Light Cruisers SMS Dresden, Emden (1908)

Light Cruisers SMS Dresden, Emden (1908)WW1 German Cruisers

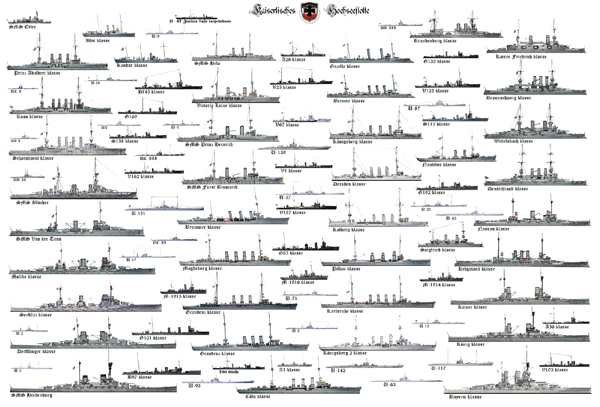

Irene class | SMS Gefion | SMS Hela | SMS Kaiserin Augusta | Victoria Louise class | Prinz Adalbert class | SMS Prinz Heinrich | SMS Fürst Bismarck | Roon class | Scharnhorst class | SMS BlücherBussard class | Gazelle class | Bremen class | Kolberg class | Königsberg class | Nautilus class | Magdeburg class | Dresden class | Graudenz class | Karlsruhe class | Pillau class | Wiesbaden class | Karlsruhe class | Brummer class | Königsberg ii class | Cöln class

Two famous ships

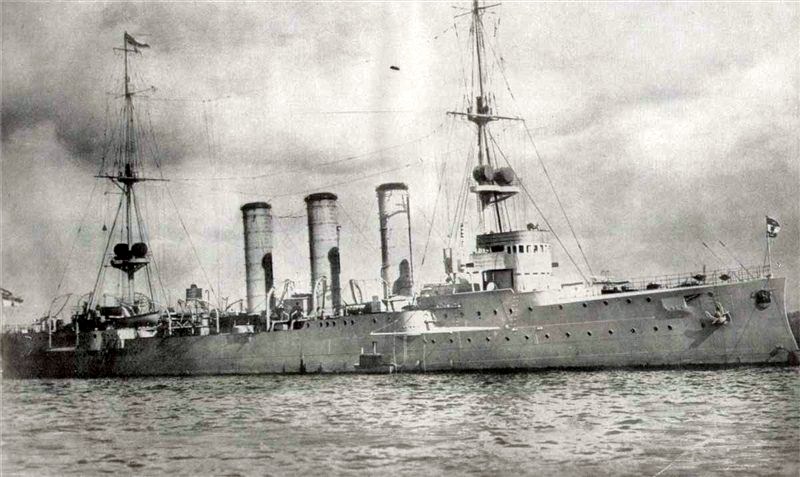

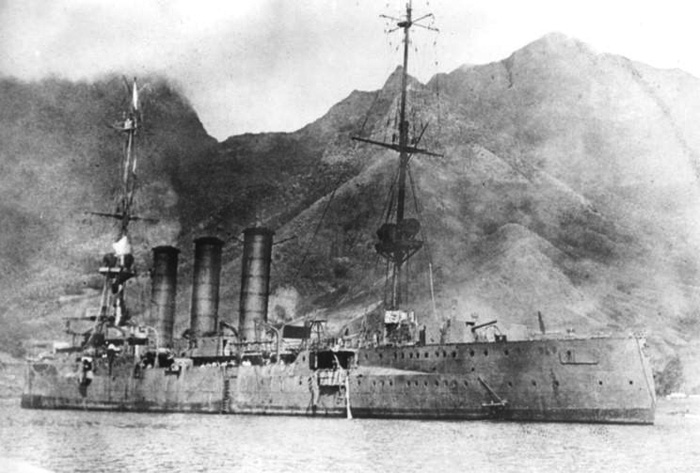

The Dresden class followed the Königsberg class, but improved in size and speed a bit. Launched in 1907-1908, their fates were among the most interesting of the war: Both Königsberg and Dresden were part of the overseas squadrons of the Kaiserliches Marine in 1914. Dresden was in Mexican waters and has to quickly head for the eastern Indian Ocean via Good Hope, and became one of the most famous German commerce raiders, joining Admiral Von Spee’s squadron at the Coronel battle, duelled at the Falkands with Kent and Glasgow, but ended scuttled in the maze of islands of Chile in March 1915. Emden was in China, heading with Graf Spee’s East Asia Squadron and was detached for independent raiding in the Indian Ocean, also attacking Penang and the Cocos Islands, but lost a duel to HMAS Sydney. The Crew then managed to get back to Germany, in a true odyssey which was turned into two movies.

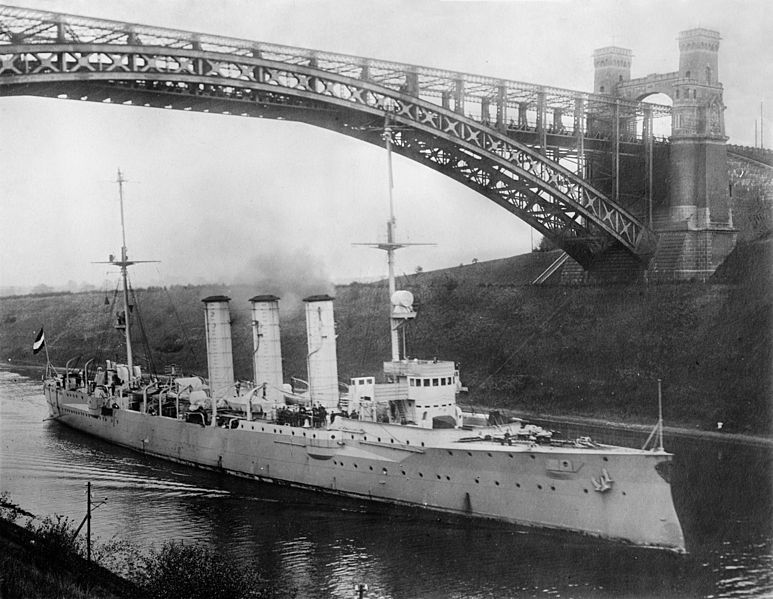

SMS Dresden through the Kiel Canal

Design

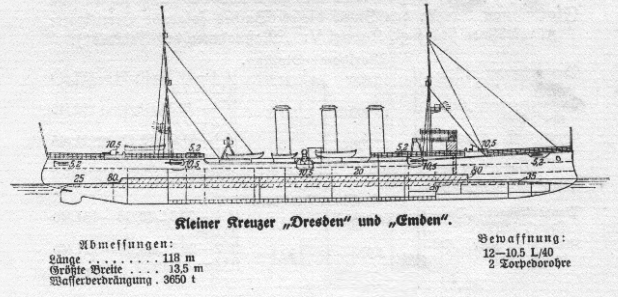

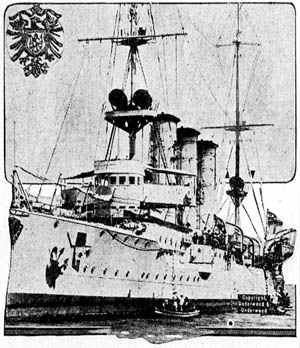

Profile overview in a German publication

The origins of the design could be found in the 1898 Naval Law, authorizing construction of no less than thirty new light cruisers. The Gazelle class has been the first, developed into the Bremen, and then Königsberg class. Both had many incremental innovations and improvements over globally the same basic design. The two Dresden class just proceeded with the same caution, design-wise. Ordered in the 1905–1906 construction program, they were not just a repeat of the Königsberg but consituted an improvement. Keeping the same main battery they had a slightly greater displacement, the internal machinery space be generous enough to accommodate an additional boiler, and thus, increase engine power. Like on the previous class, engineers differentiated both vessels by testing different machinery: VTE for SMS Emden and steam turbine for the lead ship, in order to compare their performances. But it was the last and decisive test of tht kind. After this, the admiralty decided from then on all cruisers would be fitted with turbines only.

The previous Bremen class – Illustrated London News, 20 March 1915

These cruisers were built at Blohm and Voss shipyard (Dresden) and Kaiserliche Werft, Danzig (Emden). They were launched in 1907-1908, and entered service in 1908-1909. Larger by one meter, wider by 30 cm and heavier by 200 tonnes, they were slightly faster (23.5 and 24 knots compared to 23), but possessing the same firepower, they really shows this almost timid incremental process. The next Kolberg class (1909) were much larger and faster, and better armed.But the true really first innovative designs were the Magdeburg (1912).

Hull & general characteristics

Model of the Emden: Note she was not in overall grey in 1914

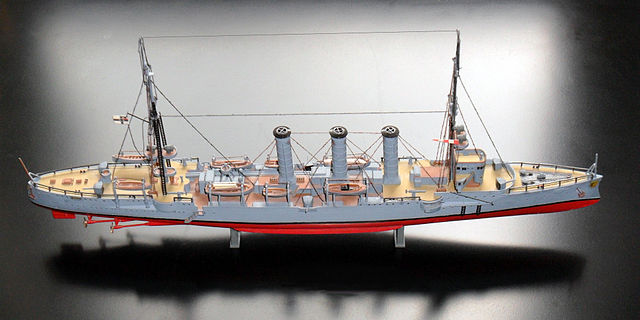

Model of the Dresden

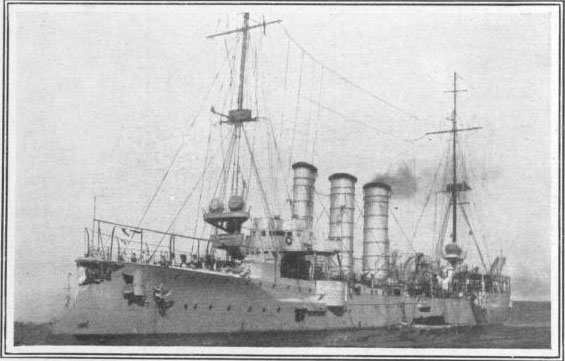

Both ships had this characteristic three-funnels silhouette. Their hull measured 117.90 meters (386 ft 10 in) long at the waterline and 118.30 m (388 ft 1 in) long overall, for a beam of 13.50 m (44 ft 3 in), with a draft iif 5.53 m (18 ft 2 in) forward, greater aft. Standard displacement was 3,664 metric tons, reaching 4,268 t (4,201 long tons; 4,705 short tons) fully loaded. Construction called like previous ships for transverse and longitudinal steel frames. They had a transverse metacentric height of .59 m (1 ft 11 in), which was reasonable. This ensure a gentle, predictable motion.

Dresden and Emden carried 18 officers for 343 enlisted men. Like all vessels of that era, they carried many small boats, a fleet including a single picket boat, a barge, a cutter, two yawls and two dinghies. The last four were mostly used for physical training, sailors making regattas against themselves or other crews, and to carry personal, or land armed parties, somehing which will proved handy for Emden in two occasions. The steam picket boat was the standard laison all-weather vessel used to carry officers to port or used to carry dispatch to other ships in the fleet at sea. The barge was used for coaling and carry supplies, and the cutter as a fast dispatch vessel with ample sail. It was used generally by captains as their own leizure boats when not in service;

Protection

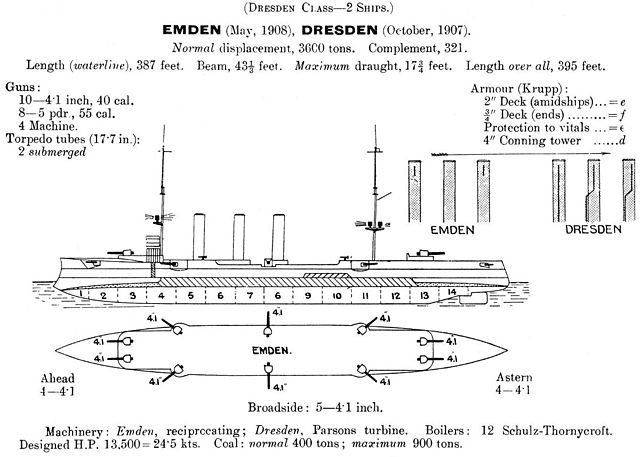

Jane’s 1914 Dresden class diagrams and drawing

Their armour was slightly improved, with the deck and turrets protected by 50 mm (2.5 in) to 80 mm (3 in) of armor: It was thicker on the slopes either side.

To be more precise, the main armoured deck at the waterline reached up to 80 mm (3.1 in) amidships with sloped 50 mm (2 in) thick, but tapered down to 30 mm (1.2 in) aft and 20 mm (0.79 in) toward the stern.

The main belt was about 30 mm thick (1.8 in), only on the central section, between the forward bridge and extending to the aft gun. An extra stray of armour of 50 mm was fitted over the machinery spaces aft.

The conning tower had walls 100 mm thick (4 in) with a saller communication tube going two decks below.

The gun masks were 50 mm thick (2.5 in) and in addition the forward and aft guns were protected by a partial structure. The four on the corner of the main battery were inside casemates.

The hull was subdivided under the waterline into thirteen watertight compartments, with a double bottom below, extendeding for 47% of the length of the keel.

Machinery

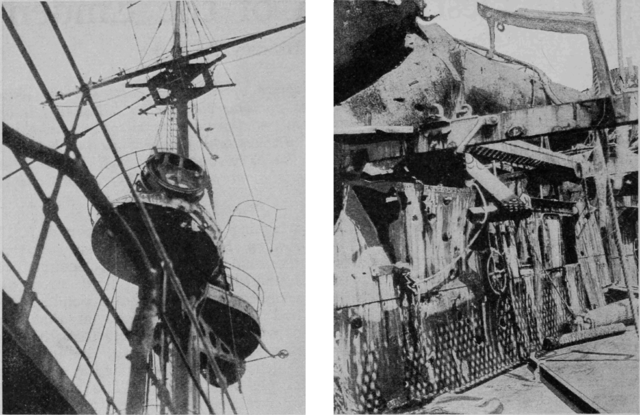

Binnacle of Emden, salvaged in Australia

Propulsion relied on two propellers, and they possessed three 4-cylinder engines, 12 standard boilers, for a total of 13,500 hp, and top speed of 23.5 knots.

The Dresden were reputed to be good sea boats, but cranking and rolling up to 20° in heavy weather, being also very wet at high speeds. they also suffered a slight weather helm. But they turned tightly, and were very maneuverable and agile. Their relatively small size and hull design made speed losses on a hard turn limited to 35%, which was very reasonable for this class of ship.

Armament

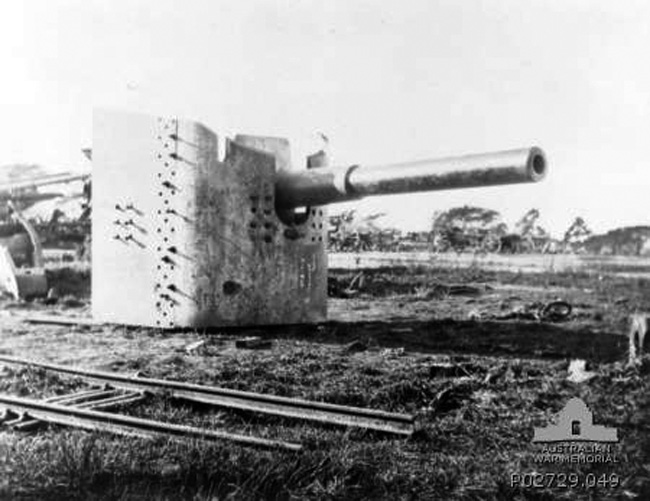

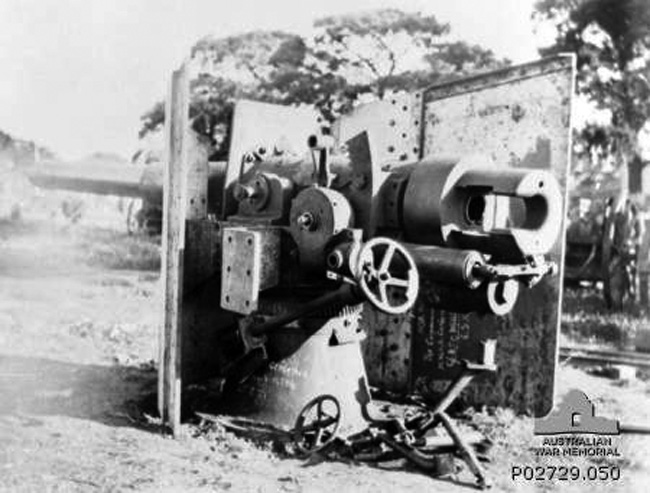

10.5 cm SK/L40 salvaged on the Emden’s wreck by the Australians after the war, AWM.

Main armament: Ten 105 mm (4.1 in) (4 in) SK L/40 guns, which were placed as follows: Two side by side on the prow and bow, and the others six on the sides, the two amidship with their own masks and the remainder in casemates. They reached 12,700 m (13,900 yd) and were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition (150 per gun).

Secondary armament: Both cruisers were armed with eight 5.2 cm (2 in) SK L/55 guns, with 4,000 rounds of ammunition. This was an improvement over the previous Königsberg, which had none. The danger indeed of torpeod boats was recoignised as it was estimated that the main guns had not enough rate of fire to deal with them until reaching critical distance. The 5.2 cm had a short career in the Kaiserliches Marine. The next Kolbergs had only four of them, and the Magdeburg class has none, but gaining the excellent 8.8 cm SK L/45 from 1917, which became the de facto standard light gun in the Navy.

Torpedo armament: Like all previous cruisers, the Dresden class were provided with two 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. They were submerged, fixed in the broadside, with five reloads.

Old author’s illustration of the SMS Emden, in 1914 white colonial livery, Tsingtau, China.

Dresden class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 118,30 x 13,50 x 5.53 m |

| Displacement | 3660 t/4270 t FL |

| Crew | 361 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Brown-Boveri Steam turbines/VTE 15,000/13,500 cv |

| Speed | 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Range | ? nmi (? km, ? mi) 19 knots (35 km/h, 22 mph) |

| Armament | 10x 105 mm, 8x 52 mm, 2x 450 mm sub TT. |

| Armor | Belt 50 mm, deck 30mm, bulkheads 50 mm, CT 100 mm |

Resources

On historyofwar.org

On deutsche-schutzgebiete.de

On worldnavalships.com

On scapa-flow.co.uk

On battleships-cruisers.co.uk

On worldwar1.co.uk

SMS Emden’s incredible true Odyssey

The class on wikipedia

Docu-Movie about the Emden (Unter kaiserlicher Flagge (1/2))

Docu-Movie about the Desden (Unter kaiserlicher Flagge (2/2))

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921.

Delgado, James P. (2004). Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks. Douglas & McIntyre

Forstmeier, Friedrich (1972). “SMS Emden, Small Protected Cruiser 1906—1914”. Warship Profile 25.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis

Herwig, Holger (1980). “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books.

Lenz, Lawrence (2008). Power and Policy: America’s First Steps to Superpower, 1889–1922. Algora Pub

Levine, Edward F. & Panetta, Roger (2009). Hudson–Fulton Celebration of 1909. Arcadia Pub.

Mueller, Michael (2007). Canaris: The Life and Death of Hitler’s Spymaster. Annapolis

Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). “The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy”. Osprey.

Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas: German Cruiser Battles, 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Maritime.

Von Mücke, Hellmuth (2000). The Emden—Ayesha Adventure: German Raiders in the South Seas and Beyond, 1914.

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918: Bremen bis Cöln-Klasse. Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

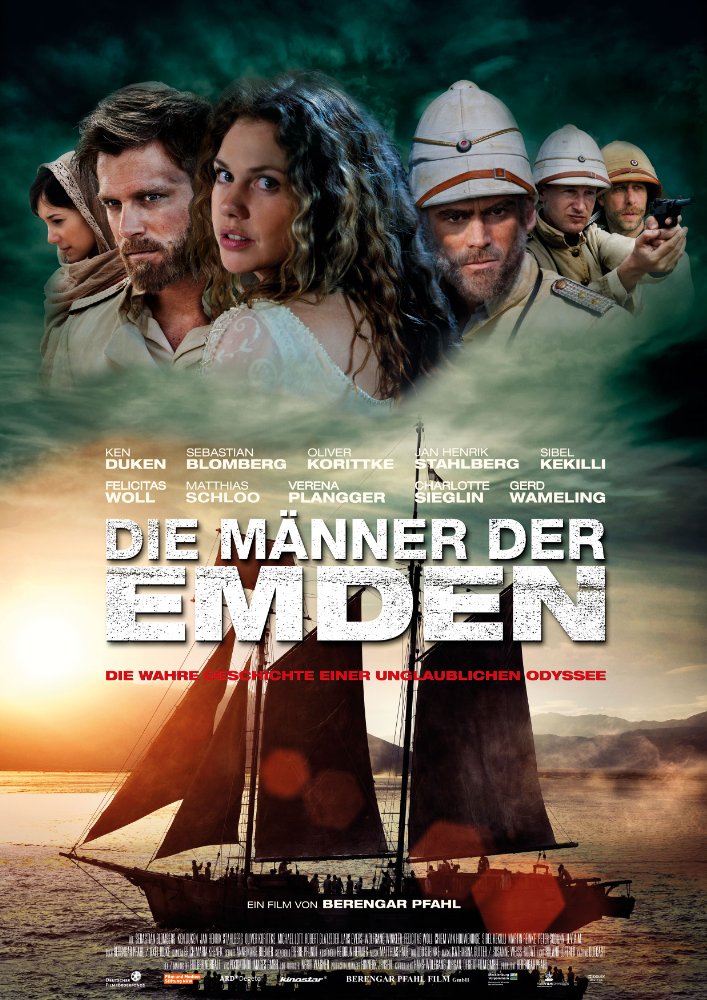

Movies about the Emden:

“How We Beat the Emden” and

More recently, in 2012,Die Männer der Emden (The men of the Emden) was released, but only covering how Von Mücke’s stranded crew made their way back to Germany after the Battle of Cocos.

Model Kits

Dresden model kits on scaleway: , HP-Models & Arno 1/700 (etc.) Deans Marine 1/90

Gallery

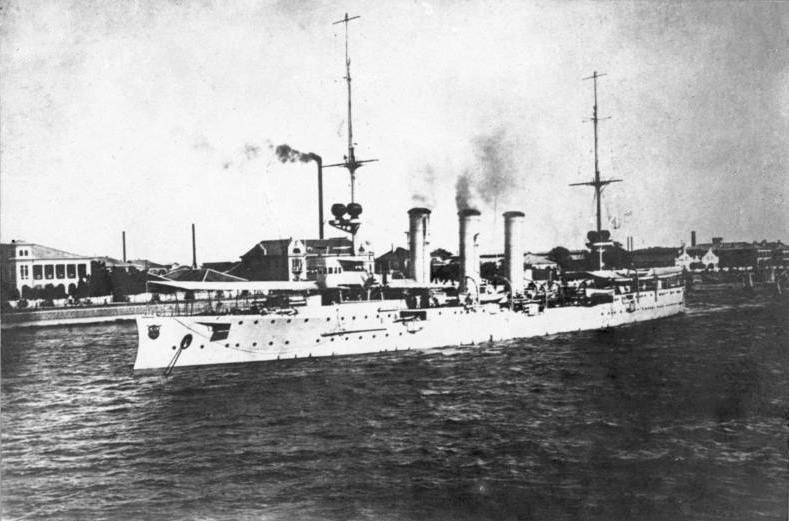

SMS Dresden in New York, in prewar two-tones livery (white hull, canvas brown superstructures)

Hudson-Fulton Celebration, 1909, Dresden in company of other cruisers

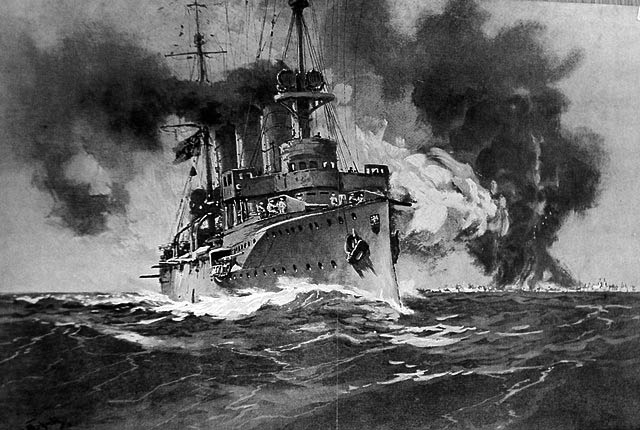

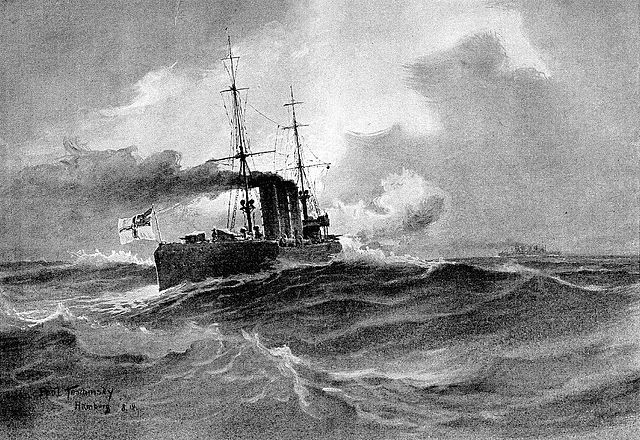

Battle painting (cc)

Emden stranded, painting by Hans Bohrdt

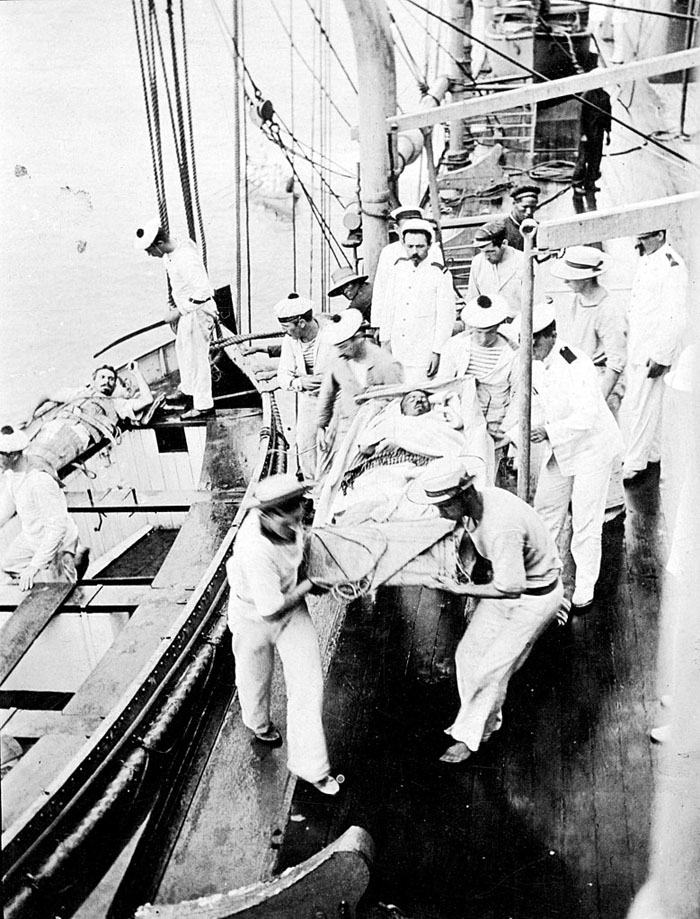

Transferring wounded on Empress of Augusta after the battle

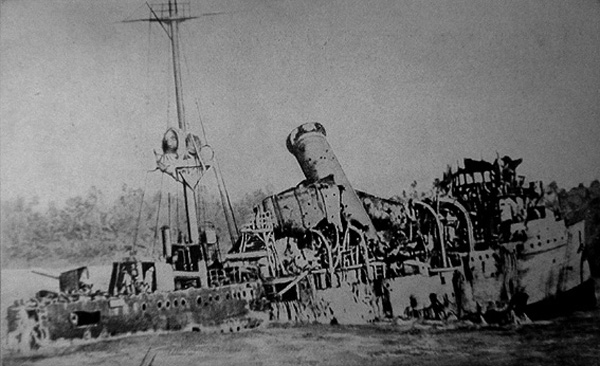

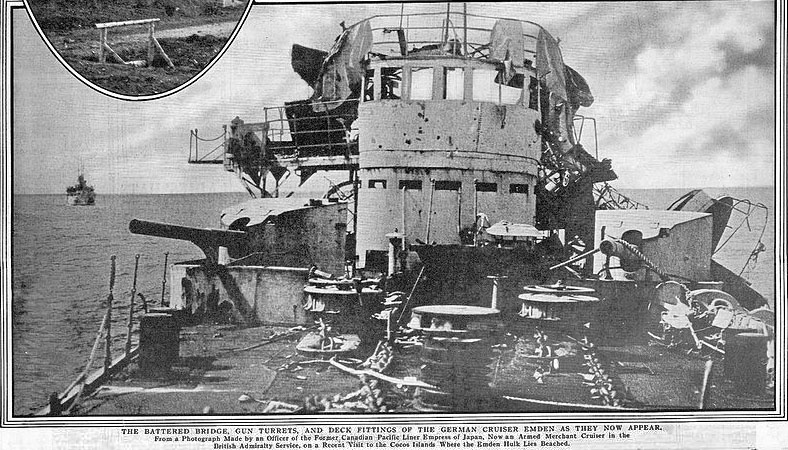

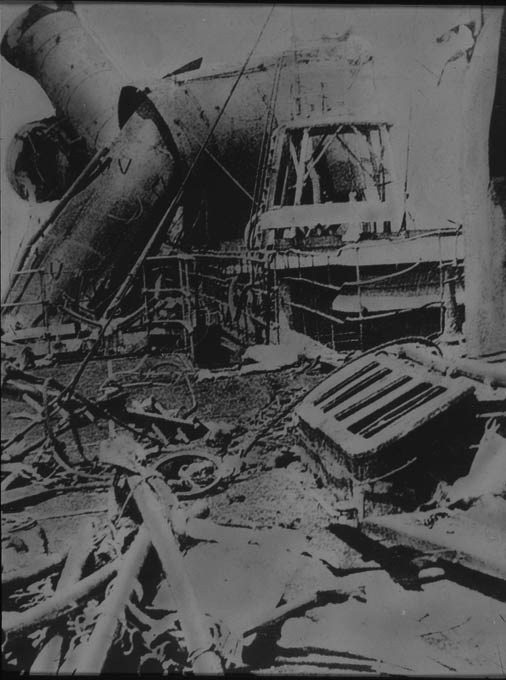

Aft view of the wreck

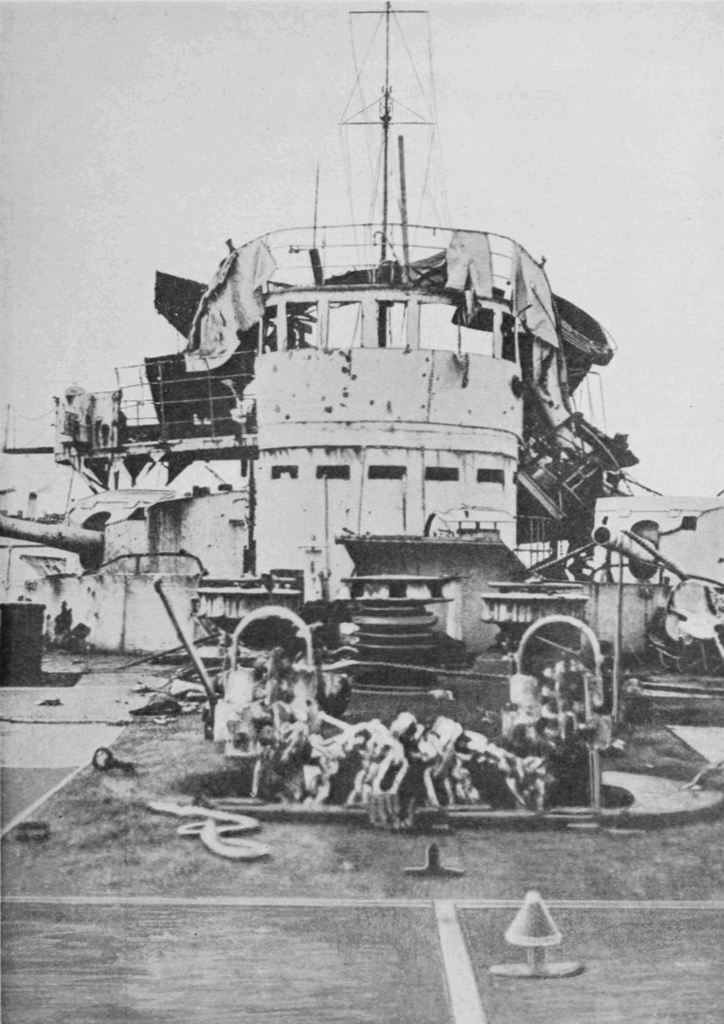

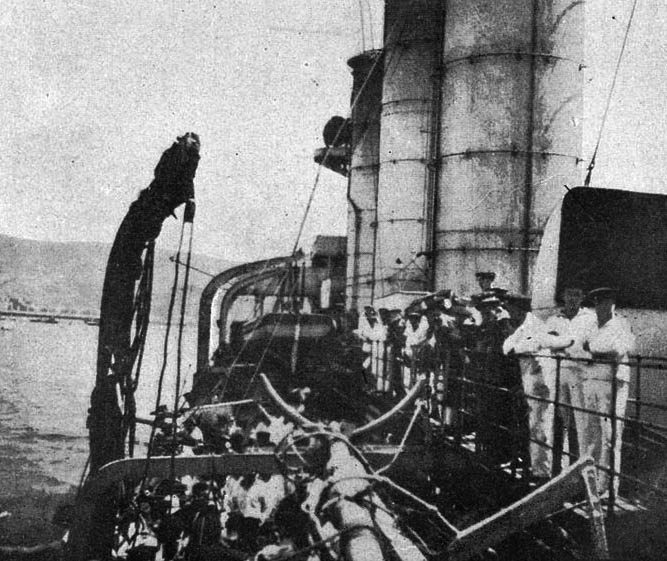

Battle damage of the Emden

Forward deck damage

The deck of SMS Eden, showing extensive damage

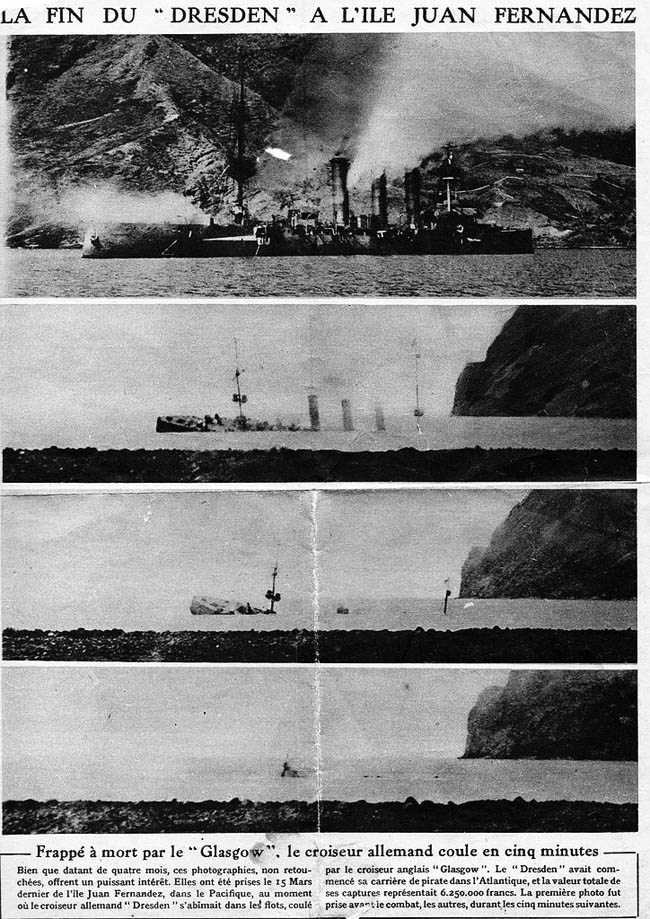

French article on the end of Dresden

SMS Emden

Interwar service

SMS Emden entered service in 1909, taking part in autumn manoeuvers and escorting the imperial yacht Hohenzollern with the Kaiser aboard. She was decommissioned after completing trials and on 1 April 1910 assigned to the Ostasiengeschwader (East Asia Squadron) in Tsingtao, 1897 Kiautschou concession (China). She left Kiel on 12 April 1910, but made a goodwill tour of South America (12 May, Montevideo to meet Bremen, Ostamerikanischen Station), and headed for Buenos Aires, to participate in the celebrations of the hundredth anniversary of Argentinian independence. They passed the Horn and stopped in Valparaíso, and separared off Peru, as Emden headed for the Pacific, stuggling at frst to get good quality coal.

Emden carried 1,400 t of coal from the Chilean naval base at Talcahuano and was en route on 24 June, making her long-term shakedown cruiser along the way. Everything was noted on a report for future cruiser designs. She met severe weather along the way, notably off Easter Island, stopped in French Papeete, Tahiti, and made the next 4,200 nautical miles trip to German Samoa (22 July) to meet the East Asia Squadron (Konteradmiral Erich Gühler).

The crew of SMS Emden before the war

In October, the squadron headed for Tsingtao and for the first time, Emden entered the Yangtze River, exploring it from 27 October to 19 November and stopping in Hankou. Next she headed to Japan, stopping at Nagasaki and was back in Tsingtao on 22 December, and a refit, interrupted by the the Sokehs Rebellion at Ponape in the Carolines. She was ordered there, departing on 28 December, and joined by SMS Nürnberg from Hong Kong.

They met at Ponape the old Cormoran and all three bombarded rebel positions, completing the mission by sending a large combined landing force, which were added to the colonial police troops. This ground offensive was made on mid-January 1911 and by late February the revolt was suppressed. On 26 February the old cruiser SMS Condor arrived arrived to relieve them and Emden departed on 1 March for Tsingtao, via Guam, arriving on 19 March and starting her overhaul.

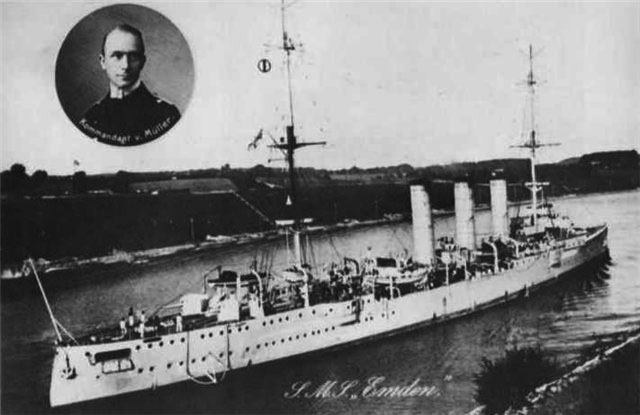

Emden in Tsingtao, early 1914

By mid-1911, she toured Japan and accidentally rammed a Japanese steamer, during a typhoon, which caused enough damage to sent her in drydock in Tsingtao. Next she was ordered in the Yangtze to protect Europeans as the Chinese Revolution broke out on 10 October and by November she was placed under ordered of Vizeadmiral Maximilian von Spee. The cruiser won the Kaiser’s Schießpreis for her gunnery marksmanship, in the whole East Asia Squadron. She was sent off Incheon to assist the steamer Deike Rickmers, grounded, and by May 1913 Karl von Müller took command, soon promoted Fregattenkapitän. In mid-June she cruise German colonies in the Central Pacific. In between she was sent to Nanjing to protect nationals during a fight between Qing and revolutionary forces and in August, she was attacked by rebels believing she sided with Qing. Her gunners returned fire, which was efficient.

Wartime service

In August 1914, Commander Von Müller decided to leave the base quickly so as not to be cornered by a superior forced and to join Von Spee’s squadron in the Pacific through the Strait of Korea. In between the spotted and caught a Russian liner, the Riasan, take the crew in custodu, recoaled and scuttled the ship. Müller learnt in between Admiral Jerram’s squadron had arrived off Tsing tao, Von Spee then having no other option but to make for home, or die trying. The Japanese went at war in turn on 23 August but after a conference between Spee and Müller, Emden was to be left in the Indian Ocean as a diversion, while the squadron was steaming to the Cape Horn.

The Indian Ocean raider

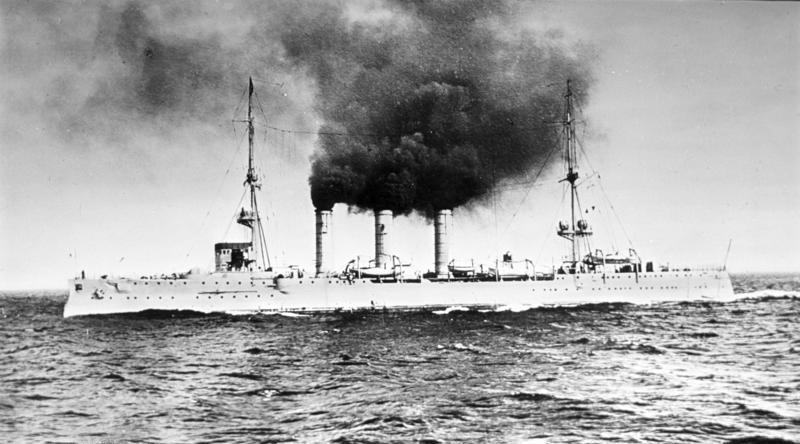

The SMS Emden at sea.

By leaving Spee, Emden started a formidable raiding spree that would enter the annals of the Kaiserliches Marine as one of the most successful. After roaming off Indonesia, with a fourth fake funnel built to look like a British cruiser, she missed her coaler, the Markomannia on September 8th but persuaded the captain of the neutral Greek coaler Pontoporos to supply him. Later she seized the freighter “Indus” loaded with food a welcome addition.

The latter was abandoned as too slow, the crew transferred to Markomannia. Next, Emden captured the cargo “Lovat”, the Kabinga, the small coaler Killin, the large steamer SS Diplomat. Next he sized the Italian Loredano, sunk the coaster Trabboch, but was betrayed by a communicaion by the captain of the Loredano, passing his position to the Admiralty, that scrambled all available forces.

Leaving her small fleet, Emden loaded all she could and started to steam fast, now trying to attack British ports on the Indian coast. On September 22, she raided the oil tanks of Madras, and the shelled Colombo, also sinking a large transport of sugar.

Emden and Captain Müller in medallion

Next, she raided Diego Garcia, an important British colonial base, on the Mauritius islands. Von Müller briefed his staff of not to divulgate there was a state of war, and camed as for a “courtesy visit”. He was well received by the Governor and be able to replenish serenely. By wireless however he soon learned about the arrival of British vessels, and left the island precipitately, leaving behind the Markomannia. She hid behind the island of Minnikoy, sinking five English steamers. Eventually Von Müller decided to leave the area and rally Von Spee via Malacca strait.

The Emden arrived on the 28th of October before dawn off Georgetown, Penange, all light shut and surprised four French ships at anchor, including the cruiser d’Iberville. One destroyer, the Mousquet, was patrolling nearby but failed to see her. The Russian cruiser Jemtchug was also there, a more deadly opponent. Emden opened fire from the best position, at point-blank while hoisting the flag of war and launched a torpedo on the Jemtchoug, whichremained afloat but was crippled by artillery. The latter counter-fired but without effect and she launched a second torpedo, apparently striking her ammunition store. The Russian cruiser blew up and sank. D’Iberville came, but was fooled by a change of flag, and reassuring morse about an accidental explosion, until her captain saw the Emden fourth fake funnel trembling in the wind, realizing his error. But it was too late, with the Aviso’s light artillery and engines cold, she could do little before Emden escaped.

Steaming for the other side of the harbour she captured the steamer Glen Turret, but was surprised by the French destroyer Mousquet, which aptain decided to make a torpedo run. Emden’s fire battered the French TB during her approach and she eventually capsized and sank. A second destroyer approached, but again Emden managed to escape. She was chased off by the French destroyer for hours, until running out of coal.

The Cocos Islands Battle and return home

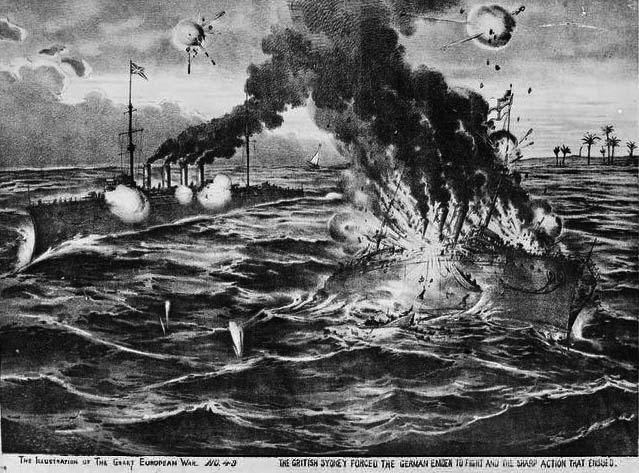

Battle engraving emden and sydney, Imperial War Museum, Galleries at the Crystal Palace

The Emden arrived next in the Cocos Islands, one of which had a radio station that Von Müller needed to destroy, in order to refuel there. When the cruiser arrived, a message was sent nevertheless, intercepted by the Australian cruisers HMAS Melbourne and Sydney escorting a convoy nearby. The two ships steamed towards the Cocos Islands just half an hour later, while 50 of the crew (a demolition landing party) just were now on the island, including the second Von Mücke, proceeding to the destruction of the radio station of Direction Island.

HMAS Sydney soon spotted and engaged Emden, with her numerous longer range, hard-hitting 6-in guns. With a reduced crew, Emden could not fleet not answer effectively and she was soon blasted. Her telemetry was destroyed, and her guns silenced one by one as the funnels were falling. Soon, this was over.

Emden’s wreck on North Keeling Island, took the day after.

Von Mücke’s company saw the unequal action from the roof of one building. They greeted the apparent 18 hits by Emden on Sydney (killing three, wounding 13) but she ended ablaze and dead in the water after 670 rounds spent, 100 claimed on target. Von Müller managed to beach her on the reefs of North Keeling, saving most of the remaining crew. Captain Glossop sent an injunction to surrender and two warning salvoes until a German white flag was hoisted. Emden lost 133 officers and men in this fight, out of 376. The remainder left the ship, which was scuttled properly.

The wreck of Emden

Survivors of SMS Emden under guard on a boat, to become POW in Australia and Malta

Sydney left quickly to head for Direction Island and land her own company of riflemen to engage Von Mücke’s men, but the latter in between seized the governor’s schooner, Ayesha, and sailed to the island of Padang, Dutch East Indies. Von Müller’s men were later made POW, some interned in Australia, the others in Malta, back home in 1920. The rest of the trip was near-legendary. Von Mücke managed to conduct the Ayesha to Sumatra on November, 7, later waited and embarked in a German steamer for Yemen. They reached Bab-el-Mandeb, crossed all the Arabian peninsula and arrived in Constantinople in june 1915. Latter they took the train and reached in June 1915 the fatherland, greeted as heroes. The rampage of Emden would span 30,000 nautical miles (56,000 km; 35,000 mi), added to the formidable tally she could claim.

Reunion of former adversaries in Germany, 1967

SMS Dresden

SMS Dresden, ordered as “Ersatz Comet” in Blohm & Voss shipyard (Hamburg), was laid down in 1906, launched on 5 October 1907, commissioned on 14 November 1908. On 28 November during her sea trials she collided with the small Swedish coaster Cäcilie off Kiel. Her starboard propeller shaft however was moved 1.2 in off-axis, requiring six months of repairs. Sea trials only resumed 1909, leading to a turbine accident, having her in repairs again until September.

Dresden had botched trials, declared over on 7 September by an impatient admiral, and she made her shakedown cruiser while visit the United States, representing Germany at the Hudson–Fulton Celebration (New York) in company of the cruisers Hertha and Victoria Louise as well as Bremen, sailing on 11 September, arriving at the gathering point at Newport, and arriving in New York on 24 September. She stayed there until 9 October and was back in Germany on 22 October.

Dresden and other German ships at the Hudson–Fulton Celebration NYC, 1909

Next, SMS Dresden was assigned to the reconnaissance force, High Seas Fleet and started her peacetime routine of squadron exercises alternated with training cruises and yearly fleet exercises. On 16 February 1910, really unlucky by this point, she collided with SMS Königsberg. The one caused again significant damage and furter repairs in Kiel for eight days. After visiting Hamburg on 13–17 May she was assigned to the Training Squadron on 14-20 April 1912 with Friedrich Carl and Mainz. She earned the 1911–12 Schießpreis (Shooting Prize) for light cruisers. Until September 1913 she was under orders of Fregattenkapitän Fritz Lüdecke, also her wartime captain.

On 6 April 1913 she sailed with SMS Strassburg to the Adriatic Sea and the Mittelmeer-Division (Mediterranean Division), flanking SMS Goeben (Konteradmiral Konrad Trummler). By late August, Dresden was ordered back to Kiel and sent to the Kaiserliche Werft for an overhaul until December. Her January planned Mediterranean service was cancelled by the Admiralstab and she was sent to the North American station instead, due to the Mexican Revolution. She replaced Bremen, due for replacement by SMS Karlsruhe. Dresden arrived off Vera Cruz on 21 January 1914, still under Erich Köhler, watching over German interests there, and she was later recalled and replaced by SMS Hertha, on a training cruise for naval cadets, and soon Bremen, watching over the evacuation of European nationals on the German HAPAG liners.

On 6 April 1913 she sailed with SMS Strassburg to the Adriatic Sea and the Mittelmeer-Division (Mediterranean Division), flanking SMS Goeben (Konteradmiral Konrad Trummler). By late August, Dresden was ordered back to Kiel and sent to the Kaiserliche Werft for an overhaul until December. Her January planned Mediterranean service was cancelled by the Admiralstab and she was sent to the North American station instead, due to the Mexican Revolution. She replaced Bremen, due for replacement by SMS Karlsruhe. Dresden arrived off Vera Cruz on 21 January 1914, still under Erich Köhler, watching over German interests there, and she was later recalled and replaced by SMS Hertha, on a training cruise for naval cadets, and soon Bremen, watching over the evacuation of European nationals on the German HAPAG liners.

Dresden and HMS Hermione rescued also 900 American citizens trapped in the Vera Cruz hotel, transferred to US warships, by far the largest contingent there. The German consul in Mexico City asked for a landing party from Dresden, created with a Junior Petty Officer and ten sailors armed with two MG 08 machine guns. On 15 April 1914, the cruiser headed for Tampico, Mexico’s Gulf coast. In the meantime, the SS Ypiranga arrived in sight of Mexico with small arms for the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta. But the United States put in place an arms embargo in between, and they intercepted Ypiranga on 21 April. As she was German, Dresden arrived to confiscate officially the merchantman, and officially carry out German refugees out of Mexico, but delivering the weapons and ammunition nevertheless.

On 20 July 1914 the Huerta regime was toppled and SMS Dresden carried Huerta and Aureliano Blanquet (Vice Pdt.) and their families to Kingston in Jamaica, where they were granted asylum. Köhler learned there the situation degrading in Europe and set sail as she needed a refit. She met SMS Karlsruhe in Haiti and on the 31st, under captain Lüdecke, she was prepared for Handelskrieg (commerce raiding war) in the Atlantic instead.

Wartime service

Firing on the steamer SS Mauretania, August 1914

Dresden sailed south under radio silence and was conformed the state of war on 4–5 August, so she started her operations in the South Atlantic, and Brazilian coast. Close to the mouth of the Amazon River, she intercepted her first British merchantman on 6 August, SS Drumcliffe. Next she refuelled with the German collier SS Corrientes and sailed to the Rocas Atoll, escorting the HAPAG steamers Prussia, Baden, and Persia. She set sail for Trinidad, and intrcepted on her way the SS Hyades, then captured the British collier SS Holmwood (24 August). In Trinidade, she met the gunboat Eber and several steamers, replenishing.

On 26 August off Río de la Plata she caught two more British steamers. However due to her worn out condition at this point, her captain decided to stop operations and on 5 September, went to Hoste Island for urgent engine maintenance. Informed by the HAPAG steamer Santa Isabel’s captain from Punta Arenas, on 18 September Dresden’s captain decided to transit via the cape horn, and in the Pacific, she stopped in the Juan Fernández Islands, contacting Leipzig. On 12 October she was affected to Vizeadmiral Maximilian von Spee’s East Asia Squadron, coaling at Easter Island.

On 18 October she joined her sister ship Emden and the East Asia Squadron in a rampage along the South American coast, down to Más a Fuera island (26 October), escorting the auxiliary cruiser SS Prinz Eitel Friedrich and the SS Yorck and SS Göttingen to Chile. While Off Valparaiso they received intel about a British cruiser at Coronel, later identified as HMS Glasgow, forced to leave port due to neutrality rules. However he did not knew he was with the 4th Cruiser Squadron (RAdm Cradock) with Monmouth, Good Hope and MAC Otranto. This encounter led to the battle of Coronel.

On 1 November, at around 16:00, SMS Leipzig spotted first smoke from the British squadron, and the two squadrons closed the distance until fire broke out at 18:34, at 10,400 m. Dresden fired on Otranto making her fled at the third salvo and claimed to have started a fire. Next, she shifted on Glasgow, already duelling with Leipzig. She made five hits and at 19:30, was ordered to launch a torpedo attack. She increased speed in the heavy weather and deterioating sight, briefly spotting Glasgow withdrawing. Dresden met Leipzig and near fired on her in the semi-darkness. By 22:00, with other light cruiser she was deployed in a searching column but never took sight of the British again. She was not hit a single time.

Dresden in Valparaiso, Chile, 13 Nov. 1914

On 3 November Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg sere ordered back to resupply in Valparaiso under neutrality laws (three belligerent warships only) while Dresden and Leipzig remained with the colliers in Más a Fuera. Spee was back on 6 November, sending in turn Dresden and Leipzig to Valparaiso, arriving on 12 November and back on the 18th. On the 21th, the squadron sailed to St. Quentin Bay (Gulf of Penas) to coal while the British Amiralty ordered Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee south with the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, en route from 11 November. They arrived in the Falklands on 7 December, soon joined by the Cornwall, Kent, and Carnarvon, Glasgow and Bristol. The trap was set.

Spee left on 26 November and caught on 2 December the Canadian sailing vessel Drummuir carrying 2,750 t of excellent Cardiff coal. The squadron recoaled at Picton Island, and Spee made a council on 6 December, planning for an attack on the Falklands, to eliminate the large British wireless station there and all coal stocks, despite Lüdecke and Leipzig, Nürnberg captains opposition, preferring to raid La Plata area. Seniority won and ordered were given.

On 6 December afternoon, the squadron departed Picton Island and on 7 December arrived off Tierra del Fuego, and then sighted the Falklands at 02:00. At 05:00, Gneisenau and Nürnberg were detahced to send landing parties and were en route when they spotted at 08:30 smoke raising from Port Stanley’s harbor. Spee realized his error and gave orders to fleet eastwards, rejoining his squadron at 10:45, leaving the German auxiliaries to hide in the islands off Cape Horn. They were soon taken in hot chase by the British. At 12:50, the battlecruisers catched SMS Leipzig and Spee ordered the three light cruisers to escape south, while he would engage the British with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Sturdee then ordered his armored and light cruisers to chase off the German light cruisers. While Spee died in his gallant fight, Dresden’s worn out turbine could not out-run her opposition and Lüdecke wanted her to hide in the islands off South America.

SMS Dresden’s prow, date unknown, Bundesarchiv

On 9 December, she rounded the Cape Horn and entered the Pacific, first dropping anchor at Sholl Bay with just 160 t of coal in store. Oberleutnant zur See Wilhelm Canaris convinced the Chilean naval representative a extra 24h delay to stock extra coal at Punta Arenas, starting on 12 December. She embarked 750 t from a German steamer and the admiral staff hoped she could make a run through the Atlantic and head for home. But still, her turbines would not allow this and Lüdecke wanted to continue his raiding spree in the Pacific, via Easter Island, then heading for the Solomon Islands, Dutch East Indies and operating in the Indian Ocean.

After taking on board 1,600 t of coal on 19 January, she headed for another hideout, making maintenance whith whatever available. On 27 February underway, she captured the British barque Conway Castle, south of Más a Tierra, was resupplied by the German liner Sierra Cordoba, and made another coaling at Juan Fernández Islands. On 8 March, while underway in dense fog, lookouts spotted HMS Kent, engines off, just 15 nautical miles away. Both raised steam, but Dresden recoignising she was a greater adversary managed to escape after a five-hour chase. This depleted her coal stocks and further deteriorating the state of her engines until Lüdecke estimated his ship was no longer operational, and he wanted her to be interned instead. He set sail to Más a Fuera, Cumberland Bay, later confirmed by the German Admiralty, and contacting Chilean officials.

On 14 March however, Kent and Glasgow arrived off Cumberland Bay, but Dresden was stuck. Lüdecke signaled she was no longer a combatant but the British disregarded this and HMS Glasgow soon opened fire, even in violation of Chile’s neutrality, soon joined by Kent. German gunners just had to time to be on battle station and fired three shots until British gunfire knowked them out. Lüdecke signalled “Am sending negotiator”, dispatching Canaris in a pinnace while Glasgow went on shelling Dresden. Lüdecke soon raised the white flag at last. Canaris met Captain John Luce, receiving terms of unconditional surrender, the latter perotesting they were already interned by Chile and saked for scuttling instead. This was done at 10:45 with charge detonated in the bow’s ammunition magazines, crew evacuated. Dresden sank after 30 minutes and as it did, the second scuttling charge exploded in the engine rooms.

Dresden’s white flag, before scuttling

The crew mostly managed to escape, 8 sailors had been killed and 29 wounded in the shelling. The British MAC HMS Orama took the most wounded to Valparaiso. The officeres eventually picked up Chilean warships, then a German passenger ship to be interned in Quiriquina Island. Canaris however would escape on 5 August 1915, making it back to Germany two months later and on 31 March 1917, others escaped and captured the Chilean barque Tinto, reaching in turn the fatherland after 120 days. The wreck was inspected in 2002.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign