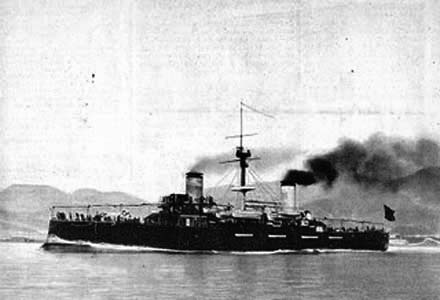

The Spanish armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón was a warship that was built for the Spanish Navy in the late 19th century. It was launched in 1896 and commissioned in 1897. The ship was part of a naval program that aimed to modernize the Spanish Navy and increase its ability to project power overseas. Cristobal Colon was heavily armored and armed with a variety of weapons, including guns, torpedoes, and mines. It was designed to be fast and maneuverable, with a top speed of around 20 knots.

During the Spanish-American War of 1898, Cristobal Colon was part of the Spanish fleet that attempted to break through the American blockade of Santiago de Cuba. In the ensuing battle, the ship engaged in a running fight with several American ships, including the battleship USS Oregon.

Despite its speed and armor, Cristobal Colon was eventually cornered and heavily damaged by the American ships. The ship’s captain, Emilio Diaz Moreu, chose to scuttle the ship rather than surrender it to the Americans. The crew abandoned the ship and swam to shore, where they were captured by American forces.

The wreck of Cristobal Colon was discovered in 2015 by a team of researchers led by the Cuban-American explorer Robert Ballard. The wreck is located off the coast of Cuba and is considered a protected cultural site. #spanishamericanwar #1898 #battleofsantiago #spanamwar #cristobalcolon #garibaldiclass #armoredcruisers

Among the best armored cruisers of her day

The Garibaldi class Italian armoured cruisers were among the best of their time, with a record construction for Italy of more than 10 ships (11 planned, one cancelled). They were primarily sold to Argentina (four), Japan (two), and saw service with Italy which had three, Varese, Guiseppe Garibaldi and Francesco Ferrucio (1901). Spain soon also considering the design, amidst rising tensions with the USA, notably to reinforce its Cuban fleet under admiral Cervera’s command.

These ships had been designed by chief engineer Edoardo Masdea, back in 1893, so it was still perfectly relevant in 1896. These cruisers combined rapidity, a powerful armament, and an overall satisfactory protection for their size. The last aknowleging delivery were the Japanese in 1904 a mere year before the construction of HMS Dreadnought and right on time for the Russo-Japanese war.

Cristobal Colon’s design

Cristobal Colon was, like the rest of the Garibaldi class, a very versatile ship able to hold its line in a fleet and play its standard cruisers roles as well, in between heavy cruisers and battleships. These ships were built quickly at a lower cost than most European shipyards becoming the first Italian major export success for such class of ship.

Naval architect Edoardo Masdea known improved much on the former Vettor Pisani-class, submitting to the admiralty a competely reworked design under directives of Minister of the Navy Benedetto Brin and in collaboration with Ansaldo Yard charged to built the first Argentinian ship (named Garibaldi). Speed was probably the most important improvement factor, notably to catch up with the latest battleship generation.

Compared to the Vettor Pisani, the new design was 1,000 tons heavyer to match nigh-impossibly stringent requirements, as the ship needed a far larger powerplant. So it was to combined a better armament and better protection for 20 knots. In the end, 40% of the total displacement went structural weight (not including armor), 15% to artillery, including ammunition 25% to the armor and 20% to the powerplant. The new cruiser was to have two twin gun turrets fore and aft of the superstructure with 8-in guns. However It ws revised, and in the case of Spain, the Italian solution was chosen, a twin 8-in aft, single 10-in forward.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

The hull was flush deck with a rounded stern and ram bow. The width/length ratio imposed by the machinery was more for agility than speed, but they were stable platforms and their superstructures not tall (the funnel were), almost completely symmetrical. The rudder was semi-compensated type to ease manoeuver.

Armour protection layout

Armor was of the Harvey-type, with case-hardened steel for high hardness. It was uniform up to the deck: The nickel-plated steel plating reached 150 mm (6 in) down to 80 mm (3.5 in) on both ends of the belt. The central battery was protected by 130 mm (5 in) sides and the armored deck had 38 mm (2 in) flat section, with a slight curvature to the sides. The main 8-in/10-in turrets were protected by 150 mm (6 in), and the 152mm/40 (6-in) were protected by 130 mm casemate shield. Underwater protection comprised a partial double bottom and heavy compartimentation.

Powerplant

Cristobal Colon was powered by two vertical triple expansion (TE), reciprocating engines, fed by twenty-four coal-fired small-tubes boilers. Suppliers depended of the yard, which was here like most ships, Ansaldo, Genoa. It seems she had 24 Niclausse boilers and developed circa 13,600 shp for 19.5 knots. This output was passed onto two shafts ended by three-bladed bronze propellers.

Her range was 4,400 nmi (8,100 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h).

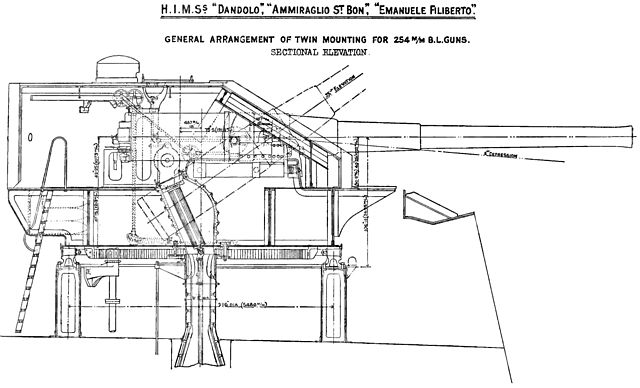

Armament

The main armament was specific to Cristobal Colon as designed: To the demand of the Spanish admiralty in 1895, Cristobal Colon was fitted initially with two Pattern R guns 10-inch guns: One forward and one aft. However the Spanish admiralty claimed the ones proposed by Ansaldo, Cannone da 254/40 A 1893, a patented version of the British ones, were defective, and asked for a replacement to Vickers Elswick, as the EOC 10 inch 40 caliber. However since the ship was urgently needed, she was sent to Cuba before this was done, and only ended with either only the initial aft gun or nothing at all as most sources states. She also gained ten smokeless powder Armstrong 6-in guns mounted in the hull casemates five on each side, instead of the Ansaldo models cannone da 152/40.

Thus, Cristóbal Colón should have been equipped with two 254mm (10 inches) cannons that were never fitted, leaving instead a different arrangement with a twin 8-in gun aft and not gun forward, leaving an empty turret.

Secondary

She had ten single 152 mm/45 (6 in) guns – Standard Ansaldo Type, 1 rpm, mv 830 m/s (2,700 ft/s) range 19.4 km (12 mi) in casemate along the battery deck.

She also hand six single 120 mm (4.7 in) guns Modello 1893: 5-6 rpm, mv 2,215 fps (675 mps), 9,900 yards (9,050 m), in the castes bridges fore and aft and in hull’s recesses.

Tertiary

It was rather on the light side, but making in numbers what it lacked in punch or range with the following:

Ten single 57 mm (2.2 in) guns: Standard 2.2 pdr (QF 6-pounder) Hotchkiss: 25 rpm, mv 1,818 fps, 4,000 yards (3,700 m) range

Ten single 37 mm (1.5 in) guns: QF 1-pounder pom-pom (liquid cooled): ~300 rpm mv 1,800 ft/s, 4,500 yards (4,110 m) range

Two Maxim machine guns. The latter were designed to be carried ashore on boats and cover landing parties

Torpedo Tubes

Colon was completed like the rest of the class with four single 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. Supposedly same as the Italian type, Whitehead 1893 model. Reloads unknown.

Spanish Cruiser Cristobal Colon, the only one sunk, during the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, 1898 Hispano-American war.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 6,840 t standard 7,400–7,700 t FL |

| Dimensions | 108.8/111.73 oa x 18.9 x 7.32 m (366 ft 7 in x 62 x 24 ft) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts VTE, 8–24 Boilers 13,000–13,500 ihp (10,100 kW) |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range | 5,500 nmi (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | (2x 254mm), 10x 152mm, 6x 120mm, 10x 57 mm, 10x 37mm, 4x 450 mm TTs. |

| Armor | Belt 70-150, CT 150, turrets 190, decks 100-150, barbettes 10-150 mm |

| Crew | 555 total, 578 as flagship |

Links/Sources

Books

Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan.

John Gardiner’s Conways all the world’s fighting ships 1860-1906, Italian section

Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921.

“Professional Notes–Italy”. Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. NIP

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books

Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge.

United States Office of Naval Intelligence, United States Navy (July 1901). “Steam Trials–Italy”. Government Printing Office

Nofi, Albert A. The Spanish–American War, 1898. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania:Combined Books, Inc., 1996.

El condestable Zaragoza. Crónica de la vida de un marino benidormense, 1998. R. Llorens Barber. Town Hall of Benidorm.

Links

https://www.spanamwar.com/colon.htm

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-fornv/spain/spsh-ag/cr-colon.htm

http://www3.udg.edu/fcee/professors/gcoenders/Colon.htm

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/italy/it_cr_giuseppe_garibaldi.htm

https://wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?149160

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_47-40_mk1.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_cruiser_Crist%C3%B3bal_Col%C3%B

https://www.spanamwar.com/colon.htm

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emilio_D%C3%ADaz-Moreu

Models Kits

https://www.super-hobby.fr/products/Cristobal-Colon-Spanish-Navy-armored-cruiser.html

Cristobal Colon’s short career

Cristobal Colon’s short career

photo

Cristóbal Colón was built in Italy under the initial name Giuseppe Garibaldi (ii), second ship of class and name, laid down in 1895, launched by September 1896, and sold to Spain, then delivered at Genoa to a Spanish crew, and taken in hands on 16 May 1897 with a transfer ceremony. She was the Spanish Navy’s first true armored cruiser and her best cruiser so far. Due to the Spanish Ministryrejevting her planned main guns, she sailed without them in the hope to be able to fit some later. This was never done.

Impressed in the Spanish Navy’s 1st Squadron as tensions with the United States were degraded after the explosion and sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor on 15 February 1898, she was prepared for war. The squadron was at first concentrated at São Vicente, in Portugal owned Cape Verde Islands. She arrived in Cadiz for preparations and departed on 8 April, learning of the war breaking out while off São Vicente. She was at first sent in by neutral Portugal toi recoal, but due to international law she had to leave within 24 hours of the declaration of war.

Thus, Cristóbal Colón and the rest of Cervera’s squadron was underway by 29 April, heading for San Juan in Puerto Rico. They needed to recal mid-way and stopped in French Martinique, Lesser Antilles, on 10 May 1898. While the bulk of the fleet stayed in international waters, only two Spanish destroyers entered Fort-de-France to ask for coal, but France pushed its neutrality and refused to supply coal. Thus Cervera had to sail out on 12 May 1898, heading for Dutch Curaçao (Western Indies) expecting to meet a Spanish collier here.

Cervera arrived at Willemstad, on 14 May 1898. The approach to neutrality was different. Given the emergency context, the Dutch authorities only authorized Cervera to send the cruiser Infanta Maria Teresa and her sister ship Vizcaya, and to load only 600 long tons. The meagre coal stock as later distributed between his ships and on 15 May instead of San Juan, now under U.S.N blockade, he wanted to make it to the still free Santiago de Cuba, at the the southeastern tip of Cuba.

Santiago’s Blockade

He managed to arrive on 19 May. The admiral hoped to refit his ships before being trapped, and recoal as well. But he was caught still there when the American “flying squadron” arrived on 27 May 1898, initiating the blockade, a 37 days long affair.

Cristóbal Colón at the time was anchored in the entrance channel. This was on purpose to support Santiago’s shore batteries. On 28 May she was spotted and recoignised by a naval detachment of the American blockade fleet. Therefore, admiral Sampson was to attack her in priority, recoignised as the best asset in Cervera’s fleet. Little they knew she lacked her main guns at the time. At 14:00, 31 May, the battleships USS Iowa and USS Massachusetts as well as the cruiser USS New Orleans closed in and opened fire on Cristóbal Colón, also engaging the shore fortifications from 7,000 yards (6,400 m). Both the Spanish cruiser and coastal artillery answered. A cease fire was ordered at 14:10 to assess the damage, whereas the Spaniard went on firing sporadically until 15:00. As seen above, Cristóbal Colón only had her casemated guns, cabable of 19.4 km (12 mi), so twice the normal range. But accuracy was still poor, and no side many any impression.

The blockade went on and the US fleet returned for an occasional gunnery duel or bombardment of the harbor. Cristóbal Colón was partly stripped of her crew, which joined others forming an ad hoc Naval Brigade sent to fight the U.S. Army inland as they approached Santiago de Cuba. It is likely also her two Maxim maching guns were also landed and sent with her contingent.

Cervera’s “mad run”

By early July 1898, this threat to Santiago de Cuba inland was closer and Cervera, being pressured by the government to act, having for them enough time to prepare, was forced to try a run out in the open sea, which he decided on 1 July 1898, to start on 3 July 1898. In between the crew of Cristóbal Colón was recompleted as the Naval Brigade inland was dissolved for this operation. The entire day was spent preparing for action, but Vice Admiral Cervera chosed Infanta María Teresa as his flagship. He took the lead and chosed a bold approach, sacrificing his ship by drawing fire frm the blockade fleet, to enable others to escape in several directions. He setup a plan to attack the fastest American vessel at the time, which was the armored cruiser USS Brooklyn, while Cristóbal Colón and the rest would make for it westward in the open sea.

At about 08:45 hours this 3 July, his squadron arrived in a single column and Cristóbal Colón was third in line. She was behind the flagship Infanta María Teresa, her sister Vizcaya, and Almirante Oquendo (third of the class) behind Colon, as the destroyers Furor and Plutón also right behind her. Sampson’s squadron sighted them at 09:35 and general quartrers alarm was heard on all ships. The opposition comprised, in addition to Commodore Winfield Scott Schley’s “Flying Squadron”, Sampson’s armored cruiser USS New York, Schley’s armored cruiser USS Brooklyn, while their best core was comprised by the slower but hard-hitting USS Indiana, USS Massachusetts, USS Iowa, and USS Texas, to which USS Oregon, coming from Mare Island, California and only battleship defending the US West coast, was to be added, making 66 days run to Cuba. Both forces were united under command of Sampson. On his side, Cervera only hope was to allow his three cruisers to out-run the battleships, and himelf trying to retain the fleet as long as he could.

And thus the Battle of Santiago de Cuba began. Infanta María Teresa and Vizcaya soon engaged USS Brooklyn, and Cristóbal Colón as well as Almirante Oquendo, and the two destroyers speeding up westwards out on the open sea. USS Brooklyn turned away from Infanta María Teresa and eventually all four Spanish armored cruisers stayed in line, heading directly at the armed yacht USS Vixen.

Cervera managed as he hoped, to escape. Thus the US squadron started a “hot stern chase”, steaming along a mile to port, slightly behind and all guns blazing along the way. Cristóbal Colón managed to hit Iowa twice with her casemate guns. The battleship’s dispensary was destroyed and she was holed belowed the waterline, taking some flooding, but still firing. Outgunned, the Spaniards were hit by 12-in shells (or 10-in from Texas and the two cruisers) which were armor piercing, making untold damage, while the range was close enough for secondary guns on both side to rain down high explosive shells, destroying superstructures and ingiting fires.

The cruisers started to ground themselves before theirr magazines could explode and save their crews, Infanta María Teresa being first, ending 10:25 west of Santiago, Almirante Oquendo was beached a few hundred yards away at 10:30 and Vizcaya in turn at 11:06, making it ashore. Alfredo Villamil (Spanish inventor of the destroyer)’s Furor and Plutón were soon devastated and sank in turn. The whole squadron only comprised Cristóbal Colón, which found iself alone, but also the most resilient of the pack.

Cristóbal Colón’s lone hour race

Her captain thought he still could get away, but her uncared machinery failed to give her expected 19 kts top speed after all this time, but she proved her extraordinary resilience so far, hit by two 5 or 6 inch hits, and still maintaining 15 knots (28 km/h). Only USS Brooklyn (capable of 20 knots – she even reached 21.91 knots on Trials) still was maintaining her chase 10 km behind her. USS Vixen followed Brooklyn, and next was the USS New York also maintaining 20 knots and now closing. The rest of the line comprised USS Texas, Oregon also in forced heat (they still can maintain 15 kts).

A full hour passed, after which Cristóbal Colón burned all her “best coal” and had to carry on with inferior grade, coal, resulting in thicker smoke and lesser output. Mechanically, she started to loose speed, from 14 to 13 and soon 12 knots. Soon the whole hunt was about to end: At 12:20 USS Oregon managed to land a 13-inch (330-mm) astern of her, and sen more closer, while the two armored cruisers managed to straddled her with 8-inch (203-mm) rounds.

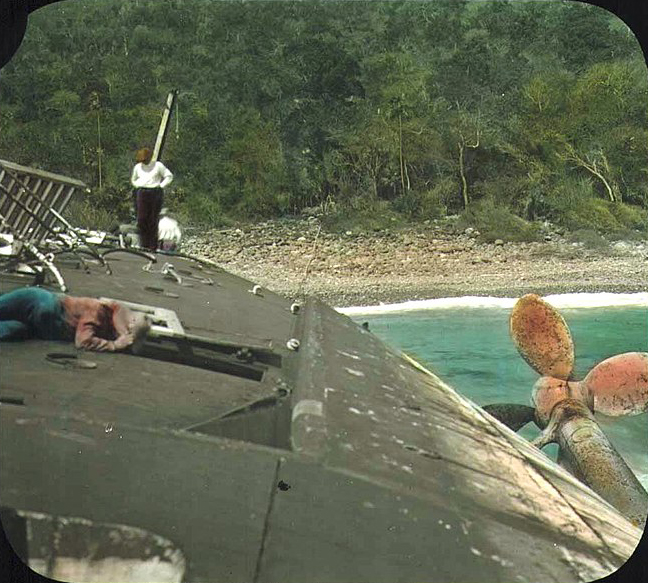

Slowly but surely as the speed went down they were about to find their mark. The Spanish cruiser could do little but reply with mostly innacurate fire. She was hit six times but when the distanced closed to 2,000 yards (1,830 m), Cristóbal Colón’s Captain Emilio Díaz-Moreu y Quintana decided there was no hope of winning this one. He decided to beach his cruiser at the mouth of the Turquino River, located 75 miles west of Santiago (and probably signalled it for the US fleet to cease fire).

Emilio Díaz-Moreu’s report:

Complying with the orders received, I left with the ship under my command, occupying the designated position, from the port of Santiago de Cuba, being both ahead of the Morrillo at 9:45 in the morning, opening fire against the Iowa, which was the ship nearest at the time of departure.

Five minutes later, the Brooklyn being the most advanced ship in the enemy line, I ordered the batteries to direct all fire on her and whatever possible against the Oregon, which was on the port wing and which was not attention could be devoted due to lack of guns hunting and retreat. This was done, firing 184 shots against said ship with the 15 cm cannons and 117 with the 12 cm battery, having the certainty of having hit the target with 10 percent of the shots.

– Of course I saw that neither the Brooklyn nor the Oregon, which hunted me down, could catch up with me and the first one stayed faster than the second one and I continued close to the coast heading towards Cabo Cruz.- At 1 in the afternoon the boiler pressure began to drop, reducing the revolutions from 85 to 80, beginning, therefore, to win over the Oregon, which shortly after opened fire on the ship with its large-caliber hunting guns, which I could only answer with shots from the number 2 gun of the battery, winking to that effect as necessary, even if this shortened the distance.

– In view of this and given the absolute certainty of being captured by the enemy, according to Your Excellency, as it would not be advisable to distract any Chief and Officer from their destinations, given the structure and layout hatches, which represented a much-needed loss of time and with the aim of taking advantage of the opportunity, if it presented itself, to fire, and in order to avoid being captured, we decided to run aground and lose the ship and not sterilely sacrifice the lives of those who had fought with the heroic courage, discipline and seriousness that Your Excellency has been able to appreciate for yourself, and as a consequence of the agreement, we headed towards the Tarquino River, on whose beach I ran aground, with speed of 13 miles, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. Once the ship was beached and the Chiefs and Officers assembled, they all expressed their agreement to what had been done, understanding that if they continued, even for only a few moments, they were in imminent danger of falling into the hands of the enemy and being a war trophy that was necessary at all costs to avoid.Shortly afterwards we became prisoners of war on the Brooklyn, the Commander of which appeared on board shortly after. During the combat I had one dead and twenty-five wounded, whose list accompanied Your Excellency as a result of the enemy projectiles, which although they hit us in large numbers, did not cause damage to the protected part of the ship.

At 13:15 hours he ordered to open valves to scuttle his ship, preventing capture. The cruiser started sinking while sailors jumped out and tried to swim ashore. What they failed to realize was that they had been tracked by Cuban insurgents along the coast, which made all the way to this area, and started to shoot from the vegetation cover. Understanding what was happening, Sampson ordered to signal the insurgents to cease fire (apparently some that made it to the beach were butchered with machetes). He also ordered boats to be sent and rescued survivors still on the ship. Captain Díaz-Moreu survived the battle and was taken in custody until the end of the war.

She ship capsized, photo made by the USS Vulcan salvage team afterwards.

A colorized photo of Allison.V Armour in 1899 of the wreck being inspected.

That night a USN salvage team from USS Vulcan reported to Sampson that the Cristóbal Colón was worth salvaging. They managed to have her towed away, only to realize she had been scuttled and the flooding caused her so quickly capsizing and sink. The wreck is now part of the Naval Battle Underwater Park of Santiago de Cuba, open to divers.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

If possible could we be seeing a cold war Ukrainian navy and great work with the wedsite

Hu Jacob !

It’s currently in the works. Small navy with a young and interesting history, and hot topic indeed.

David