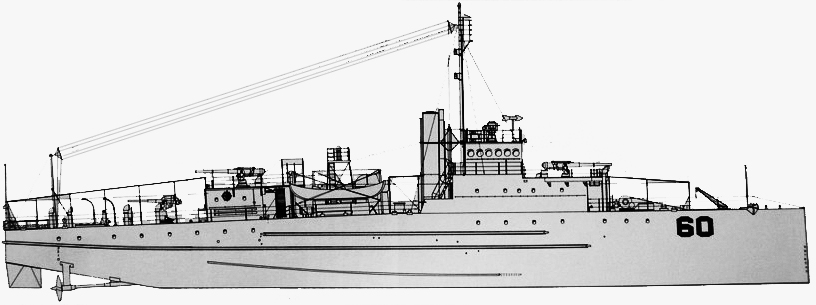

Ancestors of WW2 PC Boats: The ‘Eagle boat’ resulted from a request to Henry Ford by the US government to apply his techniques to deliver in record time a very large series of steel-hulled medium-range ASW patrol boats before the end of the war. Eagle Boats were also tailored for the USN to fill a gap between destroyers and the common sub-chaser of the time: The mass-produced wooden-built 1917 ‘110 feet’ boats. Steel-built in record time as the production facilities, tools, and methods were set up. 60 were built, though as Germany signed the armistice they never had the time to prove their value, most of them being scrapped before WW2.

Operational context

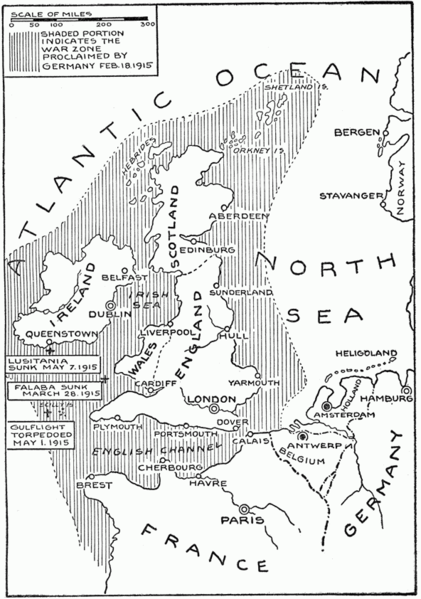

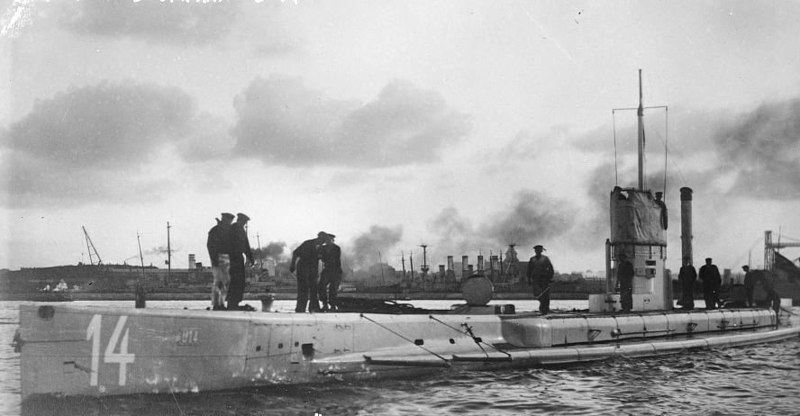

The US entered the fray in part due to the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. The American public grew cautious of a supposed German fifth column, and as knowledge about an ammunition depot that blew up in NYC, Belgian atrocities, and the secret message to the financial support of a war by Mexico on the US (The Zimmermann Telegram) grew, the US Government was pressed for an additional answer. As it was related to submarine warfare and the new “barbarian” weapon that was the submersible, president Wilson, before a joint session of Congress announced a new building program to counter this threat on April 2, 1917, though it took two more years for the prejudice to mature. However, it would take at least six months to get the country on a war footing, send troops to Europe, or mobilize naval forces. A massive naval plan was adopted, but it focused mainly on destroyers and light cruisers as well as new battleships, not small boats.

At that time the unrestricted sub-warfare targeted freighters and tankers without warning and met great success initially in 1915, though it was stopped by the Kaiser with the sinking of the Lusitania, before being resumed again in February 1917. While this decision soon unleashed USN ships in the Atlantic, at the same time the British set up plans for a massive shipbuilding programme both for ASW dedicated vessels and replacement by mass-produced trade ships for standard types. Another interesting development of the time was the quick adoption and generalization of naval camouflage.

U-Boat campaign 1915 area of operations

USN response

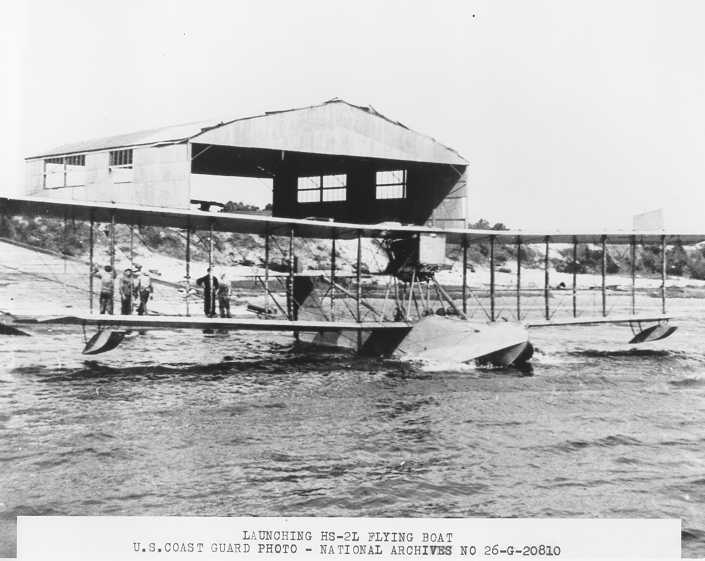

Initially, there was no contingency plan for ASW warfare. Destroyer construction on a very large scale was already in full swing and due to their range and speed, they were considered deadly for submarines, although their gun-only armament limited their effectiveness. The rapid development of air patrols was one such solution: The Aeromarine and Standard H4H floatplane series covered coastal areas, while mass-built Curtiss HS seaplanes and British-built Felixtowe series aircraft covered larger expansions.

But the admiralty was slow to devise the construction of smaller ships with the exception of a single model to be built as an emergency stopgap right after the US entered the war: Early in 1917, it was planned to cheaply mass-built ASW vessels using no strategic materials: These became the wooden Sc 110 ft series. SC stands for “Submarine Chaser” and 110 feet for their overall length. 4.5 m wide and with a 1.70 m draft they were relatively nimble but could undertake long coastal patrols in moderately rough seas. They relied on aircraft engines, three Standard petrol ones, which together produced 600 bhp for 18 knots.

This was sufficient to catch a surfaced submarine and more than sufficient to trail a submerged one for hours. The only limitation was the range, that being 1000 nm, at 2 knots. Elco was responsible for their production, chosen for their experience in mass-producing 80-foot launches for the Royal Navy. Wood allowed them to be built in very large numbers in a short time and when signing the contract the US government hoped to have 345 boats ready for the 1st January 1918. They also planned to send them to France, with two orders of 50. Despite the schedule never being met, the SC boats were considered a triumph of war mobilization, as 441 were delivered (out of 448 planned) until November 1918.

They were designed by Loring Swasey who would also design sub chasers in the Second World War. They were armed with a standard 3-in gun, 2 machine guns, and a Y-gun, but were criticized by the Admiralty for their short range and small size, hampering their service in the North Atlantic and the North Sea when deployed from European ports. These criticisms were heard by the government which searched for a new, much larger, and steel-hulled design, which turned out to be the Eagle Boats.

Development of the Eagle Boats

The genesis of the Eagle Boats was very much the result of the visible disappointment with the SC 110 foot boat. Although their manageable size and wooden construction allowed them to be cheap and quickly delivered from anywhere, the Admiralty wanted a long-range, sturdier, and seaworthy vessel that could patrol the entire Atlantic, more in line with British ships such as their “Flower” class sloops.

For their construction, it was necessary to eliminate shipbuilders already engaged in delivering destroyers, larger warships, as well as merchant shipping. This time, the Bureau of Construction and Repair was put in charge of the design and made one that was sufficiently simplified to allow a very quick construction by inexperienced shipyards, though the design also had the modularity to allow a final assembly rather than the whole design being built in the same area. Tailorization as a construction method was already envisioned and there was immediately a name that came to mind from the government: Henry Ford.

Construction by Ford (short video archive)

Ford’s methods applied on ships:

Ford was contacted, given the blueprint from B&C, and put his engineers to work. He came back with a plan which as expected, was revolutionary. He was to create a brand new plant on the River Rouge, on the outskirts of Detroit, not far away from his support base and personal, and with access to the Great Lakes. There, he proposed to create them as products the same way he used for his Ford T, using his mass production techniques but on a much larger level, and employing the same factory workers.

When completed, the ships would be conveyed through the Great Lakes via the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic coast to reach a port or arsenal, complete fitting out, and be commissioned. Ford personally however took little part in their design as ships were not his center of interest, but he insisted upon even more simplifications in design, and the use of steam turbines rather than diesel as specified by C&R bureau. Ford’s engineers started with known bases due to their lack of experience with ships: The British P-Boats from 1915 and another alternative study for an over-simplified and shortened destroyer design, an austere version of the Flush-Deck destroyers proposed in 1917.

Eagle boat 35 & 58

At first, Ford engineers created a full-scale model at the company’s Highland Park facility. This mock-up gave the team and Naval officers who came to the location time to refine the design and correct flaws from the initial blueprint. During these reunions, they decided on the placement of rivet holes and many other details. In the end, this also helped the dispatched production experts to compose specifications for the future plant and refined the processes before the plant was even completed (as the walls and floor were erected).

These were sound decisions to ensure the ships were to be quickly built when the plant was completed, however, the whole process took precious months to set up. Eventually the blueprints of what could have been called the “SC 200 ft” were approved and in 1918 and the Bureaux hoped that 100 could be delivered by the end of the year. This proved to be optimistic.

Design of Eagle Boats

Design development

As in other such programmes, the issue was to what extent the destroyer-substitute should approach destroyer performance. The General Board wanted a sustained sea speed of 19 knots and depth charges. The original bureau proposal of December 1917 envisaged a maximum speed of 18kts, a cruising speed of 10kts, and a battery of 1-3in/50 and 1-3in/50 AA gun. For a time the design also included a twin 21-in TT, as in P-boat practice, but a gun replaced it in the final design.

In January 1918, the Board reluctantly approved this more austere design, recommending the immediate construction of 100 boats. It went on record that “as in the case of the 110ft chaser it regards the 200ft boat (…) as an emergency design and not one which should be adopted if time and the submarine situation were not of such seriousness.”

In July 1918 the bureaus suggested a 250ft, 650t patrol boat capable of 25kts, and armed with 2-4in, 1-3in AA, a twin 21in, and a Y-gun, The General Board wanted 5-in guns instead to meet the new 5.9 in reported on the latest U-Boats and was willing to sacrifice the TTs as well as a reduction to 22 knots, by pairing two turbines instead of just one. There was a turbine plant also constructed at the same time as the Eagle Boat’s main plant. The board wanted also a radius of action of 4000 nm at 10 knots. To meet schedules, the Board even backed away from other programmes for fear it was to slow down the Eagle Boat programme. The 22 knots prototype ended up being built as a prototype but state secretary Daniels then squashed the programme and nothing came of it.

Hull and general characteristics

These two waves of design simplifications for mass production proved even more extreme than on the Flush-Deck destroyers. It was probably even too extreme for a military vessel, to the point of hampering its effectiveness. In the end, they missed the war entirely, being relegated to peacetime routine patrols at home, where their numerous limitations, acceptable in times of war, were no longer in peacetime, leaving them as unliked and neglected ships.

The ship’s most striking feature was its slab-side hull to simplify the construction process. By eliminating the complex curves of the bow, the ship had straight sides all along, which created a pear-shaped deck to keep some seaworthiness and fluid lines. The hull itself was made of large separated blocks with straight lines. Each rib section was made of six flat, holed sections to save weight, bolted together like lego. The hull plates were then welded together to this structure and the connection between the bottom and sides were the only rounded plates of the ship.

As completed they displaced 615 long tons (625 t) for a length of 200.8 ft (61.2 m) a beam of 33.1 ft (10.1 m) and a draft of 8.5 ft (2.6 m). They were effectively substitutes for the more expensive destroyers. The larger, austere version of the existing flush-deck series proposed in 1917 came close to production as the DD 181 class. They would have been early USN escort destroyers. Overall, the destroyers were clearly much more capable and had construction priority. The 200-footer had to be designed for minimum interference with other programmes, to be built on the Great Lakes and Inland Rivers, with everything tailored for easy assembly, few curves, and a flat sheer.

Powerplant

Plans changed over time. There was one proposal for traditional VTEs which was quickly dropped, as they were slow to heat up and not that economical for long patrols. Diesel engines were soon the best choice for C & R. Ford however preferred steam turbines, which was his main contribution to the evolution of the design. In the end, they were indeed given the low-power, relatively cheap Poole geared steam turbines, rated for 2,500 shp (1,864 kW). The single turbine was connected to a single three-bladed propeller shaft for a top speed on paper of 18.32 knots (33.93 km/h; 21.08 mph). Steam came from two mixed-fired Bureau Express boilers, with 105 tonnes of coal and 45 tonnes of oil carried, the latter injected to speed up the combustion. The boat’s total range, a crucial point, was 3500 nautical miles at 10 knots.

Armament

The final armament of the Eagle Boats as approved comprised two 4″/50 caliber guns (102 mm) installed on the forward upper deck, roof of the quarterdeck room aft, and one 3″/50 caliber gun (76 mm) on the after deck. In addition, two .50 caliber(12.7 mm) Browning M2HB machine guns were also added in mounts. They were intended to deal with aviation but could be used in a duel with surfaced U-Boats as well.

The proper ASW weapon on board was, of course, the single Y gun installed. However, this was only done on the Eagle 4, 5, 6, and 7. Indeed, there were no DCR (Depth Charges Racks) at the stern but instead, a projector initially created by Thornycroft, able to throw a charge at 40 yds (37 m). The first was installed in July 1917 and tested the next month with success. 351 British torpedo boat destroyers were modernized with this gun, taking part in ASW operations throughout the war while around 100 lighter craft also were equipped with it.

The name “Y-guns” referred to their basic shape, which was studied by U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance from the Thornycroft model which was passed to them. It was produced and became available in 1918. It held two depth charges cradled on shuttles inserted into each arm, like the 1942 DCT (K-Gun). Each charge flew starboard and port, fired by an explosive propellant in the vertical column of the Y-gun, with the USN model reaching a range of 45 yards. The New London Ship and Engine Company started producing them on 24 November 1917 but they were in short supply, which explains why only four were installed on the Eagle boats.

7 minutes footage of Ford’s Eagle Boats – National Archives Video Collection

Construction and service

Construction process and issues

The assembly plant of River Rouge was completed in five months. The first keel was laid in May 1918. Machinery and fittings mostly came from the already existing Highland Park plant, while the new River Rouge plant was given the steel sheets and parts fabricated in the A-Building. Ford believed it was initially possible to replicate the process chain used for his automobiles. However, the size of these ships made it impossible. Instead, a “step-by-step” chain was created with a 1,700-foot (520 m) line, supplied on its way by seven separate assembly areas. The line ended in the 200-foot (61 m) extension called B-Building, for pre-assembly.

Shipbuilding was all new for Ford, who was happier with mass-producing trucks for the Army. The Eagles as the result suffered from teething problems: The electric arc welding previously used on cars did not work as expected and the general workmanship of the boats was poor. This was later reduced drastically by the superintending constructor, reducing the role of the welding tool to watertight and oiltight bulkheads. Ladders were used instead of scaffolds during the bolting of plates, along with the issue that the supply of short-handled wrenches prevented workers from using the right amount of force to tightly bond the plates (which caused future leaks). Metal shavings between plates also made this bonding rather difficult and thus sealing the hull proved extremely difficult.

Delivery

USS Eagle Boat No.1 was soon renamed PE-1 in 1920. She was launched on 11 July 1918 but commissioned in October 1918. On month later the war ended. After the construction phase, the launch and fitting-out phase proved difficult: The massive 200-foot hulls were moved slowly from the assembly line on specially made tractor-drawn flatcars, then placed on a 225-foot (69 m) steel trestle. The latter was installed alongside the water’s edge and could be sunk 20 feet (6.1 m) deep using hydraulic power. Warship-grade fitting out included turbines, weaponry, wiring, and equipment to be done after launch, but there was no room available and the ships were to be stockpiled somewhere else.

The contract between Ford and the Navy signed on the 1st of March 1918 stated that one ship was to be ready by mid-July, then ten by mid-August, and twenty by mid-September, before becoming twenty-five each monthly, culminating in one per day. These figures were never met: The first seven were still not completed by the end of 1918, with only the lead boat being seaworthy. The Navy refused them, as they discovered crudely made ships plagued by leaky fuel oil compartments and disjointed hull plates. Meanwhile, the Ford plant workforce reached 4,380 by July and 8,000 by the end of the war. Ford’s initial optimism over using inexperienced labor was driven by his idea of hiring supervision personnel specialized in shipbuilding, but they proved hard to find. Needless to say on November 1918, the contract, which ranged from 100 to 112, was curtailed to just 60. PE-1 to PE-7 were commissioned in 1918, while the remaining 53 were commissioned in 1919, but by this time were no longer needed and proved to be less useful than destroyers. The name “PE” could be “patrol escort”, but the unofficial name which stuck for historians and amateurs alike was “Eagle Boat”. This came from a wartime Washington Post editorial calling in 1917 after the US entered for “…an eagle to scour the seas and pounce upon and destroy every German submarine.”

This became a postwar “Eagle Boat affair” with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts in December 1918 ordering Congressional hearings into the failure of the program. He targeted Navy officials who dismissed charges of taxpayer unnecessary, because as the boats were delivered after the end of the war, Lodge argued they were not a needed project. The officials argued the boats were a necessary experiment, as the first dedicated long-range ASW vessels in the USN, and also that Ford’s profits were modest. The case was closed as the ships found some utility in the interwar and were cheap enough to have not been a complete waste. Historian David Hounshell later wrote about the case and argued that they proved that transferring an industrial process in completely different fields was not something that could be taken lightly and would be difficult to do in an emergency.

Eagle Boats in the interwar

In the first series PE 1-PE 112, twelve boats, (PE 25, 45, 65, 75, 85, 95, 105, and 112) were to be transferred to Italy. The last boat was commissioned into the USN on 27 October 1919 despite the series as a whole being officially cancelled in November of 1918. Eagle 16, 20-22, and 30 were transferred to the Coast Guard late in 1919. The rest at first served as intended, testing their concept. Reports on their performance at sea were mixed: The use of flanged plates instead of rolled plates (an idea of Ford’s) facilitated production but resulted in poor sea-keeping characteristics, which added to never-ending leakages problems that plagued the ships.

These issues became so bad that the most crippled boats were ordered to stay in harbour, and were used as stationary aircraft tenders. Some served to support photographic reconnaissance planes used at Midway in 1920 and Hawaii the next year until larger and better-suited ships replaced them. Eagle boat 34 served a part of the year with the tug USS Koka and was used to capture elephant seals on Guadalupe Island for a Zoo. However, slowly but surely the Navy started to get rid of them, starting in the 1930s. This started in June 1930 with the scrapping of a large group of boats, 1932 a single ship, and the remainder of the boats in 1938. However, some ships never made it to the breakers and were lost at sea: PE25, Capsized in the Delaware Bay in a squall on 11 June 1920, P10 was destroyed on 19 August 1937, PE17 wrecked off Long Island, New York 22 May 1922, with PE 6, 7, 14 and 40 being sunk as targets in 1934.

Eagle Boats in WW2

A single ship was stationed in Miami as a training vessel until WW2 and in total, eight Eagle boats served during the war. The most famous of these was USS Eagle 56. She saw action during the whole war and was sunk by a German submarine near Portland (Maine) in April 1945, a unique end for a ship that missed WW1 but managed to hunt submarines throughout the entirety of WW2 before being sunk shortly before German capitulation. During the war, USS Eagle 56 patrolled off the Delaware Capes in January 1942 and went on to serve continuously despite her defects during what German submariners called the “Second Happy Time”. The east coast of North America was by then an open range for U-Boats which massacred American shipping. The crew endured months at sea without going on shore, and each time they expended their depth charges a small ship came from Cape May in New Jersey to bring her supplies, including more ammo, food, and water. USS Eagle 56 notably rescued survivors of SS Jacob Jones off Cape May in February 1942. She collided with the wreck of Gypsum Prince during another rescue on Delaware Bay. She was repaired by scrapping another Eagle boat. She was then used at the Key West sonar school in May 1942 and was later assigned to the Naval Air Station Brunswick on 28 June 1944.

At noon, on 23 April 1945, while partaking in exercises off the coast of Maine, she was hit by a torpedo, exploded amidships, and broke in two, sinking 3 mi (4.8 km) off Cape Elizabeth (Maine). USS Selfridge was 30 minutes away and came to rescue 13 survivors (from a crew of 62). The sonar operator of USS Selfridge then obtained a sharp, well-defined sonar contact. Once she got the survivors on board, she dropped nine depth charges, with no result. A postwar record stated U-853 was to be the ghost submarine, confirmed by five of the 13 survivors, with some even spotting a red and yellow emblem on the sub’s sail, an insignia that matched U-853’s red horse on a yellow shield. Despite the evidence of a U-boat attack, the Navy inquiry concluded that her loss was due to a boiler explosion. This was rectified by historians long after and nowadays, USS PE-56 is the sole WW1-era USN sub-chaser sunk by a U-Boat during WW2. None of the other Eagle Boats were ever lost to enemy action, and after 1942 they were likely replaced once escort destroyers and PC-boats were in sufficient numbers.

If there was merit to the whole series of Eagle Boats, it was to show “how not to do it” for mass-producing sub-chasers in wartime. The wooden SC 110 ft had none of these problems and served for much longer despite their simpler wooden hull, due to the industrial difficulties facing the Eagle Boats. In the end, the Navy got poor ships of little utility and a bad reputation, all of which failed in their main objective: hunting German submarines. However, there was a bright side to this hard-learned lesson. A new ship designed during WW2 drew all the lessons in this and would prove to be very successful: The PC boat also called 173 ft submarine chasers.

Read More/Src

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1973/june/eagle-boats-world-war-i

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Eagle_Boat_56

http://www.steelnavy.com/ISWEagleBoat.htm

Anti-Submarine Warfare in World War I: British Naval Aviation and the Defeat – By John Abbatiello

Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of WW1 – Norman Friedman

By Norman Friedman

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign