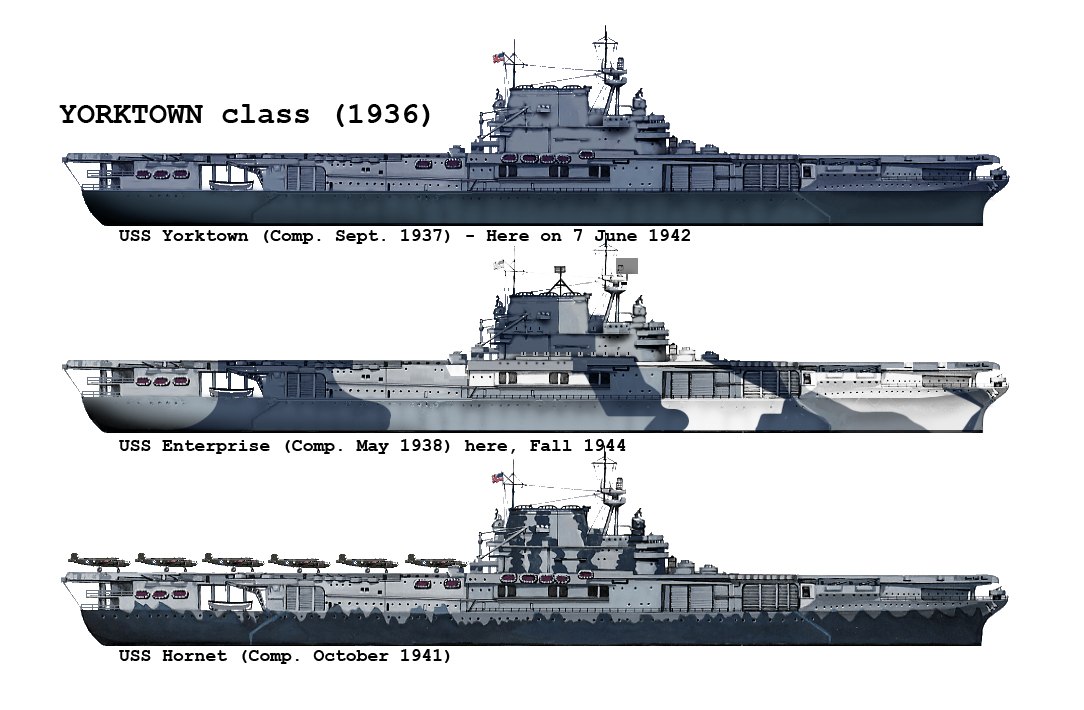

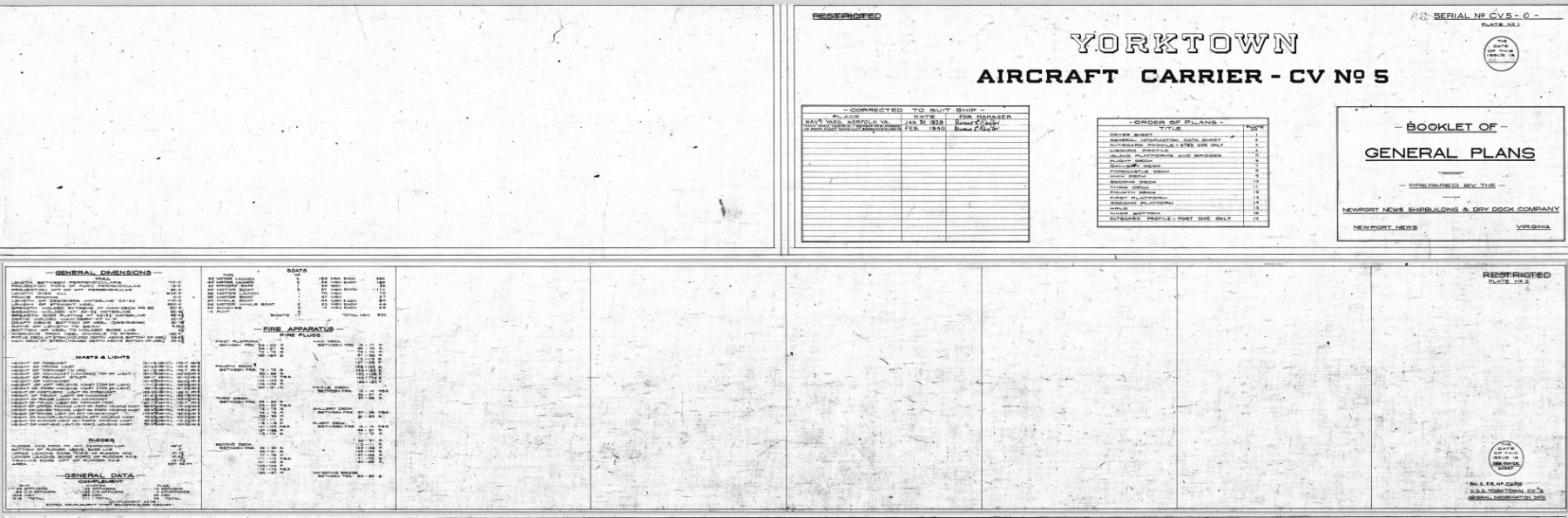

USA (1936-41): USS Yorktown, Enterprise, Hornet (CV5, 6, 8)

USA (1936-41): USS Yorktown, Enterprise, Hornet (CV5, 6, 8)WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classAt the pinnacle of US carrier development before WW2 were the two Yorktown class aircraft carriers: Yorktown and Enterprise. The Hornet is of course associated, but she was ordered much later, as was broke out in Europe. In a sense she was a wartime carrier, and the one with ironically the shortest career. Of these three vessels, only USS Enterprise -the most decorated aircraft carrier in US history- survived to tell the tale, battle hardened, with many scars to prove it. All three best testifies of the fierce nature of the early -desperate- phase of the battle of the pacific.

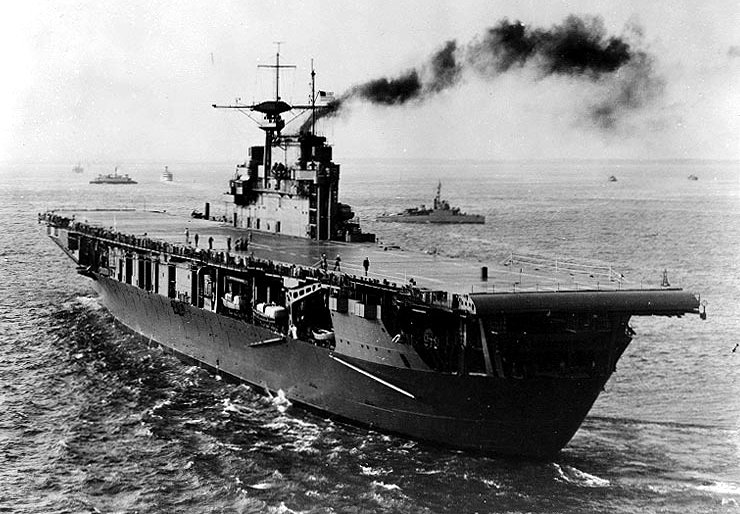

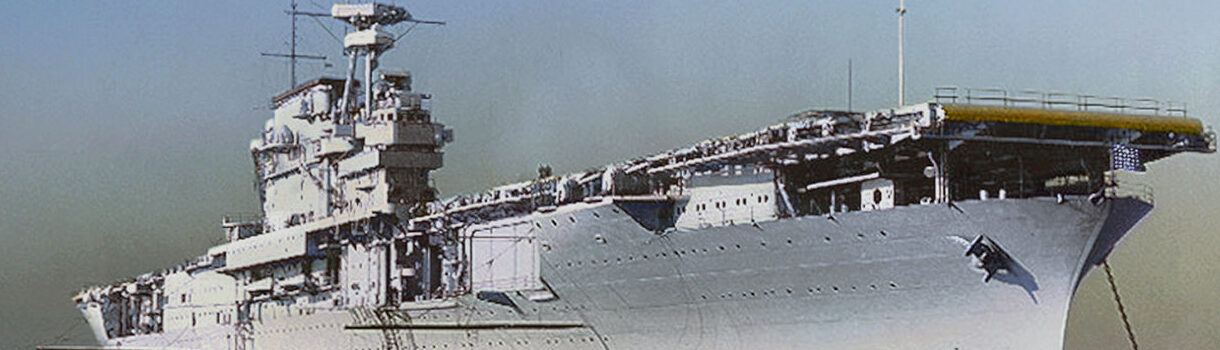

USS Enteprise underway in 1939

As designed in 1932-33, these carriers were tied by the Washington treaty tonnage limits – The reliquate tonnage was “spent” with USS Wasp, and engineers did their best to ensure they carried the largest air group possible, as shown by previous war games. They could only do this on a tonnage far superior to the previous USS Ranger, the first tailored designed carrier, and still it was nothing compared to the next Essex class, laid down in April 1941, with 35,000 tonnes fully loaded, 10,000 tonnes more than the Yorktown and more than twice the Ranger, and again twice as much for the Midway class in 1945 (59,000 tonnes fully loaded).

USS Hornet under heavy attack at the battle of Santa Cruz Island, later sunk. Only two prewar USN Carriers survived the first harrowing two years of the pacific war: USS Saratoga (CV3) and USS Enterprise (CV6).

Design development of the Yorktown class (1930-34)

The Yorktown class benefited in design from the early experience with the Ranger (completed in July 1934, three months after the keel of Yorktown was laid down), but first and foremost the earlier Lexington class, which were conversions allowed by the Washington treaty. USS Ranger in 1929 was already thought in accordance to the Washington treaty tonnage limits, both in unit tonnage and overall tonnage. Engineers at first tried to fill the lower end of the tonnage with small carriers. However during her construction standardized war gaming exercises using Langley and the Newport Naval War College showed plus reports operations from the two Lexingtons showed the importance of a large air group. It was considered more flexible. The second concern was more about engineering, but also the war games showing the real threat posed by submarines in the Pacific: ASW protection needed to be a major concern for them as well.

Tonnage considerations (1930-31)

From these two principles was extrapolated the replacement carriers of the Ranger. The admiralty did not want to wait for report operations from the use of USS Ranger. They choose a larger design in 1932 already, long before the Ranger was even launched. This choice however was a problem considering the remaining tonnage as it would force the construction of a fourth carrier on a reliquate tonnage, so smaller than the Yortkown class. This was not seen as a significant problem however as long as two class of homogeneous, large fleet carriers were available for the Pacific: The Lexington and Yorktown pairs. This was very attractive as the general board considered two carriers operating together as giving many tactical advantages. The Atlantic fleet would operate the Ranger and hypothetical CV7, which was indeed what happened in WW2.

USS Yorktown, dry dock at Pearl Harbor, 29_May 1942

Before the USS Ranger was commissioned, there were 54,400 tons of carrier tonnage usable under the Washington Treaty. After the initial 17,000-ton design (three ships, under 135,000-ton global Treaty limit), combining both a large air group and the desired high operating speed, while keeping protection required a heavier tonnage. There was no other mathematical solution. In between, the London Treaty of 1930 required USS Langley was added into this 135,000 global tonnage, even if she was previously classified as “experimental” and discounted. The end result was to push the Navy to aim for a larger, 19,000-ton carrier design fulfilling their requirements under the remaining 52.000 tons standard.

They were still smaller than the USS Lexington and under the nominal 27,000-ton limit design. The preliminary design combined an high-powered machinery, large hull volume, superior flight deck area, improved durability and all-weather ability to launch aircraft. These versatile carriers were tailored to operate 80 aircraft, so almost as many as the comparatively larger Lexington class, the advantage of creating a purpose ship and not a conversion over and existing hull made for another task. Several options were discussed between the admiralty and Bureau of Ships (BuShips) on how to use the tonnage and initially in 1929, four carriers of the Ranger size was the preferred solution, or two ships using the maximum tonnage allowed by the 1921 Treaty, and three carriers of intermediate size (like the future Wasp).

-The fourth option suggested two 20.500 tons ships plus another Ranger-size vessel. In the end it was seen as the optimal solution, offering a wide variety of experience with three scaled design to the fleet, still allowing the deployment of a carrier pair (the “small one” would be Ranger and CV7 for the Atlantic).

The design in refined (1931-32)

Consideration about the flight deck

Several factors were considered at once such as higher speed than Ranger and the objective of 32.5 knots was put early one to operate alongside the new heavy cruisers. Aviation handling facilities, notably details such as the elevator size, general deck arrangement needed to be remodeled incorporating operational lessons. Protection and AA defense needed to be enhanced.

This is in May 1931 that the initial planning for the Yorktown class took shape. The design was to reflect the variety of missions facing the American carrier force, so it was to be mirrored on the design, and two features were studied and later eliminated. But they were considered and carefully studied in the early draft:

-The choice of an armored flight deck

-A Second flying-off deck.

At the time it was draft, no other nation had a carrier with an armored deck. This solution was just studied by the British as well, but eliminated in their own design of the Ark Royal for tonnage limits reasons. There were great benefits in having one but it was just not feasible in peacetime.

For the second option, the Japanese Akagi and Kaga were commissioned with that solution. Both would loose it later, as reconstructed in the late 1930s but by that time, the Yorktown were already completed.

The main concern of aviators was the available landing space while other flew off simultaneously. This was impossible under current operations procedure on U.S. carriers.

They professed (as learnt from early war games) full deckload strikes. This left no room for landing any plane. The two-flight deck was still not ideal, as the lower deck (used exclusively to launched such as strike) was still to deal with the upper deck’s supports. It was an hinderance when launching planes. The upper deck was also to be relatively short and that was a waste of ship’s length. It was also to cause a raise in tonnage as the ship was higher, as well as a stability issues.

All in all, a compromise was found with hangar-deck catapults launching broadside. They were planned in the design, but the Yorktown class was to keep a single and long flight deck for operations. Proven aft arrestor solutions combined with deck catapults would be the only solution to combine take off and landings, and this was secured in the final draft.

Consideration about armament

Concerning armament, this was almost an afterthought. In 1931, however there still discussion betwenen the “old guard” of the Navy and advocates of naval air power about surface-fire artillery for self defense. It was considered, but fitting 8-in artillery on board would have compromise the 20,000 tonslimit, as well as 6 inches, which were considered too weak. Both solution would have also implied a sacrifice of air power. It went down to the same solution as the Ranger, using 5 inches guns which had the advantage of procuring a long range AA defense, and it was supported by a large number of smaller calibers, mainly 0.5 cal Browning M1920 heavy machine guns. It was urgent to find an intermediate caliber, but at that time, the new 28 mm AA guns in development were planned to be incorporated in the design.

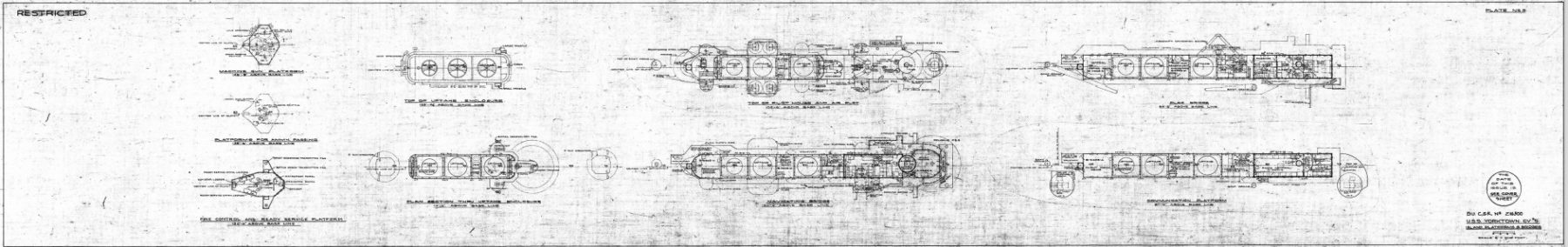

Consideration about an island for C&C

The use of an island was also discussed and the admiralty board looked at the problems encountered by British designs. the US naval attaché in Britain, J.C. Hunsacker, reported HMS Furious developed smoke interference problems due to the absence of proper smoke stacks. Options were considered such as folding stacks or speed reduction as the latter was likely to produce less smoke. Speed was critical, so aviators accepted the use of a fixed, large funnel, embedded therefore into an island.

A further argument in favor of an island was the necessity to better control deck operation, with larger air groups and AA batteries coordination. This required well placed fire control direction systems, and therefore required an island design to support these. BuAer so retracted all demands for flush decked carriers at the time the Ranger was still in final design phase already.

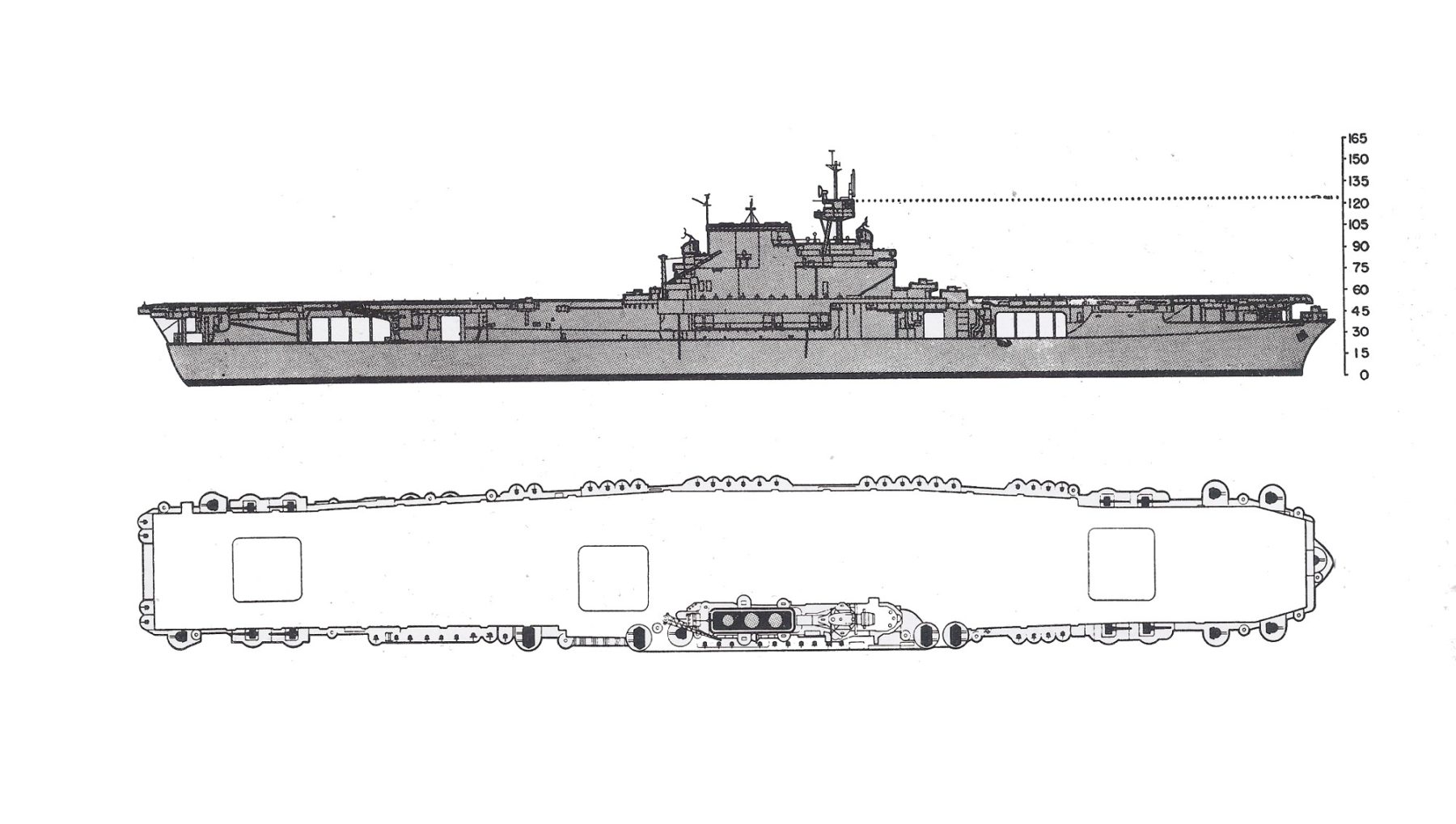

ONI – The Yorktown class in 1943

There were a number of designs studied. Design F was used as the basis to reduced tonnage further, from 20,700 tons down to 20,000 tons. This enabled the third carrier, displacing 15,200 tonnes standard as required initially. CV7 was shorter, carried slightly less planes, lacked torpedo protection, but had the same speed and protection against 6 inch gunfire.

Final design

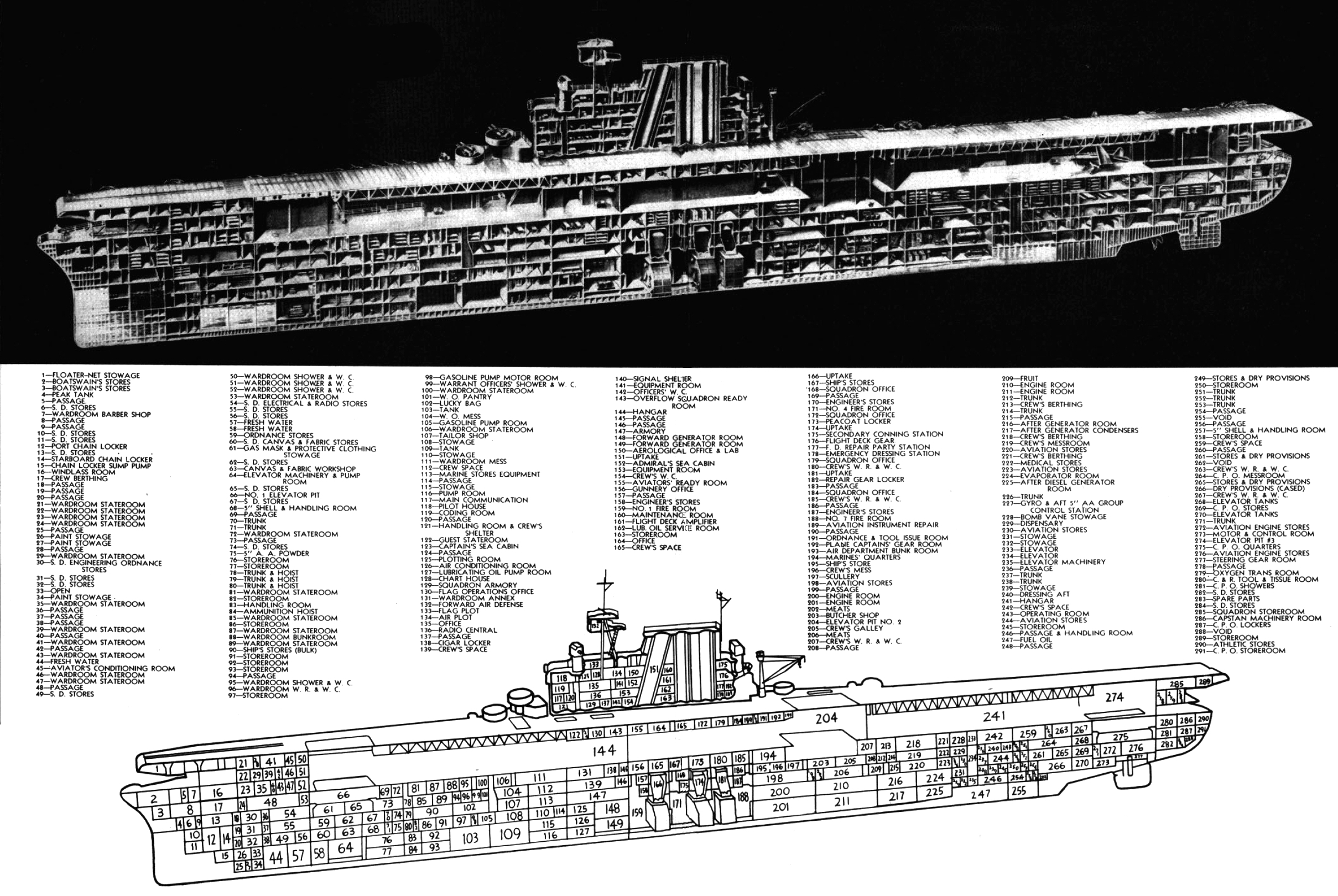

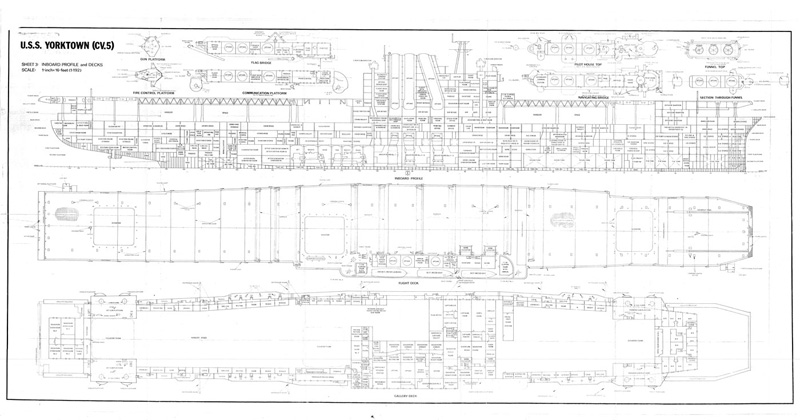

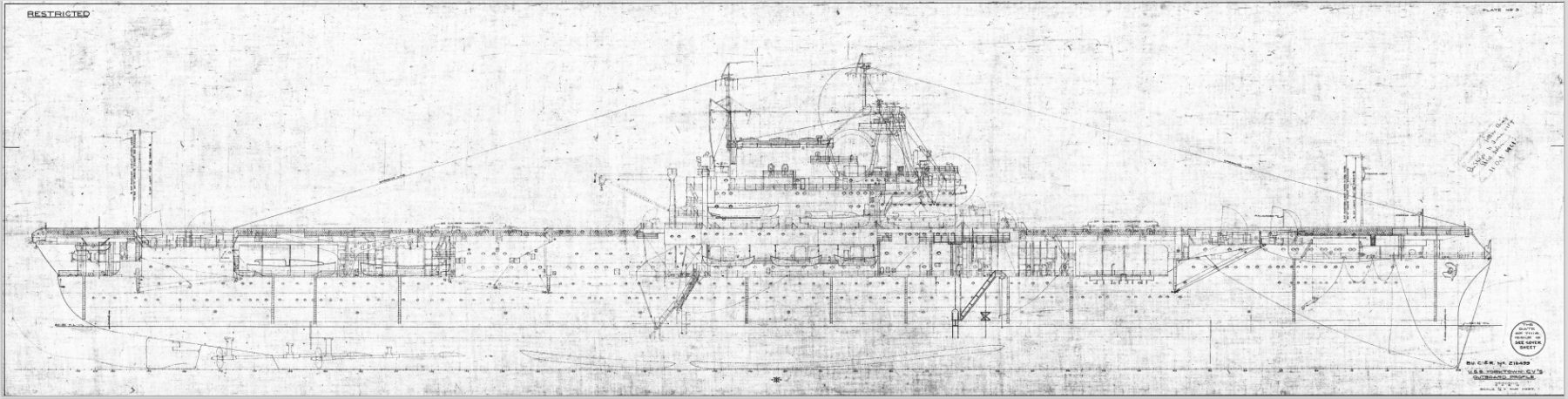

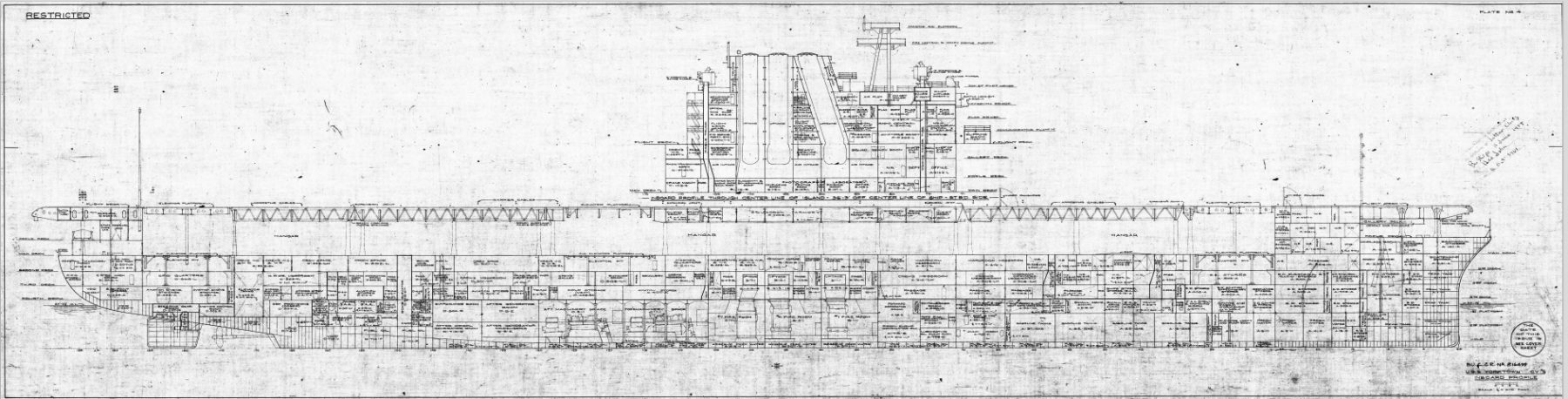

Popular Mechanic 1953 cutaway showing all the internal arrangement of the Yortkown.

The finalized design was worked out in 1932-33 and ready that year, but the laying down was severely delayed by the worsening Depression. Vote was not secured that year. Alas, this allowed engineers to return and work out more details, notably weight-waving measures. For about a year, the design was modified and refine. It was mostly in respect of aviation technology improvements. After much discussion, the flight deck was made even longer to allow the take-off of larger and heavier planes then ordered by the USN.

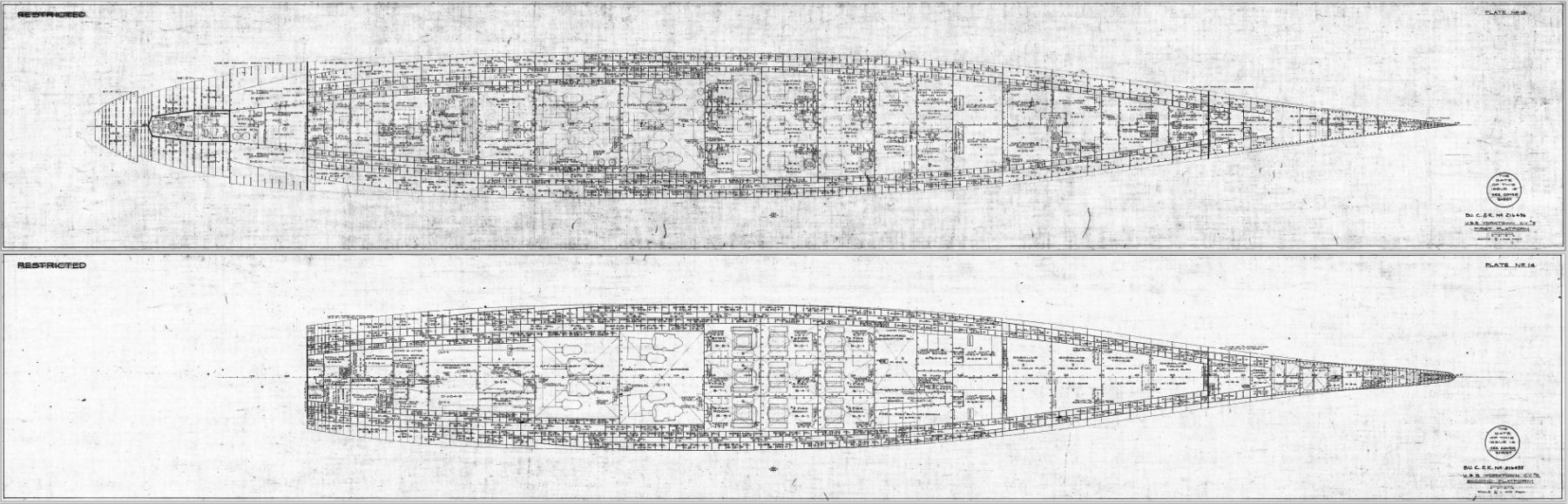

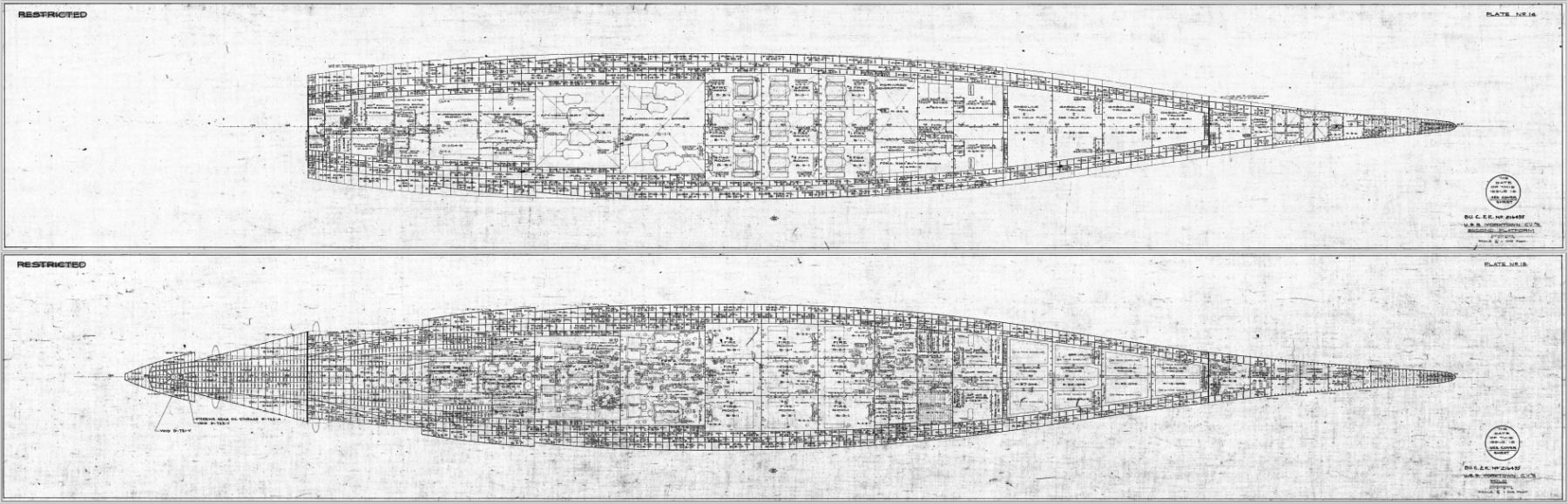

At 20.000 ton the Yorktown class became an excellent modern carrier design. Between 1931 and 1933 it was good enough to be included in Financial Year 1933 and despite a one year delay, their value was still intact. Improvements only raised their attractive, like the redesigned large island, house potent fire-control for their light artillery and better C&C for the air group while the smokestack allowed to reach the desired speed of 32.5 knots. The aviators above all praised the almost 800 feet deck, allowing to comfortably stack about 25 planes, some stored on the sides and central portion of the deck while two could be launched on two steam catapults at once forward, and others land aft. Also, the large hangar allowed to easily manage 90 planes, many more than the Lexingtons, making a consistent air group, served by three centerline elevators.

The final design as were completed after one year of multiple refinements, was accepted by the Secretary of the Navy on November 17th, 1934. But at that time, both Yorktown and Enterprise saw their keel laid down respectively in May and July the same year, so months before, based on the initial 1933 design. The secretariat of the Navy (SecNav) just sanctioned these late changes, mostly directed at the flight deck length. Both ships had been granted to Newport News, which had the two required construction forms free. This was the same yard which built previously the USS Ranger so already well experienced.

Retrospectively it seems the choice made in the Yorktown design were sound, almost prophetic. USS Ranger proved unable to withstand rough weather in the Pacific, lacked protection making her very vulnerable and although usable in peacetime, she was soon relegated as a training ship during WW2. USS Wasp on her side, lacking torpedo protection, was lost in the Pacific theater.

The arms limitation treaties were dropped in 1937, allowing the US to start building more carriers, but with a dubitative Congress, it would take two more years, and the war in Europe in 1939 to see it authorized in September. By that time, although the CV7 design was worked out, the first of this new carrier program became USS Hornet, and despite the gap of six years (1934-39) it as chosen to just made a third ship of the Yorktown class, without many design revisions but those introduced in the Wasp. The old design was that good, it was still relevant in wartime. The new ship was commissioned in 1941. But only wartime and US entering into the war unleashed all engineering limits, to design the Essex-class aircraft carriers, essentially a Yorktown class freed from all constraints.

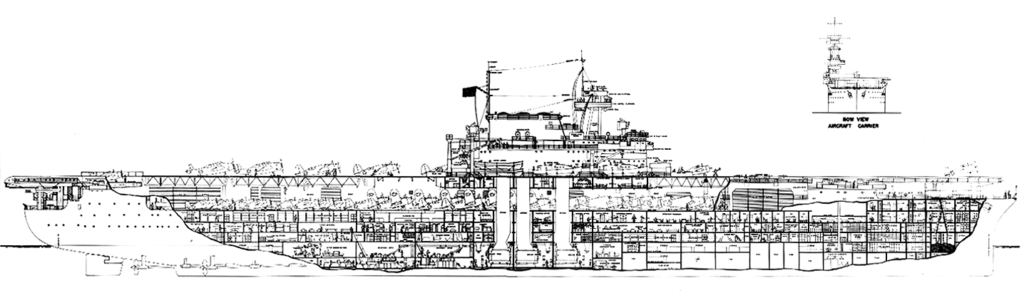

Profile Cutaway of the class (cc)

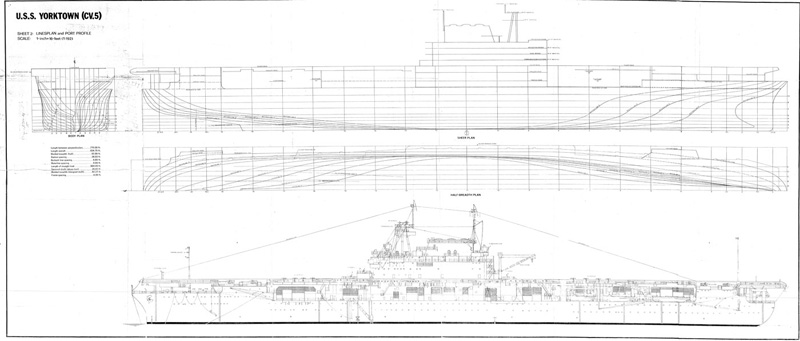

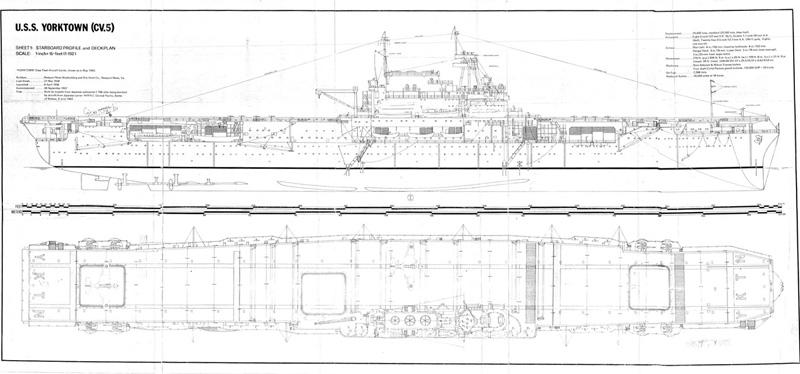

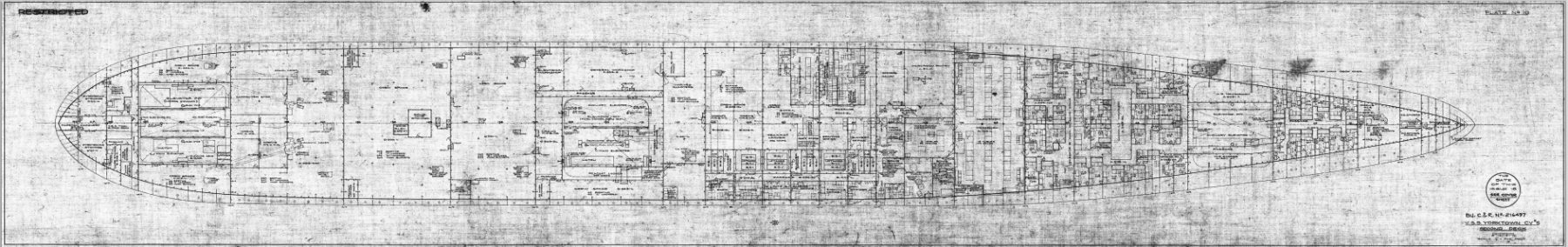

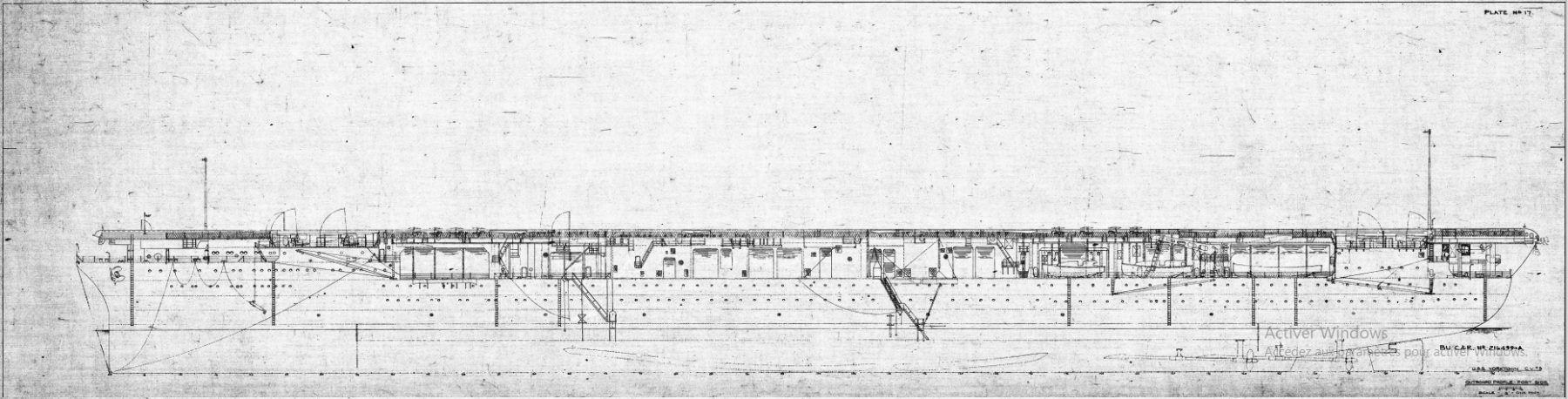

General Design

The general hull shape was derived of the Ranger, with a proper ship deck level at the same height (that of a heavy cruiser prow), flush deck, and comprising deck armor (see later). The flanks were slanted to create a larger deck surface to seat the hangar above, and making finer hull lines: At 25.34 m wide for 234.69 m long it was nearly a cruiser/destroyer ratio, 1/10, ensuring to make the best of the massive powerplant. A true armored deck was too strictly capped by tonnage limits to be considered. If adopted its thickess would have made no difference to a bomb hit anyway.

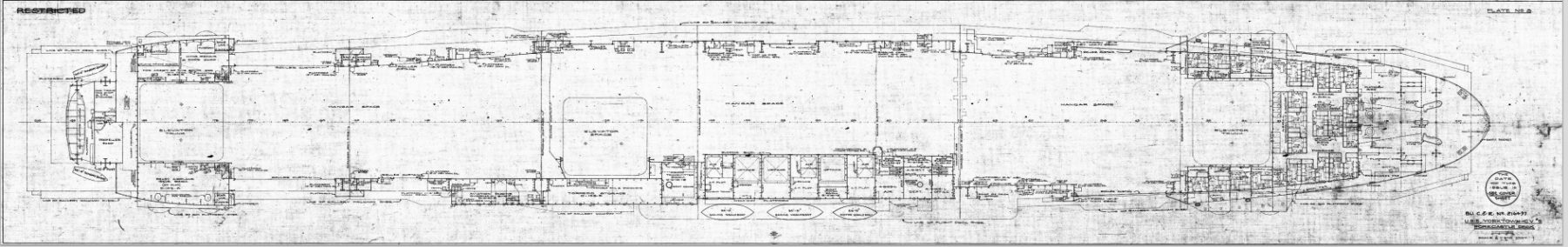

This hull deck was the basis for the single hangar. It was built directly above this deck and ran for about 80% of the usable deck surface, the remaining space was kept for crew and aviators quarters and storage. It left the poop and prow free for a few feets. The deck was not fully enclosed, although better than than Ranger, to leave less available entries to sea spray, highly corrosive to aviation. There were openings forward and aft of the island, one behind the forward lift, a smaller one at the feet at the island, and another aft, before the furthermost lift. The centra lift was placed not in the centerline but closer to the island, and aft of it.

This hull deck was the basis for the single hangar. It was built directly above this deck and ran for about 80% of the usable deck surface, the remaining space was kept for crew and aviators quarters and storage. It left the poop and prow free for a few feets. The deck was not fully enclosed, although better than than Ranger, to leave less available entries to sea spray, highly corrosive to aviation. There were openings forward and aft of the island, one behind the forward lift, a smaller one at the feet at the island, and another aft, before the furthermost lift. The centra lift was placed not in the centerline but closer to the island, and aft of it.

The Yorktown’s single hangar broadside catapult -a concession to the abandoned twin take off deck idea- were seldom used in operations. As a result it was removed in late June 1942 on Enteprise and Hornet, and subsequently eliminated from U.S. carriers design, as useless in operation.

The ammo magazine and aviation gasoline tanks were placed below the thin armor deck, with extra armour stray. There was a third deck level served by the two aft lifts to the workshop and spare parts, allowing to carry dismounted spare planes, while others could be lifted under the main hangar roof.

Powerplant

It consisted in 4-shaft Westinghouse geared turbines, installed in four separate compartments by bulkheads, two inner, axial, and two outer driving shafts offset to the axis. They were fed by the steam from nine Babcock & Wilcox boilers, all oil-firing. Their exhaust stacks were below the main funnel under three caps, the forward one being the most slanted, the other two straight. The boilers had each their own separate compartment. In total, this powerplant developed 120,000 shp (89 MW). By comparison it was less than the gargantuan but obsolescent Lexington’s powerplant, wich developed 180,000 shp (130,000 kW) for a top speed of 33.25 knots. The yorktown, with a much more compact powerplant and more planes onboard still reached 32.5 kn (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph), enough for fleet use with cruisers. Her operational range was 12,500 nmi (23,200 km) at 10 knots versus 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) for the Lexingtons. The ships indeed carried 2750 tonnes of oil in peacetime, and up to 4360 tonnes of oil in wartime, a great difference explained by the filling of all void compartments along the hull for ASW protection and double hull as well.

Protection

It was way more extensive than the USS Ranger, or the Wasp, an advantage allowed by the larger hull. Her armoured belt ranged from 2.5 to 4 in (6.4–10.2 cm) of armour, over a .75 inches STS plating. This allowed a future wartime upgrade, never made. Her main armour deck (hangar floor) was 1.5 in ( cm), and the external bulkheads, behind the belt and transverse were 4 inches thick (102 mm). Since the ships had an island, there was also a command conning tower, with walls also 4 inches thick, well capable of stopping bomb fragments and shapnel. The ASW protection rested on empty spaces (filled with seawater or oil in wartime). Oil’s own thickness allowed to absorb much of the impact detonation. It was sufficient in theory, but still USS Yorktown was sunk by a submarine. This was more however the coup de grace than a full ‘kill’ as she had been badly damaged already by IJN aviation at Midway.

Armament

Not much change from the Ranger, the three carriers entered service with the same “package”:

-Eight 5-inches/38 Mk.12 dual purpose guns, placed by pairs and individual sponsons either side of the flight deck, fore and aft. Their level allowed to cover boyh sides, a crucial advantage. Specs are the same as the standard 5-in/38 (127 mm) ubiquitous in the Navy.

-Four quadruple 1.1 inches/75 Mk.1 AA guns (28 mm), the famous “chicago piano”. They were installed after completion, still under development in 1936. They were installed in pairs at the foot of the bridge, fore and aft. Needless to say they were replaced by 40 mm Bofors quad on the Hornet and Enterprise after refit. Yorktown sunk with these. In 1944, USS Enteprise had five quad Bofors, four replacing the 1.1 in quad and one above the prow, on a raised platform, just below the flight deck.

-Twenty-four individual or twin 0.5 cal. Browning M1920A4 heavy machine guns. The trusted “ma deuce” was considered efficient for close range strafing planes and they were placed in sponsons along the main flight deck. Recognised as too weak, they were replaced during maintenance periods in 1942 by shielded 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns in single mounts. More sponsons were added on the flight deck sides, and eight more on the main bridge starboard side, front and rear reaching a total of 36 in 1944.

Air group

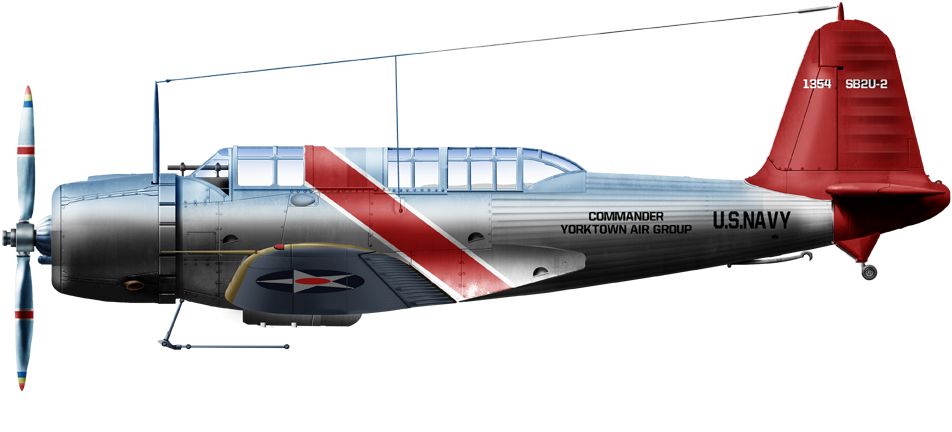

Author’s illustration of the SB2U-2 onboard Yorktown in 1939

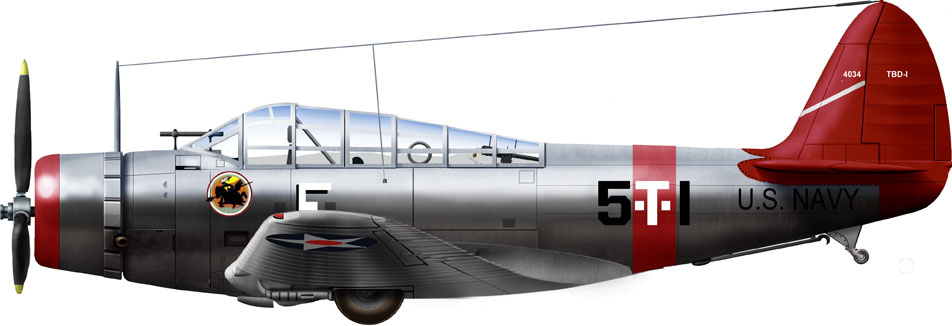

Same, TBD-1 of VT-5 onboard Yorktown in 1939

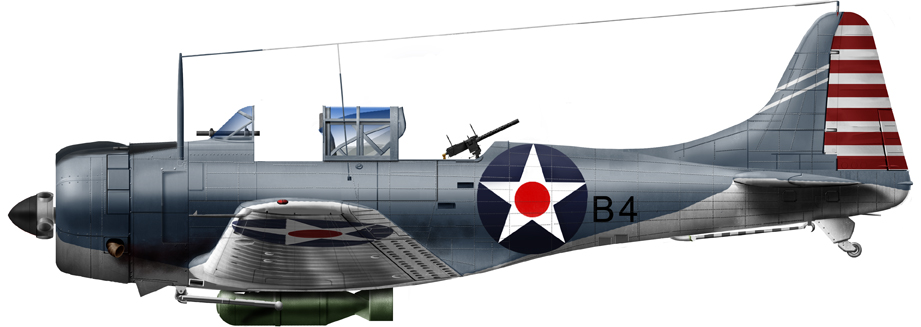

Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless from VB6, USS Enterprise, raid on Wake island, February 1942

USS Wildcat, VF-8 onboard, USS Hornet, April 1942, after the Doolittle raid.

Due to their completion in 1937-38 they entered service with a mix of biplanes and monoplanes. Were used onboard USS Yorktown the venerable Boeing F4B (1932), the Grumman F2F and F3F, both biplane fighters, as well as the Curtiss F11C, BFC, BF2C Goshawk biplane fighters/dive bombers. Also onboard were the Great Lakes BG-1 bombers, Curtiss SBU and SBC Helldiver, also biplane dive bombers. Also was onboard the Martin BM dive and torpedo bomber, Martin T4M (Great Lakes TG serie) torpedo bombers. All were biplanes, which fortunately had been gradually replaced in 1941.

In 1937 already, transition was slowly made to monoplanes, like the TBD Devastator as a torpedo bomber and reconnaissance planes such as the Vought O3U, SU, and SOC Seagull, launched by the hangar broadside catapult (float version) or in wheeltrain version. USS Enteprise never operated the F4B, operated the SB2U Vindicator since the origin, but had overall the same planes, for 96 in total too.

USS Hornet being “late” in the game directly adopted more modern monoplanes, in detail, F2A Buffalo and F4F Wildcat fighters, the Curtiss SBC Helldiver (her last biplane), the SB2U Vindicator, SBD Dauntless used as dive bombers, and the TBD Devastator torpedo bomber plus the Curtiss SOC Seagull for reconnaissance, with wheeltrain carriage (the latter remained standard until 1944). Her catapult was removed. CV8 (USS Hornet) was also the first fitted with the early SC air warning radar.

Martin T4M of VT-2B, over USS Saratoga in 1939.

In June 1942, USS Yorktown had 25 F4F Wildcat fighter on board, 37 SBD Dauntless and 13 TBD Devastator plus two O3U. These two remained standard until 1944.

In June 1944 USS Enterprise had 31 F6F Hellcat on board, three F4U Corsair, 23 SBD Dauntless and 15 TBF Avenger, plus two O3U.

Not much larger models were used on USS Enterprise after WW2 as her flight deck was too weak to operate larger planes (and jets for that matter).

USS Yorktown Specifications as completed |

|

| Displacement | 19,875 tonnes standard as designed, 25,484 fully loaded |

| Lenght waterline, overall, flight deck | 234,7/246,58/251,38 m (770/809/825 ft) |

| Width waterline, flight deck | 25.34/33,37 m (83 ft 2in/109 ft 6in) |

| Draught standard/fully loaded | 7.20/7.90 m (25 ft 11 in filly loaded) |

| Crew | 2,175 in 1942 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Westinghouse steam turbines, 9 B&W boilers, 120,000 shp |

| Speed | 32.5 knots (60 km/h; 38 mph) |

| Range | 12,000 nmi at 15 knots (2750-4360 t oil) |

| Armament | 8 × 5-in/38, 4×4 1.1 in, 24 x 0.5 in MGs |

| Aviation | 96 (maximum), 2 elevators, 2 catapults |

| Armor | Belt 2.5-4 over 0.75 in STS, Armour deck 1.5 in, Bulkheads & CT 4 in |

USS Yorktown at the Battle of the Coral Sea, April 1942

USS Hornet 1942

Yorktown class, author’s illustration of the three carriers with various liveries

Read More/Src

Links:

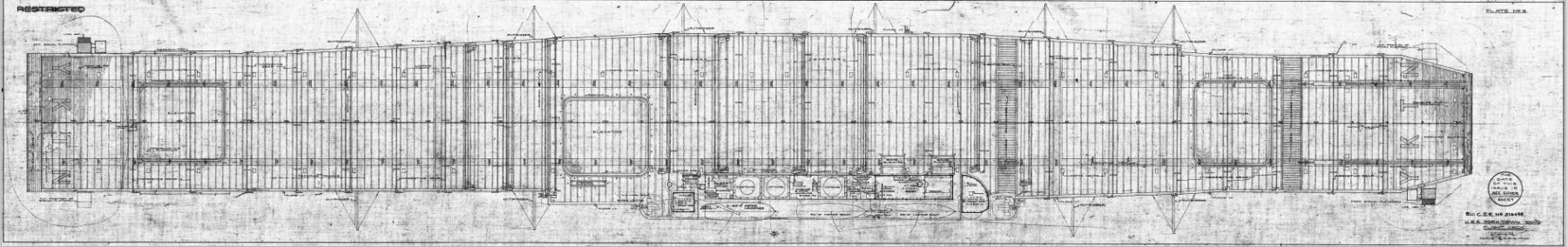

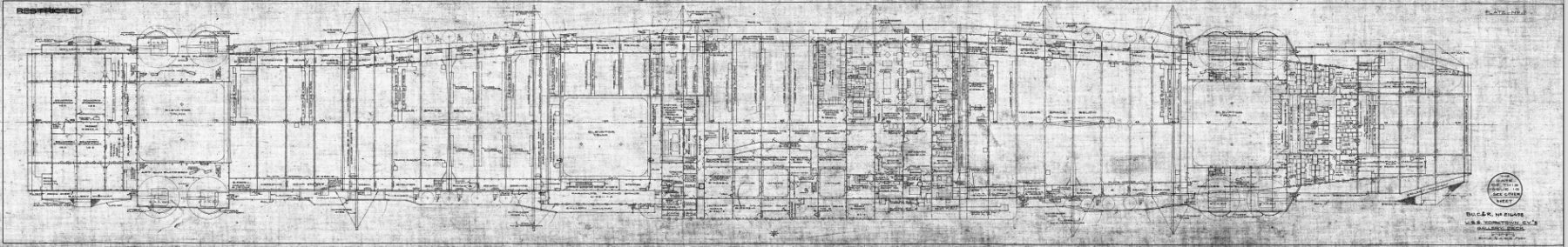

//cv5yorktown.com/about/photos-and-plans/uss-yorktown-cv-5-a-study-in-blueprints/

//fdocuments.in/document/uss-yorktown-blueprints.html

CC Images: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Yorktown_class_aircraft_carriers

//usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2015/04/12/evolution-of-the-aircraft-carrier/

USS Yorktown as completed in 1937

Books:

-J. Gardiner Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

-Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

-Friedman, Norman (1983). U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History.

-The Encyclopedia of Air Warfare” Salamander Books, Ltd.

-Sumrall, Robert F. (1990). “The Yorktown Class”. Warship 1990. Conway Maritime Press.

-Polmar, Norman; Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. Volume 1, 1909–1945. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books.

Videos

USS Hornet – US movie archive

Mil. history visualized – Yorktown class vs Shokaku class

Drachinfels’s Yorktown class

A brief about the class

The “Big E” – World of Warships.

https://youtu.be/5fzDF-Ceres

Extract of the Midway 2019 movie

Model Kits

USS Hornet CV-8 GPM 1:200

USS Hornet CV-8 Merit International 1:200

USS Enterprise CV-6 Trumpeter 1:200

Yorktown CV-5 Trumpeter 1:200

USS Yorktown CV-5 (1942) Battle of Midway, Blue Water Navy 1:350

USS Hornet CV-8 (1942) “Doolittle Raiders” Blue Water Navy 1:350

USS Enterprise CV-6 (1944) The “Big E” (Over 2 feet long) Blue Water Navy 1:350

U.S. Navy Enterprise Aircraft Carrier CV-6 I Love Kit 1:350

USS Enterprise CV-6 (1942) Merit International 1:350

USS Yorktown CV-5 (1942) Merit International 1:350

USS Hornet CV-8 (1942) Trumpeter 1:350

USS Enterprise Trumpeter 1:350

USS Enterprise CV-6 (1944) Yankee Modelworks 1:350

USS Hornet CV-8 (1942) Yankee Modelworks 1:35

Doolittle Tokyo Raid Set Revell Monogram 1:426

U.S.S. Yorktown Aircraft Carrier Ace Whitman 1:450

USS Enterprise Advent 1:487

USS Yorktown Aircraft Carrier Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Yorktown Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Hornet Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Yorktown The Fighting lady of the Coral Sea Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Enterprise The “Big E” Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Hornet CV-8 Revell 1:487

U.S.S. Enterprise Revell 1:487

CV-5 Yorktown Revell Japan 1:487

CV-6 Enterprise Revell Japan 1:487

CV-8 Hornet Revell Japan 1:487

U.S.S. Yorktown Revell/Kikoler 1:487

U S.S. Hornet Revell/Kikoler 1:487

U.S.S. YORKTOWN/HORNET/ENTERPRISE Revell/Lodela 1:487

U.S.S. Yorktown/Enterprise Lindberg 1:525

Battle of Midway Carrier (Enterprise/Yorktown/Hornet) Revell 1:542

U.S.S. Enterprise Young Model Builders Club Edition Aurora 1:600

USS Enterprise CV-6 Academy 1:700

USS Enterprise CV-6 Doyusha 1:700

USS Yorktown/Hornet/Enteprise (1942) HP-Models 1:700

U.S. Navy aircraft carrier Enterprise (2 others) Meng Model 1:700

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands CV-8 Hornet Vs Japanese Navy Air Corps Pit-Road 1:700

CV-8 Hornet w/IJN Destroyer Makigumo Pit-Road 1:700

Yorktown CV-5 Tamiya 1:700

Enterprise CV-6 Tamiya 1:700

Enterprise Waterline Series Tamiya 1:700

Hornet CV-8 Tamiya 1:700

USS Enterprise (CV-6), 1944 Tom’s Modelworks 1:700

USS Yorktown CV-5 Yorktown Class Carrier 1942 Tom’s Modelworks 1:700

USS Enterprise/Yorktown/Hornet Trumpeter 1:700

Yorktown “National Defense” Model Class Strombecker 1:768

U.S.S. Hornet/Yrktown/Enterprise Miniships Casadio 1:1200

Same Waterline Snap-Together ESCI 1:1200

Same Table Top Navy LIFE-LIKE Hobby Kits 1:1200

Same U.S.S. Profile Waterline Series MPC 1:1200

Same Table Top Navy Pyro 1:1200

Same Revell 1:1200

U.S.S. Yorktown Zvezda 1:1200

USS Yorktown CV-5 XP Forge 1:1200

USS Enterprise CV-6 (camouflage) 1945 Navis – Neptun 1:1250

USS Enterprise Aoshima 1:2000

The Yorktown class in action

USS Enterprise hit by a Kamikaze in May 1945

The losses and awards of the class is a vivid testimony of the fierce nature of the war in the Pacific: Both Yorktown and Hornet were lost relatively early into the conflict (June and October 1942, so six and ten month after the US’s entry into WW2), while USS Enterprise was herself battle damaged, at some point severely, and managed to survived until the Essex class took over. She is certainly the most revered of the three and would remain the most decorated US aircraft carrier in history so far.

USS Yorktown (1937-1942)

Prewar Operations

Atlantic & Caribbean (1937-39)

USS Yorktown was built at Newport News, Virginia, launched on 4 April 1936 and sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt, commissioned at Naval Station Norfolk Virginia on 30 September 1937. Captain Ernest D. McWhorter took command of the ship. Fitted out, she trained in Hampton Roads at the southern drill grounds, Virginia capes. This went on until January 1938, performing all required carrier qualifications for her air group. She made her first shakedown cruise in the Caribbean on 8 January 1938, stopping at Culebra, Puerto Rico. She stopped at Charlotte Amalie, St Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Gonaïves, Haiti, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Cristóbal (Panama). She departed on 1 March, Yorktown for Hampton Roads (6 March) and Norfolk Navy Yard for her post-shakedown fittings. This went on until the autumn of 1938, and she resumed training at NS Norfolk in October 1938.

USS Yorktown operated trained off the eastern seaboard, on a lined stretching from from Chesapeake Bay to Guantanamo Bay in 1939, and was promoted as flagship for Carrier Division 2, taking part in Fleet Problem XX with USS Enterprise in February 1939. It was about control the sea lanes in the Caribbean, the secnario including a foreign European power invasion, with naval strength sparing to protect also American interests in the Pacific. These were witnessed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt from the heavy cruiser USS Houston.

Post-exercise reports revealed that carrier operations reached the desired level of efficiency, even despite the lack of experience of both Yorktown and Enterprise air groups. Their significant contribution to the success was noted and largely attributed to their large air group. They worked to develop combined tactics which proved very valuable two years later.

Pacific (1939-40)

USS Yorktown sailed to Hampton Roads for supplies and crew’s rest and for the Pacific on 20 April 1939 via the Panama Canal. CV-5 started a routine of operations and when WW2 started on 1 September 1939, she operated from San Diego. She took part in Fleet Problem XXI in April 1940 and was in port to receive the new RCA CXAM radar soon after, one of the four ships receiving it at the time in the whole US Navy. Her signal bridge (tripod foremast) was full enclosed while additional 50 caliber machine guns were added in flight deck edges sponsons. Fleet Problem XXI has been a success, in which she proved air operations were a major asset. Fleet Joint Air Exercise 114A for example coordinate Army and Navy defense for the Hawaiian Islands. Her air group was used for high altitude tracking of surface forces.

Afterwards, CV-5 left the Pacific for the west coast of the United States, returning in Hawaii the following spring. At that time German U-boats rampaged the Atlantic and the US Navy was asked to send assets to the east. USS Yorktown and Battleship Division Three (the New Mexico-class battleships) plus three light cruisers, and 12 destroyers therefore left the Pacific fleet for the Atlantic fleet via the Panama canal.

Atlantic Neutrality Patrols (April-December 1941)

USS Yorktown departed Pearl Harbor on 20 April 1941 with USS Warrington, Somers, and Jouett for the Panama Canal, crossed during the night of 6–7 May. She arrived at Bermuda on 12 May. She started to conduct four patrols, from a position as far north as Newfoundland, down to to Bermuda. She covered 17,642 miles (28,392 km) that year. On 28 October, while she sailed in company of USS New Mexico, a destroyer picked up a submarine contact, dropped depth charges. The convoy made three emergency changes of course and due to Empire Pintail’s engine repairs speed was down to 11 knots (13 mph; 20 km/h). German radio signals were intercepted during the night and Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt sent a destroyer to sweep astern of the convoy. The following day, Yorktown and the cruiser USS Savannah fuelled their escorting destroyers until dusk fell and the following day, she prepared to fuel three more destroyers when sound contacts were made again. The convoy made 10 emergency turns and USS Morris and Anderson dropped depth charges on contacts, Hughes in detection. No U-Boat was apparently sunk despite oil and some debris. But the same day, on 30 October, U-552 torpedoed the USS Reuben James, a first loss which further rose the state of emergency of these “Neutrality” Patrols until November. CV-5 headed to refuel and crew’s rest at Norfolk on 2 December 1941.

Back to the Pacific (December 1941- May 1942)

Samoa, Gilberts, and New Caledonia

On 7 December 1941, the devastating loss of capital ships left the USN with just three aicraft carriers in the Pacific, USS Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga. Yorktown, Ranger, Wasp were in the Atlantic while USS Hornet, just commissioned, was also there and needed time to train. USS Yorktown was ordered off Norfolk on 16 December, heading for the panama canal zone with secondary gun galleries equipped with many of the new Oerlikon 20 mm gun while some Browning M2 .50 MGs were retained alongside a supply of M1919A4 .30 cal. Their pintle mounts indeed fitted neatly into cut swab handles and hollow pipes used for the safety lines, so dozens of sailors became impromptu AA gunners if needed. A report stated “USS Yorktown bristled with more guns than a Mexican revolution movie.” She was in San Diego on 30 December 1941, as flagship for Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s Task Force 17. She immediately escorted a convoy with a Marine reinforcements to Samoa, departing on 6 January 1942, and covering reinforcements in Pago Pago in Tutuila along the way.

Yorktown sailed with Enterprise from Samo on 25 January and both Task Force 8 (USS Enterprise), and TF 17 (Yorktown) made it for Marshall Islands and Gilberts respectively for concerted raids.

USS Yorktown had her own escort made of the USS Louisville and St. Louis, plus four destroyers. She launched 11 Douglas TBD-1 Devastators and 17 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntlesses (Curtis W. Smiley) on IJN shore installations, but their mission was hampered by severe thunderstorms. She lost seven planes in this raid. Later her air group struck Makin and the Mili Atolls. The attack on the Gilberts was interrupted by a failed attack from a single Japanese Kawanishi H6K “Mavis” flying boat drove off by AA fire. Another “Mavis”( or the same) attacked Yorktown from high altitude, but the latter manoeuvered and hold her AA fire to let her own combat air patrol (CAP) to do the interception. The Mavis was shot down by two Grumman F4F Wildcats. TF 17 second attack on Jaluit was marred and cancelled because of rainstorms and darkness and she retired from the area. Admiral Chester Nimitz was pleased by the results nonetheless.

Yorktown returned at Pearl Harbor for replenishment and was back at sea on 14 February, this time heading for the Coral Sea. On 6 March she met TF 11 (Lexington) under command of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown. Both TFs headed for Rabaul and Gasmata to check Japanese advance, cover Allied landing at Nouméa, New Caledonia. Together, they were escorted by eight heavy cruisers, including HMAS Australia and HMAS Canberra plus 14 destroyers. On 7 March the Japanese landed in Huon Gulf (Salamaua-Lae, New Guinea).

New Guinea

Admiral Brown change TF 11’s strike from Rabaul to Salamaua-Lae so in the morning of 10 March 1942, both air groups were unleashed from the Gulf of Papua. USS Enterprise started attack, 07:49 and, 21 minutes later, Yorktown followed. They went from 125 miles (200 km) across the Owen Stanley mountains ensuring surprise. Meanwhile Lexington VS-2 dive-bombed Japanese ships at Lae at 09:22. VT-2 and VB-2 did the same at Salamaua at 09:38. 103 planes of the 104 launched were back safely by noon with just a single SBD-2 Dauntless downed by Japanese AA fire. This successful and devastating attack gave a great deal of experience of still largely rookie pilots. TF 11 retired southeast for the night and met TG11.7 with the USS Chicago, HMAS Australia, and HMAS Canberra and four destroyers (Under command of Australian Admiral John Crace).

Yorktown remained in patrol in the Coral Sea area into April, with a situation temporarily stabilized. Yorktown and TF 17 stopped in Tongatabu (Tonga Islands) for some maintenance overdue since Peal Harbor on 14 February. Soon however Admiral Nimitz received “excellent indications that the Japanese intended to make a seaborne attack on Port Moresby the first week in May”. So USS Yorktown left Tongatapu on 27 April, bound for the Coral Sea. TF 11 (Rear Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch) join Fletcher’s TF 17 southwest of the New Hebrides Islands, on 1 May.

The battle of the Cora Sea (May 1942)

At 15:17 two SBD Dauntlesses from VS-5 sighted a Japanese submarine at the surface, later forced into a dive. On the morning of 3 May, TF 11 and TF 17 were abour 100 miles (161 km) apart, refueling. Before midnight, Fletcher was warned of a Japanese landing at Tulagi (Solomon) and started construction of a seaplane base. USS Yorktown was ordered northward at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) and arrived at daybreak on 4 May, launching her first strike at 07:01 with the 18 VF-42 F4F-3 Wildcats and the 12 VT-5 TBD Devastators plus the 28 VS/BY-5 SBD Dauntlesses. This was a devastating attack on enemy ships and shore installations at Tulagi and Gavutu. They claimed the destroyer IJN Kikuzuki, three minesweepers and four barges, downed five enemy seaplanes, lost two F4F Wildcats and a TBD Devastator. The same day TF 44 (Rear Admiral Crace) met Lexington’s TF 11. Northward, 11 transports escorted by destroyers and IJN Shōhō plus four heavy cruisers were heading towards Port Moresby while another task force—formed around Shōkaku and Zuikaku and two heavy cruisers, six destroyers provided distant cover.

On the morning of 6 May, Fletcher had all these forces under TF 17 command and at daybreak, 7 May, dispatched Crace toward the Louisiade archipelago, to intercept any convoy towards Port Moresby.Meawnhile he moved north in search of the enemy. Meawnhile the Japanese discovered the oil tanker Neosho and USS Sims. Mistook for a carrier she was attacked by two waves of Japanese planes. Sims was badly damaged ad sunk, while Neosho survived after seven direct hits and eight near-misses. On 11 May her survivors were picked up by Henley and she was scuttled.

Yorktown in drydock at Pearl Harbor on 29 May 1942, shortly before departing for Midway

By drawing off planes inbound for Fletcher’s carriers, both ships by sheer luck played their part. USS Yorktown and Lexington’s air groups found Shōhō and she was quickly sank, with the famous message to Fletcher “Scratch one flattop”. However during the afternoon, Shōkaku and Zuikaku deperatly search for Fletcher’s forces. They launched 27 tprpedo bombers which soon ran into the fighters from Yorktown and Lexington. Nine were short down. At twilight, three Japanese planes mistook Yorktown for their own carrier and attempted to land, quickly rebuffed by her gunfire and drove off. 20 min. later three more IJN planes did the same and took Yorktown’s landing circle one soon splashed and the other drve off, proably lost later in the dark, short of fuel.

On 8 May on the morning one of Lexington’s search plane spotted Admiral Takagi’s Zuikaku and Shōkaku. Yorktown air group took off and soon attack. They scored two bomb hits on Shōkaku. With ther deck in flames and perforated she would not send any plane while her gasoline tanks and engine repair workshop were destroyed. Lexington’s Dauntlesses also hit her. Meawnhile, USS Yorktown and Lexington were alerted by an incoming retaliatory strike, which came at 11:00.

USS Yorktown under attack, 4 June 1942. She managed to survive until 7 June 1942.

CAP’s F4F Wildcats downed 17 aircraft and the remaining ones went through the AA barrage. Nakajima B5N “Kates” launched torpedoes on Lexington’s and achieved two hits (port side) while Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers scored three deck hits. USS Lexington started to list, fires raging below decks. Meanwhile, USS Yorktown (Captain Elliott Buckmaster) was skilfully evading attacks as well. She dodged no less than eight torpedoes and evaded all “Val” dive-bombers hits, but taking one at 11:27. It in the centre of her flight deck. The semi-AP 250 kg (550 lb) bomb penetrated four decks before exploding. An aviation storage room exploded, while 66 men were lost. The superheater boilers were also out of commission. The 12 near misses also damaged her hull below the waterline.

While Lexington’s damage control parties stemmed the fires, they were unable to stop the flooding. She was later abandoned the following day at 17:07 and later sunk by USS Phelps. This was a Japanese tactical victory, but allied strategic victory as Operation Mo was abanadoned. Yorktown however paid a heavy price for it, suffering enough damage to be written off for three months repairs in dry dock. However meanwhile, US naval intel decoding Japanese naval messages estimated another large scale operation would take place at the northwestern tip of the Hawaiian chain. For the Japanese, it was “Operation Mi”, Yamaoto’s final destruction of what remained of US Naval Forces in the Pacific.

The battle of Midway (June 1942)

USS Yorktown underway at Midway in late May 1942

Admiral Nimitz planned Midway’s defense, bringing reinforcement to the island, notably bombers and naval aviation and mustering his meagre naval forces, recalling TF 16 (USS Enterprise) and USS Hornet to Pearl Harbor for replenishment. USS Yorktown also arrived at Pearl Harbor on 27 May and entered the dry dock to repair the extensive battle damage. Navy Yard inspection was revised to two weeks by employing all available workers day and night in shifts. Admiral Nimitz however knew this was still not enough, ordering to quickly patch the flight deck and repair only the most urgent and critical damage. This became the “Pearl Harbor worker’s miracle”. Knowing what was at stake, all workers present in pearl worked around the clock, falling from exhaustion, and made enough repairs to have the ship ready to depart again within… 48 hours.

So fast in fact that Japanese planners eliminated her from her calculations. Pilots would later would mistake USS Yorktown for another carrier. There was a catch however, Yorktown’s damaged superheater boilers were not repaired so her top speed was limited. Her air group was also reinforced by extra planes and pilots from USS Saratoga during her refit on the West Coast. TF 17 wason its way on 30 May to Midway, and arrived to the northeast, flying Vice Admiral Fletcher’s flag. It met TF 16 (Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance) under the hurrahs of the crews of USS Enterprise, which can’t believe their eyes. She was posted 10 miles (16 km) northward.

Soon CAPs from Midway and both carriers started in 1-3 June and at dawn on 4 June, USS Yorktown launched 10 Dauntlesses (VB-5) in reconnaissance northwards over 100 miles (160 km). Meanwhile, PBY Catalina seaplanes from Midway sighted the approaching Japanese. Soon alarm on both carriers was on. Admiral Fletcher ordered Spruance’s TF 16 to locate and strike the IJN carrier force. After Yorktown’s search group was back at 0830, the deck was prepared for the launch of her main attack group, 17 Dauntlesses (VB-3) and 12 Devastators (VT-3) plus six Wildcats (“Fighting Three”) in escort. Both USS Enterprise and Hornet launched their attack groups at the same time.

Torpedo planes first located the Japanese striking force but VT-8, VT-6 and VT-3 were decimated. Only six returned, scoring no torpedo hit (some hit in fact but did not detonated). This at least distracted the Japanese CAP, all concentrating on the Devastators. Meanwhile Dauntlesses from Yorktown and Enterprise arrived at high altitude unscaved and soon attacked. IJN Sōryū was hit first with three lethal hits. Enterprise’s planes hit Akagi and Kaga, soon destroyed by fire, caught refuelling and rearming. The remaining IJN Hiryū managed to launch a striking force (18 “Vals”) which soon located USS Yorktown.

Smoke pours from Yorktown after being hit in the boilers by Japanese dive bombers at Midway

First picked up by radar at 13:29, Yorktown’s captain interrupted the refuelling of her CAP fighters on deck and ordered them to fly asap while her returning dive bombers in landing circle wre ordered to clear off to free the AA fire. Dauntlesses also formed a CAP, now impromptu fight, low on fuel. Crews also pushed over a 800-US-gallon (3,000 l) gasoline tank on deck to prevent fire hazard and fuel lines were drained and closed, all compartment’s doors shut and hatches secured, ammunitions distributed, and light MGs added in reinforcements. All Yorktown’s crew “braced for impact”.

When position was better determined, the fighters were sent to intercept the incoming Vals, meeting them some 15-20 miles (24 to 32 km) out. Wildcats had no problem overcoming the slow Vals, breaking up their formation, but soon have to deal also with the 6 escorting “Zeroes”. Squadron leader Lieutenant Michio Kobayashi was shot down by its opposite, CO Lieutenant Commander John S. Thach. However, some Vals went through and despite the AA barrage and manoeuvrers, the carrier took three hits. In addition while the first two were splashed, the third diving Val, also shot, went out of control and tumbled, hitting abaft the number two elevator, starboard. While exploding it blew a hole 10 feet (3 m) wide, throwing deadly splinters killing crews of the two 1.1-inch gun mounts aft of the island. Three planes on the hangar deck below were also hit by shrapnel and took fire. One Dauntless fully fuelled, carrying a 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bomb was quickly mastered by LT A. C. Emerson, activating sprinkles and extinguishing the fire.

-The second hit on the port side pierced the flight deck and exploded at the base of the funnel, rupturing the uptakes of three boilers and disabling two, while shutting five while Smoke and gases filled six boiler rooms. Only the first boiler was maintained alight, allowing just enough steam pressure for the auxiliary steam systems and electricity on board (for notably the sprinklers and pumps).

-The third hit, starboard, pierced the the forward elevator, exploded on the fourth deck. Fire started in the rag storage space adjacent to the forward gasoline stowage and magazines. Carbon dioxide soon prevented gasoline from igniting.

Damage parties did an amazing job and it seems USS Yorktown was to survive this mayhem. She was steaming at 6 knots but went down to a full stop at 14:40. Now dead in the water she was an easy prey for any submarine or air attack. Due to the crippling IJN losses, the latter was now dismissed, but the first was likely. About 15:40, USS Yorktown’s boilers were slowly lit up and restarted, Chief Engineer Delaney reporting to Captain Buckmaster now her could order 20 knots. The flight deck was temporary patched, power was restored to several boilers and she ship was back to 19 knots. Captain Buckmaster, to reassure the boost the morale of his entire crew, had his largest stars and stripes flag hoisted from the foremast. Soon also, air operations were ready to start again. First the fighters on deck were refuelled, while her radar picked up another incoming air group at 33 miles (53 km). Preparation for battle resumed once more, and the six fighters of the CAP were off in interception course again, low on fuel.

Yorktown’s crew seeing the sinking USS Hammam, after themslves took two hit on the port side amidships. Before that, they have already taken two Type 91 aerial torpedo during the mid-afternoon attack by planes from the carrier Hiryu.

At 16:00, USS Yorktown was underway at 20 knots, all her fighters launched, on intercepting course and soon making contact. They started to shot down B5N Kates TBs. Wildcats shot down three, but the rest went through and prepared their low flying course, while Yorktown’s AA barrage commenced. She maneuvered hard over, dodging two torpedoes, but two more struck her port side at 16:20. The extensive damage provoked a total power loss. She was dead in the water again, but still with enough speed to turn, her rudder jammed. She started to list to port more extensively. Commander Clarence E. Aldrich (damage control officer) reported that with the pumps HS, he could not control the flooding. Chief Engineer Lt. C. John F. Delaney reported that all boiler fires were out.

Captain Buckmaster ordered both and the crews to evacuate and secure the engine rooms, move to the weather decks and put life jackets on for a possible evacuation. As the list reached 26 degrees, Buckmaster recoignised the capsizing was imminent and ordered the ship to be abandoned. lowered in life rafts or rescued by nearby destroyers and cruisers, men were picked up in good order. Executive officer Comm. Irving D. Wiltsie left the ship the last, while Buckmaster toured the ship to look for any remaining sailor before evacuating too using a two line over the stern.

He met later Fletcher onboard the cruiser Astoria (he shifted his flag to the cruiser after the first dive-bombing attack) and they agreed to sent back a salvage party to attempt to save her still. Efforts were made while her planes were now operating from USS Enterprise. They avenged Yorktown by finding and sinking IJn Hiryū later this afternoon with four direct hits.

Yorktown still floated throughout the night while the last two remaining me onboard were picked up. Buckmaster selected his damage party, 29 officers and 141 men to return on board while five destroyers formed an ASW screen around her. Work started onboard on the morning of 6 June. From Pearl, the fleet tugs USS Vireo and USS Hermes Reef arrived and took the ship on tow. All this was slow however. To restart pumps onboard, one destroyer provided power. During the afternoon, one 5-inch (127 mm) was dropped over to reduce topweight, as remaining planes and water was pumped out, reducing her list of 2°. But fate would have it the carrier was condemned anyway. Meawnhile, I-168 spotted the carrier and sneaked in, soon in favourable position with its long range torpedoes.

Unknown to Yorktown and the six nearby destroyers, however, Japanese submarine had discovered the disabled carrier and achieved a favorable firing position at around 15:36. Suddenly lookouts spotted four torpedo trails in direction of CV-5 on her starboard beam. USS Hammann, the closest, went to general quarters, firing with a 20 mm oerlikon on the trails to try to explode them. But one torpedo hit USS Hammann amidships, breaking her keel and she started to sink rapidly. Two more went fuhrter and struck Yorktown below the bilge at after end of the island. The fourth passed astern of her. Hammann soon exploded underwater while going down, probably because of depth charges going off. The concussion many of the men in the water around and the blast was powerful enough to battered the carrier’s hull. An auxiliary generator and fixtures fell in the the hangar deck, rivets popped up.

While remaining destroyers were on the hunt, Hammann survivors were pickuped up and Yorktown’s salvage party as well. The tug USS Vireo cut its tow and turned to the rescue. But amazingly, USS Yorktown refued to sink. She sailed afloat throughout the 6-7 June night. By 05:30 on 7 June however probably due to water pressure rupturing her intenal bulkheads, her list to port increased even more, and she soon turned over. She stayed here before sinking, maintained by trapped air pocked saluted by all crews and two passing by patrolling PBYs which dipped their wings. At 07:01, she rolled upside-down and sank stern first. She went down to 5,500 m, her battle flags flying. In total, the carrier lost 141 officers and crewmen. The wreck was located on 19 May 1998 and explored by Dr. Robert Ballard, “in excellent condition”. A plaque was deposed. The site is now a war grave protected by inyternational conventions.

USS Enterprise (1938-1958)

Prewar service

Launched on 3 October 1936, Newport News as her sister ship, she was sponsored by Lulie Swanson (Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson’s wife), commissioned on 12 May 1938. Captain Newton H. White, Jr. was her first captain. USS Enterprise made her shakedown cruise down to Rio de Janeiro. Captain Charles A. Pownall too command afterwards in December and she trained on the East Coast and and Caribbean until April 1939, before being ordered to move to the pacific. She apparently did not took part in the Atlantic neutrality patrols.

She received at San Diego her RCA CXAM-1 radar, one of the few ships ever given one in the US Navy. Captain George D. Murray took command in March 1941. When in San Diego she “starred” in “Dive Bomber” a movie with Errol Flynn and Fred MacMurray. She departed for Pearl Harbor after President Roosevelt ordered the Fleet to be “forward based”, under a rapidly degrading situation there. CV-6 trained intensively with her air group, and ferried aircraft to isolated island bases. With Task Force 8 (TF 8) she departed Pearl Harbor on 28 November 1941 for her fist run, carrying Marine Fighter Squadron 211 (VMF-211) to Wake Island. It was situated 2,500 miles (4,000 km) westward. Fate would have it that she was to be back in Pearl on on 6 December 1941, but was delayed by heavy weather, forced to make a turn to avoid the thick of it, and general, high waves reduces speed. On 7 December, she was still 215 nautical miles (398 km) west of Oahu.

Early Operations January-April 1942

USS Enterprise, unware of the attack, proceeded with planned routine. The chief operations ordered to launch 18 SBDs, 13 from Scouting Squadron Six (VS-6) and four from Bombing Squadron Six (VB-6) at dawn that day to scout northeast to southeast of her, land at Ford Island after completing this pattern. These arrived in pairs over Pearl Harbor, only to be caught caught between attacking Zeros and AA free fire from the ground. Seven SBDs were shot down, with 8 pilots and crew killed that day. Soon, USS Enterprise was warned by radio and directed to launch an airstrike, but based on an inaccurate report to the southwest. At 17:00, six VF-6 Grumman F4F Wildcat and VT-6 18 Douglas TBD Devastator plus and six VB-6 SBDs took off. Of course, they met no ship there and returned at dawn, while the six fighters headed for Hickam Field, Oahu. Despite warning of their approach, AA gun crews still “trigger happy” fire on them and shot two, killing their pilots, and two others were lostk one damaged, one crashed due to the lack of fuel, both pilots bailing out.

USS Enteprise off Puget Sound in September 1945, just repaired and painted in a dark blue livery.

USS Enterprise eventually entered Pearl Harbor on the evening of 8 December. Vice-Admiral William Halsey Jr. (Carrier Division 2) ordered all available hands of the crew to to help rearm and refuel the carrier as fast as possible. Instead of 24 hours ths was done in seven hours and with TF 8 she sailed in pursuit of the Japanese fleet and to prepared to an hypothetic third wave or other attacks. Her aviation indeed would later spot and destroye the Japanese submarine I-70 on 10 December. For the last two weeks of December she steamed west of Hawaii, cover the islands chain whie the other carrier groups tried to relieve Wake Island. After a short stop at Pearl Harbor, USS Enterprise was back on escort duty on 11 January 1942, to Samoa.

On 16 January 1942, one of her VT-6 SBD Dauntless, piloted by Chief Aviation Machinist’s Mate, and Pilot Harold F. Dixon, were rported lost on patrol, short of fuel, ditching, but they survived for 34 days in their small rubber raft, eventually recued by the natives of the atoll of Pukapuka, whih later notified Allied authorities. They were later pickuped up by USS Swan, and later on CV-6, awarded for their endurance. On 1 February 1942 Task Force 8 raided Kwajalein, Wotje, and Maloelap: This was the started of the Marshall Islands campaign. CV-6 air group sank three Japanese ships and damaging eight, plus ravaged airplanes and facilities on IJN bases. She returned afterwards to Pearl Harbor.

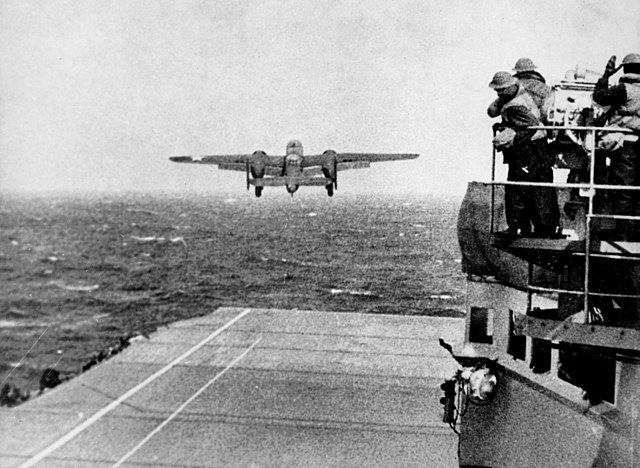

In March 1942, USS Enterprise (reassigned to Task Force 16) attacked Wake and Marcus Islands. In April, she took part in the Doolittle Raid:

After minor alterations and repairs at Pearl Harbor, TF 16 departed on 8 April 1942, meeting USS Hornet and sailing west, to take position to launch 16 modified Army B-25 Mitchells on Tokyo. USS Enteprise assured a fighters cover, combat air patrol. The launch was done prematurely on 18 April because the fleet was spotted. They flew 600 miles (1,000 km) on target and later ditched at sea on in China. They were back to Pearl Harbor on 25 April.

USS Enteprise at Midway

On the 30th, USS Enterprise was at sea again, heading for the South Pacific, rushing for the Coral Sea. However, the Battle, a tactical defeat and strategic victory, was over before she arrived. With USS Hornet, she then mocked attacked the Nauru and Banaba islands to draw Japanese forces away and delay Operation RY. She was back in Pearl Harbor on 26 May 1942, preparing for the next expected Japanese attack as shown by US intel, at Midway.

On 28 May, she departed Pearl Harbor as flagship, hoisting the colors of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. The order of the day was “to hold Midway, inflict maximum damage on the enemy by strong attrition tactics”. USS Enterprise and Hornet, plus six cruisers, ten destroyers and four oilers made TF 16. On 30 May they rendezvous with Task Force 17 (Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher), flagship USS Yorktown, which also left Pearl later with two cruisers and six destroyers. Yorktown as we saw above was badly damaged but was patched in record time. Rear Admiral Fletcher became Officer in Tactical Command while Halsey was medically ordered to remain in a naval hospital at Pearl Harbor.

The battle of Midway has been well covered in this article. For USS Enteprise, it was a shining point in her career. Like USS Yorktown, she lost most of her torpedo planes on 7 June, but her dive bombers inflicted arguably the most casualties in this action, decisively sinking IJN Kaga and Akagi, while Yorktown’s air group sank the lighter Sōryū. Hiryu, separated, launched air strikes which crippled Yorktown, while Enterprise and Yorktown’s air group disabled Hiryu and a day after sank the IJN cruiser Mikuma. This was still a pyyrhic victory with a destroyer and carrier lost, while TF 16 and TF 17 lost 113 planes in total, including only 61 in combat. USS Enterprise returned to Pearl Harbor unscaved on 13 June 1942.

USS Enterprise and Washington across the panama canal in October 1945

Guadalcanal & south pacific (August 1942- August 1943)

Captain Arthur C. Davis took command of CV-6 on 30 June 1942. The crew rested while the ship underwent an overhaul in Peark Harbor. On 15 July 1942 she was ready and prepare for the next campaign, heading for the South Pacific. She met there TF 61, supporting amphibious landings in the Solomon Islands, stating on 8 August.

For two weeks, they safguarded communication lines southwest of the Solomons and on the 24th at last a strong IJN force was spotted 200 miles (300 km) north of Guadalcanal. TF 61 sent its air groups in which became the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, fist match of the epic “Verdun of the Pacific”, the grinding contest that would eat most remaining USN Forces there, as well as Japanese. The light carrier Ryūjō was sunk during the battle, Japanese reinforcements to Guadalcanal were forced back. USS Enterprise however was attacked in return and suffered three direct bomb hit, four near misses. Her crew had 74 killed 74, 95 wounded and she was no longer operational. However her damage control parties made the impossible, patching her up just enough that she was able to steam back to Pearl.

Her Repairs lasted from 10 September to 16 October 1942. She also had depleted air group and embarked Air Group 10, which started training immediately. This air group, VF-10 “Grim Reapers” (CO James H. Flatley) became one of the most decorated in USN history. Back for the South Pacific, she met USS Hornet there to form formed TF 61, under command of Captain Osborne Hardison. There, she sent scout planes which located a Japanese carrier force. It became the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. USS Enterprise’s air group managed to struck IJN carriers and cruisers but she was hit back hard again, taking two bombs, loosing 44 with 75 wounded. This was serious damage but again, she was brillantly patched up and remained continously in action, taking on board planes from the crippled USS Hornet which later sunk. Again, that was a pyrrhic victory, TF 61 claiming one light cruiser only (and many planes), but gaining time to reinforce Guadalcanal and secure Henderson Field from furher Japanese bombardments. At that particular time, due to other losses, USS Enterprise was now the only U.S. carrier operational in the Pacific Theater (and she was badly damaged !)…

A F6F Hellcat crash lands on the flight deck on 10 November 1942 (Battle of the Eastern Solomons).

USS Enterprise limped back to Noumea, New Caledonia on 30 October, to receive repairs in a floating drydock and the fleet workshop USS Vestal. But soon the Japanese were back in force in the Solomons. She sailed on 11 November, with Vestal’s repair crews and tooling still working on board. She also carried 75 Seabees from Company B, 3rd Construction Battalion, for additional workforce. Seabees managed to even repair the ship during battle. it was done round-the-clock under supervision of CV-6’s damage control officer Lt. Cmdr. Herschel Albert Smith.

Captain Osborne Bennett (“Ozzie B”, or “Oby”) Hardison praised the Navy Department of the brillance and dedicaton of these teams to perform these emergency repairs. This later also won the praise of Vice Admiral William Halsey, which asked the OIC of the Seabee detachment for commendations and awards. On 13 November USS Enterprise’s air group sank IJN Hiei (with other CVs), duly celebrated as the first Japanes capital ship lost during this war. When the Battle of Guadalcanal ended on 15 November 1942, USS Enterprise shared sixteen ships, eight damaged. Unscaved, repairs still ongoing, she returned to Noumea on 16 November to complete these in better conditions, refill, and rest the crews.

Thisw as short, aas she was back on 4 December 1942, heading for Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. She stayed there and prepared until 28 January 1943, then departed for the Solomons, launching her air group on 30 January, and estabmishing a CAP. She took part in the Battle of Rennell Island. She drove off a wave of IJN torpedo bombers, which sank her escort, the heavy cruiser USS Chicago. Back at Espiritu Santo on 1 February 1943, she had this as a permanent base for three months, covering U.S. surface forces in Solomons for a much closer place. Captain Samuel Ginder took command on 16 April as she headed for Pearl Harbor. Se arrived on 27 May 1943 while Admiral Chester Nimitz boarded her wit his staff for a grand ceremony of individual and collective awards. The USSS Enterprise received her first Presidential Unit citation, the first also awarded to an aircraft carrier in US history.

When she would have been back in action in the summer of 1943, she was no longer alone: Both the new Essex-class and Independence-class carriers were now entering the fray and the wheel was now turning slowly in favor of the USN. The grinding match of the Solomons was mostly over, and USS Enteprise was relieved of duty and sent on 20 July to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for her first jor overhaul since the start of the war, long overdue. This took several months, and she received an extensive refit. Her AA battery was completely modernized, with only 40 mm and 20 mm AA guns, new fire controls directors, new radar, new aerials, new anti-torpedo blister and othr equipments, as well as a new air group, now only comprising Hellcats, Avengers and Helldivers. The large “6” for she was recoignisable was painted in white on both ends of her flight decks.

USS Enterprise’s island hopping campaign

With a partly fresh crews framed by grizzly vets, Captain Matthias Gardner took command on 7 November 1943, heading his ship to Pearl Harbor, arriving on 6 November and leaving on the 10th, to cover the 27th Infantry Division landing on Makin Atoll, as part of TF 50 at the Battle of Makin (19–21 November 1943). She activated night fighters, a first in the Pacific. A single night three-plane patrol broke up a large land-based IJA bombers formation poised to attacking TG 50.2. One was lost, Hellcat piloted by LCDR Edward “Butch” O’Hare. Next, TF 50 took part in the battle of Kwajalein on 4 December.

After a short supply run to Pearl Harbor, USS Enteprise joined the Fast Carrier Task Force in operation in the Marshall Islands and Kwajalein until 3 February 1944. Se joined TF 58, for a first massive strike on Truk Lagoon (Caroline) on 17 February, one of many. To this occasion she made another world’s first, launched the first night radar bombing attack ever. Twelve Avenger torpedo bombers sank about one-third of the 200,000 tons sunk that night and day.

Enterprise on the right with the Fifth Fleet at Majuro, 1944.

Sh detached to attack Jaluit Atoll on 20 February, and returned to Majuro and Espiritu Santo. On 15 March she joined TG 36.1 to cover the landings on Emirau Island on 19–25 March 1944, and next joined TF 58 on 26 March, her air group striking Yap, Ulithi, Woleai, and Palau. After a supply run to Majuro, she was 14 April covering Hollandia landings (New Guinea) before another raid on Truk (29–30 April). On 6 June 1944, with TG 58.3, she raided Majuro and the Marianas Islands, Saipan, Rota, and Guam until 14 June and Saipan on 15 June. Admiral Spruance however positioned TF 58 to meet a Japanese massive attack.

USS Enterprise’s Philippines campaign (July-November 1944)

Battle of the Philippine Sea

First, USS Enteprise participated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea: On 19 June 1944, she was with Task Group 58.3 (Rear Admiral John W. Reeves) for the “great Marianas turkey shoot”. Six USN ships damaged and 130 planes (76 pilots) for extensive Japanese losses, the carriers IJN Hiyō, Shōkaku, and Taihō and 426 aircraft. Gone was the Kido butai, the last most experienced IJN pilots, and the IJN was from now no longer able to mount a large scale attack, at least before the second match in October.

Enterprise covered the fleet with CAPs, made night strikes, a and a difficult recovery at dawn. She covered the invasion of Saipan until 5 July and went back to Pearl Harbor, refuelling while the crew enjoyed a month of rest. During the ship overhaul she received a camouflage, Measure 33/4Ab. Commander Thomas Hamilton took command on 10 Julyand then Cato Glover on 29 July. She was back at sea on 24 August with TF 38 striking Volcano and Bonin Islands until 2 September, then Yap, Ulithi, and the Palau irlands until 8 September.

Battle of Leyte gulf

After the Palau Islands she was sent northwards on 7 October and until 20 October her air group striked Okinawa, Formosa and the Philippines, preparing the landing on Leyte. CV-6 made a supply run to Ulithi and was back in action on 23 October, taking part in the epic battle until 26 October, during which her air groups operated sorties against all three IJN forces. They damaged notably battleships and sank destroyers. She stayed on patrol east of Samar and Leyte and made another run to Ulithi. In November 1944 her air group operated in support of advancing US troops towards Manila, and Yap island. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 6 December 1944, Captain Grover B. H. Hall taking command on 14 December.

From USS Washington, a kamikaze strikes USS Enteprise’s forward elevator, the explosion going back six decks below.

Luzon, China sea, Iwo Jima & Okinawa

USS Enteprise was back on 24 December in the Philippines with an air group that was trained specifically for night carrier operations. Her hull code was changed to CV(N) to mark this. She joined TG 38.5 and operated north of Luzon, and in the South China Sea in January 1945, striking Formosa, Indo-China and Macau. After another supply run to Ulithi, she joined TG 58.5 on 10 February 1945, covering the first direct navy strike on Tokyo on 16–17 February. She covered Marines during the Battle of Iwo Jima until 9 March, and made two supply runs at Ulithi, before night raids against Kyūshū, Honshū. She also targeted shipping in the Inland Sea. During at attack on 18 March by IJN bombers she was damaged enough to be repaired six days in Ulithi. Back on 5 April she assisted operations during the battle of Okinawa. On 11 April she was badly hit by a kamikaze and repaired again in Ulithi. She returned and stayed off okinawa until 6 May, fending off other kamikaze attacks. On 14 May 1945 she was hit by a kamikaze Zero laden wit bombs and piloted by Lt. J.G. Shunsuke Tomiyasu. The fighter entered her elevator, made it six decks below before epxploding, creating a massive ball of fire, propelling the elevator 400 feet in the air, killing 13 and wounding 68. For this damage scale, she was forced back in home waters, entering Puget Sound Navy Yard for long repairs. When she was back again at sea, she was underway in the Strait of Juan de Fuca when news of the war ended arrived on 9 August 1945.

USS Enterprise post war service (1945-47)

Enterprise awaiting disposal at the New York Naval Shipyard, 22 June 1958. She would not be saved from the scrapyard’s blowtorchs unfortunately, the only CV that really deserved it.

Her last major operation was Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American Marines and GIs from the pacific. She made a first run to Pearl with 1,141 servicemen due for discharge, including former POWs, and headed for New York, arriving on 17 October 1945. She sailed to Boston for the installation berthing facilities and made four runs to Europe, repatriating 10,000 veterans, ending in New York on 17 January 1946.

Afterwards her fate was pretty much sealed. The new carries of the Midway class, twice as large, showed how technology progressed during the war, and her 1930 design was not fit for the upcoming generation of jet fighters. She just twoo small and cramped for modernization. She was declared surplus and entered the New York Naval Shipyard on 18 January 1946 for deactivation. She was decommissioned on 17 February 1947. Plans to make her a permanent memorial was abandoned in 1949 as well as further Fund-raising campaigns. The war was over, peaple had other priorities.

In the end after a long mothball period, she was sold on 1 July 1958 to Lipsett Corporation, NY, for scrapping. A few items had survived though scattered throughout the USA. If a single aircraft carrier was to be preserved in USN history, this was USS Enteprise. During her harrowing tour of duty in the Pacific, she had earned a Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Unit Commendation, American Defense Service Medal with “Fleet” clasp, the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with twenty stars, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation and Philippine Liberation Medal, not counting all the individual awards to crewmen.

USS Hornet (October 1941-October 1942)

USS Hornet, aft view, after completion in October 1941

The only wartime carrier of the class was not comprehensively modernized, she was rushed out with the same design, launched in 1940 and completed in October 1941. As completed USS Hornet had three aircraft elevators 48 by 44 feet (15 by 13 m) loading 17,000 pounds (7,700 kg) and a more modern Mark IV Mod 3A arresting gear (16,000 pounds (7,300 kg)/85 mph (137 km/h) arrestng capacity. Her modern Air Group comprised 18 fighters (Wildcat), 18 bombers (Dauntless) 37 scout planes (O3U and Dauntless), 18 torpedo bombers (Devastator) and 6 utility planes. Captain Marc A. Mitscher in command during her training off the Atlantic, still ongoing when the Pearl harbor attack took place.

Doolittle raid

It was not long before she was requisitioned for a first mission, a perilous and famous one, on 2 February 1942. She embarked in Norfolk two Army Air Force B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, launched after many modifications to the disbelief of her crew. She was back to Norfolk and on 4 March sailed for the West Coast via Panama, at Naval Air Station Alameda, California, on 20 March 1942. There, her air group was stacked tight in the hangar to free her flight deck, which would be soon stacked with no less than 16 B-25 Bombers, filling 2/3 of ther flight deck down to the bow, the tail of the last planes overhanding in the air. The famous raid to strike Tokyo, was headed by legendary pilot Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle, a pioneer, acrobat, veteran of WW2 and strong advocate of air power, in the footsteps of Bill Mitchell. She met USS Enterprise at Midway (Task Force 16) and headed for Japan. The bombers were launched prematurely due to the presence of a Japanese radar picket, many later ditching at sea short of fuel. The bombing was a success, but doing little to hamper Japanese war effort. It was, in the very difficult time of the war, a considerable morale booster.

USS Hornet at Midway

Back to Pearl Harbor on 30 April she was sent to reinforced the Yorktown and Lexington at the Battle of the Coral Sea, but like USS Enteprise, she was too late to take action. On 4 May, TF16 made a feint towards Nauru and Banaba islands, so the Japanese renounced to seize these islands. Back in Pearl on 26 May she was sent back to help Enteprise in the expected Japanese assault on Midway. She sailed on 28 May 1942 for Point “Luck”, 325 miles (523 km) northeast of Midway, basically an ambushing position for the upcoming IJN force, including the dreaded kido Butai. That was the first and last time the “three musketeers” of the USN, USS Hornet, Yorktown, and Enterprise, were fighting together in a naval air battle. Their air groups, still counting rookies and with ner-obsolete planes and faulty torpedoes were nearly decimated. Hornet’s participation was 15 Devastators of Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8). Losses were tremendous, due to IJN fighters. In fact, Hornet lost the most in this onslaught as Ensign George H. Gay was the only survivor of 30 pilots and crewen.

USS Hornet’s VS-8 Dauntlesses over IJN Mikuma

The dive bombers, helped by the diversion, hamerred to death all three carriers. Unfortunately USS Hornet had no part in this final assault as her dive bombers followed an incorrect heading and found nothing. At their return, short on fuel, many ditched at sea, not having the time to wait in circles while other landed. Her CAP’s fighers however repelled, with her escort, a massive Japanese air attack later. A day after, on 6 june, her air group was hot on the fleeing IJN forces. They assisted in sinking IJN Mikuma, damaging a destroyer and IJN Mogami.

The Solomons Campaign

USS was back to Pear for repairs, refuel, resting the crew and training a partially new air group, before departing on 17 August 1942. Her task was to guard sea approaches to Guadalcanal, the most important strongpoint in the Solomon Islands. Since USS Enterprise was badly damaged on 24 August, followed by Saratoga on 31 August and Wasp sank on 15 September, USS Hornet was, for a time, the only USN operational carrier in the South Pacific. Her air group covered operations over the Solomon Islands until 24 October 1942. At last, USS Enterprise returned to assist. they sailed to te New Hebrides Islands and then steamed to intercept a massive force closing in on Guadalcanal, which turned into the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

This Battle started on 26 October 1942. USS Enterprise’s air group sank the carrier Zuihō and those from Hornet badly damaged Shōkaku and Chikuma, damaing two other cruisers. In the meantime, the launched Japanese air waves stroke both carriers. USS Hornet took the brunt of a well coordinated dive bomber and torpedo plane attack for which there was no escape. That was the culmination of the kido Butai’s veteran pilots fine training. For a harrowing 15-minutes, USS Hornet took three bomb hits (from Aichi D3A “Val”, inclding one which crashed into her island after AA damage. She killed 7 while burning aviation gas spread over the deck was now pouring into the hangar. Nakajima B5N “Kate” on their side scored two hits. All her electrical systems and engines shut down. Dead in the water, she was no ina perilous position. Soon, another damaged “Val” crashed into her port side, near the bow.

USS Hornet, crippled, is taken in tow by USS Northampton

Unable to launch or land aircraft, the captain redirected the returning planes to USS Enterprise or ditch at sea. Rear Admiral George D. Murray ordered USS Northampton to try to tow the crippled Hornet out of harm, now safer since the Japanese concentrated on Enterprise. The towing took place ad USS Hornet managed to be stracted at 5 knots. Repair crews almost succeeded in restoring power when nine “Kate” arived in turned and attacked a ship that can’t manoeuver. USS Hornet, now a sitting duck, had nevertheless determined AA gunners and still fighters nearby. All assaillants were short down but one managed to score a hit on her starboard side. It was the coup de grace: The electrical system was destroyed for good, massive flooding started and the ship started to list to 14° rapidly. Since new attacks were detected incoming by radar, the captain decidedit was futile to go on, confirmed by Vice Admiral William Halsey. He ordered CV-8 to be sunk while Captain Mason announced to abandon ship. USS Hornet sank slowly enough for him to tour the ship in search of trapped men inside, the last to leave. All survivors were picked by destroyers, which sent a torpedo boradside, taking nine hits (most duds), pushing the crews to pound her with 400 5-inch rounds (USS Mustin and Anderson). IJN Makigumo and Akigumo, on the hunt later found her, and finished her off Hornet with well working 24-inch (610 mm) Long Lance torpedoes. She capsized and sank at 01:35, on 27 October. 140 men have been lost with her.

USS Hornet sinking, 26 October 1942

Despite her short career of one year, six days, USS Hornet (CV-8) earned the American Defense Service Medal with “Fleet” clasp, the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with four stars and World War II Victory Medal, awarded to the captain and crew during a ceremony back home. The crew was later on board the new carriers of the Essex class and her air crew would acumulate victories as well until 1945.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen