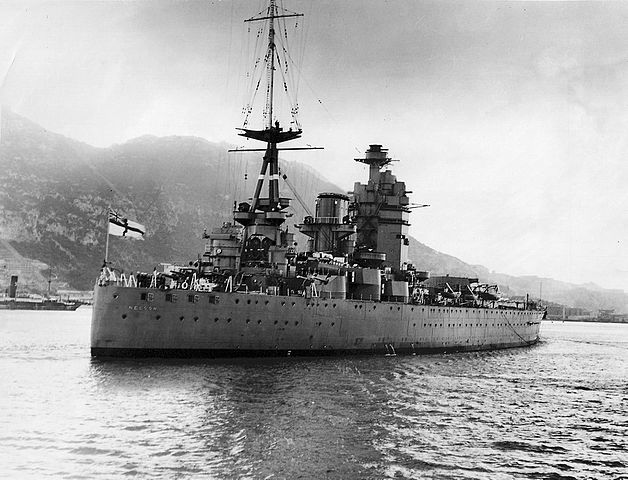

The Nelson class were two British Battleships completed in 1927-28. These were one of these icons of WW2, rather more diverse in terms of battleships, in terms of quality rather than quantity compared to WWI. After the rapid cost rise in capital ship the 10 years moratory signed with the treaty of Washington would ensure that the Royal Navy would have no new battleships between the Revenge class of 1915 and the King Georges V in 1936. With one exception, at several titles. The world’s only battleship completed in the 1920s (outside the two Nagato class completed in 1921, close to the West Virginia) were the two Nelsons.

They were the only exception to the Washington treaty, and ships really designed with as many lessons of WWI and the battle of Jutland as possible: Having firepower and protection privileged above speed or other considerations. Their most striking aspect was their odd look, unique and never repeated but by the French (Dunkirk/Richelieu), the fruit of reflections on armour more than gunnery tactics, as their heavy artillery. These were not for “crossing the T” but due to weight savings, with a reduced citadel length which dictated the position of all their artillery at the front. Thus they were pure “treaty battleships”.

Operationally, they did their share of action. After many years to finely tune up training, unlike the King Georges V class (KGV) when WW2 broke out, they served with distinction in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Indian oceans, Rodney co-sinking the Bismarck in May 1941, both bombarding targets in Normandy and doing escort work as the wildcard of each one, ensuring no German capital ship would ever venture near them.

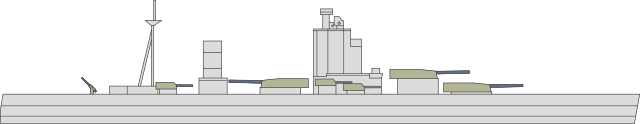

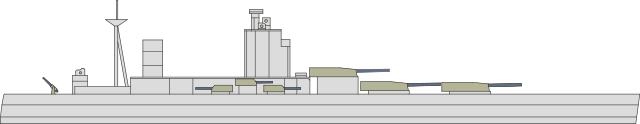

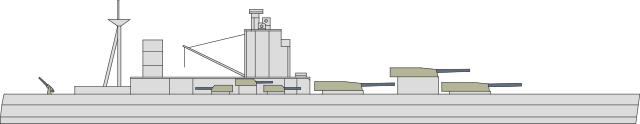

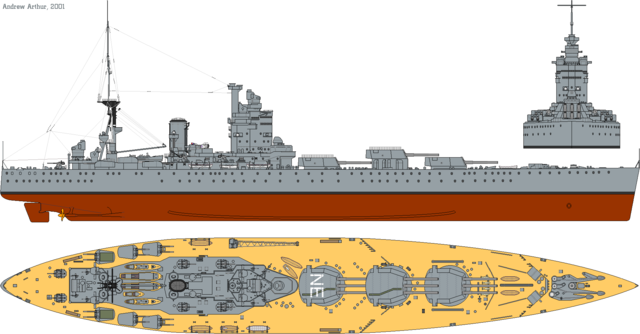

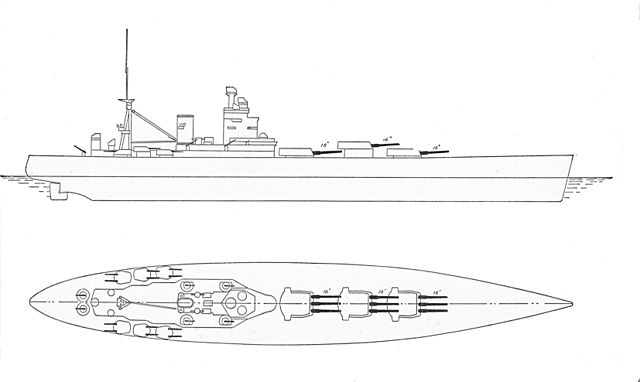

The N and O designs, and other early designs

O3, P3, Q3 design variants

Design blueprints general

Most of what was seen about the N3 class battleships and their development is related to the Nelson class development. They were basically a cheaper proposition, dubbed “O”.

The next generation of British warships were to be massive, heavily armoured, much larger and stronger still and perhaps worthy of “hyper-battleships” if there was ever some. The G3-class battlecruisers were designed first, and carried 16-inch (406 mm) guns while the N3-class battleships carried nine humongus 18-inch (457 mm) guns. The Royal Navy wanted her absolute qualitative edge and dominion above all navies at the time, including fresh contenders like the US and Japan. This registered itslef in the mother of all arms race, with staggering budgets, at the time battleship was the ultima ratio of the states, the deterrence of its days.

Project Q3

In the wake of pacifism of 1919, politicians soon saw the budget-guzzlers these new ships put forward by their amdirakties as a threat to peacetime reconstruction and stability, and at the US initiative, all agreed to gather at Washington to sign a Naval Treaty in 1921. It had one only goal: Stop this folly of naval construction, and severely limit the size and scale of fleets of that time. Signed in 1922, it saw a lot of scrapping or reconversions in its wake.

The four G3 battlecruisers were cancelled, while the N3 battleships were not even laid down. Some of the material acquired was later reused for the future Nelson and Rodney. The Treaty limit not only battleships size due to a 35,000 tons limit, but armament with 16-inch guns maximum, while banning construction for ten years and allowing a global capital ship tonnage to be respected as well.

Project O3 modified

The British admiralty however successfully pushed its diplomatic assets and ensured that the definition of maximum displacement was standard and not fully loaded, excluding fuel and boiler feed water. The British Empire needed long range and thus, large ships. They did not wanted to be penalised compared to other nations which vessels operated much closer to their home bases. This enable a provision, allowing engineers to create water-filled internal anti-torpedo bulges as part of the “dry” (standard) weight. A clever way to add protection within the treaty limits.

The admiralty still negociated to have two battleships authorized anyway, but had to make drastic compromises in the design, to reach the stenuous treaty limits. Thus, the admiralty started studies for a radical new warship design. It was a derivative of the numerous proposition studied in 1920, and drawn from the “G3” and “N3” designs by Eustace Tennyson-d’Eyncourt, the Director of Naval Construction from 1912 to 1924. The O design (and its final iteration called O3) being the most modest, it was the one ultimately chosen to proceed forward:

-The O3 design was the smallest of these all. Initially rated at 41.250 tons FL, measuring 216,4 x 32,3 x 10,2 m, powered by 45.000shp, on 2 shafts, protected by a 356 mm (15 in) belt and 159 mm (6.5 in) armored deck, she had three triple 406 mm Mark I (3×3) guns, plus a secondary armament of 152 mm Mark XXII (6×2) and 120mm Mark VIII (6×1), 40 mm AA guns and two 622 mm TTs.

-As revised after discussions, the final O3 design reached 44.000 tons FL with the same dimensions, same protection, main armament but a new generation of DP guns, 133 mm Mk.I (4.5 in) and 114 mm Mk.II, more extensive AA, same tubes and a floatplane.

The “G3” and “N3” had two turrets forward of the bridge with the third between the bridge and funnels. On the alternative design “O3”, “X” was superfiring over both “A” and “B” turrets. Secondary guns were in enclosed director-controlled twin turrets, on the upper deck level and different positions were tried out. Eventually they were taken out the G3 and N3 own design, all grouoed aft.

Finalization of the design

Project O3, 3rd variant

The Nelson class, inlike the fancy designs cancelled, was a small and conservative vessel sacrifiing space for installed power, limiting speed in order to still be well-armed and protected. The “Cherry Tree” class was “cut down by Washington”. It’s not they were unwanted by the admiralty. On the contrary they contained a lot of new ideas the Royal Navy was eager to explore. The limited displacement resulted in a smaller armour weight than usual, only possible by concentrating the artillery and reducing the citadel. A known “trick” used by many navies on cruisers afterwards (like the Zara class) to stay in the treaty limits.

Machinery limited weight and size was helped by a streamline hull (internal hull), more compact and powerful boilers, and two shafts with unusually large screws. Quite a change from the usual four screws system. Even the following King Georges V reverted to four. Boiler rooms were moved behind the engine rooms in a compact way so as the exhausts could be truncated into a single funnel as far as possible from the bridge. This further helped reduced the overall length of the armoured citadel. Also to help speed, the hull had a new, very efficient hydrodynamic form well tested with models.

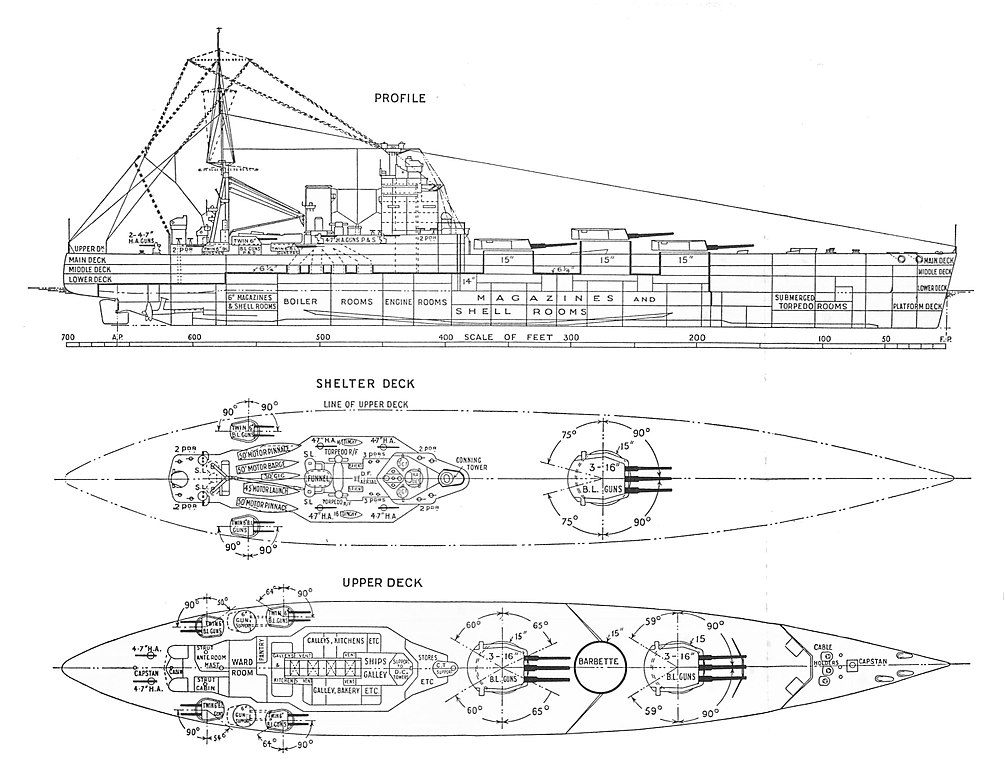

As for artillery position, the long debate was closed with the seemingly best combination: All three front turret had “B” turret superfiring over “A”, and “X” turret on the forecastle deck, behind “B”. It had the worst arc of fire, unable to fire forward and limited to fire aft. “X” turret in some publications was called “C” turret, but the usual coupled A-B and X-Y remained mainstream.

Design Genesis of the Nelsons

The Nelson are interesting and atypical battleships. They were compromises directly derived from designs developed in 1918-1920 that took into account the lessons of the Great War at sea, and especially and especially the Battle of Jutland, the only major commitment or the ships of the line were seriously tested. Most naval engagements of the Great War were skirmishes of battle cruisers. On the other hand, Jutland showed the limits of their concept. Against other similar buildings (here in this case Germans), protection was essential. The British losses were mainly attributed to this undeniable factor: The protection of German buildings comparable was much better, as the engineers discovered much later by analyzing the wrecked Hindenburg wreck at Scapa Flow in 1919.

The many designs that were developed by the admiralty thus consisted in tending towards a battleship battle cruiser model, in fact the prototype of the “super-battleship”. Thus in the folds, were developed battleships of the type G3 armed with 406 mm pieces and others type N3 armed with parts of the type N3, 457 mm. All the other nations of the time were thrown into the same escalation of power and tonnage. The treaty of Washington (1922) came to put a good order. In particular, it halted the continuation of the construction of the Hood (1920), leaving the latter without sister-ship and killing in the ouef most projects, stopping net construction of other buildings in progress.

Thus, it is by modifying the plans of the G3 that the Admiralty managed to render “in conformity” with the treaty their future Nelson. But this inevitably led to many compromises in order to satisfy the treaty while at the same time protecting the armament/protection/speed balance. In fact they were nicknamed after their entry into service as the class of “Cherry tree”, the “trees pruned in Washington”. The “dry” displacement (excluding oil and ballast) projected was 35,000 tonnes. The main artillery was placed in the front, not to counter the conventional tactic of “bar the T”, but to reduce the weight of the armor by restricting the length of the battleship.

Design

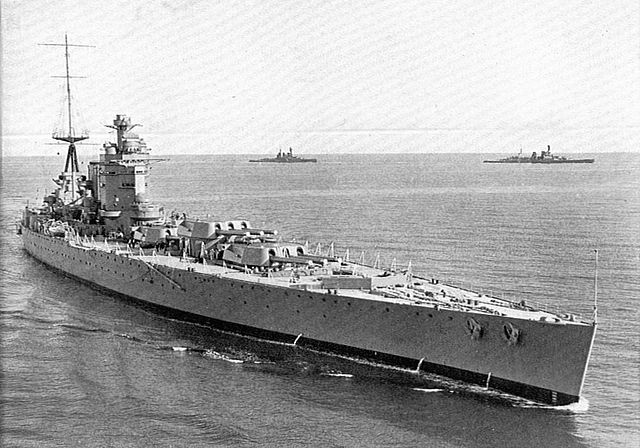

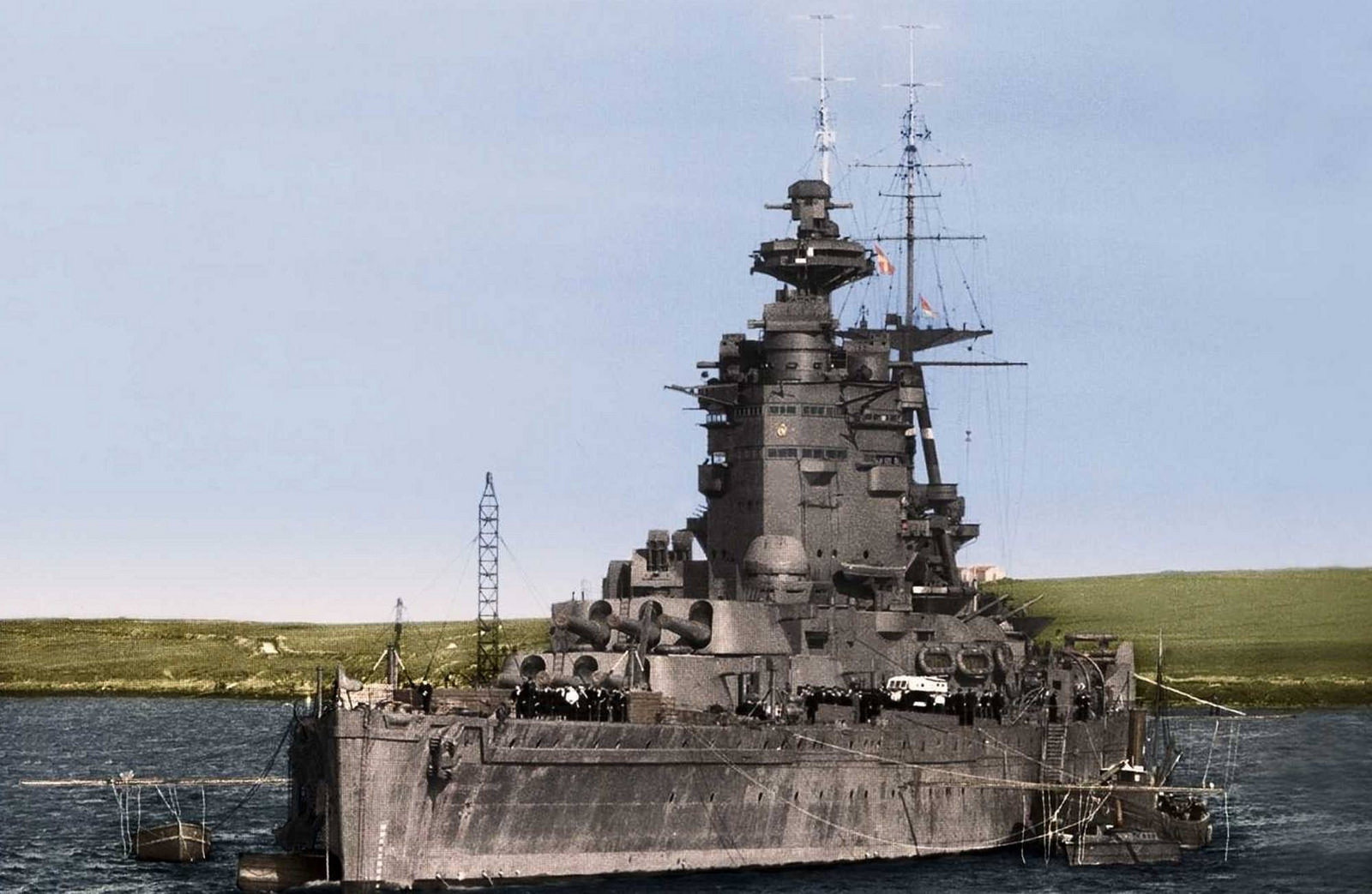

HMS Nelson in the 1930s

General construction, hull and accomodations

The Nelson and Rodney were started in 1923-24, launched in 1925-26 and completed in 1927. They had been built partially by reusing material from ships canceled after 1922. They were the first battleships “treated” with the King George V after a moratorium of ten years, and the first of a new kind. They were not, however, really “fast battleships” because of the many concessions made to the tonnage.

Their rather unique deserved them the nickname “queen anne’s mantion” as the brick buildings it recalled (14-storey opposite St James’s Park tube station in London) and to save weight, largely made of aluminum. The shape, height and position of the superstructure also as feared when thoerized for the N and G classes, acted as a “sail” in the heavy north wind, distorting maneuvers at low speed. Both were not agile, with a very long turning circle.

The Nelsons kept their general dismensions from the O3 design: Their length between perpendiculars was 660 feet (201.2 m) and overall 709 feet 10 inches (216.4 m). Rodney was a tad longer at 710 feet 3 inches (216.5 m) but both had the same beam at 106 feet (32.3 m) and 30 feet 4 inches (9.2 m) draught at mean standard load “dry” and 33,300–33,730 long tons (33,830–34,270 t) standard load, and finally 37,430–37,780 long tons (38,030–38,390 t) when deeply loaded. They easily stayed below the required Washington tonnage.

HMS_Nelson_outline_and_plan_Warships_To-day_1936

Their crew amounted to 1,361 officers and ratings as flagship, but in normal condition circa 1,200, and 1,314 as “private ships” (when requisitioned to carry the nobility of statesmen). They metacentric height was 10.2 feet (3.1 m) when fully loaded, making them “stiff ships”: They had a quick roll between 11.2 and 13.6 seconds. In calm weather they were very manoeuvreable but as saif above, their tall superstructure as feared acted as “sail” in gigh winds and interfered. They had aplenty weather helm, especially in confined spaces. In fact this was shown when Nelson ran aground off Southsea beach in 1934.

Superstructure

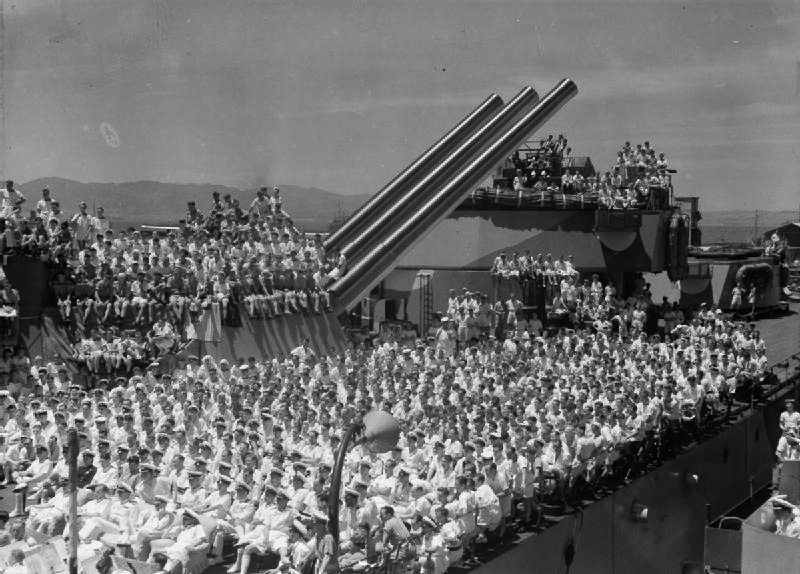

Sailors and a 4.7 in AA on Rodney 1940, with the bridge tower behind

The large superstructure was another revolution in the design. Planned already for the G3/N3 designs, it was a way to get rid of the traditional bridges and platfoms mated ona tripod. The one on O3 was basically unchanged, octagonal in plan or “Octopoidal” and provided spacious and weatherproof working spaces unlike open platforms, for the navigating officers and flag officers, especially important as flgaship. This innovative bridge design was also imitated by the French on the Dunkerque and Richelieu-class designs, but also by rebuilt battleships like HMS Warspite.

Still, there was a conning tower at its base with thee main gun directors mounted on top. But superstructure was lightly armoured and protected only against splinter, used aluminium for fittings, and fir instead of teak for deck planking, although teak replaced it in the late 1920s as it was believed a full broadside blast was to cause structural damage. The location of the superstructure towards the stern revealed issues in high winds and at low speeds and a “weathervane” effect, a problem in tight spaces and crowded harbours. The Nelsons were also difficult to manoeuver when moving astern due to their single central rudder, out of the propeller race.

In the early stages of the ship’s first commission, there was a general misconception that the Nelson class were unhandy and difficult to manoeuvre. Both my predecessor and myself, however, very soon discovered that this opinion was entirely fallacious! In calm weather, the ship’s manoeuvring capabilities are in no way inferior, and in many ways superior to those of Queen Elizabeth or Revenge.”

– Captain Hugh Binney

Powerplant

The machinery was reworked, and for the first time since the dreadnought it came back to two propellers. More efficient boilers and oil heating made only one funnel sufficient after truncating the fewer exhausts.

In detail, they were powered by two sets of Brown-Curtis geared steam turbines, each with its own shaft propeller. Steam came from eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers, oil-fired, and all fitted with superheaters to operate at a pressure of 250 psi (1,724 kPa; 18 kgf/cm2). The geared steam turbines were rated at 45,000 shaft horsepower (34,000 kW). The hull was hydrodynamically trimmed for maximum efficiency, but in the end speed was not to exceed 23 knots, which was hardly better than the “classic” dreadnoughts of pre-WWI. As designed it was rated as 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph).

Still, both exceeded their designed speed in sea trials, by 1927: They reached 23.6–23.8 knots (43.7–44.1 km/h; 27.2–27.4 mph) when pushing their machinery to 45,614–46,031 shp (34,014–34,325 kW). For auto,omy they carried 3,770–3,805 long tons (3,830–3,866 t) of fuel oil. This was enough for 7,000 nautical miles (13,000 km; 8,100 mi) at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). Of course when chasing a fast battleship, so at max power, this fell considerably. That was shown in the “Bismarck chase” in May 1941, when Rodney was short of oil shortly after she met the crippled Bismarck. If that was not for a Swordfish’s lucky hit, she would have been forced to stop her chase. Resplenishment at sea was a completely novel concept at that time, it just did not existed yet.

The Nelson class was not the most agile ship, due to the single rudder and tower bridge acting as a sail, but in general they still handled well, hwving a comparatively small Tactical Diameter when turning into the wind. Lt. Cmdr. Galfry Gatacre RAN in 1941–1942 as Navigator reported no difficulty to slip through the boom gates at Scapa Flow and in fact, never bumped them as passing through Hoxa Sound, unlike almost all other British battleships.

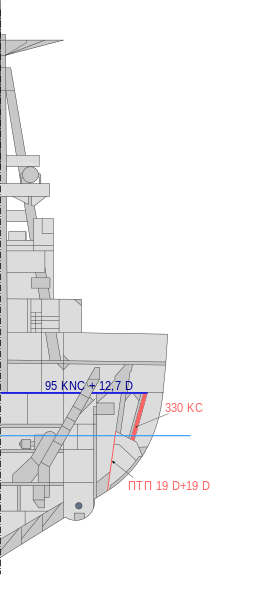

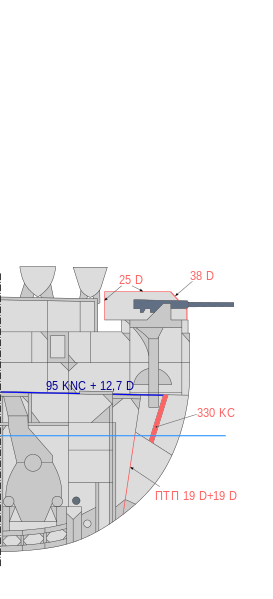

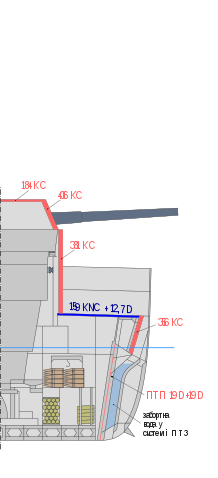

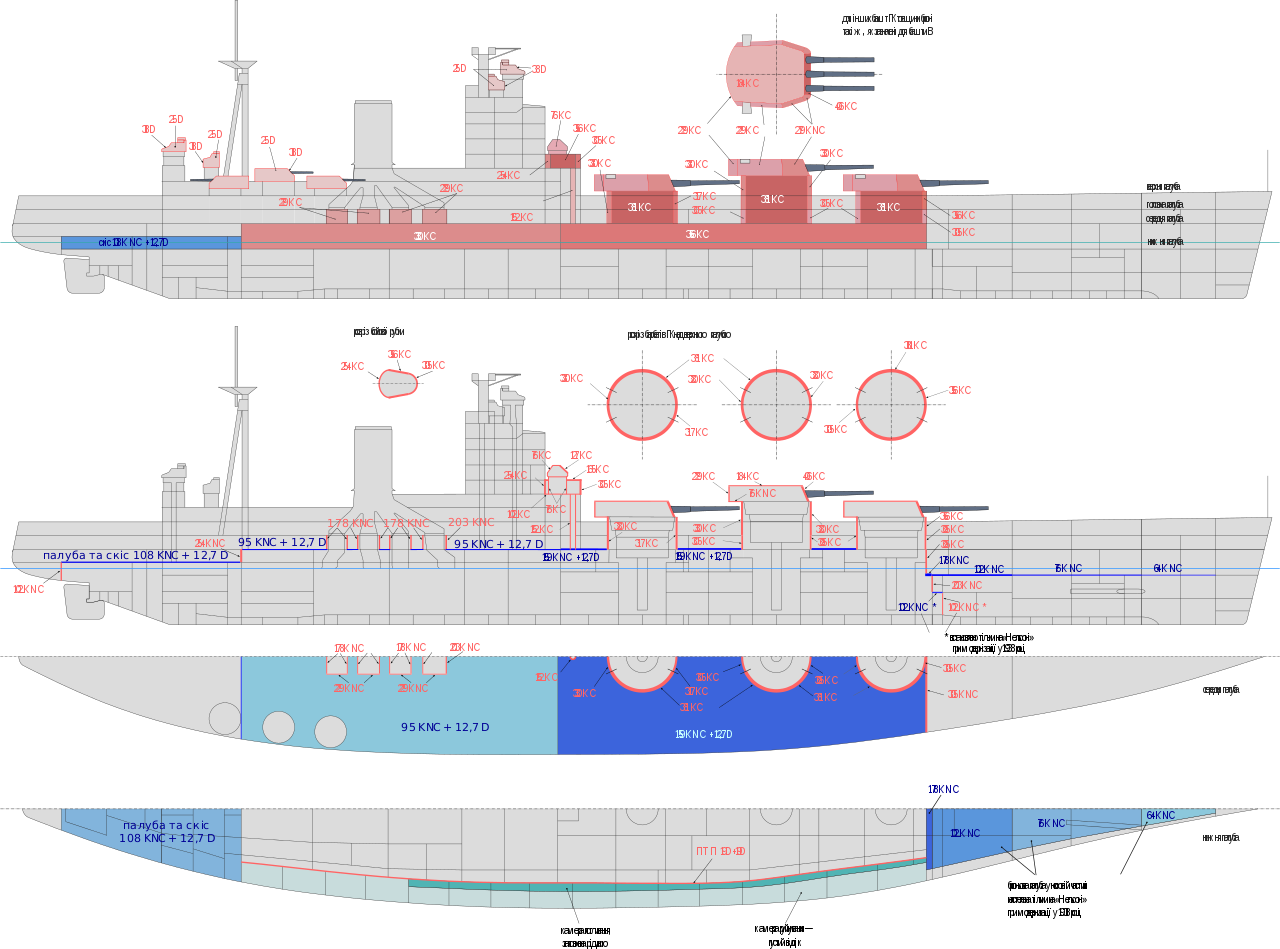

Armour Protection

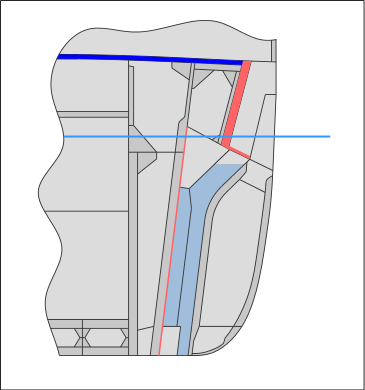

The general principle was the US-inspired “all or nothing” with in unprotected areas, still the addition of many thin layers. Protection was generally internal, which was its main feature, using deflecting and non-straight surfaces. The belt was invisible from the hull externally. On the other hand for the first time, they had an excellent vertical protection, with sloped transitions to counter plunging parabolic fire and aerial bombs. The external hull of the ship was unarmoured but fitted between the hull and sloped armour by large internal longitidinal torpedo bulges which can be fill in part, rising the displacement. The idea was alayed defence which would initiate detonation, exploding outside the armour itself, like a modern add-on armour.

Nelson class proposed armor changes in the layout

The absence of external torpedo bulges had two faces: On one, it made the hull much cleaner and benefited speed. On the other it reduced internal space, much to the annoyance of engineers tasked to fit in the large machinery. The ASW protection was also layered and was similar in design and effectiveness to HMS Hood. It was calculated to withstand a 750 lbs (340 kg) TNT warhead. The other innovation was the protection against airplan bombs as shown by the early 1920s tests, and for the first time, a British Battleship was fitted with a specially designed single armoured deck instead of a 3-layered vertical defence as on HMS Hood. The turret used Non-cemented (NC) armour also. Here is the detail:

- Inclined armour belt sloped outward 18°.

- 14 in (360 mm) over the main magazines and control positions

- 13 in (330 mm) over the machinery and 6

- in guns magazines.

- Internal torpedo bulges: Water

- filled/Air filled compartments sandwich.

- Double bottom 5 feet (1.5 m) deep: Empty outer watertight + inner water filled comp.

- Torpedo defense system 12 feet (3.7 m) deep

- Torpedo bulkhead backing 1.5 inches thick.

- 6.25 in (159 mm) thick armoured deck

- 3.75 in (95 mm) extra armour layer over the machinery spaces

- 4.25 in (108 mm) extra armour on the lower deck over the steering space

- 0.5 in (12.7 mm) Weather deck plating.

- Main turrets faces 16 in (410 mm) NC armor face

- Main turrets sides 11 in (280 mm)

- Main turrets roof 7.25 in (184 mm)

- Main turrets backs 9 in (230 mm)

- Main turrets barbettes 15 in (380 mm)

- Secondary turrets 1 in (25 mm) NC all round

- Secondary barbettes and structural steel plates 0.5 in (12.7 mm)

During her January 1938 refit, Nelson received extra armor, but not Rodney: An additional 70mm or 76mm (3 in) thick plating was added on the lower deck forwardd from the 12-in fore bulkhead, extended by 102 mm (4 in) plate to the double bottom. it’s also possible her torpedo room was removed entirely at the same time, but seems to be still present on Rodney in 1945.

Armament

Nelson firing during trials in 1928

New guns for new problems

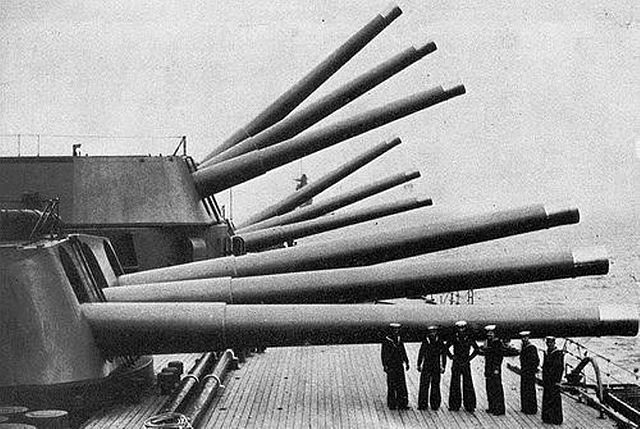

Their main armament was mounted in triple turrets forward, a unique and never repeated scheme anywhere. The Next KGV combined quad and twin turrets and all previous battleships since the 1880s had twin guns. These new 16-in guns als had an interesting story of their own:

Previous practice was to fire heavy shells at a moderate velocity. The Nelson’s main guns, followed however the German practice: Lighter shell at higher velocity. This came from the Director of Naval Ordnance policy as a conclusion of British testing on war prizes.

Cleaning the rifled 16-in inner barrels, HMS Rodney, September 1940 (IWM)

But further testing proved contradictory and led to design two different rifling rates and test a mixture of barrel types in different turrets or in the same turret altogether. These new guns suffered heavy barrel wear and of a large dispersion pattern. While testing several riflings numerous refurbishings were made and to compensate for it, muzzle velocities were reduced and a heavier shell was tried but its cost and changing both handling and storage arrived when the RN was in full cutting cost sprey.

Overall, the Navy never considered them as successful as the beloved BL 15 inch Mark I. There was also a third model that pushed the models in the contrary way, the BL 14-inch Mark VII of the King George V-class battleships which were back to a heavier shell but at lower velocity. They were undone by an over-complex mounting. On the Nelsons, to combat dispersion, large triple mount turrets were used, with full armored seeratuin between each mounting.

Turrets

HMS Warspite passing forward of Nelson’s prow, showing the “B” turret roof.

Still, these guns proved problematic to make, showing early problems with ammunition handling and loading. The heavier turrets also caused greater stresses on roller bearings, solved by incorporating of spring-loaded vertical and horizontal roller bearings combined. Howver problems were cured enough for that in October 1929, a turret crew managed to load and fire 33 consecutive rounds in a row without issue. Lighter materials meant more fragile equipment more maintenance and replcement intensive though, but were dictated by weight saving measures.

Firing trials reveals issue, between ‘A’ and ‘B’ turrets in forward fire: They caused damage to weather-deck fittings while the mess-decks were badly shook, with many broken apparels. There was for many years a rumour (just as on HMS Agincourt before) that the new battleship could not fire a full broadside without major structural damage. This was proved false when engaging Bismarck as Rodney fired 40 broadsides, so 380 shells without damage except for the deck planking, upper deck fittings, sickbay fittings, partition bulkheads, toilet bowls, plumbing and light bulbs in the forecastle.

When ‘X’ turret fire at 30° bearing abaft the beam and 40° elevation two rows of bridge windows were damaged. As a result they were prohibited from firing abaft of the beam at high elevations in peacetime. Tempered glass in bridge windows was tried but shattered also. The Captain’s bridge was altered on Nelson to reduce its the window area and having its upper portion sealed. Fitting of protective ledges below the new smaller windows proved successful at last in the late 1930s.

Nelson and MS Johan van Oldenbarnevelt in Oslo, 1933

Also, a new enclosed Admiral’s bridge with reduced, reinforced windows was built on top of the Captain’s bridge. The forward signalling lamps were moved up one level to avoid damage, further aft of the bridge. The Admiral’s bridge on Rodney was still stepped back from the forward edge of the tower but same measures were applied to the Captain’s bridge, and with larger ledges. Blast also caused concussion of the observers’ own eyeballs when applied on the sights when firing; thus they were usually told to back down when firing.

Main: 3×3 16-in/45 (406 mm) Mark I details

Rodney’s main gun broadside

Originally intended for the “G3” battlecruisers, canceled due to the Washington Treaty, those on order were redesigned slightly to be used on the O3 design (Nelson). They were the last wire-wound guns built for the Royal Navy. Their difficult firing trials was in part due to the belief of the Director of Naval Ordnance about high-velocity, low-weight projectile having superior armor penetration characteristics at larger angles of impact, opposite to previous studies. It was never substantiated by later trials but development was too advanced to back down. In the end, despite the larger caliber, these new 16-in ended only marginally better for armor penetration than the 15″/42 (38.1 cm) Mark I but paled in comparison both for the much shorter barrel life, dispersion and accuracy.

Main shell lifted in supply

It was not until 1934 that Nelson’s guns were first fired in 16-shots per gun sequence, after a myrid of teething problems, resolved one after the others. Many breakdowns still occurred and it was only by 1939 that most problems were rectified. The mountings still suffered many mishaps and were not considered a successful design. Still, they proved more reliable than the new 14″ (35.6 cm) of the HMS King George V class.

Rodney’s 16 inches shell being rolled aboard

Rodney’s salvo while training. (warship today 1936)

Loading a shell on HMS Nelson, 1940)

They were built using a tapered inner A tube, two rear locating shoulders and full length taper for the wound wire B tube, and overlapping jacket, and a breech ring. There was also a shrunk collar at the A tube’s rear. A breech bush was used to attach the Welin breech block, operated by an Asbury hydraulic mechanism. The whole 29 guns (18 for completion plus spares) were made at Elswick, Vickers, Beardmore and completed at the Royal Gun Factory.

Specifications (Mark I):

16-in shell bins on HMS Nesons (IWM)

- Gun Length 742.2 in/Bore Length 720.0 in (18.288 m)

- Rifling Length 586.96 in (14.909 m), grooves (80) 0.135 in deep x 0.377 (3.43 x 9.577 mm)

- Lands rifling: 0.2512 in (6.380 mm)

- Twist: Uniform RH 1 in 30

- Chamber Volume: 35,205 in3 (576.9 dm3)

- AP Mark IB 2,048 lbs. (929 kg)

- HE 4a: 2,048 lbs. (929 kg)

- Bursting Charge AP: 51.2 lbs. (23.2 kg) TNT

- Projectile Length AP: 66.23 in (168.2 cm), HE: 75.94 in (192.9 cm)

- Propellant Charge: Initial 498 lbs. (225.9 kg) MD45

- Prop. charge 1930: 495 lbs. (224.5 kg) SC280

- Ammunition stowage per gun: 95 APC and 10 practice rounds

- Weight: 1,480 tons (1,503.7 mt)

- Elevation: -3/+40°

- Rate of Elevation: 10°/second

- Train “A” Turret: +/- 149°

- Train “B” Turret: +/- 165°

- Train “X” Turret: 60-130° both sides, arrest gear

- Rate of Train: 4°/second

- Gun Recoil: 44.6 in (113 cm)

- Loading Angle: +3 degrees

- Rate Of Fire: 1.5 rounds per minute

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,586 fps (788 mps)

- Approximate Barrel Life: 200-250 rounds

- Range AP 40°: 2,586 fps (788 mps): 39,090 yards (35,745 m)

- Range HE 40°: 40,890 yards (37,390 m)

- Min range Armor penetration AP: 15,000 yards (13,716 m) side 14.4″ (366 mm), deck 1.95″ (50 mm)

- Max range Armor penetration AP: 35,000 yards (32,004 m) side 7.6″ (193 mm), deck 6.50″ (165 mm)

- Min Range at 2.3°: 5,000 yards (4,570 m) 2,248 fps (685 mps) 2.5° angle

- Max Range at 40°: 38,000 yards (34,750 m), circa 1,503 fps (458 mps) and 50°+

Three-gun Turrets 1b (Mark I):

Performances (Mark I):

Replacing the 16-in guns in Birkenhead’s yard, February 1942

Secondary: 6″/50 (15.2 cm) BL Mark XXII

Secondary turrets on HMS Rodney

The secondary armament was of course no longer in casemates but in turrets, and a twin model was already tested with success on HMS Enterprise. These were semi-automated turrets, all grouped at the rear. And they were unique to the Nelson class…

The admiralty wanted a more powerful secondary than the usual 6″ Mark XII previous used on the last battleships, and a new model was started by the Royal Ordnance for the “G3” battlecruisers. After the Washington treaty cancellation, the guns and mountings already built were reused on the Nelson class. They had had a high maximum elevation so to engage aircraft, but with the speed of the latter in the 1930s they were only considered for an anti-ship role. Training and elevation speeds never matched this AA role anyway. The arrangement meant all turrets and working spaces were grouped tightly together which was a protection problems, and they were in addition poorly proetcted, being completely outside the citadel and in the “or nothing” area. With 1″ (25 mm) HT plating only a single lucky shell could disable all three turrets on either side.

The 6-in gun crew is resting inside one of the turrets.

The Mark XXII* gun had a A tube, taper wound wire, full-length jacket, breech ring, breech bush screwed in. They used a hand-operated Welin breech block. When relined they became the Mark XXII. The Mark XXII** had no wiring but used an inner A tube. 40 guns built total, including the six experimental Mark XXII**, never installed. These guns remained unique. Next, the British would adopt the 6″/50 (15.2 cm) BL Mark XXIII for their cruisers and 4.5-in dual for their new and modernized, battleships and aircraft carriers.

Amunition storage in peacetime was 100 rounds per gun, but could be booster to Max 150 rounds. CPBC Mark XXVB: 100 lbs. (45.36 kg). Three types were carried: The CPBC (1942) of 112 lbs. (50.8 kg), and HE but little is available in this one. The Propellant Charge was the SC 150 weighting 31 lbs. (14.1 kg). Barrel life was circa 300 rounds before relining. Working Pressure in the barrel was 20 tons/in2 (3,150 kg/cm2).

The turrets were Mark XVIII, weighting 168,000 lbs. (76 tons), mounting allowing an elevation of -5/+60 degrees at 8°/sec., and train at 5°/sec at 100° either side. Gun recoil was 16.5 in (42 cm) inside the turret, and the loading Angle +5 degrees.

Gun Specs

- Gun Length oa: 309.7 in (7.866 m)

- Bore Length: 300 in (7.620 m)

- Rifling Length: 255.6 in (6.491 m)

- Grooves: 36, 0.046 in deep x 0.3759 (1.17 x 9.548 mm)

- Lands: 0.1477 in (3.752 mm)

- Twist: Uniform RH 1 in 30

- Chamber Volume: 1,750 in3 (28.7 dm3)

- Rate Of Fire: 5 rounds per minute 1

- Muzzle Velocity 2,945 fps (898 mps)

- Range/elevation: 2.1 degrees (MV 2,900 fps (884 mps)) 5,000 yards (4,570 m)

- Range/elevation: 22.9°: 20,000 yards (18,290 m)

- Range/elevation: 45°: 25,800 yards (23,590 m)

- Penetration figures unknown.

In combat, these guns were used on Bismarck by Rodney. The planned rate of fire of 7-8 rounds per minute was deflated on trials to best 4 rpm, but some modifications inscreased it slightly to 5. During the Bismack closer fire, 150 salvos, one from each turret starboard with avg. 5 salvos per minute, plus 98 port battery salvoes were fired and when at close range hit ratio was about 100%, 716 rounds CPBC spent total. Read More

DP armament: 4.7″/43 (12 cm) QF Mark VII

QF 4.7 in gun drill on HMS Rodney, Feb. 1943

The 4.7″/43 (12 cm) Mark VII was a fixed-ammunition AAA gun developed in 1918. Only four were made as the war ended. Performance averaged the older 4.7″/40 (12 cm) QF Mark VIII. The 4.7″/40 (12 cm) QF Mark VIII was developed on this base to equip planned the “G3” and “N3” capital ships, in the same role. When cancelled they were mounted on the Nelson class, and converted carriers. This was the largest fixed-ammunition gun ever in the Royal Navy. On the Nelsons, four were located on the main superstructure roof, abaft the funnel and the bridge. The last pair was located on the aft deck, close to the poop, right aft of the superstructure. The gun crew had no protection.

Roughly equivalent but lighter than the USN 5-in/38, they had a 74 lbs. (33.6 kg) fixed (all included with charge) ammunition helping the rate of fire. In evaluation, the rate of fire precisely was lacking. Subsequent improvements aimed at improving it. The Mark VII had a tapered inner A tube and full length wire with jacket and breech ring. The loading system including a horizontal sliding breech mechanism which automatically opened after firing.

Mountings innovated in having a a power rammer for faster firing at high elevations, carried by the loading tray rocking arm. Rounds were in a loading tray, manually pushed over and caught by the rammer. In total “only” 84 were made. The Mark VIII and Mark X were improved versions. The former replaced the Mark VII on the Nelson class at completion. Their actual bore diameter was 4.724″ (12 cm).

The chamber volume for the Mark VIII was 454 in3 (7.44 dm3). The 197 in (5.004 m) long gun weighted 6,636 lbs. (3,010 kg), far less than the Mark VII. The HA Mark XII mount weighted 27,692 lbs. (12,561 kg) and offering a 90° vertical elevation. Elevation and training was 10°/sec. The projectile was either the HE 76 lbs. (34.5 kg) or the SAP of the same weight. Each round measured 44.26 in (11.24 cm). They used four types of propellant charges, notably the light 9.34 lbs. (4.24 kg) MC19and the two SC103 and NF/S 164-048 of 10.19 lbs. (4.63 kg).

4.7 in gun crew in training – IWM

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,457 fps (749 mps)

- Working Pressure: 20.5 tons/in2 (3,230 kg/cm2)

- Approximate Barrel Life: 1,050 – 1,200 rounds

- Ammunition stowage per gun: 175 rounds

- Range at 45°: 16,160 yards (14,780 m)

- AA Ceiling 90°: 32,000 feet (9,750 m)

AA armament:

QF 2-pounder AA practice on HMS Rodney, Oct. 1940

8x 2-pdr/69 pompom (1928):

As completed, the Nelsons had eight single 2 pdr (40 mm/69 (1.6 in)) QF Mk.II AA guns. They were located on the superstructure deck, two at the foot the bridge, either side and forward, and two pairs aft abaft the rear main fire director.

There were in addition four 47mm/40 3pdr Hotchkiss Mk I, used as saluting guns and located over the superstructure deck, right behind the bridge. Since it was considered rather weak, they were beefed up considerably over time. In 1932 and 1934, both received a single octuple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII “pompom”. In 1935, they both received two quadruple 0.5 in Vickers (12.7mm/62) tandem heavy machine guns.

In 1935 and 1937 respectively, both gained a second octuple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII. In 1938, Rodney received a third 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom mount. In August 1940, HMS Nelson received an extra octuple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII (now four mounts) and two quadruple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom and four 20 tubes of 178mm UP AA rockets projectors. Soon after she woulld receive two 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV.

Octuple QF 2-in (40 mm) “pom pom” Bofors (1932-40)

In all four were added, over time, from 1932 to 1941. By January 1945 both received in addition four quadruple US pattern 40mm/56 Bofors Mk 1.2.

20 mm Oerlikon AA guns (1940-45):

Rodney was the first to receive two single 20mm Oerlikon Mk II/IV, in August 1940. Nelson received 13 of them in March 1942 and Rodney 17 by May 1942. By August, this was pushed to 32, and 28 for Nelson by the autumn of 1943.

In 1946, Nelson had four quad 40mm/60 Mk 2, six octuple 40mm/39 Mk VIA, and no less than 65 20mm/70 Mk III, four were removed later, shortly before decommission. Rodney had five quad 40mm/39 Mk VIA pompom, a single quad 40mm/39 Mk VII, five twin 20mm/70 Mk V, and 58 single 20mm/70 Mk III AA guns.

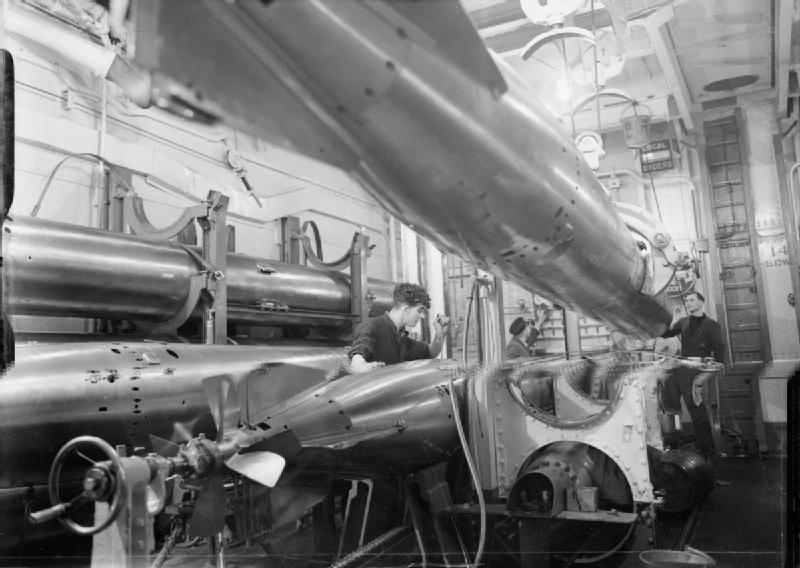

Torpedo armament: 2×1 622 mm (24.5 in) Mk.I

Torpedo room on HMS Rodney – IWM A280

The new model torpedo was planned for the whole concepts serie of battleships and battlecruisers planned in 1920. Yes, Jutland showed these were inefficient, but there was hop to develop a larger, thus, faster and longer range model to off-balance these issues. The 24.5″ (62.2 cm) Mark I were developed from that date, and were evtentually installed on the Nelsons as planned in 1922. Design was finalized in about 1923 and they were in service from 1925.

Weighting 5,700 lbs. (2,585 kg) with an overall Length of 26 ft 7 in (8.103 m), they carried quite a potent 743 lbs. (337 kg) TNT warhead, to a range of 15,000 yards (13,700 m) at 35 knots in the fast setting and up to 20,000 yards (18,300 m) at 30 knots. They were powered by Oxygen-enriched Air propeller. In short, they were the British version of the Japanese “long lance” (Type 93) but the latter were better. Smaller yet capable of 22,000/48–50 knots or 40,400 m/34–36 knots and carrying 490 kg (1080 lb) they really were the world’s best, hands down. The Nelsons were the last battleship class design to carry torpedo tubes. This model never saw service outside the Nelsons and can be seen retrospectively as a waste of time and money.

Anyway, they were allegedly used in action: When firing on KMS Bismarck at much closer range, Rodney fired a 24.5-inch torpedoes from her port-side tube… and claimed a hit. Historian Ludovic Kennedy says that would be the only instance in history a battleship torpedoed another one, however earlier before this happened, the starboard side tube had its sluice door jammed after a near miss from Bismarck. On 27 September 1941, her port torpedo station, clearly a weak point, was hit by an Italian 18-inch aerial torpedo which flooded the compartment behind the torpedo body room, enabling 3,750 tons of seawater to penetrate. After this the admiralty ordered torpedoes and their stations being removed from both battleships at the first occasion.

Fire Control equipment

For the main armament, and the Admiralty Fire Control Table Mk I for surface fire control of the main armament. Two main director-control towers were fitted with 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinders, one mounted above the bridge, the other was at the aft end of the superstructure. The turret themelves had a backup 41-foot (12.5 m) rangefinder on their roof. The general back-up director was placed on the conning tower’s roof, and under an armoured hood.

The secondary armament was controlled by four directors, each with its own 12-foot (3.7 m) rangefinder. A pair was located either side of the main director, on the bridge roof. The two others were placed abreast the aft main director.

-For the AA armament, these ships were fitted with the HACS AA fire control system. They were situated on a tower abaft the main-armament director, served by a 12-ft high-angle rangefinder.

-To control the torpedoes, there were two control directors, each with a 15-ft rangefinder. They were located abreast the funnel.

Other equipments

Nelson in the Mediterranean, interwar.

Among other things, the Nelson’s were given eight projectors for night combat: Two were located forward of the bridge, encased on the structure, and another pair aft of the bridge at the same level. Another pair was located on open platforms either side of the funnel, a bit aft of it, and the last pair, attached to the legs of the main mast aft.

There was a plane in 1932, shortly after commissioned, with hangar located in the space between the bridge and funnel, relatively high. It was servuced by a large lattice crane located on the port side. Four paravanes were stored at the foot of “A” barbette forward on deck, strapped just behind the forward warvebreaker. A second, wider wave breaker was installed on either side of “B” turret. Cables and pole tenders for the Paravanes were stored on deck an in bins close to the barbettes. Three hydraulic chain winches were located forward on the steel beach. There were two anchors on starboard, one to port, none aft.

Thirteen service boats were carried also, some being replaced later by smaller and more compact infatable rubber boats, notably to clear the space and field of dire for extra AA armament. Two diesel-powered cutters for harbour and inter-ship liaison were stored on the quartedeck, at the foot of the tripod mainmast. Either side of these there were two seam cutters and the captain’s yawl. On the deck were located several pinnaces, three on starboard, under vaits, one under davits port (the rest of the deck space was taken by the crane), the remainder being relocated on deck, at the foot of the main conning tower. Two more yawls were located forward of “A” turret.

On board aviation

Supermarine Walrus hoisted onto HMS RODNEY

A small seagull floatplane (ancestor of the Walrus) was stored behind the bridge, serviced by the port crane. However this system was laborious and in 1936, Rodney received a catapult installed on turret “X”, with 1 seaplane. It was apparently first a floatplane version of the Fairey Swordfish and later a Walrus. It seems Rodney had it modernized in 1942 and the seaplane was a Supermarine Walrus, kept until 1944. It seems Nelson never received any.

Radars, FCS and ECM

Nelson entered the war without radar, but Rodney was fitted in 1938 with a type 79Y radar. By 1940 in turn Nelson received the more modern type 281 radar. Her sister received a type 279 radar in addition at the same time. By August 1941, Rodney was fitted with the type 279, the type 271, type 281, and type 284 radars and Nelson in april 1942 had a full set comprising a type 273 radar, five type 282 FCS radars, four type 283, a type 284, and two type 285 radars for fire control. The same year in May, Rodney received the same set.

This electronic coverage was considered acceptable until early 1944 when Nelson received a type 650 ECM suite fitted in June on Rodney prior to the Normandy Landings. There were basically no further changes or addition until the end of the war, and post-war to decommission.

Construction

HMS Nelson (after Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson or course, third ship of this name) was laid down on 28 December 1922 as part of the 1922 Naval Programme. She was built at Armstrong Whitworth’s Low Walker shipyard, North Tyneside, Newcastle upon Tyne. She was launched on 3 September 1925, but nothing was of not in the attendance. After preliminary sea trials, she was commissioned in the Royal Navy on 15 August 1927. Total cost was £7,504,055, unprecedented in the history of the RN for a capital ship, even inflation-adjusted. She made more extensive sea trials, fixes, and eventually was fully accepted for service in November 1927.

HMS Rodney was named for Admiral Lord George Rodney, sixth ship of her name and was laid down in the yard number 904 on 28 December 1922 at Cammell Laird’s shipyard, Birkenhead. She was launched on 17 December 1925, sponsored by Princess Mary, Viscountess Lascelles, a relative of admiral Lord Rodney. However the ceremoney went not according to plan as she failed to brake the bottle of Imperial Burgundy until the third attempt. Nevertheless, HMS Rodney made her priminat and final sea trials and full completion in August to November 1927, to be commissioned in the RN on 7 December with Captain Henry Kitson as first commanding officer (CO). Her cost was £7,617,799 substantially more than her sister. No experience return could be made on her sister are both were built in parralel. It is unclear where came from the 100,000 pounds difference but possible delays.

The peculiarities of the unusual silhouette of this class made it that in 1939 they were nicknamed sarcastically by their crew “Nelsol” and “Rodnol”, in reference to tankers then in use in Britain whicg they loosely resembled and whose name always ended with “ol”. The were also called the “pair of boot”, and the “ugly sisters”. In short, their new design was not of the taste of all officers nor sailors, but soon they started to appreciate her slightly roomier accomodations and more modern features, notably the comfortable bridge.

Author’s illustration of the Rodney in 1942

⚙ Nelson class specifications, 1938. |

|

| Dimensions | 216 m long, 32 m wide, 9.6 m draft (full load) |

| Displacement | 33,950 t. standard, 42,250 t. Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 1,361 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Brown-Curtis turbines, 8 Yarrow boilers, 45,000 hp. |

| Speed | Top speed 23 knots, 5,000 nautical radius at 12 knots. |

| Armament (1938) | 9 x 406mm Mk I (3×3), 12 x 152 mm (6×2) Mk XXIII, 6 x 102 mm Mk VIII AA, 24 x 40 mm AA (3×8), 16 x 12.7 mm Vickers (4×4), 2 x 622 mm TTs sub. |

| Armor | Citadel 355 mm, 160 mm decks, 152 mm rangefinders, 406 mm turrets, 38 mm barbettes, 343 mm CT. |

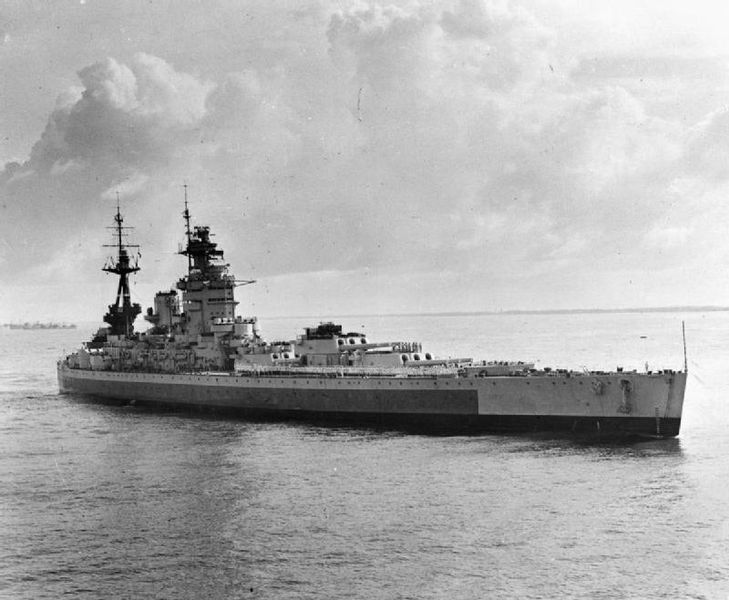

HMS Nelson in 1943 off North Africa flyby photo colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Modifications

HMS Nelson, warship today 1936

HMS Nelson:

-May–June 1930, Nelson: The high-angle directors and rangefinder were replaced by a new circular platform and fitted with the High Angle Control System (HACS) Mk I director.

-March 1934: The old 47 mm Hocthkiss (two-pounder) saluting guns are removed, starboard torpedo director as well, replaced by a single octuple “pom-pom” starboard. Mk I director mounted on the bridge roof.

-1934–1935: First quad Vickers 0.5 in (12.7 mm) abaft the forward superstructure, lattice crane to handle a flying boat (tested). Later the plane was removed.

-1936–1937 portside “pom-pom” and director, gun shields for the 4.7-inch guns, removed March 1938.

Nelson at Spithead, 1937, with her sister ship in the background

-June 1937-January 1938: Main refit, HA director tower reinforced for two pair of HACS Mk III plus non-cemented deck armour at the bottom of the armour belt from the citadel to the bow 4-2.5 in thick.

-January–August 1940: Aft 6-in directors replaced by “pom-pom” plus one on quarterdeck and Type 279 radar. Gun shields back plus 20-tube 7-inch (178 mm) UP rocket launchers on ‘B’-‘C’ turret roofs, crew 1,452.

-October 1941 repairs: Torpedo tubes rooms removed and UPRL replaced by “pom-pom” on ‘B’ plus “pom-pom” directors Mk III, three more installed with Type 282 Gunnery radar and HACS with Type 285.

-September–October 1942 more AA added and extra radars, The 0.5-in Vickers removed

-May–June 1943 additional 20 mm AA guns.

-late 1944 USA refit more 20 mm AA, back-up director replaced by two quad 40 mm Bofors AA and two abaft the funnel. “pom-pom” directors replaced by Mk 51 directors. Displacement 44,054 long tons, 1,650 men.

HMS Rodney:

-March 1930: Similarly to her sister she received first new high-angle directors and rangefinder (High Angle Control System Mk I.

-July 1932 2-pdr+starboard TT director removed, “pom-pom” mount installed plus 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinder, bridge roof.

-1934–1935: Two quad Vickers 0.5 in (12.7 mm) AA, aircraft catapult on ‘X’ turret

-1937: Collapsible crane installed abreast the bridge

-October 1938: Extra “pom-pom” quarterdeck and prototype Type 79Y early-warning radar system on masthead, first battleship so equipped.

-October 1940: Octuple “pom-pom” gunnery training installed, Type 279 radar.

-June–August 1941 Boston NyD refit: quad 2-pdr, 2×8 2-pdr, full radar suite.

-February–May 1942: AA armament heavily reinforced, 17 x 20 mm Oerlikons, Mk III “pom-pom” directors +3 more Mk IIIs, HACS Mk III and masive radar upgrade.

-August–September 1942 Rosyth repairs: Extra 20 mm AA

-May 1943 4.7 in gun shields added, catapult removed, + extra Oerlikons 20 mm in single and twin mounts, 67 in all

-January–March 1944: Type 650 radio jammer, final displacement 43,100 long tons, 1,631–1,650 men crew in 1945.

Links/sources

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Admiralty Historical Section (2007). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean Convoys: A Naval Staff History. Whitehall History Publishing

Ballantyne, Iain (2008). H.M.S. Rodney. Ships of the Royal Navy. Pen and Sword.

Bell, Christopher M. (2003). “The Invergordon Mutiny, 1931”. Frank Cass.

Brown, David K. (1987). Lambert, Andrew (ed.). “Ship Trials”. Warship (44): 242–248.

Brown, Robert & Brown, Les (2015). Rodney and Nelson. Shipcraft. Vol. 23. Seaforth Publishing.

Burt, R. A. (2012). British Battleships, 1919–1939 (2nd ed.). Annapolis NIP

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006). Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy. Chatham Publishing

Haarr, Geirr H. (2013). The Gathering Storm: The Naval War in Northern Europe September 1939 – April 1940. Annapolis NIP

Jordan, John (2020). “Warship Notes: The 6in Turrets of Nelson and Rodney”. Warship 2020. Osprey.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament. NIP

Raven, Alan & Roberts, John (1976). British Battleships of World War Two: Development and Technical History. NIP

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. NIP

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Links

Nelson on maritimequest.com

Rodney on maritimequest.com

ww.battleships-cruisers.co.uk

On navypedia.org

CC photos

Nelson class battleships wiki

N3 class battleships wiki

Pathé Gazette Footage

Model Kits

Both inspired manufacturers for decades for sure, notably because of the Bismarck’s battle and their extensive career as well as their odd look. This started with a gargantuan 1:128 hull modelled by Fleetscale. Still in large scales, Trumpeter made both in 1:200, and in the more manageable 1:350; as Iron Shipwrights. JSC made a unique 1:400 and Airfix an 1:600, while the 1:700 had been well covered by Tamiya, and Trumpeter again. Many 1:350 and 1:200 accessories exists, like photo-etched parts. 3D models in small scale also exist as isolated parts at large scales.

General Query on scalemates

Review of the gargantuan 1/200 Nelson firing in .modellmarine.de

The British Battleship HMS NELSON 1940/41 Profile Morskie Nr. 127, Sławomir Brzeziński

Nelson and Rodney in action

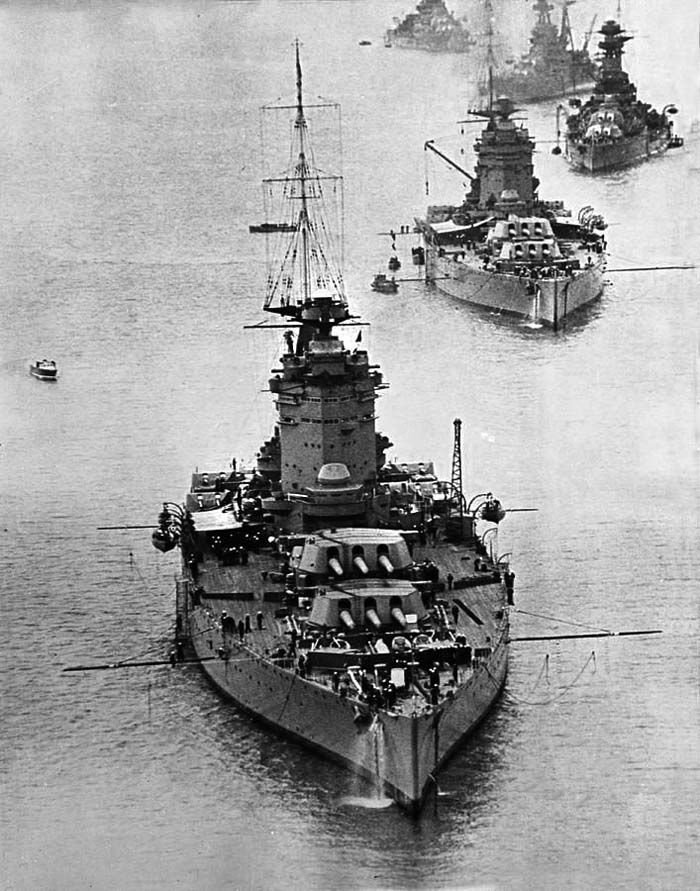

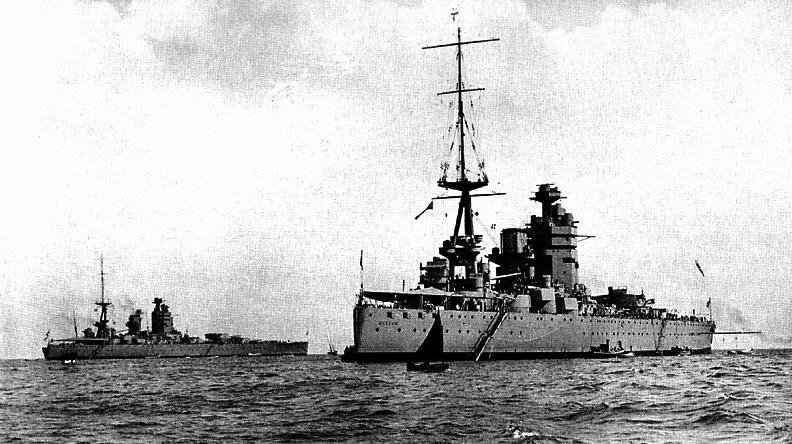

Nelson and Rodney together before the war in Scapa Flow

The career of both battleships is quite a good example of what mostly differs for capital ships between the first and second world war: Of the two, only Rodney had an actual encounter against another capital ship, Bismarck. Although Bismarck was not yet crippled when engaging the battle, her damage was minimal, showing her protection worth, but also that her powerful guns could compromise her decks and hull when firing at unusually low-angle. Her accuracy was average, and historians are still divided about if she manage to inflict comparatively more damage than King Georges V, which fired faster, earlier, and longer, but with much smaller caliber shells. As we know after Cameron’s famous expdition on the wreck crossed with several testimonies, Bismarck was likely scuttled, not even receiving the coup de grace after several torpedo hit and storm of steel.

The rest of the career of both battleships, sometimes operating together and sometimes alone, was spent mostly in convoy escort. In the Home fleet, their slow speed disqualified them as “active first line”, as the five King Georges V class vessels, capable of 28 knots, versus 21. Outside these, like most battleships of WW2 when the naval threat of both the Kriegsmarine and Regia Marina has been eliminated, was to provide shore bombardment and on demand inland gunfire. On this chapter, their accuracy not seems particularly stellar, although the few on-ton 16-in shell that landed on Wehrmacht and SS units in normandy for example would not agree. All in all, both served in various theaters, but always stayed close from home: North sea, Atlantic, and Mediterranean.

Plagued by steering and manoeuvrability issues, which narrowly caused the loss of Rodney in a critical air attack, both showed good damage resilience nevertheless, never repaired for very extensive damage. But luck also partly counted in it… Were these mocked battleships, dubbed of many names, were a taxpayer’s bargain ?

Although compromised by treaty limits (which also limited their cost to some extent) they served for almost 18 years and during WW2 jumped to one role to another with not that long inavailability periods, making the most of their active service and spending as many times rounds as to replace all their barrels mid-life. They deterred and repelled many air and sea attacks, helped many convoys, protected all significant western amphibious operations of WW2, finished off the Bismarck, and helped allies boots on the ground in Normandy so to really make their worth until there was little left to do on the European theater.

HMS Nelson

HMS Nelson

Nelson in 1933

Nelson’s trials were stopped in order that she could be commissioned in the RN, and resumed afterwards in October 1927, for a service start on 21 October, as flagship, Atlantic Fleet (1932: Home Fleet) her main affectation until 1 April 1941. Prince George, Duke of Kent served aboard as lieutenant for the Admiral’s staff until 1928. By April she hosted King Amanullah of Afghanistan while off Portland. After 1926 and 1930 went by without incident, on 29 March 1931 she collided with SS West Wales under foggy conditions off Cape Gilano in Spain. Damage was light however as they mostly scraped each other hulls sideways. Repairs were over by July but in September her crew took part in the widespread Invergordon Mutiny, refusing to sail for an exercise.

Nelson in 1934

On 12 January 1934, she ran aground on Hamilton’s shoal off Southsea before starting her spring cruise in the West Indies, which was postponed. She floated off during the next high tide and at the time the incident report blamed her poor handling at low speed. She was famously present at the King George V’s Silver Jubilee Fleet Review in Spithead by July 1935, and his Coronation Fleet Review by May 1937. 1936 was septn withouit noticeable. She started her first major refit in 1937 after which she sailed to Portugal and stopped in Lisbon where she could be admired by the population together with her sister Rodney, in February 1938.

HMS Nelson in her dark prewar livery, 1937.

Nelson at Spithead’s review, 1937

Between patrols and escorts – Sept. 1939 – May 1941

In the firth of forth, September 1940

When WW2 broke out, Nelson with the Home Fleet started patrols in the “northern gap”, in the waters between Iceland, Norway and Scotland. It was a double blockage, for the incoming blockade runners and ships returning home. She was patrolling off the Norwegian coast on 6–10 September and twenty days later helped to cover a salvage and rescue operation of HMS Spearfish. In August she escorted her first convoy for iron ore from Narvik. On 30 October, she was ambushed and torpedoed by U-56 near the Orkney Islands, two (of three) hitting but failing to explode from 870 yards (800 m) only.

After the AMC Rawalpindi was sunk off Iceland on 23 November, Nelson and Rodney took part in the chase to try to cacth the two Scharnrhost class, in vain. On 4 December 1939, she hit a magnetic mine previously laid by U-31 close to the entrance to Loch Ewe, Scotland. The blast (which injured 74 sailors) cut a 10×6 feet (3.0 by 1.8 m) gash forward of ‘A’ turret under the waterline and flooding was severe, starting from the torpedo room, later defined a s weak point. This retired her for all operations for drydock repairs in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth. This was over in August 1940.

In September, teaming with her sister and HMS Hood she was sent to Rosyth to block a possible sea invasion, whuch never materialized as the air campaign developed over Britain. Jervis Bay signalled an attacj by by Admiral Scheer on 5 November prompting the departure of Nelson and Rodney to try to vut her way backp between Iceland and the Faroe, but the Gemran cruiser instead chosed wisely the South Atlantic way. Later the admiralty learned about the sortie of Gneisenau and Scharnhorst for a commerce raiding campaign and Nelson, Rodney and HMS Renown were sent at sea on 25 January 1941 to take positions south of Iceland, a probable interception course. However the Germans spotted british cruisers on 28 January and turned away.

Nelson was a private ship on 1 April, escorting Convoy WS.7 to South Africa and stopped for the first time in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Back home she escorted the convoy back with HMS Eagle when the latter failed to spot the Hilfskreuzer KMS Atlantis 7,700 yards away in the night 18 May while in the South Atlantic. A lost occasion for Nelson to send her ad patres.

Hunting the Bismarck

After the Battle of the Denmark Strait on 24 May, KMS Bismarck was spotted rushing towards France. Alreasdy all the RN in the area was in hot pursuit including her sister, but nevertheless, Nelson and Eagle faraway, were still called for help while they were still north of Freetown. They of course never get there in time. In between Bismarck, struck on her rudder by a Swordfish, was left circling until catch by her sister and HMS King Geoarges V, pounded into submission and sunk. On 1 June, Nelson was reassigned to protect the Convoy SL.75 back home. The German supply ship Gonzenheim, escaping the AMC Esperance Bay on 4 June, her pisition was transmitted and the admiralty ordered Nelson to rush forward and intercept her. But she was scuttled as soon as spotting Nelson coming for her.

Mediterranean service

South African sailors posing on a 16-in gun as part of Nelson’s crew, 1941

On 11 July 1941, Nelson was ordered to cover the Convoy WS.9C, an early convoy to Malta. Away from Gibraltar, the powerful escorting force was called “Force X”, reinforced by Force H on its way. There were far more escort ships than merchantmen, but the danger was real and correctly evaluated. The night and morning of 22-23 July Italian air attacks commenced. Nelson was not engaged and eventually joined Force H and resume her trip to to Malta. Force X cruisers arrived two days later. Force X/H was back to Gibraltar on 27 July.

On 31 July–4 August, Force H covered another of such convoys, Operation Style. Force H CiC, VADM James Somerville made Nelson his flagship on 8 August. This way, the battleship also took part in Operation Mincemeat, escorting a minelayer to Livorno, Ark Royal’s air group pounding Northern Sardinia meanwhile. On 13 September, she was steaming with Force H’s Ark Royal and Furious, tod deliver by flying off 45 Hurricane to Malta.

Nelson also took part in Operation Halberd to Malta from 24 September, while Somerville transferred his flag to Rodney. Nelson and destroyers departed Gibraltar later as backup. Force H was renunited with Nelson during the night and on the morning they were spotted and attacked by Regia Aeronautica’s SM.79 and 84. One of the latter managed to score a hit on Nelson: The 18-in torpedo dropped from 450 yards (410 m) found its mark: A 30×15 foot (9.1 by 4.6 m) gash was blown into the bow, and again some flooding came from the blasted torpedo compartment, fortunatly without casualties. Her bow plunged 2.4 m down, and she dropped to 12 kts as a measure to reduce water pressure on her bulkheads. Staying with the fleet offered a potent AA umbrella and she suffered no more attacks. Emergency repairs were made in Gibraltar completed in Rosyth until May 1942.

Operation Pedestal

Nelson opening fire during post-refit trials in May 1942. It was feared that with the structural weakness of these ships made impossible a full volley, but it was debunked when Rodney fired volley after volley on KMS Bismarck, altghough there was some damage to the forward decks and hull when firing at low angle.

Nelson was assigned to the Eastern Fleet after repairs, refit, sea trials, and short refresher cruise until 31 May. She escorteed Convoy WS.19P Clyde-Freetown (South Africa) and convoy WS.19PF to Durban. On 26 June the admiralty called her to take part in the powerful fleet committed for escort in Operation Pedestal to Malta. She was back in Scapa Flow to prepare in July, and became flagship, VADM Edward Syfret at the head of the operation.

HMS Nelson off La Valette, Malta, North African Campaign, November 1942

She left the Clyde on 3 August, training en route to Gribraltar, passing the Strait on 9/10 August. She joined the convoy in the morning and the convoy was underway when the first combined Axis attack started on the 11 August? Firce attacks saw the sinking of HMS Eagle by an U-Boat. Nelson remained unscaved all this time and damaged but did not report a down aicraft. Capital ships then gathered off the Skerki Banks (between Sicily and Tunisia) on the 12th and she heded back top Gibraltar and Scapa Flow.

Operation Torch

Nelson for Operation Torch, Nov. 1942, in front of Mers-el-Kebir naval base

Next, she was reassigned to Force H in October 1942. Now the mission was to support the allied landings in French North Africa. The fleet departed on the 30th arriving in Gibraltar on 6 November. and on the 8th, arrived insight of her objectives. As a battleship she was to provide a deterrence against any intervention of the Regia Marina during the landings, and possible provide gunnery support later. VADM Syfret (Force H) made his flagshp and Operation CO on Nelson from 15 November. Force H first covered a British troop convoy from Gibraltar to Algiers by January 1943 but Syfret moved his flag to King George V by May 1943, Nelson returned to Scapa for shore bombardment training in order to participate next to Operation Husky.

Italian Campaign: Op. Husky, Baytown & Avalanche

HMS Nelson firing in April 1943, seen from HMS Rodney in the Western Mediterranean

Nelson departed Scapa on 17 June 1943, arriving at Gibraltar on the 23rd, and on 9 July, teamed with her sister and HMS Indomitable to meet in the Gulf of Sirte with Warspite, Valiant Formidable from Alexandria as a large covering force. Nelson patrolled the Ionian Sea to deter the Regia Marina from intervening.

Nelson in April 1943, seen from Rodney.

On 31 August, both sister ships were sent on the Italian shore, shelling to submission Italian coastal artillery between Reggio Calabria and Pessaro. This was part of Operation Baytown, the invasion of Calabria on mainland Italy. Netx followed the landings at Salerno, Operation Avalanche, on 9 September 1943, Nelson aerial “barrage” being used with success to deter Luftwaffe’s attack. The Italian armistice was in fact later signed aboard HMS Nelson, between General Dwight Eisenhower and Marshal Pietro Badoglio, on 29 September.

D-Day Operations

Rodney firingon Caen during Operation Overlord, June 1944.

Nelson went back through Gibraltar on 31 October 1943, bound for home. There, she trained and was prepared for the next big operation, again to provide coastal gunnery ast part of the Home Fleet in Scapa. The goal was to eachieve greater accuracy and master close cooperation air and land spotting, for the remainder of 1943 and the first six months of 1944, with a refit in between. On D-Day, she provided naval gunfire support. But as she retired home for resupplying, she hit two mines in the channel on the 18th. They caused considerable damage but no casualty. Her ASW compartimentation held firm and she could be able to limp home. First repairs were done in Portsmouth, but as British yards were at full capacity, the plan was to send her to the US, to benefit from Philadelphia Naval Shipyard’s full drydock repairs. She arrived there on 22 June 1944, and was only back in Britain by January 1945.

With the eastern fleet

Nelson in the East Indies, 1944

At the time, the war in Europe was practically over and she was instead prepared to join the British Eastern Fleet (later Pacific Fleet). She departed for Gibraltar, crossed the Suez canal and entered the Indian Ocean, stopping in Colombo, Ceylon, for resupplying on 9 July. She became fleet flagship but stayed off the western coast of the Malaysia for three months, for Operation Livery. For the remainder she had little occasions to fight, and spent her weeks and months here as floating HQ basically. Japanese forces eventually surrendered also aboard Nelson at George Town, Penang, on 2 September 1945. She was present in Singapore for the general South-east Asia Japanese forces surrendering ceremonies.

General view aboard HMS NELSON on the occasion of the visit of the ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association) show “Spring Party” whilst the ship was at Gibraltar. The deck and 16 inch gun turrets are crowded with sailors watching the show, the performers are out of sight. The show starred Beatrice Lillie, Leslie Henson and Vivien Leigh.

Pay day on HMS Nelson, above are the 16-inch guns of X (rear) turret, pointed forward at B (middle) turret’s barbette.

Postwar fate

Stern view, 1944

On 20 September she was relieved as flagship and ordered back home, departing on 13 October and arriving in Portsmouth on 17 November. She became again flagship, this tome for the Home Fleet, later replaced by King George V on 9 April 1946. She had by then a more peaceful training carrer this summer, with Training Squadron (created on 14 August), and as flagship. Relieved by HMS Anson in October 1946, she became again a private ship but was damaged by collision with the submersible HMS Sceptre in Portland (15 April 1947), after which she was paced in reserve from 20 October, in Rosyth. Written off on 19 May 1948 she awaited her fate. From 4 June to 23 September she ended as a target ship to test the latest 2,000 Ibs (910 kg) AP aerial bombs. Surving these, she was sold to the British Iron & Steel Corporation, on 5 January 1949, and then sent to Thos. W. Ward for scrapping in Inverkeithing, starting on 15 March.

Nelson in 1945

HMS Rodney

HMS Rodney

HMS Rodney after refit in Liverpool

Early Years 1928-1939

Rodney (after the seven years’ war Admiral Lord George Rodney and 6th of the name) was completed and resumed trials after commission under captain Kitson, then entered service on 28 March 1928, assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron, Atlantic Fleet and later Home Fleet from March 1932, remaining there until 1941. On 21 April Captain Francis Tottenham took command as she was training at Invergordon, Scotland in her first annual exercises. She became briefly Royal Guardship at the Cowes Week, hosting King George V and Queen Mary thus summer. She visited HM Dockyard in Devonport to be visited by the public and generate fund-raising in the Navy Week. She had her first overhault in Glasgow’s Gladstone Dock by October.

In 1929 she was part in the historical manoeuvers combining the Atlantic and Mediterranean Fleets. While visiting Torquay in the Devon she was despetached to carry assistance to two submarines colliding off Milford Haven, arriving at Pembroke Dock to load rescue and salvage equipment but was delayed by bad weather and arrived too late to find any survivors after H47 had been underwater for more than 48h. Rodney’s troublesime machinery was examined in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth and by late September she had a refit. While in drydock she received her new commander, Captain Andrew Cunningham by December.

In June 1930 she visited Portrush in Northern Ireland and Cunningham was replaced by Captain Roger Bellairs on 16 December. By mid-September 1931 he crew took part in the Invergordon Mutiny, badly managed by Bellairs relieved by Captain John Tovey by order of the admiralty on 12 April 1932. She would ran aground while leaving Portsmouth, in January 1934, without damage. She became flagship, Admiral Lord William Boyle, Home Fleet and proceeded for her winter cruise to the British West Indies, meeting the US Navy. At her returned she visited two Norwegian ports. Captain Wilfred Custance took command on 31 August and after her 1935 winter cruise she transited from the Azores to Gibraltar in Jan-March and was back to participate in King George V’s Silver Jubilee Fleet Review, Spithead on 16 July, and again Royal Guardship at the Cowes Week. Under Captain William Whitworth from February 1936, and then Ronald Halifax she partipated in the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead on 20 May 1937.

After being temporary fleet flagship under Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse and her refit she toured Norway in the summer and by 1938 she teamed with Nelson to visit Lisbon in Portugal, adding her weight to the neutrality fleet surveying the Spenish Civil War. Captain Edward Syfret took command in August, and after her short refit in September and post-refit trials in January 1939 she hosted RADM Lancelot Holland as flagship, 2nd Battle Squadron. She fired a 21-gun salute in honour of the French President Albert Lebrun’s arrival in Dover for state talks as war seemed close. She was back in Scapa Flow as tensions grew hot in August but steering problems had her sent to Rosyth for repairs. She therefore was not available when WW2 broke up.

Early War Operations 1939-41

HMS Punjabi and Rodney’s 3-in AA in 1940

The Home Fleet spread to patrol possible entries back and from North Atlantic and the nort sea, hunting down all possible German vessels and blockade runners. She patrolled between Iceland, Norway and Scotland and the Norwegian coast. She received orders to assist the submersible HMS Spearfish, depht-charged on the 24 of September while off Heligoland Bight. Two destroyers arrrived earlier, Rodney being a backup while they escorted her home. On their way, the quatuor was attacked by five Luftwaffe’s I./KG 30 bombers, spotted in advance by Rodney’s radar, so their their AA reception was fierce, repelling the attack. She later was part of the covering force for the iron ore convoy from Narvik in Norway.

Captain Frederick Dalrymple-Hamilton took command on 21 November and after receiving news of the loss of MAC Rawalpindi off Iceland, Rodney was sent to search for the German “terrible sisters”, in vain. Bad weather also contributed to the escape of the German fast battleships. Still plagued by rudder problems later, Rodney was sent to Liverpool for repairs until 31 December. Nelson hit a mine on 4 December, so Rodney became replacement, temporary fleet flagship. January-February 1940 saw her at anchor between escorts or commerce raiders patrols. On 21 February’s sortie, in heavy weather, her steering problems had her again returning with propeller’s steering along to Greenock for a fix. While there, she was visited by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth and later PM Winston Churchill, while she left port for Scapa Flow on 7-8 March. While there, she was near-missed during an air attack on 16 March.

Rodney in the firth of forth, 1940

Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, Home fleet CiC, knowing the RAF attacked north-bound German warships in the North Sea, on 7 April, ordered the fleet out in the evening and Rodney while underway off Norway was attacked by the Luftwaffe and hit by a 500 kgs (1,102 lb) bomb, on 9 April, on the corner of a 4.7-inch ready ammunition box, upper deck, aft of the funnel. Shrapnel went through several decks but ended on the 4-inch armoured deck. The small fire started in the galley was quickly mastered by the event made three wounded and fifteen electronicuted (not fatally) when water sprayed met the junction box. Temporary repairs allowed the ship to perform her mission and being back to Scapa Flow. Again, German presence signalled in the Norwegian Sea on 9 June had Rodney rushed to protect a troop convoy. This time for the evacuation of British troops.

Rodney resupplied at sea

Back in dockyard on 24 July as flagship, Rodney was transferred to Rosyth by late August ready in case of an invasion fleet in the English Channel (as part of Operation Sealion), which never materialized. After being back to Scapa she started new escort missions, notably huuting KMS Admiral Scheer which just sank the AMC Jervis Bay. With Nelson she was deployed on the Iceland–Faeroes gap, but missed Scheer. Rodney next escorted the Convoy HX 93 from Halifax to home. She weathered a strong storm on 6-8 December causing hull plating leaks. After repairs and hull reinforcement in Rosyth by December; she was made ready for another rounds of Atlantic operations.

Rodney’s Atlantic service

Rodney’s sailors scrubbling her deck

After her refit, on 13 January 1941, she was sent to search for the KMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and later escorted Convoy HX 108 on 12-23 February. On 16 March while escorting Convoy HX 114 she spotted Gneisenau, rescuing survivors from Chilean Reefer. Rodney appeared over the horizon, while Gneisenau was partially hidden behind the burning merchant ship, at 15 or 16 nmi, limit for Rodney’s guns. Captain Dalyrmple-Hamilton estimated it was too late to engage and chased Gneisenau, while the latter turned away and fled at 31 knots. Next, Rodney escorted Troop Convoy TC 10 from Halifax (10 April) but as the voyage ended, while in the River Clyde on 19 April hse porr manoeuvrability at low speed showed again as she accidentally rammed and sank the trawler Topaze.

Rodney versus Bismarck

Rodney firing on Bismarck, 27 May 1941

Probably the most famous episode of her Atlantic campaign and as a battleship, was her encounter with the latest battleship Bismarck, which despite having an paper a weaker armament, was far larger at 50,000 versus 35,000 tonnes. On 22 May 1941, Rodney and four destroyers escorted the MV Britannic to Halifax and was schedule to join Boston for an overhaul and refit, British Yards being at full capacity. She notably carried all the spares necessary, including new boiler tubes, three octuple “pom-pom” mounts, three or four crates of the Elgin Marbles and 521 military passengers for Halifax and an American assistant naval attaché with important documents back to the US.

Receiving news of the Battle of Denmark Strait of 24 May, Rodney was ordered to take part in the pursuit, leaving HMS Eskimo alone escorting Britannic. She rushed towards the Bismarck with her own escort, HMS Somali, Mashona and Tartar. HMS Suffolk lost radar contact but Dalrymple-Hamilton decided the most probable course of the German battleship was the port of Brest. He set course and ordered the machinery officer ro push the machinery red hot, risking damage, but eventually reaching 22 knots, although this caused as expected mechanical failures along the way.

Admiral Sir John Tovey aboard HMS King George V ordered all incoming vessels to head north west after a misinterpreted signal from the Admiralty. Rodney’s captain though he coould not met the gathering point due to his slow speed and instead disregarded the order, maintaining course for Brest. The Admiralty then confirmed Captain Dalrymple-Hamilton’s assumption and confirmed his course, with Saint Nazaire as another probable destination. Course was altered further south east, in order to even block an access to Spanish ports. This was countermanded by the Admiralty and she was ordered to head north east, but not before steaming south east for several hours. In fact, Bismarck passed him just under the horizon, 25 nmi (46 km; 29 mi) away. But his radar was unable to spot the Bismarck at the time, and until 21:00, her turn south-east for Brest.

Meanwhile, a RAF Catalina spotted and confiormed Bismarck’s position, so that the admiraty coordinated all incoming ship, including Rodney. In between, Tovey had realised his mistake and changed course, but too late. Ther German giant was about to reach a safe position off the coast of France, covered by the Luftwaffe. But Ark Royal’s Swordfish torpedo bombers braved the heavy weather, reached Sheffield and attacked her by mistake, and later launched another last-chance dusk attack on the battleship. Despite fierce AA fire, a single plane manage to hit Bismarck’s stern, disabling her steering. HMS Mashona and Somali left Rodney to refuel and the latter eventually met and followed King George V. Instead of attacking by night, knowing his ships were starving of fuel, he decided to radically reduce speed until dawn, now it was known Bismarck was circling.

Rodney spotted Bismarck at 08:44, 27 May, and the battle comenced, but King George V fired first from 23,400 yd (21,400 m), Bismarck replying at 08:49. Rodney straddled Bismarck with her third salvo, making two hits on her fourth salovo. Bismarck had her forward superfiring turret disabled as the lower turret and her bridge crippled. Rodney took two hits with with shell splinters but no significant damage. Rodney then placed herself in a way to bring ‘X’ turret to bear, but doing so she exposed her profile to Bismarck’s aft turrets. But their salvo missed. The range fell enough for Rodney, allegedly, to fire torpedoes. The starboard tube jammed due to near-misses. Bismarck lower aft gun turret was disabled, in fire and evacuated while Rodney, King George V combined fire with the freshly arrived Norfolk and Dorsetshire. Soon the German griant all her last remaining main turret and was down to her secondaries. Eventually Rodney went on at point-blank range for the finish. She fired several broadsides in flat trajectory and fired three more torpedoes down to 3,000 yd (2,700 m). One allegedly struck Bismarck.

In all, she spent on 378 main shells, 706 secondaries. Captain Dalrymple-Hamilton ordered cease fire at 10:16 and Dorsetshire was ordered to finish her with torpedoes. Rodney however due to the low angle fire had destroyed deck plates around the main-gun turrets: The blast depressed them downwards, and structural members cracked and buckled with all piping below deck broken, rivets and bolts loosened in the hull plating, causing leaks and flooding. Vibrations also caused one gun in ‘A’ turret to broke down and two in ‘B’ turret… Bismarck caused less damage by herself.

Rodney being short on fuel, altered course home the shortest way, by the channel, being attacked by the Luftwaffe on her way, without damage. She resupplied at Greenock and refuelled on 29 May, then resumed her interrupted voyage to Halifax, arriving on 4 June with Windsor Castle. Then she proceeded to Boston Navy Yard for this time more extensive repairs, and refit. During the long drydock time, Captain James Rivett-Carnac took command. Next, Rodney made her post-refit trials in Bermuda by 20 August.

Rodney’s short Force H service (1941)

After a short refrsher cruise, and taking supplies and fuel, she headed east, to Gibraltar, arriving on 24 September. Her atlantic service, started in 1928, ended as she joined Force H, Western Med Fleet. She left Gibraltar to join Nelson escorting a convoy to Malta, Operation Halberd. She shot down by accident a misidentified Fairey Fulmar. Nelson meanwhile was torpedoed along the way, the fleet repelling several axis air attacks. On 28 September 1941, Neslon folded, followed by Rodney and Prince of Wales. VADM James Somerville transferred his flag to Rodney on 30 September and she escorted later two carriers taxiing aircraft to Malta on 16-19 October. On 30 October she was called to replace Prince of Wales, sent to the Far east to guard the fleet against a possible sortie of KMS Tirpitz, just operational.

Back to escort duties (1942)

Colorized photo by Irootoko JR, May 1942

She departed on 2 November for Loch Ewe, Scotland, loaded supplies and headed for Hvalfjord, Iceland, taking her position on the northernmost gap on 12 November. Where anchored there she was visited by world star Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., stationed aboard an American battleship. Rodney was back to Scapa in late December and returned to Hvalfjord by mid-January 1942. She was used as a mock target ship for USAAF pilots; Then she was ordered to Birkenhead for a refit by February, completed in Liverpool until 5 May.

The sisters, reunited in Scapa, sortied to escort Convoy WS 19 bound for Egypt and Burma, departing on 4 June. Both vessel turned back off Portuguese Angola, on the 26th. Rodney’s steering issues resurfaced again, and she reached Freetown, Sierra Leone for repairs on 1-17 July, later departing for home, with further steering problems until reaching Scapa on the 26th. After having a boilers overhaul with help from Rosyth Dockyard, much work was spent on her steering gear. She left Scapa on 2 August to escort Convoy WS 21S bound for Malta Operation Pedestal. This meant she resumer her Mediterranean servicen but detached, not part of Force H but Force Z.

Rodney during Operation Pedestal