Nazi Germany, 1,170 planned, 118 completed (1944)

Nazi Germany, 1,170 planned, 118 completed (1944)WW2 U-Boats:

Seeteufel (1944) | Type Ia U-Boats (1936) | Type II U-Boats (1935) | Type IX U-Boats (1936) | Type VII (generic) | VIIA | VIIB | VIIC | VIIC/41 | VIIC/42 | VIID | VIIF | Type XB U-Boats (1941) | Type XIV U-Boats (1941) | Type XVII U-Boats (1944) | Type XXI U-Boats (1944) | Type XXIII U-Boats (1944) | German mini-subs and human torpedoesThe Elektroboot saga: Too late to win

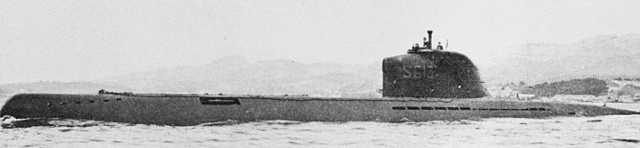

The Type XXI were large scale production Kriegsmarine’s “wunderwaffe” planned by Nazi Germany at the end of the war. Alongside the smaller Type XXIII “Elektobote” and numerous “midgets” at a stage events verged on desperation, it was supposed to reverse their course. Announced as the boldest leap into the future for the Kriegsmarine so far, the world’s most advanced submarine design of their time, The Type XXI would be also a powerful inspiration for all navies in the next decades, and up to the 1957 USS Nautilus. But was it a real game changer in 1945, or just an overblown propaganda effort ? Here’s the detailed answer.

A technological revolution: From submersible to submarine

With the Type XXI, for the first time, Germany made a decisive step from a “submersible” to a “submarine”: The philosophy that prevailed since 1905 was that a “submersible” was essentially a torpedo boat that submerge at times, for all emergency. Such vessel cruise at the surface most of the time, running on sober diesel engines, and went underwater on electric power generally to escape an attack.

Due to the limitations of electrical power at the time and having no accurate system to detect targets from underwater, a submersible was essentially slowed to a crawl, deaf and blind, limited in diving to its own length deep. Renewing the air or expelling surplus acid gases generated by the use of batteries caused “broths” detected for miles around the surface by planes on patrol, while the slightest noise on board betrayed their presence to more and more sophisticated hydrophones, not to mention their radar signature when surfaced.

This base principle stayed the same for all submersible models built by all nations from WWI to WW2. The so-called (improperly) “battle of the Atlantic” was led by U-Boats, essentially the same models as the WWI mass-produced (92 on 129 planned) Type UB III, notable ancestors of the WW2 Type VII (1936), a single, simple mid-range model, mass-produced until 1945. Although the latter was improved in many ways, limitations were still present.

The conclusion of all reports for losses to the allies were plural in origin: More escorts, more ships to sink (Libery/Victory), better tactics, better detection system, better armament, constant naval aviation patrol, and unbeknownst to the German naval staff, full knowledge of impending attacks thanks to the breaking of the Enigma machine by the Turing computer at Bletchley Park.

The 1943-44 “Wunderwaffen” craze

This traduced from mid-1943 onwards, to a growing, and soon unsustainable number of losses. It reached such a point in early 1944 that Grand Admiral Dönitz, now at the head of the Kriegsmarine since January, considered the battle as nearly lost. There were solutions though: Out-producing the allies was out of question, due to internal resources strained to the limits: But the credo at the time, by mid-1943, was to win the war by technological superiority: German quality versus allied quantity.

Many “Wunderwaffe” projects, some dated back from before the war were looked upon again. For the Luftwaffe, it was a rush towards jets which culminated with the Me-262. For the Heer, tanks such as the Königstiger. For the Kriegsmarine, the “poor child” of German arms as always, it was the Walter boats. Dönitz became passionated about the project.

Albert Speer’s reorganization of the production meanwhile allowed a move towards inscreased production of existing U-Boats, which was simplified, modularized and atomized between a constellation of sub-contractors working in relative security, to mitigate the effect of allied bombardment.

As a result, U-Boat production was maintained despite all odds. Choices were made, like axing of the large and costly oceanic Type XB and minelayers or specialized types gradually cancelled to concentrate on the late versions of the excellent Type VII alone.

But the Type VII still had its load of limitations, the ones described above. One innovation though, the Snorkel, was very promising and started to be adopted, as well as radars and a more effective FLAK, or better torpedoes. But since 1941 already, the research bureau of the Kriegsmarine was looking for a more radical approach, destined to completely change speed underwater, and giving the submersible an almost unlimited underwater range.

No technology at the time could provide a direct answer, but one man at least had a solution, leaning towards a modern “AIP” (“Air Independent Propulsion”). From these efforts, the initial program leading to the Type XXI can be traced back. This was Helmuth Walter’s turbine, the awaited game changer. For more, see also the U-Boat Types.

Towards the pure submarine: The Walter Propulsion

About Professor Walter

Professor Walter had patented a motor fuel system that uses nitrogen peroxide, a very unstable product that had the advantage of allowing these engines to remain completely autonomous, with little or no vibration, and above all to stay in operation. It allowed diving almost indefinitely, at high speed. This revolutionary process quickly interested the Nazis, who commissioned a first project in 1933.

Professor Walter had patented a motor fuel system that uses nitrogen peroxide, a very unstable product that had the advantage of allowing these engines to remain completely autonomous, with little or no vibration, and above all to stay in operation. It allowed diving almost indefinitely, at high speed. This revolutionary process quickly interested the Nazis, who commissioned a first project in 1933.

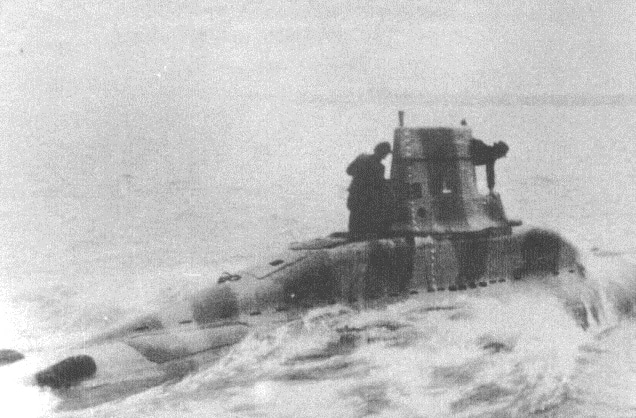

However the rearmament priorities lowered this program, and it was postponed. It was not until 1939 that the first “Walter Propulsion” submarine was built. The V80, displacing 75 tons, for 22 meters long, thanks to its refined hull shape, easily reaching 28 knots submerged. This was an absolute record at the time, only beaten with the 1960s SSNs of the cold war. The following V300 in 1942 inaugurated a high-pressure turbine. She started as the first operational submarine in 1943, the U-791, giving birth to the U-792 and 793, 794 and 795, armed with forward torpedoes, which went through month of gruelling operational service (see below). But even with the emergency, the Kriegsmarine was dubious, cautious with this new technology.

Walter’s U-Boats

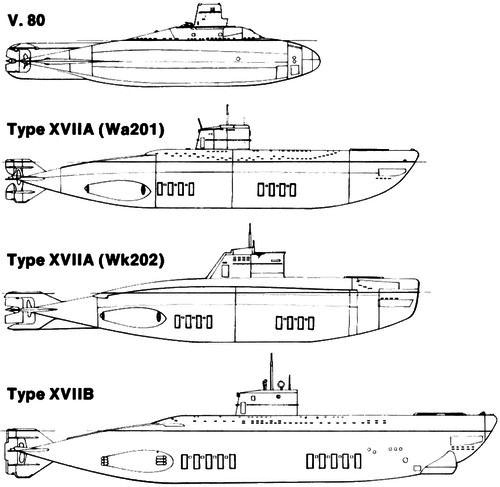

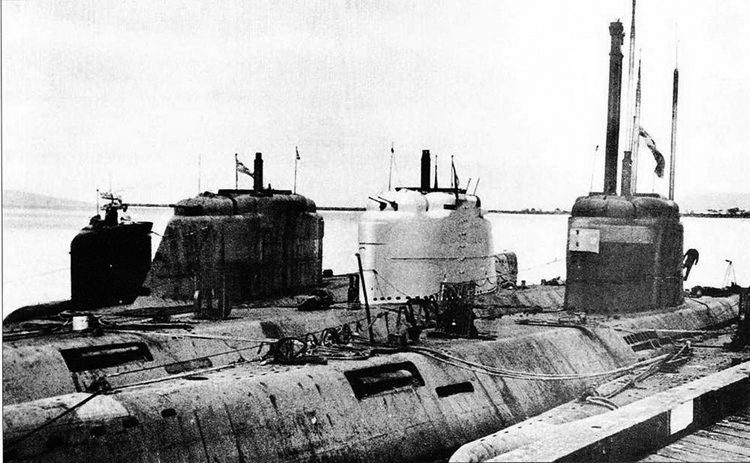

Various Walter Boats: V.80, Type XVIIA and XVIIB

The experimental propulsion that Professor Helmuth Walter advocated since 1931 was worth trying. A brilliant engineer her worked on a new gas turbine at the Germaniawerft shipyard (Kiel) from 1933, closed circuit propulsion system. Intended for submarines obviously, he proposed to replace ultimately both the electrical batteries and diesels by a new powerplant driven by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in a stabilized form, called Perhydrol.

This was a complex combustion process, but it helped creating a smaller, lighter engine with far less parts, occupying a small internal fraction of a normal U-boat, freeing space for whatever could be useful, like extra torpedoes. It was to stay for much longer underwater, not having to surface to recharge batteries and safely travel to its attack position. At the time, the Type VII did not even existed, but it was believed to be adapted on any U-Boat type in the works.

In October 1934, he proposed to the OKM (Oberkommand des Kriegsmarine) a special type of 300 tonnes U-boat, based on the Type IIA hull, but with a top speed of 26 knots and underwater speed of 30 knots, which was unheard of at the time: The average was around 7 knots. Endurance was also greater than the original, reaching 2,500 miles at 15 knots (500 miles submerged at that speed also). This “high speed U-Boat” however seemed far fetched, or had no practically use for the kind of submarine warfare thought at the time in Germany, just starting a gradual rebuilding of its submarine force, step by step.

Walter’s proposal was rejected as too unconventional, even deemed fanciful. Walter however never gave up. In 1937 he managed to show his revised plans to Karl Dönitz, at the time at the head of the small U-boat training flotilla. Dönitz was impressed enough to push for this project into the administrative echelons, through the top of the OKM, resulting at last in 1939 to a design contract. With war looming the proposal seemed interesting enough to fund a small research submersibles called V-80. But production out of the question.

V-80 was designed under supervision of Walter at Germaniawerft, Kiel, built under the greatest secrecy, on a slipway surrounded by a large fence. Launched on April 14, 1940 it was fitted out relatively quickly and started a serie of tests, at first in port, then at sea, and made a serie of dives. Test results, released in the spring 1940, with Walter himself at the controls, were brillant. As predicted, his turbine managed to propel his submersible to an amazing top speed of 23 knots submerged. This was a world record, quadruple of any model at the time.

It would wait second generation nuclear-powered attack submarines to reach that speed limit, such as the Soviet Alfa class (42 knots), so forty years later. Surface speed was also excellent, far better than any U-Boat in service so far. The turbines seemed also reliable at first, and although no max autonomy test was performed for safety, Walter was confident, the predicted range would be achieved.

The report, pushed by Dönitz into the OKM, made a sensation. The OKM upon this, suggested immediate construction of six coastal U-boats, based the V-80 design. Still, there was plenty of resistance in the U-boat department. They asked about how a real operational boat would perform, in proper combat conditions for such an untested solution. There were doubts also on how to manage a new logistical chain to hold the compounds involved in the combustion, and there was little room available in already hard-pressed shipyards to deliver the VII and IX U-boats, which seemed at the time more than sufficient for their task. In 1941 indeed, the results obtained by the early Wolfpack tactics were very encouraging. It was a war-winning strategy, dark days for the allies. Soon in early 1942, the “happy times” would commence for the U-boat arm.

Eventually, the OKM heard about these remarks and reworked the project to create a compromised design: The 600-ton V-300 (Later unique Type XVII, individually “U-791”). The goal was to produce a realistic militay model which can achieved 19 knots submerged. Construction started at Germaniawerft, but cancelled when Walter saw the design and told the OKM he could on the same basis obtain a much faster, 220 tons boat.

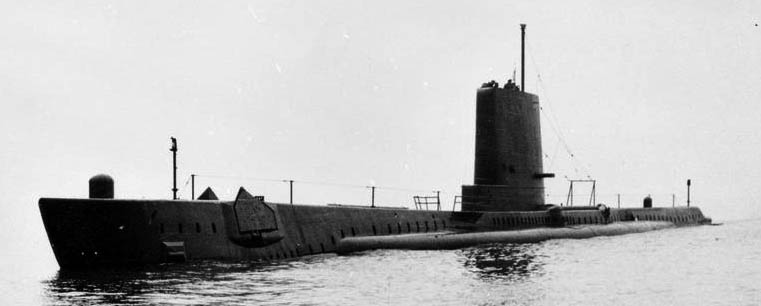

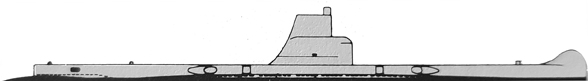

The semi-experimental Type XVII

A meeting with Dönitz in January 1942 had new contracts drafted, and awarded for 4 boats, all at Germaniawerft, Kiel, the Wk202 “serie” (U-792 and U-793) and in Blohm & Voss in Hamburg the Wa201 serie (U-794 and U-795), representing the Type XVIIA. Both series had the same dimensions but diverged in their shape and kiosk’s shape ad other details. They were armed with just two standard 21-in torpedo tubes for proper military evaluation. Keels were laid down eventually in December 1942 in both yards, with U-792 launched on 28 September 1943, followed by U-794, on 7 October 1943. Apart testing their powerplant, their goal was to training intensively to mimick combat conditions. As planned they reached 25 knots in 1944. In March 1944 U-794 performed a 24 knots run in in the Bay of Danzig, assisted by Dönitz and four other admirals.

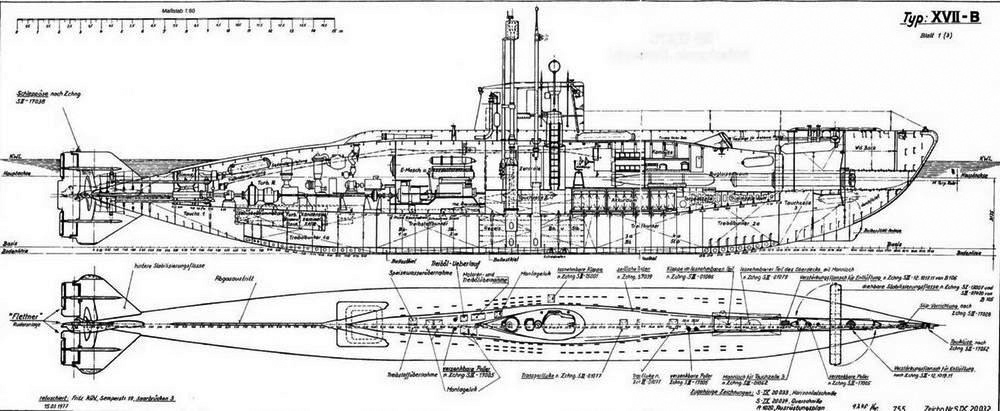

In 1944 also were started boats of the Type XVIIB, now a full serie. U-1405 to U-1416 were to be built in Blohm & Voss, Hamburg. They were longer, and had the same Walter gas turbine rated for 2,500 PS (2,500 shp; 1,800 kW), doubled by a single Deutz SAA SM517 supercharged 8-cylinder Diesel engine, 210 PS (210 shp; 150 kW) for the surface, at 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph), an AEG Maschine AWT98 electric motor, 77 PS (76 shp; 57 kW) allowing 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) submerged on electric drive alone, and 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) submerged (with the HTP Turbine drive). They carried the same two bow 53.3 cm (21 in) torpedo tubes with two ready and two torpedoes in reserve. But these were only coastal models, at 312 t (307 long tons) surfaced, 337 t (332 long tons) submerged and 415 t (408 long tons) total, reaching 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) surfaced. Only the first three were operational for a short while, scuttled in May 1945. The remainder, U-1408-U-1410 were incomplete when the war ended and the U-1411-U-1416 saw their contract cancelled. A dedicated article will cover them in the future.

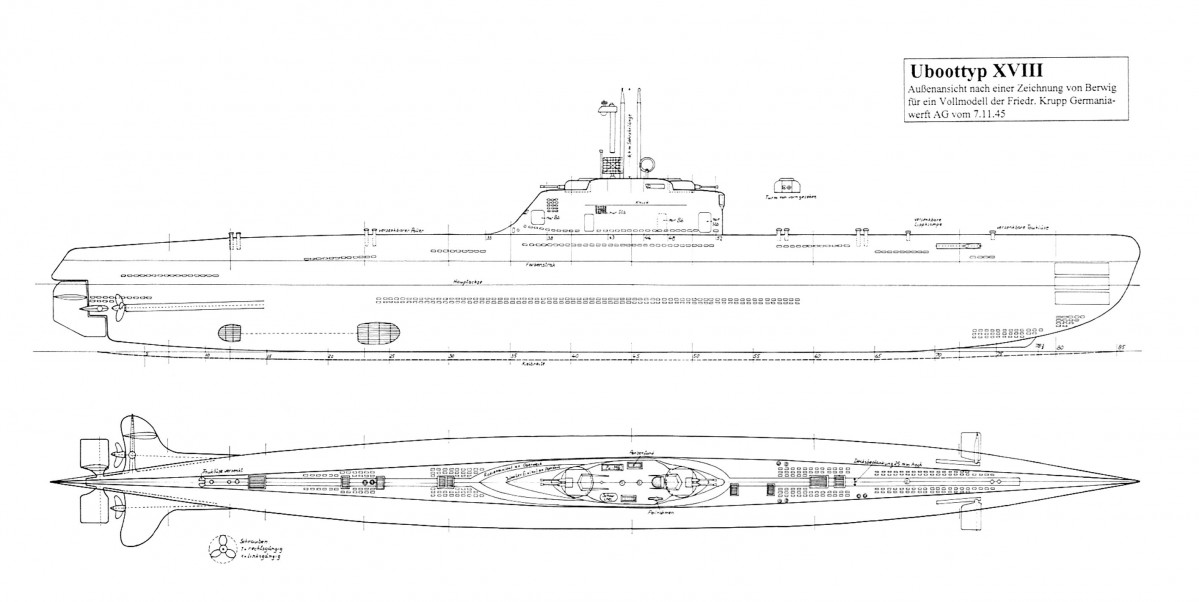

Well before this, back in 1942, Walter proposed this time a large military U-Boat, of some 1,475 tons standard, to be called Type XVIII. It could carry 23 torpedoes, for four bow tubes. Two contracts were awarded, on Jan 4, 1943, to Deutsche Werke, Kiel for U-796 and U-797, and then cancelled on 28 March 1944. In between, discussions betwen the OKM and Dönitz prioritized the XXI. This was simpler, cheaper “spin-off” of the Walter design, with a massive battery capacity, and not the Walter turbine. By this trick, the Type XXI was still able to reach 17 knots submerged.

Indeed, in between, tests performed by Kriegsmarine crews in near-combat operation in 1943 went to the OKM, and were less stellar about their performances: The complexity of three powerplants, and the turbine itself, was really above the average level of training asked from Kriegsmarine rating at the time, maintenance was complex and costly, totally captive of a very uncertain supply of Perhydrol, for which no solid supply has been planned yet. Also, it was found the fuel was highly flammable. In fact, the Royal Navy also had engineers working on such concept, and eventually abandoned it as too dangerous for combat.

The legacy of the Walter boats was not lost however. It did not went into cold-war models, which rather derived from the more conventional Type XXI, but found their way in concept, in modern AIP systems used for conventional “diesel-sub” atack submarines. Technology made giant leaps to procure a safer system and reach even greater speeds and autonomy. But it took more than 70 years to reach this level. Prof. Walter did not lived long enough to see his vision realized, when he passed away in 1980. Germany indeed embraced only in the 2000s the concept of fuel cells, now propelling the Type 212, 214, 218 and modified 208-1400.

The clock is ticking: Inevitable Compromises

Not only this research progressed very slowly, but the limitations seen above were considered too much for the Kriegsmarine organization and for combat conditions. Priority was given to a simpler model eventually: The type XXI, marrying the new hydrodynamic hull resulting from the advanced researches in this field (with large models in test pools), but a more conventional, trusted diesel, and incorporating a massive provision of batteries, which allowed a final 17 knots or 220 miles at 9 kts submerged, which was enough to “disrupt” allied ASW warfare, combined with the advantage of the snorkel, to make the subs “stealthier”.

It was not the powerplant hich eally set apart the Type XXI from all other submersibles of the time, but the whole “package”: Anti-vibration system to separate the powerplant, making it more silent at low speed, when diving, magnetic jammers against Deep-Charges, the snorkel allowing to stay indefinitely submerged but at constant depth, or an oil/air releasing system to confuse observers (believing a successful grenade attack was made), the new high-speed automated torpedo launch system, the latest magnetic homing torpedoes.

Externally it went as well with a completely new hull and sail shapes, result of years of refinements, calculation and tests, or the new semi-automated anti-aircraft system with remotelly operated electric turrets, a new listening system, more powerful and accurate for underwater detection. And the crew’s comfort was immensely improved because of more automation plus more internal space (with a smaller crew !) better facilities, freezer for food, more sanitation spaces, proper showers and even a bathub.

Development of the Type XXI

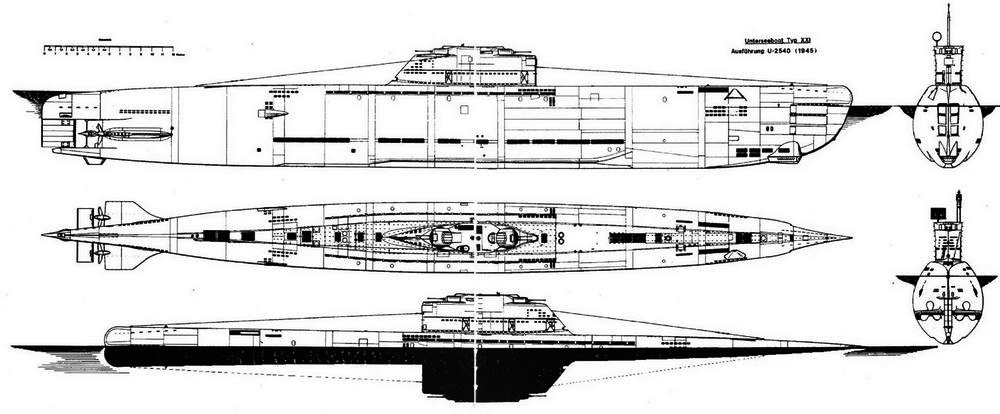

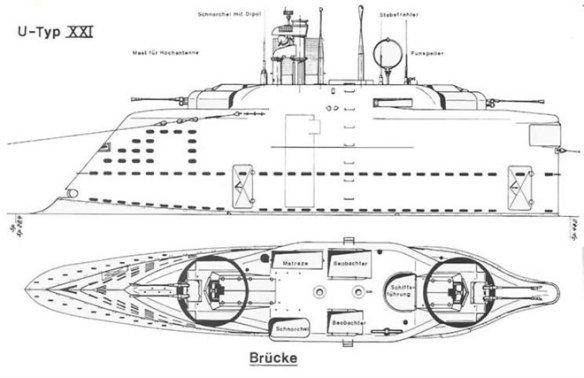

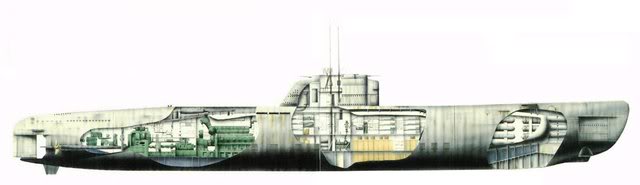

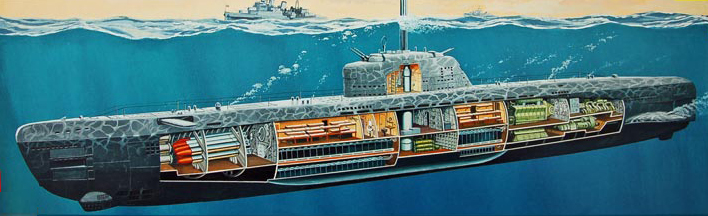

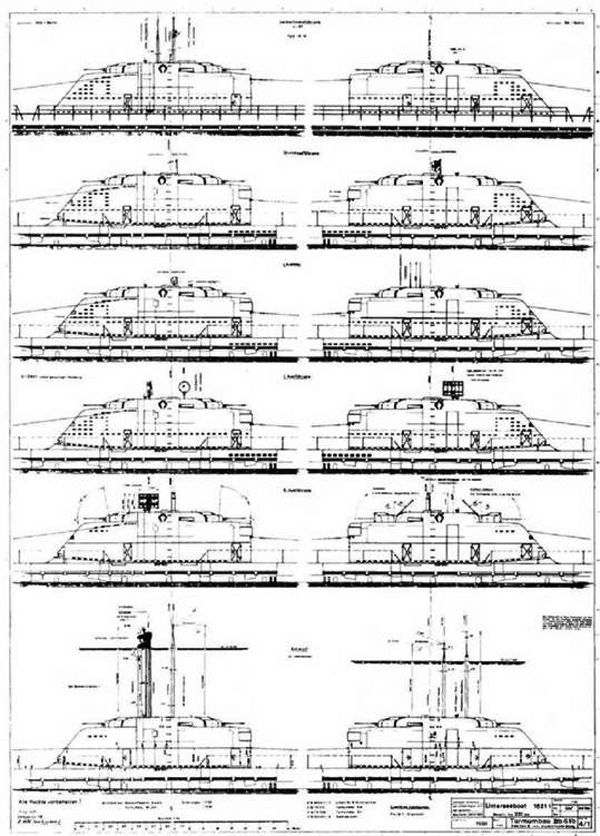

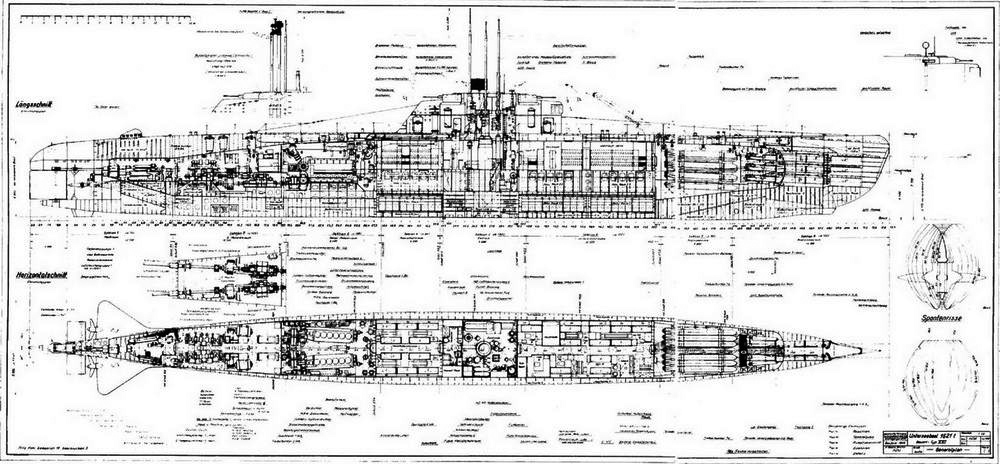

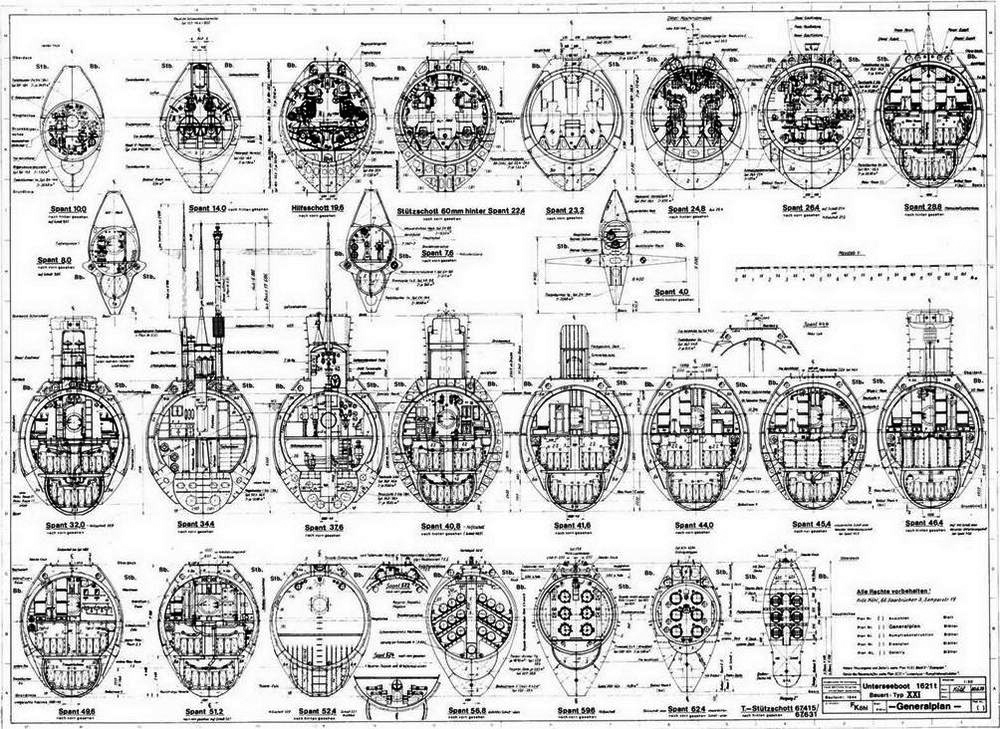

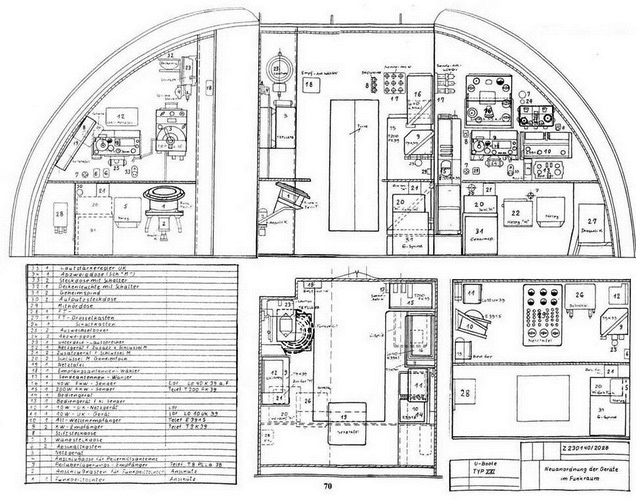

Overview and internals, original blueprints reconstructed by the Bundesmarine.

Paying a staggering price

To get from the 1930s Type VII and IX to this “spaceship” was not a smooth ride, though. The first trigger was of course the degrading situation in the so-called “battle of the Atlantic”: First signs of this came in July 1942 – February 1943 when losses rose steadily. The better organized US Navy for convoy escort, and massive output of shipyards on both sides of the pond, which indeed had a massive impact in the matter. But what really turned the tables was the famous “black may”, or March–May 1943 which saw increase ferocity on both sides, and only 39 ships (235,000 tons) were sunk for 15 U-boats destroyed.

Later in May, in a single convoy, 30 U-boats attacked, but only managing to sink 13 merchant ships, for the loss of six U-boats. This was one U-Boat traded for two merchant vessels. Already an unnacceptable price to pay compared to the 1941-42 ratios. All in all this month alone, 43 U-boats were destroyed, 25% of German U-boat Arm’s at the time. At this rate, seemingly increasing, the whole “battle of the Atlantic” would be lost within six months, unless drastic changes took place.

Since Dönitz was at the head of the Kriegsmarine from January, submarine warfare was given all priority and major surface assets were transferred to Norway to operate aainst the Murmansk Convoys and tie down a substantial part of the Allies in effort escort. Submarine construction had all priority and resources, manpower available and it went to the existing Type VII and Type IX as well as a few Type XIV for refuelling. The 1943 Fleet Building Programme notably had Dönitz peesuading Speed on the provision 40 U-Boats per month being completed, despite a growing lack of steel, in high demand notably for the Heer.

On late November 1942, the OKM send three naval builders to Paris for a meeting with Dönitz. Dönitz then started to number the losses: In 1940, twenty four, 1941 thirty three, 1942 a bit less for the first half, but it has been steadily rising since then as in July 1942, nine were lost, in August twelve, in September nine in October fourteen as for November, 80% of those in the surface. The core problems that he had submersibles, not true submarines. Statistics were clear about this: His U-Boots needed to stay underwater longer. He also gave his hopes for the the construction of the new Walter submarines, and the Type XXVIII the largest of these. But he also expressed his concerns about this untested tech and delays, the great industrial risks it represented.

One of the yard, eager to get an order fast, proposed to just streamlining the hull and doubling the electrical ppiwer, or even quadrupling it, while building a much larger submarine, preserving its surface qualities, notably in rough weather. Dönitz expressed doubts about the fact hos boats needed to surface often anyway, and he was told about a new “all-weather” Schnorchel model. Another expressed their idea about a semi-automated reload system for torpedoes.

Dönite became very interested and to conclude, asked for when this alternative type could be ready, and he was answered spring 1943. This was the birth of the Type XXI.

When the first designs were presented in June 1943, as imperfect and rough as they were, Dönitz’s fears came true as the previous “Black May”, losses has been crippling. Now was not the time for tedious half-measures. A new submarine was needed fast. Development of the new Type XXI from there, now officially named, was given all priority and the Walter boats fell into low priority; In the end, three times more batteries were planned, an armoured bridge and new streamlined hull were all in the works.

The new electrical power allowed, combined to the streamlining, to make seventeen knots underwater, but it still only existed on paper. Now the same builders that met in Paris by November 1942 assured Dönitz that the first boat would be ready… in late 1944. Dönitz by now had to make a very difficult decision to either give up submarine warfare entirely, or held his breath, took measures to spare his crews, and gamble on the new type, provided there was a way to have it faster.

Depite the losses, keeping the crews at sea, was the only way to have his men staying sharp, and even they did little damage at this point of the war, this ASW campaign still tied down countless allied ressources for convoy escort alone. Plus he would have experienced crews to make the transition towards the new type. Meanwhile, both the Type VII and IX still filled the order books of the three yards in charge of submarine production in Germany. They will deliver both types up to the last day of the war, but at a lower rate.

The year in between, from mid-1943 to mid-1944, Dönitz also frantically worked to improve the tech of his actual Type VII/IX. Until late 1944 they were continually improved. Better engines, better range, deeper dive, a schnorchel, new radars, and plenty of anti-aircraft guns. Kapitänleutnant Hartmann was the first to sail the new anti-aircraft submarine type, but even through, he was attacked by several British fighter-bombers and severely damaged, with all hi men on deck killed, himself and his staff. She was back to port commanded by …the medic on board, sole officer left. Reserve-officers got on board and a few days afterwards, she was at sea again.

Meanwhile, German shipyards were geared up to new forms of production setup for the Type XXI. Albert Speer, Hitler’s secret weapon for Germany’s production, was the minister responsible for this programme, promising deliveries in May 1944, well befoe anticipated. And he kept his promises (see later).

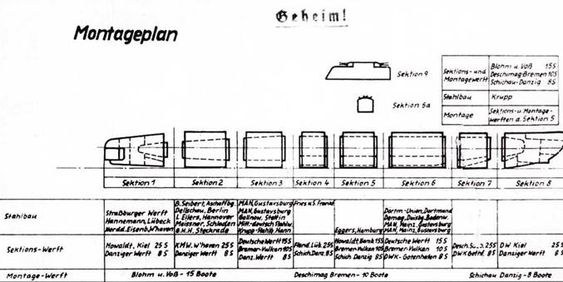

Production planning of the Type XXI

The while the year 1943, and early 1944, were fought with the same types, it’s only in the spring of 1944 that the Type XXI submarine was scheduled to reach frontline. Back in July 1943, the The Central Shipbuilding Committee and the new building programme knew that plans for the new Type XXI were not ready, the Walter turbines was now appearing not suitable for operations, and the “backup solution” was ready, although many technological issues were still at hand. So development was given time: The comittee envisaged the completion of the first two of them, as serie protoype in November 1944 and the pre-production prototype in December 1944, with trials in the spring of 1945. The plan also comprised a production of 30 boats a month by the autumn of 1945.

In addition, this programme presupposed that Speer was prepared to provide all requisite building facilities and work would proceed without interference by air raids or bottlenecks, which Dönitz found unrealistic. Soon the increasing number of air raids and destruction of Hamburg gave him credit. While he asked Speer to submit counterproposals, the latter granted the first Type XXI completed in Apri 1944, which left hope production would start sooner.

Both men eventually struck an agreement over which the new type was accorded all priority freezing any alternative naval construction, and they they would benefit for prefabricated, mass-production principles, possibly in well protected, bunkerized final facilities in which the various final modules would be assembled. If it’s looking very modern to us, it was at least groundbreaking for major naval construction. After all, the Type XXI were planned to be much larger even than the Type IX.

Instructions planning for the new U-Boat models started at the Construction Office in Glückauf, Blankenburg. The Autumn of 1943 saw first orders placed with contractors involved already to provide U-boat electric batteries, as well as those for the pressure-hull sections and a galaxy of sub-contractors. On 8 December 1943, constructional drawings were at least completed. On 1st January 1944, the new programme was submitted for approval, targeting the completion of a prototype in April 1944 as agreed by Speer, with another date of 30 boats completed by July 1944. There same program did not concentrated exclusively on the Type XXI. Considering quantity also had a quality, the first Type XXIII, coastal “Elektroboote” were to be completed in February 1944, plus 19 delivered in April (see later).

Final Design

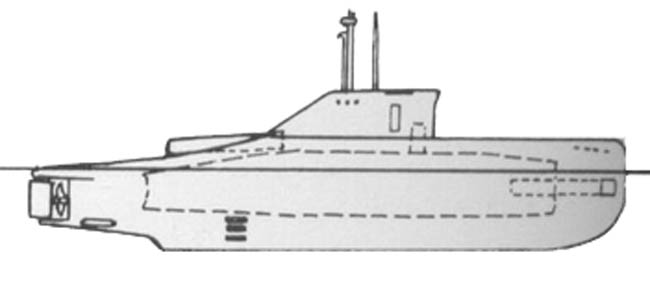

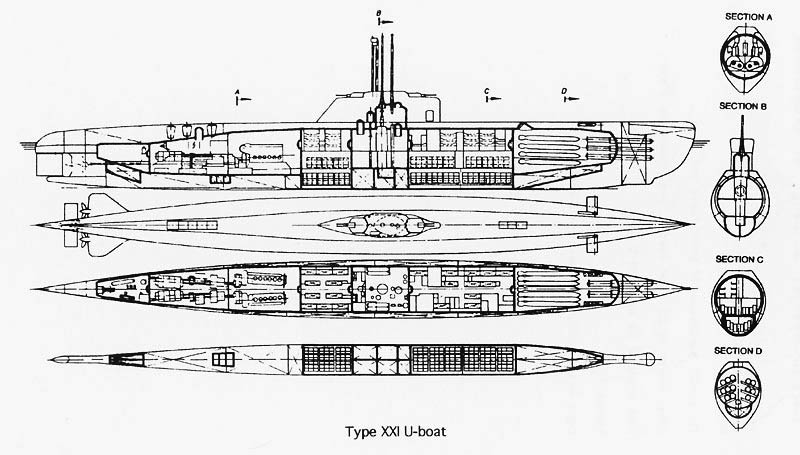

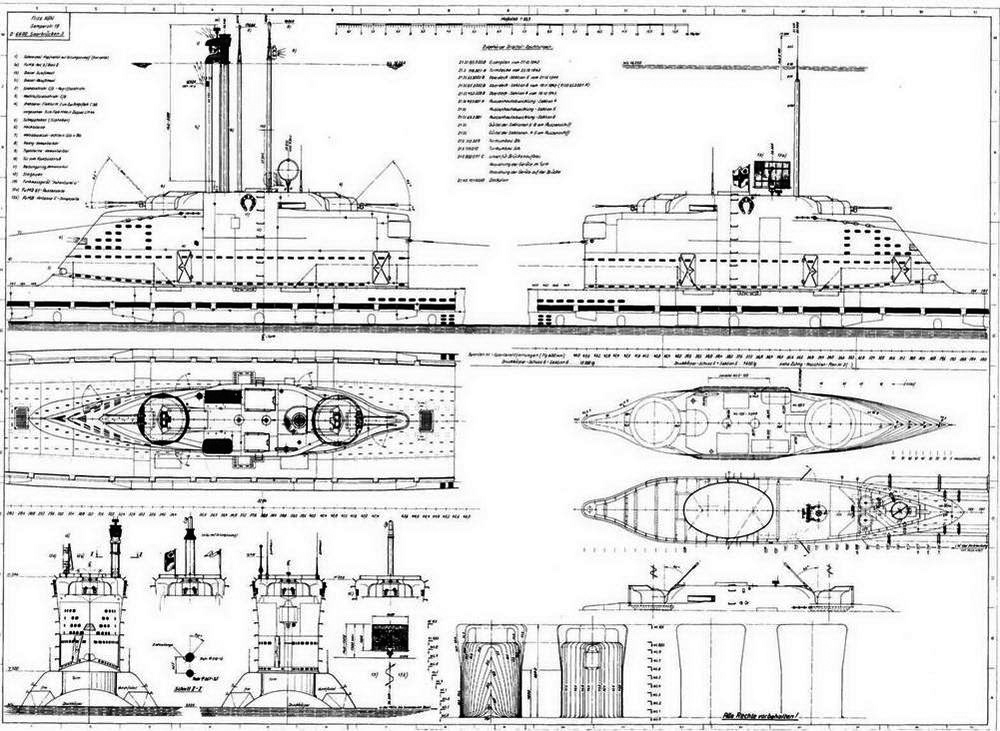

Inverted negative blueprint of the Type XXI.

General Overview

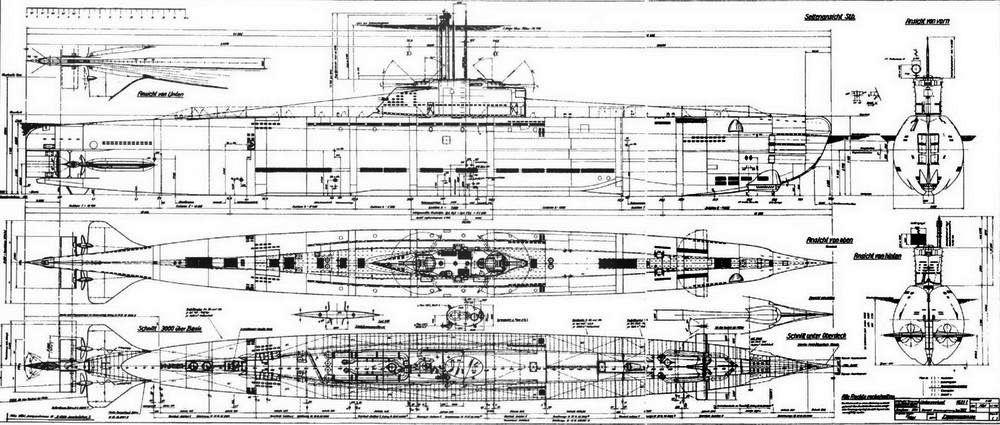

Colorized sections of the Type XXI- Green: living quarters, blue: central operation, purple: torpedo room, yellow and orange: batteries and accumulators, pink: Electric engines and diesels.

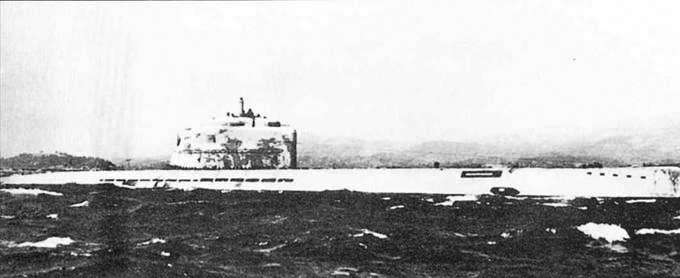

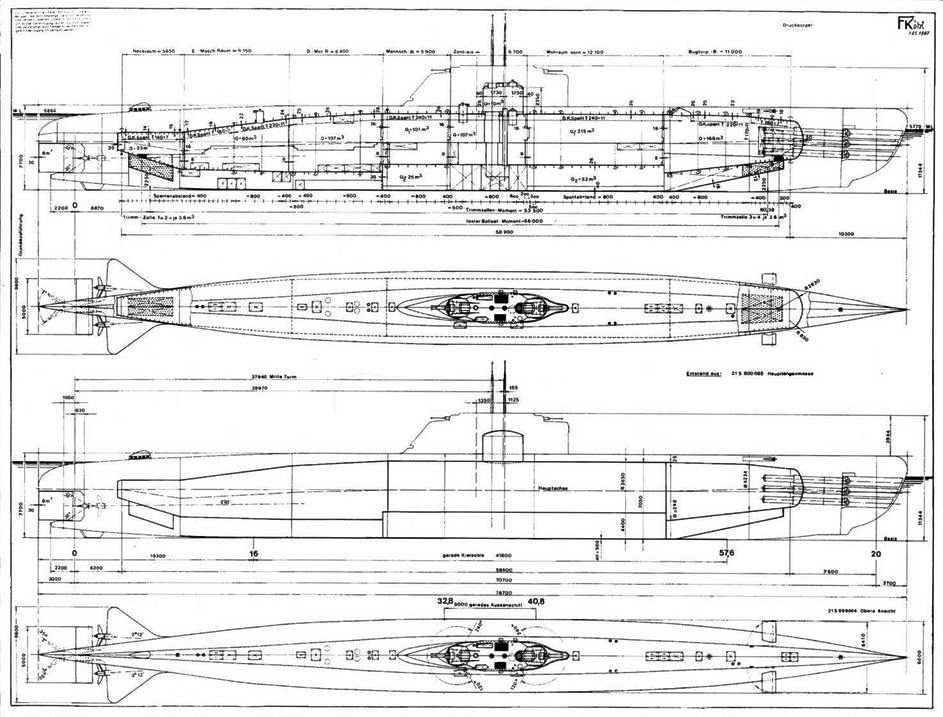

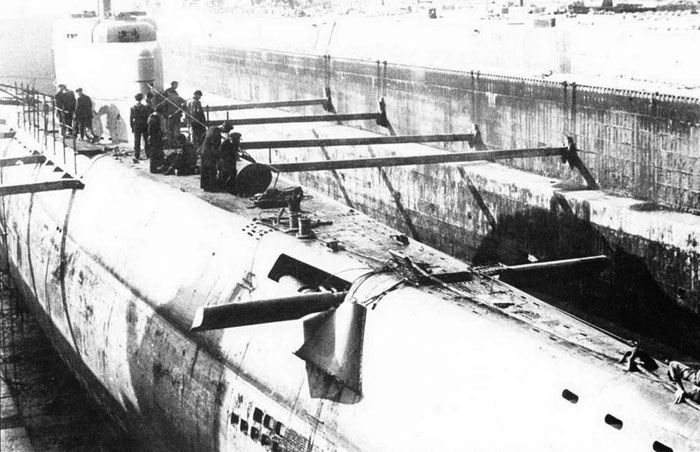

The general outlines of a Type XXI were nothing lile all previous designs, in stark contrast to the Type VII, IX and all the others. This was such a leap forward, early crews coming from older surviving U-Boats or new ones, trained on older models were just astonished to see something out of a Flash Gordon strip, a swatiska-carrying spaceship made for total superiority at sea.

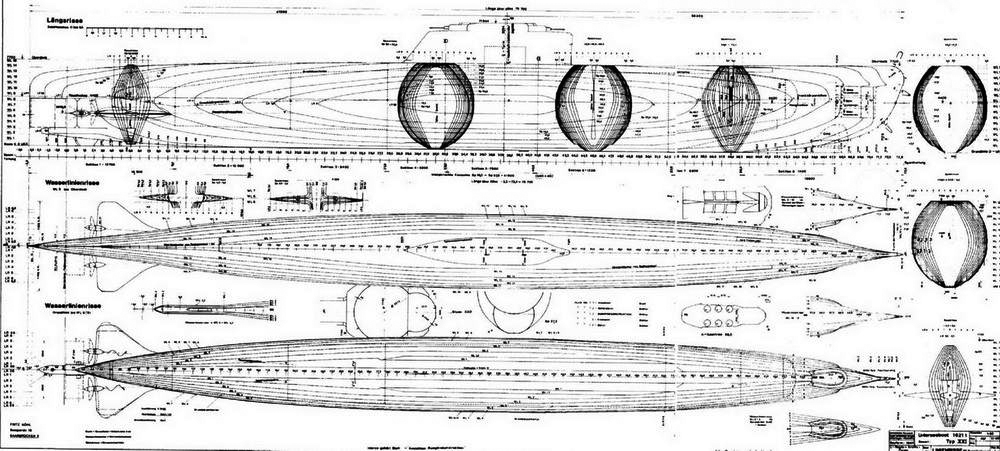

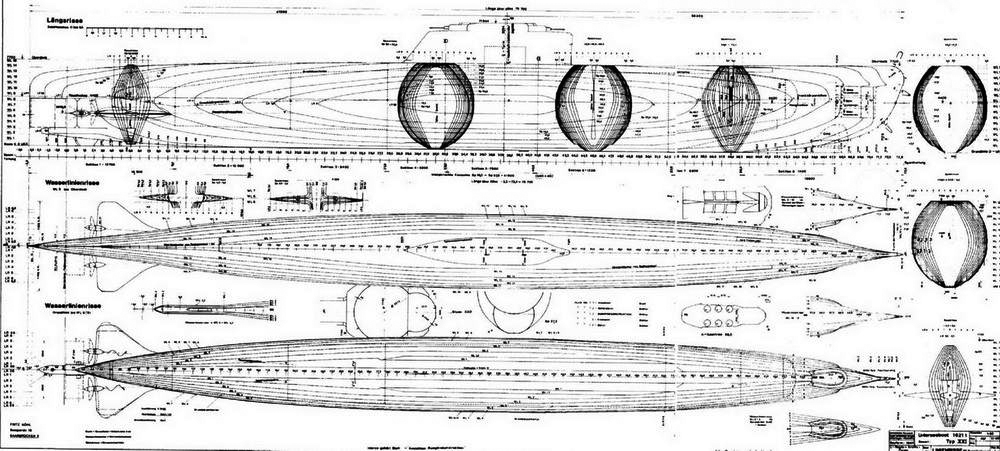

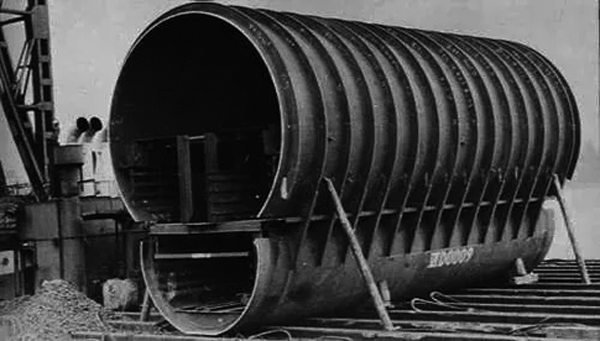

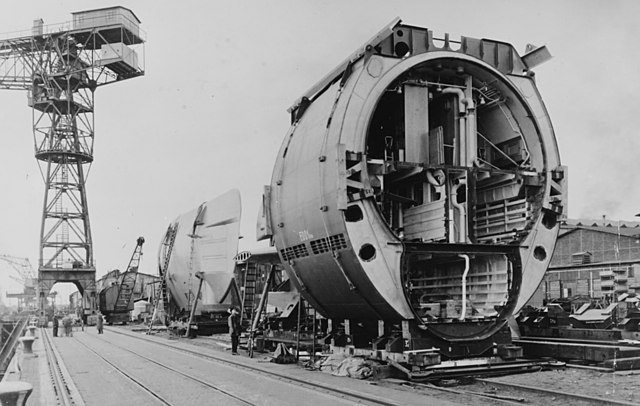

The fruit of months of basin researches, starting for engineered shapes to achieve the least water resistance underwater, the Type XXIs lost their “surface-first” approach, with a relatively conventional hull over waterline level, with a flat deck, and clear separation between the outer hull and pressure hull below, a cylinder and square-section above.

The Type VII blended all these shapes in a single elliptic section all around, blending into the flat deck, which was still there. This was calculated a creating less disruption at high speed underwater. Far before the “droplet style” of more modern SSNs, this was the first attempt to design boats able to reach great underwater speeds, and great care was given to define the best penetration rate possible. Outside the all-rounded sides, the outer hull was not much deeper, but longer overall, creating a greater buoyancy reserve.

Crucially, the bow was no longer “clipper-like” but rounded, a feature universally adopted in cold war years (like for all converted “fleet snorkels”). This rounded bow indeed ctreate les turbulences at great speeds underwater. The forward part was still fine and narrow, sich its cutting edge below the bow curve, facing the three torpdo tubes forward, enclosed in recesses, with each their own shutter, as for previous classes. When closed, the hull was much more streamlined. Above the tube, in the inwards recesses directly below the bow was the larger section of the upper bow. The lower part, below the tubes, was thicker and reinforced to mitigate any impact on the seafloor or obstacle.

Not far below, mid-way of the downward curve, was installed a protruding sonar installation. The ends of the lower bulge was blended with the next belly section. As all previous types, the outer hull was dotted with filling ports all along. The inner pressure hull was about 50% volume compared to the outer, thinner hull. It stopped about 10 meters from the bow, mid-way at the torpedo tubes, and went aft about the same distance from the stern, at the end of the machinery space, which occupied about 1/3 of the total lenght, same for the crew spaces and battle stations in the middle, and the smaller section forward being used for the torpedoes. This space was reduced due to its automation. There was small access hatch for maintenance, but it was no longer crammed with railings, chains and pulleys needed for manual reloading as in previous boats. Nobody slept there either.

The last external changes were of course the absence of a deck gun from the start, and the AA armament in remote turrets fore and aft of the main island, which was itself self-enclosed and streamlined unlike previous “kiosks” opened conning towers with wave breakers and AA platforms. The new island was bulkier, but way cleaner. The central section was also the largest, both in beam and height, with three stages for the first time in any German submarines: The upper one was the main living quarters, with triple bunks for the crews, close to the central, which location did not changed, but this time over three levels, whil the rest of the two lower decks were entirely occupied by batteries, placed at low as possible for gravity. Cumulated with the island that was two-storey high, the Type XXI were the roomier and tallest German submarines ever built.

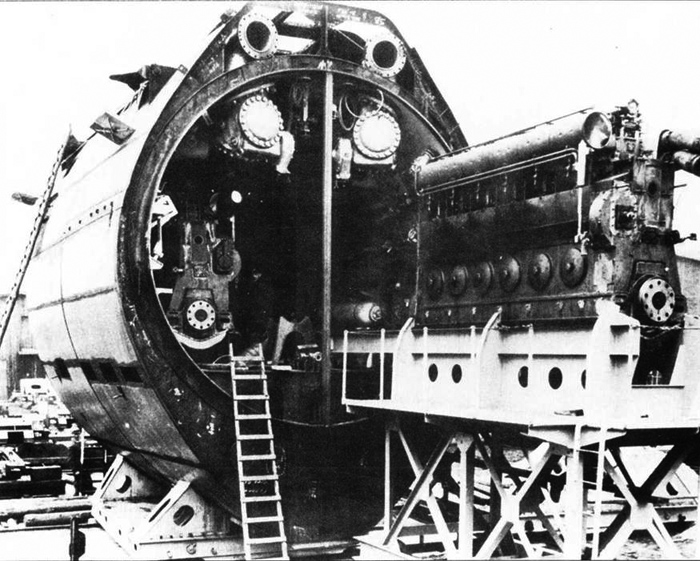

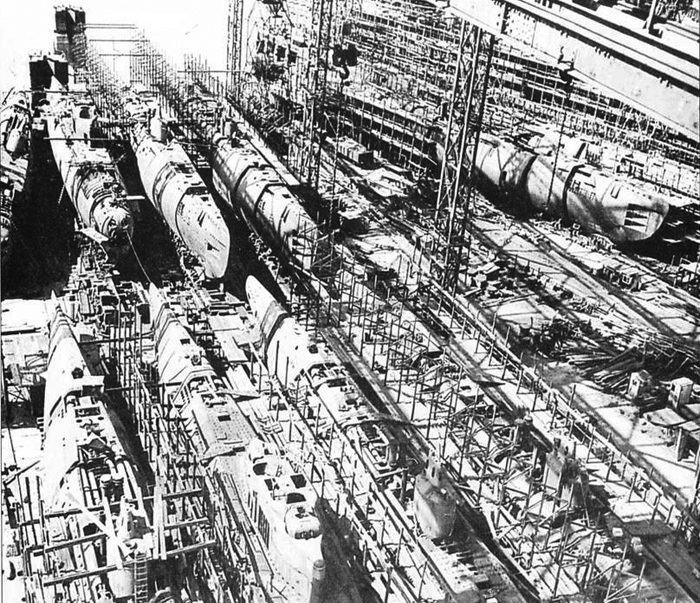

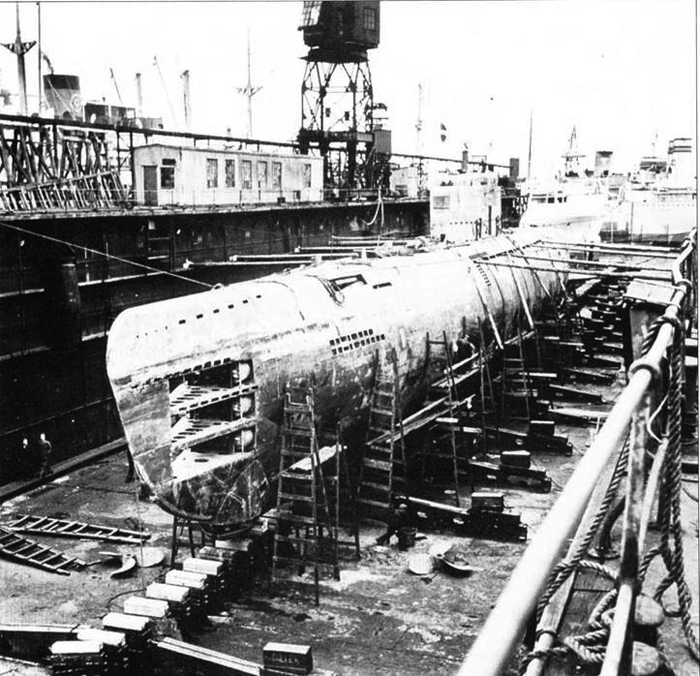

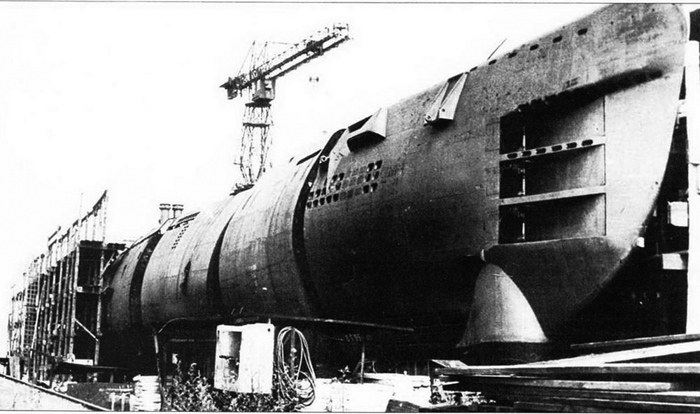

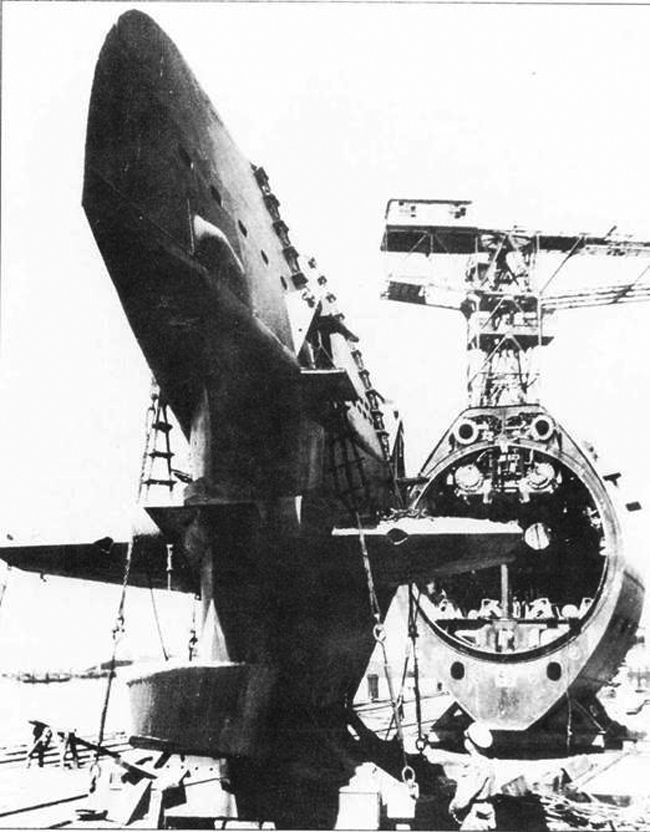

Modular Construction

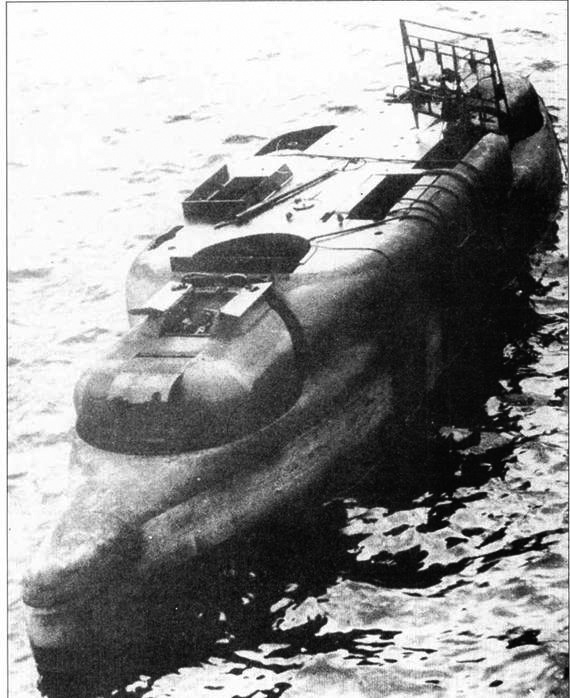

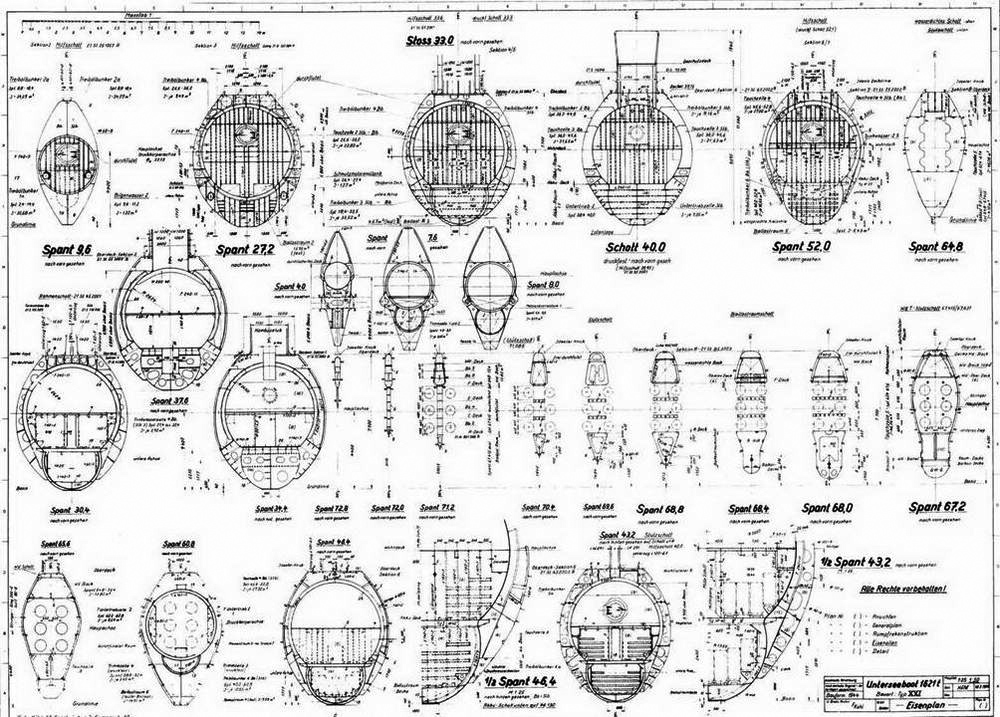

The Type XXI sections in details. Note the kiosk, rebuilt postwar: This shows the Bundermarine’s Wilhelm Bauer.

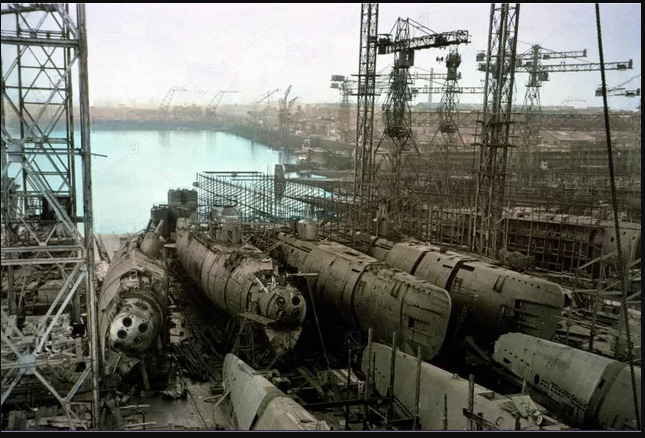

The Type XXI comprised eight separate sections, each being its own sealed compartment, with safety hatches. These ovale sections were constructed in 13 different yards. This allowed on-site duplication and taylorisation with assemblu of sub-elements, often coming from other suppliers. This ensured that if a number of sections were destroyed in one yard, other provided the same sections. Redundancy complicated the chain supply though for each manufacturer.

Safety of this section-building up to the final assembly in the naval yards rose concerns as the most exposed, tipping point of the whole manufacturing chain, and in 1944 efforts were made to provide bomb-proof sheltering. The largest bunkers ever devised in Germany, larger even than the ones designed to protect in France U-Boats (the “u-boat pens”) was exemplified at Hamburg-Finkenwerder and Bremen-Farge, the two prototype buildings to deliver sections. A few others were improvised in less sensitive sites. Due to their size, sections could only be transported by water, whiwh restrained the list of possible sites.

A section-building yard was supplied with similar part-sections for the first section, like thee stern, with delivery of the remaining parts timed to ensure completion in sequence. At any given time, the same number of sections were always in progressive stages of assembly at each yard. Larger part-sections machined and prepared for assembly in the central line, corresponded to smaller ones from machine shops, on a conveyor-belt, creating a tree-like supply, typical of taylorisation. Same operations were repeated on each section by the same skilled team for speed.

The delivery of these completed sections ended in the U-boat assembly yards. There was one in Bremen (Deschimag), another in Hamburg (Blohm & Voss) and a third in Danzig (Schichau). Final assembly consisted in welding the section together, and fitting the last large parts (like the prop shafts), the island, etc. up to the launching under a strict time-table. Difficulties arose in early stages as many issues were discovered and fixed along the way to provide this smoothness.

Section-building yards initially were unable respect their schedule, mostly because of a delayed delivery from subcontractors, especially for the most crucial fittings, which blocked all subsequents steps. Also, the first part-sections sometimes were badly rolled, exceeding their specified tolerances when arriving a the final assembly yard. They often necessitated additional work. In addition, in the rush to keep the schedules, some supposedly complete sections arrived not only late but unfinished, requiring supplies and additional work.

The Central Shipbuilding Committee permitted no shifting in the tight schedule, ruthlessly insisting on their strict observance. This cause launched boats in such as state they needed much work remaining, pushing back for many weeks and even months any completion, and thus, commission. A lot of these finishing tasks were either botches or skimped entirely, which later forced the newly commissioned boats, long periods in dockyard to fix discovered issues. The first seven boats batch was therefore the most laborious of the whole serie, and crews were suspicious of their own safety onboard. The Kriegsmarine after a few trials, kept them for training and experimentations.

The whole program was so challenging, it grew tension and antagonism, even in the Central Shipbuilding Committee itself, but also with the Kriegsmarine Naval Command and dockyard authorities as well. It’s only by the summer of 1944 that there was some noticeable improvements, after weeks or ironing out the whole process and reorganizations. The Shipbuilding Commission under Admiral Topp was instrumental in this, created earlier that year, and acting as mediator and consultant, notably between the Naval Command and Armaments Ministry.

All was done under nerve-wracking reports going from all Germany to the administration of the Armaments Minister, caused mostly by bombing, which destroy assembly sites, the stopped the sub-contractors supply, or, in large final assembly yards often bombed, complete flight of dockyard workmen, notably in Hamburg and Dantzig. In the latter, the collapse of the Estern defence meant the destruction of bridges, pontoons and cranes badly needed to carry the sections. Most often in 1944, work was transferred to other, less exposed factories, and as much as possible, smaller parts were made by slave labor in tunnels, caves and underground.

Despite all odds, unthinkable production rates were meet: 234 U-boats were built in 1944 (220,000 tons), versus 238 in 1942, just as the bombing campaign was ramping up. The highest monthly rate was in December 1944, in which 31 submarines, including 22 of the new Type XXI were delivered. It was just 24 in October 1941 or 23 in November 1942, 28 in December 1943. Despite more and more severe bombins, the average monthly rate in the first quarter of 1945 stayed very high, and the continuous smoothing of the assembly process all along. Nevertheless, by transferring naval construction from the naval command to the minitry meant completion of the program time rose from eight to twelve months, so five behind schedule.

A set of Revolutionary Features

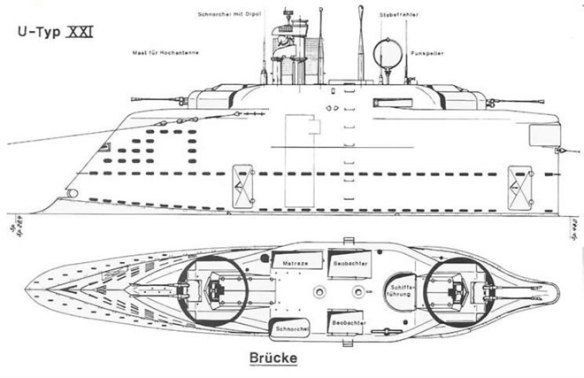

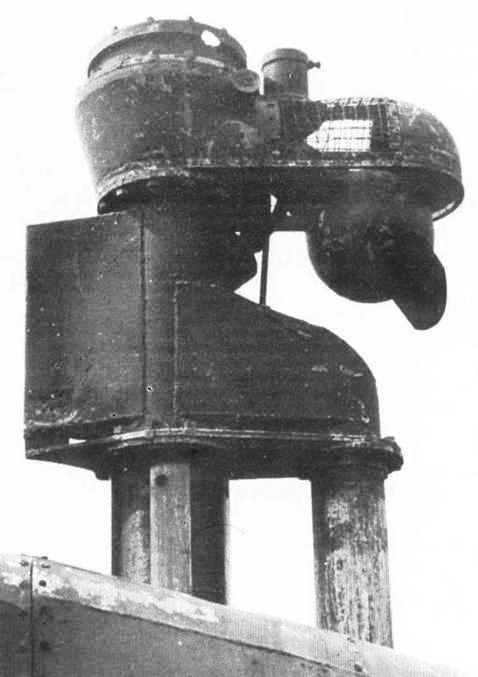

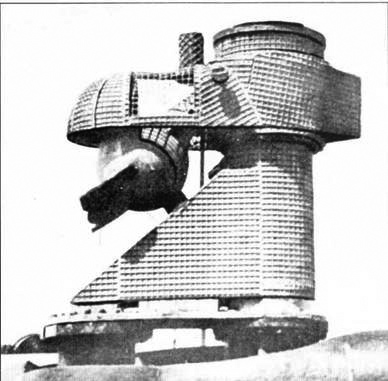

Design of the Type XXI Island

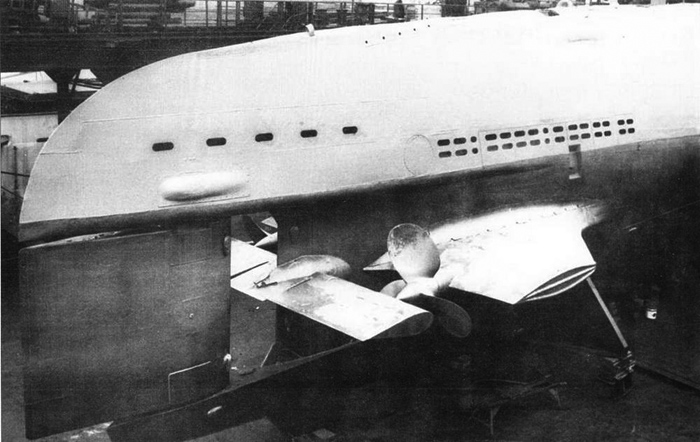

Aft view, from the reconstructed plans based postwar on the Whilhelm Bauer.

Hull Construction

It was suppose and announced thicker and stronger for deeper dives, and essential part of the design.

Details from the February 1946 British Portsmouth Commission report:

Plating is generally 4 mm (.16″) thick, splinter protection 17 mm (.67″) thick provided for the bridge and gun positions across the top, along the sides and at the ends. The material for the splinter protection is identified as “Wsho/Mo”, but its characteristics are not known.

Citing “The vertical keel extends aft from the fabricated forward structure, forming a deep centerline division extending up through the forward trim tanks and WRT tanks, to the forward end of the forward battery, where it is reduced in depth to 285 mm (11.2″) and extends aft at that depth to the after end of the after battery, except for the section in the way of the variable tanks, which is carried as a centerline bulkhead up to the pump room deck. Aft of the after battery it is carried at the full depth from the sole plate to the bottom of the pressure hull as far as the forward end of the after trim tank. It is carried aft through the after trim tank, but does not extend below it, as the longitudinal member at the bottom of the vessel is a bulb tee 120 x 6.5 (4.72″ x .26″). Connection is provided at the after end of the trim tank to the cellular structure which carries aft into the tail of the vessel”.

And also: “The stern frame of a casting (a weldment is permitted by the specifications) with carriers for the rudder and for the stern planes. Also at the after end of the vessel is a pair of fins which serve the dual purpose of stabilizers and struts for the propeller shaft bearings. As shown on plans, the fins are the widest part of the vessel”

Overall: “The hull structure is an interesting solution to the problem presented, and is a radical departure from previous German practice. At the same time, a number of the design details could have been improved. A number of details characteristic of previous types have been retained”

As for the critics, also noted by the German themselves:

-The method of connecting the upper and lower segments in the way of the battery compartments is generally faulty.

The commission also noted (absent from German reports):

-Noted failure of the lower segment under test below the designed value.

-External frames are deeper, but their are close to earlier vessels.

-Flanges have not been widened to improve the lateral stability of the frame section

-Unsatisfactory bulkheading, with collapsing pressure 50% as the designer’s spec

-Retention of bolted plates, rivets in shear is questionable.

-Weakness in the interruption of the circular section at the bottom of the vessel,

substitution of a heavy sole piece and,

additional deck and floors, detrimental to the stress distribution.

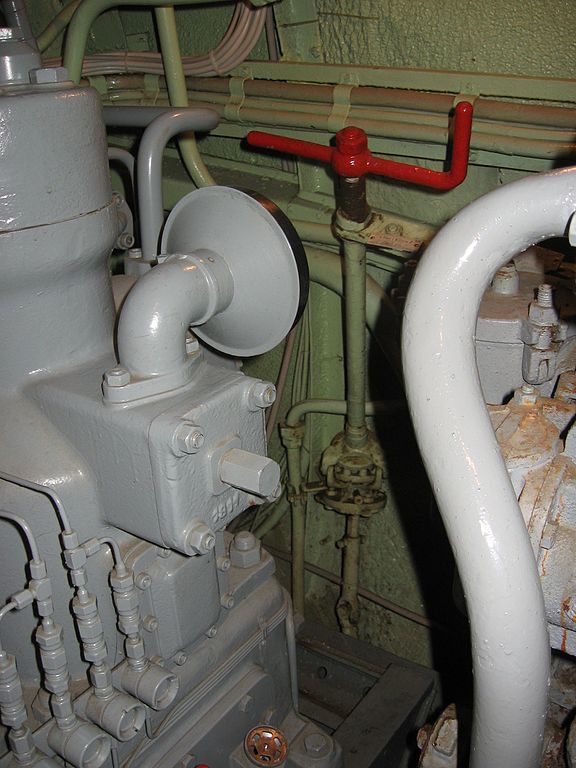

Powerplant

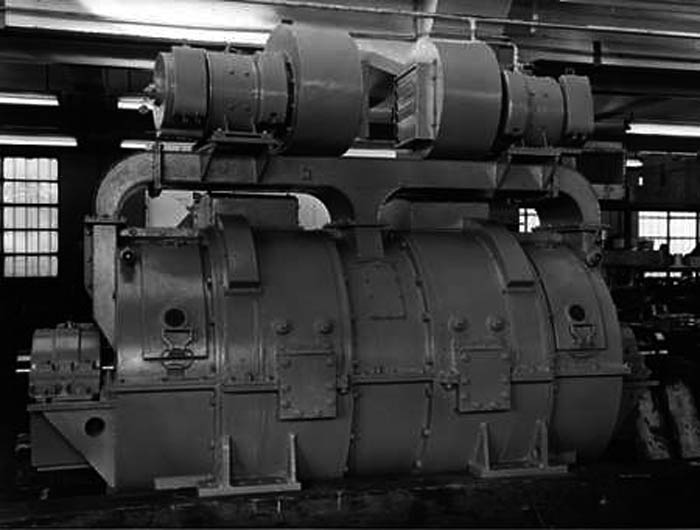

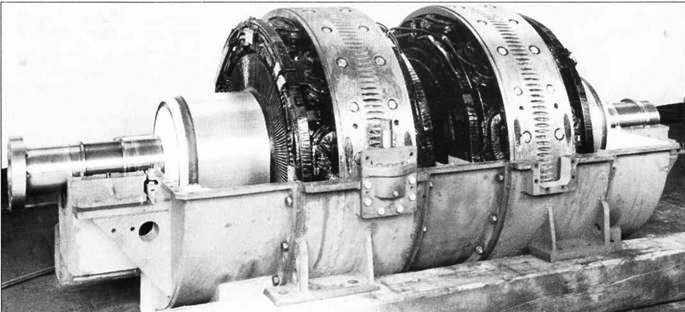

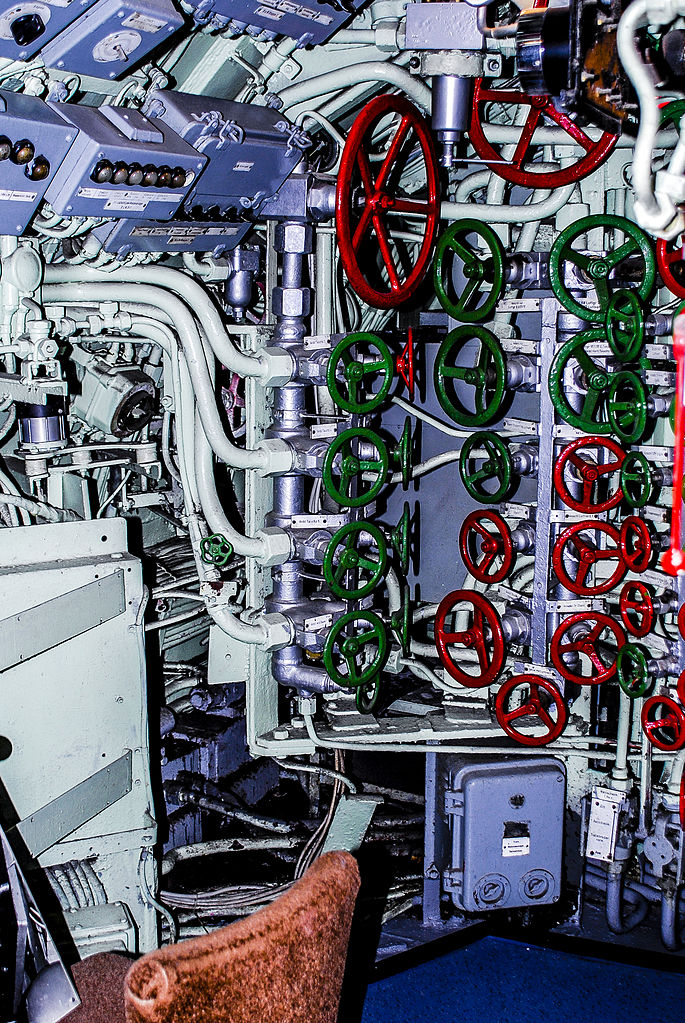

Hertha electric engine of type XXI Siemens-Schuckert AG 1944

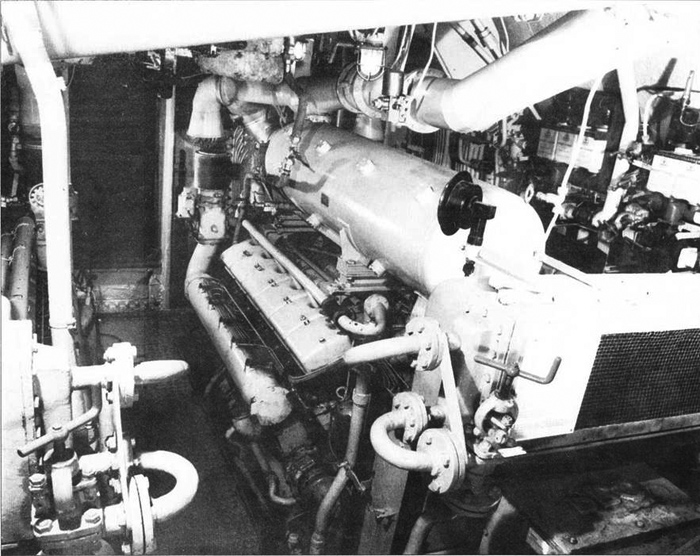

As a matter of fact, despite the absence of a Walter Gas turbine, the Type XXI was a diesel electric, equipped with three powerplants for various uses:

Two MAN M6V40/46KBB

Diesel assembly into the first powerplant section (the second had all four electrical motors)

6-cylinder diesel engines, rated for 4,000 PS (3,900 shp; 2,900 kW) For surface navigation. They were used to power the Batteries, were lighter units, taylor-built for the Type XXI since space needed to be gained for more batteries, and on paper, were less powerful than those onboard the Type IX/VII.

The only way to mitigate that shortcoming was to add a supercharger using exhaut gasses, workong at 520 RPM Max. The major problem is that these new injectors were deficient when the Type XXI was produced, and proved to be woefully unreliable, leaving the diesels to their lowest basic output. As a result, surface speed suffered. As a comparison, the Type IX-D/42 had 9,000 horsepower (9,100 PS; 6,700 kW) for more than 33 kts.

The second point of interest was the schnorchel, which was supposed to feed the diesels underwater. This innovation was already applied to the Type VII and IX, however the system onboard the Type XXI was created with a new valve system for heavy weather (see later). Nominal surface speed was to be 15.6 knots (28.9 km/h; 18.0 mph) surfaced.

Two SSW GU365/30:

Battery accumulators (Bauer)

Double-acting Hertha electric motors from Siemens-Schuckert, with an output of 5,000 PS (4,900 shp; 3,700 kW) at 1675 R.P.M. These were the main electric units, bringing far more power (five times more) than the Type IX. The latter, which were lighter, had the SSW 1 GU 345/34 rated for 1,000 PS (990 shp; 740 kW). These were supposed to provide 18 kts to the new boats, later re-rated at 17.2 knots (31.9 km/h; 19.8 mph), versus 7.7 knots (14.3 kph) for the Type IX, but in reality were re-rated by postwar assessments to 15.

Two SSW GV232/28:

Silent Running electric motors. This new system was to provide a stealthy final approach (inside the convoy). Howeve that feature was at the time too advanced for the allied tech, largely relying on active sonar systems. Also built by Siemens-Schuckert, they provided 226 PS (223 shp; 166 kW) at 350 R.P.M., for 6.1 knots. As for batteries, Six battery divisions, each with 62 cells and 1300 A.Hr. (Cell type 44 MAL 740E) were provided.

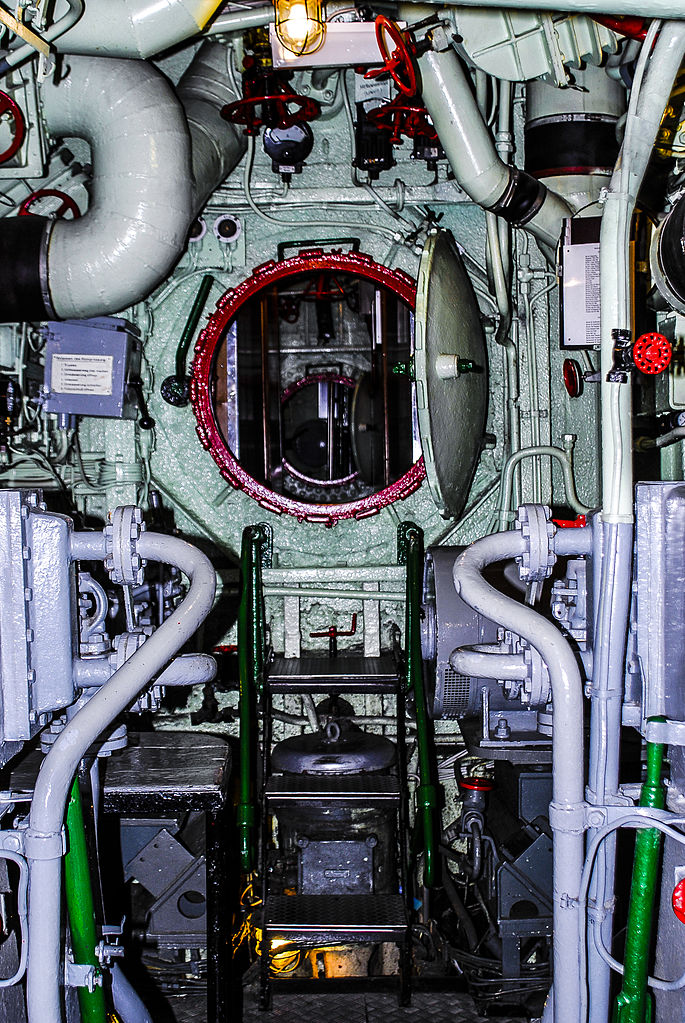

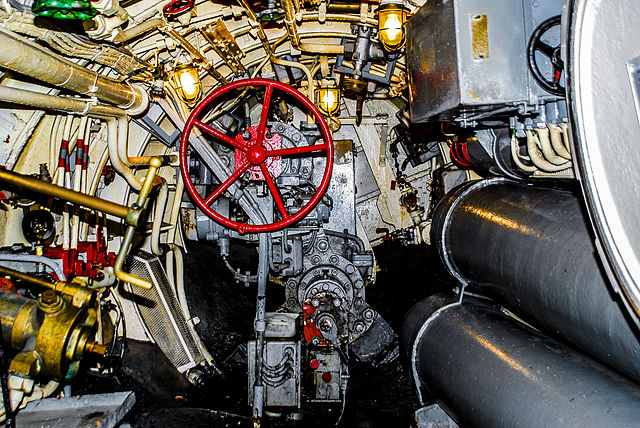

Sas/hatch to the Machine Room

| ⚙ Performances (British report) | |

| Cruising range – normal | 15,500 mi. @ 10 kn. 2 engines |

| max. speed | 11,150 mi. @ 12 kn. 2 engines |

| submerged | 365 mi. @ 5 kn. 2 engines |

| // | 285 mi. @ 5 kn. |

| // | 170 mi. @ 8 kn |

| // | 110 mi. @ 10 kn |

| Surface speed – max. | 15.6 kn. |

| Submerged speed – 1 hr. rate | 17-18 kn (sustained) |

Range/Autonomy:

The other strong point was the new boat’s range, both surfaced and underwater. The hull was roomier and could accomodate more fuel oil, resulting in a surface speed of 15,500 nautical miles (28,700 km; 17,800 mi) at ten knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). To compare with the Type IX, the latter reached 13,450 nmi (24,910 km; 15,480 mi) at the same speed, so this was a clear-cut improvement, however not really tested or corroborated in post-war tests. On paper, the new Schnorchel was to enable that same autonomy at eriscope depth all the way, albeit at a slightly lower speed.

But the real “game changer” at this stage of the war, was of course their submerged autonomy, which promised to be formidable: They could indeed cruise over 340 nmi (630 km; 390 mi) at 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) while submerged. For comparison, a type IX could only cruise for 63 nmi (117 km; 72 mi) at 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) while submerged, a Type VIIC 80 nmi (150 km; 92 mi) also at 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph). So this was, on paper, 3-4 times better, allowing an U-Boat to start from the Jade estuary, Wilhelmshaven, then reach the confines of the Gulf of Gascony (Bay of Biscaye), or well past Scapa Flow in Scotland. With the new Schnorchel it was even possible to reload the batteries while staying at periscopic depth.

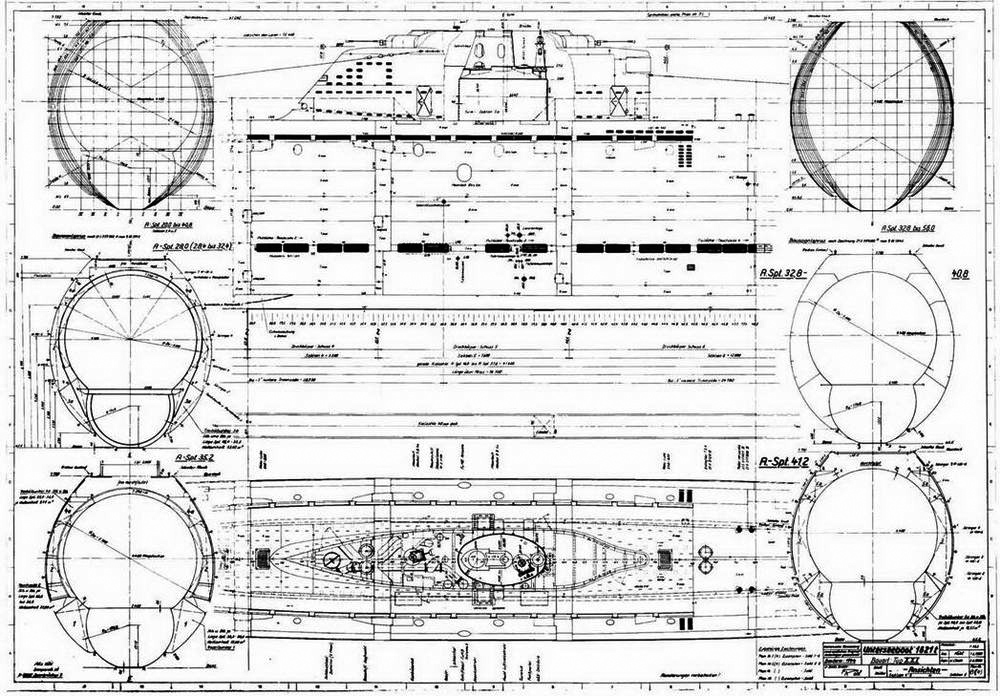

Submerging faster, Diving deeper

Other points that were specified to escape allied escorts, was the ability to dive fast, 20 kts on paper, and dive far deeper than any other u-Boat before. The first was achieved thanks to more filler ports along the outer hull and even the island, and a deeper, larger hull with more capacity, added to more powerful bilge pumps, hydraulically powered.

To dive deeper (Up to 300 m, which was the theoretical crush depth) enginers simply made the pressure hull far more thicker, and this was provided by Dönitz be granted by Speer and extra provision of high grade steel. The issue there however, was entirely related to the construction method by separated modules: The way they were jointed together was absolutely crucial for structural integrity.

But at the end, the Type XXI were able to dive at a test depth of 240 m (787 ft), 10 meters miore than the Type IX, and same for the VIIC, which was less than the 280 m anticipated. Some post-war tests rated this even only at 200m. So overall it was marginally better, and construction defaults had it toned down further.

It shoyuld be noted also that, if the hydraulic system was to fail, there was an emergency backup system for the steering.

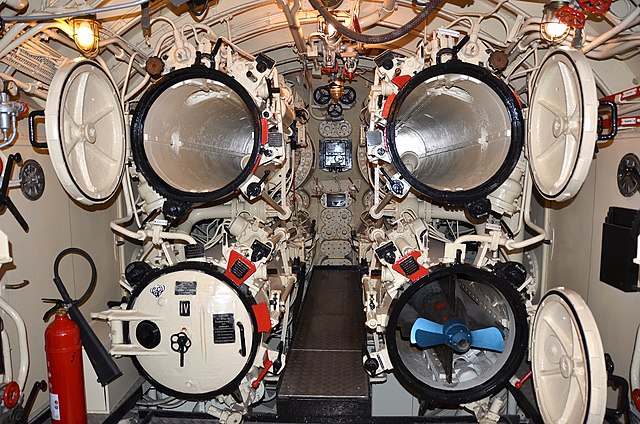

Armament

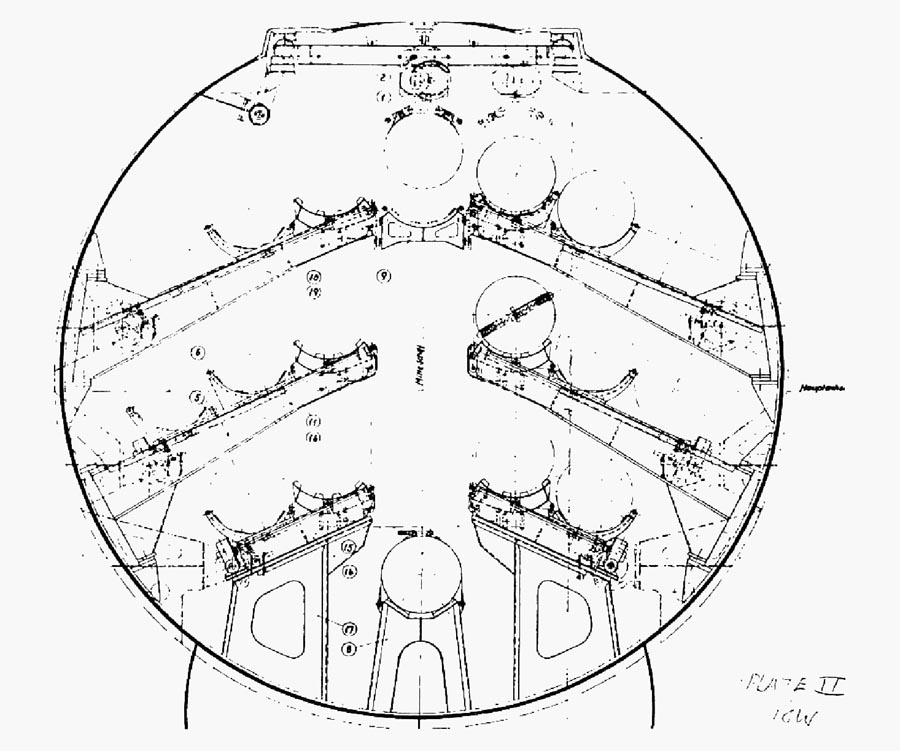

Torpedo Tubes

The Type XXI were the first to get rid of their stern torpedo tubes. It was found that firing their torpedoes submerged, using the new acoutic system was enough of an advantage, and getting rid of stern TTs spared spaces for the powerplant. So the Type XXI ended with just their six forward torpedo tubes, always the standard 21 inches (53,3 cm). These tubes could fire a larger variety of torpedoes than all previous models through, had a revolutionary loading system (see later) and could also launch 12 mines also via the tubes.

New Torpedo Models

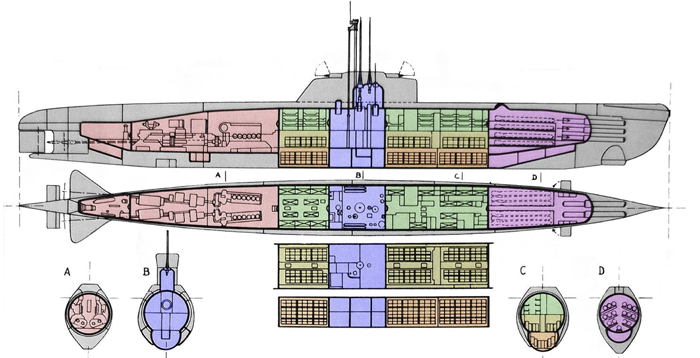

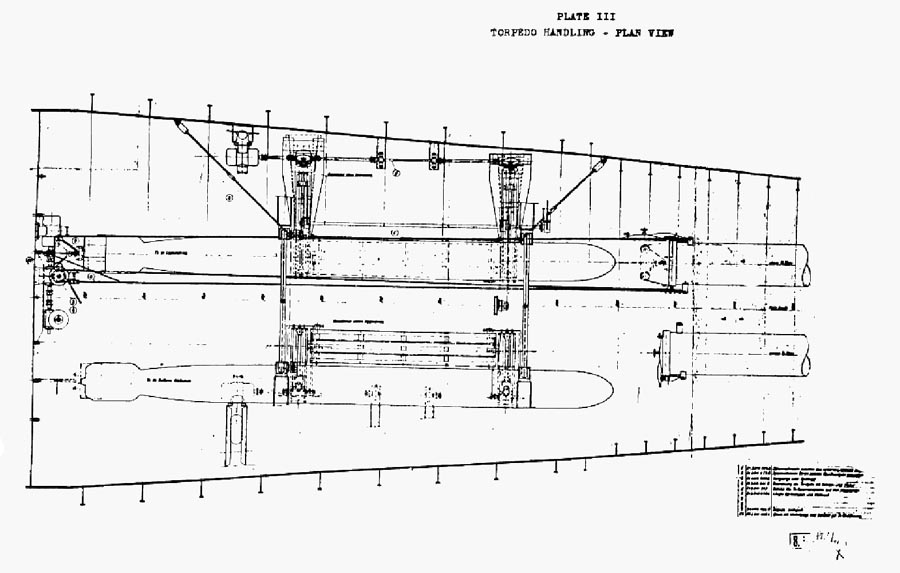

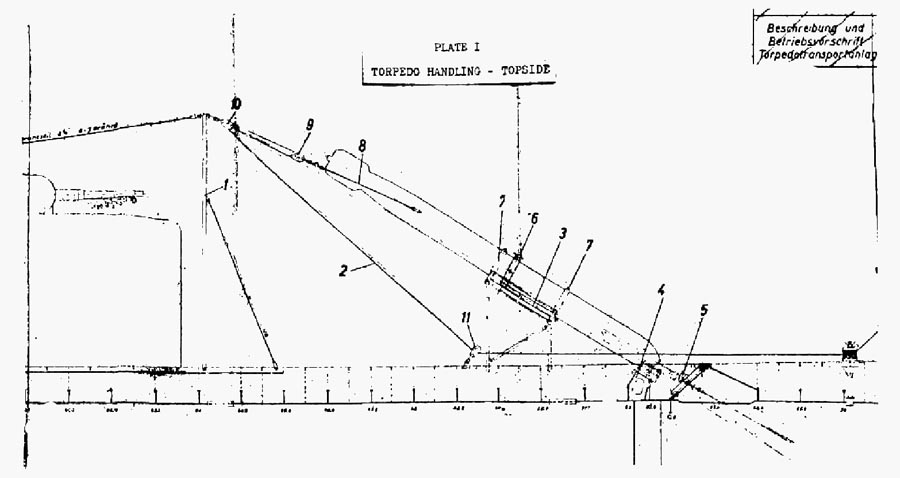

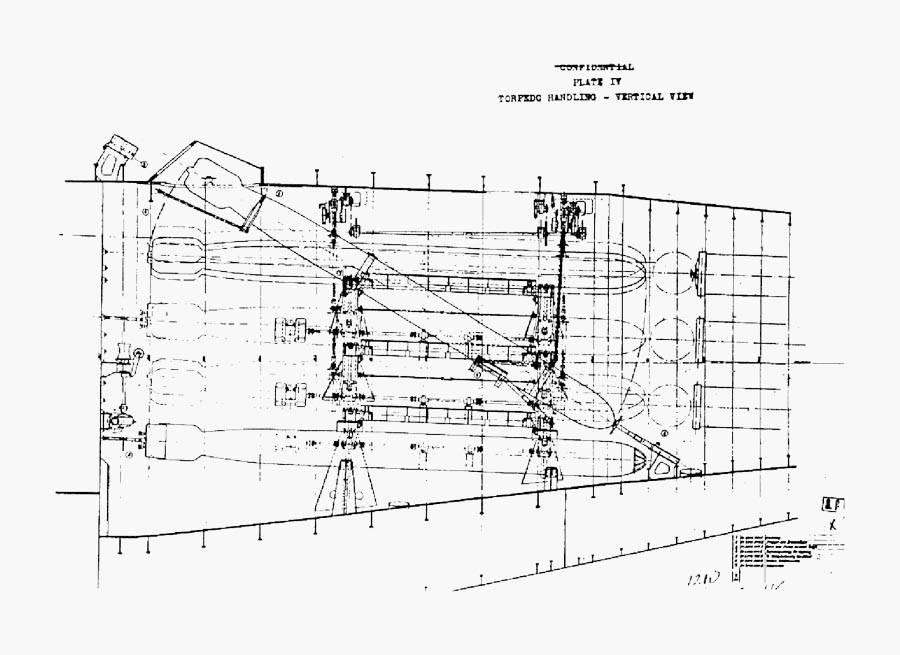

Type XXI Plate III, S75, torpedo reloading slide, cut

the Type XXI was equipped with several torpedo types. The normal ones, which need aiming first:

-The “Lut” or “Fat” which run in a straight-line for a while, then turn repeteadly, sailing in “zig-zag”.

-The “Zaunkönig” was the late acoustic torpedo version or G7e TV, following the propeller noises of the destroyers. These cannot evade it unless they say full-ahead, because this torpedo is a bit slow.

-The improved version T11, also acoustic, following destroyers and ordinary vessels but was faster and cannot be diverted by noise devices.

In practice, the Type G7e was the main supply. As a reminder, this torpedo was provided as the late types G7e(TIV) Falke and G7e(TV) Zaunkönig.

The Falke was the model allowing a sub to fire them while deeply submerged inside the convoy. Their main advantage was to start like a straight-running torpedo for the first 400 m (440 yd) to enable its acoustic sensors, then actively search for a target. Since this equipment was sentitive, the propeller needed to be as quiet as possible, by its shape, and also speed, at only 37 km/h (20 kn), while the Carrier sub was also to be dead silent. This model was mostly intended for merchant targets. its use was limited, as it was merely a “proof of concept” for the acoustic homing torpedo.

The common model however was the G7e(TIII) of 1942, straight-line model capable of 7,500 m (8,200 yd) at 56 km/h (30 kn). It was declined in 1943-44 into the G7e(TIII Fat II), and LuT (Lagenunabhängiger Torpedo), or the G7e(TIII Lut II) all pattern-running systems for convoy attacks. They made their course unpredictable.

Automatic Reloading System

Standard reloading system,external.

As noted in a confidential report dated February 1946 from the Portsmouth naval commission which investigated the Type XXI, REPORT 2G-21, S75-3 was about Torpedo Handling, loading and stowage states the following:

Although several of the design details of the handling, loading and stowage arrangements from earlier German types were retained on the Type XXI, the basic conception, to provide stowage for all torpedoes within the torpedo room with a ready means for servicing the torpedo tubes, was an innovation in German design. The stowage and handling arrangements adopted provide an interesting comparison with present U.S. designs. Several noteworthy features, in particular, the elimination of heavy stowage cradles, warrant consideration for possible inclusion in U.S. designs.

The basic hull design of the Type 21 submarine made it desirable to eliminate the topside stowage existing on the preceding types that were not designed primarily for high submerged speeds. Also as the requirement of a narrow cross section aft eliminated the possibility of after torpedo tubes, it became necessary to provide adequate stowage facilities for all reserve torpedoes in the forward torpedo room.

The German design to obtain this is shown on Plates I-IV. The functioning of this arrangement with torpedoes is fully discussed in the NavTechreport.

A limited number of mines can also be handled with this setup by the addition of the special supporting chocks shown on Plates VI and VII. 18 TMB mines (7.6 ft. long) or 12 TMC mines (11.2 ft. long) could be carried external to the tubes. When carrying mines but a third of the available space is utilized as only the inboard chocks (and cradles) are used. With the present U.S. designs the same cradles that are used for stowage of torpedoes can be used for the stowage of mines; a total of 16 mines (10 ft. long) forward and 12 mines aft are carried in the cradles.

The present German design has proven faulty under depth charge tests in that the elastic bolts securing the supporting arms to the pressure hull have sheared off. This arrangement provided for a total of 20 torpedoes, 6 in the torpedo tubes and 14 in the stowage. Three cradles were left empty so as to permit servicing of the torpedoes in the tubes. No berthing was installed within the torpedo room; adequate facilities for berthing the crew were provided within the large battery compartment.

Noteworthy Arrangement: The basic arrangement providing reserve torpedoes on the same level as the tubes to be serviced with a ready means of athwartship movement of the torpedoes on their supporting members is the same on both U.S. and German designs. The German design utilizes power to move the torpedoes both athwartships on their support arms, and into the tubes longitudinally, while the U.S. designs depend on rollers and hand control for similar transport. The relative advantages and disadvantages of hand control versus power control essentially balance each other.

The main advantage of the Type XXI arrangement lies in the overall weight saving by the use of chocks in lieu of cradles for the support of those torpedoes not lined up with the tubes. The cradles, less rollers, weigh 780 lbs. The chocks used weigh 75 lbs., or 150 lbs. for each torpedo, effecting a saving of 630 lbs. per torpedo.

The conservation of weight by using chocks on rollers in lieu of cradles, and by reducing the number of cradles to one for each layer of tubes, could be easily accomplished on existing U.S. submarines, if desired. This would, at the same time alleviate the awkward handling and stowage problem that now presents itself with a large number of empty cradles. It is to be recognized, however, that in order to carry mines it becomes necessary either to use additional special fittings, as in the case of the German design, or to retain the present stowage cradles.

CONCLUSION: The design adopted for the Type XXI submarine meets the German requirement to provide rapid, silent handling and maximum torpedo stowage facilities within the forward torpedo room. It does this at sacrifice in living accommodations (within this compartment) and overall mine stowage capacity. To properly assess a comparison of this arrangement, it would be necessary to know and discuss the effects that higher submerged speeds would have on the overall arrangement of a similar U.S. design. This is beyond the scope of this report. However, special noteworthy features present interesting studies for possible adaptation to and improvement of present U.S. designs. The lightweight chocks and cradles used are of particular interest. It is recommended that further study be made of an arrangement that uses light chocks in lieu of the present heavy stowage cradles so as to determine what sacrifices, if any, are necessary and what overall benefits are derived from such a change.

The key “pusher barillet” system to hold and distribute torpedoes

Torpedo handling, vertical view.

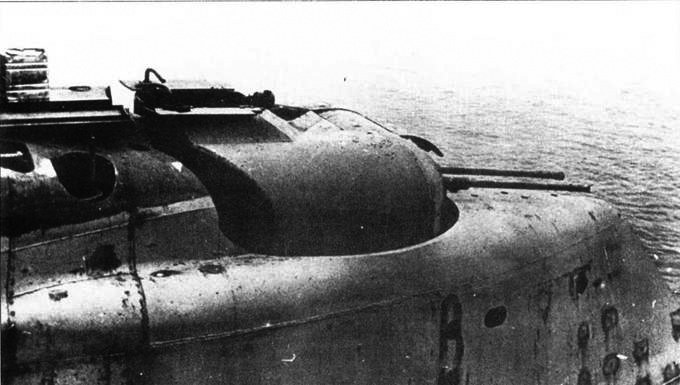

AA Guns

The two tailor-designed turrets house each two 30MM anti-aircraft guns, mounted on each end of the conning tower fairwater. For traverse, elevation and firing, they are controlled by the gunner, obtained by the main hydraulic system, with simple and directional controls. They are not remotelly operated as sometimes seen. The motors were close to small oil pump systems.

Each turret contains two pressure-tight ready service tanks, housing 250 rounds each, plus a gunner seat, with foot controls and related hydraulic gear, hand controls for the elevation and traverse. The 3 cm MK 303 (Br) Flak also called Flakzwilling (M44) was experimental in 1944, designed to replace both the 20 m and 37 mm FLAK, fitted on fixed or wheeled chassis and in specially created mounts for the Type XXI. Manufactured by Krieghoff in 1944, they were 222 delivered in 1944, 190 in 1945.

| ⚙ Krieghoff 3 cm MK 303 (Br) | |

| weight | 185 kg (408 lbs) |

| full lenght | 3.145 m (10 ft 3.8 in)j/td> |

| Barrel length | 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) L/73 |

| Shell | 30×210mm |

| Caliber | 30 mm (1.18 in) |

| Elevation | -10°to ±85° |

| Traverse | 360° |

| Rate of fire | 400 rpm (cyclic) |

| Muzzle velocity | 1100 m/s (3,609 ft/s) M-Schos |

| // HE | 900 m/s (2,953 ft/s) |

| // AP/HE | 950 m/s (3,117 ft/s) |

| Feed system | 15 cartridge clip or belt (Type XXI) |

There is a scuttle in the turret top, from which the gunner’s head protrudes. The forward face is shielded for extra protection, interlocked with the guns, rising when elevates. The turret seats on a ball bearing race, with the carrier ring on the fairwater having an internal toothed ring gear to engage the motorized spur gear. Stops limiting elevation and depression as well as rotation to 170 degrees on each side. When diving, the guns are locked at 5 degrees depression. Construction use the same special steel (Wsho/Mo) as the bridge armor plating, 17MM (0.67 in). It was judged simple enough, although the amount of hydraulic piping is excessive, prone to failure and in act the sole major source of contamination of the whole hydraulic system with salt water aboard.

There was however, as reported in blueprints, a project to replace what was seen as an interim solution, by two pairs of 40 mm guns instead, and that time in full remote operation. Little is known about this arrangement; But it allowed the submarine to fire semi-submerged, or while submerging, or just surfaced without delay, nor risks for the gunner.

View of conning tower fairwater, and turret access.

Sensors & Electronics

Radars

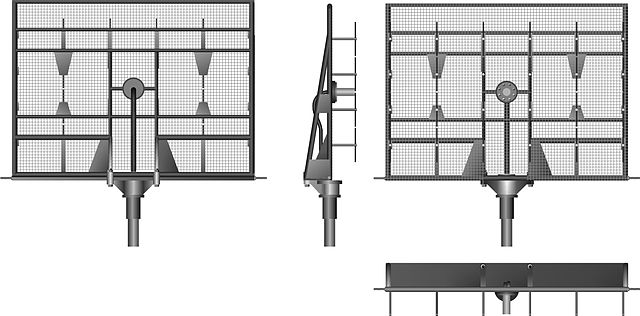

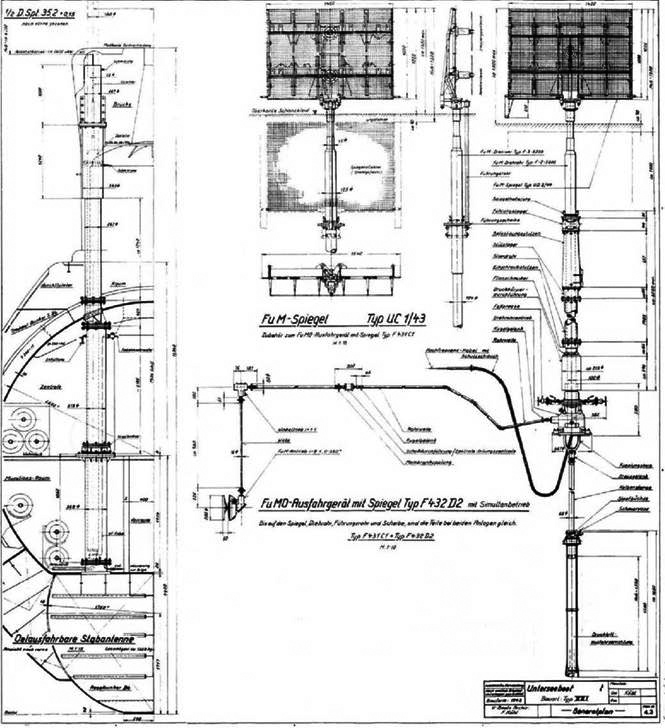

The FuMo 61 Hotenwiel radar and transmitter Type F 432 D2

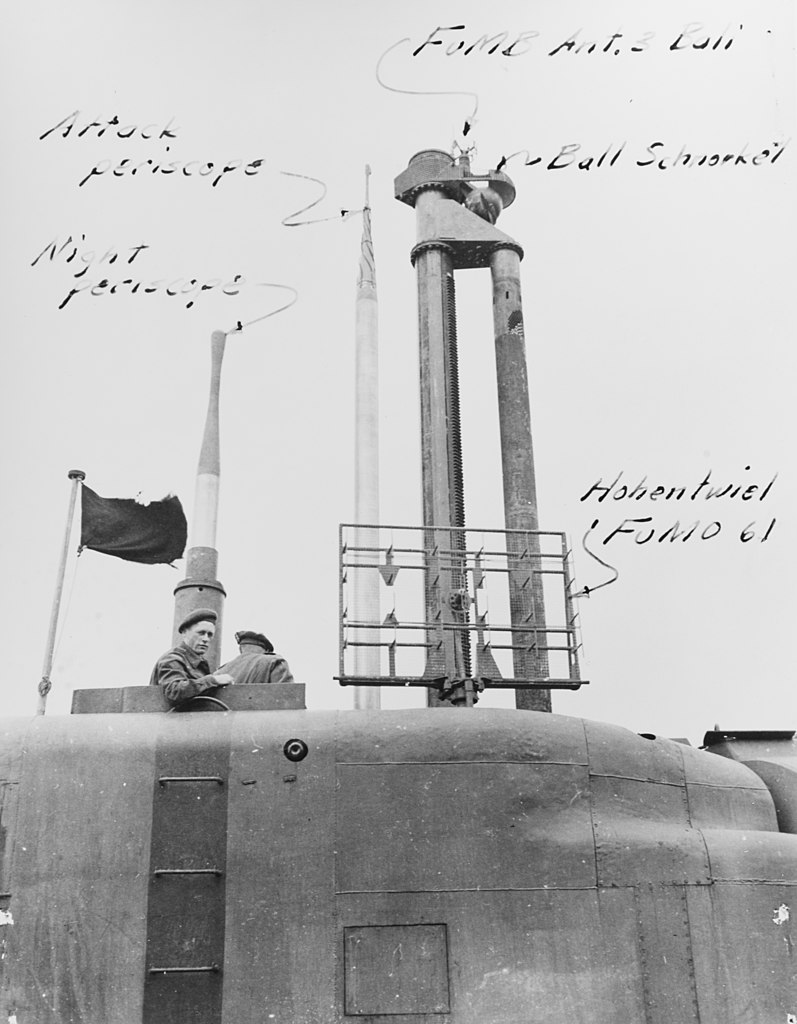

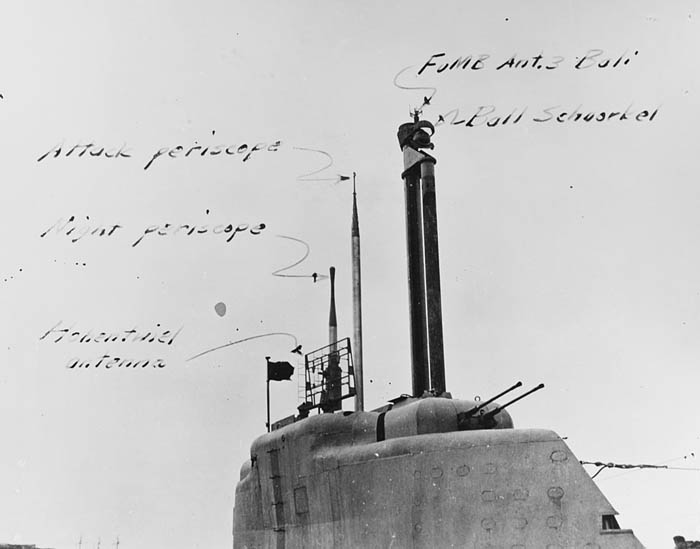

The Type XXI was given a more extensive radar suite than any other submarine before: There were two working parts, the FuMB Ant 3 Ball radar detector coupled with an antenna fitting, and a FuMO 65 Hohentwiel U1 radar with a Type F432 D2 series transmitter device.

The FuMB Ant 3 Bali radar detector and antenna were located on top of the snorkel head. it was a small device, but with extended range, able to catch radar pulse from 50 km? away. Introduced from February 1943, the Biskayakreuz was replaced by the FuMB Ant 3 Bali with worked on the 137-166 cm wavelenghts, mounted on top of the schnorchel mast. A second oscillator was added (FuMB 1) from July 1943 due to the British introducing the 10 cm ASV Mk.III and type 271 radar not detected by Metox. The latter was retired after it was found to be detected by aircraft.

The FuMO 65 Hohentwiel U1 with the Type F432 D2 radar transmitter were installed on the right side of the conning tower fairwater. The latter was a trusted model designed from 1938 and largely used on planes, surface ships and subs. On the latter, its detection range was limited to 10 km, so it was a “last warning” resource. A plane 10 km away could very quickly be on target. Frequency was 525–575 MHz/57.1-52.1 cm (low UHF-band), PRF 50 Hz, pulsewidth 2 μs, azimuth left 30°, middle, right 30°, and power 24V 30A, Synchronous inverter. It was folded inside a “trench” alongside the conning tower roof to protect it when diving.

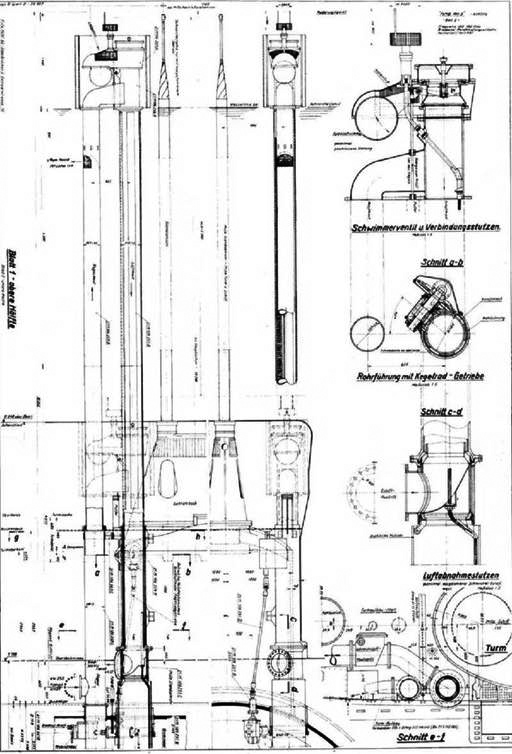

Hohentwiel telescopic Mast detailed blueprint.

Sonars: The Nibelung-Parisfal suite.

U-Boats-prowes-Type21-captured

The passive component of the sonar installation, was the Gruppenhorchgerat (GHG) passive sonar installed in the keel (“Parisfal”), under a protruding cover. This system was not “invented” for the Type XXI but already used from 1942 in some older Types VII/IX. It consisted of two groups of 24 sensor, 12 per side, with tube preamplifier each. 48 low frequency signals were routed to a switching matrix. This allowed the sonar operator to determine the direction of the sound source and relative distance. Switchable crossover ranging from 1 to 6 kHz center frequency improved the reception. There was a dead zone of 40° fore and aft, which was corrected on the “full range” installation on the Type XXI. Its detecation range was 20 km for single shis and up to 100 km for an entire Convoy.

Its active component was the advanced “Unterwasser-Ortungsgerat Nibelung” non-line-of-sight system. To make the fullest use the new rapid loading system and acoustic torpedoes fired from deep below, the Unterwasser-Ortungsgerät NIBELUNG mounted in the bow enabled an approach from deep inside the convoy, emit short active sonar bursts to fix the target location, without being detected. The torpedo room worked in conjunction with the sonar, receiving targeting data, which was inputted into the new Lageunabhangiger Torpedo system.

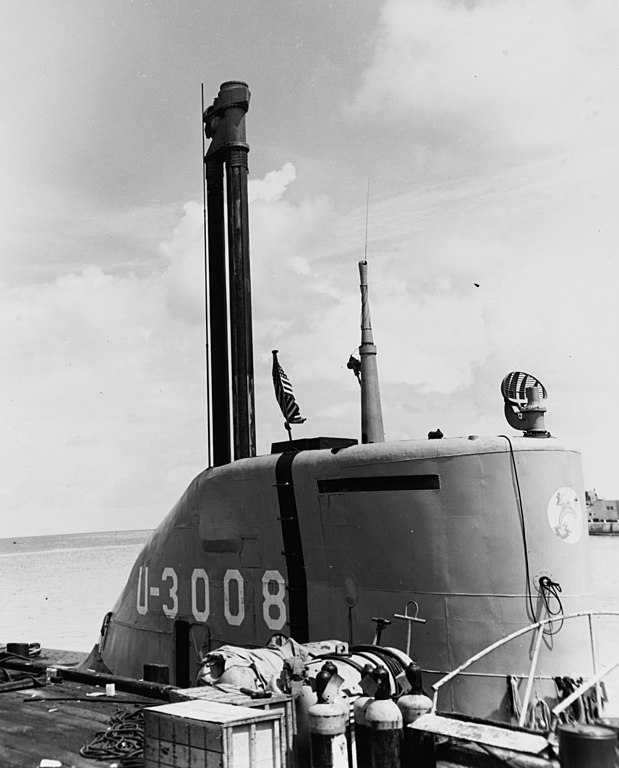

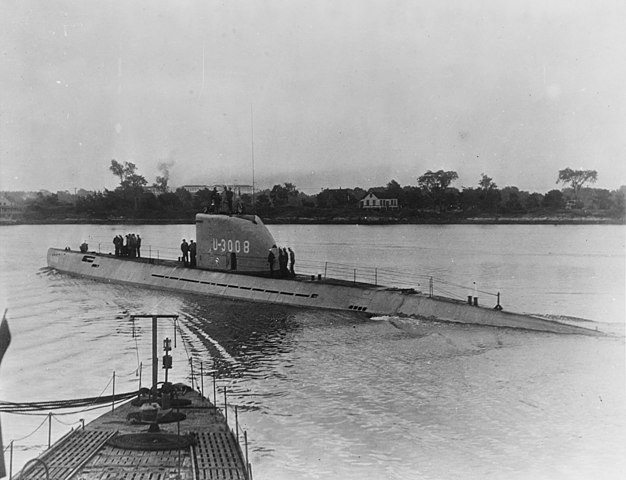

U-3008 Kiosk details

Another innovatove system, the U-Bauer Decoy Ejector, located in the stern compartment. It could sent bubbles and oil to the surface to make think a captain his target has been sunk.

Periscopes

Conning tower design showing the location of the antennae, radars, schnorchel and persicopes.

Along the conning tower fairwater were located the two receiving surface whip antennae, the radio emitter antenna, the main day attack periscope, the smaller night persicope, mosty used for star-based navigation, the main Hohentwiel radar and in front of it, the large schnorchel mast, with the exhaust and air intake tubes, an ball mount admission system. On top of it was located the FuMB Ant 3 Bali radar detector. It seems the periscopes models were less innovative, based on the same models used in earlier Type IX, possibly the type NLSR C/9 day attack periscope. More on their uses and procedures can be found here. The main attack model on the Type XXIII was however the ASR C/6 periscope, with an ocular box of type NLSR C/9 (night periscope and day periscope combined). Possibly the day model was the StaS C/2 attack periscope. The only point to underline here, is that excessive vibrations on the early boats precluded the use of periscopes while under schnorchel’s navigation.

U3008, Hohentwiel and main persicopes. (ONI)

U3008, same, rear view.

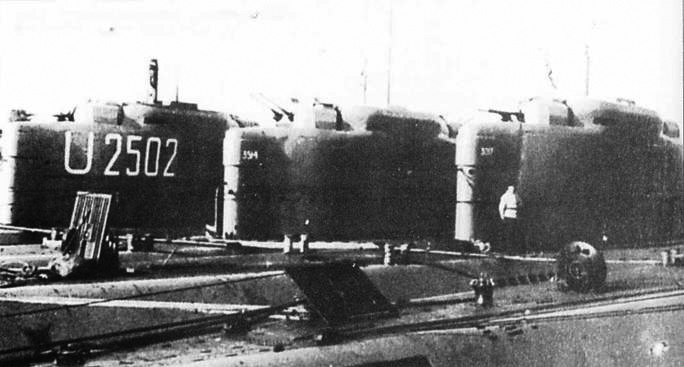

Production: “Like sausages”

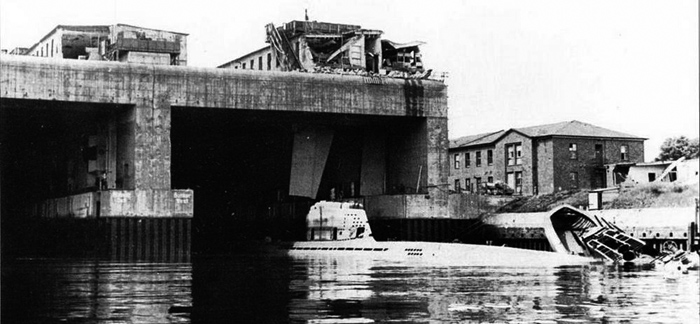

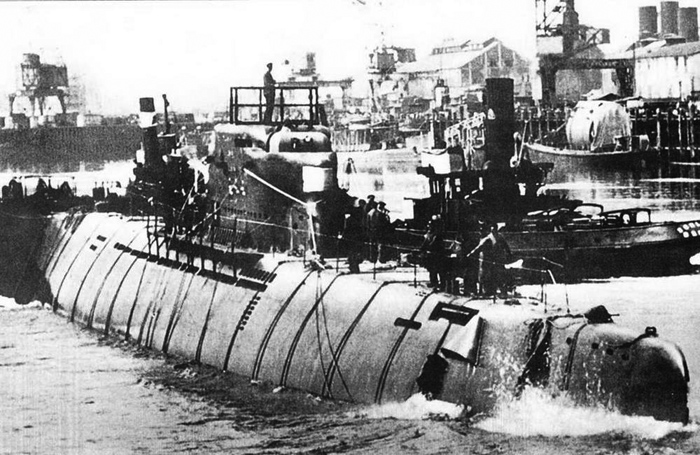

Albert Speer organized mass production with great efficience as agreed in the Summer of 1943, however the first series would be operational in November 1944, not July as first planned, but later. The first had teething issues and commission was delayed. Prefabricated sections were used, that could be built ashore in tunnels, blockhouses, underground sheds, then transported by boat in immense Block-building sites made by Todt for final assembly. The latter, bomb-proof installation were capable of producing hundreds in a month, at the edge of large rivers.

The final assembly was mostly to be carried out in the Valentin submarine pens, a massive and bomb–hardened concrete bunker, built at Farge, near Bremen between 1943 and 1945, using 10,000 concentration camp prisoners and POWs by Todt. It was 90% completed when bombed in March 1945, using the Grand Slam “earthquake” bombs. cracked open, it was abandoned and captured a few weeks after by British troops.

A feat as spectacular as the submarine itself

Crude section

Section in construction, central module.

The mass-construction of the Type XXI at the same path of the American libery-ships, for the most sophisticated submarine ever built was a great accomplishment by German planners at all level, under constant day and night bombings. The total order, in 1945 was to reach 1,170 Type XXI alone, and more than 2,000 Type XXIII, while the entire submarine production until that point in Germany was 1,043. The game changer was a complete reorganization of the production for maximum efficiency, befitting to a “total war”. At last by late 1943 Germany adopted standards of the allies, producing more with less, sparing materials, simplifying, cuttiing work hours, better employing skilled labour, using masses of slave workers in less skilled tasks, but trying not to compromise too much on the technological edge.

The first serious bottleneck was found in the dual requirement for a rapid setup of mass production while maintening the same delivery rate for existing older types, for a 6-months transition. This necessitated indeed the provision of twice as much materials, as well as manufacturing capacity with a network already saturated and stretched to the absolute maximum. At the worst case scenario, the full transition was to be performed over eight months.

Far more materials needed

Prefabricated scheme

Step up the production of U-boat batteries soon appeared paramount, as the new types asked twice more, added to the old types. To achieve this the Armaments Ministry’s had to produce the requisite machinery and equipment for at the expense of current contracts but for aircraft production, which between all arms was given absolute priority. The sheer quantity of lead and rubber needed for them grew acute, but this was later overcome.

The Type XXI also needed very powerful electric motors, outside batteries, that needed to be developed, and the boats were also using many other electrical fittings. This included the cruising motors and trimming plus bilge pumps as well as the new, powerful echo-ranging gear and associated underwater listening station, equally modern and powerful radio and radar sets, search receivers, which at this point focused the attention of the entire German electrical industry, curtailing production of replacement power-stations and locomotives for those destroyed by the bombardments. The population suffered as the result of these shortages.

Another issue was to gather enough high-grade steel plating for the pressure hull. On this particular topic, the Heer was adamant it needed all the capacity to produce larger and better protected tanks: This commodity constituted indeed the worst bottleneck for the German industry as a whole. The allies had the same problems, and in both ship construction and aviation, wood made a comeback. The old type VII still needed these supplies, and the new types, larger, required more. But the autumn of 1943, the output needed was 3.5 times greater as what was allocated until then. Soon, the Kriegsmarine had to make choices, like cancelling all surface vessel production, stopping ongoing contructions (like the many times postponed Graf Zeppelin, cancelled for good), and even warships repair was cancelled or further prioritized (like the Tirpitz). Shaping ready rolled pressure-hull sections was also a challenge.

At this point, the Gamble of the Type XXI was a nightmarish one, especially for one man, the director of the Central Shipbuilding Committee, Herr Merker. There was indeed a Considerable risk involved in mass-producing this new U-boat without trials or standard development phase. Failure was not an option as the prodigious efforts needed would have been in vain, especially of up to 200 new U-boats were to be scrapped in the end. This was double risk as developed alongside an unprecedented level of prefabrication with mass-production methods never used in shipbuilding before in Germany. And if this was not complicated enough, wartime conditions took their toll in a semi-predictable way all along. If a major supplied was destroyed, the whole supply chain was too, triggerring massive delays in delivering an intested type that was badly needed to reverse the situation at sea.

In fact many experts of the time were worried that completing the task as early as possible was an unsurmountable task overall, but this does not prevented a firm order for 360 Type XXI and 118 Type XXIII to be passed, added to a Mediterranean ports extra order for 90 supplementary Type XXIII. New specialized, smaller and simpler types of both were also studied for future production in 1945. The Type XXI/XXIII production was to create a basis for future developments, testing the waters.

More delays before and after commission

Even if Boats were completed on time, having crews trained on board, on such brand new boats, was not as simple as it seems. A ship and its crew needed to work like a tightly, well oiled man-machine clock. No procedure was ever done for all new systems designs, and documentation was provided along the way. With the initial production delays showed above, the whole new U-boat building programme dropped five months behind schedule. And meanwhile, crews needed to be assembled and trained on boats that were still unfinished.

The first or these U-Boats was launched as scheduled in April 1944, but needed a lot of extra work to fix its multiple issues, that would have been normally avoided if sections has been perfect. So it’s onli by June 1944 she was officially commissioned. The start was slow but after December 1944 it was believed that a rate of 20 Type XXI would be completed monthly, meaning finding and training 57 men each time (so 1140 monthly) was not easy. Shortcuts were found, as captains, usually taking command during completion, visited the boats from time to time, but mostly trained in dedicated building, on sub-sytems when available, trying to reproduce a semblancy of working environment with limited means.

Even when the crew entered the boats, after commission, actually starting proper training, at leat on the first seven boats, frequent interruptions for repair and modifications allowed the initial crew to train in not three months as it was usual, but six. Constant reporting along the way and close co-operation between the Construction Office (Blankenburg) and U-boat Acceptance Staff, plus the U-boat Training office eliminated all most serious defects in a few months. By the autumn of 1944, all these informations has been passed onto the while construction chain and incorporated into newly-built boats; The normal crew of a Type XXI consisted in fifty men and seven officers. To compare, a larger Type IX was about the same, about 56. But with a much tighter space and far worse living conditions.

⚙ Type XXI class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 76.20 x 8 x 6.32 m (252 x 26 x 21 feets) |

| Displacement | 1,621 tons standard, 1,819 tons Fully Loaded, submerged |

| Crew | 57 (5 officers, 52 sailors) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts MAN M6V40/46KBB supercharged 6-cyl. diesels 4,000 PS 2 SSW GU365/30 double-acting electric motors (4,900 shp) 2 SSW GV232/28 silent running electric motors (223 shp) |

| Speed | 15.6/17.2 knots (29/32 km/h) or 6.1 kts silent running. |

| Range | 15,500 nmi/10 knots surfaced, 340 nmi/5 knots submerged. |

| Armament | 6×53.3 cm (21 in) TTs bow, 4×2 cm C/30 FLAK turrets |

| Max test depth | 240 m (787 feets), estimated crush depth +300m |

The Type XXI in action

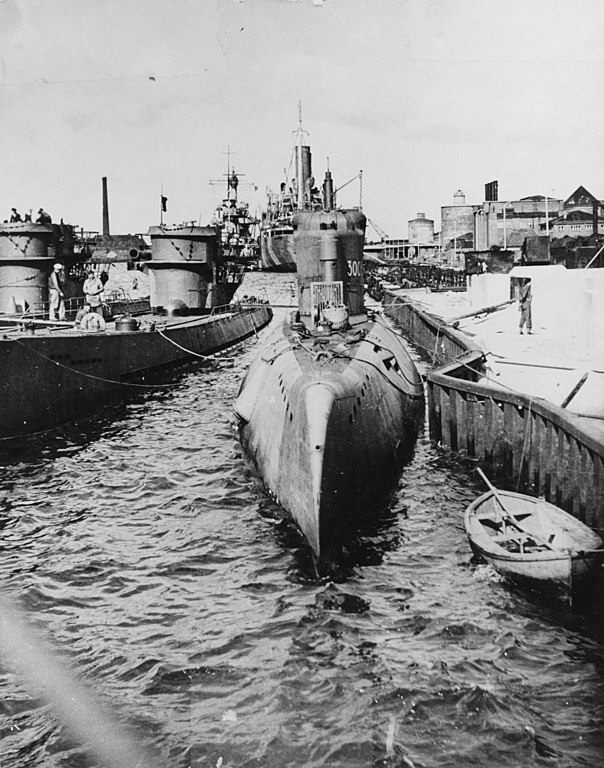

Ed Tambunan colorized photo of the surrendered U-3034, May 1945. Note the yellow markings.

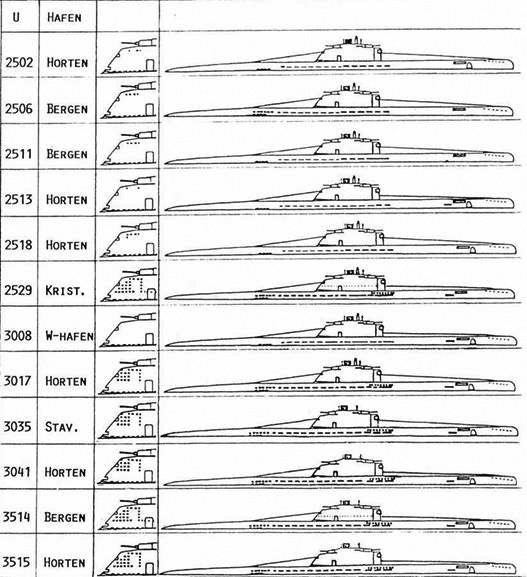

In early 1945, the Allies were prepared to strike Germany from the South, East and West. The ports in France had to be abandoned and the ships were withdrawn to German, Danish and Norwegian ports. The training divisions had to abandon their training places in the Baltic one by one: Pillau, Danzig, Gotenhafen… But despite of that, they went on with the trainings with the new vessels —now that they were launched in droves— hoping to fight until the last moments.

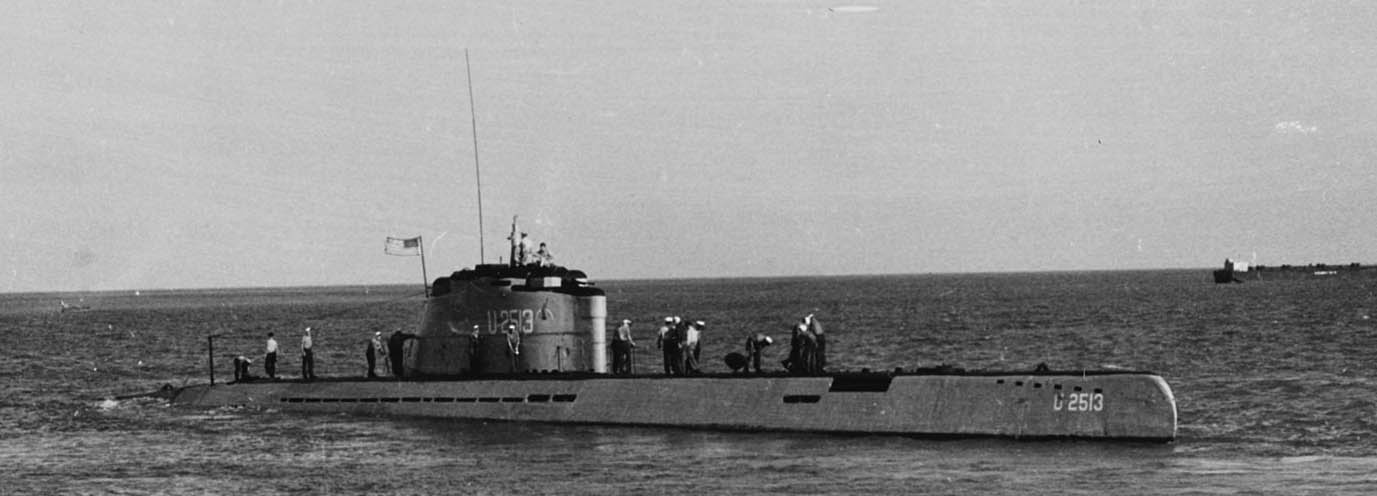

In the last days of April 1945, U-2511 sailed from Bergen, Norway. She went away from her sisters and gained speed as for the first time, a Type XXI would face the enemy. Men on board were already well trained and knew that they could trust her to sail fast and be kept submerged for a long time. Within days she would fight the enemy, show that all the expectations on her were right. She was commanded also by an ace, Korvettenkapitän Schnee, U-boat veteran with 200,000 tons sunken in seventeen engagements and since her had worked for the Naval Construction Commission, perfectly in tune with the Type XXI and its capabilities…

Two sorties and a controversy

Crew of U-3016 in 1945

U-2511 and U-3008 were in fact the only Type XXIs used for operational war patrols, in actual combat. … but neither sank any ship. The first’s commander claimed to have spotted a British cruiser on 4 May 1945, just when news of the German cease-fire was received and that he made a successful mock attack before leaving the scene undetected. U-2511 trained in the 31st U-boat Flotilla from 29 September 1944 to 14 March 1945 and then the only active 11th U-boat Flotilla from 15 March to 8 May 1945 under command of Captain Adalbert Schnee, making her first an last patrol on 3–6 May 1945.

However postwar analysis had completely disclaimed Schnee’s accounts as dodgy at best. It happened that already during his ten combat patrols on U-60 and U-201 he overclaimed 50% of this kills. According to cross postwar records, he did not departed on 30th april, but 3rd of May 1945 from Bergen, could not spot HMS Norfolk escorted by destroyers, as there were none, could not spot the cruiser again on 5 May off Beegrn as he was there on the 6th, and at that time, HMS Norfolk was NW of the Shetlands, bound for Scapa. He also claimed to have been taken onboard the cruiser for interrogation, which was just straight out impossile as the sub did not surrendered before the 9th, and no record of his interrogation as noted in the cruiser’s logs. Also his “eye witness”, war correspondent Wolfgang Frank was not aboard when Schnee made his “mock attack”.

Later in 1988 the investigating Gröner group was joined by Dr. Niestlé, could not find U-2511 log,s but had the one from Norfolk, and now declassified Ultra decripts pointing aout the position of U-2511, interviewed eye witnesses, and it appeared his boats hat day at 8:00 on the 5th was 110 miles south of Norfolk. He did not evaded a Corvette on the 4th allegedly, as she was too far away to the west, nor Norfolk, too far north from U-2511.

On her side, U-3008 left Wilhelmshaven for her first and also last patrol on 3 May 1945, but returned to port after the surrender. On 21 June 1945, she was seized by the Allies in Wilhelmshaven, and sent to Loch Ryan. From there, she was transferred to the United States and reached New London in Connecticut, on 22 August (see later US evaluation).

All in all, for 121 boats “commissioned” before V-Day, only about half were ever operational, making a few sorties after a training period. The very first boats completed wee riddled with problems and only fully operational by the mid-1945. Apart two active war patrols, the others performed short semi-operational training cruises. There were losses, even though no ship was ever sunk, traducing the extreme state of affait for the Kriegsmarine that late into the war: U-2503, 2509, 2514, 2515 and 2516, U-2521, 2523, 2524, 2530, 2532, 2534, 2537, 2542, 3003, 3007, 3028, 3030, 3032, 3505, 3508, 3512, 3519, 3520 and 3523 were all lost, between enemy action (in the most cases, not ASW action but rather air attacks, including in ports) and other due to accidents. In fact the attrition rate was revealing in the production rush and problems with the whole concept. The remainder surrendered or were scuttled.

General assessment: Debunking the “wunderwaffe”

cutaway_Type_XXI

Reality’s ugly head postwar basically destroyed the optimistic views/outright propaganda about the initial capabilities of the Type XXI, and it’s postwar myth of “super weapon”. It might be argued that Dönitz was eager to have his project prioritized towards Hitler and stated paper specs that were very tasty but far fetched indeed. The problem is that they were taken as such and publicized in some general public books and, notably in History Channel’s “Nazi Megastructures: Hitler’s Killer Subs”. In this documentary many claims were made.

The latter indeed was supposed to be quieter and diving much deeper than any other sub that came before.

Her top speed was 17 knots based on 5,000 shp.

With her reloading system she had the potential to sink 18 ships in 20 minutes.

Her diesels could reload her batteries in just one hour

Despite a much larger hull, the streamlining meant her acoustic signature was much smaller

The schnorchel was ingenious, allowing her to stay underwater even in rough weather

Her sophisticated echo chamber could identify, track and target multiple targets at once, so she could blindly fight from 160 feet deep.

US evaluation post-war showed the batteries could be recharged, based on far lower output, in four hours, not one. The point on top speed, 17 kts submerged was debunked in several ways. First off, she was designed to dive fast, in 20 secs. as specified. Second, as she was given for this many freeing ports, these added 28% to her drag. During a submerged run on 8th Nov. 1944 U-3506 achieved only 15.93 kts. This was compounded by British own tests, which doubted that 15 kts could be achieved, even with a one hour run. This was also confirmed by a German war log in 1-15 January, confirming 15 knots was achieved.

Also, test bed results for the two main electric motors only achieved 1800 Kw or 2413 hp, which, with fully loaded batteries, could be maintained for just an hour, not 4-5 as stated. Others stats showed 15 kts could ebe achieved at max power for just 50 minutes. It appeared also that to house the many new batteries, German engineers’s newly developed, lightweight diesels were rated at 1970 bhp and each were given superchargers driven by exhaust gas (turbo).

However it appeared in US tests that these diesels were very weak. On trials they were limited to 1700 bhp due to overheated exhaust gas, and proving hazardous when snorkeling so deactivated, which further crippled the boat’s speed on surface. Without the superchargers, their output fell to just 850 bhp, making for 12 kts on surface, but on paper only, as the British found the boats were “ploughing” and the deck was constantly flooded, creating massive drag, so it fell to 10 kts and below in practice. For loading the batteries, US tests shown this was even worse, with superchargers deactivated, and that 6 hours were necessary at max capacity.

It appeared also the “all-weather” Snorkel was not an innovation of the Type XXI but in reality was found also on the late Type VII and IX as well. What was unique however, was the Type XXI telecopic mast, but it never worked properly: Only 10.9 kts could be achieved due to eddy shedding from the mast and periscope, thus severe vibration reducing in practive top speed to just 6 knots. The British downwards hated this ‘snot head’.

For torpedo stowage, the US reported that idle positions forced a practical stowage of 20, not 23 torpedoes. The British found that if carrying 14 reload torpedoes, six were to be accomodated in the automatic reload system and these needed a classic loading, which took far more time, just as a Type VII/IX. The idea that 18 ships could be dealt with in 20 minites is therefore just ludicrous. There was also the fact the Type XXI was supposed to carry four types of torpedoes, the G7e, and others, making impossible to fire the same way 18 torpedoes.

As per the “deeper diving”, it was not that stellar: As designed, 135 m was the safe depth, 200 the test one and 330 (1073 ft) the crush one. However, when a design defect was found on the torpedo hatch during a 16 March 1945 test dive, a fix was needed, which was successful on 8th May 1945, far too late for operations. Numerous manufacturing defects were also found by the allies which restricted their operatoinal depth to 108 m (350 feets), barely better than for a Type VII (102 m/330 ft) and a test depth at 160m/520 ft. A far cry to the 280 m (919 ft) claimed in the documentary.

About the alleged acoustic stealthiness, passive sonars were not a thing in WW2, as active ones (ASDIC SONAR) were used instead, pinging the hull, which, streamlined or not, bounced back the signal. According to British reports the Type XXI had a larger, deeper hull, presenting even a larger surface on which to ping than a regular Type VII: She was less stealthy. As for the noise, even at 8-9 kts underwater she was established as noiser than a Type VII even running at 3-4 kts ! (Malcolm Llewellyn-Jones).

As for the 260 tonnes of batteries supposed to propelled the sub underwater for 11 days, allied tests deflated this to just less than seven. It was still far better than a Type VII/IX, but still the sole point that stands out. However this was done at great risks. Indeed, postwar British evaluation pointed that after their U-3017 tested in August suffered a battery explosion that crippled her, their enquiry suggested that German practice had caused a number of explosions, possibly not initially taken as loss causes. This was coumpounded by four wartime German engineers reports. Also, it was observed that the electic cables running under the battery compartment were poorly insulated, and water wfrequently seeped in the bilges, causing shorts, arcing, combined with poor ventilation and hydrogen emanations during the charge. Perfect recipe for a catastrophy.

Another innovation point was also debunked: The use of hydraulic power to spare electrical motors, used in fact for the preiscope hoist, bow/stern plates, rudder, TT doors, torpedo reloading and other sub-systems. Toroughly examined by the US and Britsh engineers, the system appeared to have been improperly designed, was over-complicated and too fragile overall for combat operations. The piping and fittings were at the mercy of manufacturing quality and were not made leakproof. Seawater as a result contaminated the network on a daily basis.

A conclusion: A Game changer ?

U 2501 in May 1945, in front of the Elbe 2 bunker with submarines pens near the Hamburg shipyard in Gowaldt. This boat arrived in March-April 1945 while the bunker was built for the final assembly and repair of the Type XXI. The only officer on board was Oberleutnant Engineer Noak, ordering its scuttling. It was flooded at 7 AM, May 3, 1945, before leaving.

The Type XXI sure had qualities, but they needed all more time to be ironed out, to achieve their true potential. The whole program was rushed in such a way it spelled disaster. But outside this, how this boat could be used tactically ? Where these old tactics were still applicable ? – It appeared that first off, the Type XXI actual performances were not ideal for the usual tactic of moving faster than the convoys. Six knots while snorkeling, or 15 kts for 50 min. were not sufficient for this. Daylight attacks were impossible, and only nigh attacks could have been planned, just like the old Type VII.

As for communications, this was possible for the Type VII to report a location and course to the others in the wolfpack, by radio for coordinated attacks, but it was impossible for submerged Type XXIs. Another set of tactic was then need to reach the potential of this new submarine.

The German HQ knew about this, and planned for these “Wunderwaffe” individual “free for all” operations, like in the early days of sub warfare. Operations in shallow waters was ruled out, and only oceanic ones were possible with that kind of boat, with the understood limitations of the absence of direct route after the loss of the French and Dutch coast. When captured and interrogated, officers stated that indeed, they had received no operational tactics or even a coherent concept of operations. At first, they operated alone, but wanted a return to the pack tactics, perhaps using the new “burst” radio tranmitter.