HMS N°1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1900-1921)

HMS N°1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1900-1921)WW1 British Submersibles:

Nordenfelt Class | Holland Class | A class | B class | C class | D class | E class | F class | G class | G class | H class | J class | K class | HMS Swordfish | HMS Nautilus | L Class | M class | R class | S classV class | W classThe start of the British sub. lineage

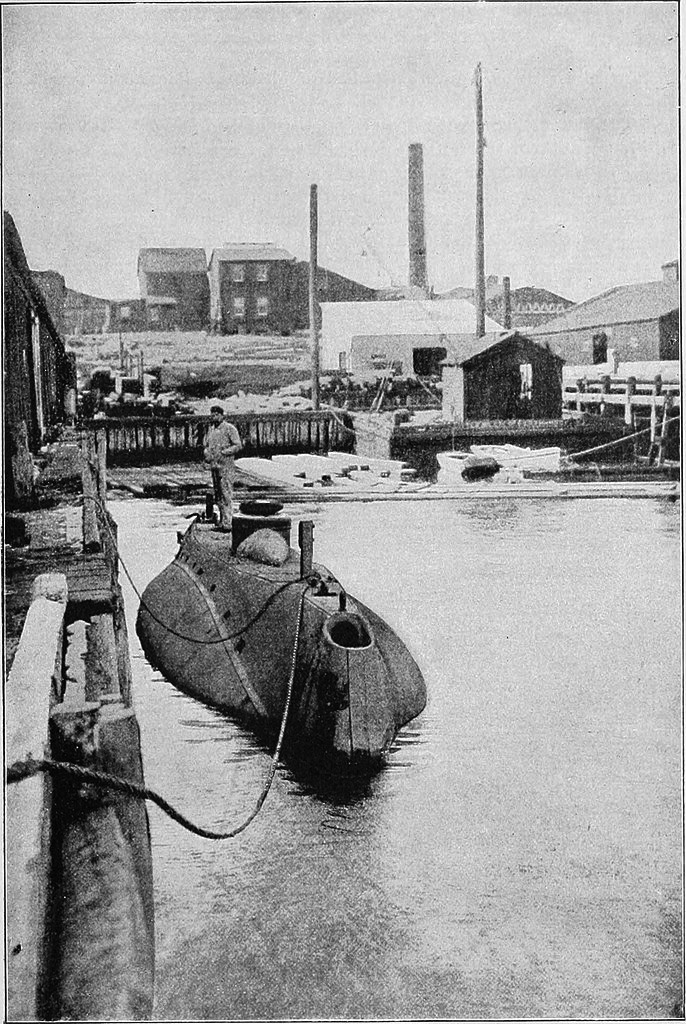

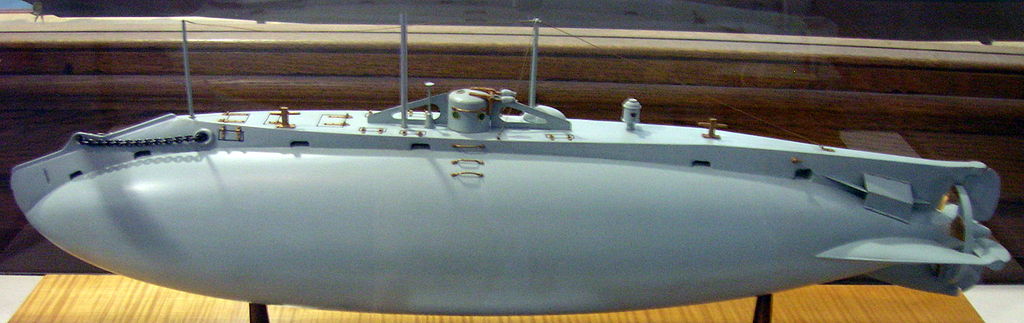

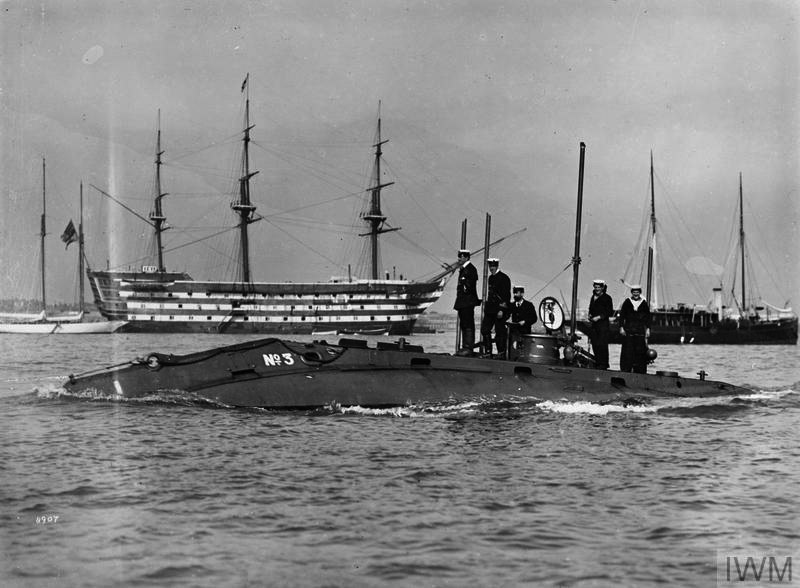

HMS N°1 on sea trials.

Initial Resistance

The Royal Navy long resisted the idea of having submarines (submersibles would be more exact) in its ranks, ajthopugh the type gained traction already before the US Civil war and especially in Europe in the 1870-80s. France in particular, betting on the young school concept of asymetric warfare, largely invested as submersibles as complement of is expansive torpedo boats fleet, and worked on many prototypes and first series already in the 1890s. The US was not far behind with already renowned manufacturers such as Irish-born engineer J.P. Holland.

The move towards submersibles was not an easy one. There was quite some resistance from the admiralty to this new “dishonorable and ungentlemanly” form of warfare, or basically a sneaky weapon only good for inferior navies. In the 1890s that position was near-impossible to move and indeed, as a weapon of war, the submersible was still not impressive, slow and dangerous, carrying a single spar torpedo or “dynamite gun” as on the USS Holland. In its early infancy with no series in adoption in any navy yet, its future was all but uncertain as some called it a “fad”, like the torpedo rams and torpedo cruisers.

USS Holland

Initial Forays

Captain Henry Jackson was a British naval attaché in Paris, reporting on French submarine developments in the 1890s. In 1898 he witnessed trials of “Goubet” a small 11-ton submersible designed to be carried aboard any large warship. In January 1899, he informed the Admiralty of exercises made by the much lager (270-ton= experimental Gustave Zédé. And its success when torpedoing the battleship Magenta. The Board of Admiralty however dismissed the idea France had ordered 12 submarines based on technical issues and political propaganda in France.

In January 1900 however, Washington DC attaché Captain Charles Ottley reported on his side on Holland’s progresses and the real interest showed by the US government to purchase one. Soon he also sent a complete set of specifications and trial performances figured to the admiralty, even a a set of blueprints.

In February 1899, new came from Paris, that Gustave Zédé was mre successful that anticipated and that a class was on its way. Meanwhile, Admiral Fisher (see later) at the head of the Mediterranean Fleet and concerned that the French might have some of these subs, asked the Admiralty defensive instructions, himself suggesting mines. In May 1899, the Admiralty asked the torpedo school to investigate on the question while requesting a submarine to provide a basis for these experiments. The same month news from the US confirmed the US purchase. Thus Sea Lord Walter Kerr and Controller Rear Admiral Arthur K. Wilson confirmed the need of purchasing one of these to investigate its capabilities, to better combat it in the Mediterranean.

Enters Sir John A. Fisher

Before being a first sea lord (appointed First Sea Lord in 1904), John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher, was already in influencial figure in the naval staff. A 1856 cadet in the “wooden fleet”, narrowly missing the Crimean war, with mentors that knew and worked with veterans of Trafalgar, he soon became aware of rapid technological developments, new powerplants with VTE, new casting techniques and the birth of ironclads, pivot breech-loading rifled cannons and central batteries as well as the first turrets, and the birth of the torpedo in the late 1870s. This coincided with the rise of the “Jeune Ecole” in France, which saw the 2nd largest fleet sinking to the 4th rank in 1910, betting everything on new development. Fisher looked at it with great attention in the 1880s and started to sense a possible counter to the absolute dominance of the RN, established as twice as powerful of the next two fleets combined.

In 1891-92, Fisher was Admiral Superintendent of the dockyard at Portsmouth, fighting inertia, accelerate shipyards output, and fight bureaucratic bottlenecks. When Third Naval Lord and Controller of the Navy, she pushed forward for the adoption of the first torpedo-boats units in the navy, and soon the first destroyers. But it’s really as First Sea Lord he drove forward the construction of HMS Dreadnought, and accelerate submarines development with the “A” class. In order to accelerate things, rather than going through the pain of many prototypes, adopting the Holland design, which had an excellent reputation at the time, as paradox since the admiralty suspected the Irish inventor’s proposal was a way to combat the British in the first place, and support the nationalist cause.

A Few works about John Holland

John Philip Holland was born in Ireland in 1841. He emigrated to America to create his first successful submarine, since Ireland lacked suitable facilities for this (clandestine at that), but it was still paid for by Irish nationalists, seeking Ireland’s liberation from Britain. His first experimental submarine was a succes which impressed everyone. He convinced his backers to pay for a bigger vessel launched in 1878, named the “Fenian Ram” (another irish reference).

John Philip Holland was born in Ireland in 1841. He emigrated to America to create his first successful submarine, since Ireland lacked suitable facilities for this (clandestine at that), but it was still paid for by Irish nationalists, seeking Ireland’s liberation from Britain. His first experimental submarine was a succes which impressed everyone. He convinced his backers to pay for a bigger vessel launched in 1878, named the “Fenian Ram” (another irish reference).

In 1900, after decades of struggle and disappointment, the US Navy accepted Holland’s Type 6 design. One US newspaper described as “Uncle Sam’s Devil of the Deep”. The Holland Type 6 was the culmination of decades of research and design. The father of submarine in the US would soon turned out to be also the father of British Submarines, quite an irony. But this still was a bold move from the British Admiralty, with probably some arms torned off in the process. It’s only on October 12th, 1900, That US Navy commissioned it first official submarine, USS Holland (SS-1). It should be said that due to the soon established British-Japanese alliance, the IJN will soon have its own Holland type in 1905.

The Vickers-Holland Agreements

The Admiralty naturally started negotiating with Holland’s Torpedo Boat Co., with Vickers Ltd as trusted manufacturer. It was agreed that The Electric Boat Co. which was granted the patents rights from Holland, would license Vickers for a local construction rather than just assemble boats shipps from the US. An order was placed for five. The Board of Admiralty on its trajectory even considered using them on offensive role if trials of defensive purposes were successful, and even to place further orders.

The general election of November 1900 saw the Earl of Selborne as new first sea lord, and new Parliamentary Secretary Hugh Oakley Arnold-Forster, which previously criticized Goschen for his resistance towards submarines, now informed of the secret development, but also worried about the advancement compared to the French. Contract was at last signed by December 1900, for a delivery in October 1901. Arnold-Forster also wanted to involve other companies but this was opposed Vice Admiral Archibald Douglass and Wilson, still unwilling to encourage such developments and give other navies encouragement this was the way forward (since the RN would lead the way).

Wilson considered that by range, the new class would only be able to operate in French waters, and the contrary was also true and French subs could well threat home ports. He saw potential to prevent maritime trade and that it was more advisable to slow down submarine development and rather focus in ant-submarine defence. This was the general state of mind before Fisher came in turn as first sea lord in 1904. However the admiralty was baffle to see the secret construction of a submarine was leaked by a Glasgow newspaper in February 1900.

The Admiralty had to acknowlede it officially in March but Arnold-Forster continued to press for more submarines, always opposed by the Sea Lords. His plans were to order three per yearas a minimum to maintain Vicker’s expertis and involvment in developing this specialization. Again from Paris came news and data showing he French design was technically superior to the Holland boats but there was no alternative to the type chosen.

A secret start

The threat posed by foreign submersibles was recoignised in 1900 at last and eventually led to the secret commissioning of a first submarine from Holland Company. The dock hoising it was labeled as “yacht shed” and there was to be no launching ceremony when HMS Holland 1 was completed in 1901. John Holland provided not only a chief engineer to Vickers but also a team of experienced submariners to train Royal Navy personnel. The first feedback was not encouraging: The British crew dislike the cramped contraption for its complicated operation.

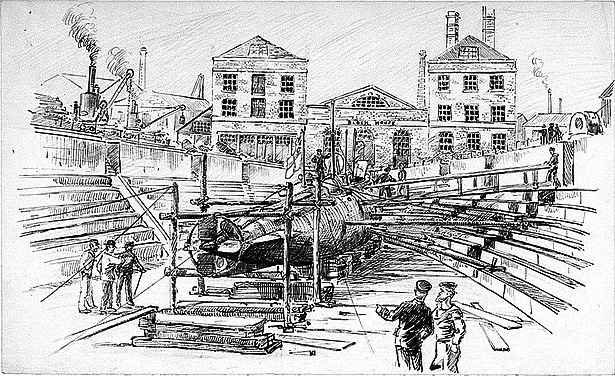

When decision was made to continue serie through the same licence from Electric Boats Co., manufacturer for the USN, the Licence was negociated for a first boat, but was soon extended for four more, and eventually went with brand new facilities created at Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness. They were simply denominated the “Holland” serie. Secret no longer applied since March 1900, and completion proceeded much faster. Holland HMS N°1 or “Holland 1” was launched on 2 October 1901.

The five Hollands built only saw training in home waters. Their all-important task was to train future British submariners. The contract included support from the Electric Boat Co. (which sent a chief engineer at Vickers as adviser and later send USN personal already working on USS Holland and the following). Initially a sixth one was to be built but so considerably altered it became the HMS A-1, first of the A class and really the start of a proper British submersible design lineage.

Hollands’s designs were famous to be fast and deep diving, with excellent agility underwater due to their electrical propulsion, but suffered of being relatively complicated and having poor range and surface speed. In short they were good “submarines” and poor “submersibles”. Perhaps not the best start. It should be said however that the British already had a potential model to be improved, dating back the 1880s: The Nordenfelt type. Although its prime creator was the namesake Swedish industrialist, it’s designer was Manchester Parish’s Reverend George Garrett. The thing worked on coal and steam and was nothing more than a reactualisation of the Confederate “David” of civil war fame. It was sold to both Greece and Turkey through the shady work of arms dealer Basil Zaharoff. However Holland’s boat was clearly a brand new league forward, combining gasoline-electric propulsion, a conning tower, ballast and trim tanks, and dynamite gun rather than a spar torpedo. Clearly the forerunner of modern submarines.

Construction and further developments

Construction however for such small vessels, despite secret was lifted, still took longer than anticipated. The first boat ready to dive was on 6 April 1902. The actual design, from engineer Fulton, was an untested, but improved version of the original Holland design. The main difference was its use od a 180 hp petrol engine. A “Captain of Submarines” was created anew to oversee development work, Reginald Bacon being appointed in this role by May 1901.

He was engineer-minded and quite experienced already with torpedo boats. He soon signalled that the Holland models were likely inferior to current French designs and unable to operate on the surface but in rare, perfectly calm sea conditions. He also criticized their limitation to just 20 miles (32 km) underwater. Finally he suggested that the boats 4 and 5, not yet started, should be revised to improve their seaworthiness. The Admiralty feared Holland would retired it’s “warranty” and thus only authorized the sixth boat to be of a brand new design, the A1, first of the “A-class” and official start of British submarine design.

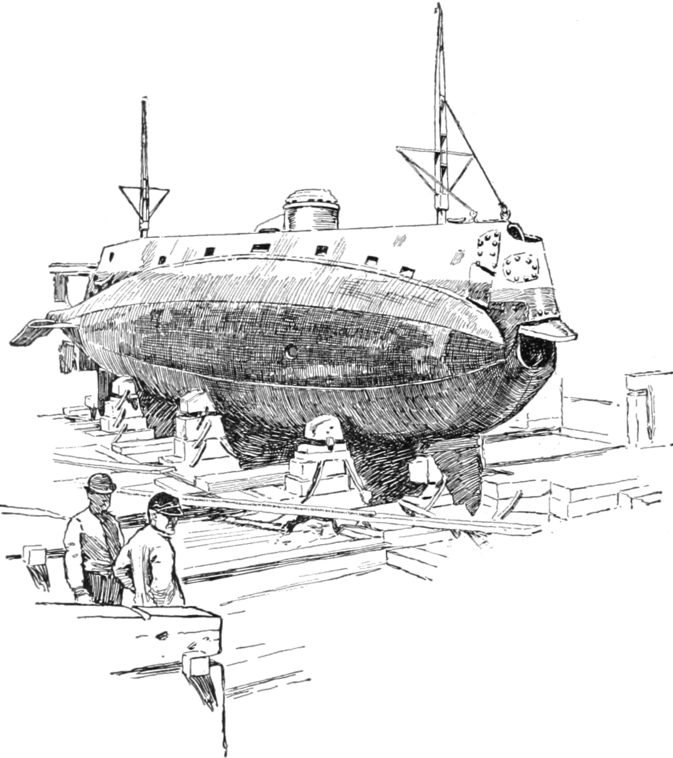

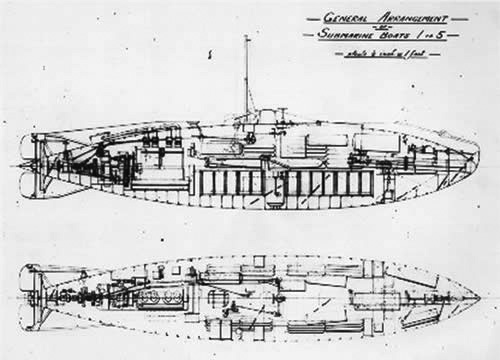

Design of the British Holland Type

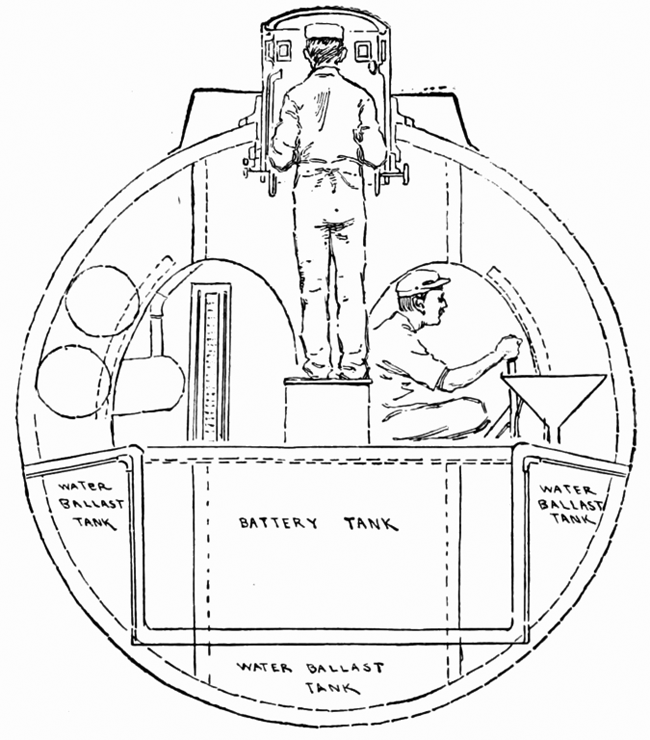

The single-hull was built from “s” grade steel which had been only used previously for the Forth Bridge. She displaced 110 long tons (112 t) surfaced and 123 long tons (125 t) submerged, so with limited ballast. The hull was 63 ft 10 in (19.46 m) long for a beam of 11 ft 9 in (3.58 m). The hull was well profiled according to the design of the time, of cyclindircal section and gradual beam up to amidships. It was however with with an inverted prow fitted with a hook eye, and a deck prolongated to a spine over the upper rudder. This was a “X” type system with four rudders enabling axcellent agility underwater, but no trim vane.

The only protruding element of the bridge was a conning tower, just large enough for a man, reinforced by spinal frames in case of collisions, and dotted with four portholes, the only internal light source in case electric lighting failed.

Vickers, Sons and Maxim in Barrow-in-Furness did not modified one bit of the original design; Except she was equipped with one of the first periscopes in the world a that times, of British design, using a ball socket joint on the hull for raise and lowering it. Her pressure hull contained the fuel tanks, ballast and internal equipments but there was no compartimentation nor bulkhead. Due to this particulars, she was limited to a maximum depth of just 100 feet (30 m). This was however well enough to completely disappear underwater, so out of view. There was no aviation at the time, and ballooning war rare, so no way to detect her but from a spotting top of a war vessel, at the time about 40 m (131 ft) above the waterline, at best. The crew was limited to eight men. Four were dedicated to manage the ballasts and pumps, one the diving controls and rudder, two the single torpedo tube and it’s reload. The only officer aboard had such an inferior rank that a Lieutenant could command a whole flotilla at least on paper. There were not so many candidates for this contraption at the time. Officers and sailors in the RN had an innate distrust for these new vessels.

Cross-section of the Type

Powerplant

The holland type was powered by a Vickers Petrol engine, rated for 160 hp (119 kW), to run while surfaced, venting through a telecopic pipe close to the conning tower. There was also another telescopic air intake behind. To run submerged, she had a Electric motor ratd for 74 hp (55 kW). She ran at 8 knots (9.2 mph; 15 km/h) surfaced and 7 knots (8.1 mph; 13 km/h) submerged, so almost the same, typical of Holland’s boat at the time. Such speed precluded any fleet use, but only harbour defence service as planned.

This was compounded by their poor rang, 250 nmi (460 km) surfaced at 8 knots and just 20 nmi (37 km) at 7 knots while submerged, more at lower speeds.

Armament

The Holland boat had limited internal space and also to avoid complications, a single torpedo tube was fitted, a standard caliber at the time of 14 in (360 mm) with just enough space for two more torpedoes, stored on either sides of the tube. The tube itself depending on a compressed air tank located just above. The space there was quite cramped. The opening and closing of the round torpedo hatch was manual.

The torpedo was likely the 14-in Mark IX Torpedo made by Royal Gun Factory at Woolwich. It averaged 27 knots over 600 yards in 44.7 degree water when tested in 1896-97.

⚙ Holland 1 specifications |

|

| Displacement | 110 long tons (112 t) surfaced, 123 long tons (125 t) submerged |

| Dimensions | 63 ft 10 in x 11 ft 9 in (19.46 m x 3.58 m) |

| Propulsion | Petrol engine, 160 hp (119 kW) + Electric motor, 74 hp (55 kW) |

| Speed | 8 knots surfaced, 7 knots submerged |

| Range | 250 nmi (460 km)/8 kn surf. 20 nmi (37 km)/7 kn sub. |

| Max Depht | 30 m (100 ft) |

| Armament | 1 × 14 in (360 mm) torpedo tube, 2 torpedoes |

| Crew | |

General assessment

The “Holland 1” and its class had its limitations but they impressed the Navy enough to commission a first fully proprietary British design patented by Vickers in 1902 – the A1. This new class boasted a double propulsion system, both with electric drive while submerged and petrol engines when surfaceed. HMS A13 was the first to test a diesel engine but without success. It was however clar that gasoline vapors into such a confined environment was not thre greatest idea and the diesel would come forward again. Unlike the Holland serie, the A class provided active service for two decades, mostly to train personal, quite an achievement for Vickers.

The “Holland 1” and its class had its limitations but they impressed the Navy enough to commission a first fully proprietary British design patented by Vickers in 1902 – the A1. This new class boasted a double propulsion system, both with electric drive while submerged and petrol engines when surfaceed. HMS A13 was the first to test a diesel engine but without success. It was however clar that gasoline vapors into such a confined environment was not thre greatest idea and the diesel would come forward again. Unlike the Holland serie, the A class provided active service for two decades, mostly to train personal, quite an achievement for Vickers.

It proved however still notoriously accident-prone. But nothing could have been done withut the Holland class that came with a fully matured design that Vickers had just to improve. The other important role of the Holland class, which missed WWI entirely, was of course to provide this early submarines training, the next generation starting on the A-class instead. They will all be promoted to officers when WWI and greatly participated in the role played by the British submarine fleet in that conflict.

Another incentive to order more submarines came during the Russian Baltic Fleet redeployment in the Pacific (Russo-Japanese War, up to Tsushima). While transiting in 1904 while in the fog, the “Dogger Bank incident” saw these ships taking some British fishing trawlers for Japanese torpedo boats and fire, before recoignising their mistake.

They were indeed aware of the 1902 alliance and some believed that it was a possible scenario that freshly delivered britush-built TBs to the IJN could await in ambush in international waters. The chaos saw one trawler sunk, two fishermen killed and several more injured, another one badly damaged, further degrading very difficult Russo-British relations since the late 1880s “war scare” over Asian russian crisers and decade long arm’s race. The Parliament obtained for the Royal Navy and order for 28 battleships… but also the Holland and A-class submarines, that can ambush indeed Russian Ships coming from the Baltic.

Destroyers could carry such experimental charges, that could ideally be thrown off the stern (fore-runners of the depht charges) and put themselves at risk, while inneficient if too small to effectively damage a submarine. Only two charges were to be carried. Other were resolutely optimistic about the subs offensive capabilities. They planned that a flotilla of 3–5 were a perfect deterrence for any fleet close to the port where they were based. And indeed a few years later in 1904, they were scrambled to meet the Russian Battle fleet.

The Holland type initially suffered from serious reliability problems. In 1903 an attempted circumnavigation around the Isle of Wight, on the surface, resulted in four boats breaking down after just 4 miles (6.4 km). The boats were so frequently unable to operate they were lmerely used for testing and training. As soon as the A-class boats were available, which cured all the Holland’s past issues, they would in turn be kept for training submariners and the Holland boats directed to the scrapyard.

HMS N°1

HMS N°1

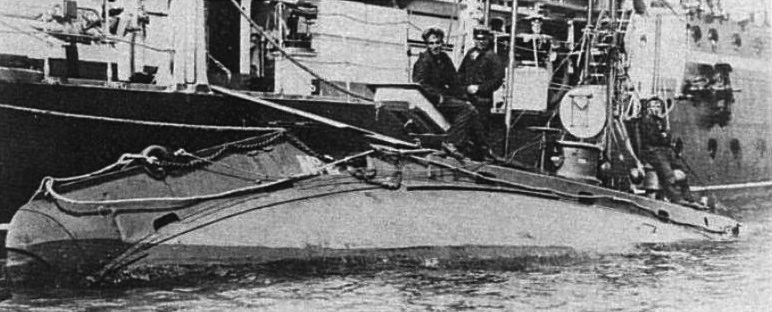

Holland 1’s keel was laid down 4 February 1901, assembled in the new famous “Yacht Shed”. In addition, parts fabricated in the general yard were marked for “pontoon no 1”. She was still launched in secrecy with only the yards and some navy personal present, on 2 October 1901. After initial training or British sailors with US ones, she dived for the first time in an enclosed basin on 20 March 1902. Her sea trials only begun from April 1902.

In September 1902 the First Submarine Flotilla, commanded by Captain Reginald Bacon arrived in Portsmouth. It consisted of two completed Holland boats and the gunboat H.M.S. Hazard that served as a floating submarine base. Captain Bacon recognized how dangerous the new submarines could be and proceeded cautiously with training his small band of volunteer officers and men. There were accidents and disappointments but just a few months later Captain Bacon reported that :

“Even these Little Boats would be a terror to any ship attempting to remain or pass near a harbour holding them”.

And also:

“…..the ingenious designer in New York evidently did not realize that the average Naval Officer has only two eyes and two hands: the little conning tower was simply plastered with wheels, levers and gauges with which some superman was to fire torpedoes, dive and steer and do everything else at the same time…”

From the 1902 diary of Lt. Arnold Fosters Royal Navy’s first submarine commander.

While in Portsmouth, along with HMS Holland 2 boat they were soon joined by their dedicated tender HMS Hazard. The latter was a former Dryad-class torpedo gunboat (1892), reconverted for the purpose that year. Together the two subs and their tenders made the Royal Navy’s “First Submarine Flotilla” under overall command of Captain Reginald Bacon. HMS Holland 1 however suffered an explosion on 3 March 1903 due to gasoline vapors, but fortunately only caused four injuries.

On 24 October 1904, she was scrambled with the four other Holland boats and three freshly commissioned A-class boats, from Portsmouth to the north sea, looking to attack the Russian Baltic fleet which just mistakenly sunk a fishing trawler near the Dogger Bank. They were all recalled before interception as dimolacy prevailed though.

Eventually Holland 1, used to train until then future A and B class submariners, arrived at the end of her useful life in 1913. She had been also caught up by rapidly advanced technology and in the worst shape compared to her sisters.

HMS Holland 1 was thus decommissioned, sold for BU in 1913 to Thos. W. Ward for “just” £410. (not many steel to cut out here !). However what happened next added a new twist to her history. When sold she did not have been even stripped of her fittings, which were all intact. However before purchase, Thos. W. Ward wanted her torpedo tube to be deactivated.

While towed to the scrapyard, the towed boat encountered foul weather, and due to leakage or possibly caused by the torpedo hatch being left open, she sank a mile and a half off Eddystone Lighthouse. The Tug’s crew saw her already slowly sinking beforehand and simply released the tow rope, preventing damage to the tug and knowing there was nobody onboard anyway. This was considered a small loss for the Yard anyway.

The wreck was located in 1981 by Plymouth historian Michael Pearn. She was raised, with the full support of the RN, in November 1982. From 1983 she was coated with anti-corrosion chemicals, restored the best possible and first displayed at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum. But in her state, she was not suitable for a visit. Thus, full restoration plans started soon and went on until September 1988. By 1993 the treatment she had soon proved inadequate and she degraded fast again. To prevent further damage it was decided to immerse her in a A fibreglass tank filled with a sodium carbonate solution, and she stayed there from 1995 to 1999. The corrosive chloride ions being removed, painted anew and reequipped for display she reopened in 2000.

She is now listed as part of the National Historic Fleet (alongside HMS Victory and Warrior among others). In 2001 for her centenary, a new purpose-built climate-controlled building was created around her financed by the Countess Mountbatten. In 2011 she was given an Engineering Heritage Award, by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Her original batteries were later restored by their original manufacturer, Chloride Industrial Batteries Ltd (Swinton) and even recharged and tested. She is now cutout for easy access, opened to public at Gosport.

HMS N°2

HMS N°2

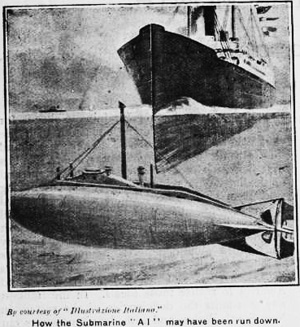

Holland 2 was the second Royal Navy submarine built and had now a non-secret launch in February 1902, being laid down on 4 February 1901. She was commissioned on 1 August 1902 and during her first trials, set the depth record for any British Holland-class. It however was not willful, but an accident. She dove way to quickly to 78 feet. Technically these were rated for 100 feets, but of calculated crushing depht, certainly not a reachable value in normal times. In usual, dives were done at less than 15m (50 fts). In December 1902 she sustained minor damage: A strong current was sufficient due to her anemic power sending off course. She surfaced directly underneath a brigantine and “scrapped her belly”. After a training and tasting career withut much else to report, she was quitely retired in 1911 and sold for BU on 7 October 1913.

HMS N°3

HMS N°3

Number 3 was launched on 9 May 1902, laid down on 4 February 1901, commissioned on 1 August 1902. Her frist captain was John Alfred Moreton, appointed to the submarine depot ship HMS Hazard and also of HM Submarine No.3. She was the first truly accepted in service with N°5 as the others went into many mishaps delaying it. She went on testing until 1911, and sank during a dive. She was refloated later and sold for BU on 7 October 1913.

HMS N°4

HMS N°4

Holland No 4 was laid down in 1902, launched on 23 May 190 and completed, then went through its deep sea trials in the Irish Sea, in August 1902. She was commissioned at last on 2 August 1903. Apparently she was completed with the same small conning tower as the others but a “sail” was added in 1905, although there is no photo to show it. After an uneventful short career of test dives and manoeuvers, she was stricken in 1912. Probably under tow to her breaker, she foundered on 3 September 1912, was salvaged and ended as gunnery target on 17 October 1914.

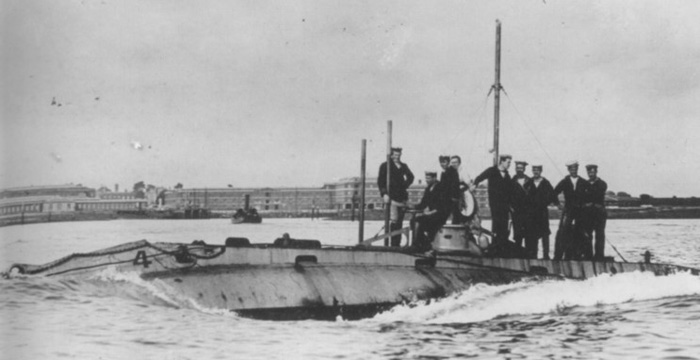

HMS N°5

HMS N°5

HMS N°5 was the second (after N°3) submarine accepted into Royal Navy service. This was on on 19 January 1903. On 4 March 1903 she was assigned the five-boat Holland-class flotilla, providing a demonstration for Captain Reginald Bacon in Stokes Bay. During this event there was a spark and emanations from the gasoline engine that trigerred an explosion on Holland 1, whic cut shot the even. Reduced to the role of harbor defense and training afterwards she made another display on the Thames River on 1909, and not considered “seaworthy” anymore by the media otr the navy istelf. In 1910, Holland 5 ran aground off Fort Blockhouse close to HMS Dolphin, home of the Royal Navy Submarine Service, not a good omen.

By 1912, decision was made to scrap her and her sisters. While en route under tow bound to Sheerness, she sank in the English Channel off Beachy Head, Sussex for unknown reasons. The same was advanced as for HMS Holland 1: A leaking or unshut torpedo tube hatch, which cause a massive leakage.

Her Wreck was discovery in September 2000, under 98 ft (30 m), 6 miles (9.7 km) off Eastbourne. In April 2001 an Archaeological Diving Unit scanned the area and recoignised, confirmed it as she sat upright on the seabed, reinforcing the hypothesis of a gradual flooding. On 4 January 2005, Andrew McIntosh (Minister for Tourism and Heritage) announced it was added to the list of Protection of Wrecks Act. Despite of this in 2010, it was discovered that the torpedo tube hatch had been stolen. The last dive on her wreck was on 2008, and she had been further damaged by fishing nets, torning off the periscope and deck implements.

Read More

Books

Hutchinson, Robert (2001). Submarines War Beneath the Waves From 1776 to the present day. HarperCollinsPublishers.

Compton-Hall, Richard (1983). Submarine boats The beginnings of underwater warfare. London: Conway maritime press.

Dunmore, Spencer (2002). Lost Subs From the Hunley to the Kursk, the greatest submarines ever lost – and found. Madison press books.

Tait, Simon (1989). Palaces of Discovery The Changing World of Britain’s Museums. Quiller Press.

“Holland I Conservation”. Holland 1. The Royal Navy Submarine Museum.

Chamberlain, Zoe (6 April 2001). “Sailors give a stamp of approval”. Mail (Birmingham).

“Holland One submarine given engineering award”. BBC News. BBC. 4 May 2011.

Hutchinson, Robert (2001). Submarines War Beneath the Waves From 1776 to the present day. HarperCollinsPublishers.

“Naval & Military intelligence”. The Times. No. 36903. London. 20 October 1902

Compton-Hall, Richard (1983). Submarine boats The beginnings of underwater warfare. London: Conway maritime press.

Gray, Edwyn (2003). Disasters of the Deep A Comprehensive Survey of Submarine Accidents & Disasters. Leo Cooper.

Hutchinson, Robert (2001). Jane’s submarines : war beneath the waves from 1776 to the present day. HarperCollins.

Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holland-class_submarine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Philip_Holland

http://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/submarines/pages/holland_class/holland_1_page_1.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20160919222425/http://www.submarine-museum.co.uk/what-we-have/our-submarines/holland-1

https://www.williammaloney.com/Aviation/FenianRam/index.html

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-hampshire-13277022

http://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/submarines/pages/holland_class/holland_2_page_1.htm

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign