HMS Ark Royal (1937)

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier (1935-41)

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier (1935-41)

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classThe large British fleet aircraft carrier

HMS Ark Royal in all her majesty in 1939 – colorized by irootoko jr.

HMS Ark Royal was designed in 1934 to both fit Washington Naval Treaty aircraft carrier tonnage limits and carry a large air group, at least twice than the only other British aircraft carrier designed as such from the ground up, HMS Hermes. About 15 years of aviation technology and doctrine advances separated them. HMS Ark Royal innovated in many ways, starting with hangars and flight deck now an integral part of the hull, and having two hangar deck levels to carry the largest number of aircraft possible, to 1935 standard. She was also the last unarmoured British carrier before the introduction of the superlative Illustrious class.

Due to her large air group she helped developing several carrier tactics before the war which were put to good use.

She served in some of the most active naval theatres of the Second World War and was involved in both the first aerial and U-boat kills and operations in Norway, the hunt for Bismarck, and the perilous Malta Convoys. There, she was repeatedly targeted by axis aviation and rapidly gained a reputation as a ‘lucky ship’. Until chance turned, as she was torpedoed on 13 November 1941 by U-81. Her great buoyancy save her crew. Her safety features should have saved her, leading to an investigation in spite of the crew efforts to save their ship. They eventually showed design flaws, helping to rectify those on subsequent British carrier designs.

As a name, “Ark Royal” is perhaps the most famous in the Royal Navy. It was carried by ships going back to Elizabethan war Galleons (“Ark Raleigh”) – the “royal vessel”, and was carried by one more aircraft carrier before and two afterwards, R09 (launched 1950) and R07, of the invincible class. The tradition was broken by the last two, named Queen Elisabeth and Prince of Wales, which arguably are equally suited for these massive capital ships to honor the Royal family. In service, the WW2 carrier had the pennant 91 and her motto was an old Norman proverb, Desire n’a pas Repos – “Zeal Does Not Rest”.

Design Development history

In 1934, the British Royal Navy fleet air arm rested on a collage of rebuilt vessels not always best fitted to their task, as aviation technology and carrier doctrine progressed. Only a single one, HMS Hermes, was designed from scratch, but based on WW1 experience, on a small hull and for a small air group. HMS Argus was a former liner, HMS Eagle a former battleship, HMS Furious, Courageous and Glorious, ex-Battlecruisers, also from WWI. The Navy could still “burn” remaining tonnage and therefore chose to create a prototype large fleet carrier with all the lessons learnt rather than several small fleet carriers like the Furious, but updated. Standard tonnage indeed needed to reach 23,000 tonnes at the most. The London treaty still not entered discussions.

In 1923, already, so after Hermes was in service, the Admiralty prepared a 10-year building programme including a single aircraft carrier and 300 aircraft for the Fleet Air Arm. The economic situation after 1929 postponed it. In 1930, still, the Director of Naval Construction Sir Arthur Johns, update the 1924 plans and incorporated all the latest technologies. He proposed to the admiralty a new design carrying far more aircraft by using a shortened landing and take-off deck, using at both ends, an arrestor gear and compressed steam catapults. The deck space saved helping to store more ready aircraft on deck, and allowing to prepare them as well. The inclusion of two hangar decks helped secured space for 72 aircraft, something until then unheard of, but soon relativized by the introduction of larger and heavier aircraft during her construction. In reality, this went down to about 60 at best. Later the design was refined, her landing deck was strengthened, hangars fully enclosed into the hull contrary to previous designs which just stacked the hangar above the old deck, and some machinery belt armour. For the first time also she carried three lifts. She also comprised a large island superstructure. Since Argus and Hermes, air flow disturbance was better understood, and an island presented many advantages, notably to control deck operation, and place a fire control system among others.

The international situation started to deteriorate from 1933, between Germany’s rearmament, Japanese and Italian aggressive stance and defiance towards the league of nations. This convinced the British Government to free funds for the planned and postponed carrier, this time written down in the 1934 budget proposals. Plans were completed by November 1934. A Tendered for proposal was submitted in February 1935. Cammell Laird and Company Ltd. obtained the contract after calculating an overall hull cost of £1,496,250 (today £104,630,000) whereas the outsourced main machinery (Parsons and admiralty) was approximately costing £500,000 (now circa £30,000,000) for £3 million total, making the new vessel the most expensive ship -outside battleships- ever ordered by the Royal Navy. Construction started on Job No. 1012, and HMS Ark Royal’s keel was laid down on 16 September 1935.

The Washington and London Naval treaties tonnage restrictions were to expire at the end of 1936. There was already a potential naval arms race developing between Britain, Japan and Italy, and the Government obtained the signing of a second treaty limiting aircraft carrier displacement to 23,000 long tons (23,000 t). Since HMS Ark Royal was planned at that time, her design was revised to fit this anticipated tonnage. This triggered a serie of weight savings which shaped her final design.

Ark Royal after launch, pending completion

Armour protection

One of the crucial point of her design was to offer her a substantial protection while sticking to the treaty limits. To keep her weight down, armour plating was limited to the belt and over the sensitive engine rooms and magazines. For construction, welding was chosen instead of rivetting, but only on 65% of the hull. Nevertheless, this saved 500 long tons. An armoured flight deck was technically possible, but dropped because of the treaty limit, as well as reducing stability and endurance. Instead she had a three-layered side protection system. A void-liquid-void scheme behind the belt was chose, very similar to the King George V-class own scheme. It was designed to resist a 750-pound (340 kg) warhead torpedo. Obviously it was not enough.

HMS Ark Royal also innovated by her fully enclosed hangar design, a first. Although she was still not a true “armoured carrier”, soon to be a British speciality, engineers gave her a ‘strength deck’ plated with .75in (19mm) thick Ducol steel plating. At least it supported rough landings of heavy planes, but not bombs, albeit light. The two hangar decks enclosed within the hull girder gave unmatched rigidity, also allowing to serve aircraft by heavy weather and make a splinter protection. The first and second hangar deck were not protected however. Below deck, machinery spaces flanks were protected by 4.5-inch (11.4 cm) of belt armour. There was also a waterline armoured deck to “enclose the box”, 3.5 in thick (8.9 cm) over the boiler rooms and magazines. Compartmentation helped to mitigate the effect of a torpedo hit, but bulkheads were thin, and there was no proper bulge. This would of some consequences later in her career.

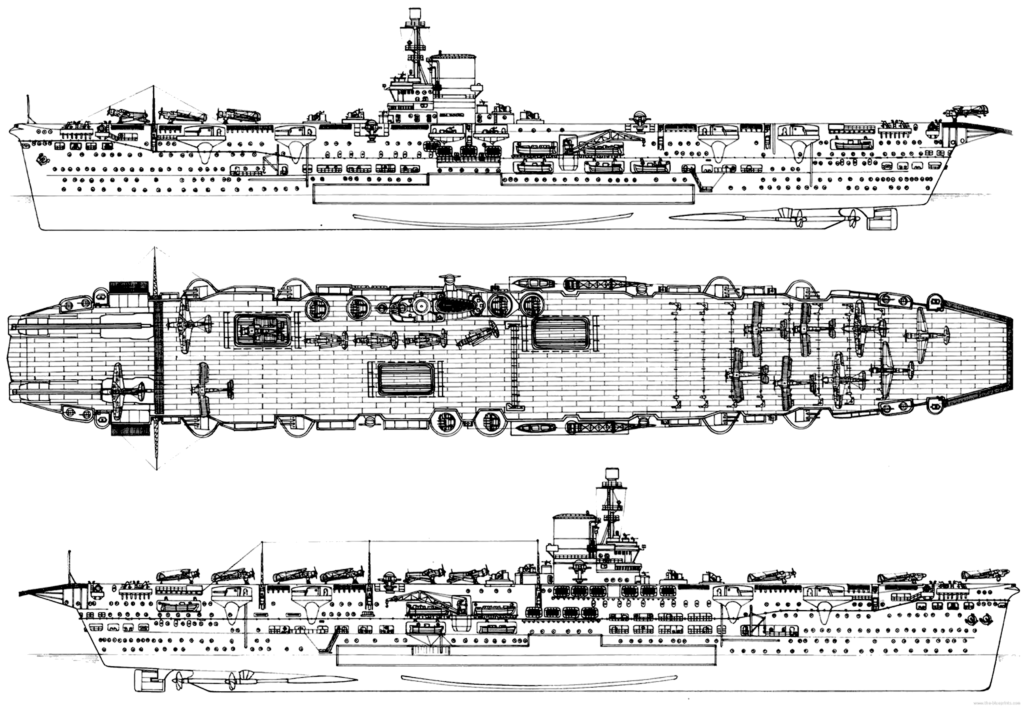

Blueprint of the Ark Royal in 1941

Powerplant

Ark Royal was fitted three shafts propellers connected to Parsons geared turbines, in turn fed by six Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The shafts measured 16 feet (4.9 m) in diameter, the propellers measured 16 feet (4.9 m) in diameter. The powerplant was rated for 102,000 shp (76,000 kW), enough to produce a maximum theoretical speed of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). During her sea trials she showed in fact to be faster, reaching 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) without much hassle.

Armament

It stayed very substantial, although dual purpose, no longer incorporating naval guns. The use of an air group to attack other ships was now being refined. She was however designed with anti-aircraft warfare in mind as ships and submarines could be outrun or the escort’s concern. It comprised a layered AA defence between the long range sixteen 4.5 in (110 mm) DP, six quadruple 2-pdr (40 mm (1.57 in)) and eight quadruple .50 in (12.7 mm) AA machine guns to cover all ranges.

Main armament:

The QF 4.5-inch Mk I naval guns did not existed when the ship was designed, it went at the end of the process, in 1938. The 4-in became the standard medium-calibre naval gun of the Royal navy. It fired a fixed or separate QF, 113 x 640-645mm round (55 pounds-24.9 kg) at 2,449 ft/s (746 m/s). The gun used a horizontal sliding block which could elevate 0° to +80° and had a rate of fire of 12 RPM (Mk II), with manual loading. Its maximum firing range was 20,750 yd (18,970 m) at 2,449 ft/s against surface targets, with a ceiling of 41,000 ft (12,500 m).

They were place don HMS Ark Royal in eight twin turrets embedded in sponsons on either side of the hull. They were controlled by four Directors using the High Angle Control System. This design was judged later unsatisfactory as placed too low to cover both sides of the ship. This was later altered and they were raised just below the flight deck for a better field of fire. The next Illustrious class had them higher up to cover both sides of the ship.

AA armament:

The QF 2-pounder naval gun needs no presentation. Before the introduction of the Bofors, this was the main AA gun in the Royal Navy, quite capable and often mounted in quad and octuple mounts. The “pom-pom” fired fused shrapnel shells forming black plumes around their incoming targets. Its effective Range was 3,800 yards (3,475 m) and Ceiling 13,300 feet (3,960 m) with a muzzle Velocity ranging between 2,040 ft/s (622 m/s) and 2400 ft/s (732 m/s) for the HV round. It lacked both punch and range compared to the Bofors. They were located on the flight deck, in front of and behind the superstructure island.

The last short range layer was a bit of a survival from the interwar: The quad (tandem) Vickers liquid-cooled 0.5 in heavy machine gun were placed on small projecting platforms to the front and rear of the flight deck. This model dated back from 1932 and was already a first choice in the design. In 1940 however it was too weak and slow to face modern 500 kph aircraft. Belt-fed, it fired at 500–600 rounds per minute at a muzzle velocity of 2,540 feet per second but only reaching 9,500 feet (2,900 m) down to 4,265 yards (3,900 m) at low altitude strafing or sea skimming aircraft. The armament was not revised during the war.

Aircraft Group

Blackburn Skua landing on Ark Royal in 1940

Aircraft facilities comprised, as said above, two steam catapults forward, and heavy duty arrestor hooks aft, to free some deck space, added to three lifts: All were close to the main bridge, one forward, one aft of it, both foot of the bridge, and the third on the other side of the deck. They were of equal size, accepting only planes with folded wings, and served all two hangars. The latter kept their aviation gasoline and ammunitions below the second deck, with smaller elevators to have them lifted for deck service. The fully enclose hangars were a gift to protect the aircraft for seawater corrosion, but was a hazard due to fuel vapors, and a comprehensive ventilation system was setup.

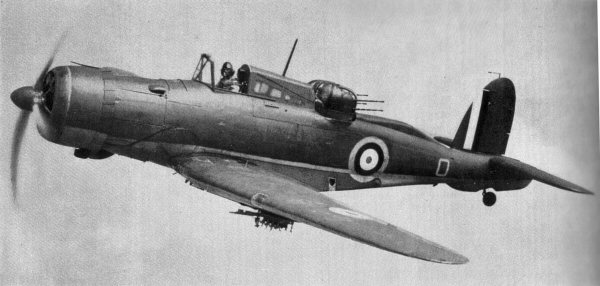

The Blackburn Roc was onboard between April 1939 and October 1940. Its quad turret proved nearly useless in combat.

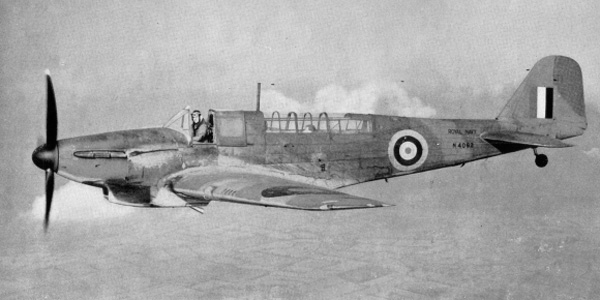

The Fairey Fulmar was a bit more competent as a fighter in replacement for the Skua but never equivalent to a sea Spitfire or sea hurricane.

In all, sixteen Fleet Air Arm squadrons were posted on the aircraft carrier, usually five squadrons at once in each deployment. In January 1939 it consisted only in Blackburn Skuas Mk.II as fighters/dive bombers and Fairey Swordfish Mk.I, used for reconnaissance and torpedo bombing. In April, two squadrons equipped with Blackburn Skua Mk. II and Roc Mk. I were integrated.

From April 1940, Skuas were replaced by Fairey Fulmars, as fighters/bombers. In June 1940 she also had onboard the 701 Naval Air (training) Squadron, flying the Supermarine Walrus amphibian.

Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers started to replace the Swordfish in October 1941, and both operated together. Swordfish were still onboard when the ship was sunk in October 1941 (only Fairey Swordfish and Albacore Mk. Is) -The rather mediocre Blackburn models were all disposed of, leaving the ship without any fighter on board.

The Fairey Albacore was the last addition on board (October 1941). A sturdy biplane, it was supposed to replace the swordfish and was indeed faster with longer range and payload.

Author’s illustration of one of her Fairey swordfish Mk.I, 820 RNAS in 1939.

Author’s profile of the Ark Royal in 1942

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 22,000 lt. standard, 27,720 lt (28,160 t) deep load |

| Dimensions | 800 ft oa/721 ft 6 wl x 94 ft 9.6 in x 27 ft 9.6 in (240/219.91m x 28.895 x 8.473 m) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts Geared ST, 6× Admiralty 3-drum boilers 102,000 shp (76,000 kW) |

| Speed | 30-31 knots (56/57 km/h; 35/36 mph) designed and actual |

| Range | 7,600 nmi (14,100 km; 8,700 mi) at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Armor | Belt: 4.5 in (11.4 cm), Deck: 3.5 in (8.9 cm) (boiler rooms, magazines) |

| Armament | 8×2 4.5 in (110 mm) DP, 4×4 2-pdr (40 mm (1.57 in) pompom, 8×4 .50 in (12.7 mm) AA MGs |

| Aviation Facilities | 2 catapults, 2 lifts, 2 hangars |

| Aviation | 72 designed, 50–60 actual, see notes |

| Crew | 1,580 officers and ratings |

Resources

Links

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Ark_Royal_(91)

//www.kbismarck.com/ark-royal.html

//news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/2585887.stm

//www.naval-history.net/xGM-Chrono-04CV-Ark%20Royal.htm

//www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8418630/A-history-of-Gibraltar-in-pictures.html?image=5

A model kit artwork of the Ark Royal in the Mediterranean (see below)

Books

Balfour, Michael (1979). Propaganda in War 1939–1945: Organisation, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bekker, Cajus (1969). The Luftwaffe War Diaries. Zielger, Frank (trans.). London: Corgi.

Bishop, Chris; Chant, Christopher (2004). Aircraft Carriers: The World’s Greatest Naval Vessels and Their Aircraft. Grand Rapids, MI: Zenith.

Brown, David; Brown, J. D.; Hobbs, David (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Chesneau, Roger (1984). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing.

Duffy, James P. (2006) [2004]. Target America: Hitler’s Plan to Attack the United States (3rd ed.). New York: Lyons.

Edwards, Bernard (1999) [1996]. Dönitz and the Wolf Packs: the U-boats at war (2nd ed.). London: Cassell.

Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Garzke, William; John Dulin (1990). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Garzke, William H.; Dulin Jr., Robert O.; Webb, Thomas G. (1980). Allied Battleships in World War II. Naval Institute Press.

Goldman, Emily O. (1994). Sunken Treaties: Naval Arms Control Between the Wars. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Jameson, William (1 April 2004) [1957]. Ark Royal: The Life of an Aircraft Carrier at War 1939–41 (2nd ed.). Periscope Publishing.

Lenton, H. T. (1998). British and Empire Warships of the Second World War. London: Greenhill Books.

Mitchell, William Harry; Sawyer, Leonard Arthur (1990). The Empire Ships: A Record of British-built and Acquired Merchant Ships During the Second World War. Lloyd’s of London Press.

O’Hara, Vincent (2009). Struggle for the Middle Sea. 1. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

“Conference on the Limitation of Armament”. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States. I.

Paterson, Lawrence (2007). U-boats in the Mediterranean, 1941–1944. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Rossiter, Mike (2007) [2006]. Ark Royal: The Life, Death and Rediscovery of the Legendary Second World War Aircraft Carrier (2nd ed.). London: Corgi Books.

Sullivan, David M. & Sturton, Ian (2010). “Extraordinary Views of HMS Glorious and HMS Ark Royal”. Warship International. XLVII (3)

Stephen, Martin (1988). Sea Battles in Close-Up: World War 2. 1. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Westwood, J. N. (1975) [1971]. Fighting Ships of World War II. London: Sidgwick and Jackson (for Book Club Associates).

Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Battleships 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Another painting of the Ark Royal (src pinterest)

Videos

See also: //youtu.be/fY3FHfWLgc4, //youtu.be/ZM8SA8wSMPo, //youtu.be/G1Ds-dRrtuk, //youtu.be/4TRsuHudRjg

The models corner

-Revell 05149 34.3 cm “HMS Ark Royal and Tribal Class Destroyer”

-AIRFIX 1:600 HMS Ark Royal de type 6 Box Aircraft Carrier Model Kit

-Trumpeter 1/350 HMS Ark Royal 1939

-Merit 65307 – Model Kit HMS Ark Royal 1939

-Aoshima 010228 HMS Ark Royal (1/700)

Prewar service

Construction took time: The hull spent nearly two years in the yard before the launch, on 13 April 1937 on Merseyside. It was in part due to numerous design revisions. The lauch saw her christened by Lady Maud Hoare in front of a crowd of 60,000. She was the wife of Sir Samuel Hoare, First Lord of the Admiralty. But its started badly: The bottle of champagne only smashed at the fourth attempt. Nevertheless, Reverend W. Webb, Vicar of St. Mary’s, Birkenhead made the traditional old blessing. “May God protect this ship and all who sail on her”.

Fitting out took one more year, completion supervised by her very first commander, Captain Arthur Power, which went on board on 16 November 1938, and prepared her and the crew for a commission on 16 December.

HMS Ark Royal’ stern, just completed

Initially, the admiralty planned her to be sent in the far east, but the situation in Europe made her stay after commission. The recent Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935 and the Spanish Civil War in 1936 indicated she would be useful in the Mediterranean Fleet. The crew was completed at the end of 1938 and started training, while HMS Ark Royal started her sea trials campaign for effective service. She reached over 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) without problem, and in May 1938 even achieved 31.2 knots, based on 103,012 rated shaft horsepower, on a light 27,525 long tons displacement. Once done, she was ready for some fixes, and returned for a last campaign of trials, from December 1938 to January 1939, on the Clyde.

On 12 January 1939 she received her first air group, Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers of the 820 Squadron (Lieutenant-Commander A.C.G. Ermen), which proceeded to the first landings and operations. Between January and March: 1939, she departed for a training cruise to the Mediterranean. HMS Ark Royal entered Valetta Harbour, Malta for the first time (the island will took quite an importance in her active life), and went on due east, entering Alexandria to start a serie of exercises with the carrier HMS Glorious. By the end of March she sailed for home waters, recalled as the international situation was tense. She spent the summer 1939 in home waters. On 31 August 1939 the outbreak of hostilities was awaited and the aircraft carrier was back sea with the Home Fleet, starting to patrol the waters between the Shetlands and Norway.

A Blackburn Skua landing on Ark Royal’s deck

1939 hunter-killer group

Eventually a message was received on board informing the captain and crew that hostilities commenced on 3 September 1939; Before the war broke up, Dönitz already pre-positioned his U-boat fleet off the British coast to intercept British shipping. Just hours after the war was made official, SS Athenia was torpedoed by U-30. Soon in a few days, some 65,000 tons of shipping were sunk in rapid succession by U-boats. HMS Ark Royal was deployed in the North Western Approaches in the first “hunter-killer” group, a flotilla of destroyers and ASW vessels helped by the aircraft carrier air group. It was indeed easier for planes to detect submarines underwater. The group also included HMS Courageous and HMS Hermes.

On 14 September 1939, Ark Royal received a distress call from SS Fanad Head 200 nautical miles away, chased on the surface by U-30. Ark Royal’s aircraft scrambled there, but soon after they spotted U-39 in the immediate vicinity of the aircraft carrier. The latter launched two torpedoes, which tracks were followed by outlooks on board, the captain ordering to turn towards those. Both missed and explode astern. F-class destroyers started a depth charge run, and the U-Boat was eventually forced to the surface, badly damaged, while the crew abandoned her, and she sank. Ark Royal had indirectly scored the first U-Boat kill of the war. Meanwhile her Skuas reached SS Fanad Head now in the hands of a German boarding party. They unsuccessfully attacked U-30, but two crashed, caught by the blast and water plume of their own bombs. The U-boat had time to recuperate its boarding party and torpedoed the unfortunate merchant vessel.

Ark Royal was back to base at Loch Ewe later. The ship hosted Winston Churchill which though the U-39 kill was an important morale booster, shadowing the failed attack. HMS Courageous was torpedoed and sunk on 17 September, convincing the Admiralty her carriers were too exposed, and the hunter-killer concept was abandoned.

HMS Ark Royal at sea, src NavieArmatori

Late 1939 Operations

On 25 September, the carrier rescued the crew of the submarine HMS Spearfish damaged by German warships off Horn Reefs (Kattegat). She escorted Nelson and Rodney the following day when spotted by Dornier Do 18 seaplanes. Three Blackburn Skuas were in the air, shooting down one of these, the first British aerial kill. Next, the Germans dispatched four Junkers Ju 88 bombers (bomber wing KG 30): Three were driven away by AA fire, the fourth successfully launched its 1,000-kilogram bomb after diving on the carrier, which spotted it and turned hard to starboard, heeling over, while the projectile hit the water 30 metres off her starboard bow. The Germans later incorrectly claimed to have sunk her, conducting Winston Churchill to personally reassur Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and this later became an embarrassment for Goebbels.

Hunting the Graf Spee

From October 1939, HMS Ark Royal was sent due south, to Freetown in South Africa to operate off the African coast, tracking the German commerce raider Admiral Graf Spee. Assigned to Force K, she sailed with HMS Renown and patrolled the South Atlantic. On 9 October her aircraft located Graf Spee’s tanker Altmark, disguised as US Delmar, so she escaped. On 5 November, the German merchant SS Uhenfels was captured en route to Germany (she would become later the escort vessel Empire Ability). On December 14 at last, 1939, Graf Spee was in Montevideo for repair after the battle of the River Plate. Ark Royal and Renown were dispatched to join the cruisers outside the harbour but there were far from there. To fool the Germans, an order for fuel for Ark Royal was placed at Buenos Aires, west of Montevideo, voluntarily leaked to the press, and ending in the German embassy in Montevideo, convincing Hans Langsdorff to scuttle his ship. That was another famous indirect victory for Ark Royal.

HMS Ark Royal and her air group (src naviearmatori.com)

1940 Operations: Norway

Ark Royal remained in the Atlantic to escort Exeter back to Devonport, arriving in February 1940. She headed for Portsmouth to take on supplies and personnel, then for Scapa Flow. Her Blackburn Skuas were transferred to NAS (Naval Air Station) Hatston. She then sailed to the Mediterranean Fleet for exercises, from 31 March 1940, arriving in Alexandria with HMS Glorious on 8 April. However the exercises were cancelled and order came to rush back to Gibraltar. Indeed, German forces had just invaded Norway (Operation Weserübung) on 9 April. The Royal Navy relief was hampered by Luftwaffe air attacks, and they lost HMS Gurkha while Suffolk was badly damaged. Air cover was urgent so Ark Royal and Glorious were eventually recalled on 16 April.

Both arrived at Scapa Flow on 23 April 1940. They were redeployed for Operation DX, escorted by HMS cruisers Curlew and Berwick, the destroyers Hyperion, Hereward, Hasty, Fearless, Fury and Juno. They took up position on 25 April off the Norwegian coast, 120 nautical miles (220 km) offshore. Their air groups commenced anti-submarine patrols, and fighter cover for the fleet. They also started strikes against German shipping and shore targets.

Ark Royal refuelled on 27 April in Scapa and took on new planes to replace losses. On her way back to Norway she was escorted by the battleship HMS Valiant, but she was attacked by German Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111 bombers operating from Norway, leaving her unscaved. She arrived on 29 April, but soon the British high command realized southern Norway was lost and started evacuation of Allied troops, at Molde and Åndalsnes, covered by Ark Royal the following days. On 1 May, new Luftwaffe air attacks took place and Ark Royal’s fighters and AA fre proved efficient. She took several near-misses though, but only slight splinter damage. One the evacuations done on 3 May, she rushed back to Scapa Flow to refuel and rearm. Captain Arthur Power, promoted rear admiral was replaced by Captain Cedric Holland (which would play later an important role at Mers-el-Kébir). Back to Norway, Ark Royal covered operations around Narvik, notably French troops landing on 13 May, and was reinforced in 18 May by Glorious and Furious.

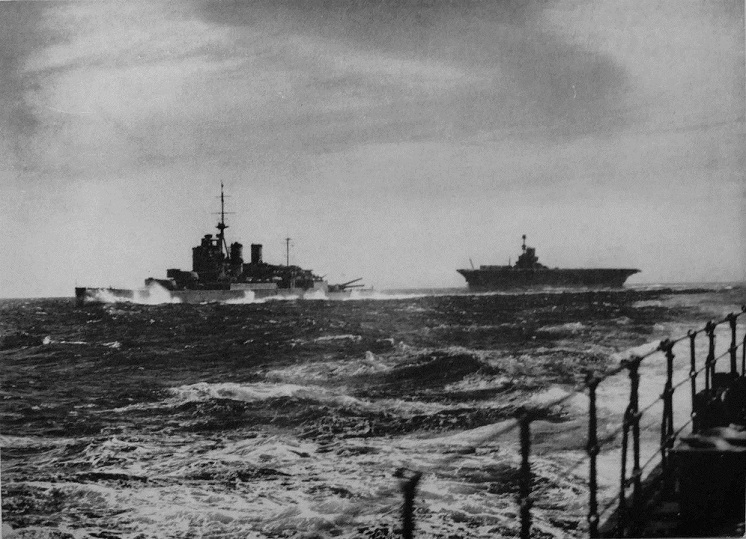

HMS Renown and Ark Royal

By the end of May however, French forces were on the verge of collapse. In Paris and London, Norway now appeared as a sideshow and soon the RN planned Operation Alphabet, the repatriations of allied troops from Narvik, covered by Ark Royal and Glorious escorted by the destroyers Highlander, Diana, Acasta, Ardent, and Acheron. They made the first of several runs from Scapa Flow, on 1 June; Ark Royal’s air group was very active, bombing advancing German troops on 3–6 June, and above Narvik itself on 7 June. On the 8 however, Glorious, was sunk by the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, looked for later by the Ark Royal’s aircraft.

The last convoy back to UK started on 9 June. In between Ark Royal’s planes located Scharnhorst in Trondheim, followed by a Skua attack at midnight on 13 June. The same night however, the escort destroyers Antelope and Electra collided while Ark Royal in heavy fog while on site, the raid proved a fiasco, with eight of fifteen Skuas shot down. KMS Scharnhorst escaped, unscaved.

With the Mediterranean Fleet

Mers El Kebir

Ark Royal left Scapa Flow with Hood and three destroyers, for Gibraltar, Force H (Admiral Sir James Somerville) and soon in August was considered the case of the Frenc fleet after the capitulation. The largest part was in Mers-el-Kébir and it was feared Axis control of these ships would tip the balance of power in the Mediterranean. Ark Royal’s captain, Cedric Holland, was a former British naval attaché in Paris, fueltn in French. He was naturally chosen by Cunningham to negociate with Admirak Buno Gensoul. Under pressure of Churchill (Operation Catapult), it was asked a surrender or scuttling of the French fleet. Force H deployed outside the harbour while negociation soon met a standstill, Gensoul refusing the proposals. The Mers-el-Kébir also comprised a raid by Ark Royal’s planes, used as gunnery spotter and mining the entrance to prevent any escape. Despite of this, Strasbourg escaped, attacked on her way by Swordfish from Ark Royal. Two days after, Dunkerque, beached, was badly damaged by Swordfish.

Ark Royal’s crews hard at work with the torpedoes

Againt the Regia Marina

While on its way to Gibraltar on 8 July, Force H was attacked by Italian bombers but was spared. Nevertheless, Somerville cancelled the raids against Italian coastal objectives. Malta soon came under attack by the Italian air force, Hawker Hurricanes were carried to reinforce the island’s air defences. Force H started operations from 31 July tp 4 August, with HMS Argus as plane taxi and Ark Royal providing air cover. On 2 August, HMS Ark Royal air group soon attacked the Italian air base at Cagliari.

The attack on Dakar

Force H remained at Gibraltar until 30 September, later escorting a reinforcement fleet to Alexandria, attacking Italian air bases at Elmas and Cagliari en route, also as a diversion. Indeed a new supply convoy was soon sailing to Malta, on 1st october. From Alexandria, Ark Royal departed due west and sailed all the way to West Africa, support of a British/Free French attempt to force switch allegiance of Vichy French colonies, starting with Dakar. Negociating aircrews were arrested and negotiations so the air group of Ark Royal targeted military installations but ultimately failed to take Dakar by force. Ark Royal as soon back in home waters for maintenance in dockyard and a refit in Liverpool. This went on from on 8 October until 3 November, including machinery repairs and the installation of a new flight deck barrier.

Battle of Cape Spartivento (27 Nov. 1940)

Ark Royal departed with Barham, Berwick, and Glasgow to Gibraltar, arrivng there on 6 November, and immediately deployed to escort convoys to Alexandria and Malta. After several runs, Ark Royal participated in Operation Collar, a strong convoy to Malta (one of 35 until 1942) on 25 November. A battlefleet led by Giulio Cesare and Vittorio Veneto was scrambled to intercept it, detected by a reconnaissance aircraft from Ark Royal. Immediately, the carrier launched a squadron of Swordfish torpedo bombers while battleships took positions. The Italian destroyer Lanciere was damaged, mistook for a cruiser but after erroneous reports, the Italian commanders folded up, not before ordering a retaliatory attack by the Italian air force. HMS Ark Royal was strafed and bombed but escaped damage. The ended as a draw.

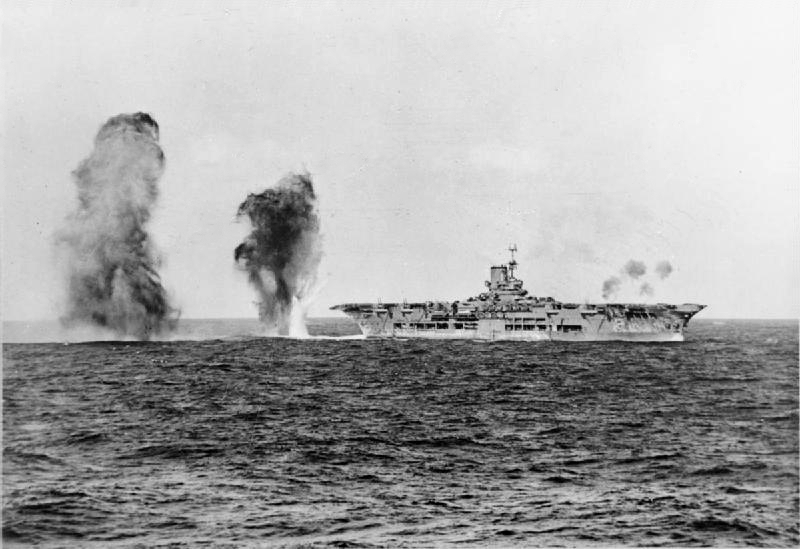

HMS Ark Royal bombed off Sardinia, seen from HMS Sheffield

Operation Excess (Jan 1941)

On 14 December 1940, Ark Royal, as the centerpiece of Force H, was redeployed to the Atlantic. The goal was to operate from the Azores, patrolling in search of German commerce raiders. Ark Royal’s air group however potted none. The aircraft carrier returned to the Mediterranean on 20 December, escorted by HMS Malaya. She escorted merchant vessels arriving from Malta. The crews rested in Gibraltar in 28-30 December, while Force H was prepared for Operation Excess: The plan was to bring a large reinforcement convoy through the Mediterranean, to support the Western Desert Force trying to chase off Italian forces from Egypt into Libya. However the presence of the Luftwaffe, and soon the arrival of the Africa Korps, threatened British control of the Mediterranean. Soon, the aircraft carrier Illustrious was badly damaged and out of the game for some time. The Eastern Mediterranean Fleet (Alexandria) was especially weak, while Hitler attempted to draw into the war. Against the whole Spanish army, fleet and air force, Gibraltar would have stood little chance. So to relieve the Mediterranean Fleet and as a show of strength towards the Spanish, the Admiralty confered with Admiral Cunningham about the use of Ark Royal bombers for a serie of raids against Italian objectives, supported the surface fleet battleship and cruisers shelling. The first raid was mounted on 2 January against the Tirso Dam, Sardinia. But it was largely unscaved. The Swordfish on 6 January bombed Genoa with more success and covered Renown and Malaya shelling the port. On 9 January, Force H bombed and shelled the oil refinery at La Spezia while laying mines in the harbour.

HMS Ark Royal under air attack

Searching for Scharnhorst and Gneisenau

In early February 1941, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were signalled into the Atlantic, in a mission to disrupt Allied shipping, drawing away British capital ships, both as a diversion and offering targets of opportunity for U-Boats. On 8 March, Force H and Ark Royal headed for the Canary Islands, refuelled and from there, searched for the “terrible twins”. They were also scrambled to cover convoys coming from the United States. HMS Ark Royal deployed her air group in a large search pattern area, and three prize crew German ships were located on 19 March: Two which scuttled themselves and a third, the SS Polykarp, which was was recaptured. On late 21 March 1941, one of the carrier’s Fulmar at last located Scharnhorst and Gneisenau underway. Fate would have the info was never sent due to a radio malfunction. By the time the plane landed to deliver their report, both German ships had vanished in the fog, while the next day, new air patrols were sent, hoping to relocate them. Then bad luck stroke when after a catapult malfunction the Fairey Swordfish plunged into the sea, juste ahead of the carrier’s prow, which ran over it when its depth charges exploded, damaging her bow. Meanwhile, the German battleships were back in Brest. Ark Royal was in Gibraltar for repairs on 24 March.

Alexandria convoys, Operation Tiger

HMS Ark Royal spent the month of April 1941 between convoys and escorts and ferrying aircraft to Malta. She also made another sweep from the Azores in the Atlantic in search of commerce raiders. In May 1941 the Afrika Korps was now closing onto the Suez Canal and the Western Desert Force was hard-pressed. The admiralty decided the situation was desperate enough to send a large convoy to Alexandria. It only counted five large transport ships, escorted by Ark Royal, Renown, Queen Elizabeth and the cruisers Sheffield, Naiad, Fiji, and Gloucester plus the 5th Destroyer Flotilla. Captain Holland just before the mission, left exhausted, and was replaced by Captain Loben Maund. The convoy left Gibraltar on 6 May 1941, and was soon detected by Italian aviation. Underway at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) it became a target of choice for the axis which prepared a massive serie of air attacks.

HMS Ark Royal Underway

This started on 8 May, by the Regia Aeronautica followed by the Luftwaffe. The only 12 Fairey Fulmars on board managed to repel 50 aircraft, using Sheffield’s recent radar for directions and deliver accurate anti-aircraft fire. One Fulmar was lost, another destroyed and several damaged, leaving seven when the Luftwaffe 34 bombers arrived. Again, they were driven off and the convoy survived, while naval mines claimed the Empire Song and New Zealand Star (which was able to reach Alexandria). Ark Royal departed as the convoy arrived, but was submitted to another aerial attack on 12 May on her way back. She was soon back at sea to team with Furious and deliver Hawker Hurricanes to Malta.

Hunting the Bismarck

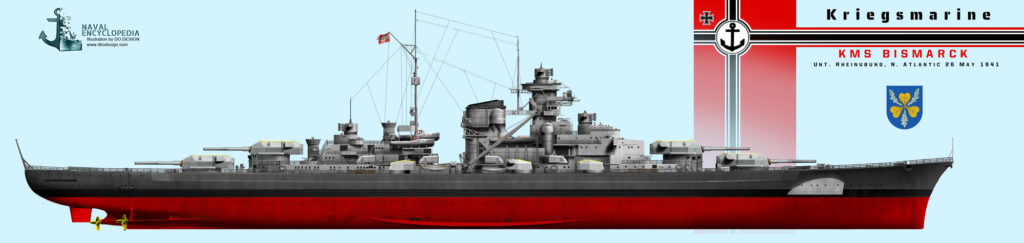

Bismarck in the Atlantic, 26 May 1941, the day she was attacked by Ark Royal’s swordfish. Her AA was setup for faster targets, which helped the pilots. A single lucky hit doomed her.

One of the most amazing naval episode of WW2 at sea was the hunt for the brand new, fearsome German battleship. Barely ten days after Operation Tiger, on 18 May 1941, KMS Bismarck made a sortie with Prinz Eugen, Operation Rheinübung. This was a shipping raid, which started badly for the Royal Navy: The Hood was sunk and the Prince of Wales damaged at the Battle of the Denmark Strait. Churchill, adamant the ship was to be sunk, ordered all escorting and available force to scramble in pursuit. As Bismarck headed for headed for the French Atlantic coast, Force H departed, with Ark Royal, Renown, and Sheffield on 23 May. Three days later, one of her Swordfish located Bismarck, helping the the Home Fleet to concentrate.

Admiral Sommerville congratulating Ark Royal’s crew (IWM)

When spotted, the Bismarck was still 130 nautical miles away and she still could reach Saint-Nazaire, so under the cover of the Luftwaffe. This was the RN last hope to halt her. Fifteen Swordfish armed with torpedoes took off, but soon ran into HMS Sheffield, shadowing the Bismarck and in bad weather and mist, attacked her until figuring out their own mistake. Fortunately the cruiser dodged their torpedoes while several prematurely exploded due to their unreliable magnetic detonators. Back at the carrier while time was running out, the crews scrambled to rearm the torpedoes with contact-detonators. At 19:15 as dark was already falling, the squadron took off for second attack. It was the last chance to get the Bismarck before sunset. The Swordfish at last located her, and attacked, scoring three torpedoes hits. But her thick belt prevent much damage forward of the engine rooms. The third however was a lucky one, hitting the starboard steering compartment. It succeeded in jamming rudder. At that time Bismarck was trying to evade the torpedoes, manoeuvring, and she was caught in a 15° port turn. By alternating propeller speeds she could make a reasonably steady course which but in waves of force 8 she was heading straight towards the British warships and was caught and destroyed on 26–27 May.

The last convoys for Ark Royal (June-November 1941)

Force H was back to Gibraltar on 29 May 1941. Allied morale was raised after the Bismarck sinking, but the Mediterranean situation was still extremely precarious. Greece and Crete just fell and Rommel prepared his final push into Egypt. Malta was the last stronghold in between Gribraltar and Alexandria, but under the “blitz” of axis aviation. Ark Royal was tasked to deliver more aircraft to Malta and started a serie of dangerous runs in June and July. Operation Substance in July was so far the largest, and it was followed by Operation Halberd in September. This helped Malta, and the latter became a real threat for Rommel operations in Africa, as it sunk supplies incoming from Italy. Malta base indeed deployed submarines and bombers. Adolf Hitler decided to send U-boats there to attack these convoys despite the opposition of admiral Raeder.

U-81 in the Mediterranean. Guggenberger’s submarine served with the 29th U-boat Flotilla and was sunk by aviation in 1944 in Pola.

On 10 November 1941, Ark Royal was back from her last mission to Malta, heading towards Gibraltar when Admiral Somerville received warning of U-boats off the Spanish coast. At the same time, U-81 (Friedrich Guggenberger) was also signalled Force H underway to Gibraltar and deployed in an interception course. On 13 November, at 15:40, the destroyer Legion’s sonar operator signalled an unidentified sound, soon though to be another nearby destroyer while just a minute later, Ark Royal was struck amidships by a torpedo. It hit between the fuel bunkers and bomb store below the bridge island. The explosion was catastrophic: Ark Royal shook violently while torpedo-bombers were thrown into the air. But despite this, amazingly only one sailor died, 44 year old Able Seaman Edward Mitchell. There was now a 130 x 30 feet gash on her starboard side, below the waterline. It was later evaluated that the torpedo ra too deep and struck bilge keel before detonating, damaging the inboard longitudinal bulkhead. A massive flooding of the starboard boiler room started, and soon the main switchboard and oil tanks were contaminated by seawater. About 106 feet of her starboard bilge was underwater and she lost also her starboard power train. She lost in fact half of her powerplant and internal communication, but still had power.

The Ark Royal’s evacuation (gallery)

Captain Maund ordered a full stop via a runner to the engine room, which took time. The carrier started to list to starboard, soon reaching 18° in 20 minutes. Remembering the fate of Courageous and Glorious, Maund gave the order to abandon ship, and crews were assembled on the flight deck, soon assisted by HMS Legion which came alongside. The captain and part of his staff picked up the remaining team that would be tasked to save the ship. Damage control started, but only 49 minutes after the torpedo hit, while flooding progressed, helped by the hatches left open during evacuation. Soon, water pressure forced the centreline boiler room, and the ship lost all power (including the pimps and backup diesel generators). Nevertheless, the ships started to stabilise and Admiral Somerville ordered damage control parties prepared the ship to be towed to Gibraltar by HMS Malaya.

About 35-40 min. after, the team succeeded into re-lighting a boiler, restoring enough power to activate the bilge pumps. HMS Laforey came alongside in turn to provide additional power and pumps. Meanwhile, Gibraltar scrambled its own Swordfish aircraft to patrol the area in search of U-Boats. The tug Thames arrived, also from Gibraltar, at 20:00. But as it started to two the Ark Royal, her list started again and soon the sole running boiler was shutdown. As the list reached 20° during the night, around 02:30, but stabilized somewhat. Nevertheless, the ‘abandon ship’ order was declared again at 04:00, as she was reaching 27°. The last men were evacuated by 04:30. 1,487 were transported to Gibraltar. The men were saved, not the ship. When reaching 45°, HMS Ark Royal at last capsized and sank for good at 06:19, on 14 November. After rolling over she broke in two and the aft section sank first, followed by the bow.

HMS Implacable in 1944. The lessons learnt by the loss of the Ark Royal helped her design. She was not only armoured, but even more safer than the illustrious class as a result.

The enquiry

The long duration of the listing and apparent lack of efficience of the damage control team led a Board of Inquiry to investigate. At its conclusion, it found Captain Loben Maund guilty of negligence and he was court-martialled in February 1942. The first point was the failing to ensure to constitute a proper damage control party on board after the general evacuation, and sufficient state of readiness to deal with possible damage. It was moderated however due to near-miraculous saving of the crew. At the end of the day however, in November 1941, the Royal Navy was left with just a few operational carriers: The old Eagle and Hermes (deployed in the far east), Furious (soon in drydock), while both armoured carriers, Illustrious and Formidable were in drydock for reapairs, leaving only Victorious, which her crew still training, barely operational, and Indomitable just completed (On 10 October). The situation mirrored the USN Pacific Fleet before Midway.

The Bucknill Committee’s report at least helped carrier construction, by establishing the backup power sources location were a design failure contributing to the loss. Electricity wad dependent of boilers and steam-driven dynamos. Recommendations about the bulkheads and boiler intakes design also was revised to avoid widespread flooding, as well as the uninterrupted boiler room flat. These were passed onto the construction of the Implacable-class fleet carriers under construction and the light carriers of the Colossus, Majestic and Centaur class as well. The wreck was rediscovered by C & C Technologies, Inc, and underwater vehicle, some 30 nautical miles from Gibraltar under 1000 metres. This led to a BBC documentary on maritime archaeology. The wreck was found further east than expected, carried by currents, but this was later contested.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

The data under the heading Ark Royal (1939) is for some other ship, not Ark Royal.

Well spotted John !

It was from a cruiser, just updated it, thanks.