United Kingdom: 80 battleships 1890-1918

United Kingdom: 80 battleships 1890-1918WW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

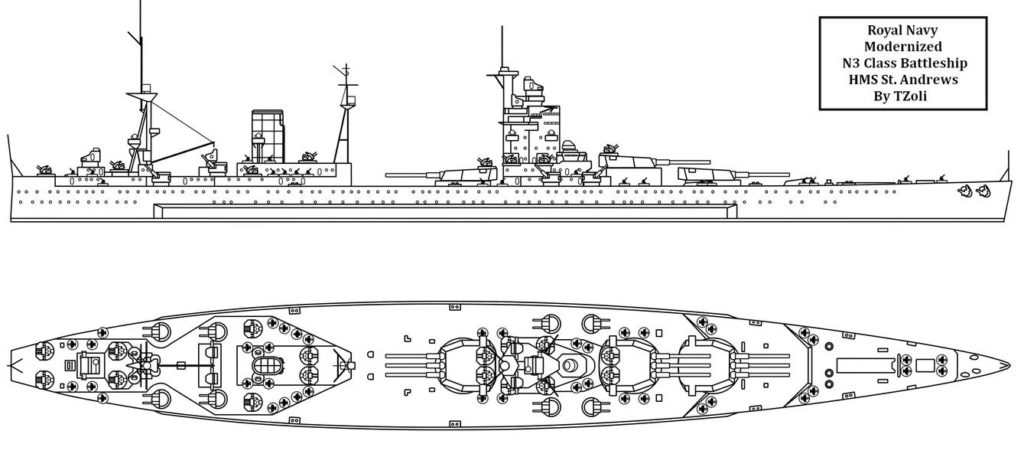

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

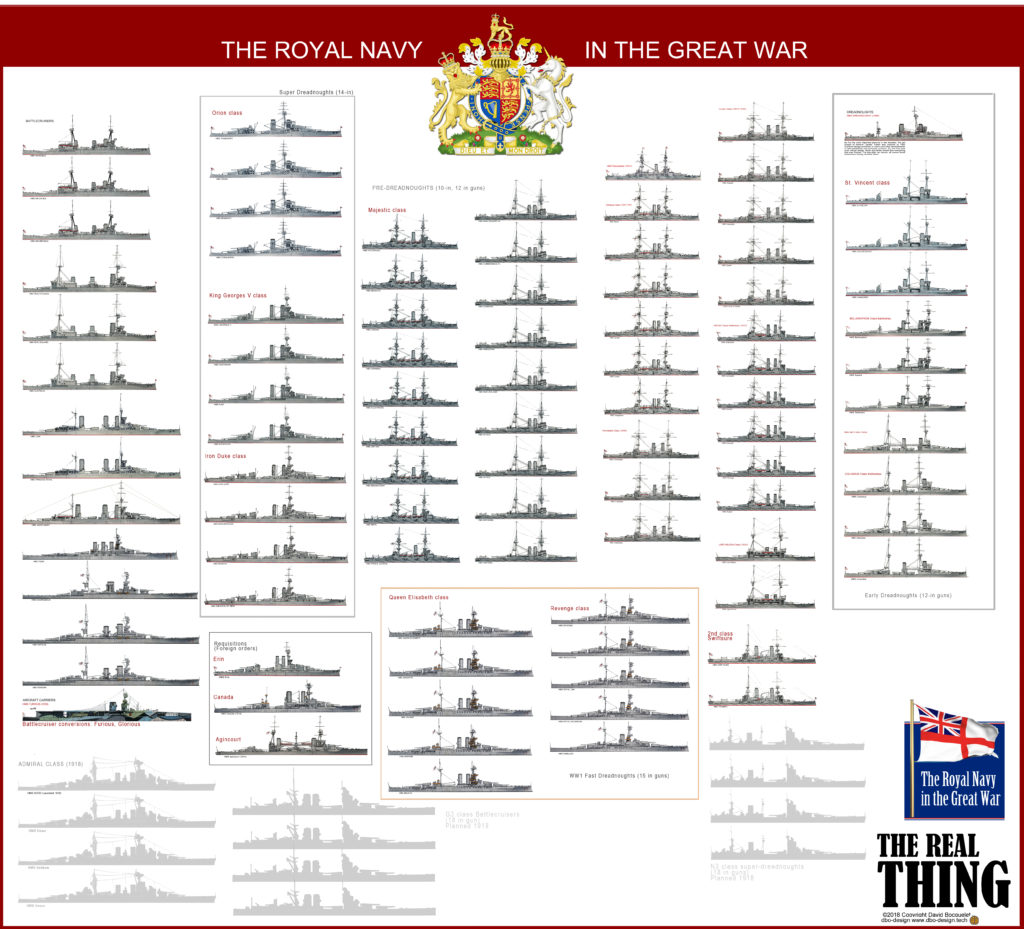

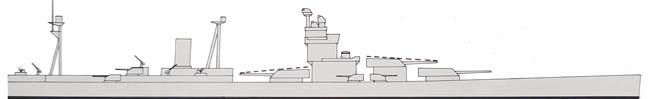

Overview poster of British Capital Ships in WW1, including projects (light grey)

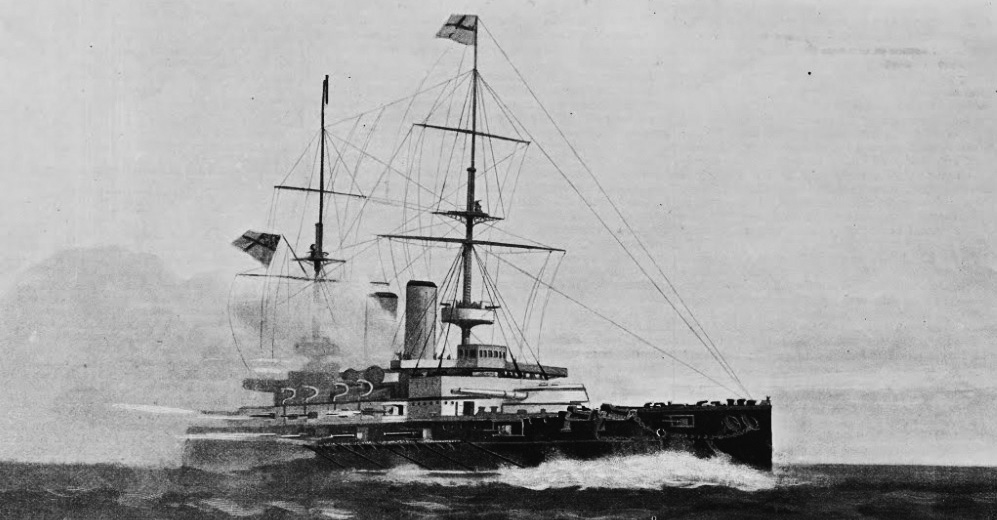

British Battleships of WW1 comprised three types of vessels: Dreadnoughts, 21 of them which made the meaty bulk of the Royal Navy, 12 Battlecruisers, and 51 pre-dreadnoughts. They were basically a deterrence force stockpiled in the firth of Forth to block any move in the Atlantic from the Kaiserliches Marine.

Battlecruisers were the cavalry, able to probe deep into the north sea or catch enemy battlecruisers, while pre-dreadnoughts were either in additional reserve in Scotland, or spread throughout the Empire, fighting in less contested theatres of operation such as the Mediterranean, Africa, the Falklands or the Indian Ocean and the Far east.

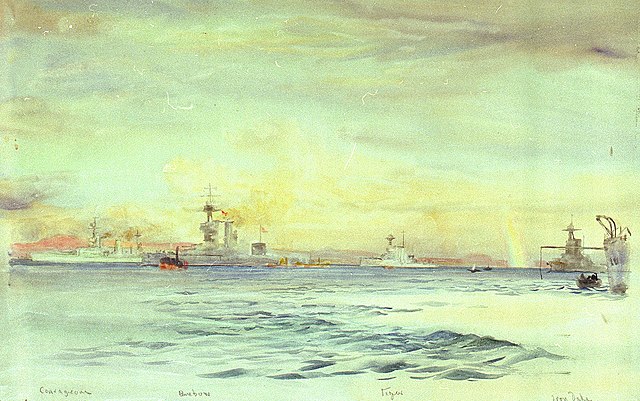

The Grand fleet at Scapa Flow

It should be recalled two facts:

1-The Royal Navy prior to 1914 still clung to a 70+ years old doctrine: Having twice as much firepower than the next two world’s best navies combined.

2-The opposing naval strength in 1914, with a small and trapped Austro-Hungarian Navy* and smaller Turkish Ottoman Navy soon trapped in the black sea, there was only the German Empire which was of some concern.

*Which in addition, thanks to a gentleman’s agreement between France and UK, left the Mediterranean to the French fleet.

This picture in the end should have left the bulk of this capital ship force logically placed where it should for any move of the Kaiser’s Hochseeflotte. But Hipper never really succeed in drawing these forces to a screen of torpedo carriers in ambush in order to reduce the Grand Fleet, before any decisive clash in the high sea. Instead, battlecruisers and lighter ships were nearly constantly in action whereas lumbering dreadnoughts made very few sorties during the war, with the exception of the battle of Jutland, which remained indecisive.

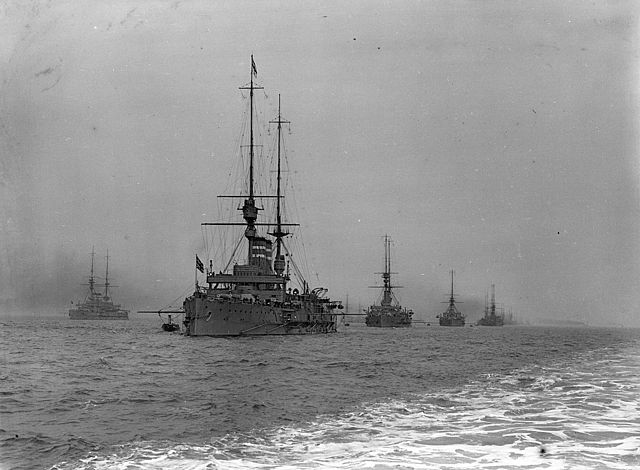

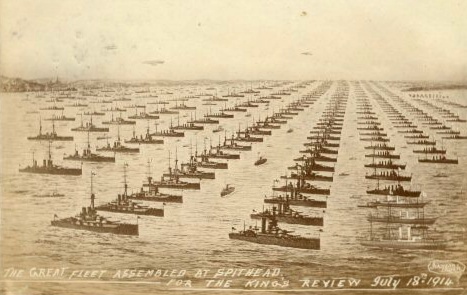

Spithead naval review of 1897

Built for prestige or necessity, both immense, modern battle-fleets of Albion and Germania almost never fought. And both played their deterrence role to the full until the major opponent, Germany, saw her undefeated and largely untested capital fleet interned, scuttled, and as for the draconian Versailles Treaty, never to be reconstructed again.

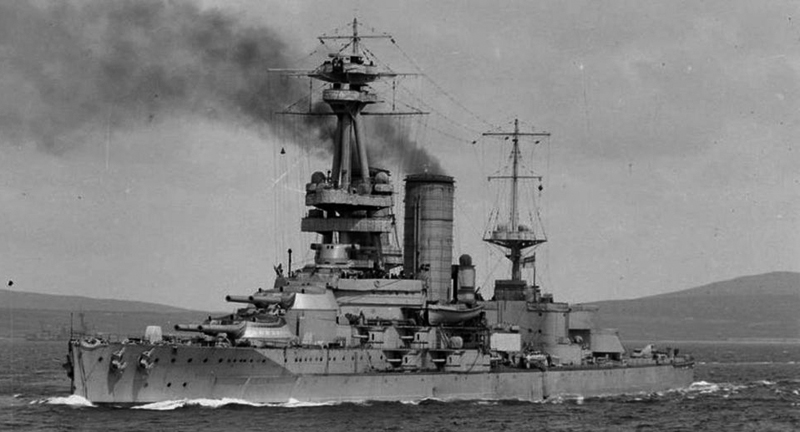

This left the Royal Navy with an immense obsolescent fleet of battleships in 1918, 80 of them, virtually useless in the interwar world. The Empire could be defended by heavy cruisers and budget cuts plus the Washington treaty led this steel mass back to the scrapyard, until it was down to the last ones, the Queen Elisabeth and Resolution classes, which took the brunt of the action during WW2. It happened as the picture was much more challenging: With only 23 battleships and France out of the picture in 1940, the Royal Navy stood alone against former allies of the great war, Italy in the Mediterranean and Japan in Asia, and a Kriegsmarine which still posed a serious threat.

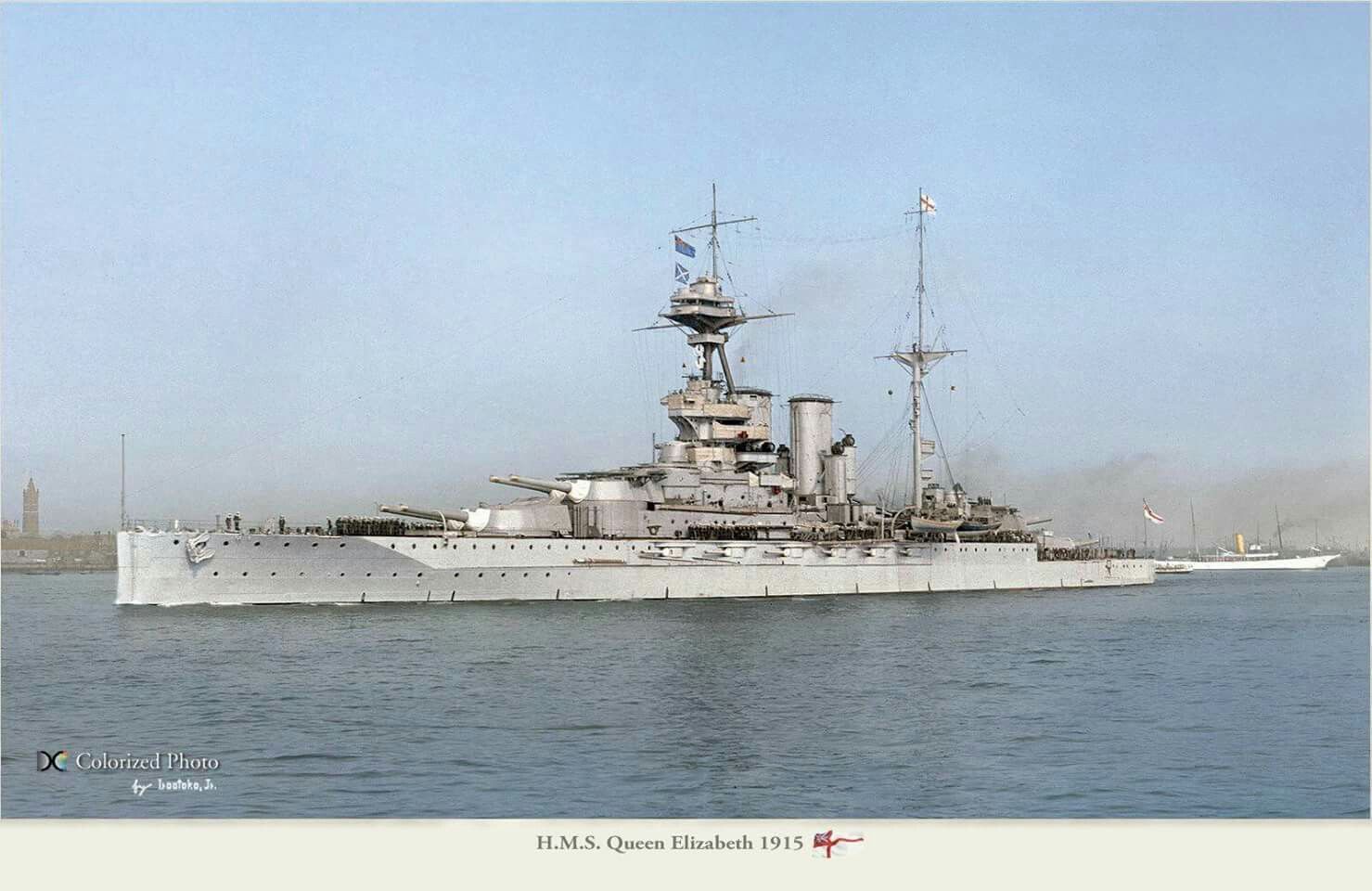

This does not prevented the admiralty to search for follows-up on her designs. In 1913 she introduced the oil-fired super-dreadnought with the Queen Elisabeth class, faster and better armed, but still in line with previous development, when it appeared the frontier between battlecruisers and dreadnought were started to blend, as shown by the Admiral class, cut short to the Hood. In this context, the Nelsons were an interesting, derogatory (to Washington) proposition. Not yet fast battleships, but no longer dreadnoughts.

A general view of Line B with the battleships at anchor during the Royal Naval Review at Spithead

An introduction: From Devastation to Trafalgar

The path followed by British capital ships of course came from ships of the line, wooden stacks of primitive artillery inherited from the days of Nelson, still very much alive in 1850, but in the process to be converted as steamships. The 1860-1880s saw a technological revolution in a grand scale, and from the Warrior to the Devastation, scores of masted or steam-only capital ships appear, with successively broadsides, central citadels, and turrets.

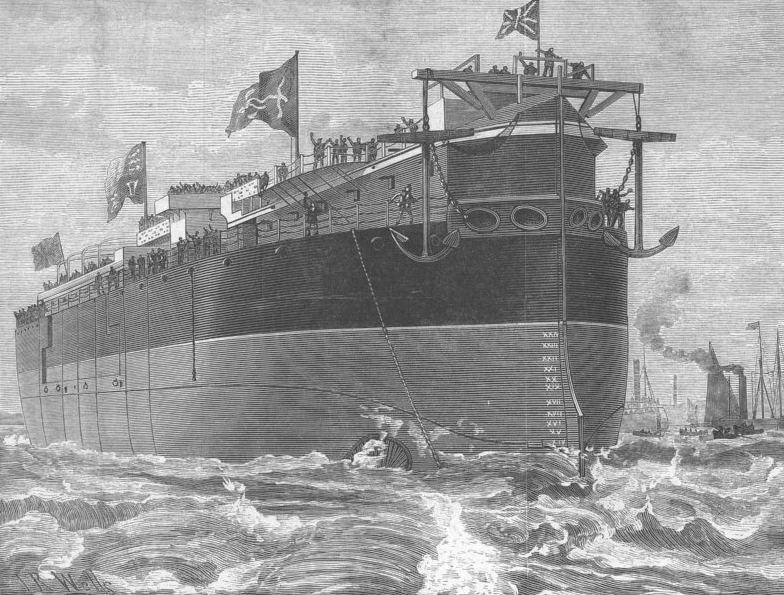

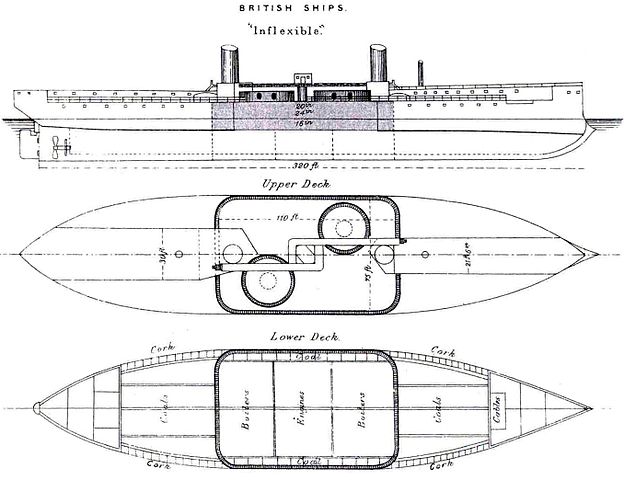

All this is covered in the 1870 Royal Navy section. We will left aside the coastal vessels Rupert, Cyclops class, the last masted turret ships, Neptune, Inflexible, Agamemnon and Colossus classes, which were arguably less advanced, the one-turret Conqueror classes.

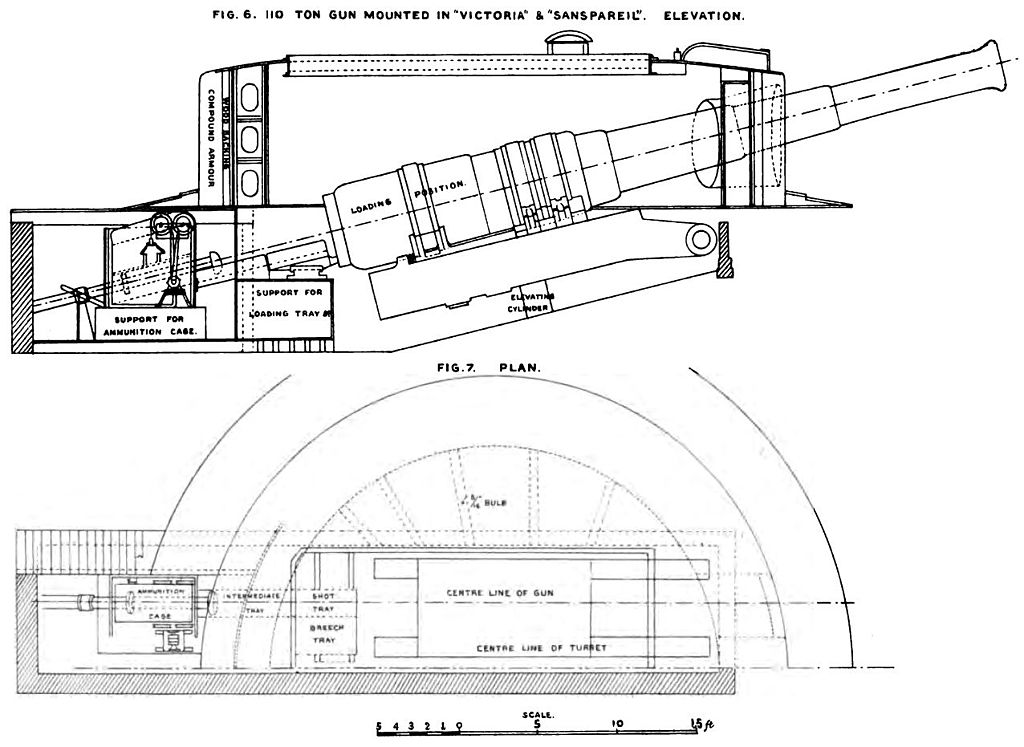

BL 16.25 inch gun turret diagrams Brasseys 1888

Devastation class (1870)

HMS Devastation and Thunderer were indeed very modern-looking ships when laid down in Pembroke DyD in 1869. Barely four years after the American civil war and its wooden fleets, ten years after the Warrior, these two steel-hulled turreted behemoths designed by Ed Reed were nothing shot of revolutionary in all senses.

These ships were designed by Sir Edward Reed, which along the admiralty request proposed a short, handy ship of medium size, but as heavily armed as possible, agile, and well protected. She devised a kind of high seas monitor (after all this was 5 years after the end of the American civil war), and ocean-going monitors like the USS Dictator (1863), but more heavily armed, better suite for the high seas, and steam-alone. Requirements included two twin 12-inch gun Coles turrets firing 600-pound shells, with a 280-degree firing arc of fire, which included a position fore and aft of the main superstructure. Despite of this, echelon solution would last for well above ten more years.

This turrets needed 14-inch armour protection and machinery spaces and ammunition magazine protected by 12-inch also. Masts or sails were completely dispensed of, a pretty radical idea at the time. The two steam engines were to provide a minimum of 12-knot speed, but rather than an oceanic vessel, the admiralty later wanted more of a coastal defence ship, and demanded a very low freeboard, 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres).

Reed also had to take in account reports and requirements from the special committee set up to determine battleship seaworthiness after the disaster of HMS Captain. The freeboard was increased to 10 feet 9 inches (3.28 metres) and breastwork lenghtened with an unarmoured structure to make it lighter. Two large models were tested, one 9-foot-long (2.7 m) in a water tank and another, 12 feets, at sea. Many further tests were performed on armour, structure, hull shape, and engines. In the end both ships were ordered at Portsmouth and Pembroke, laid down in 1869. As built they had four12 inch RML of 35 tons Mk I naval gun on sliding carriages while her sister ship experimented with two 12 inch RML of 35 tons Mk I naval gun on sliding carriages and two 12.5 inch RML of 38 tons Mk I or II naval gun Bored to 12 inches instead.

They were both Rebuild in 1890-92, rearmed with four 10-inch 32 calibre (25.4 cm) breech-loading naval guns mounted in twin Mark II Turrets, six 6-pounder 8-hundredweight or 2.244″ 40 calibre (57 mm) quick-fire Mark I naval gun on Mark I* low-angle single mounts, eight Hotchkiss 3-pounder 1.85″ 40 calibre (47 mm) quick-fire Mark I naval gun on twelve Mark I* low-angle single mounts, five or seven Nordenfelt multi-barrel guns on pedestal mounts, two Gardner light machine guns and two submerged Whitehead 14-inch (36 cm) torpedo tubes. They were discarded in 1905-1907 and scrapped by 1909.

HMS Dreadnought (i) 1875:

This ship was an improvement over the very successful Devastation class, built five years after. Construction was halted and she was redesigned as it was found both stability and buoyancy were problematic. Completion indeed was in 1879, but she was in reserve and re-commissioned in 1884, sent to the Mediterranean Fleet before starting a new career in 1894 as a coast guard ship in Ireland, depot ship, second-class battleship (1900), training ship, stricken in 1905, sold for scrap in 1908 just as her new generation namesake was making history in 1906.

Admiral class 1882 – First barbette battleships:

Collingwood, Anson, Camperdown, Howe, Rodney, Benbow

Six low freeboard barbettes ironclads with a compound engine, all named after admirals, built 1880-1888. They followed the Devastation class, with the main armament centreline, fore and aft of the superstructure. They were given Coal-fired steam engines, and a compound steam engine rated for 7,500 ihp (5,590 kW) and up to 9,600–11,500 on forced draught, for a top speed of 16 knots as contracted, 17.5 knots on trials.

They were armed wit four BL 12-inch (305 mm) guns (2×2), six BL 6-inch (152 mm) /26 guns, twelve 6-pounder (57 mm) guns, eight 3-pounder (47 mm) guns and four 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes and were protected by an armoured belt 18–8 in (457–203 mm) thick, with Bulkheads 16–7 in (406–178 mm) thick, Barbettes 11.5–10 in (292–254 mm) thick, while the conning Tower had 12–2 in (305–51 mm) walls and the armoured deck was 3–2 in (76–51 mm) in thickness. They were all sold for scrap before 1912.

Last Coles turret ships – Victoria class (1887)

These first class battleships used triple expansion steam engines for the first time instead of compound engines.

They displaced 11,020 tons (11,200 t), for 340 ft (100 m) x 70 ft (21 m) x 29 ft (8.8 m), and were propelled by Coal-fired triple-expansion steam engines; twin propellers for a top speed of 16.75 knots (31.02 km/h). outside their two single BL 16.25-inch (413 mm) guns in Coles Barbettes, they had a single BL 10-inch (254 mm) gun, 12 × BL 6-inch (152 mm), 12 × 6-pounder (2.7 kg) guns and 6 × 14 inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes. Their armor ranged from 76 mm for the deck to 18 in (457 mm) for the belt.

HMS Victoria was sunk in a a famous accidental collision with another batleship uring an exercise in the Mediterranean, with a great loss of life. HMS Sans Pareil was scrapped in April 1907.

Trafalgar class (1887):

Designed by famous engineer William Henry White, the Trafalgar and Aboukir and improved versions of the Admiral class, with a greater displacement and improved protection. They had however a partial belt with higher thickness.

Their secondary armament of eight 5 inch guns was changed to six QF 4.7 inch guns better suited against torpedo boats, and carried more ammunition. In the end, they were 600 tons overweight, augmenting of a foot the draft. They were the penultimate low-freeboard battleships of the Royal Navy. The smaller, lower hull presented a smaller target, and allowed thicker armour. But these hips were problematic in very rough seas, and for this they spent their career in the Mediterranean.

British modern battleships (1891-95)

In this section we are peering into the meaty part of “modern” British battleships. Arguably the Royal Sovereign class were a wake up call for all navies around the world. Not only this barbette battleships were the largest worldwide, but it was also the fastest, best protected and best armed.

All the following ships were discarded before of in 1914, they saw no active service during WW1, but for menial duties.

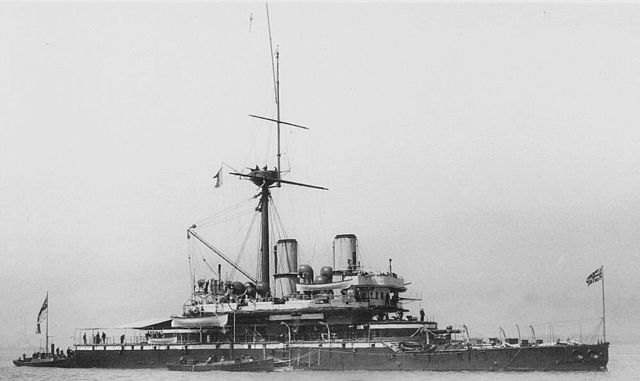

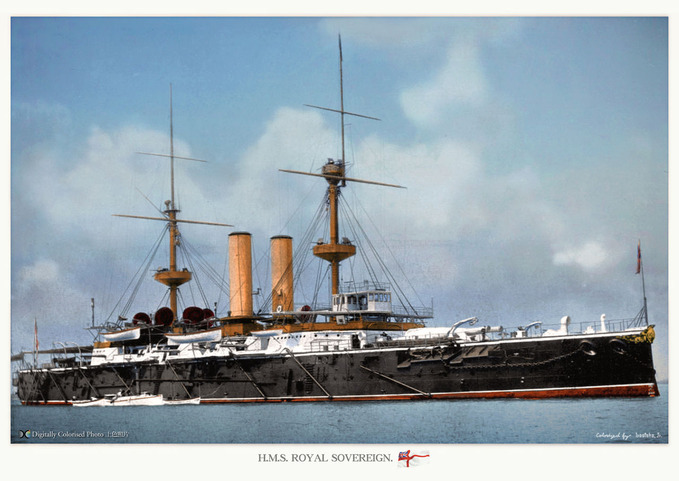

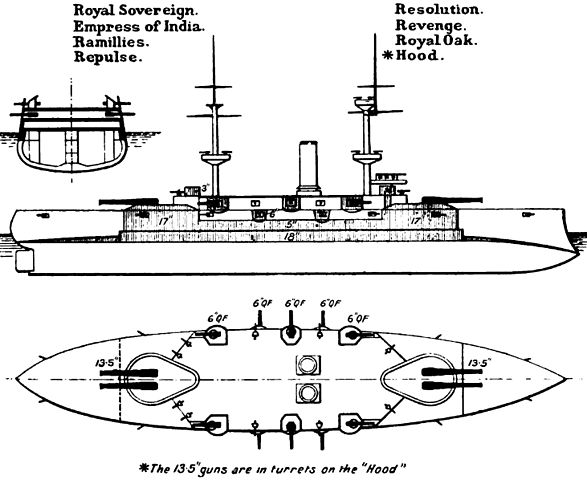

Royal Sovereign class (1891)

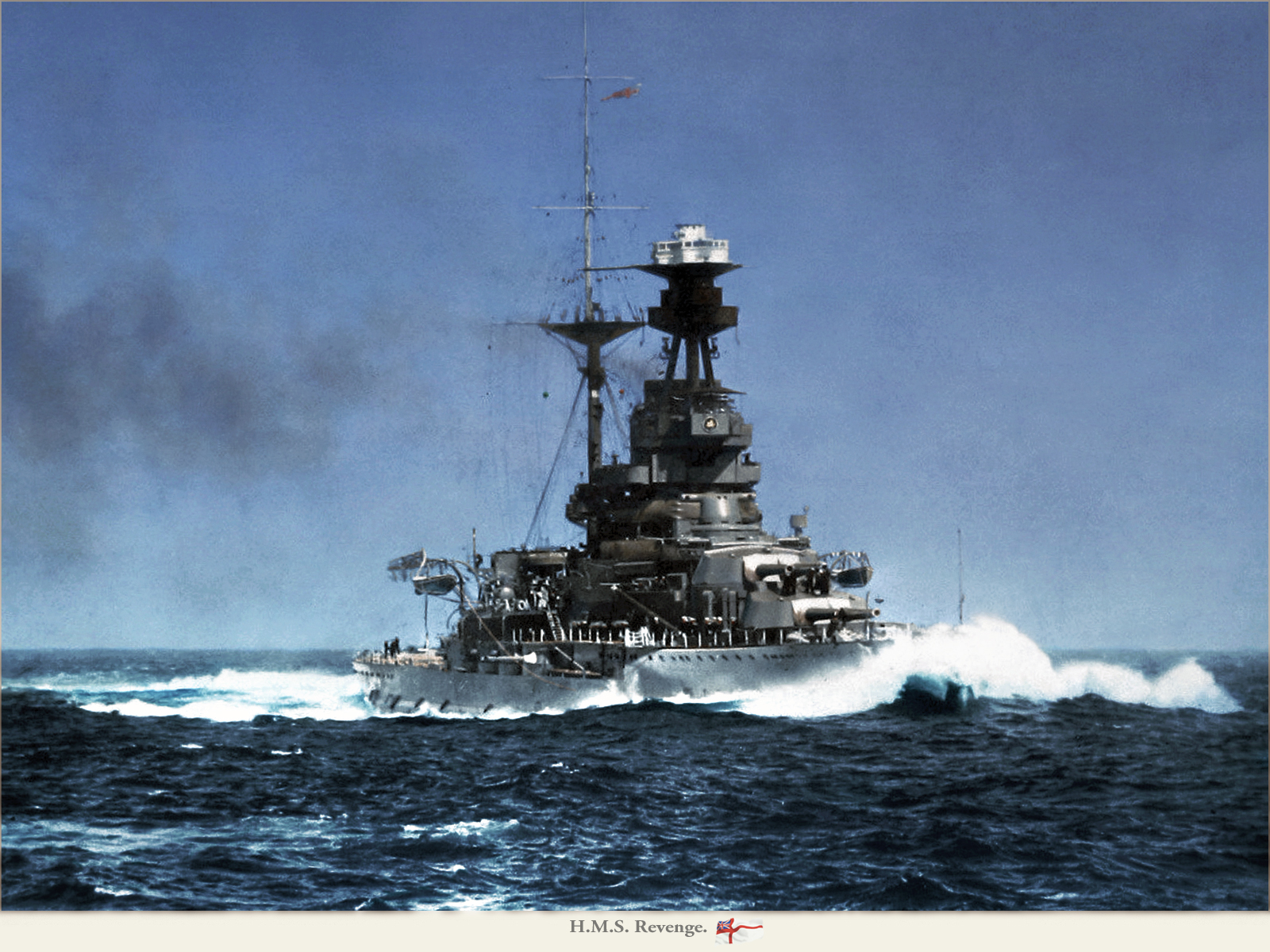

Royal Sovereign, Empress of India, Repulse, Hood, Ramillies, Resolution, Revenge, Royal Oak

This group of eight pre-dreadnought battleships of the 1890s spent their careers in the Mediterranean, Home fleet and Channel Fleet. Some were part of the Flying Squadron in 1896 due to tensions with the German Empire after the Jameson Raid in South Africa (and France at Fachoda). However around 1905–1907 at the time HMS Dreadnought marked a new league, they were rightfully considered obsolete and joined the reserve. The first were sold for scrap in 1911, HMS Empress of India being sunk as target in 1913. HMS Revenge was the only one to survive and see active service, patrolling and shelling the Belgian coastline. To free her name, she was renamed HMS Redoubtable in 1915 and hulked at the end of the year, becoming an accommodation ship, and sold for scrap in 1919.

HMS Redoubtable in 1915, shelling the Belgian coast. She was the most ancient commissioned British Battleship of WW1.

HMS Hood (1891)

Very similar to the Royal Sovereign, in fact it’s considered by some historians as one of these ships. HMS Hood was the first battleships fitted experimentally with anti-torpedo bulges to evaluate underwater protection in 1911. It ended as a blockship before August 1914.

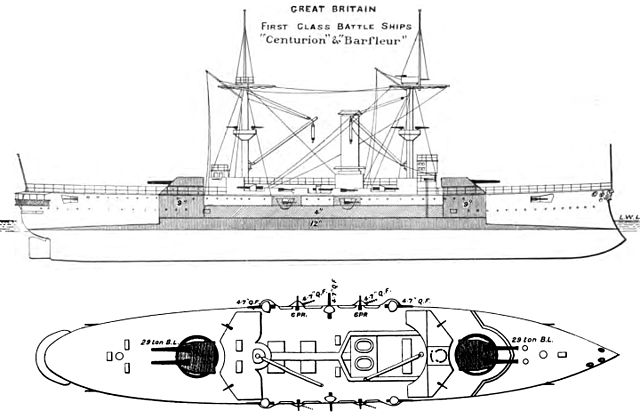

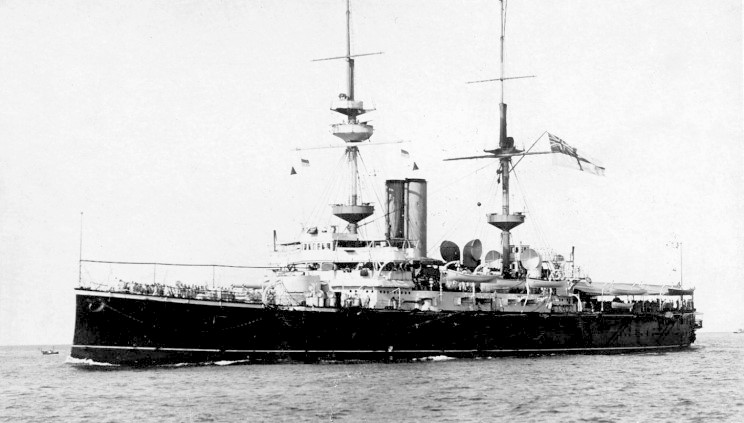

Centurion class 2nd class (1892)

HMS Centurion, Barfleur

These were two experimental second-class battleships, less heavily armed and armoured and designed for service abroad, with higher speed and longer range. Their priority targets were the armoured cruisers but they could also perform as commerce raiders. They originated on the Naval Defence Act 1889, and were designed by William White, Director of Naval Construction, as flagships for the eastern and Pacific Stations, only dealing with cruisers there. At that time, the probable enemy were Russian large armoured crusiers, armed with 10-in and 8-inch guns and protect British merchant shipping. The Admiralty wanted 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph) plus a draught limited to 26 feet (7.9 m) for the Suez Canal and Chinese rivers, no more like the armoured cruiser HMS Imperieuse.

Also they wanted them on budget, 30% less than first-class battleship. White designed a roughmy scaled-down Royal Sovereign with lesser beam, 10-inch (254 mm) main artillery and and 4.7-inch (120 mm) secondaries instead of the 13.5-inch (343 mm)/6-inch (152 mm) of regular battleships. Centurion and Barfleur were laid down at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth and Chatham for 533-540,000 pounds.

They displaced 10,634 long tons (10,805 t) and measured 390 ft 9 in (119.1 m) by 70 ft (21.3 m) and 25 ft 8 in (7.82 m) draught, propelled by two shafts VTE, 9,000 shp (6,700 kW), fed by 8 Cylindrical boilers for a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph), more than expected, but a range of 5,230 nmi (9,690 km; 6,020 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). ouside the main and secondary artillery they were given eight single 6-pdr (2.2 in (57 mm)) and twelve single 3-pdr (1.9 in (47 mm)) guns to deal with torpedo boats plus seven 18 in (450 mm) torpedo tubes.

For protection they counted on a 9–12 in (229–305 mm) thick belt, 8 in (203 mm) bulkheads, 2–2.5 in (51–64 mm) decks, a 12 in (305 mm) thick walls CT, Barbettes 5–9 in (127–229 mm) thick, gunhouses 6 in (152 mm) and casemates 2–4 in (51–102 mm) in thickness. They were commissioned in February and June 1894 and served until 1905, sold in 1909. They did not fought in the Great war.

HMS Renown 2nd class (1895)

Often assimilated with the previous class, HMS Renown was the result of reflection on main artillery. Production of a new 12-inch gun indeed was behind schedule and the three battleships planned for the 1892 Naval Programme were delayed. The admiralty asked for an improved Centurion-class to keep Pembroke Dockyard busy and workers happy. There was no formal requirement but advice from the Controller of the Navy, Rear Admiral John A. “Jacky” Fisher. The other influence came from the Director of Naval Intelligence, Captain Cyprian Bridge, pressing for additional ships of this type as substitutes. It was rejected by the Admiralty as not based on any requirement, but the Director of Naval Construction, William Henry White, submitted designs in April 1892, and the smallest was chosen, innovative as the first to use Harvey armour and with armoured secondary casemates, first with sloping armour deck or with armoured shields for the main armament.

built at Bembroke for £751,206 (much more than the Centurion), Renown was laid down on 1 February 1893, launched on 8 May 1895 and completed by January 1897, but decommissioned on 31 January 1913, she woould not see combat in WW1. She was nicknamed the “The Battleship Yacht” in part due to its luxuriously fitted interiors, with precious exotic woods and cooling arrangements.

She displaced 12,865 long tons deeply loaded, was 412 ft 3 in (125.7 m) long overall for 72 ft 4 in (22.0 m) and 27 ft 3 in (8.3 m) of draft deeply loaded. She was propelled by 3 shafts VTE fed by 8 cyl. boilers rated for 10,000 ihp (7,500 kW), enough for 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph), a good performance for a battleship. Her range was also much better than the Centurion at 8,500 nmi (15,700 km; 9,800 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) but she was way too costly for a “second rate”, courtesy of Fisher.

In addition to four BL 10-inch (254 mm) and ten QF 6-inch (152 mm) Mk II guns, renown was armed with twelve QF 12-pounder guns and twelve QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns plus fve 18-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes. Her Belt was 6–8 in (152–203 mm) thick, Deck 2–3 in (51–76 mm), Barbettes 10 in (254 mm), Gun turrets 3–6 in (76–152 mm), Conning tower 3–9 in (76–229 mm) and Bulkheads 6–10 in (152–254 mm)

British Pre-dreadnoughts of WW1

From this section, all the battleships presented were active in WW1, in some form or another. Indeed, some were in reserve, other used as training ships or depot ships, ans some were reactivated due to the numerous tasks found for them. Since this was a world war and dreadnoughts and battlecruisers were kept in the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow to face any sortie of the mighty Hochseeflotte, British pre-dreadnought had to care for all other theaters of operation, starting with the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean and Pacific. For example, HMS Albion was detached at the Falklands. Pre-dreadnoughts in 1914 represented a considerable force of 50 battleships, way above many navies of the time, and they still possessed 12-in guns and a substantial secondary battery for any operations. But their limitations were well understood. Their poor speed made them unable to match the new admiralty standards of the Grand fleet, while their limited ASW protection (or total lack thereof) made them easy targets for submarines. More than these old battleships, the admiralty was more weary of loosing experienced crews in times of war.

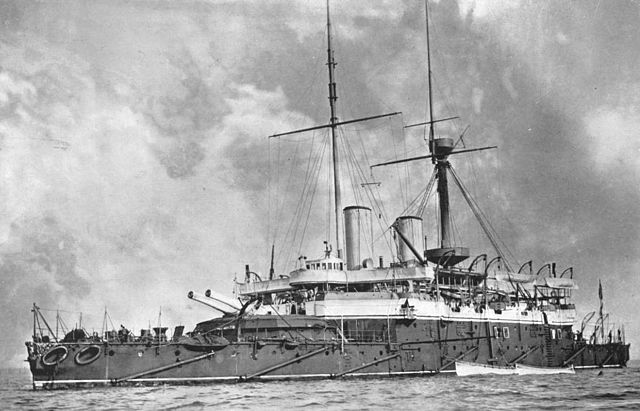

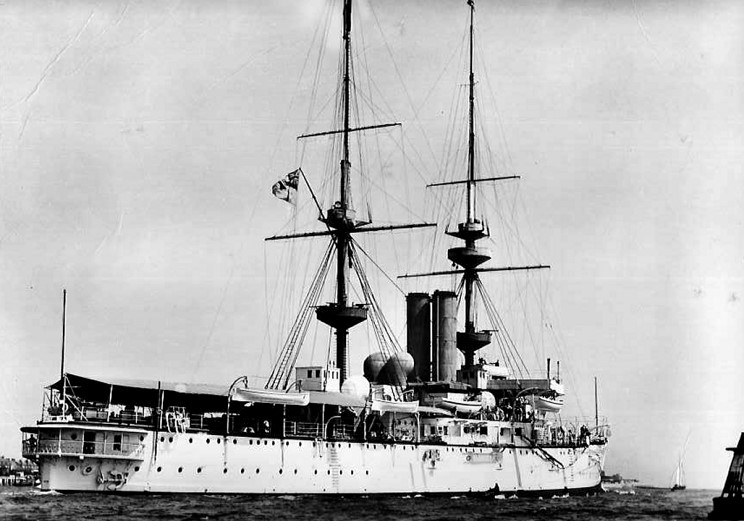

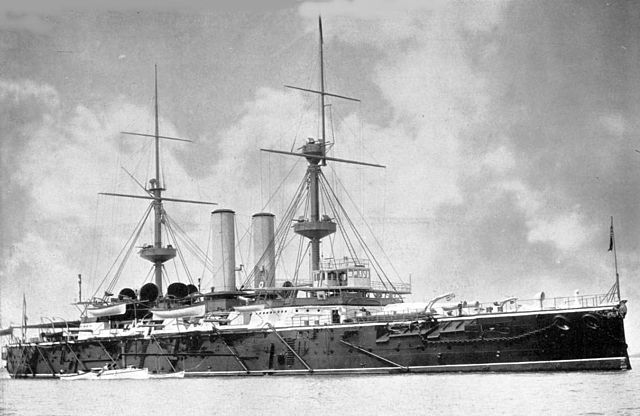

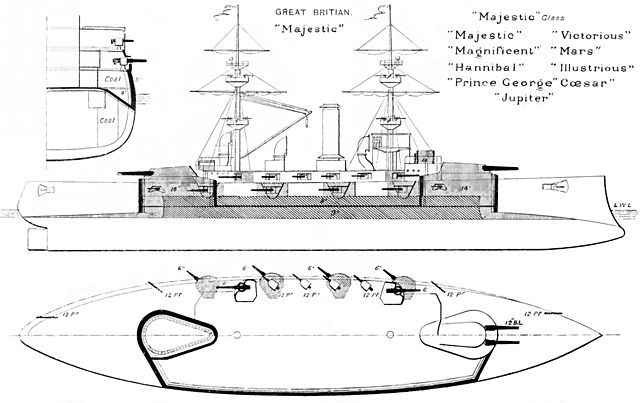

Majestic class (1895)

Majestic, Caesar, Hannibal, Illustrious, Jupiter, Magnificient, Mars, Prince George, victorious

HMS Mars

When they entered service in 1895, HMS Majestic and Magnificent were the largest battleships ever built. From the program developed by Mr. Spencer in 1893, they combined the Royal Sovereign base with the progress recorded on the second class battleship HMS Renown. The new 305 mm Mk VIII guns were faster to load and had a greater range than the previous old 343 mm, while allowing to save weight, used to increase the light artillery.

They were adopted for all subsequent British battleships for almost 30 years. The vertical armor was made of Harvey steel, like on the Renown. The combined belts were of the same thickness everywhere and the guns had barbettes and were protected by integral turrets. Also was moved back the bridge, fixed around the forward military mast, a configuration which increased forward vision from the command tower and its protection against a possible fall from the mast. The barbettes of the first 2 vessels had a fixed loading system, and necessitated having to replace them in position for loading.

Seaworthy and stable ships, only showing a slight roll, these battleships quickly formed the basis of a long line of capital ships imitated around the world and formed the bulk of the Grand Fleet for years. With the appearance of fuel oil in 1905, HMS Mars was provided with an oil reserve of 400 tonnes, replacing 200 tonnes of coal, but with a certain benefit for autonomy, followed in 1908 by the other ships.

With their VTE and coal-burning boilers alone, all exceeded their expected speeds, even reaching 17.6 to 18.7 knots with forced draught. But in operation this oscillated between 16 and 17 knots. They spend their entire career in the Home Fleet before the war, except for HMS Victorious and Caesar which made two stays in the Mediterranean and Far East stations.

–HMS Caesar

In 1914, officiated in the Home Fleet (Channel’s 7th BB squadron), then left to North America to carry out patrols in the Atlantic until 1918. She then went to the Mediterranean, passed the Dardanelles after the armistice and came to support the “whites” in the Black Sea.

–HMS Hannibal was used as a coast guard and then disarmed in 1914 for the benefit of monitors Prince Eugene and Sir John Moore. Converted into a troop carrier, it served from 1915 in the Mediterranean, then in the East Indies and Alexandria until 1919.

–HMS Illustrious served as coast guard in 1914, based on Loch Ewe, Lough Swilly, Tyne and Humber, and in 1915 she was decommissioned and converted to an ammunition carrier based in Portsmouth.

–HMS Jupiter was in 1914 based in the 7th line squadron which kept the channel. She then opened the route for a convoy as icebreaker towards Arkhangelsk, with a record: The first ship arrived so early in the year – January. She then operated back in the English Channel, then in the Mediterranean, Alexandria, Red Sea and the West Indies until 1919.

–HMS Majestic was at 7 LS in 1914. She also served in the North Atlantic as an escort in 1915, then joined the “Dover patrol”, shelling the Belgian coast. She then served in the Dardanelles, hammering the sea with her cannons to blow up mines. While carrying out a bombardment to support troops, she was it by 2 torpedoes crosswise from U21 off Gaba Tepe and capsized on May 27, 1915, bringing 40 men with her.

–HMS Magnificient served with the 9th line squadron based on the Humber in 1914. She was then assigned to Scapa Flow as coastguard and then sent in 1915 to Belfast to be disarmed for the benefit of the monitors HMS General Crawfurd and Prince Eugene. She was then sent to the Dardanelles as a troop transport, notably to Suvla Bay. She then returned to mainland France as a utility pontoon. In 1918 she was stationed at Rosyth as a floating ammunition depot.

–HMS Mars served as coast guard on the Humber in 1914. She then joined the harland & Wolff shipyard (Belfast, the builders of the Titanic) to be disarmed for the benefit of monitors HMS Earl of Petersborough and Sir Thomas Picton. She then served as a troop transport in the Mediterranean, participating in landing operations of the ANZACs at the Dardanelles and at the evacuation at Cap Helles in 1916. She was then converted into a supply ship at Invergordon.

–HMS Prince Georges suffered a serious manoeuver collision with the armored cruiser hms Shannon in 1909. In 1914 she served with the 7th Line Sqn on the English Channel. She was then sent to the Dardanelles to clean up minefields with her artillery, and then shell Turkish forts. She was hit several times, quite seriously, and joined Malta for long repairs. She participated in the evacuations in January 1916 at Cape Helles, and was hit by a torpedo (a dud). At the end of 1916 she was based in Chatham, served as a utility pontoon, and in June 1918 renamed Victorious II. Removed from the lists in 1921, she sank during her transfer for demolition to Germany.

–HMS Victorious served as coast guard on the Humber in 1914. In February 1915, she was sent to the Elwick shipyards to be disarmed for the benefit of monitors Prince Rupert and General Wolfe. From May 1916 she served as a workshop ship and was based at Scapa Flow until 1919.

Author’s illustration of the Majestic class

Technical specifications

Displacement: 14,600 – 14,800 t, 15,730 – 16,000 t FL

Dimensions: 124.3 x 22.8 x 8.2 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts 3-cylinder VTE, 8 boilers, 10-12,000 hp. 16-17 knots max.

Armor: Blockhouse 343, belt 220, internal bulkheads 343, turrets 254, barbettes 343, bridges 102 mm.

Armament: 4 x 305, 12 x 152, 16 x 76, 12 x 47, 5 x 457 mm TTs.

Crew: 672

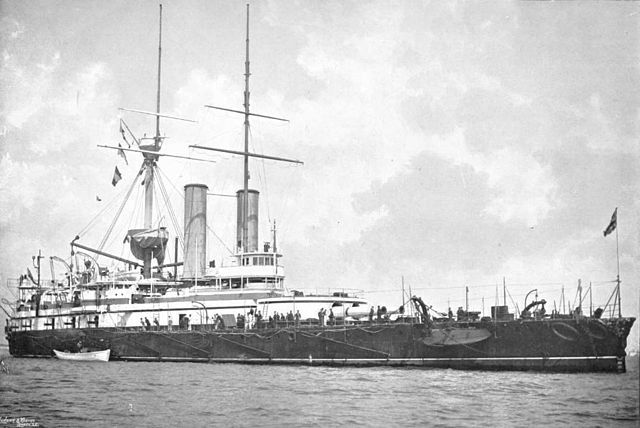

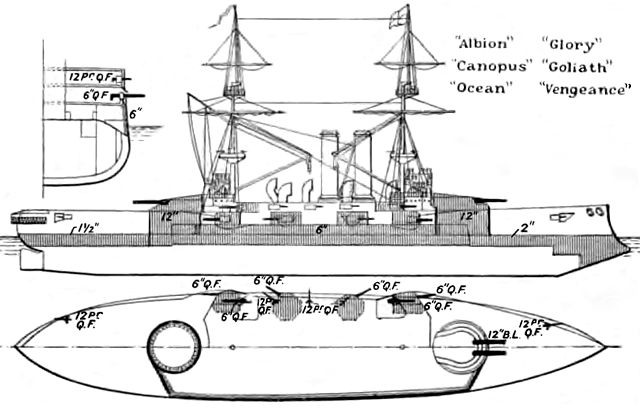

Canopus class (1897)

Canopus, Albion, Glory, Goliath, Ocean, vengeance.

Five ships of a new class of battleships were ordered in the 1896 naval plan. A sixth was in the 1897 plan. They were defined as faster versions of the Majestic, and at the same time to operate in the Far East, to counterweight especially the growing weight of the Russian and Japanese Navies (this was befoe the anglo-japanese naval alliance). A true quadrature of the circle was also carried out, by reducing the thickness of the armor and the total weight by 2000 tonnes, by using Krupp steel rather than Harvey. Their armor and artillery layout remained modelled on those of the Majestic.

Their “turrets” were in fact relatively light barbettes composed of Krupp steel plates. But they innovated with their loading system allowing to operate wit the guns left at all angles. They were also the first British battleships to have water tube boilers. The latter, Belleville models were hardly heavier than the old ones but pressure was now at 300 bars, versus 155.

The layout of these new boilers also meant that they were placed in tandem and not side by side, a layout later kept for future battleships.

On trials, their powerplant reached 13,500 hp and the speed reached, 18.5 knots. As expected, their careers began with a long sojourn in the Far Eastern squadron, which ended after the Japanese victory over Russia in 1905 and a cautious military alliance with the Japanese Empire. As a result, freed from this threat, the British repatriated a number of vessels, including these battleships into the Home Fleet, to counter the growing threat from the Hochseeflotte.

–HMS Albion was active until 1906 in the grand fleet, before having an overhaul in Chatham in 1907. She was assigned to the Home Fleet in Portsmouth, and to Atlantic fleet. During the Great War, she was sent to South Africa. She was assigned to the Mediterranean, shelling the Turk forts at the Dardanelles. She was hit in return and after repairs, carried troops to Salonika. Finally, she was stationed as coastguard of the Southeast fleet from the fall of 1915 until 1918. She was then assigned to Devonport, decommissioned and used as an armed utility pontoon until 1922.

–HMS Canopus served in the Mediterranean, French coast and channel, before moving to Port Stanley in the Falklands at the end of 1914. She could not take part in the Cradock fleet defeated by Von Spee’s squadron, but her guns fired later against approaching German cruisers without results. She then joined the Dardanelles, blockaded Smyrna, and returned in 1916 to Chatham, placed in reserve, and sold in 1920.

–HMS Glory was operating off North America, and East Indies as a flagship. She then operated in the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean, defending the Suez Canal. She then joined Archangelsk and remained there as coastguard until 1919 before sale and demolition.

-HMS Goliath was in Scotland in 1914. It covered troops landings in Belgium (Ostend), served in the East Indies, and in November 1914 it was on the Rufiji River in Africa, taking care of the Königsberg. She was sent in 1915 to the Dardanelles, supporting operations at Cape Helles, and hit twice. In the night of May 13, she was torpedoed and sunk by the Turkish destroyer Muavenet, sinking quickly, carrying with her 570 men.

-HMS Ocean was based in the Mediterranean, in the Home Fleet and was in Pembroke when the war broke up for a refit. She was sent to Queenstown, Jamaica, and the East Indies. In November, she was stationed in the Persian Gulf, served in the Mediterranean, and fought in the Dardanelles from February to March 1915. By march 18, she struck a mine which destroyed her powerplant. She drifted under large Turkish caliber range and sank in three hours, leaving almost all of its surviving crew to evacuate.

-HMS Vengeance served in the English Channel, and the Home Fleet. Unlucky during her career, she collided with a freighter, and ran aground in the Thames, colliding with the destroyer Biter in 1910. In 1914 she served as a training ship for gunners. She then served in the Atlantic with the 8th line BS and in November 1914, was supporting operations in Cameroon, a German colony. She was sent to Egypt (Suez canal), and to Cape Verde. She was Admiral De Robeck’s flagship at Gibraltar, departing to the Dardanelles. She shelled forts at Cape Helles, covered the landings, before returning to Egypt. She was sent to the East Indies, then back to Egypt and operated on the East African coast and later in South Africa. In 1917 she returned to Devonport and was rearmed, kept there as an orderly state, struck off the lists in 1919, and BU in 1921.

Author’s illustration of the Canopus class

Technical specifications

Displacement: 13 150t, 14 300 T FL

Dimensions: 128.47 x 22.56 x 7.98 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts VTE, 20 Belleville boilers, 13,500hp. 18 knots.

Armour: Belt 152, Battery 254, Barbettes 305, turrets 203, CT 152, decks 51 mm.

Armament: 4 x 305, 12 x 152, 10 x 76, 6 x 47, 4 x 457 mm TT (sub).

Crew: 682

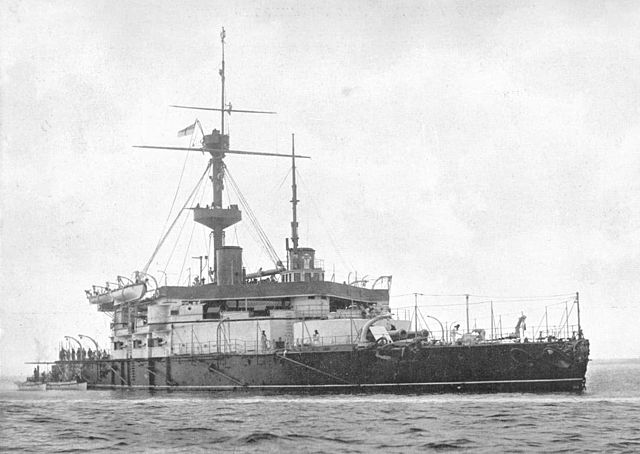

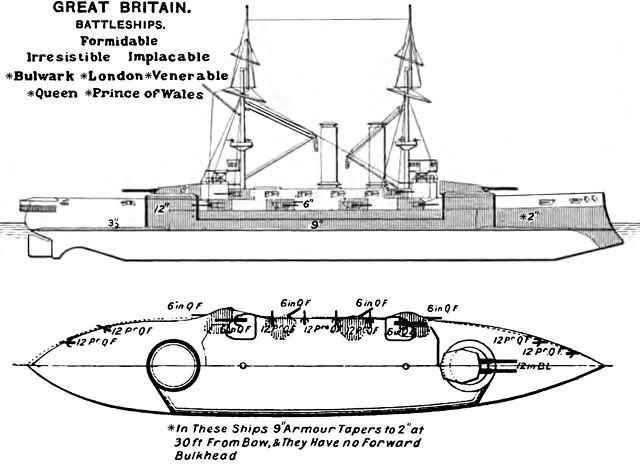

Formidable class (1898)

Formidable, Irresistible, Impacable.

These were a three-ship class designed by Sir William White armed with the usual battery of four 12-inch (305 mm) guns, top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). They definitely adopted the lighter Krupp armour in British battleship designs. This class formed the basis for the nearly identical London class and they are sometimes included in the larger Formidable class. They were built between 1898 and 1901 at the Portsmouth, Chatham, and Devonport Dockyards.

They served in the Mediterranean Fleet early in their careers, and served in the Home Fleet and Channel Fleet in 1914, then Atlantic Fleet. By 1912, they served with the 5th Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet until August 1914, patrolling the English Channel, escorting troopships with the British Expeditionary Force.

On the night of 31 December 1914 to 1 January 1915 while on patrol in the Channel, the 5th Squadron was crossed by a German U-boat which torpedoed and sank HMS Formidable.

-hms Irresistible was sent to the Dardanelles in February 1915. She shelled forst but later struck a naval mine and sank, one of the famous minefield left by the converted tug Nusret, the “battleship killer”.

-hms Implacable joined the Dardanelles in March 1915 and covered landings at Cape Helles in April 1915. She was withdrawn in May 1915 to reinforce the Italian fleet (Adriatic) and covered operations at Salonika in November 1915. She was back home in July 1917, converted into a depot ship, Northern Patrol. She was sold for scrap in 1921, BU in 1922.

Technical specifications

Displacement: 14,500 t, 15,900 t FL

Dimensions: 131.6 x 22.9 x 8 m (431 ft 9 in x 75 ft x 26 ft)

Propulsion: 2 shafts 3-cylinder VTE, 20 Belleville WT boilers, 15,000 hp. 18 knots.

Armor: 330 CT, belt 230, citadel 305, turrets 280, casemates 152, 60 mm decks.

Armament: 4 x 305, 12 x 152, 16 x 76, 6 x 47, 4 x 457 mm TTs.

Crew: 714

London class (1899)

London, Bulwark, Venerable, Prince of Wales, Queen

These 6 battleships were very close to the Formidable, varying only in armor details. The forward protection was lowered in favor of the belt armored reinforced and shortened aft. On the other hand, the thickness of the main deck was increased over the entire length of the ship, but intermediate decks armor was reduced. The ships differed significantly between them: HMS Queen and Prince of Wales had an open battery for their 3-in guns unlike the others. In addition, boilers of the same HMS Queen were Babcock and Wilcox, not Belleville. They were operational in 1902-1904. Their careers were first carried out in the Mediterranean, then these 6 ships returned to territorial waters.

–HMS Bulwark operated as part of 5th BS Sqn patrolling the English Channel in 1914. In November 26, when unloading ammunition a load of black powder exploded, the bunkers ignited and exploding in turn. The ship was literally disintegrated, there were only survivors.

–-HMS London was assigned to 5th BS Sqn and conducted seaplane launch tests. In 1914 she patrolled the Channel but was sent to the Dardanelles and in May 1915 was in the Adriatic multinational fleet supporting the Italians. She remained in Taranto until the end of 1917, when she became a minelayer. In January 1918 she served there until the armistice.

–HMS Venerable served with the 5th Sqn until 2015, shelled the Belgian coast. She relieved HMS Queen Elisabeth in the Dardanelles and from 14 to 21 she participated in the Suvla operation. She rallied the Adriatic, supporting Italian troops and returned in 1918 to UK before being setn in reserve and BU.

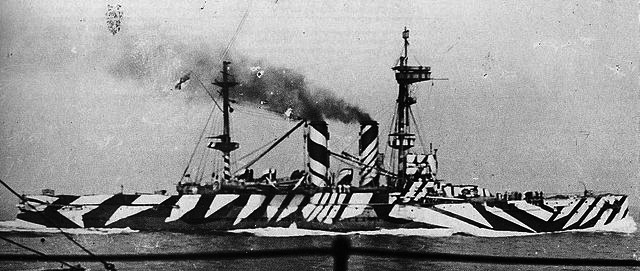

HMS London used as a minelayer in 1918, camouflaged

-HMS Prince of Wales patrolled the English Channel with the 5th BS Sqn, then joined the Dardanelles in 1915. She supported ANZAC landings on April 25 and in May she was sent to the Adriatic, until early 1918. On her return to mainland France, she was reduced to harbor service at anchor, like her companions.

-HMS Queen was assigned to the 3rd BS Sqn, 1st Fleet in 1914. She served in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. After patrolling the English Channel, she was like the Prince of Wales sent to the Dardanelles, covering ANZAC landings. She then was assigned to the Adriatic fleet, waiting for any sortie of the Austro-Hungarians. In Taranto, four of her 6-in guns were removed and transferred to the Italian navy. She then returned to UK, served as atraining vessel before being demobilised, placed in reserve in 1918 then sold.

Author’s illustration of the London class

Technical specifications

Displacement: 14,500 t, 15,400-15,700 t FL

Dimensions: 131.6 x 22.9 x 7.9 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts 3-cylinder VTE, 20 Belleville boilers, 15,000 hp. 18 knots.

Armor: 330 CT, belt 230, citadel 305, turrets 280, casemates 152, 60 mm bridges.

Armament: 4 x 305, 12 x 152, 16 x 76, 6 x 47, 4 x 457 mm TTs.

Crew: 714

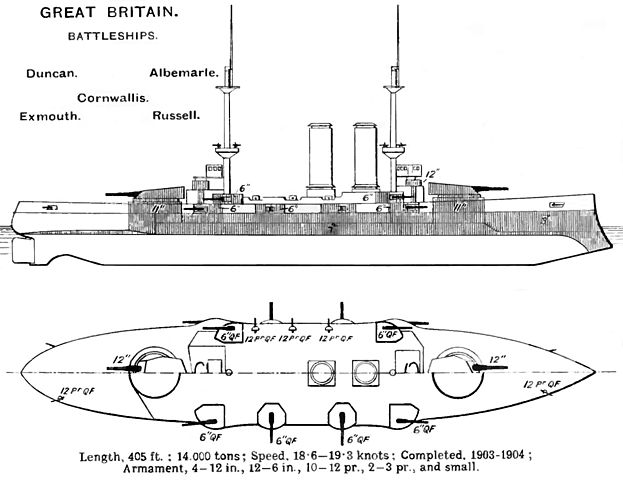

Duncan class (1901)

Duncan, Ablemarle, Cornwallis, Exmouth, Montagu, Russel

The six Duncan class battleships were ordered in response to Russian Peresvet-class battleships planned for the far east. The British admiralty falsely believed they were capable of 19 knots so the Director of Naval Construction William Henry White was ordered to work on a suitable answer. She submitted it by February 1898, but the Board of Admiralty thought many revisions would be necessary, so in emergency they asked for a modified Formidable class, incorporating some aspects of White’s design: They would have been given a revised armour protection layout, and the heavy transverse bulkhead were dropped, instead side armour was lengthened to the stern, and at reduced thickness, giving the London-class battleships. White’s revised version came out on 14 June 1898 and she chose to make the ships 1,000 tonnes (980 long tons) lighter.

Ordered in 1898, the Duncan class were revised Formidable, smaller and faster, sacrificing size and armor, arranged as on the London class. The four-cylinder VTE were to provide 3000 hp more than the Formidable class, and the hull shapes revised for better top speed, 19 knots being the lowest estimation as requested. They passed their sea trials while reaching all 19 knots, HMS Cornwallis 19, 56 knots, served in the Mediterranean and the Home Fleet.

-HMS Ablemarle served in the firth of forth, Atlantic, and was based in Gibraltar. She then returned to Portsmouth in 1910 and was assigned to the Northern Patrol, with the Grand Fleet in 1914. She then operated on channel with the 6th BS Sqn. While carrying heavy loads of ammunition she was badly damaged during a storm at the Pentland Firth, Scotland. After repairs, she departed Scapa Flow for Arkhangelsk, to serve an an icebreaker for convoys to Russia. In May 1916, she returned home, was partially disarmed and stayed in reserved by 1917 in Devonport, BU in 1919.

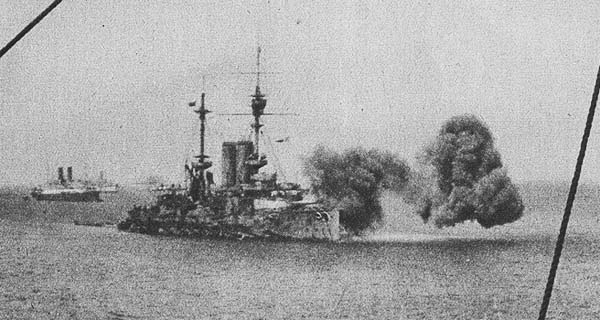

-HMS Cornwallis served in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and Home Fleet with the 4th BS Sqn. She was transferred to the 6th in 1914, patrolling the North Atlantic, then she was sent to the Dardanelles, the first entente ship to fire on the Turkish Ottomon fortifications. She covered all operations until the end. In 1917 she was operating from Malta when she was hit by three torpedoes launched by U 32 but sank slowly, only 7 men were lost.

-HMS Duncan served in the English Channel, the Atlantic, before running aground on a reef in an attempt to save the shattered HMS Montagu. Repaired, she was based in the Atlantic again, then joined the Mediterranean, served there for a long time before joining the Home Fleet in 1912 with the 4th BSSqn, 1st fleet. In 1914 she operated in the North Sea, then was based in Dover after Portland. She was then sent to the Dardanelles but little employed. She returned in 1917 and was placed in reserve to release seamen available for other ships, and BU in 1920.

-HMS Exmouth was the flagship of the Home Fleet in the Channel at Portsmouth in 1906, before becoming the flagship of the Atlantic fleet. In 1908 she was the flagship of the Mediterranean fleet at Gibraltar. She then returned to the Home Fleet, bearing the mark of the rear admiral, 4th Wing. She was then assigned to the gunners instruction in devonport, before returning to the 6th line squadron at the start of hostilities. She went on patrol trips to the North Sea before coming to Portland and joining the Channel fleet.

She bombarded the Belgian coast in May and November 1915, and was sent to operate at the Dardanelles. She became Nicholson’s flagship in front of Kefalonia, the only battleship available after the torpedoing of the other three. Her heavy protective nets affixed before her departure had much to do with it. She then returned to the reserve in 1917 and was BU in 1920.

-HMS Montagu had a very short career. Operating in the Channel in 1906, she had the misfortune of running aground on the rocky island off Lundy on May 30, 1906 in thick fog. Despite the assistance of several ships, including hr sister-ship Duncan who tried to tow her, but was herself grounded she was estimated non-salvageable as too damaged. Her artillery was recovered and the hull was BU on site in 1907.

-HMS Russel the last of these 6 battleships, served as her sister-ships in the channel, then Atlantic fleet, then Gibraltar. In 1912 she was back in the Home Fleet, and in 1914 joined the English Channel fleet in Portland. She participated in the shelling of the Belgian coast and was sent in early 1915 to the Dardanelles. She remained on the second line in front of Mudros with HMS Hibernia, participating in the evacuation in January 1916. She hit a mine off Malta on April 27, 1916 and sank with 126 crew members.

HMS Cornwalllis firing on Gallipoli, 1915

Technical specifications

Displacement: 13 150t, 14 300 T FL

Dimensions: 128.47 x 22.56 x 7.98 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts, three VTE, 20 Belleville boilers, 13,500hp. 18 knots.

Armor: Belt 152, Battery 254, Barbettes 305, turrets 203, blockhouse 152, bridges 51 mm.

Armament: 4 x 305, 12 x 152, 10 x 76, 6 x 47, 4 x 457 mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 682

King Edward class (1903)

HMS King Edward VII, Dominion, Africa, New Zealand, Britannia, Commonwealth, Hibernia, Hindustan

They were the penultimate British pre-dreadnoughts battleships and the last important class, with two sets of three ships and a pair. They were started in 1902-1904 and accepted in service in 1905-07, so even after HMS Dreadnought was launched. Their great innovation consisted in a wider beam and larger dimensions overall, making it possible to adopt a large intermediate caliber in the form of four additional 9.2 in (234 mm guns) in turrets. With this configuration the King Edward class approached the concept of single-caliber battleship then under study. The armour scheme was also revised to become a central battery arrangement, raising the lateral protection to the bridge.

The rest of the protection was modelled on that of the London class, with some modifications such as the belt separated into two overlapping plates of 220 to 203 mm. Their mixed guns were later criticized, in particular on the fact that the 234 mm secondary guns posed problems for rangefinder adjusters. The water plums provoked by the 12-in being almost similar to the 9-in and caused confusion.

Their machines differed from each other, but they were considered to be good walkers, achieving better speeds than expected, having good handling with a new helm system. On the contrary, this new system made them difficult to hold the line, and they were quickly ironically nicknamed “the eight stooges”. They also had a raised metacentric point and faster roll but remained good firing platforms. Their career was quite rich due to their powerful artillery and their relative modernity:

-HMS Africa served for a long time in the Home Fleet before leaving in 1913 for the Mediterranean. She then returned with the 3rd Line Wing to the Home Fleet and then joined Scapa Flow in 1916. In 1917 she underwent an overhaul, her 6-in guns from the battery deck being landed for the benefit of four more relocated on the upper deck to avoid spray in heavy weather. From April 1917 to November 1918 she was based with the 9th Line Wing before retired, struck in 1919 and BU.

King Edward VII’s side turret

-HMS Britannia also served with 3rd battleship squadron Gibraltar in 1913 before returning to the mainland. In January 1915 she struck a submerged reef (off Inchkeith, Scotland) during a storm by night and was badly damaged. Her repairs completed, (and rearmed like HMS Africa) she continued to serve in the North Sea and in the Channel before joining the Mediterranean. She was torpedoed at Cape Trafalgar by UB50 on November 9, 1918, one of the last major losses of the Royal Navy of the war. She sank in three quarters of an hour, letting her crew evacuate, but many died in toxic fumes caused by the massive fire.

-HMS Commonwealth suffered two accidents during her service. She left with the 3rd squadron in the Mediterranean in 1913 but underwent a short overhaul in December 1914-February 1915. The rest of her career took place in Scapa Flow, without note. She was disposed of at the beginning of 1918, repaired and completely rebuilt with tripod mast, new firing director, and ASW ballasts and from 1919 until 1921 served as a gunner’s training ship at Invergordon.

-HMS Dominion was also part of the 3rd squadron in the Mediterranean, and became the flagship of the rear admiral until 1915, then returned to the mainland and was torpedoed in front of the Thames estuary by an U-boat, which missed. She remained on site until 1918 and was sent in Chatham, until BU in 1921.

-HMS Hibernia had a quiet career in the home fleet. She was used for the first takeoff of an airplane on a British warship, on May 4, 1912. She was later equipped with a platform on the front turret. She was also the flagship of the 3rd squadron in Gibraltar and in August 1914 returned home. She was back to the Mediterranean in November 1915 at the Dardanelles as flagship of Admiral Fremantle. Later she was anchored off Kefalonia. In 1917, her armament was partly removed and she joined Scapa Flow, remaining there until the end of her career in 1921.

-HMS Hindustan also served in Gibraltar with the 3th BS Sqn before returning home, same unit. She was assigned to the North Sea until May 1916, then returned to Scapa Flow. She assisted as a supply vessel which participated in the Zeebrugge and Ostend raids in 1918.

-HMS King Edward VII performed the same service in the Mediterranean as her sister ships, then returned to the home fleet as flagship of 3th BS Sqn (Vice-Admiral Bradford). Dominion resumed her role. On January 6, 1916 she had the misfortune to hit a mine off Cape Wrath. Her two machines were quickly submerged but her watertight doors had played their role: She did not sink until 12 hours later, leaving the crew to evacuate.

-HMS New Zealand served in the Atlantic and the English Channel, and was renamed Zealandia in 1912 (as a battlecruiser took the name), joining the 3rd squadron in the Mediterranean in 1913. Returning home, she made a brief stay in the home fleet before departing again for the Mediterranean in November 1915, fighting in the Dardanelles. She was taken over in early 1918 for a reconstruction similar to HMS Commonwealth, but without ballasts. Partly disarmed, she was anchored in Portsmouth in 1919 and remained there until her demolition in 1921.

Author’s illustration of the KE VII class

Technical specifications

Displacement: 15,585 t, 17,290 t FL

Dimensions: 138.5 x 23.7 x 7.7 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts VTE machines 4 cyl., 15-16 mixed boilers, 18,000 hp. 18.5 knots.

Armor: CT 305, belt 230, citadel 305, turrets 305, battery 160, 60 mm decks.

Armament: 4 x 305, 4 x 234, 10 x 152, 14 x 76, 14 x 47, 4 x 457 mm TTs.

Crew: 777

Swiftsure class -2nd class (1903)

HMS Swiftsure, Triumph

HMS Swiftsure and Triumph were originally two battleships ordered by Chile, named Constitution and the Libertad. Export and finance oblige, they were designed by chief engineer of Armstrong-Elswick, Sir Edward Reed, like “budget” battleships. They were specifically ordered by the Chilean government to counter the latest Garibaldi class Argentinian cruisers. They were thus regarded as “second class battleships”.

Their pre-main armament rested on 10-in (254 mm) guns, and they had a powerful secondary battery comprising no less than fourteen 7.5-in (190 mm) guns and a singular tertiary battery also comprising 80 mm guns. They were comparatively lightly armored, had a long and narrow hull (conditioned by the largest Chilean Docks) and a speed higher than battleships of the time, managing 14,000 hp and and 20 knots. In theory, they could outperform any cruiser and thus were considered with mild interest by the Royal Navy.

In December 1903, when Swiftsure was launched and before her handover to the Chilean government, peculiar events stepped in. Rumors were spread over a covered sale, the Tsar being the real customer (Chile’s finances were bad at the time). The same scenario happened with the Minas Gerais class. The press and popular pressure forced the British government to seize them. When they were completed in June 1904, they were therefore both integrated into the Royal Navy under their new names.

The Chilean government retired any payment, including design study cost, if not for those of pre-order and the matter was closed. Not for the Royal Navy however for which these two “second class battleships”, as classified were not fitting any need. They would serve first in the channel, then in the Mediterranean until 1913. Swiftsure was sent to the East Indies, and Triumph in China.

In 1914 the Swiftsure was escorting convoys of Indian troopships from Bombay to Aden in the Red Sea. She joined the Alexandrian squadron, shelling Turkish positions at Kantara. She then went to the Dardanelles and supported the landings, pounding Turkish forts. She was torpedoed in September 1915 by an U-Boote, but survived and resume her escort mission of troopships during the retreat.

Back in 1917 to Chatham, she was disarmed in order to convert her as a blockship for occupied Belgian ports. The operation never took place and in 1918 she was used as a balloon depot ship. HMS Triumph, was in reserve in Hong Kong when the war started. She was quickly provided with a fresh crew issued from various gunboats, and joined a small composite squadron dominated by the Japanese who besieged Tsing Tao. In January 1915 she joined the Mediterranean squadron, and in February, was in the Dardanelles. In May, she was shelling Gaba Tepe’s positions when U21 torpedoed her and she sank in 30 minutes, with 73 casualties.

Author’s illustration of the Swiftsure class

Technical specifications

Displacement: 11,800 t, 11,985 T FL

Dimensions: 146.2 x 21.6 x 7.7 m

Propulsion: 2 shaft VTE, 3 cyl., 12 Yarrow boilers, 12,500 hp. 19 knots.

Armor: Belt 180, Battery 152, Barbettes 254, turrets 254, CT 280, decks 47 mm.

Armament: 4 x 254 (2×2), 14 x 190, 14 x 80, 2 x 76, 4 x 47, 2 x 457 mm TTs (sub)

Crew: 800

Lord Nelson class (1906):

British Semi-dreadnoughts ?

HMS Lord Nelson and the Agamemnon, started in 1905, were the last English pre-dreadnoughts battleships. Based on the King Edward VII, their tonnage had been increased to further increase their intermediate artillery made up of 234 mm pieces in four double and two single turrets. One of the criticisms concerning the uselessness of the 152 mm battery had been heard and it had been removed in favor of this configuration giving them a status of “almost monocaliber”.

The secondary armament had however been as always relegated to the central battery in broadside configuration, favouring in line engagement, as learnt from Tsushima. The secondary armament consisted of 76 mm rapid-fire Vickers guns firing from a elevated battery, well-protected flying bridge. The two 3-pdr (47 mm) were still not capable of AA but could be used for saluting.

For the first time, a tripod mast was adopted. The weight of the fire management positions and their high position had caused this choice. Heavier but remaining limited in size, they were wider and had a stronger draft, with a hull design in the shape of a rhombus, thanks to a refocusing of the artillery, improving their hydrodynamic penetration and their speed.

In this regard their performances were worthy of praise: They were fast, stable, manageable and very marine. However the problems related to the mix of their artillery re-emerged in exercises: The sheaves caused by the impacts of 234 mm were too close to those of the 305 mm pieces, which forced the shooting officers to systematically adopt undifferentiated broadside, despite the differences in range of the 234 and 305 mm, to the detriment of the latter, underemployed.

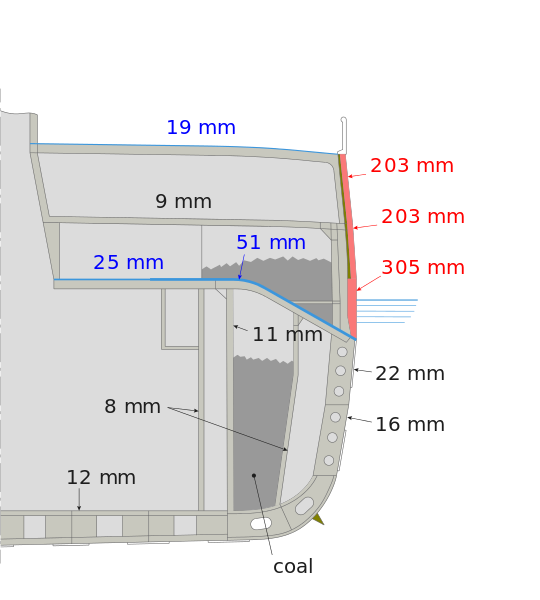

Armor scheme of the Lord Nelson class

This fact was further aggravated by the new 45-caliber model adopted for the heavy guns, which were not delivered until 1908, delaying even further the acceptance into service of these ships, after HMS Dreadnought. They were also assigned to the Home Fleet when they entered service and throughout the war.

HMS Lord Nelson was assigned to the 2nd Line Wing in the Channel in 1914. She became the flagship at the declaration of war, covering among others the convoys of the BEF (French Expeditionary Force) of Lord French, then switched to the Mediterranean in 1915. She bored the “flagship” mark of Admiral Wemyss, then in 1916 of Admiral De Robeck. She was also the flagship of the Alexandria and Aegean fleets. After the armistice, she crossed the Dardanelles to support the White Russians, naturally becoming the flagship of the English Black Sea fleet. Lord Nelson was decommissioned in Sheerness in 1919.

HMS Agamemnon served with the 5th BS squadron in 1914 on the English Channel, then moved in February 1915 to the Mediterranean with the Lord Nelson to take part in the Dardanelles campaign. During the initial operation one she sent thousands of heavy shells of Turkish forts, for 50 hits in return. On May 5, 1916 in the Aegean Sea, one of her gunners crew downed Zeppelin LZ 85 in front of Salonika with a 3-pdr mm DP gun. She then remained assigned to Mudros then Salonica, guarding the Aegean from a sortie of the Battlecruiser Yavuz (ex-Goeben), which happened in 1918. After her return home, HMS Agamemnon ended her career as a controlled target in 1926.

Author’s illustration of the Lord Nelson

Technical specifications

Displacement: 16,100t, 17,600-17,800 t FL

Dimensions: 135.2 x 24.2 x 7.9 m

Propulsion: 2 shaft VTE 4 cyl., 15 boilers, 16,750 hp. 18 knots

Armor: CT 330, belt 305, citadel 203, turrets 305, barbettes 305, decks 102 mm.

Armament: 4 x 305, 10 x 234, 24 x 76, 2 x 47, 5 x 457 mm TTs sub.

Crew: 800

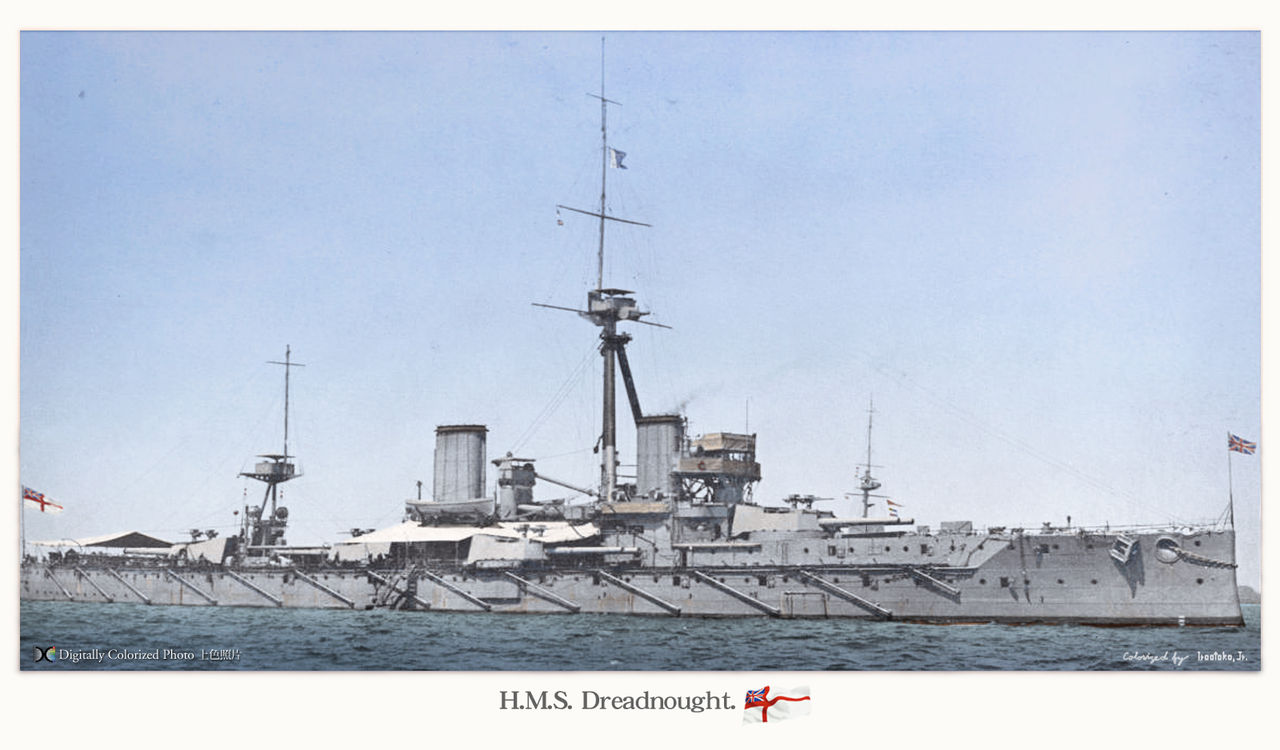

Focus: HMS Dreadnought, the (first) one

HMS Dreadnought, an old English “invincible”, is one of those ships that have marked history. In this case those of the military navies, since all naval treaties refer to its launch. There was a “before” and an “after” Dreadnought.

Indeed, this battleship was the first to take the concept to a much higher level. Since Glory French, armored frigate of 1859 and the first mixed battleship of high sea, Warrior, its British rival of 1860, which was the first battleship with hull in steel of high sea.

Then it was the invention and the generalization of Coles turrets, replacing the guns in ports and in orientable batteries, introduced by the HMS Captain of 1870. It was still the gradual disappearance of the sails in 1880, the arrival in 1885 of the first battleships with steam alone, the revolutions in the machines with steam, more and more complex, up to the standards of battleships “pre dreadnought” that will build all of the great maritime Nations between 1890 to 1906.

Invariably, these generally had four pieces of 305 mm in double turrets, assorted of guns of 203 or 254 mm and almost always of secondary parts of 152 to 106 mm, variegated by guns “revolver” with rapid fire, anti-pilers, of 76, 57, 47, 37 and 20 mm, not to mention the launching tubes to torpedoes. They were also symmetrical from front to rear, walked on coal, measured 135 meters at most, for 22 to 25 wide, 15,000 tonnes, and painfully spun 16 to 18 knots …

The genesis of the Dreadnought deserves a work in itself, but it was clear that this conservatism of battleships seemed irremovable at the beginning of the century. However, a new type of building that appeared in 1890 seemed to be gaining support: The Armored Cruiser. Perfect hybrid, it combined the qualities of speed specific to the cruiser, much superior to the battleship, while possessing an imposing armament, and sufficient armor to resist the fire of their fellows … In addition these ships had just illustrated during of the Russo-Japanese War, and also previously during the Spanish-American war, where these ships were featured and proved to be effective.

At the beginning of the century, the British built very powerful cruisers whose armament began to be worrying even for battleships, including an assortment of large caliber guns distributed in 6 turrets and more, such as the British Defense or Minotaur. Italy, which had always been a pioneer in naval techniques, was looking for solutions. An engineer, and also a theoretician, Colonel Vittorio Cuniberti, had proposed to the Italian admiralty in 1903 a project of “fast battleship” armed only with 6 double heavy turrets.

His project, initially rejected, was nonetheless published in Jane’s Fighting Ships for the British. The idea greatly appealed to Jackie Fisher, the first Lord of the Admiralty, who hastened to commission a study. This quickly gave a construction plan, and the Dreadnought was finally started in October 1905 in Portsmouth, and launched on February 10, 1906, a record of unequaled speed.

Cuniberti saw his plan finally endorsed by Italy, which built its 4 battleships of the Regina Elena class according to the modified principle of Cuniberti. They were still classic battleships, but fast, and provided with a very powerful secondary artillery in turrets. But the Dreadnought will remain the first of this new generation of battleships, which at the time were the center of a fleet, the standard of its power. With Dreadnought, the Royal Navy, which already had an overwhelming numerical and technical superiority, further widened the technological distance, leaving far behind the rest of the world, forced to line up with a delay which it took advantage of to constitute the greatest dreadnoughts force ever seen in 1914.

This ship, technically speaking, was radically different from the previous Nelson-class battleships, started earlier but launched in June and September 1906. The latter had in effect only two turrets of 305 mm, against 5 for the Dreadnought. On the other hand, the Nelson had 6 double and single turrets of 254 mm, faster than the 305 and of almost equal range. Finally, the Nelson managed to spin 18 knots against 21 for the Dreadnought. But above all, the Dreadnought had only 10 pieces of 76 mm apart from its large pieces, perfectly illustrating this concept of “one-gauge” building.

The HMS Dreadnought was accepted in service in December 1906. From then on, it was the model on which two other classes of battleship dreadnoughts were based, the Bellerophon and the St Vincent. Their artillery layout, superstructures and dimensions were similar. This powerful artillery, had as a corollary an increase in dimensions, and these new battleships went from 130 to 160 meters long forever 25 wide, with a more favourable hydrodynamic ratio, and especially 18,000 tons against 15,000 previously. This artillery arrangement, considered better than for the previous Nelson, gave them a firepower of 6 pieces in hunting, 8 in retreat, and 8 in line battle.

The operational career of the Dreadnought was 15 years, since it was demolished in 1921. First flagship of the 4th battle wing, it served in the North Sea in the Home Fleet and managed to sink the submersible U29 of the Commander Weddingen in March 1915 by spurring it … They received an overhaul the following year and served in the 3rd Battle Squadron of Sheerness, receiving 24 then 27 pieces of 76 mm, some of which were anti-aircraft, then again in the 4th Battle squadron from the Grand Fleet to the armistice. She did not take part in the Battle of Jutland, and was placed in reserve at Rosyth in 1919.

Technical specifications

Displacement: 18 110 t, 21 845 T FL

Dimensions: 160.6 x 25 x 9.4 m

Propulsion: 2 shafts Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock & W boilers, 23,000 hp. and 21 n. max.

Armour: 280 Belt Shield, 280 Battery, 280 Barbettes, 280 Turrets, 280 Blockhouse, 76mm Bridges.

Armament: 10 guns of 305 mm (5×2), 10 guns of 76mm, 5 TLT of 457mm (SM).

Crew: 773

British Prewar dreadnought battleships

Bellerophon class (1907)

HMS Bellerophon, Superb, Temeraire

Immediately following the Dreadnought (started on the same plans in December 1906 for the Bellerophon, at Portsmouth; in January and February 1907 for the Superb and the Temeraire, at Elswick and Devonport), these ships were “clones” having some differences minor developments. Thus, they received a large tripod mast in front of their rear chimney, while their defense was improved by replacing their small 76 mm by 402 mm more able to respond to destroyers. This armament was completed by 4 47 mm parade guns, firing blank and which were removed in 1914. their belt armor was slightly stripped but a compartmentalization and internal anti-torpedo armor added.

They were all completed in February and May 1909. In 1915, the 102 mm pieces located on the roofs of the turrets, deemed too exposed, were removed and replaced in the superstructure, their upper masts shortened and they received a new radio installation. We added 2 pieces, 102 and 76 mm AA. The heavy and unnecessary anti-torpedo nets were removed, the bow torpedo tube also, the searchlight platforms also, replaced by others better protected and closed. In 1918 they received launching platforms on two turrets for a hunting Sopwith Pup and a reconnaissance Sopwith 1/1/2 Strutter. They were not salvageable and had to land on land or in coastal fields, or else land in the worst case.

Their career unfolded thus: The Bellorophon was assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron, and suffered a collision with HMS Inflexible, then another with a freighter in August 1914. She fought at Jutland in May 1916, as did the Superb and the Temeraire. The Superb was also the flagship which blew the Dardanelles for a new large-scale action in November 1918. The Temeraire served in the Mediterranean until 1918. It later became a training ship, while the Superb, paid to the reserve became a target ship in 1920, disarmed. It was demolished in 1923, and the other two in 1921.

Bellerophon class illustration by the author

Technical specifications

Displacement: 18,800 t, 22,102 T FL

Dimensions: 160.3 x 25.6 x 8.3 m

Propulsion: 4 propellers, 4 Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 23,000 hp. and 20.75 n. max.

Armour: Belt shield 250, Battery 130, Barbettes 230, turrets 280, CT 280mm, decks 100 mm.

Armament: 10 x 305 mm (5×2), 16 x 102mm, 3 x 457 mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 733

St Vincent class (1908)

The St Vincent class were built in record time, on the plans of the previous Bellerophon, taken from Dreadnought. They had, however, higher upper masts, better motive power, and a slightly longer hull as shallower, more hydrodynamic. Furthermore, their 305 mm guns were of the new Mk.XI model, caliber 50, criticized after the fact for its propensity for excessive recoil, jeopardizing the longevity of the lookout. The critics remained the same regarding the management post of the second mast, handicapped by the smoke from the first chimney, and which was removed.

The St Vincent was like the Collingwood, launched in 1908 and the Vanguard in 1909. They were operational in May 1909, and February-April 1910 for the other two. In 1914, the height of the upper masts was reduced and the two upper guns of the front turret were removed. In 1916 they removed their anti-spin nets and they received two smoke deflectors on their chimneys. In 1915 they received two 76 mm AA guns, replaced by one of 102 mm in 1917. In addition, their stern TLT was removed and two platforms were added to them for a Strutter and a Pup in 1918.

Their career unfolded without notable events, if not the loss of the Vanguard in 1917. The Colingwood had suffered significant damage in 1911 following the collision of a rock off Ferrol, in Spain. She participated in the Battle of Jutland and was placed on the reserve in 1918, serving as a training ship before being demolished in 1922. The Saint Vincent had a similar career. Finally, the Vanguard also participated in the Battle of Jutland, without suffering damage or loss. On the other hand, it was at anchor on July 9, 1917 at Scapa Flow when a bad handling of shells turned to drama. A huge explosion dislocated and pulverized its hull and the ship sank in no time, taking with him death 804 men, all his crew.

Author’s illustration of the St vincent

Technical specifications

Displacement: 19,560 t, 23,030 T FL

Dimensions: 163.4 x 25.6 x 8.5 m

Propulsion: 4 shaft Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 24,500 hp. and 21 knots max.

Armour: Belt 250, Battery 200, Barbettes 230, turrets 280, CT 280mm, decks 75 mm.

Armament: 10 x 305 mm (5×2), 20 x 102mm, 3 x 457mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 718

Colossus class (1910)

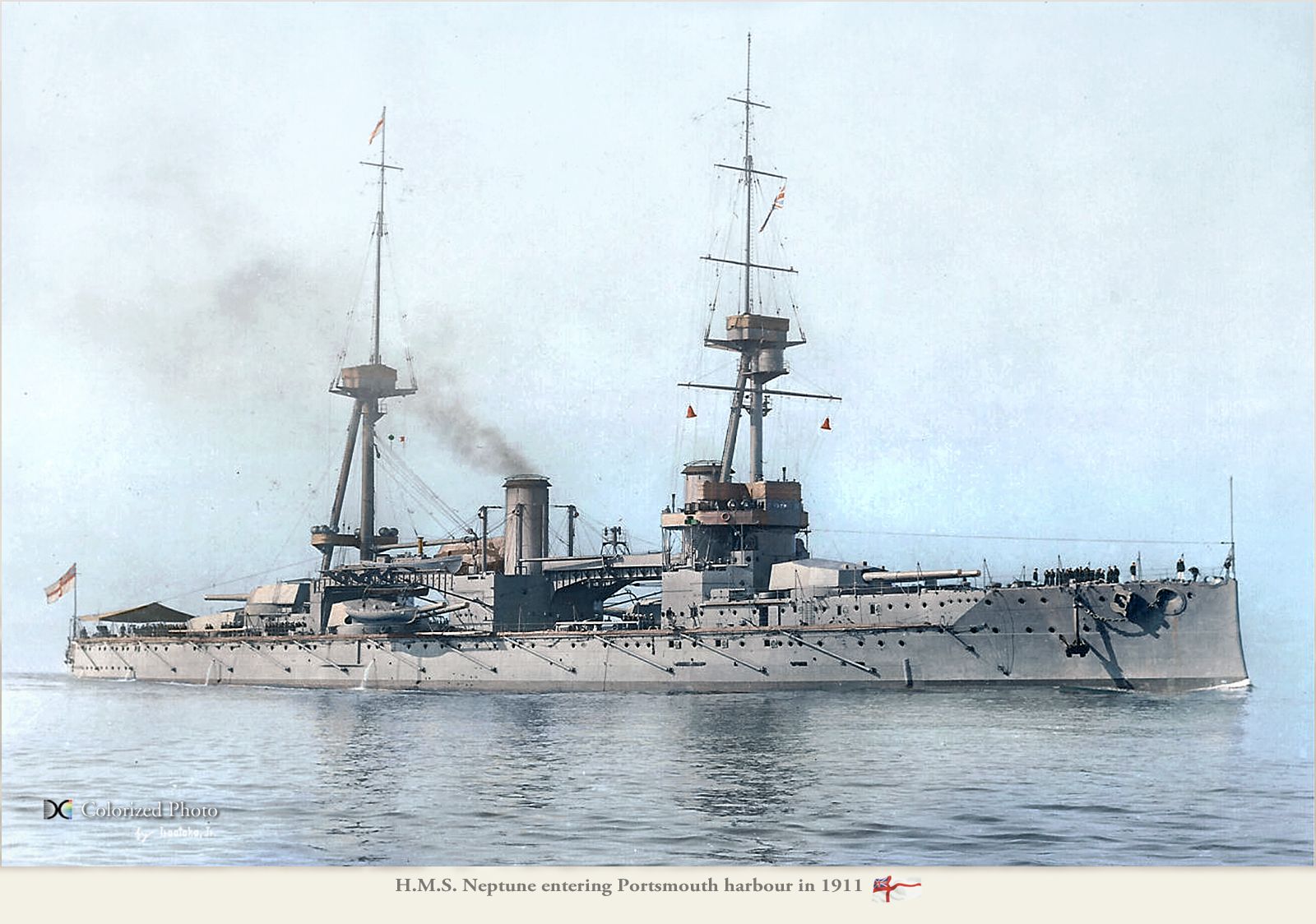

At its launch in 1909, the Neptune had drawn up a new furrow of experimentation in terms of the distribution of the main artillery, with the 5 turrets ventilated always in a front and two rear in the axis and this time the two power stations in staggered rows. Their construction at Scott and Palmers in 1909 also stemmed from the rumor which reported the secret construction of new dreadnoughts by William II. Winston Churchill, who was then head of the trade office, violently attacked the admiralty.

She was the author of the famous “we want eight and we won’t wait” (we want eight (dreadnoughts) and we will not wait). Finally the liberal cabinet, which until then procrastinated and wished to keep a tight naval budget had to bend and alarmed at its all by the report of intelligence service, to start building 6 other battleships of which the first two were the Colossus and the Hercules.

We kept both the number and the caliber of the previous pieces, but with the staggered arrangement of the Neptune. We also went hunting for excess weight and eliminated the bridge located between the second chimney and the rear deckhouse. The central turrets were also closer together, which created a firing arc for the light pieces. We also adopted 533 mm torpedo tubes for the first time and the belt protection was greatly improved, this on the same shell as the Neptune, a puzzle for engineers.

In 1912 the front chimney was raised, in 1915, their heavy anti-torpedo nets were removed and in 1917 their temporary take-off platform was removed on their rear turret, just as the masts were shortened, the rear tripod mast removed, and two light AA pieces added.

After an uneventful start to the career, the Colossus fought in Jutland and was the only English dreadnought damaged there, cashing two shells with 5 victims. In 1919 she served as a training ship and was repainted in a Victorian livery (black hull, white superstructures and shaded canvas). It was decommissioned in 1928. HMS Hercules collided with a steamer in 1913 but was repaired before the war. She participated in the Battle of Jutland with the 6th Division, then embarked the Allied naval commission at Kiel in November 1918 and was disarmed in 1921.

Author’s rendition of the Colossus

Technical specifications

Displacement: 20,225 t, 23,050 T FL

Dimensions: 166.4 x 25.9 x 8.8 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 25,000 hp. 21 knots.

Armor: Belt and Battery 250 mm, 230 mm Barbettes, 280 mm Turrets, 280 mm CT, 100 mm Decks.

Armament: 10 x 305 mm (5×2), 16 x 102mm, 3 x 533 mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 755

Orion class (1910)

Built in the 1909 emergency plan, this four battleships innovated by their main artillery carried to the caliber of 343 mm. The latter brought satisfaction on many points: It outperformed the German calibers by the range and the striking force, while maintaining, with an artillery arrangement with 5 pieces in line, a satisfactory side plating. With the four Orions, the Home Fleet once again became the mistress of the game. The class included the Orions, Monarch, Conqueror and Thunderer (started in March 1910, launched in 1911 (August 1910 for the Orion) and completed in 1912 (January for the Orion, November for the Conqueror).

The installation of their tripod mast, equipped with a new type of direction of fire intended to know the success, behind the front chimney was justified only by the facility which it offered to arrange the cranes raising the lifeboats. Concretely, the smoke from the chimneys impaired its visibility. Similarly the superstructures around the front chimney were redesigned shortly before the war. The underwater protection could not have been reinforced by the addition of lateral ballasts (if not by a higher subdivision below the waterline), in order to preserve the metacentric height of the building with an unchanged speed.

These four vessels formed part of the Grand Fleet, more precisely within the 2nd line squadron, and fought in Jutland in May 1916 without losses, but two had to undergo collisions before the war. They were stripped in 1915 of their anti-spill nets and their masts were reduced, and after Jutland, their armor was reinforced with ammunition holds, and they were equipped with aircraft platforms. The Orion was Leveson’s flagship during the Battle of Jutland. They were decommissioned in 1922-25 due to the Washington Treaty, the Thunderer becoming a training ship until 1926.

Author’s Orion class illustration

Technical specifications

Displacement: 22,200 t, 25,870 T FL

Dimensions: 177.1 x 27 x 7.6 m

Propulsion: 4 shaft Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 27,000 hp. 21 knots

Armour: Belt 300, Battery 250, Barbettes 280, turrets 280, CT 280mm, bridges decks mm.

Armament: 10 x 343 (5×2), 16 x 102, 4 x 37, 3 x 533 mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 752

King Georges V class (1911)

These 4 powerful Dreadnoughts, King Georges V (KGV), Centurion, Audacious and Ajax, were derived from the Orions, but also incorporated the lessons learned from the trials of the battle cruisers Lion and Princess Royal. The design remained classic, with five line pieces and well-cleared superstructures, tall narrow chimneys, a smoke-sheltered firing post, and always light secondary artillery (102 mm pieces) grouped in the front well that we considered 152 mm.

The main innovation resided in the new ammunition developed for the 343 mm pieces, shells with heavier additional charges, which increased their range. They were started in Portsmouth, Devonport, Cammell Laird and Scotts in January-February 1911, launched in October-Nov. 1911 and March-September 1912, and accepted in service in Nov. 1912 (KGV) and March (Ajax), May (Centurion) and November 1913 (Audacious). Paradoxically, this laggard was sunk early in the war (October 27, 1914, after 11 months), and was the only loss of the class.

In 1915, the three survivors received two 102 mm pieces of DCA on the bow at the bow, but removed because they were useless in heavy weather. In 1917, the masts were modified, becoming tripods, while the searchlights were protected in armored towers. The gangway was enlarged and the nets removed. HMS KGV was assigned to the 2nd Line Wing, and received the title of Home Fleet flagship for a time. It was then that of 2 Wing. His career was without notable stories.

After the war, she survived until 1926 as a training ship, then decommissioned and demolished due to the observance of the Washigton Treaty. HMS Ajax deployed to 2 Wing fought in Jutland. At the end of 1918, she entered the Mediterranean and joined the British fleet of the Black Sea which supported the coalition troops against the Bolsheviks. She then remained in Gibraltar until 1924 and was sold soon after.

HMS Centurion, for its part, began its career by testing an unfortunate Italian freighter during its tests. Repaired, she joined the 2nd squadron for the rest of the war. In 1919, she joined HMS Ajax in the Black Sea, then joined Portsmouth after 1924 to be transformed into a target ship. She carried out this task until 1941, still in Portsmouth. She went into the yard to serve as a naval decoy, fitted with welded and camouflaged sheet metal and wood plates to resemble the super-dreadnought HMS Anson in 1942, then was transferred to India, and then returned to Suez by the canal.

She was anchored there until 1944 as a floating anti-aircraft battery. It was then towed to Normandy to be scuttled there in shallow waters and used as a makeshift pier for the artificial port of Mullberry, June 9, 1944. HMS Audacious was naturally assigned to the 2 line squadron. It struck two mines in the Lough Swilly field. Although its watertight bulkheads worked wonders, the water continued to infiltrate slowly, and the deterioration of time prevented towing operations. She therefore sank on October 27, 1914.

Author’s illustration of the KGV

Technical specifications

Displacement: 23,000 t, 25,700 T FL

Dimensions: 182.1 x 27.1 x 8.7 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 31,000 hp. 21 knots

Armor: Shield 300, Battery 250, Barbettes 280, turrets 280, blockhouse 280mm, bridges 100 mm.

Armament: 10 x 343 (5×2), 16 x 102, 4 x 47, 3 x 533 mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 782

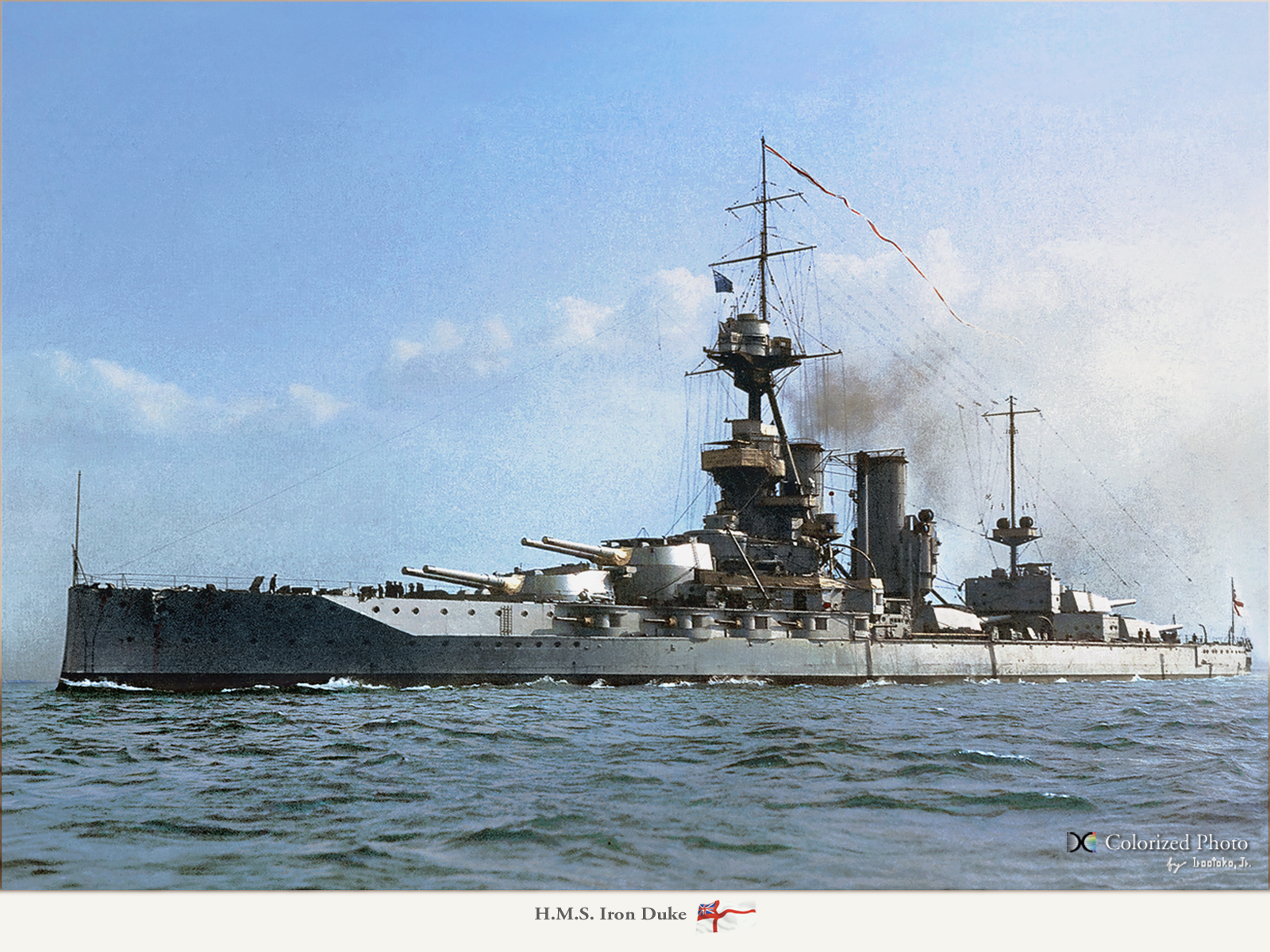

Iron Duke (1912-13)

The 4 battleships of this class (Iron Duke, Marlborough, Benbow and Delhi – later Emperor of India), were put on hold in Portsmouth, Devonport, Beardmore and Vickers in 1912 (two in January, two in May). They were born not from the ideas of Sir John Fisher, who left his post as first sea lord in 1910, but from the admiralty, who under pressure from the exercise admirals wanted a less dogmatic approach than proponents of the “speed and exclusive heavy artillery” school.

The 152 mm pieces were reintroduced into the secondary battery, those of 102 mm being considered too weak, and the 533 mm torpedo tubes were adopted as a new standard. For the rest, these vessels were inspired by the King Georges V, by their artillery layout, but went to a tonnage close to 30,000 tonnes, with a speed slightly higher than 21 knots. Their main artillery did not change.

In addition, their fire management position was reinforced, which had become an essential control body, enlarged and supported by a solid tripod. They were also the first battleships equipped with anti-aircraft parts, the “12-pounders” (76 mm). Very long, these pieces were intended to slaughter the Zeppelins. HMS Iron Duke carried out its tests with anti-spill nets, quickly removed and never adopted by other ships of its class.

The configuration of their secondary battery meant that all the parts except two were at the front, and the two rear, were quickly considered too low and ineffective in the big weather (they were removed during the war, and they were carried over to the upper battery). These barbettes also had a new type of reinforced integral shield which was also adopted on the HMS Tiger and battleships of the Queen Elisabeth class. They also reinforced their light armor after the battle of Jutland, around the projectors, the bridge and the ammunition bunkers. In 1918, their fire control tower was considerably enlarged and their mast shortened while the aircraft platforms were placed on the central and second front turrets.

Their career unfolded without surprise within the Grand Fleet. They were completed in 1914, and put into service in March, June, October and November 1914. As a result, their crews were not yet well trained at the start of the war, but nonetheless, these powerful ships were the spearhead of the Royal Navy.

HMS Iron Duke was also the flagship of the Grand Fleet until November 1916. She fought in Jutland with the 2nd Line Wing, and after the war was sent in 1919 to the Mediterranean, then passed in black sea to support the White Russians, until 1920. She then served in the North Atlantic squadron until 1929 before being reformed following the limitations of the Washington Treaty and radically converted in 1930 as a training ship . Partly disarmed, stripped of its armor and its machines restrained for an effective speed of 18 knots, it served for the instruction until 1939.

Based in Scapa Flow, it then served as pontoon, totally disarmed. On October 17, 1939 she suffered a German air attack and was damaged. Repaired and left at anchor, it was not demolished until 1946. The three other units of the class served in Jutland – The Marlborough was torpedoed and repaired in three months – in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean after the war. They were reformed in 1929-32.

Author’s illustration of the Iron Duke

Technical specifications

Displacement: 25,000 t, 29,560 T FL

Dimensions: 189.8 x 27.4 x 9 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 18 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, 29,000 hp. 21.3 knots

Armour: shield 300, Battery 250, Barbettes 250, turrets 280, blockhouse 300, bridges 65 mm.

Armament: 10 x 343 mm (5×2), 12 x 152, 2 x 76 AA, 4 x 47, 4 x 533mm TTs (sub).

Crew: 1022

Wartime Battleships

HMS Agincourt (1913)

This singular ship with a turbulent fate had originally been a dreadnought ordered by Brazil under the name of Rio de Janeiro in order to counter Argentina which had just ordered from the USA its two dreadnoughts of the Riachuelo class. The two Minas Gerais were in their time the most powerful warships in the world, Brazil wanted to republish the thing and from the design the new dreadnought gave in excess. Nothing less than 30,000 tonnes at full charge, more than two hundred meters long, and above all an online battery of 14 pieces of 305 mm, four more than the standard of the time. It was commissioned from the Armstrong yards. A change of government intervened, however, during the design, and the ship was started in September 1911 but canceled by the new majority. In July 1912, the government which had suffered a serious economic crisis sought to resell it.

The ship remained on sale as construction continued. It was launched on January 22, 1913. Finally, the Rio was completed in February 1914, at the same time Turkey emerging from the Balkan War deprived of a number of buildings was trying to counter the Greeks with a new battleship. Thus the large ship became Sultan Osman I. In August 1914 it was in completion and was requisitioned by the admiralty for the Grand Fleet. This requisition infuriated the Turkish government and participated in their decision to join the triple alliance of the central empires. The name was changed once again, this time definitively, to HMS Agincourt, from the name of a famous battle of the Hundred Years War.

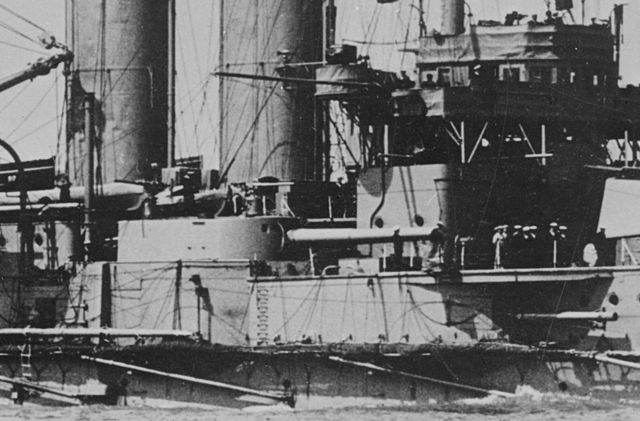

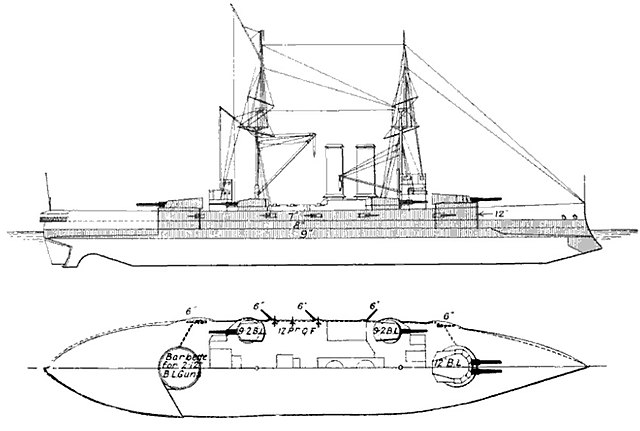

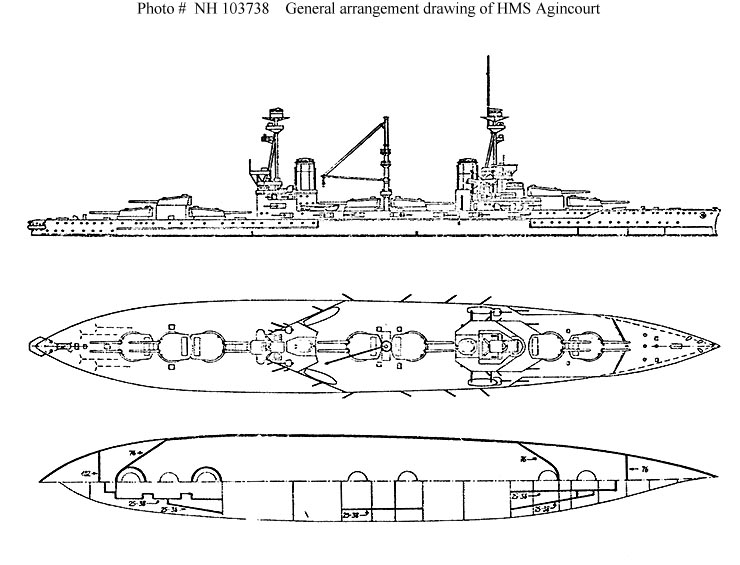

Plan and elevation of the Agincourt, shoiwng its extreme axial turret arrangement

The Agincourt was unique in more ways than one and was not particularly appreciated by the admiralty. On the one hand, its 14 pieces of 305 mm were of a specific model (and turrets named according to the days of the week), and not standard, which posed maintenance problems. On the other hand the protection had been sacrificed to avoid overweight, but the speed was only 22 knots. Then, all these openings and these magazines and loading mechanisms weakened the structure of the hull. In addition, In return for the tremendous flight it could offer on the side, they could not be fired at the same time for fear of causing such a roll that the ship risked capsizing.

The shooting officer who commanded the “Gin palace” (nickname of the full side plating in the Royal Navy) slightly shifted their light, which remained unequaled. In hunting as in retreat, 4 pieces of an already exceeded caliber (305 mm) was not a miracle and remained below the capacities of the new contemporary British and German Dreadnoughts. In the end, the Agincourt remained a prototype, which fought in the Grand Fleet. We saw it in the fire in Jutland, firing 144 shells. German observers believed during his salvo that it was the explosion of a battle cruiser as the effect was striking. It was then modified, equipped with DCA while it lost its heavy central gangways and its aft tripod mast in order to gain stability. It was reformed in 1921 and demolished in 1922.

HMS Agincourt, author’s illustration

Technical specifications

Displacement: 27,500 t, 30,250 T FL

Dimensions: 204.7 x 27.1 x 8.2 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 22 B&W boilers, 34,000 hp. 22 knots.

Armour: Belt 230, Battery 200, Barbettes 230, turrets 300, CT 300mm, decks 65 mm.

Armament: 14 guns of 305 (7×2), 20 of 152, 12 guns of 76 (2 AA), 3 TLT of 457mm (stern, sides).

Crew: 1115

HMS Erin (1913)

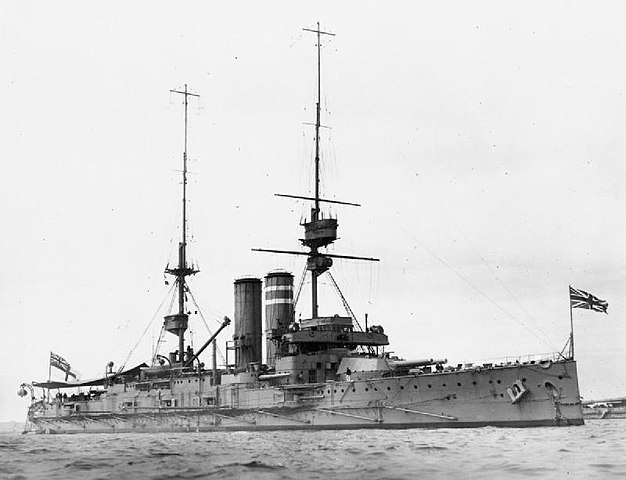

HMS Erin in Moray Firth 1915 (IWM)