The “pocket battleships” of the Reichsmarine

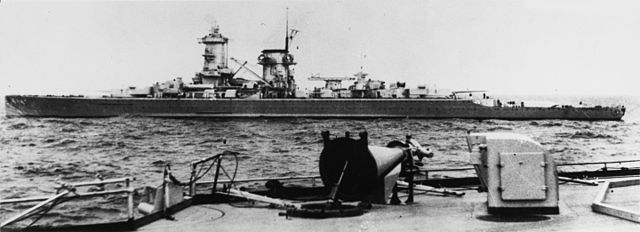

These ships were mostly made famous by the Graf Spee in the southern Atlantic, in the first naval battle of ww2, at the river plate in 1939. She somewhat eclipsed the other two: Scheer and Deutschland (later renamed Lützow). Indeed the three were designed during the “rebirth” of the German Navy and despite the Versailles’s treaty strict limitations (way stricter than the Washington treaty), which applied to Germany after the first were lifted after the 1935 Anglo-German naval agreement. The idea of the “Panzeschiffe” as called in the German terminology, incorrectly dubbed “pocket battleships” by the press in 1939 were the attempt of doing more on a very limited displacement. Before the Washington treaty, no Navy went so far in this area, and all three were not designed as proper battleships but emerged as their own concept: Powerful, long range commerce raiders designed to fight cruisers and to flee battleships. Their natural predators at the time were battlecruisers, but the only ones in existence with the Royal Navy were kept at Scapa Flow.

At any rate, with the Deutschland class, German engineers managed the impossible. But in practice their battle records was somewhat disappointing. Submarines and civilian commerce raiders did more, with less, to disrupt the allied trade lanes. Nevertheless, they became the springboard on which were developed the Scharnhorst class and battlecruisers projects of plan Z.

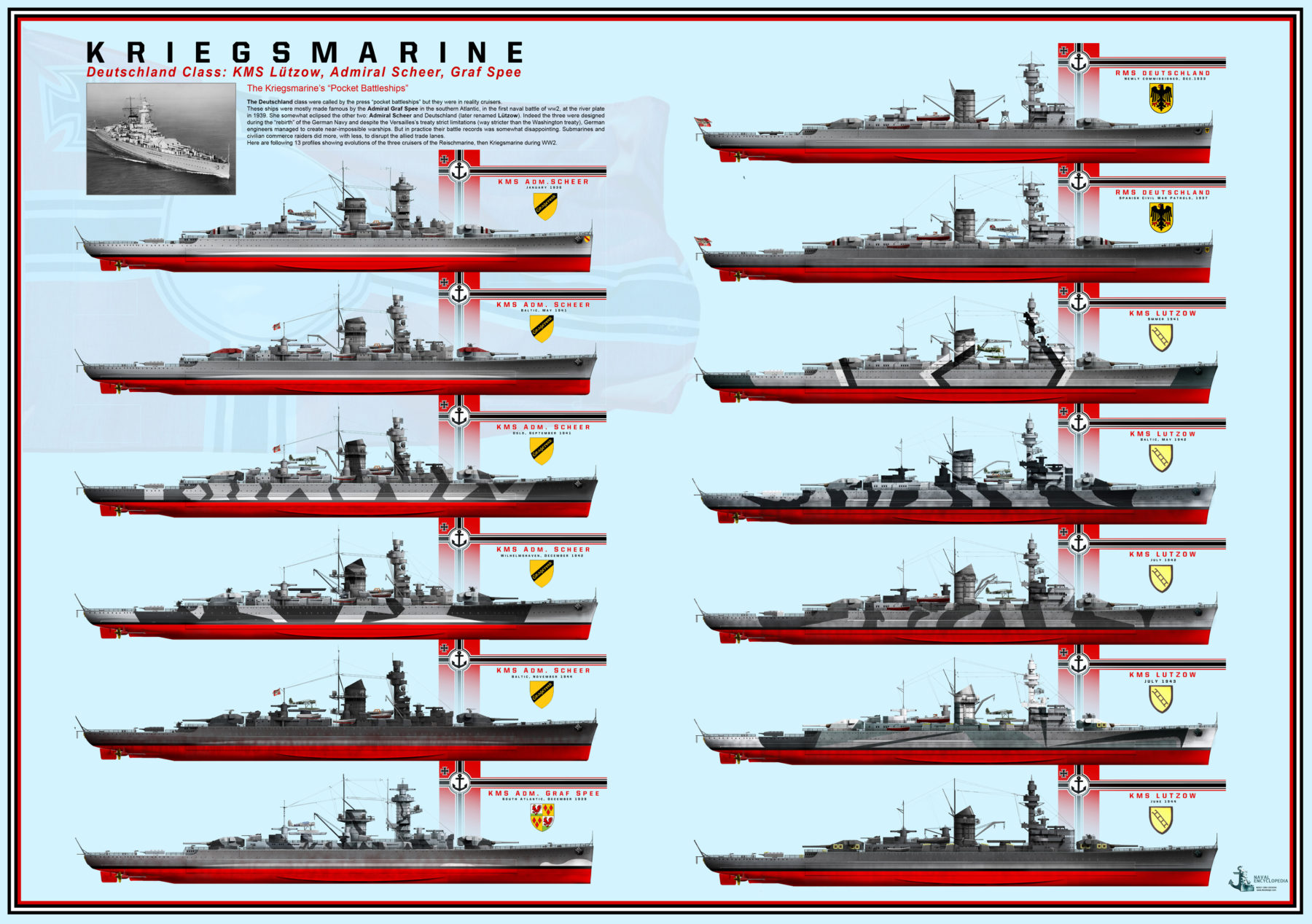

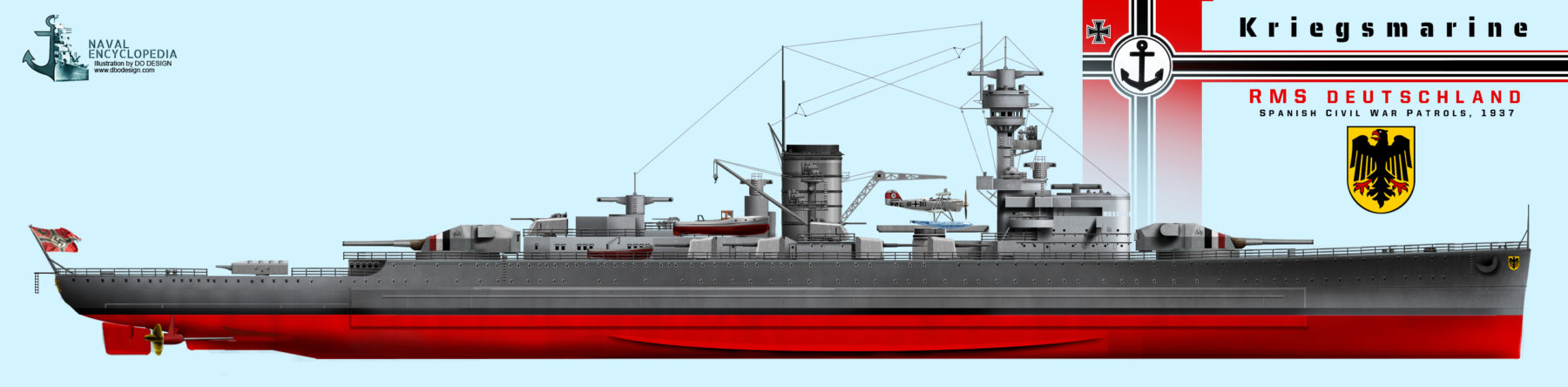

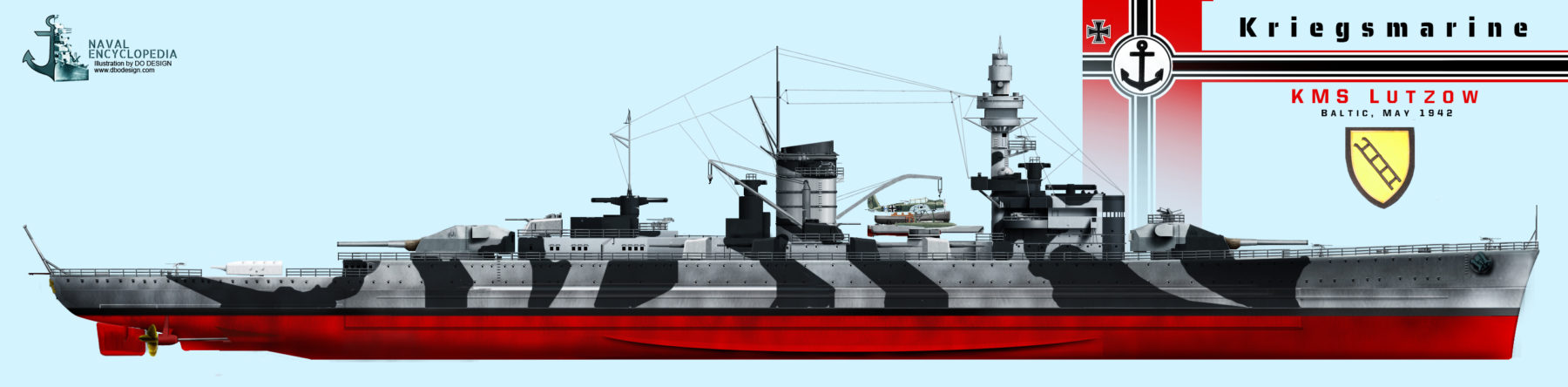

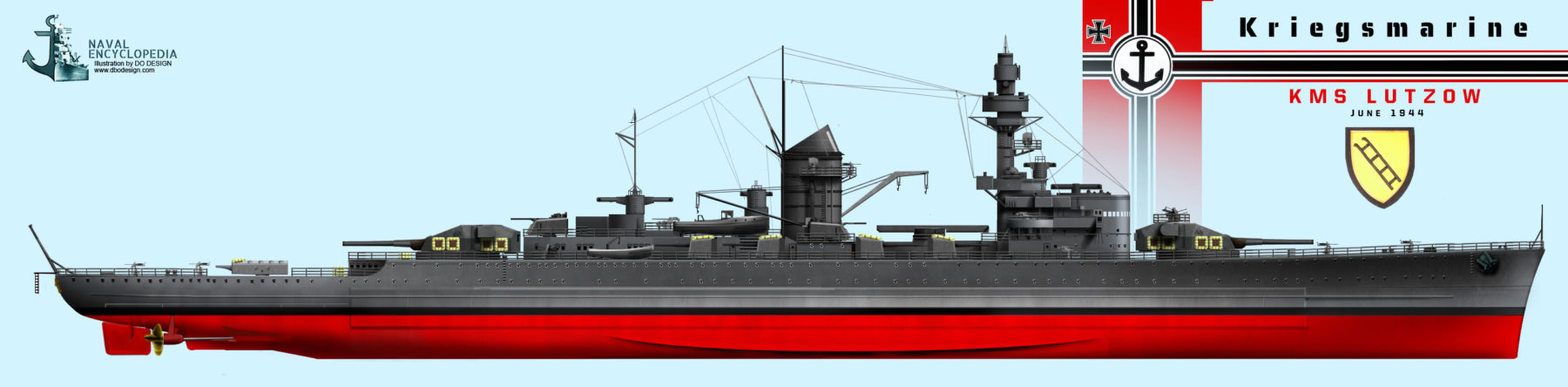

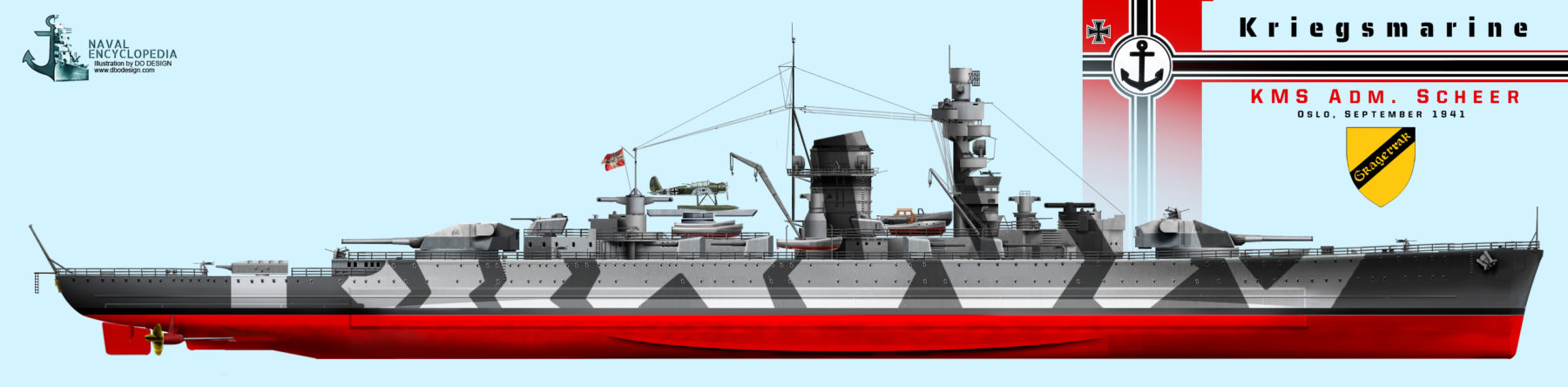

Poster of the Deutschland class, all camouflage liveries and evolution

Development history

There are many common developments between the Scharnhorst class and earlier commerce raider projects. Emerging from the Versailles treaty, the Reichsmarine or “state navy” of a democratic, republican Germany, was severely limited in size and quality, with just six pre-dreadnought, six light cruisers and a handful of torpedo boats, also obsolete. The flower of the Kaiserliches Marine, largely untapped by WWI was laying at the bottom of Scapa Flow in the cold, barren and windy Orcades Islands. It was agreed the oldest “capital ships” were scheduled for replacement when twenty years old. But by treaty, Germany was not authorized a ship larger than 10,000 tonnes standard. Of course potential rivals by then had no limitations and the race for 50,000 tonnes leviathans was on, until limited to 35,000 long tons by the Washington Naval Treaty. Gun caliber was not regulated by Treaties for Germany, but under the strict supervision of the Naval Inter-Allied Commission of Control (NIACC). They indeed had full authority to regulate any new armament planned in the Reischmarine, and the 28 cm caliber already used by the pre-dreadnoughts seemed a good limitation, agreed by all. The Allies’s hoped these limitations would limit the German Navy to a typical Scandinavian coastal navy.

By that time, RMS Preussen (laid down 1902) approached its replacement date in 1922. The earliest design studies started in 1920, and the admiralty worked on two simple options: Either the new Reichsmarine was to build a heavily armored, but slow and and small warship related to Scandinavian coastal battleships like the Sverige class (Gustav V was in completion at that time, and around 7,000 tonnes) or a large and fast but lightly protected ship related to a cruiser. The first studies on the first option started in 1923 under Admiral Paul Behncke. But by 1924, the German economy virtually collapsed, and all work was halted. Admiral Hans Zenker then took command of Reichsmarine, and immediately pressed on to resume design work. By 1925 at last the first three proposals were drafted, added to the 1923 studies, for five different design philosophies.

By that time, RMS Preussen (laid down 1902) approached its replacement date in 1922. The earliest design studies started in 1920, and the admiralty worked on two simple options: Either the new Reichsmarine was to build a heavily armored, but slow and and small warship related to Scandinavian coastal battleships like the Sverige class (Gustav V was in completion at that time, and around 7,000 tonnes) or a large and fast but lightly protected ship related to a cruiser. The first studies on the first option started in 1923 under Admiral Paul Behncke. But by 1924, the German economy virtually collapsed, and all work was halted. Admiral Hans Zenker then took command of Reichsmarine, and immediately pressed on to resume design work. By 1925 at last the first three proposals were drafted, added to the 1923 studies, for five different design philosophies.

-Design 1923 “I/10” 32-knot (59 km/h; 37 mph) cruiser, eight 20.5 cm (8.1 in) guns

-Design 1923 “II/10” 22-knot (41 km/h; 25 mph) well armored ship, four 38 cm (15 in) guns.

In addition, I/10 had turbines, oil-only boilers for 80,000 shp and 4×2 210 or 208 mm turrets, plus 4x 88m, 8x50mm

II/10 had turbines steam turbines with boilers burning coal and oil for 25,000 shp, 22 knots, 2×2 150mm, 2x 88m, 2x50mm

-Design 1925 “II/30” had six 30 cm (12 in) as IV and V. here are the details:

-II/30 – Diesel 24,000 shp 21 knots, 3×2 305 mm turrets, 4x 105mm

-IV/30 – Same, 2×3 (all fore) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150mm, 4x 105mm

-V/30 – same, 2×3 (1 fore, 1 aft) 305 mm turrets, 6x 150mm 3x 88mm

-I/28 – same, same as above, 2×2 150 mm, 6x 88mm

-II/28 – same, 3×2 (2 offset aft) 305 mm turrets, 4x 150 mm, 4x 88mm

-VI/30 – same, 2×2 (1 fore, 1 aft) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150 mm, 4x 88mm

The Reichsmarine eventually settled as said above for the 28 cm (11 in) caliber, well known and for which still existed molds and machining, so not to provoke the Allies. This also lifted the burden for the engineers to design and develop, adapt to their design a brand new gun. From first draft to delivery, a new gun in peacetime could be a five years enterprise. In addition, although light, the trusted German 28 cm guns had a better muzzle velocity, so potentially better range compared to the British 12 in (305 mm) before WW1, and better anyway than 8-in guns, and with mount and breech block improvement, could also be as fast as a heavy cruiser gun.

The Reichsmarine held a conference to evaluate these designs in May 1925. Results were inconclusive, and affected by the recent French occupation of the Ruhr industrial area, the result of payment default, and depriving Germany of any option of delivering quickly a large-caliber artillery. The design staff prepared two more designs:

-Design 1925 “I/35”: A heavily armored ship with a single triple turret forward

-Design 1925 “VIII/30”: Less armour but two twin turrets.

The VII/30 walked on Diesel engines for a total output of 24,000 shp providing 21 knots, and two forward 12-in (30.5 cm) main turrets, 2×2 150 mm, 4x 88mm

VIII/35 design also used a Diesel but output halved at 16,000 shp, for 19 knots, a triple forward 305 mm turret, and 6x 88mm

VIII/30 also used Diesel but output reached 36,000 shp for 24 knots, with a two twin 305 mm turrets configuration, same secondaries.

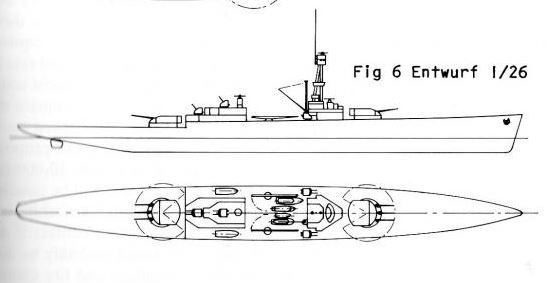

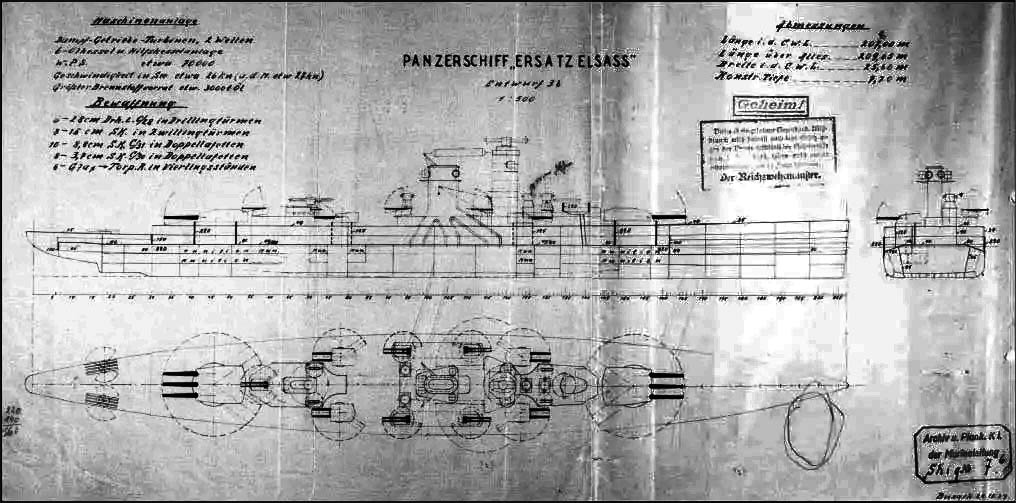

Design (‘Entwurf’) I/M26, alternative proposal for the Panzerschiffe

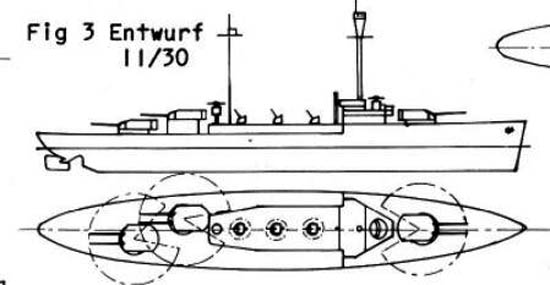

Entwurf II/30, one of the early designs, had six 305 mm/280 mm main guns in three twin turret and a top speed about 24-26 knots, and a 100 mm armor belt

Reichsmarine’s admiral Hans Zencker wanted to lay down the first of these in 1926, but the design still needed to be finalized. The Reichsmarine 1926 maneuvers had some interesting retuens: One was that a greater speed was desirable. So two new designs were prepared, closing in on the definitive concept:

-Design 1927 “Panzerschiff A”: Prepared in 1926, its first draft was ready in early 1927, but it was finalized in 1928. In between, admiral Zenker announced on 11 June 1927 that the Reichsmarine settled on the definitive armament, two triple turrets with 28 cm guns. This gave the:

-I/M26 Diesel 4,000 shp, 28 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 280 mm turrets, 4×2 120 mm DP, 6x 37mm

-II/M26 Diesel 54,000 shp, 28 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 280 mm turrets, 4×2 120 mm DP, 6x 37mm

Entwurf-3-b (): A possible successor of the Deutschland class, Similar but with larger displacement, higher speed and better Armor, up to 220mm for the armor belt.

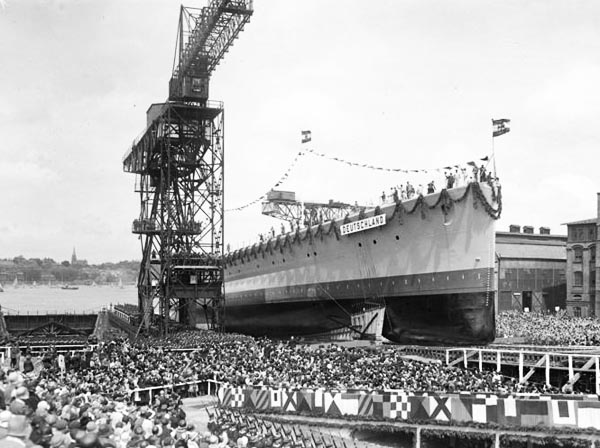

Political opposition to the new design was considerable and in order to quell them, the Reichsmarine delayed the order until after the Reichstag elections of 1928. Social Democrats notably strongly opposed the new ships and campaigned with “Food not Panzerkreuzer.” By May 1928, the elections saw a majority in favor of the ships (notably twelve seats to the Nazi Party), and in October 1928, the Communist Party initiative of a referendum against it failed. The lead ship was at last authorized in November 1928. Of course, as soon as the the particulars of the design were known by the Allies, they tried to halt their construction. The Reichsmarine offered to comply in exchange of Germany being levelled up to the Washington Treaty, and with a ratio of 125,000 long tons (127,000 t) compared to UK’s 525,000 long tons (533,000 t) for capital ship tonnage, abrogating the Versailles Navy clauses altogether. Although Great Britain and the United States were ready to make concession, France refused to bulge (there was also the question of war reparations). Nevertheless, these new “Panzerschiffe” did not violate per se the Treaty, so the Allies had no ground to interdict them after failing to negotiated a settlement. Soon, Deutsche Werke, Kiel was granted a contract for the construction of “Deutschland”, laid down on 5 February 1929, the only one started in the “roaring twenties”. The next two by Reichsmarinewerft in Wilhelmshaven, with a one year gap. The lead ship name was obvious, but for the next, to proclaim a lineage with historical figures not so long ago now dead and honored, the next were named about admirals: Reinhard Scheer, in charge of the Hochseeflotte during the war, and Graf (Count) Maximilian Von Spee, the famous commander of the East Asia Squadron. Two of these ships were completed before the Reichsmarine transitioned to the Kriegsmarine, and Hitler was present for the two launches (1st April 1933 and 30 June 1934) and at the commissioning of Deutschland in April 1933 (He was elected in March 1933).

Why “Panzerschiffe” ? Since the parliament was “sold” to these ships the name was mostly a question of prestige for the German population at large. They were armoured indeed, but just slightly more than an average heavy cruiser and could have been compared to a sort of “armoured cruiser” in the old sense, although protection did not match the main caliber guns by a long shot. The Kriegsmarine reclassified them as “Kreuzer” anyway during WW2. They displaced even less than the heavy cruisers of the Hipper class.

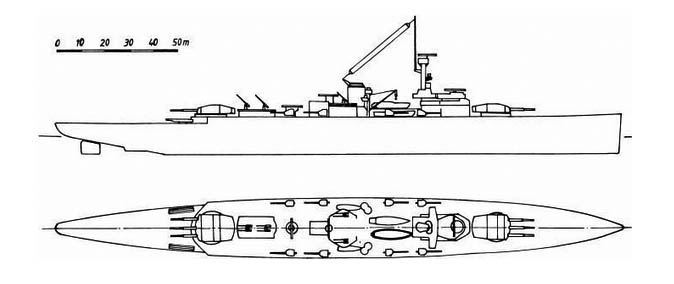

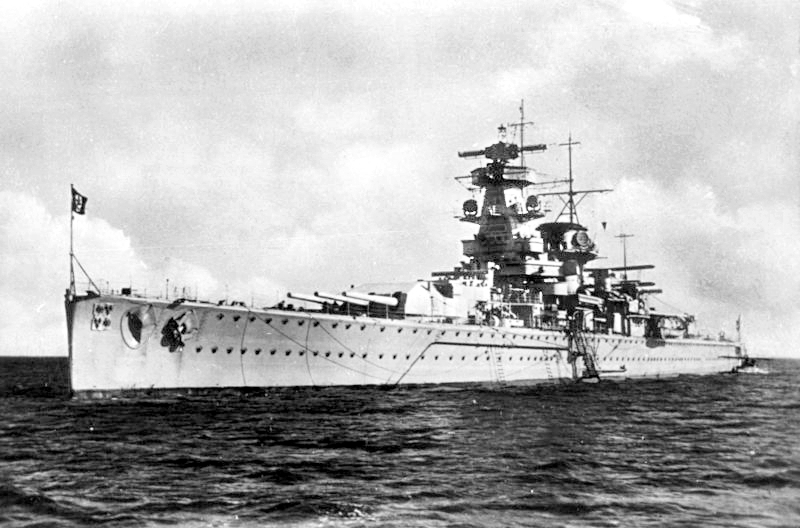

Design

The Deutschland-class varied slightly in dimensions, although all reached 181.70 meters (596.1 ft) long at the waterline and 186 m (610 ft 3 in) overall. Deutschland and Admiral Scheer had limited “clipper” bows installed in 1940–1941 so to reach 187.90 m (616 ft 6 in). The beam varied from 20.69 m (67 ft 11 in) on Deutschland to 21.34 m (70 ft 0 in) (Scheer) and the “fattest”, 21.65 m (71 ft 0 in) Graf Spee. Deutschland and Scheer draft in standard was 5.78 m (19 ft 0 in), 7.25 m (23 ft 9 in) FL while Admiral Graf Spee was slightly deeper at 5.80 m and 7.34 m FL. Displacement also diverged, and in addition, increased over time, from 10,600 long tons (10,800 t) on the lead ship to 11,550 long tons on Scheer and 12,340 long tons on Graf Spee, no less than two thousand tonnes more, mostly explained by their beam. Fully loaded it was 14,290, 13,660, 16,020 long tons. Indeed from 1933 Hitler took little care of sparing the allies and allowed to blatantly ignore Versailles limitations for the next two ships. This was confirmed anyway after the London treaty of 1935. Officially, still, as published in international specialized publications, all where stated to be 10,000 long tons standard.

Their hulls were constructed with transverse steel frames and like light cruisers, 90% were assembled by using welding, saving 15% weight. This allowed both more for armament and armor. As designbed their normal peacetime crew comprised 33 officers and 586 ratings. From 1935 it was increased to 30 officers and 921 to 1,040 sailors and as squadron flagship, 17 more officers and 85 sailors went on board. These ships carried boats installed between the main bridge and funnel, two picket boats, two barges, one launch, one pinnace, and two dinghies.

Sketch of “Panzerschiff A” – src Pocket Battleships of the Deustchland class, Koop & Schmolke – Seaforth Publishing > scribd

Main features

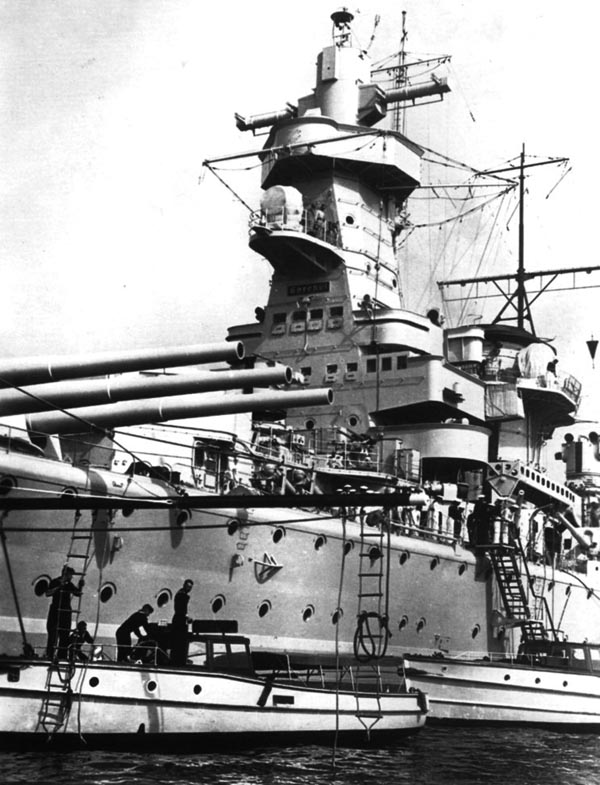

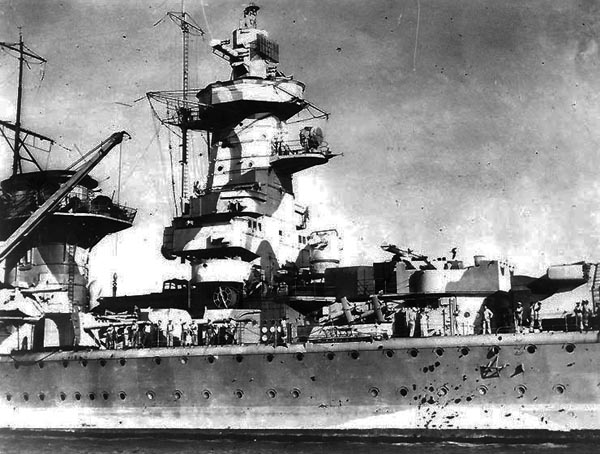

Close view of the Graf Spee’s bridge. The last two of the class had this particular bridge instead of the simpler structure of Deustchland, dictated by weight savings;

Powerplant

Sun Tse allegedly said “be like the water, fight the weak, flee the strong”. The Deutschland class was very much inspired by this concept. It needed to be more powerful than any cruiser, yet fast enough to distance any battleship. That was also the essence of battlecruisers. This made them perfect commerce raiders, as it was rare to protect convoys with battleships. And as commerce raiders, the most important was not speed, but range. It was the main reason of their adoption of diesel engines. They were more frugal than steam turbines.

Their machinery spaces housed four sets of 9-cylinder, double-acting, two-stroke diesel from MAN. This choice was a radical innovation, contributing as well as welding to save weight. Each set was connected to a transmission built by AG Vulcan. Two diesels were paired on two propeller shafts. At the end of these, three-bladed propellers 4.40 m (14 ft 5 in) in diameter. Initially 3.70 m (12 ft 2 in) propellers were intended, but replaced soon before lauch. Total output for all diesels was 54,000 metric horsepower (53,261.3 shp; 39,716.9 kW). This resulting in a top speed of 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) on paper. It was less than cruisers of the time, capable of 30 knots, the main tradeoff of diesel engines. Output figures on trials happened to be weaker than expected, but they exceeded nevertheless their design speeds. Total output achieved was 48,390 PS (47,730 shp; 35,590 kW) for the lead ship, 52,050 PS/28.3 knots for Scheer, and 29.5 knots as recorded for Graf Spee.

Various details of the ships

Autonomy was permitted thanks to 2,750 t (2,710 long tons) of fuel oil carried, enabling a top range of 17,400 nautical miles (32,200 km; 20,000 mi) at 13 knots. At 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), it fell to 10,000 nmi. Admiral Scheer carried less fuel, at 2,410 t for range of 9,100 nmi at 20 kn. Graf Spee carried not much at 2,500 t for even less, 8,900 nmi. Electric output came from four Siemens electric generators rated at 220 volts, powered by diesels. Total output was 2,160 kW (Deutschland), 2,800 kW (Admiral Scheer), 3,360 kW (Admiral Graf Spee).

On trials, they revealed themselves as good sea boats, with just a slight roll caused by their slender hull. They were wet in rough sea however, especially the low stern, although mitigated by the adjunction of a clipper bow in 1940–1941. They were very agile despite having a single, but large rectangular rudder, helped by the diesel engines, as half could be reversed, ensuring very tight turns. They heeled over up only to 13 degrees in a hard over turn, not affecting much their aiming.

Armament

Main armament:

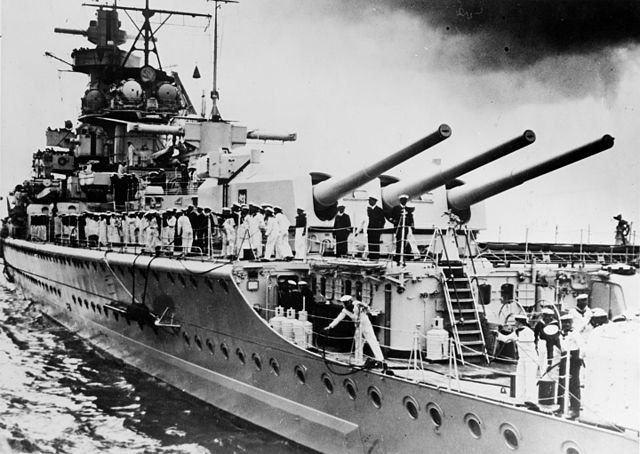

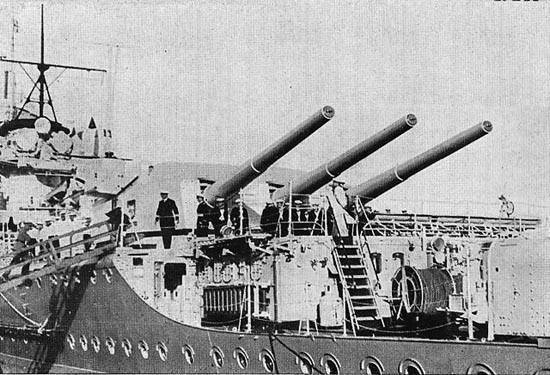

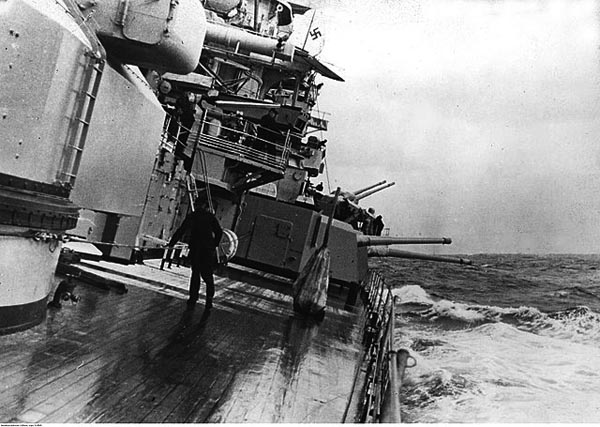

Rear triple 280mm turret of the Lützow

Certainly the trump card of the design: They carried as much firepower as three pre-dreadnoughts, by having no less than six 28 cm guns. To reach this level, this main battery of of SK C/28 guns was mounted into just two turrets but triple mounts (with independent elevation). They were mounted for and aft, and to make room for the large barbette yet keeping slender hull lines, the latter was sloped downwards. These turrets of the Drh LC/28 type allowed an elevation of 40°, and a depression to −8°, providing a top range of 36,475 m (39,890 yd). For comparison, the County class cruisers’s own 8-in guns -their probable adversaries- were limited to 28 km. So they were completely out-ranged. This was even better than the Queen Elisabeth’s own BL 15 in guns, at 33,550 yards (30,680 m), and only for the Mk XVIIB/Mk XXII streamlined shell. These figures improved even for the next Scharnhorst class. These guns fired a 300 kg (660 lb) AP shell at 910 meters per second (3,000 ft/s) and 630 rounds were stored in peacetime, later raised to 720 shells during WW2.

Secondary armament:

There was a battery of eight 15 cm SK C/28 guns: They were fitted in single MPLC/28 mounts due to the lack of space for twin turrets, and arranged amidships along the superstructure. Elevation was 35°, depression −10°, range 25,700 m (28,100 yd) and a total of 800 rounds of ammunition were carried in peacetime, yet again raised during the war to 1,200 rounds. These were HE shell weighing 45.3 kg (100 lb), existing the barrel at 875 m/s (2,870 ft/s).

Tertiary armament:

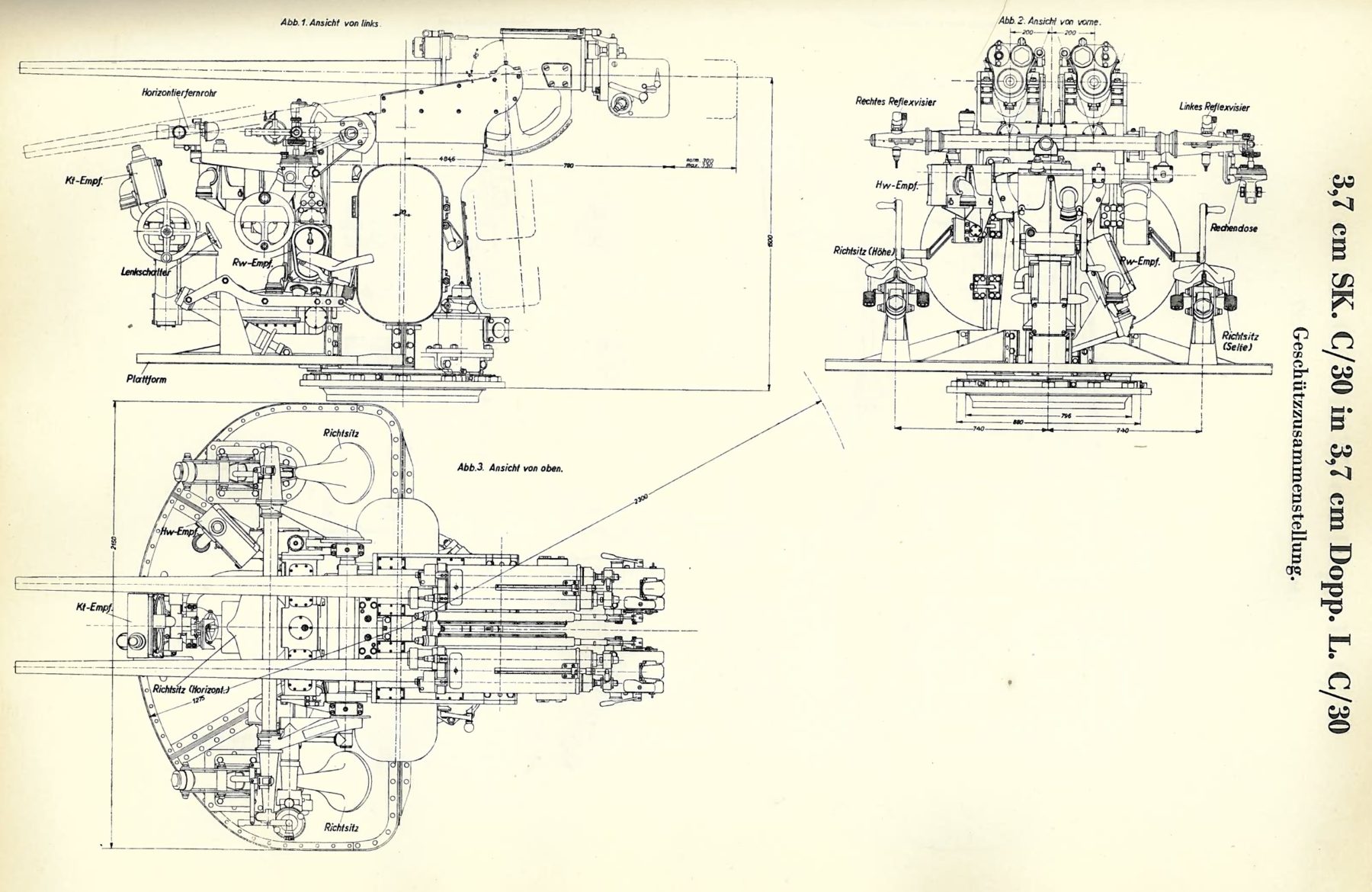

The anti-aircraft battery originally comprised three 8.8 cm SK L/45 AA guns in single mounts, the classic solution retained by all previous German ships. Obsolete, thet were replaced in 1935 by six 8.8 cm SK C/31 guns, this time in twin mounts.

Graf Spee and Deutschland were rearmed in 1938 and 1940 with six 10.5 cm L/65 guns in twin mounts, one amidship on platforms at roof superstructure level, one aft on the centerline on the quarterdeck roof, and four 3.7 cm SK C/30 guns, completed by ten single 2 cm Flak guns. On Deutschland the latter were augmented to 28 during the war, whereas Admiral Scheer was only rearmed by 1945, with six single 4 cm (1.6 in) guns and eight 3.7 cm guns (four twin) plus thirty-three 2 cm FLAK guns.

As an argument also to destroy some of their targets, all three vessels were provided two quadruple 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes banks, placed at the stern. In heavy weather, their use was downright dangerous, as they could impact after launch a wave and detonate prematurely.

Armour Protection

The weaker part of the design, constrained by the treaty. Fortunately the choice of diesels and welding reduced their toll on the displacement, allowing to increase protection figures. Here are the detailed figures of the design, nearly identical for all three ships*:

-Main armored belt, sloped: 80 mm (3.1 in) amidships, tapered down to 60 mm (2.4 in) beyond the citadel.

-The bow and stern: unarmored.

-Longitudinal splinter bulkhead: 20 mm (0.79 in).

-Upper deck: 17-18 mm (0.6-0.7 in)

-Forward conning tower: 150 mm (5.9 in) walls, 50 mm (2.0 in) roof,

-Aft conning tower: 50 mm walls, 20 mm (0.79 in) roof.

-Main battery turrets: 140 mm (5.5 in) faces, 85 mm (3.3 in) sides, 85-105 mm (3.3 to 4.1 in) roofs

-Barbettes: 100 mm walls over the deck

-15 cm guns shields: 10 mm (0.39 in) gun shields.

-Torpedo bulkheads: 40-45 mm (1.8 in).

*The upper edge of the belt on the first two ships was at the level of the armored deck but on Graf Spee it was one deck higher. Also the lead ship had 45 mm bulkheads but 40 mm on Admiral Scheer and Graf Spee. They also had and armoured deck reduced to 17 mm (0.67 in) in thickness, intermediate decks ranging from 17 to 45 mm. On the first two its did not extend over the entire width but it was the case on Admiral Graf Spee. Torpedo bulkheads also for the first two stopped at the double-bottom but for Admiral Graf Spee, it extended to the outer hull.

Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee had some improvements in armor thickness. Deutschland’s barbettes of 100 mm were of 125 mm for her sisters. Admiral Graf Spee had a 100 mm belt and its main armored deck was reinforced by strays of 70 mm in some place. So she was arguably the one with the best armour characteristics, able to mitigate or stop 8-in rounds.

On all three ships, the hull was divided into twelve watertight compartments and below their double bottom extended on 92% of the hull’s total lenght.

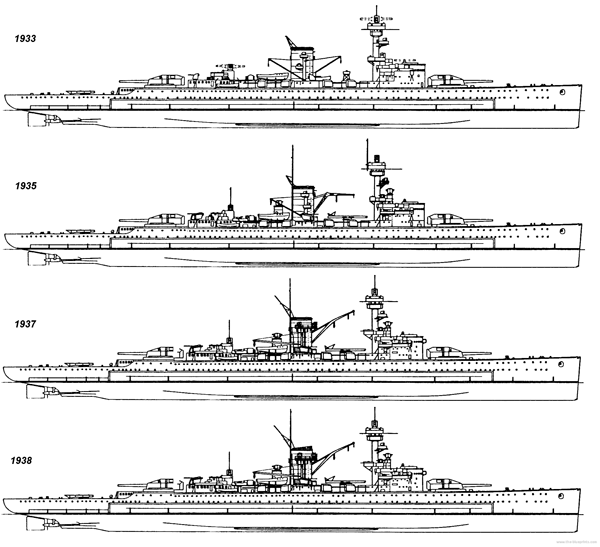

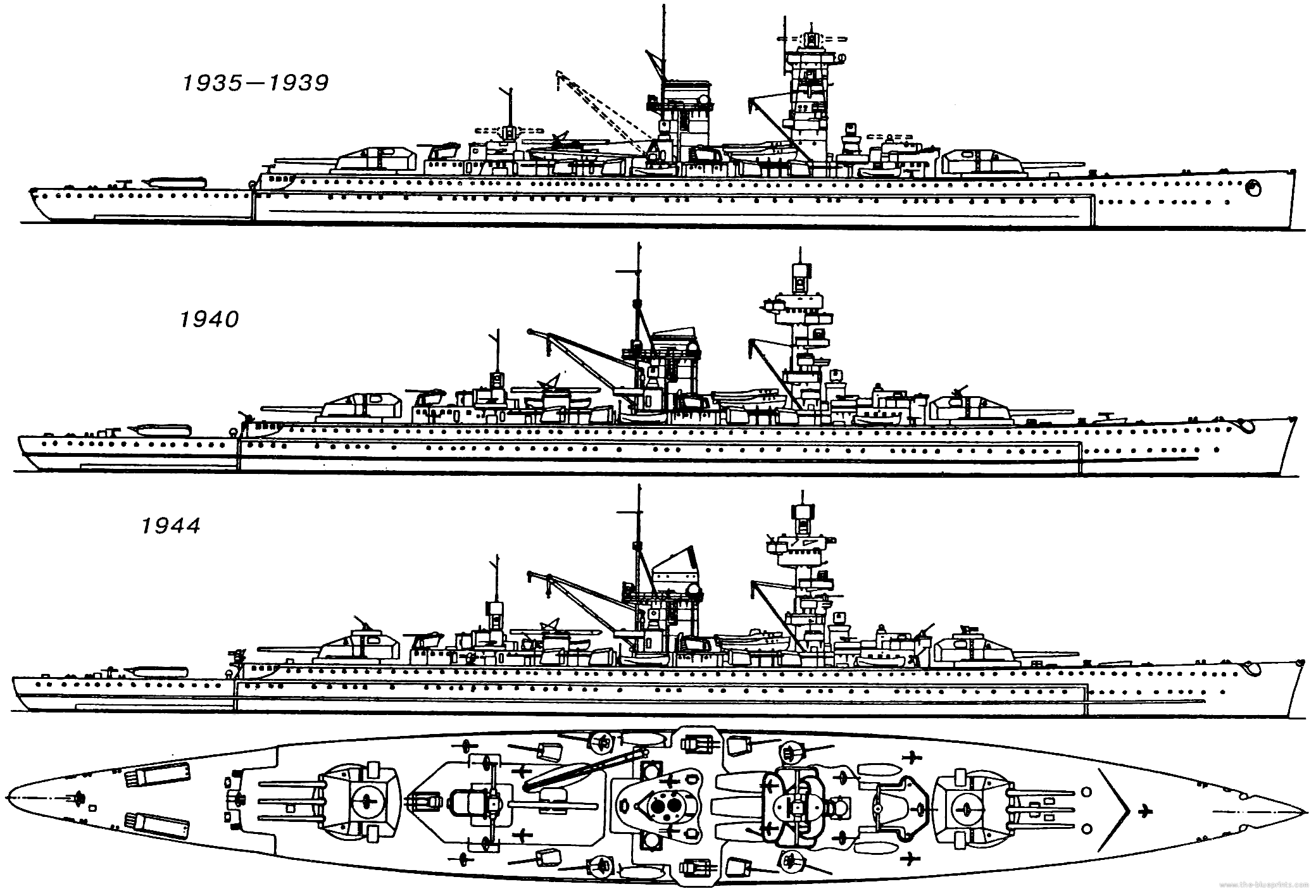

Evolution of the Deutschland, to Lützow (the blueprints)

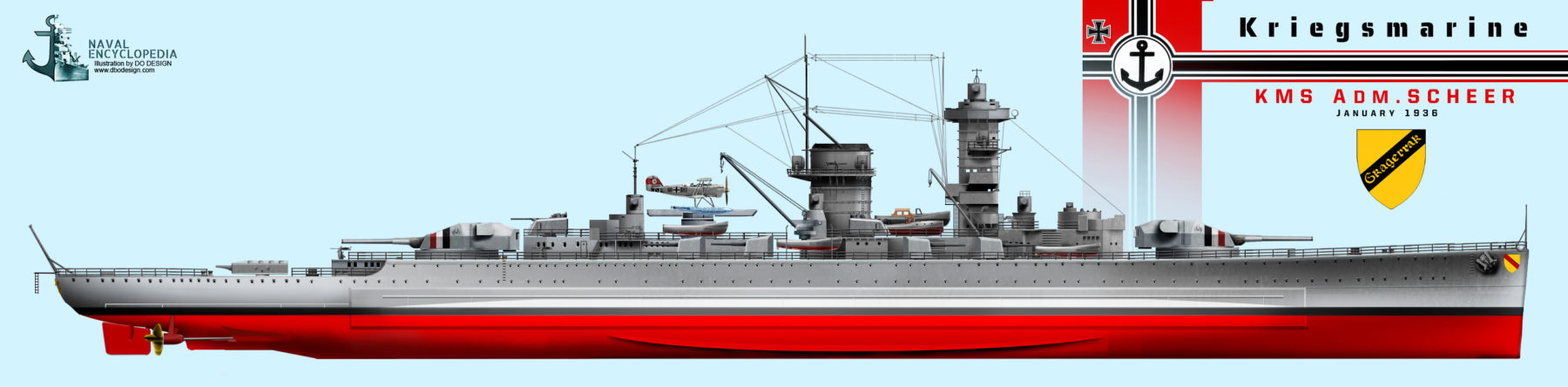

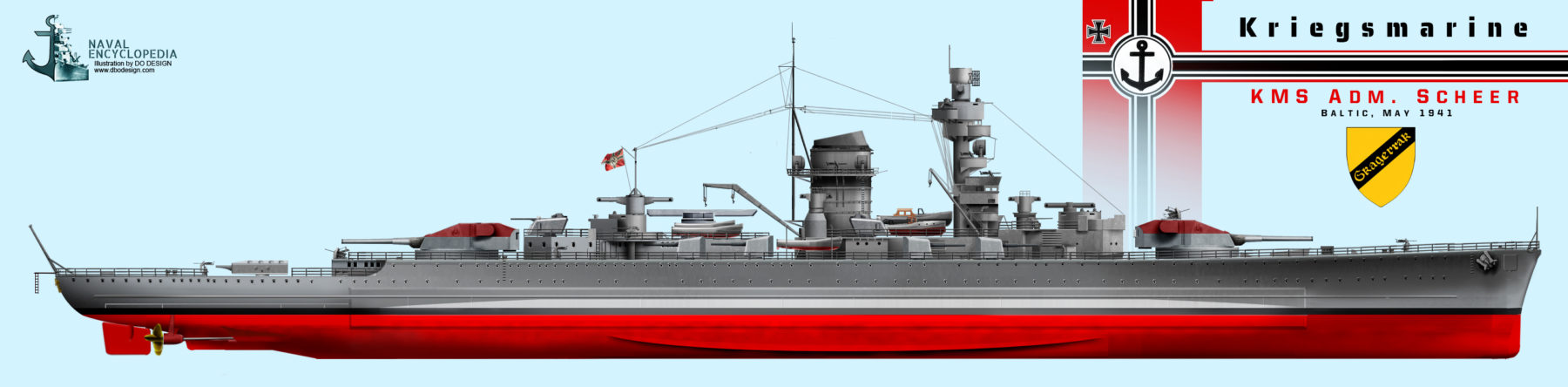

Evolution of the Admiral Scheer (the BP)

Construction and fate

RMS Deutschland was laid down at the Deutsche Werke shipyard, Kiel in February 1929 and her contract name was “Panzerschiff A”, nominally replacing the old Preussen and in the yard, known as construction number 219. Launched on 19 May 1931, she was christened by German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning but accidentally started sliding down during his speech. Sea trials started in November 1932 and she was commission on 1 April 1933. Despite of this, political opposition grew to such a point the Admiral Scheer narrowly escaped cancellation; The Social Democrats indeed abstained from voting, leaving the communists alone. “Panzerschiff B” was nevertheless delayed until 1931 despite the yard was available at Wilhelmshaven. Scheer replaced Lothringen, and she was laid on 25 June 1931 (construction number 123), launched on 1 April 1933, christened by Marianne Besserer (daughter of Admiral Scheer), completed on 12 November 1934, and commissioned the same day.

Lastly, the third sister ship was authorized this time without much fuss, but from the same yard, waiting the basing to be free. She was known under the contract name “Panzerschiff C”, replacing Braunschweig. Laid on 1 October 1932, under construction number 125, launched on 30 June 1934, she was christened by the daughter of Maximilian von Spee, and completed on 6 January 1936, commissioned the same day.

By late January 1943, commerce raiding had proved a failure and Hitler wanted the two remaining ships to be scrapped. The admiralty preferred to have them converted as light fleet aircraft carriers instead. Admiral Raeder ordered plans to be prepared. For this, their the hulls were to be lengthened by 20 meters (66 ft) and many more modifications made, using 2,000 tons of steel while it was estimated a two years work. They would have shared many characteristics with the KMS Seydlitz, also converted from 1942, but the overall cost and duration of this project meant it was dropped and both ships spent the rest of their career idle in port.

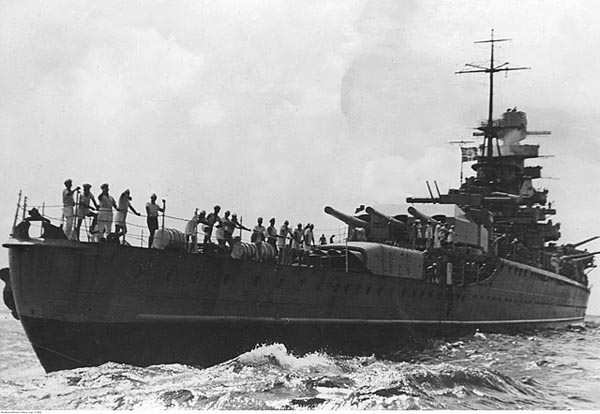

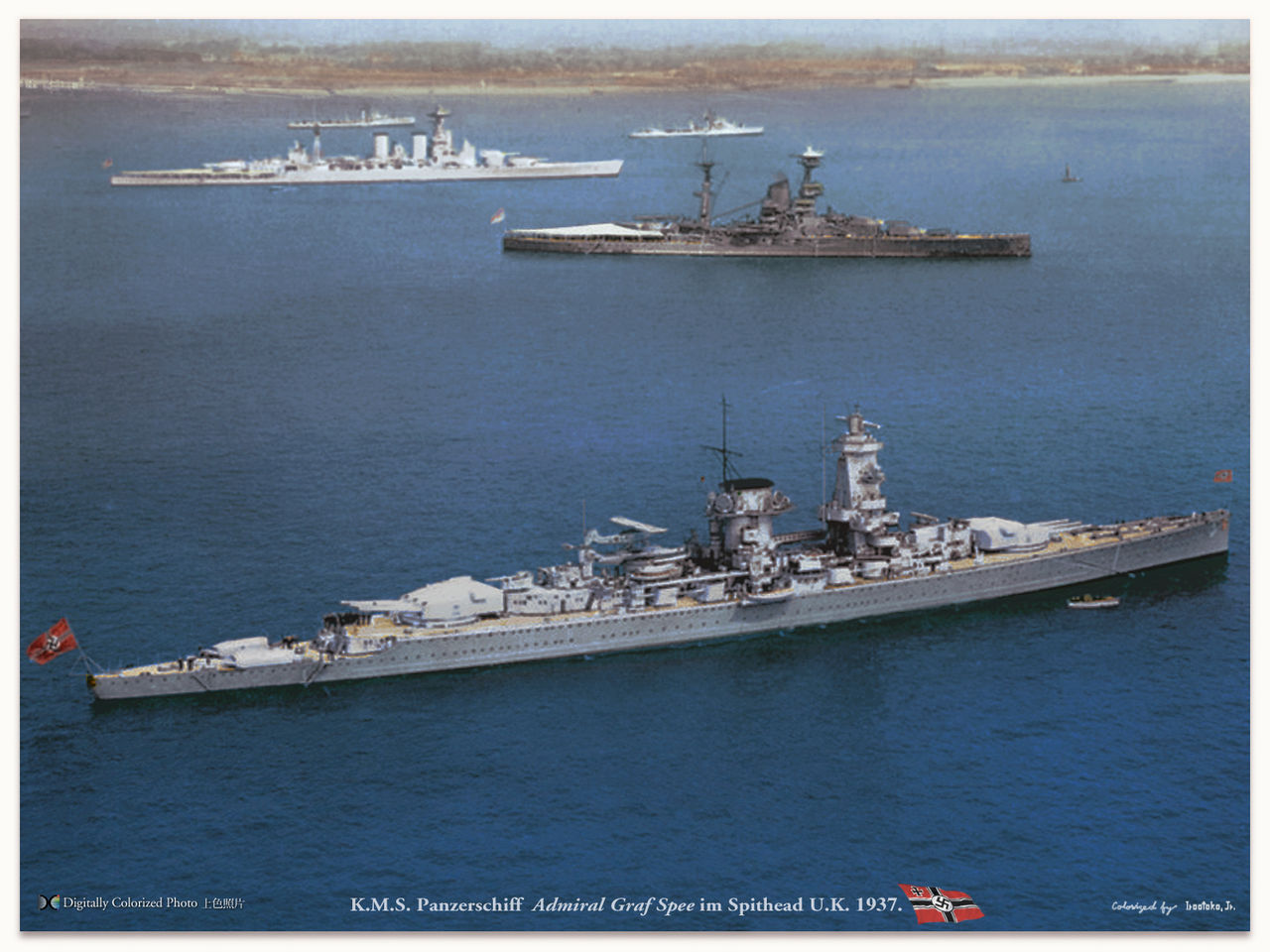

KMS Graf Spee at the May 1937 Spithead coronation review

KMS Deutschland specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 186 x 20.69 x 7.25 m |

| Displacement | 10,600 tons standard, 14,290 tons FL |

| Crew | 33+586, see notes |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 4 diesels 9-cyl MAN, 54,000 shp |

| Speed | 28 knots (42 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Armament (1933) | 2×3 280 mm, 8 x 150 mm, 3 x 88 mm AA, 2×4 TT 533 mm |

| Armament (1939) | same but 2×3 105 mm AA, 8×2 37mm AA, see notes |

| Armor | Belt: 76-80 mm (3 in), Deck: 38-45 mm (2 in), Turrets 140 mm (5.5 in), Conning tower: 152 mm (6 in) |

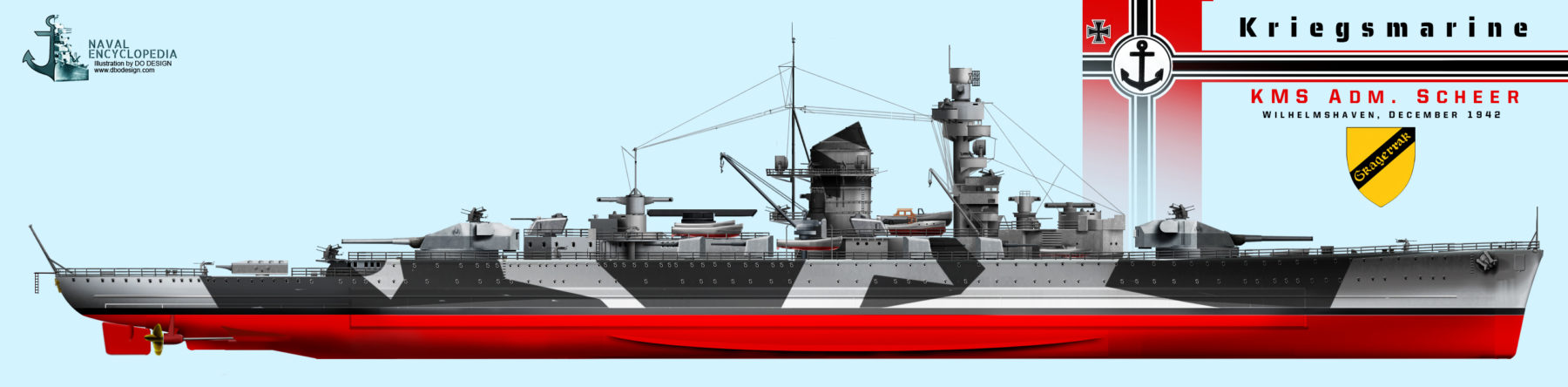

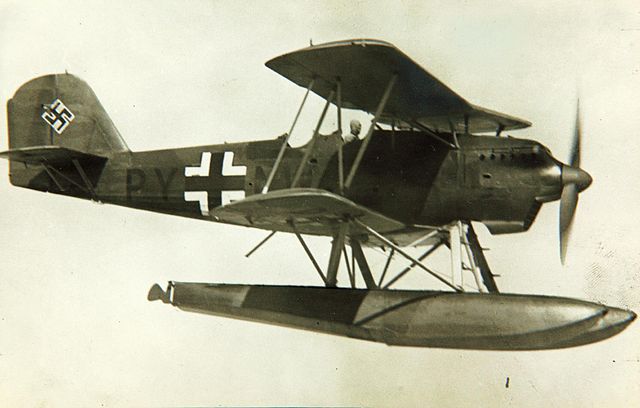

KMS Graf Spee in 1939, with its superstructures-only green camouflage

KMS Admiral Scheer en 1944, with dark gray Northern Sea type straight angular striped pattern.

Author’s old illustrations

Sources/read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutschland-class_cruiser

J. Gardiner’s Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

https://www.forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=244056

http://www.ww2ships.com/germany/d-ch-001-b.shtml

https://www.navalanalyses.com/2016/05/infographics-21-deutschland-class-heavy.html

https://www.world-war.co.uk/bb/deutschland_class.php

https://ww2db.com/ship_spec.php?ship_id=C167

https://www.chuckhawks.com/deutschland_class.html

https://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail.asp?ship_id=KMS-Deutschland-Lutzow

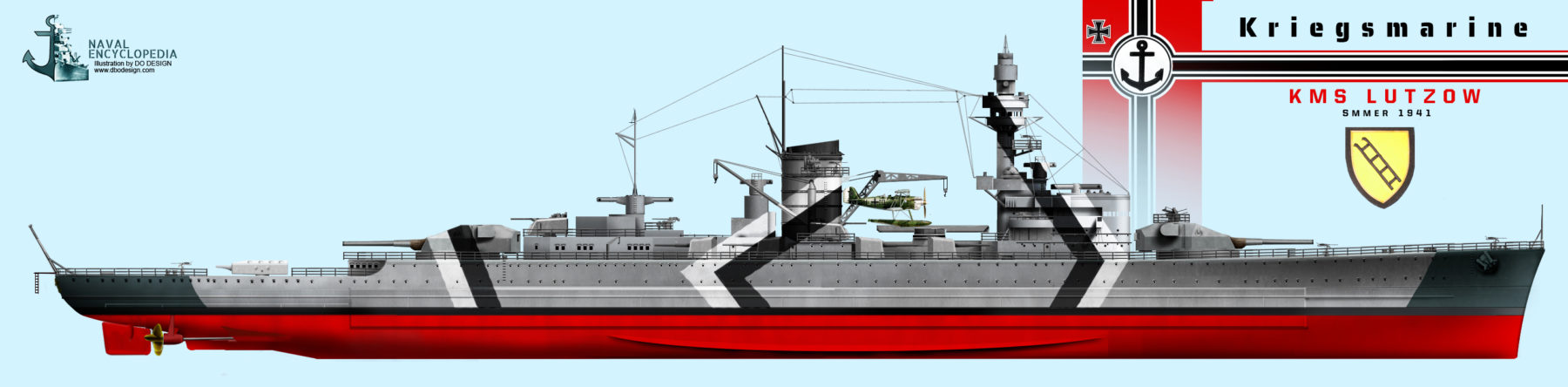

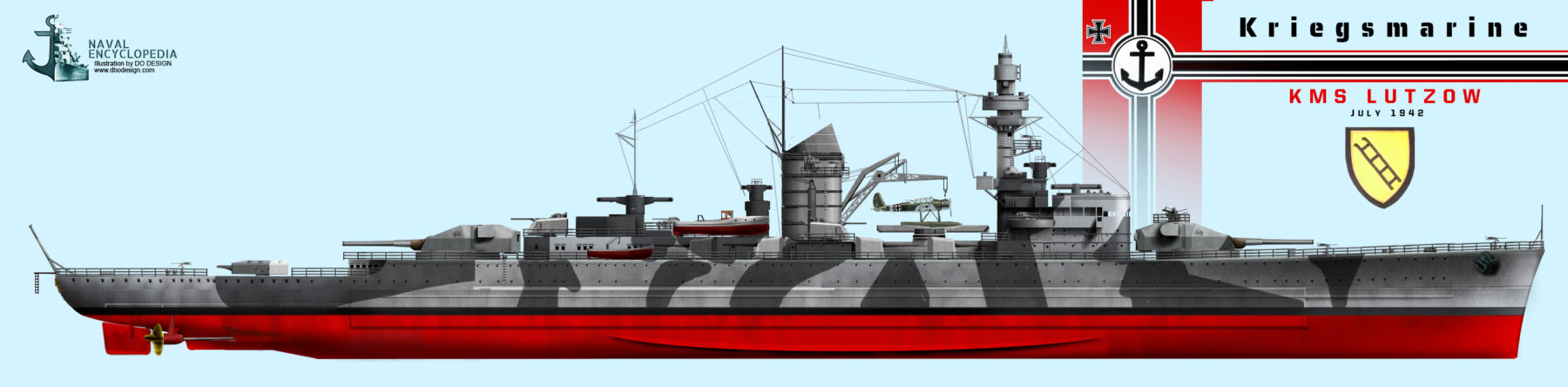

Naval Camouflages of the Lützow, Scheer and Graf Spee

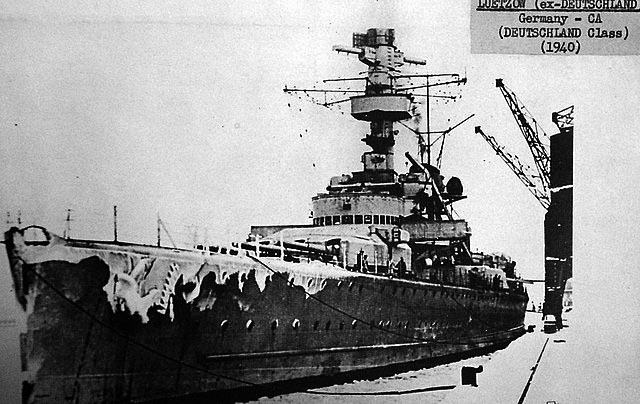

Lützow in 1942

Lützow in the summer of 1943, one of the rare color photos of the time, allowing to discern four colors: Medium grey, white, medium blue-grey, and dark grey. Both were adaptated to the northern lights.

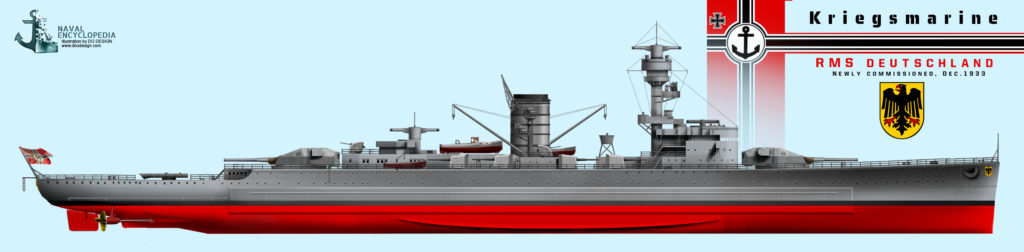

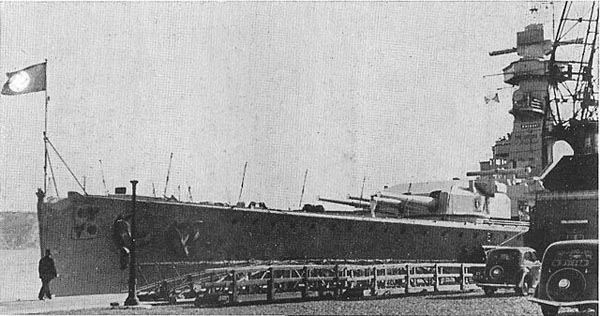

RMS Deutschland in December 1933 as commissioned

KMS Deutschland during the Spanish civil war in 1937. Note the neutrality bands using the old colors of red, black and white.

Lützow in the Baltic, May 1942

Lützow in June 1944, her last known camouflage pattern

KMS Admiral Scheer, Oslo September 1941

KMS Admiral Scheer, Wilelmshaven, December 1942, major modernization

KMS Admiral Scheer, in the Baltic, November 1944

KMS Admiral Graf Spee, South Atlantic December 1939

Videos:

The D class by Drachinfels

KMS Scheer in completion at Wilhelmshaven in 1934

KMS Graf Spee burning in Montevideo

Books:

Bidlingmaier, Gerhard (1971). “KM Admiral Graf Spee”. Warship Profile 4. Windsor: Profile Publications.

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battlecruisers of the World. Translated by Alfred Kurti. London: McDonald & Jane’s.

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe. 5. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag.

Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1976). Die Deutschen Seeflieger 1935–1945 (in German). Munich: Lehmann.

Jane’s Fighting Ships. London. 1939.

Meier-Welcker, Hans; Forstmeier, Friedrich; Papke, Gerhard & Petter, Wolfgang (1983). Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648–1939. Herrsching: Pawlak.

O’Brien, Phillips Payson (2001). Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. London: Frank Cass.

Pope, Dudley (2005). The Battle of the River Plate: The Hunt for the German Pocket Battleship Graf Spee. Ithaca: McBooks Press.

Prager, Hans Georg (2002). Panzerschiff Deutschland, Schwerer Kreuzer Lützow : ein Schiffs-Schicksal vor den Hintergründen seiner Zeit (in German). Hamburg: Koehler.

Preston, Antony (1977). Battleships 1856-1977. Phoebus Publishing Co.

Preston, Antony (2002). The World’s Worst Warships. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press.

Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Pocket Battleships 1939–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Various views of the Graf Spee on world of warships

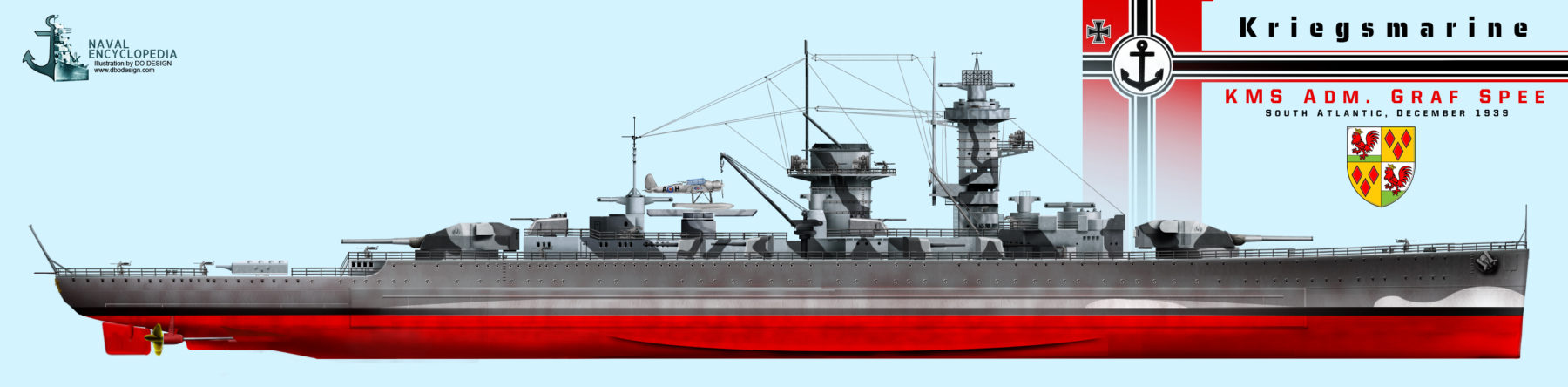

Model Kits

On scalemates.com model kit database

I made the Italeri kit of the Graf Spee, nice detail for the time. It is now distributed by World of Warships.

First Published July 22, 2016.

KMS Deustchland (Lützow 1941)

KMS Deutschland in 1936, with the early superstructure design

Here in Naples in 1938 during one of her numerous good will visits

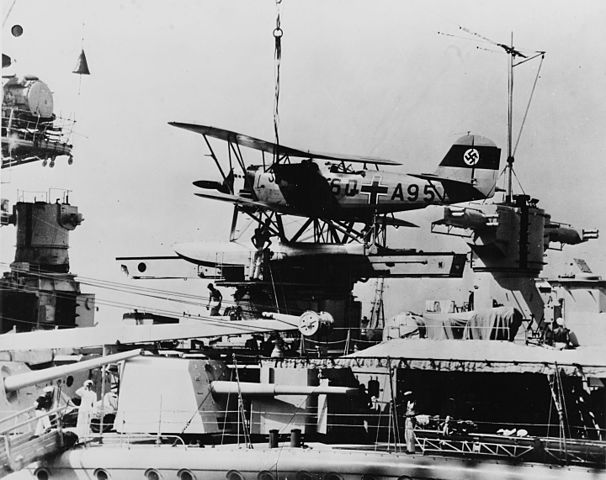

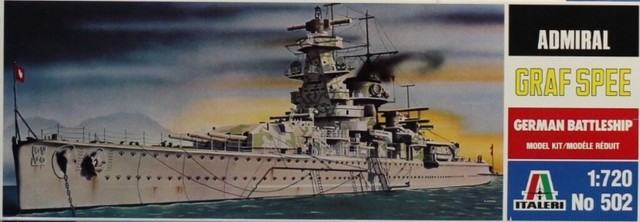

KMS Deutschland started her sea trials began in November 1932, to be commissioned on 1st April 1933, so five months later, which quite long for post-trials fixes. This time was spared on the next ships of the class. KMS Deutschland spent both 1933 and 1934 in training manoeuvrers in the Baltic and home waters. Speed trials indicated that the best speed to spare machinery was 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) and in December 1933 she was at last ready for active service. As it was peacetime, the ship was proudly featured in the German medias of the time, as a symbol of the rebirth of the German Navy. Bearing the name of the country, she also became its ambassador around the world, and made a series of goodwill visits, starting with Gothenburg in Sweden. In April 1934, Adolf Hitler visited the ship. In October 1934, she made a state visit to Edinburgh. In 1935 she started a series of long-distance training voyages into the Atlantic, starting with the Caribbean and South American waters. After routine maintenance work back in Germany she saw the installation of extra equipment, a new fire control system and a catapult fitted between her main bridge and funnel. She received two Heinkel He 60 floatplanes. At the beginning of 1936 she participated in fleet manoeuvers in German waters, soon joined Admiral Scheer. Both started a cruise in the Atlantic which brought them to Madeira.

Heinkel He 60 floatplane. The three ships kept these until the end of their operations

The Spanish Civil War and “Deutschland incident”

KMS Deutschland off spain in 1936

The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, and Deutschland, Admiral Scheer were deployed on its atlantic coast from 23 July 1936. They were part of a multinational naval force tasked by the league of nations to to conduct non-intervention patrols and prevent arms deliveries to both sides. For this, KMS Deutschland received large black, white and red bands on her main turrets for aerial identification, called “neutrality bands”. All present nations did the same. She evacuated refugees and under orders started protect German ships carrying supplies for Francisco Franco’s Nationalists, infringing deliberately the neutrality policy. She also gathered intelligence for the Nationalists, using her spoter planes for reconnaissance.

In May 1937, the ship she was docked in La Palma, Majorca island with other neutral warships (notably British and Italian) when attacked by Republican aviation. Her anti-aircraft crews were scrambled into action, and the planes were driven off. As it was felt other Republican attacks were possible, the torpedo boats Seeadler and Albatross joined Deutschland in Ibiza on 24 May. And indeed, another Republican bombers raid (two SB-2 bombers) flown by Soviet Air Force pilots deliberately targeted the ship. The first bomb penetrated her upper deck, close to the bridge, managing to detonate below the thin main armored deck. The second hit the third starboard 15 cm gun, starting a massive fire below deck. This left a tolly of 31 dead and 74 among the crew.

KMS Deutschland, Library of Congress archives

Fearing other air attacks the ship was ill-prepared to fight, her captain ordered to lift anchor and left. She met Admiral Scheer and proceeded to Gibraltar to bury the dead with a ceremony, and start provisional repairs. Hitler ordered them to be exhumed and repatriated in Germany. Wounded sailors were treated in Gibraltar’s hospital. Hitler was adamant Admiral Scheer must retaliating by shelling the Republican-held port of Almería in retaliation but orders were intercepted by Stalin to forbid attack on German and Italian warships, while Molotov made an apology.

In 1938-1939 KMS Deutschland made training maneuvers with the fleet and further goodwill visits (like at Naples). She made another visit to Spain after the Nationalist victory and participated in a large fleet exercise with Admiral Graf Spee, Köln, Leipzig, Nürnberg, destroyers, U-boats, and support vessels. This was the largest Atlantic German fleet manoeuver before the war.

Operations of 1939

On 24 August 1939, Deutschland left Wilhelmshaven to find a useful spot south of Greenland, waiting for orders as the war was imminent. From there she would be able to prey on merchant traffic and the supply ship Westerwald was assigned to her. Her captain however was ordered to observe prize rules, meaning intercepting, warning, stopping and search ships for contraband, and only afterwards to sink them after ensuring their crews were evacuated in boats with a heading and life support. She was ordered to avoid combat with even inferior naval forces, so to keep away from cruisers and destroyers. Hitler still at this point hoped to secure a negotiated peace with Britain and France and Deutschland only was greenlight to start operations by 26 September. At that time, Deutschland had chosen the Bermuda-Azores sea lane as an hunting area. On 5 October, she sank the British transport Stonegate, but the latter managed to send a distress signal. Deutschland next turned north, and headed for the Halifax route. On 9 October, she met the US 4,963 GRT City of Flint. The freighter inspected revealed “contraband” and was seized and escorted back to Germany via Murmansk, seized by Norway and later returned to the original crew. On 14 October, she sank the 1,918 GRT Norwegian Lorentz W Hansen and intercepted and inspected the Danish steamer Kongsdal, which later warned the British Royal Navy, confirmed Deutschland’s position and heading back to the North Atlantic.

Severe weather however aborted this raiding mission.

1940 Operations of Lützow

Meawnhile, The French Force de Raid (Battleship Dunkerque’s task force) protected convoys around UK and was dispatched to search for the Deustchland. In early November because of this, she was recalled home by the Naval High Command, reaching Gotenhafen on the 17. For a first mission, this was meagre. In 1940 she was overhauled, gaining a raked clipper bow and new AA. She was both re-rated as heavy cruiser and renamed KMS Lützow as Hitler feared the propaganda effect if she was sunk. Erich Raeder pushed also for this, knowing it would cause some confusion for Allied intelligence. Indeed the name was already affected to one of the Admiral Hipper-class cruisers sold to the Soviet Navy and wanted to hide the transaction. Lützow left the drydock on March 1940, and was tasked for another raid in the South Atlantic but in April she was redirected to support the invasion of Norway.

Operation Weserübung

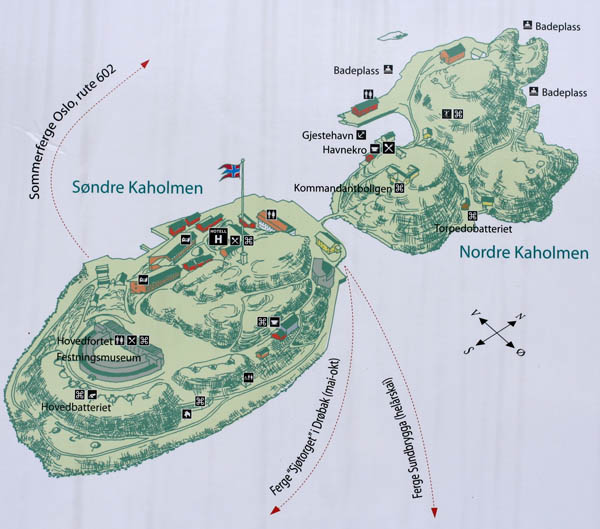

Lützow was assigned to Group 5 with Blücher and Emden (Konteradmiral Oskar Kummetz). Group 5’s main mission was to capture the capital Oslo, and for this carried 2,000 mountain troops, Lützow for her part having 400 of these, disembarked by using her own boats. Leaving on 8 April and crossing the Kattegat, the flotilla was attacked en route by HMS Triton, but the later missed. just before midnight on 8 April Group 5 passed the outer ring of Norwegian coastal batteries, Lützow in line behind Blücher, and Emden astern at 12 knots. between heavy fog and neutrality rules of engagement, the Norwegians which had these ships in their scopes, had to fire warning shots first. But it was not to be. Oscarsborg Fortress, on high alert, however and they opened fire without warning with their 28 cm, 15 cm and 57 mm guns. This was the Battle of Drøbak Sound. Blücher was shell hit and take also two torpedoes hits, causing large flooding. She listed rapidly and capsized with most of crew, including the soldiers.

Oscarborg Fortress (src www.tallgirlsfashion.no)

Lützow was also hit, three times and by 15 cm shells (Oscarsborg’s Kopås battery), on her forward gun turret (center and right guns HS), the second hit penetrated both decks and started a fire in her hospital and operating theater. The third struck her superstructure (close to the port-side aircraft crane), burning a plane, killing four gunners. At that point, she pointed her aft turret at the fort and opened fire but also her captain ordered she reversed course with the rest of the squadron, and later landed her troops in Verle Bay and then covered them by providing fire support. On 9 April, thes Norwegian fortresses were captured and negotiations for surrender started. Lützow was ordered at that point to return to Germany for repairs. What left of Group 5 resumed operations meanwhile, centered on Emden. En route to Germany, Lützow, at full speed, was interecpted by the submarine HMS Spearfish. On 11 April she launched her torpedoes and scored a hit, destroying Lützow’s stern while her steering gear was blown off and seriously jammed. Dead in the water, the cruiser had to be towed back to port. There, she was decommissioned for repairs lasting a year. Lützow’s commander nevertheless was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his actions at Drøbak Sound, taking command of the task force after the flagship Blücher was lost.

Deustchland in ice, winter 1939-1940 (ONI)

Operations of 1942

Lützow was recommissioned on 31 March 1941 while another commerce raiding mission as planned, with Admiral Scheer. On 12 June, she headed for Norway with destroyers, but the RAF sent torpedo bombers, which attacked her off Egersund. They scored a single torpedo hit, disabling all her electrical system while she took a severe list to port. Her port shaft was damaged as well. Emergency repairs were done as she could reach Germany and stayed in Kiel for six months, basically emerging again only on 10 May 1942. It was decided to send her to Norway again.

Leaving Kiel on 15 May 1942 she arrived and mer Scheer on 25 May in Bogen Bay. The became flagship of Vizeadmiral Kummetz (Kampfgruppe 2) but both vessels were now plagued by Fuel shortages. Both Lützow and Admiral Scheer made some limited training exercises but stayed inactive, that is until Kummetz received detailed on Operation Rösselsprung. It was a planned attack on the convoy PQ 17 heding for Murmansk. On 3 July, Kampfgruppe 2 departed to soon be lost in heavy fog. Lützow and three destroyers ran aground, suffered significant damage. Meawnhile tBritish intelligence was warned of this, and decided to scatter the convoy. As surprise was lost, the destruction of PQ 17 was turned to U-boats and the Luftwaffe. It was a cranage, as 24 ships out of 35 transports were efectively sunk as a result. Lützow returned to Germany for repairs again, lasting until the end of October 1942. She was back in Norway on 12 November, but based in Narvik.

ONI recoignition photograph of KMS deutschland, date unknown

On 30 December, she made another sortie with Admiral Hipper and six destroyers. This was Operation Regenbogen, the attack of convoy JW 51B. Kummetz wanted to divide his forces, sending Hipper and three destroyers north first, drawing away the escorts while Lützow and three destroyers would attack later from the south. At 09:15, 31 December, HMS Obdurate spotted the german destroyers screening forward of Admiral Hipper, and the destroyers opened fire as soon as she was spotted. The convoy was defended by five destroyers and they all rushed to join the fight. HMS Achates however laid a smoke screen to cover the convoy, and as planned, Kummetz turned back, trying to draw the destroyers away while Captain Robert Sherbrooke (the escort commander) ordered two destroyers to stay behind in case. The remaining four were steaming north. Lützow was in sight of the convoy at 11:42 and opened fire, but visibility was poor as customary in the area in winter, with heavy weather and high waves. Accurate fire was near impossible. She stopped firing at 12:03, failing to observe any hits.By then, Rear Admiral Robert Burnett’s Force R, (cruisers Sheffield and Jamaica) in distant support until then rushed to the fight, and engaged Admiral Hipper, achieving complete surprise. Lützow was ordered to break off and rish to help Admiral Hipper, and inadvertently came alongside bioth British cruisers and engaged them. British cruisers then turned their fire on Lützow, as Hipper, and Burnett quickly decided to withdraw, having a hard time with his puny 6 in (150 mm) guns. Later, Kummetz ordered the reunited force to head back to Norway. Needless to say, the failure to sink a single ship in the convoy infuriated Hitler which showed a bout of unalterated rage, ordering the while surface fleet to be scrapped for spare metal. Kummetz was sacked, Raeder resigned, replaced by Karl Dönitz. It was the later, despite his personal agenda with the submarine force, which pleaded hitler to spare the surface fleet and persuaded him to use different tactics.

Late career 1943-45

By March 1943 Lützow was based in Altafjord. But at that time, it was not fuel shortage but her worn out diesel engines which had her inoperative. Undergoing a thorough invertigation, the propulsion system was declared unreliable and needed a complete overhaul. After staying in Norway until September 1943 as an immobile deterrent (the allied had no idea she was unable to sail out), she was sent back in Germany and the overhault ended by January 1944. She was in the Baltic for post-overhaul trials and training cruises with new naval personnel. However she would never return to Norway. On one hand, it was considered she would be transformed as an aicraft carrier, but the idea was both costly and labout-intensive and the project was dropped. Instead, she was left at anchor in Kiel, inactive for the remainder of 1944 and early 1945.

Bundesarchiv, the wreck of Lützow in Kiel in April 1945 after being hit by a Tallboy bomb

On 13 April 1945, the RAF launched a massive night bomber raid, Avro Lancaster attacked Lützow and Prinz Eugen, with poor results due to a covered sky. On 15 April, another raid showed the same result. On 16 April however the weather improved just enough for eighteen Lancasters from 617 (“Dambusters”) squadron hit Lützow with a single Tallboy bomb (plus 3-4 near misses that seriously shook her) as she was berthed to the Kaiserfahrt. She sank in shallow water, her hull still 2 m (6 ft 7 in) above water, rendering her a stationary gun battery. She would soon shell the advancing Soviet forces (Task Force Thiele) until 4 May 1945, until renuuing our of battery ammunition. The crew was tasked to scuttle her, but a fire prematurely exploded the charges. Peace was signed in Europe, and Lützow waiting her fate, seized by the Soviet Navy. Sources are diverging at this point, if she was raised in September 1947 and BU in 1948–1949. It was discovered later in dclassified Soviet archives that she was sunk in weapons tests in the Baltic Sea, off Świnoujście (Poland) on 22 July 1947.

KMS Lützow in the Kaiser canal, next to the craters of RAF’s Tallboy bombs.

KMS Admiral Scheer

RMS (‘ReichsMarine Schiff’) Admiral Scheer was ordered from Reichsmarinewerft shipyard, Wilhelmshaven. The bill ordering her was delayed for obe year, and budget for Panzerschiff B “Ersatz Lothringen” only secured by poltical absention. On launching, she was christened by Marianne Besserer, daughter of the namesake Admiral Reinhard Scheer and completed by 12 November 1934, commissioned the same day. The political context had changed radically by then. Her first command was Kapitän zur See Wilhelm Marschall. She spent December 1934 in sea trials and training and in 1935, as the navy was to be renamed Kriegsmarine, a catapult and landing sail system as fitted. Contrary to her earlier sister ship she was not given He-60 floatplanes but Arado models instead, better fitted to operate in heavy seas. Until 26 July 1937 her captain was Leopold Bürkner, future head of foreign intelligence. In October 1935, she started her first long range cruise, stopping at Madeira and other ports and back to Kiel in November. She then departed for a summer cruise between the English Channel and the Irish Sea, and stopped in Stockholm when back.

RMS (‘ReichsMarine Schiff’) Admiral Scheer was ordered from Reichsmarinewerft shipyard, Wilhelmshaven. The bill ordering her was delayed for obe year, and budget for Panzerschiff B “Ersatz Lothringen” only secured by poltical absention. On launching, she was christened by Marianne Besserer, daughter of the namesake Admiral Reinhard Scheer and completed by 12 November 1934, commissioned the same day. The political context had changed radically by then. Her first command was Kapitän zur See Wilhelm Marschall. She spent December 1934 in sea trials and training and in 1935, as the navy was to be renamed Kriegsmarine, a catapult and landing sail system as fitted. Contrary to her earlier sister ship she was not given He-60 floatplanes but Arado models instead, better fitted to operate in heavy seas. Until 26 July 1937 her captain was Leopold Bürkner, future head of foreign intelligence. In October 1935, she started her first long range cruise, stopping at Madeira and other ports and back to Kiel in November. She then departed for a summer cruise between the English Channel and the Irish Sea, and stopped in Stockholm when back.

Like her sister ship Deustchland, Scheer was deployed in Spain by July 1936, mainly to evacuate German civilians in areas close to the frontline. On 8 August 1936 she served with Deutschland enforcing non-intervention patrols, making four tours of duty, until 1937, officially to prevent arms smuggling, but she reported Soviet ships with supplies and protected German ones. Ernst Lindemann (future captain of Graf Spee) was her first gunnery officer during that time. After “Deutschland incident” on 29 May 1937, Admiral Scheer was ordered to shell Almería in reprisal and started at 07:29, on shore batteries, naval installations and ships present. By June 1937, she was relieved by KMS Admiral Graf Spee, but returned to the Mediterranean until October, with captain Otto Ciliax in command.

KMS Admiral Scheer before the war

1940 Operations

In September 1939, Admiral Scheer was in Schillig roadstead (off Wilhelmshaven) with Admiral Hipperand a few days later attacked by five Bristol Blenheim bombers. The crews on high alert managed to shoot down one of these, and she was lucky with just one bomb hit, but a dud, and three near-misses, including another dud. A second group of five Blenheims arrived shortly after to be greeted by a vengeful AA and all shot down. In November 1939, Theodor Krancke took command of the ship. After a refit she was prepared for her first commerce raiding mission, in the Atlantic. Duing the early months of 1940, she was fitted with a new raked clipper bow, a lighter conning tower, modified bridge and superstructures, radar and AA, and was reclassified as “Schwere Kreuzer” (heavy cruiser). On 19–20 she was again targeted by RAF bombers but took no hits. She departed on October 1940 and slipped through the Skagerrak by night on 31 October-1st December.

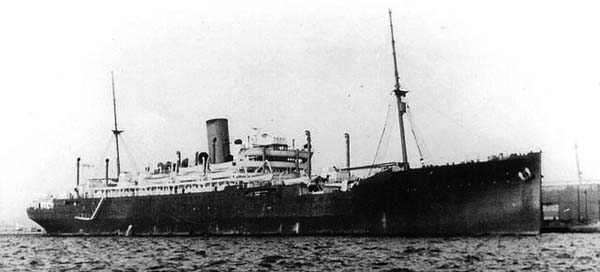

AMC HMS Jervis Bay

In the north Atlantic, Her B-Dienst radio interception system catch emissions from convoy HX 84 from Halifax. Her Arado seaplanes took off and soon located the convoy on 5 November 1940. It was protected at the time only by the armed merchant cruiser (AMC) HMS Jervis Bay, sole escort for the convoy. As soon as Scheer was spotted, the AMC issued a report and sailed towards her in an attempt to protect the convoy, latter ordered to scatter under under cover of a smoke screen. Admiral Scheer starting firing on Jarvis Bay, scroting hits, disabling her wireless radio and and steering, the bridge, killed the staff and captain Edward Fegen and the fire went on for 22 minutes until she sank. But this decision delayed any actopn on the convoy, which escaped. Nevertheless, her spotter planes localized five ships, on 37 ships that she was able to catch up and sink. On 18 December the 8,651 tons GRT refrigerator ship Duquesa was sunk, but not before she sent a distress signal. Scheer’s captain still hoped to draw British naval forces nearby, luring them while Admiral Hipper now just exited the Denmark Strait for her own mission. This was a success as soon, Scheer became the target of aircraft carriers HMS Formidable and Hermes, the cruisers Dorsetshire, Neptune, Dragon (Polish), the AMC Pretoria Castle. But Admiral Scheer eluded them while capturing the 8,038 GRT oil tanker Sandefjord on 18 January 1941, which prize crew was landed at Bordeaux. Until 7 January, she resupplied with the Nordmark and Eurofeld, and the auxiliary cruiser Thor. Until 20 January she captured three more Allied vessels for a total of 18,738 GRT and spent Christmas 1940 in the mid-Atlantic, later heading for the Indian Ocean in February 1941.

1941 Operations in the Indian Ocean

On 14 February she met the auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and both were supplied by Tannenfels, 1,000 nmi east of Madagascar, making a brief about Allied merchant traffic in the area. They separated on 17 February. Admiral Scheer steamed towards the Seychelles, north of Madagascar. She took the 6,994 GRT oil tanker British Advocate and sank the 2,456 GRT Grigorios and latter the 7,178 GRT “SS Canadian Cruiser” (which sent a distress signal) and later the 2,542 GRT Dutch steamer Rantaupandjang. Of course the last two signals were catch by the British cruiser HMS Glasgow patrolling the are. She launched her reconnaissance aircraft, spotting Admiral Scheer on 22 February. Vice Admiral Ralph Leatham, (East Indies Station) sent in reinforcement the HMS Hermes and the cruisers Capetown, Emerald, Hawkins, Shropshire, and HMAS Canberra. Captain Krancke decided to veer south-east and reached South Atlantic by 3 March 1941. Thuis drew attention on her while Atantis started her own rampage close to Australia. The hunt was abandoned on 25 February.

Admiral Scheer was able to sail north up to the Denmark Strait which she reached on 26–27 March, spotted but evading the cruisers HMS Fiji and Nigeria. She reached Bergen on 30 March, Grimstadfjord to resupply and crew’s rest. She was joined by destroyers for her trip back to Kiel, arriving on 1 April. This was not bad for a start, covering 46,000 nautical miles (85,000 km) and with a tally of 7 merchant ships for 113,223 GRT. So far she had been the best capital ship commerce raider of the war, but it was her last raiding mission. Wilhelm Meendsen-Bohlken became her captain in June 1941 and with the loss of Bismarck in May 1941, and gradual destruction of the while German supply ship network, Atlantic raiding operations were abandoned. In September, she was based in Oslo, attacked without success by a raid of No. 90 Squadron RAF, and she departed later to a less exposed Swinemünde.

Stern view, September 1941

1942 Operations in Norway

On 21 February 1942, Scheer teamed with Prinz Eugen, escorted by the destroyers Z4, Z5, Z7, Z14 and Z25 and proceeded to Norway, stopping in Grimstadfjord before making it to Trondheim. On 23 February, en route HMS Trident torpedoed Prinz Eugen, causing her to retire. Admiral Scheer participated in Operation Rösselsprung on 2 July 1942, trying to catch PQ-17, with Lützow in their own group, Tirpitz and Hipper in the other in a giant pincer. However Lützow and three destroyers ran aground and the group was dismissed while Admiral Scheer joined Tirpitz and Hipper in Altafjord, detected by the British. The convoy was scattered and left by U-boats and Luftwaffe. In August 1942 Scheer was sent to participated to Operation Wunderland, in the Kara Sea, with a destroyer escort, until Novaya Zemlya. Due to heir range, Scheer was left alone from this point. The plan called for strict radio silence and captain Meendsen-Bohlken was in full autnomy on this mission. On 16 August, Admiral Scheer met thick ice in the Kara Sea, but started searching for merchant shipping with its Arado floatplanes also spotting paths in the ice fields. On 25 August, they spotted the Soviet icebreaker Sibiryakov, which was sank after launching a distress signal. Scheer then turned south and arrived in Dikson, damaging two ships in the port, shelling the harbor facilities but renounced to send a landing party as Soviet shore batteries started firing. Meendsen-Bohlken then decided to head back to Narvik, arriving on 30 August. These were meagre results to say the least. On 23 October she teamed with Tirpitz and 5 destroyers from Bogen Bay to Trondheim and they left Tirpitz for repairs while Scheer and Z28 resumed their trip back to Germany. By the end of November, Fregattenkapitän Ernst Gruber took command and in December she was sent to Wilhelmshaven for a major overhaul. There she was damaged by an RAF attack and she was moved to Swinemünde.

Admiral Scheer in 1942

1943-45 Operations

In February 1943, Richard Rothe-Roth became her new captain, but until the end of 1944 she no longer took part in active raisding missions and instead she was versed to the Fleet Training Group operating in the Baltic. Her last commander was Ernst-Ludwig Thienemann, from April 1944. On 22 November 1944 she departed with Z22, Z35, and the 2nd Torpedo Boat Flotilla in support of the task force guarding the island of Ösel against Soviet incursions. The Soviet Air Force launched raids which were largely unsucessful. During the night of 23–24 November, the island was evacuated, and the heavy cruiser repatriated 4,694 troops with the help of the destroyers and flotilla. By February 1945, Admiral Scheer was based off Samland for possible Soviet sorties. On 9 February, they started shelling Soviet positions and until 24 February, she covered a counterattack near Peyse and Gross-Heydekrug.

Admiral Scheer in Kiel in 1945

A land connection was restored briefly to Königsberg, allwing civilian and military evacuations. However in March 1945 her guns were completely worn and she departed the eastern Baltic for Kiel, carried 800 civilian refugees and 200 wounded soldiers on board. A minefield was spotted so she had to divert to Swinemünde, disembarking her passengers and still managing to shell Soviet forces outside Kolberg until the last shell was out. She loaded then more refugees before departing Swinemünde, and her captain managed to get through minefields, and down to Kiel. She dropped anchot on 18 March and soon work started. Her aft guns were replaced at the Deutsche Werke shipyard in April and her crew was sent ashore, leaving her defenseless during the 9 April 1945 night raid by the RAF, 300 heavy bombers in all. Admiral Scheer was hit by several bombs, quickly filled and capsized. At this oint nothing was done to salvage her, the war was over. She will be partially broken up after the war, and what was left was filled with rubbled, signalled on maps and left in plane.

Admiral Scheer turned over after capziging following the 8-9 April 1945 night Kiel bombing raid.

KMS Admiral Graf Spee

KMS Graf Spee before the war

Admiral Graf Spee, perhaps the most famous of the three, but also with the shortest career, was ordered as “Ersatz Braunschweig”, replacing Braunschweig and christened by the daughter of Admiral Maximilian von Spee, completed on 6 January 1936 and commissioned the same day. She spend until early April in extensive sea trials and training, under command of Kapitän zur See (KzS) Conrad Patzig (photo), replaced in 1937 by Walter Warzecha. Officially joining the fleet she became the flagship of the German Navy and during the summer 1936, joined the Atlantic for non-intervention patrols off the Spanish coast, hed mostly by the Republicans. Until May 1937 she made three tours of duty here, and stopped on her way in Great Britain for the Spithead Coronation Review held for King George VI, on 20 May 1937.

Admiral Graf Spee, perhaps the most famous of the three, but also with the shortest career, was ordered as “Ersatz Braunschweig”, replacing Braunschweig and christened by the daughter of Admiral Maximilian von Spee, completed on 6 January 1936 and commissioned the same day. She spend until early April in extensive sea trials and training, under command of Kapitän zur See (KzS) Conrad Patzig (photo), replaced in 1937 by Walter Warzecha. Officially joining the fleet she became the flagship of the German Navy and during the summer 1936, joined the Atlantic for non-intervention patrols off the Spanish coast, hed mostly by the Republicans. Until May 1937 she made three tours of duty here, and stopped on her way in Great Britain for the Spithead Coronation Review held for King George VI, on 20 May 1937.

In between fleet manoeuver, she made a fourth and fifth and final patrol in February 1938 in the same role. That year, KzS Hans Langsdorff took command and conducted his ship in a serie of goodwill visits, inluding Tangier and Vigo. She took part to the large fleet maneuvers in German waters, the last before the war, and a fleet review held for the reintegration of the port of Memel into Germany, in honor of Admiral Miklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary. Until 17 May 1939 she made another cruise into the Atlantic, stopping in Spain and Portugal but by August 1939, she departed Wilhelmshaven to join her probable operating area in South Atlantic as war was looming.

Von Spee’s rampage in the south atlantic

The prow of admiral Graf Spee before the war

In September 1939, Graf Spee was ready to start her first commerce raiding mission, delayed until it was certain Britain would not propose any peace treaty and she was ordered to strictly adhere to prize rules. Thus, Hans Langsdorff was also firbidden to engage any warship, large or small and change positions as much as possible. On 1st September, she was resupplied by the Altmark, southwest of the Canary Islands, also transferring superfluous equipment as its boats, flammable paint, and two 2 cm AA guns installed on the tanker instead. On 11 September, her Arado floatplanes spotted the HMS Cumberland approaching. She was still supplying with Altmark, and Langsdorff ordered a quick to departure at high speed. He managed to evade the British heavy cruiser, and on 26 September, received at least the greenlight for unrestricted commerce raiding operations. Her first prize was spotted by her Arado planes: This was the Clement, off the coast of Brazil, transmitted the classic “RRR” distress signal. She was stopped and inspected, her captain and chief engineer took prisoner while her crew was sent out in lifeboats. The freighter was sunk using 30 main and secondary rounds and two torpedoes. Langsdorff ordered himself to send a distress signal to the nearby naval station in Pernambuco, making sure the crew’s rescue. The British Admiralty issued a warning to merchant shipping.

Overview of the Graf Spee as seen from its Arado floatplane

The hunt is on

On 5 October, both the British and French navies formed no less than eight groups to hunt for Admiral Graf Spee in the South Atlantic. The aicraft carriers HMS Hermes, Eagle, and Ark Royal, the French Béarn, escorted by the Renown, Dunkerque and Strasbourg and 16 cruisers were sent to locate her. Force G (Henry Harwood) sailed to the east coast of South America, with the cruisers Cumberland and Exeter, later reinforced by the Ajax and Achilles, sending Cumberland to patrol off the Falkland Islands. The other three cruisers patrolled off the River Plate in Argentina. Admiral Graf Spee meanwhile captured the steamer Newton Beech and sank later the merchant ship Ashlea, taking on board officers. On 8 October, she sank Newton Beech, at first used to store prisoners, but she was too slow to keep up. On 10 October, she captured the Huntsman. Lacking space of the prisoners, Langsdorff contacted the Altmark on the 15 for a meeting, to refuel and transfer his prisoners, added to the steamer Huntsman. Prisoners aboard Huntsman were transferred to Altmark, and she was sunk on 17 October. On the 22, Admiral Graf Spee sank the Trevanion and Langsdorff sailed to the Indian Ocean, south of Madagascar. His idea was to divert Allied warships away from the South Atlantic and by that time she already covered 30,000 nautical miles. Her engines now needed badly an overhaul. On 15 November she sank the tanker MV Africa Shell, and spotted but spared a Dutch steamer. Back to thee Atlantic on 17-26 November she met Altmark ro refuel and resupply, while her crew started to built a dummy gun turret and second funnel behind the aircraft catapult. The idea was to make a different silhouette and disrupt identity checking by the allies.

Arado 196 onboard the Scheer and Graf Spee

Her Arado floatplane later located the merchant ship Doric Star. She was stopped but able to send out a distress signal. The officers were made prisoners and crews evacuated by lifeboats, but the signalled was eagerly awaited by Commodore Harwood. he rushed his three cruisers at full speed to the mouth of the River Plate, suspecting Langsdorff to head for. On the night of 5 December, the Graf Spee sank the steamer Tairoa and a day after, met again Altmark, transferring 140 prisoners. Her last victim was the freighter Streonshalh on 7 december. On board were secret documents with maps of shipping route, and based on this, Langsdorff planned a trip off Montevideo. On 12 December her Arado 196 were lacking maintenance and could notfly. Her disguise was removed in case of a “bad encounter”, not hinder her operations.

Battle of the River Plate (13 December 1939)

KMS Graf Spee camouflage in December 1939

This famous episode started at 05:30 on the morning of 13 December 1939, when Graf Spee’s lookouts spotted masts on the horizon, at her starboard bow. Captain Langsdorff assumed thos was a convoy previously mentioned on the captured documents but as identification became finer, at 05:52 lookouts realized these were no civilian ships, and they identified warhips. Later the head vessel was recoignised to be the HMS Exeter accompanied by what was thought to be destroyers, with perspective, but revealed themselves as Leander-class cruisers. Langsdorff decided it was worth fighting due to her superior firepower, the crew’s own motivation and own possible speed with wornout engines. Battle stations was ordered, and full speed ahead to close in. At 06:08 Harwood spotted the Graf Spee and order to split gunfire of her main battery. The duel indeed opposed six 280 mm plus eight 150 mm versus eight 203 mm and sixteen 150 mm. But the German warhip had to rage advantage and opened fire first at Exeter. Her secondary battery four broadside guns were trained on Ajax at 06:17. Exeter returned fire three minutes later followed by Ajax and Achilles in a few minutes. For thirty minutes, the duel was on and Exeter was hit three times: Both forward turrets were knock out, as her bridge and her aircraft catapult. She was also crippled by shrapnell and on fire. Ajax and Achilles tried to divert attention on them by closing in so much Langsdorff thought them in position to make a torpedo attack. He decided to turn away and release a smokescreen.

Exeter was able, thanks to this manoeuver to retire but continued firing with her only operative aft turret, and deplored 61 dead and 23 wounded. Nevertheless, her captain manoeuvered as to bring her close on Graf Spee and still have her aft turret trained, but the latter spotted this and fired on Exeter again. This time Exeter was crippled and had to withdraw again, with a list to port. At 07:25, Ajax was hit, loosing her aft turrets but by then both sides broke off. Admiral Graf Spee headed to the River Plate estuary. Harwood stayed outside its range, in observation. on Admiral Graf Spee it was time for a report. Langsdorrf was informed her ship had been it around 70 times and 36 men were killed, 60 wounded including Langsdorff himself by shell splinters on the open bridge. The ship had some damage but nothing really serious, nevertheless the only wise decision was to join Montevideo for repairs ad treat wounded men.

Graf Spee entering Montevideo, battle damaged

The most urgent issue was the destroyed oil purification plant. It was problem as impacting the quality the diesel fuel for the already worn out diesels. Any long range trip was also impossible as water reserves were impacted by the destruction of the desalination plant and the galley. She had been hit in the bow too, which impacted her seaworthiness, especially if she tried to make it across the Atlantic. In addition her ammunition stocks were low. The majestic but battered warhip arriving in port and wounded crewmen were quickly taken to local hospitals, dead were buried with full military honors, and the few captive allied seamen released. Repairs were a problem, as estimated to take at least weeks. Therefore, British naval intelligence put some tricks of its sleeve, and on one hand, force the Uruguayan Governement to enforce neutrality rules, of 72h stay (Hague Convention of 1907), and in the other, that a powerful fleet was away at sea. Langsdorff weighted his options and considered an attempt to break out of the harbor, as asked by Berlin. Another option was to flee to Buenos Aires for an internment, waiting perhaps the end of its neutrality, or third, to scuttle the ship and spare his men. Being a humanist and sailor in the tradition of men such as Felix Von Luckner (Seeadler) in the last war, he choose this path.

Closer view of Graf spee’s battle damage and camouflage in Montevideo

On 17 December 1939, Langsdorff ordered to seize and destroy all important equipment, dispersing remaining ammunition and prepare explorive charges to scuttle the ship. On 18 December he sailed away with a skeleton crew on board of 40 men and moved the ship in the outer roadstead. There, the 72h delays passed in this evening, with a crowd of 20,000 watching the events unfolding. Scuttling charges were set leaving time to the crew to be loaded by the Argentine tug nearby. Explisions started at 20:55, also detonating ammunitions. This was quite a spectacle as darkness came on a bright sky. The ship slowly san to the bottom in these shallow seas and would burn for the next two days. Sadly, Langsdorff was also aware of the consequences to act against Berlin’s orders for his family and decided to shot himself in full dress uniform, lying on the ship’s battle ensign. The crew buried him with battle honors, and was later picked up by late January 1940, on the then neutral American cruiser USS Helen. Some men were able to visit the wreck of Admiral Graf Spee, and were disembark in Argentina, interned for the remainder of the war. The impressive wreck was not a threat to navigation as long as the visibility allowed it, but nevertheless it was partially broken up in 1942–1943. Later, salvage rights were purchased from the German Government via a Montevideo engineering company. Only in February 2004, her wreck was raised and gradually dismantled for good, but a commemorative plaque was left after a ceremony.

The wreck of Admiral Graf Spee off Montevideo

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign