Long Island class (1940)

Escort Aircraft Carriers USS Long Island, USS Charger (CVE-1, CVE-30)

Escort Aircraft Carriers USS Long Island, USS Charger (CVE-1, CVE-30)

WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classWW2 first escort aircraft carrier

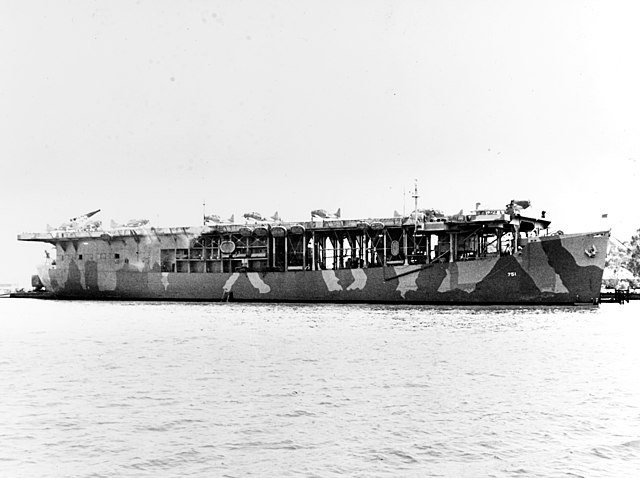

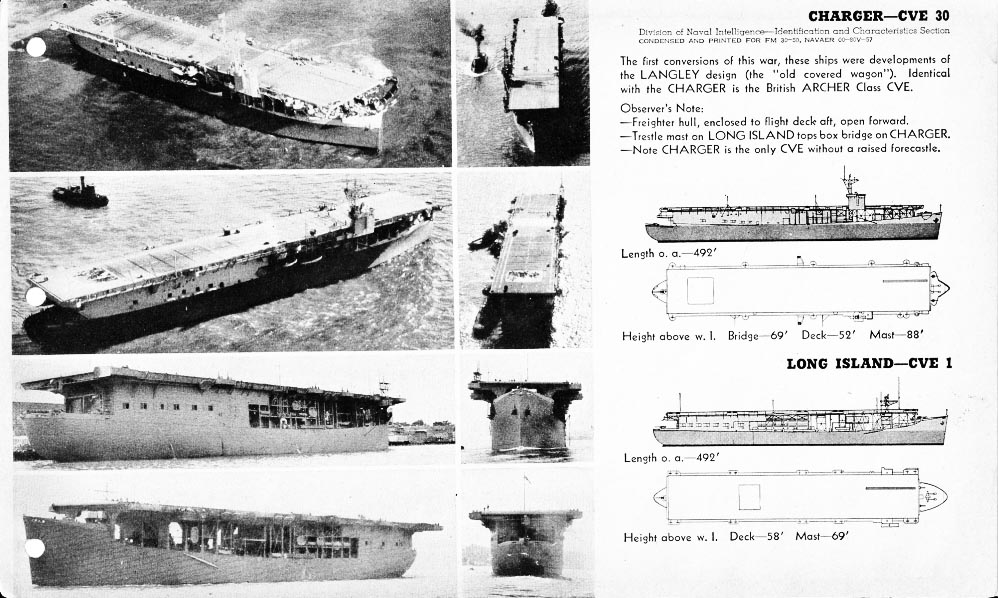

The USS Long island (CVE-1) is probably forgotten today in the mass of aircraft carriers built by the United States during WW2, but is was the equivalent of the British HMS Audacity: The quick conversion of a merchant freighter as a light auxiliary aircraft carrier for the sole purpose of convoy escort. USS Long Island was the first of such conversions, an experiment followed by the much improved USS Charger (CVE-30) in 1942. She was indeed the first completed, in June 1941, before the United States were at war. A prototype, for future conversions and for convoy escort in the Atlantic even before the US were officially at war. And to follow requested lend-lease aircraft carrier transfers to the Royal Navy.

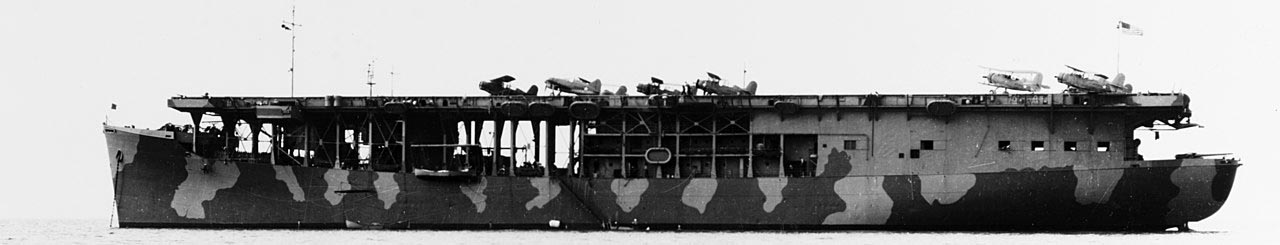

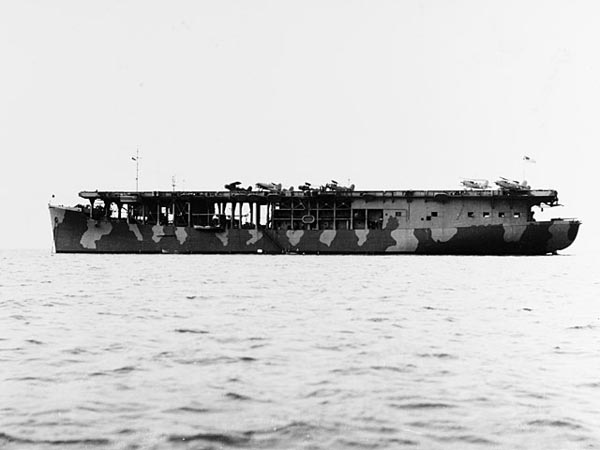

USS Long Island with its measure 12 camouflage in early 1942

Long Island in fact preceded many other classes: The lend-lease Avenger, Attacker, and Ameer class, the Bogue class, the Sangamon class (based on T3 tankers), and the mass-produced “jeep carriers” from Henry J. kaiser’s yards (Casablanca class) or the larger Commencement Bay class. These numerous “baby flat-tops” served both in the Atlantic, contributing to greatly hamper the U-Boat campaign, but also covered amphibious landings in the Pacific until the end of the war. Cheap and quick to built, they had however limited capacity and small air groups, and were too slow to follow the fleet. That was, in a nutshell, the CVE concept, where “E” stood for “Escort”.

A bit of context: USN “quasi war” with Germany (1941)

Historians commonly retained the 7 of december, 1941, and formal declaration of war to start the WW2 countdown for the United States, but in reality, the active participation of the US Navy in convoy escort in 1941, almost guaranteed “hot” encounters with German submarines. It happened as there was the famous end-lease agreement with Great Britain to provide armaments and suppplies. They needed to cross the atlantic, on British but also US flag ships. Roosevelt’s Neutrality Act of 1939 already persuaded the Congress a “cash and carry” system in which French or British Ships would take the supplies they need on harbors or at the frontier with Canada for example, but by December 1940 Britain’s PM Churchill worryingly announced that with currency and gold reserves dwindling, his country would not be able to pay cash for military supplies or shipping for long, so a leasing system setup in place: In March 1941, at last the Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act.

USS Reuben James, sank by U-552 on 31 October 1941.

From then on also, as U-Boats already started to rampage the atlantic and beyond, and this included that U.S. food and war materials were shipped to Britain on US-flag ships. Soon with the activity of u-Bootes well into the mid-atlantic the question of escort was asked, and it was soon made clear by both admiralty due to the limited range of aviation, that the Royal Navy would provide and effective escort up to mid-atlantic, and the US Navy neutality patrols started to also diverge ships to provide escort aso to mid-atlantic. There was still a large gap in between, in which U-Boates operated.

It was hard for USN captains to see American cargo ships sunk under their protection. Soon also they spotted submersibles or persicopes and that was equally hard not to take action. The neutrality rules just stated that USN ships were not supposed to engage any enemy vessel until threatened themselves. It was unclear however if this applied indirectly, for cargo vessels under USN escort. Technically, Rooselevl ably manouvered the congress and opinion into making the USN the the front line in America’s defense against Nazi Germany. The Times of London itself couned the “forward strategy despite a neutral status.” Since this was to be a forward defense reaching far into the Atlantic, the U.S. Navy was to be fully committed, and the dreaded “rules of engagements”, on both sides, soon went out of the window. Despite Dönitz’s strict instructions, careless U-Boat commanders started to attack all nation’s ships in growing numbers in 1941. The destroyer USS Niblack fired the first shots; dropping depth charges on a U-boat while conducting rescue operations near a torpedoed Dutch freighter, off the coast of Greenland on April 10, 1941.

“Belligerent Neutrality” was defined by Joint Chiefs of Staff after January 29, 1941. After two months, it resulted in more clearly defined American assignments in what was in effect, an undeclared war. Roosevelt set guiding principles for a combined strategy with the British and the USN course of action would be conservative until its strength developed for a more effective action. Convoy escort rules were defined at that time. The “belligerent neutrality.” meant from new on, protection of the Atlantic convoy routes became part of the American security policy, and that the USN would take a more active aprt in it, which included softened engagement rules. By May 1941 it was accepted that a captain could, and should, on its own initiative, attack on sight or detected by sonar any U-Boat. On April 18, Admiral King issued Operation Plan 3-41, defining transgression lines, areas where any sighted U-Boat should be attacked and sunk on sight. At the same times, after hundred of British merchant losses, American vessels replaced these in growing numbers in the Atlantic. Transfers of Freighters and oilers were made. Soon the exclusion zone was widened northwards: On June 7, the president approved the “Basic Joint Army and Navy Plan for Defense of Greenland,” which defined the Northeast Greenland Patrol. Greenland itself became a massive mid-atlantic base, integral to the lend-lease organization, notably for planes.

Depht charges dropped during the battle of the Atlantic

On June 20, 1941, U-203 tried to get into a firing position against the battleship USS Texas, when sighted, while another sank the SS Robin Moore on June 27. In August, USN ships now escorted convoys on a regular basis, not just diverted from neutrality patrols, in effect violating previous neutality stance, and giving more opportunities of both sides to met in combat. On September 4, U-652 attacked the American destroyer USS Greer and as a result, President Rooselevelt ordered the “shoot on sight” instruction, not only in exclusion zones but for all ships involved in convoy escort. In response, Admiral Raeder soon agreed wth Hitler that no quarters would be made between US and British ships, and U-Boat captains were now freed for any limitations. The Kriegsmarine defined by then a “locally restricted declaration of war.”. Still public opinion was 62% favourable to the president’s policy.

In September, the British Admiralty Submarine Tracking Room started to send data to the US admiralty on a regular basis, and coordination reached a new level. Convoy HX150 was in September 16, the first entirely U.S. protected convoy, seeing underway a duel between USS Truxton and an unidentified U-Boat, while several cargoes were sunk. In October, admiral King’s Atlantic fleet had grow to a significant size: Seven battleships, five cruisers, eight light cruisers, 87 destroyers, and four aircraft carriers were deployed, plus numerous long-range air patrols, from the Carribean to Greenland. On October 17, USS Kearny was badly damaged after a torpedo attack and USS Reuben James, sunk on the 31. By force, president Roosevelt ordered to place the Coast Guard under supervision of the US Navy, normally a wartime measure, symbolic of the level of tension and commitment before December. None expected the war to start on the other side. Designed for the Atlantic, USS Long Island was sent to the Pacific…

Genesis of the Long Island conversion

HMS Audacity: Almost the first (1941)

The advantages of aviation to spot U-Boats and intercept spies such as the FW-200 Condor, while fleet carriers were needed elsewhere, litterally screamed for the construction of light, cheap carriers quickly converted from existing hulls, fully dedicated to convoy escort. Being the pioneer of aircraft carriers, the Royal Navy already looked at the idea in 1939, but nothing really came from it, at least until late 1940 when the situation in the Atlantic was definitively degrading fast. However, British industrial capacities, at full, could not spare men and materials for any of these hypothetic escort carriers from scratch. However, fate intervened. SS Hannover (5537 Tjb), a recent (launched 29 March 1939) German freighter, was captured in the Dutch Indies in March 1940. The admiralty found to be the perfect candidate for such conversion. Renamed Empire Audacity, she served little time under her new maritime board.

She was very quickly converted (Between January and June) at Blythe Shipyard to be sent back in the Atlantic as soon as possible, as an experiment: To simplify design and conversion time, There was no island superstructure, a wooden flight deck with arrestor cables built over the main deck, but no catapult, no lift, nor true hangar. The barebone CV, renamed HMS Audacity, carried only six aircraft on board, stowed at the stern and covered by tarpaulins when not in use. Her large holds stored fuel and ammunition aplenty, well beyond the need of its small air group, so she could also act as supply ship and continue her service as merchant vessel as well. She entered service in June 1941, a mere 19 days after USS Long Island was commissioned, but was way more primitive in its general concept. Her career was short, as she was sank by U 571 on 21 December 1941. The idea was to resurface rapidly with many more conversions in this style, the MAC or “merchant aircraft carriers” of the “Empire class” (not to be confounded with the “merchant auxiliary cruisers”). Having little merchant vessels to spare, the admiralty turned to the US to procure them six siblings. They were suprised to find that the Bureau of Ships already worked on the subject since March…

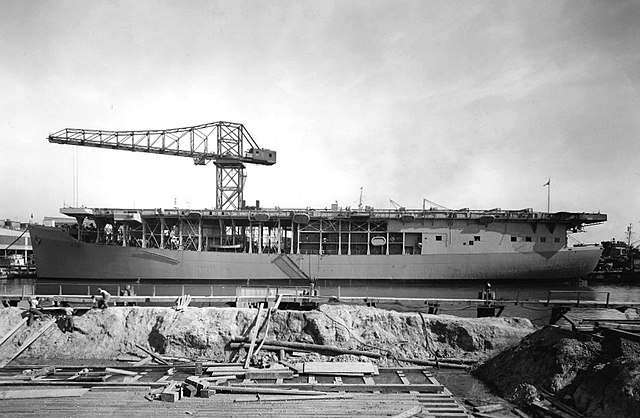

In search of a suitable hull

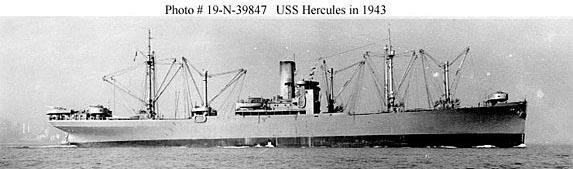

USS Hercules, the first C3 cargo in 1940

The Mormacmail was a C3 Cargo, requisitioned by the US Navy on 6 March 1941. By that time, the USN was not yet implicated in active convoy escort. So the main concern back then was for the admiralty to just experiment and conduct tests, to prove the feasibility of aircraft operations, from converted cargo ships. The idea was tempting indeed. The need to replace British merchant losses in 1941 led to the United States Maritime Commission (1936) to define new type of standard cargo to be built faster and cheaper. Back in 1936, the goal to to design and build five hundred modern merchant cargo ships, in order to replace World War I vintage vessels, many of which has been previously defined by MARCOM’s preecessor, the United States Shipping Board. The war just came out to make this process more urgent.

The C3 Cargo emerged from this program. It was one of the six standards setup by MARCOM: The Liberty ships, Victory ships, and earlier Type C1, C2, C3, C4 freighters and T2 tankers. In 1945 this represented a grand total of 5,777 ocean-going merchant and naval ships. Many would serve almost until the 1990s. They found many roles: Assault and Command ships but also escort aircraft carriers. The C3 was a rather large cargo, as the third type. The C1 (1937) was a 3,805 to 6,000 tonnes GRT, the C2 (1938) was a 5,443 DWT (AF-11), and the C3 (1940) was defined as a 7,800 gross tons vessel with a Displacement of 12,000 deadweight tons.

The C3 cargo became one of the most common standard freighter in WW2: 465 were built during the war. This was more than other types, but less than victory and Liberty Ships, the workhorse of sea trade during the war. This size of th C3 was indeed well suited, as it was found, for the conversion into the Bayfield and Windsor-class attack transports, or the Klondike-class destroyer tenders, among others, and to test the waters for an escort aicraft carrier (In the USN nomenclature, “CVE”, “E” standing of course for “Escort”.

In 1940, indeed, U.S. Admiral William Halsey already recommended construction of naval auxiliaries for pilot training. In early 1941 the British, in need for new carriers, asked the U.S. to build six on an improved “Audacity” type design, but at that time, a design was already prepared by Bureau of Ships: On 1 February 1941, the United States Chief of Naval Operations gave priority to these “naval auxiliaries” for aircraft transport and they were referred at first as “auxiliary aircraft escort vessels” or “AVG”, in February 1942. This was changed as auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV) on 5 August 1942, and finally CVE.

USS Long Island was followed by USS Archer, a near-sister ship, and the Avenger and Bogue-class escort carriers. They also inspired the construction, later, of the “Jeep Carriers”, not based on an existing design but built from the keel up, still in record time. Most of the recipes used by BuShips in the conversion of the former collier Jupiter, renamed USS Langley, were reused to gain time.

Design

Blueprint of the Long Island in 1944, after receiving her light AA.

As completed she saw her main deck used as hangar deck, a common feature for aircraft carriers, and the deck mounted above. The deck was actually shorter than the hull, missing about 10 meters aft to the stern and the forward deck ending about 20 meters short of the prow. The latter was tall and guaranteed an excellent heavy weather tenure. The freed space was used for the crew to man the winch and harbor rigging, greased the anchors chains. The aft part of the bow deck ended where the hangar started and two 3-in guns were placed on the broadside, one each. The deck was actually not flat, but accused a slight recess backwards (the front was about one meter higher than the aft landing deck). This was to ease braking by gravity for landing planes of a shorter surface. The slight angle forward also helped planes to take off also.

The hull alongside the three-level high hangar was semi-enclosed along the forward part of the hangar, with side galleries, and utility intermediate decks fitted with two small boats and many inflatable rescue boats. The most part of the forward hangar was open, like on USS Langley, the closest conversion made so far. The small boats were winched to the sea under a portico. The aft part of the hangar deck was entirely closed. The was an overhang also over the poop, leaving space to place the main defensive gun of the ship: A 5-in/51 standard dual purpose gun.

The short runway was separated in twi area: The forward section, about 1/3 of the total which comprised a catapult on the left, leaving the right free to srore planes, waiting to be catapulted. The 2/3 aft deck were reserved for landing. It comprised twelve arrestor hooks: A first group of four aft of the rectangular lift, one above it, and four far apart, followed by three extra close “emergency cables” behind the catapult, in case a heavier plane missed all the former. As said above, there was no island, instead a pole past was installed left of the flight deck, supporting a platform o which was installed an air surveillance radar, and aft, another mast carrying antennae and another small surface radar. Large communication antennae were installed aft and two cranes on either side of the flight deck.

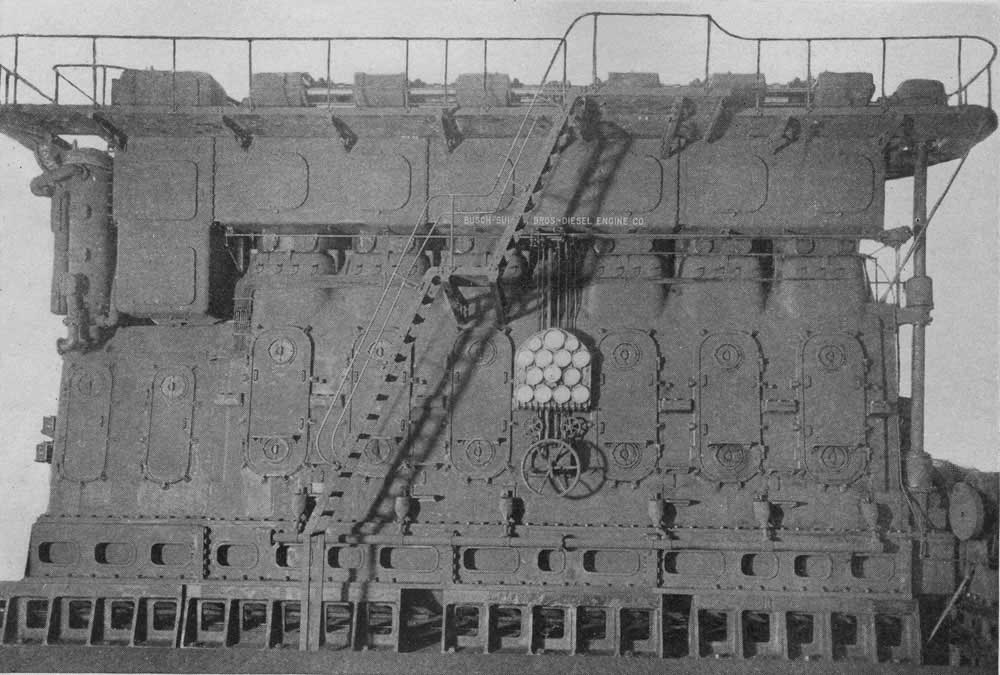

Machinery

A main complaint of the first commander of the ship, as a C3 cargo she kept the same machinery: Four Bush-Sulzer diesels, which provided a modest output of 8,500 shp( 6,300 kW), for a maximum speed of 16.5 knots. This was well suited for convoy escort, but barely enough to distance a surfaced U-Boat. She also carried 1,365 tons of diesel oil, providing her with a range of 8,000 nm. She had a single shaft and thus was not very agile.

Armament

The ship was completed in June 1941 with three main artillery pieces: The main 4-inches 50 caliber Mark 9 standard of the USN (102 mm) aft of the ship in an enclosed cradle at the poop. The arc of fire was about 180° aft, but a bit more due to its location and the clearance gave by the high overhanging deck.

This armament was completed by proper long range AA guns, a pair of standard 3-inch/50-caliber gun Mark 20. They were placed on either side of the stern deck: 15–20 rpm, 2,700 ft/s (820 m/s) mzv, range 14,600 yards, 30,400 ft AA ceiling.

There was no light armament, which was added later, four 12.7 mm AA (Browning M2HB) during a 1942 refit and later placed on all four angles of the flight deck, and in 1944, twenty 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns under masks, placed in tandem in five side sponsons along the deck, high enough to fire at any angle and cover the whole flight deck.

USS Long Island Air groups

Between her hangar capacity and deck capacity she could carry as aplan transport up to 30 aircraft, a role she took in 1944.

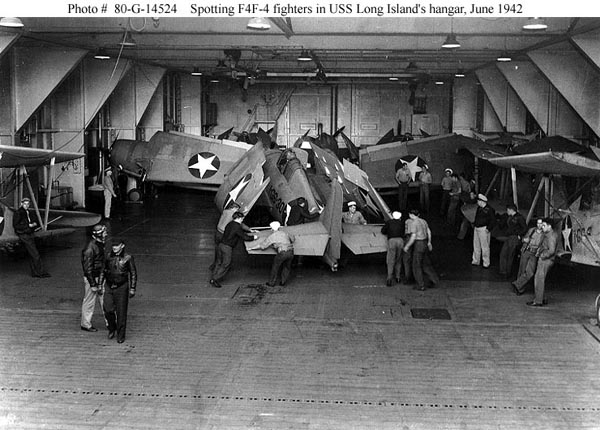

She had limited capacity compared to the USS Charger, and both carried relatively small planes (no TBD Avenger for example), and it must be said, second-rate planes no longer used on fleet carriers, which had the best air groups available. In June 1941, USS Long Island operated ten Curtiss SOC Seagull, the wheeltrain version, and six Curtiss SBC Helldiver.

The SOC was a wheeled version of a standard observation floatplane served as reconnaissance plane and bomber. The Curtiss SBC was also a biplane, the standard navy dive bomber before its replacement by the Devastator.

Brewster F2A Buffalo: 8 Brewster F2A Buffalos and 8 Curtiss SOC-3 Seagulls, so 16 planes in all constituted the carrier air group by December. At last she received a monoplane fighter. The second as fighter. The reputation of the F2A-3 however, was disastrous due to numerous additions making it overweight, and having a too fragile wheeltrain.

VS-201 or Scouting Squadron 201 was a training unit, operating on USS Long Island. In 1943, they started to be replaced by F4Fs -to great relief of the crews. USS Long Island’s Wildcats stayed in service basically until the end of her service in 1945, going from the F-3 to the F-4 standard. VMF-211 then had its remaining Buffaloes relegated as a local defence on Palmyra Atoll, possibly at the end of the summer 1941. In June 1944 as shown in a photo, she carried 21 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, 20 Douglas SBD Dauntless scout bombers and two Grumman J2F Duck utility planes, all stored on her deck and later disembarked via cranes on delivery.

In punctual operations, she also carried the Douglas SBD Dauntless, when acting as “taxi”, delivering them to Guadalcanal, Henderson field in August 1942. They never operated onboard as a permanent unit.

Accident with a F2A-3, VMF-211, USS Long Island, 25 July 1942.

Seagull SOC-3A from VS-201 onboard AVG-1, 16 Dec. 1941

Grumman F4F-4 onboard USS Long Island, 1943 (author’s illustration)

USS Long Island Norfolk Naval Shipyard Portsmouth Virginia 18 October 1941

The relatively cramped hangar of CVE-1 is evident here, as she carried the nimble F-4F in June 1942 (Navsource).

USS Long Island Pearl Harbor Hawaii on 17 July 1942

USS Long Island underway, 25 May 1943

USS Long Island underway Puget Sound Washington 11 February 1944

USS Long Island, San Francisco Bay, 10 June 1944

USS Long Island at anchor, Ulithi circa 1945

The USS Long Island in service

In the months prededing the attack on Pearl Harbor, from June to December, USS Long Island operated off Norfolk, Virginia, experimented with landings and take-off operations for the US Navy. The goal was to prove the feasibility of such operations from converted cargo ships. Gathered informations were reported to the admiralty, which confirmed further conversion orders, and generated specific documentation for pilots and crews on such reduced platforms. All in all, USS Long Island greatly improved combat readiness for future small escort carriers, called by pilots “baby flattops”.

After December 1941, CVE-1 escorted a convoy to Newfoundland, carrying planes, and qualifying carrier pilots at Norfolk, before sailing our for the West Coast on 10 May 1942, crossing the panama canal and reaching San Francisco on 5 June 1942. CVE-1 joined on arrival Admiral William S. Pye’s Task Force One (TF 1). The latter comprised seven battleships, survivors or Pearl and transferred from the Atlantic, providing air cover at sea. TF 1 was tasked to protect the US West Coast, but also to beef up Admiral Chester Nimitz’s forces after the Battle of Midway. USS long island however left TF 1 on 17 June, returning to the West Coast to resume its earlier role of carrier pilot training. Like USS Langley, she specialized in training CVE pilots for most of the remainder of the war.

USS Long Island departed San Diego on 8 July, heading to Pearl Harbor, reached on 17 July. She trained south to Palmyra Island, and loaded two squadrons of USMC aircraft bound for the South Pacific (Notably Guadalcanal), reaching her deployment area on 2 August and reaching Fiji on 13 August. She steamed to an area 200 mi (170 nmi; 320 km) southeast of Guadalcanal to launched the 19 Grumman F4F Wildcats and 12 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers she carried, and these planes were te first to land of the recently reclaimed Henderson Field. They became instrumental in the subsequent operations over Guadalcanal, achieving an lmpressive war record and generating aces. USS Long Island retired to safety while being reclassified ACV-1 on 20 August and reached Efate Island in the New Hebrides (23 August 1942).

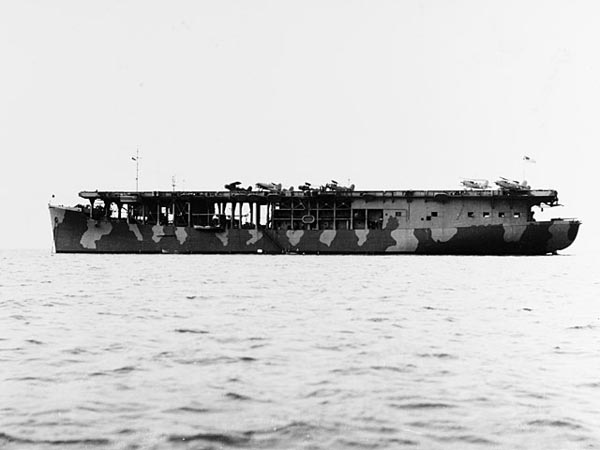

Long Island in November 1941 showing her air group on deck, Seven SOC Seagull floatplanes and one F2A3 Buffalo fighter.

USS Long Island operations at Guadalcanal were later immortalized in the movie “Flying Leathernecks”. The aircraft carrier returned to the West Coast on 20 September and all along the year 1943, she spent her time training escort carrier pilots at San Diego, reclassified in between CVE-1 (15 July 1943). In 1944 she interrupted her training service to be used as airplanes/ aircrew transport, from the US West Coast to outposts in the Pacific, to prepare subsequent operations. The war ended as she was returning back to pick up soldiers, sailors and materials afterwards, back home: This was her participation to the Operation Magic Carpet.

Post-war career was a second, civilian life. It was theorized during her conversion in 1941 that it would be easy to convert her back as a civilian vessel. She still had value as such, being a recent ship. As an aircraft carrier however she was no longer needed in her role, largely seen as transitional and dictated by war operations only. She was decommissioned on 26 March 1946, at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Stricken from the Register on 12 April 1946, she was sold at auction to the Zidell Dismantling Company, Portland, Oregon, on 24 April 1947. However on 12 March 1948, Canada-Europe Line, which was searching for affordable hulls to use, like many other postwar maritime companies, purchased the ship for conversion to merchant service.

The conversion was performed quickly and completed in 1949. She started service under a new name, Nelly, as an immigrant carrier on the Europe-Australia-Canada lines. In 1953, she was renamed Seven Seas and by 1955, chartered to the German Europe-Canada Line. On 17 July 1965, a massive fire broke out on board. She was towed to St John’s in Newfoundland and later repaired. She sailed the last time on 13 September 1966 and purchased again by Rotterdam University. She was used as a floating students’ hostel until 1971. She became afterwards a migrant hostel, until 1977, but by then the old hull was decrepit and she was scrapped in Belgium.

USS Charger: Conversion and design differences

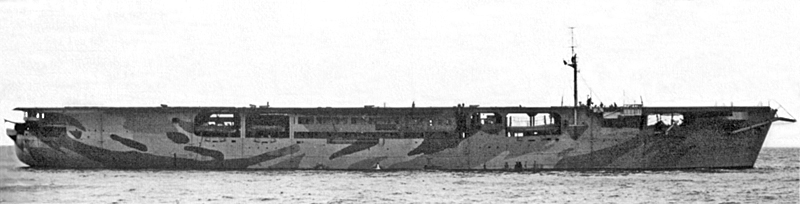

USS Charger in port, June 1942

The United States Maritime Commission (MC) granted Sun Shipbuilding funds to built four C3-P&C cargo/passenger liners, on 29 November 1939. Unit cost was $2,720,800, and among these, “Rio de la Plata” was the third sister-ship built at this yard in Chester, Pennsylvania, for the Moore-McCormack company. This modified C3 type was meant to be used by the Moore-McCormack’s American Republics Line operating on the east coast and South America. Remarkably, she was the first large U.S. passenger ships with diesel engines: Two six-cylinder Sun Doxford diesels for a total ouptut of 9,000 sho and of course, a single screw propeller through reduction gears. Design speed was 17.5 knots (20.1 mph; 32.4 km/h). She was fitted also to carry “only” 196 passengers, while all cabins had air conditioning, another innovation. As passenger/cargo ship she had a 17,500 ton displacement, 9,800 DWT. Her size was 492 ft (150.0 m) long overall, 465 ft (141.7 m) between perpendiculars. Air conditioning was also extended to the cargo compartments to avoid moisture, in total 440,000 cubic feet (12,459.4 m3) and 40,000 cubic feet (1,132.7 m3) of refrigerated space. Passengers benefited from 76 staterooms, 22 single cabins, 34 double cabins and 20 cabins with a private veranda.

Her keel, as “Rio de la Plata” or MC hull 61 (yard hull 188) was laid 19 January 1940. The passenger design was however not completed as she was requisitioning by the USN when the war broke out. She has been previously launched on the 1st March 1941, and completion was near when she was taken up for conversion. Initial delivery was planned for 2 October 1941, and the launch was sponsored by Mrs. Felipe A. Espil. The requitisition was performed on 20 May 1941, by the US Maritime Commission. The “combiliner” was to be converted, but design conversion plans were not established yet, so the ship stayed, waiting for her fate until 1st August 1941. It was establish that Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. in Virginia would take on the conversion process, and the hulls of the four ships were towed there. Conversion as escort aircraft carriers as asked by the British, was secured as soon as designs were ready.

The Conversion took place thus from September 1941 to March 1942, so about seven months, much longer than for the USS Long Island. The conversion process was also a prototype for the Bogue, Attacker and Ameer classes. Compared to CVE-1 differences were considerable, as the new ships were slightly larger and were given an island for command and control from the beginning. This was a small structure overhanging to the left side, comprising three decks (radio room, map table, plotting room) and an open bridge. The main command bridge was situated below (third level), with windows. Aft of this island was fitted a sturdy lattice mast to support a larger SC10 radar aerial, navigation radar, radio interception antenna, plus communication antennae.

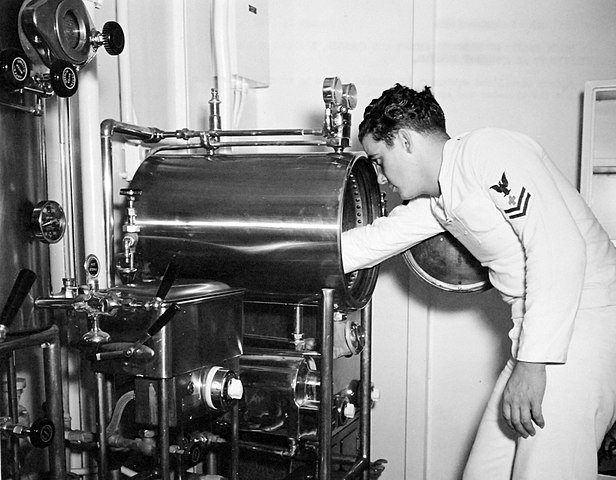

Modern sterilization equipment aboard USS Charger, 1942

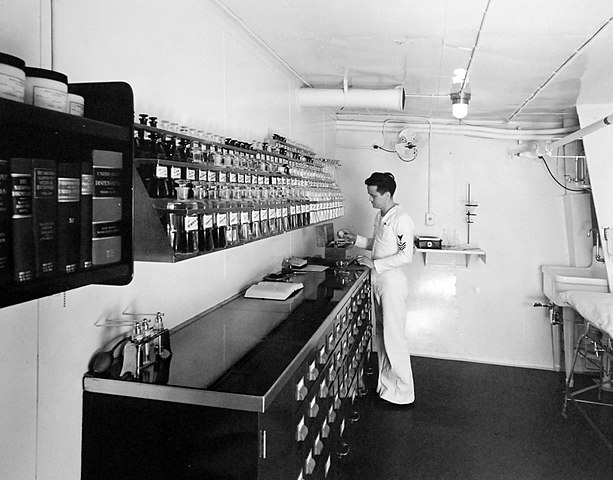

USS Charger preparing a prescription in the ships dispensary, 1942

The hangar was built the same way as for the USS Long Island, above the main deck, fully enclosed aft with windows and a forward part with recesses for utility spaces and inflatable boats flight. It was a bit higher than for the VCE-1 deck, allowing to suspend a plane under the roof if needed. But moreover the compartimentation was completely overhauled. The workship space for example, and many compartments formerly in the hangar were moved below decks, maximizing the hangar space. Indeed, as specified by the admiralty to BuShips, the new CVE, in addition to an island, was to possess at least twice as much planes, so at least 24 (16×2) compared to CVE-1. In fact engineers exceeded this figures, as a total of 36 planes, so almost thrice what was previously carried, is often stated (see below). Many design revisions were also made to improved access to ammunition and fuel lines (Aircraft fuel stowage: 341,000 liters) and prepare the planes before lifting them on the deck. The air conditioning system was also kept, to great comfort for the crews. All these modifications explains her lenghty conversion. It was considered such as success that BuShip was ordered to apply the recipe to all subsequent C3 hull-based CVE conversions. But she was the prototype for the conversion of about 30 C3 ships, with a major difference though: She was the only one without a raised forecastle.

USS Long Island and Charger differences explained in this ONI plate

USS Charger was also given like Long island, a lift placed on the centerline aft, but much closed to the end of the flight deck compared to CVE-1. There was also the same catapult, installed the same way on the left of the forward deck, leaving spaced for parked planes on the right. As Long Island, she had many arrestor cables all along the deck, up to the catapult. There was a first serie of nine cable, heavenly space, with a single one above the lift (shich needed to be loosened to allow acess to it), and a serie of five closer cables close to the catapult, acting as emegency cables, plus a foldable net. This allowed in principle relatively havy planes to land if needed. Armament-wise, the same principle was repeated, with a main gun aft, cenrerline on the poop deck and two side 3-in AA guns forward on the main bow deck. The overhang of the deck was about the same so to allow a minimal arc of fire for this defense. Light defense comprised ten 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon guns inside sponsons along the flight deck’s sides: Plans showed five sponsons on each side with the same locations, but two in tandem for the island’s side. It seems that due to her role this armament was never augmented. The main armament stated by Conways is three 4-in guns instead of a single one. Plans however only shows a single one. It was established as a 5-inches/38 caliber Mark 12 gun instead of the 4-in, making the ship more efficient in case of a naval fight (which indeed happened when Taffy-3 was attacked at Leyte). The two forward 3-in/50 (76 mm) guns Mark 20 were placed also in two sponsons overhanging on both sides, giving them an even better arc of fire compared to CVE-1.

USS Charger CVE-30 specifications (1942) |

|

| Dimensions | 150 x 21.18/33.88 x 8 m (492 x 70/111 oa x 26 ft) |

| Displacement | 8,000 light/11,800 tons standard, 15,126 tonnes FL |

| Crew | 856 |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft, 2 six-cyl Sun Doxford diesels, 9,000 shp |

| Speed | 17.5 kn (20.1 mph; 32.4 km/h) |

| Range | 26,340 nm at 15 knots |

| Armament | 5in/38, 2×3in/50, 10x20mm AA |

| Air group | 36* |

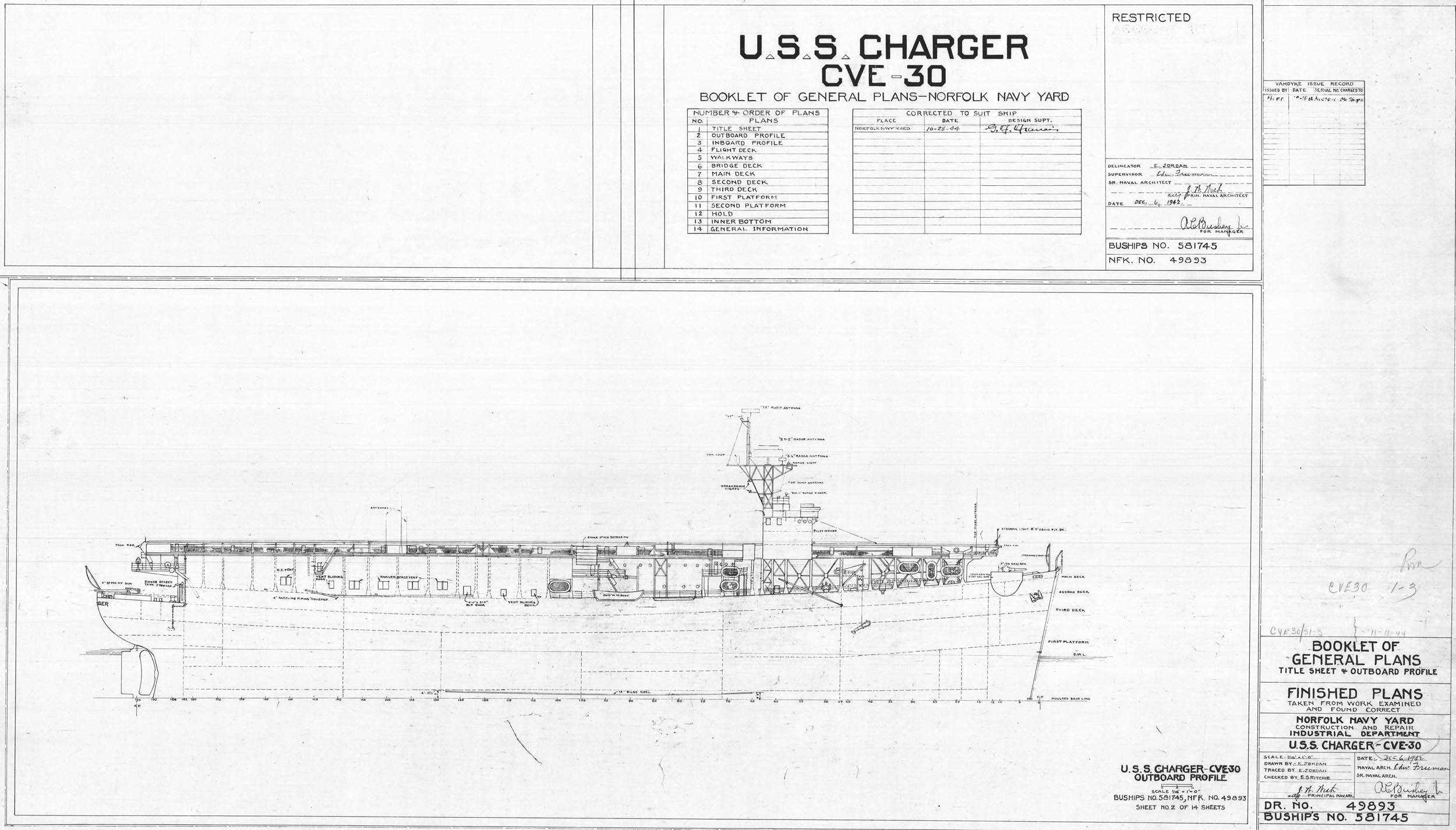

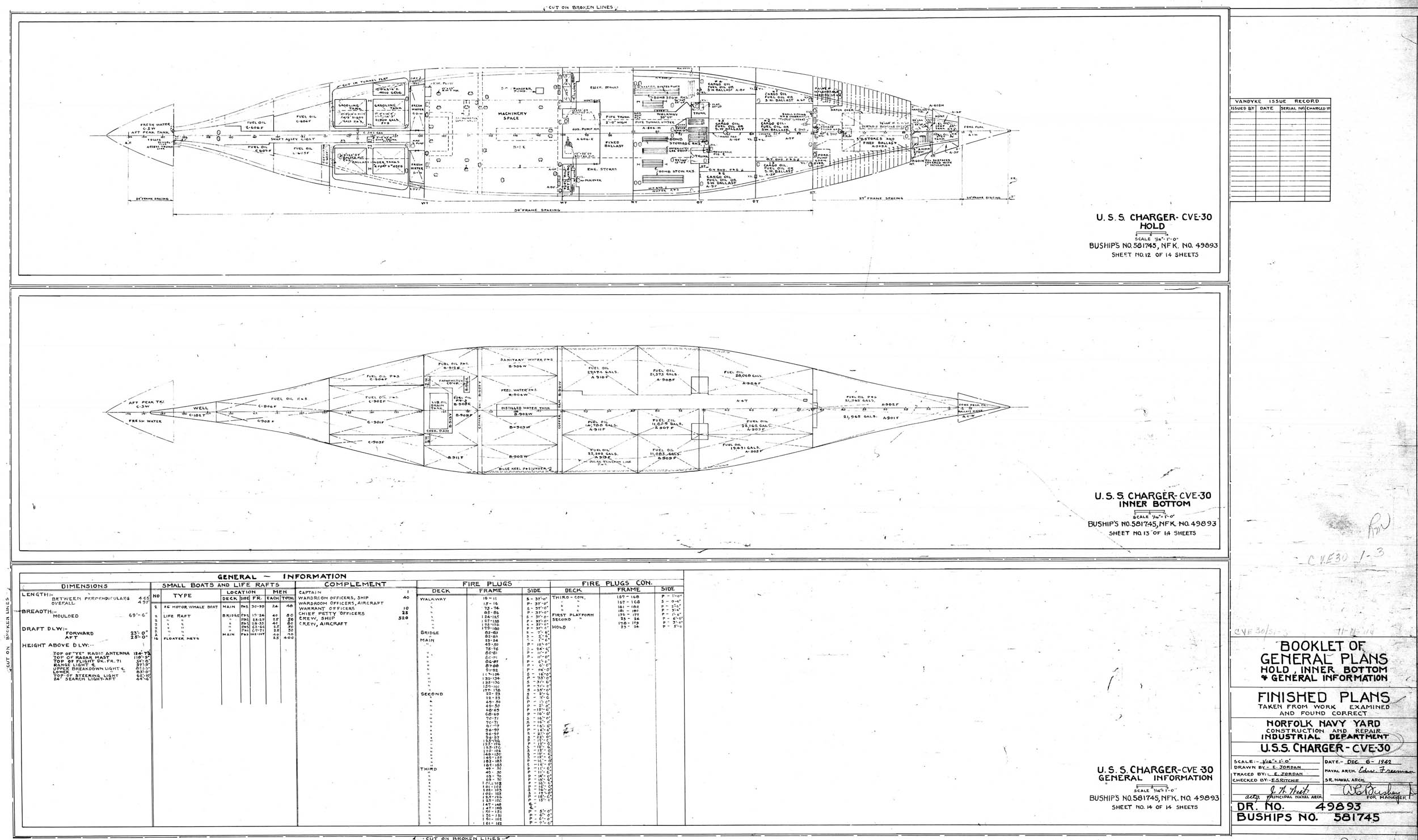

USS Charger, blueprint, outboard profile 1942

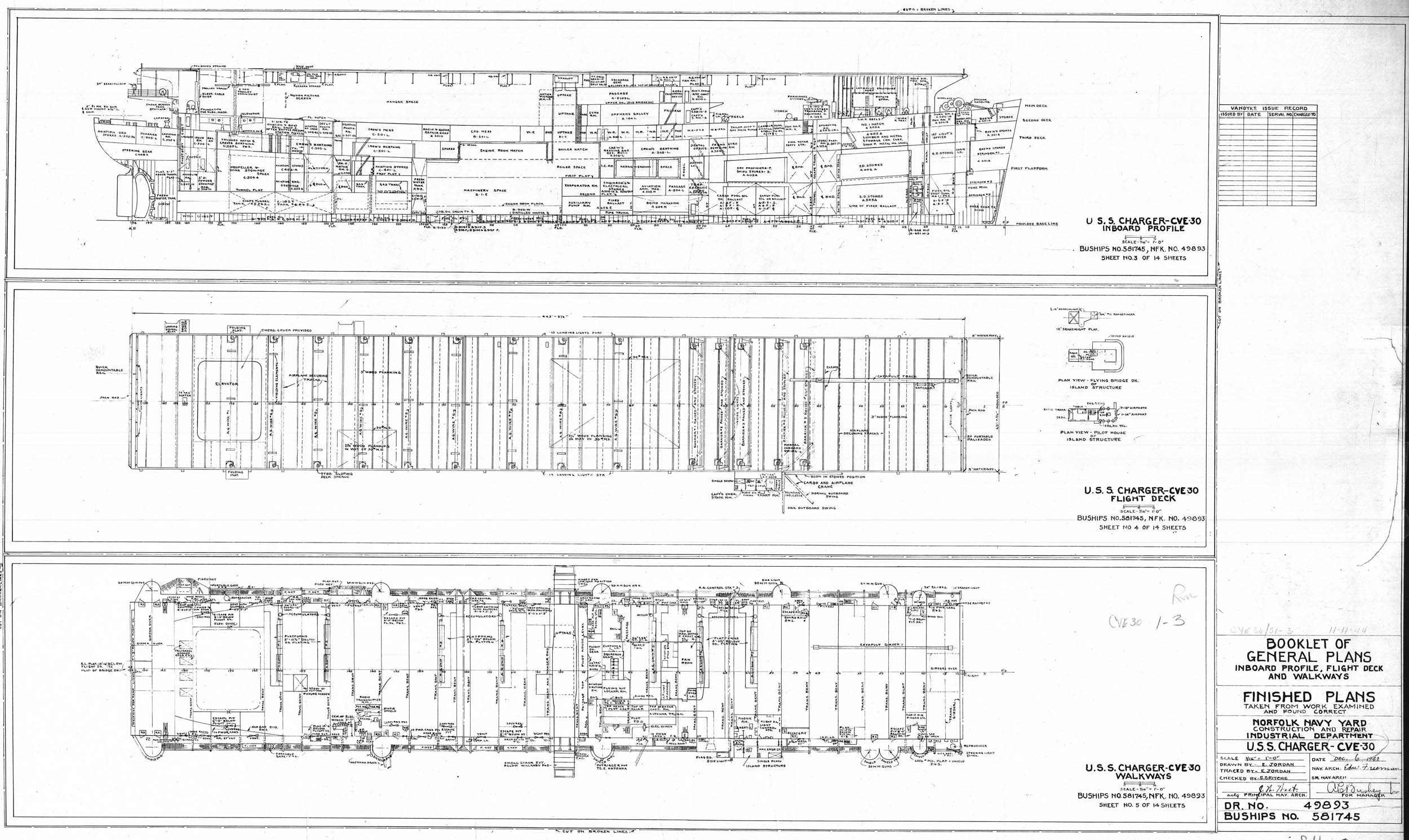

USS Charger, blueprint, inboard profile, flight deck, walkways

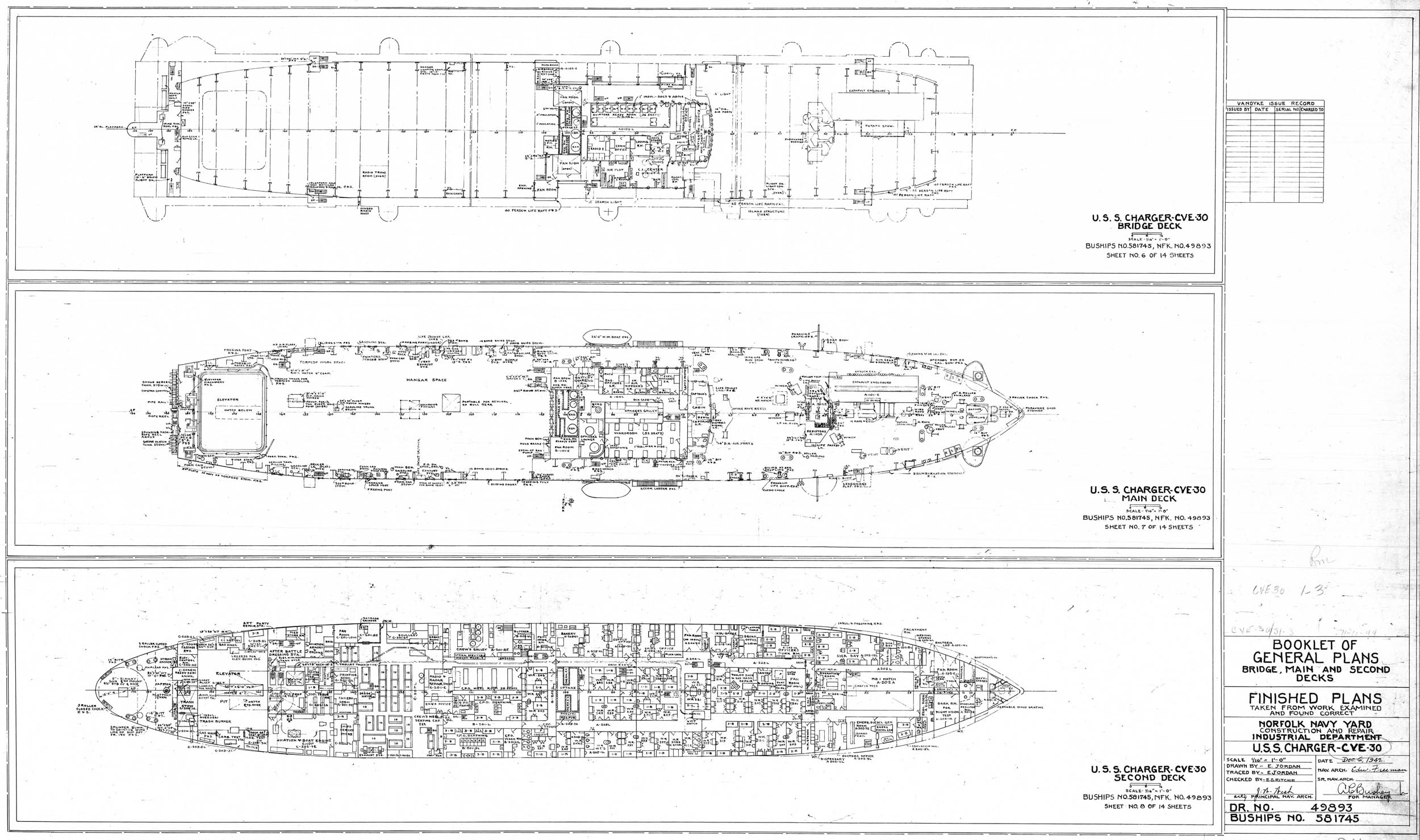

USS Charger, blueprint, bridge, main and second decks

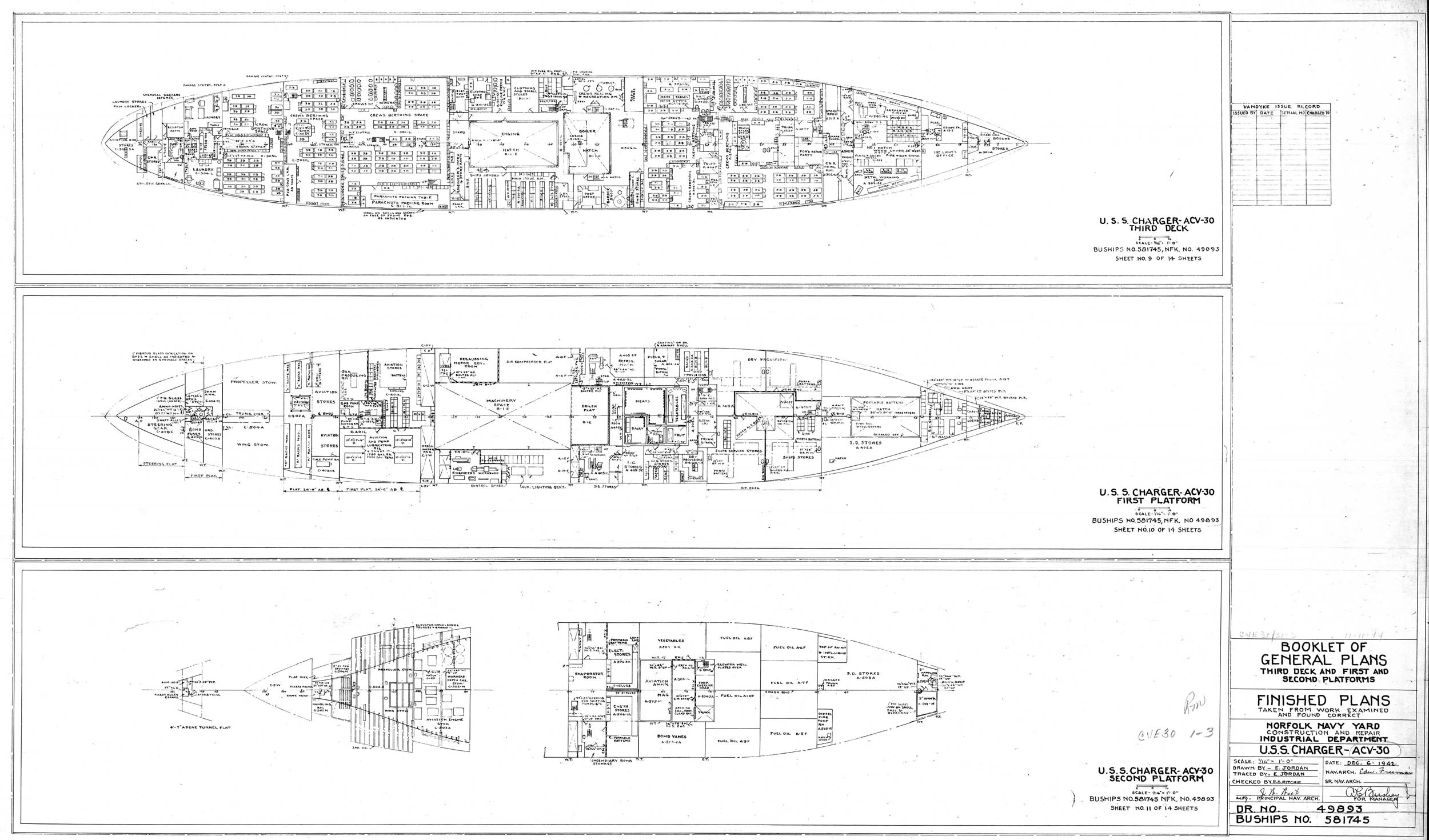

USS Charger, blueprint, third deck, two platforms

USS Charger, blueprint, hull bottom decks

USS Charger’s Air groups

Vought SB2U-2 of VS9 onboard ACV30 USS Charger, circa 1942.

Apart the Vindicator, allowed by the larger capacity of the ship, USS Charger also of course carried the F4F Wildcat, until the end of her service in 1945. Since she was completed and operational in the summer of 1941, she was given a more modern air group, comprising at first F2A Buffalo fighters and SOC Seagull reconnaissance planes (repartition unknown). Later in 1943, the F2A were replaced by the F4F. The composition is unknown but the ship being used for training, all types in service onboard the Bogue and Sangamon, and later Casablanca and Commencement Bay types were used on board. She also carried the TBF-1 Avenger and Curtiss SBC Helldiver as well as the Vouht F4U Corsair as shown in photos and videos. The former was the subject of a famous crash on deck photographed 23 March 1943. BuNo 00593 (ENS Richard J. Walsh, USNR) hit the port catwalk on landing, causing major damage to the plane but no injuries fortunately. She also trained pilots flying the Ryan FR-1 Fireball in 1944–46.

CVE-30 underway 1943

USS Charger at anchor, June 1942

Debunking the very large CVE-30 air group

The number of 36 aircraft given is subject to caution of course: The Bogue class only carried 28, and the British CVEs only 24. The Independence class only 30. 36 is almost the same capacity carried by the much larger light British fleet carriers of 1944 (37). The explanation for this aberration should be that the normal hangar capacity was not that different than the other CVEs so we can only guess that this figure started was the maximal possible as a plane carrier: With all planes stacked on the flight deck, plus those inside the hangar. When considering those stacked on USS Long island’s deck in 1944 when she acted as plane taxi, 42 were seen, almost all with wings folded. So we can assume 36 was the maximal capacity figure of planes stacked on the deck to left space both for landings and catapulting more, with in addition, the hangar full. If we assume 8 planes on the deck, which seems reasonable to not hamper operations and the rest in the hangar (28), we have a more plausible record. This tells that the usual figure capacity given is related to the hangar capacity, not the maximal capacity. In case of heavy and icy weather for example, the entire air group whould be ideally protected inside the hangar. Since USS Charger was a training carrier we have therefore to assume the figure given is related to the fact she carried always excess planes on her deck, without allocated space inside the hangar. Chesapeake Bay’s location made it ideal for year-round training, and never impacted by heavy weather and icy conditions. As a usual practice also, some training air groups were based on land, but still trained to land and take off from the carrier close to the coast, also explaining the larger figure.

The USS Charger in service

USS Charger, AVG-30 underway 1942

F-4F Wildcats onboard CVE-30, May 1944. One is just stopped, while a second one is doing an approach circle, hook down.

USS Charger underway in 1945

USS Charger’s operated from March 1942 in Chesapeake Bay as a training aircraft carrier and their support crew for escort carrier operations in the Atlantic (mostly) or Pacific, a bit like her sister ship Long Island. But she carried out this role almost until the end of the war. She played an invaluable role in having well trained crews for the efficient escort of all the convoys that transited through the Atlantic, tasked to cover it against any action from hostile submarines, as part of combined escort carrier groups. These planes were mostly geared towards ASW operations and reconnaissance, so fighters were not a priority and were fewer in numbers. Most of the time, Atlantic CVEs had always a few F4F Hellcats, until the end of the war. They were also often from 1944 fitted with rockets to attack surprised U-Boats.

USS Charger was denominated ACV-30 from 20 August 1942, and CVE-30 from 15 July 1943. She only left Chesapeake Bay for two “aicraft taxi” runs, to Bermuda in October 1942, and to Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, in September 1945. After a service which earned her no battle stars, but the American Campaign Medal and World War II Victory Medals, she was decommissioned at New York on 15 March 1946.

Like CVE-1, USS Charger had no use in the postwar context. She did not pass the “sold for scrap” stage and was directly sold in auction for merchant service. She was awarded on 30 January 1947 by the Vlasov group. Her conversion was considerable, as she became the passenger liner Fairsea, for the Italian managed Sitmar Line. Her entire superstructure above deck was completely modified after several years, and successive accommodation upgrades allowed a very long service, mostly as a migrant carrier from Europe to Australia. She experienced a severe engine-room fire between Tahiti and Panama on 29 January 1969. The lack of spare parts at the time was cited as a fatal case for her retirement. She was sold for scrap in Italy in 1969, last former CVE still in existence at that point.

MS Fairsea, Sitmar Line, after refit – Promotional painting.(navsource).

Read More

Robert Gardiner, Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Pacific American Steamship Association; Shipowners Association of the Pacific Coast (January 1939). “Sun Gets Four C3 Motorships”. Pacific Marine Review. San Francisco: J.S. Hines: 54. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Colton, Tim (28 March 2014). “Sun Shipbuilding, Chester PA”. ShipbuildingHistory. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Pacific American Steamship Association; Shipowners Association of the Pacific Coast (October 1940). “New Combination Liners for American Republics Line”. Pacific Marine Review. San Francisco: J.S. Hines: 30–31. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Karsten-Kunibert Krueger-Kopiske (2007). “Outboard Profiles of Maritime Commission Vessels — The C3 Cargo Ship, Sub-Designs and Conversions”. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Pacific American Steamship Association; Shipowners Association of the Pacific Coast (September 1941). “Navy Takes Rio Ships”. Pacific Marine Review. San Francisco: J.S. Hines: 80. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Pacific American Steamship Association; Shipowners Association of the Pacific Coast (September 1941). “Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company”. Pacific Marine Review. San Francisco: J.S. Hines: 106. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Naval History And Heritage Command. “Charger”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History And Heritage Command. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

“10 pound Pom arrival lists go online”. Perth Now. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

Sawyer, L.A.; Mitchell, W.H. (1981). From America to United States: The History of the Long-range Merchant Shipbuilding Programme of the United States Maritime Commission. London: World Ship Society.

Context on warfarehistorynetwork.com

USS Charger on navsource

C3 types on usmm.org

C3 Cargo – the Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

Navsource about CVE-1

Navsource about CVE-30

historycentral.com

cradleofaviation.org

uss charger CVE30

Plans of USS Charger

Moore-McCormack Mormacland

USS Archer’s career

On history.navy.mil

On hyperwar Online

On screanews.us

Table 21 – Ships on Navy List June 30, 1919

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command

U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation photo No. 2003.001.323

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign