Japan, 1938-45: IJN Jun’yō, Hiyō

Japan, 1938-45: IJN Jun’yō, Hiyō WW2 IJN Aircraft Carriers:

Hōshō | Akagi | Kaga | Ryūjō | Sōryū | Hiryū | Shōkaku class | Zuihō class | Ryūhō | Hiyo class | Chitose class | Mizuho class* | Taihō | Shinano | Unryū class | Taiyo class | Kaiyo | Shinyo | Ibuki |The first IJN converted liners

Jun’yō (隼鷹, “Peregrine Falcon”) and Hiyō (飛鷹, “Flying Hawk”) were two Hiyō-class aircraft carriers of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). They were started before the war as the passenger liner Kashiwara Maru and Izumo Maru, respectively, but both were purchased by the IJN in 1941 while still under construction. They were both converted into aircraft carriers based on similar designs due to their common base.

Completed in May and July 1942, they participated in many Japanese Pacific offensives and campaigns, in the Aleutians, Guadalcanal, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and the Battle of the Philippine Sea (where Hiyō was sunk). Lacking both aircraft and pilots, Jun’yō by late 1944 was used as a transport, was torpedoed twice, and was under repairs until March 1945 when they were cancelled and she was BU after the war. Note that some authors who speak of the Jun’yō class classify them as “escort carriers”.

Conversion genesis: From Liners to Aircraft carriers

hese two vessels started existence as the fast luxury passenger liners Izumo Maru and Kashiwara Maru ordered by Nippon Yusen Kaisha, or the Japan Mail Steamship Company, in late 1938. At the time, multiple civilian ships were being put into a “shadow factory” scheme where they would be converted down the line, and thus the Nippon Yusen Kaisha made an agreement with the IJN: In exchange for funding 60% of the construction costs they had to be designed in order to facilitate a conversion to aircraft carriers later. This was not an ad hoc, desperate wartime measure but rather a planned requisition.

The conversion of liners was not new at the time: HMS Argus showed the way in 1918: She was the former Italian liner Conte Rosso built at Beardmore, was requisitioned during the war and converted into a carrier, commissioned in September 1918, shortly before the hostilities ceased. At the time this demonstrated to all navies the potential of such ships for such conversions. In WW2, Italy converted two former liners as fleet aircraft carriers, creating the Aquila class, though they were not fully completed. Other nations would also attempt similar conversions, with varying levels of success.

The basic design of the Izumo Maru class, therefore, was planned from the beginning with a set of features facilitating the later conversion process. Unlike common liners, they had a double hull, extra fuel oil capacity, and provisions to fit additional transverse and longitudinal bulkheads for protection. They also fitted extra bracing to support the deck and were given a longitudinal bulkhead separating the turbine rooms in case of flooding. Steel frames were provisioned also to support the future flight deck, and there was extra room between decks for a future hangar.

Also, a rearrangement of the superstructure and passenger accommodations was made in order to facilitate the future installation of aircraft elevators. There was also more space in between walls for future additional wiring. They were given a bulbous bow, known to increase speed but seldom used on civilian designs, alongside extra fuel tanks buried deep within for aviation gasoline storage, placed aft of the machinery spaces.

The only proper requirement of the Japan Mail Steamship Company was a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) in order to save fuel, but the Navy indicated they were only satisfied with no less than 25.5 knots (47.2 km/h; 29.3 mph) in order to ensure fleet operations. The compromise was to limit performance for the turbines installed, with a governor at 80% of maximum power for peacetime use.

Both ships were laid down in military shipyard in order to ensure this “military grade” readiness: SS Kashiwara Maru at Kawasaki Shipyard, Kobe on 30 November 1939, and SS Izumo Maru at Mitsubishi Shipyard, Nagasaki on 20 March 1939. She was the lead vessel but was launched two days after her sister ship, although converted and completed sooner. This way, given the usual conventions, the class is not called Junyo but Hiyo.

Purchase and conversions start

junyo on navsrource.org

Both were purchased on 10 February 1941, four months before launch, by the Navy Ministry at a final cost of ¥48,346,000. With extra costs coming from their newly added armament and provisions for aircraft equipment, plus telemeters and fire control systems, for a supplementary cost of ¥27,800,000 and global, for the two, of ¥38,073,000 and ¥114,219,000 including their first aviation park. SS Kashiwara Maru and Izumo Maru were renamed, and provisionally became No.1001 (Dai 1001 bankan) and No.1002 (Dai 1002 bankan) to keep work secret. The name Jun’yō (Peregrine Falcon) and Hiyō (Flying Hawk) were later chosen in accordance to the allegoric flying beasts naming convention for aircraft carriers at the time.

The admiralty however did not have them classified as fleet carriers due to their still insufficient speed but rather as auxiliary aircraft carriers (Tokusetsu kokubokan). However after the loss of four carriers at Midway (Kaga, Akagi, Hiryu; Soryu) in order to beef up the 1s Fleet air force and waiting for additional proper fleet carriers (notably the Unryu class), they were redesignated as regular carriers (Kokubokan) in July 1942, at about the time IJN Hiyō was completed.

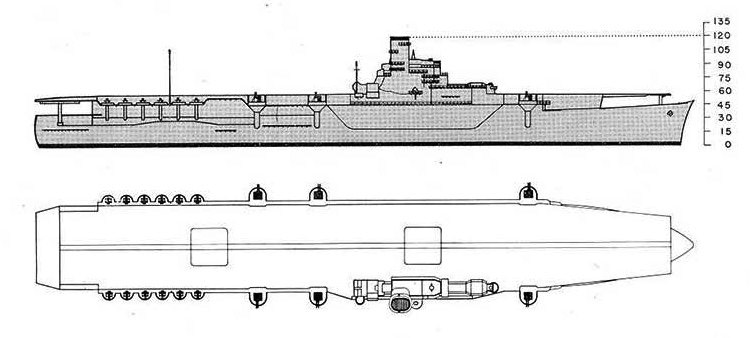

Design of the conversion

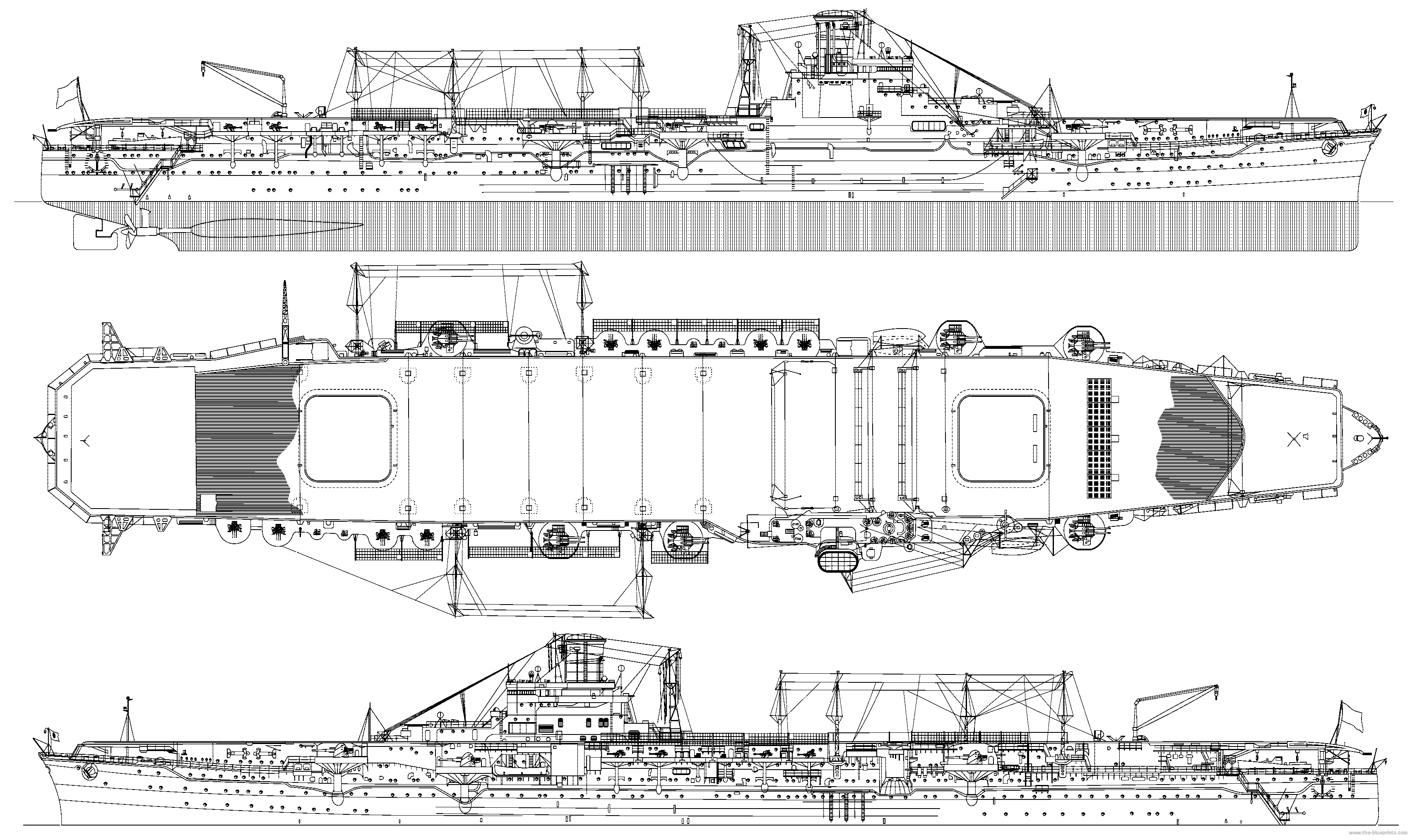

As completed, both vessels added a flight deck to the original hull and a large command island and funnel on the port side. The hull measured in the end 219.32 meters (719 ft 7 in) overall for an unchanged beam of 26.7 meters (87 ft 7 in) and 8.15 meters (26 ft 9 in) draft at normal load. Standard displacement was 24,150 metric tons (23,770 long tons) and the crew ranged from 1,187 to 1,224 officers and ratings.

Powerplant: Best range of any IJN carriers

junyo-left-side navsrource.org

Both liners had been fitted with two Mitsubishi-Curtis geared steam turbine sets. Together they produced a combined output of 56,250 shaft horsepower (41,950 kW). They drove 5.5-meter (18 ft) propellers at the end of the shafts. Steam came from six water-tube boilers which differed due to their separate building yards: Jun’yō had Mitsubishi three-drum models working at 40 kg/cm2 (3,923 kPa; 569 psi) pressure and 420 °C (788 °F). IJN Hiyō had Kawasaki-LaMont boilers (specs unknown).

Despite the fact that their machinery was designed for merchant service, it still was four times better than the military-grade and purpose-built IJN Hiryū !

The latter indeed managed 153,000 shp but on 17,300 long tons, and 34.3 knots (64 km/h; 40 mph). Her ratio and displacement were indeed completely different, she notably had a 7.84 m (30 ft)draft and only 22.32 m (73 ft) width.

The Hiyo class had a designed speed of 25.5 knots, and on trials, they managed to exceed them, but just. With 4,100 metric tons (4,000 long tons) of fuel oil onboard, their range reached 11,700 nautical miles (21,700 km; 13,500 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), which was quite honorable, in fact, far better than the Soryu, Hiryu, Zuikaku class, or Kaga-Akagi on that matter. These numbers were due to their amazing propulsion design, more impressive due to the economic nature of the engines, not tailored for speed.

Flight Deck and accommodations

-The flight deck as completed measured 210.3 meters (690 ft), thus slightly shorter than their overall length.

-Maximum width was 27.3 meters (89 ft 7 in), better than most fleet carriers of the time, thanks to their larger beam.

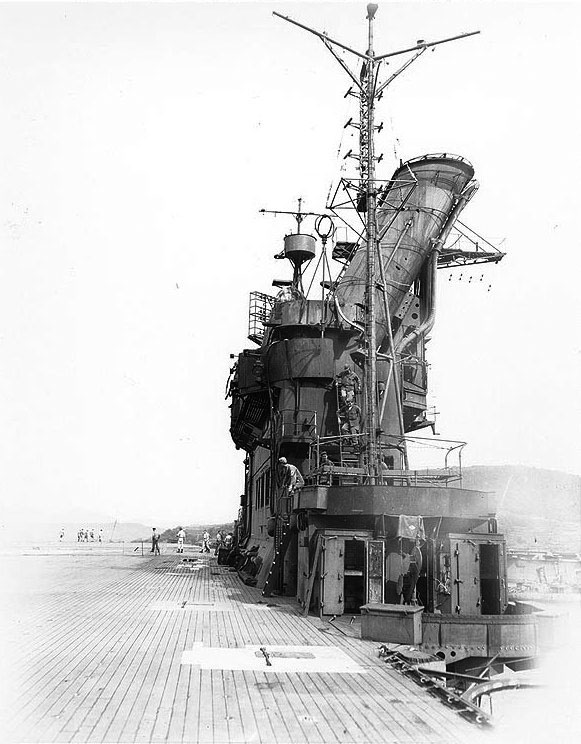

-The large island was positioned starboard and was overhanging from the side with a large, bulgy structure going down almost to the waterline.

-The engineers managed something new with the exhaust system as they had truncated it from all the ship’s boilers into a single funnel and not over the side of the hull, below flight deck level as usual.

This innovation, with the funnel 26° angled outwards, allowed a better smoke dispersal far from the deck and avoided “hot points” close to the flight deck. Models already were tested with this shape and smoke proving this was not interfering with flight operations. It became a feature of many future IJN carriers.

Their main feature was two superimposed hangars, like Ryujo and Ark Royal. Each was 153 meters (502 ft) long for 15 meters (49 ft 3 in) in width only, but 5 meters (16 ft 5 in). The difference in the width was explained by all the crew quarters and stores being installed on both sides of the hangar.

For fire safety, each hangar was subdivided into four sections which were split by fire curtains on rails. They could be deployed at a moment’s notice. These sections were also equipped with fire-fighting foam dispensers on either each side, but not sprinklers. The air group was managed in between these two levels and the deck, by two equal size square (with round corners) elevators 14.03 meters (46 ft 0 in) long and wide.

Maximum capacity was 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb), compatible with most IJN aircraft in service at the time. They reached the deck, from the lowest level, in just 15 seconds. The ships had no catapult just like other IJN carriers, and planes landed by catching one of the nine electrically operated Kure type model 4 arresting gears. Two main Type 3 crash barricades were also installed at the main island level. For downed planes, boat service, or seaplane operations, a crane was installed on the port side of the flight deck, next to the rear elevator, which could be collapsed flush with the flight deck if need be.

Protection

IJN Hiyo detailed plan, 1942

Being a civilian ship nevertheless, it was difficult to “load” the design with heavy armor, and notably due to their role, a more minimalistic approach was chosen, to protect vitals, and against aviation fire mostly: They had no belt but an armored deck 2″ thick (50 mm) plus an extra 0.8″ (20 mm) plating over of ducol steel over the machinery, and 1″ (25mm) box protection for their magazines and aviation fuel, also of made of ducol steel. This was insufficient to block a bomb penetrating the hangar but it could at least stop bomb fragments from penetrating the vitals. Against torpedoes, however, apart from the double hull and some compartmentation including the machinery spaces being subdivided by transverse and longitudinal bulkheads to limit flooding, no particular measures had been taken. Junyo would pay for it dearly in 1944. By March 1944 however, aircraft fuel tanks on the surviving Junyo had received additional concrete protection.

Armament

5-in DP guns

By its composition, both ships’ armament was a classic mix between the two standards of any IJN aircraft carrier of the time: Twin 5-in guns Type 89 dual purpose (DP) guns and triple 25 mm Type 96 AA mounts. The latter was augmented drastically until June 1944, mostly with single mounts.

Six twin Type 89 5-in (12.7 cm) DP

These 40-caliber 12.7 cm Type 89 anti-aircraft (AA) guns in twin mounts were located on six sponsons along the sides of the hull, supported by pillars. There were two forward at the same level, and because of the island, one opposite it, to port, another aft, just before the rear elevator, and two starboard after the island.

- 23.45-kilogram (51.7 lb) Frag shell

- 8 and 14 rounds per minute

- muzzle velocity of 700–725 m/s (2,300–2,380 ft/s)

- 45° max elevation

- range of 14,800 meters (16,200 yd)

- ceiling 9,400 meters (30,800 ft)

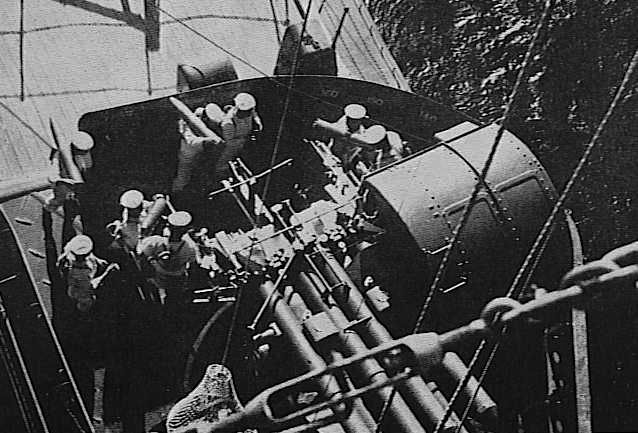

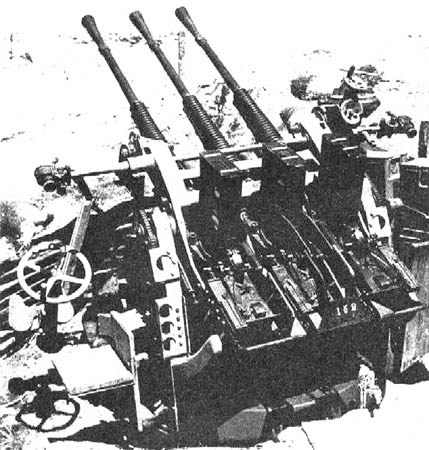

Eight triple Type 96 25 mm AA

They were also located on sponsons along the flight deck, four on the port side, opposite and aft of the island, and four starboard, behind the aft 5-in DP guns and at the level of the rear elevator.

- .25-kilogram (0.55 lb) shells

- muzzle velocity of 900 m/s (3,000 ft/s)

- maximum range of 7,500 meters (8,202 yd)

- effective ceiling of 5,500 meters (18,000 ft)/+85°

- rate of fire 110-120 rounds per minute

The issues with the guns were known: They had no suitable targeting system, vibrations, and reloading was labor intensive due to the frequent need to change the fifteen-round magazines. In 1943, four additional triple mounts of the 25mm/60 96-Shiki AA guns and two twin ones were added on both vessels. By March 1944, Junyo had seven extra triple 25mm/60 and 18 single 25mm/60 Type 96. In August 1944, twelve triple 25/60 96-Shiki, and six 28-tubes 120mm AA Rocket Launchers were also added.

Electronics

They were completed in May-August with no radar, but this was provisioned for in the design. During their late 1942 overhaul, both were fitted with the 1-Shiki 2-go early warning radar, mounted on their bridge’s roof. In 1943, they kept the 1-Shiki 2-go radar, but a second was added aft of the flight deck, at the level of the rear elevator and on the port side, opposite the island.

By August 1944 the surviving IJN Junyo was given a 3-Shiki 1-go radar, replacing the one fitted on the bridge’s roof.

Other features

In addition to a main telemeter for their main artillery installed on the bridge and another installed on a structure forward of the island, they had extra side safety nets, mostly installed alongside the aft part of their flight deck, starting at the island port and starboard, and ending at the level of the aft lift. They were mounted on elevating frames, two to port and three to starboard. For communications, they had a main tripod mast aft of the island, behind the funnel, a main radio mast just aft the funnel, and two derrick antennae for long-range communication on the side of the flight deck, on both the port and starboard side on sponsons.

The flight deck landing lip was beveled and painted in the standard red and white band pattern. On both sides were installed sets of lights to help the pilot figure out his position and balance his landing approach. Another marking this time with direction indicators (painted white) was set in between the crashing barriers at the island level for the long launching spot and at the end of the flight deck, which was clad in metal plating while the rest of the ship, to the exception of the landing area, was wooden-sheathed. Space aboard was limited. Two “vals”, wingtip to wingtip, covered the entire beam, making parking difficult.

The ships also carried several service boats: Two diesel-powered cutters aft, under the landing deck in an open space and able to be reached by the aft cranes. The ship also carried a small yawl under davits under the side deck close to the island, and another on the port side, opposite the island, but the rest of the ship’s complement comprised inflatable rafts installed wherever possible. The ships carried four paravanes for mine cutting, stored close to the bow where they were fitted, on either wall of the forward hangar section. Two static anchorages with extra anchors were located close to the bow. There were side ladders to mount/dismount small boats on the starboard. For stability, they were both fitted with anti-rolling bars underwater.

Air Group

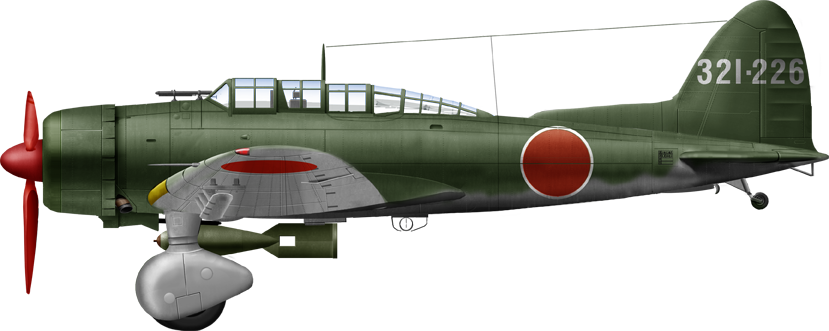

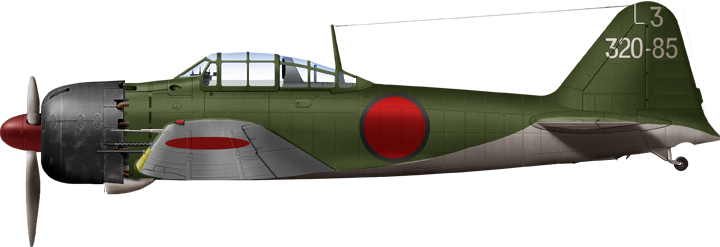

Technically, these vessels could carry 54 aircraft, which was honorable but was less than the Zuikaku class, which carried 72, or the Hiryu and Soryu which carried 64 and nine spares, despite their smaller size. This was expected however due to the limited width of the hangars. When completed in the summer of 1942 they were given the “classic trio” of the time: A56M “Zero” fighters, D3A1 diving bombers, and B5N torpedo bombers (“Zeke”, “Val” and “Kate” in allied code). The exact composition varied over time and ship.

As completed, Junyo had 16 A6M2 “Zeke” fighters (which replaced the planned 12 A5M plus four in storage) and 18, later 24 D3A (40) plus either spare and nine “Kates”, which were nine in July, for 21 “Zeke” so 48 total, plus probable spares.

Hiyo had 21 “Zeke”, 18 D3As, and 9 B5Ns when completed in August, but in early 1943, she carried 27 fighters and 12 torpedo bombers only.

In November 1943, Junyo received its first 12 A6M5, in compliment to her 12 A6M2s. The rest of her air group comprised nine D3A2 “Val” completed by nine D4Y “Judy” and nine B5N making 51 aircraft.

IJN Hiyo retained her A6M2s into late 1943, but in June, at the battle of the Philippines, she had nine of them plus eighteen A6M5, in complement of eighteen D3A2 “Val” and nine B6N. She never operated the D4Y contrary to her sister.

From June 1944 until she was torpedoed and sent back for repairs, she had nine A5M2, 18 A5M5 fighters, nine D3A2 “Val” and nine D4Y Suisei “Judy” and nine B6N Tenzan “Jill”, both being for more capable than their predecessors. Her air group was sent to other carriers when she was sent back for repairs and never returned.

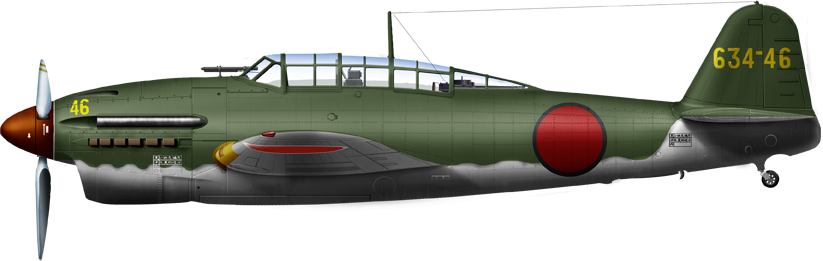

Aichi D3A2 “Val”, 65th Kokutai aboard IJN Jun’yo, June 1944.

Yokosuka D4Y “Judy”, 634th Kokutai IJN Jun’yo, August 1944

Mitsubishi A6M5b “Zeke”, 652th Kokutai, IJN Jun’yo, June 1944

Author’s illustration of IJN Junyo in 1944, battle of the Philippines

⚙ Specs 1942 |

|

| Dimensions | 219.32 x 26.7 x 8.15 (719 ft 7in x 87 ft 7in x 26 ft 9in) |

| Displacement | 21,150 t. standard -28,000 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 2 GS turbines, 8 Kampon wt boilers, 56,250 hp. |

| Speed | 25.5 knots (47.2 km/h; 29.3 mph) |

| Range | 11,700 nmi (21,700 km; 13,500 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | Belt 25-50mm (0.98-1.97 in) |

| Armament | 6×2 127 AA (5 in), 8×3 25 mm AA, 54 aircraft |

| Electronics | Type 13, Type 21 early-warning radar |

| Crew | 1,187-1,224 |

Sources/ Read more

Books

Sturton, Ian, J. Gardiner’s, R. Chesneau Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-1947

Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Naval Institute Press (NIP).

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. NIP

Hata, Ikuhiko; Yasuho Izawa (1989) [1975]. Japanese Naval Aces and Fighter Units in World War II. NIP

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. NIP

Lengerer, Hans & Rehm-Takahara, Tomoko (1985). “The Japanese Aircraft Carriers Junyo and Hiyo”. Lambert, Andrew’s (ed.). Warship IX. Conway

Lundstrom, John B. (2005). The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign. Annapolis, Maryland: NIP

Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. NIP

Stille, Mark (2005). Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945. New Vanguard. Osprey Publishing.

Tully, Anthony P. (2006). “IJN Hiyo: Tabular Record of Movement”. Combinedfleet.com. 2011.

Tully, Anthony P. (1999). “IJN Junyo: Tabular Record of Movement”. Combinedfleet.com. 2011.

Links

ONI schematics of Junyo

On globalsecurity.org

On navypedia.org

Warships Intl. DATA ON JAPANESE AIRCRAFT CARRIERS (PART TWO) Donald L. Kindell (JSTOR)

On historyofwar.org

combinedfleet.com additional photos

On ww2db.com

Hiyo on combinedfleet.com

Wiki

On pwencycl.kgbudge.com

The model’s corner

Tamiya’s WL series 1:700 Junyo

The class kits on scalemates

IJN Hiyo

IJN Hiyo

Hiyo was commissioned on 31 July 1942, under Captain Akitomo Beppu, assigned to the Second Carrier Division, 1st Air Fleet after the losses sustained at Midway, as the flagship of Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta from 12 August. After some training, she arrived at Truk to join Jun’yō on 9 October for Guadalcanal operations with the 3rd Fleet.

On the night of 16 October, they launched their air groups against American transports off Lunga Point, from 180 nautical miles north of Lunga. At 05:15 the 12A6M Zeros and 18 B5Ns reached their objective and surprised two USN destroyers shelling IJA supply dumps, beginning their attack at 07:20. USS Aaron Ward was targeted without effect, while a B5N was shot down, with another making a crash landing. Jun’yō’s eight B5Ns attacked USS Lardner and were hunted down by USMC Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters at 07:32, which shot down three of the slow torpedo bombers, along with forcing two to crash land due to damage alongside shooting down 3 D3As. In return, the escorting Zeros shot down one F4F though they claimed 13.

Her generator room however caught on fire on 21 October and she was reduced to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph), RADM Kakuta making IJN Jun’yō his flagship while Hiyo returned to Truk for repairs. As she did, she transferred to her sister 3 Zeros, 1 D3A, and 5 B5Ns to compensate for their previous losses. The remainder of her airwing flew back to Rabaul and later to New Britain’s airfield on 23 October, attacking Guadalcanal on the 24. They also attacked Buin, New Guinea, on 1 November and attacked American ships off Lunga Point on 11 November. Escorted by 18 Zeros from IJN Hiyō and 204th Naval Air Group her nine D3As slightly damaged three cargo ships, losing 4 of their number, plus another which was forced to crash land. In return, the escorting Zeros shot down four out of six Wildcats, losing two of their number.

IJN Hiyō left Truk in early December and was rejoined by her air group on the way to Kure, where she was refitted on 26 February-4 March 1943, having additional AA as well as additional radar placed on her. After training in the Inland Sea, she returned to Truk on 22 March, shortly detaching her air group for Operation I-Go on the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. On 7 April her air group formed the third wave at Guadalcanal, escorted by 24 Zeros and 6 from Zuihō. They rampaged the Sealark Channel and claimed three US aircraft for one Zero, and three “vals”. Eventually, USS Aaron Ward was sunk as was the oil tanker Kanawha, minesweeper HMNZS Moa and the group damaged other ships in the area.

She took part in the attacks on Oro Bay, New Guinea on 11 April, with 9 Zeros escorting D3As, losing a single Val. A day later, 17 of her Zeros covered three waves on Port Moresby, with nine victories claimed for no loss. On 14 April, Milne Bay was attacked, also in New Guinea with a grand total of 75 Zeros. During the attack, Zeros from the Hiyō claimed three kills for no loss while her D3As claimed two transports. They were back in Truk on 18 April.

With Attu island under threat in early May, the IJN sent the Second Carrier Division from Truk, three battleships, and two heavy cruisers, via Japan on 25 May to reinforce it. However, Attu fell before they even departed. Rear Admiral Munetaka Sakamaki ordered Hiyō to depart for Yokosuka on 7 June, to join Junyō and depart for Truk but the latter was torpedoed by the Gato-class submersible USS Trigger off Miyakejima. She had her starboard bow and boiler room off but was able to return to Japan while her fighters went on to Truk, arriving on 15 July, and were reassigned to IJN Ryūhō along with RADM Sakamaki and staff.

Repairs in Yokosuka went on until 15 September and Captain Tamotsu Furukawa took command on 1 September, after which she trained for two months until her air group was reconstituted in Singapore: 24 Zeros, 18 D3As, 9 B5Ns. She was then assigned as an aircraft ferry from then on. On 9 December she departed for Truk, making a fast delivery run on 22 December. Next, she landed more aircraft in Saipan, which were dismounted and stored in the hangars. Her air group was sent meanwhile to Kavieng and Rabaul, claiming 80 victories for 12 losses.

Back in Japan on 1 January 1944, she was overhauled. Captain Toshiyuki Yokoi took command on 15 February and she was reunited with her air group on 2 March. At the time, the carrier force was being restructured, with a single air group assigned to an entire carrier division due to the lack of pilots. Thus the 652nd Naval Air Group was assigned to the Second Carrier Division (Hiyō, Jun’yō, Ryūhō), last to be rebuilt with 30 A6M3 and 13 A6M5 Zeros, four D3As, and eventually a total of 81 fighters, 36 dive bombers, and 27 torpedo bombers. After training in the Inland Sea, until 11 May, she headed for Tawi-Tawi, Philippines, closer to the oil wells in Borneo and to defend Palau and the western Carolines.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

The fleet en route to Guimaras Island (central Philippines) started carrier operation practice on 13 June 1944 when Vice-Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa received news of the US attack on the Mariana Islands, and after refueling the fleet was at sea again. Spotting Task Force 58 (18 June) Ozawa launched his air strikes, including aircraft from the 652nd Naval Air Group (81 Zeros, 27 D3As, 9 Yokosuka D4Y “Judy”, 18 Nakajima B6N “Jill” torpedo bombers) from his three carriers, the first wave being in flight at 09:30. Misdirected, they failed to find the Americans although one squadron eventually found an American task group. Despite this lucky finding, most of the planes were lost to the CAP for no damage inflicted.

The second air strike started at 11:00, in the company of extra planes from Shōkaku and Zuikaku. Also misdirected, they inflicted no damage and were forced to land at Rota and Guam to refuel, the remainder trying to find their way back to the carriers. Instead, some found USS Wasp and Bunker Hill and lost five D4Ys to AA, which at this point was directed by Radar. The other force from Guam was mauled down by 41 Grumman F6F Hellcats in an interception. A single fighter and 8 dive bombers made it back with 49 other aircraft.

Turning north-west to regroup and refuel at a distance, the US Task Forces eventually found the Japanese fleet retiring, prompting VADM Marc Mitscher to order an air strike. IJN Hiyō was soon spotted, targeted, and hit by two bombs, one crashing on the bridge, decapitated command, and a torpedo by a Grumman TBF Avenger from USS Belleau Wood which hit her starboard engine room. Fires started but were quickly brought under control and IJN Hiyō was able to go on at a slow speed. However, two hours later, unchecked gasoline vapors from the earlier hits caused a very powerful explosion, knocking out all power, and creating uncontrolled fires destroying the ship, before she was evacuated and sank, stern first. Fortunately, 1,200 men were rescued by her escorting destroyers, while 247 went with her to the bottom.

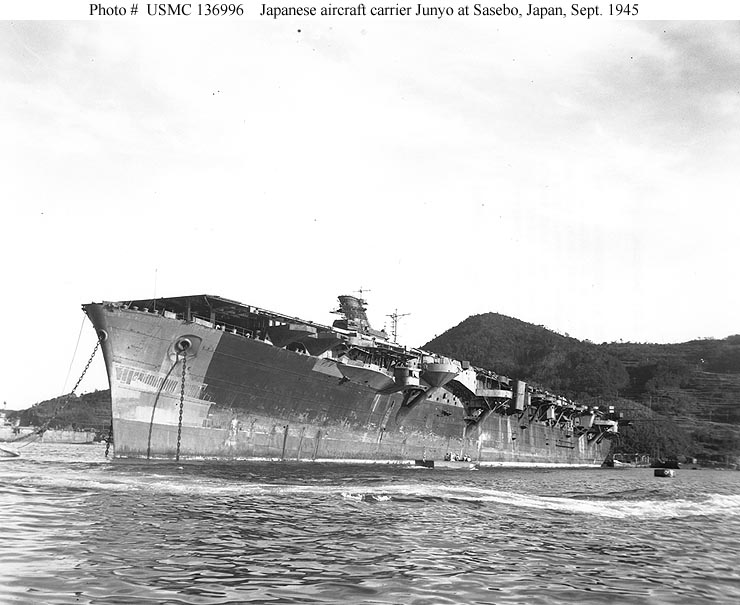

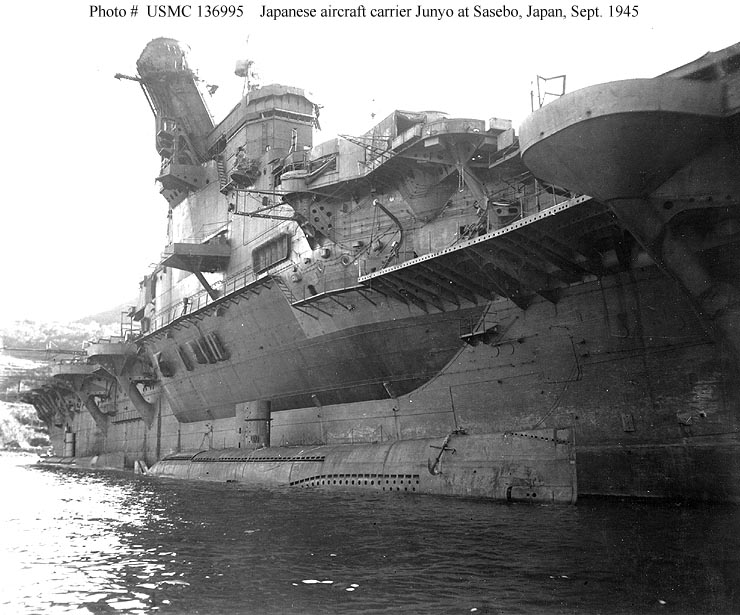

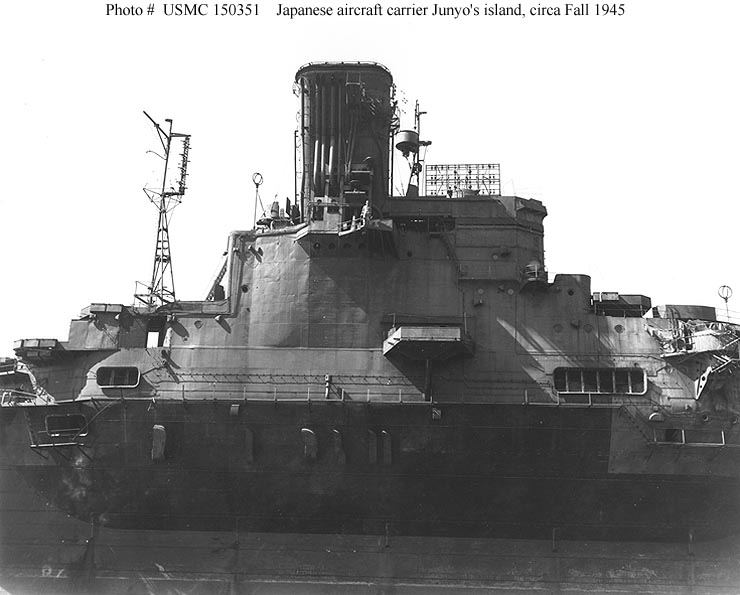

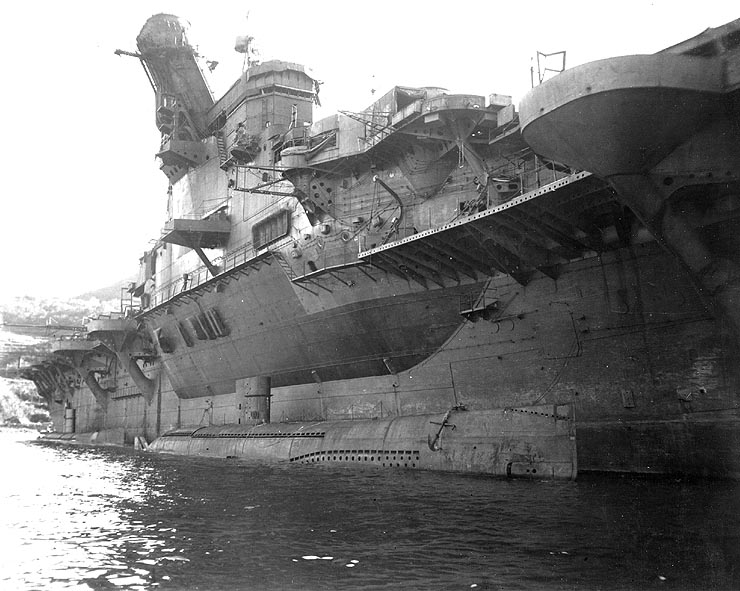

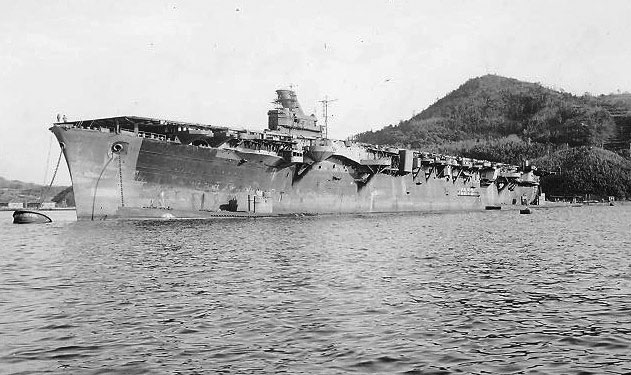

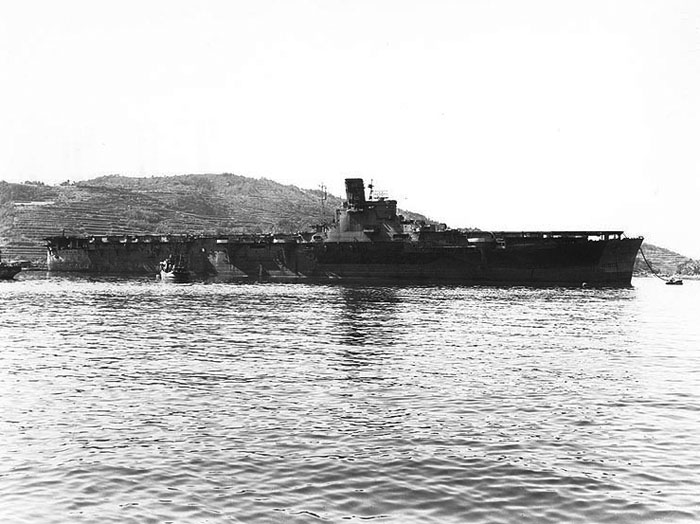

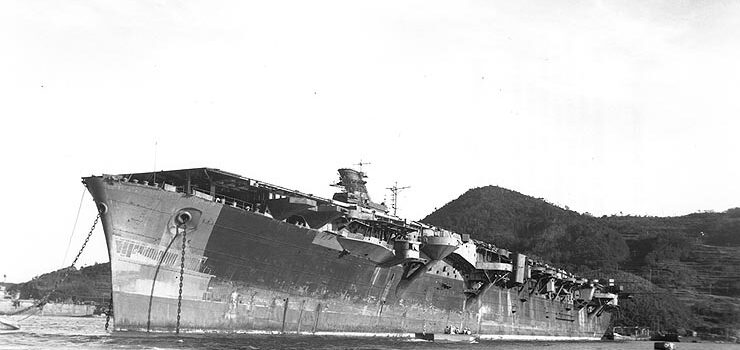

Junyo in Sasebo, 26 Sept. 1945

IJN Jun’yō

IJN Jun’yō

Aft flight deck view

Jun’yō was commissioned on 3 May 1942 and assigned to the Fourth Carrier Division, 1st Air Fleet with Ryūjō under Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta. She was assigned to Operation AL, an attack planned on the Aleutian Islands as a staging point before a later attack on the Kurile Islands, just as Midway was under siege. On 3 June, she launched 9 Zeros and 12 D3As to attack Dutch Harbor (Unalaska Island) but further operations were cancelled due to bad weather, with her Zeros claiming a single PBY Catalina on their return flight. A second airstrike was launched on US destroyers which had been spotted by aviation, but they were never found again.

Another airstrike totaling 15 Zeros, 11 D3As, and 6 B5Ns bombed Dutch Harbor but they were intercepted by 8 Curtiss P-40 fighters, claiming 2 Zeros, and 3 D3As while losing 2 of their own. There was also a US air attack on Junyo, but which failed to do any damage. A Martin B-26 Marauder and another PBY were shot down by the CAP, and a Boeing B-17 by the Japanese AA. Due to the results of Midway, Junyo was redesignated a Kokubokan, now under Captain Okada Tametsugu’s command from July. She was in Truk on 9 October with her sister Hiyō in the Second Carrier Division, intended for Guadalcanal operations with the 3rd Fleet.

On the night of 16 October, the two carriers were ordered to attack the American transports off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal and they moved south to their launching point 180 miles (290 km) north of Lunga. At 05:15 each ship launched nine each A6M Zeros and B5Ns (one of Jun’yō’s B5Ns was forced to turn back with mechanical problems) which reached the target and discovered two destroyers bombarding Japanese supply dumps on Guadalcanal around 07:20.

IJN Hiyō’s aircraft tried to sink USS Aaron Ward, but the latter still shot down one of her attacking B5Ns and damaged another (which was forced to later ditch). Jun’yō’s eight B5Ns attacked USS Lardner but were decimated by F4F Wildcats, losing three B5Ns, with two more crash landing for one claimed Wildcat, but one Zero lost. Later, due to a fire, Hiyō was reduced to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) and transferred three Zeros, one D3A, and five B5Ns to her sister ship while RADM Kakuji Kakuta transferred his flag aboard Jun’yō for the 2nd division.

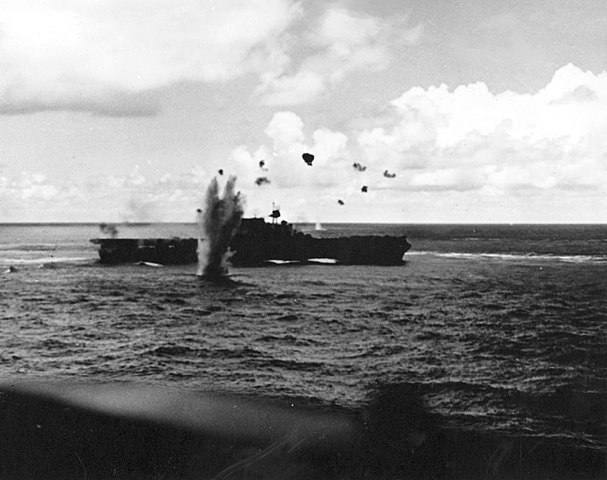

Japanese bomb explodes near USS Enterprise, Battle of Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942

In late October 1942, Jun’yō was at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands: She had 18 Zeros, 18 D3As, and 9 B5Ns and at 05:00 on the 26th, launched 14 Zeros and 6 few D3As to Henderson Field, which had been falsely reported by the IJA to be in Japanese hands: They tried to land and were greeted on arrival by AA fire and taking off F4F Wildcats, leading all to be shot down. At 09:30, Jun’yō launched another air strike which found and attacked USS Enterprise as well as the battleship USS South Dakota and the light cruiser USS San Juan. Only the latter two were hit, but with little damage.

A B5N passed in front of USS northampton at Santa Cruz.

She lost three “Vals” and a single “Kate” when met by Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, the latter showing to be capable fighters without their bombs and low on gasoline. RADM Kakuta then ordered a third air strike at 14:15, with six remaining B5Ns just received from the damaged IJN Shōkaku, plus nine “Vals” from both carriers. Six B5Ns and six D3As escorted by six Zeros fell on USS Hornet, which had been badly damaged earlier, and one torpedo hit from a Shōkaku’s “Kate” increased her list, adding to more seams created by near-misses and forcing her to be abandoned before she was finished off by two dive bombers hits.

By mid-November 1942, Jun’yō escorted a convoy to Guadalcanal which led to the first 3-day-long Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. At that point, she was operating 27 A6M3 Zeros, 12 D3A2s, and 9 B5N2s and had six Zeros of her Combat Air Patrol (CAP) in the air when SBDs from USS Enterprise arrived, which was followed by an air strike from Henderson Field which sunk seven transports, the remaining four badly damaged. USS Enterprise was eventually spotted, leading Jun’yō to launch an air strike, but they failed to locate the carrier.

December 1942-January 1943 saw her covering more convoys to Wewak, New Guinea and she stayed in Truk on 20 January, before covering the evacuation from Guadalcanal in February. That month she was overhauled in Japan and returned to Truk on 22 March, this time with her sister IJN Hiyō. (The latter’s air group was left at Rabaul (2 April) as she sailed to participate in Operation I-Go in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea.)

Jun’yō’s air group claimed 16 American aircraft and the destroyer USS Aaron Ward for 7 A6Ms and 2 D3As. Her air group was then sent to Buin in Papua New Guinea on 2 July, to operate on Rendova Island (30 June), claiming 37 US planes shot down for 9 of her own. The group was disbanded on 1 September and she was back in Japan by late July, ferrying aircraft to Sumatra (mid-August), along with troops and supplies to the Carolines (September-October 1943).

On 5 November 1943 while underway to Truk she was ambushed off Bungo Suidō by USS Halibut. One of the four torpedoes launched hit her aft, killing four of her crew. However, the overall damage was light, and she was only hindered by a damaged rudder. She was repaired and refitted until 29 February 1944 in Kure while her air group was reconstituted in Singapore. She went there to recuperate 24 Zeros, 18 D3As, and 9 B5Ns, before being transferred to Truk and Kavieng in December, and then to Rabaul (25 January 1944). From there, her Zeros claimed 40 Allied aircraft, 30 probable kills, traded for most of the air group being shot down, and rare survivors left on Truk on 20 February, the units disbanded.

With restructured air groups assigned to carrier divisions and no longer a sole aircraft carrier, she shared with her sister ship Hiyō and the CVL Ryūhō the 652nd Naval Air Group (2nd Carrier Division) from 1st March. In all, it comprised in common 30 Model 21 Zeros, 13 Model 52 Zeros (A6M2 and 5), four D3A2 “Val” from 1st April, a meager portion of the planned 81 fighters, 36 dive bombers, and 27 torpedo bombers. She trained in the Inland Sea with her new air group until 11 May and sailed for Tawi-Tawi, Philippines on a new base closer to the oilfields of Borneo.

Junyo, Aft view

They were moved to defend against an expected attack on Palau and the western Carolines but ran into trouble with no land-based airfields to train out of and the seas being infested with US submarines. However, the whole situation was resolved at the cataclysmic Battle of the Philippine Sea:

While underway to the Guimares Island, central Philippines, on 13 June, for carrier operations, VADM Jisaburō Ozawa learned about an attack on the Mariana Islands and CarDiv 2 sortied in the Philippine Sea, spotting TF 58 on 18 June, and turning south to maintain distance while launching air strikes. The 652nd Naval Air Group was now made of 81 Zeros, 27 D3As, 9 Yokosuka D4Y “Judy”, and 18 Nakajima B6N “Jill” dive and torpedo bombers divided among the three ships.

The first air strike comprised 26 A6M2 Zeros (loaded with bombs), 16 A6M5 Zeros in escort, and 7 B6Ns, taking off at 09:30, but was misdirected. Still, 12 kept searching and eventually found TF 38 but a B6N and five A6M2s were shot down by their CAP. The second air strike (27 Vals, 9 Judys, 2 Jills, and 26 Zeros) took off at 11:00 with 18 A6Ms/B6Ns from Shōkaku and Zuikaku and was also misdirected, finding nothing. They later reached Rota and Guam to refuel. Underway, some spotted the Essex-class USS Wasp and Bunker Hill but when attacking, were wiped out by AA. The rest were also annihilated by radar-guided 41 F6F Hellcats. In all, 49 survived the onslaught, including a single A6M5, one D4Y, and seven D3As from CarDiv 2.

Veering northwest to regroup and refuel they were eventually caught by US air strikes and targeted. IJN Jun’yō was soon straddled by several near-misses from dive bombers and eventually hit by two bombs near her island. Flight operations were suspended while the small 652nd Naval Air Group’s CAP claimed 7 attackers, 4 probable, but at the cost of 11 Zeros, with 3 more ditching. What was left of their air group was disbanded on 10 July and the remaining personnel was reassigned to Air Group 653. This was the end of carrier operations in CarDiv 2.

Emerging from Kure, IJN Junyō stayed in the Inland Sea, training without aircraft, until 27 October when she was reassigned to transport men and materiel to Borneo. On 3 November, she was ambushed by USS Pintado near Makung, but she was saved by the prompt decision of the captain of IJN Akikaze, her escorting destroyer which deliberately intercepted the running torpedoes. She sank with no survivors. Later, Jun’yō was ambushed again by USS Barb and Jallao, both sub’s torpedo’s missed.

On 25 November, while underway to Manila via Makung to meet IJN Haruna and the destroyers Suzutsuki, Fuyutsuki, and Maki, she carried 200 survivors from IJN Musashi and was attacked by USS Sea Devil, Plaice and Redfish on 9 December 1944, at the first hours. Three torpedoes hit her belt, flooding several compartments, and killing 19 men. She then took a 10°–12° list to starboard, still having enough engine power to reach Sasebo for repairs.

Junyo moored at Sasebo, autumn 1945

However, repairs were abandoned after little work had been done in March 1945. This was due to a lack of materials and men and she was moved to Ebisu Bay on 1st April and camouflaged from 23 April, now a “guard ship” from 20 June. Her armament was stripped off on 5 August. The Allies eventually arrived after the ceasefire on 2 September and she surrendered. A technical team evaluated her condition on 8 October and estimated her a “constructive total loss” Thus, she was stricken on 30 November, scrapped on 1 June 1946-1 August 1947.

Same, 19 October 1945

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign