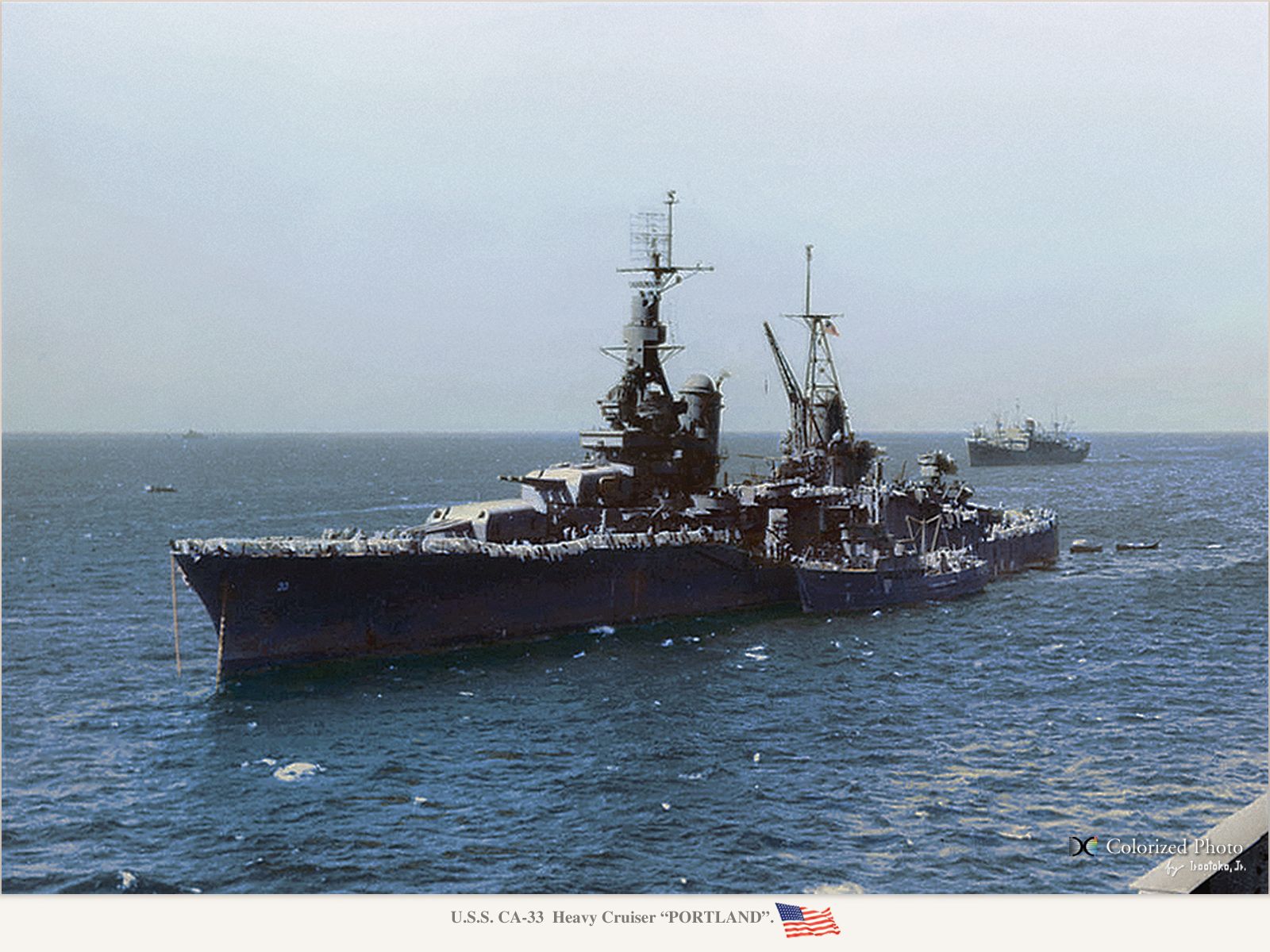

USS Portland in 1944, colorized y Hirootoko Jr.

After commission on 23 February 1933, USS Portland departed Boston on 1 April 1933 to Gravesend Bay in New York late before departing for a seach the next evening to the site where USN aicraft carrier airship USS Akron just crashed at sea. 36 minutes later she was underway and was first on scene. She started coordinating search and rescue operations as other vessels arrived in turn, but despite of the mobilization all 73 crewmember has been killed in the crash including Admiral William Moffett (Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics). This disaster put a nail in the coffin of USN us of airships, at least until the 1970s return of specialized blimps. The rest of the year and the next were spent in exercises between the east and wet coast, the Carribean in winter and Pacific in summer.

She steamed to, and departed from San Diego soon after on 2 October 1935 with USS Houston, to carry President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a goodwill visit of south America. Both cruisers stopped in Panama and other ports until making it back to Charleston in South Carolina. There, the President disembarked and Portland served in the the Scouting Force, Cruiser Division 5 in 1936, 1937, 1938 and later the United States Pacific Fleet in 1939. She alternated peacetime training and goodwill missions, crossing the equator on 20 May 1936.

On 7 December 1941, USS Portland was underway to Midway Atoll, escorting the USS Lexington’s carrier group carrying reinforcement planes. Until 1st May 1942, she adopted a long patrol route from Hawaii to the Fiji islands. She would have a fairly long and active service in the Pacific theater.

Battle of the Coral Sea

He first major action in May was to counter Japanese “Operation Mo”, targeting Port Moresby. USS Portland was assigned to Task Force 17 (Rear Admiral FJ Fletcher, USS Yorktown) escorted also by USS Astoria and Chester, the destroyers USS Hammann, Anderson, Perkins, Morris, Russell, Sims, the oilers USS Neosho and Tippecanoe. TF 17 departed Tongatabu (27 April) and on 1st May, joined TF 11 300 nmi northwest of New Caledonia, the refuelling and gathering point. While TF11 was still refluelling until 4 May, Fletcher departed with TF 17 towards the Louisiades archipelago. At 17:00 on 3 May, her was notified Japanese troopships spotted at Tulagi and en route the southern Solomons.

TF 17 sailed towards them at 27 knots, in a position to launch an airstrike the next morning. On 4 May TF17 indeed launched an aistrike from 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) south of Guadalcanal, before retiring southwards and on 5 May, was reunified with TF 11 and TF 44 at a programmed site, 320 nmi south of Guadalcanal. Reports of a convoy bound for Port Moresby, the force sailed to the Louisiades. Task Group 17.2 (Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid) was the new assignation for USS Portland, with USS Minneapolis, New Orleans, Astoria, Chester, and five destroyers, still screening Yorktown. On 8 May she helped fejnding off Japanese air attacks, but could not prevent damage, before escorting the crippled USS Lexington. However the fired onboard now uncontrllable she was evacuated and scuttled, teh cruiser taking onboard 722 survivors. She lost four crewmen onboard USS Neosho when she sank.

USS Portland at Midway

USS Portland transferring survivors of USS Yorktown to USS Fulton, 7 June 1942.

After fixes and resplenishing at Tongatabu, USS Portland saw Captain Laurance T. DuBose be coming her new commander. She escorted USS Yorktown back to Pearl Harbor and proceeded to Midway Atoll, as part of the trap set up to ambush Japanese forces incoming for “Operation mi”. On 4 June, Yorktown and Enterprise launched their air strikes which devastated the Japanese carriers, when Japanese aicraft from IJN Hiryū arrived and immediately targeted USS Yorktown. USS Portland, to her port prompted a vigorous anti-aircraft barrage with Pensacola and Vincennes at 14:00. Another wave came after 16:30, and this time USS Yorktown was torpedod several times. Abandoned, her 2,046 survivors were picked up by five destroyers, and later transferred onboard USS Portland, which crew was not reaching nearly 3,000 men.

She steamed toward Pearl Harbor, and transferred the crew on the submarine tender USS Fulton on 6 June, departing to search for downed naval aviators on the 7th, before being ordered to join Saratoga’s TF, prepared to depart fot the Aleutian Islands before being recalled to Pearl Harbor as the Japanese invasion took place in between.

Guadalcanal Campaign

Portland was part of the invasion fleet to Guadalcanal, defending USS Enterprise, now the one of two CVs still operational after the losses at Coral sea and Midway. She covered the landings at Tulagi and Guadalcanal on 7–9 August but missed the Battle of Savo Island and followed USS Enterprise retiring, remaining in the area for upcoming Marines operations on Guadalcanal, and protect communications lines? She soon participated in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons on 24 August, and helped with the other cruisers attached to CV-6, she was claimed 4-5 Japanese aircraft. But despite her efforts, the aicraft carrier was hit at 18:34. Close defense went on 25 August, eventually foiling the reinforcement planned by Admiral Yamamoto.

She escorted Enterprise back to Pearl Harbor before being ordered to perform a secret mission to the Gilbert Islands, a raid on Tarawa with USS San Juan, hosting Rear Admiral Mahlon S. Tisdale for the operation, in what became Task Unit 16.9.1. On 15 October she attacked Japanese shipping near Tarawa, damaging a transport and a destroyer. She only had one observation aircraft damaged. She was back to USS Enterprise’s task group for upcoming operations.

She took part next in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, trying to repel Japanese airstrikes on USS Enterprise on 24 October. She had one 1.1-inch (28 mm) exploding when firig at too low depression, with no casualties but 19 injured. USS Enterprise was hit again and was soon targeted while retiring by a Japanese submarine that fired and missed CV-6 but hit instead USS Portland with three torpedoes. Fortunately, none detonated as they were probably too close to arm. Basically USS Portland shielded CV-6 and paid a moderate price for it.

USS Indianapolis 20 April 1942.

She participated also in the 2nd Battle of Guadalcanal, mostly a serie of air battles on 12–15 November. The Japanese failed at landing 7,000 reinforcements and destroy Henderson field as a result. USS Portland was escorting a convoy from New Caledonia (TF 67), offloaded supplies on 12 November when an aistrike of 46 aircraft arrive don sight. The following night, she despatched with four other cruisers and eight destroyers (Daniel J. Callaghan) sent to stop a Japanese force, spotting two battleships, one cruiser and eleven destroyers. A firce night battle unsued, IJN Akatsuki being promptly sunk, but USS Portland was struck by a long lance torpedo (either from IJN Inazuma or Ikazuchi). It happened at 01:58, and the torpedo detonated, mushing her stern on the starboard side. Both inboard propellers were dislodged and the rudder jammed as well as her aft main turret.

Her 4° list was quickly compasented by ballast, but steering caused her to turn in circles to starboard for the remainde rof the action. She nevertheless engaged IJN Hiei with her forward turrets, and the latter returned fire, missing. Portland started fires on Hiei. When dawn came, there were talks about her fate, since she was unable to exit the area. At 06:30 she opened fire the crippled IJN Yūdachi, which exploded and sank. Her teams, which frantically worked on her steering system eventually succeeded and she was able to proceeed and leave the area. She later was awarded a Navy Unit Commendation but deplored 18 killed and 17 wounded.

Torpedo damage after Guadalcanal.

Higgins boats a YP minesweeper and a tug helped her to reach Tulagi on 14 November, for further repairs until she was able to proceed to Sydney under tow by USS Navajo, escorted by USS Meade and Zane. Sh arrived on 30 November but stayed out of the busy drydock until 24 December. Chester and New Orleans were still in repairs there; The crew was given extended leave meanwhile. After preliminary repairs she was able to steam at full speed back to the US, at first escorted by HMAS Warramunga. She refuelled at Samoa and Pearl Harbor, and made it into Mare Island Navy Yard on 3 March 1943 for a welcome refit and modernization in addition.

Aleutians and Pacific raids

Thuis long immobilization and modernization needed to make a refresher training cruise in southern Californian waters. She was then prepared for the invasion operation of the Aleutians, late in May 1943. On 11 June she was off Kiska, starting a shelling to cover the landings, starting on 26 July. On 23 September she was recalled to Pearl Harbor. In San Francisco by early October, she returned to Pearl Harbor in mid-October and from November 1943 until February 1944, she took part in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaigns. Tarawa on 20 November (lightly damaged by friendly depth charge there), and Marhsall Islands by December 1943 with USS Lexington (II). She was back to Pearl Harbor on 25 December, drydocked for further repair to her rudder and propellers; never properly fixed since her torpedo damage.

She then joined TG 51 (Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill) for an operation on Darrit on 30 January 1944. The island was pounded and a firce landed, only to discover it was empty of Japanese presence. She particpated next in the Eniwetok Atoll landings on 8 February, Parry Island on 19 February. She screen Essex-class carriers during airstrikes at Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai until 1st April 1944, then moved to cover the landings around Hollandia and Tanahmerah (New Guinea) on 21-24 April. Next she covered a raid on Truk with five other cruisers and bombarded Satawan (Nomei). It was by then time for an overhaul, which was done at Mare Island, completed in August 1944. She participated in the bombardment on Peleliu (12-14 September), covering the invasion from 15 to 29 September, and heded to replenish in Manus Island.

Battle of Leyte

She was part of Cruiser Division 4, steaming off Leyte on 17 October, and entering the Gulf on the 18th, starting a 18h shore bombardment before the landings. On the night of 24 October, a large japanese force was spotted entering the Surigao Strait, advancing in a column in full darkness, before encountering the ambuishing US force, of which Portland was a part of. She steamed across the strait to cross the T of the Japanese, already shaked by PT boats attacks, then destroyers, until caught by a withering textbook fire. USS Portland targeted herself the cruiser IJN Mogami hitting her four times at around 04:02 and battering her for ten minutes, then until 05:30. One such hit devastated her bridge, killing the captain and executive officer. This concluded her Battle of Surigao Strait, part of the larger confrontation of Leyte.

Final Operations

From 3 January to 1 March 1945, USS Portland covered task forces operating at Lingayen Gulf and Corregidor. From 5 January she shelled Cape Bolinao and entered the Gulf, shelling the eastern shore until forced to fend off a large kamikaze force. On 15 February she shelled the south shore of Corregidor before landings and was back further south on 1 March for repairs and replenishment. From 26 March to 20 April, she was assigned to TF 54 operating off Okinawa, asked for close support of the landings. She fended off no less than 24 kamikaze attacks, shooting down four confirmed Japanese, planes, with two assists. On 8 May until 17 June, she provided on-call fire to ground forces progressing inland. She saild out on 17 June for maintenance and resplenishment before returning in Buckner Bay (6 August) for more shore bombardments. The end of the war on 15 August was a relief for many crewmember there since December 1941. The last eight month in particular has been particularly intense.

USS Portland became flagship for Vice Admiral George D. Murray, in command of the Mariana Islands sector and accepting the surrender of the Carolines. She was in Truk Atoll when Murray accepted for Nimitz, a formal capitulation, with the ceremonies held aboard USS Portland. She then was prepared for runs within Operation Magic Carpet, back to Pearl Harbor on 21-24 September with 600 troops, dismeabarke din her namesake city of Maine followed by examplary Navy Day celebrations, on 27 October 1945. She left the Pacific, making two trans-Atlantic crossings uintil Christmas and a well-deserved, long crew leave. On 11 March 1946 she was sent to Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for inactivation, Reserve Fleet. Due to her age it was decided to have her decommissioned at Philadelphia NYd, on 12 July 1946, although maintained in Reserve. She was struck from the Navy List on 1 March 1959, sold on 6 October and scrapped in Panama City, Florida in 1961-1962. There were proposals to save her to become a museum ship at Portland, but this never went to pass. At least her tripod mast was preserved at Fort Allen Park in Portland. “Sweet Pea” as she was nicknamed, earned 16 battle stars, one of the highest score from any USN cruiser at the time. She missed almost none major battle of the pacific.

USS Indianapolis’s career

USS Indianapolis in 1944, colorized y Hirootoko Jr.

USS Indianapolis (CA 35) was commissioned on 15 November 1932, second ship of the USN named after this city of Indiana, followin a 1918 cargo ship, and chistened during her launching by the daughter of the former Mayor of Indianapolis. After a shakedown cruise under command of her first captain, John M. Smeallie, through the Atlantic to Guantánamo Bay, she was ready for duty on 23 February 1932. She sailed via the Panama Canal for training exercises off the Chilean coast. After post-cruise fixes in Philadelphia she sailed to Maine, carrying President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at Campobello Island in New Brunswick (1 July 1933). She was back to Annapolis (Maryland) on 3 July to be visited by academy’s cadets and hosting six members of the Cabinet with president Roosevelt. On 4 July she steamed for Philadelphia Navy Yard.

On 6 September, she carried Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson in a Pacific fleet inspection, between the Canal Zone, Hawaii, San Pedro and San Diego until 27 October. On 1 November 1933, she was flagship, Scouting Force 1, and for large scale manoeuvers off Long Beach. On 9 April 1934 she departed for New York to embark president Roosevelt for a naval review.

Back at Long Beach on 9 November 1934 she had a new captain, William S. McClintic, from 10 December 1934, until 16 March 1936. She continued training in 1935-36, changed captain, with Henry Kent Hewitt in command, and on 18 November 1936, she embarked Roosevelt (3rd time, so she was almost nicknamed the “presidential yacht”), to Charleston in South Carolina, and then starting a goodwill cruise to South America: Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and back to Charleston on 15 December. Northing much happened in 1937-39, she alternated between the Pacific and Atlantic during seasonal manoeuvers and fleet problems, always as Scouting Force 1’s flagship. Thomas C. Kinkaid took command of 5 June 1937 (yes, that one), and was replaced on 1st July 1938 by John F. Shafroth Jr. until 1st October 1941. This was her first prewar captain.

USS Indianapolis underway in 1939

New Guinea Campaign

USS Indianapolis after refit, off Mare Island Navy Yard 20 April 1942

On 7 December that year, USS Indianapolis was now flagship of Task Force 3 under command of Captain Edward Hanson, operating with ships from MineDiv 6 and MineDiv 5, conducting mock bombardment of Johnston Atoll. USS Indianapolis ws reassigned in Task Force 12 , as part of the large search for the Japanese carriers. Back to Pearl Harbor on 13 December she was versed to TF 11 to participate in the New Guinea campaign. She arrived 350 mi (560 km) south of Rabaul (New Britain) escorting USS Lexington. On 20 February 1942, they were attacked by 18 Japanese aircraft, 16 being shot down, in part by AA fire from her and nearby destroyers.

On 10 March, combined with Yorktown’s TF, they were sent to attack Lae-Salamaua. Arriving by surprise through the Owen Stanley mountain range, the US airstrike was very successful. Indianapolis then was discharged and sent back to Mare Island for an overhault. She soon get orders to escort a convoy to Australia. On 11 July 1942, Morton L. Deyo took command.

Aleutians Campaign

Indianapolis next was ordered to the North Pacific, to carry out a support mission for the Battle of the Aleutian Islands. On 7 August, Indianapolis was off Kiska Island, where the Japanese landed. Fog disrupted observation and covered their approach, and USS Indianapolis fired her main guns on the assembled Japanese fleet in the bay, soon spotted in detail by her Floatplanes. Several ships were reported sunk while shore installations were damaged. Japanese shore batteries returned fire but made little damage before being silenced. Japanese submarines approaching were spotted and hunted down by American destroyers. The US force then moved for the attack on Adak Island, establishing a base at Dutch Harbor (Unalaska Island). This force returned to Pearl for resplenishment and were back in early 1943.

In January 1943, USS Indianapolis covered the landing of Amchitk in the Aleutians. On 19 February she led two destroyers on patrol, southwest of Attu to locate a signalled Japanese convoy to Kiska and Attu. Indianapolis soon caucght the 3,100-long-ton (3,150 t) cargo ship Akagane Maru, which tried to reply to her radio challenge and was shelled until sinking. Until May, CA-35 remained off the Aleutians, escorting convoys, providing shore bombardments during landing. Attu and Kiska were retaken, the latter from 15 August. Captain Nicholas Vytlacil took command on 12 January 1943 and stayed until 30 July 1943, replaced by Einar R. Johnson.

Blueprint of the last overhaul in 1944

Pacific campaign 1943-44

After an overhaul in Mare Island, USS Indianapolis became flagship, Vice Admiral Spruance, 5th Fleet. She was underway on 10 November with the Southern committed for Operation Galvanic (Gilbert Islands). On 19 November, she shelled Tarawa, and participated next in the Battle of Makin, then back to Tarawa for inland fire-support. She also claimed an aircraft and stayed for close support until the end of the Battle of Tarawa.

On 31 January 1944, she was one of the first ships bombarding Kwajalein. She dealt with shore batteries and many strongpoint of the defence, destroy an important blockhouse, devastated shore installations and continued during the landing and progression inland. She was in Kwajalein Lagoon proper on 4 February. Departing in March she attacked the Western Carolines, starting with the Palau Islands (30–31 March) partiipating in the sinking of three destroyers, 17 freighters, five oilers, with 17 others badly damaged and airfields destroyed. Yap and Ulithi were next on 31 March, Woleai on 1 April. She fended off several air attacks, claming her second plane, a “Kate”.

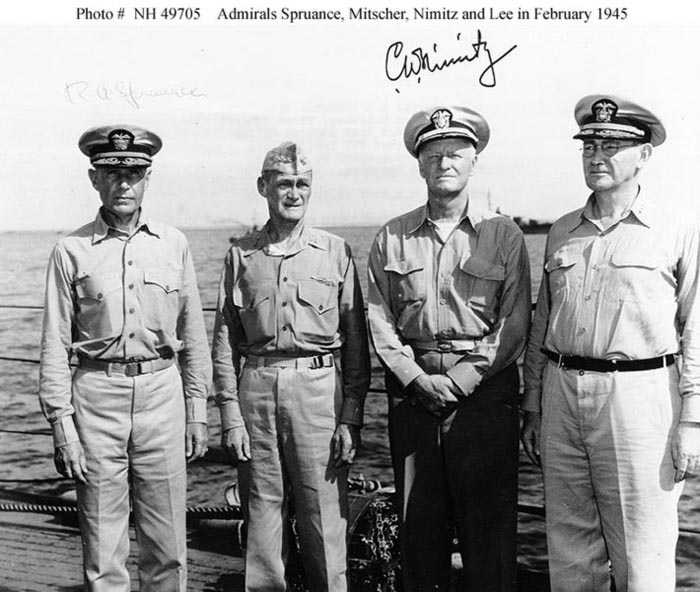

By June 1944, the Mariana Islands campaign was next. She covered an airstrike on Saipan on 11 June, and shore bombardment from 13 June, in fact USS Indianapolis as flagship played a major coordinating role during the Battle of Saipan. Landings proceeded from 15 June when it was signalled a major Japanese force incoming to the Marianas. Spruance detached a fast carrier force, another taking care of the airfields at Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima.

Battle of the Philippines sea

On 19 June, Indianapolis played her part in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Japanese carrier planes were met those of the US Taks Forces in the area, and AA from a multitude of Allied ships. The “turkey shoot” cost the Japanese in a single day 426 Japanese planes for 29 losses. USS Indianapolis had her third victory, another “Kate” B5N. IJN Hiyō, two destroyers and a tanker were also sunk, Taihō and Shōkaku bing claimed by US submarines.

Indianapolis was back in Saipan on 23 June to resume support, then Tinian for the preparatory shellings of the Battle of Tinian. Guam fell also and USS Indianapolis was the first ship to enter Apra Harbor since 1941. For a few weeks she patrolled and escort ships there until moved to the Western Carolines and attacked on 12-29 September on Peleliu (Palau) with a run for resplenishment to Manus Island and back. After 10 days of intense support she was sent for a welcome overhaul at Mare Island. On 18 November 1944, Charles B. McVay III took command of the ship, until 30 July 1945 and his court martial for the loss of his cruiser (spoiler alert).

Iwo Jima & Okinawa

U.S. Navy Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr. (listed from left to right) aboard the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35) in February 1945.

When this was over, USS Indianapolis was assigned to Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s fast carrier task force, on 14 February 1945. She escorted them when launching an attack on Tokyo in support for the operations on Iwo Jima planned to take place on 19 February. Air facilities and many strategic installations of the Home Islands were pummeled, a mission accomplished in complete tactical surprise. 499 enemy planes were caliamed, many on the ground, for the loss of 49 carrier planes, mostly due to AA fire. Many ships were destroyed, including an aircraft carrier.

This force was back to the Bonin Islands, then deployed in support for the landings on Iwo Jima. Indianapolis stayed there until 1 March, before making it back to escorting Mitscher’s task force for a strike against Tokyo on 25 February, and later Hachijō. Next was Okinawa, Indianapolis still assigned to the fast carrier force from Ulithi (14 March). The first strike was on 18 March, 100 mi (160 km) off Kyūshū, targeting airfields on Kyūshū and shipping of the area. Kobe and Kure notably were hit. There was an air attack on 21 March.

Now as part of Task Force 54, the cruiser was sent to bombard positions before the invasion of Okinawa. Pre-invasion bombardment started on 24 March, and lasted for a week, until the cruiser depleted her stocks. Her AA gunners had any occasions to fend off attacks, just like her sister ship. She claimed six planes, two damaged. On 31 March, her lookouts spotted an incoming Ki-43 “Oscar” which targeted her. Her 20 mm guns were too late to react, so the plane was it, but not before the pilot managed to drop his bomb at just 25 ft (7.6 m), crashing his plane close to the port stern. The bomb penetrated all deck, until the keel and exploding underneath. The concussion almost broke the keel. Flooding was intense drawining nine. Her bulkheads however stopped the flooding eventually and the cruiser was found listing to port. A salvage ship came quickly for emergency repairs. She had her propeller shafts out of action and fuel tanks ruptured, water-distilling plant destroyed. She was ordered to proceed under escort to Mare Island for repairs in April.

Sinking and controversy

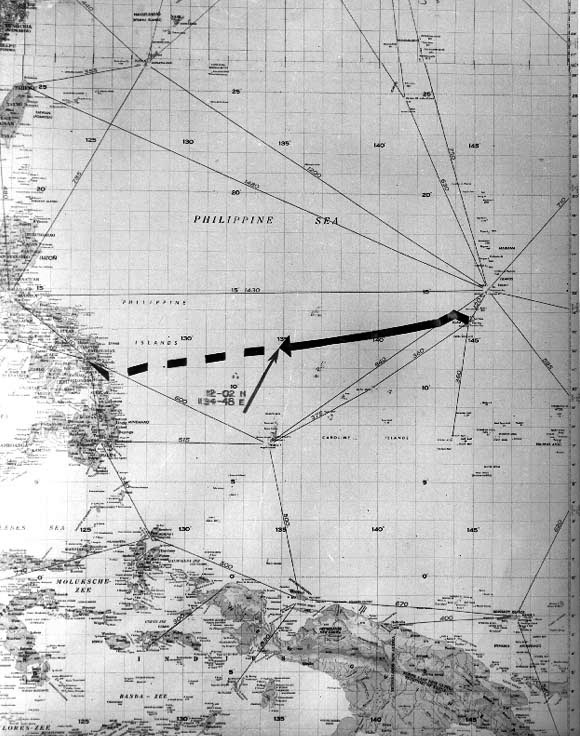

Last known trip charted.

Major repairs had her inactivated from April to July, so four months, with an overhaul. USS Indianapolis emerged in July, and after training she received orders for a top-secret mission, embarking enriched uranium to Tinian, a load which represented half of the world’s supply. She also carried all the parts and engineers committed to assembly “Little Boy”. She departed San Francisco’s Hunters Point Naval Shipyard (16 July), and steamed to Pearl Harbor at around 29 knots (setting a distance record by the way). From 19 July she departed for Tinian and deliverd her most precious payload on 26 July.

She proceeded to Guam, for an exchange of sailors after completing a tour of duty. A fateful day for those lucky who disembarked. Indeed, departing on 28 July, proceeding to Leyte for training before heading Okinawa and Jesse B. Oldendorf’s Task TF 95, she was caught underway.

At 00:15 on 30 July 1945, two Type 95 torpedoes hit her starboard side, launched from a submarine later identified as I-58 (Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto). The latter mis-identified her for USS Idaho. The explosions caused immediate flooding and the ship took a heavy list, settling by the bow. After a 12 minutes continuous list she capsized, her stern rising as she sank. 300 men when still aboard went she disappeated, leaving the rest of the crew, which had 12 minutes to flee the ship, in dire conditions. They were few lifeboats afloat, many other sailors were without life jackets. This was the start of their cursed week at sea.

Outside those dying on uncared injures, other went down by exhaustion, all suffering from lack of food (but a few crackers salvaged from the debris) and acute dehydration and hypernatremia. Under the hot sun and night hypothermia preventing them to rest, severe desquamation, their worst threat however was still relentless shark attacks. It was etsimated hundred of sharks were drawn there after the explosion and pacing together, caused such rampage that many men were driven ade and killed themselves at the occasion. In fact only 316 of the nearly 900 men adrift survived, with an estimated 150 kills by sharks, the rest from exposure.

One important point in that affair was the late rescue operation. It was down to several factors:

- The Navy command did not knew of the ship’s sinking in the fist place: Survivors were spotted 3.5 days later*.

- HQ Commander Marianas (Guam) assumed that ships as large as Indianapolis would reach their destinations on time. Positions were based on predictions, not reports.

- When supposedly arrived in Leyte it was just removed from the plotting board.

- It was erroneous recorded as arrived in Leyte by Commander Philippine Sea Frontier HQ

- Lieutenant Stuart B. Gibson, operations officer in Tacloban failed to enquire (and was later reprimanded)

- Three stations received the distress signals from a survivor, but none acted upon the call

*By a PV-1 Ventura (Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn), confirmed later by a PBY 2 (Bill Kitchen both during patrol flights). Gwinn dropped a life raft and radio transmitter so all available assets were dispatched at once. A PBY-5A Catalina managed to rescue as many survivors as possible, some strapped to the wings, and the first ship there was the Destroyer escort USS Cecil J. Doyle later joined by six other ships. They picked up the remaining survivors. The event was reenacted in 2007 Discovery Channel series “Shark Week”.

In short, late war complacency and near incompetence were to blame. At last something emeged positive from the tragedy as the Navy created the Movement Report System to prevent such disasters in the future. Captain Charles B. McVay III survived the sinking of his ship and was also court-martialled for his part in the disaster. Although his ship was unescorted back from her mission, two charges were retained against him: Failing to order his men to abandon ship and hazarding the ship by failing to zigzag as prescribed far from patrolled lanes. Admiral Chester Nimitz latter remitted McVay’s sentence but even after his return to active service his reputation was broken and he retired a rear admiral in 1949 and shot himself in 1968, aged 70. After new elements were brought to the table recently, McVay’s name was cleared of all wrongdoing by the Secretary of the Navy in 2001, to the relief of his family. The loss of the cruiser did not diminished its metits, as USS Indanapolis (“Indy”) won 10 battle stars for her service.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign