The first and last Chinese battleships

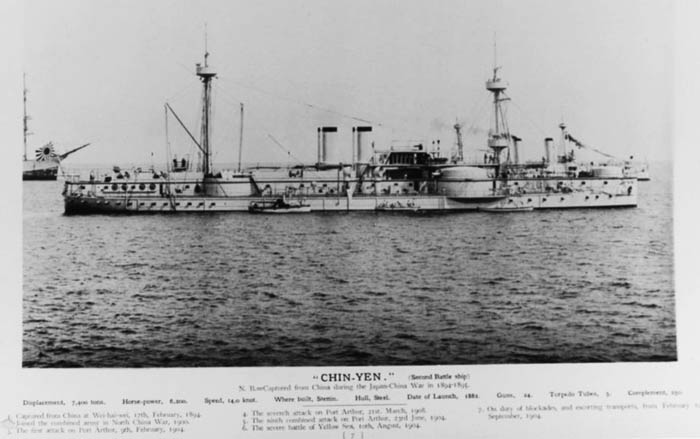

The present ironclads had many names, in modern Chinese called 定远, they were known in pinyin as Dìngyǔan and in the Wade–Giles dictionary Ting Yuen or Ting Yuan. With her sister-ship Zhenyuan, Dingyuan was the largest military ship ever to bear the flag of Imperial China, and the largest until the 1990-2000s aircraft carriers of the Chinese PLAN. Both served for a mere ten years before being thrown into battle during the first Sino-Japanese war in 1894. Scuttled at Port Arthur and captured, Zhenyuan changed flag, entered service in the Japanese Imperial Navy as Chin Yen an saw the Russo-Japanese war; became a coastal defense ship, a target ship and eventually was sold for scrap in 1912.

Context: Chinese Ironclads against foreign Imperialism

In 1880 China was about to meet a storm of new Western ingerence. Already marked by the souvenir of the French-British alliance during the Second Opium War from 1857 to 1860, France, not to be left over for possible spoils of war started to settle permanently in Vietnam under the pretext of protecting Catholic missions here, following the shelling and occupation of Tourane (Danang) and Saigon in 1858. The next step was the constitution of the French colony of Cochinchina by treaty in 1862, and gradually took over other territories through forced protectorates. However this move provoked a reaction from China as Hanoi was annexed in 1882. The war was declared in 1883 and would be lost in 1885, leaving the French in partial control of additional territories, namely Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina, Cambodia, and Laos. Before that, China saw with growing uncertainty the rise of British and German appetites in the region and ordering modern battleship (at the same time of many other ships) was a sure way to prevent any further advance.

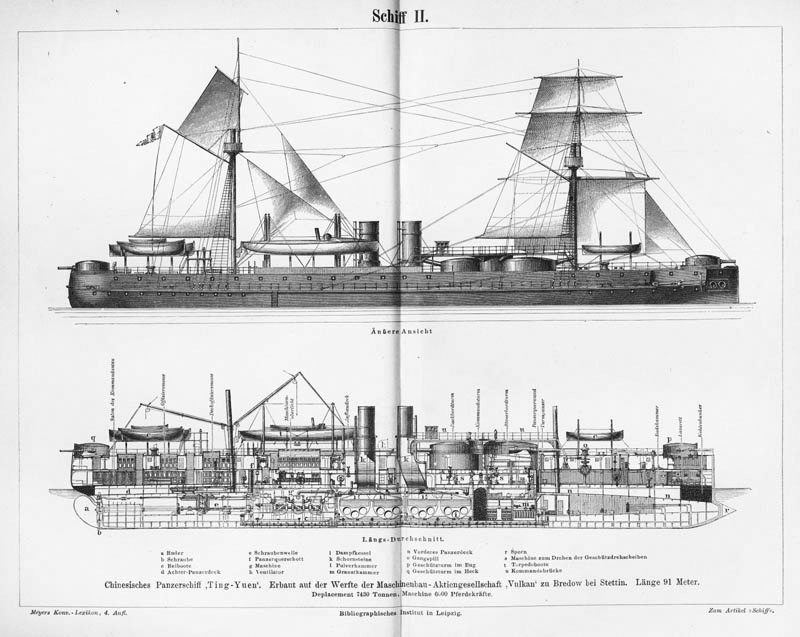

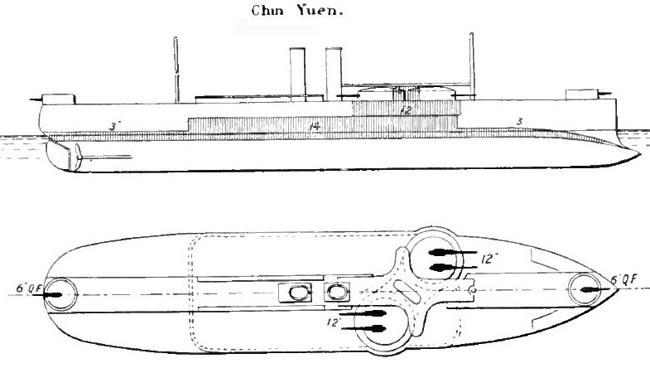

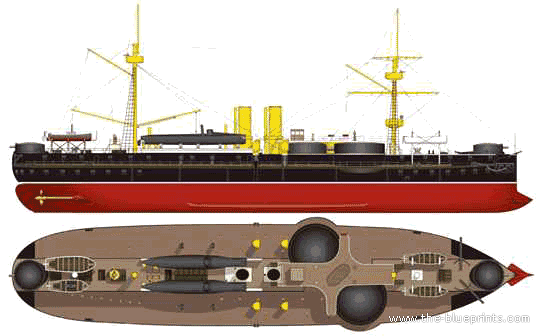

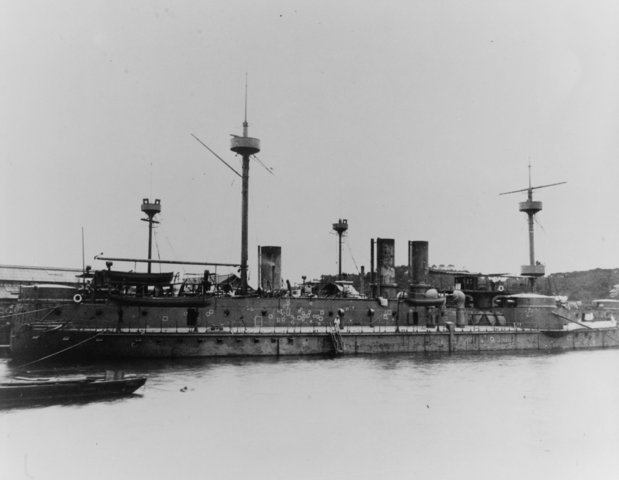

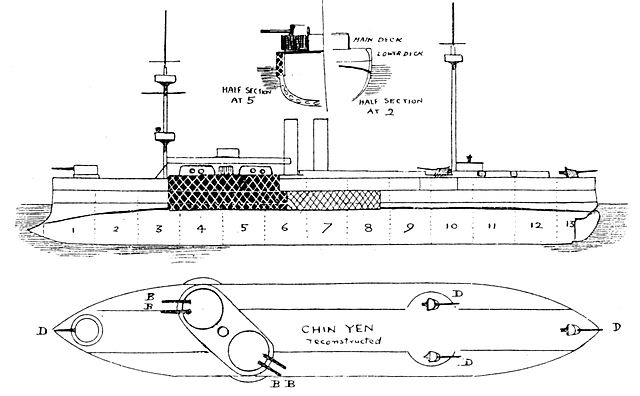

Brasseys diagram – IJN Chin yen.

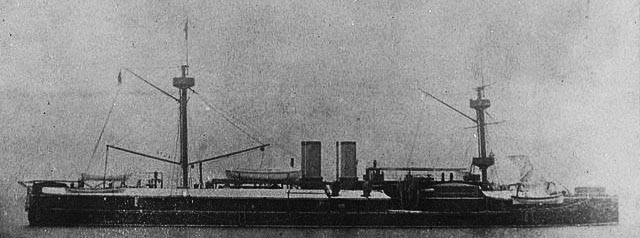

Until 1880, the only modern fighting ships of the whole Chinese Navy was a pair of screw frigates called the Hai An class, also comprising the Yu Yuen. Both wooden-hulled frigates has been ordered at Kianyan yard for the Nanyang fleet, using skills and blueprints from the West. Classic sailing and steam vessels they possessed two deck 9-in guns mounted on rotative cradles and twelve 70-pdr broadside guns, plus one funnel. Launched in 1872-73 they were considered unseaworthy. The Yu Yuen was sank by and was sunk at the end of the war in 1885 by spar-torpedo boats from the cruiser Bayard while Hai An survived the war and was later rearmed by Krupp guns (fate unknown). In 1879 however, the Beiyang fleet’s governor ordered two protected cruisers to British yards, the Chao Yung class, launched in November 1880 and January 1881. Both were sank at Yalu in 1894.

The Beiyang fleet quicky became the largest and most modern of the three Chinese Imperial Fleets, as alongside the new ironclads for the sold year of 1883 as war with France started, the cruiser Chi Yuan was ordered to Vulcan in Germany, followed by the three Kai Che class for the southern fleet (Nanyang) (at Foochow on German plans but with German and British guns), and the three Nan Yang class in 1883, the first two at Howaldt in Germany and the third locally at Foochow, while the Beiyang fleet received in 1886 two British-built protected cruisers (Chih Yuan class) and in 1887 the same fleet ordered in Vulcan, Germany again, two armoured cruisers, the King Yuan class, and at Foochow was built the Ping Yuen, an armoured cruiser launched in 1888, and last major ship accepted before the 1894 war.

Compared to this, the Ting Yuen (Or Dingyuan) class represented certainly the greatest endeavour of China, for the northern (Beiyang) fleet, facing Japan and Russia. The order to German yards was motivated to find an alternative to British yards, which also aggressively pushed their luck in the region, and naturally to a willing enemy of France and Japan, the greatest threat for China at that time. By that time Germany was a rapidly growing industrial superpower, traduced also into a dynamic expansion of its Kaiserliches Marine. Prominent German yards of that time, Vulcan and Kiel Dyd just delivered the first modern (sail only) central citadel ironclads whereas Norddeutsche and Dantzig Dyd delivered the Bismarck and Carola class iron corvettes. The four Sachsen class ironclads (launched 1877-80) carried the DNA of the Chinese ships, which were not modified copies but more conventional ships. But the true reason behind the German order was that if UK has been considered first, diplomatic authorities barred them as unwilling to sell China warships of this size, notably to not offend the Russian Empire, an ally at that time.

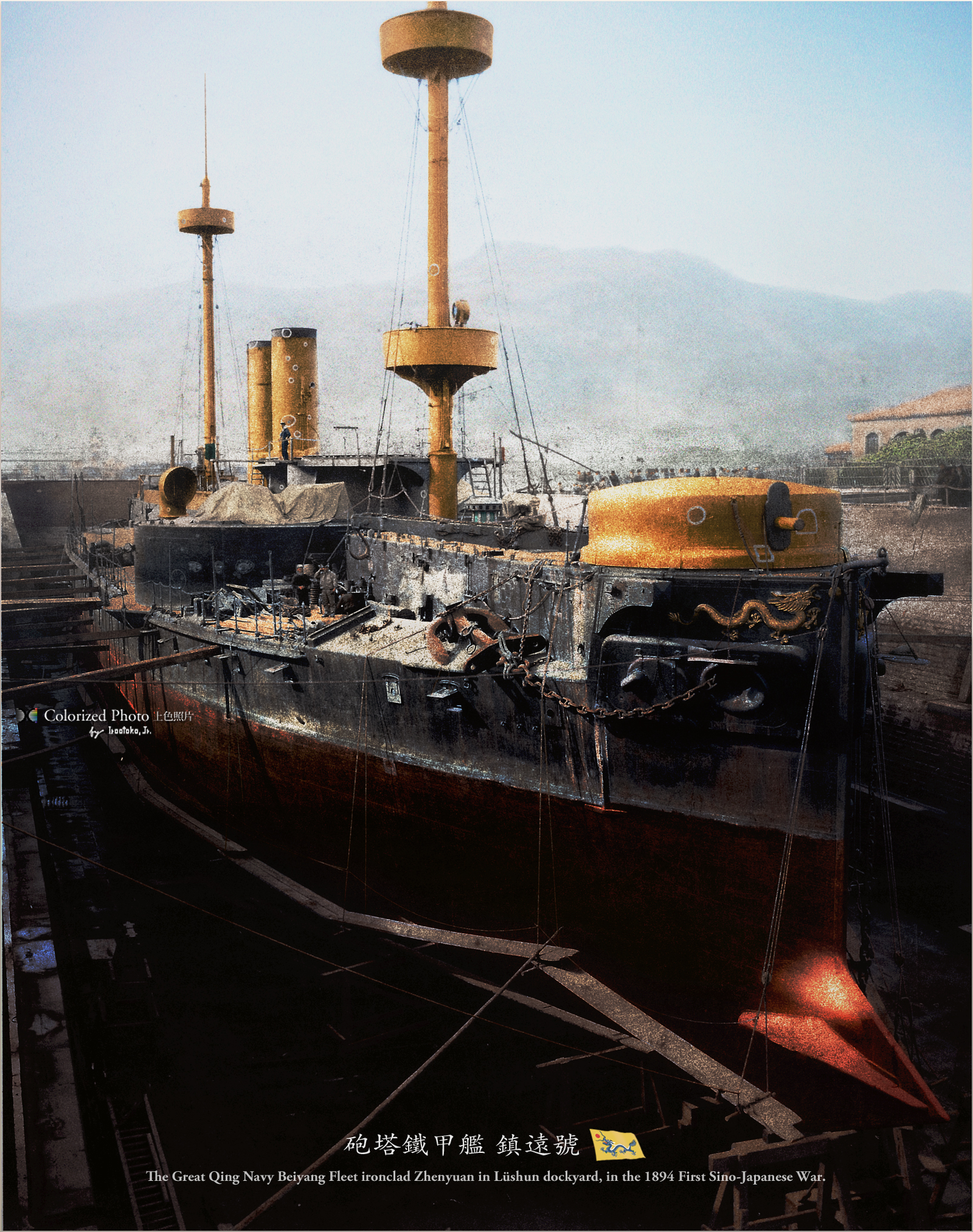

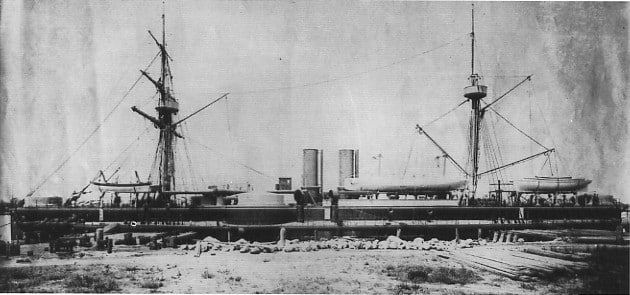

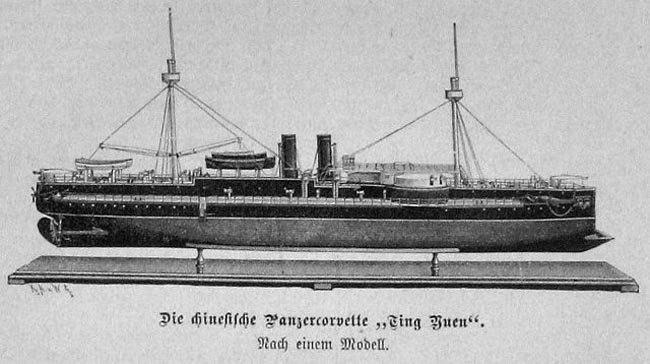

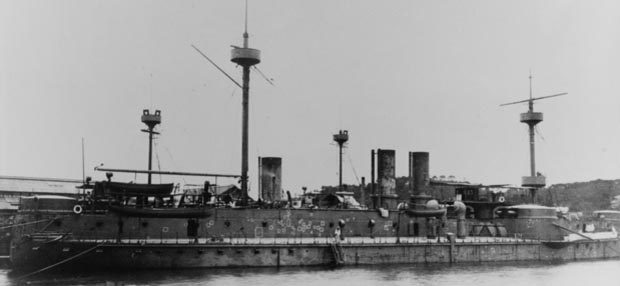

Zhenyuan in Lushun dockyard – colorized by Irootoko Jr.

design of the Dingyuan class ironclads

Describing the Dingyuan class as a mere copy of the Sachsen, designed earlier in 1874, would be an error. Both were flush-deck ships, with two funnels, about the same displacement at 7600 tons and dimensions, but the similarities stopped there. By their armament, both ships were completely different animals. The Germans choose for their Sachsen class three sets of 26 cm guns, two mounted side by side in a pear-shaped barbette on the forecastle and six in individual positions in a “X” pattern at the rear. The Dingyuan however were designed to carry a very standard combination: Two barbettes of twin 12-in guns (305 mm) in a classic “echelon” -or lozenge- configuration, typical of the time. All four 30.5 cm guns were 20 caliber Krupp pieces. The secondary armament also diverged greatly (see later).

The SMS Baden, from the Sachsen class which came from the same yards at that time.

On the powerplant side, the Sachsen class opted for two shafts HSE steam engines, about 5000 shp for 13 knots, whereas the Chinese vessels had two shafts connected to two trunk steam engines fed by 8 cylindrical boilers, and were rated for 7200 ihp, reaching 15.4 knots (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph). These were much better performance at equal tonnage. On the range side, the Chinese ships reached 4,500 nmi (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) whereas the Sachsen were limited to 1,940 nmi (3,590 km; 2,230 mi) at the same speed. That’s a paradox that’s these ironclads, comparable in many aspects and coming from the same yards diverged so greatly.

Perhaps we should consider the budget allocated to the Chinese Ships (6.2 million German gold marks, equivalent of around 1 million Chinese silver taels.) far outclassed those consented for the four German ships, in an Empire that existed since a mere ten years, even if Otto Von Bismarck was behind. The Navy at that time, under General Albrecht von Stosch was indeed conceived as a defensive, near-coastal navy, whereas Chinese plans led by the Viceroy of Zhili province, Li Hongzhang, included at first no less than twelve ironclads to face the IJN Fusō and Kongō classes under construction in UK.

Hull of the Dingyuan-class

Since German yards, contacted by the Chinese, accepted to make a derivation design from the Sachsen, the ships had relatively a similar hull.

Both ironclads measured 308 feet (94 m) in length (between perpendiculars) and overall 298.5 ft (91.0 m), for a beam of 60 ft (18 m) and 20 ft (6.1 m) draft. They displaced 7,144 long tons (7,259 t) on paper, estimated to 7,670 long tons (7,793 t) fully loaded. Their steel hulls from Krupp were well built and strong, ending forward with a pronounced ram bow following the trend of the time.

Steering depending of a single rudder. Differing from the Sachsen, there were two heavy military masts instead of just one, one forwards of the main battery guns and one aft. There was also a hurricane deck which ran over the turrets from the foremast to the funnels. Also customary of the time, both ironclads were motherships for two second-class torpedo boats. They were stored astern of the funnels, moved by, and recovered by derricks to the sea. By default of reports of them in action we can assume they were only useful by very calm sea. The Dingyuan class ships carried 363 officers and enlisted men.

Armament of the Dingyuan class

Both ironclads were given a main battery comprising four 12 in (305 mm) 20-caliber guns in two open barbettes placed in échelon on the forward part of the deck. Barbettes on Dingyuan and Zhenyuan were indeed placed in a very common configuration at that time, compact enough as to allow concentration of armour, forward and rear fire of both barbettes, and side fire of both cpmbined when the angle allowed it. The starboard barbette was indeed placed further forward than the port one. The guns were 31.5-long-ton (32 t) Krupp models but the relatively low hull and configuration caused trim problems and both ships were wet forward.

DingYuan 1884 – The blueprints. Notice the midget torpedo boats installed in the center gangway in between the funnels and mast.

The secondary armament was composed of two 5.9 in (150 mm) guns in single mounted turrets, on the bow’s deck forward and in the stern. This was relatively unusual at the time. Torpedo boats closer defence was assumed by a pair of 3-pdr or 47 mm (1.9 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon plus eight 2-pdr or 37 mm (1.5 in) Maxim-Nordenfelt QF guns placed in casemates.

At last, there were also three 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes, of which one was firing at the stern, and the other two forward of the main battery above water, broadside. There are some conflicting data about 381 mm tubes also.

Powerplant of the Chinese ironclads

Both Ironclads were fitted with two horizontal, three-cylinder trunk steam engines (HTE). They drove each a single bronze 3-meters screw propeller. They were fed by the steam from eight cylindrical boilers, which exhausts passed through truncated tubes emerging into a pair of funnels amidships. The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms for better safety. Total output as indicated was 6,000 horsepower (4,500 kW). Top speed ad designed was 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h; 16.7 mph), exceeded on trials: Zhenyuan for example generated 7,200 ihp (5,400 kW) for 15.4 kn (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph). For supply, both vessels carried 700 long tons (711 t) of coal and up to 1,000 long tons (1,016 t) in wartime, allowing them to reach their cruising radius of 4,500 nautical miles (8,300 km; 5,200 mi). The reasons they were given two masts also went with the installation of spars carrying sails for the voyage from Germany to China. But after arriving there, it seems decision was taken to remove them as well as the rigging, and the masts later would receive military tops.

Protection

It consisted in a central “immune zone” protected by a belt armour 14 in thick, partial whereas a 3 in (76 mm) armoured deck ran the entire length of the ships. The barbettes of the main armament were protected by 12 in (305 mm) thick plating. The conning tower had walls 8 in (20 cm) thick. The 5.9 in guns (150 mm) in turrets were protected by 0.5 to 3 in (13 to 76 mm) thick armour plating.

Career of the DingYuan class ships

Both ships were completed in early 1883 and 1884 and were to sail to China with a German crew. However there were delays as France tried to prevent them to sail, following the outbreak of the Sino-French War in 1884. They were kept in Germany pending the diplomatic resolution of the matter. Menawhile, a German crew fire tested Dingyuan at sea, showing the generous gun blast was enough to caus onboard glass to shatter, and one of the funnels was damaged. Fortunately for both parties, war ended in April 1885, and both ironclads were allowed to sail for China, along with the armoured cruiser Jiyuan, also purchased there.

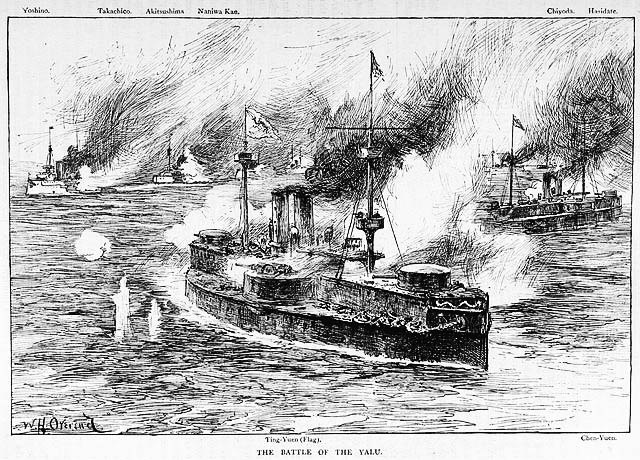

All three ships arrived in China in October 1885. They were formally commissioned into the Beiyang Fleet and Dingyuan became its the flagship. When the first Sino-Japanese War erupted she was under the command of Commodore Liu Pu-chan and also carried Admiral Ding Ruchang while her sister-ship Zhenyuan was under command of Captain Lin T’ai-tseng. Both would see combat at the Battle of the Yalu River on 17 September 1894. They were captured by the Japanese and entered a new career.

The DingYuan and Zhenyuan in action

Dingyuan was being manned by German crews when she sailed with her sister ship and armoured cruiser ordered by the Chinese government on 3 July 1885, under the German flag. The squadron arrived in Tianjin in November before being were transferred officially to the Chinese Beiyang fleet. Li Hongzhang, Viceroy of Zhili, was also director of China’s naval construction program. He inspected the ships and impressed, gave the greenlight for their commission into the Beiyang Fleet based in Port Arthur. However the squadron soon steamed south, to Shanghai, escaping the harsh northern Chinese winter.

The Beiyang Fleet spent years in a routine of winter training cruises in the South China Sea, operating in coordination with the Nanyang Fleet. The ships often stopped in the Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces, and sometimes in Southeast Asian ports. In the spring and summer they saild back to their homeport, operating the Zhili, Shandong, and Fengtian provinces home waters for more training exercises. They also frequently made long range training cruises to foreign ports, up to the early 1890s. These allowed to validate navigational skills and to show the flag.

However as it was soon noted by foreign observers, discipline onboard was poor, and generally the ships were not in full readiness. Commander of the Beiyang fleet was Admiral Ding Ruchang, which raised his mark on the Dingyuan. Another problem for the yearly maintenance of those ship was China’s lak of facilities, of dry docks large enough to house them. The navy had to send them to Japanese shipyards or in British Hong Kong.

Dingyuan started another training cruise in April 1886, joint manoeuvrers with the Nanyang Fleet, and a naval review in Port Arthur. This was followed by a visit of British vessels at the China Station in May 1886. Dingyuan with her sister ship and four cruisers made an overseas cruise in August 1886, stopping in Hong Kong, but also Busan and Wonsan in Korea, and as far north as Vladivostok and Nagasaki in Japan in August.

When this happened, Chinese crewmen fought apparently with Japanese locals which stroke back, called the police, and killed eight Chinese sailors while two Japanese police died too in the incident, with 44 more Chinese and 21 Japanese injured. The “Nagasaki Incident” was amplified by the Japanese press, leading to calls for a rapid naval expansion notably to counter the Beiyang Fleet. This pushed the government to order three Matsushima-class protected cruisers but also to refuse to the Chinese ironclads to use their shipyards. Therefore the Beiyang Fleet was left to Hong Kong as only possible maintenance yards, and their state degraded.

1887 saw no particular event, both ships operating in the Bohai Sea. Four European-built Chinese cruisers joined the Beiyang fleet this year, strengthening the fleet, and more large scale manoeuvres were needed by 1888 to bond the crews and combine the fleet more efficiently. The Beiyang Fleet ships wre repainted also this year. They had the standard livery of the time, similar to British ships, with a black hull, white superstructures and buff paint (canvas beige) for funnels, masts, air intakes.

In 1889, the Beiyang fleet was large enough and experienced enough to be separated into two divisions. Dingyuan with several cruisers form the first one. The squadron was sent off Korean waters, stopping at while Zhenyuan and the rest of the fleet remained in the Bohai Sea for exercises. The two divisions rendezvoused in Shanghai in December, thereafter proceeding to Hong Kong for Zhenyuan and Dingyuan to be drydocked. They then cruised off Korea and visited Japan in the summer of 1891, Kobe by 30 June and Yokohama on 14 July, landing there a large Japanese delegation of senior military commanders and members of the imperial family received the ships. Another voyage to Japan took place the following year but fuelled growing tensions between China and Japan, especially after the Hongzhang incident. The Chinese made clear of their naval superiority on Japan every-time, which did not improved the situation. The core of the dispute was Korea, a co-protectorate of China since the Convention of Tientsin of 1884.

The first Sino-Japanese war

In early 1894, the Korean Donghak Peasant Revolution pushed China to send a 28,000 infantry expeditionary corps to suppress the rebellion. Japan saw that move as a violation of the Tientsin Convention and reacting by sending 8,000 troops which soon clashed, leading to a formal declaration of war on 1 August. However the new IJN Combined Fleet wrecked the Chinese Hongzhang support fleet, never updated or properly maintained. Moreover even the Beiyang fleet was crippled. For example the funds for new quick-firing guns destined to upgrade the Zhenyuan and Dingyuan were instead allocated to fund the lavish 60th birthday of the Dowager Empress Cixi. Commanders and crews also lacked training due to lack of funds, preventing the use of live ammunitions. To add to this, Japanese broken the Chinese diplomatic codes in 1888 and tapered into Chinese communication.

The Chinese officers also ordered to remove the gun shields from the main battery turrets fore and aft as experience at the Battle of Pungdo shown these thin shields generated deadly splinters when struck, explaining the casualties on the cruiser Jiyuan during the battle. The crews placed coal bags around the gun batteries as improvised armor instead. They were repainted light grey also for concealment. The Beiyang Fleet steamed to Taku in order to resupply.

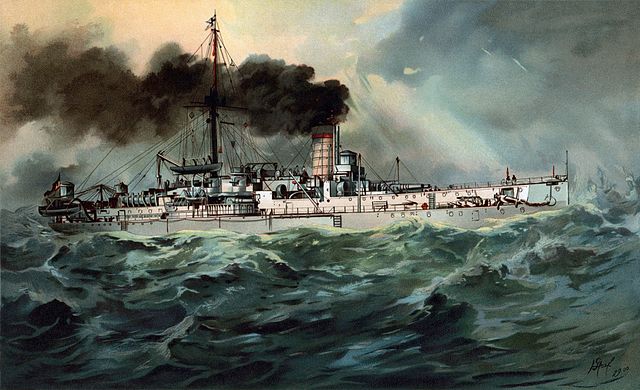

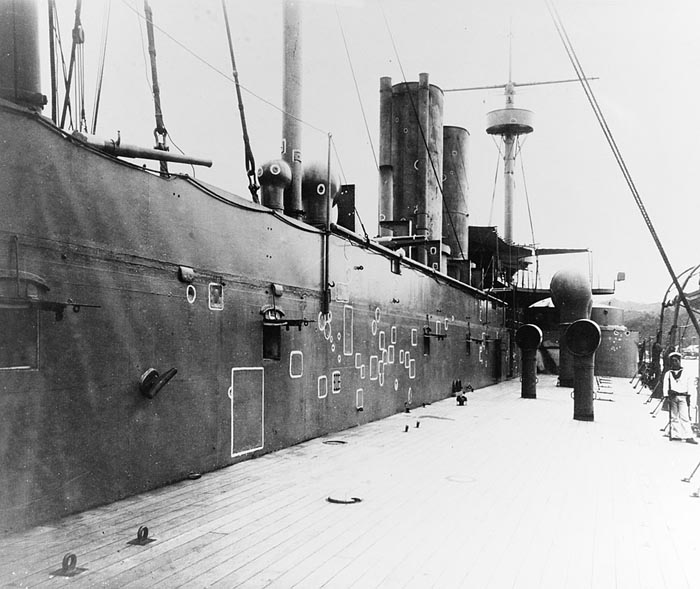

The Ding Yuen at Port Arthur

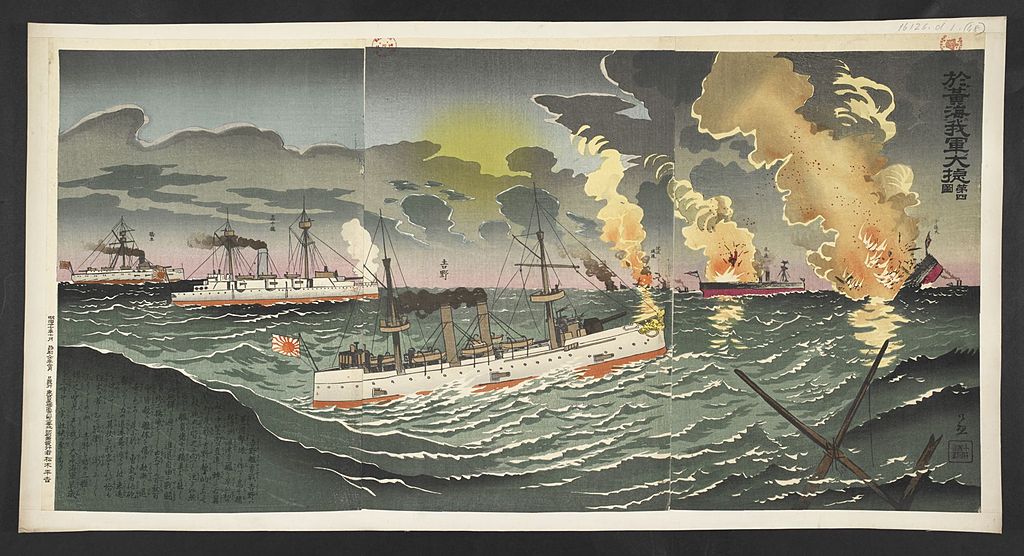

The Battle of the Yellow River

Prior to the battle, admiral Ding sent his squadron into the Korea Bay, on 12 September, in order to clear the path of an upcoming convoy of troopships. Receiving faulty reports of IJN ships off the Shandong Peninsula, the squadron rerouted, but finding nothing, was back in Weihaiwei and met with the troop convoy on 15 September. Troops and supplies were landed at the mouth of the Yalu River, the following day while the squadron stayed further back to provide distant support and intercept possible offensives while staying out of harm of possible Japanese TB attacks from the coast. As the operation ended as a success, the squadron made its way back to Port Arthur. But they were intercepted by the IJN Combined Fleet under Vice Admiral Itō Sukeyuki, starting the Yalu river battle.

The battle of the Yellow sea

Immediately the discrepancy in training showed as the Chinese Beiyang Fleet sailed in a disorganized line abreast formation. The IJN approached them from the south in line and quickly had all their guns aligned in an ideal arc of fire. Respective fleets were slow, 6 and 10 knots (for the Japanese), as the Chinese protected troop transports. Then the IJN combined fleet passed in front of the Beiyang fleet, “crossing its T” but did not opened fire. Impatient, the Chinese admiral ordered to the Dingyuan to open fire at 5,300 yd (4,800 m) range, far beyond the capabilities of firing control.

However, unexpectedly the blast effect collapsed the bridge and the admiral and staff were trapped below, curtailing any chances of the fleet for effective control. Each ship had to fend off for itself during the battle. Dingyuan however went on leading the pack, failed to score any hits and five minutes after the Japanese Fleet opened fire in turn, now making two squadrons encircling the Beiyang fleet, now fish in a barrel. The battle degenerated in almost an execution, the Chinese cruisers Yangwei and Chaoyong being sank first, followed by the cruisers Zhiyuan and Jingyuan. The Chinese scored some hits on the ironclad Hiei though, and the only seriously damaged IJN ship by both Chinese ironclads was the auxiliary cruiser Saikyō Maru.

The Battle of Weihaiwei

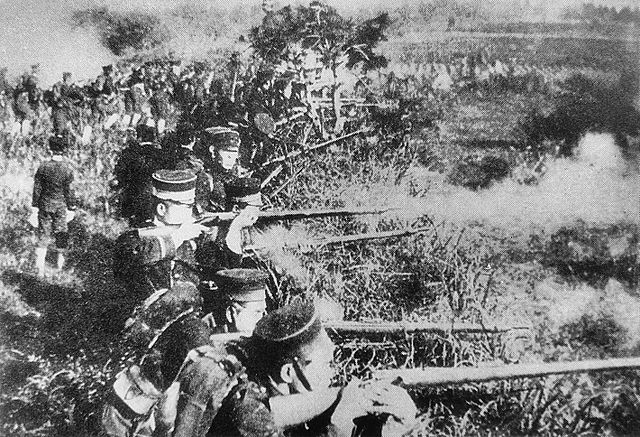

Japanese troops besieging Weihaiwei

The wounded and crippled Chinese Beiyang fleet stayed at Port Arthur to resupply and for repairs while the Japanese reinforced their squadron. However in October, Japanese troops approached Port Arthur, foring the Chinese to sail to safety at Weihaiwei. Admiral Ding ordered the sortie on 20 October, crossing free of harm the Bohai Strait. However since Weihaiwei did not possessed the facilities of Port Arthur, the damaged battleship Zhenyuan had to stay behind to complete repairs and Ding had to return there to cover its move in November. This was successful and both battleships were reunited. But Weihaiwei was soon in January threatened in turn by the advance of the Japanese army. On 30 January, what is called the Battle of Weihaiwei started as a siege by Japanese troops. Despite covering fire from the harbour’s fleet, the Japanese captured the eastern side fortifications. The Japanese then captured the eastern fortifications and turned their guns to the harbour. The fleet moved on the western side, and replicated.

Dingyuan fired and hit one of the 9.4 in (240 mm) guns in the fortress at Luchiehtsui. However the Japanese became more accurate, while the Chinese fleet bombarded the Japanese advance through the remaining fortifications. During the night of 4-5 February, IJN torpedo boats broke into the harbour and launched a successful attack:

The scenario was applied again in the opening hours of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 inside Port Arthur. Dingyuan was hit with a torpedo on the port side, and started to list as the poorly maintained watertight doors failed to close. The flooding became so bad the captain, after ordering to raise steam, made them beach on flat ground and then use her as a stationary battery. The morning saw admiral Ding raising his mark on the ZhenYuan and the Chinese successfully disabled two TBs during the night. The following night however the Japanese TBs attacked again, sinking a cruiser and an auxiliary cruiser. However by 9 February, the Japanese successfully took the remaining fortifications, and now were able to place their field artillery in range.

A crippled Ting Yuen after the night torpedo attack

They rained down fire on the Beiyang fleet, and crippled the already beached Dingyuan. Soon, the remainder of the ships were also damaged including Zhenyuan, never properly repaired after the Yellow river battle, and no longer seaworthy. Admiral Ding Ruchang knew that with another IJN squadron at sea probably waiting for him to exit the harbour, and a long trip south, his better option was to scuttle the ships. He surrendered on 10 February. It was an humiliation that led most officers to commit suicide, including Liu Buchan, Zhenyuan’s captain. Ding Ruchang committed suicide himself, and the Japanese took possession of the harbour and ships. They decided to blow up the beached Dingyuan as they were unable to salvage her, whereas her sister-ship was captured.

The damaged vessels were inspected after by the Vice Admiral Edmund Fremantle on HMS Edgar.

First IJN battleship: Zhenyuan Under Japanese flag as Chin Yen

The badly damaged Zhenyuan was still floating and although damaged, she could be towed to a yard, repaired and reconditioned to IJN service. At first she was formally seized as a war prize, then summarily repaired, and then refloated and later towed by the Saikyō Maru to Port Arthur. This was quite a precious prize which motivated the expenses and energy spent on her. Indeed by that time the IJN had no battleship, only the Hei, an old, barely modernized ironclad and a few armoured cruisers. She was commissioned into the Japanese Navy on 16 March under the Japanese version of her original name. The IJN Chin Yen was dry-docked from April to June for extensive work. A team inspected her closely to assess the battle damage, writing reports for future improvements on IJN ships. They notably concluded that side armor should be further strengthened.

IJN Chin Yen then departed Port Arthur to Nagasaki, arriving for a great victory ceremony, and as the Japanese Navy new flagship. This was the start of a triumph tour of Japan, Hiroshima, Kure, and Kobe. She arrived in Yokohama for further repairs and improvements in the Yokosuka Naval District, gaining new fire-control directors, and a new secondary battery. For the rest of her career there will be a dedicated post in the future. Let’s just say the IJN Chin yen participated in the Boxer Rebellion and battle of Tientsin, Russo-Japanese war as part of the 5th Squadron, 3rd Fleet and flagship of Vice Admiral Kataoka Shichirō, blockading port Arthur and saw action in the second Battle of the Yellow Sea on 10 August 1904. She later covered the landings on Sakhalin and after the war became a coastal defense ship and training ship until decommissioned in 1911. Her anchors were donated back to the Chinese Nationalists on May 1947 and are now in a Peking museum.

As a final note, the Chinese government decided in 2003 to commemorate this war and the Beiyang Fleet, to construct a replica of the battleship Dingyuan at Weihei (former Weihaiwei) on a 1:1 scale, as an anchored museum ship. Its accuracy is debatable. The original was found in 2019 and about 200 artefacts recovered, sent to the museum ship.

Splendid depiction and cutaway of the TingYuen – credits: http://modelshipwrights.kitmaker.net

Another cutaway at mil.huanqiu.com

Characteristics 1882 |

|

| Displacement: 7,220 long tons – 7,670 long tons (7,790 t) Fully Loaded | |

| Dimensions: 94 x 18 x 6.1 m (308 x 59 x 20 ft) | |

| Propulsion: 2 shafts CSE*, 8 FT boilers, 7,200 hp, 15.4 knots (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph) | |

| Armour: Belt 14 in, Deck 3 in, Barbettes 12–14 in, CT 8 in | |

| Crew: 350 | |

| Armament: 4 x 305 BL, 2 x 150 BL, 2 x 47, 6 x 37 mm, 3 TT 356 mm sub. | |

Sources/Read More

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Feng, Qing. “The Turret Ship Chen Yuen (1882)”.

Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World’s Navies, 1880–1990.

Lai, Benjamin (2019). Chinese Battleship vs Japanese Cruiser: Yalu River 1894.

Lardas, Mark (2018). Tsushima 1905: Death of a Russian Fleet.

Leyland, John (1909). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Naval Manoevres”.

Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Warships of the World to 1900.

Paine, S.C.M. (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy.

Schencking, J. Charles (2005). Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, and the Emergence of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868–1922.

Wright, Richard N.J. (2000). The Chinese Steam Navy, 1862–1945.

Google sites – The Chinese ironclads in 1894

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_ironclad_Zhenyuan

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign