HMS Canada (ex-Almirante Latorre) 1914

HMS Canada (ex-Almirante Latorre) 1914WW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

The Chilean take on the south American Naval arms race

HMS Canada was a unique battleship in the Royal Navy, and just like the HMS Agincourt and Erin, one of those ordered abroad and requisitioned while on completion when the war broke out in August 1914. Explaining while she was a Chilean order, is to describe the naval arms race started by the Brazilians with the Minas Gerais, answered by Argentina with the Rivadavia but Chile, out of cashed, delayed their order. The closed ties bewteen the Chilean and British Royal Navy ensured they eventually ordered in 1911 two “super-dreadnoughts” in theory head and shoulders above those aforementioned. Eventually, while the international situation degraded following in particular the Balkans war that year, Almirante Latorre was launched in November 27, 1913, while her sister ship Cochrane was nowhere near that stage. By that time the new fast battleships of the Queen Elisabeth had the utmost priority, and her keel only had been laid down in February 1913.

In August 1914, Churchill, then first lord of the admiralty ordered all ships in construction for export to be suspended or requisitioned according to the degree of their construction. The British Government requisitioned the Sultan Osman (Agincourt), pushing the Turkish Government into the arms of the triple entente, but took better care with Chile. The British government indeed needed badly sulfur and nitrates used in shells charges manufacturing and in general vital to its war industries. Churchill contacted the Chilean embassy and struck an agreement to complete the battleship at British expense, “loan” it for the duration of the conflict and return it to its original owners afterwards. It was formalized on 9 September 1914.

It took however one more year for HMS Canada to be completed, its crew trained, and be commissioned. She went to the 4th Wing of the Grand Fleet in Scapa flow, and spent a year between routine exercises at sea and sweeps to try to lure out the Hochseeflotte out at sea. She fought at Jutland and returned to her routine service until the end of the war, with an assignment until 1919 to the 1st squadron, a sweep in dry dock to clean her up and some modernisation, before official transfer in April 1920 to Chile. Almirante Latorre would remain active until 1959, far longer than other requisitioned ships such as Erin and Agincourt.

Genesis: The Latorre class

We will not dwelve in detail into this part, since it has been covered already in detail for the Latorre. It was originall ordered in the context of the second naval race, this time between Chile and Argentina over territorial disputes about Patagonia and Puna de Atacama and the Beagle Channel. The last 1902 race was settled by a British mediation.

But Brazil, left out of it until the HMS Dreadnought was commissioned, in early 1907 changed its order for three pre-dreadnoughts for three dreadnoughts. The Minas Geraes class caused sensation at the time, not least for Argentina and Chile which were found in clear inferiority. Debates raged in Argentina about countering this but disputes on the River Plate decided the order of the Rivadavia-class, built by US Yard Fore River Shipbuilding. Chile asked for tenders in turn, both from the US and Europe, and the commission worked on a design that would outclass both.

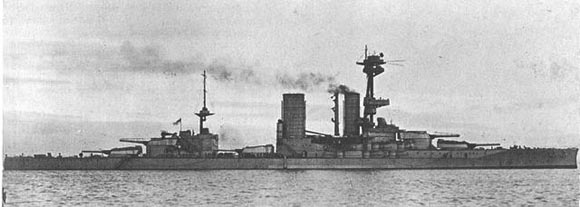

HMS Canada in full regalia during a review in Scapa Flow, 1915 or 1916

On 6 July 1910, the National Congress of Chile allocated by law 400,000 pounds sterling each year necessary to purchase and maintain two 28,000 ton battleships. The admiralty and parliament agreed on their name quickly; They would be the Almirante Latorre and Almirante Cochrane. But the naval bill also consisted in an order for six destroyers and two submarines. Armstrong Whitworth submitted its proposal, based on the King George V, which was accepted, and awarded on 25 July 1911. Almirante Latorre was the first ordered, on 2 November 1911. It was laid down on 27 November. Armstrong Yard’s visitors at the time were invited to see the start of the largest battleship ever built in UK at the time. The New York Tribune reported a purchase attempt by Greece on 2 November 1913 during the war scare with the Ottoman Empire. Chile in between had financial difficuties and some thought of the sell, but the Government eventually vetoes this and the purchase negotiations ended.

Almirante Latorre was eventually launched on 27 November 1913. The elaborate ceremony attending comprised numerous dignitaries, including Chile’s ambassador, Agustín Edwards Mac Clure. Latorre was christened by his wife, Olga Budge de Edwards. She was quite a fantastic sight, larger than other British dreadnoughts of the time, Minas Gerais or even Rivadvia for that matter. Their artillery was above average (still not equivalent to the future 15-in manufactured by Great Britain) and they were fast on paper, reaching and estimated 22.5 to 23 knots in trials. Protection was not outstanding though, but well thought out.

From Latorre to Canada

In August 1914, there were discussions about the purchase or requisition of the Almirante Latorre. While Erin (Reşad V or ‘Reşadiye’) and Agincourt (Sutlan Osman I) both had been forcibly requisitioned, jeopardizing relations with the Ottoman Empire, Churchill took extra care to spare the same humiliation to the Chileans. For one, due to the traditional links between the Royal Navy and Chilean Navy, and because UK depended heavily on some exports of Chile vital for its war industry. Behind this was even the whole Allies’ reliance on Chilean Sodium nitrate for munitions, so that was a crucial case.

In the end, the status of “friendly neutral” allowed to propose a Gentleman agreement of completing the ship’s to the government expense in exchange for its use during the war. It was not a loan though, the ship was formally purchased by the United Kingdom on 9 September 1914 and renamed HMS Canada. The long delay before its commission was due to some factors, like for the Agincourt and Erin: She was slightly modified for British service: The original enclosed bridge was removed and two open platforms built instead. A mast was also added in between the two funnels, supporting a derrick to service launches. Also a new documentation was written and all instructions in Spanish throughout the ship removed and replaced. The fitting-out on was complete 20 September 1915, so one full year after her purchase, while crews had been constituted and trained. HMS Canada was officially commissioned on 15 October.

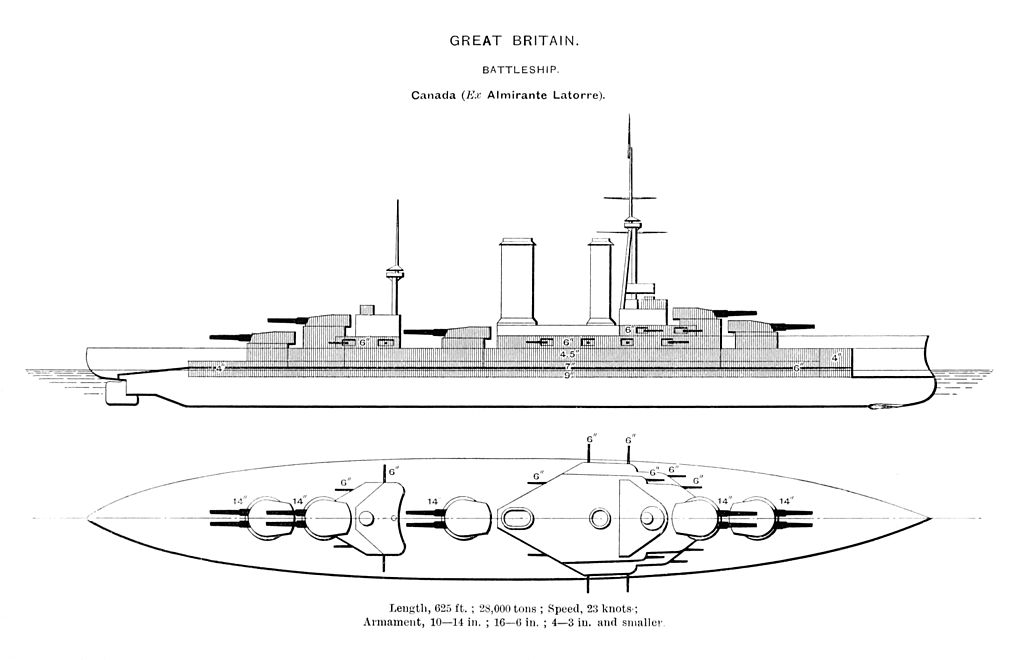

Design

HMS Canada displaced 28,600 long tons (29,059 t) loaded standard, and 32,120 long tons (32,635 t) fully loaded, so much more than the King Georges V they were inspired by (25,420 tons/28,000 tons). She measured 625 ft (191 m) overall by 92.5 ft (28.2 m) in beam and 33 ft (10 m) in draught, so much larger also (Ten meter longer, one beamier).

Powerplant

Since she was rather large, the room inside was use to use more boilers: four shafts, 21 Yarrow boilers, with low pressure Parsons turbines on the outer shafts and and High pressure Brown-Curtis steam turbines for the inner shafts, and a total output of 37,000 shp (27,591 kW). The boilers were all burning coal, but had fuel injectors. Top speed was 22.75 knots (42.13 km/h; 26.18 mph), so better again than the KGV (21 knots). Range was about 7,500 nm, versus 6,310 nmi for the KGV.

Armament

Main guns: 14-in/45 BL Mark 1

The main armament was copied on the KGV too, with five turrets, two superfiring pairs fore and aft and one amidship. But as the latter were 13.5 inches (343 mm) and it looked a bit too weak compared to the 12-in armed Minas Gerais ad Rivadvia which had two more guns (12). Instead, the yard proposed the Chileans to simply enlarged the standard 13.4 in bore, producing barrels reaching a caliber of 14-inches (356 mm). The shell was much heavier and harder-hitting than 12-in shells as a consequence, with larger range as well. Latorre as approved, ended armed with ten of such guns, the largest in inventory worldwide at the time. These were 45 caliber guns specially crafted for Chile as the admiralty preferred more standardized models, the 13.5 and the 15 in. If never ceded to Chile after the war, this oddball battleship would probably had a limited service like the Agincourt or Erin, expiring in 1922.

This 14-in Mark I designed by Elswick was of a classic wire-wound construction with a three-motion short-arm breech mechanism. Fourteen were manufactured plus four spares but only ten were used, the rest being scrapped after the war in 1922 as the second ship ended transformed as a CV, for which ten additional were ordered, but three were requisitioned and ended on railway mountings.

The muzzle velocity and shell weight were essentially the same as for the Mark VII used by the second King George V class of 1940.

The total gun weight, with mount, was 84.75 tons (86.11 mt) and the barrel measured 648.4 in (16.469 m) for a bore Length of 630 in (16.002 m), a rifling Length of 529.8 in (13.457 m), 84 grooves 0.12 in deep x 0.394 in (3.05 mm x 8.86 mm) and an uniform twist RH 1 in 30. The chamber Volume was 23,500 in3 (385.1 dm3). These 14-in had a rate of fire of circa 2 rounds per minute in optimal circumstances, same as the 13.5 in.

They could fire four types of shells: The common APC Mark Ia – 1,586 lbs. (719 kg), the Mark IIIa (Greenboy) 1,595 lbs. (723.5 kg), a CPC round 1,586 lbs. (719 kg) and the classic HE round, 1,586 lbs. (719 kg). It used a bagged 344 lbs. (156 kg) MD45 Propellant Charge. Muzzle Velocity was 2,500 fps (762 mps) and calculated barrel life around 350 rounds. 100 rounds were stored per gun, so 500 total split between HE and AP. The range was 19.55 degrees at 24,000 yards (21,950 m) and at 1,336 fps (407 mps) at a 30° angle. On a vertical plate, they penetrated 53.2 in (135.1 cm). They were still a very serious proposition in WW2.

Secondaries and lighter armament

Latorre/Canada also carried sixteen 6 in (152 mm) guns of the standard type, in casemates along the hull. Eight were in the forecastle behind a recess, three in the forward superstructure abaft the surperfiring B turret. The last two were in the aft island superstructure, behind the amidship turret.

In addition, HMS Canada carried also two 3 in (76 mm) anti-aircraft guns installed on the front superstructure roof, and four 47 mm (1.9 in) guns used as saluting guns. Inside the hull were located four 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes in the broadside, individual and submerged.

Fire control systems

-1915: Two cam-type installed, tripod-mounted directors. In the armoured tower and light aloft tower and directing gun in “X” turret.

-1917: 6-in guns direction moved to the fore top, with combined range and deflection repeat receivers

-1918: Turret Elevation Receivers Mk.3 (15° elevation), Training Receivers of double dial type, Mk.12.

-1918: 6-in guns directed by two pedestal-mounted directors (February) port and starboard forward.

Elevation Receivers 6-in P.VII Type, with electrical tilt correctors Mk.22. 15° elevation. The Small Type Training Receivers Mk.18.

Torpedo Control installed and modified 1915: Plotting Instrument Mark II, in TCT.

-1917: Common Torpedo Control packages provided and Torpedo Control Data between C.T. and T.C.T. and Evershed transmitters in the C.T. and receiver at the torpedo rangefinder T.C.T.

-Mid-1920, Renouf Torpedo Tactical Instrument Type B.

Transmitting Stations: Dreyer Table Mark IV* in 1915 and by 1916, range rate transmitter/receiver pair for the main armament.

Armour protection

The weakest point of the design, assuredly. To reach the desired speed, the armour plating was not on par with the artillery caliber, by quite a margin. The belt was protected by 9 in (230 mm) plating between barbettes, thinned down fore and aft. The main armoured deck was 1.5 in (38 mm) thick, Main gun barbette reached 10 in (254 mm) above the deck and 4 feets below, while the turret faces were also protected by 10 in (254 mm) plating, sides, and probably 8-in for the back and 6-in for the roof. The Conning tower had 11 in (280 mm) walls. This was less than the KGV class, which had a 12-in belt, 11-in turrets and CT, and up to 4 in for the armored deck. Despite of this, HMS Canada fare well and was not quite endangered at Jutand.

HMS Canada in 1916 or 1917 – Imperial War Museum src

The fate of Almirante Cochrane

The situation of Latorre’s sister-ship, Cochrane, was more problematic as her completion was not possible on behalf of Chile in time. Too much work had to be done. And other priorities commanded a different course of action than for Latorre. Her construction was brought to full stop, and the government signified that any completion would be done after the war, which Chile understood. But plans changed in between, and with the need for large hulls for carriers, an agreement was struck with Chile, and the latter agreed to “redeem” the ship to allow the British admiralty to convert the unfinished hull into an aircraft carrier. And so she was launched in June 1918. Many of the design peculiarities of this conversion emerged in light of the difficulties encountered with the Furious. This time the admiralty wanted a fast flush-deck hull building with a large area, and this hull met such expectations, allowing a design to be formalized and approved in December 1918. of the course the war ended well before completion was done in April 1920. She was christened HMS Eagle and came to be the mainstay of British naval aviation while proving as disappointing as Hermes in operations during the war. See the career of HMS Eagle.

HMS Canada in action:

HMS Canada’s first assignment was with the 4th Battle Squadron, Grand Fleet, in Scapa Flow. Her early service was largely uneventful between routine exercises and sorties in the north sea to try to lure out the Hochseeflotte in a decisive combat.

HMS Canada at Jutland:

HMS Canada saw action at the Battle of Jutland, under orders of Captain William Nicholson. In total she fired 42 main guns rounds and 109 secondary guns rounds during it. She was not hit once, and sent two salvoes on SMS Wiesbaden, fired five more at an unknown target around 19:20 plus its 6-inch guns on German destroyers about that time.

From captain W. C. M. NICHOLSON journal, June 2, 1916:

On 31st May, 5.10 p.m., the Fleet was heading S.E. by S. in 5 columns to Starboard, and the signal was made for Light Cruisers to take up position. 6.10: signal to 3rd and 8th Flotillas was “Take up position for approach.”, the battle line was formed at 6.15 S.E. by E. at 18 knots. HMS Canada started firing at 6.38 until .45, two salvoes on a cruiser which was badly battered, but stayed unidenfified due to the poor weather (it was the Wiesbaden) and also obscured by smoke splashes. At 7.15 she engaged destroyers and repelled them, the latter releasing a smoke screen.

At 7.20 she fired four salvoes at an unidentified battleship or battle-cruiser spotted at starboard beam, and probably of the “Kaiser” class (or Derfflinger). Engaged at 13,000 yards, after the fourth salvo she disappeared a probable smoke screen. At 7.25, signalled to turn 2 points away from enemy and second 2 points after 2 more minutes. At the same time, engaged destroyers attacking abaft starboard (6-inch again). Broadside divided between leading boat and right-hand boat. 7.30: Fired three main guns salvoes on leading attacking destroyer, abaft starboard beam. Third salvo hit. Vanished in smoke, believed sunk. Right-hand destroyer straddled by secondaries, sight lost. Fire ceased at 7.35 and 5 min. later, signal given: “Single Line ahead, course S.W.”

The Battle ended for HMS Canada. She had no damage or casualties to report so she was extremely lucky given the other losses of the day, Warspite almost sank, three battlecruisers lost.

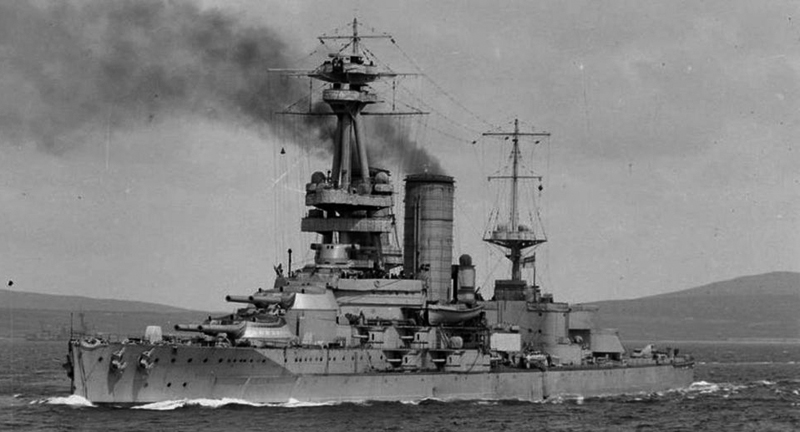

HMS Canada, probably in 1917: Her turret tops were painted in dark grey. Later she would receive additional AA and a take-off platform on her ‘X’ turret (pinterest).

Post-jutland service

HMS Canada was transferred to the 1st Battle Squadron (12 June 1916) and the next years, in 1917–18, she received better rangefinders and range dials. Two aft 6-inch secondary guns were removed after blast damage received from the amidshsip 14-inch turret. In 1918 a flying-off platform was added atop the first, and later, aft superfiring turrets. HMS Canada joined the reserve fleet in March 1919.

Life on board: Sunday morning inspection in February 1917 (top), group photo of the crew aft in 1916 or 1917 (cc)

HMS Canada in 1918, note the aft platform with a recce sopwith Pup

Post-war transfer back to Chile

After the war ended Chile still needed modern ships to bolster its fleet and the United Kingdom by then offered its surplus warships. It even included her two remaining Invincible-class battlecruisers. In Chile discussions about acquiring the latter caused an uproar in the country. Inside the naval staff, a faction of young naval officers publicly denounced this move in press and instead promoted submarines and aircraft, arguing of their lower costs and performance demonstrated during WW1. While it happened, Brazil and Argentina wonder what to do next if Chile acquired these battlecruisers, possibly starting another naval arms race in 1919. These debates through press and the parliament ended with a compromise. In April 1920, Chile re-ordered the destroyers which were already purchased before the war (and requisitioned) but for a total cost for five ships which only a third of what Chile still had to pay, and same for Almirante Latorre, the ex-Canada which was going to return to its original owner, as agreed between the two governments in September 1914. She was formally handed over to the Chilean government on 27 November 1920 and departed Plymouth with two destroyers, Riveros and Almirante Uribe, under overall command of Admiral Luis Gomez Carreño. They arrived in Chile on 20 February 1921, welcomed by Chile’s president, Arturo Alessandri. The battleship became the flagship of the Chilean Navy for the next 40 years.

Almirante Latorre in 1938

Links

The Canada on wikipedia

Canada on the Dreadnought Project

//www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_14-45_mk1.php

//www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205127844

//www.jutlandcrewlists.org/canada

//www.iwm.org.uk/search/global?query=hms+canada&pageSize=

A.Preston, Robert Gardiner, Randal Gray Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

Burt, R. A. British Battleships of World War One. Naval Institute Press

Campbell, John. Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. New York: Lyons Press, 1998. ISBN 1-55821-759-2. OCLC 41176817.

Garrett, James L. “The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone”. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 27

Gill, C.C. “Professional Notes”. Proceedings 40: no. 1 (1914)

Kaldis, William Peter. “Background for Conflict: Greece, Turkey, and the Aegean Islands, 1912–1914”. Journal of Modern History 51

Livermore, Seward W. “Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925”. Journal of Modern History 16

Scheina, Robert L. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Naval Institute Press

Somervell, Philip. “Naval Affairs in Chilean Politics, 1910–1932”.

Whitley, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.

Worth, Richard. Fleets of World War II. Cambridge

US National Archives at College Park, Maryland, declass. files on armament control.

Author’s profile of HMS Canada in 1914.

Canada specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 191 x 28,2 x 10 m |

| Displacement | 28,600 t, 32,120 T FL |

| Crew | 834 |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Parsons/Brown-Curtis turbines, 21 Yarrow boilers, 37,000 hp. |

| Speed | 22.7 knots (44 km/h) |

| Range | 6,680 nautical miles (12,370 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Armament | 10 x 356 (5×2), 16 x 152, 2 x 76 AA, 4 x 47, 4 x 457mm (Sub, sides) TTs. |

| Armor | Belt 230, citadel 115, Barbettes 230, turrets 250, CT 280, deck 100 mm. |

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign