France (1891-1926)

France (1891-1926)Admiral Charner, Bruix, Chanzy, Latouche-Tréville

WW1 French Cruisers

Sfax | Tage | Amiral Cecille | D'Iberville class | Dunois class | Foudre | Davout | Suchet | Forbin class | Troude class | Alger class | Friant class | Linois class | Descartes class | D'Assas class | D’Entrecasteaux | Protet class | Guichen | Chateaurenault | Chateaurenault | D'Estrées class | Jurien de la Graviere | Lamotte-Picquet classDupuy de Lome | Amiral Charner class | Pothuau | Jeanne d'Arc | Gueydon class | Dupleix class | Gloire class | Gambetta class | Jules Michelet | Ernest Renan | Edgar Quinet class

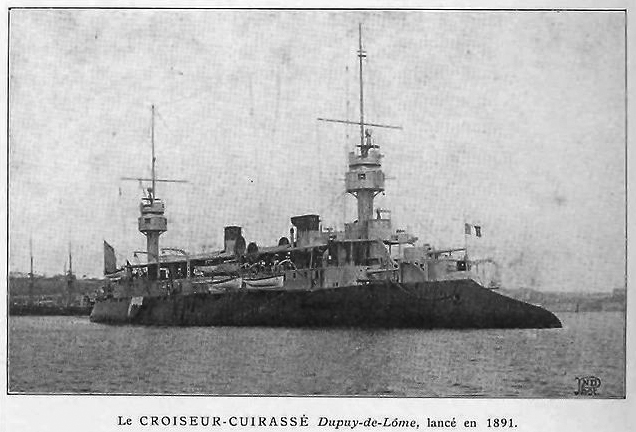

Follow-up cruisers of the Dupuy de Lôme.

The previous Dupuy de Lôme was considered a prototype, an experimental armoured cruiser tailored for commerce warfare. The admiralty recoignised the merits of the design, innovative for them in the line of the young school, and it was decided to create a follow-up class, which consisted of four ships: Admiral Charner, Bruix, Chanzy, and Latouche-Tréville, all launched between 1892 and 1894, and commissioned in 1894 to 1896. Amiral Charner’s keel was laid down in 1889 in Rochefort Arsenal, whereas Dupuy de Lôme was not even launched. These four cruisers were cheaper orginally than their prototype and had an excellent and almost complete protection, very thick at many key points. They traded protection against speed, planned for 19 knots but this was never achieved.

Despite careful maintenance, their machinery was worn out already in 1914 and their top speed averaged 15-16 knots at full speed in service, ludicrously slow for cruisers. They were even left in the dust by the Danton class pre-dreadnoughts among others. Chanzy was wrecked on May 30, 1907 off China while the other three saw action during WWI in the Mediterranean: Admiral Charner was torpedoed by U21, sinking in 4 minutes on February 8, 1916. The other two were disarmed in 1920 and 1926.

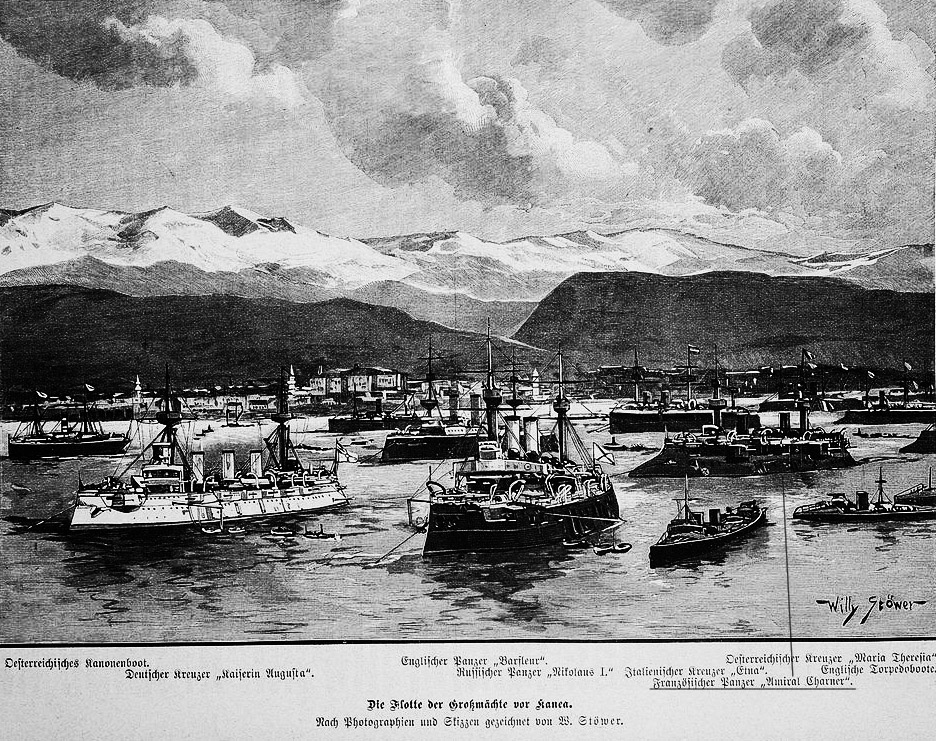

Die Gartenlaube: engraving showing a multinational fleet off Crete in 1897. Admiral Charner is in the background.

Design development

Dupuy de Lôme

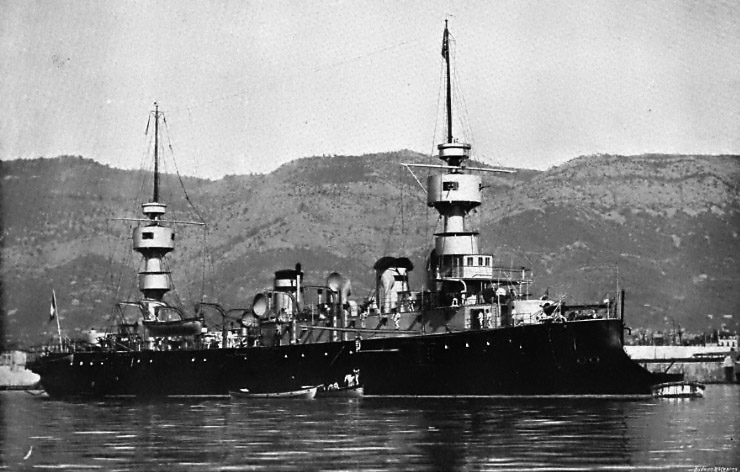

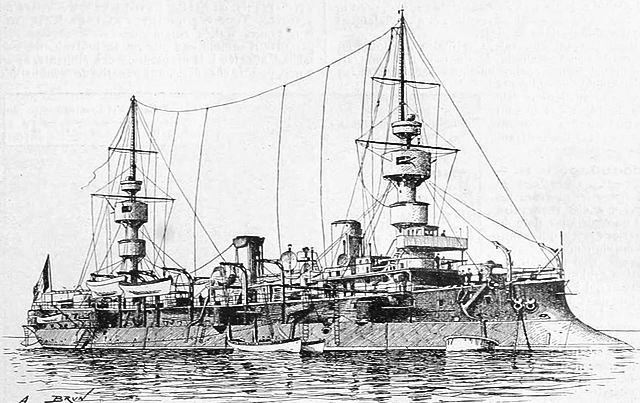

The Amiral Charner-class ships were designed as smaller and cheaper versions of the Dupuy de Lôme but still able to perform the same Jeune École’s commerce-raiding strategy, with the same recipe. All in all they were smaller, shorter at 106.12 metres (348 ft 2 in) long between perpendiculars, but still 14.04 metres (46 ft 1 in) in beam. The normal draught forward was also smaller at 5.55 metres (18 ft 3 in) up to 6.06 metres (19 ft 11 in) aft for a lighter displacement at 4,748 tonnes (4,673 long tons) normal or 4,990 tonnes (4,910 long tons) deeply loaded. From comparison, FS Dupy de Lôme displaced 6,301 tonnes (6,201 long tons), and was 114 meters long and 15.7 meters in beam.

However like the “prototype” they had the signature prominent plough-shaped ram bow and hull tumblehome on both sides. Overall, these features made them very wet forward in heavy weather, but captains generally felt them to be reasonably good sea boats. However they were better suited for the geberally calmer Mediterranean. Their high metacentric height was not compensated by their tumblehome though, and was inadequate. In fact all but the sunken ship at their first important refit had their heavy military masts replaced by simple poles before WW2. There was not so much to retire to their superstructure however. But in appareance they undoubtely looked like thinner French battleships.

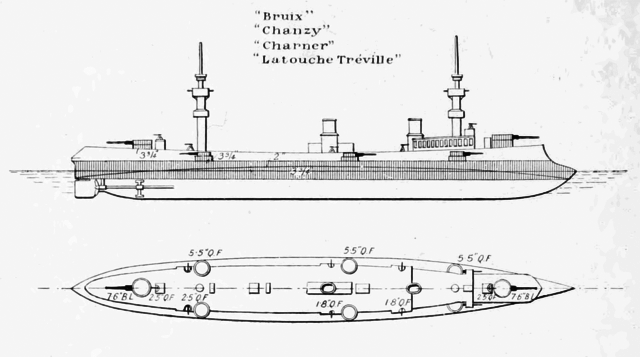

Brassey’s 1902 depiction of the class

Armour Protection

-Both sides were protected by 92 mm or (3.6 in of steel armor, and the belt went down 1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) below and 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) above their waterline. It tapered down from 20 centimetres (7.9 in) in thickness to 60 millimetres (2.4 in) on both ends. Again, Dupy de Lôme had 100 mm belt armor.

-The curved (“turtle”) protective deck was made of mild, not high tensile steel and 40 millimetres (1.6 in) in thickness on the flat section and increading to 50 millimetres (2.0 in) on its outer edges, forming the citadel, unclode by any bulkheads. It was however weaker, only 30 mm for the Dupuy de Lôme. This was the only improved pert in protection on this new class.

-The separated boiler and engine rooms as well as the magazines below were given an extra splinter deck, just 15 or about 1.5 in deep.

-Also for ASW protection their watertight internal cofferdam was filled with cellulose, alla long the protective deck and over 1.2 metres (4 ft) in height above the waterline.

-The below waterline section was subdivided into 13 watertight transverse bulkheads, and there were five more at the upper deck.

-The forward only conning tower, as well as the main turrets received 92 millimeters walls (3.6 in again) against 125 on the Dupuy de Lôme.

Detailed plans of the Latouche-Tréville

Machinery

The Amiral Charner-class were given two horizontal triple-expansion steam engines. Each drove a single propeller shaft based on the steam provided by sixteen Belleville boilers working at 17 kg/cm2 (1,667 kPa; 242 psi). The total provided reached 8,300 metric horsepower (6,100 kW) under forced draught, a far cry from the 13,000 hp of their forebear. This lack of power was criticized early on, and Bruix was modified by the engineers with more modern boilers, to reach 9,000 metric horsepower (6,600 kW). Designed speed was 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph), not stellar for cruisers in the 1890s, but during sea trials they even failed to meet these figures.

Instead by pushing ther machinery hard, some reached 18.4 to 18.6 knots at best (34.08 km/h or 21.17 mph), based on a total output ranging from 8,276 to 9,107 metric horsepower (6,698 kW) on Bruix. The range was “Mediterranean”, with only 535 tonnes (527 long tons) of coal carried for just 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). This was quite feeble for commerce raiding to say the least. They did not fared better than the previous Dupuy de Lôme but the latter was at least faster, reaching 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

Armament

Main:

All four cruisers mounted just two two 7.8 in/45 guns “Canon de 194 mm Modèle 1887” mounted in single turrets fore and aft of the superstructure. Turrets were hydraulically operated, however on Latouche-Tréville, electrical power was tested. These fired a 75–90.3-kilogram (165–199 lb) shell at 770-800 m/ second (2,500 to 2,600 ft/s) and range of circa 12,580 yards (11,500 m) at 14.5° and possessed a 2 rpm ideal rate of fire.

Secondary:

It comprised six 4.5 in/45 “Canon de 138.6 mm Modèle 1887” guns also single gun turrets on each broadside, close to tge fore and aft main guns, creating triangle patterns either side. They fired 30–35 kgs (66–77 lb) shells at 730-770 metres/second (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s). Range was circa 16,400 yards (15,000 m) at 25° elevation according to navweaps (so yes, different max elevations made the secondaries firing further than the main guns…). Rate of fire was double that of the 194, at 4 rpm.

Light guns

For close-range anti-torpedo boat defense the Admiral Charner class were defended by:

-Four quick-firing 2.6 in (65 mm) guns. Derived from the 57 mm Hotchkiss in 1888, they Fired a 9.0 lbs. (4.1 kg) shell at 2,346 fps (715 mps).

-Four QF 1.9 in (47 mm). The 3-pdr equivalents were very popular, also buuilt under licence and used by the British and US navies.

-Eight QF 1.5 in (37 mm) five-barreled revolving Hotchkiss guns. The latter were Gatling-like 6-barreled 20 caliber “heavy machine guns” firing explosing shells at short range, not on the torpedo boats but the torpedoes themselves in an attempt to detonate them, or just when vessels were close enough. It’s possible wheeled underarriage were carried to have them mounted and carried with a landing party.

Note: All three were made by Hotchkiss, an American engineer which not finding application at home for his patents, was convinced to settle in Europe and choose France to create his company. His light guns and machine guns range became almost the standard in the years between 1875 and preceding WW1. Event WW2 IJN light artillery still derived from his models.

Torpedo Tubes

All four cruisers were armed with four 450-millimetre (17.7 in) pivoting torpedo tubes: Two of these were mounted on each broadside, firing above water. Thanks to this they were easier to reload by being centralized and avoid potential weakness points in the hull. Currently i have no info on these models.

Construction and Modernizations

Amiral Charner was originally built in Arsenal de Rochefort, laid down on 15 June 1889, launched on 18 March 1893 and completed on 26 August 1895. Bruix was laid down on 9 November 1891 at the same yard, launched on 2 August 1894 and completed on 1st December 1896. Chanzy was built at Chantiers et Ateliers de la Gironde, Bordeaux, laid down on January 1890 and launched on 24 January 1894 and then completed on 20 July 1895. And Latouche-Tréville was ordered from Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée in Granville, laid down on 26 April 1890 and launched on 5 November 1892 the, completed on 6 May 1895. Chanzy was lost in 1907 and not modernized, but all three others, were. Charner was sunk in WW1 by an U-Boat, the two remaining ones, Latouche-Tréville and Chanzy surviced the war and received a few alterations until their decommission between 1923 and 1926.

The main early modifications consisted, not soon after sea trials, but in the 1910s to correct their stability issues by removing their thick military masts fitted originally, replaced by light pole masts. Light armament of six 1-pdr (37 mm) and four 2 pdr (47 mm) as designed was removed in the 1910s. Later in 1914, 76 mm (3-in) guns, were fitted with high angle mounts for AA defence with the 65 mm kept for after WWI. There is no known modification made after WWI.

Admiral Charner – Old illu by the auhor

Ad. Charner Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 106 x 13.97 x 6 m () |

| Displacement | 4,681 tonnes standard, 4,737 tonnes Fully loaded |

| Crew | 393 wartime |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts VTE, 16 Belleville boilers, 8,000 hp., 19 knots. |

| Speed | 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 8,870 nmi (16,430 km, 10,210 mi) 19 knots (35 km/h, 22 mph) |

| Armament | 2 x 193, 6 x 140, 4 x 65 mm, 4 x 457 mm TTs sub. |

| Armor | 92 mm belt, 110 mm turrets |

General assessment of the class

Lackluster but active records

Amiral Charner spent most of her career in the Mediterranean after commission. She was sent to China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900–01, assisting the international fleet into retaking the Taku Fortd. With Chanzy and Latouche-Tréville back in th Mediterranean, after a refit in Toulon, she took part in the International Squadron gathering off Crete during the 1897-1898 uprizing and Greco-Turkish War. They were there to protect French interests and evacuate citizens. As said above, Amiral Charner succumbed to the torpedoes of an U-Boat in early 1916, sinking very rapidy with just one survivor. It showed the extreme vulnerability of vessels built before ASW warfare became a concern. The compartimentarion could not stand the flooding created by several torpedo hits at once. In fact all 1890s French vessels were similarly at risk and there were many losses.

Apart Bruix, like her the sisters from 1900 up to WW1 she was already considered obsolete and retired from the frontline, kept in reserve, with brief period as training ship. Bruix served in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean, Far and by aided survivors of the Mount Pelée reuption, Martinique, French West Indies or Carribeans. Bruix was decommissioned in Greece by 1918 and recommissioned but after some home reserve was recomm; to take part (the only one in her class) to the Black Sea attack against the Bolsheviks. Back home she was discarded in 1920 and scrapped in 1921.

Chanzy was a guardship off Crete but transferred to French Indochina in 1906 and ran aground off the Chinese coast, proving impossible refloat and therefore scuttled and everything valuable evacuated after the crew was rescued without loss. It was uncommon at the time off China as the coast was till not accurately mapped.

The second ship to be sunk was bay enemy action in WW1. Charner, Tréville, and Chanzy escorted troop convoys from French North Africa to France from August 1914 and the first two were reassigned to the Eastern Mediterranean blockading Ottoman coast, supporting Allied operations in the Dardanelles. She was also part of the French rescuing operation, taking aboard several thousand of persecuted Armenians, fleeing to the coast from Syria. Their guns stopped the chasing Ottoman troops.

Latouche-Tréville was also damaged by gunfire in 1915 dueing the Gallipoli Campaign. She had bee sent to assist in the capture of the German colony of Kamerun (Dec. 1914) and after the Dardanelles, she patrolled for a year the Aegean Sea and Greek waters. She became a training ship in late 1917. She was obsolete by that time and this was safe decision. She would be decommissioned in 1919. She returned home later, reduced to reserve before sold in 1926, the last to be scrapped.

A deceiving bunch

So all in all, these vessels were slow, making them unable to join most fleet exercizes in the 1900s, and in 1914-17 the suviving ships took part in several operations but never had to face Austro-Hungarian guns. Two dealt with Ottoman fortifications in the Dardanelles, but the rapid loss of Charner showed they ASW protection was woefully adequate and had been originally intended to resist to relatively light shell damage. They never fulfilled the promises of the Jeune Ecole and could not be integrated in the new armored cruiser tactics intended to serve in close coordination with the fleet like at Jutland. They still were useful as gun platforms and saw relatively “cushy” assignments, seeing many operations still despite their age.

Mecanically, these cruisers had scores of problems and issues revealed by initial sea trials and spent another year or more in fixes and overhauls. One, Bruix was even plagued by eight major issues and had two at sea collisions during her career. The loss of Chanzy in the far east was a combination of brash decision by the captain to cross a dense fog instead of waiting the weather cleared out, but heavy weather soon plagued effort of pulling her free when she was stuck on unchartted reefs, seen far too late to act. So overall, between their lenghtly consrtruction, lenghty post-trials fixes, numerous refits, stability and engine problems, and long period of reserve or total inactivity, these cruisers, coming straight from the delusions of the Jeune Ecole were not a bargain for the taxpayer. Still, for these 1890s vessels, three took part in WWI whereas many protected cruisers and pre-dreanoughts of the same era did not.

A curtailed legacy

The next Pothuau (1895), sole in her class.

The next armoured cruiser class, Pothuau (1895) was larger but armed with more guns, and with a different armour scheme plus secondary guns in casemates. Still, she was only able to reach 19 kts, and not successful either. In fact she was the last of the Dupy de Lome lineage. In 1896, after leaving some time for reflection, the admiralty built a brand new, far larger armored cruiser that was this time geared towards a more sensible speed, and like Pothuau returned to casemate guns instead of turrets. This was the Jeanne d’Arc (launched 1899) which proved instrumental for spawning a whole new trend in large fleet armoured cruisers, unlike the Jeune Ecole commerce raiders. She was followed by the Gueydon, Dupleix, Gloire, Gambetta classes or the 14,000 tonnes Quinet class, which were arguably far better. These constituted a modern force of 19 powerful cruisers, highly regarded in international circles, the last being commissionned in 1911. We will in the future cover all these.

Sources/Read More

Books

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Feron, Luc (2014). “The Armoured Cruisers of the Amiral Charner Class”. Warship 2014.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; Seaforth

Johnson, Harold & Roche, Jean P. (2006). “Question 22/05: French Amiral Charner Class Cruiser Differences”. Warship International. XLIII

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Seaforth Publishing

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Links

On navypedia.org

On battleships-cruisers.co.uk

navires-14-18.com/ pdf FR

On fr-academic.com

On militaer-wissen.de

wiki

Detailed plans of Latouche-Treville

Plans of the next Pothuau

Model Kits

Not very inspiring to manufacturers. Not even Kombrig had a go on these. Scratchbuilders, your take !

Gallery

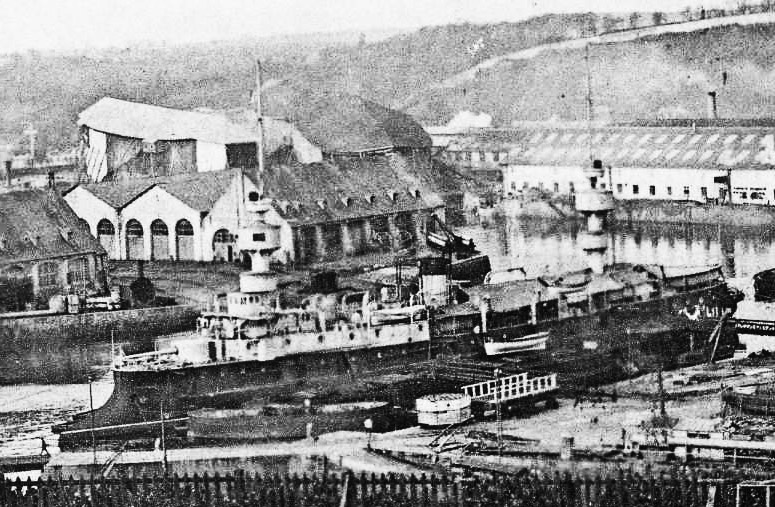

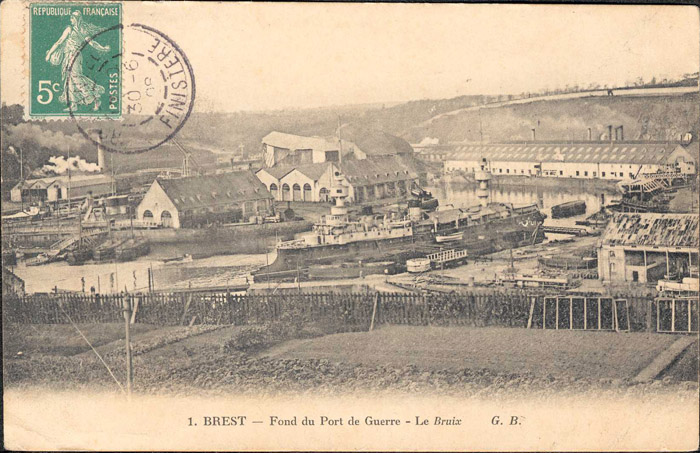

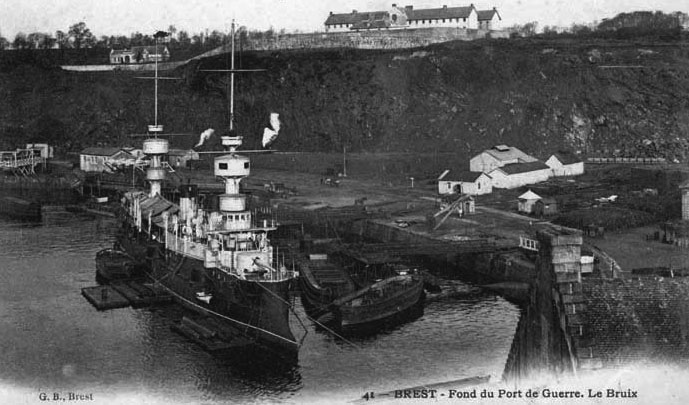

Bruix in Brest, Postcard and detail

Transfer of the body of King George I painted by Chatzis Amphitrite. Bruix is in the escort

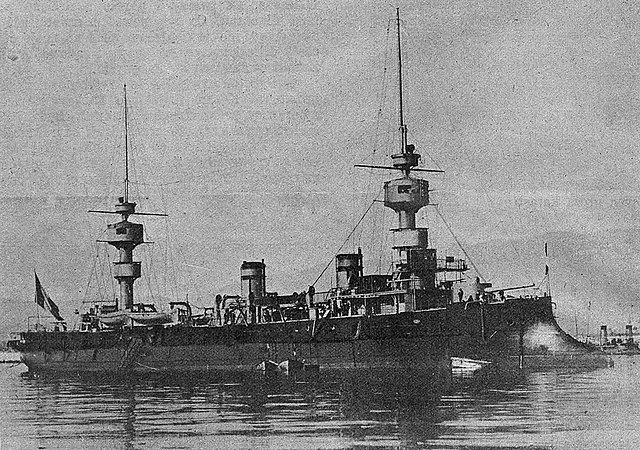

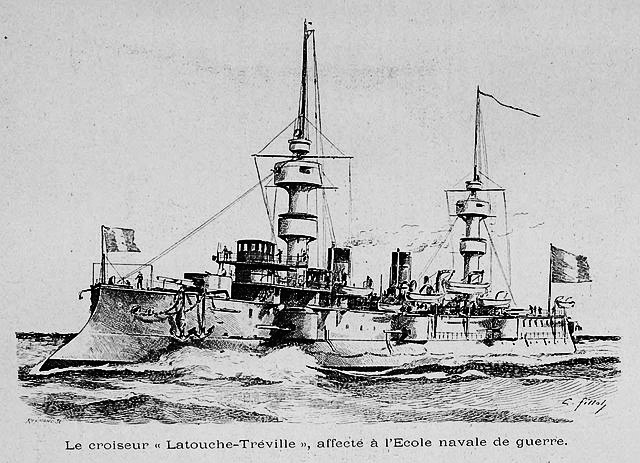

Latouche-Treville in 1908

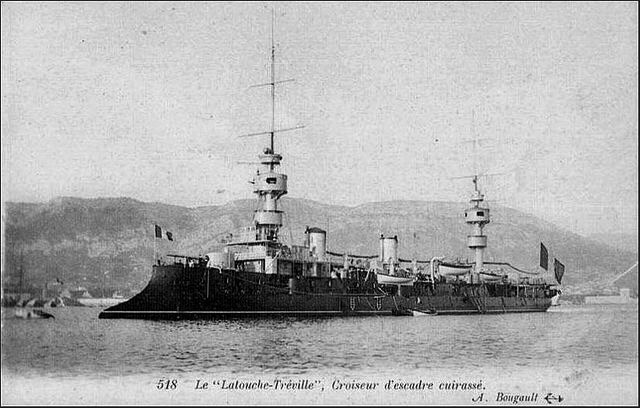

Treville by Bougault

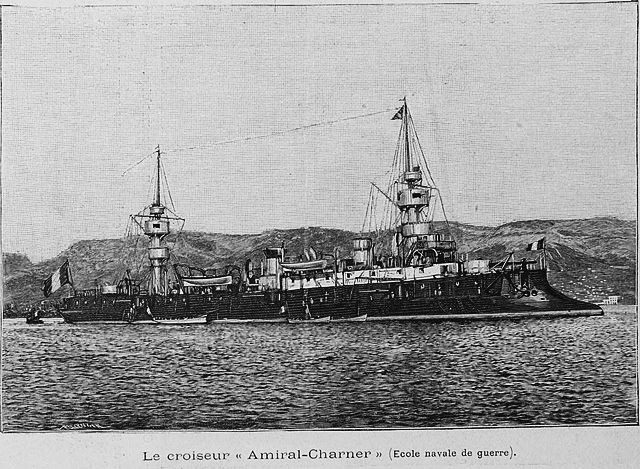

Amiral Charner

Amiral Charner

Charner in l’illustration, 1896

Amiral Charner was named after Breton Admiral Léonard Charner (1797-1869), with the campaigns of North Africa, Crimea and China to its credit. He also was the captain of the steam-driven man-o-war Napoléon in the 1950s. The ship bearing his name was the first. The cruiser was laid down at the Arsenal de Rochefort, simply nameed “Charner”, as lead ship in 1889 and after commission on 26 August, was assigned to the 2nd Light Division, Mediterranean Squadron but detached in the Eastern Mediterranean as tension rose between the Greeks and Ottomans.

On 6 January 1896, she became flagship of the Higher Naval War College (“École supérieure de guerre de la marine”). She was found at the head of a unit also comprising her sister Latouche-Tréville and the protected cruiser Suchet. Together, they prepared officers for command duties at sea and staff management in realistic conditions. She returned to the active fleet on 20 October. The ship was sent to Crete on 10 February 1897 to protect French asset and evacuate citizens as the Greco-Turkish War rage on, but also other western citizens. By November 1898 she returned home.

Amiral Charner was reassigned to the naval college, on 1 January 1899. There, she servved with the protected cruisers Friant and Davout. Then she was reassigned to the Northern Squadron based at Brest, NW France, for about 6 months before returning in her homeport in Toulon by late June. After three months she was back to Brest, but placed in reserve.

She was fully reactivated on January 1900 and sailed to Rochefort for a major overhaul, including the change of steam-piping for a long deployment in the Far East. She departed Brest on 26 June to arrive in Saigon in what was now the colony of French Indochina, on 1st August. Since she was close, she took part onthe early part of the allied offensive during the Boxer Rebellion (1901) and returned to Toulon on 8 November. After a new refit, she joined the 3rd Armored Division on 24 January 1902.

Amiral Charner in Toulon

The annual summer naval maneuvers this year saw her simulating a defending vessel in a scenaro where a fleet went into the Mediterranean from the Atlantic and attacked Bizerte in Tunisia while blockading ports. At last she was placed in reserve in Toulon, from 15 January 1903, given to the gunnery school in 1910. On 13 May she returned to Crete, Souda Bay, to act as a guardship, later relieved by Bruix in July 1912. She was sent in drydock and modernized (see modifications) but afterwards stayed in reserve, at Bizerta.

As war broke out in August 1914, she was fully recommissioned for service and at first escorted several troop convoys bertween Morocco and France with her sisters Latouche-Tréville and Bruix. In November 1914,she joined the 3rd Division, 3rd Squadron based in Port Said (Egypt).

There where she shelled Ottoman positions on the Syrian coast, but ran aground under enemy fire off Dedeagatch in Bulgaria (3 March 1915). This imposed the concerted effort of several shuips including the powerful Italian cargo liner SS Bosnia to be pulled out. She teamed in August with the battleship Jauréguiberry and cruiser Destrées for a coastal blockade between Tripoli, Lebanon and El Arish in Egypt. On 11–12 September, she rescued 3,000 Armenians north of the Orontes River Delta, literraly from the jaw of death, with Ottoman troops behind. She next covered the occupation of Kastelorizo island on 28 December with Jeanne d’Arc.

However on the morning of 8 February 1916, while Sailing from Ruad Island off Syria to Port Said in Egypt, Amiral Charner was spotted and ambushed by the German submarine U-21 (U19 class, 1912). She sank in just two minutes with the loss of 427 men and a single survivor later rescued five days later. Due to the lack of testimonies but the noted kill on the U-Boat’s diary, it was assumed she took three torpedoes in a row, hence the rapid flooding and capsizing of the vessel. Other survivors would probably managed to stay afloat for days afterwards, but drawn or died due to exhaustion before beign picked up.

Bruix

Bruix

Bruix in Brest, date unknown

Bruix (named after Napoleonic Admiral Étienne Eustache Bruix, 1759-1805) was commissioned for trials on 15 April 1896 and assigned to the Northern Squadron to be present for a state visit of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his wife in Dunkerque (5–9 October). Her steering however broke down on 7 October so she was sent to Rochefort for repairs. Trials resumed by December and she was recommissioned on the 15th, returning to the Northern Squadron. By 18 August 1897, with Surcouf, she escorted Pothuau with President Félix Faure aboard on a return visit to Russia.

But while en route, Bruix fractured a piston rod in her port engine and again, had to fold back for repairs. This was followed by armament trials until January 1898 so that the overall trials were at last complete on 25 February, eight years before construction start !. Bruix was reassigned to the Far Eastern Squadron based in Saigon, French Indochina, reaching there and being present until October, making in between a visit to Manila on 5 May to assist the remains of the Spanish Armada in the bay after the Battle of Manila Bay. In November, she while underway in the Suez Canal, the black serie of mishaps went on: She damaged her starboard propeller while transiting, but this did not hampered her to join her new home port of Toulon on the 28th. Repairs lasted until January 1899 after which she returned to the Northern Squadron on 3 February.

She visited before getting there ports in Spain and Portugal by June but another piston rod broke on the 7th and repairs were prolongated by a refit on 20 September, until 4 November 1900 modified as flagship. On 20 November she headed the northern cruiser division. In 1901, she took part in the annual fleet maneuvers with the Northern Squadron and its divisions but, fifth career incident, she collided with the British steamer SS Paddington. She had to return in port to have the plating of her armored ram repaired on 27 June. At this occasion since she was in drydock it was decided to fit her with bilge keels by November–December to improve stability. She remained in dockyard until 10 January 1902, this time ro fix her defectuous turrets. Reassigned to the Atlantic Division by April 1902 she toured Spanish ports until May.

After the cataclismic eruption of Mount Pelée on 5 May in the French Carribean, Bruix as flagship, RADM Palma Gourdon rushed to Fort-de-France for assistance to possible survivors, also carrying a small scientific party. She stayed in place and remained until 19 August. On 30 November RADM Joseph Bugard replaced Gourdon and Bruix back home spent the next years between reserve or limited training service with reduced crew.

She was fully reactivated in late 1906 to join the Far Eastern Squadron, leaving Toulon on 15 November, with her sister ship Chanzy, transiting Suez, crossing the Indian Ocean and reached Saigon on 10 January 1907; For the first time afterwards Bruix visited Japan, dropping anchor in Nagasaki. Meanwhile Chanzy ran aground off the Chinese coast, on 20 May. Bruix attempted to tow her out without luck. Chanzy was abandoned. Bruix showed flag in Vladivostock, in China and Japan before regaining home on 26 April 1909. Whilke transiting the Suez Canal, she collided (7th incident!) with the Italian steamer SS Nilo. She was in Toulon on 2 August for repairs and an overhaul lasting for weeks, but the latter in a context of anarchist troubles, was delayed by labor shortages. Towed to the dockyard at Bizerte in North Africa by June 1911 her overhaul was completed there at last in January 1912.

Keratsini photo showing Bruix on 6 jan 1917 with Ambassador Guillemin and embassy personal and officers on the cruiser

She then rejoined the reserve, but was recommissioned on 13 May and reassigned to the Levant Division, sent to safeguard or evacuate French citizens and their assets in Crete as guardship. She relieved Amiral Charner at Souda Bay on 9 July; After wards she spent two years with the Levant squadron. As the Italo-Turkish War commenced, her captain tried to interpose as fleeing Turkish troops were shelled by the Italian cruiser Coatit near the port of Kalkan, on 3 October. It was at the time a breach in international law.

On 8 November 1912 she assisted the relfoating of the Russian protected cruiser Oleg. Reassigned to the Tunisian Squadron on 13 January 1913, she remained in the Levant and assisted to salvage this time the steamer SS Sénégal hitting an Italian mine off Smyrna in Turkey. By March 1914 she escorted the Prince of Bulgaria, William, from Trieste to Durazzo in Albania, claiming his throne. Bruix next was back to Bizerta on 25 April 1914 for another refit until July 1914. War was looming at the horizon.

By August 1914 she was tasked to convoy escort between Morocco and France, also patrolling French and North African waters with Latouche-Tréville and Amiral Charner, fearing a raiod from Souchon’s Mediterranean squadron. Bruix next was tasked to join the Allied armada deployed for a campaign against German held-Kamerun in September 1914. She shelled several small towns and folded for home. After a short refit, Bruix was reassigned to take part in the allied fleet deployed for the Dardanelles campaign in February 1915.

Bruix in Salonica, 1917

She did not took part in the shelling, instead patrolling the Aegean waters in 1916-17. On 31 January 1918, she was placed in reserve in Salonika, but recommissioned on 29 November 1918 to join the allied occupation fleet gathered in Constantinople, and reassigned to the armored cruiser division, 2nd Squadron. In March-May 1919 she was in the Black Sea to take part in the support of “white russians” against the Bolsheviks. She also evacuated German and Allied troops from Nikolaev in Ukraine (March 1919) and Odessa (April 1919).

She departed the Black Sea back for Constantinople on 5 May and from there, transited the hallipoli slot and headed back for Toulon on 22 May, assigned to the reserve. The admiralty agreed due to her past problems, age and desig, she was no longer relevant and was to be scrapped. There was though the intervention of a buyer (which previous resold the Dupy de Lôme to Peru) and if the admiralty thought of converting her as an accommodation, the conversion to a merchant ship was judged impractical. She was stricken on 21 June 1920, sold in 1921 for scrap for 436,000 francs.

Chanzy

Chanzy

Chanzy’s engraving in the “Larousse Mensuel”, 06 August 1907.

Chanzy (named after General Antoine Chanzy of Franco-Prussian War fame) was ordered in Chantiers et Ateliers de la Gironde, commissioned for sea trials on 6 February 1895. Like Bruix she was plagued with so many problems that her engines and boilers needed an overhaul. She was decommissioned for repairs starting on 6 December and recommissioned a second time on 1 May 1895 followed by a new serie of sea trials which revealed nothing serious and she was granted service on 20 July.

Assigned at first to the 1st Light Division, Mediterranean Squadron, she was transferred to the 4th Light Division on 18 May 1896. After the annual fleet maneuvers she was reserve/repairs/refit at Toulon when ended with new trials on 28 December 1896. By 16 February 1897, she was sent off Crete as part of the International Squadron (Austro-Hungarian, Imperial German, Italian, Russian, British Navies) deployed to protect their citizens as the 1897-1898 Greek uprising on Crete against Ottoman Empire.

By March 1897, she was sent to Selino Kastelli, southwest Crete, to sent a landing party, part of a larger expedition rescuing Ottoman troops and Cretan Turk civilians from Kandanos. The International Squadron stayed until December 1898 but Chanzy departed on 25 February for home. Back to the reserve squadron she was only reactivated for the annual naval maneuvers. On 1 January 1899 she joined the 1st Light Division, visiting the Balearic Islands and touring the Aegean Sea and Middle East.

Her main steam pipe fractured on 20 February (injured three) and she was repaired, participating in the next annual maneuvers. For three weeks in September she was attached to the old Couronne (1861) before starting a cruise of French North Africa. She was briefly reassigtned to the Levant Sqn. on 1 February 1901 and by 4 April returned for the annual maneuvers and back to the Levant in October. She was back in Toulon on 1 February 1902 for a long inactivity in reserve, replaced by the brand new armored cruiser Marseillaise from May 1904.

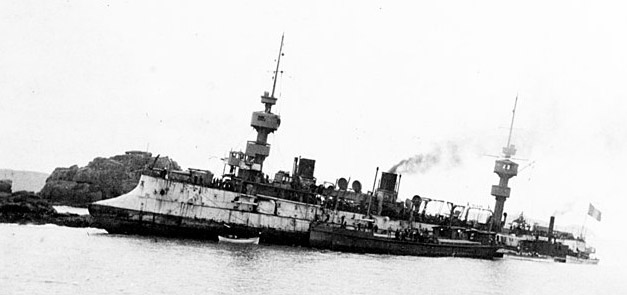

Chanzy after running aground, 30 May 1907

Chanzy was recommissioned on 15 September 1906, this time to take her tout of duty in the Far Eastern Squadron. She departed on 15 November, arrived at Saigon on 10 January 1907, visited Hong Kong and toured the Chinese coast, Japan by April-May. However as she was underway from Shanghai on 20 May, thick fog hampered her voyage and she ran aground on an uncharted rocks off Ballard Island, Chusan Islands. Bruix, D’Entrecasteaux, Alger tried to pull her out, but in vain. She was definitely stranded and operations were frustrated by heavy seas. The crew remained aboard, throwing everything they could out but the enterprise was recoignised as futile and they were evacuated without loss on 1 June. By that time the cruiser, badly battered for days, started to fracture and eventually foundered, her wreck being a navigation hazard, was demolished later on 12 June and the remainder was left in place for many more years to rust out.

Latouche-Tréville

Latouche-Tréville

Latouche-Treville off Piraues harbor, 13-20 January 1907

Latouche-Tréville (named after Vice Admiral comte de Latouche-Tréville (A hero of the American War of Independence and revolutionary wars like Lafayette)) was built at Granville shipyard, Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée. She was commissioned for sea trials on 16 October 1893, the last of the class and already obsolescent. Contraty to her sister her initial trials seemed successful at first but still, some problems required over a year and a half of work before definitive commissioned on 6 May 1895…

Latouche-Tréville assigned first to the Northern Squadron in Brestn, and participated in a fleet review attended by newly elected President Félix Faure on 6 August 1895. She was transferred to the 2nd Light Division, Mediterranean Squadron arriving in Toulon in January 1896. For a short time she was assigned to the Higher Naval War College, training future officers with her sister Amiral Charner and Suchet. Next she was sent to the Reserve Squadron on 20 October. She too, was sent to Souda Bay in Crete by 17 March 1897 to support the international coalition during the Greco-Turkish War. She remained until 24 June and folded home.

On 18 October she was reassigned to the light division, Mediterranean Fleet, until 22 July 1904. In 1906-1908 she was partly in reserve with reduced crew but took part in yearly summer exercizes. By April 1899 she took part in a fleet review honoring King Umberto I of Italy at Cagliari in Sardinia. She also took part in combined fleet maneuvers with the Northern Squadron by June–July 1900. By 19 July she took part in anoher fleet review. Gunnery training on 24 January 1901 shown blast issues with her forward turret, that had to be repaired.

These took place bertween 1 February and 1 May, and while in drydock she received bilge keels to start adressing her stability issues. By October 1901, Latouche-Tréville was sent in the port of Mytilene and landed two Marine companies occupying major ports of the island on 7 November as to pressure Turkey into honoring its contracts with France. Sultan Abdul Hamid II agreed to enforce these and grant French companies the insurance of repaying past loans contracted to French banks.

On 18 December 1902 there was a gale in Toulon, and the steamer SS Médoc reupture its anchor lines and went drifing onto Latouche-Tréville’s ram. The steamer was gushed and had to be run aground to avoid sinking. The cruiser remained perfectly unscaved. She was sent in the eastern Mediterranean next, based in Syra, Cyclades, Aegean islands on 7 May to 16 December 1903. While back home she visited Naples in April 1904 with the entire French Mediterranean Squadron. She also took part this year to the spring cruise in the the eastern Mediterranean.

Back in Toulon she was placed in reserve on 22 July, replaced by the new armored cruiser Kléber in the light division. Her light Hotchkiss artillery was removed but she gained four extra 47 mm guns. Electrical system was upgraded and many other modifications were made. Recommissioned on 15 February 1907, she was assigned to the gunnery school.

In March during another refit her torpedo tubes were removed. On 22 September 1908, her aft turret saw one loaded guns misfiring as the breech opened, igniting propellant, which blew the breechblock through the turret door. The sighting hood was detached and projected into her deck the ship’s crew (and a catastrophic explosion) were avoided, as a brave gunner closed the door between the magazine and ammunition hoist. Nevertheless the whole gun crew was burnt to death, all fourteen plus five were wounded but badly burnt.

Repairs were completed on 1909 but it was decided to place her in reserve on 1 January 1912. Latouche-Tréville was recommissioned on 20 November and sent to the Levant Squadron, leaving Toulon on 10 December for Port Said, Egypt, arriving on 16 December 1912. Like her sister ship she was also refitted in Bizerta (Tunisia) from 8 November to 26 December 1913, having her military masts replaced by light poles. She spent the rest of the year and next in Egypt.

Illustration of the Treville in 1896

Latouche-Tréville on 29 July 1914 was recalled in Bizerta as international situation degraded, prepared fpr war. She unloaded surplus equipment and like her sisters Amiral Charner and Bruix, was reassigned to escort troops convoys between Morocco and France. Next she was sent to blockade the Strait of Otranto, until 5 February 1915, and reassigned to the Dardanelles Squadron. She did not took part in the operation but instead joined the Syrian squadron on 20 March, to shell Ottoman installations at Gaza. Her gunners also claimed a railroad bridge at Acre (Palestine).

The cruiser was back in the Dardanelles on 25 April, this time providing fire support on 4 June. But an Ottoman 210 mm (8.3 in) replied and hit her aft turret, killing two men inside, wounding five. She was then transferred to the Aegean for ASW patrols on 17 June-20 August. Next she was sent in Toulon for repairs and refit, ending on 21 September 1915.

She was then sent back to the Aegean, supporting Allied forced off Salonica. But an epidemic burst aboard, so much that her crew was badly crippled. It was decided wiser to send her back off Toulon in quarantine, arriving on 5 January 1916 to be disinfected. A refit follow, and crew’s rest, after which she was prepared for operations in February. She spent 1916 in the central and eastern Mediterranean, making a large number of diverse missions. At last she was placed in reserve (December 1917), used with a reduced crew as a gunnery training ship, still in these waters. She was back in Toulon on 31 December 1918 to be decommissioned on 1 May 1919. She was stricken on 21 June 1920, hulked, but she was sold to a salvaging company that fitted cranes on her gutted deck to try saving the battleship Liberté’s wreck. She was then turned into a accommodation ship and floating workshop from 4 September 1920, and until 1925. She was this time sold for scrap a year later, the last of her kind. Dupuy de Lôme, her sister, and Pothau were now all gone.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign