Russian cruiser Novik (1898)

Russian Empire – Protected Cruiser

Russian Empire – Protected Cruiser

A German built cruiser with two lives:

The Imperial Russian navy Novik was ordered part of a program intended to boost the newly formed Pacific Fleet. The admiralty wanted a 3000-ton class scout cruiser. Since no yard had experience yet in this field, foreign shipbuilders were submitted a tender, and designs were reviewed. The admiralty eventually settled on German shipbuilder Schichau-Werke, usually a specialist in the construction of torpedo-boats.

The Imperial Russian navy Novik was ordered part of a program intended to boost the newly formed Pacific Fleet. The admiralty wanted a 3000-ton class scout cruiser. Since no yard had experience yet in this field, foreign shipbuilders were submitted a tender, and designs were reviewed. The admiralty eventually settled on German shipbuilder Schichau-Werke, usually a specialist in the construction of torpedo-boats.

Novik (named after a medieval term for a “noob”, teenager of a noble family, boyar or cossack enlisted or in an Opolchenie) was launched on 2 August 1900. Her sea trials started on 2 May 1901 in Germany and some vibration problems were identified. The problem was fixed and testing ended on 23 April 1902 after five runs made at around 25.08 knots. Therefore Novik became one of the few fastest cruisers in the world, impressing the Russian naval leadership enough that they would copy the concept and built close ships, the Izumrud and Jemtchug.

Soon after her arrival in the pacific fleet, war broke out with Japan. She surrendered at the battle of Tsushima and was captured. After some modifications she would serve as IJN Suzuya, and sold for scrap 1 April 1913, so she don’t even participated in the great war, but is mentioned here because of the Izmurud class.

context of the order

The Russian Main Naval Headquarter’s operational-tactical task (OTZ) studied the design of a “small” cruiser for the Pacific Theater in 1895. It started right after the degratation of relations with Japan, but since 1882, the concept of a “small” cruiser for the Russian Navy has been rejected since yards concentrated in medium to large cruisers to face by then the most likely foe, the Royal Navy. In addition the admiralty was aware of small cruisers shortcomings, short range and unsatisfactory seaworthiness, plus unstable artillery platform in heavy weather.

It’s Armstrong large-scale exports of successful “small” Elswick type cruisers started to make the Russian admiralty change its mind, especially after their actions during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894. Inexpensive, yet well-armed, they complied Pacific Theater conditions and fir the Russian needs. After 1894, Japan had a clear cut numerical superiority in light cruisers and destroyers in this area, with a large Shipbuilding Program to match.

Therefore in May 1895, Vice Admiral S.O. Makarov organized a meeting at Chifu, and substantiated the concept of a universal light cruiser concept inspired by Elstwick’s J. Rendel, with the Esmeralda, a 2800 tons, heavily armed ships tailored for the Far East Theater and ancestor of the export “Elswick type”. Later Izumi was described by Makarov as an “ideal combat ship” close to his universal armored “small” cruiser up to 3000 tons with a speed of 20 knots, two 8-in, four 6-in and twelve 3-in. It was even more suitable during times of financial constraints and for serial construction able to shift balance of power in the pacific.

Therefore in May 1895, Vice Admiral S.O. Makarov organized a meeting at Chifu, and substantiated the concept of a universal light cruiser concept inspired by Elstwick’s J. Rendel, with the Esmeralda, a 2800 tons, heavily armed ships tailored for the Far East Theater and ancestor of the export “Elswick type”. Later Izumi was described by Makarov as an “ideal combat ship” close to his universal armored “small” cruiser up to 3000 tons with a speed of 20 knots, two 8-in, four 6-in and twelve 3-in. It was even more suitable during times of financial constraints and for serial construction able to shift balance of power in the pacific.

However Makaroff also strongly opposed the increase in speed to the detriment of artillery, high speed being not so important for long-range reconnaissance as situation changes too quickly and preferring destroyers for the task. For him a squadron of armored cruiser was perfectly able to resist both destroyers and light cruisers, with superior speed and manoeuvrability, if necessary to encounter a squadron of battleships and survive. From November 1895 to December 1897 other meetings saw the confirmation of a suitable design for the Pacific and soon resorted the need of a small reconnaissance cruiser of 2000-3000 tons. Taking account of financial constraints and operational and tactical features for this theatre, that new type of small cruisers could replace obsolete gunboats and counteract Japanese destroyers.

Design development and tender

By December 12-18, 1897, the Pacific cruiser design was first drafted: Vice-Admiral I.M. Dikov proposed that each squadron of battleship to be screened by one reconnaissance cruiser and a destroyer. The main quality pointed out was to be speed, allowing the rest to be sacrificed, contradicting Makaroff’s concept of a “universal armored vessel”, but it was accepted to form the basis for the development of Pacific cruiser design.

Vice Admiral E.I. Alekseev had the experience of commanding a squadron in the Pacific and asked to increase the number of cruisers, arguing for eight armored cruisers of 5000-6000 tons, plus four reconnaissance cruiser of 3,000-3,500 tons and four more of 1,500 tons.

Taks defined were to serve as screens, advanced scouts, squadron dispatch vessels or to operate separately, but also surveying, and coastal reconnaissance. Vice Admiral N. I. Skrydlov wanted some for a squadron of Peresvet type battleships, the “troika” accompanied each by a reconnaissance cruiser and three squadrons meant at least 9 units in the Pacific Theater.

By December 1897, a meeting was held by Admiral General P.P. Tyrtov, managing director of the Maritime Ministry, N.I. Kaznakov, V.P. Verkhovsky, I.M.Dikov, S.P. Tyrtova, S.O. Makarov, F.K. Avelan and E.I. Alekseev. It was decided to built two squadrons of three battleships instead of 10 small scouts. In March 1898, the Maritime Technical Committee (MTK) designed a 2nd class cruiser, with a fixed displacement of 3000 tons, 360 tons of coal, 5000 miles rage at 10 knots, 25 knots in top speed and armed with six 120 mm, six 47 mm guns and a single Baranovsky AA gun; plus 12 torpedoes, and 25-30 mines and an armored deck. The document was approved by the ITC Chairman Vice-Admiral I. M. Dikov and chief inspectors while in parallel another program for a 30-knots cruiser was also launched. The general document was however confusing and contradictory. The tender was submitted to German, English, Italian, French, American and Danish yards and specs were quite demanding.

Finalized design

Hovaldtswerke (Kiel), F. Shichau & Krupp andswered the call in Germany, London-Glasgow Engineering & Iron Shipbuilding Co, Laird, Ansaldo in Italy and Chantier de la Gironde in France, Burmeister og Vine in denmark also were contacted, while in Russia, Nevsky Shipyard provided technical assistance with British yards. The announced winner was Hovaldtswerke, Kiel, on April 10, 1898, and also a “30-knot” design. The German blueprints defined a hull of 103.63 m, 12.8 m beam, and 4.88 m draft, two vertical triple-expansion steam engines with a capacity of 9,000 liters and Thornycroft water tube boilers. It was calculated the ship needed 25,000 liters to reach 30 knots. Displacement was fixed at at least 2000 tons, and for 3000 tons artillery and fuel made for 1000 tons. I. M. Dikov sanctioned the calculations, submitted to St. Petersburg.

The longitudinal, cross sections, coal tanks locations, engine and boiler configuration were refined as the tonnage jumped to 3202 tons. The armored deck was defined to 20 mm thick, with 40-50 mm slopes around the engine rooms. A model was constructed and delivered on June 13, 1898 while at the same time was studied the Ansaldo yards blueprint for MTK consideration followed the next month by the British yards but both the price tag and lack of documentation closed it.

Nevsky Shipbuilding’s project saw engineer E. Reed participating with Maudsley, Field & Sun, with a large length ratio of 9.6. It was followed by Schichau, Laird and Gironde yards proposals, and eventually in August 1898, Vice-Admiral V.P. Verkhovsky signed with Schihau’s boss R. A. Ziese. Deadline for sea trials was December 5, 1900). Construction took place in the Danzig branch of Schichau, equipments being provided by the Elbing branch.

The crew was formed before construction, controlled by 2nd rank Pyotr Fyodorovich Gavrilov also supervising construction of four 350-ton destroyers, and met Whilhelm II later, discussing the ship’s construction. however paperwork and supply problems delayed construction until December 1899, and even then the keel was laid down by February 9, 1900. Work progressed steadily, with launch scheduled only six months after the start ans Schichau was in a hurry, hoping to present the ship at a crowned head official meeting in Danzig. Novik was launched on August 2, 1900, but unusually harsh winter for Danzig slowed down the completion.

Design of Novik

Description of the hull structure in the Report on the Maritime Department in 1897-1900, is very telling, decribing Novik as

“a huge 3000 tonnes destroyer with a 25-knot sped; A lower part cigar-like, slightly flattened vertically, covered by an armored deck, with a double bottom gradually converging with the outer hull approximately halfway from the keel to the waterline, bordering coal rooms, bottom and top armored deck. Above the flattened underwater “cigar” the superstructure, most part above-water forms a single interdeck space.”

Between perpendiculars, the hull measured 106 m with a 12.2 m beam, excluding the skin thickness, and height from the keel to upper deck of 7.7 m. The building material is a mild Siemens-open-hearth steel with 610 mm spacing. Normal displacement as stpipulated by contract, water and 360 tons of coal was 2720 tons, 300 tons less than expected, thanks to the efforts made in lighterning the structure during construction. The structural lightness was made very clear by the fact in 1902 it became necessary to replace the ladders in the boiler room due to vibrations. By 1903, ramps, entrances and exits were quite narrow, also to gain weight, but this did not pleased the crew and visitors alike.

The cruiser’s command bridge was the forward cabin with wooen paneling and from the small conning tower in battle and aft quartedeck bridge. All three had compasses, mechanical steering wheels and electric steering systems plus link to the telegraph, and communication tubes and electric bells to the engine room. Initially there was no wheelhouse aft. A wave breaker shield was installed forward. By the spring of 1901, when all was installed, it appeared to the yard the bridge was too low, with short wings so that vision of the hull’s sides was impossible. The Yard later admitted the mistake and replaced the bridge meeting P.F. Gavrilov exact specs.

Propulsion

Speed was indeed paramount: The powerplant consisted in three vertical four-cylinder compound engines. Two low, one medium/high pressure cylinders, triple expansion. They were fed by 12 Schichau water tube boilers, a German modification of the Tornycroft models. Total heating surface was 4500 m2 and their working pressure was 18 atm. Two engine rooms were managed, forward and aft explaining the three funnels far apart. It took a consireable space inside the hull with six boiler in two rooms. Their exhausts were combined into pairs across the hull ending with their own funnek. More so, these engine rooms were placed in échelon: Two boiler rooms followed by a machinery room, then one boiler room followed by another engine explaining the distance between the funnels.Speed:

This powerplant produced a total output of 18,000 hp (13,000 kW) and the specified 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) top speed was easily reached on sea trials with forced heating. Novik carried only 500 tons coal, enough for a range of 5,000 nmi (9,300 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) or 500 nmi (930 km) at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

Propellers differed slightly as the former was 4 m in diameter and the other 3.9 m. However after an accident on May 11, 1901, slightly smaller diameter propellers were installed of 3.9, 3.76 m, respectively. However strong vibrations persisted, forcing a new change with three-blade propellers 3.9 m and while four-blade propellers were 3.56 in diameter.

Protection

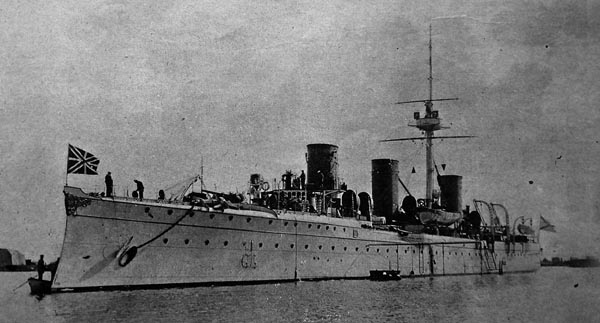

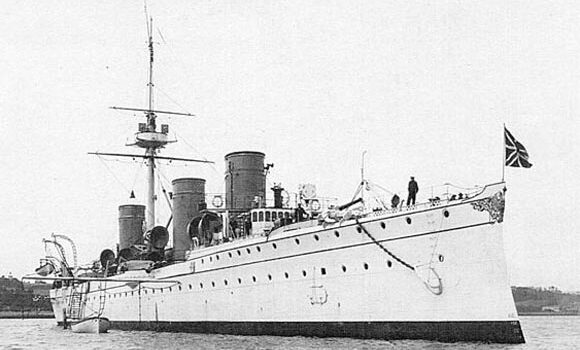

Novik in Brest, 1902

Armoured deck

The main protection was provided by the armored deck, as in any protected cruiser. It was located on 0.6 m above the waterline. The belt connected to it stopped 29.5 m short of the bow, and it smoothly graded down aft, resting on the stem at 2.1 m deep. Reduction there of the armored deck started 25.5 m from the stern with a recess of 0.6 m. The deck consisted of two layers of hardened steel plates for a total of 30 mm (10 mm + 20 mm). The armored deck weighted 600 tons

Belt, upper decks and CT

The side slopes formed a 1.25 m stray below the waterline with a total combined thickness of 50 mm (15mm + 35mm). Over the machinery space which protruded above the armored deck there was 70-mm thick glacis. Additional protection was provided by coal storage rooms alongside the hull, located just above the armored deck, and along the engine and boiler rooms. Stability was provided by the conning tower, protected by 30 mm nickel steel armored plates walls. The well connecting the wheelhouse with the armored deck to transmit command was protected the same way.

ASW compartmentation

17 watertight bulkheads were built below the waterline and nine above the armored deck. There was also a double bottom in the engine and boiler rooms dividing this area by longitudinal bulkheads. MTK was pleased with this high compartmentation and demanded more, to bring transverse bulkheads from boilers rooms bottoms to the upper deck. The curvilinearly design of the bulkheads, ensured smoke exits were kept watertight.

Armament

120 mm 45 caliber Pattern 1892

Design by Canet, France, 1891, manufactured under licence by Obukhov, Perm. Installed on a lot of armoured and protected cruisers among others. This was the default secondary gun of the Russian Imperial Navy for two decades.

⚙ specs Canet 120 mm 45 caliber Pattern 1892 |

|

| Weight | 2.95 t (3.25 short tons) |

| Barrel lenght | 5.4 m (17 ft 9 in) oa, barrel 4.2 m (13 ft 9 in) |

| Elevation/Traverse | -7° to +20°, c170-300° arc |

| Loading system | Breech of the piston type |

| Muzzle velocity | 823 m/s (2,700 ft/s) |

| Range | 11.8 km (7.3 mi) at +20° |

| Guidance | Visual |

| Crew | c11 |

| Round | Fixed QF ammunition 20.4 kg (45 lb) 4.7 in, 45 caliber |

| Rate of Fire | 12-15 rpm |

Anti-Torpedo Boat Armament:

Anti-torpedo boat armament consisted of eight 47 mm guns, four in the bow and stern casemates and four in midship sponsons.

Single mount 47 mm (3-pdr) Hotchkiss gun. First produced in 1885. Quickspecs: Weight, 240 kg in firing position, Barrel length 43.5 mm/47 caliber ROF 15 rpm, sighting range 4.6 km.

37 mm Hotchkiss

A model that can be dismounted to be relocated on a pintle fitted on a steam cutter. Similar to the French model Hotchkiss cannon.

Optional: Maxim-Nortdenfelt 0.8 mm machine guns

Torpedo Armament:

Five torpedo tubes with 11 torpedoes, placed one on the stern and two on each side, all above water.

Whitehead type, 15″ (381mm) Type “L”, 1898

Wargead 141 lbs. (64 kg) TNT, Range/Speed 980 yards (900 m)/25 knots or 660 yards (600 m)/29 knots

Specifications (1914) |

|

| Dimensions (L-w-h) | 110, x 12,2 x 5 m (360 x 40 x 16 feets) |

| Displacement | 3080 t standard, 3129 t FL |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts VTE, 12 boilers, 18,000 hp |

| Speed (road) | 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) |

| Range | 5,000 nmi (9,300 km)/10 kts, 500 nm/20kts |

| Armament | 6x 120mm, 6x 47mm, 2x 37mm, 5 TT 381 mm |

| Armor | Deck: 50 mm (2 in), Conning tower: 28 mm (1 in) |

| Crew | 340 |

Novik’s first career

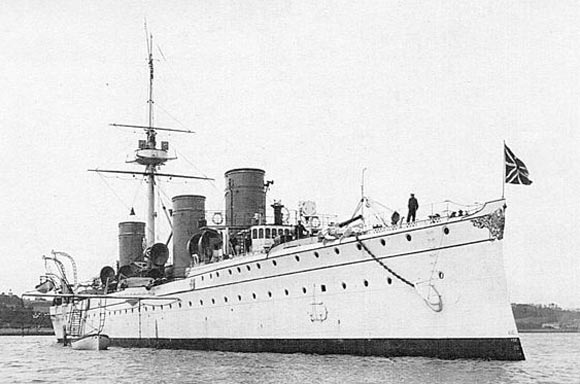

Novik as built in 1902, shortly after entering service in Kronstadt

Reception of the Novik

Construction, completion and tests in Russia of the first experimental high-speed small reconnaissance cruiser in Russian history, given the extremely contradictory tactical and technical requirements of the Russian Admiralty, was quite technical achievement of Schichau. It even became and a landmark in the development history of light Cruisers, internationally remarked. To satisfy the high speed request, the yard was pushed to innovate: An unusually lengthened hull, maximum ease of construction to the detriment of strength and use of an unusually powerful, lightweight and compact steam-piston propulsion system, all wrapped into a striking package.

Prior to the the Russo-Japanese War, the Novik was highly controversial as viewed by world’s experts. However upon completion Emperor Wilhelm II though the Russians unreasonably increased armament while German experts, were not as enthusiastic as the article of German magazine “Die Flotte”, calling the Novik over-powerful compared to its weight and in short “an overkill”. For

Admiral S. O. Makarov, the Novik also had an unjustifiably high speed and having no intermediary caliber like 203 mm (8 inches) limited its combat capabilities at long distances, rendering her speed somewhat irrelevant.

Gallery

By February 1904, Makarov, sent a vitriolic letter to the managing director of the Navy Ministry F.K. Avelan. He proposed instead a reconstruction at the Nevsky Shipyard, bringing characteristics closer to the armored cruiser he wanted. Chief engineer P.F. Veshkurtsov calculated a gain of 270 tons allowing a better armament to be fitted, with a single 8-in and five 6-in and plus ten 3-in guns while the estimated speed was to decrease by 2.7 knots. But there was no time for reconstruction, as the ship was badly needed in the 2nd Pacific squadron.

N. L. Klado also estimated Novik was completely unsuitable for battle or even for scouting missions due to her short range and limited seaworthiness in heavy weather, which in addition to a short range, limited also her top speed. So much so she have been left behind any armored cruiser. Range compared to Bogatyr (also of German construction) was much better.

Early career 1902-1904

Novik was commissioned on 3 May 1901, sailing a day before for factory trials. Instead of joining the Pacific directly, and by May 12, 1901, Novik unofficially visited Kaiser Wilhelm II which greatly appreciated her, but stating her artillery was probably too strong for her small size. On 15 May 1902 she was assigned to Kronstadt in the baltic sea and by August 30, she was reviewed by Nicholas II during a German fleet exercise Danzig, talking with P. F. Gavrilov about the new cruiser’s features. The plant somewhat botched sea trials, forging heat instead of searching for progressive tests.

On 14 September 1902, after months of training the captain was ordered to depart for the Pacific. She transited via the Kiel Canal in Germany to exit the Baltic, stopped at Brest, France on 5 October, then Cadiz in Spain, Naples in Sicily, and arrived in the Piraeus to met the battleship Imperator Nikolai I in state visit. The two ship then sailed to Port Said on 11 December, but this was thwarted by the heavy weather. Both ships went back to transit via the Suez Canal on 20–21 December. Novik stopped afterwards in Jeddah, in Djibouti and Aden (red sea), then Colombo (indian ocean) and Sabang (Indonesia) then Singapore on 28 February 1903. Both ships would reach Manila in the Philippines and recoal a last time in Shanghai in southern China before reaching Port Arthur on 2 April 1903.

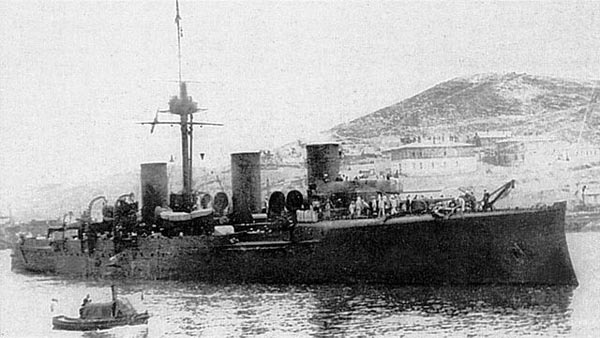

Novik in port Arthur

On 26-29 May 1903, Novik would team up with Askold for a diplomatic visit to Japan, carrying the Russian Minister of War Aleksey Kuropatkin, both in Kobe and Nagasaki; They went back to Port Arthur on 12–13 June and Novik underwent a drydock overhaul (her first since her launch) in Vladivostok, started on 23 July. Like the rest of the Pacific Fleet she was painted in drydock with a dark olive, and was back to Port Arthur in early September 1903, amidst tensions between China, Russia and Japan (over Korea notably).

Novik in the Russo Japanese war

Novik scuttled at Korsakow bay

During the battle of Port Arthur on 9 February 1904, Novik sallied forth, and single-handedly pursued the Japanese destroyers squadron for nearly 30 miles on, exposing her to cruisers fire. but she onlu suffered minor damage from an 8-inch shell and went back. Captain Nikolai von Essen offered combat to the enemy after the night attack, pursuing it and closing only 3,000 yards to the blockading squadron, actually even launching a torpedo, which missed. Back in the yard her repairs took nine days but the captain was rewarded for his bravery.

On 10 March 1904, Admiral Makarov made Novik his flagship and tried to exit from Port Arthur, along with Bayan, in order to rescue one his destroyers stranded after battle damage with a Japanese destroyer outside shore battery range. Her made three attempts but withdrawn within shore battery protection as Japanese Armored Cruisers eventually sank the destroyer. On 13 April strory repeated, as Strashni fought off IJN Destroyers when she was badly damaged and Bayan came to the rescue, making the Japanese fleeing. But Bayan, after picking up some survivors outside of Port Arthur met Makarov in his flagship Petropavlovsk, escorted by Novik, Askold, Diana, and Poltava, just existing Port Arthur. Soon Petropavlovsk struck three mines and sank with great loss of life and the Admiral and the fleet was back inside.

On 23 June, Novik was at war again, making a sortie from Port Arthur as flagship of Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, but was repelled by heavy fire. On 10 August, Vitgeft tried once again to run the blockade, which this time degenerated into Battle of the Yellow Sea. With crippling losses, most of the squadron was back in the harbor to not attempt another exit again until the city fell. Novik was slightly damaged by three hits with two KiA but reached the neutral port of Tsingtao (German colony).

To avoid internment however, soon Commander von Schultz exited again and left behind the Japanese pursuers, heading towards Vladivostok, Tsushima at its heels. Soon the Japanese cruiser was joined by IJN Chitose. Later Novik was spotted by a Japanese transport ship coaling at Sakhalin, but she was soon caught and trapped in Aniva Bay. The Russian cruiser was soon forced into the Battle of Korsakov.

Tsushima approached Korsakov at 16:00, on 20 August 1904. She looked for, and spotted smoke rising from the harbor and was sure this was Novik. The cruiser was later spotted steaming south from Korsakov at 16:30. The duel commenced, both cruisers firing at each other furiously. It was a sharp but one-sided action, wrapped in 30 min. The much heavier Tsushima scored several hits, knocking off half her boilers while the steering compartment was flooded. Novik veered back for Korsakov but 30 min. later around 17:40, she scored a hit on the pursuing IJN Tsushima, striking her on the waterline, flooding two compartments. IJN Tsushima started to list so heavily that she was stopped dead for emergency repairs. Novik was safely in Korsakov and repairs commenced immediately.

Much later as Tsushima was repaired, IJN Chitose arrived and both cruisers sailed to Korsakov during the night. Novik′s steering gear was not repairable, and her searchlights had soon spotted second Japanese cruiser approaching. Realizing she was hopelessly outgunned and having suffered five hits already, including three under the waterline, Von Schultz decided to scuttle his ship and evacuated the crew to the coast. So in short, it was her high speed which allowed the Novik to flee the IJN squadron, but her low range which doomed her.

At dawn on 21 August, IJN Chitose entered the harbor, finding Novik laying half submerged on a sandbank. All her boats and launches were arouund, trying to save her crew and some equipments and documentaion. Chitose opened fire on the cruiser at 9,300 yards (8,500 meters), then 4,400 yards (4,000 meters), scoring 20 more hits with terrific consequences. He closed to 2,700 yards (2,500 meters) before stopping fuiring, realizing the cruiser was now a wreck and could not be salvaged. The paradox is that the Japanese would salvage her later anyway.

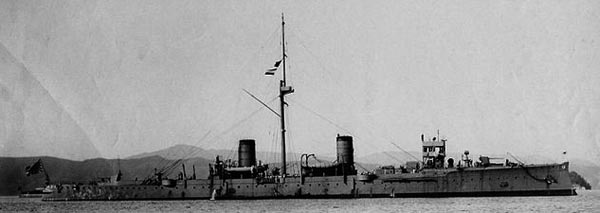

Novik’s second life as IJN Suzuya

IJN Suzuya in Kobe, 1908

The IJN was not laft unimpressed by the Novik and her speed. Despite the cruiser was considered damaged beyond repairs, an engineering crew was sent on the ship to study the possibility of summary repairs for a salvage in August 1905. The operation took almost a year. She was refloated and later towed at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal not only for repairs but reconstruction. She could be recommissioned as IJN Suzuya on 20 August 1906, after the Suzuya River in Karafuto, but repairs and reconstruction will last two years.

Reconstruction consisted in fitting eight Miyabara boilers, and she emerged with two funnels. Her lateral engines were removed and her output fell to 6,000 shp. Her bow and stern main guns were discarded and replaced by modern QF 120-mm guns while the secondary artillery only comprised 3-in guns, but she retained her six 47 mm Hotchkiss guns and two 37 mm guns (which were field guns that can be mounted on wheeled carriages for landings parties.

In December 1908, she was officially completed, making sea trials, and redesignated an aviso. She served as a reconnaissance and dispatch vessel but due to battle damage and incomplete repairs and halved machinery, her top speed never past 19 knots (35 km/h), making her less desirable in this role. In addition the adoption of wireless communications achieved to make her obsolete. IJN Suzuya was re-classified as a second-class coastal defense ship in August 1912, but declared obsolete in April 1913. She was sold for scrap soon afterwards, having a service time in the Japanese Navy of only six years and total active life of barely ten years.

Sources

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_cruiser_Novik

Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1860-1906

Corbett, Julian. Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War.

Corbett, Sir Julian (2015) Maritime Operations In The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905.

Howarth, Stephen. The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895–1945.

Jentsura, Hansgeorg. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945.

Steer, A. P., Lieutenant, Imperial Russian Navy. (1913) “Novik” in The Russo-Japanese War

//www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/novik.htm

Gallery

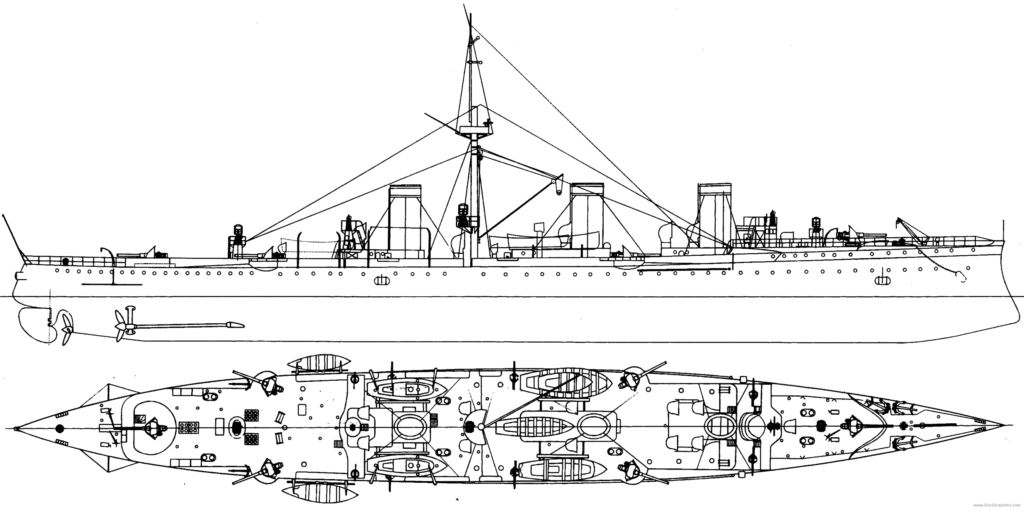

Illustration profile of the Jemtchug, inspired by the Novik

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign