Best Italian cruisers ever ?

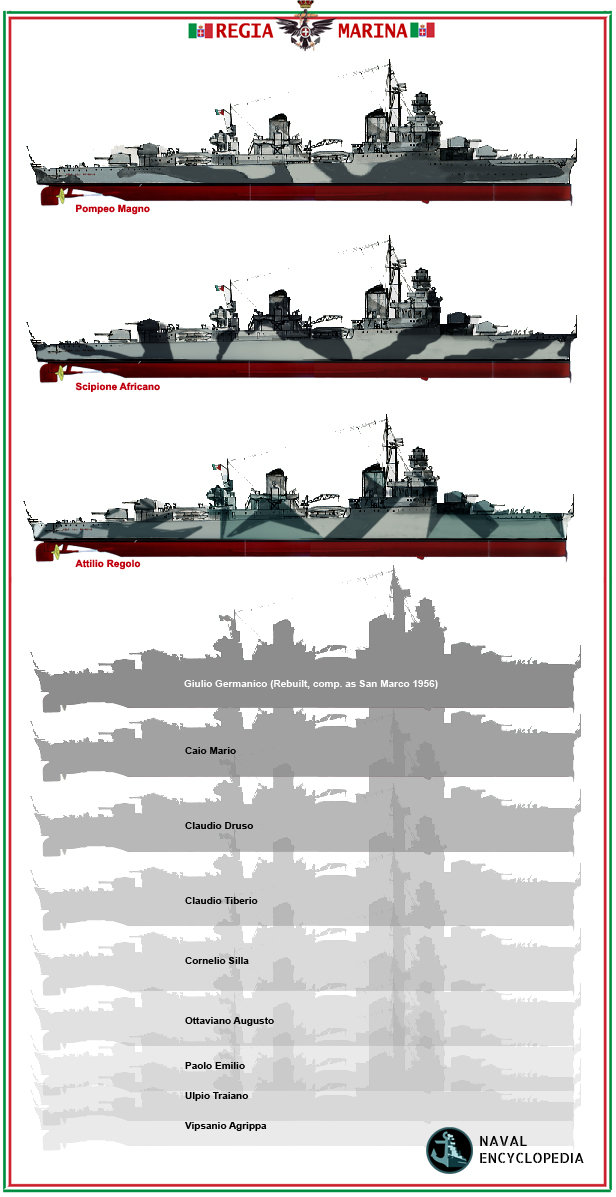

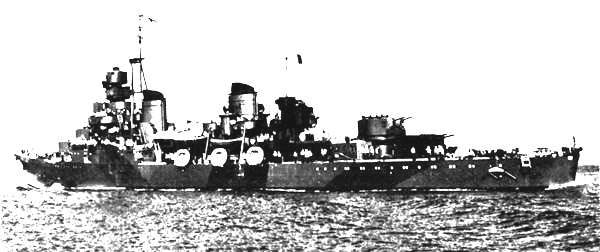

The Capitani Romani-class was a class of light cruisers acting as flotilla leaders for the Regia Marina (Italian Navy). They were built to outrun and outgun the large new French destroyers of the Le Fantasque and Mogador classes. 12 hulls were ordered by late 1939, but only four were eventually completed, and three before the Italian armistice, September 1943, with just two active before the end of the war. The class name is an historian commodity as all were named after prominent Ancient Romans Generals or statesmen “capitani” having a broader sense here. Only two ever saw little service until the capitulation. After the war, these same ships, spared destruction, were reclassified as flotilla leaders or “caccia conduttori”, and later modernized, but under French flag as per peace treaty conditions and war damage attributions.

Concept development

For the general context back in 1937, The heavy French destroyers still posed a threat to Regia Marina. The last ones, those of the Mogador and Fantasque class were not answered, and thus was the ideao to develop a a “Super Destroyer” a concept well beyond Flotilla Leaders, but scaled almost like a light cruiser, but still the same DNA as a regular destroyer. During the 1930s, the concept was reinterpreted, and between high speed, light protection, same torpedo armament as a destroyers, they were always heavily armed as for main artillery with four twin turrets. The Soviets had the Kiev and Tashkent (built in Italy), the British Royal Navy Cossak class, arguably, and the Japanese Akitsuki class. They were not comparable to a close, but different concept that was the AA cruiser, like the the Dido and Atlanta classes in 1940.

In reality, officially, these “Capitani Romani” (at the insistance of Mussolini, like an echo to the “Condotierri”) class were designed as scout cruisers, for long range oceanic operations and dubbed esploratori oceanici. Some authors still would consider them as heavy destroyers, broadly similar to the German “Spahkreuzer” project.

Design-wise they were almost unarmoured hulls with a large powerplant able to bring them to 40 knots and more, but still with a light cruiser style armament. The original design was modified during their early conception in 1938 as prime requirements of speed and firepower changed.

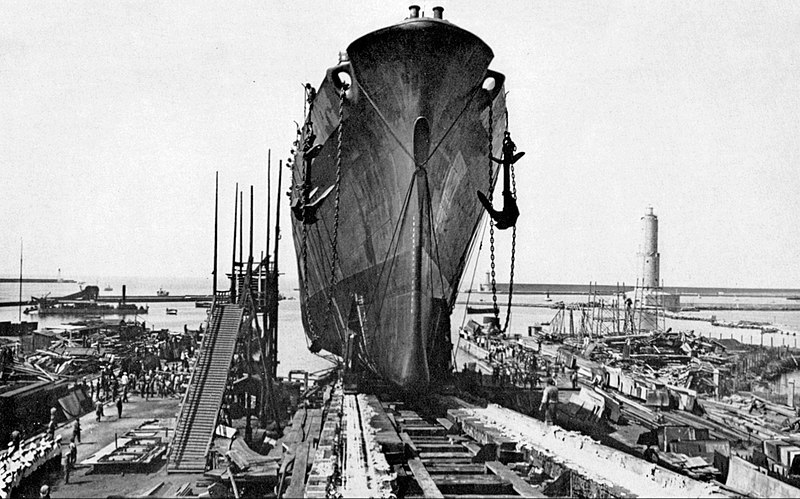

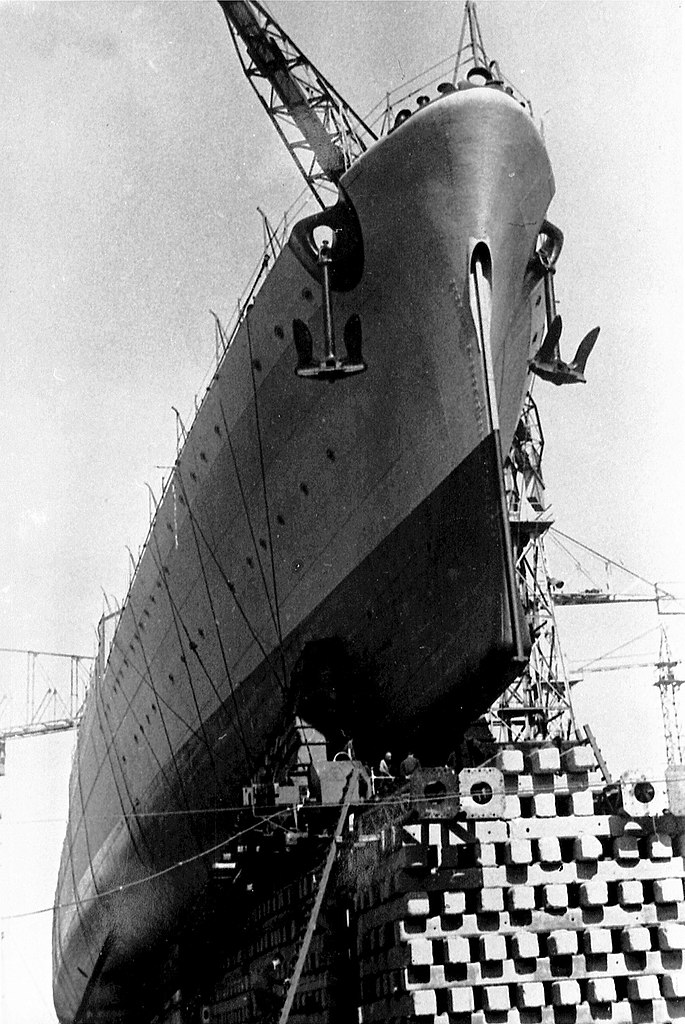

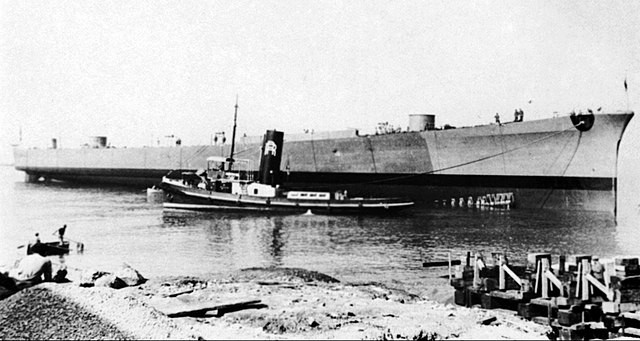

The launch of Attilio Regolo in 1939

The speed was, as for the first “Condottieri”, an important motivation, the Guissano class and the new specifications included the possibility of exceeding 41 knots. With limited movement and poor protection of the engine room, these ships had to be able to catch and destroy enemy destroyers and escape cruisers. They were armed with the , semi-automated and fast 138 mm model 1939 guns shared with the Commandante Medaglie d’Oro class destroyers, which construction just started. for the rest, their configuration was that of large destroyers, with two quadruple axial torpedo banks and powerful AA armament. ASW armament was present, but more of an afterthought, and no radar (in 1938). However this would change.

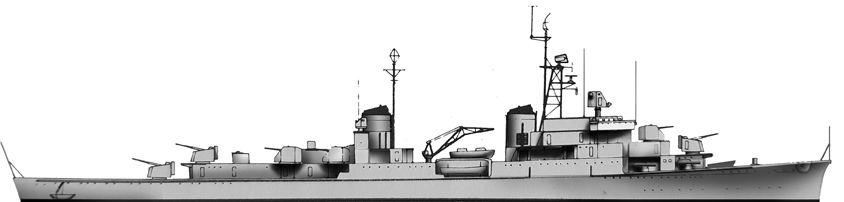

Design of the “Capitani Romani” (1939)

Rendition of the “Regolo class” USN intel – ONI. Note the very different shape of the bridge among others. Quite off the mark here for naval recoignition.

Based on these previous estimates, the final design was approved in 1939. Umberto Pugliese and Ignazio Alfano worked on this design, with work starting in 1938, from the Italian-built Tashkent for USSR by Odero-Terni-Orlando (OTO shipyard) in Livorno. The hull was flush deck, with a central superstructure incorporating a tower, the first of two funnels and the tower bridge supported the main fire direction center, followed by a foremast, a pole as designed, but which was later in production replaced by a tripod in order to support the upcoming Gufo radar system. The two funnels were widely spaced apart, having straight lines.

Around the aft funnel were grouped the night projectors, and AA mounts. The service boats were stacked abaft and behind the forefunnel, with a walkway above the fore torpedo tubes bank. Right behind the forefunnel was installed the aft fire control director. The second torpedo tube bank was installed aft of the aft funnel complex, also centrline, again topped with a walkway. The rear superstrcture was short and only contained the upper “X” turret.

Powerplant

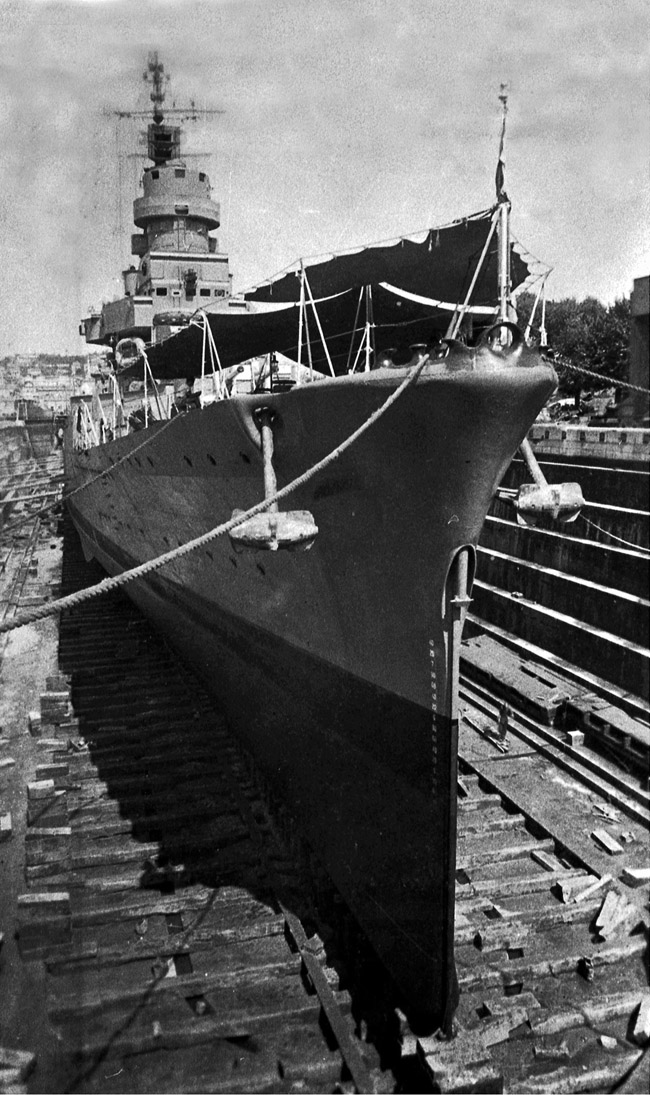

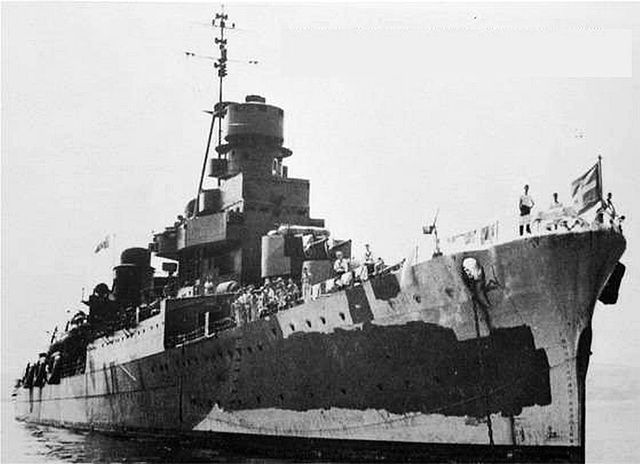

The very “sharp” prow of Africano. No doubt they would reach 43 knots or more.

The very “sharp” prow of Africano. No doubt they would reach 43 knots or more.

The machinery was well served by a fine, about 10:1 ratio like destroyers. The powerplant comprised four vertical water tube boilers, each arranged in its own room; Steam came to two sets of Belluzzo turbines, driving two shafts ended by 4.20-meter diameter three-blade propellers. Each group of two boilers operating a turbo-reducer group, consisting of a high-pressure turbine and two low-pressure turbines for more versatility.

Their machinery reached in the end a phaenomenal 93,210 kW (125,000 hp). To put this into perspective, this was the same as the 17,000-ton Des Moines class heavy cruisers !. Top speed as planned was 41 knots (76 km/h; 47 mph) but of course at the price of no protection. Eventually, they did managed even better in trials, easily reaching 43 knots (80 km/h).

The interwar Italian craze for speed was confirmed again. Basically it was logical, as they were supposed to replaced the 1920s Cadorna class, also designed to be “destroyer hunters”. Wartime load made them of course slower, generally 1.9 to 9.3 km/h or 1.2 to 5.8 mph, although in mission, Scipione Africano, while still fully loaded even managed to peak over 43 knots, so much faster than any British destroyer.

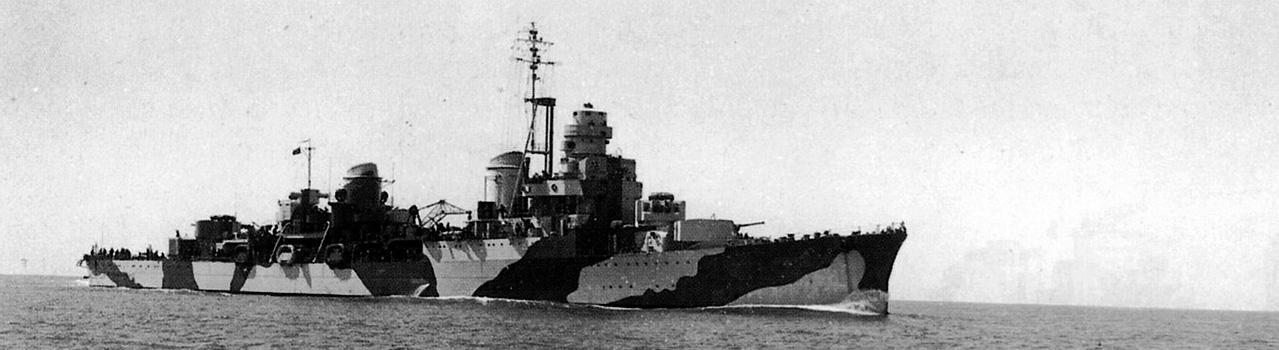

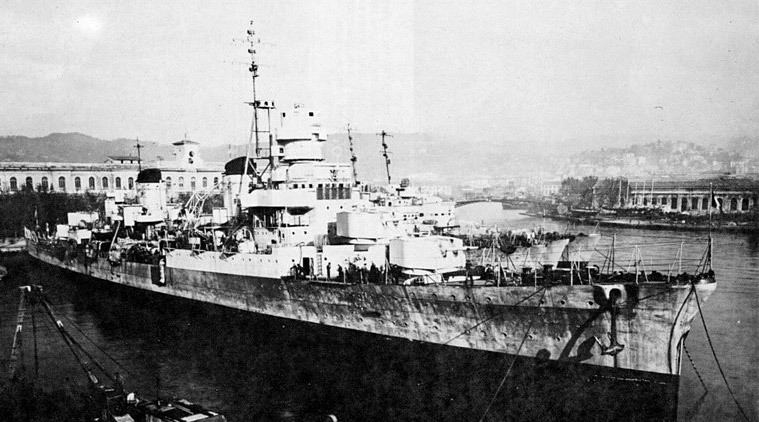

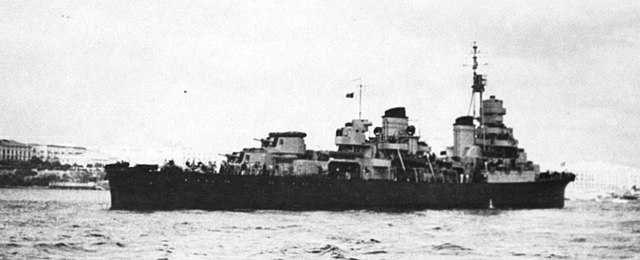

Regolo -official profile photo, just camouflaged.

Armament

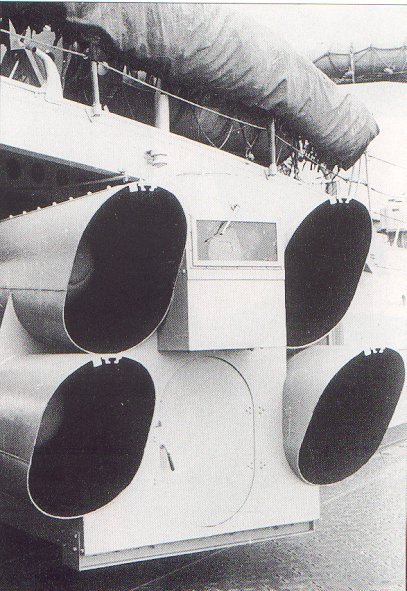

Main turrets on Africano

Main turrets on Africano

Main 4×2 135 mm (5.3 in) DP Modello

The Capitani Romani-class’ main battery consisted of eight 135 mm (5.3 in) DP guns. They had a rate of fire of 8 rounds a minute, for a range of 19,500 m (21,300 yd). These 135/45 mm gun were considered the best Italian naval gun of World War 2. They had a 45° elevation and a 19.6 km range, were capable of a 8 rounds per minute ROF, and were very accurate with a dispersion 25% lower than the old 120mm/50 models. Still, they lacked a satisfactory anti-aircraft amunition and direction foor an effective barrage. They were made by OTO and Ansaldo and accuracy was helped by their placement in separate cradles, greatly improving accuracy by lack of interference when firing.

More on navweaps.

Torpedoes: 2×4 533 mm (21 in) TTs

This secondary heavy armament comprised two axial quadruple torpedo tubes, with no less than eight 533 mm (21 in) launched in a single volley, and more reloads than on an average destroyer. The model was the 53.3 cm (21″) Si 270/533.4 x 7.2 “M” built at Naples (Silurificio Italiano). It was shared by most interwar and ww2 destroyers and cruisers. It is unsure when it was introduced, likely 1936, and Weighted 3,748 lbs. (1,700 kg) for an overall Length of 23 ft. 7 in. (7.200 m). Each carried a 595 lbs. (270 kg) warhead at 4,400 yards (4,000 m)/46 knots (setting 1) or 8,750 yards (8,000 m)/35 knots or 13,100 yards (12,000 m)/29 knots, Powered by a Wet-heater. Later versions, those used on the Capitani and Medaglie d’Oro class were 48 knots, 38 knots and 30 knots settings speeds respectively.

AA armament:

-Eight single 37 mm (1.5 in) AA guns: These were the standard Breda type, which needed a crew of three to operate.

The anti-aircraft armament, after the forced renunciation of the new 65/64 mm anti-aircraft guns, consisted of eight Breda 37/54mm in eight individual mounts, particularly useful against torpedo bomber attacks, and against low altitude targets.

More on navweaps

-Four twin 20 mm (0.8 in) AA guns. These eight 20mm/70 Breda guns, in four twin mounts were located on raised platforms around the aft funnel. They proved themselves well, easy to use and maintain, and could fire tracer, tracer-explosive, ultra-sensitive, disruptive rounds, widespread on the Regia Marina. The eight 37/54mm mounts were located on the sides of the bridge deck, plus two abreast the aft turret. The four 20 mm twin mounts

More on navweaps

Mines:

All these cruisers were designed as minelayers with two rails running on the weather deck to the forward superstructure to the stern, with chutes. 70 mines were carried, of an unknown type. Could be the Pignone Elia 145/1930 Elia, the more recent 1936 P200 (P5) or Bollo P125/1935. They had no ASW installation.

First Italian cruiser completed with radars:

Close view of the bridge and FCS atop. Note the tripod with a platform for the Gufo radar, not yet installed.

Close view of the bridge and FCS atop. Note the tripod with a platform for the Gufo radar, not yet installed.

The Capitani Romani class received the EC-3/ter Gufo radar.

This 10 kw unit worked on a 400 – 750 MHz frequency with a PRF of 500 Hz, a Beamwidth of 6° (horizontal) and 12° (vertical), a Pulsewidth of 4 μs and 3 rpm, for a range of 25 up to 80 km (50 mi).

Author’s profile of the Scipione Africano class

⚙ Capitani class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 142,90 m long, 14,40 m large, 4,90 m draft |

| Displacement | 3 680 t. standard -5 334 tons Fully Loaded |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft Belluzo turbines, 4 Thornycroft boilers, 110,000 hp. |

| Speed | 40 knots (42+ trials) () |

| Range | 2300 nm @ 30 knots. |

| Armament | 8×135 mm (4×2), 6x37mm AA, 8×20 mm AA, 8 533mm TTs |

| Protection | Turrets: 6–20 mm (0.24–0.79 in), Conning tower: 15 mm (0.59 in) |

| Crew | 420 |

View from the open control bridge

The ‘Capitani’ in the cold war

San Marco class

San Marco, D563 in 1959

Giulio Germanico and Pompeo Magno were completely modernized for the Marina Militare: Germanico became San Marco (D 563) and San Giorgio (D 562) reclassified as destroyer leaders. Both ships were extensively rebuilt between 1951 and 1955 US weaponry and radar typical of the time:

-Six 127 mm (5 in) guns (twin turrets) for ‘A’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ turrets,

-Menon anti-submarine mortar (in lieu of ‘B’ turret)

-Twenty 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors AA guns

-Sensors: Radars SPS-6 and SG-6B radar, SQS-11 sonar, Mk37 fire control system.

San Marco later became a cadet training ship, rebuilt in 1963–1965 with a brand new CODAG machinery for extra range (thrice). She was also fitted with new 76 mm (3 in) OTO Melara guns in place of all 40 mm artillery and ‘X’ (rear) 5-in turret. She was decommissioned in 1971, but San Giorgio served for another decade, until 1980, making one of the oldest ship in the Marina Militare since she was laid down in 1939, 41 years.

French Chateaurenault class

Chateaurenault

Chateaurenault

The two ex-Attilio Regolo class cruisers Scipio Africano and Attilio Regolo were attributed to France in 1948. They were converted in fast ASW/AA escort cruisers for the french task forces. Conversion started after some design work in 1951 at La Seyne NyD, completed by 1954. They were re-commissioned as Chateaurenault and Guichen dubbed “escorteur d’escadre” (litt. “squadron escort”) like the T47 class destroyers. They received initially three twin 105 mm mounts of the same type used on German capital ships and cruisers in a superfiring pair aft and a single forward. The rest comprised French twin 57 mm M1951 in fwd “B” positio or behind the rear funnel, new fire directors and radars. For ASW warfare four triple 550 mm acoustic TTs (12 in all !) were installed forward, close to the forward superstructure and they had a short lattice mast for the heavy DRBV11 surface radar plus the DRBV 20A.

They acted as command ships for squadrons and ultimately lost their aft deck 105 mm mount and TT banks for extra accomodation. They were stricken sooner than the Italian vessels, in 1961.

Profile of the Guichen class in French service

Profile of the Guichen class in French service

General Assessment

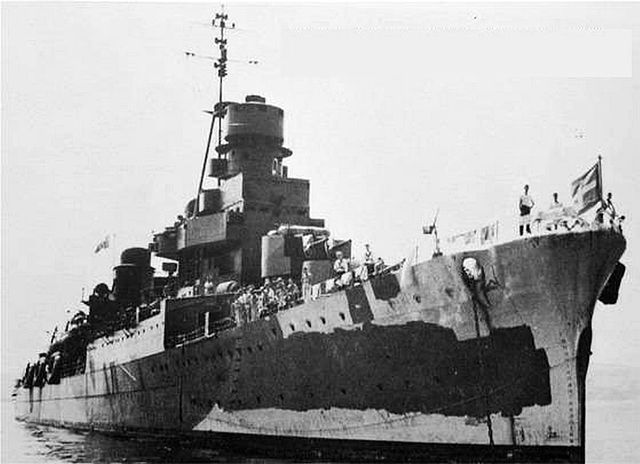

Regolo underway, leading the destroyers Mitragliere, Fuciliere and Carabiniere

With the combination, of very high power and fine lines giving them an unprecedented top speed, even maintained in combat load, acurate and modern armament, including good AA, and radars for the first time, the Regolo class (or ‘Capitani’) could well be, arguably, called the best Italian cruisers of WW2.

The only relatively grey spot on this assessment would be their late arrival into the fight for the Regia Marina. Most of the major battles were over in the Mediterranean, after Torch and the evacuation of Sicily Italy was down to defend Sicily when they arrived, and with the combined naval and air power of the allies, Mussolini’s dream of an “Italian lake” was definitively buried. The three active vessels of the class nevertheless, saw their fair share of action, single-handely defeating motor torpedo boats which were equally agile and very fast, with skills and accurate, combined rapid fire by night. This performance likely bought back the humiliation the battle of Cape Bon, when the two light cruisers they were supposed to replace were sunk by a destroyer squadron. They too were fast, but lacked awareness (not radar, near complete surprise) a good, accurate main battery and fire density.

The “Capitani” also proved the worth of their AA when Africano repelled several allied air attack, including one that could have put the Italian government in immediate danger, and showed their versatility by laying minefields which had the effect of deterring the allies to stop the axis evacuation of Sicily, ensuring prolongated, fierce fighting in Italy in the upcopming months and years.

The Capitani Romani were thus, the perfect replacement needed for the early six Condotierri class, but they arrived far too late.

The allies neever gave them another chance to fight, this time the Germans, and they spent the rest of their career of co-belligerence as transports.

However as a testiment to the qualiy of the ship in general, adaptability and longevity, four of them would serve for more than half of the cold war (even 1980 for one), proving they could be modernized in completely different configurations and for many roles.

Now for a bit of “what if” and alternate history, they were probably be the concrete realization of the “spahkreuzer” the Kriegsmarine dreamed of in Plan Z, either for the Baltic or north sea. They would have excelled by hunting down northern route convoys from Norway, hitting hard and leaving all allied destroyers behind. Would they had been laid down instead in 1937 and all twelve available in 1940-41, no doubt the Mediterranean campaign could have turned differently as well for supermarina.

Gallery

Attilio Regolo

Scipione Africano, date unknown

Read More

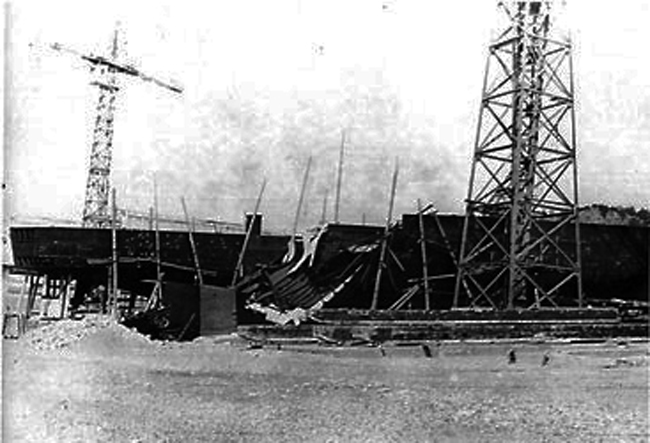

The prow of the unifinished Ottaviano Augusto in CNR Ancona before launch

Books

Robert Gardiner, Roger Chesneau Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

Elio Andò, Incrociatori leggeri classe “CAPITANI ROMANI”, Parma, Ermanno Albertelli Editore, 1994

Piero Baroni, La guerra dei radar: il suicidio dell’Italia : 1935/1943, milano, Greco e Greco, 2007

M. J. Whitley, Cruisers of World War Two – an international encyclopedia, Londra, Arms and Armou, 1996

Gino Galuppini, Guida alle navi d’Italia : dal 1861 a oggi, Milano, A. Mondadori, 1982.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina Militare nel suo primo secolo di vita 1861-1961, Roma, Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, 1961.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina dall’8 settembre alla fine del conflitto, Roma, Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, 1971.

Raffaele de Courten, Le Memorie dell’Ammiraglio de Courten (1943-1946), Roma, Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, 1993.

Pier Paolo Bergamini, Le forze navali da battaglia e l’armistizio, in supplemento “Rivista Marittima”, n. 1, gennaio 2002, ISSN 0035-6984 (WC · ACNP).

Links

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classe_Capitani_Romani

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Capitani_Romani_class_cruiser

https://www.marinaiditalia.com/public/uploads/2011_04_30.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20120902074447/http://www.regiamarinaitaliana.it/Inc%20Cromani.html

https://digilander.libero.it/planciacomando/dopog/fra.htm

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attilio_Regolo_(incrociatore)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scipione_Africano_(incrociatore)

Model Kits

The Capitani Romani: Construction, fate and career

In construction from 1939, the 12 ships were delayed with the start of the war catching them in June 1940: Only eight of them were launched, and three completed, RN Attilio Regolo in May 1942, RN Scipione Africano in April 1943 and RN Pompeo Magno in June 1943. Giulio Germanico was completed after the war while Pompeo Magno was completely modernized and renamed, and remained in service until 1964 and 1971 respectively. The other two became war reparation to France in 1948 (Guichen and Chateaurenault). Only Scipione Africano and Attilio Regolo saw combat.

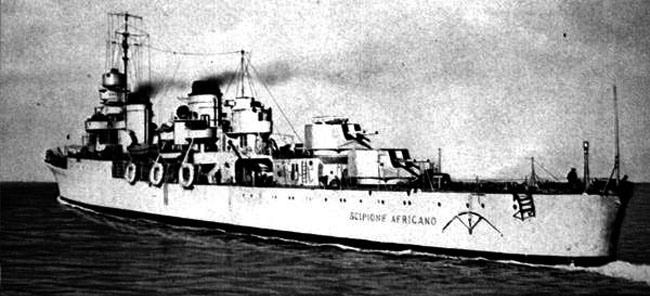

Scipione Africano

Scipione Africano

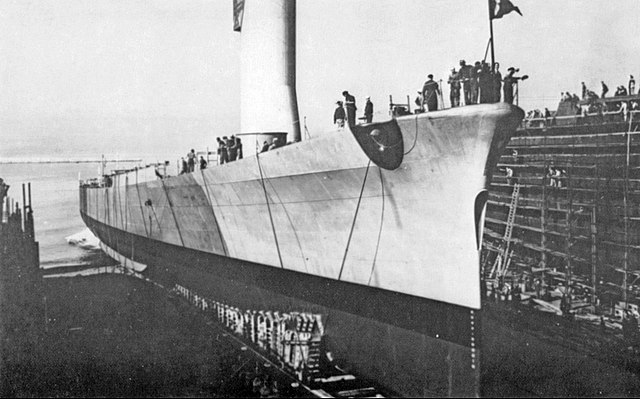

Construction of Africano in Livorno

Construction of Africano in Livorno

This cruiser was named after general Scipio Africanus, which vanquished Hannibal at Zama. She was laid down at O.T.O., Livorno on 28 September 1939, launched 12 January 1941, completed on 23 April 1943 under command of Ugo Avelardi. Next she had Captain Ernesto De Pellegrini Dai Coi in command from 24 February to 25 March 1943, and from there, Frigate Captain Umberto Del Grande from 26 March to 5 May 1943, and Frigate Captain Ernesto De Pellegrini Dai Coi from 6 May 1943.

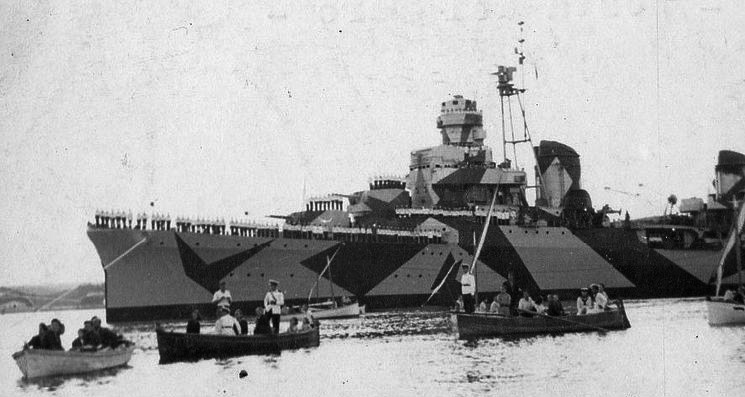

Scipione Africano in sea trials, not yet camouflaged.

Her most famous engagement arrived when she detected and engaged four British Elco motor torpedo boats in the 16-17 night of July 1943 en route to Taranto. It happened while crossing the Messina straits at high speed, off Punta Posso. She sank MTB 316 and heavily damaged MTB 313 between Reggio di Calabria and Pellaro:

Scipione Underway at sea

Scipione Underway at sea

After the Allied landing in Sicily (Operation Husky), and anticipating of a possible blockade by the Allied part of the Strait of Messina, she was sent to force the Strait and reach Taranto, going also from the Tyrrhenian to the Ionian sea, Operation Scilla. She left La Spezia at 6.30 am on 15 July 1943, under the command of the vessel captain Ernesto De Pellegrini Dai Coi from Naples. Africano was by then equipped with the EC3/ter Gufo radar and proceeded through the strait at 02.00 on 17 July and detected off the Calabrian coast near Capo Pellaro, four Elco type motor torpedo boats, MTB 260, 313, 315 and 316 from 10th Flotilla sailing from Augusta and on patrol south of the Strait. They spotted the cruiser in returned and attacked immediately.

Africano’s captain took action, and moving away at high speed, dodging incoming torpedoes while opening fire with her main artillery even her 37 and 20 mm at this range. She was deadly accurate, and soon hit all four MTBs, left them afire behind at full speed, arriving unscaved in Taranto. All in all, she sank one MTB and damaged two others. Her commander and crew were publicly praised by Admiral Bergamini on 18 July 1943.

On 4-17 August Scipio made several mine-laying missions in the Gulf of Taranto and off the coast of Calabria, escaping each time Allied planes attacks. Her actions allowed to crteate a safe “corridor”, deterring the allies to attack the retiring Italo-German forces from Sicily. The four minefields in the Gulf of Taranto and Gulf of Squillace were laid with RN Luigi Cadorna.

On the evening of 8 September, the armistice was heard via radio and while in Taranto around 6 am on 9 September, she received orders to reach Pescara asap, escorted by the Gabbiano-class corvettes Scimitar and Baionetta from Brindisi and Pola and meeting underway. At around 2:00 pm while off Capo d’Otranto at 28 knots, she spotted the German S-Boats S 54 and S 61 approaching fast. However, fearing the guns of Africano, they suddenly created an artificial fog curtain and declined action, just maneuvering to get away. Commander Ernesto Pellegrini went on afterwards towards Pescara without other incident.

Scipione Africano arrived shortly after midnight there, with the corvette Baionetta (Lt. Piero Pedemonti) which had on board the Badoglio government and Minister of the Navy De Courten. She however refuelled and went on to Ortona and embarked the royal family on the 10th soon rejoined by Africano as escort. They reached Brindisi, and King Vittorio Emanuele III with his entourage disembarked around 4 pm, hosted by Admiral Rubatelli.

The other corvette Scimitar arrived in Pescara from Brindisi (Lt. Vascello Remo Osti) on the early morning on 10 September,proceeding to Taranto the following day. Six allied fighters were spotted incoming over Brindisi, but they were deterred by a vigorous AA defence of Scipio Africanus and the corvette.

Africano with her Co-belligerence livery, 5 May 1943

On 29 September, Scipio escort Marshal Badoglio and part of government officials to Malta for signing the armistice treaty with General Eisenhower on board HMS Nelson, following the ceasefire of 3 September agreed by General Giuseppe Castellano. The cobelligerence saw Africano in the same role as other cruisers of her class, making transport trips to Alexandria and the Bitter Lakes were eventually Italian battleships were interned, notably the modern RN Vittorio Veneto and Italia. She proceeded to other missions until 1945, under command of Captain of the Libero Chimenti (22 March 1944-31 January 1945), Riccardo Imperiali de Francavilla (1 February-21 March) and eventually Emilio Francardi (22 March-31 August 1945), until she was interned, and later attributed to France for war reparations, as Guichen.

Attilio Regolo

Attilio Regolo

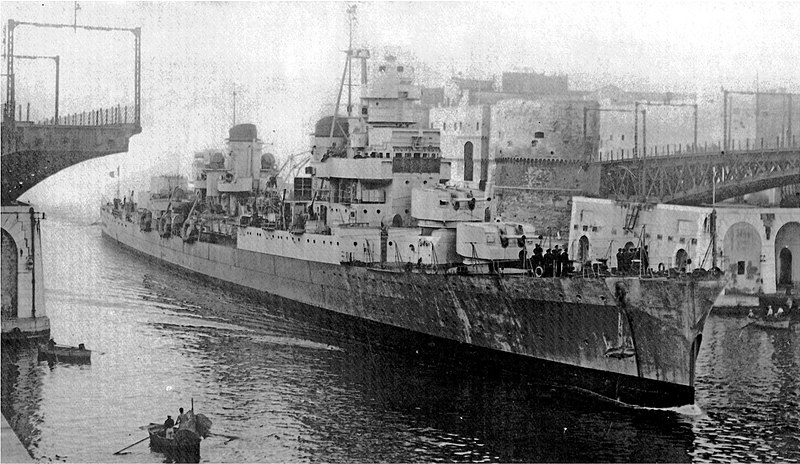

Regolo in Livorno, May 1942

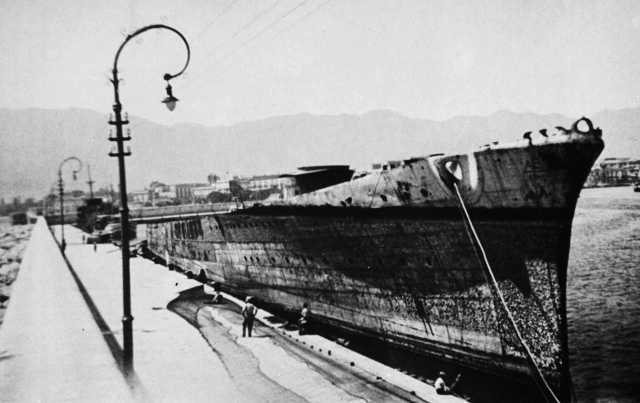

RN Attilio Regolo was named after Marcus Atilius Regulus (statesman and general in 267 BC-256 BC of 1st Punic war fame) at O.T.O., Livorno, laid down on 28 September 1939, launched on 28 August 1940 and completed on 15 May 1942, but commissioned in August 1942 under command of Vessel Captain Pietro Sandrelli (14 May-10 October 1942). She was fitted like the others to be used as a minelayer, a mission she performed under orders of frigate Captain Umberto di Grande, until seriously damaged by a torpedo in November by the submarine HMS Unruffled on 7 November 1942. Her bow was severed by the blast, but she managed to limp back and to port, with some help. She managed to reach Messina, and was towed to La Spezia, where she remained in drydock for several months with her bow repaired, with the intact prow of Caio Mario, still under construction.

To Captain Umberto Del Grande, leaving on 31 January 1943 succeeded Lieutenant Dario Salata, responsible for the repairs until recommission in La Spezia, from 1 February to 17 May 1943.

Regolo with her destroyed bow

According to some sources, in the summer of 1943 she received her intended radar EC.3ter Gufo. She was completed after the allied landing in Sicily, and only returned to service on 4 September 1943, under orders of frigate Captain Marco Notarbartolo di Sciara. On the 8th she was still in La Spezia, as part of the VII Division with Montecuccoli and Eugenio of Savoia, the latter being flagship, carrying the insignia of Admiral Oliva. Admiral Bergamini warned by the Chief of Staff De Courten of an imminent armistice and possible immediate transfer of Italian ships, but most remained waiting for their destiny, obliged to raise a black flag on their masts and having black circles painted on the decks. various positions emerged, some officers wanted indeed to set sail out and to seek a final battle of to scuttle the fleet, but Bergamini took control from La Spezia and sailed to Maddalena to join the battleship Roma as flagship, followed by Vittorio Veneto and Italia as the IX Division, to be escorted by the cruisers of the VII Division,, Attilio Regolo being used as command ship of destroyers (Commodore Franco Garofalo), leading the destroyers Mitragliere, Rifiliere, Carabiniere and Velite (XII Squadriglia) and the Legionario, Oriani, Artigliere and Grecale (XIV Squadriglia) in two columns plus in vanguard the TBs Pegaso, Orsa, Orione, Ardimentoso and Impetuoso.

They met en route ships from Genoa of the VIII Division (Garibaldi, Duca degli Abruzzi, Duca d’Aosta, the latter flagship of Admiral Bianchieri)- preceded by the torpedo boat Libra. At 15.45 Roma was attacked by Luftwaffe bombers using Fritz-X guided bombs and sank after two hits in a few minutes. Admiral Bergamini with his staff went with her. Carabiniere reversed to pick up recover survivors, followed by Attilio Regolo and Carabiniere, Pegaso, Orsa and Impetuoso.

Attilio Regolo stayed behind with three ships of the XII Destroyer Squadron and torpedo boats under command respectively of captain Giuseppe Marini, and captain Riccardo Imperiali of Francavilla, staying until they recovered 622 sailors, but 1352 went to the bottom with Roma. 17 had been picked up by Attilio Regolo. Italia was also hit, but not fatally, and despite being flooded by 800 tonnes of seawater, she went on, taking command until reaching Malta, under command of Admiral Oliva on Eugenio di Savoia. There, they met the Duilio, Cadorna and her sister Pompeo Magno.

Vessel Captain Giuseppe Marini on Mitragliere, squadron leader of the XII Sqn having many serious injuries on board requested Attilio Regolo to be detached to Livorno. Evenually the formation, looking for a neutral port, headed for the Baleares, Spanish controlled. There, they would be able land the wounded sailors from Roma and resupply before heading to a place of internment. After arriving on 10 September, Regolo docked in Porto Mahon, Menorca, TBs stopping at Mallorca. The wounded and burned were disembarked, transported to the hospital.

However in the nigh of 10-11 September Regolo’s turbines were sabotaged while leaving the Spanish waters and both Pegaso and the Impetuoso, Imperiali and Fulgosi left their moorings and were scuttled, the crews interned. Commander Marini (Regolo) failed to get water and fuel oil and on 11 September failing to leave under 24 hours according to the Hague convention, were seized by order of the Spanish government. Months passed with growing tension, many ship crew members expressin their wish to join the Italian Social Republic. In January 1944, a few desertions commenced. Some stole a 14-ton fishing boat to escape, but did not survived a storm.

Regolo in Venezia, 1945

Tensions between Spanish soldiers and civilians towards the crews reach such a level, that to decrease it on 22 June 1944 Spanish authorities forced a reunion of all sailors and officers, asking them to join either the Kingdom or RSI. Voters would be repatriated across the border with France if joining the latter, or by ship via Gibraltar for the second option. Out of 1,013 voters, 994 opted to stay loyal to the King, 19 joined the RSI. The cruiser, wit a skeleton crew was at last authorized to leave Spanish waters on January 15, 1945 ad arrived in Taranto on January 23. According to peace treaty clauses, Regolo was among the units ceded as war damage to France, acted on July 27, 1948 with the initials R4. Her last captain was Marco Notarbartolo di Sciara from 18 May 1943 to 3 July 1945. She was renamed Chateaurenault in French service, until the late 1960s after reconstruction.

Giulio Germanico

Giulio Germanico

Emperor and conqueror of Germany hence the nickname (full name Germanico Giulio Cesare, 24 may 15 BC, 10 oct. 19 AD), was among the first of these cruisers started. She was started on 3 April 1939, launched on 26 July 1941 and captured by the Germans in Castellammare di Stabia while under completion (90%). She was never completed by them and instead scuttled on 28 September 1943. Instead, she was raised and completed again by the Italian Navy after the war (Marina Militare), renamed San Marco and quite modified. She served as a destroyer leader until her decommission in 1971. Her career started on 19 January 1956, she was Renamed San Marco, and served as a destroyer leader.

Pompeo Magno

Pompeo Magno

Pompeo Magno, named after Pompey the Great, Caesar’s mentor, friend and later rival, was built in CNR, Ancona, laid down 23 September 1939, launched 24 August 1941 and completed on 4 June 1943 but never fully operational. Construction at the Cantieri Navali Riuniti in Ancona was followed by a completion on 4 June 1943 and she entered service twenty days later, assigned to the Taranto base, and carrting out minelaying missions. It seems during this summer of 1943 she received the EC.3ter Gufo (“Owl”) radar but this is contested among sources. At that time, she was under command of Vessel Captain Paolo Mengarini from 24 June, until 7 August 1943 and later of Frigate Captain Alberto Banfi.

In July 1943

In July 1943

Pompeo Magno clashed in the night of 12-13 July 1943 in the Strait of Messina, with five allied MTBs apparently having intercepted her EC.3ter radar emission. This episode would prompt the Italian admiralty to limit the use of this radar. Magno however managed to locate these ships by radar, caught them and engage them in battme, sinking two in rapid succession, severely damaging a third, later sunk while the remaining two fled at full speed (which was not easy due their top speed quite close to the Romani class). When teamong with Africano, both woold repeat that feat in the night of 16-17 July with British MTBs in the same Strait of Messina but there are conflicts in logs of both ships. More likely it was the Scipio Africanus after the Allied landing in Sicily and in anticipation of a possible Allied blockade of Messina which headed full steam ahead, forcing the narrows to Taranto.

Proceeding to Malta, 9 September 1943

Proceeding to Malta, 9 September 1943

The armistice of 8 September saw pompeo Magno in Taranto with her twin Scipione Africano and Cadorna inside the V Division, escorting the battleship Duilio. The armistice caused tensions and on the 9 September, after Scipio left her moorings around 6 AM, ordered to reach Pescara, other ships were ordered to proceed to Malta. A meeting between officers favored instead a scuttling of their ships. Rear Admiral Giovanni Galati (cruiser group) simply refused to go to Malta and wanted instead to sail North, joining the axis, or to seek a last battle, but he was placed under arrest by Admiral Bruto Brivonesi, failing to convince him to follow the King’s orders of the King. However in the end loyalty prevailed and two battleships, two cruisers, the destroyer Nicoloso da Recco left Taranto, soon in sight of a British fleet which escorted a troopship convoy to occupy Taranto. Around 19:00 the Italian fleet was attacked by German fighter-bombers, Duilio having near-misses. At 09:30 AM they escort a British destroyer, and soon eight more to escort them to Malta, arriving in 17:50, mooring off Madliena Tower, they were joined by the other group from La Spezia (lossing the battleship Roma) under Admiral Oliva. Pompeo Magno soon was to depart again:

Underway in 1946

Underway in 1946

On 4 October, she sailed from Malta back to Italy, with the VIII Cruiser Division (Taranto) and on 2 February 1944 she was reassigned to the VII Cruiser Division. After some upkeep she was to carry out mostly transport missiones during the co-belligerence, under command of Alberto Banfi until 4 September 1944 and Nicola Murzi from 5 September 1944 to 13 October 1945.

She survived the war, was renamed San Giorgio, and served as a destroyer leader until 1963. She was decommissioned and scrapped in 1980 (will be covered in a dedicated cold war article).

Caio Mario

Caio Mario

Caio Mario, or “Gaius Marius” in english, great reformer and statesman before the age of Casear, she was laid down at O.T.O., Livorno on 28 September 1939, launched 17 August 1941 but never completed before she was captured by the Germans in La Spezia, with only the hull completed, so that she was used as a floating oil tank, and scuttled in 1944.

Claudio Druso

Claudio Druso

Claudio Druso (after Nero Claudius Drusus) was built at Cantiere del Tirreno in Riva Trigoso, laid down on 27 September 1939. Construction was cancelled in June 1940, and shew as eventually scrapped between 1941 and February 1942 to fill more urgent needs of the hard-pressed Italian industry.

Claudio Tiberio

Claudio Tiberio

Claudio Tiberio (Emperor Tiberius) was started at O.T.O., Livorno on 28 September 1939 but construction was cancelled by June 1940. She was scrapped between November 1941 and February 1942.

Cornelio Silla

Cornelio Silla

Silla after launch

Silla after launch

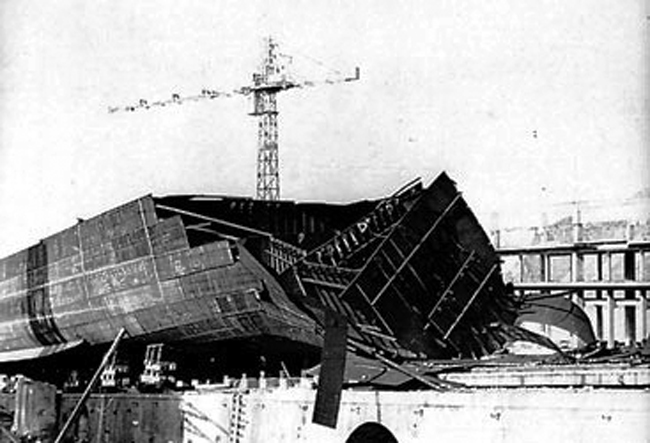

Varo under completion, 1943

Varo under completion, 1943

Cornelio Silla (Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the dictator that re-established the senate faction over the “populares”) was laid down at Ansaldo, Genoa on 12 October 1939, launched on 28 June 1941 and Captured by the Germans in Genoa while fitting out. She was sunk in an air raid in July 1944.

Ottaviano Augusto

Ottaviano Augusto

Ottaviano Augusto in Ancona, after launch

RN Ottaviano Augusto was named after the Emperor Augustus (“Octavian”). She was laid down at CNR, Ancona on 23 September 1939, launched on 28 April 1941, left unfinished and captured by the Germans in Ancona while under completion. She was never completed by the latter and sunk in an air attack on 1 November 1943, so soon after capture.

Paolo Emilio

Paolo Emilio

Paolo Emilio (Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicusn, c.229 – 160 BC) was a two-time consul of the Roman Republic and general who conquered Macedon (hence the surname), putting an end to the Antigonid dynasty in the Third Macedonian War. She namesake ship was laid down at Ansaldo, Genoa on 12 October 1939 but Construction was cancelled in June 1940, and she was scrapped where she laid between October 1941 and February 1942.

Ulpio Traiano

Ulpio Traiano

Ulpio Traiano (the Emperor Trajan) was laid down at CNR, Palermo on 28 September 1939 and launched on 30 November 1942. She was never completed, but was not seized by the Germans for completion since she was sunk while in completion and fitting out on 3 January 1943 by a British human torpedo attack in Palermo.

Vipsanio Agrippa

Vipsanio Agrippa

Vipsanio Agrippa (aftet the famous admiral Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa of Actium fate) was laid down at Cantiere del Tirreno in Riva Trigoso in October 1939, and Construction was cancelled on slip in June 1940, directly linked to the start of the war. It was obviopus she would never be finished and was more useful in scrap metal for more urgent needs. She was scrapped between July 1941 and August 1942.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign