An unexpected Turkish flagship – The Yavuz Sultan Selim, aka “Yavuz” became in August 1914 the new flagship of the Turkish Ottoman Navy, until then a motley collection of inoffensive museum pieces with a few modern vessels. Basically the German African squadron, based in Dar-es-Salaam, took refuge in Constantinople, not being able to reach the strait of Gibraltar. This squadron, under command of rear-admiral Wilhelm Souchon flagship Goeben, Moltke class) also comprised the light cruiser Breslau, also brand new.

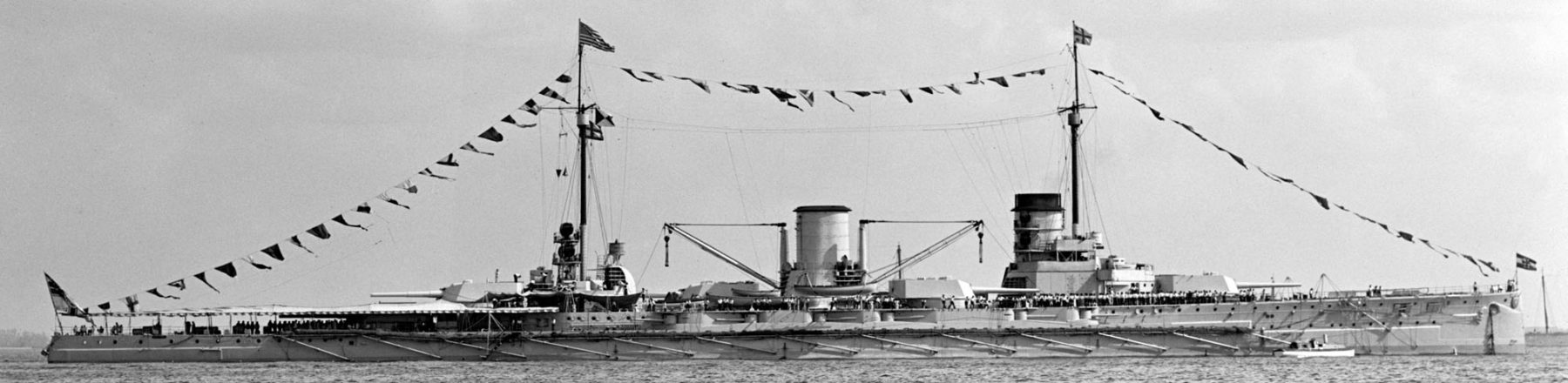

Profile of the SMS Moltke, identical to the Goeben.

After taking refuge into the only possible sympathetic harbour, the kaiser officially transferred both ships to Turkey. The German officers took the Fez and both ships were renamed while the red flag with crescent replaced the Prussian Jack. SMS Goeben became the Yavuz Sultan Selim, and SMS Breslau became with the Midilli ex-Breslau), and both were soon found the most active Turkish Ottoman fleet, rampaging the black sea and duelling with the Russian Imperial fleet in several occasions. The Midilli was lost in action but the Yavuz survived, was repaired at St. Nazaire in France in the 1930s, and stayed as the best guarantee of neutrality for Turkey during WW2 as well. When she was discarded

Wilhelm Souchon had little options and sailed towards the east even before the declaration of war, expecting to intercept French troop transports sailing from Oran and Casablanca to mainland France.

Wilhelm Souchon had little options and sailed towards the east even before the declaration of war, expecting to intercept French troop transports sailing from Oran and Casablanca to mainland France.

Souchon’s great escape (August 1914) – Goeben and Breslau

Author’s map of Souchon’s “great escape” in the Mediterranean.

The German “Mediterranean Squadron” in peace time was ordered by Kaiser Wilhelm II in case of war precisely: Both the Goeben and Breslau had two tasks: Either raiding in the western Mediterranean, prevent French troops reinforcements from North Africa, or making it out into the Atlantic, returning home while disrupting commerce en route. The options were left on the squadron commander’s discretion. On 3 August 1914, when it was clear war was nearly inevitable the squadron was heading west, towards Algeria, when Wilhelm Souchon received the confirmation of a declaration of war against France. Therefore SMS Goeben immediately proceeded off Philippeville (Skikda, Algeria), shelling the city for about 10 minutes, Breslau doing the same at Bône (Annaba). Yet mobilization just commenced and no troops was recalled to join ships. Von Tirpitz and Hugo von Pohl transmitted secret orders to the admiral, which received the order to run east towards Constantinople. It was a violation of the Kaiser’s instructions and apparently not concerted.

SMS Goeben had to resupply coal and headed for neutral Messina, crossing en route (and saluting) the British battlecruisers HMS Indefatigable and Indomitable (UK was still neutral by then). However both British ships (under instructions) turned to follow the Geran squadron closely. Using the night, Souchon ably outruned the British and arrived in Messina by 5 August, proceeding with coaling. Since Italian neutrality was announced on 2 August there was a delay of only 24 hours to proceed.

However sympathetic Italian naval authorities allowed 36 hours to allow crews from a German collier to complete their task. Despite of this, stocks were not enough to make it to Constantinople. Therefore Souchon had to arrange a rendezvous with another collier in the Aegean Sea. The French fleet did not ventured east, as Admiral Lapeyrère believed the the Germans ain objective was either to head for the Atlantic or join Pola in the Adriatic.

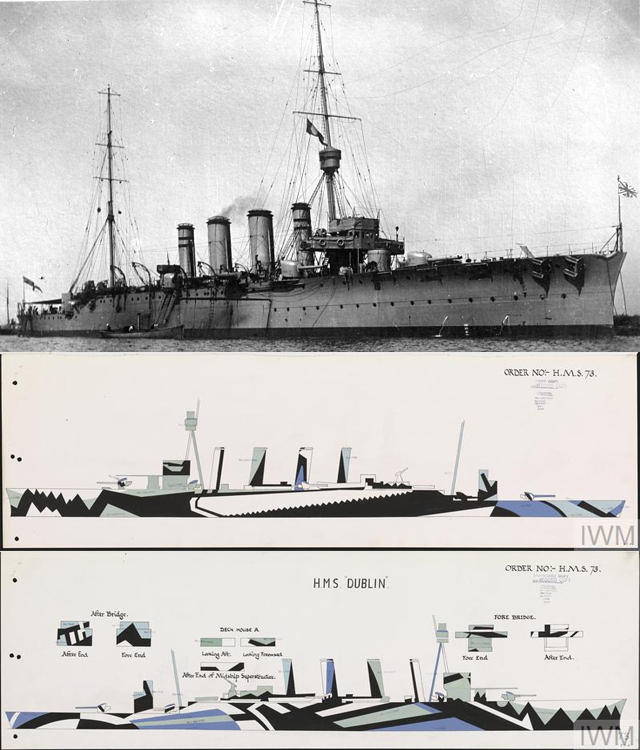

HMS Dublin (and camouflage pattern of 1918 – IWM)

Souchon eventually departed Messina early on 6 August, sailing due east. The British battlecruisers were waiting for them 100 miles away. HMS Inflexible in addition was still coaling in Bizerta and not available, and the closest British force was the 1st Cruiser Squadron (HMS Defence, Black Prince, Duke of Edinburgh and Warrior), four recent and capable armoured cruisers under Rear Admiral Ernest Troubridge. The Germans feinted at first a run towards the adriatic to lure Troubridge, which indeed sailed to the mouth of the Adriatic, hoping to catch them there. However he soon reversed course as the Germans veered east again. Light cruiser HMS Dublin and two destroyers were detached to try a torpedo attack but Breslau’s lookouts spotted them and soon with darkness falling, both ships evaded again. Troubridge stopped his chase the following morning, on 7 August, therefore leaving Souchon free to join Constantinople…

The Yavuz (Moltke) design

Following the Von der Tann, the Moltke class (Moltke and Goeben) were launched in April 1910 and March 1911 respectively. They were commissioned in March and August 1912. Compared to the Von der Tann they were much improved. The hull revised and reshaped, longer for a gain in top speed. The additional space was enough to accept a supplementary turret at the stern. The forecastle was left free of additional charge for the sake of stability. Armour thickness overall was raised from 50 mm to 100 mm for some vitals, like the blockhaus, citadel, barbettes and casemates but the belt, conning tower and turret were not improved.

The Moltke class ships were 186.6 meters (612 ft 2 in) long, 29.4 m (96 ft) wide, and with a 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in) draft when fully loaded, displacing 25,400 t (25,000 long tons). They were propelled by a set of four Parsons turbines fed by 24 coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boilers. Normal rating was 51,289 shp (38,246 kW) and designed speed 25.5 knots bt they can make much more. At 14 knots they were still capable of a range of 4,120 nautical miles (7,630 km; 4,740 mi). Armament was less than British battlecruisers on paper: Ten 28 cm SK L/50 guns placed in the axis, one forward on the forecastle, two in a superfiring pair aft, and two en échelon abaft the funnels. This was completed by the twelve 15 cm SK L/45 guns in the central casemate and the same number of QF guns, 8.8 cm SK L/45 guns placed in sponsons along the hull and under masks on the superstructure. This was augmented by the usual four 50 cm (20 in) submerged torpedo tubes.

Wartime Modifications

The new guns mounts however had at first a lower elevation, later fixed. During war two to the Goeben’s four 152 mm barbette guns were deposed on the Yavuz. In the fall of 1916 the twelve anti-TBs QF 88 mm guns in sponsons were replaced by four 88 mm L/45 Flak AA guns. Both battlecruisers could reach and maintain 28 knots, counting on 85,000 hp. Also at the end of 1916, new fire stations were adopted, placed on the military masts. The latter were strengthened to allow the load. Also additional projectors were placed for night fighting.

A very active career

The transfer

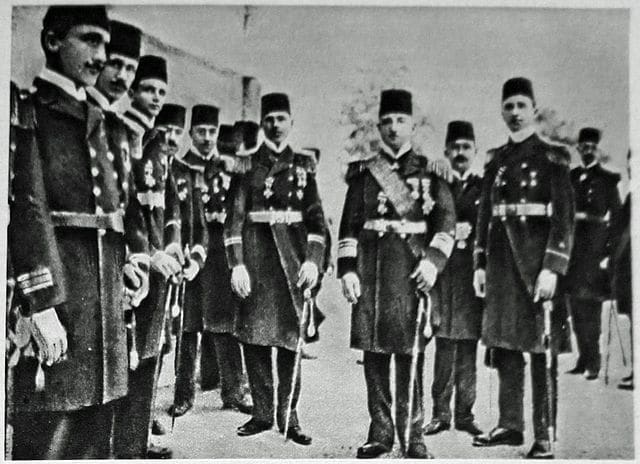

After evading the British (Troubridge would not risk his slower and less well armed cruisers anyway), Goeben and Breslau supplied again off Donoussa near Naxos and in the afternoon of 10 August, before they entered the Dardanelles. Mission complete. Spotted and guided by an Ottoman picket boat, they proceeded in the Sea of Marmara. At that time however, Ottoman Turkey was still neutral. The ships had 24h to stay. The Turks proposed a transfer “by means of a fictitious sale.” The Germans at that point still did not approve the transaction whereas it has been already announced and made official on 11 August. The price was 80 million Marks and a formal ceremony took place. Both ships were commissioned in the Ottoman Navy on 16 August. A Turkish flag was raised on their stern pole, and on 23 September, Souchon accepted to command the Turkish fleet. SMS Goeben was renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Breslau Midilli while the German crews were given Ottoman uniforms and fezzes, the typical red hat.

The great paradox was Yavuz’s own career was perhaps more active and colorful than her sister-ship SMS Moltke. The latter fought at the battle of Dogger bank the first month of the war, being torpedoed by the British submarine and repaired, to score 6 hits on HMS Tiger (Battle of Jutland) in 1916 and was not heard of until the great of April 24 1918, where she lost a propeller, was torpedoed and repaired again until the surrender. Yavuz was regularly raiding the Russian coast and became by far the most active Turkish war vessel during the conflict.

The Great War

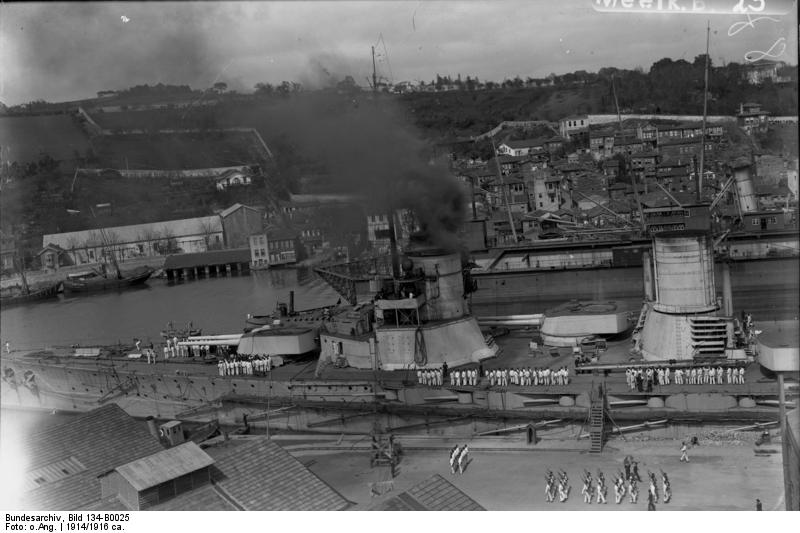

Bundesarchiv – Goeben in the Bosporus

On 29 October 1914 Yavuz sailed for her first mission, bombarding Sevastopol. The Ottoman Empire was not yet however at war with the Entente and Souchon decided of the operation to force Turkey into the war on the side of Germany. During this mission, Yavuz took a 25.4 cm (10 in) hit from fortifications guns in the after funnel, failing to detonate, and two others inflicted minor damage. Better than this, both German ships went right through an inactive Russian minefield, and emerged unscaved.

However when closing to Turkish waters, Yavuz crossed the Russian minelayer Prut. The latter scuttled herself with 700 mines on board while escorting Russian destroyer Lieutenant Pushkin was took care of by Yavuz’s secondary battery 6-in guns. At last Russia declared war on 1 November, and the Ottomans went on the war foot whereas France and Great Britain ships raided soon the Turkish fortresses of Dardanelles on 3 November 1914, followed by a formal declaration of war two days later. The Russians knowing the presence of the Yavuz started to reinforce the entire Black Sea Fleet and rethink Sevastopol’s defences strategy.

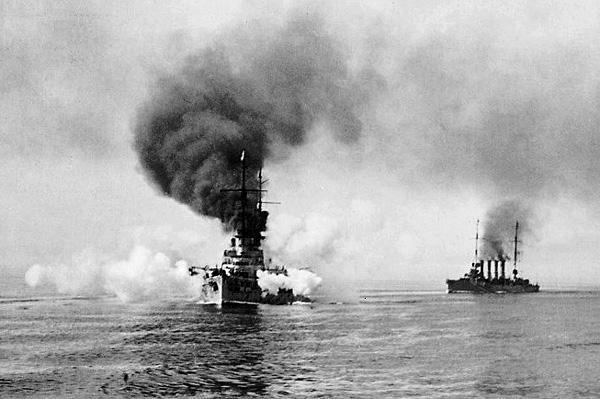

Goeben and Breslau entering the Dardanelles

Yavuz and Midilli would sail again, trying to intercept the Russian Black Sea Fleet. They met the Russians 17 nautical miles off the Crimean coastline on 18 November 1914, just returning from a shelling of Trebizond. It was noon and foggy so mutual spotting was nigh-impossible. The Black Sea Fleet tried a concentrating fire controlled by a “master” ship again as a rsult of the Russo-Japanese war and in this case, Ioann Zlatoust became the master ship. See the battle of Cape Sarytch

Evstafi spotted Yavuz, but Zlaloust did not, wasting precious minutes. The gunnery commands were finally received at 4,000 yards (3,700 m) in excess of Evstafi’s estimate of 7,700 yards (7,000 m) so she opened fire with her own data, scoring a hit with her first salvo. Yavuz’s 150 mm casemate was penetrated and detonated some ready-use ammunition. The resulting fire filled the casemate, killed thirteen men and wounded three but the fire was contained.

The Yavuz in Sevastopol, 1918 (Cropped). Original

At that point Yavuz returned fire. Evstafi was hit twice in the middle funnel, also loosing the antennae for the fire-control radio so for the remainder of the battle she could no longer correct Ioann Zlatoust’s inaccurate data while the other Russian ships relied on her and missed the Yavuz completely. Meanwhile Yavuz hit Evstafi four more times. After 14 minutes of duel however, Souchon decided to retire, his ship having scored four hits claming the killing of 34 men and wounding 24 Russian sailors.

On 5–6 December 1914, Yavuz and Midilli escorted troop transports. On 10 December, Yavuz shelled Batum. On 23 December, Yavuz and Hamidiye escorted three transports to Trebizond. On 26 December after another escort mission however, Yavuz struck a mine beneath the conning tower, on the starboard side, outside the Bosphorus. The 50-square-meter (540 sq ft) gaping hole provoked a flood quickly stopped by the torpedo bulkhead. However barely two minutes later, a second mine detonated on the port side forward of the main battery wing barbette. The bulkhead bowed in 30 cm (12 in) but held again and the ship survived despite some 600 tons of water entering the hull. Since no available dock could service the Yavuz, temporary repairs were made inside tailor-made steel cofferdams pumped out of water to create a dry work area. Holes were patched with concrete, holding until the end of the war. True repairs were made afterwards, by default of a true drydock large enough in the region. Conditions of the hull degraded badly over intensive service. In 1918 she was barely able to maintain 24 knots for an extensive period of time.

Admiral Souchon and staff in Turkish uniforms

Despite taking heavy damage, Yavuz, barely repaired header straight from the Bosphorus on 28 January and helped Midilli on 7 February 1915 escape to the Russian fleet, also covering the return of Hamidiye. Repairs for the damage was done and lasted until May. On 1 April, and still not completely repaired, Yavuz made another raid with Midilli, covering the battleships Hamidiye and the protected cruiser Mecidiye returning from Odessa, after shelling the city and installations. Strong currents to the approaches of the Dnieper-Bug Liman (bay) leading to Nikolayev made the cruiser slow, and after a correction, Mecidiye struck a mine and sank. Yavuz and Midilli raided Sevastopol, sinking two cargo steamers, and drew to them the whole Russian fleet in hot pursuit, launching several destroyers. One, the Gnevny, catch them and and launched torpedoes but missed. But ships were fast and agile and they returned again safe to the Bosphorus.

On 25 April, the day of the Gallipoli landings, a Russian fleet raided the Bosphorus, shelling the forts. Two days later Yavuz raided the coast south of the straits to shell Allied troops at Gallipoli together with the battleship Turgut Reis. Spotted by a kite balloon at dawn however they were greeted soon after by the 15-inch (380 mm) guns of HMS Queen Elizabeth. Seeing the massive water plumes, Yavuz made it close to the cliffs, too close for comfort, to be fired by Queen Elizabeth. She shelled the beach and departed. On 30 April Yavuz did the same, this time, spotted by HMS Lord Nelson which was already taking care of the fortifications at Çanakkale. However she could only fire five rounds before Yavuz disappeared from view, unharmed.

On 1 May, Yavuz was in the Bay of Beikos, trying to catch the Russian raiding the northern fortifications of the Bosphorus. By 7 May, Yavuz made another sortie for the same raid, and chased the ships to Sevastopol. She failed however to bombard Sevastopol, being short of ammunitions. On the morning of 10 May she spotted two Russian pre-dreadnoughts, Tri Sviatitelia and Panteleimon, and the duel started. Ten minutes later she had been hit twice but without serious damaged, and disengaged. At her return she was chased by Russian destroyers but escaped. Between the allied fleet south and Russian superiority it was eventually decided to have her rested, overhauled and repaired. Her secondary 6-in guns (15 cm) were taken ashore as well as four 8.8 cm guns from the aft superstructure. In the fall of 1915 she gained four 8.8 cm AA guns installed in place of her former guns.

Kaiser Whilhelm II visiting the Goeben -(Bundesarchiv) during his stay in Constantinople, October 1917. He came as guest of allied Sultan Mehmed V.

In July, 18, Midilli struck a mine;, taking some 600 long tons of water. She had to abort mission, escorting a coal convoy from Zonguldak to the Bosphorus. Yavuz sailed out to replaced her on 10 August eventually. She covered five coal transports together with the Hamidiye and three torpedo boats. One of the collier was sunk during the trip by the Russian submarine Tyulen. The following day, Tyulen and another submarine reported attacking the Yavuz, but they failed to place them in position to fire. Anoher convoy was later attacked on 5 September by the Russian destroyers Bystry and Pronzitelni. It was protected by the Hamidiye and two torpedo boats and as the first failed to fire her 15 cm (5.9 in) guns as the mechanism soon broke down. A desperate message was sent to the admiralty and Yavuz was called to the rescue, but too late: The Turkish colliers had been beached to avoid capture in between.

On 21 September, Yavuz sortied again to chase off three Russian destroyers again menacing a collier convoy. She made two other escort missions until 14 November. That day, the convoy was attacked by the submarine Morzh. The latter placed in the right position to launch a torpedo attack, two torpedoes near-missing the Yavuz just outside the Bosphorus. Admiral Souchon decided to break off and leave the convoy, not taking the risk and assuming he wuld be approved by the admiralty. The convoy from Zonguldak to Constantinople was made by night, escorted by TBs only. By the end of the summer, the Russian black sea fleet greeted two new dreadnoughts, Imperatritsa Mariya and Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya. They were fast and well protected, making the task of Yavuz even more complicated.

Yavuz sailed to Zonguldak on 8 January trying to met and cover a returning collier, protecting the trip from possible Russian destroyers but eventually failed to do so. The collier was sank. On her return trip she encountered Imperatritsa Ekaterina, both capital ships engaging in a brief artillery duel at 18,500 meters. Yavuz turned to the southwest to present her broadside, firing five salvos but failed to make any hit, whereas she was also near missed in return. In theory she was faster than the Imperatritsa Ekaterina, almost 28 knots versus 21, but since she had seen extensive service since August 1914 without a single stop in a drydock her bottom was badly fouled, her propeller shafts were also degraded and her machines already worn out. So she barely escaped the Russian battleship, which could chased her at 23.5 kn by overheating her pristine machinery.

The Caucasus Campaign saw Russian troops progressing rapidly and Yavuz was used as an improvized troop transport, landing 429 men plus a mountain artillery battery, machine guns, planes, some 1,000 rifles, and 300 ammunitions cases to Trebizond. This happened on 4 February, and one month later the Russians did the same on either side of the port of Atina. The Turks were eventually forced to evacuate. However another landing took place at Kavata Bay, 5 miles east of Trebizond in June 1916. Later this month, a counter attack took place, covered by the guns of Yavuz and Midilli. Thy multiplied these missions and On 4 July, Yavuz raided Tuapse, sinking a steamer and motor schooner. They sailed northward before the two Russian dreadnoughts left Sevastopol and returned to the Bosphorus. At last Yavuz was docked for repairs, which lasted until September. Later on, coal shortages prevented further operations which were few in 1917. An armistice was eventually signed between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in December after the revolution. Operations then almost ceased completely. The treaty was in Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. The Russian started to deliver coal again for the Turks which were able to resupply.

Stapell.: 28.3.1911

“Goeben” in der Steniawerft (vor 1917)

Bosporus

vor der Werkstatt rechts das desarmierte Kanonenboot “Kubanez” als Mutterschiff des Bergeverbandes

On 20 January 1918, Vice Admiral Rebeur-Paschwitz replaced Souchon, back in Germany since September, a well-deserved leave. His intention was to draw Allied naval forces away from Palestine, by raiding with the Yavuz and Midilli this sector and the aegean islands which were used as bases. This became the Battle of Imbros. Yavuz sank the monitors Raglan and M28 at anchor and proceeded to the port of Mudros for further rampage when she was engaged by the British pre-dreadnought HMS Agamemnon. However en route, Midilli struck several mines and sank while Yavuz hit three mines and barely made it back, limping, to the Dardanelles. She was chased by British destroyers HMS Lizard and Tigress, eventually beached near Nagara Point, covered by coastal artillery. Bombers from No. 2 Wing RNAS tried to damage her, in vain. The monitor M17 latter joined the fray and shelled Yavuz on 24 January 1918. She fired ten rounds and missed, while nearly be sank by a vigrous Turkish artillery fire. The submarine E14 later sailed and tried to locate the Turkish capital ship, without luck. Yavuz has been towed by the Turgut Reis out of harm up to Constantinople. Seriously crippled, the war was nearly over for her, as repaired lasted from 7 August to 19 October.

Before that, she escorted a delegation of the Ottoman Armistice Commission to Odessa on 30 March 1918, sailed in May to Sevastopol for a drydock maintenance, and sailed for Novorossiysk on 28 June, only to find scuttled Soviet ships when she arrived. Yavuz returned to Sevastopol, laid up from July to August with her fouling scrapped, leaks repaired, returned to Constantinople to be placed in a concrete cofferdam in order to repair her mines damage.

According to peace conditions, the German navy would have to repatriate the Yavuz in order to have her interned at Scapa Flow. Instead, the Geran government transferred the ship to the Turkish government officially on 2 November. She fell under the Treaty of Sèvres conditions and was to handed over to the Royal Navy as war reparations. However soon the Turkish government fell into a War of Independence, Greece meanwhile attempting to seize territory. With the victory of the nationalistic “young turks”, the Treaty of Sèvres was discarded, and the Treaty of Lausanne was signed the next year in 1923, allowing the new Turkish republic to retain the Yavuz.

The Interwar years: The great refit of the Yavuz

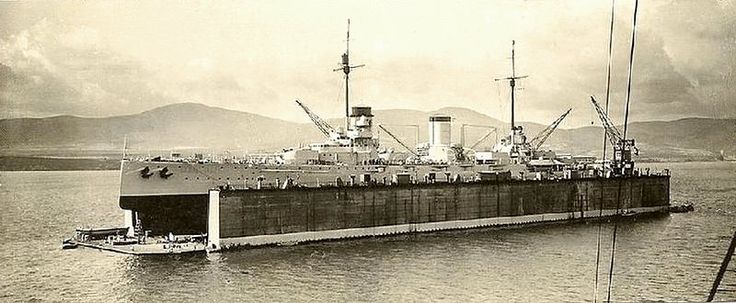

The new Turksh stated feeble navy was now composed of really worn out and obsolete vessels, only compensated by the sold presence of the Yavuz. The capital ship of the new navy however needed to be refurbished and if possible modernized; She became also a precious instrument of diplomacy and dissuasion towards the Greeks. Indeed the latter had two pre-dreadnoughts and and armourr cruisers inferior in speed to the Yavuz. The battlecruiser was stationed in İzmit until 1926 however, without care and doing much service. At that stage an admiralty report ed only two boilers in working order, steering almost inoperant and still some mine damage unrepaired, which deformed the hull and made her loosing speed. At last a budget was secured to purchase a 26,000-metric-ton (26,000-long-ton) floating dock from Germany. Indeed the admiraklty could not contemplate to see her joining any drydock nearby large enough for the tasks at hand.

Yavuz could not be towed anywhere without risk. When the new dock arrived, the admiralty had secured the help of the French company Atelier et Chantiers de St. Nazaire-Penhöet in December 1926 to oversee the refit. This took place off the Gölcük Naval Shipyard in the new floating dydock, lasting over three years until 1930. There were some mishaps and delays however. Recurring problems with the drydock were so bad, an investigation was launched as the new Minister of Marine Ihsan Bey was convicted of embezzlement. Further delays were caused by other fraud charges whereas the Ministry of Marine was abolished. The refit was now in the hands of the Turkish Military’s Chief of Staff, Marshal Fevzi, which slowed down or stopped all naval building programs. Only with the threat of a Greek large-scale naval exercise off Turkey in September 1928, worked resumed, whereas the government ordered four destroyers and two submarines from Italian shipyards. The Greek Government tried to oppose the completion of Yavuz’s refit, but in vain, while the Turks which claimed the Yavuz was to oppose the Soviet threat of the black sea fleet instead.

For the Yavuz, the refit was not still a reconstruction: The mine damage was completely repaired, her hull streamlined, displacement increased to 23,100 t by the addition of bulges and new compartments, revision of the protection. The hull was reduced in length by 50 cm but larger of 10 cm. The powerplant was entirely rejuvenated, with new boilers, a French fire control system for her main artillery. Another two 15 cm barbette guns were removed from the casemate.

The Turkish capital ship was at last recommissioned in 1930, as flagship of the new Turkish Navy. Her speed trials showed excellent performances, like in 1913, and her new gunnery and fire control trials went smoothly as well. In addition she was now accompanied by four brand new, modern destroyers, entering service in 1931-1932. With the Yavuz back in the game, the Soviet Navy ordered the battleship Parizhskaya Kommuna and cruiser Profintern to be transferred from the Baltic to the Black Sea Fleet in 1929, while the Greeks ordered two destroyers.

In 1933, Yavuz carried the minister İsmet İnönü from Varna to Istanbul and later the Shah of Iran from Trebizond to Samsun in 1934, while her name, formally ‘Yavuz Sultan Selim’ was shortened to ‘Yavuz Sultan’ in 1930 and ‘Yavuz’ in 1936. In 1938 she was refitted again, and in the fall of the year carried the remains of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk from Istanbul to İzmit. Evaluated by the British Naval Attache in 1937, her substandard AA armament made her considered obsolete. However the Turkish admiralty was well aware of this and planned to expand and modernize the navy again, plans including two 10,000 ton cruisers and twelve destroyers (which never took place). One of these cruisers was intended to replace the Yavuz in 1945 and later a new capital ship of 23,000 ton from 1950. The building program were cancelled as WW2 broke out and Yavuz stayed as the Turkish capital ship until 1945.

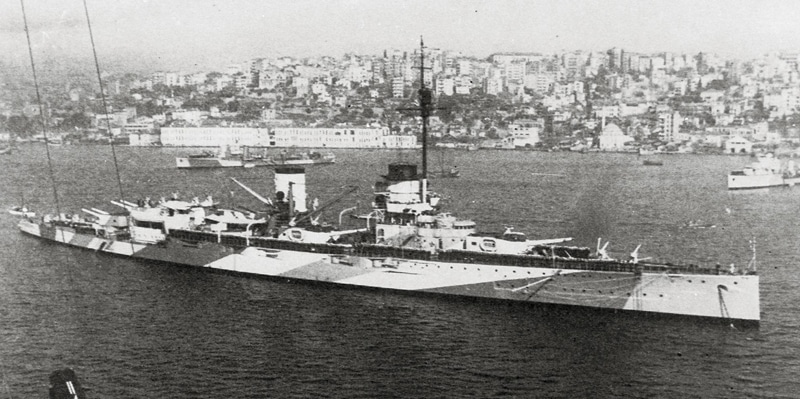

The Yavuz in World War two

In November 1939 the press started to compared the only capital ships of the black sea, Yavuz and Parizhskaya Kommuna. The former was made a winner because of the poor conditions of the second. In 1941, Yavuz at last had her anti-aircraft battery strengthened to four German Rheinmetall 88 mm (3.5 in) guns and ten 40 mm (1.6 in) guns, plus four 20 mm (0.79 in). As the war progressed, this AA armament was increased again to twenty-two 40 mm guns and twenty-four 20 mm guns, making her even more potent as a battleship, despite her weak protection in modern standards. Turkey stayed neutral until the war ended and Yavuz mostly remained inactive in Constantinople, also as a guarantee of neutrality. She was camouflaged at an unknown date, with a class Mediterranean pattern, of blues and greys in straight lines.

Yavuz in Istambul in April 1946

The Cold War

In April 1946, the USS Missouri, cruiser USS Providence, and destroyer USS Power entered Istanbul to return the remains of Turkish ambassador Münir Ertegün and make a sate visit. Yavuz greeted the ships, the ships exchanging courtesy salutes. From 1948, Yavuz was stationed İzmit and Gölcük alternatively. She was decommissioned on 20 December 1950, stricken on 14 November 1954. Turkey joined NATO in 1952 and Yavuz, renamed hull number B70, was offered back to the West German government in 1963; The proposal intended she could be turned into a museum ship, as she was the only ww1 german capital ship of that era and the last surviving battlecruiser in the world. The offer was declined however as the German Government has new priorities. Eventually the ship was sold instead to the company M.K.E. Seyman in 1971 for scrapping, towed to the yard on 7 June 1973. Her hull was completely dismantled in February 1976. At that time only the USS Texas survived from that era.

Specifications (1945 as modernized)

-Displacement: 22,979 t, 25,400 t Fully Loaded

-Dimensions: 186.6 x 30 x 9.2 m (612 x 98 x 30 ft)

-Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 12 boilers 85,000 hp. 29 knots max.

-Range: 4,120 nmi (7,630 km; 4,740 mi) at 14 kn (26 km/h; 16 mph)

-Crew: 1010 +43

-Armour: Belt: 280–100, Barbettes 230, turrets 230, deck 76.2–25.4, CT 350 mm

-Armament: 10 × 280 mm, 8 × 150 mm, 8 × 88 mm AA, 22 x 40 mm AA, 24 x 2

mm AA

Read More

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1905-1921

Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.

Barlas, D. Lek; Güvenç, Serhat (2002). “To Build a Navy with the Help of Adversary: Italian-Turkish Naval Arms Trade, 1929–32

Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War.

Brice, Martin H. (1969). S.M.S. Goeben/T.N.S. Yavuz: The Oldest Dreadnought in Existence

Campbell, N. J. M. (1978). Battle Cruisers. Warship Special. 1.

Güvenç, Serhat; Barlas, Dilek (2003). “Atatürk’s Navy: Determinants of Turkish Naval Policy, 1923–38

Herwig, Holger H. (1998) [1980]. “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918

Second Hague Convention, Section 13

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moltke-class_battlecruiser

Rendition of the Yavuz Sultan Selim in 1914

Rendition profile of the Yavuz in 1945

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign