KMS Hipper and her sister ships were the first and only heavy cruiser class ever built by Germany. They were enabled by the 1935 Anglo-German naval agreement and were intended still as commerce raiders and to screen for battleships, but cheating on tonnage. Wartime showed they never really found their place, between the sinking of Blücher by an antiquated Norwegian fortress to the largely failed raid attempt of Prinz Eugen and the few sorties made later from Norway. On the five planned as part of Plan Z, three were of a modified design. Oddly, Lützow, the last one, was sold to USSR during the ill-fated pact of 1939-41. #kriegsmarine #ww2 #germanynavy #hipperclass #admiralhipper #prinzeugen #seydlitz #lutzow #blucher #kistiansand

Origin of the design and development

Cruisers to rule them all: The first heavy cruisers of the Kriegsmarine were separated from their only possible ancestors by nearly 40 years, the last two Scharnhorst 1906 class armoured cruisers, which served Admiral Von Spee well. They had been succeeded only by “leichtes kreuzer”, Armed with 15 cm guns. Any study on this subject was impossible under the Reichsmarine, the Versailles treaty prohibiting anything but eight light cruisers, less than 6,000 tons standard. To be exact 10,000 tonnes which was corresponding to five pre-dreadnoughts, and the remainder for light cruisers, those too old to have been interned in Scapa, or given as war reparation.

Following the Emden, a 1920s schoolship derived from a 1916 design essentially, the “K” class formed the backbone of the German cruiser force, followed by the Leipzig class cruisers, replacing all five of the obsolescent Berlin class cruisers. There was at this juncture no plans fopr a heavy cruisers, which would certainly have passed the 7,000 tons treshold, albeit it was still possible to imagine a reduced version of the Deutschland class cruisers with 8-in guns instead of 11-in (28 cm).

However with the arrival of Hitler to power already in 1933, all these limitations were soon contested. Under the advice of Admiral Raeder, based on the experience of the latest light cruisers, a new ambitious program was set up with the same idea of individual superiority to compensate for numbers. Various options to work on a 7,000 tonnes design were envisioned, like fitting single 8-in guns under mask on the existing Leipzig or K class, since a triple 8-in turret barbette seemed impracticable on the envisioned design beam.

The Anglo-German treaty unlocks everything

The Anglo-German Treaty of 1935 however de facto overruled all remaining limitations officially, and gave the Kriegsmarine some leeway. It enabled the capacity to produce “Washington” cruisers (10,000 tons, eight 8-in guns), but not before 1943. This Agreement was signed on 18 June 1935 and essentially gave the Kriegsmarine 35% of the Royal Navy tonnage.

The Anglo-German Treaty of 1935 however de facto overruled all remaining limitations officially, and gave the Kriegsmarine some leeway. It enabled the capacity to produce “Washington” cruisers (10,000 tons, eight 8-in guns), but not before 1943. This Agreement was signed on 18 June 1935 and essentially gave the Kriegsmarine 35% of the Royal Navy tonnage.

This fixed ratio on a permanent basis indeed completel overruled Versailles limitations, and despite the opposition of France (which was not consulted, as Italy), this agreement was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on 12 July 1935, gaining de facto international recoignition. Despite its “generosity” the agreement still, was abrogated by Adolf Hitler on 28 April 1939.

In the context of “appeasement” before Munich it was a bold gesture from British diplomacy in order to reach better relations with the Reich. Therse were still conflicting expectations between the two countries. Germany saw it as a de facto Anglo-German alliance against France and the Soviet Union but Britain saw it as a new, perhaps more generous arms limitation agreement to stil cap German expansionism. It was controversial and disliked by Royal Navy officials as dangerously close to 50%, the ultimate limit in the old scheme stating that the RN should be at least as powerful of the next two largest fleets combined.

Being equal to the US after Washington, and close to Japan, albeit a war with Japan was far more likely than with the “colonials” both at the time and since, an alliance between Italy and Germany for example, still had to be dealt with. The 35:100 tonnage ratio allowed Germany anyway an entry into the Washinton treaty limitations, despite never signing it. Some in the RN estimated -rightly so- that Germany could in all appearances present a 35,000 tonnes design and cheat on its declaration (which it did for the Bismarck class), or a 10,000 tonnes cruiser in what we are interested for, and also cheat on the displacement. Cheating on artillery was more complicated as it was much easier to verify.

But there were also in the RN advocates of this treaty, such as Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield, First Sea Lord in 1933-1938. What he wanted by admitting Germany in the Washington treaty, that the Kriegsmarine would be obliged to follow more precise standardised classification compared to Versailles, and discouraged “innovations” of the kind that led to the construction of the Deutschland class “pocket battleship”, something extremely dangerous for British trade. Chatfield was instrumental into starting by March 1932 and worked in the spring of 1933 to convince the staff and politicians about the “moral right to some relaxation of the treaty (of Versailles)”.

Reijiro Wakatsuki giving a speech at the London Naval Conference

In February 1932, the World Disarmament Conference started in Geneva and the German demand for Gleichberechtigung (“equality of armaments”) was put into balance against the French “Demande de sécurité” (“security”) about Part V of the Versailles treaty. The British tried to seek a compromise but enabling some leeway from Part V but to still to some limit not to threaten France. However these proposals were rejected by both. In September Germany eventually walked out of the conference. With the nazis close to power, Britain tried hard to convinced Germany back to Geneva by December and obtained from the general assembly a “theoretical equality of rights in a system which would provide security for all nations”. Germany agreed to return to the conference just before Hitler became Chancellor. More negociations would follow to determine the rearmament limits.

However when Germany restarted it’s U-Boat program in clear violation or art. V.

Part V of the Treaty of Versailles… is, for practical purposes, dead, and it would become a putrefying corpse which, if left unburied, would soon poison the political atmosphere of Europe. Moreover, if there is to be a funeral, it is clearly better to arrange it while Hitler is still in a mood to pay the undertakers for their services.

Later, it was still hoped as discussed in a secret meeting in December 1934 to choose to not let Germany rearm despite of treaties, once it was agreed not to wage war on Germany on this point alone, and continue to negociate for a return to the table of negociation to the disarmament negociation and United Nations. As negociations went on, this time after consuting Pierre Laval, France premier, the Hoouse of Commons made clear to be more worried about a German bombardment of London and oto negociate with Germany an air pact outlawing bombing. The acceptation prize was the naval card. It’s really the 21 May 1935 “peace speech” by Hitler in Berlin which formally offered to discuss a 35:100 naval ratio.

In June, Joachim von Ribbentrop went to London for the talks, held at the British Admiralty office, with Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon for the British delegation. After some arms twisting on Ribbentrop’s side, it was agreed that Germany would build up their tonnage levels to what Great Britain’s tonnage levels were in the various warship categories. The next weeks were used to fix technical issues.

In June, Joachim von Ribbentrop went to London for the talks, held at the British Admiralty office, with Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon for the British delegation. After some arms twisting on Ribbentrop’s side, it was agreed that Germany would build up their tonnage levels to what Great Britain’s tonnage levels were in the various warship categories. The next weeks were used to fix technical issues.

It was finally completed and signed on the British side by Sir Samuel Hoare, Hitler being quite pleased in what he saw as a great success of diplomacy. Most in the Perliament thought it still maintained the naval supremavy of Britain above all else, and many also sensed that the Kriegsmarine would be more framed than ever by much more restricting regulations, leaving less room for cheating. In the end, naval experts believed the Kriegsmarine would reach this new tonnage limit by 1942 at best, and this was confirmed in the Plan Z schedule table. But this never happened, between labour shortage, many design and R&D issues, but overall budget priority given to the Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht above all else.

What is important in the end is that there was a hidden side to this agreement and Germany was willing to concede “one third of the Royal Navy except in cruisers, destroyers, and submarines”. Indeed the idea was only to abide to newly-found Washington limits in appearance only. For U-Boats, more were to be built, and for destroyers, larger ones than any British equivalents, the same would be reached for heavy cruisers, now the door was open to the Kriegsmarine. Iconically, unlike what happened to Washington’s signatories, Germany would have its heavy cruisers after the former.

That was a blessing in the sense they could start a design based on the lessons gained over time with all class that were built in France, Italy, Britain, the US and Japan since the 1920s.

Raeder was confident thus, to have “the world’s absolute best heavy cruiser” after two years: The treaty was signed in June 1935, a keel could be laid down at the end of the year and a first ship completed at the earnest in 1937. And the Kriegsmarine could legally acquire five of them: With 50,000 long tons (51,000 t) of heavy cruisers based on 10,000-ton unitary basis.

Therefore the new German cruisers of the Hipper class would just mockingly stick to the limits with indeed a “Washington” main (heavy) armament, but cramming as much secondary, torpedoes and AA guns as possible, but lying on tonnage by more than a safe margin:

At full load, in battle order, the Hipper, second sub-class (1940) were nearing 20,000 tons, so double the Washington’s treaty limits! Only the Des Moines Class in service by 1948 would met these. Despite of this, the armament, harder to conceal, stayed inside the limits. But between size and propulsion they incarnated a design meant to be the ultimate, long range commerce raiders, perfectly able to act with the future plan Z battleships.

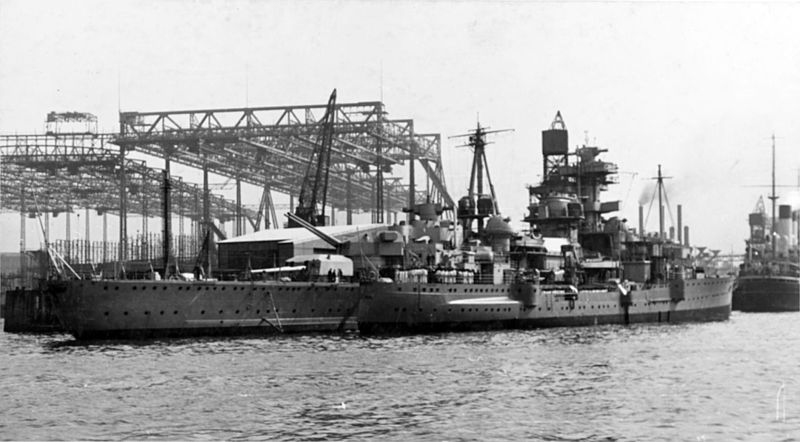

KMS Admiral Hipper (Bundesarchiv)

Design Development

While prospective designs has been discussed and lossely sketched before 1935, Raeder and his staff discussed their options this summer of 1935. Russia on one hand announced its intention to produce 180 mm guns heavy cruisers, being a potential adversary and out of the Washington treaty. It was still maintained that France, not UK was the main foe and any new design could be compared to French standards. On this, the new propective “Schweren Kreuzer” (still unnamed at this point).

The new class needed to be at least equal to the French Algerie class design, or the Italian Zara class. The Hipper were in fact the first five Schwerer kreuzer of Plan Z. Altered, the group was split between the first two and later three sister-ships of the following “subclass” (often separated according to sources), Prinz Eugen. The latter was named in tribute to the defunct Austro-Hungarian fleet, and promoted as an “all austrian crew”. Seydlitz and Lützow were the last of them, but limited capacity meant they could only be Started in 1936-37, and were significantly larger and heavier.

Based on 1935 requirements and 1933-34 previous discussions, the final draft was ready, with a classic four twin 8-in (203mm) artillery, which was on the work since 1933, a capabiliy to act both for the battle fleet, and as commerce raider and have the protection level of the French cruiser Algerie. The best option for the machinery was to adopt a diesel-turbine system already proven on light cruisers. Also an emphasis was put on a strong dual purpose, antiaircraft and torpedo armament. The new C/34 guns tailored for the new class have quite a story, which is developed below in the armament section.

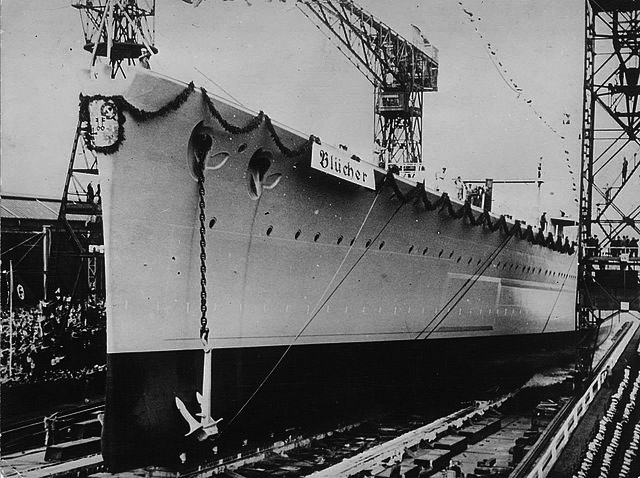

After the final plans were approved, both Admiral Hipper (Kreuzer H, or “Ersatz Hamburg” as she was replacing this old cruiser) and Blücher (“Kreuzer G”, or “Ersatz Berlin”) were ordered in November 1934, before even the official denunciation of Versailles or 1935 agreement, fiorbidding Germany to have cruisers with more than 150mm guns. KMS Prinz Eugen (“Kreuzer J”) was ordered in 1935, this tile on a revised design and new internal arrangement, much larger (and obviously cheating on tonnage already). KMS Seydlitz and Lützow (“Kreuzer K” and “Kreuzer L”) were like Prinz Eugen not even order to replace older cruisers, a semblance of legitimacy for the Bundestag to vote new ships. These later cruiser originally were planed as light cruisers with four triple 150mm turrets according to what was planned in USSR, but in 1937 this was revised and they obtained the same 8-in gun turrets. We will be back on these alternative designs and projects on the upcoming WW2 german cruiser’s main portal.

Upscaling and future Schwere Kreuzer

Yet still, German had amibitious plans for its next classes once Hitler abrogated the agreement in 1939, though with a width carefully restrained to fit the panama canal. Plan Z (which was formed in accordance to the 35% ratio) indeed included only these five heavy cruisers. The irony is that they were the only ones actually built (less the last two were never completed). No aircraft carrier was completed, only four of the ten battleships planned, no battlecruisers, only three of the fifteen “panzerschiffe” (the now older Deustchland class), and less than half the light cruisers, none of the 22 “scout cruisers” (spähkreuzer Type 1938), and so on.

So, what we know about future heavy cruisers of the Kriegsmarine ?

Despite the enthusiasm of some video games to create bogus classes, nothing was planned. The only cruisers that came close were “Panzerschiffe D” (laid down 14 February 1934, Work halted on 5 July 1934, broken up), and E (never built) or the twelve “P-class”. They were all a virtual repeat of the Deutschland based on a different armour scheme, same armament of two triple 28 cm guns, and alternated diesel and turbines engines. The whole P class was canceled on 27 July 1939 before any keel was laid down. They were be the object of dedicated articles in the future, probably 2024.

4×3 6-in alternative design for “Kreuzer K”

The “Roon” an alternative design for “Kreuzer K”

“Clausewitz” a prospective “Kreuzer M”, next class of Schwere Kreuzer for 1945+

So forget the “Mainz”, alternative “cruiser K” armed with triple 6-in guns developed on the basis of the Admiral Hipper-class, the “Roon” same idea, but looking like and upscaled Nurnberg, “Hindenburg” as a totally fictious follow-up with triple 8-in guns turrets, or “Clausewitz” and its 21 cm guns for commerce warfare. The “O” class (“siegfried”) was however a legitimate battlecruiser project, “ägir” being a variant, “Admiral Schröder” an alleged project of the 1920s with 305 mm guns (part of discussions leading to the Panzerschiffe).

Design of the class

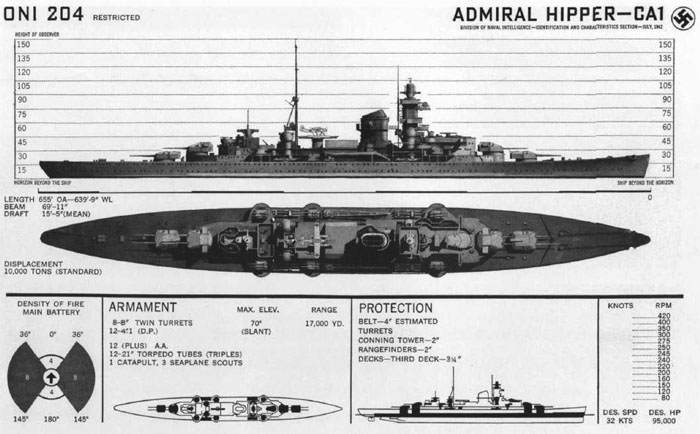

KMS Admiral Hipper, ONI recoignition plate

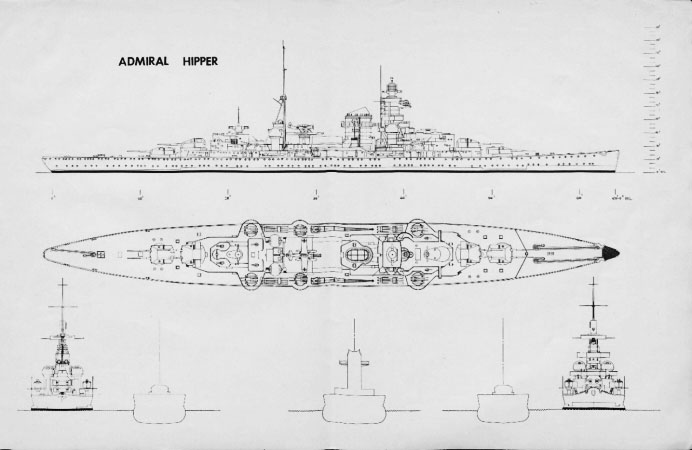

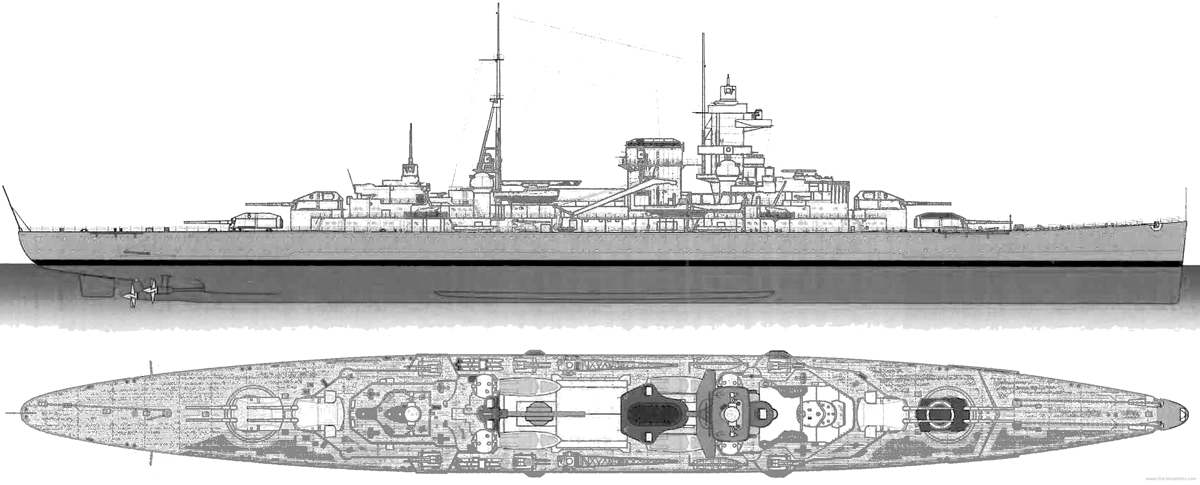

Hull and general design

Master files on navsrc

The Hull shape was brand new. Flush deck, unlike previous light cruisers, the general outlook was based on the Leipzig, with bulges and an internal belt providing longitudinal strength. The initial design called for a straight stem with an overall length of 202.8m, on Hipper and Blücher. But after trials, the same constatations were made as for the Schanhorst class: Admiral Hipper was the first to have her bow reconstructed as a clipper clipper one. Blücher was completed with one, and the remaining cruisers were all completed with a reconstructed stem.

The superstructures were closer in design to the capital ships than light cruisers; There was, in order from bow to stern, the base superstructure, going from “Bruno” turret’s barbette, to “Carl” aft. This first level ran all along the ship and had cutout amidships to allow the torpedo tubes and secondary gun to have enough traverse for a 200° arc of fire.

Next, the conning tower, just high enough to see above “Bruno” roof. It was englobed in a larger “blockhaus” which aft part supported the first telemeter station, with wings. This structure was three-storey tall and secondary guns telemeters were located on either side as well as light FLAK.

Next was the main bridge structure. It was composed of two parts, the base part was rectangular but much smaller or bulky than for light cruisers. It supported the main bridge tower, made of a “0” section, and running for five storeys. On the original Hipper, the main navigation bridge mid-way to the top was open. During later refits and reconstruction it was enclosed. There was no secondary “admiral” bridge.

The very top comprised sets of binoculars and signal lamps. Two more telemeters were located there, one at the foot of the bridge tower, another on top, which was the main Fire control station (see later). Wing towers were secondary AA telemeters were installed under their bulbous caracteristic protection cap. The foremast, which was shorter, sat atop a platform aft of the tower, closely attached to it.

Behind was located a unique, main funnel. Quite large, with a flat top (later a smoke-deviating slanted cap was constructed, which became standard on all). All truncated boiler pipes ended in it. The funnel relative to the ship’s lenght was not central but slightly forward of the exact center and amdiship. Then came the hangar and catapult for a single Arado reconnaissance monoplane (see later). There were the eight service boats, four liaison cutters abaft the funnel, two yawls on the structure, close to the hangar, two boats on davits abadt the main tower bridge. This was minus the numerous inflatable rafts provided.

Both the boats and flooatplane were served by two cranes on either side of the funnel’s rear section, on deck.

Then came the tripod mainmast, taller, supporting a platform for night projectors and later radar, plus all the wireless radio cables attached to the foremast.

And after this, the aft bridge structure, with utiliry and radio room immediately aft of the tripod and the aft blockhaus supporting the rear telemeters and secondary fire control system. The main deck as well as the superstructure deck and even the above structures were all wood-planked. Only the plating supporing the anchor chains betwen the capstans and anchors (supported on flanged niches close to the bow) were in reinforced metal.

The crew comprised 42 officers and 1,340 ratings, wartime additons of AA and electronics raised it to 51 officers and 1,548 sailors. The small vessels carried as standard were two motorized picket boats, two barges, one launch, one pinnace, and two dinghies.

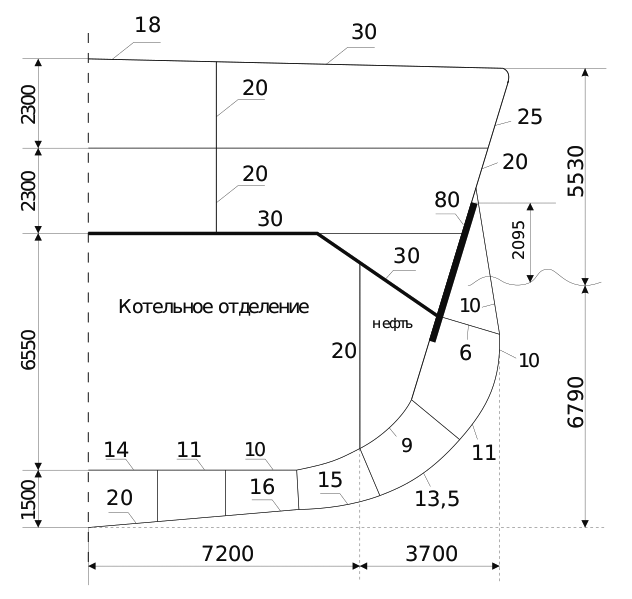

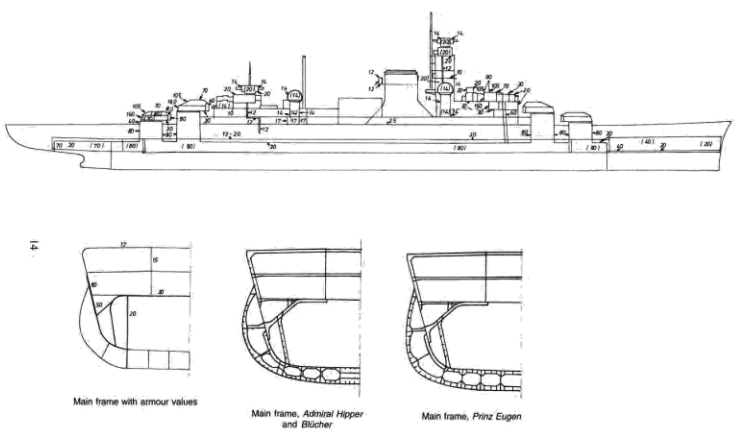

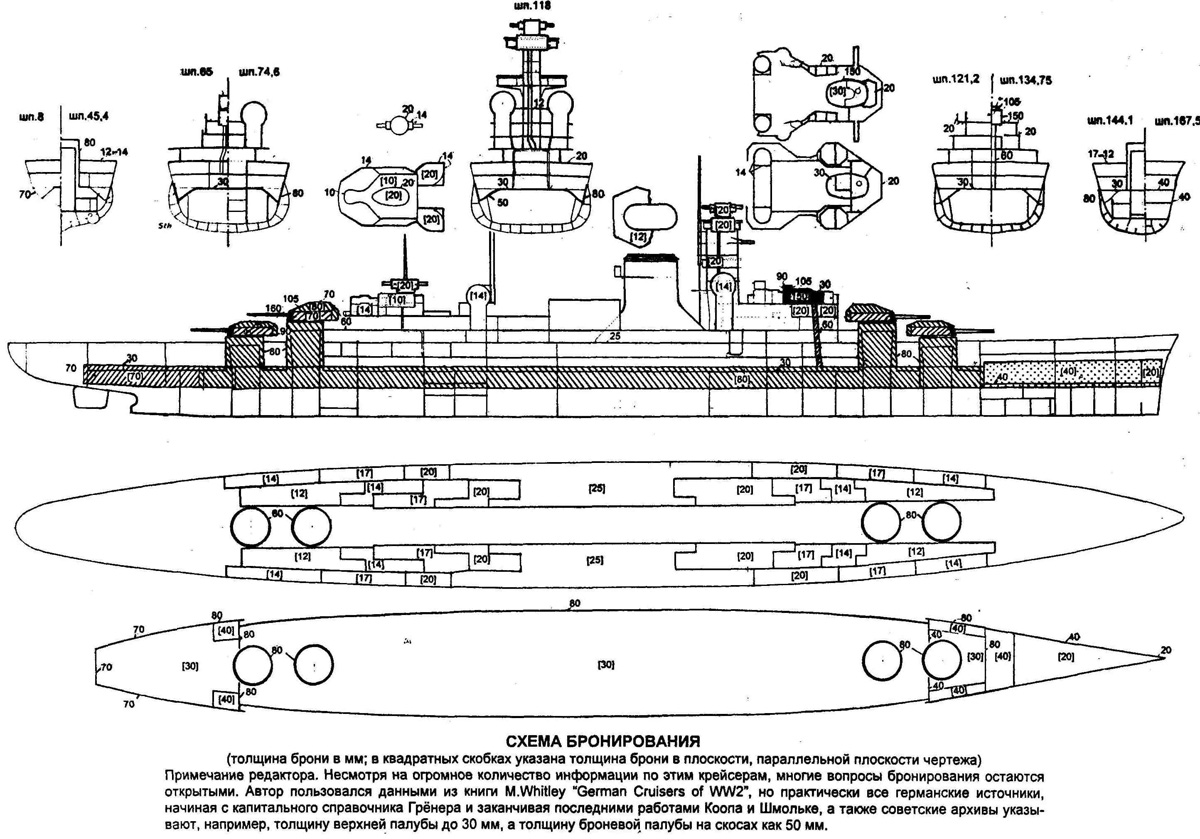

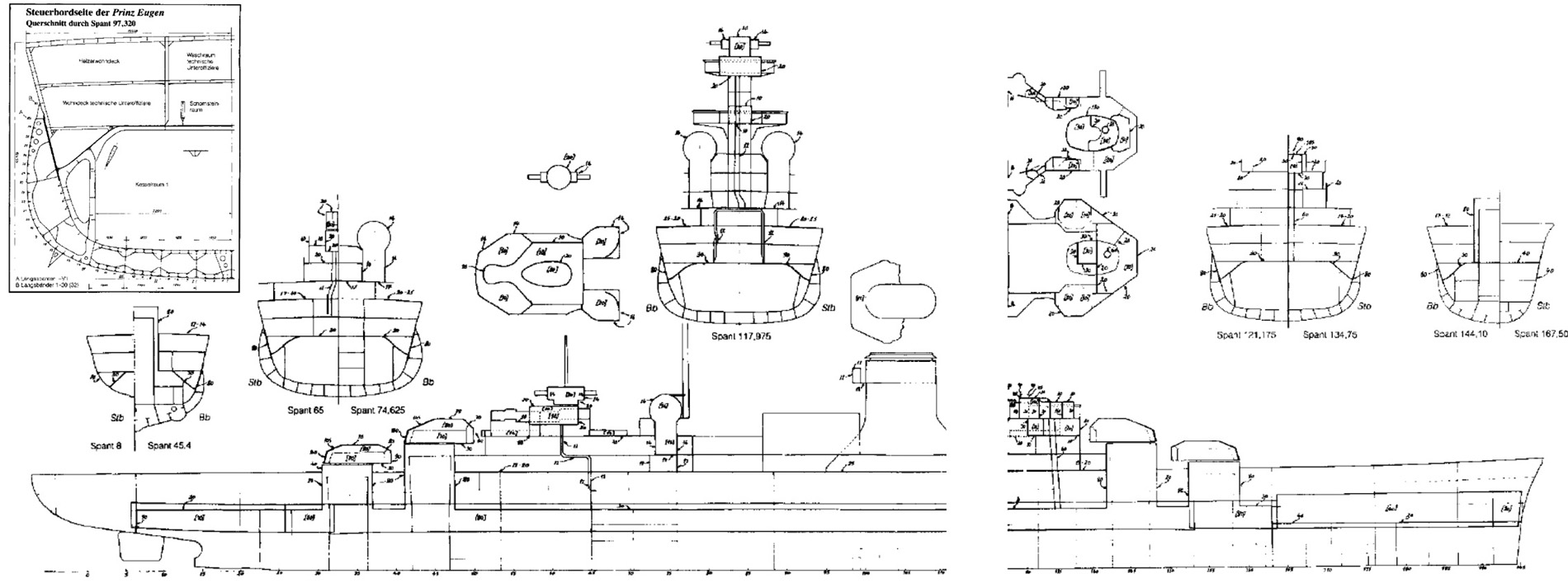

Armour protection layout

Giving the fact these ships were intended to be at least as resilient as the French Algérie, considered as one of the best treaty cruisers (or the Zara class for that matter), it was well thought-of and balanced. Compared to even the latest German light cruiser (Nurnberg) it was way better and closer in general design to the Scharnhost class. For example there was a fully enclosed citadel.

For underwater protection, their hulls were all constructed from longitudinal steel frames, divided into fourteen watertight compartments.

There was a double bottom extending for 72 percent of the keel. There was also the usual sub-compartmentation system below the armor belt, leaving some leeway to get to the central engine compartments, also highly subdivided between turbines roomes and boilers rooms. But nothing revolutionary or quite capable to defeat one or two torpedo hit on places. They were still vulnerable. This was not a priority, as they were supposed to be used as commerce raiders with an artillery keeping them nominally out of range of destroyers. And they were supposedly too fast for submersibles. Protection overall was not impressive, making them rather “intermediate” and not armoured cruisers of some sorts.

Algerie and Zara were not either. Their protection level was not impressive in thickness, but more balanced. Algérie for example had a much thicker armoured Belt at 110 mm (4.3 in) and her decks had a more unequal balanced of 30 mm (1.2 in) to 80 mm (3.1 in) rather than two equal layers of 30 mm, it was on both cases superior. Her turrets were more weakly protected with just 100 mm (3.9 in) face, as the CT with 100 mm (3.9 in). The Zara came above with a 150 mm (5.9 in) belt, as the Turret faces, Barbettes and Conning tower. Certainly a better proposition. But the Hipper wente with years of advances in early electronics and had probably the best firing control systems and most accurate optics of the time, not counting a fierce AA. Being early 1930s designs, the Algérie and Zara were far from it.

Citadel:

Armoured belt 2.75m (9 ft) high, 80 mm (2.6 ft) thick, internal and raked at 12.5° outside on 70% of the length (between barbettes).

-Citadel bulkheads 80 mm (3.15 in) fore and aft.

-Forward of the belt, 3.85 m (12.6 ft) height, 40 mm (1.57 in) thick belt

-Aft belt (outer) 20 mm (0.7 in) thick, 2.75m high, 70 mm (2.7 in) thick

-70 mm aft transverse bulkhead.

Horizontal protection:

-30 mm (1.18 in) upper deck, 30 mm lower protective deck (main armor deck, waterline, under the citadel).

-50 mm (2 in) slopes for the main armor deck, connected with the lower edge of the main belt.

Turrets and Barbettes:

-Barbettes: 80 mm (3.15 in) thick walls all around

-Main turrets: 160 mm (6.3 in) faces, 105 mm (4 in) raking front plates, 80 mm raking sides, 70 mm roof, vertical sides.

-10.5 cm guns shielding: 10-15 mm (0.39 to 0.59 in).

Conning Towers & misc.

-The forward conning tower had 150 mm (5.9 in) walls, 50 mm (2.0 in) roof.

-The rear conning tower only had 30 mm sides and splinter protection, 20 mm (0.7 in) thick roof.

-The anti-aircraft fire directors only had splinter protection: 17 mm (0.67 in) shielding.

Blücher model at the Oscarborg Fortress near Oslo.

Powerplant & Performances

Powerplant differences between ships

Prinz Eugen’s propeller as preserved.

As seen already with torpedo boats, the Kriegsmarine had trouble with its ultra-high-pressure boilers and its steam plants suffered from low reliability while not giving the intended output, significantly reducing endurance. This did not escaped the Hipper class, but at least various configuration were tested, notably to power the future Panzerschiff and battlecruisers of Plan Z.

-Admiral Hipper had La Mont boilers working at 80 atm coupled with Blohm und Voss turbine units.

-Blücher had Wagner boilers (with natural circulation) working at 70atm, and also Blohm und Voss turbines.

-Prinz Eugen had La Mont boilers (70atm) but Brown-Boveri turbines

-Seydlitz and Lützow had just nine Wagner boilers with forced circulation (working at 60atm) and Wagner-Deschimag turbine units.

This made for a pretty diverse pcture, which was intended in order to gather comparative data.

Each turbine drove a three-bladed screw 4.1 m (13 ft) in diameter.

Performances

These machinery were rated, more or less for a nominal 132,000 shaft horsepower (98,000 kW). This was not forced (the boilers were already superheated) and procured on paper a top speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) which was not stellar compared to other cruiser designs of the time, but well enough for their purposes. They can outrun any battleship and still engage any cruisers and destroyers.

Range and autonomy were of course the most important factirs of the design. For this, they carried 1,420 to 1,460 t (1,400 to 1,440 long tons; 1,570 to 1,610 short tons) of fuel oil as designed, but of course, provisions were made by using many ASW void compatments used for protection: They could be filled, as the double bottom, and ensure to double that fuigure to 3,050 to 3,250 t (3,000 to 3,200 long tons; 3,360 to 3,580 short tons). This resulted, for a cruising speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) of a comfortable range 6,800 nautical miles (12,600 km; 7,800 mi).

As a reminder, since were started comparing them with the Algérie and Zara, the first was capable of a radius 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) but at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph), certainly down to 6,000 at 20 kts, and 4,850 to 5,400 nautical miles (8,980 to 10,000 km; 5,580 to 6,210 mi) for the Zara also at 16 knots, so probably 3,500 at 20 kts.

As for agility, Steering depending on a single rudder. They were regarded as good sea boats with gentle motion. At low speed wind and currents affected them greatly as a result of their tall superstructures that acted as sails. They also naturally bled speed when hard over at full regime, heeling up to 15 degrees, with 50% speed loss.

Auxiliary Power

Admiral Hipper and Blücher were provided three electricity plants, coupled to four MAN diesel generators and six turbo-generators each. These diesel generators supplied 150 kW each, and four of the six turbo-generators were rated for 460 kW, the last two 230 kW for a total output of 2900 kW. Prinz Eugen, Seydlitz, and Lützow had 150 kW diesel generators, four 460 kW turbo-generators, one 230 kW turbo-generator, one 150 kW AC generator and a total of 2870 kW. The electric current was setup at 220 volts. This was generous, and intended to power the numerous electrical systems aboard, including then the ships were “cold” at anchor in case of an air attack for example. This powered not only the turret’s mounts (part hydraulic), the AA mounts, lighting, fire control systems and telemeters traverse, and all the electronics aboard, with provisions for future radars, possibly more power-hungry.

Armament

For their size, these cruisers were not that impressive. Their battery was “standard”, as it was difficult to lie about, with a classic 4×2 main gun configuration. Given the way the Japanese lied however it could have been possible to create 210+ mm tubes, the difference was not that obvious, or to just gave them thicker tubes for a later re-boring. However this implied too many changes in the whole loading apparatus, which used mechanical process with little tolerance to avoid jamming. Instead, better accuracy and overall range and muzzle velocity were worked on. Ironically these guns were slightly BELOW the Washington limit. They were not 203mm stricly (8 inches) but the actual diameter was 7.992″. But the loose barrel used offered some leeway for future increase.

AA and torpedo armament was impressive and given the large size of the ship, fit to their tonnage. It was even increased a bit during WW2 (see below), but with caution for their stability.

Main: Eight 20.3 cm SK C/34

The three completed ships had the same battery of eight 20.3 cm SK C/34 guns, in four twin turrets, two superfiring pairs fore and aft.

The three completed ships had the same battery of eight 20.3 cm SK C/34 guns, in four twin turrets, two superfiring pairs fore and aft.

Barrels: These guns had an interesting story. Design started in 1934 as soon as the Hipper class was approved. They were tested in 1935-37, but really delivered and installed in 1939. They were constructed of loose barrel with an an inner and outer jacket as well as a breech end-piece, screwed hot on to the outer jacket. They had a breech block supporting piece held by a threaded ring. What was important is that the loose barrel could be removed from the rear and fit any gun. They found their way in fortifications. The breech block was of the classic, horizontal sliding type, hydraulically operated.

Turrets: These were housed in Drh LC/34 turrets. The mounted enabled −10° in depression, 37° in elevation, max, which gave them a 33,540 m (110,040 ft) range.

Shells: These were the standard HE 122 kg (269 lb) with a muzzle velocity of 925 meters per second (3,030 ft/s). But also the range included an armor-piercing, a base-fuzed, nose-fuzed high-explosive (HE) warhead variant and another for AA purpose (AA 4a 265 lbs. or 120 kg).

There was a stock of 40 illumination rounds (103 kg – 227 lb for 700 m/s or 2,300 ft/s).

Provision varied between 960 and 1,280 rounds depending on the ships, which meant 120 to 160 rounds per gun.

Seydlitz’s turrets were eventually used as coastal artillery in the Atlantic Wall. When delivered to USSR, Lützow only had her two forward turrets.

More.

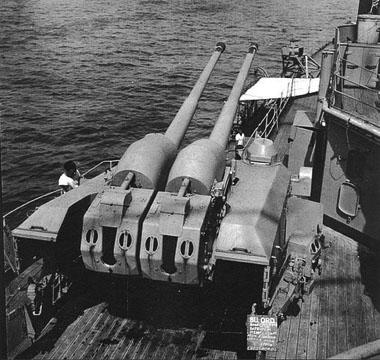

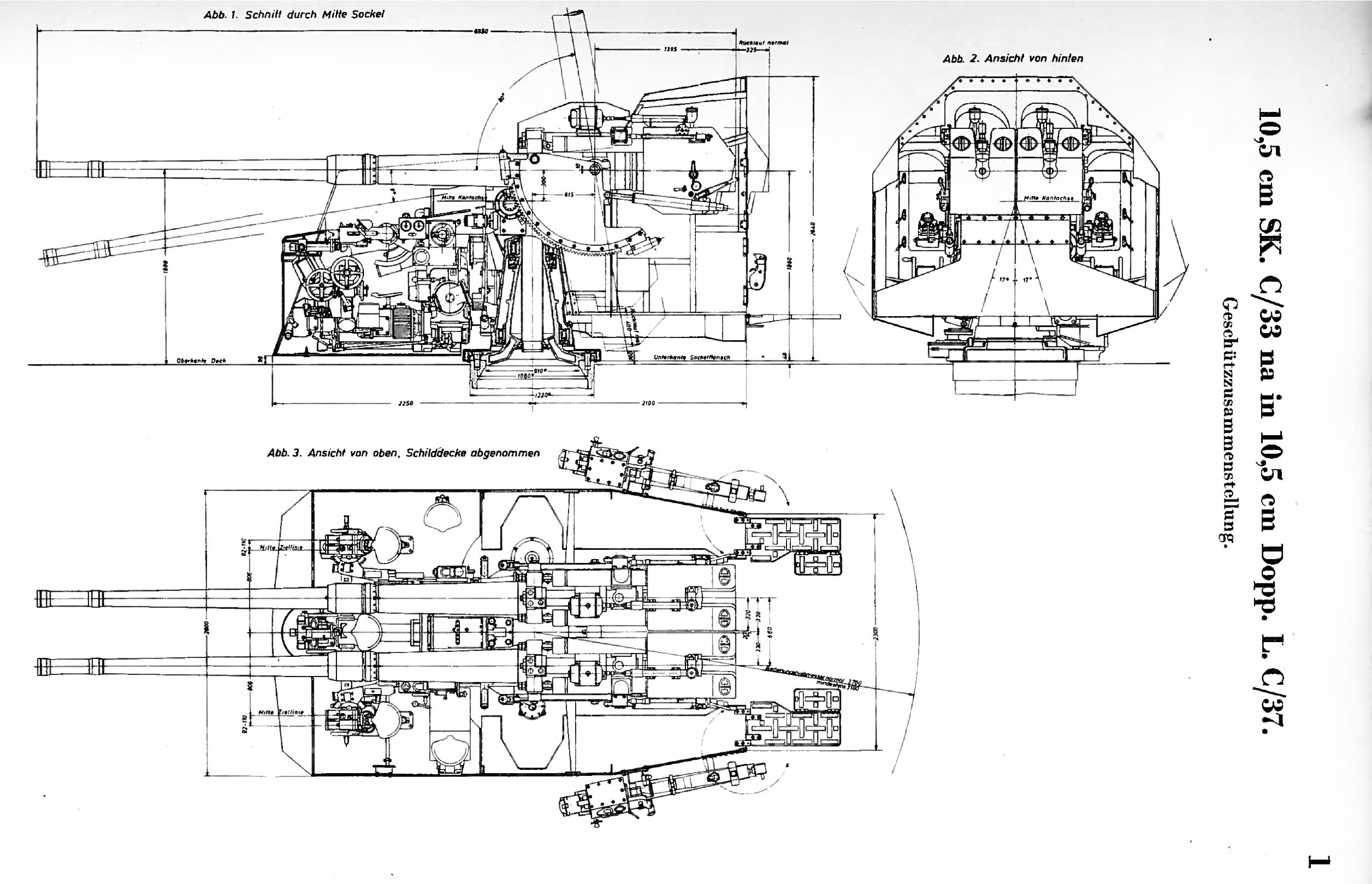

Secondary: 10.5 cm/65 (4.1″) SK C/33

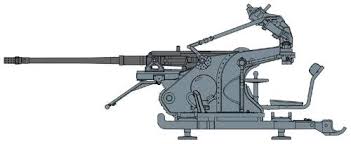

105 mm mount on the Prinz Eugen

Although there had been discussions about providing them with six or eight single-mount, shielded 15 cm guns at early stage of the design in 1933, the naval staff eventually preferred a dedicated dual-purpose caliber. A wise decision in 1934.

These were the ubiquitous 10.5 cm/65 (4.1″) SK C/33 also found on the bismarck, Deutschland, Scharnhorst, and light cruisers of the kriegsmarine.

No less than twelve of these guns were installed, in six twin mountings. They were located on six positions along the structure, two forward on the wings of the battery deck, two on deck abaft the catapult, and two on wings of the aft structure, behind the tripod mainmast. Certainly among the best DP guns of their generation, but still inferior to the US 5-in/38.

Dimensional drawing of 10.5 cm/65 SK C/33 guns in Dopp. L. C/37 mounting. Sketch from “Unterrichtstafeln für Geschützkunde”.

Mounts: Dopp LC/31 type made for the 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK C/31 originally.

-Triaxially stabilized (electrically) with a 80° elevation.

-Rate of fire/Barrel life: 18 rpm; 2,950 rounds

-Muzzle velocity: HE 2,952 fps (900 mps)

-Range: Ceiling of 12,500 m (41,000 ft), surface range 17,700 m (58,100 ft)

-Shells: Unitary type fixed HE/HE incendiary, 15.1 kg (33 lb).

-Provision: 4,800 rounds provided in all, including illumination shells.

More

Anti-Aicraft Armament

-For Close-range they had twelve 3.7 cm (1.5 in) SK C/30 guns, all in dual mounts (doppel) along the superstructures. In 1943-45 replaced when possible by the 3.7 cm KM42 and 3.7 cm KM43.

Rate of fire was circa around 30 rounds per minute with a maximum elevation of 85° procuring a ceiling of 6,800 m (22,300 ft). They were fed by 20-rounds magazines. They were shielded by light anti-spalling constructs.

More

Schematics of a 20mm SKC30 FLAK naval mount (single)

-They had eight 2 cm (0.79 in) Rheinmetall Flak 38 guns. Magazine-fed, they were automatic weapon in part inspired by the Swoss Oerlikon. They fired at up to 500 rounds per minute. They were fed by 40 magazines for a grand total of 16,000 rounds aboard, and some were tracers. More

-They had eight 2 cm (0.79 in) Rheinmetall Flak 38 guns. Magazine-fed, they were automatic weapon in part inspired by the Swoss Oerlikon. They fired at up to 500 rounds per minute. They were fed by 40 magazines for a grand total of 16,000 rounds aboard, and some were tracers. More

Naturally this was epxanded during the war and on the Prinz Eugen class (see later).

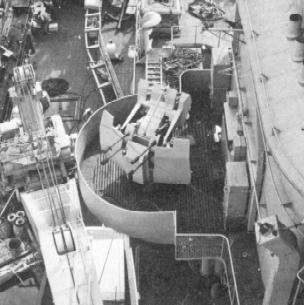

Torpedo Tubes

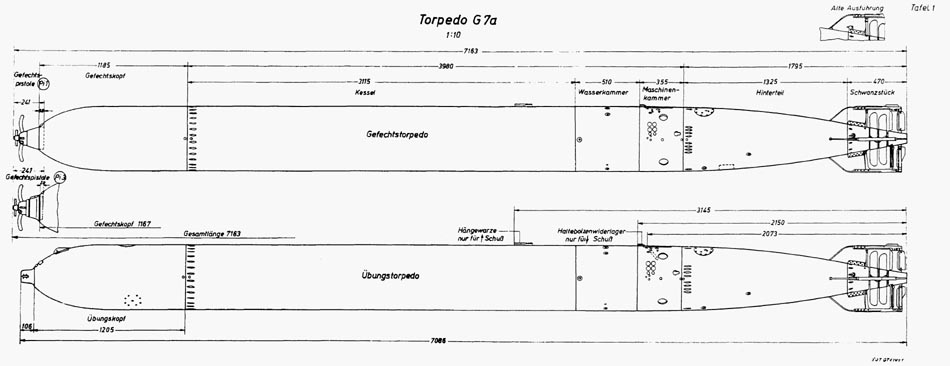

G7a main plan. More schematics and full details here.

As befitting to their role of commerce raiders, they had had no less than twelve torpedo tubes, in four triple launchers on her main deck amidships.

For these, the cruisers carried twenty-four G7a torpedoes so twelve loaded in the tubes, and the same ready reload.

The G7a torpedo was the staple of the Kriegsmarine at the time, used on U-Boats and ships alike.

Specs: 300 kg (660 lb) warhead, three-speed settings (12,500 m/30 kn, 7,500 m/40 kn, 5,000 m/44 kn) thanks their 340 horsepower (250 kW) radial engine and figures were increased to 14,000, 8,000, 6,000 m at the speeds seen above.

KMS Admiral Hipper was also equipped to carry 96 EMC mines, contact types with a 300 kg explosive charge.

Fire Control Systems & Radars

This was generous, “battleship” size, with at first planned three main directors and four directors for the antiaircraft artillery.

Hipper was provided at completion with a FuMo 22 radar.

The secondary battery used the sophisticated stabilised HA fire control system.

In early 1942, Hipper received a FuMO 27 radar and FuMB 7 Timor ECM suite. In 1944, she received a FuMO 25 radar.

Prinz Eugen and her sisters were planned to have two FuMo27 radars. In February 1942, she obtained a new state of the art equipment, comprising the FuMO 26 radar, FuMB4 Sumatra, and FuMB 7 Timor ECM suites. In 1944, this was upgraded to the FuMO 25, FuMO 81 radars, FuMB3 Bali, and FuME 2 Wespe-G ECM suites, kept until she was captured in 1945. This was the most extensive and sophisticated electronics suite of any axis cruiser of WW2 and thus, under US custody this was examined in great detail. Some ideas were recycled in the early cold war electronic upgrades of destroyers and cruisers.

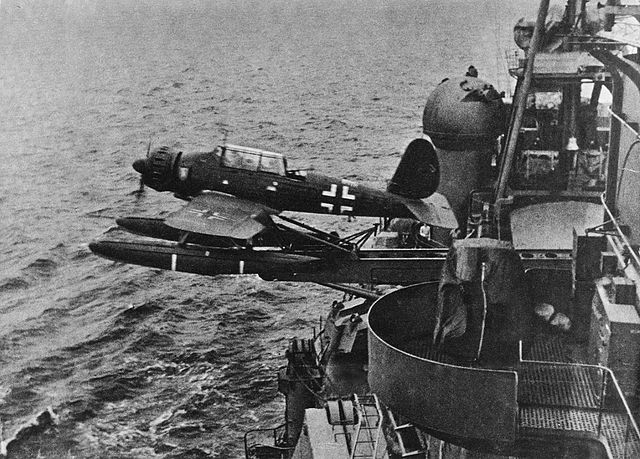

Onboard Floatplanes:

Arado 196 on Admiral Hipper.

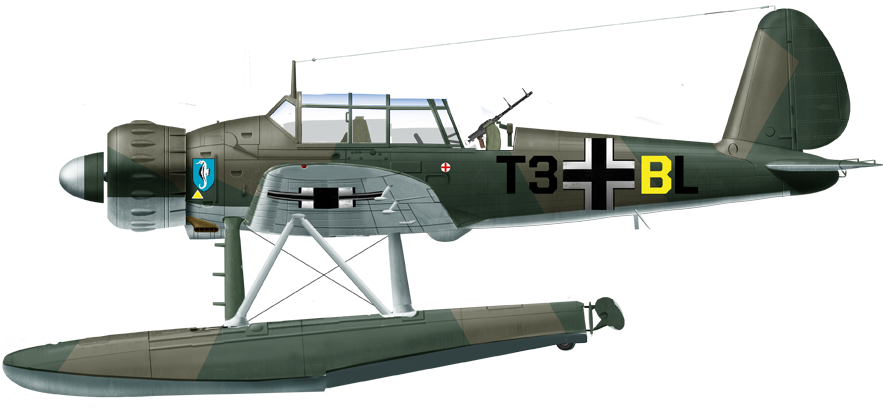

As completed, Hipper, Blücher and Prinz Eugen were tailored to carry and operate three floatplanes, with a catapult (type to find) and a hangar below, large enough to accomodate two of them, wings folded side by side. The roof of this hangar was telescopic. According to navypedia, they carried 3 seaplanes defined as the He 60, He 114 and/or Ar196. The He 60 was a 1934 biplane, and might have been planned in the 1934 specifications.

However by the time Hipper was completed in 1939, it had been already replaced by its sucessor the He 114. However the latter had many issues, and the problem is that not many source states about its use but perhaps in 1939-40. In fact it is likely they were provided with Photos and most sources only shows as model: The infinitely superior Arado Ar 196. Another source is more specific and even states three Arado Ar-196A-3 (globsec).

Both the He 114 and Arado were produced and served in the Kriegsmarine, but the He 114 was entirely supreseded aboard ships by the Ardao 196. Both the He 60 and Arado 196 will be treated with their own dedicated posts. It should be added that several sources points out the Prinz Eugen class as being able to carry four floatplane, not three. First off, it would mean a larger hangar to accomodate all four wings folded in two pairs, but also the emphasis or air reconnaissance for commerce raiding activity, which was coherent with the practices of the time. Virtually all auxiliary merchant raiders of the Kriegsmarine had a floatplane onboard.

Arado 196 A3, 1/Borderflieger Gr.196, KMS Prinz Eugen spring 1941.

Arado 196 specs: Top speed: 11 x 12.4 x 4.45 m, 2,990 kg, BMW 132 radial 311 km/h (cruise 268 km/h), range 1,070 km

⚙ KMS Hipper specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 202,80 x 21.30 x 7.20 m (665 ft 4 in x 69 ft 11 in x 24 ft) |

| Displacement | 16,170 t (15,910 long tons) standard, 18,200 long tons FL |

| Crew | 1,600 |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts Blohm & Voss turbines, 12 boilers*, 132,000 hp (98 MW) |

| Speed | 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) |

| Range | 6,800 Nautical Miles (12,600 km; 7,800 mi) at 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Armament | 4x2x 20,3 cm, 6×2 10,5 mm, 6×2 37mm AA, 4×3 53,3 cm TTs, 2 floatplanes |

| Armor | Belt: 85 mm (), Deck: 38 mm (), Turrets 162 mm, Conning tower: 152 mm () | Electronics | 2 main FCS, 2 AA FCS, 2 TTs FCS, FuMo 22 radar |

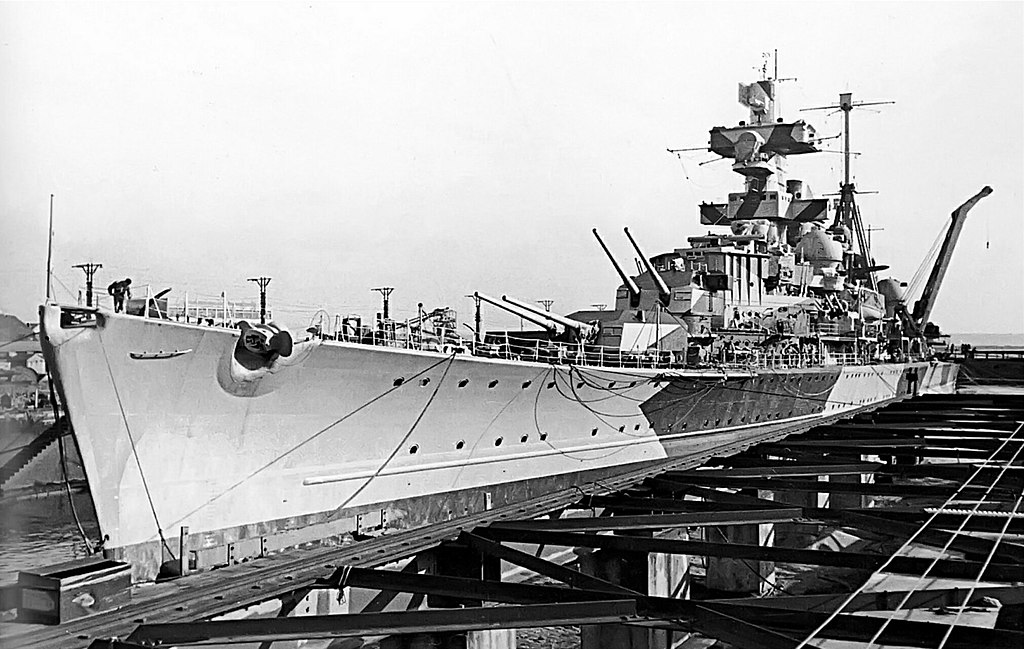

Design Differences: The Prinz Eugen group

Master files on navsrc

Prinz Eugen was 199.5 m (655 ft) long at the waterline, 207.7 m (681 ft) overall as planned, but the addition of a clipper bow had her extended to 212.5 m (697 ft), making her the longest cruiser in Europe. Her beam was conservatively kept at 21.7 m (71 ft) still, with a draft of 6.6 m (22 ft) on standard displacement, up to 7.2 m fully loaded. KMS Seydlitz and Lützow reached were 210 m (690 ft) long overall, clipper included, meaning shorter than Prinz Eugen, with a beam however ported to 21.8 m (72 ft), and a draft of 6.9 m (23 ft) standard, 7.9 m (26 ft) fully loaded. Given the fact they were a bit tropweight, this beam augmentation was short-sighted and too timid.

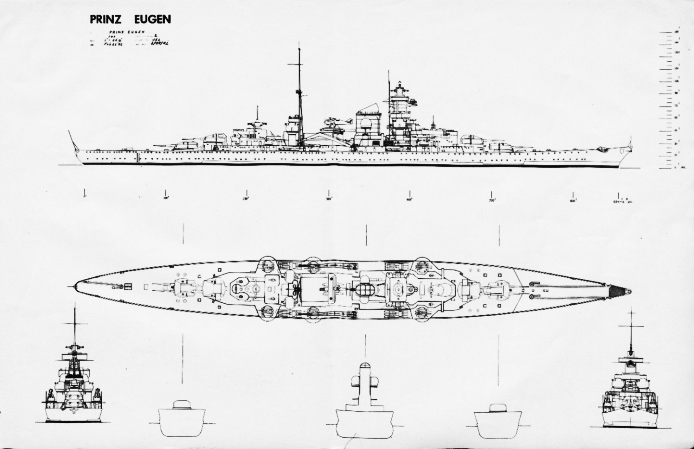

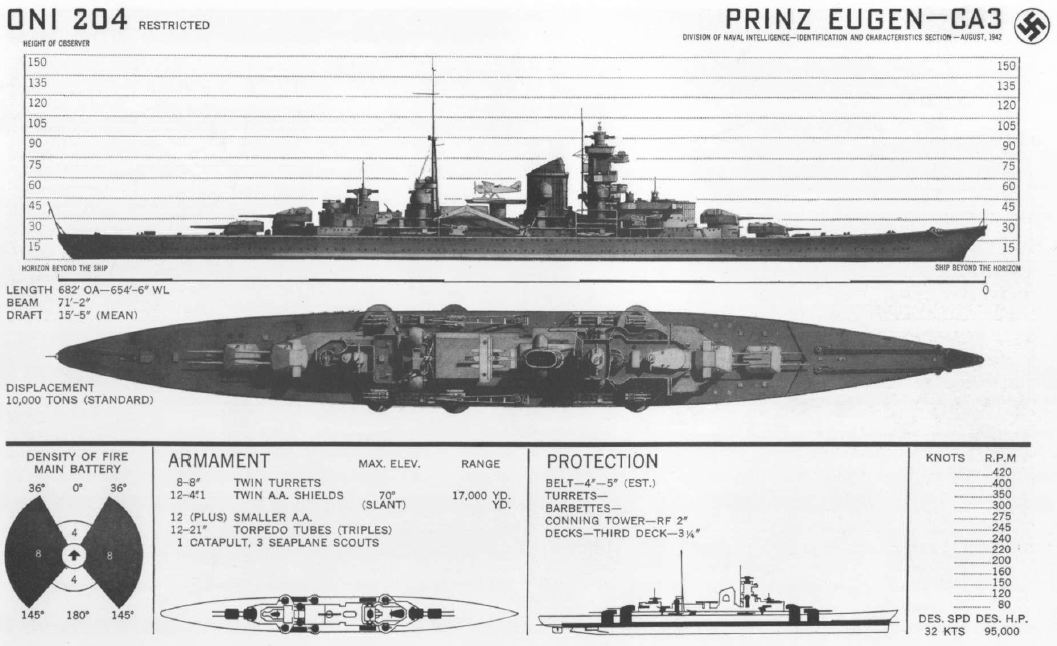

ONI 204-48 depiction of Prinz Eugen.

“Nominally”, in the register, the early ships (Hipper and Blücher) were within the 10,000-ton limit. But it is easy to lie on simple numbers. KMS Admiral Hipper and Blücher already were designed with a standard displacement of… 16,170 metric tons (that’s 15,910 long tons or 17,820 short tons) and with a full load displacement of 18,200 long tons (18,500 t), so nearly double the Washington treaty !. This made already the largest cruisers in the world. For memory, the USN came with the Baltimore design in 1942, and only reached 17 030 t. Fully Loaded.

Now there was KMS Prinz Eugen, which displacement increased to 16,970 t (16,700 long tons; 18,710 short tons) as designed standard, and this rose to 18,750 long tons and (19,050 t) fully loaded. On their side, KMS Seydlitz and Lützow reached a healthy 17,600 t (17,300 long tons; 19,400 short tons) as designed, standard and reached and 19,800 long tons (so 20,100 t) fully loaded. There would be no cruiser of that size before the Des Moines class, or the Alaska, but they were far from a Washington design.

Light armament differences and upgrades

Later light anti-aircraft batteries of Admiral Hipper and Prinz Eugen were altered with four 3.7 cm removed and up to twenty-eight 20 mm procured, partly with the new flakvierling mounts.

In 1944, Prinz Eugen’s remaining 3.7 cm guns were all replaced by fifteen 4 cm (1.6 in) Flak 28 guns (see below). In 1945, she had twenty 4 cm guns, eighteen 2 cm guns while Admiral Hipper had sixteen 4 cm guns, fourteen 2 cm guns.

Blücher being lost early on in the Norwegian campaign, Hipper was modified in the following way:

In 1940 she received two single 20mm/65 C/38 and in 1941 her first Flakvierling (4x 20mm/65 C/38). In early 1942 she received two extra single 20mm/65 and two more Flakvierling C/38, and later this year another Flakvierling. In 1943, a fifth was installed, and in 1944 she only carried two twin 37mm/80, three Flakvierling and eight single 20mm/65 when added six single 40mm/56 FlaK 28, and eight twin 20mm/65 C/38. This did not changed for 1945.

On her side, KMS Prinz Eugen had six twin 37mm/80 SK C/30, and ten single 20mm/65 C/38 AA guns plus two FuMo27 radars.

Later in 1941 she received four Flakvierling 20mm/65 C/38, and in early 1942 one more of these plus an extensive electronics upgrade in February. In 1944, she had two twin 37mm/80 and two quad 20mm/65 landed as well as the FuMB 7 Timor ECM suite and in place six 40mm/56 FlaK 28 installed. In 1945 this went further and she had four twin 37mm/80 and ten single 20mm/65 retired and in place twelve 40mm/56 FlaK 28 installed as well as a Flakvierling and two twin 20mm/65 C/38 mounts.

4 cm (1.6 in) Flak 28 guns

Norway being occupied, local Bofors gun stock (they were produced in Sweden) was captured. The Kriegsmarine thus operated those, designated “4 cm Flak 28” on the cruisers Admiral Hipper and Prinz Eugen, based on allied reports on the efficience of this weapon. From 1942, several E-boats were also equipped with the Flak 28 to fight allied MGBs and MTBs.

⚙ KMS Prinz Eugen specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 212,50 m x 21,70 m x 7,20 m (697 ft 2 in x 71 ft 2 in x 24 ft) |

| Displacement | 16,970 tons standard, 19,050 tons Fully Loaded () |

| Speed | 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) | Armor | Same but turret faces: 105 mm (4.1 in) | Crew | 42 officers, 1240 ratings |

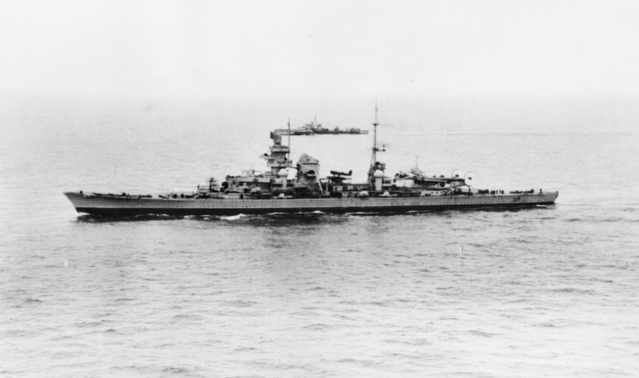

General assessment of the class

Both had very sophisticated gunnery control systems, sights, radars, a powerful anti-aircraft battery, but lacked range due to the lack of diesels for the revised commerce raiding duties. They had instead highly sophisticated and somewhat capricious high-pressure turbines creating constant mechanical problems in service. Their silhouette recalled the Scharnhorst battleships in reduction, but still at launch they were the most powerful cruisers in the world. Hipper saw her bow rebuilt in 1939 as her sister Blücher in the Atlantic clipper style, later directly implemented on Prinz Eugen.

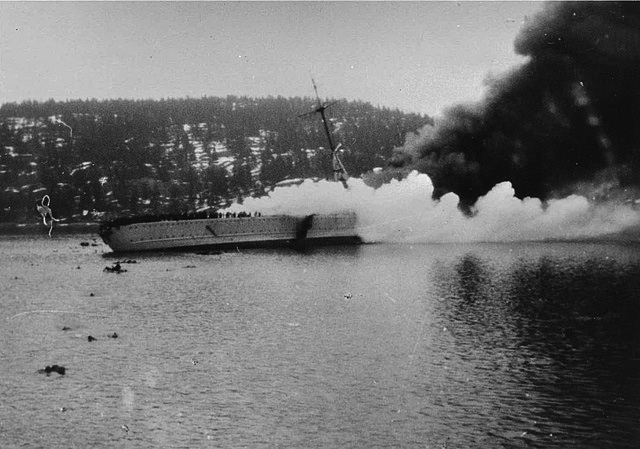

It must be said by the loss of Blücher to the Oscarborg Fortress, an humiliation for the kriesgmarine, was partly due to the hidden “secret torpedoes”, and to the initial damaged cause by just two 28 cm hits. Despite their age, these guns were perfectly adequate given the short range. The upper superstructure of the cruiser were never able to cope with his caliber at any range, but the ASW protection held out for longer than expected after two torpedo hits, even of the old Whitehead models used were also antiquated and “only” 18-in in caliber. It’s the fire caused by the initial hit near the hangar that doomed the ship. It became soon uncontrollable and prevented in effect the crew to concentrate on the flooding instead. Examinations of the wreck more recently shown also the damage caused by 15cm guns on the hull’s side also, which in large part contributing to the flooding. The torpedo however buy destroying crucial bulkheads made that gradual flooding incontrollable at the end. Capsizing was inevitable.

Other examples showed in classic sea battle conditions the ships were adequate: Hipper’s conduct as a commerce raider was impeccable and she had quite some success. When combating a Colony and a Town class cruisers off Norway in 1942, she held her own perfectly well depsite having a considerably lesser rate of fire.

The last and best example was Prinz Eugen, which key moment was the her duel against Hood and Prince of Wales. She fired first and essentially is credited in part for the explosion of the hood. Historians still debates today over the exact nature “killer blow”. It seems now that the deck fire, even spreading below decks, was not the real culprit, but “one-million shot” rather to consider. A single shell entering via a weak point the insides and eventually reaching the ammo storage. Prinz Eugen also gave good account on herself when duelling with Prince of Wales. Due to the coulded, but still fine weather for this area in May, her fire control proved accurate.

The final assessment was given by the USN after recuperating KMS Prinz Eugen. As the lastest and best European Cruiser design, she was a price of choice, carefully monitored. The most striking piece of equipment that was studied in detail was of course the top end fire control systems, optics and radar of the ship. She had the best combination possible at the time, worthy of a battleship. Far less impressed they were however by her appealingly mediocre powerplant. They had to retain German engineers to work and maintain these until the Bikini test, and she was towed there.

Gallery

KMS Hipper

KMS Prinz Eugen, both old author’s illustrations. New ones waiting.

Read More

Hipper in completion at Blohm & Voss, Hamburg, 1939.

Books

Binder, Frank & Schlünz, Hans Hermann (2001). Schwerer Kreuzer Blücher. Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft.

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. NIP

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2014). Schweren Kreuzer der Admiral Hipper-Klasse. Seaforth Publishing.

Maiolo, Joseph (1998). The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany, 1933–39 A Study in Appeasement and the Origins of the Second World War

Philbin, Tobias R. (1994). The Lure of Neptune: German-Soviet Naval Collaboration and Ambitions, 1919–1941.

Rohwer, Jürgen & Monakov, Mikhail S. (2001). Stalin’s Ocean-Going Fleet: Soviet Naval Strategy and Shipbuilding Programmes, 1935–1953.

Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Heavy Cruisers 1939–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Whitley, M. J. (1987). German Cruisers of World War Two. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Links

ONI – Blücher

totallyhistory.com the-anglo-german-naval-agreement/

THE ANGLO-GERMAN NAVAL AGREEMENT OF 1935: AN ASPECT OF APPEASEMENT Richard A. Best Jr.

Same, download link

de.wikipedia.org Admiral-Hipper-Klasse

On navypedia.org/

On worldnavalships.com

On world-war.co.uk/

on globalsecurity.org

On german-navy.de

Prinz Eugen de.wikipedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org photos

Videos

Hipper on Dark Seas channel

The hipper class by Drachinfels

Model Kits

WW2 german ships always had been popular. Although less “bankable” as the ubiquitous Bismarck, Scharnhorst or Deustchland class, the Hipper clas received plenty of coverage:

Main query on scalemates

The larger kits, 1:200, were covered by GMP. Trumpeter made its 1:350, Heller its 1:400, Airfix its 1:600, and a cohort of 1:700 followed, of Hipper, Blucher, and Prinz Eugen. For fanatics of scratchbuilt and hyper detail, The Scale Shipyard made an 1:100* (see the page) and Fleetscale a 1:128 hull. *A 83 inches () monster of a hull, 500$ alone, and kits containing the 8″ TURRET SETs with range finder hoods, periscopes, rear vents, 8 8″ barrels and 4 barbettes or the DIRECTORS: 4 Anit aircraft directors, ball type, 2 main battery directors (main top, and aft). The rest is done by scratchbuilt.

Modeller’s books:

-Die Schweren Kreuzer der Admiral Hipper-Klasse Admiral Hipper – Blücher – Prinz Eugen – Seydlitz – Lützow (Gerhard Koop, Klaus-Peter Schmolke) Hardcover 243 pages 1992

-Niemieckie krążowniki typu Admiral Hipper (Andrzej Perepeczko) Nr. 35 64 pages by AJ-Press.

More

The Hipper class in action

KMS Hipper

KMS Hipper

Admiral Hipper in completion at Hamburg in 1938.

Admiral Hipper was completed (and commissioned) on 29 April 1939, in presence of Kriegsmarine CinC, Großadmiral Erich Raeder. He has personal connections with the name, as the former Franz von Hipper’s chief of staff in WWI. He thus gave during the launch on 6 February 1937 a christening speech, his wife Erika performing it. She had a straight stem by then and no funnel cap.

Her first captain was Hellmuth Heye. In April 1939, Admiral Hipper started her initial training in the Baltic and stopped in various Baltic ports notably in Estonia and Sweden during her shakedown cruise. By August 1939, after being back for post-fixes and crew’s leave, she returned to the Baltic this fire for her first live fire drills. In September 1939, she was still performing gunnery trials when reassigned to patrol the Baltic and back to training. In November she was howeve prepared for war in Blohm & Voss dockyard, having her new clipper bow and funnel cap installed.

Hipper Training in the Baltic in late 1939

She returned in January 1940 for sea trials and more training, marred by icing. On 17 February the Kriegsmarine estimated she was now “fully operational”. The 18th, she started her first major wartime patrol as part of Operation Nordmark with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the destroyers Karl Galster and Wilhelm Heidkamp, going off Bergen in Norway under command of Admiral Wilhelm Marschall, truing to intercept British merchant shipping.

Operation Weserübung

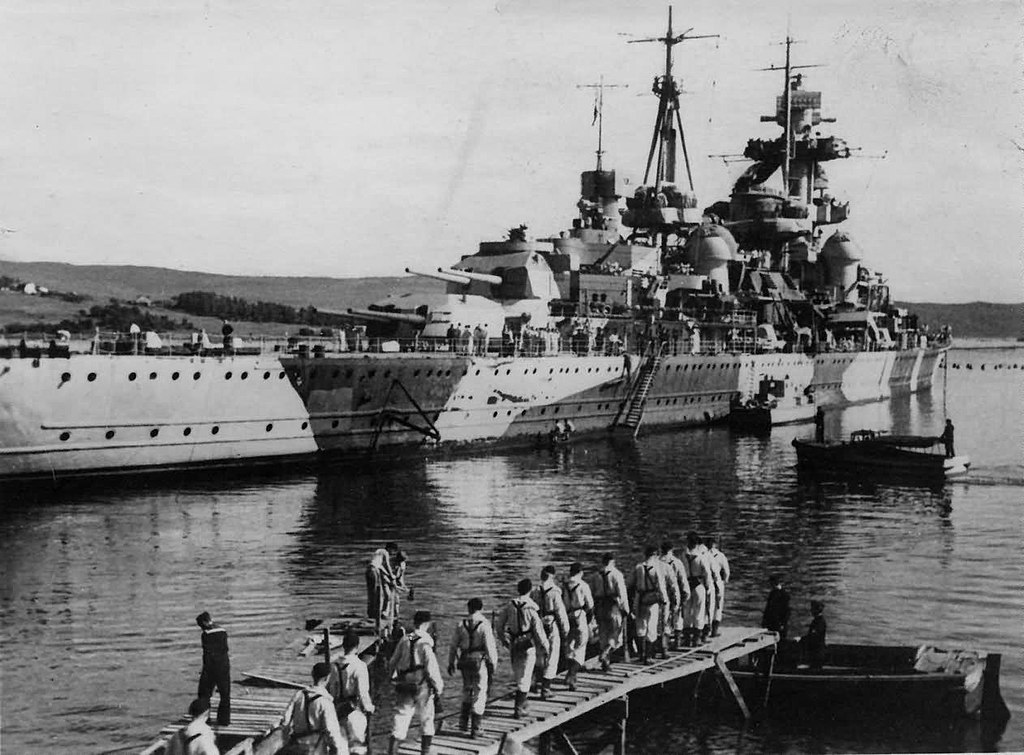

Hipper taking aboard the Birgsjäger (Mountain troops) and their gear in Cuxhaven, on 6 April 1940

The landing

Back from the North Sea sortie she was reassigned to the invasion of Norway force, assigned as flagship, Group 2 with a escorts the german destroyers Paul Jakobi, Theodor Riedel, Friedrich Eckoldt, and Bruno Heinemann. Captain Heye had overall command of Group 2 and all ships carried a human load, 1,700 Wehrmacht mountain troops tasked to seize Trondheim. They loaded troops and equipments in Cuxhaven, sailed to the Schillig roadstead off Wilhelmshaven and met Group 1 (Scharnhorst-Gneisenau and ten destroyers) covering both Groups against any British intervention. They proceeded in the night of 6–7 April to arrive at dawn.

While off the Norwegian coast, Hipper was ordered to locate the destroyer Bernd von Arnim, which had disappeared from view in the mist. One was spotted by the British destroyer HMS Glowworm and duelled, captain Bernd von Arnim requested assistance from Admiral Hipper. When she arrived, Glowworm misidentified her as firendly, which was fatal, as the cruiser left her little chance to escape, opening a withering fire. Glowworm attempted to flee but was not fast enough to dodge more hits, but managed to evade Hipper’s torpedoes, while returning a hit on Hipper’s starboard bow. One hit on the destroyer jammed her rudder and put her in a collision course with Hipper…

While off the Norwegian coast, Hipper was ordered to locate the destroyer Bernd von Arnim, which had disappeared from view in the mist. One was spotted by the British destroyer HMS Glowworm and duelled, captain Bernd von Arnim requested assistance from Admiral Hipper. When she arrived, Glowworm misidentified her as firendly, which was fatal, as the cruiser left her little chance to escape, opening a withering fire. Glowworm attempted to flee but was not fast enough to dodge more hits, but managed to evade Hipper’s torpedoes, while returning a hit on Hipper’s starboard bow. One hit on the destroyer jammed her rudder and put her in a collision course with Hipper…

Against HMS Gloworm: Top, about to cut her way, laying smoke, bottom, in flames.

The destroyer banged her hull and severed a 40-meter (130 ft) section or the starboard armored belt and destroy her starboard torpedo launcher, with some flooding causing a 4° list. On her side, Glowworm had her boilers exploding due to the schock, broke and sank quickly with 40 survivors picked up. Back to Trondheim Hipper was informed the destroyer sent a message to the admiralty, and the latter soon scrambled the battlecruiser Renown to intercept them. In between, the “terrible sisters” broke off contact.

Hipper one her side lost one of her Arado seaplanes. It had to land in Eide, Norway, on 8 April after running out of fuel, tried to purchase some from locals before the latter captured the crew, handed over to the Police. The plane was soon integrated into the small Norwegian Navy Air Service and later evacuated to Britain.

While off Trondheim, Hipper activated a fake recoignition pattern, passing for a British warship. This worked enough for her to pass the Fortifications at the entrance and entering the harbor, docking before 05:30, landing mountain troops as planned. The latter soon seized control of the coastal batteries so Hipper left the port and sailed for Germany escorted by Friedrich Eckoldt, arriving in Wilhelmshaven on 12 April. There, she was drydock for repairs, completed in just two weeks. She was needed for more missions.

Operation Juno

Commander Marschall organized the seizure of Harstad in Northern Norway as a strategic British Base was located there, that can interfere with Kriegsmarine operations and full occupation of the country. It was planned to take place in early June 1940 and again, Admiral Hipper, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were prepared for the operations and assigned four destroyers. Departing from Kiel on 4 June, they refueled from Dithmarschen. They plan to arrive on the 9th, but on the 8th, new order came as a reconnaissance plane reported the harbor was empty. Meanwhile the fleet detected highly increased convoy radio transmissions and concluded to an evacuation, so Marschall decided to intercept the convoy instead.

Search for the convoy in foul weather was done with difficulties. At some point, the tanker Oil Pioneer was spotted at 06:45 on 8 June, escorted by the armed trawler HMT Juniper. Hipper made short work of her, while Gneisenau sank the tanker. At 10:52, Hipper spotted and sank the empty troopship Orama. With all her Arado 196 in the air, still the fleet could ot locate the bulk of the convoy. At 13:00, Marschall decided to split his force, Admiral Hipper and the destroyers being sent to Trondheim whereas the two battleships would refuel from Dithmarschen and proceed the operation.

On 10 June, Hipper and Gneisenau left Trondheim with the four destroyers, trying to spot more evacuating convoys but failed to locate any. On 13 June, they were attacked by British Bombers (likely Blenheims) and Hipper’s AA gunners shot their first. On 25 July, Hipper sailed for her first “free commerce raiding patrol” between Spitzbergen and Tromsø, until 9 August. Her only prize was the Finnish freighter Ester Thorden which by luck had 1.75 t (1.72 long tons; 1.93 short tons) of gold from the Norwegian reserves.

Operation Herbstreise

Admiral Hipper left Norway on 5 August to be overhauled in Wilhelmshaven until 9 September, and having a new captain, KzS Wilhelm Meisel. It was planned to use her for Operation Sea Lion. She would play a diversionary foray into the North Sea called Operation Herbstreise, trying to lure out the British Home Fleet away during the German crossing of the English Channel. With Seelöwe postponed on 24 September, Hipper keft Wilhelmshaven on a similar comerce raiding mission but soon ran into machinery issues, her engine oil feed system caught fire and damage was sever enough to cause a suhutting down of her propulsion. Once the fire extinguished, she stayed several hours dead on the open sea, but luck would have no British reconnaissance located her. She was repaired in Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg for a week.

Operation Nordseetour

She sailed for a second attempt, Operation Nordseetour, on 30 November. Crossing the Denmark Strait undetected on 6 December she eventually spotted and fell on convoy WS 5A, 20 troopships lightly escorted, on 24 December, located some 700 nautical miles west of Cape Finisterre, France, as part of Operation Excess (a serie of Mediteranean supply missions). The escort however was sizeable, with the aircraft carriers Furious and Argus, the cruisers Berwick, Bonaventure, Dunedin plus six destroyers. Hipper’s captain was cautious failed to initially spot the escor and so directly preyed on the convoy, badly damaging the 13,994-long-ton (14,219 t) Empire Trooper and another trropship before her lookouts spotted Berwick and destroyers rushing on her position. Hipper’s captain order to turn back, and to fire to keep her pursuiers at a distance.

Ten minutes after however, HMS Berwick reappeared off her port bow and opened fire. Berwirck and Hipper exchanged volleys, the latter from her “Anton” and “Bruno” turrets only and hit the lightly protected rear turrets as well as her waterline, causing flooding and devastating her forward superstructure, after which she disengaged. Captain Maiseil main preoccupation indeed was to avoid the destroyer closing enough to launch a torpedo attack. He was also informed he was running low on fuel. His only snesible option was to rush for Brest, occupied France on 27 December. While underway he spotted the 6,078 GRT passenger ship Jumna, promptly sank. After maintenance in Brest, she was prepared for another sortie from a far better position to attack the Atlantic convoy routes.

Second Atlantic Convoy sortie

On 1 February 1941, Admiral Hipper departed, joined by the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau initially, but Gneisenau was delayed after storm damage in December. Anyway, bith sisters were reunited and launched their own raid by early February while Admiral Hipper proceeded alone, making a rendezvous with a pre-posted tanker off the Azores to refuel, while learning Force H just left Gibraltar for an escort deep in the Mediterranean. Captain Meisel now new convoys between the UK and West Africa would be less protected, and decided prioritize this shipping lane.

On 11 February, she spotted and sank an isolated transport (convoy HG 53) previously dispersed by a combined U-boat/Luftwaffe attack, proving also to Dönitz this tactic was very efficient.

The evening of the 11th saw Hipper spotting at last the unescorted convoy SLS 64 (19 merchant ships).

Her decided to shadown the convoy until the early hours, and arrived like a fox in a chicken coop, closed in to achieve the most efficient fire, sinking several ships and damaging others in quick succession. The damaged one survived, the the British later reporting 7 ships lost (32,806 long tons) 2 more damaged, whikle German propaganda based on Hipper’s report, claimed 13 of 19, survivors on their part reporting 14. At some poing she went close enough to fire all her 12 torpedoes, claiming all hit. In any way, this was a severe blow for the British and a confirmation to Erich Raeder that this raiding actions sould take priority over all else.

Hipper’s fuel running low she was forced to return to Brest on 15 February and shile drydocked in a small dock when moving she damaged her starboard screw, on uncharted wreckage. One new spare bronze screw propeller had to be transferred from Kiel, causing much delay, during which other convoys proceeded unhampered while Brest was frequently visited by the RAF. She was attacked by British bombers causing little damage but this was enough for the high command to decided to repatriate her back home.

Hipper’s escape from Brest and refits (March 1941-March 1942)

On 15 March, by night, the cruiser sailed unobserved and proceeded to a rendezvous point, south of Greenland, with the tanker Thorn. The refueling went on until 21 March, the cruiser delaying her departure due to the fould weather. Meanwhile Admiral Scheer was also returning from a raid and it was decided to delay her breakout via the Denmark Strait before 28 March (Scheer was to pass there). She proceeded on 24 March, refuelled in Bergen and arrived in Kiel on the 28th, making good her escape.

She entered the Deutsche Werke shipyard for an her lagrest wartime overhaul lasting for seven months during which she received new radars and AA. After sea trials in the Baltic and post-fixes in Gotenhafen on 21 December she was examined and issues were found with her powerplant, quite serious. So by January 1942, she was gutted to have her steam turbines overhauled at Blohm & Voss shipyard. On this occasion she also receiced a degaussing coil to mitigate the issue of magnetoc mines the British used (as the Germans). In March 1942 she was declared at last fully operational, after almost a year of inactivity, during which the convoy situation changed drastically. The US were now at war with Germany and the US fleet provided a more active coverage of the Atlantic. Bismarck had been sunk in May 1941 and last raids had been mostly unsuccessful. The time of Atlantic raids were over, Raeder was stepping back, Dönitz was stepping in.

Norwegian Raids

Under pressure to find some use for his surface fleet, Hitler was at some point keen on scrapping, Raeder convinced him to post his remainder forces in Norway, from which these ships can prey both on the artcic convoys to Russia and northern Atlantic Convoys. The ships would have the protection of deep, long fjords in which an extensive AA could be setup as well as better air protection.

On 19 March 1942, Admiral Hipper thus departed for Trondheim with destroyers Z24, Z26, and Z30, torpedo boats T15, T16, and T17. British submarines patrolling the area failed to located them. The force arrived on 21 March, joined sister ship Prinz Eugen and KMS Lützow (The Deutschland class ship, not the incompleted cruiser). Prinz Eugen however soon returned to Germany for repairs her torpedo damage.

Operation Rösselsprung

On 3 July 1943, Hipper joined Lützow, Scheer and Tirpitz for an attack on convoy PQ 17 escorted by HMS Duke of York and USS Washington, covered by the armoured aircraft carrier HMS Victorious. Hipper, Tirpitz, and six destroyers went alone from Trondheim while Lützow, Admiral Scheer, and six destroyers went from Narvik, but soon the former and three destroyers struck uncharted rocks and went back for repairs.

Swedish intelligence reported German departures to the British Admiralty, ordering the convoy to disperse, quite a blunder, as it delivered them to U-Boats. Aware of their detection, the Germans folded down. Nevertheless, both the Wolfpacks and Luftwaffe would make a carnage with 21 of 34 vessels sent to the bottom.

Operation Doppelschlag

Admiral Hipper joined Admiral Scheer and Köln in the Altafjord for a raid planned to start after the 10 September. Underway, they were spotted and torpoedoed (but missed) by HMS Tigris. The operation was aborted as Hitler feared more losses to hiw dwindling down surface fleet.

Operation Zarin:

For the first and only time, Hipper would make good use of her mine laying rails and equipments: She departed to lay a minefield on 24–28 September, off the north-west coast of Novaya Zemlya, right into the path of arctic convoys. She was escorted for this mission by the destroyers Z23, Z28, Z29, and Z30. With this field, the hop was to funnel merchant traffic further south in reach of the Luftwaffe and ships based in Norway. Back in Altafjord, she departed again for Bogen Bay, near Narvik, to be repaired, notably overhauling her sensitive propulsion system.

On 28–29 October, Hipper and the DDs Friedrich Eckoldt and Richard Beitzen retruend to the Altafjord in the north. From 5 November, Hipper and the 5th Destroyer Flotilla (Z27, Z30, Richard Beitzen, Friedrich Eckold) tried to located a convoy making his way in the Arctic under command of Vizeadmiral Oskar Kummetz. On 7 November her Arado Ar 196 floatplane at last located the 8,052 t Soviet tanker Donbass escorted by the small BO-78. The destroyer Z27 was sent in interception course and sank both. This was the only success of this raid as soon the ships ran out of fuel.

Battle of the Barents Sea

Hipper would soon be put to her greatest test. In December 1942, Arctic convoys, after too many losses, resumed at last. Großadmiral Raeder prepared Operation Regenbogen, a last-ditch massive attack on the convoys, with all forces available. JW 51A arrived in Murmansk without incident, but JW 51B was spotted by U-354 south of Bear Island. Raeder ordered a sortie. Hipper was again Kummetz’s flagship and she was accompanied by the Panzerschiff Lützow, destroyers Friederich Eckoldt, Richard Beitzen, Theodor Riedel, Z29, Z30, and Z31 of Altafjord. Leaving at 18:00 on 30 December, Kummetz had to jaudge the encountered escort and not taking too much risk.

He soon came with the idea of splitting his forces with Admiral Hipper and three destroyers north of the convoy, attacking first and luring away escorts while Lützow and the remaining three destroyers would attack later from the south, the undefended convoy. A “by-the-book” pincer. At 09:15, 31 December, the destroyer HMS Obdurate spotted Hipper’s group destroyers and the latter fired first. Four more destroyers rushed, HMS Achates staying behind to lay a smoke screen and cover the convoy. Hipper fired at Achates and eventually forced her after many hits down to 15 knots while Kummetz withdrawn northwards to draw the destroyers away, commander Robert Sherbrooke deciding to leave two destroyers by precaution. Four were now in hot pursuit.

Meanwhile Force R (RADM Robert Burnett) with the “colony” class cruisers HMS Sheffield and Jamaica all this time in distant support raced to engage Admiral Hipper, which at the time was posrt-firing on HMS Obedient. The cruisers approached by her starboard side, making full surprise and raining salvoes of 6-in in quick succession in Hipper, hit three times right away, and taking more. Eventually her propulsion system was damaged, her No. 3 boiler got seawater pollution, and the while outer starboard turbine engine was shut down, making her falling to 23 knots. She also had her aircraft hangar devastated. After a single response salvo she turned towards them under destroyer’s smoke.

Emerging from it, she engaged Burnett’s cruisers and was hit in return. Uncertain however of the rest of British defense, Kummetz decided to break off at 10:37, retiring westwars back to Norway. In the mayhem, one of her escorting destroyer, KMS Friederich Eckoldt mistook HMS Sheffield for Admiral Hipper, and it was too late when she recoignised her. She was sunk at point-blank range.

Lützow on her side followed the plan and arrived 3 nmi (5.6 km; 3.5 mi) of the convoy in poor visibility, not opening fire until Kummetz’s orders were recieved, so she turned west to join Admiral Hippern still crawling at 23 knots at this point. But while doing so, Lützow soon spotted Sheffield and Jamaica in hot pursuit, and after a correct identification open fire. With six 28 cm guns against the british twenty-four 6-in (fire thrice as fast) that would be an interesting match. Both British cruisers turned toward Lützow whereas Hipper, drawn by the light of volleys, closed in and opend fire in turn. On the British side, the odds were turning ugly. Hipper accurate and faster fire damaged Sheffield, but Burnett had the sense of escapting, which they did helped by the fog.

Hipper underway off Poland in December 1944

Based on the framing order to avoid action with an equal force (which was not the case here), and due to poor visibility plus the damage on Hipper, Kummetz weighted his options and eventually decided to abort and come back to Norway. HMS Achates, previous rampaged by Hipper would never make it home. The minesweeper HMS Bramble was also sunk and HMS Onslow, Obedient, and Obdurate badly damaged, but this was a tactical sucess for the Royal Navy which allowed the Convoy to proceed unmolested. Hitler was furious and again reitared his order to scrap the surface fleet. Admiral Karl Dönitz was soon appointed as Raeder’s successor at the head of the Kriegsmarine and presuaded Hitler to keep the surface fleet for more actions in Norway. Hipper had emergency repairs in Altafjord, then in Bogen Bay (23 January 1943) and she returned to Germany for more with Köln and Richard Beitzen via Narvik (25th), Trondheim (30th) while searching underway for Norwegian blockade runners in the Skagerrak. She was in Kiel on 8 February and decommissioned on 28 February after Hitler’s decree.

A sad end for the lead ship

Admiral Hipper in Kiel’s dry dock on 19 May 1945 under camouflage netting, she had been heavily damaged by bombers previously. Color photos from allied troops discovering Hipper in Germaniawerft shipyard, July 1945 also showing her tower bridge

While decommissioned, repairs proceeded. In April she was moved to Pillau (Baltic), out of the reach of Allied bombers. Delkays accumulated due to the lack of adequate facilities, shortage labour and materials. In 1944 she was moved to Gotenhafen with plans to recommission her to be used against Soviet forces progressing to the Baltic. Hipper’s sea trials lasted for five months, wshowing accumulating problems with her powerplant. In between she received a new AA and radars, but failed to reach operational status. The Soviet army dediced of her ultimate fate: Her crew was drafted to reinforce Gotenhafen’s defenses. The Royal Air Force laid a minefield blockading the port, condemning the cruiser to stay there.

The fall of 1944 saw the cruiser inactivated again for another three months until it was decided to move her away from the advancing Soviet forces, crawling miserably with her single working turbine left.

On 29 January 1945, she left Gotenhafen with 1,377 refugees aboard and received underway a distress call from Wilhelm Gustloff (the worst civilian sinking since Titanic), but the cruiser did not divert to stop, rightly fearing Soviet submarines in the vicinity. She arrived in Kiel on 2 February, interned in Germaniawerft shipyard for a refitting that would never end. On 3 May, she was severely damaged by a RAF raid. Her crew eventually was compelled to scuttle her at her moorings at 04:25 the same day. In July 1945 she was raised, towed to Heikendorfer Bay and broken up during 1948–1952. Her bell was showcased at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and was returned to Germany, Laboe Naval Memorial, Kiel.

KMS Blücher

KMS Blücher

KMS Blücher’s launch in 1937

KMS Blücher was built in Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel under construction number 246 and completed/commissioned on 20 September 1939 with and was in fitting out until the end of November, starting sea trials to Gotenhafen, until mid-December. She was back to Kiel for post-trials fixes, and from January 1940, resumed her exercises in the Baltic until blocked by icing. On 5 April, the Kriegsmarine esteemed her “fully operational”, and she was assigned to invasion of Norway fleet.

Operation Weserübung

Blücher proceeding to Norway seen from the cruiser Emden

On 5 April 1940, Konteradmiral Oskar Kummetz came aboardwhile in Swinemünde and soon the 800 men of the 163rd Infantry Division boarded. On the 8th, KMS Blücher left for Norway as flagship, Oslo Force, or “Group 5”. Nobody knew at the time this was to be her first and last war mission. She was acompanied by the Panzerschiff Lützow, light cruiser Emden, and escorts. They were spotted through the Skagerrak by HMS Triton which launched a spread of torpedoes, evaded.

The German flotilla approached Oslofjord by night. At 23:00 the Norwegian patrol boat Pol III spotted them, and sent a message. She was quickly engaged ad sunk by the German torpedo boat Albatros. The radio report scrambled all Norwegian defences. At 23:30 south battery on Rauøy spotted the ships in turn, turned on it its large searchlight and fired two warning shots. Five minutes later Rauøy fired four rounds over foggy waters and missed. It should be said that these guns were mostly obsolete. The next Bolærne fired a warning shot at 23:32 but Blücher was soon out of range.

The flotilla was running at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) due to the fog. The Norwegian Commanding Admiral passed to order to shut all lighthouses and navigation lights over the local radio (Norsk rikskringkasting) while the German flotilla had orders not to engage the forts first but if engaged. Between 00:30 and 02:00 the flotilla stopped to transfer 150 infantrymen to the escorting R-Boote R17 and R21 from Emden and R18 and R19 from Blücher to take the forts by force. This led to the Battle of Drøbak Sound:

Battle of Drøbak Sound

The R boats landing party attacked first Rauøy, then Bolærne and before proceeding to Horten. All surprise now lost, Blücher nevertheless proceeded further to reach Oslo by dawn. At 04:20, Norwegian searchlights illuminated the cruiser at 04:21. This was a defining moment: The old 28 cm (11 in) Krupp guns of Oscarsborg Fortress fired at point-blank range. They scored two hits on the cruiser’s port side, in the battle station (killing the AA guns commander) and knocked the main range finder, although the cruiser fell on its four backups and prepared firing. The hit hit close to the aircraft hangar, starting a bonfire which soon detonated explosives stockpiles for the infantry and lighting the ship up. The two Arado seaplanes burnt as well as the one on the catapult. Historians later revealed she had a hole in the armored deck, over turbine room 1, causing the latter to stop as well as the third generator. After two shots, the ship had an incontrollable fire and just 2/3 of her power.

Due to the fact they were the only light source in the area, spotters were unable to trace back the source of the gunfire. As request by the captain, a speed of 32 knots was ordered, and soon the 15 cm (5.9 in) guns of Drøbak on her startboard at 400 yd fired as well. Soon Blücher was also engaged by Kopås and Hovedbatteriet, and the Kaholmen fort. The Kopås battery soon ennaged Lützow in turn and hit her several times. First engineer Karl Thannemann reported Drøbak’s hits on starboard entered the cruiser’s flank over 75 m (246 ft) amidships between B and C-turret. Soon the bridge steering was disabled. While off Drøbakgrunnen the cruiser started to turn to port to try to evade fire, using the side shafts while loosing speed. At 04:34 two torpedoes from a concealed part of Oscarsborg fortress scored hits in turn. From then on there was no hope for the cruiser.

According to Kummetz’s report, one torpedo hit Boiler Room 2 under the funnel, the second Turbine Room 2/3. At this point the ship only had one boiler left, but all steam pipes were damaged and she lost power in turn so that by 04:34, the cruiser managed to pass through the firing zone, with only the Kopås battery still within range. Birger Eriksen the commander however never ordered to continue fire.

The ASW compartimentation played its role to an extent and Blücher managed to stay afloat but listing to 18°, while still crawling to a few knots. The whole crew was comitted to save their ship and combat fire. When the firce fire reached one 10.5 cm ammunition magazine close to turbine room 1-room 2/3, there was a considerable deflagration. Bulkheads were reuptured, the fuel stores were pierced and started to ignite in turn, and the list became uncontrollable. The cruiser started to capsize, order to abandon immediately followed. But it was too late for most of the crew trapped inside the ship. She rolled over and sank at 07:30 with most men aboard. The number of casualty given is ranging between 600 and 1,000 at the most, down to 125 seamen and 195 soldiers.

Between the loss of Blücher and heavy damage to Lützow the German force withdrawned. Ground troops on the eastern bank proceeded inland, captured the Oscarborg Fortress at 09:00 then moved on the capital. Airborne troops captured Fornebu Airport and by 14:00, 10 April the city-was german-controlled. But due to the battle at sea, the Norwegian government and royal family managed to escape to Britain.

Blücher capsizing

Today, Blücher is still at the bottom of the deep Drøbak Narrows under 64 metres, south-east of Askholmen holms. Her screws were salvaged in 1953 but no proposition to raide her was ever accepted. The problem was she still had a large quantity (94,000 cu) of oil still on board and leaked it constranty, making for an ecologic hazard. In 1991 the leakage increased to much with the rusted away tanks, that the Norwegian government decided to remove as much oil as possible with the help of petrol company Rockwater AS using deep sea divers. They managed to remove 1,000 t of oil but could not reach still 47 fuel bunkers. Her two Arado 196 aircraft, although badly burnt were also recuperated, now on display after restoration at the Flyhistorisk Museum near Stavanger. The wreck was made officially a war memorial on 16 June 2016 to discourage looting.

KMS Prinz Eugen

KMS Prinz Eugen

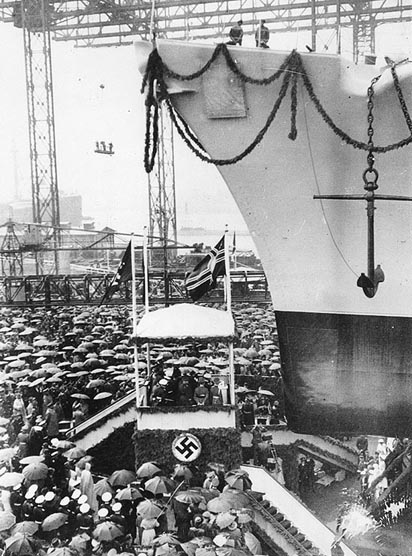

Prinz Eugen’s launch – Bundesarchiv

KMS Prinz Eugen was built at Germaniawerft shipyard, Kiel, laid down on 23 April 1936 as hull number 564, “Kreuzer J”. Her initial name was “Wilhelm von Tegetthoff” to commemorate the Battle of Lissa and to concile the good will of Austria, but it was seen at the time as an insult to Italy, and not to hamper relations with mussolini the more neutral “Prinz Eugen” was chosen, this time to please Hungary and commemorate the imperial KuK Kriegsmarine. The name was a hommage to Prince Eugene of Savoy, an illustrious 18th-century general in the service of Austria.

She was launched on 22 August 1938 and Ostmark Governor Arthur Seyss-Inquart made the christening speech, with in attendance the Regent of Hungary Admiral Miklós Horthy, which commanded SMS Prinz Eugen in WWI and his wife Magdolna Purgly which broken the traditional bottle. She had a straight stem corrected in completion by a clipper bow and raked funnel cap. The was the last cruise of the class to be built with this bow. The next Seydlitz and Lützow would have a clipper bow from the start.

A Royal Air Force attack on Kiel had her damaged while in completion in the night of 1st July 1940. After a delay she was commissioned on 1 August 1940 and spent the remainder of the year in Baltic sea trials, then in Jan-Feb. 1941, she started gunnery training. After post-fixes in dry dock and some improvements by April she joined the freshly completed and commissioned KMS Bismarck for joint maneuvers in the Baltic, both being selected for Operation Rheinübung.

However on 23 April, while off Fehmarn Belt off Kiel she hit a magnetic which damaged her fuel tank, propeller shaft couplings but also fire control and so the operation had to be postponed for repairs. Admirals Erich Raeder and Günther Lütjens also wanted to delay further to have Scharnhorst (also repaired) part of it, or even Tirpitz, to get a sizeable core. That certainly have changed completely the course of the events. However Raeder and Lütjens urged for a new surface action in the Atlantic, with Hitler breething hard behind them. At the time, Prinz Eugen was under command of Kapitän zur See Helmuth Brinkmann from August 1940.

Operation Rheinübung

On May 18, 1941, Prinz Eugen and Bismarck, left Gdingen (Gotenhafen), proceeding to the Skagerrak. British reconnaissance spotted them on their way. This part has been covered already with the Bismarck’s post, so we will focus here on Prinz Eugen alone.

On 23 May, Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen to increase speed to 27 knots for the Denmark Strait dash, with the FuMO radar set at max power. Bismarck led Prinz Eugen from 700 m in the mist, but ice forced them to 24 knots and they ended north of Iceland, zigzaging between ice floes. At 19:22, hydrophone and radar operators spotted HMS Suffolk from 12,500 m and Prinz Eugen’s radio-intercept team decrypted her radio signals, learning they had been spotted and surprised was gone.

Admiral Lütjens gave permission for Prinz Eugen to engage Suffolk, but Captain Brinkmann held fire due to the heavy mist. Suffolk retreated before she could fire and continue to shadow both ships.