United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier

United Kingdom – Aircraft CarrierWW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classThe Courageous Class were two light battlecruisers intended for an Operation in the Baltic in 1917 pushed by Sir J. Fisher which never materialized and instead, they were converted as aircraft carriers, completely rebuilt after the treaty of Washington. With HMS Furious and Argus they pioneered the interwar fleet air arm but had short careers during WW2, being sunk in the Atlantic in 1939 by an U-Boat (the first British warship sunk in WW2) and Norway in 1940, by gunfire.

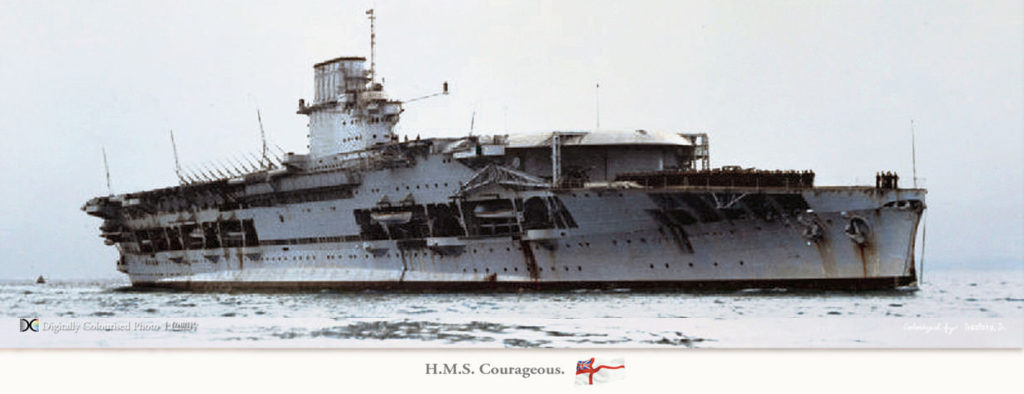

The Courageous class conversion

The three battlecruisers were in the reserve by 1919. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 limited capital ship tonnage, therefore choices were made to keep three battlecruisers: The Hood then just completed and the two Repulse. The Furious was already transformed into a CV, so the lighter Courageous was excluded from the tonnage and placed in the 66,000 long tons surplus to be converted into aircraft carriers. For the the Royal Navy it was a wise choice due to their high speed and similarities with the Furious. They were near sister ships.

HMS Furious in WW1 already showed th e way: She had been fitted with a flying-off and landing deck, a solution showing the central funnel and bridge were not ideal and created strong wind disturbances. Furious was laid up after the war and rebuilt as a full-lenght aircraft carrier June 1921-September 1925. Her design was partly based on the Argus (three years old) and Eagle, which barely completed, already made 143 deck landings in preliminary sea trials. Her blueprints and reconstruction were used as models for her near-sisters, Glorious and Courageous, when taken in hands in turn for conversion.

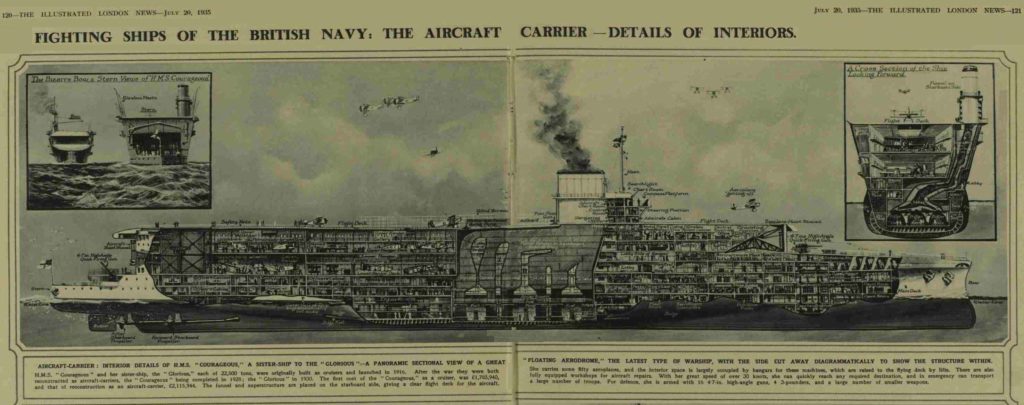

Glorious and Courageous’s conversion started at Devonport on 29 June 1924 (Courageous), and Rosyth on 14 February 1924 (Glorious). The latter later was moved to Devonport for completion in place of Furious. The design was based on Furious, but a few improvements were made, based on the Furious experience. A two-storey hangar was built, each level being 16 ft (4.9 m) high, 550 ft (167.6 m) long, built on top of the former deck. The upper hangar level opened onto a short flying-off deck, below and forward of the main flight deck, a feature which was quite unique at the time and was not repeated, but inspired the Japanese for their own conversions. Two cross-shaped 46-by-48-foot (14.0 by 14.6 m) lifts were installed, fore and aft in the flight deck. A low island was constructed on the starboard side, containing the open navigation bridge, but also the flying control station. This island did not created much turbulence as initially feared, but it was cramped and wet in heavy seas. Fuel capaciy was increased gradually in 1939 to 34,500 imperial gallons (157,000 l; 41,400 US gal), to serve a small aircraft complement, in fact too small for effective operations in WW2. If not sunk early, they would probably had been used as fast aviation transports from 1942.

HMS Glorious 1935

Design of the Courageous class

The hull kept their overall length of 786 ft 9 in (239.8 m), but the beam was augmented by inwards sloped walls, to 90 ft 6 in (27.6 m) by 9 ft 6 in (2.9 m). The low draught was alo so increased of 2 ft (0.6 m), to 28 ft (8.5 m) deeply loaded. Displacement after conversion was 24,210 long tons (24,600 t) standard, 26,990 long tons (27,420 t) deeply loaded, an increase of 3,000 long tons (3,000 t). Metacentric height declined from 6 ft to 4.4 ft. Both hulls initially had a complete double bottom.

Propulsion of the Courageous class

The Courageous-class CVs initially had geared steam turbines, at the insistence of Jackie Fisher. They were Arranged in two engine rooms, for a total of four propeller shafts 11 ft 6 in (3.5 m) in diameter. They were fed by 18 Yarrow small-tube boilers placed in three separate boiler rooms. They were designed to produce a total of 90,000 shaft horsepower (67,000 kW) at 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2), but because of displacement increase, top speed fell to 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph).

Protection of the Courageous class

All but the armour protecting the barbettes were removed during conversion, and transverse bulkheads installed in the locations of the former barbettes. The flight deck was thickened to 0.625 inches (15.9 mm), and unlike other battlecruisers, high-tensile steel (HTS) had been used all around for their protection. The waterline belt was still 2 inches (51 mm) thick with HTS backed by a 1-inch (25 mm) thick mild steel skin to protect the interior from splinters. The middle two-thirds of the ship was protected also with a 1-in extension forward to the transverse bulkhead, short of the bow. The belt was 23 feet (7 m) total, with just 18 inches (0.5 m) submerged. There was a 3-inch bulkhead in front of the upper and lower decks and another where the rear barbette was. Four decks also protected the ship, varying from 0.75 to 3 inches (19–76 mm). The latter was applied over the magazines and steering gear. The Battle of Jutland urged to add 110 long tons (110 t) of extra protection around the magazines as well.

London Illustrated News, July, 20, 1935 – Cutaway of the Courageous class

Torpedo bulkheads were improved during the reconstruction, up to 1.5 in (38 mm) and there was now a shallow anti-torpedo bulge, integral to the hull. Its role was to prematurely detonate a torpedo before it hit the proper hull, and deflect the underwater explosion to the surface. The Italian Pugliese system was mater greatly inspired by it. However it was not deep enough to work properly and lack intermediate layers of compartments to absorb completely the blast. In the Pacific against the Japanese “long lance” super-torpedoes, they would have stood no chance, but against aerial torpedoes it was another story. The relative inefficiency of this system was shown when sunk by U-29.

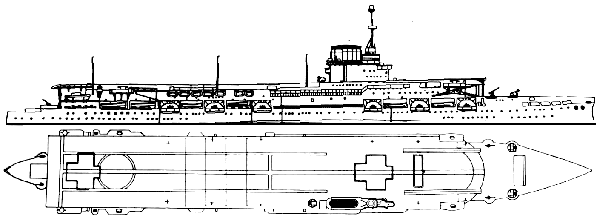

Various technical schemes of the Courageous class carriers

Armament of the Courageous class

While HMS Furious retained ten breech-loading BL 5.5-inch Mk I guns, five per side, a mix of anti-surface and anti-aircraft guns of various sizes was considered for the reconstruction of Courageous and Glorious by the Admiralty. In the end, it was chosen an all dual-purpose battery of of 16 QF 4.7-inch Mark VIII guns in single, high-angle mounts. One was placed on each side of the lower flight deck, another on the quarterdeck. The remaining were distributed along the sides, reducing their arc of fire and role mostly to deal with destroyers. These could depress indeed to −5° bu elevate to 90°. These guns fired a 50-pound (23 kg) HE shell at 2,457 ft/s (749 m/s). The rate of fire was circa 8–12 rpm, maximum ceiling was 32,000 ft (9,800 m), and maximum range of 16,160 yd (14,780 m) on the surface.

In the mid-1930s, both ships were refitted and received an addition of 2-pounder pom-pom mounts. Three quadruple Mark VII for Courageous (one either each side of the flying-off deck, one behind the island) and for Glorious, three octuple Mark VI mounts, placed in the same locations. Both CVs also received four water-cooled 0.50-calibre Mark III machine guns in the characteristic vertical tandem quadruple mounting. The latter elevated to 70° and fired a 1.326-ounce (37.6 g) bullet at 2,520 ft/s (770 m/s) for a maximum range of about 5,000 yd (4,600 m), reduced in practice for accuracy to 800 yd (730 m). This created a three-layered AA bubble, completed at longer range by the fighters.

Air group

Blackburn Blackburn Mark II

Avro Bison

In 1939, HMS Courageous had a complement of 807 officers and ratings, and the 403 men in her air group, which was built at first in 1926 around 48 aircraft due to the larger hangar size compared to Furious (36). In practice, there was one flight of fighter, called squadron from 1932: These were Fairey Flycatcher. Due to the “screening value” of carriers at that time, it was completed by no less than two of spotters for the fleet, made of Blackburn Blackburn or Avro Bison and one of the pure spotter reconnaissance Fairey IIID, plus two of torpedo bombers, equipped with the Blackburn Dart.

The ungainly Blackburn Blackburn and Bison were both designed in parallel in 1921, using the same Napier Lion engine. The fuselage shape was dictated by massive radiator below the engine at the front whereas the gunner/radio operator was placed aft of the pilot, with fuselage windows to observe the surrounding. The Bison served with the 421 and 423 Fleet Spotter Flight Fleet Air Arm and were retired in 1929, replaced by the Fairey IIIF. The Blackburn Blackburn saw a slightly lower production (44 vs. 55) and entered service later, in 1923 after the problems encountered by the Bison. The engine cooling radiator caused this slab-sided fuselage. They were pure spotting aircraft, with a defensive MG but no military payload. They were retired in 1931.

In between, the Fairey III replaced them.

In 1935 the air group was changed, with a squadron of fighters (Hawker Nimrod, Hawker Osprey) and one squadron of Blackburn Baffin torpedo bombers plus a squadron of Fairey IIIF spotters. In 1939-40, there was a single fighter squadron and two of strike aircraft (Skua and Swordfish) but this was adjusted for each mission. Contrary to the Furious, the Courageous class also flew the Fairey Seal, Blackburn Shark, and Blackburn Ripon.

Fairey Seal

Blackburn Ripon launching a torpedo

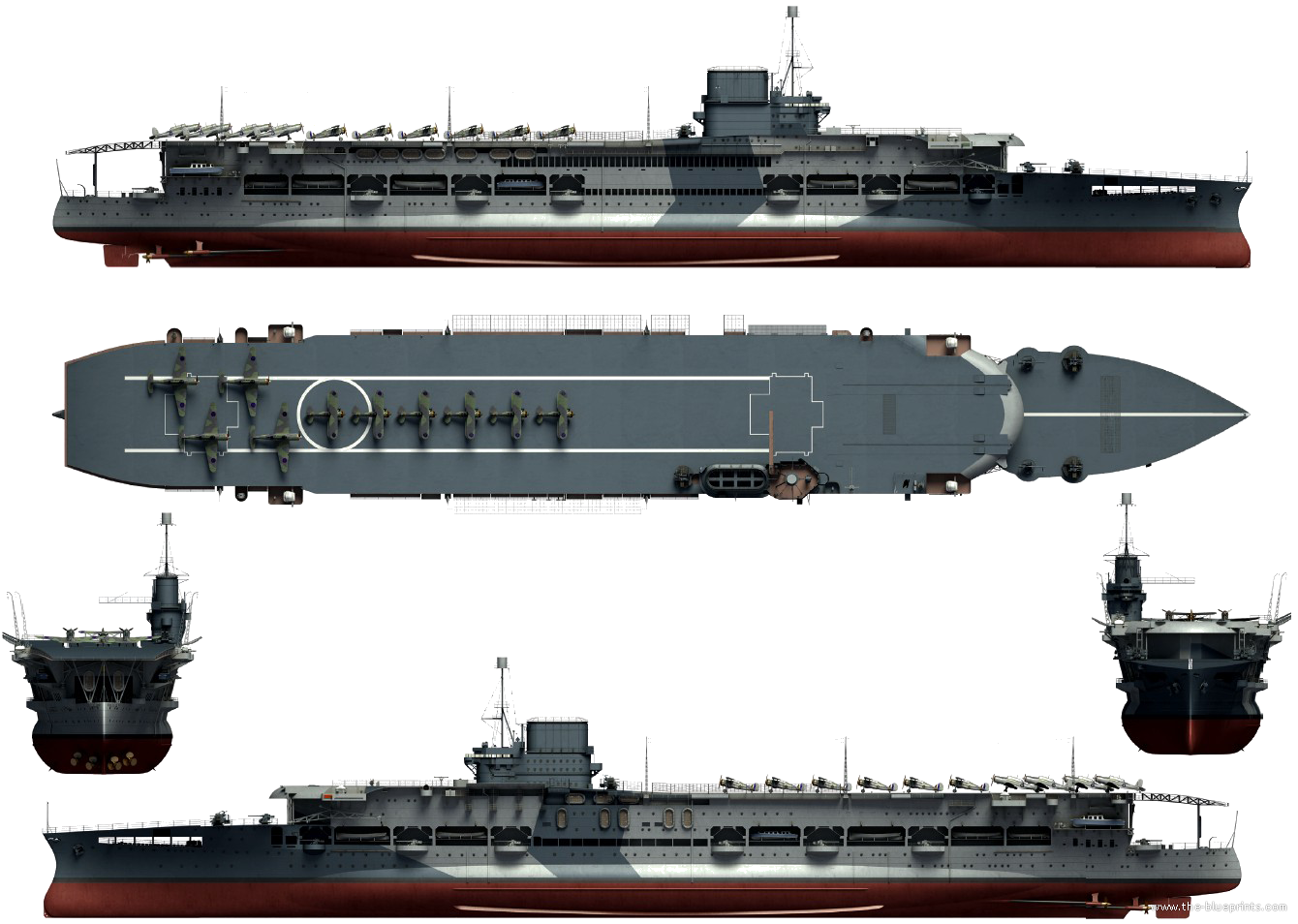

The blueprints – 1940 3D rendition, four views

Author’s illustration, HMS Glorious

HMS Courageous (1929) |

|

| Dimensions | 224.1 wl/239.8 oa x 26.8 x 8.3 m (735/786 x 88 x 27 ft) |

| Displacement | 24,210 long tons standard, 26,990 long tons FL |

| Crew | 841+403 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts geared steam turbines, 18 Yarrow boilers 90,000 shp (67,000 kW) |

| Speed | 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) |

| Armor | Belt: 2–3 in, Decks: 0.75–1 in, Bulkhead: 2–3 in, Torpedo bulkheads: 1–1.5 in |

| Armament | 16 × 4.7 in (120 mm) AA guns, see notes |

| Aviation | Variable over time: 48 1929, 30 1940 |

Interwar service of both carriers

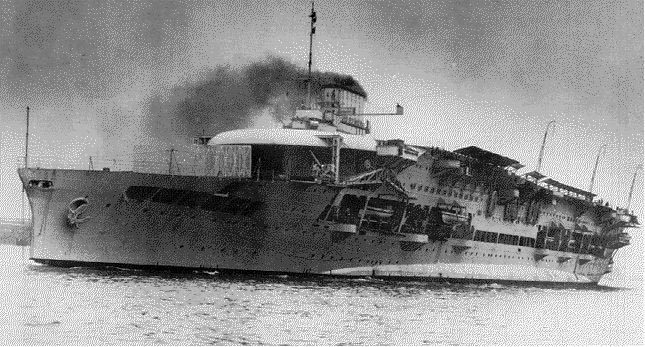

HMS Courageous was recommissioned on 21 February 1928. Her first assignment was the Mediterranean Fleet, from May 1928 to June 1930. She swapped her place for Glorious, back home for a refitting until August 1930. Next she was assigned to the Atlantic and Home Fleet, from 12 August 1930 to December 1938, with the exception of a temporary attachment to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1936 as the Spanish Civil war broke out, notably to patrol merchant traffic lanes. In 1932, a transverse arresting gear was installed. She received also received two hydraulic catapults on the upper flight deck around March 1934, with this step and bulbous take-off deck. In her October 1935-June 1936 refit, Courageous received pom-pom mounts. In 1937 she participated in Coronation Fleet Review and became a training carrier in December 1938 as HMS Ark Royal was now in service in the Home Fleet. She went on in this task until September 1939.

HMS Glorious was recommissioned after reconstruction on 24 February 1930, two years after her sister ship. She served with the Mediterranean Fleet, to join later the Home Fleet from March to June 1930 and relieved Courageous in the Mediterranean that month, remaining at this station until October 1939. Glorious had the misfortune of a collision in heavy fog, on 1 April 1931. She rammed SS Florida amidships at 16 knots. Though the speed was not considerable, the force of the impact crumpled 60 feets of the bow flying-off deck. Glorious was sent in drydock in Gibraltar for temporary repairs, then Malta for permanent repairs which took until September 1931. Like her sister in 1932-33 she received a transverse arresting gear. But her major refit was at Devonport in July 1934. It took until July 1935. There, she received two catapults and her flight deck was extended to the rear while her quarterdeck was raised one deck. She was also given multiple pom-pom mounts in octuple mounts unlike her sister. Like Courageous, she was present in the 1937 Coronation Fleet Review, and steamed for the Mediterranean where she was when the war broke out.

Both ships had a particularly short wartime career:

HMS Glorious in service

Glorious was in the Mediterranean Fleet when the Second World War broke out. In October, she transited through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean. There, she was assigned to Force J tasked to hunt for KMS Admiral Graf Spee in the Indian Ocean, without success. Afterwards, HMS Glorious remained in the Indian Ocean, until December 1939 and the end of Graf Spee. She then was ordered back to her post in the Mediterranean.

Norwegian Campaign

The Home Fleet needed her and she was ordered to move north in April 1940. The goal was to provide air cover for the landings in Norway. For this at that time, she deployed Eighteen RAF biplanes Gloster Gladiators (No. 263 Squadron) were flown aboard, that needed later to flew to their Norwegian airbase for later operations. She also carried eleven Blackburn Skuas of 803 Squadron, and 18 Sea Gladiators (the navalized version, mandatory in 1939-1940 as carrier fighter) from the 802 and 804 Squadrons. HMS Glorious was not alone, as she arrived with HMS Ark Royal. The task force joined their central Norway area of operations on 24 April. 263 Squadron was flown off as planned, and tthe Glorious air group started to attacked targets of opportunity around Trondheim. HMS Glorious’s own Sea Gladiators provided air cover for Ark Royal as well, and they claimed one Heinkel He 111 bomber. Then, the admiralty ordered Glorious to sail back to Scapa Flow on 27 April. She was to refuel (including aviation gasoline for operations) and embark new aircraft to be flown off in situ. Before departure, she transferred four Skuas to the Ark Royal and was in Scapa on 1 May. However the weather was appealing and she was unable to load new aircraft, just a dozen of Fairey Swordfish (823 Squadron), three Skuas and one Blackburn Roc. Brave pilots for all, as the wind was fierce and visibility poor, not counting the rocking and rolling of the carrier. Some attempted the landing and renounced for their own safety. Meanwhile the Luftwaffe kept attacking the task force, which was withdrawn in the evening. Sea Gladiators claimed a Junkers Ju 87 Stuka that day.

HMS Glorious was back off the Norwegian coast on 18 May, carrying six Supermarine Walrus flying boats (701 Squadron) and 18 Hawker Hurricanes (No. 46 Squadron RAF) to reinforce the Norwegian British air force in the area around Trondheim. To avoid problems with the weather, they were loaded aboard by crane. After the Sup. Walrus were flown off to Harstad, the British learned the Norwegian could not made the airfield at Skånland ready, and Glorious returned to Scapa with the Hurricanes on 21 May. She was back back to Narvik five days later, flowing off her Hurricanes.

Despite of these reinforcements, the Germans proved very efficient, and British forces were soon ordered to withdrawn days later. The evacuation was alled Operation Alphabet. It started north of the Narvik area during the night of 3/4 June. Glorious was already there on 2 June, providing air support with her nine Sea Gladiators (802 Sqn.). To possibly deal with the Kriegsmarine she also had six Swordfish (823 Sqn.). She was tasked to evacuate the RAF fighters if possible as well. Eventually during the afternoon of 7 June, ten Gladiators (263 Squadron) successfully landed on her deck and were stored in the hangar, followed by Hurricanes of 46 Squadron. This was a difficult task as the latter were not designed to operate on a carrier and landed with high speed on a net, the only way possible since they missed a tailhook and a 7 kg (15 lb) sandbag placed in the rear of the Hurricane to enable immediate full brakes on landing. This was a world’s first at that time…

The sinking, 8 june 1940

Captain Guy D’Oyly-Hughes, which also served as executive officer on HMS Courageous for nearly a year was granted permission to return alone to Scapa Flow. He set sail at noon on 8 June. There was indeed a case of a court-martial for the air Commander J. B. Heath. He allegedly refused an order to attack shore targets. He defended himself by stating these were ill-defined and his aircraft were not suited for the task. He was to be left Scapa to await trial and the carrier was to return and resume operations. This was a fateful decision, as on her way back home, she sailed withr two escorting destroyers, Acasta and Ardent, but her thick smoke was spotted by no others than the best German capital ships of the time, the fast and deadly German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. On their side, they were on their way for Operation Juno. They spotted the smoke at about 15:46 pm. The British spotted the German ships about 16:00 in turn. HMS Ardent was detached from the group to investigate the nature of the ships. By that time, the position of the German ships was unknown and Glorious’s captain decided nott alter course, or even increase speed. Soon, five Swordfish were scrambled, and Action Stations ordered ten minutes after spotting. However no aircraft was ready on deck for nor lookout in the crow’s nest when Scharnhorst opened fire at a range of 16,000 yards (15,000 m), at first on the approaching HMS Ardent. It was 16:27 when the first massive plumes appeared, framing the destroyer, which immediately withdrawn, after firing torpedoes and creating a smoke screen to cover her retreat. She was close enough at some point also to fire her 4.7-inch guns, and scored a hit on Scharnhorst. Both battleships was as fast a her, even faster as they were less disturbed by heavy seas. A duel started, and at that point, Scharnhorst used her secondary artillery to pummel the Destroyer, which was hit several times, disabled, and later sank at 17:25.

KMS Scharnhorst in between targeted HMS Glorious at 16:32 with her main artillery. Six minutes later, on her third salvo, at 26,000 yards (24,000 m), one of her 28 cm round hit the forward flight deck, detonating in the upper hangar. This caused an immediate fire, detroying also two Swordfish being just prepared for attack. In addition, this flight deck hole was placed in such a way it prevented any aircraft to take off. HMS Glorious was then cornered, constrained to use its old 4.7 in (120 mm), presenting a broadside of six guns, slightly better than a destroyer. Needless to say at that point she was also out-ranged.

Splinters from the hit also penetrated a boiler casing. Steam pressure dropped and speed fell. At 16:58 a second hit destroyed the homing beacon above the bridge. The captain and most of his officers were killed in the blast. However it could have been worst: HMS Ardent and Acasta’s smokescreens had prevented the Germans to be more effective and between 16:58-17:20 the wind protected the Glorious. Both battleships ceased fire. A short pause which allowed damage control teams to combat fire, with little hope.

When fire resumed ay 17:20, Glorious was soon hit in the centre engine room. This caused a massive speed loss while her rudder was jammed and she started a slow circle to port while also starting to list to starboard. Ten minutes later, both German ships were now 16,000 yards to Glorious and resumed her firing, and continued to fire, blasting the aircraft carrier to bits until 17:40.

Meanwhile, HMS, manoeuvring to try to maintain the smokescreen on Glorious, broke through the smoke to attack. She was close enough to Scharnhorst to fire two volleys of torpedoes, eight of them. One hit Scharnhorst at 17:34, abreast her rear turret. Acasta also had her guns blazing and socred a 4.7-inch guns hit on Scharnhorst but she was soon blasted by secondary guns. She sank at around 18:20. Ten minutes before, Glorious, immobilized and burning from stern to stem, severely flooded, eventually capsized and sank at 18:10. The position noted was 68°38′N 03°50′E, 68°38′N 03°50′E. She left only 43 survivors, not rescued by the Germans. This was the even sadder conclusion to this unequal battle.

Indeed, survivors estimated that about 900 men left Glorious before she sank. However, Scharnhorst was damaged and their captains were unaware of the presence or not of additional Allied ships nearby. They ordered a hasty retreat, leaving there the survivors. The Royal Navy never new of this, as no message was sent, either by Glorious or the two destroyers, and only later catch a German radio signal. Eventually, the Norwegian ship Borgund, on her way to the Faroe Islands was there two days later on 10 June, picking up survivors, 37 initially alive and two which later died of exhaustion. They were landed to Thorshavn. Svalbard II also on the same course picked up five more survivors before she was spotted by a German aircraft. one more was probably also saved by a German seaplane, bringing the total to 40, including those of Acasta and Ardent, for a total loss of 1,207 (Glorious) 160 (Acasta) and 152 (Ardent) so 1,519 men.

This was double blow, with the failure to locate the German battleships, and later to mount a rescue, and became an embarrassment for the Royal Navy. However the failure of broadcasting a sighting report from Glorious was questioned in the House of Commons later, and the enquiry established that the heavy cruiser Devonshire was just passing by 30–50 miles (48–80 km) of the fight with Vice-Admiral John Cunningham carrying orders to evacuate the Norwegian Royal Family, but he was maintaining radio silence and could not have intervene. In that case, he could have at least diverted attention of one of the two battleships, but the fight would have been unfair, although, less so. Survivors from Glorious testified that a sighting report was sent, and received by Devonshire, but suppressed by Cunningham, following his orders. Confusion when using Glorious’s wireless telegraph frequencies could also have contributed. Also there was no airborne patrols over the area, whereas there was maximum visibility, so the carrier had no idea the German ships were around. There was another debate in the House of commons on 28 January 1999.

A memorial was erected for the three ships in the church of St Peter Martindale, Cumbria, and a plaque Nicholas’s Church, HMS Drake, Devonport 2002. On 8 June 2010, another plaque was deposed at the Trondenes Historical Centre in Harstad, Norway, a memorial tree in the National Memorial Arboretum in Alrewas, Staffordshire and another in the Belvedere Gardens, Plymouth Hoe.

A model of HMS Glorious by model maker Norman A. Ough built for the Royal United Services Museum is now on display in the Fleet Air Arm Museum at RNAS Yeovilton

HMS Courageous in service

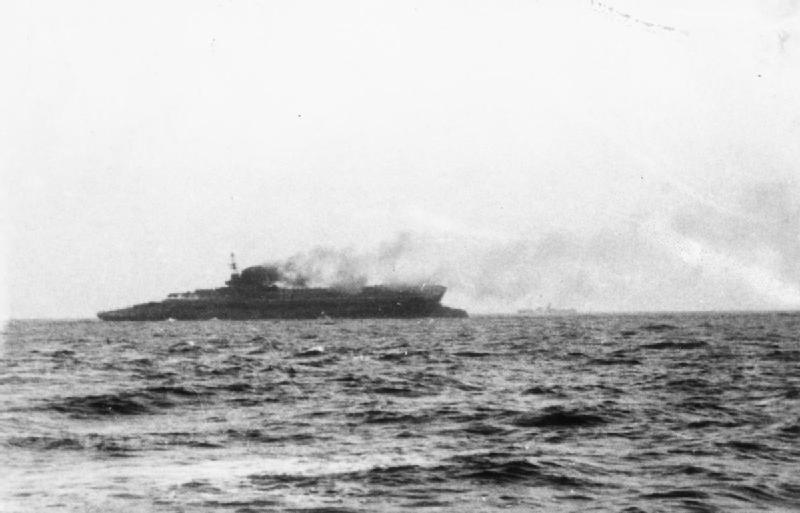

HMS Courageous started her wartime service with the Home Fleet, 811 and 822 Squadrons onboard (12 Fairey Swordfish). As ASW hunter-killer groups were formed around aircraft carriers on 31 August 1939, HMS Courageous was pressed in Portland and departed Plymouth on the evening of 3 September 1939 for her first ASW patrol on the soon infamous Western Approaches, with an escort of four destroyers. On 17 September 1939, her patrol carried her off the coast of Ireland with two destroyers away, sent to help an attacked merchant ship. Also, her planes were just back from their patrols; so there was no way of spotting an U-Boat in the surroundings, and that was exactly fateful: HMS Courageous was stalked for two hours by U-29 (Captain-Lieutenant Otto Schuhart). As the unfortunate aircraft carrier carrier turned into the wind to launch a Swordfish, she came across the U-Boat nose, and immediately three bow torpedoes went off. Two struck the carrier on her port side knocking out all electrical power. The gush of water -despite her ASW compartimentation- was so quick and massive that she capsized and sank in just twenty minutes carrying with her 519 of her crew including captain W.T. Makeig-Jones. 1202 Survivors were rescued by a passingby Dutch ocean liner, SS Veendam and a British freighter, the Collingworth. The escorting destroyers immediately counterattacked U-29 and hunter her down for four hours, but without success, as it evaded.

wow’s rendition of HMS Courageous

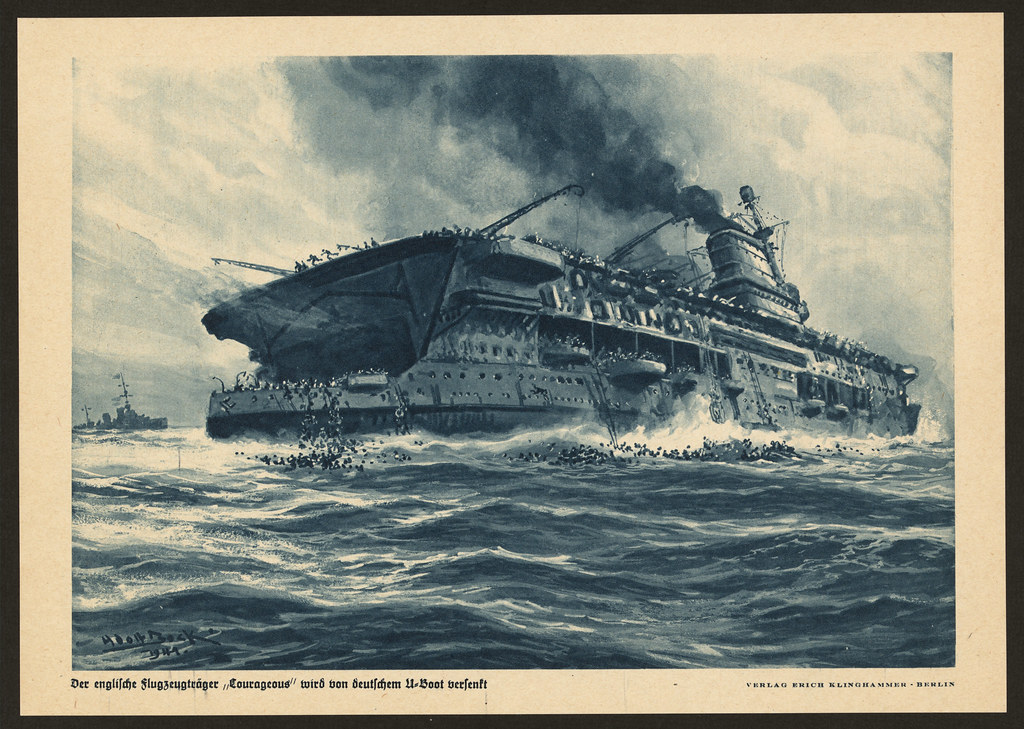

This tragic loss, combined to a similar U-Boat attack on Ark Royal (by U-39) on 14 September, prompted the Royal Navy to withdraw all its carriers from ASW patrols. Also incidentally, HMS Courageous was the very first British warship to be sunk during this war, not counting HMS Oxley, sunk by Friendly fire, not enemy action). Karl Dönitz, regarded this sinking as “a wonderful success” leading great hopes for his own weapon inside the Kriegsmarine. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder later awarded the Iron Cross, First Class, to Otto Schuhart and the rest of the crew received the Iron Cross Second Class.

Read More/Src

A German Verlag propaganda postcard showing the Courageous sinking

R. Gardiner, Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-1921 & 1922-47

Siegfried Breyer, Battleships and Battlecruisers 1905-1970 (Doubleday and Company; Garden City, New York, 1973)

John Roberts, Battlecruiser, (Chatham Publishing, London, 1997)

Roger Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present; An Illustrated Encyclopedia

Dan Van der Vat, The Atlantic Campaign: World War II’s Great Struggle at Sea

Correlli Barnett, Engage the Enemy More Closely (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1991)

John Winton, Carrier “Glorious”: The Life and Death of an Aircraft Carrier

Bruce Lee Marching Orders: The Untold Story of World War II (1995, Crown, New York)

John Roberts, Battlecruiser, (Chatham Publishing, London, 1997)

Winston Churchill, ww2 memoirs

David Wragg, Royal Navy Handbook 1939-1945

https://wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?384

https://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/courageous_class.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Courageous-class_battlecruiser

http://www.glarac.co.uk/

https://www.plymouthherald.co.uk/news/history/heartbreaking-story-royal-navy-heroes-2877036

http://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/pages/aircraft_carriers/hms_glorious_77.htm

https://janus.lib.cam.ac.uk/db/node.xsp?id=EAD%2FGBR%2F0014%2FGLOR

Archive (warships.org)

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?filters%5BagentString%5D%5BRoyal%20Navy%2C%20COURAGEOUS%20%28HMS%29%5D=on

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign