The Bahia class were scout cruisers built for Brazil by British yard Armstrong Whitworth on a modified Adventure-class scout cruisers. Three were initially ordered as part of the largest Brazilian naval plan so far (along with the Rio de Janeiro Battleships, destroyers and a support ship). Bahia, Rio Grande do Sul, and Ceara were named after states of Brazil. The third was later cancelled, but attention was paid to the engines and they ended as the world’s fastest when commissioned, also first Brazilian ships with steam turbines. The interwar saw them modernized with Brown–Curtis turbines and new Thornycroft boilers, all oil-burning and gaining three funnels, as well as their armament modified with Madsen AA guns Hotchkiss LMGs as well twin torpedo tubes added. Both took part in WW2 as Brazil joined the allies on August 31, 1942. As the battle of the Atlantic was at its hottest, both cruisers served as convoy escort. Bahia was lost by accident on 4 July 1945, her sister was scrapped in 1948.

Development: The 1904 naval programme

In 1902, the Chile-Argentinian naval arms race had been stopped by the British-arbitrated Pacts of May, as the Empire feared both of his suppliers (one for guano, used for cordite, the other for meat) went into bankruptcy and even cause a global economic crisis. All this time, the third traditional major naval power of South America, grew worried of these developments, as both Chile and Argentina were sizing up their race from cruisers to armoured cruisers and now on the verge of ordering battleships (for Chile). Fearing to be declassed with her 1880s ironclads, the Riachuelo class, and a generally decades old navy, Brazil decided to vote in parliament the largest naval plan in its history.

This was the 1904 naval building program, barely two years after the race ended. This naval plan, when announced, caused shockwaves across the globe, it concerned the two Minas Geraes-class dreadnoughts (first in America), ten Pará-class destroyers (Based on the River class), three submarines and a submarine tender to go with these. Submarines were also new in South America and a powerful deterrence. To screen for the dreadnought and perform various missions, including attacking the trade of its neighbours, three scout cruisers were also ordered, a brand new concept at the time.

It should be precised here that the older Chilean and Argentinian Navies had unprotected, protected and armoured cruisers of older generations, and lacked fast cruisers. Chile was never in an economical position to regain the advantage in cruisers, ordering two dreadnoughts just before WW1, and Argentina had to wait for the interwar to procure three cruisers. In answer, Brazil had to modernized its own.

The 1904 naval plan raised eyebrows at Downing street for good reasons, because it as likely that the new Brazilian battleships would trigger an answer by both Argentina and Chile, and that’s exactly what they did as soon as the announcement was made. Argentina, despite the obvious financial burden of its past orders, chose USA to built its own Rivadavia class and Chile its Almirante Latorre class. This “luxury” of building such ships was largely due to very favourable market shares for their respective exports, but this was not to last. In the end, the cost of this second naval arms race prevented a true modernization of these navies in the interwar.

Construction

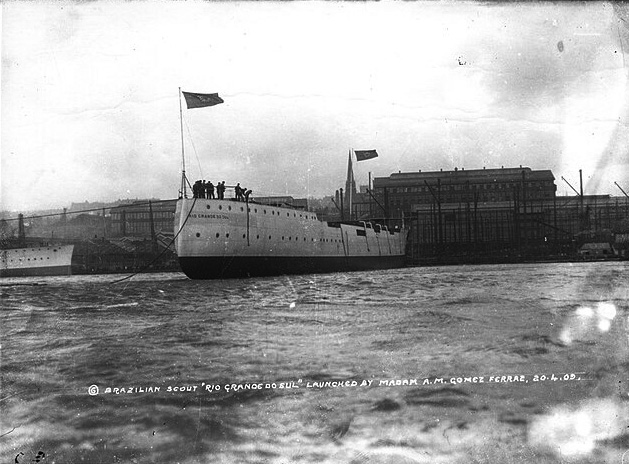

These three cruisers, ordered to Arsmtrong Withworth, were heavily based on the British Adventure-class scout cruisers. However during negotiations, the third, Ceara, was cancelled, and the name went to the submarine tender. Bahia had her keel laid on 19 August 1907 at Elswick Yard in Newcastle upon Tyne yard, Rio Grande do Sul on 30 August 1907, and went on for a year and a half until launched both in 1909. They were completed and commissioned in 1910. Receiving a greenlight, the chief engineer worked out both the engine’s configuration, and hull shape optimisation to reach the greatest speed achievable and indeed, Bahia managed to be on trials, the fastest cruisers in the world as they were commissioned at 27+ knots. Having steam turbines was also new for Brazil, its destroyers were indeed provided with classic VTE engines instead. Both were supposed to work in conjunction, each cruiser being able to act as flotilla leader for 5 destroyers.

Design of the Bahia class

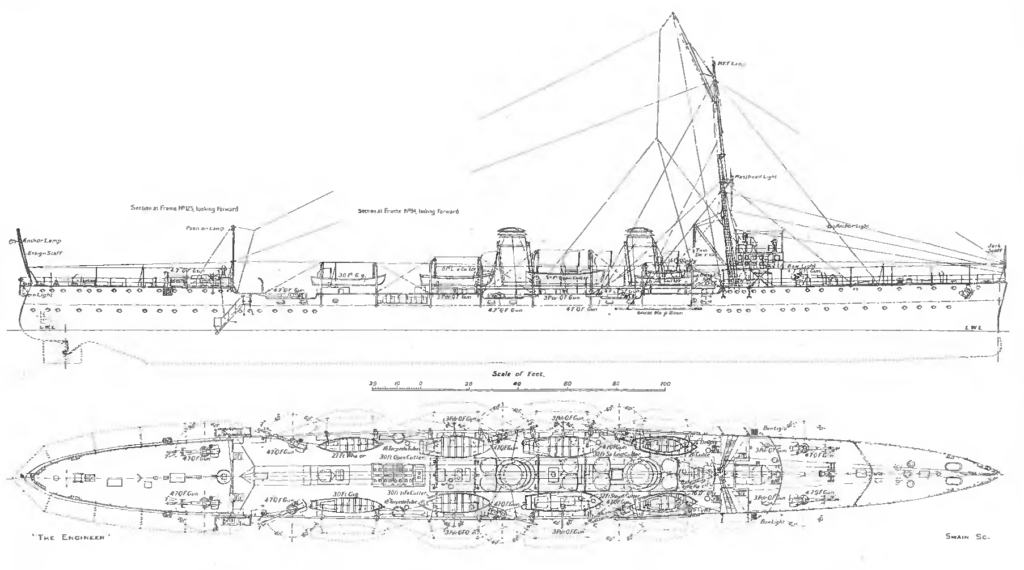

Line drawing published in the review “the engineer”.

The Bahia class were very closely related to the Adventure-class scout cruisers with a similar displacement of 3,100 tonnes (3,100 long tons) for 122.38 m (401 ft 6 in) in length overall, a moderate clipper bow, and 115.82 m (380 ft) between perpendiculars. The beam measured between 11.89 and 11.91 m (39 ft – 39 ft 1 in) depended on the section, and the draft was moderate (which also participated in speed gain) at 3.81 m (12 ft 6 in) forward and 4.75 m (15 ft 7 in) amidships, 4.42 m (14 ft 6 in) aft, which in part affected stability.

They were typical of the time for scouts, and still with some older percs shared by older scouts (still fitted also with ram bows) like a raised poop deck, two low, raked funnels and a single, also raked foremast. The uniformed artillery, not protected, was spread between fore and aft pairs, and broadside sponsoned positions. There was a small conning tower and bridge build above, relatively low, but with generous wings with light guns posts. They had two light projectors on platforms, a small aft pole mast for wireless telegraphic cables to end, and eight utility boats for their crew of 320 officers and sailors. Later in their career, this would rise to 370.

Illustration for the Elstwick booklet by Oscar Parkes. Vickers would later pitch the Bahia design to the Ottoman Navy in 1912, but nothing came of it prior to the outbreak of war.

Propulsion

The Bahia class cruisers had three (presumably) propellers shafts (middle driven by a single turbine for cruising), driven by five Parsons steam turbines, fed in turn by ten Yarrow boilers. They burned coal, and the latter in normal load could be stored up to 150t, ported to 650 t (640 long tons) if needed by filling all adjacent compartments. Design speed published by the yard was 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph) with the hope they would surpass it, and indeed Bahia on sea trials managed to reach 27.016 knots (50.034 km/h), her sister was just a bit slower at xxx. As contracted their range was 1,400 nautical miles (2,600 km; 1,600 mi) at 23.5 knots (43.5 km/h; 27.0 mph) or 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km; 4,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Protection

Being scout cruisers, this was limited to the vitals, an internal, waterline, turtleback deck 19 mm (0.75 in) thick on the flat section and up to 31 mm (1.22 in) on the slopesn pluging below the waterline and acting as indirect belt. There was a Conning tower with walls 76 mm (3.0 in) in thickness. There was however heavy compartmentation underwater, with a full separation of the engine and boilers into separate rooms, and subdivisions on both sides full with coal. There was no double hull however.

Armament

The armament was consistent with scout cruisers at the time, uniform with QF guns to deal with enemy destroyers.

120mm/50 Armstrong CC

First designed in the 1880s the famous QF 4.7-inch Mk I – IV naval gun was a very common RN secopndary guns on capital ship and main gun on cruisers, before the 6-in caliber became the norm in WW1.

They were placed, two in pairs on both the forecastle and poop deck, three either side, the two outer pieces on sponsons. There was room for two more if replacing the torpedo tubes.

Barrel & breech weighted 4,704 lb (Mk IV), 189-inch bore (40 cal, 4.724 inches). It worked with a single motion interrupted screw, fired Separate loading QF HE 45 pounds (20.41 kg) rounds at 2,150 feet per second (660 m/s), 5–6 rpm, +20° elevation, 10,000 yards (9,100 m) range. It is not known if they received in the interwar a new 24° mount.

47mm/40 Hotchkiss QF

Classic unshielded QF 3-pounder, six of them placed along the ship, two on the bridge’s wings, and probably the four others along the lower deck.

They fired a fixed QF 47 × 376 mm R 3 kg (6.6 lb)/1.5 kg (3.3 lb) round at 571 m/s (1,870 ft/s), up to 30 rpm and 5.9 km (3.7 mi) at +20°. Gradually replaced, 2 interwar, 4 in WW2.

The location of the Madsen guns, and in WW2 or the Oerliklon guns is uncertain due to the lack of documentation and close in photos.

21-in Torpedo Tubes

Not much to say, these were single rotatable tubes with a limited traverse aft admiships. No information about the number of spare torpedoes or the model. Replaced in the intwerwar by twin tubes, against, model or mount unknown.

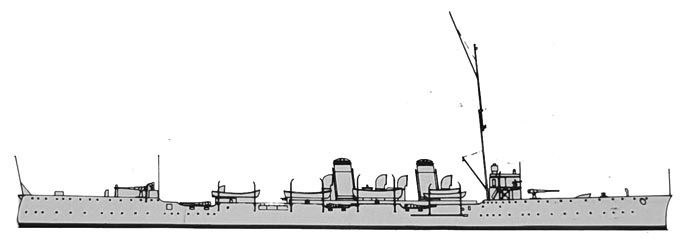

conway’s profile

⚙ specifications as built |

|

| Displacement | 3,100 t (3,100 long tons), assumed standard |

| Dimensions | 122.38 x 11.91 x 4.75m (401 ft 6 in x 39 ft 1 in x 15.6 ft) |

| Propulsion | 5 Parsons turbines, 10 Yarrow boilers |

| Speed | 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph) as designed |

| Range | 150-650t (720 short tons) coal, 1,400/23.5 kts, 3,500 nmi/10 kts |

| Armament | 10× 120 mm (4.7 in)/50, 6× 47 mm (1.9 in)/50, 2× 457 mm (18 in) TTs |

| Protection | Deck 19-31 mm (0.75 in), CT 76 mm (3.0 in) |

| Crew | 320 |

Interwar modernization of the Bahia class

From 1925, it was envisioned a significant modernization program for the ageing scouts. The five turbines were replaced by three Brown–Curtiss turbine, one for each shaft, and six Thornycroft oil-burning boilers so two per turbines. They were all placed in succession, so needed the addition of a third funnel after truncating the exhausts. The former coal bunkers could hold more oil after conversion, and to this was added extra space gained after the downsizing of the new boilers, far more compact. In the end these efforts led to a useful 588,120 metric liters (155,360 US gallons) of fuel oil and not only this new powerplant help them regain an extra two knots at 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) based on 22,000 hp but their range was almost doubled. The eight boats under davits were removed, the superstructure was redone and modernized to clear the decks. The bridge was modernized also, as the rangefinders and radio communication systems.

Armament wise, the greatest addition was the replacement of the single tubes amdiships for twin torpedo tubes banks of the same 533 mm model (21 in), the removal of two 47mm/40 guns and addition instead of three 20.1 mm (0.79 in) Madsen guns for AA defence and a single 7 mm (0.28 in) Hotchkiss machine gun.

WW2 modernization of the Bahia class

Bahia in 1944, probably with a US inspired Measure xxxx,

The fact that Brazil entered the war in 1942 urged the need of making both cruisers more useful for their new role. They were in fact modernized twice, in 1942 and 1944. Reports showed that apparently the two remaining 47 mm (1.9 in) guns were replaced with 76 mm (3.0 in) L/23 AA guns, and the Madsen guns replaced with seven Oerlikon 20 mm cannons, all single, and assorted with a dedicated new director provided from the US. Also they gained two depth charge tracks more importantly for their intended escort role, despite having a poop design ill-adapted for this. In the end, they also adopted improved range-finders for her now ageing 120 mm (4.7 in) guns. A radar (probably US SC type) was also fitted, probably in 1944 and there are doubts regarding the dating for the installation of the sonar, which if the depht charges were added in 1942, so used in the 10 July attack, a swap was done with a better sonar on Bahia in 1944. Navypedia states no date either, but that all four remaining 47mm/40 guns were removed and that the Oerlikon guns were either six or eight 20mm/70 Mk 4 models.

Author’s profile, in 1944.

⚙ specifications 1944 |

|

| Displacement | Probably 3500t |

| Propulsion | 3 Brown Curtiss ST, 6 Thornycroft oil-burning boilers |

| Speed | 28 kts |

| Range | c6600 nm/10kts |

| Armament | 10x 120mm, 8x 20mm, 2×2 TTs, 2 DCR |

| Sensors | DC radar, Sonar |

| Crew | 370 |

The Bahia class in service

Bahia (1910-1945)

Bahia (1910-1945)

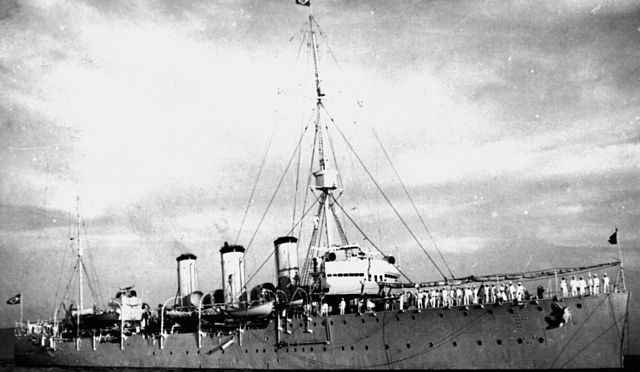

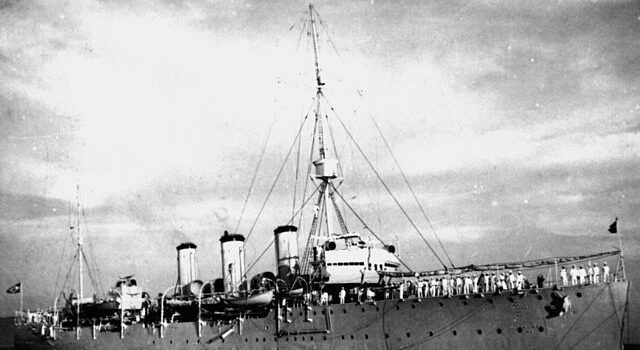

Bahia as built; note the colors, pale grey or white hull and canvas sand superstructures, wooden bridge. They were repainted all grey in the interwar and camouflaged in WW2 following a US scheme, see later.

A long fitting out had Bahia’s completion pushed to 2 March 1910, after which she departed for Brazil, arriving in Recife on 6 May, commissioned on the 21. However her early career was soon disturbed by a major event, the revolt of the Lash due to a severe recession, economic hardships and racism in Brazilian armed forces as well as severe discipline which led to the “Revolta da Chibata” mutiny among sailors, especially on the two battleships. This started on Minas Geraes, spread to São Paulo, Deodoro, and Bahia. The crew murdered one of their officers, but daily drills were conducted and all liquor was thrown overboard. Meanwhile, crews of torpedo boats remained loyal and army troops moved to the presidential palace, but the harbor defensers were sympathetic to the mutineers adn the capital, to avoid a naval bombardment, ceded. The National Congress agreed to the demands (abolition of flogging, better food and living conditions, amnesty, official pardon) so the revoled ended after a few days on 26 November and control of Bahia was handed back to the navy.

During World War I

During World War I, neutrality did not prevented the Brazilian Navy to patrol the South Atlantic alongside entente naval units, but Bahia and her sister stayed carefully in territorial waters. Bahia and Rio Grande do Sul were based in Santos already on August 1914 when the German raider Bremen arrived off this port, expecting to prey on British merchant ships. On 26 October 1917 Brazil joined the Entente. On 21 December were asked by the British to despatch a small naval force and comb the Atlantic in search of U-Boats. On 30 January 1918, Bahia became its flagship. The unit was called the “Divisão Naval em Operações de Guerra” (DNOG) under Rear Admiral Pedro Max Fernando Frontin. Alongside her sister, she sailed woth the Pará-class destroyers Piauí, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte and Santa Catarina, as well as the tender Belmonte, and tugboat Laurindo Pita.

During World War I, neutrality did not prevented the Brazilian Navy to patrol the South Atlantic alongside entente naval units, but Bahia and her sister stayed carefully in territorial waters. Bahia and Rio Grande do Sul were based in Santos already on August 1914 when the German raider Bremen arrived off this port, expecting to prey on British merchant ships. On 26 October 1917 Brazil joined the Entente. On 21 December were asked by the British to despatch a small naval force and comb the Atlantic in search of U-Boats. On 30 January 1918, Bahia became its flagship. The unit was called the “Divisão Naval em Operações de Guerra” (DNOG) under Rear Admiral Pedro Max Fernando Frontin. Alongside her sister, she sailed woth the Pará-class destroyers Piauí, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte and Santa Catarina, as well as the tender Belmonte, and tugboat Laurindo Pita.

The DNOG patrolled off British controlled Sierra Leone in July. They were supported by the Belmonte which made numerous supply trips of coal and water and arrived off Freetown on 9 August, stayed until 23 August, then moved to Dakar. Belmonte underway narrowly escape torpedoing. The U-boat was chased off by gunfire by Rio Grande do Norte but authorities later claimed to have sunk the submarine. In Dakar from 26 August, the DNOG patrolled between Cape Verde and Gibraltar, believed to be a “waiting area” for ambushing U-boats. They also looked for minefields laid by minelayer subs. However at some point, Bahia and Rio Grande do Sul developed condensers problems due to the tropical climate.

Frm early September 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic started aboard Bahia, and spread to the other ships, quarantined for for seven weeks with up to 95% of the crews infected, 103 died, and 250 died later in Brazil. On 3 November, Bahia and three destroyers were ordered to Gibraltar to start Mediterranean operations from 10 November, escorted by the DD USS Israel, until the Armistice.

Interwar:

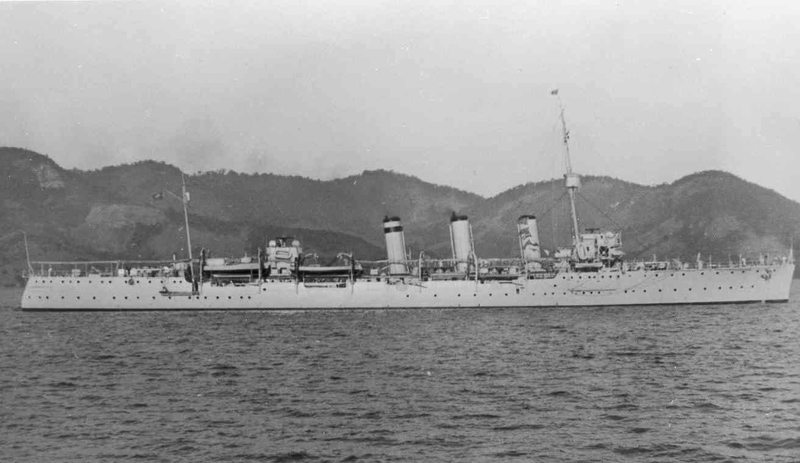

Bahia, modernized

By early 1919, Bahia and four destroyers visited Portsmouth, then Cherbourg on 15 February under command of Admiral Pedro Max Fernando Frontin, and carried to Maritime Prefect to Toulon, Frontin leaving to journey to Paris. The DNOG was dissolved on 25 August 1919.

Bahia had a major modernization in 1922-24 likely, like her sister as described above. Despite of this, in 1930 The New York Times labelled them as “obsolete”. On 28 June 1926, she visited Philadelphia, for the US sesquicentennial celebrations. Later in December 1928 under command of Heráclito Belford Gomes she escorted the president Júlio Prestes to the United States for an official visiit aboard the ocean liner Almirante Jacequay. Herbert Hoover mer them aboard the cruisers USS Trenton and Marblehead 100 miles (160 km) off Sandy Hook, the bRazilian firing gun salutes. After eight days the presdient caught SS Olympi for France and Bahia, Rio Grande do Sul berthed at Brooklyn Navy Yard with their crew on leave, sailed for home.

Nothing of note but the Revolution of 1930, both cruisers defected with 6 destroyers off the coast of Santa Catarina, under Belford Gomes. In 1932 São Paulo rebelled in the Constitutionalist Revolution and Bahia (under Frigate Captain Lucas Alexandre Boiteux) blockaded the port of Santos. Bahia had a major overhaul in 1934-1935 and by November 1935 with her sister, sailed to Natal, Rio Grande do Norte bringng support in an another rebellion. They sank the rebel steamship Santos.

From 17 to 22 May 1935, they joined the Argentine battleships Rivadavia and Moreno, Almirante Brown, Veinticinco de Mayo, five destroyer to escort the battleship São Paulo, with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas on board to the Río de la Plata and Buenos Aires adn also visit Uruguay president Gabriel Terra for the Pan-American Commercial Conference on 26 May and Chaco War peace conference.

On 2 March 1936, Bahia escorted Veinticinco de Mayo with the Minister RADM Eleazar Videla aboard back to Rio de Janeiro.

Second World War:

Bahia dropping depht charges, seen from Carioca in 1945

Brazil was at war with the axis on 21 August 1942, effective on the 31st, and Bahia started her Atlantic campaign escorting convoys. She covered 101,971 nmi (188,850 km; 117,346 mi) in 358 days, shepherded more than 700 merchant ships. She was modernized twice. On 3 June 1943, Bahia was escorting convoy BT 12 when locating an underwater mine, destroyed by its 20 mm (0.79 in) Madsen gun. On 10 July she had a sonar contact, depth-charged and probably damaged U-199, reported sunk later in the same area off Rio de Janeiro by joint US-Brazilian aircraft. In November 1944, she patrolled with USS Omaha and destroyer escort Gustafson, escorting the troopship General M. C. Meigs with the 4th leg of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force to Italy.

In 1945 she was asked to patrol the Atlantic as rescue ship in European theater, near routes used by military transport aircraft, carrying personnel from Europe to the Pacific. At first she was stationed northeast of Brazil (St Peter-St Paul Archipelago) from 4 July 1945. Crews were busy with AA target practice, when a practice kite towed behind the ship, shot down, accidentally hit the stern depth charges and caused a massive explosion, rocking the powerlant and rupturing all steam pipes and fuel lines, electric cables, knocking out all power. The rear of the ship, completely blasted, saw a massive flooding and Bahia sank in three minutes.

Survivors were stranded there for 4-5 in full exposure but sources vary for their fate. One states 22 were discovered and picked up on 8 July (freighter Balfe) on when Rio Grande do Sul arrived four days after on station to relieve her sister. Official records are 36 rescued, 336 dead. Contemporary claims of hitting a mine of being torpedoed by U-530 remained unsubstantiated but the controversy is not over.

Rio Grande do Sul (1910-1947)

Rio Grande do Sul (1910-1947)

Rio Grande Do Sul in WWI

Rio Grande do Sul was commissioned in May 1910. She spent her prewar years without major incident, in training and maintenance. During the the First World War, she was assigned to the Naval Division with Bahia (see above), patrolling between Dakar, Sierra Leone and Gibraltar. She was hit by the Spabish flu in 1918. She was also modernized in the early 1920s and remained loyal to the government during the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution, taking part in the naval blockade of Santos, as well as shooting down a rebel aircraft (a first for a Brazilian ship).

Rio Grande in the interwar, post-refit

Rio Grande do Sul followed her sister in the Second World War in the newly created Northeast Naval Force, as escort notably towards Italy, with the troopships carrying the Brazilian Expeditionary Force. In July 1945 she arrived on station to relieve her sister but found nothing. She served postwar for a few more years, and was decommissioned in June 1948, sold for BU.

Read More/Src

Books

Campbell, Gardiner, Gray, Randal, ed. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921.

Note: Miramar Ship Index, Poder Naval Online record shows launching dates of 20 January 1909, 20 April 1909. Conway’s and the Brazilian Navy’s official history gave the reverse. Miramar however uses builders’ own records, more accurate.

“Bahia (3º)”. Histórico de Navios; Serviço de Documentação da Marinha

Janes Fighting Ships (2001)

“The Brazilian Navy,” Times (London), 28 December 1909

Friedman, Norman (2012). British Cruisers of the Victorian Era. NIP

“Cruzador Bahia – C 12/C 2”. Navios de Guerra Brasileiros; 1822

Miramar Ship Index.

Serviço de Documentação da Marinha – Histórico de Navios.

Brook, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867 – 1927. Gravesend, Kent, UK: World Ship Society.

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I. Random House 2001

Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America’s Wars: Volume II, The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001.

Links

http://www.navypedia.org/ships/brazil/br_cr_bahia.htm

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign