Northampton class heavy cruisers (1929)

USA (1928-30) – USS Northampton, Augusta, Chicago, Houston, Chester, Louisville

USA (1928-30) – USS Northampton, Augusta, Chicago, Houston, Chester, Louisville

Back to the drawing board

Basically engineers used the previous Pensacola class to start over on a more stable, more balanced and roomier design with better seaworthiness by adding a forecastle and choosing three triple turrets. The basic design became standard for US conventional cruisers ever since, repeated on the New Orleans, USS Wichita, the Baltimore and Salem classes, even the Alaska, and mirorring the configuration of modern USN Battleships. The “poor child” of the design was still armour protection, and this cost three cruisers during WW2, half of the class.

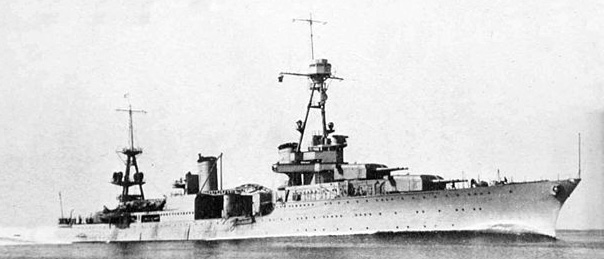

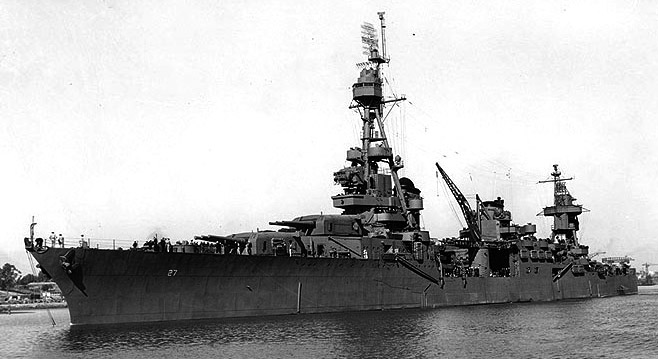

USS Northampton 1930

Succeeding to the Pensacola class, the six Northampton improved on many points. The early stability problems were still an issue for engineers, but the forecastle partly cure some of these as the better balanced choice of three triple turrets. However speed and firepower remained the priority over protection and they were still of this 1st generation “tin-clad” treaty ships. The six cruisers were built at Newport News and New York; actively participating in the Pacific campaign: Houston, Northampton and Chicago were sunk at Guadalcanal, Chester heavily damaged, and Louisville, damaged but surviving the onslaught… Only USS Augusta had a more “cushy” assignation on the other hemisphere, the only ship out of the six 1st generation treaty cruisers not to take part in the full pacific campaign, after being flagship of the Asiatic fleet for seven years, until 1939.

USS Northampton August 1935

Design context

No need to dwelve in detail in the years preceding the concept of heavy cruiser as defined in the US Navy and the design evolution taken from 1922 to 1925. Ket just say that the six Northampton class (at the time still unnamed) were authorized by the congress in December 125 FY1925, eight heavy cruisers, among which the first two were the Pensacolas. They were started one year earlier to give time to engineers to perfect the initial chosen design and solve probable issues.

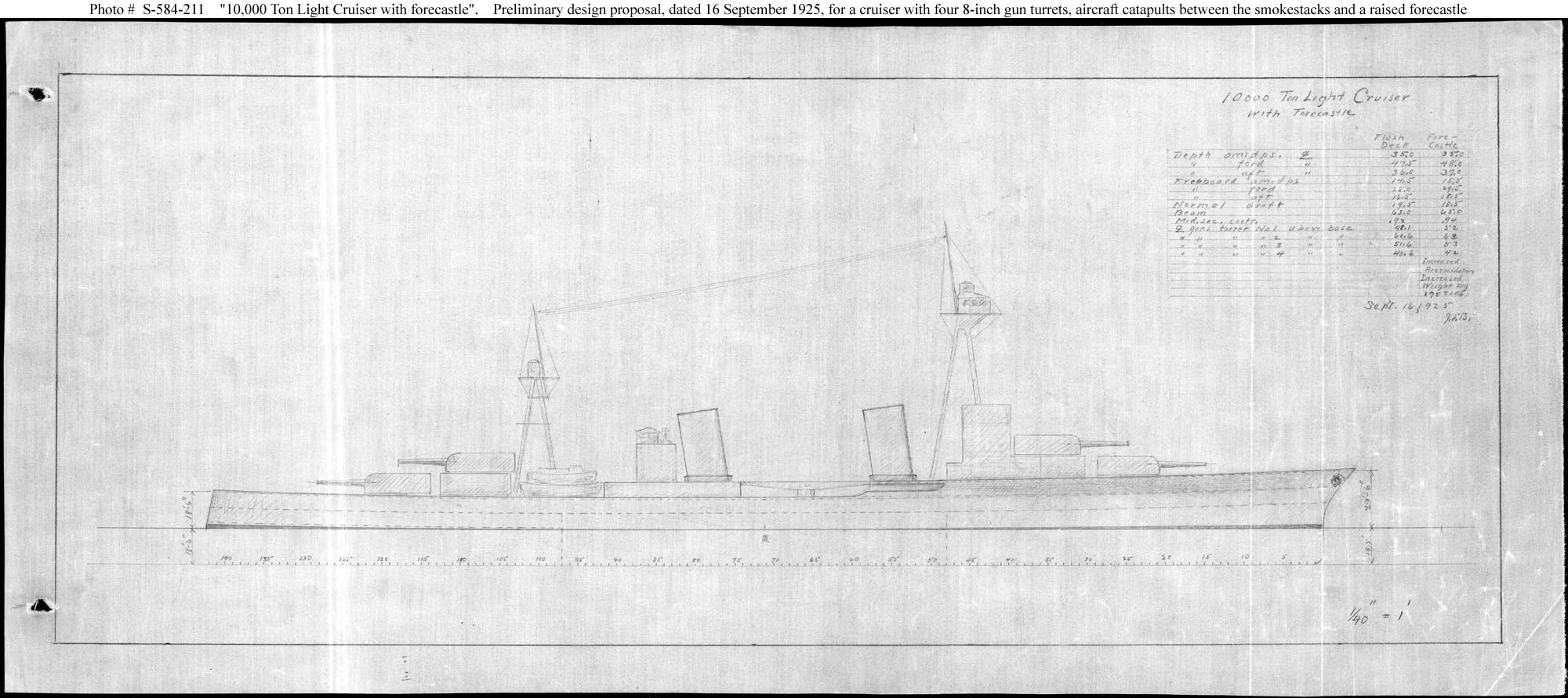

September 1925 Raised forecastle design variant, 10,000 tons treaty cruiser

The key moment was the design of the second class authorized by Congress, improved in the sense within C&R where discussions took place between engineers, the Pensacola design sacrificed too much to firepower, to the delight of the admiralty board. The treaty not giving any room for improvement withing the tonnage, a team was charged in 1924 to better balance firepower and seagoing characteristics. Reducing the armament to nine guns in triple turrets “robbed” the admiralty of a key advantage, but it was still one more than standard French and British designs of the time, which had eight, the famous standard ‘8-8’. The triple turret had multiple advantages, which combined handily with a second innovation that only appeared later, the forecastle. The triple turret arrangement allowed the citadel portion of the ship to be shorter, helping to improve protection by potentially slightly increasing armor thickness, and allowing to better balance the “plowing effect” of the bow, eliminated completely.

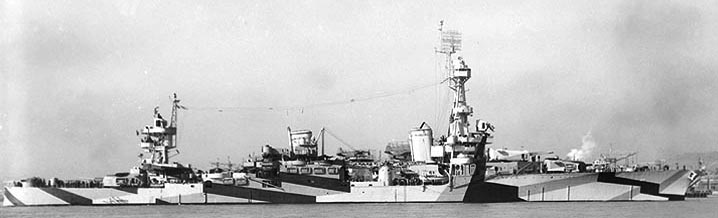

Houston and Augusta fitting out at Newport News 1st February 1930.

As they were designed in 1925, it recoignised asl that aircraft arrangements on the Pensacola were not entirely satisfactory and next year, funds were allocated for three new improved cruisers with an order to massively improve on habitability. Volume studies showed the forecastle and slighty larger beam would had the shps gaining 15% more room per crewman. The choice of bunks rather than hammocks to gain more space was not luxury: The way the Omaha and Clemson/Gleaves were designed, the ship were very wet, always damp inside, with poor accomodations, while the Pensacolas were following the same path. As a result, the Navy suffered from a high rate of desertion, and poor reenlistment rate. USS Chester (CA 27) was the first launched, on July 3, 1927. The ships were fitted out at Mare Island Arsenal under supervision of Naval constructor Charles W. Fisher Jr.

Final Design of the Northampton class

USS Houston 1935

USS Augusta in 1945, note the evolution, almost completely new animals

The design stayed under the cap of the Washington Naval Treaty, of course, but this time, engineers were stil ask to keep a comfortable margin towards the limit of 10,000 tons standard displacement: They reached 9050 tons standard, with an estimated 11,500 tons fully loaded. This left about 9000 tons of useful payload, either additional protection, AA, ASW bulges, ect. The main battery was the fist change, swapping on three turrets as seen above, and they were a reaction overall to the problems of the previous class. Armor was not increased significantly increased, but the layout of the belt was extended. They turned out to be lighter in fact than the Pensacolas. Forward freeboard and seekeping were greatly improved by adopting a high forecastle, even was extended aft for the last three ships, used as flagships.

The first U.S. ships to adopt a hangar for aircraft they still appear lighter than expected, and at sea, showed again some excessive rolling. Like the Pensacolas, they had to return soon in drydock for the fitting of deep bilge keels, with only partially resolved the matter. More measures were taken over time, like the removal of the torpedo tubes, the superstructures was lightened, the aft mast replaced by a pole, and for the survivors after 1942, in some cases the entire tripod was replaced by a lower model and the bridge superstructure curtailed again.

Close view of the Bridge, goodwill visit to Brisbane, December 1941.

Same, but details of the side, aft superstructure

Hull & Protection

Northampton in fitting out

Compared to the previous Pensacola, the Northampton hull was 582 ft (177 m) shorter at the waterline, but longer than the Pensacolas at 600 ft (180 m) oa versus 585 ft 6 in, due to the adoption of a forecastle which elongated the bow. This forecastle one hand added extra weight forward and above the waterline, but resolved the “plowing” problem of the previous ships by having a greater freeboard and buoyancy forward. Their seakeeping was therefore crucially enhanced. Also, construction still called for welding, lighter than rivering, and was stighly less costly. They were beamier too, with 66 ft 1 in (20.14 m) versus 65.0 ft (19.8 m) on the Pensacolas, so about one foot more, also improving stability. Superior buoyancy meant also a lesse draught, 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m) versus 19.5 ft (5.9 m) on the Northamptons.

Protection-wise, the armor scheme was still able to deal with destroyer rounds (5-inches) and at better angles, light cruiser rounds (6-in) while themselves still be of the “tin clad” catergory: In all armoured protection represented 1057 tons of HTS steel :

- 3″ (76mm) machinery belt

- 3.75″ (95mm) magazine belt

- 1″ (25mm) machinery bulkheads

- 2.5″ (64mm) magazine bulkheads

- 1″ (25mm) machinery armor deck

- 2″ (51mm) magazine armor deck

- 1.5″ (38mm) barbettes

- 2.5″/2″/1″/0.75″ (64mm/51mm/25mm/19mm) turret faces/roofs/sides/rears

- 1.25″ (38mm) conning tower

Powerplant

No great change either, in that they were powered by four shaft Parsons with reduction gear steam turbine which developed 107,000 shp, so about the same figure as on the Pensacolas. Steam came from eight White-Forster boilers, and top was the same, 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) as contracted. On trials, they slightly exceeded these figures, and in general better coped with heavy weather, at least in rocking. The rolling motion was still bad for gunnery, but the addition of deep bilge keels and counterkeels reduced it sensibly. Te general light construction forbade broadside fire or even simultaneous fire from a single turret.

USS Chicago off New York City 31 May 1934

Armament

This was the repeat of the previous ships, with the difference of three triple turret later adopted by all other heavy cruisers designes until the Salem class in 1946 which was more than twice her displacement…

Main Guns

Nine 8 in (203 mm)/55 caliber guns (3×3). These were the 8″/55 Mark 10 type.

Rate of fire 3 rpm

260 Ibs (118 kg), AP, SP, HC and HE shells.

Muzzle velocity 2,800 fps (853 mps)

Barrel life 715 rounds.

Range 30,000 yards (27,430 m)

Penetration 4.0″ (102 mm) up to 10.0″ (254 mm).

Still “triple mounts” types and not turrets with their handling rooms directly below the gunhouse, rotating stalk and solidary barrels without independent elevation. Rather high dispersion pattern due to the proximity of the barrels, that the slight lap did not improved much. See also: http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_8-55_mk9.php

Northampton 1941. The four 5-in/25 are shown on top of the hangar and abaft the aft radio room.

Secondary Guns

As on the Pensacol it consiosted of eight single mount, unprotected 5 in (127 mm)/25 caliber dual pupose anti-ship/anti-aircraft guns. These were the 5″/25 Mark 10 model.

Speed: 15-20 rounds per minute

Provision 200 HE, AP, AAC and VT AAC, illumination shells per gun.

Barrel life circa 3,000 rounds

Ceiling/range 27,400 feet (8,352 m)/14,500 yards (13,259 m).

Like the Pensacolas, they were located in individual semi-sponsons on the upper deck of the forward bridge battery superstructure, abaft the aft funnel. See more: http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_5-25_mk10.php.

AA Guns

USS Northampton AA attacks, 1.1-in off Wake Feb. 1942

Four single 3″/50 AA guns, which can double as salute guns. This standard type was also present on many USN ships, from destroyers to submarines and cruisers.

Four quadruple 1.1″/75 AA guns, the famous 28 mm “Chicago Piano”, fitted from 1935.

Eight single 0.50 machine guns, the trusted M2HB Browning. All three provided the AA at Pearl Harbor.

Refits changed these:

-In 1942, the Browning were all replaced by fourteen (14) 20mm Oerlikon AA guns.

-In Early 1943, The 1.1″ guns are replaced with the same numbers of 40mm Bofors AA guns.

-In 1944-45, the surviving ships received in some cases two additional twin 40 mm AA Bofors and up to thirty-one 20mm Oerlikon guns, with differences between ships.

USS Chicago at Mare Island 1931, close view of the aft platform tripod AA guns and fire director, projectors.

Torpedoes

Like the Pensacola class, the Northamptons received two triple 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes banks, installed in recesses in the aft superstructure. They were eliminated in 1940 already, a good decision given the mediocre qualities of US torpedoes until 1942. The recesses were plated over.

Aft view of USS Houston’s tripod, 1938

Air group

Vought O3U-1 Corsairs, catapulted and on board in gready use, two on catapults, two in reserve. When not launched in combat, it was preferrable not to have exposed externally: Due to shrapnels, they could spray high octane aviation gazoline on the decks.

As for the Pensacolas, they entered service with the Vought O2U Corsair (1928).

-Next, they were provided the Curtiss SOC Seagull (1934) Until 1943 (illustration).

-Vought Kingfisher were embarked for the survivors of Guadalcanal in 1943, until decommission.

Their main advantage over the Pensacolas was their hangars, wide enough to acommodate four aircraft, ensuring their protection and good maintenance over time. The latter were used for reconnaissance, liaison, and long range artillery spotting;

Fire control systems

Same fire control systems and localization as for the Pensacola: The main Mark 18 fire director was mounted atop the main mast. Secondary fire director installed on the bridge roof for the 5-in guns. Two telemeters installed on the radio room for the torpedo tubes. The cruisers also had four main projectors for night combat and two light morse projectors. Radars were installed from 1942:

-CXAM1 Mark 3 and Mark 4 radars. For the survivors in 1943, the CXAM1 was retired and the SG, SK, and SP radars are fitted, until the end of the war.

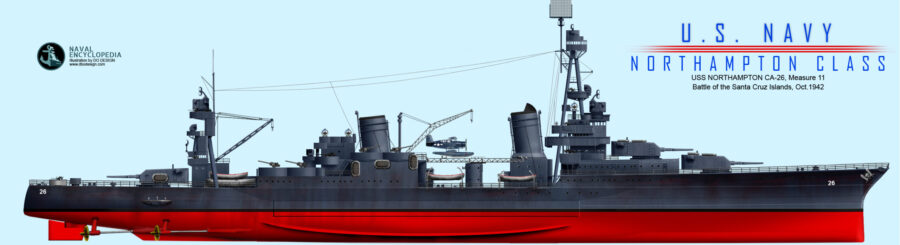

Profiles

The USS Houston in March 1942, with a “navy blue” livery, not yet widespread (Author’s profile).

USS Northampton, measure 11, Santa Cruz Island Battle, October 1942.

More HD recent profiles to come.

Wartime modifications

USS Louisville 1945, General Plans DPLA

The reconstruction was made in two phases and was quite extensive by 1945. So much so they shared little with the 1930s ships. First wave came in 1941-42 during refits and can be summarized by the following:

-Removal of the bridge, replacement by a smaller, lighter open bridge

-Portholes sealed, plate over but for the forecastle upper deck.

-Modification of the aft tripod mast, lowered and reconstruction of that section

-Installation of the early CXRAM radar on top of the pol extension of the tripod, behind the fighting top.

-Installation of protective shields for the 5-in guns

-Replacement of the 1.1 inches (in a case)

USS Augusta in drydock, 29 January 1936.

In 1944-45 came a second wave, even more radical:

-Complete removal of both tripods, fore and aft.

-New structure on four legs atop the bridge to carry the main FCS

-Modernized FCS telemeters fore and aft

-New structure aft, removal of the tripod

-Reconstruction of the radio room, behind the funnel

-New lattice mast for a radar installed behind the number two funnel

-Addition of five quad 40 mm AA and four twin 40 mm AA: Three quads forward, abreast the bridge and axial, forward deck, on sides sponsons behind the aft funnel. Twins aft deck.

-Addition of twenty 20 mm AA on the superstructures and turrets.

-Removal of the boats, replaced by rubber boats and inflatables

-On Chester, removal of the port catapult.

-On Louisville, significant differences in layout and new axial “flying bridge” aft supporting five extra Oerlikon AA guns.

ONI rendition of the Chester in 1944 and Louisville 1945

USS Chester wartime design evolution: 1942, 1944, 1945

USS chester 1945

USS Louisville 1945, showing the maximal firepower reached by surviving units, with the location of the 5-in, 40 mm and 20 mm AA.

Pattern sheet camouflage 1944 measure 32 design 9D for the Northampton class, the famous “staircase pattern”: Light gray, Ocean Gray, Dull Black for vertical surfaces and Deck Blue/Ocean Gray for the decks.

Northampton class as built |

|

| Displacement | 9,050 tonnes, 11,420 tonnes |

| Dimensions | 182,96 x 20,14 x 5,9 m |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 4 Steam Turbines, 8 Boilers, 107,000 shp. |

| Speed | 32,5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Range | |

| Armament | 3×3 8-in, 4×5-in DP, 2×3 21-in TTs, 4 floatplanes. |

| Armor | Turrets 50-60 mm, belt 76 mm, CT, casemates 95-20 mm, decks 25 mm. |

| Crew | 670 (1941), 850 (1944). |

USS Augusta and great events of WW2

Few cruisers in the WW2 USN fleet held so much historical encounters and events, despite being an old “tin-clad” peacetime cruiser. The choice of a Baltimore class would have been more logical. But the main reason was her fittings as a flagship, with extensive facilities, and care put on the fittings of her officers quarters and mess, since it was precisely built in peacetime, and was not under pressure of simplifications for mass production. From 1941 to 1945 she became almost the “official meeting US territory” – which on paper was real for all ships of the fleet, and because she was the only cruiser of the Atlantic fleet “fiting the bill”. The new Baltimore, Cleveland were deployed in the pacific whereas older prewar Brooklyn class and others treaty cruisers were in part sent to the Atlantic.

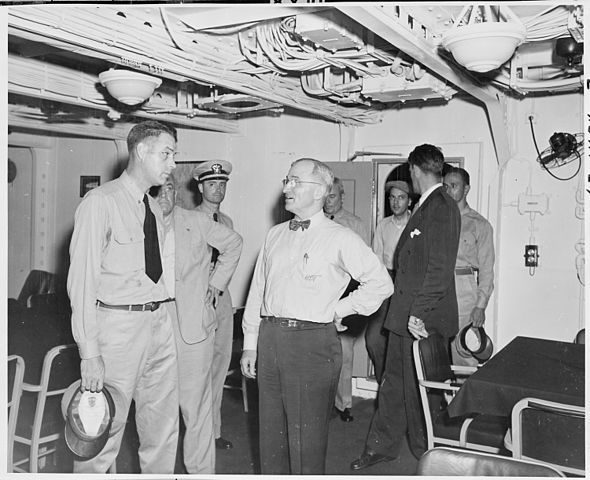

President Roosevelt, a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson, onboard USS Houston, Florida 1934 (NARA).

Winston Churchill meets Franklin D. Roosevelt & junior on board USS Augusta, 9 August 1941

Major General Patton and Rear Admiral Hewitt on USS Augusta, November 1942, Op. Torch

Normandy landings 1944: Senior Officials onboard USS Augusta (including General Omar Bradley)

President Truman onboard USS Augusta, attending Portdam conference, 1945

General assessment of the class

General quarters voiced by bugler on the intercom

The Northampton class improved on many points, designed when the Pensacola were not even laid down. The six cruisers really powered the USN “new fleet” of the interwar, first in a scouting squadron, then attached to task forces as the war erupted. They played their role well, but a weak protection cost the class three ship, so half the number built, which was a heavy proved to pay, only close to the New Oerlands class, of the second generation and arguably better protected. This proved the lack of armour was not the deciding factor. A crucuial aspect of these loss, in two cases at least, was the USN intel unaware of the range an lethality of the Japanese Type 93 “Long Lance” Torpedoes. The latter could reach 40,400 m (44,200 yd) at great speed, with a warhead more powerful than anything US designers could protected from for the ASW protection.

Accuracy was relatively poor in battle, as none of the ships could claim a clear win in a duel, at least on the Pacific. Only ships sank were in coordination with other cruisers. Their AA protection when used as escorts in task forces was not outstanding either. Their old 5-in guns were too slow to really deal with the IJN latest models, and only were valuable against incoming bombers, while the close range protection rested on the 1.1 in quad which proved awkward and not satisfying. Still plagued by some high metacentric weight excess, both this and their lack of AA was solved on the surviving ships, completely rebuilt as the Pensacolas were, with reduced superstructure to lighten them and add more AA.

Still, they could not host as many mounts as the larger Cleveland class. On all points the Baltimores were a huge improvement. Arguably the best performances were given by USS Augusta in North Africa, dealing with Vichy French vessels from Casablanca during Operation Torch… The use of their four spotter/reconnaissance seaplanes was also a curcial advantage, as the early CXAM radar was not good enough to provide accurate data in many cases, especially in a cluttered shore and busy environment.

Units of the British fleet escort USS Augusta carrying Pdt. Harry S. Truman to Potsdam conference in 1945.

Cruisers in reserve in Philadelphia NyS, 19 May 1955.

Sources/Read More

USS Houston entering Honolulu harbor for a presidential visit, 1934

Links

On pwencycl.kgbudge.com

On historyofwar.org

On UBoat.net

Camouflage measures

On navsource.org

Houston ca 30

Battle of Tassafaronga

USS Northampton

Specs on ww2db.com

ibiblio.org – USN cruisers Northampton class

Louisville – history.navy.mil

On wrecksite.eu/

On worldnavalships.com/

On world-war.co.uk

history.navy.mil

wiki

Books

J. Gardiner Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis NIS

“Waiting for the Main Attack”, Fighting For MacArthur, John Gordon – NIS

US warships OF WORLD WAR II – NORTHAMPTON CLASS HEAVY CRUISERS by Leland Doran

US Heavy Cruisers 1941-45: Pre War Classes, Mark Stille. Osprey Pub.

Battle to Save the Houston, Miller, John Grider, 2000

Videos

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwvHnCpC1tQ

The models corner

General query on Scalemates

modelshipgallery.com

-USS Northampton CA-26 The Scale Shipyard 1:96 WHU-C3

-USS Northampton Strike Models 1:144

-USS Northampton CA-26 (August 1941) Blue Water Navy 1:350

-USS Houston CA-30 Northampton class Cruiser “The Ghost of the Java Coast” Blue Water Navy 1:350

-USS Houston CA-30 Heavy Cruiser Corsair Armada 1:700 (and others)

-Northampton class Heavy Cruiser XP Forge 1:1200

3D rendition

The Northampton class in action

USS Northampton (CA 26)

USS Northampton (CA 26)

USS Northampton was laid down on 12 April 1928 at Bethlehem Steel Corp.’s Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts and launched on 5 September 1929 sponsored by Grace Coolidge, wife of the former President, and commissioned on 17 May 1930 under command of captain, and later later Vice Admiral Walter N. Vernou. She made her shakedown cruiser with the Atlantic Fleet, going into the Mediterranean (summer of 1930) and back to make a fleet training in the Caribbean. The next interwar years 1931-39 can be resumed into the same routine, going through the Panama Canal Zone each time, between winters in the Carribean, and summer’s Pacific exercises with other cruisers and “fleet problems”. She was redesignated CA-26 in 1931 according to the London Naval Treaty. She was most often in the Pacific from 1932, with her usual home port being San Pedro in California and from 1936, Pearl Harbor. USS Northampton was one of first six ships to receive the new RCA CXAM radar in 1940.

Early WW2 Operations

USS Northampton in December 1941 escorted Admiral William Halsey, Jr. on USS Enterprise task force when the attack on Pearl Harbor took place. Back home the 8th, she was prepared for a sortie on the 9th, searching the IJN fleet northeast of Oahu and sailing up to Johnston Island, and west of Lisianski Island, pushing to Midway Atoll but for nothing. On 11 December USS Craven collided with USS Northampton during the always dangerous refueling at sea operation.

Until January 1942, USS Northampton joined further searches until she was detached with USS Salt Lake City to shell Wotje Island on 1 February 1942. This targetd Japanese buildings, fuel dumps and destroyed two Japanese ships. The same was repeated on Wake Island on 24 February, but this time under resolute Japanese counterfire. Northampton sank a dredger, silenced the batteries and put installations in flames, and while retiring was attack by landbased enemy seaplanes and patrol craft. Many were shot down and the rest was repelled without scoring a hit.

On 4 March 1942 both Salt Lakes and Northampton accompanied air striked on Marcus Island before going back to Pearl Harbor. In April 1942, always with USS Enterprise’s task force, she joined Hornet TF for the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, on 18 April. They went in the Southwest Pacific afterwards, stopping at Pearl, but missed the battle of the Coral Sea.

Battles of Midway and Santa Cruz

Northampton was soon prepared to hae a cover role in the battle of Midway still screening Enterprise. On 4–5 June during the fateful air strikes, she protected her carrier and returned undamaged to Pearl Harbor on 13 June. By mid-August, USS Northampton headed for the Southwest Pacific and cover the early Guadalcanal landings. She patrolled southeast of San Cristobal until 15 September when her fleet was ambushed by IJN submarines. They scored hits on USS Wasp and damaged North Carolina. Wasp woudld not survive the hits. Another torpedo badly damaged USS O’Brien just 800 yd (730 m) off Northampton’s port beam, but she escape any hot herself. Sailing with the also undamaged USS Hornet, she was screening her during Bougainville Island attack on 5 October 1942. She still screened her during the battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. This battle was “beyond the horizon” and she assisted USS Hornet, unfortunately badly hit by enemy aircraft that went through the cruiser’s weak antiaircraft battery. She attempted to take her in tow but Hornet at that point was doomed, and she instead helped evacuating the crew. She was scuttled, sunk by destroyer torpedo and gunfire.

The loss of USS Hornet, and attempt by Northampton to rescue her at Santa Cruz, 26 October 1942.

Battle of Tassafaronga and loss (30 Nov. 1942)

USS Northampton was part of a carrier-free combined cruiser-destroyer force intended on sinking incoming, expected Japanese reinforcements for their troops on Guadalcanal. The Battle of Tassafaronga started 40 minutes before midnight, on 30 November 1942. It happened as the IJN relief fleet expected showed itself in the “slot”, the US achieing complete surprise. Three American destroyers made a successful torpedo attack on the Japanese followed by the cruisers opening fire. The Japanese believed this was a “blue on blue incident” at first, not expecting the Americans to be there, and did not replt for seven minutes, instead trying to communicate by morse !. When they did, hell was unleashed and they emptied at once all their torpedo tube with deadly “long lance” torpedoes, hitting two unexpected American cruisers (the captains through due to their range they were safe). 10 minutes later anoyher torpedo wave came, making more hits and the whole fleet retire from the action. USS Northampton and Honolulu stayed behinf with six destroyers to continue the action and cover them.

Close to the end of this fight, USS Northampton was about to retire when struck by two torpedoes of the third wave. One hit tore a huge hole in her port side, decks and bulkheads being torn away while flaming oil sprayed all over the decks and superstrctures, putting the ship ablaze while she took a rapid list. Three hours later, dead in the water, and despite frantic effort by her safety teams, she started to sink stern-first. The captain orderd to abandon ship, but it was orderly and controlled. Most of the crew survived the battle and sinking, survivors picked up within an hour by destroyers of Task Force 67. 40 crewmen however also were stranded in two life rafts and later rescued by PT 109 (soon to be commanded by Lt.jg John F. Kennedy), landed on Tulagi Island. Overall, the battle was a tactical defeat due to the US achieving total surprise, but taking way too more losses with three cruisers severely damaged, and Northampton lost. Only on Japanese destroyer was claimed, but it was a strategic victory, denying a major reinforcement to Guadalcanal, offering the Marines a fighting chance. Among the deads was Chief Engineer, Commander (select) Hilan Ebert, awarded the Navy Cross and having a destroyer escort named after him, USS Ebert. Captain Willard A. Kitts survived and was also decorated from the Navy Cross, for handling a textbook evacuation. Later, remaining survivors would be rescued. They escaped sharks attacks for days, by ingeniously using cork-floated cargo nets making improvized rafts. For her wartile service, USS Northampton was awarded 6 battle stars.

USS Chester (CA 27)

USS Chester (CA 27)

Inter-war service

USS Chester was launched on 3 July 1929 at New York Shipbuilding Corporation (New Jersey) and commissioned on 24 June 1930 under command of Captain Arthur Fairfield, reporting to the Atlantic Fleet. She stopped for fitting out and preparations at Newport, Rhode Island, before ailing out on 13 August 1930 for an extensive European shakedown cruise. She visited Barcelona, Naples, Constantinople, Phaleron Bay, and Gibraltar. She headed back home to her namesake city of Chester in Pennsylvania, and was immobilized for post-crusier fixes and repairs on 13 October. She joined the Scouting Fleet as flagship for the Light Cruiser Division. On 6 March 1931 she carried the Secretary of the Navy to the Canal Zone, the transferred to USS texas, observing the annual fleet problem near Pearl Harbor. She carried him back to Miami, on 22 March. Next she took part in exercizes in Narragansett Bay and escorted two visiting French cruisers. Due to the London treaty she became CA-27 from 1 July 1931.

After an overhaul at NyC NyD she received her two catapults amidships and air group. She took part in another exercize off Hampton Roads on 31 July 1932 and was based in San Pedro, Los Angeles from 14 August. She made an exercize from 9 April 1934 as flagship (Commander, Special Service Squadron) to New York on 31 May and the Presidential Naval Review, then back to San Pedro. On 25 September 1935 she embarked the Secretary of War to the Philippines, for the inauguration of the president of the Philippines Commonwealth, on 15 November. She was back in exercises as flagship, Cruiser Division 4. On 28 October 1936 she was in Charleston, and by 18 November escorted USS Indianapolis with President Franklin Roosevelt onboard for a good-will visit to Buenos Aires and Montevideo. After West Coast fleet exercises and training cruises to Hawaiian and Alaskan waters, one on the East Coast, she was taken in hands for an overhault from 23 September 1940, until 21 January 1941. Many of her deficiencies, ocommon to the class were solved and she received the new USN RCA CXAM radar as well as additional AA.

She was sent to Pearl Harbor on 3 February for exercizes, and on the West Coast alwaus as flagship, Commander, Scouting Force, from 14 May 1941 until 18 June 1941. In October-November she escorted two army transports with reinforcements to Manila in the Philippines and joined Northampton and Enterprise when back, off Wake Island when hearing the 7 December attack.

Early Pacific Operations:

USS Chester supported the landing on Samoa on 18–24 January 1942 before joining Task Group 8.3 (Halsey) for the raid on Taroa on 1st February. Heavy air attack had her hit by a bomb in the well deck, killing 8, injuring 38. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 3 February, for repairs. After an escort mission to San Francisco, Chester joined TF 17 and was engaged in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi raid on 4 May 1942, and next, the attack on Misima Island in the Louisiade Archipelago on 7 May, plus the Battle of the Coral Sea on 8 May. She covered by AA fire the carriers. Five of her crew were wounded due to Japanese attacks. On 10 May she embarked the 478 survivors onboard USS Hammam evacuated from USS Lexington, landed in Tonga on 15 May.

After a West Coast overhaul, USS Chester arrived at Nouméa on 21 September 1942, where gathering forced to TF 62 were prepared to assault Funafuti in Ellice Islands. The laundings took plane on 2-4 October and she sailed in support of the Solomons, north of the New Hebrides. There, she was ambushed underway by I-176 and struck by a torpedo on her starboard side amidships. Thuis happened on 20 October. The impact killed 11 and wounded 12 but her ASW protection combined to efficient teams dealt with the damage and she was still able to steam to the safety of Espiritu Santo. After emergency repairs on 23 October she departed on the 26th as the troopship President Coolidge struck a mine. She sent her help as well as collecting 440 survivors, transferred back to Espiritu Santo. Then she proceeded to Sydney on 29 October for comprehensive drydock repairs. On December 25 1942 she was out, and proceeded for Norfolk for full repairs and a complete overhaul.

Late Pacific Campaign 1943-45

USS Chester, Mare Island, October 1943

USS Chester was back from her overhaul to San Francisco, post-repairs trials and training for her mixed crew with many new recruits, making for almost a full year. On 13 September 1943, she departed to act as escort up to Pearl Harbor (20 October). On 8 November 1943 she left Pearl Harbor, taking part in the invasion of the Gilbert Islands and on 18–20 November she bombarded Tarawa. As the the bombardment flagship she received accurate fire data and redirected fire for the group, noted as “very accurate”. Unfortunately this was not enough and losses were heavy. She later departed to bombard Apemoma in the Gilberts and covered the landings on Abemama, while shelling Taroa, Wotje, and Maloelap.

After a resplenishment during christmas, she was back to assume ASW/AAW patrols off Majuro until 25 April 1944. She was back to San Francisco for a brief overhaul on 6–22 May and reported to duty with TF 94 in the north Pacific, assaulting Adak Island in Alaska, on 27 May. She was also deployed in the shelling of Matsuwa and Paramushiru in the Kuriles on 13 June and 26 June before being back to Pearl Harbor on 13 August. Her last campaign started from 29 August with TG 12.5 (Wake Island, 3 September), Eniwetok (6 September), Saipan, Marcus Island (9 October) and was detached to TG 38.1 for carrier strikes on Luzon and Samar, Philippines Campaign, as well as missions off Leyte, searching for enemy forces after the second Battle for Leyte Gulf in October.

Chester off San Francisco, May 1944

From 8 November 1944, until 21 February 1945 Ulithi and Saipan became her resplenishment bases, and from there, she made sweeps of bombardments on Iwo Jima and the Bonins Islands. She also made close support during the invasion landings, on 19 February. After another ovehaul in San Francisco she was back to Ulithi (21 June) patrolling off Okinawa and covering minesweepers west of the island during the pre-landing phase. By late July she supplied air cover for the Coast Striking Group TG 95.2 off the Yangtze River Delta. In August 1945 her last wartime sortie was back North, to the Aleutians, and she was covering after the end of the war the occupation landings at Ominato, Aomori, Hakodate, and Otaru until October before gathering troops at Iwo Jima to carry them back home.

She sailed on 2 November for San Francisco (arrived 18 November) and made another run to Guam and back (24 November – 17 December 1945), before deparrting on 14 January 1946 for Philadelphia (arrival 30 January), to be was placed out of commission, Atlantic fleet reserve on 10 June 1946. Protected “under cocoon” for many years, she was ,ever called back for service and sold for scrap on 11 August 1959. For her service, despite a long interruption in 1943, she earned 11 battle stars.

USS Louisville (CA 28)

USS Louisville (CA 28)

USS Louisville Kulak Bay, 25 April 1943

Louisville (“Lady Lou”) was launched on 1 September 1930, built in Puget Sound Navy Yard (Bremerton, Washington state). She was commissioned on 15 January 1931 wuth Captain Edward John Marquart in command. She made her shakedown cruise during the summer and up to the winter of 1931 and sailed to New York City, then back to Bremerton via Panama. She participated in the Pacific 1932 fleet problem and started gunnery exercises on the San Pedro-San Diego are and that winter 1933, made her first visit to Pearl Harbor, before going back to the Californian coast and bac to San Pedro for maintenance. There, she became a schoolship for AA gunners training for a short while. In April 1934, she was ordered to San Diego and then prepared for a long cruise round the world in Central America, Caribbean, Mexican gulf and east coast. Back to San Diego she returned to her routine of gunnery and tactical exercises. By the sprint of 1935 she headed for Dutch Harbor in Alaska for exercizes in cold waters before saling to Pearl Harbor and fleet problems 1935.

In 1936 and 1937 she operated off the West Coast, part of the two fleet problems, and good will cruiser in Latin American while making local training exercizes. On 16 July 1937 the logbook noted a considerable noise and it appeared at 12:00 hours, she had collided with a halibut fishing boat, the Alten from Ketchikan in Alaska. Her crew was quickly put out of the water by her, assisted by the Coast Guard Cutter USCGC Cyane. Alten survived the colission and there was no fatality.

In January 1938, USS Louisville made another long Pacific cruise, sailing to Hawaii, Samoa, Australia, and Tahiti, before being back to Pearl Harbor, in time for fleet problem 1938. However she left an indirect macabre souvenir during her stay in Sydney, Australia: Indeed, when the passenger and crew of a sightseeing ferryboat ran together to the open deck rail to better see the passing by cruiser, the vessel turned and rapdly capsized. 19 died and survivors were picked up by the cruiser (having a better view eventually)…

During the winter 1938/1939 USS Louisville participated in the last yearly fleet exercise, in the Caribbean. By May 1939 when she headed back for her home port on the west coast, and return to Hawaii for the last autumn fleet problem before going for Long Beach and prepared for a long cruiser to the south Atlantic via Panama. However when stopped in Bahia she received orders to sail to Simonstown in South Africa to take her share of netrality patrols against U-boat-infested waters. At Simonstown she loaded $148 million in British gold to be carried safely to New York City. Mission accomplished she sailed to the Pacific where tension was growing.

Early Pacific Operations (1942-43)

On 7 December 1941 she was escorting A. T. Scott and former President Calvin Coolidge from Tarakan in East Borneo back to Pearl Harbor. While in Hawaii she saw the damage and went to California to be prepared for operations. She was assigned to Task Force 17, proceeding from San Diego in January 1942 to the Samoa, landing troops on 22 January and when back, covered and escorted a carrier plane raid (1–2 February 1942) on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. She lost one of her scout planes in operations (missing). After a resplenishment in Pearl Harbor, she departed for patrols off the Ellice Islands. By March she was reassigned to the carrier force TF 119, operating to stop the Japanese in the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomons. They stayed and patrolled in the Salamaua-Lae-Rabaul sector and Louisville returned afterwards to Pearl Harbor, and then to Mare Island Navy Yard for a small refit. Her anti-aircraft armament was modernized and she received 20 mm cannons. On 31 May 1942 she was ordered to Alaska. She steamed to the Aleutians, assigned to TF 8 to counter the expected IJN fleet there. TBut the Japanese carrier force never crossed them, as the attacks on Dutch Harbor took place at the same time as the Battle of Midway. She took part in the northern part of the “ribbon defense”, the western Aleutians, making convoy escorts and shore bombardment of Kiska. On 11 November after resplenishing in San Francisco she headed for Pearl Harbor, and the South Pacific, in escort of troop transports, reaching New Caledonia. She was back to Espiritu Santo, assigned to TF 67 active in the Solomons, until the end of year. On 29 January 1943, she participated In the Battle off Rennell Island last of the seven naval battles for Guadalcanal. This saw the end of any attems by the Japanese to retake the island. The Carolines campaign was practically over by the point.

Late Pacific Operations 1944-45

In April 1943 Louisville ws sent again in the Aleutians to join TF 16. She covered the assault and occupation of Attu on 11–30 May 1943, and made a pre-invasion bombardment for the assault on Kiska in July 1943. After the Japanese evacuated, she escorted convoys in the northern Pacific until the situation was stable and the area secure. In August 1943 she was back to Mare Island Navy Yard for an overhaul, noytably her worn-out machinery, as well as several welcome alterations. Thos overhault ended on 24 December 1943, her appearance chanhed a lot, with a new bridge, sorter mast, and aft tripod close to the second funnel. HMS Louisville received the complex camouflage measure 32-6D, a famous paint scheme with “staircases” motives, the most disruptive found yet. She also gained two new mark 34 main battery directors while her inadequate 1.1 in AA battery were swapped for more modern 40 mm Bofors, and additional 20 mm cannons, new radars and new fittings as a flagship.

She made her post-refit trials in January 1944, and for her first mission shelled Wotje Atoll (west of Kwajalein) on 29 January, blasting the airfield and troop concentrations also on Roi and Namur and covering the assault on 3 February. During the combardment she was the victim of a “blue on blue” as a 8-in shell from USS Indianapolis ricocheted on the ground, and ended as a near miss very close to Louisville starboard side. Shrapnel damaged the chiefs quarters and the bulkhead, while turret No.3 barrels were alsop damaged, but there was no injuries. Next she conducted as flagship the gunfire support group at Eniwetok.

Next, USS Louisville joined TF 58 (fast aircraft carriers fleet) for an offensive on the the Palaus in March 1844 and Truk, Sawatan in April. She replenishedin May, and by June was prepared for the invasion of the greater Marianas. During these operations she acted as gunnery flagship again, leading the shore bombardment operations.

After Saipan, she fired for 11 days on Tinian, and Guam. In fact she had the honor of being the first large US warship to enter Philippine waters since December 1941, the embodiement of MacArthur’s famous words. On October 21, 1944, during the offensice on Leyte she was attacked by Kamikazes, and hit by bomb shrapnel, killing one. On 25 October 1944 she took part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, in the battleline engaging the southern force, trying to pass the Surigao Strait. Admiral Oldendorf’s Battleships and Cruisers crossed the T of the fleet and “Lady Lou” had her share of hits.

USS Louisville was assigned afterwards to the fast carrier group TF 38, covering them during the pre-invasion strikes on Luzon. In early 1945, she headed for her nex objective, Lingayen Gulf, while en route (5–6 January) she was attacked by Kamikazes. Two went through the CAPs and firced AA barrage, and scored hits, the first kamikaze on 5 January blasted the No. 2 turrets, putting it out of commission, but only killing one, with 17 injured. Captain Rex LeGrande Hicks was also badly burned. The second hit the following day her starboard side signal bridge. Rear Admiral Theodore E. Chandler onboard as she acted as flagship, Cruiser Division 4, was fatally injured. He was helping sailors handling the fire hoses and died the following day.

Commander William P. McCarty took command of Louisville, managing to recover the ship, fire put down and operational status regained. For his efforts, he was awarded the Silver Star. 42 died during and aft this second attack, with circa 125 wounded, some dying afterwards from their burns. The Bridge was alsmot completely destroyed and control was now delegated to battery no. 2. Despite of this, still having two operational turrets, the cruiser resumed fire on the beaches, cliaming more aicrafts by AA. However the overall command ordered she was withdrawn on 9 January 1945, back to Mare Island Navy Yard.

Amazingly, repairs were over on April 10, 1945, after which she carried Admiral Halsey and 50 officers and 100 of his staff to USS Missouri at Guam. Next, she joined TF 54 and resumed gunfire support at Okinawa. On June 5, 1945, a kamikaze went trough a withering fire of 40 and 20mm AA cannons, that put it in flames, but it crashed close to the fist funnel, killing eight and injuring 45, destroying a quad 40 mm AA and bent the funnel, throwing overboard the seaplane ad its catapult clean off. Repairs were made and she was back in action on 9 June, ordered back to Pearl on 15 June.

End of the war

Her stay in Pearl Harbor for repairs extended until July, and then August, and by the 14th officers were informed of the end of hostilities and surrender. USS Louisville was prepared for postwar duties and on the 16 she sailed for Guam, and then proceeded northwards, to Darien in Manchuria with Rear Admiral T. G. W. Settle on board. There, she proceeded to the evacuation of Allied POMs, then Tsingtao, to accept the Japanese surrender (Vice Admiral Kaneko). She escorted surrendered IJN warships to Jinsen in Korea and was back to China, posted in Chefoo. Around 15 October, she was in the Yellow Sea force. She departed for San Pedro, and to Philadelphia, decommissioned on 17 June 1946, Atlantic Reserve Fleet. After 13 years due to her age she was struck on 1 March 1959, sold on 14 September and BU. For her long and impressive service she was awarded 13 battle stars.

USS Chicago (CA 29)

USS Chicago (CA 29)

USS Chicago stern in Brisbane 1930s

uss chicago, collision bow damage 10/25/1933

USS Chicago was launched on 10 April 1930 at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, commissioned on 9 March 1931 with Captain Manley H. Simons in command. From CL-29 classified along her weak armor as light cruiser, she became CA 29 due to the 1st July 1931 London Naval Treaty obligation.

Interwar service

After her shakedown cruise from the west coast to Honolulu, Tahiti and American Samoa, she returned to Mare Island on 27 July 1931 and crossed the Panama canal to the east coast. She arrived at Fort Pond Bay in New York, on 16 August and became flagship of the Scouting Force division Atlantic, until 1940.

In February 1932, she started gunnery exercises preliminary to Fleet Problem XIII, which was held off the California coast. This unit was therefore based on the West Coast and operated in the Pacific, from Alaska to Panama, and the Hawaiian Islands east. USS Chicago was repaired at Mare Island after being damaged when colliding on 25 October 1933 with the British freighter Silver Palm. It happened in dense fog off Point Sur, California. Three officers were killed in their quarters during the collision as the frighter’s bow penetrated around 18 feet into the cruiser’s port bow. Damage was estimated to be around $200,000, taken by insurances. She saied out on 24 March 1934 for annual fleet exercises held in the Caribbean.

In May 1934 she participated to a Presidential Fleet Review in New York Harbor. The Scouting Force was now operating off the east coast until returne dto San Pedro, California for the winter. In 1940 USS Chicago received the new RCA CXAM radar and operated off San Pedro until 29 September 1940 before being ordered to Pearl Harbor. For the next 14 Months, she took part in various task forces exercises, perfecting tactics and formations. When the December attack took place, she was in a goodwill tour in Australia.

She operated with Task Force 12 when ordered to make a five-day sweep in the Oahu-Johnston-Palmyra triangle to ty to catch the Japanese, before returning to Pearl Harbor on 12 December. She then was versed to Task Force 11 for more patrols, and on 2 February 1942, departed Pearl Harbor for Suva and the new ANZAC Squadron redesignated Task Force 44. In March-April 1942, she operated off the Louisiade Archipelago for the Lae-Salamaua offensives in New Guinea. She was ready to intercept an IJN reinforcement fleet on Port Moresby and provided cover for the US troopships to New Caledonia, the operating base.

USS Chicago off Tulagi, August, 9, 1942

On 1 May 1945, Chicago sailed from Nouméa and supported USS Yorktown Task Force raiding Tulagi, Solomons (Battle of the Coral Sea) and on 7 May, she headed for the Support Group hastily created to intercept a Japanese invasion fleet to Port Moresby. Air attacks cost USS Chicago many casualties from strafing attacks, but her AA gunners repelled these. The convoy was driven back and Chicago returned to her normal duties.

On the night of 31 May–1 June 1942 she was in Sydney Harbour when spotting and fired on an attacking Japanese midget submarine. Captain, Howard D. Bode was ashore when it happened and after hurridly coming back believed his officers drunk. But the submarine was confirmed and in fact three attacked Sydney Harbour, one entangled in an anti-submarine boom net and of the remaining two, one was sunk by depth charges and the fired two torpedoes at Chicago, one missing and hitting instead the converted ferry HMAS Kuttabul behind (21 killed) while the second torpedo hit but fortunately failed to detonate and skidded ashore onto Garden Island.

In June-July 1942 she operated in the Southwest Pacific and from 7–9 August, supported the first landings at Guadalcanal. On the 9th, she was part in the escort fleet engaged by night and by complete surprised off Savo Island. She was hit early on by a Japanese destroyer torpedo in her bow, with moderate damage, but more was to come from heavy fire exchanged at relatively close range until contact was lost. Captain Bode’s actions were questioned later in an inquiry led by Admiral Arthur Japy Hepburn, and the result caused Bode to shot himself on 19 April 1943. After the battle of Savo Island, USS Chicago was repaired at Nouméa, then Sydney, and eventually San Francisco, arriving on 13 October. Due to this early retirement she missed the first phase of the Guadalcanal campaign.

Battle of Rennel Island

USS Chicago left the drydock in Januray 1943, made post-refit trials and a shakedown with a partially new crew, extra training at Pearl Harbor, Early in January 1943, she departed San Francisco for Pearl and then Nouméa, departing to escort a Guadalcanal convoy. On the night of the 29th, the fleet was attacked by Japanese aircraft. It further developed as the Battle of Rennell Island.

Two burning Japanese planes, downed by AA, silhouetted Chicago enough for accurate torpedo attacks, with two hits causing her a severe flooding and total loss of power. Work by the safety team was amazing and they checked her list. USS Louisville tried to take her in tow, relieved later by USS Navajo the following morning. Meanwhile, fighters from USS Enterprise came to provide cover, but they had to come back, and during the afternoon, 20 G4M “Betty” bombers were spotted.

They left little chance to the cruiser, rapidly hit by four torpedoes: One struck forward of the bridge, three in the engineering spaces, but returning patrolling fighters shot down all but two of the attacking planes, too late. Captain Ralph O. Davis onboard USS Chicago received news that damage was way too extensive this time. Her ordered to abandon ship and the crew was evacuated rapidly as he ship sank stern first just 20 minutes later. USS Navajo and escorting destroyers collected 1,049 survivors, but there were 62 died, or missing as a result of the battle and sinking.

The Japanese authorities widely publicized this battle, claiming… two battleships and three cruisers. Aside USS Chicago the battle costed the USN a destroyer, USS De Haven. Admiral Chester Nimitz was adamant not to release anuyhing of this loss until 16 February 1943. Due to her short campaign, Chicago was only awardared three battle stars.

USS Houston (CA 30)

USS Houston (CA 30)

USS Houston off San Diego October 1935

Interwar years

USS Houston (CL, then CL 30 after the London Treaty) was launched by Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company in Virginia on 7 September 1929 and she was commissioned on 17 June 1930 with Captain Jesse Bishop Gay in commanding. After her trials and Atlantic shakedown cruise she was back for post-fix repairs in October 1930. Next, she visited her namesake city before joining the fleet for exercizes off Hampton Roads. After a stop in New York she sailed on 10 January 1931 for the Pacific, crossed the Panama Cana and stopped at Parl Harbor before arriving at Manila on 22 February. She became flagship there of the Asiatic Fleet and participated in training operations until early 1932, mobilized and sent on 31 January to safeguard US interests in Shanghai.

She landed Marine and Navy gun platoons securing key areas in the city, and complishing the mission without serious accident. The heav cruiser then departed for a good will cruise to the Philippines in March 1942, making another to Japan in May 1933. She was relieved by USS Augusta as flagship on 17 November 1933 and sailed to San Francisco, joining the Scouting Force. Next, was a serie of routine training, Fleet Problems and maneuvers in the Pacific, alternating by sorties on the East coast.

Among her “special cruises”, she carried President Franklin Roosevelt from 1 July 1934 in Maryland to a 12,000 nautical miles trip through the Caribbean, stopping at Portland in Oregon and making a cruise to Hawaii in between, also carrying Assistant Secretary of the Navy Henry L. Roosevelt. She was back to San Diego on 15 May 1935, making afterwards a short cruise in Alaskan waters, before making another Presidential cruise from Seattle and another from 3 October (vacation cruise to Cedros Island in the Cocos Islands) before reaching Charleston, South Carolina. USS Houston was present when the Golden Gate Bridge was openoned in San Francisco on 28 May 1937. Her next Presidential trip was for the 14 July 1938 Fleet Review followed by a 24-day cruise concluded on 9 August 1938 in Pensacola, FL.

USS Houston became flagship on 19 September carrying the mark of Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, until 28 December, back to the Scouting Force. Fleet Problem XX came on 4 January 1939 and in Key West she embarked the President and the Chief of Naval Operations (Admiral William D. Leahy) to monitor the operations from her bridge. She was back in her homesake city on 7 April and headed for Seattle. She was later made flagship of the Hawaiian Detachment in Pearl Harbor, arriving after her post-overhaul shakedown on 7 December 1939. She was back to Mare Island on 17 February 1940 and returned for the Philippine Islands on 3 November 1940, becoming flagship of Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander Asiatic Fleet. Her last refit saw her mounting five quad 1.1″/75 AA guns shipped to Cavite Naval Yard, four installed aboard.

Battle of Makassar strait and Timor convoy

Admiral Hart deployed his fleet and the night of the Pearl Harbor attack USS Houston was steaming from Panay Island for Darwin. She arrived on 28 December 1941 via Balikpapan and Surabaya. Patrols were followed by joining the American-British-Dutch-Australian or more famously “ABDA squadron”, the composite naval force to be assigned the defense of Java from Surabaya. This also sealed her fate.

Houston’s gunners claimed 4 Japanese aircraft in the Battle of Bali Sea (Battle of Makassar Strait) on 4 February 1942. Admiral Karel Doorman commanded the force she was part of, directing them to a Japanese forced reported off Balikpapan. USS Houston was hit during the subsequent battle, her N°3 turret jammed. USS Marblehead sank later. Doorman’s plans were thwatarted and the force retired.

USS Houston arrived at Tjilatjap on 5 February, staying until 10 February 1942 there. She left for Darwin, escorting a convoy to Timor. Part of the fleet was USAT Meigs, SS Mauna Loa, SS Portmar, Tulagi, accompanied by USS Peary, HMAS Warrego, and Swan. They departed on February 15th bounf for Koepang.

One the morning of the 11th, their position was known to the Japanese, following them with a flying boat alla along. The latter attacked with bombs before leaving, missing. The next morning another single flying boat also came to shadow the convoy. Before noon, it had coordoninated bombers and flying boats, coming in two waves on the convoy.

The first attack saw Mauna Loa damageed and the cruiser firing but not making any hit. The the second attack was more resolute and Houston’s AA crews barrage was much more efficient, shooting down 7 of the 44 planes. The convoy was spared and eventually reached Timor. Meanwhile Houston launched one of her scout planes to look after a possible Japanese fleet incoming. The presence of Japanese carriers covering an invasion fleet of Timor was suspected. Fearing an ambush, ABDA command ordered the convoy back to Darwin.

Houston and Peary joined however combat forces at Tjilatjap and Peary soon broke off to chase off a suspected IJN submarine. Short of fuel, she joined the convoy bound to Darwin, leaving Houston alone. She escaped the Japanese attack on Darwin on 19 February, seeing Peary, Meigs and Mauna Loa sunk, Portmar beached.

Battle of Java sea

Admiral Doorman, informed of the incoming massive IJN fleet resorted to meet it nonetheless, but ordered to concentrate the main convoy, not trying to engage the IJN cruisers. On 26 February 1942 the squadron comprised USS Houston, HMAS Perth, HNLMS De Ruyter, HMS Exeter, HNLMS Java and ten destroyers. They eventually met Admiral Takeo Takagi’s for of four heavy cruisers, 13 destroyers. It was late afternoon, 27 February 1942. Japanese destroyers laid a smokescreen to hide the cruisers and a gunnery duel started. The Japanese made at first an ineffective torpedo attack, and during a second, they sank the destroyer HNLMS Kortenaer. HMS Exeter and Electra were both hit and at 17:30 Admiral Doorman turned south toward the Java coast, still chasing after the convoy.

A third torpedo attack was launched, but Doorman’s ships were now occulted by the coastline. Nevertheless, the destroyer HMS Jupiter was sunk, HMS Encounter detached to pick up survivors from Kortenaer. The American destroyers present were ordered back to Surabaya, short of torpedoes. Doorman’s four ships turned north to follow the convoy’s route and at 23:00, the cruisers was catched by Japanese surface group, both sailing parallel courses. The fight look even, but the Japanese fired their very long range torpedoes, which hit (again, their range really was a surprise to the alles). They hit De Ruyter and Java, Doorman while sinking ordering Houston and Perth to retire to Tanjong Priok. Exeter on her side managed to flee to Surabaya. She will be sank later as her escort destroyer. It was only a respite for Houston.

Battle of Sunda Straits

Houston and Perth arrived in Tanjong Priok on 28 February 1942. There, they tried to resupply, but but fuel shortages and no ammunition left made them unable to continue operations. They were to sail to Tjilatjap with Dutch destroyer Evertsen, but the latter was delayed, and they depatted without. Believing the Sunda Strait was free, intelligence reports confirming enemy presence was beyond 50 miles (43 nmi; 80 km) they started their course there. Unbeknowingly, a Japanese force assembled at Bantam Bay and as around 23:06, Houston and Perth were off St. Nicholas Point lookouts of the latter spotted a ship, later realized to be a Japanese destroyer. HMAS Perth engaged her, but this was just a trick, as the Japanese appeared and surrounded them.

The two cruisers were about to make their last stand, one of the most amazing of WW2: They evaded nine torpedoes from the destroyer IJN Fubuki. They apparently sank a transport, forced three others to beach but the Sunda Strait was closed by an IJN destroyer squadron, soon to be joined by the heavy cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. At midnight, Perth’s captain tried to get through the screen of destroyers. She was hit by four torpedoes under a couple of minutes, plus close-range gunfire which left her ablaze, stopped dead in the war, sinking at 00:25 on 1 March.

On her side, USS Houston evaded torpedoes and stayed at safe gunnery distance. But despite of this, she was low on ammunition, especially for her forward turrets, obliging the crew to manhandle these very heavy shells (260 Ibs, 118 kgs) from the disabled aft one, disabled, to the two forward turrets. But soon, USS Houston was hit by a torpedo just after midnight, starting to list and loose speed and direction. Her gunners scored hits however still, on three destroyers and sunk a minesweeper. Soon the internal “death dance” of the destroyers that were closing, caught her with three more torpedoes hits in quick succession.

If that was enough, a shell hit the bridge, killing Captain Albert Rooks at 00:30. More were coming, both from destroyers and cruisers. Her engine rooms flooded her poweplant stopped and she lost all sources of power, only lightened by multiple fires. She soon came to a complete stop while the Japanese destroyers moved in for the kill. They came so close as to open machine-gun fire. Without mercy they kill every soul on sight, clearing the decks, some even using rifles to achieve men in the water. At about 00:35 the crippled crusier rolled over and sank, but still, 368 managed to survive including a Marine Detachment. They were all collected and became POWs, 77 dying in captivity. She won two Bronze service star and a United States Navy Presidential Unit Citation.

USS Augusta (CA 31)

USS Augusta (CA 31)

USS Augusta, laid down on 2 July 1928 at Newport News in Virginia like Houston, at Newport News, was launched on 1 February 1930, and commissioned at the Norfolk NyD on 30 January 1931 under command of Captain James O. Richardson. Redesignated heavy cruiser, CA-31 in between. She has one of the most interesting and long career, spending her wartime in the Atlantic contrary to the others, and gaining much acclaim in the press for her diplomatic roles. Although the crew viewe this as an honor, her relatively “cushy” assignation only won her three battle stars.

Early Interwar service (1931-33)

Her shakedwon cruiser revealed problems with her turbines, leading to some Damage and subsequent repairs, and so she had botches initial training when steaming to Colón in Panama, and back. She became commander flagship for Scouting Force (Vice Admiral Arthur L. Willard) on 21 May 1931. This summer, she operated with this unit, making tactical exercizes off the New England coast. In September 1931 she started her winter drills in the Chesapeake Bay and carribeans, with gunnery drills and by mid-November she went in her home port, Norfolk NyD for her second crew’s leave.

In 1932 the Scouting Force assembeled at Hampton Roads, steamed to Guantánamo Bay in Cuba for training evolutions until 18 February, crossing the Panama Canal for her first eastern Pacific deployment, and Fleet Problem XIII. She was based in San Pedro in California. Her group took part in a scenario of attacking three simulated “atolls” on the West Coast, giving them skills in strategic scouting and defending and attacking a convoy. This was over on 18 March.

The Fleet Problem ended on 18 March. Well before Roosevelt decided of keeping the Fleet at Pearl Harbor in 1940, the Hoover Administration wanted it concentrated on the West Coast in 1932 hoping to restrain Japanese aggression in China. So Augusta and her group were already there for Fleet Problem XIV in February 1933 and she continued to operate in the eastern Pacific until relieved as flagship by October 1933, and she sailed to Puget Sound (Washington) for maintanenance befiore being ordered to the Asiatic fleet.

With the Asiatic fleet (1934-1937)

In late October 1933 she sailed the “Great Circle” route from Seattle to Shanghai, Huangpu River, arriving on 9 November. Admiral Frank B. Upham, the C-in-C, Asiatic Fleet raised his marke onboard USS Augusta relieving her sister ship USS Houston. By December she operated along the coast, and the Philippines, training after her yearly overhaul at Cavite and Olongapo. She returned on the China coast to “showing the flag” before heading to Yokohama in Japan (4 June 1934) Admiral Upham attending the state funeral ceremonies of Admiral Heihachiro Togo. The cruiser fired a 19 guns salvo in honor. Departing on 11 June, she visited Kobe and headed to Tsingtao, then Chinwangtao in the Qinhuang Island (10 September), Chefoo and back to Shanghai on 26 September.

USS Augusta stayed in Chinese waters and departed Shanghai for Guam (5 October) under command of a new captain, Chester W. Nimitz (yes, this one). She made her first cruise to Australia, arriving in Sydney on the 20th. Admiral Upham visited Canberra with his full staff CinCAF back on board on the 26th of October. She left for Melbourne (29th) and left on 13 November for Fremantle and Perth. On 20 November, made another cruiserr due east, for the Dutch East Indies.

Arriving in Batavia on 25 November, she sailed for Bali, Lauban Amok (5 December), then Sandakan, Zamboanga, and Iloilo, and proceeded to Manila, for her her yearly overhaul at Cavite in drydock at Olongapo, Dewey Yard. She re-embarked Admiral Upham for Hong Kong (15 March 1935). CinCAF was embarked in Isabel for a trip to Canto as the cruiser’s draft frorbade her passage up the Pearl River. She sailed out on the 25th for Amoy and back to Shanghai, arriving on 30 March.

On 30 April she made a second visit to Japan: Yokohama (3 May), Kobe,and back to China on 25 May, Nanking. She departed on 4 June for Shanghai. Nicknamed “Augie Maru” by her crew she was still there on 27 June starting a cruise off North China up to Tsingtao on the 29th. After summer training, she departed Tsingtao on 30 September for Shanghai and Admiral Orin G. Murfin relieved Admiral Upham. She departed for points south and Admiral Murfin was transferred to USS Isabel, again due to draught size, to visit Bangkok on 15-22 October and back to the cruiser to visit Singapore until 30 October 1935. Next was Borneo, southern Philippine with Zamboanga and Iloilo and back to Manila (11 November).

After her yearly overhaul, she visited Catbalogan, Cebu, Tacloban, Davao, Dumanquilas, Zamboanga, Tutu Bay, Jolo, and Tawi Taw and back to Manila (29 March 1936). Next, she departed for Hong Kong (2 April) while the admiral visited Canton in early April. Augusta visited Amoy, Woosung and proceeded up the Yangtze, to Nanking. She then sailed down to the Huangpu River and Shanghai while Admiral Murfin transferred his flag to USS Isabel, to Ichang and in Panay then back to Hankow and Shanghai. The cruiser departed for Japan on 21 May 1936, a third good will visit, starting by Yokohama and Kobe and departing on 13 June for Tsingtao. During these summer exercizes, she alternated between Chefoo and Tsingtao, before departing in September for Chinwangtao (foot of the Great Wall of China), Admiral Murfin disembarked for a of Peiping (Peking, inspecting the Marine Corps legation guard and back by train to Chinwangtao. Augusta sailed to Chefoo and Tsingtao before departing for Shanghai on 1st October.

Admiral Harry E. Yarnell deplaced Murfin she the cruiser steamed in the Huangpu River on 3 November 1936, starting her annual southern cruise: Hong Kong, Singapore, Batavia, Bali, Makassar, Tawi Tawi, Dumanquilas Bay, Zamboanga, Cebu and back to Manila on 19 December for leave and overhaul. Alterations included the fitting of additional splinter protection over the machine gun positions on her fighting tops. On 29 March 1937 she left the drydock and the admiral returned his mark on board. Events close by would soon degenerate: In Philippine waters in Manila and Malampaya (April 1937) she sailed with the entire Asiatic Fleet for Hong Kong.

She sailed for Swatow on the 18th. After Amoy she sailed in the Huangpu River (24 April) and was back to Shanghai, upstream from the city proper, remained until 5 May 1937, the prceeding to Nanking, staying in the Yangtze port until the 9th, then Kiukiang, further up. Admiral Yarnell rejoined Augusta at Shanghai on 2 June 1937, and the cruiser left for the usual North China summer exercises from Chinwangtao, and Tsingtao (26 June).

Operations in Shanghai (1937-1938)

USS Augusta moored in Shanghai, 1939, facing the bund.

They were inrerrupted by an event of first importance: On the night of 7 July 1937, the Japanese and Chinese clashed near the Marco Polo Bridge, outskirts of Peking. This casus belli escalated into a state of war in North China, Peking falling rapidly by the end of July. Admiral Yarnell cancelled his goodwill visit to Vladivostok, but was ordered to proceed by the admiralty anyway. Her was there on 24 July with four destroyers. This was a first since 1922 and officers and men were lavishly entertained. On 1 August, she departed for Chinese waters, Chefoo and Tsingtao, where Admiral Yarnell received the latest intell on the situation, while others Japanese movements around Shanghai where increasing pressure. The death of a Japanese lieutenant and his driver near a Chinese airfield on 9 August precipitated the intervention, but on Augusta, there were fears as the city had considerable American interests, in the large International Settlement, so the admiral decided to steam her on the morning of 13 August 1937.

She went through a typhoon underway, slowing down to five knots and for the fist time having 30 degrees rolls, that washed away the port motor whaleboat and its davits. USS Augusta arrived in Huangpu River. and passed by many Japanese warships, light cruisers and destroyers, rendering the prescribed passing honors to the American admiral. A Chinese Air Force Northrop 2E tried to bomb Japanese positions in the International Settlement which caused extensive damage and heavy loss while another over Whangpoo dropped two bombs exploding off USS Augusta’s starboard bow so the crew was ordered to paint large American flags on top of her three main turrets as neutral. On 18 August Augusta was unmoored and proceeded upstream to the Shanghai Bund with tugs. Up to January 1938 she was close enough to observe the Sino-Japanese hostilities, with her guns to bear if the occasion arose.

Soon evacuating Americans from the war zone became a priority. Sailors from Augusta’s landing force were sent to protect merchants and civilians and her proper Marine Detachment ashore to reinforce the 4th Marines establishing defensive positions in the neutral area. On 20 August 1937, a Chinese anti-aircraft shell landed on her dekc, killing a Seaman, wounding 18 others. Chinese planes later bombed by error the American Dollar Line SS President Hoover, causing one fatality and several several wounded. Admiral Yarnell called to the admiralty for a division of heavy cruisers to carry out the evacuation, but President Franklin Delano Roosevelt resisted the idea.

At Shanghai, the admiral nevertheless, continued to send intel reports back to Washington, notably towards a possible future enemy. On 12 December 1937 the situation escalated again as IJN planes sank USS Panay and three Standard Oil tankers, north of Nanking. The survivors arrived at Shanghai on USS Oahu, moored alongside Augusta and debriefed over the incident. On 6 January 1938, USS Augusta departed for the Philippines and yearly overhaul. Admiral Yarnell remained in Shanghai meanwhile with a small staff on board USS Isabel. Augusta was back to Shanghai on 9 April 1938, but departed, visiting Tsingtao on 12 May and Chefoo, the Chinwangtao (15 May). Admiral Yarnell disembarked for Peking, inspecting Marine detachments there, and back Chinwangtao on 29 May, Augusta sailing to Chefoo and Shanghai on 6 June, disembarking the admiral, inspecting Nanking and Wuhu.

The cruiser was back to Tsingtao on 3 July 1938, aternating with Chinwangtao for her summer exercizes until early October, before proceeding to Shanghai and spending Christmas there, before leaving for the Philippines on 27 December 1938. After her yearly overhaul and training in Philippine waters she made a first visit to Siam in French Indochina, and Singapore before going back to Shanghai (30 April 1939). She stayed there until 8 June, then departed in the north, Chinwangtao, Chefoo and Tsingtao and back to Shanghai.

On 25 July 1939, Admiral Thomas C. Hart took command of CinCAF. In Tsingtao on 2 August the cruiser remained there for summer exercizes when the war broke out in Europe. Augusta visited Shanghai twice again, then Chinwangtao, Chefoo, and Peitaiho befire returning to Shanghai in October-November. She later left for the Philippines, stopping in Amoy en route and reached Manila on 25 November for her yearly overhault, staying there until March 1940, and training in April off Jolo and Tawi Tawi.

She sailed for Shanghai, Swatow and Amoy, in April 1940, then North China, Chinwangtao in June, and operations off Tsingtao until late September. She departed Tsingtao for the last time on 23 September 1940, reaching Shanghai, then proceeding to Manila (21 October) and was relieved in November by her sister ship Houston, modernized. She sailed back for home at last, after spending six years as flagship, USN Asiatic fleet.

Back Home: Preparations for war (1940-41)

On 24 November 1940, USS Augusta like the rest of the fleet, searched north of the Hawaiian chain, looking specifically at “Orange” (Japanese) tankers reported there. Meeting bad weather, she cancelled the used io her own aircraft, closed to the focal point of her search, and prepared condition III. Special lookouts were posted from dawn to dark with a visibility down to 8 miles (15 km) at some point. Her Captain John H. Magruder, Jr. estimated she covered the designated area and it was time to break radio silence until and due to bad weather, cancelled refueling at sea and decided to get back home.

She sailed to Long Beach afterwards, arriving on 10 December 1940 for a well deserved overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard. Her battery gained four additional 5 inch guns mounted atop the aircraft hangar, with splinter protection shields as well as on the boat deck, 3 inch AA guns installed, waiting to be replaced by quad 1.1 inch guns), and Mark XIX directors for the secondaries which altered her silhouette. A pedestal was fitted atop the foremast also for the CXAM radar antenna.

Presidential cruiser, 1941

Admiral King & F.D.Roosevelt during the “Atlantic conference”.

Her overhault completed she left Mare Island on 11 April 1941 with a new paint scheme for San Pedro until 13 April, transited the Panama Canal to be assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, on the 17th. At Newport, on 23 April she hosted Grand Admiral Ernest J. King, now promoted C-in-C, Atlantic Fleet. On 2 May he had his flag on USS Augusta, still anchored in Newport and used as floating HQ, administrative CINCLANT flagship before sailing for Bermuda on the 24th. She returned on the 28th, before heading for Narragansett Bay in May-June, and heading for NYC NyD, chosen to host the state meeting between the president and PM Winston Churchill.

USS Augusta was chosen as the President’s flagship in mid-June, after Admiral King seeing him for implemeting his Western Hemisphere Defense Plan No.4 strategy. On 16 June, the Yard was informd to install noth the CXAM radar and 1.1 inch (28 mm) AA guns in place of the 3-in guns, “incident to possible future Presidential use and other urgent work.” trigerring heated discussions between BuShips and CINCLANT due to availability issues, BuShips being left in the dark towards Presidential plans. The cruiser eventually left the yard on 2 July, resumed operations along the eastern seaboard, down south to Charleston and Hampton Roads and back to Newpor, staying in August. Eventually, Churchill started the Atlantic crossing on HMS Prince of Wales, while the president left Washington D.C. on 3 August, joined a Submarine Base at New London (Connecticut), embarked the Pdt. yacht Potomac escorted by USS Calypso, and headed for Appogansett Bay. On 4 August evening, Potomac anchored in Menemsha Bight (Vineyard Sound) to meet the recently arrived cruiser, ready to depart and being joined by USS Tuscaloosa and five destroyers.

On the morning of 7 August 1941, USS Augusta and escort dropped anchor in Ship Harbour, Placentia Bay, awaiting Churchill, which arrived on 9 August and visited the president at 11:00 that day, followed by a lunch and dicussions all the afternoon with Harry Hopkins coming from England also on the Prince of Wales. From these discussions the following day emerged the famed “Atlantic Charter.” On 12 August the ships departed after a parade and band. Next, the cruiser departed with Tuscaloosa and escort for Blue Hill Bay in the Maine, to meet Potomac and Calypso where the President would embark. On the 14, the President saw the service debut of USS Long Island, a propotoype carrier pushed forward by the Chief Executive, followed by Admiral King hosting a farewell luncheon for the President. After the transfer, USS Augusta returned to Narragansett Bay (15 August) and headed for NyC NyD and Newport on 29 August, Admiral King retaining the cruiser as his flagship, which also embarked the Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox for more reunions.

For several months, USS Augusta became Admiral King, C-in-C Atlantic’s flagship and floating HQ.

For several months, USS Augusta became Admiral King, C-in-C Atlantic’s flagship and floating HQ.

Early wartime Operations (Jan-October 1941)

On 7 December 1941, USS Augusta was in Newport. Until the 11th, she patrolled, and this went on until 11 January 1942, after a christmas crew’s leave. On 5 January 1942 Rear Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll replaced Admiral King as the C-in-C Atlantic Fleet, King now the being supreme commander of US Naval forces. The cruiser left Newport on 12 January for Casco Bay in Maine, conducted training and was back to Newport. On 17 January, Ingersoll left Augusta for USS Constellation, the venerable 1797 Constitution class frigate. On 19 January USS Augusta was in Bermuda, to join Task Group 2.7 operating off Martinique, conducting a demonstration and surveillance of the Vichy French fleet interned there. On 5 March she back in Bermuda.

She joined TG 22.7 (USS Ranger, Savannah, Wainwright, Lang, Wilson) patrolling the Caribbean until detached and escorted by Hambleton and Emmons reached New York. After repairs and alterations until 7 April, she sailed for Newport, Casco Bay, conducting experimental firings on a drone. Later via Cape Cod Canal she sailed back to Newport and joined Task Force 36 (Flagship USS Ranger) was flagship, the cruiser departed on 22 April for Trinidad. Augusta launched her scout planes during a refuelling as the fleet headed for Africa, launching 68 Army Curtiss P-40s on 10 May 1942, bound for Accra, later to be sent to the British RAF in north Africa.

Back in Trinidad on 21 May, she headed for Newport and on 26 May, departed with USS Corry for Hampton Roads, later joined by Rear Admiral Alexander Sharp, now flagship again, in command of TF 22. Corry was joined by USS Forrest as escort and she went back on 31 May to Newport, the departed for calibration of radio direction finders off Brenton Reef. USS Ranger’s group joined in, and they trained off Newfoundland from 5 June. By the end of June, the cruiser was overhauled in New York, and moved to Newport, sortied with TF 22 for the Gulf of Paria (Trinidad) and making second airplaine ferry mission (72 Army planes) to West Africa.

Back to Norfolk, the cruiser was inactivated from 5 August (limited availability) until 18 August, before short range battle practice, night spotting exercises, in Chesapeake Bay. She made another sortie with USS Ranger on 23 August, gunnery training, shore bombardment, and AA defense exercises off the Virginia Capes until 11 September, and back again on 1 October in Chesapeake Bay. On 23 October 1942, Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt had his flag onboard, the unit now renamed TF 34. She was soon prepared for a major operation in north africa.

Operation Torch (November 1942)

In the Atlantic, 18 April 1942