Austro-Hungarian Navy (1911-1937):

Austro-Hungarian Navy (1911-1937):Tátra, Balaton, Csepel, Lika, Triglav, Orjen. Ersatz: Triglav(ii), Lika(ii), Dukla, Uszok

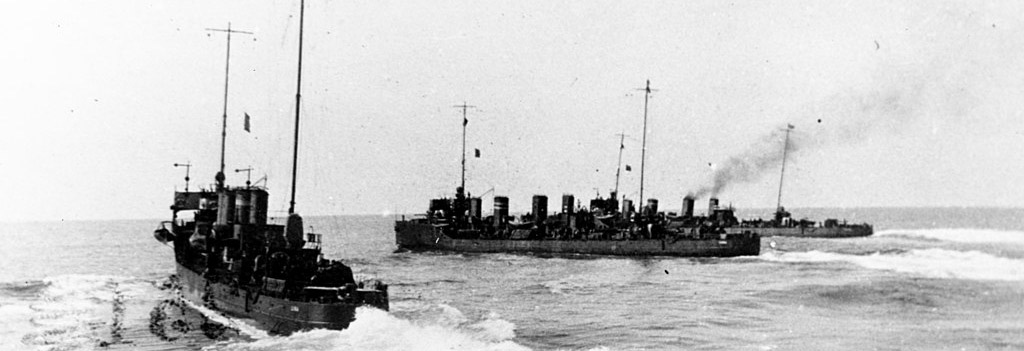

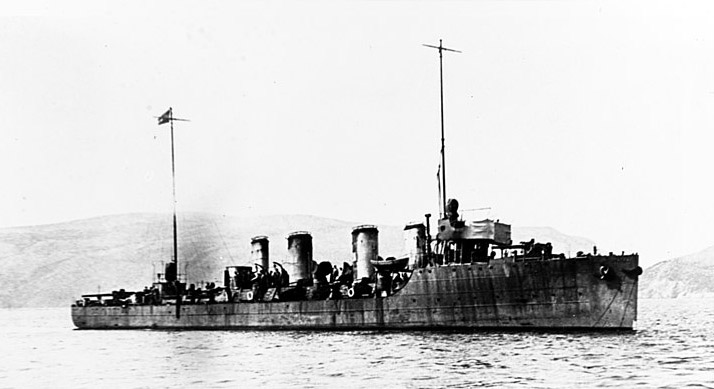

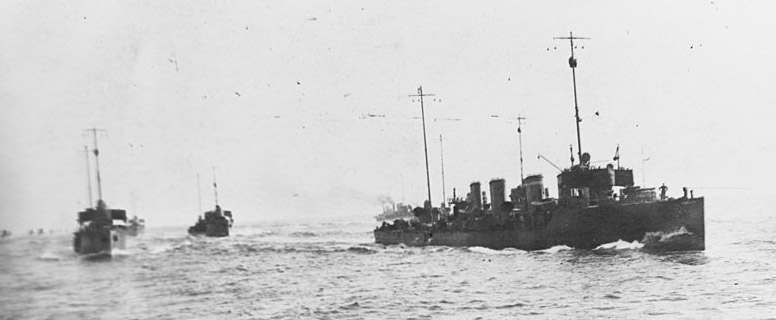

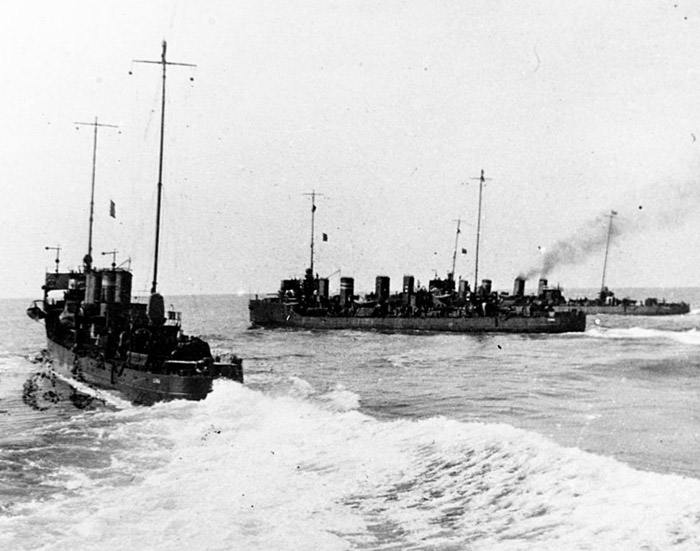

Tátra class destroyers: SMS Tátra, Balaton, Csepel, Lika, Triglav and Orjen were large, new generation Hungarian-built destroyers designed for the Adriatic. They were built in the general context of experimenting with larger destroyers-scouts leaning on light cruisers instead of torpedo-boat derived vessels. Nearby Italians designed in response their own flotilla leaders classed as cruisers scouts (Poerio, Aquila, Mirabello and Leone) for the Adriatic. These six ships built at Ganz-Danubius, Porto Ré and completed in 1913-14 were probably among the most active Austro-Hungarian vessels during WW1. They were followed by the four Ersatz Tatra launched in 1917, and another serie planned when the war ended. All but one survived the war, and ended as war reparation to Italy. #ww1 #austrohungary #austrohungariannavy #tatra #destroyers #adriatic #otrantobarrage

The Tátra class emerged from a tender by the Austrian Naval Administration, for six 800t turbine-powered destroyers with a top speed of 32.5 knots (knots). In addition to local shipyards in Trieste and Fiume as well as AG Vulcan in Stettin were all asked to submit an offer. The Danubius shipyard in the Hungarian half of the empire was awarded the construction contract for political reasons linked to goodwill vote of the naval budget. Porto Ré (Kraljevica) was located south of Fiume (the yard is still in operation).

Construction started by October 1911 and the the commissioning of the last three units of the class accelerated by the start of the war.

By May 28, 1914, six additional destroyers were approved in the 1914/15 naval budget. The contract was postponed with the outbreak of war with Serbia, until 1916 also at Danubius shipyard and to replace losses, with Triglav (2), Lika (2), Dukla and Uzsok (building numbers 73 to 76) laid down by August 1916, completed between July 1917 and January 1918 so they were apperently used for a short time before the armistice, but service records are hard to find (see later).

Design of the class

Design Development

The Tátra class destroyers emerged in the context of a rush toward far heavier, faster and more powerful destroyer. Before 1906, most navies saw it simply as an overgrown torpedo boat capable of fleet operations. However under the supervision of Jackie Fisher in Britain, HMS Swift somewhat “cheated” on what a destroyer can be, with a very large vessel, larger than most unprotected cruisers still in service at the time, and much faster. Even if the 1910 completed Swift was a general disappointment, no sooner than 1911, the Russians presented the Novik, ever larger, faster and better armed than anything else at sea classed as such. And she was German-built, so many suspected the Kaiserliches Marine to also start its own “super destroyers” at the time of rising tensions in Europe.

Not to be undone and well served by informers, the Austro-Hungarian naval staff intelligence service watched closely these developments as well as what happened in Italian yards at the time. Soon the admiralty ordered in 1911 the first three destroyer of a new class, almost twice as large as the previous Warasdiner class: The Tátra class. The lead vessel was laid down at Danubius Yard, Porto Ré, on 19 October. Balaton was ordered on 6 November, and Czepel in January 1912 whereas a new plan included three more, to be laid down in the same slip in succession, Lika, Triglav and Orjen, laid down in April to September 1912.

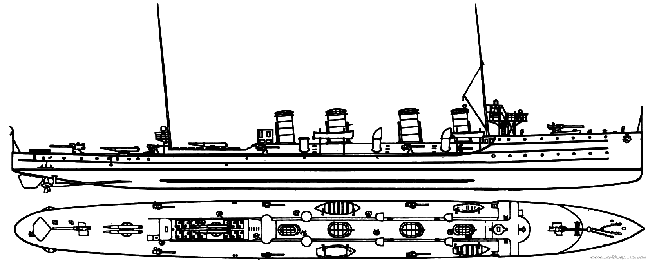

A model of the Tatra as built

These were a pet project of Admiral Graf Rudolf Montecuccoli, head of the Austro-Hungarian Navy which recognized that the Huszár-class destroyers were already obsolete in comparison to foreign destroyers, being still as of the “overgrown torpedo boat” type. His 1910 expansion plan called for six new large destroyers, all powered by steam turbines, to be built in an Hungarian shipyard to secure the Hungarian parliamentary approval, one constant issue in securing budgets for a Navy that mostly benefited the Austrians. The yard contracted was Ganz-Danubius, Porto Ré, in the former Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (now Kraljevica Shipyard in Croatia).

In Italy, the average destroyers displaced 500-600 tonnes at the time, so by 1913, the admiralty was not long to answer in turn, launching a new concept of esploratori, small flotilla leaders class as cruisers, also capable of dealing with these larger destroyers, although that was not their main role. The first were the Poerio class, four vessels launched in 1914 with more classes on order. The Tatra class were only properly answered in turn by the Palestro and Curtatone class launched in 1919-1924, so after the great war.

Hull and general design

The Tátra-class ships were twice as heavy in displacement compared to the previous Huszár class (850 versus 400 tonnes standard) at 850 metric tons (840 long tons) at normal load, 1,050 metric tons (1,030 long tons) fully loaded. And the larger hull (Huszár: 68.4 m or 224 ft 5 in oa) gave them extra deck surface to carry a much stronger armament, while enabling to add extra boilers and larger machinery, so to reach greater speeds. The Tatra class measured in parallel 83.5 meters, and 84 meters (273 ft 11 in) overall, for a beam of 7.8 meters (25 ft 7 in), and maximum draft of 3.2 meters (10 ft 6 in).

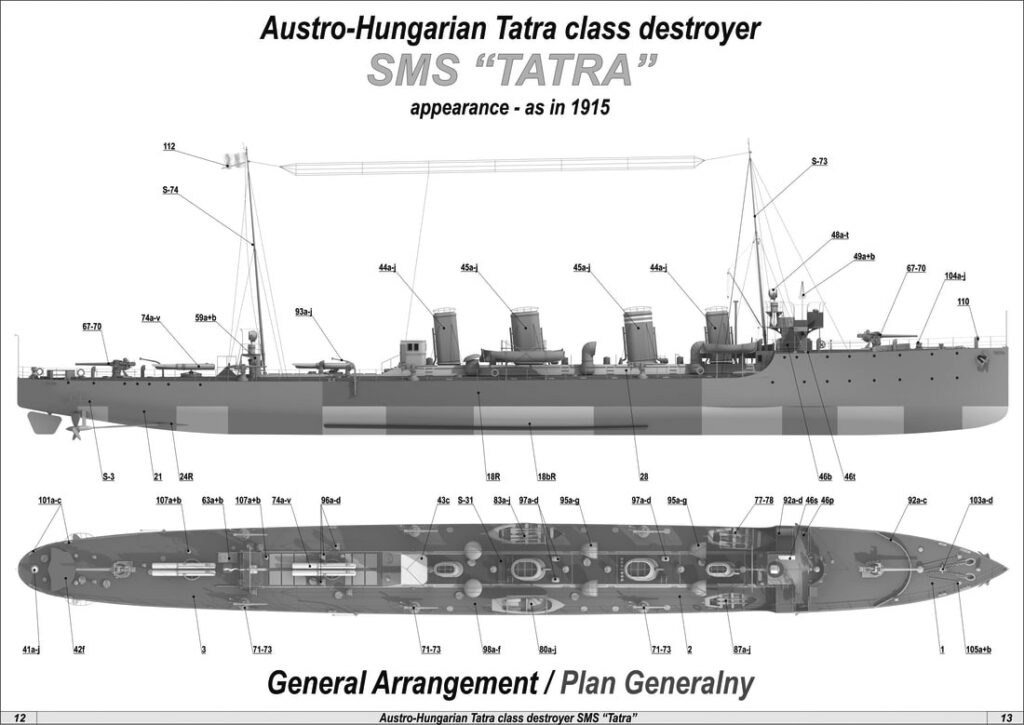

Source: 6th issue of “Card Fleet” magazine and samples of assembly drawings, sheets with part of the Austro-Hungarian Tatra class destroyer SMS “Tatra”.

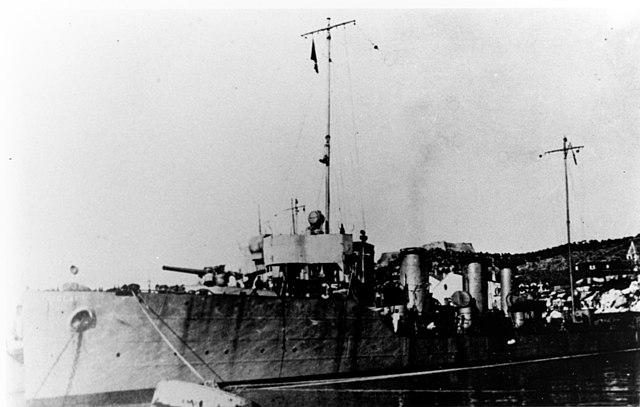

The design was very different of the previous Huszár class ships: They looked more like Admiral Spaun cruisers in reduction, with a long forecastle, and four funnels far apart. Seaworthiness, unlike the Huszár made for the adriatic, enabled Mediterranean operations in all weather (as the range). Their stability as gun platforms and favourable metacentric height also made them better gun platforms. Also thanks to a roommier hull, survival to a torpedo or mine hit was a bit improved. The hull was subdivided into multiple compartmentsthat acted as bulkheads, and side compartments in the bottom where extra coal was stored, but there was no double hull.

The latter had also a straight prow with ‘icebreaking’ chin, counter-keels, and a rounded but vertically straight stern. The shafts were under struts angled downards and there was a single, large rudder at the aft end.

Superstructures were reduced to a minimum: There was an enclosed wooden cabin forward with a metallic winged open bridge above, open to the elements (canvas covered in bad weather), with a chadburn, steering wheel, and acoustic communication to the map table and engine room. There was also a signal and flag bin close to the foremast. Both masts were raked and of similar composite design, and height. The forward one lacked a small spotting top however. There was an upper platform at its base to support a projector. The superstructure went on aft of the forecastle break, with a cabin followed by a half-height buried radiator, ventilation and access structure over the machinery, dotted with the four oval funnels, also raked, and three series of air intake vents. The latter had foldable shutters in case of heavy weather to avoid taking water spray inside.

Aft of the structure was a small cabin for the wireless telegraphy room. Then came the first twin torpedo bank, laid down on a large ventilation platform. Next came a semi open aft quartermaster structure, used as backup bridge with the aft steering wheel, chadburn and communication pipes repeated. Above it was a platform supporting the aft projector.

The ships carried each 105 officers and enlisted men. There were four boats and cutters under davits, the rest were kapock life vests in bins and a few buoys.

Powerplant

The Tátras were powered by two AEG-Curtiss steam turbine sets, a novelty in the Austrian Navy for destroyers, driving each a single three-blade leaf bronze propeller at the end of the shaft. They used steam provided by six Yarrow boilers. Four boilers were oil-fired and the remained burned coal, which was also a novelty. The turbines produced on paper 20,500 shaft horsepower (15,300 kW), for a design speed of 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph). This was moslty achieved on trials, with SMS Lika reaching 32.96 knots (61.04 km/h; 37.93 mph), making her the fastest of the six sisters. They carried 125 metric tons (123 long tons) of oil plus 104 metric tons (102 long tons) of coal for a generous range of 1,600 nautical miles (3,000 km; 1,800 mi), at the economical speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).

The four funnels had unequal size, as the two center ones truncated twice as much exhaust pipes as the outer ones, fore and aft.

To compare, the former had coal-only VTE (Triple expansion engines) rated for 6,000 indicated horsepower (4,500 kW) and 28 knots, and a range or 500 nm, so the new Tatra could go thrice as far.

They were essentially modern long range, fast and well armed fleet destroyers made for Mediterranean operation with the new Tegetthoff class dreadnoughts.

Armament

The main armament of the Tátra-class destroyers consisted of two main guns and six secondaries, mixing 100 and 66 mm. The first ensured a long range but were a bit slower, while the latter were quick firing guns. The torpedo armament was not very large, albeit twin torpedo banks were almost the norm at the time, triple ones being introduced later in the war as a new standard.

Main

Two 50-caliber Škoda Works 10-centimeter (3.9 in) K11 guns, fore and aft of the superstructure in single mounts. They were unshielded. Each weighted 2,020 kilograms (4,450 lb) for a 4.985 meters (16.35 ft) 3.9 in 50 caliber barrel, firing Fixed QF 100 x 892R 13.75 kilograms (30.3 lb) AP shells. The gun used an Horizontal sliding breech block and could elevate up to +18° with a range of 11 km (6.8 mi) at +14°. It had a muzzle velocity of 880 meters per second (2,900 ft/s) and 8-10 rpm rate of fire. This gun became a favourite in the Russian and Italian navy as well as derived into a dual-purpose.

Secondary

Their secondary armament comprised six unshielded 45-caliber 66-millimeter (2.6 in) K09 TAG (Torpedoboot-Abwehr Geschütz) placed on single deck positions along the broadside. Two were placed on anti-aircraft mountings during the war. The first weighted 500 kg (1,100 lb), 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) 18 caliber long, firing a 4 kg (8.8 lb) fixed ammunition of a Caliber 66 mm (2.6 in) – they were called 7cm guns- and using an horizontal sliding-wedge breech for a rate of fire of 20 rpm make them equal to the western Hotchkiss naval guns, and a muzzle velocity of 320 m/s (1,000 ft/s)

Max range was lass than 6 kilometres (3.7 mi).

In 1916-1918, two of their 66/42 SFK L/45 guns were removed and replaced by two single 66mm/42 G. L/45 BAG (dual purpose guns).

Torpedo Tubes

They were also equipped with four 450-millimeter (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, placed in two twin rotating mountings, aft of the funnels. Whitehead-Luppis model, no more data on these; Check the destroyer page for more. These destroyers were not equipped to lay mines. But they could received paravanes, although no photos shows any.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 850 t (840 long tons) standard; 1,050 t (1,030 long tons) FL |

| Dimensions | 83.5 x 7.8 x 3.2m (273 ft 11 in x 25 ft 7 in x 10 ft 6 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts steam turbines; 6 × Yarrow boilers, 20,500 shp (15,300 kW) |

| Speed | 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Range | 1,600 nmi (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Armament | 2× 10 cm (3.9 in), 6× 66 mm (2.6 in), 2×2 45 cm (17.7 in) TTs |

| Crew | 105 |

Ersatz Triglav class (1915)

No plan survived (to my knowledge) of the Ersatz Tatra. But they were “near-repeats” with very similar design caracteristics.

Six additional destroyers were authorised on 28 May 1914 for replacement and increase the number of destroyers flotillas in service, but construction was cancelled before they were laid down in August. The Austro-Hungarian staff awanted more modern destroyers as quickly as possible. They believed that, if the large esploratori were left aside (they would be dealt by the Admiral Spaun and Ersatz Zenta), these new generation of large destroyers would certainly gave them an edge over the Italian average destroyers of the time.

In 1914, the latest Italian models just entering service were of the Audace class, displacing 750 tonnes standard, 36 knots. The next Pilo class in construction displaced 750t standard for 30-33 knots and were less costly. They shared a main armament of 3-in/40 (76 mm) guns, so the Austrian vessels with their 10 cm guns (4-inches) had an advantage.

In addition to these four vessels, four more were approved in 1916 as replacements. The first were completed late in the war, and apparently saw little service. They were laid down by August 1916, and completed between July 1917 and January 1918. They were attributed later as war reparations to Italy (the first three, Triglav, Lika and Uszok, and Dukla to France. Triglav was renamed Grado, stricken 1937; the two others Cortelazzo and Montfalcone, discarded in 1939, and the French Dukla became Matelot Leblanc, discarded in 1936. See the list below for more

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 880 t standard; 1,045 t FL |

| Dimensions | 85.4 x 7.8 x 2.8m |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts AEG steam turbines; 6× Yarrow boilers, 22,360 shp |

| Speed | 32.6 knots (60.7 km/h; 37.5 mph) |

| Range | presumed the same |

| Armament | same but 2× 66 mm on AA mountings |

| Crew | 114 |

Improved Tatra class (1915)

Four up-gunned variants of the the Ersatz (“replacement”) triglav, ordered on 22 December 1917, with 120 mm (5-in) instead of 100 mm guns and reinforced decks. Dimensions and displacement similar if not specified otherwise. The other great change was the adoption of just two 90 mm dual purpose guns, likely placed amidships on a cross platform between funnels. This could have been freed the deck to install mine rails as well. Unfortunately we have no plans for these. Shortages of all sorts prevented them to be laid down. Names not known, probably same as those lost.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Armament | 2× 12 cm (4.7 in), 2× 90 mm/45 AA (4 in), 2×2 45 cm (17.7 in) TTs |

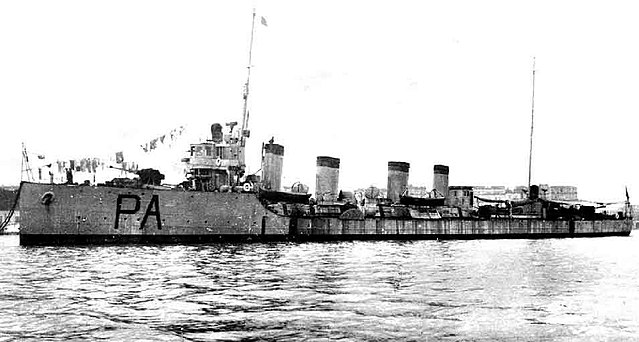

In Italian service: The Pola class

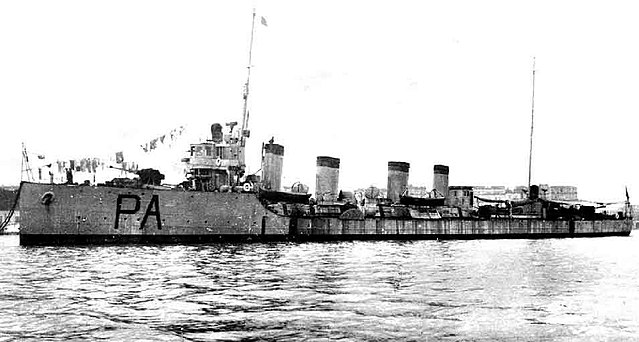

Pola, ex Orjen in the 1920s

At the end of the war, the Austro-Hungarian Navy was dissolved and surviving boats delivered to victorious powers. In 1919 most were transferred to Italy which received seven destroyers, and France just one (The Matelot Leblanc, ex Dukla). She latter was assigned to the torpedo school. From 1931 onwards she became a depot ship until decommissioned in 1936, scrapped in 1941.

Fasana ex-Tátra and Zenson ex-Balaton were only used for spare parts and scrapped in 1923. They were known as the Fasana/Grado class.

Muggia ex-Czepel was overhauled and back into service in 1923 with Italian weaponry and systems. She served in the Aegean, Constantinople, Black Sea and Dodecanese. In 1926 She was sent to join the Far East fleet, operating from Shanghai by March 1927, as the civil war was raging. She stayed to protect Italian citizens and monitor the situation and cruised between Hong Kong and Dairen or up the Yang Tse. On the night of March 26, 1929, underway from Amoy to Shanghai she ran aground in the fog, in the archipelago off Taichow, capsized. The crew escaped to the island of Hea Chu and were later picked up by the Japanese steamer Matsumoto Maru, landed to Wusung and repatriated on the cruiser Libia.

SMS Triglav (2) became Grado in service of the Italian Navy, as Lika (2) now Cortellazzo, and Uszok Monfalcone while Orjen, briefly sereved in the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1918 ebfore being asked by the Italian Navy, named “Pola” on September 26, 1920. They became training destroyer at Taranto and Venice, cruising the Adriatic and central Mediterranean, even Italian North Africa in the interwar. In October 1929, they were reclassified as torpedo boats. April 9, 1931 saw Pola renamed Zenson (2) to free the name for the new heavy cruiser of the Zara class ans on July 1, 1932, Zenson made a long cruise with the ex-German cruiser Taranto between the Adriatic ports, Albania and Greece as well as Italian North Africa, training machinists. Cortellazzo accompanied Taranto on a similar training trip to Libya, Greece and the Dodecanese.

On May 1, 1937, Zenson was decommissioned and scrapped; Grado followed on September 1937. By January 1939 this was the turn of Cortellazzo and Monfalcone.

Note, the dates given as of launch.

Read More/Src

Books

Bilzer, Franz F. (1990). Die Torpedoschiffe und Zerstörer der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1867–1918. Graz: H. Weishaupt.

Cernuschi, Enrico & O’Hara, Vincent (2016). “The Naval War in the Adriatic, Part 2: 1917–1918”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2016.

Dodson, Aidan & Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after Two World Wars. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Freivogel, Zvonimir (2021). Austro-Hungarian Destroyers in World War One. Zagreb: Despot Infinitus.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Greger, René (1976). Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan.

Halpern, Paul G. (2004). The Battle of the Otranto Straits: Controlling the Gateway to the Adriatic in World War I. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Halpern, Paul G. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Noppen, Ryan K. (2016). Austro-Hungarian Cruisers and Destroyers 1914-18. New Vanguard. Vol. 241. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing.

O’Hara, Vincent P. & Heinz, Leonard R. (2017). Clash of Fleets: Naval Battles of the Great War, 1914-18. Annapolis

Roberts, John (1980). “Italy”. In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 280–317.

Sieche, Erwin (1985a). “Austria-Hungary”. In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Sieche, Erwin (1996). Torpedoschiffe und Zerstörer der K. u. K. Marine. Marine-Arsenal Vol. 34. Pozdun-Pallas-Verlag.

Sieche, Erwin F. (1985b). “Zeittafel der Vorgange rund um die Auflosung und Ubergabe der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1918–1923”. Marine—Gestern

Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press.

Vego, Milan (1982). “The Yugoslav Navy 1918–1941”. Warship International. XIX (4)

Links

en.wikipedia.org/wiki

navypedia.org/

Ersatz_Triglav-class_destroyer

de.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1tra-Klasse

Videos

Model Kits

3D

Career of the Tatra class

Tátra (1912)

Tátra (1912)

By April 1915 Itay was secretely asked to break its alliance with the German Empire and Austro-Hungary and Austro-Hungarian intelligence passed the information to Admiral Anton Haus, commander of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, to carry out a massive surprise attack on Italian ports, Northern Adriatic coast, out of reach of the fleet at Taranto. Haus pre-positioned three groups of destroyers led each by a scout cruiser acting as flotilla leader. They formed a defensive screen against any move north, being srpayed along the Central Adriatic, between the island of Pelagosa and Italian coast. This was done four days before the official declaration of war on 23 May. Among these were the four Tátra-class destroyers, in a single division led by SMS Helgoland. At midnight, 23/24 May, Haus ordered these reconnaissance groups to move west, attacking Italian coastal targets at will. Just one hour later the four Tátras met two patrolling Italian Nembo-class destroyers, Turbine and Aquilone but the later assumed they were friendly ships.

Aquilone departed to close on a sighting while SMS Helgoland started shelling Barletta at 04:00, spotted at 04:38. She turned away southeast, disengaging, but Turbine, later also spotted Helgoland minutes later also believing she was an Italian ship until greeted by a salvo, turning north towards Vieste and escaping, with Helgoland and SMS Orjen in hot pursuit. Captain Heinrich Seitz aboard SMS Csepel and Tátra, shelling until then Manfredonia, were detached to find Turbine at 05:10, and at 05:45 spotted her and fired. SMS Lika, bombarding Vieste, was ordered to block her escape to the north while Helgoland trie to cut off her way back to the Adriatic. Lika in pursuit landed a 66-mm shell which broke Turbine’s steam pipe. She lost speed, was caught up by Tátra and Helgoland which fired until she was dead in the water, listing, abandoned at 06:51. 35 survivors were rescued and she was torpedoed. Meanwhile while retiring, the cruiser Libia arrived on the scene with the armed merchant cruiser SS Cittá di Siracusa and started firing at 07:10 and 07:19. Helgoland too a hit but disengaged with the destroyers.

Two days later, Tátra returned and bombarded, occupied by the Italians on 11 July. Next, 12 days after Helgoland, Saida, escorted by Tátra, Csepel, Balaton and three others made a bombardement sortie on Termoli, Ortona and San Benedetto del Tronto, having a landing party on Tremiti to destroy the telegraphic station. On 28 July, all six Tátra-class destroyers and same cruisers sortied with UB-14 to recapture Pelagosa. But the 108-man landing party was rebuffed by the 90-man Italian garrison.

After the Bulgarian declaration of war on Serbia (14 October) the Allies had to supply Serbia via Albania and the Austro-Hungarian staff knew it and prepared an attack. Helgoland, Saida and the six Tátra-class went on reconnaissance off the Albanian coast (night 22/23 November) and found, sank a small cargo ship and motor schooner. The four Italian destroyers which sortied arrived too late. The the Armeeoberkommando (general staff) ordered Haus to sally forth again on 29 November for the Albanian coast. The Tátra-class were moved to to Cattaro. On 6 December, Helgoland with the destroyers sailed off Durazzo, spotting and sinking five motor schooners, even in port.

1st Battle of Durazzo (1915)

An aircraft spotted Italian destroyers in Durazzo on 28 December, Haus sent Seitz aboard Helgoland, with Tátra, Csepel, Lika, Balaton, Triglav for patrolling between Durazzo and Brindisi. They arrived at Durazzo at dawn and rampaged the port, sinking all ships present. Seitz later also spotted and sank the French submarine Monge at 02:35. At 07:30 four destroyers were detached into the harbor, sinking cargo ship and two schooners, Helgoland dealing with coastal batteries. She was surprised by a concealed 75-mm (3 in) battery at 08:00, point-blank and when maneuveringLika and Triglav entered a minefield. Lika sank at 08:03, Triglav was crippled (boiler rooms flooded) after a hit, but maneuvered out but when Czepel sent a towline, it got tangled in one of her own propellers. Tátra managed to tow Triglav at 09:30, rescuing 33 seamen but could only leave at six knots when ordered northwards. Seitz radioed for assistance and was informed that SMS Kaiser Karl VI and four torpedo boats were about to arrive in support.

At 07:00 meanwhile, an Allied quick-reaction force was scrambled: Light cruiser HMS Dartmouth, scout cruiser Quarto, five French destroyers, which were order to cut off their retreat to Cattaro. Later they were reinforced by Nino Bixio, HMS Weymouth, four Italian destroyers. Seitz ordered to transfer Triglav’s crew when columns of smoke were spotted. Tátra dropped her tow at 13:15. Soon the French destroyers in vanguard arrived and finished off Triglav at 13:38. The two cruisers chased Helgoland and Tatra.

Seitz made a turn southwest at 29 knots but Dartmouth opened fire from 13,000 meters at 13:43, scoring a hit at 14:00 but destroyers were left alone, Csepel hit once. Still the Austro-Hungarian managed to reach the Italian coast as darkness fell. Tátra experienced a breakdown at 18:45 and fell to 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), later reaching Šibenik and the rest of the ships.

Raids on Otranto 1916-1917

On 4 July 1916 Helgoland, Tátra, Orjen, Balaton raided the Otranto barrage in poor visibility, failing to find targets. Tátra had a short refit on 1–31 December in Pola with two boilers replaced. On 11/12 March 1917, Tátra, Orjen, Csepel and Balaton made another sortie in the Strait of Otranto, spotted and attacked the French cargo ship SS Gorgone, which escaped. Tátra missed the Battle of the Strait of Otranto on 14–15 May, arrived with reinforcing ships. In Pola she was refitted from 26 May to 13 August, boiler again. They sortied again with Helgoland but were spotted by Italian aircraft and cancelled the operation. On 12-13 December, Tátra, Balaton and Csepel raided the Otranto Barrage, believed they spotted four Allied destroyers and dropped torpedoes but made not hits.

Mutiny and end of war

On 1 February 1918, a mutiny broke ou at Cattaro on SMS Sankt Georg, spreading to Kaiser Karl VI and other major warships, also threateing to fire on smaller ships (like destroyers) and TBs that had much better morale and loyalty, ordered to raise in turn the red flag. Tátra’s crew hoisted a flag only under permission of her captain to avoid trouble and many did so. After Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf was fired upon the mutiny ceased, and the scout cruisers as well as Tátra joined loyalist forces in the inner harbor, protected there by coastal artillery. The uprising was over the next day.

She left Pola on 7 June for Cattaro and a last attack on the Otranto Barrage scheduled for 10 June, canceled after SMS Szent István was sunk by MAS underway. Tátra and Orjen rescued SS Oceania, running aground on 13 October. Tátra als carried Seitz to Pola on 30 October.

By October, Emperor Karl I started negociations with the entente and broke its alliance with Germany, acted on 26 October, while Vice Admiral Miklós Horthy on 28 October tried to maintain order and prevent a new mutiny.

The National Council in Zagreb announced its separation, created a goverment and started to expel Hungarian officials, and Vienna asked the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs for help to prevent the fleet stationed at Pola to rebel or be seized. The National Council refused unless the Navy came under its own command. The Emperor agreed to the transfer (provoking the Italians). Soon, All sailors not of Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, or Serbian background were asked to leave, officers were given a choice to serve the Yugoslav or come back home.

On 3 November Armistice was asigned at Villa Giusti and Italy still refused to recognize the transfer to Yugoslavia. On 4 November the Regia Marina sent all its assets to forcibly seize Trieste, Pola, and Fiume with Italian troops landed at Pola. The National Council did nit resisted but condemned the actions and by 9 November, all ships in Pola harbour now flew the Italian flag. The Corfu conference had the entente powered refusing the transfer but eventually the National Council agreed on 10 November. Seizure was realized only by 23 March 1919, all ships interned to Venice, shown in a victory naval review. By January 1920, Tátra was awarded to Italy, renamed Fasana.

Balaton (1913)

Balaton (1913)

Note: Since their common career has been seen above, this will be short and really centered on her. On 13 August 1914, Balaton rescued survivors from the passenger ship SS Baron Gautsch which ventured into a minefield. On 23 July, she sortied with SMS Saida and SMS Helgoland, Csepel and Tátra, three more to bombard Termoli, Ortona and San Benedetto del Tronto. Later she was part of the attempt to recapture Pelagosa. Later under Linienschiffskapitän Heinrich Seitz aboard Helgoland she ventured on the Albanian coast on 22/23 November. Same on 29 November, and she took part in the raid in Durazzo harbor but also the 1st Battle of Durazzo.

When four destroyers entered the harbor, Balaton patrolled the seaward flank. Her sisters blundered int aminefield to avoid battery fire while she was off the coast. When retiring to avoid the entente fleet in hort pursruit, Csepel was followed by Balaton and Tátra on 30 December 1915. She reached Šibenik safely.

Balaton had her Pola refit on 1 January-11 February 1916. She sortied on 31 May/1 June with SMS Orjen and three TBs to attack the Otranto Barrage, she sank one drifter with a torpedo. On 4 July with Helgoland, Orjen and Tátra she made another raid, which failed due to poor visibility. Next with Helgoland, Novara, and Orjen, she planned a bombardment, foiled on 29 August as it was too foggy to see the coast. She made another raid on 11/12 March 1917 with Orjen, Csepel and Tátra to Otranto, but failed to sink SS Gorgone.

She also took part in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto on 14/15 May with Csepel from Cattaro, patrolling the Albanian coast and Strait of Otranto, as a diversion while the three Novara-class scout cruisers raided the barrage. Both destroyers spotted a convoy of three merchant ships escorted by the Italian destroyer Borea at 03:10. Borea wa slit up by searchlight at 03:24 and took 4 hits, one breaking her main steam pipe. Soon she was dead in the water and on fire, sinking before dawn. Balaton also destroyed the 1,657 gross register tons (GRT) SS Carroccio (ammunition cargo exploded) and they burned the other two but failed to sink them. They disengaged but were soon to be intercepted by Carlo Mirabello and three French destroyers on alert at 04:35. They failed to reach them, but other did at 07:45: Two British light cruisers, Aquila and four Italian destroyers under Rear Admiral Alfredo Acton. The scout aquila, being the fastest, reached them first and opened fire at 08:15 from 11,400 meters (12,500 yd), then closed to 9,600 meters (10,500 yd) but Csepel hit her at 08:32 in her main steam line, she lost powered and speed, and the other Italians destroyers resumed the pursuit until broke off as Durazzo’s coastal artillery took them in their scope by 09:05. Balaton and Csepel went for Cattaro, being ambushed underway, but missed, by the French submarine Bernoulli. In all Balaton fired 85 main rounds, 60 secondaries and two torpedoes. This was to be her most significant action of the war.

On 13 December, Balaton, Tátra and Csepel raided the Otranto Barrage and soon disengaged. Later during the 1918 mutiny, Balaton’s crew hoisted a flag under permission and later moved to the inner harbor. On 1/2 July, she sortied with SMS Csikós and two torpedo boats to support the Austrian air raid on Venice. Spotted by seven Italian destroyers south of Caorle they esxchanged fire before disengaging. Both Balaton and Csikós took a hit. Later the former had refit at Pola on 12 September. During the complicated standoff following the creation of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in Pola she was transferred on 4 November, to Italian control. This was acted on January 1920, and she became Zenson on 27 Septembe, discarded on 5 July 1923, cannibalized.

Csepel (1913)

Csepel (1913)

On 13 August 1914, Csepel rescued 76 survivors from the mine-sunk Austro-Hungarian passenger ship SS Baron Gautsch. Later as vibrations were noted, she had her propeller shaft bearings replaced on 9-12 May 1915. She will share the fater of the other class’s ship. First with the Action off Vieste. Led by SMS Helgoland she was sailing in the night of 23/24 May, to bombard Italian coastal targets. Csepel and Tátra bombarded Manfredonia, and were asked to intercept the Italian destroyer Turbine but Csepel was hit once during the engagement.

On 23 July she made aother sortie with Helgoland and SMS Saida on Termoli, Ortona and San Benedetto del Tronto while and another to recapture Pelagosa. She sortied on the Albanian coast on 22/23 November, taking part in the sinking of a small cargo ship and motor schooner. She was on the 29 November and 6 December raids as well as in the first Battle of Durazzo on 28 December. After was sank the French submarine Monge; Csepel rescued seven survivors. Unable to find her sisters, she arrived off Durazzo at dawn. After Triglav hit a mine in the port, crippled, Csepel attempted to pass a towline the latter was tangled into her own propellers, so she was only able to sail to 20 knots when ordered northwards. During the later pursuit, The French destroyers attacked from 13:38 Czepel, while Quarto moved to to cut-off her retreat, until ordered otherwise. The pursuit laster for fifteen minutes but in between Czepel managed to reach 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) and despite shelling by Quarto from 8,000 meters (8,750 yd) while zigzagging, she taked a single hit with little damage.

On 27 January 1916, Novara, Csepel and Orjen departed Cattaro to attack Durazzo harbor but the first two accidentally collided and retired. Csepel was under repair until 21 April. On 4 May she was ambushed by the French submarine Bernoulli off Cattaro. The torpedo blew off her stern and she was towed to port, then Fiume for permanent repairs 13–16 May, then on 3 June, moved to Porto Ré to receive a replacement stern from an Ersatz Triglav-class under construction. He first sortie was in the night of 11/12 March 1917 with Balaton, Orjen, and Tátra in the Strait of Otranto. She fired on the SS Gorgone as well. Next she took part in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto on 14/15 May, with Balaton, rampaging through a convoy of three merchant ships, sinking the escort Borea. It was Csepel that lit her up at 03:24.

Meanwhile the entente scrambled the Carlo Mirabello leading three French destroyers at 04:35 in interception, failed to reach them but two British light cruisers, Aquila and four Italian destroyers did. Aquila was the first on their heels. They were fired upon at 08:15 from 11,400 meters (12,500 yd) and 9,600 meters (10,500 yd), Csepel was only hit once at 08:32. She had her main steam line severed, 7 killed, and she lost power but turned towards Cattaro, and evaded an attack by the sub Bernoulli. In total she fired 127 main rounds 78 secondaries, two torpedoes.

On 13 December, she took part in another raid on the Otranto Barrage. During the 1918 mutiny she was allowed to hoist a red flag to avoid larger vessel’s reprisals and later retired with her sisters in the inner harbour until the mutiny was quelled. She was refitted in Pola from 7 to 20 April and took part in her last action on 22 April 1918:

She took part in the night 22–23 April 1918 Allied shipping interception in the Strait of Otranto. Spotted by Jackal and Hornet patrolling the western they started a duel from 2,700 meters (3,000 yd) and the british DDs retreated under a smoke screen to lure the Tatra class further south. Jackal took three hits, Hornet was badly damaged and sunk after the explosion of her forward magazine, after taking more hits due to her jammed steering, and turning circles. The Austrians disengaged after about 15 minutes with Jackal in pursuit, still. They sailed for Cattaro and Csepel received an extensive refit (13 June – 7 October) in Pola.

After the war, the vissicitudes of the National Council in Zagreb had her crew disbanded after briefly being controlled by the Yugoslavs, and after the Armistice of Villa Giusti she was seized on 4 November, officially Italian on 9 November, commissioned as Muggia on 26 September but transferred to Shanghai in March 1927, ran aground was wrecked near Hea Chu Island near Amoy on 25 March 1929. 77 survivors. The wreck was latter scrapped.

Lika (1914)

Lika (1914)

SMS Lika was completed on 8 August 1914 and pre-positioned before the war in the Central Adriatic between the island of Pelagosa and the Italian coast, led by SMS Helgoland with her sisters. Around midnight, 23/24 May, she was directed to attack coastal targets. They spotted Turbine and Aquilone, but nothing came of it as the latter let them pass, believing them friendly.

Turbine later stumbled on Helgoland and escaped after being straddle, chased by Helgoland and SMS Orjen. After Csepel and SMS Tátra, were sent in turn to interception, Lika, bombarding Vieste, was asked to cut off her retreat and indeed caught Turbine, hit her and broke her steam pipe she was finished off soon by her pursuers. She was part of another raid on 28 July with Saida and Helgoland on Pelagosa annd again on 18 August. Next was the raid on 22/23 November off Albania, same on 6 December, and the 1st Battle of Durazzo, on 28 December on Durazzo. Ordered to enter the port and rampage shipping, they were surprised by well-camouflaged 75-mm (3 in) artillery battery at point-blank range, and when escaping through a minefield with Triglav she hit two mines in quick succession, and sank at 08:03. Triglav barely escaped, but survivors of Lika were few of any, made prisoners.

Triglav (1914)

Triglav (1914)

Triglav was completed on 8 August 1914 and for first refit, from 9 November to 12 December she had her propeller shaft bearings replaced.

Her first major mission was the Bombardment of Ancona as Triglav screened the ships involved in the operation. Later she made another raid led by SMS Saida and Helgoland, reinforced by UB-14 on Pelagosa which could not be overcome.

She was part of the raid on 22/23 November, 6 December, in Durazzo harbor and took part in the 1st Battle of Durazzo on 28 December, arriving at dawn, destroying any ships found in port. Creeping into the harbor Triglav and Lika sank a cargo ship and two schooners but as said above for Lika, she was taken aback for a well conealed 75 mm (3 in) artillery battery which started to open fire and make hits from 08:00 at point-blank range. The two destroyers started to maneuvering to avoid fire, but only to enter a minefield. Like hit two mines and sank quickly without apparent survivors, but Triglav hit only one, which flooeded her boiler rooms. Still, she maneuvered out of the minefield. SMS Csepel came to the rescue, tried to pass a towline, only to get tangled in one propeller and retire at slow speed. Tátra succeeded where Csepel missed, sent a tow at 09:30, but crawled at six knots to the exit and northwards. Meanwhile the entente sent HMS Dartmouth and Quarto plus five French destroyers, then Nino Bixio, HMS Weymouth, four Italian destroyers.

As the trap was closing on them, there was no chance but to raise steam and try to get through as fast as possible. Meanwhile Triglav was a hinderance. Unde orders she was evacuated, abandoned, whe the columns of smoke were spotted at a distance. When done, Tátra drop her tow at 13:15, abandoned Triglav to her fate. The French destroyers promptly sanl the empty ship at 13:38 when the French commander was deceived by smoke still coming from Triglav’s funnels. He opened fire at 5,000 meters (5,500 yd) but was taken aback by the absence of return fire, closed in but kept his torpedoes, instead finished Triglav by gunfire in 30 min. This ruse prevented the French to join back the pursuit.

Orjen (1914)

Orjen (1914)

SMS Orjen was completed on 11 August 1914 and on 9-24 December, like most her sisters, she had her propeller shaft bearings replaced in Pola.

First, she took part in the action off Vieste on the night on 23-24 May, sent to attack Italian coastal targets. Later they were in hot pursuit of Turbine, with Helgoland and Orjen in pursuit. It was Lika that caught her eventually, scored the critical hit which doomed her as she was caught in turn by Tátra and Helgoland, Csepel and Orjen. The vivtorious fleet retreated as Libia and SS Cittá di Siracusa arrived.

On 28 July, she was involved on the failed recapture of Pelagosa and the Albanian coast raid in the night of 22/23 November and on 29 November. By 27 January 1916, she departed Cattaro with Novara and Csepel for Durazzo harbor. But she collided with Csepel, and was forced to return home. She had her bow bent and stayed under repair until 16 February. She later made sorties on 23 and 26 February, then 31 May/1 June 1916 with SMS Balaton and torpedo boats on the the Otranto Barrage. She sortied again on 4 July with Helgoland, and sisters Balaton and Tátra, then in the night of 23/24 July with Helgoland and Novara, her and Balaton. Orjen was refitted in Pola on 1–22 October and escorted convoys until the night raid of 11/12 March 1917 with sisters Balaton, Csepel and Tátra again on the Strait of Otranto. She had boilers replaced between 30 March and 14 May, and was based in Cattaro, looking for the missing flying boat K222 on 11 August.

In 1918 she did not joined the mutiny, raised a bodus red flag, then entered the inner port for protection. No more missions for her until October, and she fell under indiorect supervision of the National Council in Zagreb transferred by Emperor Karl I’s government as the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was created. The her crew was mostly disbanded. By January 1920, Orjen was awarded to Italy, recommissioned as Pola on 26 September, refitted, standardized, assigned to the Venetian squadron, then reserve in Taranto 1924 to 1928, sent in Libya in March, Venetian squadron in 1929, Libya again, renamed Zenson in 1931, discarded on 1 May 1937, scrapped.

Career of the Ersatz Tatra class

Triglav(ii) (1917)

Triglav(ii) (1917)

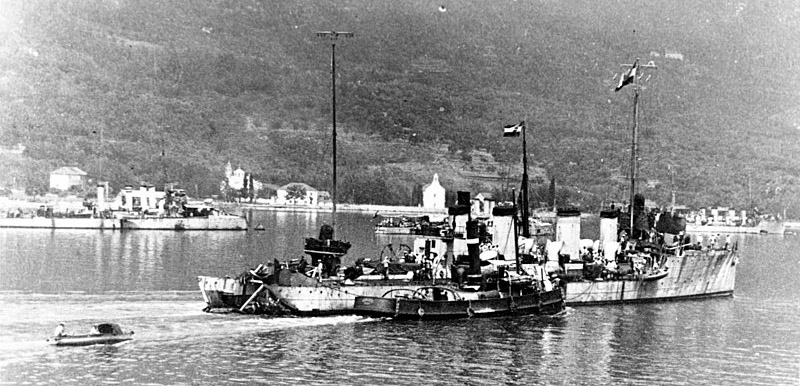

Triglav II in 1918, Photographed in the Gulf of Cattaro. She replaced her namesake sister sunk in 1915.

On 19 November 1917, Triglav, with Reka and eight torpedo-boats laid mines between Ancona and Venice and on the night of 28/29 November she accompanied seven destroyers, eight torpedo-boats to shell the coast between Porto Corsini and Rimini. Triglav, Dinara and four TBs bombarded Metauro. On their way back, intercepted by 10 Italian destroyers, but escaped. 19 December, escorted the battleships Budapest and Árpád, Admiral Spaun shelling batteries of Cortellazzo.

Night of 22/23 April 1918, with Csepel, Dukla, Lika, Uzsok, under Karl Herkner (aboard Triglav ii), raided the Strait of Otranto, met HMS Hornet and Jackal. Engaged them and later HMS Alarm, HMAS Torrens and French Cimeterre, but escaped unharmed. June 1918, under RADM Miklós Horthy, sailed with Novara and Helgoland to attack between Fano and Santa Maria di Leuca, but operation cancelled, however (Szent István sinking). Under National Council, crew disbanded. January 1920, Triglav awarded to Italy, commissioned as Grado, discarded 30 September 1937.

Lika(ii) (1917)

Lika(ii) (1917)

She was completed on 6 September 1917 ad saw no notable service until October 1918. Owned by the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, crews disbanded, ships later reclaimed by Italy in 1919, handed over on 10 November, formally attributed to Italy on January 1920, recomm. as Cortellazzo, discarded, scrapped the last, on 5 January 1939.

Dukla (1917)

Dukla (1917)

Dukla was completed on 7 November 1917 but saw little to no service until the end of the war. Under supervision by the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs in Pola crews disbanded, reclaimed 1919 by Italy, then handed over on 10 November, attributed to France formally by January 1920, recommissioned as Matelot Leblanc by September 1920, in service until stricken on 30 May 1936, BU in Bizerte, French Tunisia.

Uszok (1917)

Uszok (1917)

Launched on 16 September 1917, completed on 25 January 1918. Saw little service, did not took part in the mutiny like her sisters. Surrendered to the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, later attributed to Italy 1920.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign