USA (1896-99) USS Kearsarge, Kentucky

USA (1896-99) USS Kearsarge, KentuckyThe tandem turreted battleships:

WW1 US Battleships:

USS Maine | USS Texas | Indiana class | USS Iowa | Kearsage class | Illinois class | Maine class | Virginia class | Connecticut class | Mississippi class | South Carolina class | Delaware class | Florida class | Arkansas class | New York class | Nevada class | Pennsylvania class | New Mexico class | Tennessee class | Colorado class | South Dakota class | Lexington classThe Kearsarge class was certainly not the best remembered of the USN’s battleships as they played a minor part in WW1 and were scrapped afterward, but from a design standpoint, they were out an interesting out-of-the-box solution to an old problem: That of cramming firepower in a limited space, maximizing the efficiency of armor and thus, preserving some speed. The Kearsarge was one such possible solution, although it demonstrated it was all but practical. The concept was uniquely American – It did not spread in other navies but was repeated on the Virginia class battleships of 1904.

The singularity of this design was to use “tandem turrets”, a system in which a turret was simply fitted upon another. This had of course some advantages but also drawbacks, Conway’s rightfully called it “a most unfortunate arrangement”. Indeed, the ships were armed with the usual for pre-dreadnoughts: A main batter of 13-in guns (330 mm), and a secondary battery of 8-in guns. The tradition of USN capital ships until then has been the combination of 6-in, 8-in, and 13-in guns.

On the Indiana class, the 8-ins were in casemate corners barbettes. On the USS Iowa, they were in four single broadside turrets. For the Kearsarge class, something new was tried, in order to free broadside space for more artillery. The solution of stacking turrets allowed designers to place fourteen 5-in guns, faster firing than the four previous 6-ins on the Indiana class and having a much better punch than the USS Iowa’s six 4-in guns. On paper an ingenious solution by the Bureau of Ships.

Design process and development

Before going into the design, context is important: The Navy was struck by the economic depression in 1893. The new Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert, was not favorable to expensive battleship designs until he was convinced by Alfred Thayer Mahan’s Influence of Sea Power upon History like so many politicians of the time. Thus the same year he requested Congress to fund at least one new battleship, which was delayed until 1895.

This left the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) time to refine existing designs and debate over the best options. The Kearsarge was authorized by the Act of 2 March 1895. The admiralty decided to get rid of the raised forecastle and tried to find compromises for coal storage, a crucial point at that time for autonomy. Armor protection was reworked and arguably better than previous US pre-dreadnoughts, notably introducing a revised armor deck that gave more volume to the hull. At the same time, it was brought into question the effectiveness of returning to the Iowa’s main gun caliber of 12-inch (305 mm) guns instead of 13-in.

But the greater improvement was the introduction of a consistent tertiary battery of 5-inch (127 mm) quick-firing guns, which were just being developed, instead of relying only on 8-in guns and much smaller weapons. This shift up radically increased firepower. Discussions about the range and arc of fire left brought up suggestions of turning the ship into an all-turret design, but it soon proved unrealistic. Instead, classic barbettes were chosen to free space on the deck and armored walls. The limits were the increased weight of a turret arrangement and ammunition supply or fire control. The choice of a central battery amidships pushed the secondary armament of 8-in guns to the ends of the hull, therefore two-story turrets were chosen.

In general, by designing the ship, the engineering staff decided to depart from the low-freeboard Indiana class and high-freeboard USS Iowa, trying to find an in-between with a higher flush deck overall. The design incorporated many other improvements such as quick-firing guns and improved armor protection, apart from the two-story turrets.

The design eventually settled on three designs for the secondary artillery:

-“A”: Eight guns, two in centerline, superfiring, two wing turrets amidships.

-“B”: No forward turret, two wing turrets further forward, one superfiring aft.

-“C”: Centerline turrets, no wing mounts

-“D”: Reverse of “C”, wing mounts only.

In the end, C&R preferred the “A” design, maximizing firepower, but was opposed by the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) which wanted to scrap all four designs and requested a new proposal. The two-story turret. It was the concept of Joseph Strauss from BuOrd, and he proposed this solution to solve issues with the space available. The very unorthodox turret design with the second turret fixed atop the first seemed evident on paper, at the time turrets existed already for 40 years, but that solution had never been adopted. This led to a fifth version, called “E”.

The only limitation, fire-control-wise, was the obligation of the second battery to target the very same objectives as the main artillery. The idea was at almost the same range, the 8-in guns fired faster and still could engage the superstructures instead of the hull for example due to the fact they still had independent elevation. It was thought that at closer ranges, the faster 8-in could take over while the 12-in guns were reloading, thus making independent rotation unneeded.

Supply problems such as the elevator for ammunition were relegated to technicalities to be solved by engineers after the design was approved. However, it was done in the context that much better, a lighter turret design with weight savings was to be created. This was so much so that the twin-story arrangement was thought to be lighter than the two-gun turrets used on USS Iowa.

BuOrd also strongly advocated for the return of 13-in guns instead of 12-in as they were thought to be 30% more powerful. The 8-in guns still compensated for the slightly slower 13-in gun’s reload as well. The other argument was that tests performed with 15 in (381 mm) armor plates showed they could be penetrated by 13-in shells.

In the end, the Navy preferred BuOrd’s “E” design with the 13-in guns.

The design was later criticized long after the ships were in service because of its poorly-designed turrets (which engineers thought to improve on the Virginia class) and the fact that despite its slightly higher freeboard than the Indianas it still had a “wet” lower battery. But the worst point was about the development of quick-firing 12-in guns; They rendered the whole concept a failure as the new main guns fired nearly as quickly as the 8-inches. In both cases, the main guns could not be fired without severe concussion effects for the crew of the 8 inch gun and great strain on the upper mount.

Design of the Kearsarge class

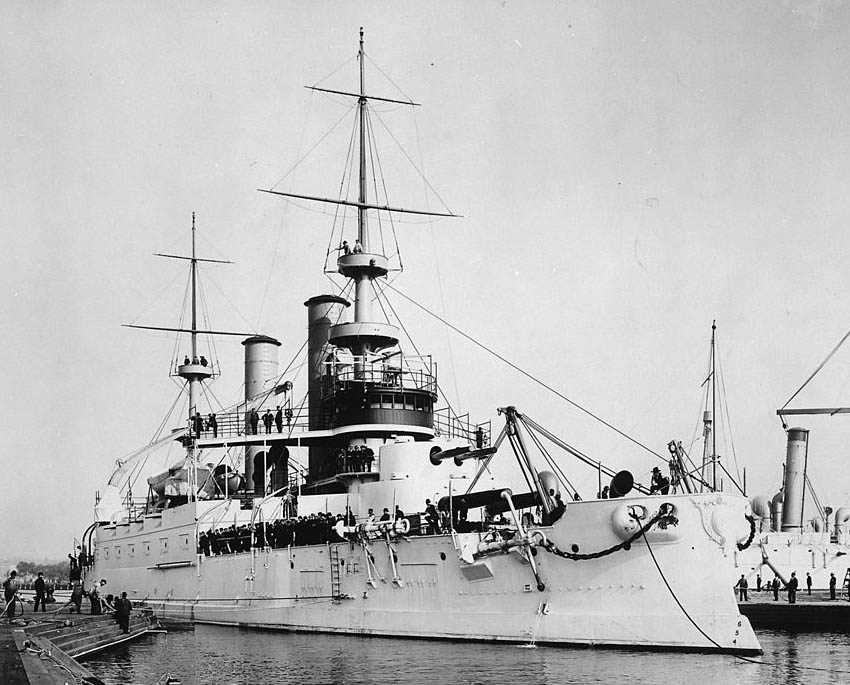

The two new battleships on paper, as authorised under the Act of 2.3.1895, were longer than the Iowa, with 368 feet (112 m) in length (waterline), 375 ft 4 in (114.4 m) overall. Their beam was 72 ft 3 in (22.02 m) and their draught 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m). Displacement reached 11,540 long tons standard, thus reaching 12,850 long tons (13,060 t) fully loaded in battle order. They shared the low freeboard of the Indiana class, 14 ft 6 in (4.42 m) forward under normal conditions, but in heavy weather, the entire deck could submerge. Also a common feature of the time, a prominent ram bow was featured.

Propulsion

The machinery room contained two 3-cylinder vertical triple-expansion steam engines. They each drove a single shaft, ended by a single screw propeller. The steam engines were fed by five coal-fired Scotch marine boilers. Exhausts were truncated and went through two funnels. These engines produced a total of 10,000 indicated horsepower (7,500 kW). Their top speed as a result was 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).

However, on sea trials, both their horsepower and speed exceeded these figures. USS Kearsarge showed 11,674 indicated horsepower for 16.8 knots, and USS Kentucky did better, at 12,179 horsepower for 16.9 knots. For range, their coal storage was made better than previous designs at 410 long tons (420 t) in peacetime and up to 1,591 long tons (1,617 t) fully load in wartime. Their cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) allowed them a 5,070 nautical miles (9,390 km; 5,830 mi) radius of operations. These were the first US battleships to make extensive use of electrical auxiliary machinery, with the total output for their dynamos being 350 kilowatts.

The Kearsarge class was steered by a single rudder and at 12 knots they needed 475 yards (434 m) to make a full turn to port, and 455 yards to starboard. Kearsarge’s crew comprised 38 officers and 548 enlisted men, with 549 on Kentucky, but in WW1 it fell down to 40 officers and 513 enlisted men.

Armament

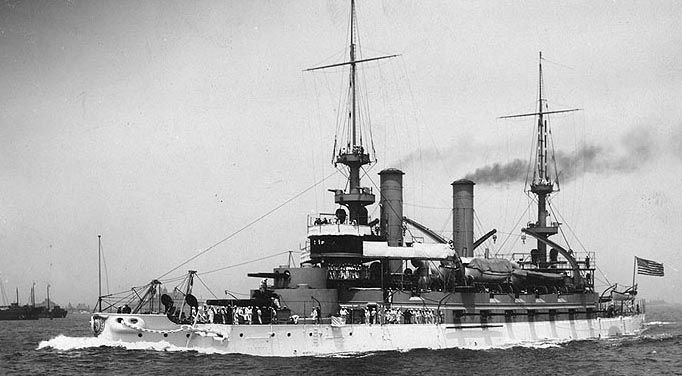

Outside the low freeboard, side battery, two funnels, and ram bow, the Kearsarge, and Kentucky’s appearance were also marked by two heavy lattice masts, carrying anti-torpedo boats light guns, and spotting tops.

Main & secondary guns: The 2-story turrets

The core of the design, dictated by the adoption of their new armament, forced the creation of these ‘double deck’ turrets with one stage housing two 13-inch (330 mm)/35 caliber guns, and on the upper turret, welded on the roof, two 8 in (203 mm)/35 caliber guns. Guns and turret armor were designed by BuOrd. But the cheese box turret was designed by C&R. They had the vertical walls of the first generation turrets and their ports were very large for sufficient elevation. William Sims participated in the design and criticized this choice as he noted that the turret floors were accessible through the ports.

A lucky hit could claim both turrets in one go. But even worse, on trials, the Kearsarge and Kentucky quickly gained the reputation of being very bad gun platforms. Not only was the blast concussion a problem for the gunners above, but when both turrets fired, heat conduction made temperatures in the upper turret soar up, whereas when the weather was rough, the top turret was leaning even more than the lower one, complicating fire direction.

Main battery – 13-in guns: They were Mark II type models, mounted in Mark III turrets, and were electrically driven. Brown powder propellant charges were used. They weighed 500 lb (230 kg) and therefore were difficult to handle and slow in their rate of fire. But they were later replaced by 180 lb (82 kg) smokeless charges. Their muzzle velocity was 2,000 ft/s (610 m/s), enough to penetrate 25 in (640 mm) of regular steel at optimal range, closer at 2,500 yd (2,300 m) in direct fire, 20 in (510 mm) of steel could be penetrated.

Their turret elevation was −5 degrees up to 15 degrees, giving them a maximal range of 12,100 yd (11,100 m) well in excess of their possible gunnery direction. Thus their fire was inaccurate at best. BuOrd recommended firing at 8,000 yd (7,300 m) instead to have any chance of scoring a hit by anything other than sheer luck. As shown in trials, even this was rather optimistic. The guns rate of fire was one shot every 320 seconds (5 minutes) with the obligation to down the guns at 2° elevation to reload them. Of course in these conditions, the faster 8-in guns were a blessing, although after the adoption of the smokeless charges, this main gun’s reload time dropped significantly.

Secondary battery – 8-inch guns: These were Mark IV artillery pieces mounted on fixed Mark IX turrets. The guns possessed a muzzle velocity of 2,080 ft/s (630 m/s). Brown-powder charges were later replaced by lighter smokeless charges, in the same early 1900s refit. Their rate of fire was originally one rpm and jumped to one every 40 sec, but reloading had to be done horizontally. The arrangement adopted for the higher rate of fire of the 8-inch guns but both the smokeless propellant adoption and a rapid-fire modification made these changes obsolete in the early 1900s.

Tertiary Battery – 5-in guns: A battery of fourteen 5 in/40 cal. artillery pieces were mounted in casemates in the upper deck. Seven per side, fourteen in all. To see the characteristics of these famous guns, which were brand new when the ships were built, see the armament section of WW1 USN battleships. Due to the low freeboard, this battery appeared in service to have been placed way too close to the waterline. As a result, in heavy weather the casemates were washed out, and firing was difficult to say the least, having to fire through waves and splashes of seawater, which also penetrated the battery.

Light battery – torpedo boat defence: This consisted of twenty 6-pounder (57 mm or 2.2 in) Hotchkiss guns, and eight 1-pounder (37 mm or 1.5 in) guns. They were all placed in individual open mounts, on elevated positions on decks and fighting tops. However, eight 57 mm guns were in a broadside battery, below the 5-inch guns, four on each side plus four more in the bow and stern casemates. Needless to say, all were useless in heavy weather. For close quarters but mostly to be mounted in boats for landing parties, two M1895 Colt–Browning machine gun 6 mm (0.24 in) Lee Navy models were also carried.

Torpedo Tubes: In the typical fashion of the time, four 18 in (457 mm) torpedo tubes were carried and placed in fixed mounts on the broadside, and above the waterline. Two abreast of the forward main battery turret, two on either side of the aft superstructure. Six torpedoes were carried as reloads. They were of the Mark II Whitehead, 140-pound (64 kg) warhead model, which covered 800 yards (730 m) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). There was just one setting.

Armor protection

These flush deck ships had a freeboard of 14ft 6in forward at legend draught, with a thick belt extending from 3ft 6in above to 4ft below the waterline and from the centre line of the after barbette to the forward end of the boiler rooms, it was 16½in thick at the top, tapering to 13¼-in at waterline level and 9½in at the lower edge. It was gradually reduced to 10½in maximum at the centre line of the fore barbette, and in the next 30ft to a uniform 4in. The important factor was the decreased belt, which left an area with weak armour, but this was compensated for to an extent with a strengthened, 5 in thick.

The bulkheads were 10in fore and 12in aft with an upper belt of 5in. The armoured deck was 24in on the flat, at the top of the heavy belt, and curved down at the ends, being locally increased to 3in forward and aft. The gun training was electric, with 13 in-turret crowns 3½in thick while the 8in ones were 2in thick. The 5in mounts on the upper deck battery had 6in armour plating. The conning tower had 10 in thick walls, and a 2-inch-thick (51 mm) roof. The 5-in casemate battery however lacked splinter screens between each gun, making it vulnerable to hits in these gaps. This was quite a shortcoming.

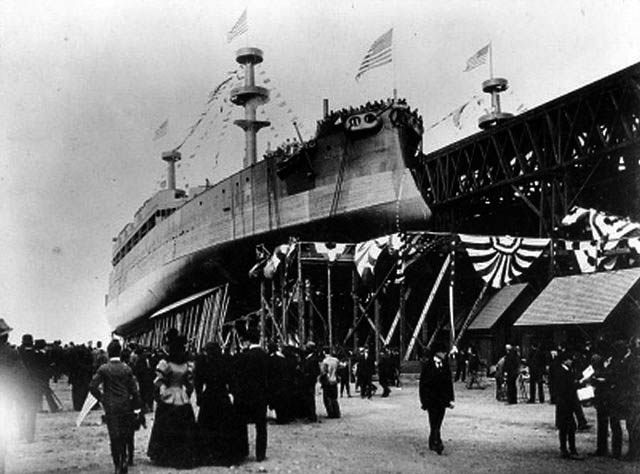

Launch of USS Kearsage, BB-5, launched in Newport News, March 1898, named after the famous 1861 sloop named for Mount Kearsarge (Merrimack County, New Hampshire) celebrated for defeating CSS Alabama in duel. A modern LHD is named after her also, and the name was to be freed for CV3 (later USS Hornet).

Modernizations

Rapid firing for main guns was introduced in the USN by 1903. USS Kearsarge and Kentucky received automated shutters in the ammunition hoists to prevent explosions in the magazines and later the electrical wiring was protected or removed entirely. This happened after a propellant charge accidentally detonated because of an electrical short in USS Kentucky in April 1906. Bulkheads between guns in each turret were also added and gas evacuators were added into breeches to expel propellant gasses.

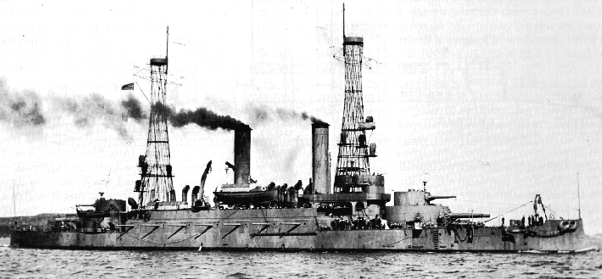

In 1909-1911, the 57 mm guns were removed, but four additional 5-inch guns were installed. The heavy military masts were replaced by the new lattice models. The torpedo tubes were removed. The boilers were replaced by eight Mosher models. The last refit happened in 1919: All but eight of 5-inch guns were removed, and recycled onboard auxiliary merchant ships to fight German U-boats in the Atlantic. Two 3 in (76 mm) AA guns were added, and at last, splinter bulkheads inside the 5-inch battery were added as protection.

The USS Kearsarge (BB-5) in service

North Atlantic Squadron’s head

USS Kearsarge started as the flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron and operated down to the Caribbean Sea. By May 1901 Captain Bowman H. McCalla took command of the battleship, followed by Captain Joseph Newton Hemphill in 1902, as the ship became the flagship of the European Squadron. She departed from Sandy Hook in June and reached Kiel, to host an official state visit by Emperor Wilhelm II and the Prince of Wales in July when back visiting the UK.

Mediterranean and the Caribbean

The battleship was later based in Bar Harbor, Maine, still as flagship, and in December sailed to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to assume control of the Guantánamo Naval Reservation. By March 1904, Captain Raymond P. Rodgers took command and after exercises in the Caribbean Sea she crossed the Atlantic to Lisbon for a state visit where she hosted King Carlos I of Portugal in June. She later reached the Mediterranean and headed east to Greece, where she assisted the Independence Day celebrations in Phaleron Bay, hosting King George I of Greece, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark, and Princess Alice of Battenberg. She went back west, halting at Corfu, Trieste, and Fiume, before returning to Newport, Rhode Island in August. USS Maine later replaced Kearsarge as the flagship of the North Atlantic Fleet. In December 1904, Captain Herbert Winslow was in command, and in April 1906, she was a victim of a grave accident off Cuba when a gunpowder charge for 13-inch guns ignited after a short, killing two officers and eight men. This led to drastic safety measures being taken during a subsequent refit.

USS Kearsage with the great white fleet

The Great White Fleet

After joining the fourth Division, Second Squadron under command of Captain Hamilton Hutchins, she departed in December 1907 with the Great White Fleet. She halted at Trinidad and Rio de Janeiro, joined the west coast of South America (Punta Arenas, Valparaíso, Callao, Magdalena Bay), and halted in May 1908 to San Francisco. Later she departed for Hawaii and joined Auckland, Sydney in Australia, and Melbourne.

A third journey took place from Albany, Western Australia, bound to the Philippine Islands, Japan, China, and Ceylon, back to the Suez Canal, Port Said, Malta, Algiers, Gibraltar, and back to Hampton Roads on 22 February. She hosted U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt on her return in celebration. The great white fleet had achieved its advertising and training cruise around the globe. Until 1914, she spent her service between the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Pacific without notable event. USS Kearsarge was modernized and therefore decommissioned for this, placed in drydock at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard on 4 September 1909. This rebuild was completed in 1911 for $675,000 USD.

USS Kearsage after refit in 1916

The great War

From her return from the dockyard in 1911 until August 1914, USS Kearsarge was in reserve. She was recommissioned on 23 June 1915, to patrol the Western Atlantic coast. She later landed US Marines at Veracruz in September 1915 and stayed there until January 1916 bringing back Marines to New Orleans. She was in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet in Philadelphia, training naval militia and Armed Guard crews, and naval engineers in the Atlantic after the US entered the war. In August 1918 she rescued survivors of the Norwegian barque Nordhav, sunk by U-117. The rest of the war ended without noticeable event. She was decommissioned in May 1920 after training in 1919 United States Naval Academy midshipmen in the Caribbean.

The Interwar

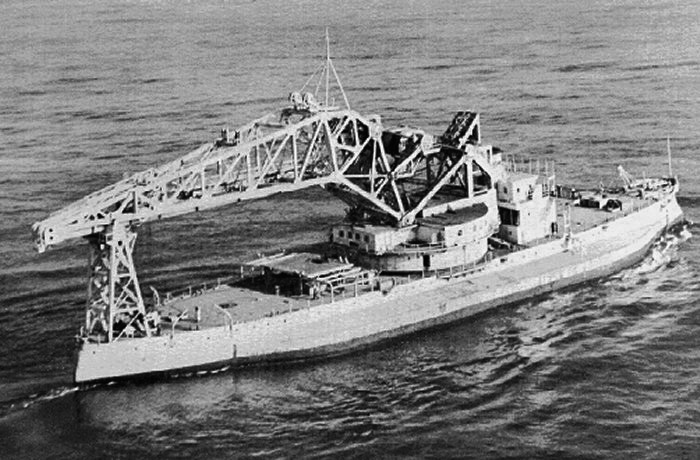

That summer it was decided to convert her into a crane ship, later denominated IX-16 on 17 July 1920 and AB-1 on 5 August. This was a radical rebuild. Kearsarge was converted into a crane ship, with all her armament and former superstructures, plus the armor removed in accordance with the Washington Treaty tonnage limitations. She was fitted with a large revolving crane with a lifting capacity of 250 tons (230 tonnes) plus 10-foot (3.0 m) blisters to improve stability during operations. She started her new career, which would span the whole interwar, and even afterward. She was found useful on many occasions, for example in 1939 when she raised the submarine USS Squalus from the bottom.

USS Kearsarge in 1920, just before conversion. She was converted to a crane ship in 1920, stability being increased by bulges and a very large 250t revolving crane fitted. She was renamed Crane Ship No 1 in by November 1941.

Word War Two

Amazingly, USS Kearsarge/AB-1 was still active when Pear Harbor happened in December 1941. On 6 November she just has been renamed again Crane Ship No. 1, to free her name for the future CV-33. She served as a heavy lifter for guns, turrets, and apparatus for the battleships and cruisers USS Indiana, Alabama, Savannah, Chicago, and Pennsylvania.

In 1945 she was transferred to the San Francisco Naval Shipyard to assist in the fitting out of USS Hornet (ii) and USS Boxer, and the rebuild of USS Saratoga. Later she assisted in the reconstruction of YD-171 on Terminal Island and three years after in 1948, she left the West Coast, at the Boston Naval Shipyard. By June 1955 at last she struck from the register and sold for scrap in August.

USS Kentucky (BB-6) career

BB-6’s first captain after commission was Captain Colby Mitchell Chester. She had been fitted out at the New York Navy Yard and her first mission was to replace USS Newark in the Eastern squadron during the Boxer Rebellion, under Rear Admiral Louis Kempff. Next, until 1904 she toured many Asian ports such as Chefoo, Wusong, Nanking, Taku Forts, Hong Kong, Xiamen, Nagasaki, Kobe, and Yokohama. She was the flagship of Rear Admiral Frank Wildes and later Robley D. Evans. In 1904 she departed Manila for NYC, going through the Suez Canal halting at Alexandria and Gibraltar on her way.

A painting of USS Kentucky at Newport News

She became part of the British North Atlantic Squadron at Annapolis in 1905 for exercises and alternated manoeuvres between there and Cuban waters. She landed Marines during the 1906 Cuban Insurrection. She attended the Jamestown Exposition at Norfolk, Virginia, in April 1907 and took part later in the Great White fleet, touring the same cities as her sister ship BB-5 in her three cruises (see above). This took over her career until 1909.

Like USS Kearsarge, she was modernized in August 1909, decommissioned at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, and emerged from the drydock in 1911, with notably new cage masts, water-tube boilers, and a revised armament. Due to her age, she was placed in the Second Reserve, and in 1913 was transferred to the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Philadelphia.

She was recommissioned on 23 June 1915 to carry Marines to Veracruz, and remained there until 2 June 1916, making a hop to New Orleans for the traditional Mardi Gras celebrations and to rest her crew. She stopped on her way back to the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and Santo Domingo and was later trained by naval militias from Maine before heading to NY naval shipyard for another refit on 2 January 1917.

When the war broke up, she resumed training recruits from Yorktown, Virginia, and eventually trained several thousand men, 15 groups of recruits in all until the end of the war. She was overhauled at the Boston NyD on 20 December 1918, and on March 1919, departed for new exercises and training, this time for the US Naval Academy midshipmen. After the Washington treaty was signed she was either to be disarmed, demilitarized, or converted for other uses as her sister was, or broken up. The latter option was chosen and she was written off on 27 May 1922, sold, and BU in March 1923.

USS Kentucky in Sydney with the great white fleet, 1906

Author’s illustration of the Kearsage in 1917

Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 114.4 x 22 x 7.16 m (375 x 72 x 23 ft) |

| Displacement | 11,540 long tons standard, 12,850 long tons FL |

| Crew | 38+549 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts TE steam engines, 5 scotch boilers 10,000 hp |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Range | 5,070nm (9,390 km; 5,830 mi) at 10 knots |

| Armament | 4 × 13 in/35, 4 × 8 in/35, 14 × 5 in/40, 20 × 6-Pdr, 8 × 1-pdr, 4 × 18 in TTs. |

| Armour (max. figures) | Belt 16.5 in, Turrets 17 in/11 in, CT 10 in, Deck 5 in. |

Sources/Read More

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1860–1905

Reilly, John C. & Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923

Albertson, Mark (2007). They’ll Have to Follow You!: The Triumph of the Great White Fleet.

Bauer, Karl Jack & Roberts, Stephen S. USN Register 1775–1990: Major Combatants

“Crane Ship No. 1 (AB 1)”. Naval Vessel Register.

Evans, Mark L.; Marcello, Paul J. “Kearsarge II (Battleship No. 5): 1896–1955

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers 1905–1970. Doubleday and Company

Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships of World War I. London: Southwater Books

US Navy, Naval History and Heritage Command (11 May 2009) USN BBs.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Seaforth Publishing

naval-encyclopedia.com/ww1/pages/us_navy/us_navy14_18.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kearsage-class_battleship

Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1860-1905 and 1906-1921.

Models corner:

The modern LHD or the civil war corvette draw more interest than the mediocre battleship it seems:

Niko Models 1/700

1/350 Iron Shipwrights model

Free 3D model on 3dcadbrowser.com

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign