The pride of the Dutch Navy

Although the De Ruyter was far from the most ambitious project of the Dutch Netherlands Navy intended for the Oostindies Marine (East Indies Navy), which were the De Zeven Provinzien class cruisers, cut short by the war, the best Dutch cruiser in service when the war broke out was HNLMS De Ruyter. But it was not present to defend the homeland, but rather the economic pump that were the Dutch East Indies colonial possessions, now under threat of the Japanese. In early 1942, like the rest of the east Indies Navy, De Ruyter fought at the Battle of Bali Sea, Battle of Badung Strait, and Battle of the Java Sea, carrying the flag of admiral Karel Doorman at the head of the allied ABDA squadron, decimated by the Imperial Japanese navy on 27 February 1942. Was it due to the cruiser’s inadequate protection or design, or just better Japanese tactics ?

Development History

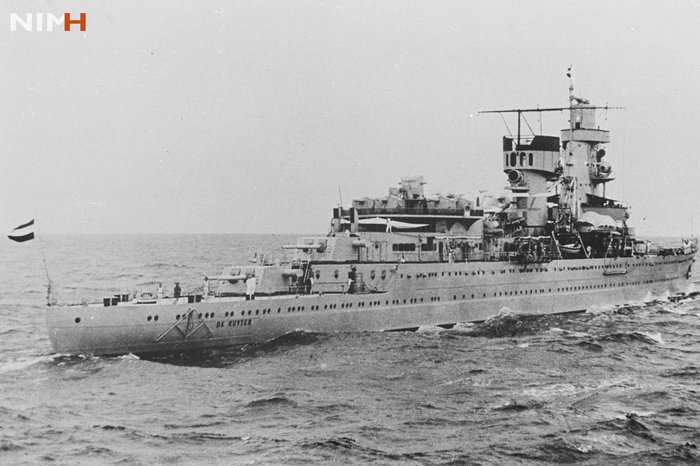

With it’s look of faux Graf Spee (Deutschland class) the ship looks at it went directly from a German ship designer, as was the case of one installed in the Hague, but for U-Boats. In reality she was hundred per cent Dutch in thinking and design, but for the armament (Swedish) and propulsion (British).

It should be recalled the context of her planification: Her design design started right at the heart of the Great Depression, an obtaining a vote from the diet (parliament) was an all-out battle in itself. But even when secured, the budget allocated as meagre to say the least. The admiralty wanted two, to work in pair like the previous Java class they were supposed to replace. but in the end only a single ship was secured, while engineers were ordered to save as much money as they could squeeze out of her. In addition to the budget restrictions of the crisis, the Netherlands were in the midst of a strong pacifism movement, that also impacted the air force, but overall the army. The East Indies, albeit vital for the hardly pressed Dutch economy, was far away and the Japanese threat, quite remote for the general public.

It should be recalled the context of her planification: Her design design started right at the heart of the Great Depression, an obtaining a vote from the diet (parliament) was an all-out battle in itself. But even when secured, the budget allocated as meagre to say the least. The admiralty wanted two, to work in pair like the previous Java class they were supposed to replace. but in the end only a single ship was secured, while engineers were ordered to save as much money as they could squeeze out of her. In addition to the budget restrictions of the crisis, the Netherlands were in the midst of a strong pacifism movement, that also impacted the air force, but overall the army. The East Indies, albeit vital for the hardly pressed Dutch economy, was far away and the Japanese threat, quite remote for the general public.

The fact she remained single was a refection of the fact she was classified afterwards as a ‘Flotilla Leader’ instead of a cruiser. Her armament was a reflection of this. She was supposed to deal with other light cruisers and destroyers.

Context

The Java class cruisers, essentially a 1917 design.

Shortly after World War One, a strong wave of pacifism swept through the Dutch population, influencing deeply Dutch politics. The horrors of what happened left so many negative impressions, that calls for general disarmament were louder than ever. In 1919, political parties went as far as proposing a complete disbanding of the Dutch Royal Navy as a military organization. Fortunately, no majority at the House of Representatives was achieved on this question. But it influenced the then Minister of the Navy, mr. Ch.J.M. Ruys de Beerenbrouck, found a compromise by cancelling the third of the Java class cruisers, HLNMS Celebes (in construction) while a tender for three more was cancelled.

In 1922, the navy law committee determined that the fleet for the coming years should consist of at least six cruisers. By October 1923, this plan was rejected by the Lower House. In 1930, Secretary of the Navy, Dr. L.N. Deckers determined the navy construction policy for the remainder of the interwar. The so-called “Fleet Plan Deckers” included just half the units asked by the admiralty compared to 1922 plan, and derided as “half minimum”. It was certainly not sufficient to defend the east Indies AND homeland at the same time, so the bulk was concentrated on the east indies as it was believed Europe’s military matters would be settled by France and UK and their respective, powerful navies. In the end, building a third cruiser ensured there would always be two cruisers available for the defence of the east indies, even if one cruiser was in repairs or maintenance. Having two light cruisers to defend the entire area against the Imperial Japanese Navy full might seemed ludicrous in 1937, and that’s when a new naval law calling for larger warships (never built in the end, these would have been the Zeven Provincien battlecruisers).

As the time Hr. Ms. Java and Sumatra were completed, Deckers’s plan granted space for the construction of a third cruiser (the former Celebes). Discussions started within the navy on how to deign it, while the government asked about its desired characteristics. The Dutch Royal Navy wanted a main armament of 20 cm guns, and torpedo tubes, something close to a heavy cruiser (Washington). However, after pacifism, a second wave broke the admiralty’s dreams, this time the budget post-1929 crisis severely restrained what could be allocated to the future ship. Minister Deckers in 1931 wanted as a result a smaller ship than the Java class, with a primary armament of only six 15 cm guns in three turrets. And even in this context, the parliament postpone the construction for one more year. Experts meanwhile in the Navy knew only six 15 cm guns were way too small for their needs.

The design is precised (1932)

In 1932, a compromise was found: The new cruiser, provisionally called “Celebes” was to be a flagship, with accommodation for a squadron commander and staff. It would have to fulfill purposed of a staff ship so that its final design could be slightly larger, space being created for a fourth turrets and reach thus eight 15 cm guns. However it was still politically sensitive, and the navy compromised on its side, by accepting a single extra gun under mask instead of a turret. In addition, cutbacks on armor plating and torpedo launchers were also consented, meaning it was only armed with AA as a complement. The final design was prepared by engineer G.T. Hooft, the head of the Naval shipbuilding office, resulting in a light cruiser with generous dimensions to fulfill its future tasks, but knowingly too lightly armored and armed for its displacement and the standards of the time. For the same tonnage, the Soviet Kirov class cruisers for example had nine 170 mm guns, and torpedo tubes, and a slighlty better protection.

De Ruyter in construction at Wilton Fijenoord, close to launch in March 1935.

On September 16, 1933, her keel was laid at Wilton Fijenoord, Schiedam. It took more than three years before she was put into service, as Hr. Ms. De Ruyter. She took the name of a destroyer (Admiralen-class) which was renamed Ghent when baptised on 11 march 1935 during her launch, and was completed in 3 october 1936. Her career would span seven years, until 27 February 1942. In combat, her limitations became self-evident.

Design of the Hrms De Ruyter

Hull & general design

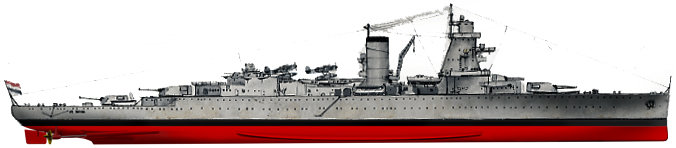

There are superficial similarities with the German Deutschland class built earlier, but the design was just an extrapolation of the cancelled Celebes, the third Java class cruiser of 1920. Innovation of the time meant, she was to be fitted at least with twin turrets, but it was still a far cry from the Java, which had ten 15 cm guns in all, albeit with some placed on the broadside, where they only can fire that side. Turrets in the centerline allowed for a larger arc of fire and thus, to ensure equal firepower with less guns: Still seven per side.

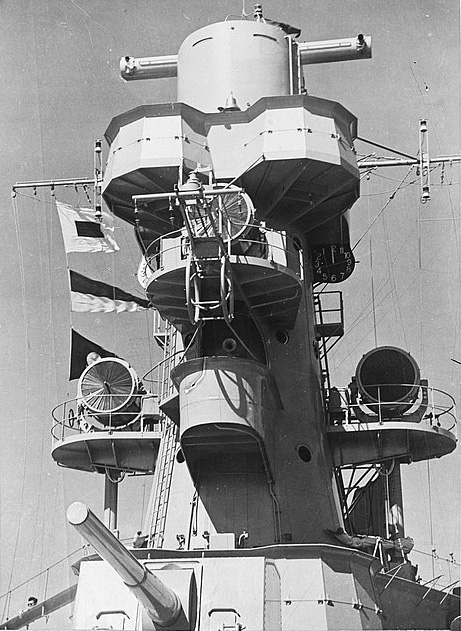

The hull was conventional, high to ensure good seakeeping, with a long, roomy forecastle and lower aft deck with the turret Y and X superimposed, a straight stem but semi-bulbous bow and clipper style stern. The ratio length/width was of 1/11 (170.9 m (560 ft 8 in) by 15.7 m (51 ft 6 in), so a “destroyer waist” ensuring fine lines and take the best of the available powerplant. She had a also a draft of 5.1 m (16 ft 9 in), but at the stern the keel was not horizontal, but blueprints shows a declivity of about 50 cm between the prow and stern, the latter being deeper, for finer penetration. The other obvious differences with the Java class were the single funnel and massive tower-like bridge structure. The latter was dictated by the admiral and staff facilities. There was a command bridge and admiral bridge. It was not straight but prismatic, with a larger base aft. Between this, the single funnel, small turrets and extensive aviation facilities, this cruiser was relatively easy to recognise, but at first glance from afar, still could pass for a Deutschland class cruiser in its proportions and dimensions, more so if she raised her three forward guns together.

Armor protection

Her protection was probably the weakest imagined or designed for a ship of her tonnage: She was given a belt stretched between barbettes as usual, just 5 cm/50 mm thick (2.0 in) for about 3 meters high, including 80 cm below the waterline. The ASW compartmentation was basic, with side storage rooms filled with oil or seawater and a compartmented machinery and boiler rooms, enclosed between bulkheads. She had a single armored deck, 3 cm/30 mm (1.2 in) in thickness. Both were already not enough to defeat the usual destroyer rounds (120-130 mm), more so for any cruiser caliber. The turrets were equally paper-thin, just protected by 3 cm/30 mm of armour (1.2 in). There is no clue of extra armour stray above the ammunition magazines and steering room. Not doubt this played a role in her demise when facing the Japanese.

Propulsion

One of the choices made concerned the powerplant, British-built, with three Parsons geared steam turbines, connected to two shafts. Steam was fed by six Yarrow boilers, for a total of 66,000 shp (49,000 kW). This allowed for a top speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph). Her overall range was 6,800 nmi (12,600 km; 7,800 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). It was not a problem where she expected to serve, as supplies depots of the numerous islands in Indonesia allowed her to be sure of refuelling frequently. Her unique funnel was topped by an equally unique structure, above it and behind, tailored to deflect exhaust fumes.

Armament

That was assuredly the other weak point of the design. The ship was heavy enough to carry if needed 8-inches guns, although in reduced number. 6-in seemed more reasonable given her light construction, and as we saw earlier, even the admiralty, which wanted understandably eight guns in four twin turrets, tuned it down and censored itself by fear of seeing the project cancelled by the parliament. Instead of what could have been the twin turret “B” was installed a single gun under mask. It should be recalled by the contemporary Arethusa class, also armed with six guns, had a displacement of 5,000 tonnes, 2,000 tonnes less than HLNMS Ruyter. So in the end, she ended with a configuration 3×2 +1.

-15 cm Bofors guns:

The 5.9 in guns in twin turrets were Mark 9, the single one was a Mark 10. They were all made in Sweden, at Bofors. These were 15 cm/50 (5.9″) shared already with the cruiser HLNMS Tromp.

They used horizontal sliding breech-blocks, and had a rate of fire of about 5/6 rounds per minute, muzzle velocity of 2,953 fps (900 mps) and range at 29° of 23,200 yards (21,214 m) and at 45° of about 30,000 yards (27,400 m).

This main battery of was controlled by a fire control system designed with with a Hazemeyer patent, built by Wilton Fijenoord under license from Bofors.

More on these: http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNNeth_59-50_mk9.php

-40 mm AA (Bofors):

The 40mm machine guns were rapid-fire cannons with automatic ammunition supply designed by Krupp in Germany towards the end of WWI. The patent was filed with Bofors. The four twin mounts were all placed together on the aft superstructure’s roof, close to the their fire control. Therefore the entire battery was very vulnerable and could be completely disabled by one direct hit.

-12.7 mm AA:

The were apparently the American-supplied Browning M1920 HB heavy machine gun (0.5 inches).

Fire control

HrMs De Ruyter had however a first strong point when entering service in 1936: She could be regarded as one of the most modern cruisers in the world in the field of fire control and anti-aircraft defense. The latter consisted of four twin mounts, stabilized on three-axis, 40 mm machine guns served with an advanced fire control system. Located on a raised deck aft these had an excellent arc of fire. They used optical and radio range finders. The main fire control system was developed by Hazemeyer’s Signaal Apparaten in Hengelo, (founded 1921) a cover for for a German company resettled in the Netherlands, formerly Siemens & Halske, joint with Dutch industrialist F. Hazemeyer.

Aviation

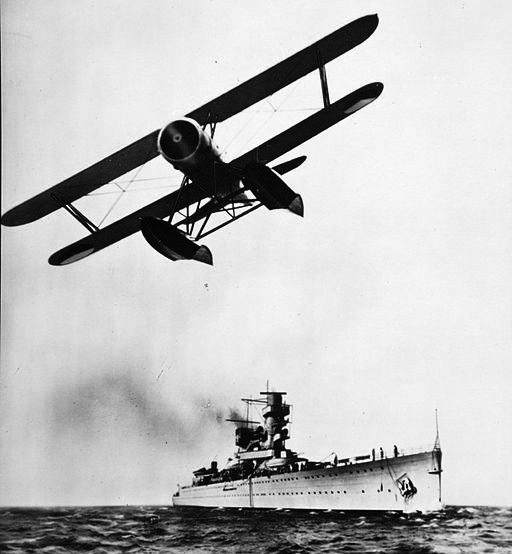

Fokker C-XI-W – src pacificeagles.net

This was another strong point of the design: The new cruiser was the only Dutch warship ever equipped with a catapult installation made by Heinkel. It allowed her on-board aircraft to be launched underway in all conditions. A major advantage over the lifting method from crane or loading booms. The cruiser had room for two aircraft, and technical drawings shows these two onboard, but this was never confirmed in photos. It seemed she only operated one at all times, since there was no hangar but a small maintenance/workshop facility.

Specs of the Fokker C-IX W: 10.40 x 13.00 x 4.50 m, 1,715 kg/2,545 kg (5,611 lb), propelled by a Wright R-1820-F52, 578 kW (775 hp) up to 280 km/h over 730 km (454 mi, 395 nmi). She had a fixed 7.7 mm MG in the engine cowling and a trainable aft.

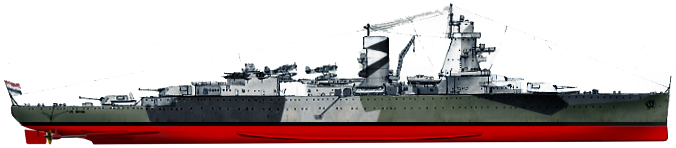

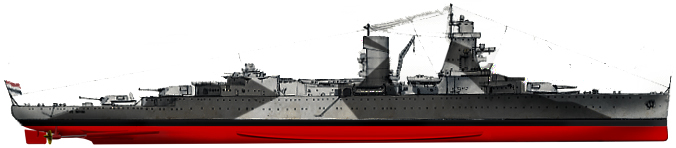

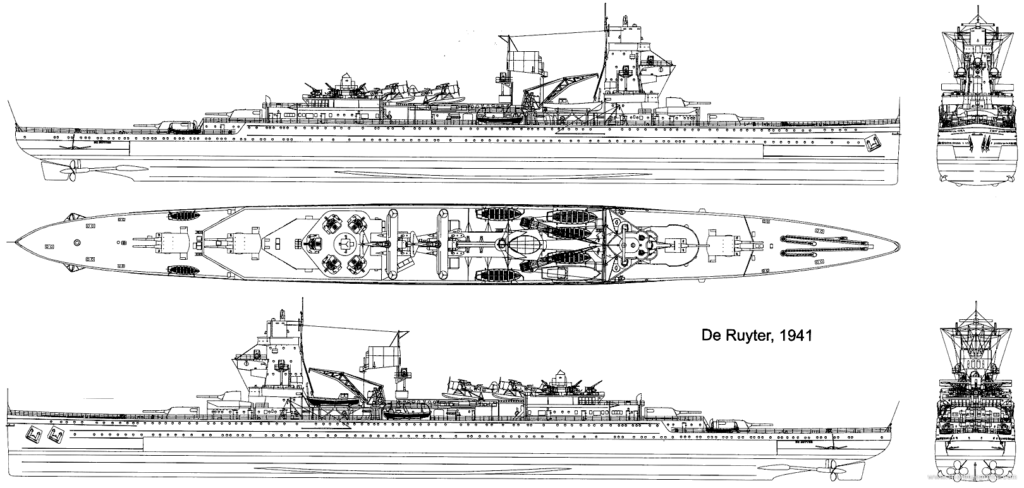

Two views of the De Ruyter (the blueprints)

Author’s illustration of the De Ruyter in 1939

Author’s illustration of the De Ruyter in January 1942

Author’s illustration of the De Ruyter at the battle of Java in late February 1942

Specifications De Ruyter as completed |

|

| Displacement: | 6,545 tons standard, 6,650 tons full load |

| Dimensions: | 170,9 x 15,7 x 5,1 m (561 x 51 x 17 ft) |

| Crew | 350 |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts steam turbines, 6 boilers, 66,000 shp |

| Speed | 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) |

| Range | 6,800 nmi at 12 knots |

| Armament | 7x 150, 10x 40, 8x 12.7mm |

| Armor | Belt: 5 cm (2.0 in), Deck, Turrets: 3 cm (1.2 in) |

| Aviation | 2 Fokker C-11W floatplanes |

More resources

Read More

//alchetron.com/HNLMS-De-Ruyter-(1935)

//www.tracesofwar.nl/articles/2190/Hr-Ms-De-Ruyter.htm

//www.netherlandsnavy.nl/Photo_ruyter.htm

//ahoy.tk-jk.net/Letters/DutchshipsdeRuyterandJava.html

//en.topwar.ru/166385-boevye-korabli-krejsera-krasavchik-neudachnik.html

//www.navypedia.org/ships/netherlands/nl_cr_de_ruyter.htm

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HNLMS_De_Ruyter_(1935)

//marineschepen.nl/schepen/kruiser-de-ruyter-1936.html

//www.netherlandsnavy.nl/DeRuyter1.htm

//www.militaryhistoryonline.com/?aspxerrorpath=/wwii/articles/endofbattleofjavasea.aspx

//www.tracesofwar.nl/articles/2190/Hr-Ms-De-Ruyter.htm?page=4

//pacificwrecks.com/people/visitors/denlay/index.html

//www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/16/three-dutch-second-world-war-shipwrecks-vanish-java-sea-indonesia

//www.historyanswers.co.uk/history-of-war/java-sea-shipwrecks-of-world-war-2-one-of-the-men-who-found-them-reflects-on-their-loss/

Books:

Conway’s all the world figjting ships 1922-47

Van Oosten, Franz Christiaan. “Her Netherlands Majesty’s Ship De Ruyter.” Profile Warship (Anthony Preston)

Teitler, G. (1984). De strijd om de slagkruisers. Dieren: De Bataafsche Leeuw.

Legemaate, H.J.; Mulder, A.J.J. (1999). Hr. Ms. Kruiser ‘De Ruyter’ 1933-1942.

Karremann, Jaime (February 27, 2017). “Lichte kruiser Hr.Ms. De Ruyter (1936)”

Models Corner:

Pacific crossroads resin 1/350

Review of the latter

The epic Career of the De Ruyter

Early career 1936-1940

In October 3 1936, De Ruyter was offcially completed, and commissioned, under command of her first Captain, A.C. van der Sande Lacoste. On January 12, 1937, she departed for her intended operation theater, the Dutch east indies, arriving on March 5, in Tandjong Priok (Java). Her crew started to train intensively, with other destroyers, the pair of Java-class cruisers, and the naval air base. In October 1937, Lt. Cdr. J.B. Meijer took command as commanding officer and in January 1938, he was relieved by L.G.L. van der Kun, later promoted captain in April 1939. In May, 4, 1939 Captain H.J. Bueninck took command of the ship, while the cruiser made local patrol cruisers, amidst growing tensions in Asia. In December, she took part in a large squadron also comprising the cruiser Java and a division of submarines in the Java sea. Messages has been intercepted indeed of a Japanese concentration of naval forces near Formosa. Captain H.J. Bueninck on May, 10, was informed of the German invasion back home and of the state of war. The KNIL staff knew full well the possible agreements made between the Germans and Japanese. Soon after, Karel Doorman arrived at the head of the squadron and made the cruiser his home for the remainder of the war in the pacific.

About admiral Karel Doorman

K. Doorman was born 1889 in Utrecht, raised as a Roman Catholic, from a military family. In 1906 he was commissioned as midshipmen and became officer in 1910, moving to the Dutch East Indies aboard the cruiser HrMs Tromp. Until December 1913 he also served on the survey vessels HNLMS van Doorn and HNLMS Lombok, mapping coastal waters of New Guinea. He was back home in 1914, still onboard De Ruyter and in March requested his transfer to the Aviation. He became pilot in mid-1915, one of the first Dutch naval air officers. As pilot he served until the end of the war at Soesterberg under command of Captain Henk Walaardt. He became an instructor at Soesterberg and the first Dutch Naval Air Base, De Kooy, in Den Helder. He eventually commanded the base until 1921.

Despite budget cuts and pacifism he he attended the Higher Naval School in The Hague in 1921-23, working in particular in aircraft coordination and naval vessel communication. Her served with the Department of the Navy at Batavia in December. In 1926 he served in the De Zeven Provinciën, became the ship’s gunnery officer, first officer. from 1928 he was in the hague, as part of the commission purchasing equipments for the Naval Aviation department. In 1932 he commanded the minelayer HNLMS Prins van Oranje in the Dutch East Indies, and two destroyers, HrMs Witte de With and Evertsen. In January 1934, after commanding the Evertsen he became Chief of Staff in Den Helder. In 1936, he asked the Secretary of Defense to command a cruiser in the Dutch East Indies, became a Captain in 1937 and commanded the Sumatra and Java. By August 1938 he became commander of the Naval Aviation in the Dutch East Indies, with his HQ in NAS Surabaya Morokrembangan.

On 16 May 1940, he was promoted to Rear-Admiral and was found in command of the cruiser De Ruyter the next month, replacing Rear-Admiral GW Stöve at the head of the Surabaya Squadron. In early 1942, he led the ABDA. The rest is detailed in the following actions as his own career and fate is intrinsic with the cruiser. When his ship was torpedoed by the Japanese in the Java sea, following navy tradition he went down with the ship, as his captain. On 5 June 1942, he was posthumously made a Knight 3rd class in the Military William Order, awarded to his eldest son on 23 May 1947 by Lt.Adm. Conrad Helfrich on board HNLMS Karel Doorman first Dutch warship of the name, in a grand and moving ceremony attended by Prince Bernhard.

Four ships would be name posthumously after the heroic admiral, bearing the motto “Ik val aan, volg mij” (I am attacking, follow me). These words (and signal) however is likely has never been pronounced. At Kloosterkerk (The Hague), there is a memorial plaque, and commemorations for the Battle of the Java Sea are held there each year.

1941-42

From the summer of 1940 until Pearl Harbor, De Ruyter patrolled the East Indies, from the Surabaya squadron Naval base. On 27 January 1941, J.H. Solkesz took command of the cruiser. In March, she escorted the passengership Oranje (20.017 GRT) on her first trip to Singapore, leaving her to return to the Moluccas. She then moved with other KNIL units near Morotai on March, 19. She had her boiler repaired at the end of the month and performed post-refit sea trials and additional training.

on April 22, 1941, HrMs De Ruyter was based in Soerabaja, and in May, a message came about two German merchants vessels escorted by the Italian colonial patrol sloop Eritrea left Japan. Thus, the admiralty planned and interception and the squadron was sent to the eastern archipelago. But they never received news of the convoy, which left the area and came back home unscaved.

On August 8 1941, Commander E.E.B. Lacomblé took command, relieving J.H. Solkesz. Both him and Doorman served well together and met the same fate in February 1942. In November 1941, with tension growing even larger between the USA and Japan, HrMs De Ruyter sailed wit the destroyers Banckert, Witte de With, Kortenaer and Piet Hein to Koepang. Messages were intercepted indeed to indicate a possible coup against Timor. However nothing happened.

In December, 6, 1941 HrMs De Ruyter and her destroyer escort were anchored in position near the Paternoster Islands. On the 8th, Japan declared war officially with the USA and the Britush Empire, and the Dutch Government in exile followed suite. Northing happened at first. By December, 15, the cruiser met the rest of the KNIL fleet on the central Java sea, after which they steamed together to the Koemai Bay, in Southwestern Borneo. There, the following day a conference was held between Doorman and all captain present to define the KNIL strategy to face the Japanese.

On December 18, in preparation to the future battles, HrMs De Ruyter entered Soerabaja for an overhaul, notably for her worn out boilers. This done, she left the drydock and the following day Doorman met Rear Admiral Glassford (CinC TF-5) to devise cooperation plane, setting the bases for the future ABDA squadron.

On December 26, HrMs De Ruyter went at sea with Tromp and the destroyers Banckert and Piet Hein and in January 1st, they made a rendez-vous at sea with a convoy bound to Singapore, BM-9A under command of HMAS Hobart’s captain. They are escorted from Soenda Strait to the northern entrance of Bangka Strait. Three days later, they escorted back the same convoy (BM-9B). On January 10,

the cruiser escorted yet another convoy, DM-1, through Banka Strait. Nothing much happened until February 2, when HrMs De Ruyter was sent to take position near the Gili islands, Madoera Strait with other Dutch warships.

During the night of February 3/4, other ships arrived, creating a sizeable fighting force: In addition to the Dutch cruisers De Ruyter and Tromp, USS Houston (heavy) and Marblehead (Light) cruisers plus 7 destroyers (USS Stewart, Edwards, Barker, Bulmer in addition to the Dutch Banckert, Piet Hein and Van Ghent). This naval squadron left the Gili’s to intercept a IJN convoy signalled heading for Macassar leading to the cruiser’s first naval battle.

Battle of Macassar Strait

On February 3, Doorman led his squadron to intercept the Japanese invasion force underway to Macassar. En route, his flotilla was spotted by the Japanese observation planes and later bombed and strafed, eventually forced back after several ships were damaged. This event was also called the Battle of the Flores Sea.

Battle of Badung Strait

On 18 February, The Imperial Japanese Army this time invaded Bali, a strategic position in the East Indies. Doorman knew he has to act, and he led the same squadron in an attempting to intercept the invasion the next day. However all the forces he could muster were in repairs and not available, so he planned three waves in order for the others to catch up.

The first wave involving his ship, and also the cruiser Tromp and four destroyers. However the first to attack were the submarines USS Seawolf and HMS Truant, already in position. They torpedoed the convoy on 18 February, but made no damage (perhaps again because of torpedo failures), and were driven off by depth charges, from Japanese destroyers. The next “wave” was 20 planes of the UUSAAF stationed in the Dutch Netheralands East Indies, which bombed and strafed the convoy, consistin of two transports escorted by four destroyers, but succeeded only in damaging Sagami Maru. Sasago Maru was escorted by IJN Asashio and Ōshio and Sagami Maru by IJN Michishio and Arashio.

The convoy, knowingly in trouble, retreated north as soon as possible. The only possible reinforcements were the cruiser IJN Nagara and destroyers Wakaba, Hatsushimo and Nenohi, well away.

HNLMS De Ruyter and Java were ecorted by the USS John D. Ford, USS Pope, and the Dutch HNLMS Piet Hein. Thy eventualy spotted the Japanese in Badung Strait as planned, at about 22:00. They immediately open fire when on range, at 22:25. It was the 19 February. Darkness fell and the fire was innacurate, they hit nothing, but went on through the strait and northeast, give the destroyers a free hand to engage the convoy in a torpedo attack. Piet Hein, Pope and John D. Ford closed to range bu at 22:40, before they launched, Piet Hein was hit by a “Land Lance” from IJN Zrashio, and sunk immediately, broken in two. Asashio and Oshio started a gunfire battle with Pope and John D. Ford, forcing them back eventually before they could launch their torpedoes. They retired to the southeast, splitting from the cruisers. In complete darkness, Asashio and Oshio mistook each otherand started a friendly fire, before realizing their mistake.

Three hours later, the second group ABDA wave, the cruiser HNLMS Tromp and destroyers USS John D. Edwards, Parrott, Pillsbury and Stewart also arrived at the Badung Strait. At 01:36, the destroyer went in torpedo range and launched, but hit nothing. Oshio and Asashio closed in and fired. During the gunfight, in which participated Tromp, the latter was hit by eleven 5-in (12.7 cm) shells from Asashio, but she also hit both Japanese destroyers, with light damage. Tromp was obloged to leave the area and sail to Australia for repairs, no longer seeing action in the East Indies.

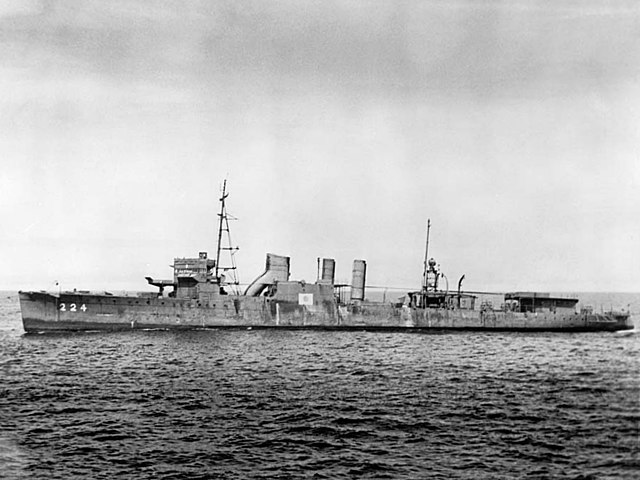

IJN Asashio

Arashio and Michishio were ordered in the meantime by Admiral Kubo to retire but at 02:20, Michishio was hit by USS Pillsbury, John D. Edwards and Tromp. She lost 13 of her crew, with 83 wounded, loosing speed until going into a full stop. She was later towed out. USS Stewart was also damaged, having a flloded steering engine room. Both destroyer groups part away, putting an end to the battle.

The third ABDA wave (seven torpedo boats) arrived at 06:00 but by then the Japanese had retired. All in all this was a tactical viictory for the latter. Lt. Cdr. Gorō Yoshii (Asashio) and Kiyoshi Kikkawa (Oshio) were later awarded for gallantry by driving off a much larger Allied force and sinking Piet Hein, badly damaging Stewart and Tromp. Their transport ships arrived safely.

Bali’s small garrison fell, with the airfield, captured intact. This boosted the conquest of the Dutch East Indies, as soon Timor fell on 20–23 February. The ABDA squadron wasfinished off later in March, Tromp remaining as the last important KNIL vessel to survive.

A badly damaged Tromp, in Australia for repairs (AWM)

Battle of the Java sea

On February 27, 1942, HrMs De Ruyter, as flagship of the international squadron (ABDA), participated in the Battle of the Java Sea. Rear admiral Karel Doorman was on overall command, onboard the cruiser. HrMs De Ruyter conducted the squadron in search of the IJN squadron escorting the invasion fleet.

The Japanese amphibious forces were to land directly in Java, seizing the remaining hart of the Dutch East Indies. On 27 February 1942 the main Allied naval force (ABDA) under Doorman, sailed northeast from Surabaya in an intercept course, as the IJN approached from the Makassar Strait. The ABDA was split into the Eastern Strike Force, with the heavy cruisers HMS Exeter and USS Houston, three light cruisers (HNLMS De Ruyter, Java, and the Australian HMAS Perth), protected by nine destroyers (HMS Electra, Encounter, Jupiter, HNLMS Kortenaer, Witte de With, and USS Alden, John D. Edwards, John D. Ford, and Paul Jones).

Opposing this, the IJN (Rear-Admiral Takeo Takagi) were led by the heavy cruisers IJN Nachi and Haguro, light cruisers Naka and Jintsū, and 14 destroyers: IJN Yūdachi, Samidare, Murasame, Harusame, Minegumo, Asagumo, Yukikaze, Tokitsukaze, Amatsukaze, Hatsukaze, Yamakaze, Kawakaze, Sazanami, and Ushio (4th Destroyer Squadron, Rear Admiral Shoji Nishimura).

The Allied force arrived in range, spotting them underway in the Java Sea, and a long range gunnery duel started intermittently from mid-afternoon to midnight. Each time the De Ruyter and Perth tried to close in, they were repulsed by 8-in shells. The Japanese had a much longer range. The Allies however had local air superiority and during the day, launched several attacks despite the bad weather, which also hindered communications, so allied coordination was poor, compounded by the Japanese that also jammed radio frequencies. HMS Exeter was the equipped with a radar.

For seven hours, Doorman’s Combined Force tried to hit the invasion convoy but was rebuffed and hit.

At 16:00 on 27 February contact was made again, gunfire started at 16:16. but it seems after post-battle reports that both sides showed poor gunnery skills. Exeter’s shells misses each time, while USS Houston only managed a near-miss on a cruiser. Exeter was soon critically damaged in the boiler room and limped away to Surabaya escorted by Witte de With.

The Japanese launched massive torpedo salvoes (92 torpedoes) to only score a hit on Kortenaer. She broke in two and sank rapidly.

HMS Electra, which covered Exeter duelled with Jintsū and Asagumo, but was badly damaged and later abandoned. Asagumo was also badly damaged and retired to safety.

Type 93 “long Lance” torpedo

The Allied broke off eventually, turning away around 18:00, covered by a smoke screen from USN Division 58 (DesDiv 58), launching a torpedo attack at too much range to make any hit. Doorman decided to tur south, towards the Java coast. As nioght fell, he then turned west and north, in an attempt to evade the Japanese escort group, and later manage to surprise the convoy. DesDiv 58, short of torpedoes and low on ammunition decided onn their own initiative to return to Surabaya, leaving the force.

At 21:25, HMS Jupiter hit a mine and sank, and 20 minutes later and HMS Encounter left the group to rescue survivors, again halving the destroyer force.

Doorman now had four cruisers under ordered, and spotted at last the Japanese escort group at 23:00. Gunfire started again, both side exchanging at long range, keeping De Ruyter and Java busy. What they could not see was a massive wave of long-land torpedoes coming their way. De Ruyter was hit by one, and sank immediately with most of the crew, as Java. The captain ordered to abandon ship but only 11 of the crew were later rescued. Doorman, which could have survived, as the captain, decided to go down with the ship.

Now ABDA was reduced to HMAS Perth and Houston, and both, now low on fuel and ammunition retired to Tanjung Priok on 28 February.

Only in 2002 the wreckage of Hr.Ms. De Ruyter found at the bottom of the Java Sea. During an expedition at the end of 2016, it turned out that the wreck had been looted (like most of the ABDA wrecks) and the ship was presumably removed from the seabed and sold by salvagers with grabs.

IJN Haguro, which torpedoes likely sunk HLMNS De Ruyter

It seems as a conclusion that, indeed, De Ruyter was not up to the task to face two IJN heavy cruisers. Each had ten (5×2) 8-in guns that clearly outranged and outmatched the seven 15 cm Bofors of the De Ruyter. The broadside itself was more that twice as heavy. ASW protection (and overall protection by the way) of the cruiser was decidedly poor. The IJN cruisers were better in that regards, but still, 6-in shells could have done damage. However during the day, the weather was poor and accuracy suffered as a result. During the night, without radar, there’s little De Ruyter could do. In the end, the allies never could have imaging the range and explosive power of the Japanese “long lance” torpedo, essentially a secret weapon, like the Yamato. The poor ASW protection of the De Ruyter was no match, and spotting by night the trail of bubble, especially of the weather was still cloudy, was nearly impossible, moreover with the blinding flashes of the guns firing. No one could even suspect watching for such trail of bubbles as the range was considerable, already at the limit of De Ruyter’s gunners.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign