The proverbial British torpedo bomber

The “string bag”, Swordfish, made by the British Fairey company, is fondly remembered now, cementing its place in the hall of fame of aviation due to its actions during WW2 and showing fighting qualities that outshined many other biplanes of the era. The formula was so great that its designated successor, Albacore, was not only also a biplane, but never really shadowed it. Neither this one of the ungainly Barracuda that followed, a monoplane, never reached the same fame and adoration. Now, beyond the myth, let’s see the plane itself technically, and if these were its qualities, the pilots, the tactic/training or the events that made its so special.

Fairey’s saga with the Royal Navy

Fairey Aviation started like many others in WWI: In 1915, it was funded by Charles Richard Fairey (more on WWI planes), and started as the main supplier of the Royal Naval Air Service right away, providing the Royal Navy models such as the Hamble Baby, F.2, Campania, Fairey III and N.9 in 1917-18. The Campania, operated from its namesake converted liner as a seaplane carrier, was the world’s first tailored aircraft for such use. The interwar saw the company dividing its assets, the Propeller Division (Fairey-Reed Airscrews) in the Hayes factory, using Sylvanus Albert Reed patents, and main manufacturing plant at North Hyde Road, Hayes (Middlesex), flights tests being made at Northolt Aerodrome, Great West Aerodrome and Heston Airport and White Waltham in WW2 and afterwards. The company diversified but got bankrupt in 1960. In between it gave aviation history many great models (and others less so), always close to the Royal Navy. It had also ties with Belgium, through the engineer Ernest Oscar Tips joining the company early on, and later Marcel Lobelle. In 1935, the main production took place in the Heaton Chapel Stockport factory, from which emerged the monoplane Bomber Hendon, the Battle, Albacore, Fulmar, Firefly and Barracuda. But it’s for a biplane, the Swordsfish, that the company is best remembered for. The last model developed for the Navy was the Gannet, an ASW turboprop model deployed on all British aircraft carriers in the 1950s-70s. This was Fairey’s last great “navy bird”.

Gloster Gauntlet and Fairey Swordfish, 1936

Development of the Swordfish

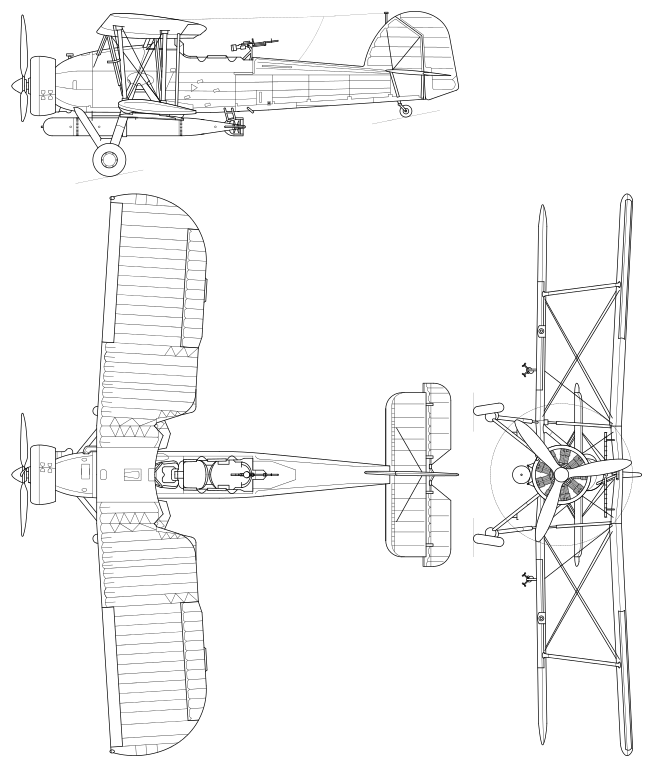

The Swordsfish is in part the result of a competition between Blackburn and Fairey over these multirole torpedo/bomber/recce biplanes the RN wanted. At the base of this industrial rivalry was the WWI fairey III, a dependable torpedo-Bomber answered by the Blackburn Blackburn. The model III was so sturdy and dependable it’s career went on until …1941. Naturally, it was chosen as a base to develop in 1928 the next model, the Fairey Seal (first flight 1930), developed from the prototype Fairey IIIF Mk VI. It saw limited production and Blackburn sold more of its Blackburn Shark, which first flew in 1933 and replaced it. By the way, the Shark was produced until 1939 (although already obsolete by 1937) and soldiered for the duration of WW2, but it was largely ecplised by the next model from Fairey. At this juncture, Fairey indeed wanted to improve the Seal.

In 1933 Fairey indeed started development of an entirely new three-seat reconnaissance/torpedo bomber, soon receiving the internal designation T.S.R. I (“Torpedo-Spotter-Reconnaissance I”). The reason a single plane was tasked for so many roles was a reflection od British Aircraft carriers of the time, which had a limited capacity, contracry to USN later CVs, which emphasized the largest air group possible. Instead of starting with an improvement of the Seal, the company however stuck to a biplane configuration, propelled by a single 645 hp Bristol Pegasus IIM radial engine. In 1933, this choice was already a controversial one, as all companies now were turning their efforts to develop monoplanes. This would come to an age in 1935 only however, after first attempt, mostly fixed-undercarriage models of 1933-35.

Fairey reasons for maintening it’s biplane configuration however at the time sounded reasonable and well-thought. The biplane configuration was already well-known and ensured a quicker development than a brand new venture (a leap the company made alreeady years ago with the Hendon, not a sucess). The biplane configuration advantages largely matched its role: Priority was range, not speed. It was believed at the time that reconnaissance aircraft needed to be either biplanes or parasol monoplanes to ensure the best visibility. Cantilever monoplanes were notorious for their poor all-round visibility, akin the extreme competition planes that were developed. A biplane brould more sustentation, so more range and also more stability, which was ideal, both for reconnaissance and dropping a torpedo perfectly in line. It was also a configuration ideal for the well-winded decks of aircraft carriers and landed more smoothly, and on shorter distances.

TSR-I

Fairey also choose to quickstatrt this development outside any official specifications, a self-financed private venture. Future navy specifications were an educated guess, which proved correct. Development of the T.S.R. I however at least followed another Air Ministry Specification, S.9/30, for which Fairey developed a broadly similar aircraft with a Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine and new fin and rudder configuration. The T.S.R.I’s development also came from a proposal to the Greek Naval Air Service, requested replacement for their Fairey IIIF Mk.IIIB. The TSR-I also shadowed the air ministry specifications M.1/30 and S.9/30. When its prototype was sufficiently advanced, Fairey informed the Air Ministry of their latest project, since the Greeks renounced the order. They proposed it to match the requirements for a spotter-reconnaissance plane in 1933, but the next year the Air Ministry issued S.15/33, adding the torpedo bomber role to it. This all checked Fairey’s boxes for its TSR-I, hich first flew on 21 March 1933. Immatriculated F1875, it took off at West Aerodrome, Heathrow, piloted by Chris Staniland. After various flights it was re-engined with an Armstrong Siddeley Tiger radial, flew again, then adopted the Pegasus engine now retuned. These flights were done to test the flight envelope and determine its flight characteristics. On 11 September 1933, the prototype was lost however during spinning tests, but fortunately the pilot parachuted and survived the incident.

TSR-II

Despite its accident, the TSR-I however displayed very favourable performance, so fairey decided to go on with the next iteration, the T.S.R II prototype, now perfectly matching the Specification S.15/33. On 17 April 1934, T.S.R II (K4190) was flown by Staniland, propelled by the latest, more powerful Pegasus engine. It also shown an additional bay within the rear fuselage to combat the plane’s spin habits. The upper wing was also slightly swept back to keep balance due to the longer fuselage, plus a few more aerodynamic fixes at the rear. The flight test programme was concluded well, and the prototype was moved to Fairey’s factory in Hamble-le-Rice (Hampshire) to be tested with a twin-float undercarriage as per Navy request. On 10 November 1934, the seaplane variant of the TSR.II flew and performed its water-handling trials, and then aircraft catapult tests, recovery tests (onboard HMS Repulse). It was given back its wheeled undercarriage and started official evaluation by the state-owned Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (RAF Martlesham Heath).

Pre-production tests (1934-36)

Having met all the requirements in 1935, the MoD ordered a first pre-production batch of three aircraft. By then, the T.S.R II was named “Swordfish” and registered as such within the air ministry and the navy. The three pre-production models had the Pegasus IIIM3 with a new three-blades Fairey-Reed propeller. On 31 December 1935, K5660, first of these, made its maiden flight and on 19 February 1936, K5661 was the first delivered, followed by K5662 completed in the floatplane configuration for extensive Royal navy water-based trials at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (Felixstowe).

Production of the swordfish (1936-39)

By early 1936, the pre-production contract fora large batch of 68 Swordfish was signed. This became naturally the Swordfish Mark I, from Fairey’s Hayes plant in West London. The very first planes were introduced in the Fleet Air Arm by July 1936. The next years would see some modifications and improvements but the production went on without a change in type. By early 1940 however Fairey’s plant were crammed wit orders and at full capacity, including with the planned replacement of the swordfish, the new Albacore.

The Admiralty however needed its Swordfish and approached Blackburn, always close to the Navy, and proposed it to take in charge the manufacture of the Swordfish Mark I. In fact the Navy knew fairey would stop its run soon at Hayes and wanted a full production transfer to Blackburn. The latter, without larger order for the Navy, immediately started to buid from the ground up a brand new fabrication and assembly facility, in Sherburn-in-Elmet (North Yorkshire).

In between the Swrordfish entered legend, notably after its November raid on Tarento and in early 1941, the first Blackburn Swordfish freshly out of the hangar made its flight debut, which was sucessful. Sherburn therefore was stasked to deliver the fuselage, but also final assembly and pre-delivery testings. Indeed the production management started to employ “shadow factories” to mitigate Luftwaffe bombing raids efforts, and major sub-assemblies were setup with four subcontractors, all around Leeds. Parts, tails and wings and other equipments were transported by land to the Sherburn plant.

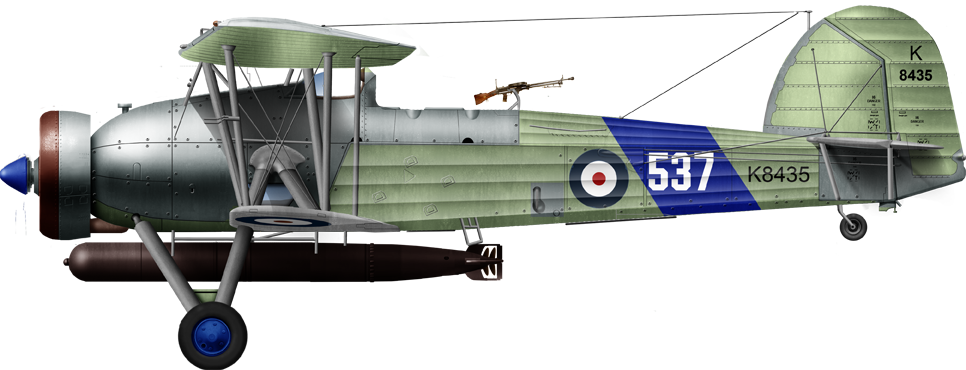

After all was organized, deliveries of completed planes, still Swordfish Mark I standard started in mid-1941 up to 1943. That year, Blackburn had ideas about how to improve the model, which resulted in the improved Swordfish Mark II and the Mark III, the first carrying an ASV Mk.II radar, underwings metal surfaces, reneforced to carry dix 3-inch rockets, and the more powerful Pegasus XXX air-cooled piston radial engine.

The Swordfish III was the same, but with new fittings to carry a centimetric ASV Mk.XI radar this time, placed under band in-between undercarriage legs. This was a pure detection model, sacrificing its torpedo, but rockets replaced by depht charges. At last, on 18 August 1944, it was decided the venerable biplane had reached its own development rope, and the one was delivered that day to the FAA, a production run of nine years, something unheard of in british naval aviation so far.

Some 2,400 aircraft were delivered in all, most of the type II(1080), 692 by Fairey and 1,699 by Blackburn, showing the implication of the former rival in this wartime process. There was even a short “Canadian run”, or Swordfish Mark IV, sole enclosed cockpit version for the RCAN. In between fairey designed and produced the Albacore, and the Barracuda, a quirky monoplane, both replacing the Swordfish with mixed success.

Torpedo examined by the crew and pilot, N°835 Sqn RNAS, HMS Battler 1943

Design of the swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish was a medium-sized biplane with a crew of three to allow an observer/radio, as a reconnaissance aircraft. The whole structure called for a light metal airframe covered in fabric. Since it was a carrier-based model, folding wings were designed, helped by the simple structure and shape of the wings, which were flded on both sides of the fuselage, allowing to stack five or more of them in a row; Something that was quite useful in cramped hangars or decks of escort carriers, like HMS Audacity or the MAC ships (Merchant Aircraft Carriers). These folding wings were also useful in battleships hangars. Like all biplanes of the time, the Swordfish wings used struts, spars, and braces. But the famous nickname “stringbag” came for the apparently endless variety of payloads, equipment carried, compared to housewife’s string shopping bags.

Powerplant:

The Bristol Pegasus was a 1932 nine-cylinder, single-row and air-cooled radial engine designed by Roy Fedden from Bristol. It met soon success both on the civil and military markets in the 1930s and and well at the end of the 1940s. This was a development of the earlier Mercury and Jupiter engines. The last version of the Pegasus was pushed up to 1,000 horsepower (750 kW) based on 1,750 cubic inches (28 L) and a geared supercharger, reaching the pinnacle of its development. In all, over 30,000 Pegasus were built, and the swordsfish was given several variants of the Pegasus along its development.

It was for the main production Mark I the IIIM.3, which developed 690 hp (510 kW). Coupled with a 3-bladed metal fixed-pitch propeller, it gave the following performances:

- Top speed (with tiopedo, 5,000 ft): 143 mph (230 km/h, 124 kn)

- Range: 522 mi (840 km, 454 nmi) normal fuel, with torpedo

- Endurance: 5 hours 30 minutes

- Service ceiling: 16,500 ft (5,000 m) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg)

- Rate of climb: 870 ft/min (4.4 m/s) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg) at sea level

- Rate of Climb: 690 ft/min (210.3 m/min) at 7,580 lb (3,438 kg) to 5,000 ft (1,524 m)

Armaments:

Aerial Torpedoes:

Swordfish being loaded with a torpedo HMS Ark Royal 1941

Its main, primary weapon of choice. The Swordfish was stable and a good pateform for accurate launch, but its low speed called for a long straight approach, always dangerous in the face of a strong FLAK, especially for the Kriegsmarine. Swordfish torpedo doctrine consisted in a first approach at 5,000 feet (1,500 m), and then a dive almost to 18 feet (5.5 m), the ideal delivery altitude for the torpedo. Too high and the latter was likely to eplode on contact or sink, and too low was just plain dangerous for the plane itself, notably because of waves and a still possible “bounce” of the torpedo itself, coming back hurting the biplane.

Torpedo loaded under a Swordfish onboard HMS Illustrious

The parth chosen also depended of the range of the early Mark XII aerial torpedo used: 1,500 yards (1,400 m) at best. This could be crossed at 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph), but with a larger setting, it could be extended to 3,500 yards (3,200 m) at 27 knots. The torpedo first travel course was 200 feet (61 m) after release, but stabilized after 300 yards (270 m), at the preset depth, while the warhead detonator armed itself. Training and combat shown pilots preferred to shorten distance down to 1,000 yards (910 m) from their target and use max speed. However, reaching that stage meant having to pass through a wall of shrapnel.

Dive & strafe Bomber:

Aft armament: Lewis MG

With its sturdy structure, the Swordfish was also tested as a dive-bomber. In 1939, a few from HMS Glorious made comparative dive-bombing tests and 439 runs to find the most acccurate diving angle. The latter proved to be about 60, 67 or 70°. HMS Centurion was the target ship, and as she was stationary the average error margin was within 49 yd (45 m) from around 1,300 ft (400 m) at 70°, but it went down to 44 yd (40 m) from higher at 1,800 ft (550 m) but at 60° which was far easier to recover and spared the strcture. Nevertheless, the Swordfish was found to operate underwings incendiary bombs with some success.

As ASW patrol plane: DCs and Rockets

Installing rockets under a swordfish from Sqn 834 Sqn, HMS Battler

Since Fairey delivered two more modern and capable torpedo attack models, the Royal Navy wanted its biplane to be converted as a pure ASW aircraft, something new and still untested in 1942-43 for small planes. For this anti-submarine role, the Mark II, with its reinfiorced underwings could now engage surface U-Boats about to submerged with rockets, and for those submerged and spotted, with depth charges. The 60 lb (27 kg) RP-3 rockets and DCs were often used for the start onboard small escort carriers, like the MACs. In that case, especially on the northern route, air was cold and the deck was short enough to have onboard Swordfish equipped with rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO) systems. The great issue of the Swordfish when attacking, its slow speed, proved to be a blessing when landing and takeoff from small decks. The carrier for example did not needed to leave the convoy to try to steam into the wind. It was even tested when the carrier was at anchor and the wind blew strong enough.

Variants of the swordfish

Swordfish Mark I: First production.

Swordfish Mark I seaplane, for catapult-equipped warships.

Swordfish Mark II: Metal lower wings to fire rockets (1943).

Swordfish Mark III: New Centrimetric radar for low visibility (1943).

Swordfish Mark IV: Fully enclosed cabin (only used by the RCAF in 1944).

Operational history:

Early service, 1940-41

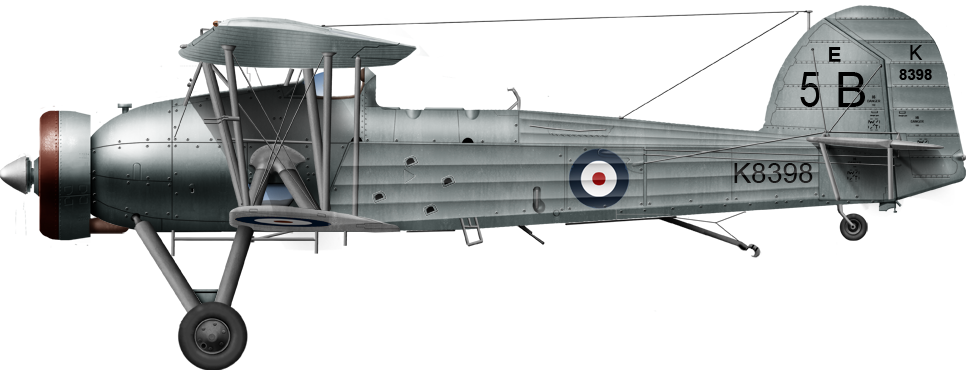

In July 1936, the Swordfish entered service with the Fleet Air Arm, showing with the 825 Naval Air Squadron. It started gradually to replace the Fairey Seal as spotter-reconnaissance plane, but also the Blackburn Baffin as torpedo bomber, and went in competition with the Blackburn Shark, which quickly replaced in turn by the Swordfish. All Seal and Sharks were sent to the far east, verse to schools or confined to coastal bases and reserve. In 1938, the Swordfish was the sole torpedo-bomber/recce model in the FAA, but the Albacore was intended to replace it in 1940 (it first flew aso in 1938). This never happened, as the latter, with a small production run of 800 was superseded quicky by the controversial Barracuda.

In September 1939, the FAA was no longer prt of the RAF but now controlled fully by the Royal Navy. In total, the FAA operated 13 squadrons equipped with the Swordfish Mark I, plus three flights of Swordfish seaplanes based on cruisers and battleships. 26 FAA Squadrons were soon equipped with the Swordfish and 20 second-line squadrons as well, for coastal patrols and training. 1939 ended with a record of dull fleet protection and convoy patrols.

Norwegian Campaign

The first large scale engagement and clashes with the Kriegsmarine started in Norway, where on 11 April 1940, several Swordfish took off from HMS Furious to attack the German flotilla in Trondheim. However they only spotted two two enemy destroyers, registering one hit only, but it was the first of such attack in WW2. On 13 April 1940, a floatplane version from HMS Warspite spotted and sent radio corrections during the Second Battle of Narvik, playing an instrumental part in the shelling accuracy that devastated eight German destroyers. Later, U-64 was spotted by a Swordfish which tried to dive-bomb it, scoring a direct hit. This became the first U-Boat sunk by the FAA at that point. Swordfish patrolled and attacked opportunity targets off Narvik during the following weeks. They also attacked German land facilities and aerodromes. Anti-submarine patrols coupled with reconnaissance went on despite the terrible weather. This campaign saw also the first nighttime landings on a carrier, also performed by Swordfish.

Mediterranean Campaign

Swordfish and Fulmars onboard Ark Royal

During these three years of heavy fighting (late 1940 – late 1943) Swordfish squadrons really won their laurels. They operated from HMS Ark Royal in particular, but many other carriers, notably those of the Illustrious class. On 14 June 1940, the Italians were at war, and nine Swordfish (767 NAS) based at the time in the Suth of France, at Hyeres, took off for a bombing raid on the industrial ligurian coast. 767 Sqn moved to Bone in Algeria as France collapsed, and joined afterwards RAF Hal Far on Malta, now as 830 NAS. On 30 June they raided fuel tanks in Augusta, Sicily.

On 3 July 1940, Swordfish from Ark Royal were committed in the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, in all twelve from 810 and 820 NAS, which mines the entry of the harbour to avoid any vessel to escape and also directly torpedo anchored fleet. The French battleship Dunkerque was badly damaged after an ammunition barge nearby detonatd after being hit by a torpedo, and other ships were damaged. This acted a bit a rehearsal for the future attack on Taranto. Three Swordfish were also sent in support of the British Army in the Western Desert, searching for axis vessels operating off the coast of Libya. On 22 August alone, they sank two U-boats, one destroyer and a supply ship in the Gulf of Bomba.

Equipment passed two a Swordfish crew in North Africa

On 11 November 1940, HMS Illustrious made a night launch of its squadrons over Taranto, after extensive preparations and planning going back to 1938. Pilots had been trained for night flying operations. This was the only way to circumvent the good AA defences of the harbour. After firing flares, Swordfhish torpedo planes started their attacks, while others made bombing runs, despite of AA and barrage balloons, torpedo nets. The synchronised attack was deadly. Six Swordfish with torpedoes badly damaged three battleships, while the “bombers” hit two cruisers, two destroyers and other ships. The agile “stringbag” showed it could even evade anti-aircraft fire. The case was to inspired greatly the Japanese. It was a game-changing event. In fact, Takeshi Naito, German attaché made the trip to Taranto to see the results and sent a detailed report to Tokyo.

A rare photo showing a Swordfish floatplane version carrying a torpedo (from twitter)

On 28 March 1941, two Swordfish based from Crete torpedoed Pola, which provoked the turning point of the Battle of Cape Matapan. Also in May 1941, six Swordfish from Shaibah (Basra, Iraq) successfully dealt with the insurgents (Anglo-Iraqi War). For the remainder of 1941-42 operations, the best and most used squadrons were in Malta. They targeted enemy convoys in the dark to avoid the Luftwaffe. However on 27 Swordfish were in Malta at all times, but they nevertheless claimed 50,000 tons of enemy shipping monthly over 9 months. By their action alone they hampered supply efforts to North Africa, plaguing Rommel’s operations. One month in particular, they sent to the bottom some 98,000 tons of shipping. This became such a problem a massive invasion operation was planned, plan C3, eventually never realized. Losses were few in exhange, despite the difficulty of night flying.

Atlantic operations of the swordfish

The Swordfish crews that successfully attacked and hit the Bismarck

In May 1941, during the famous hot pursuit of KMS Bismarck, Swordfish Squadrons participated actively, especially at the end of its rampage, when separated from KMS Prinz Eugen and en route to the French coast. On 24 May, nine Swordfish from HMS Victorious made a first sortie (825 Naval Air Squadron, Lt Cdr Eugene Esmonde) late in the day but due to poor weather mistook HMS Suffolk for the battleship. After returning to the carrier for reloading, they took off again, at falling night, in deteriorating weather conditions. They used the ASV radar to spot and attack Hitler’s mighty battleship. It was often saif that it’s the slow speed of the Swordfish and calibartion of FLAK guns, setup for faster flying aircraft, that contributed to a relatively weak number of kills.

Onboard HMS Victorious, May 1941, these Swordfish are going to take off and find Bismarck

In any case, on the 24/25, Bismarck used its secondary artillery (6-inches) guns to create massive splash around the planes, at the lowest possible depression. The very low altitude of these planes is perhaps what really helped the most, rather than a discrepancy in speed. Many were hit by splinters, but all survived but missed. Just one made a particularly lucky hit, which struck amidships the main armoured belt, causing minor damage. However, Bismarck has to stop at night ot repair, this contributed to see her pursuers catching up. On 26 May, Ark Royal’s (Force Z from the south) launched two Swordfish strikes, the first missing the battleship, and the second second scoring two hits. The last one in particular was the most critical, as it jammed the ship’s rudders at a 12° port, as Bismarck was veering furiously to avoid these. This doomed her to run circles, later pounded to death by the British battleships. But this was the only significant surface warfare episode to that point. U-Boats were a far more common occurence.

Swordfish wings being folded, HMS Sparrohawk, RNAS Haston (Orkneys)

Therefore, from mid-1942, the Swordfish was gradually retired from fleet carriers as she was replaced by the new Fairey Albacore and Barracuda. Instead they were versed to smaller escort carriers, in the new role of submarine-hunter, in which its revealed itself as a formidable asset in the battle of the Atlantic. Equipped with radars (notably the Mark 2 and retrofitted Mark 1s) both detected and attacked U-boat packs mercylessely. They were also used in the Arctic convoys to Murmansk, but maintaining these in such icy conditions was nightmarish. Despite of this, Swordfish prove dit was very dependable. In addition to attacking U-Boats, they would guide destroyers and coordinate their attacks by radio. Those from HMS Striker and HMS Vindex notably flew 1,000+ hours for ten days, virtuall in the air non-stop, taking turns to have at least four patrol planes at all times searching on all quadrants.

Despite its large size for the cramped escort carriers, Swordfish easy handling and slow speed made landings far more easier than with any other model of the time, even in rough seas.

In some cases, there was not even a hangar, and the Faireys were stationed on the deck at all times. This was true especially when combined with the merchant aircraft carriers (“MAC ships”). Over 20 of them carried three or four of them, all equipped for ASW with convoys. Three of these were even Dutch-manned, and the Sqn 860 (Dutch) Naval Air Squadron were a bit unique in that regard. British MACs spread between them the 836 Naval Air Squadron, the largest operating the type with 91 in 1942-43.

Mark IIIs, No 119 Sqn, Knokke le Zoute, Belgium, 1945

Unlikely operators:

RNAS Puttalam in ceylon

A Swordfish Mark 4A fell into Italian hands after the Battle of Taranto, landing where it could after being hit. It was examined throughly. Another was K8422,from HMS Eagle. It was shot down and after the Maritza airfield in Rhodes, on 4 September 1940. The first was evaluated at Guidonia Test Centre and flew until the lack of spares by mid-1941 while K8422 was cannibalised.

Anotether namd P4127 (4F), 820 NAS, HMS Ark Royal, was hist by FLAK during a bomb raid on Cagliari (Sardinia) and landed at Elmas in August 1940. It was sent to be repaired by Caproni, using an Alfa Romeo 125 engine. This quite unique hybrid was tested also at the Stabilimento Costruzioni Aeronautiche, Guidonia, in February 1941 and still extant in April 1942. Oustide the Italians, the Spanish also used it during WW2: Swordfish W5843, 813 Sqn based in Gibraltar lost its bearings and landed, gasoline-dry, between Ras el Farea and Pota Pescadores (Spanish Morocco) on 30 April 1942. Another, P4073 (700 Sqn, HMS Malaya also ran out of fuel after tracking Scharnhorst, on 8 March 1941. As it was a floatplane, it was intercepted by the Spanish liner Cabo de Buena Esperanza, off Canary Islands. It became HR6-1, integrated in 6 December 1943 with the 54 Escuadrilla at Puerto de la Cruz in Tenerife (Canary) and served until 1945.

Fairey Swordfish floatplane, HMS MALAYA October 1941.

Swordfish Coastal Command

Rocket armed Fairey Swordfish training flight RNAS St Merryn Cornwall 1 August 1944

In early 1940 already, the 812 Squadron was versed to the Coastal Command and started operations against occupied ports along the English Channel. They notably deployed naval mines at their entrance to blockade and hamper traffic. This was challenging, requiring precision navigation skill, and extra range, so additional fuel tanks installed in the crew area, sacrificing a crew member. RAF fighters covered them for part of the travel, or if the range allowed it, create a defensive perimeter against the Luftwaffe.

Coastal Command’s Swordfish operations rose to four Swordfish-equipped squadrons in mid-1940. Bases were Detling, Thorney Island, North Coates and St Eval. They hit the coasts of Netherlands and Belgium by day, and by night attacked oil installations, power stations and airfields. After the French Armistice, French ports became their prime target, especially when it was feared an invasion. In February 1942 however, the “stringbag” coild not do much during the “Channel Dash”. Six Swordfish (Lt. Cdr Eugene Esmonde) took off from Manston and started an initial attack run astern of the fast ships, until interecpted by no less than 15 Messerschmitt Bf 109 from the coast, and all shot down before making a single hit. In all, 18 Swordfish crew were killed, including Esmonde, awarded the VC posthumously. It was commented as a gallant attack, albeit doomed from the start, redeeming the fiaco.

MkIII, 119-Sqn RAF B58 Knokke le Zoute Belgium

Their courage was also noted by German Vice-Admiral Otto Ciliax. Following this, the admiralty decided to retire the type for good as a torpedo bomber. From there, the Swordfish definitely became an ASW patrol plane.

Soon, the Fairey Swordfish was the first equipped by the surface vessel (ASV) radar, first implementation on a carrier-borne aircraft. This allowed the Swordfish to locate surface ships at night and in bad visibility. From October 1941, ASV radars-equipped squadrons started operations. By December 1941, a Gibraltar Swordfish, just equpped with the radar was the first to claim an U-boat by night time. In May 1943 a Swordfish claimed U-752 off Ireland with rockets for the first time also.

Fairey Albacore

Fairey Barracuda II of 814 Squadron, its successors. Both were outshined by the Swordfish

In 1945, Swordfish II with rockets and radars operated from the Belgian coast, hunting by night, the onlly moment where German midget submarines operated in the area. Their new centrimetric radar was efficient over 25 miles to spot relatively small boats.

So the was was going to an end, seeing the first jets in combat, whereas the venerable biplane was still equipping nine frontline ASW squadrons, claiming 14 U-boats. The most amazing was that in mid-1945, the Fairey Albacore had been already replaced by the Fairey Barracuda. The last sorties were performed along the coast of Norway (835 and 813 Sqn). On 21 May 1945, 836 NAS, the last deployed on MAC ships, was disbanded after V-Day in Europe. But this was not over.

A training squadron still flew its Swordfish in the summer of 1946. Most of these famous birds ended in scrapyards, but due to fond mempry by pilots and privates initiatives, many survived today, including one completely rebuilt and another resored in flying conditions.

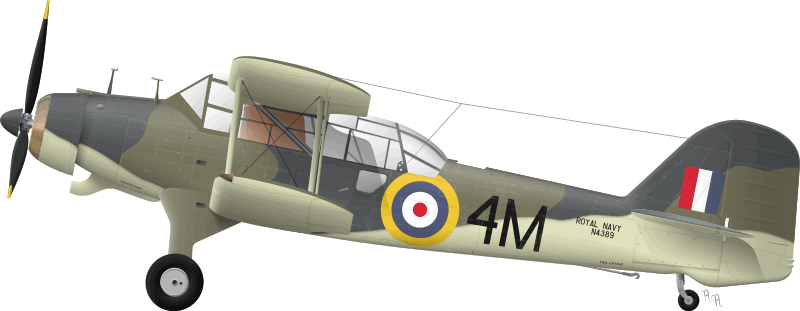

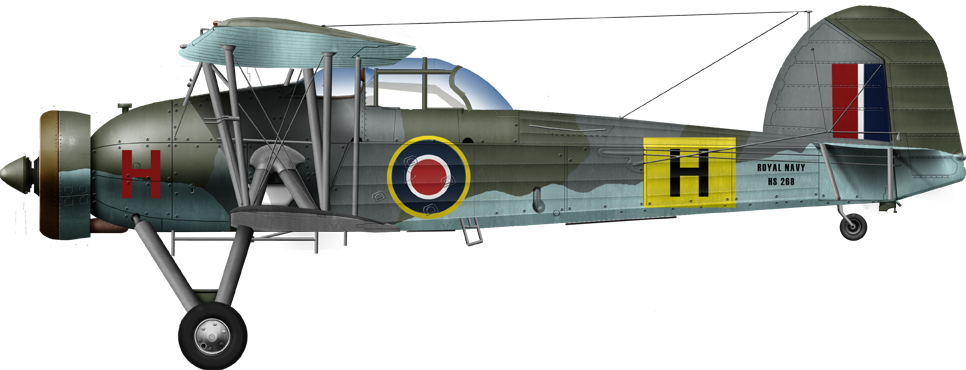

Fairey Swordfish Mk1 profile cc

Specifications Mark I |

|

| Dimensions: | 9.56 x 10.97 m x 4.50 m (33 x 41 x 13 ft) |

| Wing area: | 342 sq ft (31.8 m2) |

| Airfoil: | NACA 0010 – NACA 2212 |

| Weight: Light | 3,788 lb (1,718 kg) |

| Weight: Max take-off | 5,437 lb (2,466 kg) |

| Propulsion: | P&W R-1340-18 600 hp (450 kW) |

| Performances: | Top speed: 48.6 kn (55.9 mph, 90.0 km/h)

Cruise speed: 116 kn (133 mph, 214 km/h) Service ceiling: 14,900 ft (4,500 m) Rate of climb: 915 ft/min (4.65 m/s) |

| Range: | 587 nmi (675 mi, 1,086 km) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) |

| Armament – MGs | 2x 0.3 cal |

| Armament – Bombs | 650 lb (295 kg) |

Operators and surviving examples

Australia The RAAF operated six in No. 25 Squadron, 1942.

Canada Many used by both the Royal Canadian Air Force and RCN.

Netherlands Royal Netherlands Navy (in exile), No. 860 (Dutch) Sqn FAA

United Kingdom

No. 8, 119, 202, 209, 273, 613 Sqn RAF, No. 3/4 Malta, Gibraltar, Singapore

RNAS 700, 705 (floatplane, Repulse, Renown), 771, 810, 811, 812, 814-825, 835, 836, 838 Squadrons.

Read More/src

Classic Aircraft – Fairey Swordfish

Fairey Swordfish MkII mars 2013 flight footage Malcolm Auld

Testimonies of veteran pilots – Armoured Carriers Channel and website.

The model corner

-Trumpeter, Ark Models, Tamiya, Smer, Airfix, SMK

-Squadron signals book. The swordfish in action.

Gallery

Author’s illustrations: All Liveries

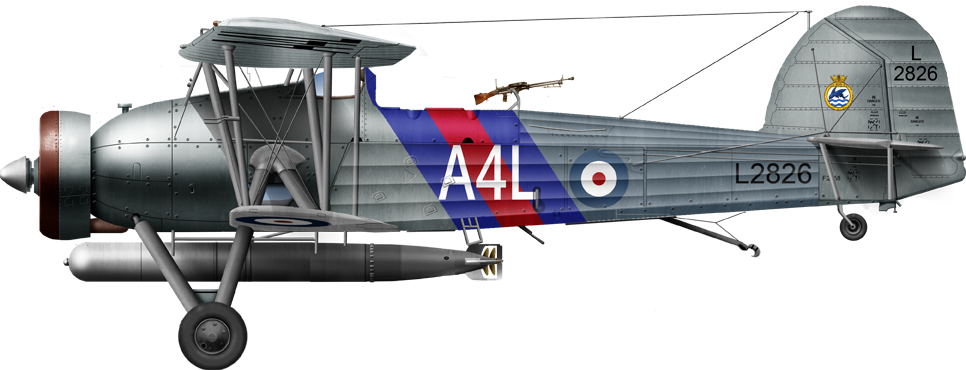

Swordfish Mark 1, HMS Eagle, 1938, painted in medium gray overall

Mk.1 from Sqn.810 NAS Courageous, 1938, still showing its canvas, 810 Sqn. blue markings

Mk.1 of Sqn 810 RNAS HMS Ark Royal 1939

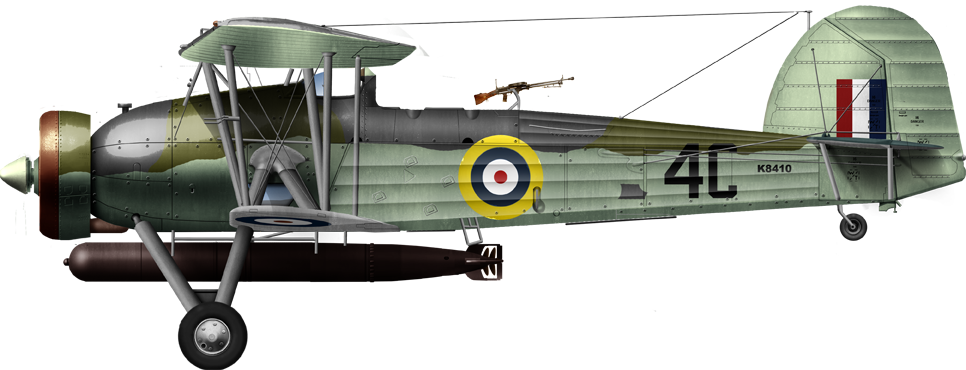

Mk.1 Sqn 810 NAS HMS Eagle, 1940

Mk.1 2nd.Sqn. 810 NAS, HMS Ark Royal, north sea 1941, the plane that hit Bismarck’s rudder.

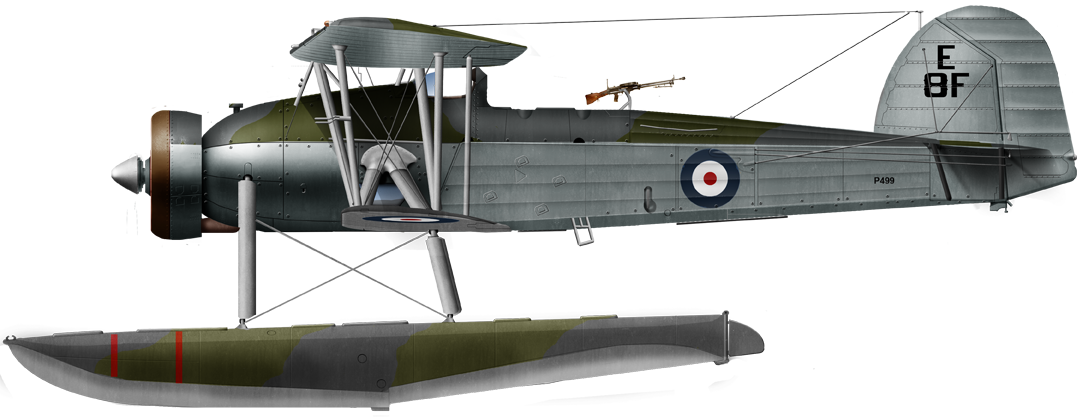

Fairey Mark I floatplane, NAS 702 HMS Resolution, 1941

Mk2 815 NAS, attack on Lorient, 1942

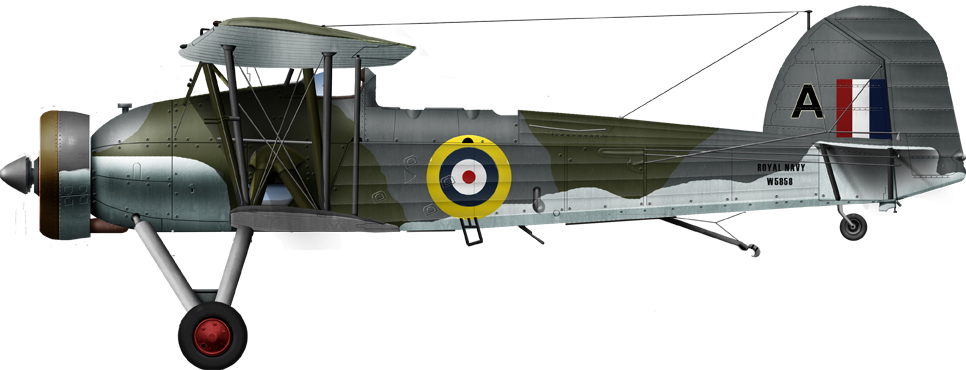

Mk2 837 NAS HMS Dasher, North Atlantic 1942

Swordfish Mark II from 811 Sqn, HMS Biter, 1944, with rockets

Mark II, 819 Sqn, 1944

RCAN mark III in 1944

Mark IV from the Canadian 1st naval air gunery school, late 1944

Additional photos

A swordfish lifted from the hanger of HMS Attacker in 1943

A Swordfish above from HMS Eagle – Flickr

A squadron of Swordfish in flight (WoW ingame screenshot).

St Merryn Swordfish used as target tug

![]()

Sqn.816, HMS Tracker

Rocket-assisted Swordfish RNAS

Swordfish Mk1, No785 Sqn FAA RNAS Crail, Scotland

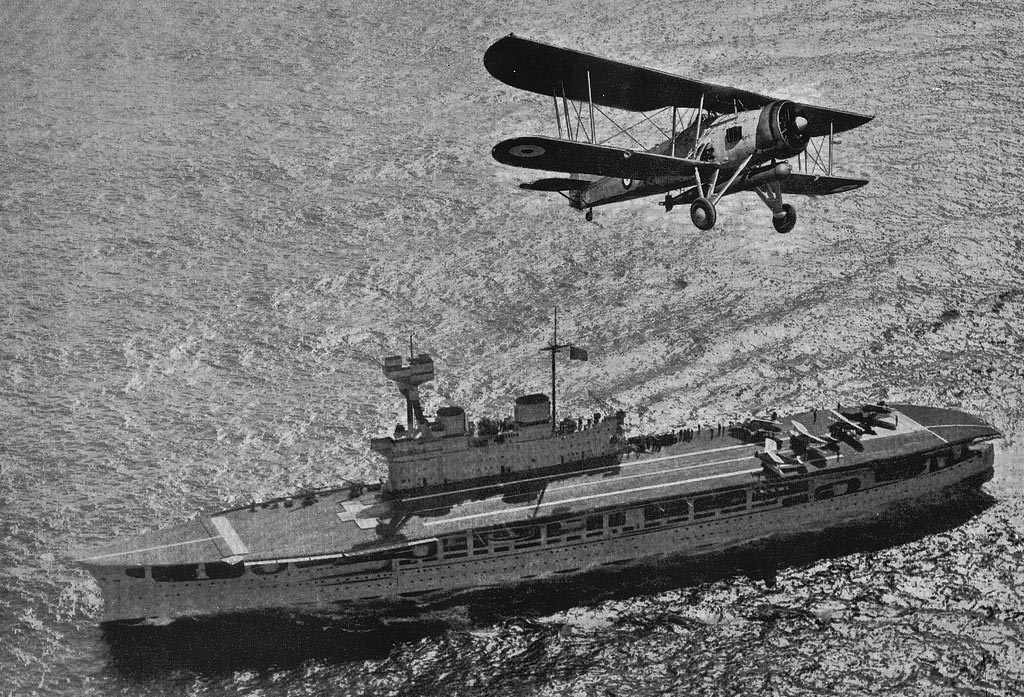

Flyover HMS Indomitable

Swordfish from 860 Sqn.

Swordfish crew onboard HMS Battler

St Merryn was a main swordfish training center, situated in Scotland

Sqn 785, RNAS Crail

![]()

![]()

Swordfish from Sqn 816 onboard HMS Tracker

Swordfish Mark III based in Ireland 1944, note the underwings rocket boosters

Swordfish II from Sqn 824

![]()

Swordfish onboard HMS Tracker

Swordfish 860 Sqn

RNAS Hatston

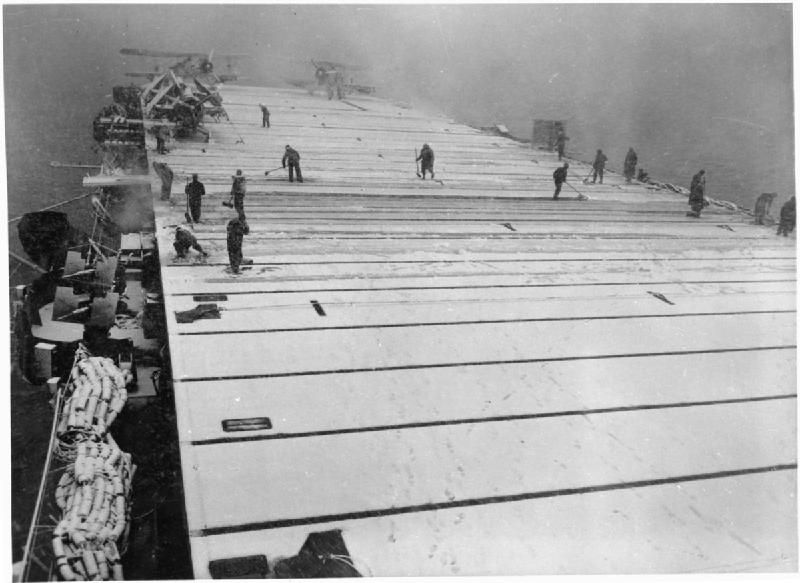

HMS Fencer clearing snow swordfish

![]()

Fairey Swordfish taking off from HMS Tracker 1943

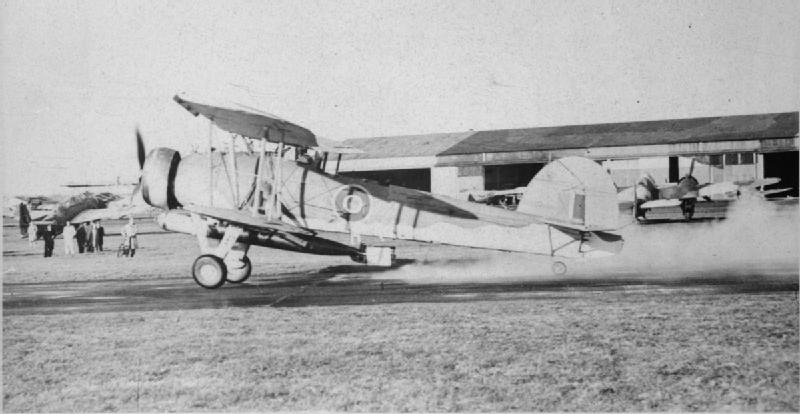

Fairey Swordfish on Airfield

Fairey Swordfish Mk2 C-GEVS

Fairey Swordfish MkI training flight from Crail Scotland 1940

Fairey Swordfish II LS326 L2_tail detail

crew training torpedo dropping Fleet Air Arm station HMS JACKDAW Crail

119 Sqn B65 Maldeghem Begium 1945

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Good article but really could do with editing for typos

Many Thx ! i know many articles had such typos, but the team has a spellchecker, actually hard at work on these.

All best !