Cuniberti’s cruisers

The San Giorgio class were a counterpoint to the previous unsatisfactory Pisa class. The latter impressed enough the Greeks however to become the Giorgios Averoff, flagship of the navy, with a very long career. Engineer Edoardo Masdea was entrusted with improving the design, but on the same hull, to ease construction and speed.

A bit of context: Before Pisa, the last armoured cruisers deployed by Italy were also among the most successful, but they dated back ten years (1896) and naval tech went fast in between. The export successes of the Garibaldi class kept the yards busy, so much so that construction of replacement took more than expected. In between, naval circles discussed the next generation of armoured cruisers, and among them, Vittorio Cuniberti was one of the most influential thinker.

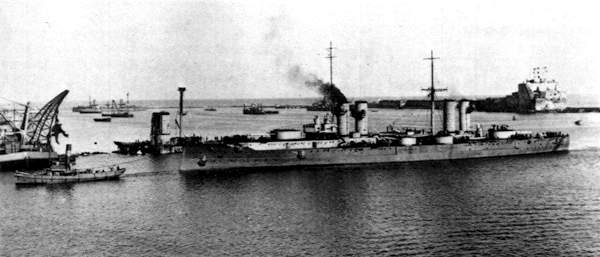

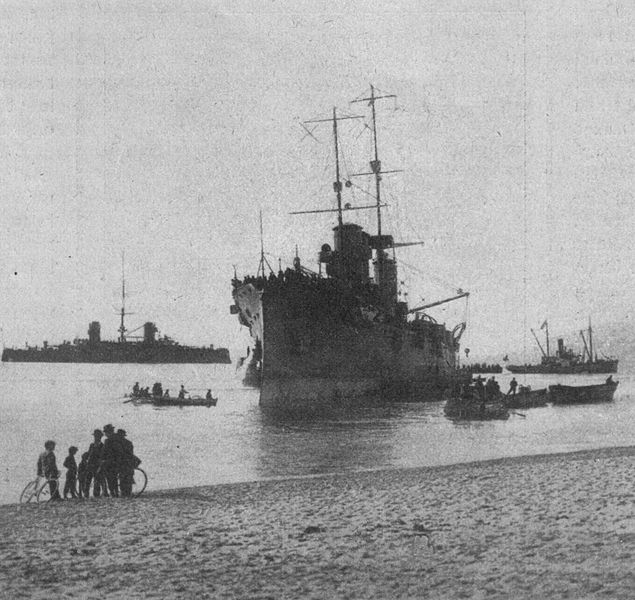

San Marco in Brindisi

About Vittorio Cuniberti

About Vittorio Cuniberti

Born in Turin, Cuniberti joined the Genio Navale in 1878, rose through the ranks as Major general in 1910. He was also a friend and close collaborator of Benedetto Brin, and both worked in 1899 on the Regina Elena-class battleships. To this day, he is best known for an article on Jane’s Fighting Ships, edition 1903, advocating the concept of “all-big-gun” fighting ship. He envisaged a “colossus” with just one gun caliber, preferably 12 inch, although he also argued that an armored cruiser with the same principle and only 10-in caliber would be a very serious proposition. He also made clear a 12-inch proof protection was unavoidable, while small calibre would have no effect on his design.

Ideally, he wanted twelve large caliber guns, to offer a 3x advantage on any battleship of the time. He also dreamed that a full squadron of six “colossi” would rule out any fleet, even three times its number, and that his proposition could only fit a “navy at the same time most potent and very rich” (so the Royal Navy, German or French navies). He would propose it, but without illusions, to the Italian government, later declined for budgetary reasons, but the latter allowed Cuniberti to post hi concept in Jane’s Fighting Ships.

Published before the Battle of Tsushima which vindicated his ideas, the article nevertheless had a tremendous influence in all admiralties. In particular at that time, a certain John Fisher, worried about the rapid rise of the Hochseeflotte. He stated himself later that Cuniberti’s dream battleship was “tailored for the Royal Navy”. One one hand, the Empire needed a wide fleet to protect it, a task current capital ships could not do, unless replaced in the Home Fleet by a “cheaper” alternative (taking the place of three). It appealed to the parliament, and was able to give an edge on the Kaiserliche Marine. In the end, Admiral Sir John Fisher worked on the HMS Dreadnought with great fervor, adding many of his own ideas, notably parsons turbines, also quite a revolution. Launched in 1906, HMS Dreadnought would change naval history.

Plans were thus definitively established while the construction had already been started at Castellamare di Stabia in July 1905, then in January 1907 for the second, when the hold was free. This process saved time. The two ships were launched in July and December 1908, accepted in service by July 1910 and February 1911. Their main innovation was to raise their forward deck by a level, in order to improve seaworthiness. Compartimentation, but also redistributed machinery spaces improved ASW passive protectuon, also giving them two distinctive pairs of funnels, lowered after the tests. They looked like the Dante Aligheri from afar.

Design of the San Giorgio class

Propulsion of the San Giorgio class

The two armoured cruisers were designed for a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph), but varied between ships as both tested different machinery types for evaluation. San Giorgio had two shafts mated on TE steam engines and Blechynden boilers inspired by the previous Pisa class. They were rated for 19,500-indicated-horsepower (14,500 kW). San Marco however had four shafts mated to license-built Parsons steam turbines for the first time in the Regia Marina. They were fed by Babcock & Wilcox mixed-fired boilers (coal/oil), working at 210 psi (1,448 kPa; 15 kgf/cm2). Total output was superior, 23,000 shp (17,000 kW), but on paper both ships were specified to reach their design speed of 23 knots, San Giorgio reaching 23.2 knots, San Marco a bit faster at 23.75 knots in sea trials.

The difference was mire about consumption: San Marco’s turbines were gluttons, providing a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) or 2,480 at 21.25 knots while for San Giorgio these figures were 6,270 nm and 2,640 nm respectively. This posed a problem if the were intended to operate together, in the same unit, as often in the Regia Marina.

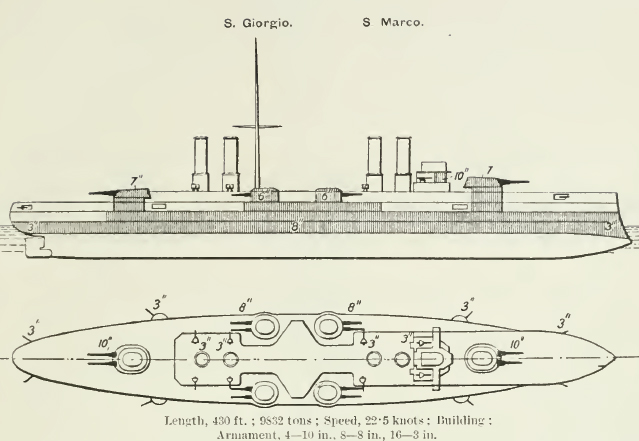

Armament of the San Giorgio and San Marco

Main armament: Four Cannone da 254mm/45 A Modello 1907 in twin turrets for and aft, electrically powered. They had an arc of fire of 260° while the main 10.0 in guns fired 204.1 to 226.8-kilogram (450–500 lb) armor-piercing (AP) shell at 870 meters per second (2,850 ft/s) in muzzle velocity. Their mount had a maximum elevation of +25°, allowing a theoretical range of 25,000 meters (27,000 yd).

Secondary armament:

Both armoured cruisers had four twin turrets on the broadside, eight Cannone da 190/45 A Modello 1908 in all, in electrically powered turrets. They were placed amidships. They had a reduced arc of fire of 160°, and the modello 1908 were licenced copies of the Armstrong Whitworth 7.5 in model which fired the same 90.9-kilogram (200 lb) AP shell at 864–892 m/s (2,835–2,927 ft/s). The mounts also elevated +25° roviding a range of 22,000 meters (24,000 yd), so only three yards shy of the main guns. It was obvious that the main and secondary guns were intended to fire at the same time on the same target, inspired by Cuniberti’s principle of 12 heavy guns. But instead of six twin turrets with 10 in guns, which would have been quite heavy, 8-in guns were chosen instead to fit on the broadsides. The only problem was the relatively close size of the water plumes, creating some confusion for the spotters. A common problem for these “semi-dreadnought” generation of ships in 1905-1909.

Tertiary armament:

The two San Giorgios were provided 18 quick-firing (QF) 76 mm/40 (3.0 in) guns. Eight were mounted in hull’s embrasures and the other half higher up in the superstructure. To complete these, both cruisers had a pair of QF 40-caliber 47 mm (1.9 in) guns, used also as saluting guns. As usual at that tie, torped tubes were also provided, three submerged 450 mm (17.7 in) models.

Protection of the San Giorgio class

Apart from the interior layout used on the Pisa, and extra compartimentation for the machinery, there was no significant improvement. The armored belt had 200 mm (7.9 in) thick plates amidships, reduced on both ends to 80 mm (3.1 in). It was 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) high, including 1.5 m below the waterline o stop torpedoes. The armored deck was composed of 50 mm (2.0 in) thick plates for the flat section, with possibly sloped sides. The conning tower had 254 mm (10 inches) thick walls. The main gun turrets’s faces were also covered with sloped 10-in armour, 200 mm on the sides, and the secondary turrets had 160 mm (6.3 in) sides and faces.

Brassey’s naval annual 1921 San Giorgio scheme

Specifications

Conway’s rendition of the San Giorgio (via navypedia)

Displacement: 10,167 t, 11,300 t. FL

Dimensions: 140.8 x 21 x 7.3 m

Propulsion: 2 shaft VTE, 14 mixed boilers Blechynden, 19,600 hp. and 23.2 knots

Protection: Belt 200, Deck 50, Blockhouse 254, Turrets 200-160 mm;

Crew: 705.

Armament: 4 x 254 mm (2×2), 8 x 190 mm (4×2), 18 x 76 mm, 2 x 47 mm, 4 ML, 3 TLT 450 mm Sub.

Author’s illustration of the San Giorgio

Read More/Src

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-1921

http://www.naviearmatori.net/albums/userpics/14665/SAN_GIORGIO__3__a.jpg

Attilio, Dagnino (December 1911). “Italy’s First Turbine-Driven Cruiser, the San Marco”.:

Beehler, William Henry (1913). History of the Italian-Turkish War

Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini’s Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II.

Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley

Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I.

Marchese, Giuseppe (February 1996). “La Posta Militare della Marina Italiana 8^ puntata”.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two

“San Giorgio: Incrociatore corazzato”. Storia e Cultura: La nostra Storia: Almanacco storico navale

Sicurezza, Renato. “Il Regio Incrociatore Corazzato San Giorgio”.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918

Stephenson, Charles (2014). A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912

A career spanning 30 years and five wars

These two units participated in the Balkan conflict and then in the Great War. In 1916, they were fitted with a front mast while their light artillery increased to ten standard 76 mm and six 76 mm AA in replacement of standard ones, and one torpedo tube was removed. San Giorgio participated at least to five wars: Italo-Turkish, WW1, Colonial wars, Spanish Civil war, and WW2. As per the Washington’s treaty limitations regulations, both were at least partially disarmed, with some armour removed and the powerplant downgraded. San Giorgio was mostly famous for her rôle in the siege of Torbrouk.

San Giorgio

Prewar career

San Giorgio stranded in 1913

San Giorgio was named after Saint George, the patron saint of Genoa. She was built at Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia in July 1910 but ran aground on a reef off Naples-Posillipo a month after, badly damaged. She took 4,369 tonnes of seawater flooding, her boiler rooms, magazines and lower compartments were completely submerged. To refloat her, ships and barges with cranes came to removed her guns, turrets, conning tower and even paet of her armour. Then divers installed pumps and injected air into the hull. She was ultimately refloated and conducted for repairs in the nearest yard, and was still so during the Italo-Turkish War. However she left the yard to join the fleet in June 1912. By February 1913, she made a cruise in the Aegean Sea, stopping at Salonica and ran aground again in November 1913 in the Strait of Messina, fortunately she had only light damage but her captain was dismissed.

San Giorgio firing during the Italo-Turkish war

Wartime career

On 23 May 1915, Italy was at war and the armoured cruiser was in Brindisi. The Austro-Hungarian fleet made a night shelling raid on the coast, notably Ancona, and they will return in mid-June, but Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel had San Giorgio and other cruisers at Brindisi, and deployed them as a deterrent. They departed for Venice, and during the trip, Amalfi was sunk by a submarine, but this did not prevented San Giorgio to shell Durazzo on 2 October 1918, notably sinking a Austro-Hungarian cargo and and damaged two more. This was her only significant participation to the war, as she was kept safely in Venice for most of the conflict.

Interwar career

San Giorgio was the flagship of the Eastern Squadron until 16 July 1921 (Istanbul), relieved by the scout cruiser Brindisi, and departed for Far East. In 1924 she carried Crown Prince Umberto on his tour of South America, acting as the royal yacht. She departed Naples on 1 July 1924 but because of the second Tenente revolt in Brazil, she was diverted to Argentina, Buenos Aires on 6 August and three days later her crew participated in a military parade. She also visited Chile, then sailed to Montevideo, Uruguay, arriving on 5 September, and then Bahia in Brazil, and back home 18 September.

She was assigned to the Divisione Navale del Mar Rosso e dell’Oceano Indiano (Read Sea and Indian Ocean) from 1925. There, she covered Italian operations in Somaliland. From 1926 to From 1930, there was nothing notable. She was based in Pola as a training ship for cadets. In 1936, she was sent to Spain to protected Italian interests due to the Civil War. She went back home in 1937 and the admiralty decided to modernize her. She she was reconstructed until 1938 as a dedicated training ship for naval cadets at the Arsenale di La Spezia, according to the Washington treaty limitations:

Reconstruction 1936-38

First, six boilers were removed, remaining eight were converted to fuel oil. Top speed fell to 16–17 knots and the two pairs of funnels was truncated into a single one. The old 76 mm/40 guns were replaced by eight brand new 100 mm/47 in four twin turrets, placed either side of the funnels. Torpedo tubes were removed and a light AA was added, six Breda 37mm/54 in single mounts, and twelve Breda 20 mm Modello 35 autocannons in twin mounts. A t last, she received two twin 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Breda Modello 31 heavy machine guns. Superstructures were revised as well as the interior compartimentation to house the cadets ad their instructors.

San Giorgio after reconstruction in 1938 – Conway’s

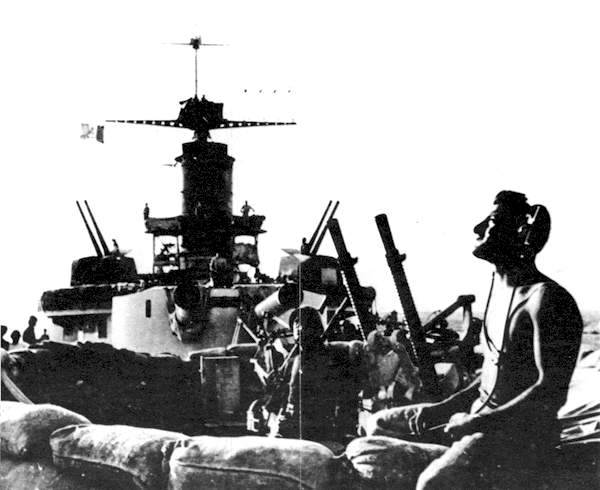

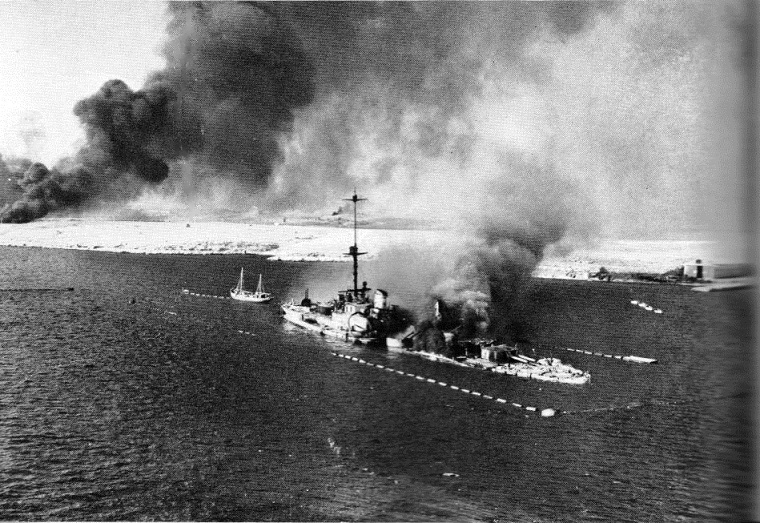

When the war broke our, Italy envisioned its priorities, among others grouping the Regia Marina to face the French Navy. This urged the use of less important vessels to guard colonial outpists and less important sectors. Thus it was decided to send San Giorgio to Tobruk in early May 1940, acting as a floating AA battery to protect the harbour. For this, a fifth 100mm/47 gun turret was added on the forecastle, plus five more twin 13.2 mm Breda HMGs. Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June and the former attacked Tobruk, notably with a British naval force comprising the light cruisers Gloucester and Liverpool. They shelled the port and soon targeted San Giorgio. Damage was light, but the Royal Air Force then intervened, and Blenheim bombers from three Squadrons bombed Tobruk and one fell on San Giorgio. Damage was more serious but the ship kept its offensive capability. On 19 June, the submarine HMS Parthian entered Tobrouk and fired two torpedoes at San Giorgio, which however detonated before hitting the ship, making the British wonder if the Italians had submerged defenses rather than malfunctions. And it was the case. As in WW1, San Giorgio was mounted her torpedo nets, which protected her for no less than 39 torpedoes, most launched by Swordfish planes.

After having bad luck in her past, San Giorgio became the reverse. This was not to last however.

San Giorgio in May 1940

San Giorgio was a crucial part of anti-aircraft defences of Tobruk, bringing a density of fire that was appreciable to deter British air raids. Between June 1940 and January 1941, these attacks went one and on the long run, San Giorgio’s crew would proudly claim 47 enemy aircraft down or damaged. Eventually as Operation Compass took place, Commonwealth troops besieged Tobruk in January 1941. San Giorgio still had her main guns, and they could be turned on approaching British tanks, however she was not deployed as AA cover was preferred, but she was seaworthy and as the fall of Tobruk became evident, local naval commander Admiral Massimiliano Vietina requested fro Supermarina in Rome the ship to leave, avoiding destruction or capture. However the C-in-C in Libya, marshal Rodolfo Graziani, opposed it, notably to maintain morale, and this was endorsed by the Italian Supreme Command.

The AA crew of RN san Giorgio at Tobrouk in 1941

This decision sealed the fat of San Giorgio in Tobruk. She will fire on the attacking land forces until the city fell and her magazines were empty. On January 22 at noon, the armoured cruiser’s crew disembarked and a formed small scuttling party (Captain Stefano Pugliese). They blew up San Giorgio magazines and were soon taken prisoner, but a few which managed to escape on a fishing boat with San Giorgio’s war flag. At Rome, the crew and the ship was awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare and her actions during the siege of Tobruk were well publicized by the propaganda. Her hulk was recommissioned by the RN in March 1943 (HMS St Giorgio) as a stationary repair ship until 1945 and her was refloated in 1952, sinking on her way to Italy for demolition.

Italian cruiser San Giorgio scuttled at Tobruk 1941

San Marco

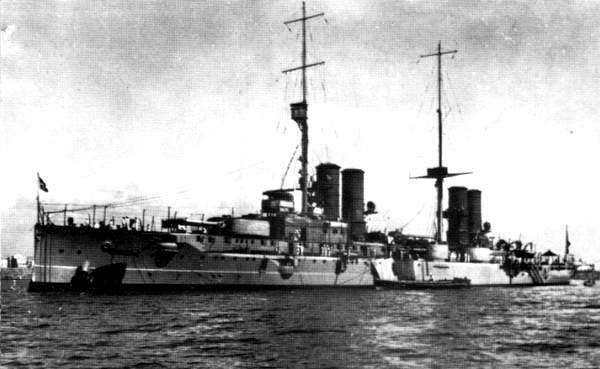

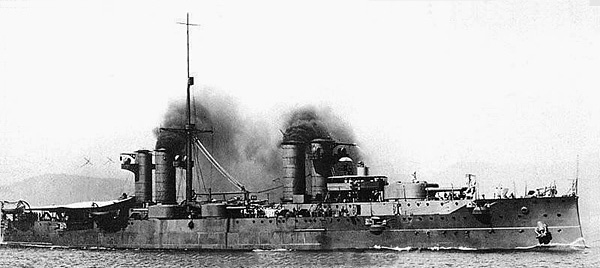

San Marco as built in 1911

San Marco was named after the famous Patron Saint of Venice. She was built at Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia (Bay of Naples), completed on 7 February 1911. She soon took part in the Italo-Turkish War, starting on 29 September. San Marco was in the 2nd Division, 1st Squadron and was assigned on 1 October, escorting Italian transports bound to Derna in Libya in October with RN Napoli and the older armoured cruisers Pisa and Amalfi.

When Pisa shelled the city’s barracks and a fort, then a truce was sent in, but repelled by a volley of fire and San Marco and the other cruisers opened fire, reducing the town to rubbles in 30 minutes, and covering later a landing party, after shelling beach for two hours. She went on supporting troops at Benghazi in December 1911 and by mid-April 1912 was in the Aegean Sea, attempting to lure out the Ottoman fleet without success, then shelling the Dardanelles. By May 1912, San Marco supported landings on Rhodes and was back home on 20 September.

San Marco at Brindisi on 13 December 1916

San Marco evaluated shipboard seaplanes operations in 1914, based at Brindisi the next year in May. After the night raid on Ancona and by June, she was sent by Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel in Venice, but the ships became mostly inactive after the loss of Amalfi. San Marco however took part in the bombardment of Durazzo on 2 October 1918.

On 21 September 1923, San Marco carried to Taranto the corpses of the Boundary Commission killed on Corfu on 27 August and in October she carried back troops from Corfu to Brindisi. On 16 March 1924, she saluted King Victor Emmanuel III in Fiume, taking part in a commemoration of its annexation by Italy and later escorted Crown Prince Umberto (onboard her sister ship San Giorgio) during his South American tour.

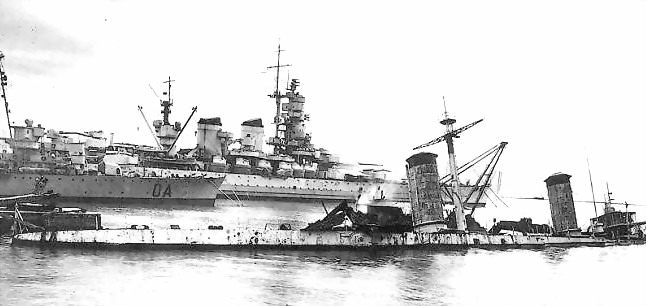

As for the Washington’s treaty limitations she was disarmed and converted into a radio-controlled target ship in 1931–1935. She had only four oil-burning Thornycroft boilers (top speed 18 knots, 13,000 shp (9,700 kW)) and started her new career. During a naval review for Adolf Hitler in the Bay of Naples in 1938, she was used as a target by RN Fiume and Zara. During WW2 she remain in this state, but was captured by the Germans after the Italian capitulation when occupying La Spezia in September 1943. She was later sunk in the harbor as an obstruction and was formally stricken from the List on 27 February 1947, BU in 1949.

San Marco in La Spezia in 1945

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign