HMS Furious (1917)

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classHistory’s first aircraft carrier

The HMS Furious is like a warship with several lives. She started as a battlecruiser, evolved into an hybrid plane carrier, an experimental aircraft carrier during WW1, and a modern aircraft carrier during WW2. But above all, she was the first to carry out airborne operations in WW1 with a squadron. The numerous tests that were performed during these pioneering years showed how to built and operate an aircraft carrier from scratch. Lessons were applied to the design of a brand new serie of ships, either conversions or from the keel up, like the Japanese Hosho and the Hermes. The new king of the oceans was born and maritime history took a new twist.

HMS Furious’s First life, 1917

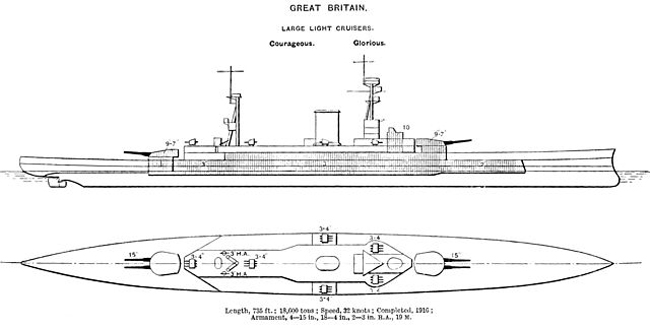

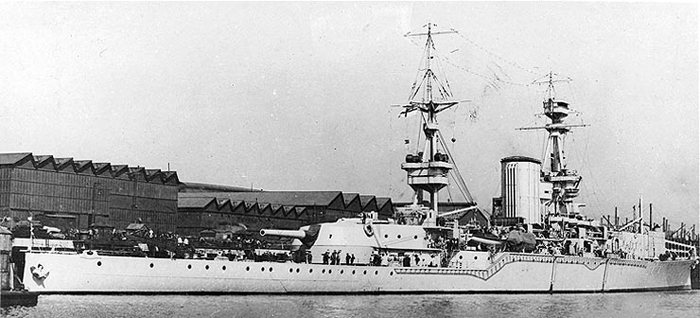

HMS Courageous

She was first designed as a successor of the Repulse class, part of a pair of the Courageous-class battlecruiser, which were specifically designed as “light” compared to the previous Repulse. They had been planned in 1915 already, to meet a set of requirements laid down by First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher about his cherished Baltic Project.

Jackie Fisher’s hush-hush cruisers

Their size was the result of the need of a lot of raw power in order to maintain a high speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) to outrun cruisers and be still fast in heavy weather. Their powerful armament was to repel possible cruisers that went too close, or to bring artillery support. Protection compared to any battlecruisers of the time was laughable, with just 3 inches (76 mm) of armour on the belt, forecastle deck, ASW bulges, machinery cofferdam, but using triple torpedo bulkheads. It was light also to have a limited draught in order to cope with the shallow waters of the area. The last requirement was underlined as the most important of all.

Brassey’s naval annual design scheme in 1923

Director of Naval Construction Sir Eustace Tennyson-d’Eyncourt, send to Fisher on 23 February 1915 a sketch for a smaller version of the Renown-class battlecruisers. One gun turret was sacrificed (so only 4 guns left) and armour protection drastically reduced. However, since the Chancellor of the Exchequer forbade constructions heavier than light cruisers in 1915, Fisher made them passe as “large light cruisers”. However a veil of secrecy was placed around the project, soon nicknamed “Lord Fisher’s hush-hush cruisers” or the “Outrageous class”.

Design specifics of the Furious

HMS furious stern, showing the impressive 457 mm (18 in) gun. Modifications at the front to launch planes were already made.

While HMS Courageous designed was already fixed and blueprints were drawn, her sister ship Furious saw some changed a few months later. The revised requirement included two BL 18-inch Mk I guns (457 mm guns), the largest caliber so far ever designed for any Royal Navy ship. They were placed in the same turrets, carrying each a single mount to save time. So the final armament looked like one from a monitor, far away for the concept of HMS Agincourt! The turrets were even designed to revert to twin 15-inch (381 mm) if the new caliber proved unsatisfactory. Gunnery experts objected that the time needed to reload would make any corrections useless, compounded with that speed. HMS Furious’s secondary armament was also modified, with several BL 5.5-inch (140 mm) Mk I guns replacing the older 4-inch (102 mm) dual-purpose guns used on first two ships. They were there to compensate for this slow rate of fire against cruisers and destroyers. Displacement and beam rose, but she has less draught.

Armament

HMS Furious two 18-inch BL Mark I guns were derived from the 15-inch Mark I gun used on the two others, just scaled up. The single-gun turrets were also derived from the twin-gun 15-inch Mark I/N turrets; The barbettes could therefore fit two models of turrets but the case never presented itself. The gun depression was −3° and 30° elevation, firing a 3,320-pound (1,510 kg), AP capped shell at 2,270 ft/s (690 m/s). Range was 28,900 yards (26,400 m). The rate of fire was one round per minute, with sixty rounds in store. The turret mass was 826 long tons (839 t), to compare to the 810 long tons twin gun model of the Glorious class, so barely any changes had on be made on the structure around the barbette.

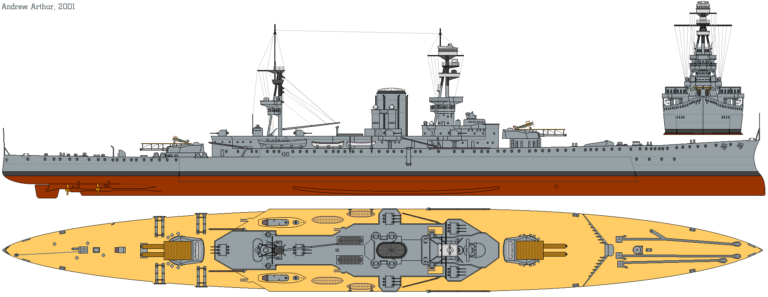

Profile of HMS Glorious in 1917 by Andrew Arthur. The Furious was very similar with the difference of her massive guns.

Her secondary armament comprised, as said above, two 11 BL 5.5-inch Mk I guns which can elevate to 25° on their pivot mounts and fire a 82-pound (37 kg) shell at 2,790 ft/s (850 m/s) with 12 RPM. Range was 16,000 yd (15,000 m) at 25°. The guns were there to provide cover fire in case of destroyers broke in its torpedo range. Common to all three ships were two QF 3 inch 20 cwt AA artillery pieces with single high-angle Mark II mountings abreast the mainmast (Courageous-class) or before the funnel on Furious. Maximum elevation was 90° and they fired a 12.5-pound (5.7 kg) shell at 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s). RPM was 12–14 rounds per minute. The ceiling was 23,500 ft (7,200 m). Two 21-inch (533 mm) submerged broadside torpedo tubes were also mounted near ‘A’ turret, loaded and traversed by hydraulic power, with ten in store.

The main armament was served by two fire-control directors Barr & Stoud, one mounted above the conning tower and the other in the fore-top on the foremast. The secondary turret had their own 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinder in the roof’s armoured housing. There was a torpedo control tower at the rear. The AA guns were assisted by a single 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) rangefinder on the aft superstructure.

Propulsion

How to be a 23,000 tons blazing fast ship in 1917: The use of geared steam turbines combined with small-tube boilers was unique and very innovative among British ships. This saved weight a great deal, at the expense of heavier maintenance requirements. To save time in design, engineers simply adopted the light cruiser Champion’s installation and doubled it. The Parsons turbines had each their engine room, each driving one of the four propeller shafts, 11 feet 6 inches (3.5 m) in diameter. Eighteen Yarrow boilers provided steam into three boiler rooms and were designed to produce a total of 90,000 shaft horsepower (67,113 kW). Working pressure was 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kg/cm2).

Furious powerplant rating was a little better that during Glorious’s trials, but without reaching the designed speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph). 750 long tons (762 t) of fuel oil were carried, up to 3,160 long tons (3,211 t) in wartime, and at that capacity, estimated range was 6,000 nautical miles (11,110 km; 6,900 mi) at 20 knots. In any case 32 knots for 23,000 tons was unheard of at that time, and will be only surpassed by the late 1930s super-dreadnoughts.

A symbolic protection

Far away from the excellent protection given to the adverse German battlecruisers (especially the Hindenburg), the Glorious class protection was strictly limited to a multiplication of light steel walls in many areas. But it was made from high-tensile steel, which was usually only used structurally in warships. The waterline belt had two successive layers 2 inches (51 mm) thick covered by a 1-inch (25 mm) skin, extending from barbette to barbette.

It was then reduced to one-inch forward bulkhead, short of the bow. This belt was 23 feet (7.0 m), of which 18 inches (0.5 m) below the waterline. The forward barbette front was protected by a 3-inch (76 mm) bulkhead located around the upper and lower decks, same for the rear barbette as well. They were also four armoured decks with successive thicknesses from 3 inches to 0.75 inches (76 to 19 mm). it was 3 in over the magazines and steering gear. The design was revised after Jutland, and 110 long tons (112 t) of extra protection were added to the deck around the magazines.

Krupp cemented armour protected the turrets, barbettes and conning tower. The former were 9 inches (229 mm) thick, 7 to 9 inches (178 to 229 mm) on the sides, 4.5 inches (114 mm) on the roof. The barbettes varied from 6 to 7 inches (152 to 178 mm) above the main deck down to 3-4 in down to the lower deck. The conning tower’s thickness was 10 inches (254 mm) with a 3-inch roof. The primary fire-control director frontal areas was protected by 6-in, 2 in on the sides and 3 in on the roof. The communications tube was 3 in. The torpedo bulkheads as planned were .75 in (19 mm) but this was revised to 1.5 in (38 mm).

For ASW protection, shallow anti-torpedo bulge were made integral to the hull, acting like a space armor for torpedoes but they were short and lacked additional layers alternating empty and full compartments to do their job correctly. If Glorious was sunk by gunfire off Norway, HMS Courageous was sunk by two torpedoes on 17 September 1939, by U-29, the first major british warship lost in WW2.

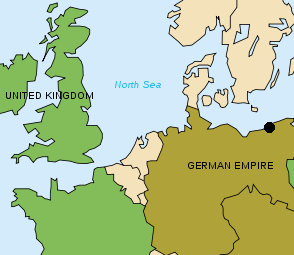

About the Baltic Project

This pet project, dear to Fisher was designed to speed up Germany’s defeat. It involved landing a substantial force, of British or Russian soldiers on Pomerania’s beaches (North German, Baltic coast) about 100 miles from Berlin. The assumption was the force was enough to carve its way to Berlin without any serious any opposition since the bulk of the Army was mobilized hundreds of miles away in France and Belgium. A specialist fleet was tailored to fit the bill, and the landings were to be preceded by minefields and posted Submarines to protect its flanks. More than 600 specialized vessels were required like landing craft, assisted by minesweepers, destroyers, light cruisers, monitors, and heavy shallow draft ships able to assist the monitors and repel possible relieving forces, in the shape of these three “battlecruisers” of the Courageous class. The plan was never realized. Note the German aviation was completely absent for this schemes. But in a sense, Furious would have its share of coastal operations later.

Admiral John Fisher

The Baltic Project alone motivated such design. Admiral Fisher jumped with enthusiasm over his new pet project writing to the DNC on 16 March 1915: “I’ve told the First Lord that the more that I consider the qualities of your design of the Big Light Battle Cruisers, the more that I am impressed by its exceeding excellence and simplicity—all the three vital requisites of gunpower, speed and draught so well balanced!“. Again, speed was the decisive factor in Fisher’s view. This was before Jutland… Already he made this clear when he wrote to Churchill for the 1912–13 Naval Estimates “There must be a sacrifice of armour… and further VERY GREAT INCREASE IN SPEED… to vastly exceed your possible enemy!”. The shallow draught was meant for the operation area, but not entirely. They were to operated close to deep load and were criticized for a detected low freeboard, reserve buoyancy and inadequate ASW protection. The DNC had to redesign the hull to rectify these issues and re-evaluate the whole design. For more about Fisher’s view on Furious and these cruisers, see his memoirs, 99, Jeu d’esprit

Nothing to do with the project, but this postwar British Pathé footage of HMS Eagle just built shows how operated the light biplanes of that era

HMS Furious conversion

On March 19, 1917, the admiralty had decided the fate of the third battlecruiser. Later in 1918, the cruiser HMS Cavendish also under construction was also converted and renamed Vindictive, to test the practicality of flying off and retrieving planes from a smaller ship. This would allow the Admiralty to judge which platform was best for future conversions or new constructions.

HMS Furious has been designed as a modified Glorious class BC, laid up at Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick on 8 June 1915, launched 18 August 1916, completed in 26 June 1917 and Taken in hands for a conversion to an aircraft carrier in November 1917, several month after her service as a modified hybrid battlecruiser (partially converted). However she was only officially reclassified as an aircraft carrier in September 1925. Between 1917 and 1925 she underwent a serie of modifications we are about to see:

HMS Furious first conversion

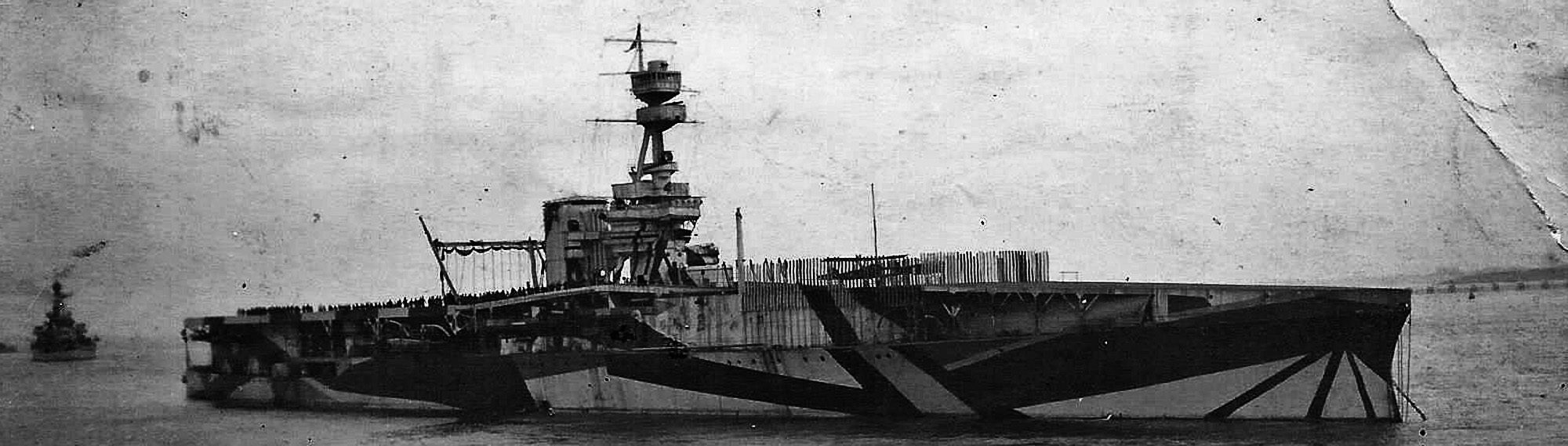

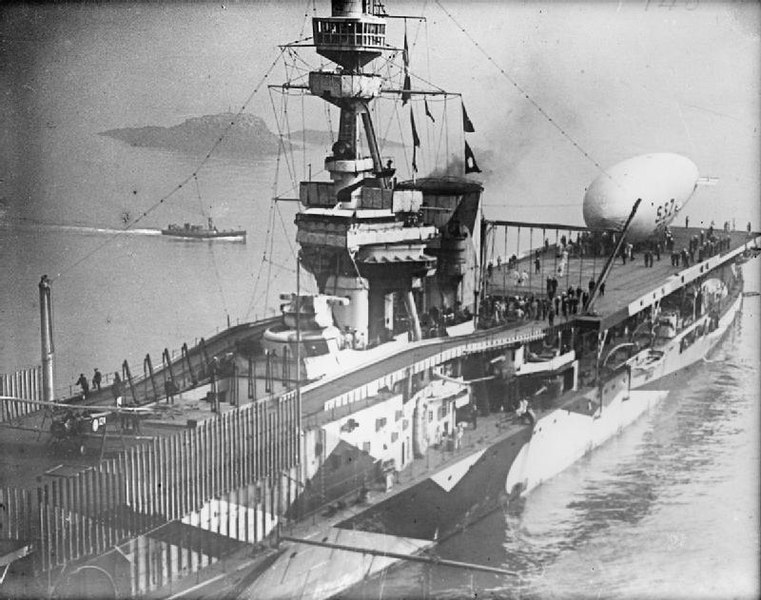

HMS Furious in 1918, for the operation on Tondern, with a SSZ blimp onboard – IMW

Indeed as she was built already, a large hangar capable of housing ten aircraft on her forecastle was added, replacing the forward turret. That was a crucial move reflected by the evolution of the Baltic Operation (yet not cancelled). Over this superstructure a 160-foot (49 m) flight deck was created. Short turret-based take-off platforms has been created and already tested on several battleships, but in that case aircraft could also landed on this deck.

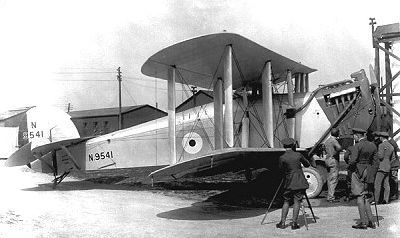

These were not pure aircraft but Short Type 184 floatplanes that took off by safety. They used a four-wheel trolley running along a central flight deck trench. In addition, there was a crane to carry these from the hangar to the flight deck. The trials involved firing the massive aft gun at sea, but after a while it was decided to start a new array of modifications.

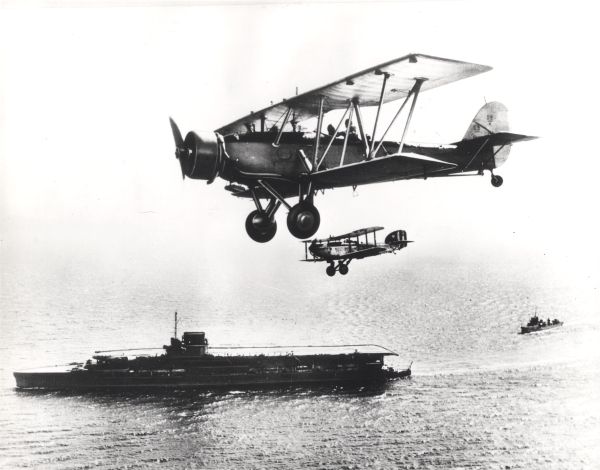

During extensive tests in the summer of 1917, Squadron Commander Edwin Dunning landed a Sopwith Pup on the Furious, the world first ever attempt of this kind. Another landing followed in August, but on the third attempt the ship claimed her first victim, as the engine choked and the aircraft crashed off the starboard bow. This showed grave deck arrangement limitations and motivated a redesign. Indeed, the pilot each time had to manoeuver to avoid the superstructure.

While all three Courageous-class battlecruisers joined the 1st Cruiser Squadron (CS) in October 1917, the on 16, Admiral Beatty ordered Furious to search German ships along the 56th parallel and return before dark while her sisters reinforced the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, deployed on the central North Sea sector the day after. despite they failed to catch any German ships, their speed gave all satisfaction.

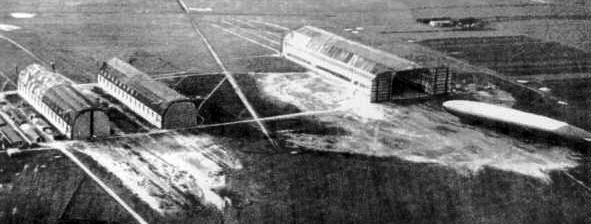

Furious returned to the dockyard in November to have the aft turret removed and replaced by another deck for landing, giving her both a launching and a recovery deck. Two lifts (elevators) serving the hangars were also installed. Furious was recommissioned on 15 March 1918, and her embarked aircraft were used on anti-Zeppelin patrols in the North Sea after May. In July 1918, she flew off seven Sopwith Camels which participated in the Tondern raid, attacking the Zeppelin sheds there with moderate success

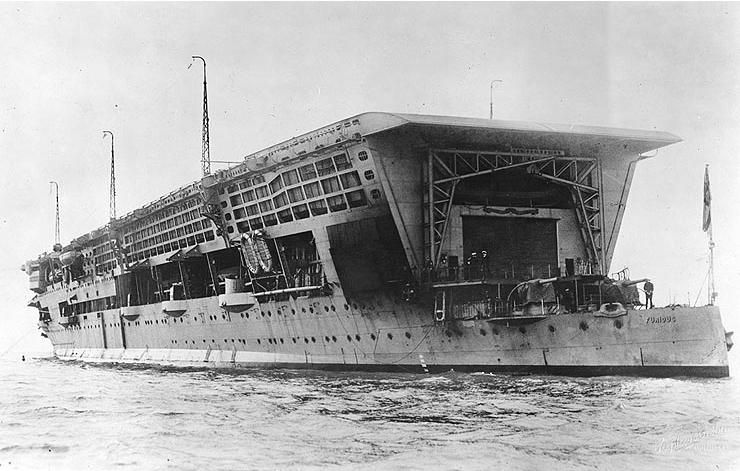

November 1917 full conversion

In November 1917 while it was clear the Baltic plan was abandoned, the rear turret of the Furious was in turn deposed, and replaced by a 300-foot (91 m) deck over another hangar. Now only the central superstructure and funnel emerged from this new construction, splitting the ship in two. To move from one deck to the other, a narrow strip of decking was fitted around the superstructures.

On trial, it was shown that turbulence from the funnel and the superstructure were so severe as to forbid landing attempts, after three hazardous tests. The 18-inch guns were reused on Lord Clive-class monitors and did see extensive service on the Flanders coast. HMS Furious deployed her aircraft on anti-Zeppelin patrols in the North Sea from May 1918 and in July, she flew off seven Sopwith Camels for the the Tondern raid, which knew a moderate success. The war ended after other patrols and the ship was finally laid up in 1922, waiting for her fate. She was to be rebuilt quite extensively, and that would be her third life.

The Raid on Tondern (19 July 1918)

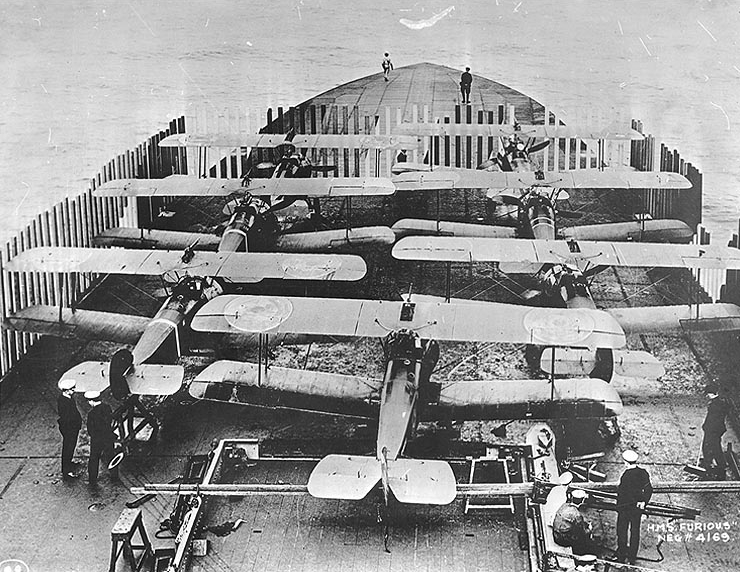

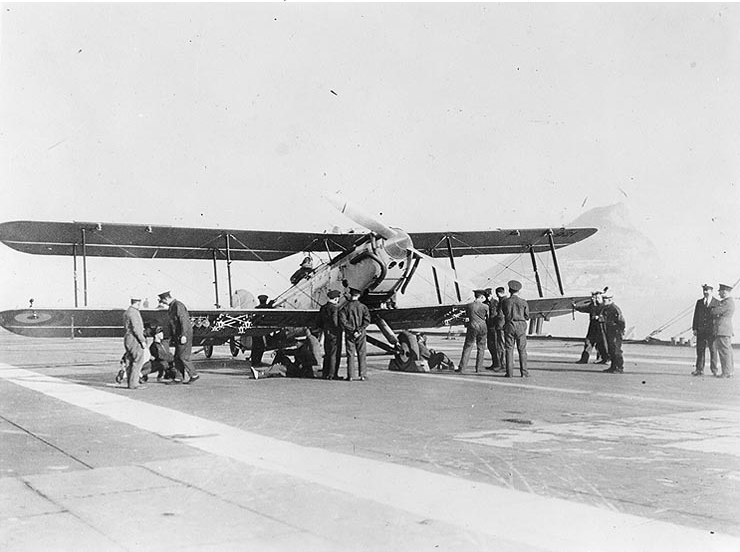

Sopwith Camels stacked in front of HMS Furious in preparation for Tondern raid

The fame of HMS Furious really came from this raid, which was the first attack by land-based airplanes from a tailored ship, an aircraft carrier. After North sea patrols against reconnaissance Zeppelins, she was prepared for an operation that would have been inconceivable at the beginning of the war: Attacking a coastal base on the doorsteps of Germany, literally under the nose of the Hochseeflotte. For this, only a few ships were able to get there and depart from there with blazing speed, bringing a substantial attack force of potent fighters. By the time she was chosen for an attack on the German Zeppelin base, the German Naval Airship Division of Tondern (Denmark), she headed the mark of Rear-Admiral Commanding Aircraft, R. F. Phillimore. She has trained with Sopwith 1-1/2 Strutter until then, good planes but already obsolete and slow in 1917; She was then equipped with the brand new Sopwith Camel 2F.1a, a navalized version of the excellent Camel, and one of the first navalized fighter ever. With this squadron she was constantly on the lookup off the Heligoland Bight, searching for minefields.

The attack was the brainchild of two RAF officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Clark-Hall and Squadron Commander Richard Bell-Davies. The plan was approved by David Beatty and get the greenlight. Operation F.6 was mounted in may and in June training began, in order to launch two waves of four aircraft on the base. Training consisted of bombing runs on the airfield at Turnhouse. On 27 June Furious departed from Rosyth, escorted by the First Light Cruiser Squadron and eight destroyers from the 13th Flotilla. All these ships could reach 30 knots, in order to quickly approach the launching zone and depart. However conditions were atrocious with Force 6 gale winds and the operation was cancelled.

Operation F.7 had a fresh start on July, 17. This time Furious was escorted by “Force B”, with a division of the First Battle Squadron, Revenge-class battleships, Seventh Light Cruiser Squadron, and a destroyer screen. The Battleships just received special shrapnel 381 mm ammunition tailored to cripple any airship. The launching was to star at 03:04 on 18 July, but a sudden thunderstorm aborted the attempt. It was decided to let the fleet stay there for 22 hours and attempt it again. For this, Furious, which has been detached, came back to Force B left at the rear. She came back during the night and about the same hour, despite worsening conditions, the launch started. At 03:21 all the Camels had taken off and they reached the coast at 04:35. For the Germans it was a complete surprise, so far from the Western front.

Immediately the three airship sheds (Toska, Tobias, Toni) were targeted with incendiary bombs, Toska was badly hit and L.54 and L.60 burned, Tobias too, one airship badly damaged also by fire, but the planes also had many near-misses, trying to set ablaze a wagon loaded with hydrogen. The Germans eventually suffered only four men injured and Toska was later repaired but the base was later abandoned as too vulnerable. On the British side, there was one missing, presumably drowned. Due to fuel exhaustion, two Camels ditched while attempting to return, and three landed in Denmark. That was Britain’s own “Doolittle raid” in WW1.

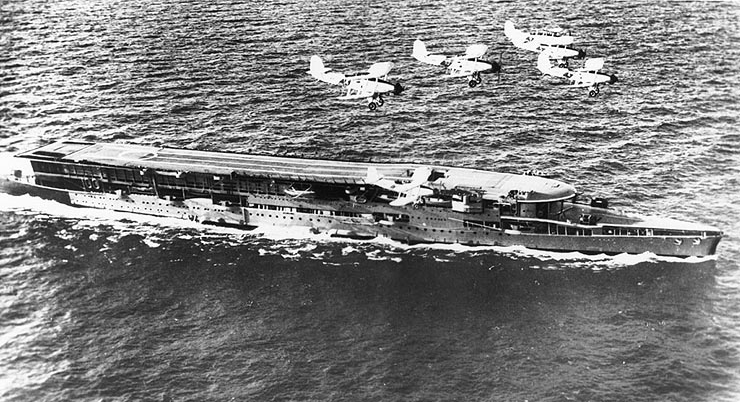

Interwar conversion as a true aircraft carrier

A new reconstruction started between June 1921 and September 1925. Engineers which draw the blueprints capitalized on the design experience gained with the first Argus and Eagle completed and tested before. Nevertheless this was still a relatively experimental design. Everything was razed above the main deck, and over this clean based, a 576 x 92 feet flight deck was built (175.6 x 28.0 m). This was however, only three-quarters of her overall length, and not level, sloping upwards 3/4 of the prow from the stern. This feature was tried to slow down landing aircraft. There were of course a 97.5 m arresting gear only there to prevent aircraft from veering off to either side. Biplanes were so light at that time that they did not even need a proper arresting hook. A wind tunnel at the National Physical Laboratory tested various flight deck shapes which ended as elliptical with rounded edges. This was to reduce turbulence in most wind conditions.

Dunning landing on HMS Furious on a Sopwith Pup

The hull’s beam was increased just 1 foot (0.3 m) and the draught increased draught to 27 feet 3 inches (8.3 m), fully loaded, 2 feet (0.6 m) deeper. Displacement rose to 26,500 long tons fully loaded, some 3000 more. Metacentric height was just 3.6 feet (1.1 m), better than the original ship, making her more stable for landing and planes taking off. Final speed after conversion as tested was down to 30.03 knots (55.62 km/h; 34.56 mph) which she carried 700 long tons (710 t) more fuel, for 5,300 nautical miles (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). For the exhaust not empeding operations, the boilers exhaust tubes were ducted to the side and through gratings at the rear of the flight deck. However the solution was soon recognized at fault.

She carried her complement of planes into a single two-level hangar under the flight deck. Each level’s ceiling was 15 feet (4.6 m). The lower hangar was slightly longer at 550 feet (167.6 m) versus 520 by (158.5 m). Electric power was independent for both sections, and ventilation procured by large steel shutters on rollers. The flying-off deck was still used to launch small planes light fighters while other landed simultaneously. But some can also fly from the lower deck as well. There was no proper island superstructure and so turbulence over the flight deck was reduced. A navigating “bathtub” however was fitted to the leading edge of the flight deck, at starboard. There was also a retractable charthouse forward, on the centreline.

Overall, she could carry 36 aircraft in normal operation, much more when carrying planes on her flight deck for one-off missions. Two 14 m squared elevators were created to lift aircraft from both hangars. Two 600 gallon (2,700 l) ready-use petrol tanks were installed to supply the aircraft on the upper deck. Much more were stored in bulk storage inside the ship.

HMS Furious after her second refit in 1918 – colored by Hirootoko Jr.

Due to her very long career, from 1917 to 1945, HMS Furious operated most Royal Navy and RNAS types. In 1917 she flew Sopwith Camel and Pups. in 1920s she flew the Fairey III multipurpose aircraft. This was a legend, introduced on 14 September 1917, and which served until 1941! From 1931 she flew the Fairey Gordon and probably also from 1933 the Fairey Seal, which lineage gave the Swordfish.

In 1938, there were still Hawker sea fury fighters and Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, both biplanes, but the former were replaced by Hawker Sea Hurricanes From July 1941. HMS Glorious still had in late 1940 18 Sea Gladiators from 802 Naval Air Squadron which fought during the battle of Britain.

Furious kept 10 (out of 11) 5.5-inch (140 mm) guns, each side for close defence but her old AA guns were replaced by 6 QF 4-inch Mark V guns, mounted each side of the flying-off deck, two more on the quarterdeck. The first four were deposed in 1926–27 for trials, but only two were mounted again. However the addition of four single QF 2-pounder “pom-poms” in 1927 was more significant. In 1930-1932 refit, 2×8 QF 2-pounder Mark V pom-pom were added, replacing the old 4-inch guns remaining (still those of the quarterdeck remained), and during the second refit in 1939, a dozen QF 4-inch Mk XVI guns in six twin dual-purpose Mark XIX mounts were fitted to the ship.

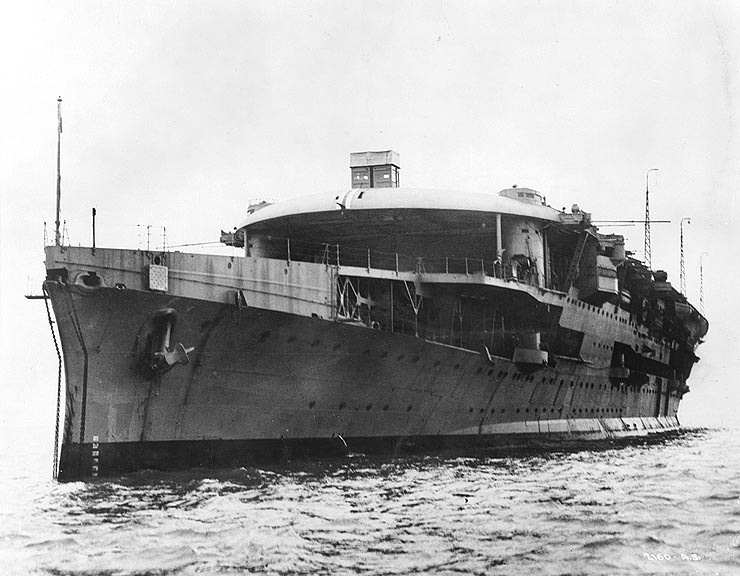

HMS Furious prow in 1925

HMS Furious stern in 1925, after reconstruction.

They landed either on the flying-off deck and quarterdeck. Four were mounted on sides platforms and two 2-pounder fore and aft of the new island superstructure. With her last refit in 1943 in the United States, Furious received the usual AA arsenal of twenty-two single 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon AA guns while a quadruple Vickers .50 machine gun mount was removed. All these guns were directed from a High Angle Control System on the island and another on an elevated mount on which was previously the flying-off deck. Pom-pom (40 mm Bofors) directors were also mounted on the island, fore and aft.

HMS Furious during the interwar

In between the refits signalled above, HMS Furious served from 1925 with the Fleet Air Arm, conducting trials with every planes models in service, and a usual complement of Fairey IIID torpedo-bombers and Fairey Flycatcher fighters. Some were equipped with floats and many configurations were tested, like skids, a greased lower flight deck, while the arresting gear was seldom used and later removed. Deck-edge palisades were also installed in 1927 to guard planes from falling. The world’s first night landing was performed by a Blackburn Dart on 6 May 1926. At that time the usual operational complement comprised four aircraft types: A Flycatcher fighter squadron, a spotter squadron made of Blackburn Blackburn or Avro Bison, and a reconnaissance squadron of Fairey IIID and two squadrons of six torpedo bombers Blackburn Dart.

BlackBurn Dart (1923)

BlackBurn Shark (1934)

On 1 July 1930 HMS Furious went to reserve for a comprehensive reconstruction, which had to wait until September when the drydock was available and blueprints ready at Devonport. She ran her trials on 16 February 1932, but due to the additional weight she was given top speed was around 28 knots. She was partially recommissioned on May 1932 with the Home Fleet, and detached to the Mediterranean Fleet (May-October 1934) before returing for the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead on 20 May 1937. Additional modifications were performed at Devonport from December 1937 until May 1938. Sh operated then the 801 Squadron composed of six Hawker Nimrod and three Hawker Osprey fighters, just replacing the old Flycatchers plus the 811 and 822 recce Squadrons using a mixture of Blackbrun Ripon and Baffin, Fairey IIID and Swordfish plus Fairey Seal and Blackburn Shark for reconnaissance, still a main mission for aircraft carriers at that time.

Fairey Flycatcher

Fairey IIID on HMS Furious. In October 1939 she was used a a training carrier, with a new aicraft complement on board, the 767 Squadron (flying Shark, Swordfish, Fairey Albacore TBs) 769 Squadron (Blackburn Skua, Roc, Gloster Sea Gladiator fighters).

HMS Furious in the late 1920s.

HMS Furious during WW2

The atlantic

She was quickly sent, on her return from refit in May 1939, in operations in the Atlantic as an advanced training carrier, with a fleet of Blackburn Shark, Fairey Swordfish and Fairey Albacore, then an air complement in October 1939, including a complement of Sea Gladiator fighters, Blakburn Skua and Blackburn Roc. She replaced the Courageous after her loss in the Home Fleet, then took part in patrols and hunts in the North Sea, notably to intercept the KMS Gneisenau and other German ships in the company of Ark Royal. She also used to operate from Halifax, Nova Scotia, with the battlecruiser Repulse to hunt on the northern route. On 17 December, she collided in the darkness with SS Samaria, but without gravity. That was her second collision, the first occurring with a destroyer before the war.

HMS Furious in August 1941, showing her deck camouflage

The campaign of Norway

From April to June 1940, HMS Furious commanded by Captain Troubridge was actively involved during the Norwegian campaign. Due to the sudden German presence in Norway she was despatched in a hurry on 10 April 1940 with only eighteen Swordfish from 816 and 818 Squadrons. Upon arrival, pilots desperately torpedo attacked German ships in Trondheim, with no success. On 12 April, an attack was made on Narvik but also bad weather prevented any hit. Swordfish were re-equipped with bombs and managed to sink several captured Norwegian ships with two losses due to FLAK. Another support combined attack went out badly with two more losses several days later. She departed on 15 April for Tromsø and her Swordfish biplanes managed to damage and force to land several Ju-52 along the way. She was attacked by a single Heinkel He 111 bomber from II./KG 26, took two-near missed that jarred the port inner high-pressure turbine and despite the damage and a top speed down to 20 knots, during several days she patrolled in the area, menacing German supplies.

She went to Harstad when the weather was deteriorating to assess the damage, which was so severe that she was sent back home for repairs and returned to Norway on 18 May. She carried Gladiators of a reformed Royal Air Force 263 Squadron to be based in Norway and later ferried another squadron. She was sent also for Halifax on 14 June, carrying £18,000,000 in gold bullion. After ferrying troops she was also used to transport back to UK 50 planes and equipment, plus large quantities of sugar by the captain’s initiative. Shen then operated from Tromsø in September and October 1940 with three squadrons, loosing several planes.

The mediterranean

Leaving Liverpool in November, she went to deliver 40 crated Hurricanes to the Takoradi base in Cote d’Or (East Africa), then to Egypt. This ferry role continued during the years 1941 and 1942, as well as an escort job. On 21 December she joined Convoy WS5A and teamed with HMS Argus. Her planes attacked the German cruiser Hipper, but without success. She made other attempts, compromised by bad weather, and returned for an additional ferry trip to Takoradi on 4 March. She would also carried 24 Hurricanes to Gibraltar on 25 April, which flew to join HMS Ark Royal. Back home she was damaged at Belfast during a German air raid in early May 1942. Dhe also teamed with Ark Royal and the two carriers to deliver more planes, south of Sardinia or Sicily, sometimes with mixed success (many crashes).

In between she returned home to carry 817 Squadron, gathering at Seidisfjord, Iceland in order to attack the German-occupied ports of Kirkenes, Norway, and Petsamo, Finland. The attack took place on 30 July and the planes were able to damage and sink several ships. On 30 August she departed again for Gibraltar ferrying many planes. This was a bait to divert attention from the axis while the invasion of Sicily was planned.

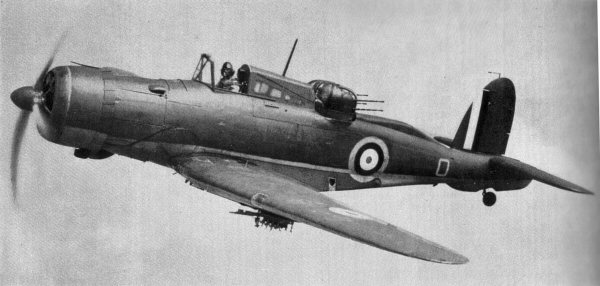

During the supply operations of Malta, the Furious participated in Operation Pedestal and the Second Battle of Greater Sirte. During Operation Torch in November 1942, the Furious covered the landings with a Squadron from Supermarine Seafire and Fairey Albacore. Still with Gibraltar-based H force, HMS Furious served as a prelude to Operation Husky (landing in Sicily) in February 1943.

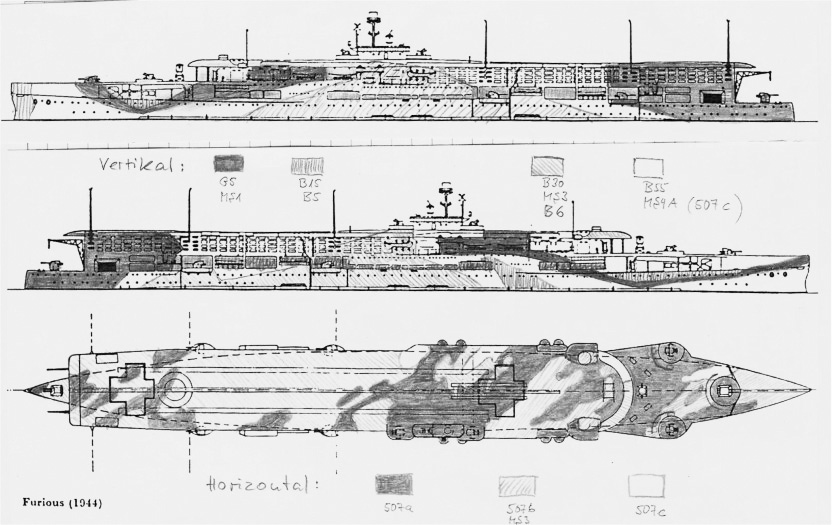

Camouflage scheme in 1942

The far north

Blackburn Skua

Blackbrun Roc

Hawker sea Hurricane

During Operation Tungsten (the attack on Tirpitz), Furious and Victorious used cross-trained Barracuda squadrons escorted by Seafire fighters. On 3 April 1944 they managed complete victory and hit the German battleship six times for one loss. Tirpitz was under repair for three months, not menacing the northern route convoys bound to Murmansk.

She carried out also several raids against German bases assigned to attack convoys to Murmansk. She took part in the dangerous attacks against the Tirpitz through Operation Mascot and Operation Goodwood, the latest naval air raids against the German battleship at anchor. During operation Mascot in June 1944 she teamed up with Formidable and Indefatigable and launched her heavily loaded Barracudas with bombs of up to 1,600-pound (730 kg) on wooden ramps. But at each raid, the Tirpitz was ready and laid a thick smoke blanket therefoe the planes operated in the blind. On 22 August another attack suffered 11 losses for just one hit with a penetrating bomb that did not detonated.

830 squadron’s Barracuda taking off during Operation Mscot 17 July 1944.

The end

She then retired to resume her former role as a training ship in home waters. In September 1944, given her age and hull fatigue, it was decided to place her in reserve. In April 1945, she was written off, used for explosive tests in the Loch striven, and later sold to scrap dealers in 1948 but only dismantled in 1954. By that time her keel has been laid in 1915, in a completely different world and for a completely different purpose. She would remain forever, the world’s first aircraft carrier.

Supermarine Seafire on HMS Furious in August 1944

HMS Furious (1917) |

|

| Dimensions | 239.8 x26.8 m x7.6 m (786 ft 9 in x 88 ft x 24 ft 11 in) |

| Displacement | 19,513 long tons (19,826 t) standard, 22,890 long tons (23,257 t) FL |

| Crew | 737 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts, 4 geared steam turbines, 18 Yarrow small-tube boilers |

| Speed | 31.5 knots (58.3 km/h; 36.2 mph) |

| Armor | Belt: 2–3 in (51–76 mm), Decks: .75–3 in (19–76 mm), Barbettes: 3–7 in (76–178 mm), Turrets: 7–9 in (178–229 mm), Conning tower: 10 in (254 mm), Torpedo bulkheads: 1–1.5 in (25–38 mm) |

| Armament | 2 × 18-inch (457 mm), 11 × 5.5-inch (140 mm), 2x QF 3-inch (76 mm) 20 cwt AA, 2 × 21 in (533 mm)TT* |

*Later addition removal of front 18 in gun, 6-8 aircrafts.

HMS Furious (1925-39) |

|

| Dimensions | 239.70 m long, 27.4 m wide (flight deck), 8.6 m draft (full load). |

| Displacement | 22,450 t. standard – 27 170 t. Full Load |

| Crew | 791 |

| Propulsion | 4 propellers, 4 Parsons turbines, 18 Yarrow boilers, 90,000 hp. |

| Speed | Top speed 30 knots, 4500 nautical RA at 16 knots. |

| Armor | Belt, decks 76 mm |

| Armament | 12 x 102 mm, 24 x 40 mm MK VI AA, 16 x cal.0.4 (4×4) (later 8, 25, 30 x 20 mm Oerlikon AA) |

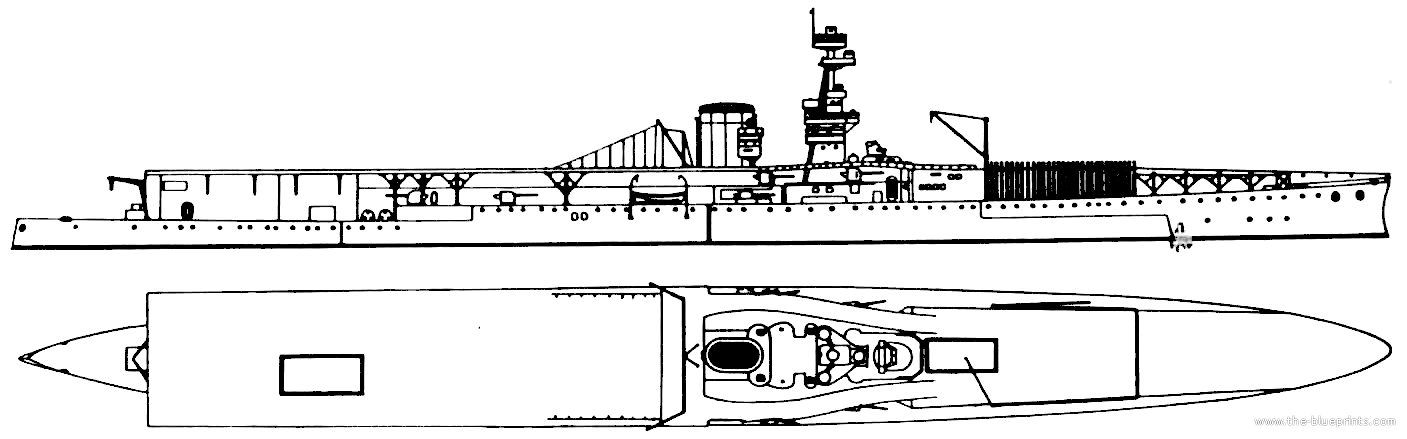

Author’s profile of the Furious in 1918

Author’s profile of the Furious after reconstruction in 1942

Links – Read More

HMS Furious on wikipedia

On naval-history.net

On hazegray.org

On 2db.com

On uboat.net

On militaryfactory.com

On historyofwar.org

Fleet Air Arm

List of carrier-based aircraft

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-1921

The Tondern raid documentary

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

This is fascinating. I am teaching WW1 in a school and managed to acquire a tea caddy spoon from HMS Furious and some postcards from the trenches. I will be using this information as part of my lesson this week. Thank you so much. A fabulous look at Naval history.

Thanks Rhonda for your feedback !

My late father, James Sidney Litchfield

(b. 12/09/1915 d. 11/10/2011) was an Engine Room Artificer on HMS Furious on Arctic Convoys to Murmansk, including attacks on the Tirpitz.

I would dearly love to acquire any Furious memorabilia. Likewise an FAA Sweetheart Brooch. Any information, name of the captain etc would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks for your input Keith ! Have nothing of that sort but you’ll find a captain”s list at https://uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/3253.html

Cheers

David

Thanks for this article, it was a fascinating read. I live a couple of miles away from Loch Striven and had been unaware that she was there! Hopefully I’ll be able to find some images of her there.

Thanks,

Derek

Thanks Derek !

Well, if you find some, feel free to post them there in the comment section if authorized; that would be great addition.

David

My Great Grandad Served on the Furious, I have a picture of him in uniform if you would be interested. Walter Ledger, Born 1901

Hi Kevin, absolutely, feel free to send it to [email protected], i can publish it in the current article with the legend of your choice. Thanks !

My father served on Furious from 25th July 42 until 18th Oct 44 as a cook. I’m so proud to read about his ship and am for ever grateful for all those who gave so much in WWII, and before and since.

Thanks for your comment. This ship is indeed iconic and the whole crew made history, literally.

My Grandfather served on the Furious in WW2, not sure what he done but i know he was a cook on the Killicrankie, i’ll post a couple pictures i have if that’s ok

Thx Paul for the info, please do so, it’s always useful !