Spanish Armada vs

Spanish Armada vs  US Navy

US Navy

Cuba’s decisive naval battle

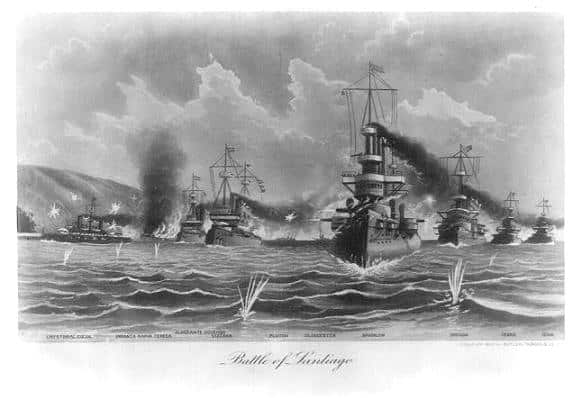

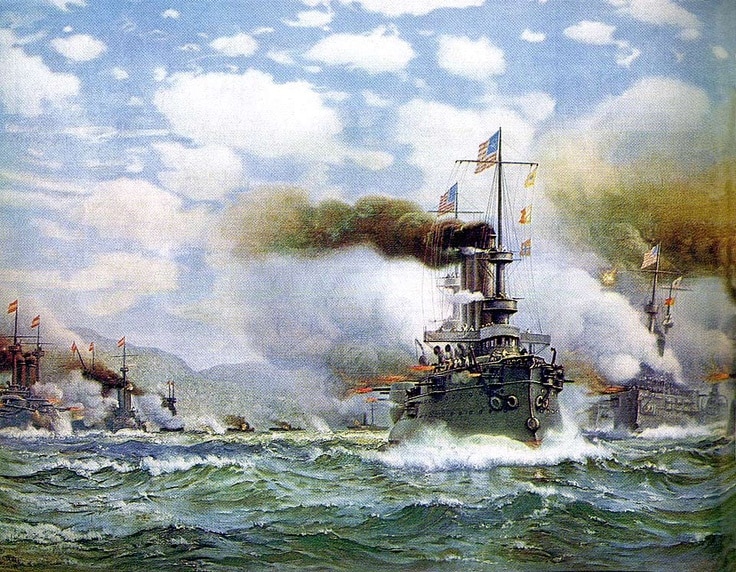

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba, was seen by some as a naval “execution squad”, as US ships (with large firepower superiority) just awaited the Spanish squadron to leave and force its way out of Santiago’s bay. Some duelling occurred nevertheless, but the fate of the Spanish fleet in the Caribbean was decided this 3th of July, and all but precipitated the end of the war (and of the Spanish Empire).

Forces in Metropolitan Spain

By the time the war erupted over Cuba (and the sparkle which was the explosion of the Maine), Spain had its only ironclads and battleships, the Pelayo, and older Vitoria and Numancia in drydocks at La Seyne at Toulon, while the Mendez Nunez was in reserve, as well as the coastal battery Duque de Tetuan (1874) and the training ship Puigcerda, a monitor from 1874. The Emperador Carlos V and the Princesa de Asturias has been freshly accepted into service but were stationed at Cadiz and Cartagena, carrying out patrols during the war. Most of the torpedo boats were also stationed in Spain.

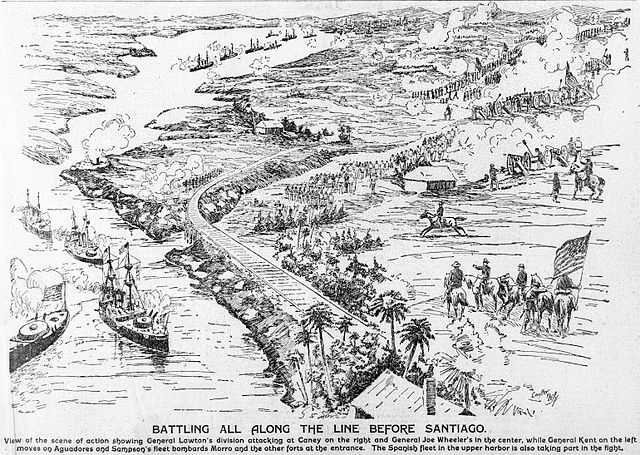

Author’s map of the battle of Santiago

Cervera’s squadron

In Cuban waters, the colonial squadron at the time of declaration of war was composed of a few minor units, while a strong squadron was just being assembled at the Cape Verde Islands, headed by Admiral Ocquendo. He commanded the armoured cruisers Vizcaya, Infanta Maria Teresa, Cristobal Colon, the destroyers Furor, Terror and Pluto, under the command of the best Spanish admiral, the respected Pascual Cervera y Topete. This officer and Gentleman, 59, was a former minister of the navy with 47 years under his belt, notably in Cuba that he knew well, as well as in the Far East. Cultured, polite, competent, courageous, he was appreciated by the court but much more by his men.

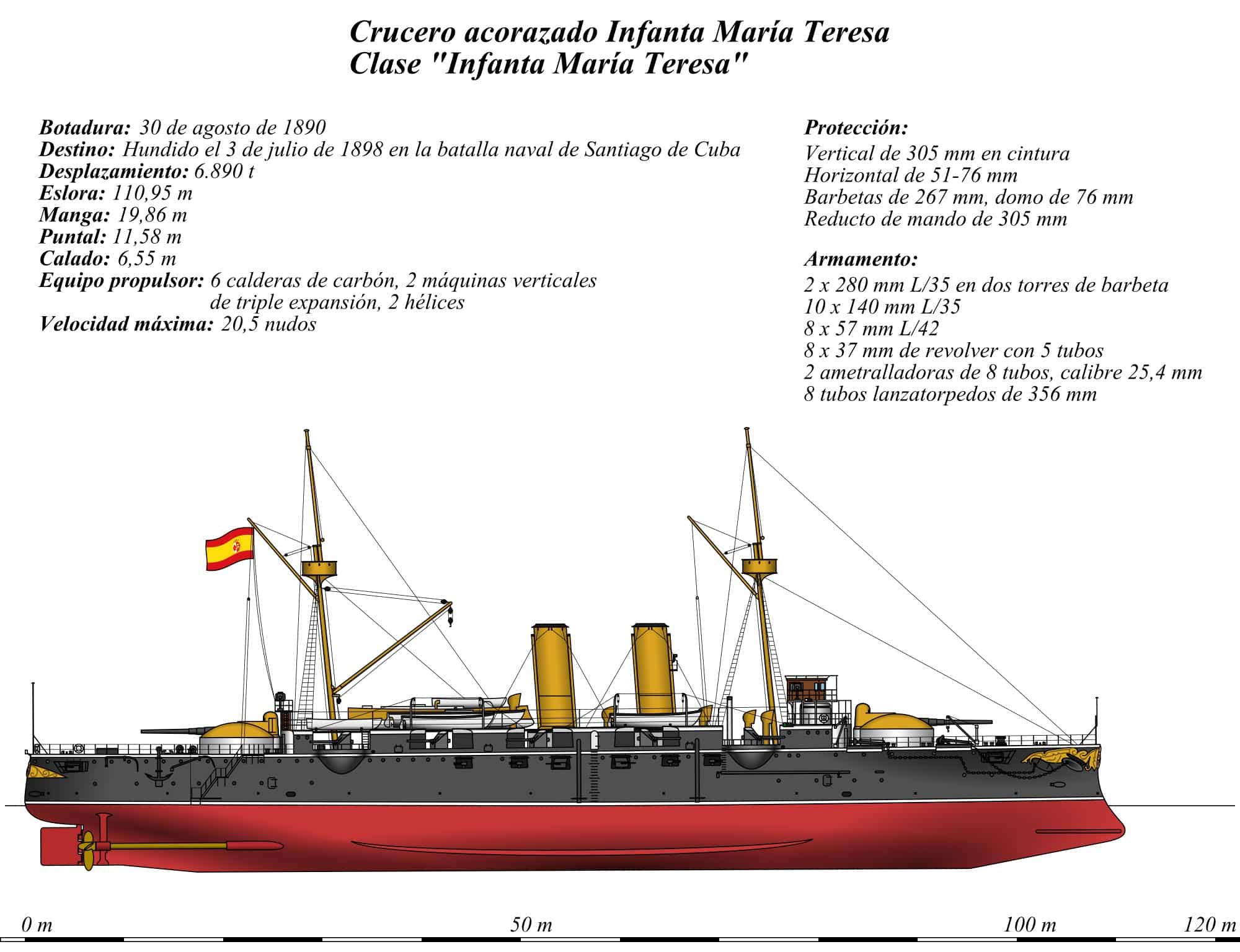

Spanish armoured cruiser Infanta Maria Teresa

At the time of declaration of war, Cervera proposed to Madrid that the fleet waited in the Canary Islands, as the U.S. Navy would not fail to track the coastal metropolitan areas, combining his forces with the squadron of Cartagena, sent as reinforcement. He planned to take in a pincer the “Yankees” and inflict them a crushing defeat. All his commanders had approved the plan. But to his dismay he learned that his orders were instead to defend Cuba as quickly as possible. He then departed in the same sad resolution than Admiral Sir Charles Cradock, sent to sacrifice against Spee’s superior ships off the Falklands.

He knew well that on paper his forces were outclassed by number and tonnage by the American ships, compounded by the fact they suffered from a poor supply of shells, had breech blocks issues left unaddressed, lack of maintenance (no fooling) such as Vizcaya could barely sustain 12 knots, not to mention the Cristobal Colon, which was so fresh she still then missed her main guns.

Profile of the Cristóbal Colón prior to the battle. Notice the forward turret is there, but the gun is absent. A dummy one was fitted at the rear. It would have been one 254 mm (10 in)/45 cal. gun. Secondary armament comprised still two 8 in (203 mm)/45 cal. guns

and fourteen single 152 mm (6 in) guns. She has been sold shortly after completion to the Spanish Navy at Genoa on 16 May 1897.

Departure

Nonetheless the fleet leaved St. Vincent on April 29, 1898. A long detour which -it was believed- the squadron would run out quickly from coal, therefore the Americans thought it would rather join the fortified port of Puerto Rico first. Meanwhile on May 1, far away in Cavite (Manila Bay) in the Philippines, an American fleet sank at anchor, by surprise, the Spanish Pacific fleet. Back in the Carribean, Sampson knew he must also necessarily score points, even if only for the sport. But Cervera’s squadron was a far more serious prey than the collection of old colonial gunboats in the Far East. On May, 4, Admiral Sampson tried to intercept Cervera on its way to Cuba. On May 11, Sampason arrived at San Juan, and began to shell the harbor, thinking Cervera was there already. Faced with the evidence of his absence, he decided to sail back to Key West. He was to coal in Martinique and headed for Curacao.

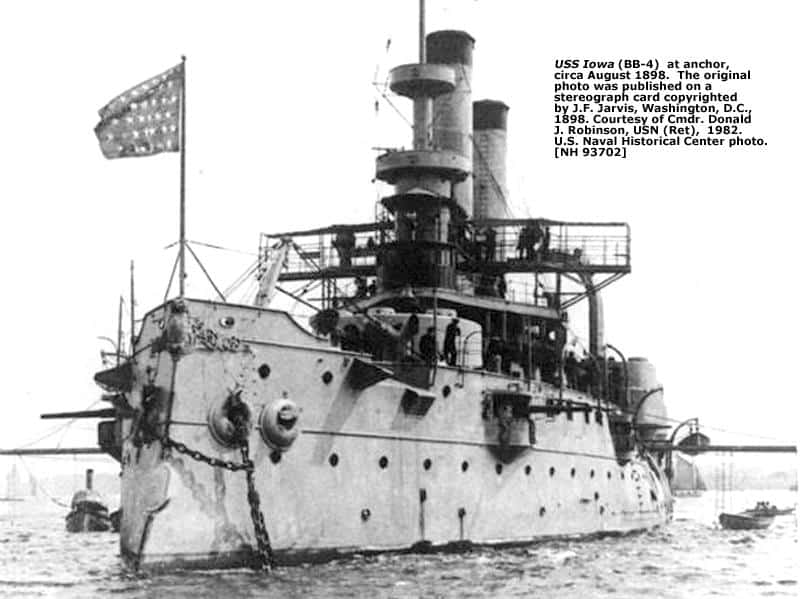

Battleship USS Iowa

Then he returned to Key West where he was joined by Schley’s squadron on May 18. Key West was not far from Havana, so it seems unlikely that Cervera would try to risk lifting the blockade. It was believed the squadron would settle in the south of Cuba, to be anchored under the protection of the fortified ports in this area, at Cienfuegos and Santiago de Cuba. The combined American squadron, now under the command of Schley sailed to Cienfuegos. American confidence in the outcome of the battle ahead is such that the US Navy squadron is surrounded by a picturesque array of luxury yachts attending a “picnic” in case. However some of these Yachts has been equipped after requisition, such as USS Gloucester, sharing his part in the heart of the battle.

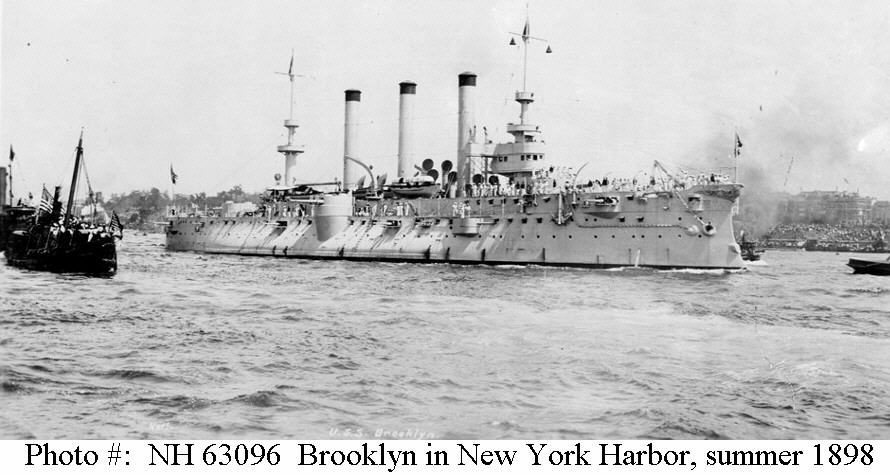

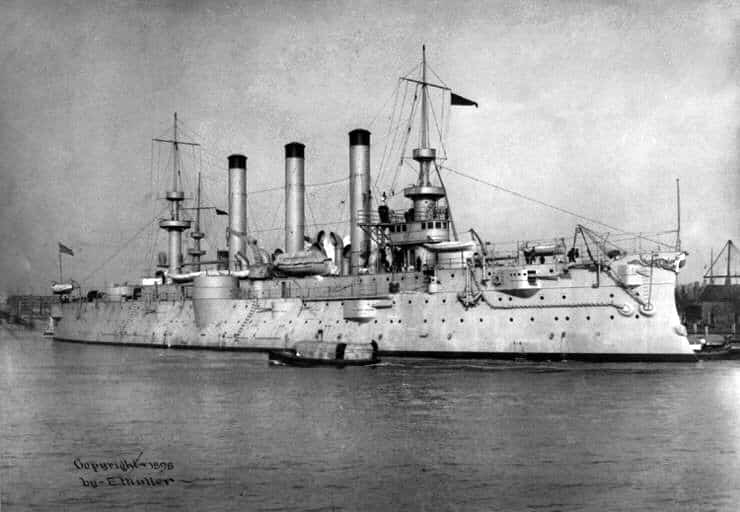

USS Brooklyn (ACR3), perhaps the most recognizable and famous American armoured cruiser of that era.

Arrival and deployment

The 22, at Cienfuegos, the eye in the telescope, Admiral Schley observed the apple mast emerging from the hills hiding the harbor, judging how many ships are present, but failed to identify them formally. Are they those of Cervera? The next day a messenger joined the squadron with a message confirming Sampson’s order to stay put. A few hours later, he received another one ordering to sail quickly to Santiago, as rumors indicated the Spanish Admiral was anchored.

But Schley then still felt that the presence of cervera at Cienfuegos was still possible. On 25, Sampson’s cruiser arrived with the first copy of the message, reiterating the order to steam to the port of Santiago, that he hid reluctantly. At dusk, he learned by the commander that Cubans resistants signalled by three shafts of light from the window of a house near to the harbour the Spanish fleet was there. Schley received later formal confirmation from other sources. He could then no longer remain in doubt.

Another view of the USS Brooklyn, the battle’s hero

Coaling and preparing for battle

Schley could not intervene however right away: He was to wait for Weather conditions were rapidly deteriorating, and his coaling fleet still struggling to separate, like the Merrimack still tied due to serious problems of boilers. At 20 nautical miles from Santiago, he sent three ships to try to see the Spanish fleet. They come back empty. Schley decided nevertheless, fearful of falling short of coal decided to return to Key West to refuel, to the dismay and wrath of the Secretary of the Navy for whom that move confined to insubordination. He sent an urgent telegram on May, 27 classified “top priority” by which he intimated Schley to stay.

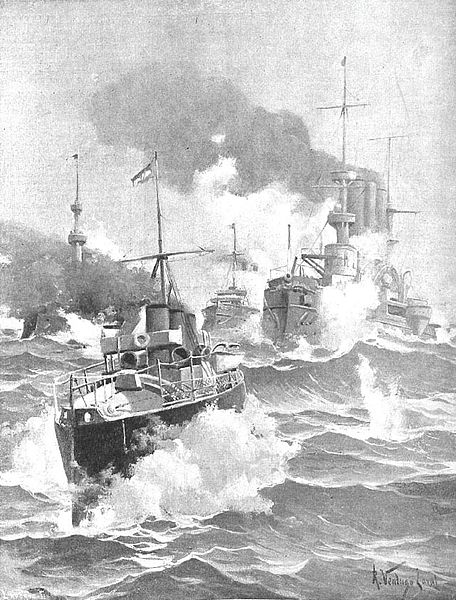

Idealized painting of the battle, showing Schley’s brooklyn leading the line. In reality this clean “battle line” duel never happened.

Fortunately, the admiral gave up on the idea to leave the area, even before receiving the telegram, as the sea calmed down, and the coaler Merrimack eventually be able to deliver his payload and exit. He the took all his squadron on May 29, and parked his battleline in front of the mouth of the harbor. He could see from there the glow of sunset falling on the Cristobal Colon and planned action for the next day at dawn.

First shots on the Cristobal Colon

As planned the next day, American ships opened fired and the duel was rapidly unequal but yet, shells missed. The Colon escaped and joined the rest of the squadron, to be placed directly under the protection of Santiago’s forts. The day after, Sampson joined Schley’s squadron.

Santiago’s siege

U.S. forces began a fully-fledged siege of the harbour. Cervera had its only exit cut off, but still had the possible double cover of darkness and bad weather. But still, the sea remains of oil. For their part the two admirals do not intended to force the Bay: Large batteries commanding the mouth of the harbor and approaches were a real threat, not to mention long-range batteries in the fortified port itself, and mines laid across the mouth. On the other hand, they could wait for General Schaft that landed nearby, aimed at taking the city and harbour with his troops and capturing forts and batteries, forcing Cervera to leave the harbor.

Meanwhile Sampson, who hoisted his mark on the Armoured Cruiser New York, just developed an ingenious plan thanks to the inspiration of RP Hobson, a naval lieutenant and brilliant engineer: They were to send the old Merrimack through the mouth, lights off, machines shut, helped by the currents and momentum. Then the steamer would to be scuttled after maneuvering across the entrance and firmly anchored with her carefully placed charges set to detonate and scuttle her. Thus, she was to cut off any possibility of retirement for Cervera’s squadron.

Illustration of the battle.

The operation was conducted on the night of June 2-3, but proved a failure: The steamer, still hampered by boiler pressure problems was poorly operated, and eventually scuttled but into a position and place still allowing Cervera to escape. For his part, the latter had in a few days carried ashore most of his sailors with all weapons available to strengthen lines of defense to the rear against Schaft, which was approaching dangerously. Before news of the American commando arrived, “Captain General” Blanco, governor, and commander in chief of Cuba, ordered Cervera to leave the harbor in force, yet still unmanned and under-supplied.

Cervera’s options

Cervera studied his (bleak) possibilities: Exiting by night was to take the risk of managing his way across in the narrow mouth of course and always possible collision with the Merrimack. After careful consideration, he decided to sail on Sunday, July 3rd, at nine in the morning hours, when traditional religious services in the United States Navy took place (Yamamoto had this detail in mind years later when planning his attack on Hawaii). From Saturday two o’clock in the afternoon, boilers had to be set in motion while the sailors stationed at the front lines in the back of the town would return urgently to prepare the ships to depart.

Cristobal Colon. A recent armoured cruiser built in Italy (Garibaldi class), she was so new that the main battery has not yet even been installed.

Cervera’s squadron strength

The Spanish squadron consisted of the cruisers Almirante Oquendo, Vizcaya, Infanta Maria Teresa, and Cristóbal Colón plus Villaamil’s destroyers Pluton and Furor. The 7,000 tons cruisers were not heavily armored, nor armed at least compared to the US battleships. With At best they displayed two 11 inch guns and ten 5.5 inch guns (Infanta Teresa Class) each. In addition the condition of the ships was rather poor, The breech mechanisms were dangerously faulty, boilers were in need of repair, some even needed intensive fouling treatment in drydock. The best protected was the Italian-built armored cruiser Cristobal Colon, but she still lacked her main battery, dummy guns being placed. Crews were also poorly-trained, mostly in gunnery drills, concentrating on rapid fire at regular intervals.

The Battle

Cervera leaves the bay

On July 3, at 9:00, as expected, the Spanish squadron set off. Watchmen in the flagship of Commodore Schley (USS Brooklyn), saw multiple smoke plumes rising from behind the hills and gave the alarm. Schley sent the small and fast yacht Vixen to inquire about the Spanish preparation state in case of a sortie. But despite his precautions, Schley had to acknowledge also the disappearance at dawn of the cruisers New Orleans and Newark, left coaling in Guantanamo, escorted by the battleship Massachusetts. This by the way unlocked a new massive opportunity in the West.

USS New York, Sampson’s flagship. A powerful armoured cruiser by 1890s standard.

Sampson, on USS New York, sailed from his position to “close the gap.” The latter and the Brooklyn were now the only two units that can effectively intercept Cervera’s squadron, at both ends of the pincer. At 9:35 on a glassy sea and bright sunshine, Cervera on board Infanta Maria Teresa followed the pilot guiding his way to the mouth. His ships followed at intervals of 7 minutes. Brooklyn’s watchman saw the plume of smoke moving behind the hill, closing to the entrance and gave the alarm, quickly confirmed by Schley himself. Battle flags were drawn to the apple of the masts, but Sampson on USS New York had then disappeared from view and was not informed.

The duel starts

The duel began between Maria Teresa and the battleship Iowa, across the mouth. It was almost an execution: The Spanish admiral ship, going at full speed, could only present part of her front battery and a few pieces in barbettes, while the squadron formed in a semicircle presented almost all its broadside. The whole horizon barred with black silhouettes which could explode with multiple lights -followed by detonations at any moment. Fortunately for Cervera, there was not a breath of wind, and thick white smoke partially hid her ship and he fired. He fired a second time, but missed despite the closing distance. At seven miles east of Santiago, Sampson had an interview with the General when one of his watchers signaled the white fumes of the Spanish guns. He spotted the Teresa and realized that the time had come. He ordered his his huge cruiser to turn for “crossing the T” of Cervera’s line of battle. At this distance it was still impossible however to predict if Cervera would escape east or west.

Cervera’s chivalrous diversion

Cervera also quickly studied his options and decided to practicing one of these chivalrous gestures which was the pride of the Spanish crown: Heading due west towards the Brooklyn, he would try to ram her, allowing the rest of the squadron to respond effectively to the Americans and escape to the east, apparently empty of USS New York, as none were able to follow them. As expected, the subterfuge worked and the battleship Texas, very close to the Brooklyn, believed that Cervera was to sail due west, and began his maneuver, dragging the rest of the squadron. The Brooklyn was the only one that effectively turned her prow east (by mistake, not prescience!).

Through the fog generated by the greasy smoke lingering and spreading to the surface due to lack of wind, one of the watchmen of USS Texas suddenly spotted with amazement the emerging white bow of a cruiser, adorned with the stripped coat of arms and Eagle. He shouted “Brooklyn straight ahead!” and thanks to the presence of mind of the mate who manned the bar on “full astern”, and the readiness of the helmsman, the Texas avoided a fatal collision…

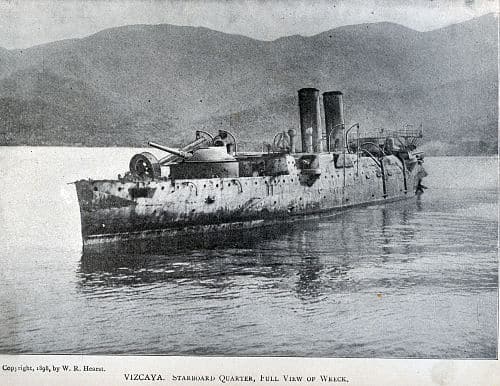

Wreck of the Vizcaya

Leaving the bay, Cervera saw the Brooklyn coming eastward with him over the side. Declining a ramming, he then confirmed his early heading west to deceive the US Fleet. Penetrating deeper into the American fire square, he drew all the shots, while Colon and Vizcaya started to escape by shaving the coast. Banking heavily, Maria Teresa was hit by a large caliber that destroyed the bridge, killing all present officers including the captain. Cervera then took personal command of the ship which began to burn, fire spreading dangerously into the corridors at the rear, next to the ammunition bunkers, which could not be drowned. Cervera decided to save his men while allowing some hope to continue the fight from the shore: He turned his ship towards the beach hoping to ran aground. The American ships still could not follow their boilers being only half of their maximum heat or even cold. These same measures ordered the night before to prevent the ships falling short of coal weighed heavily on the action.

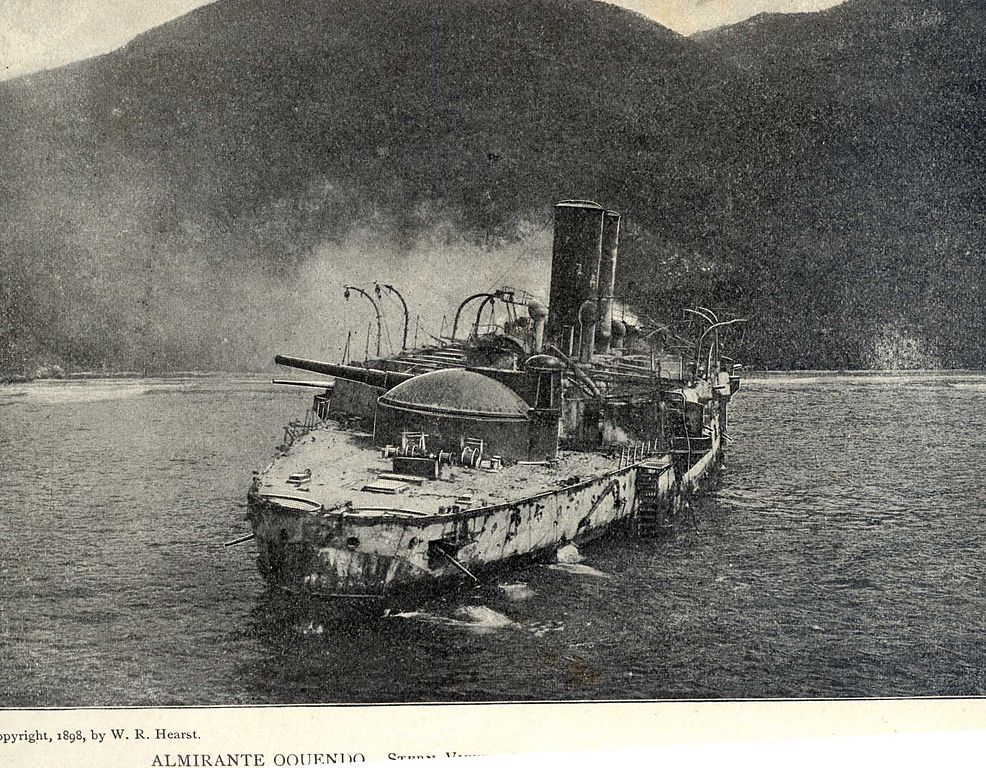

Cruiser Almirante Oquendo is next

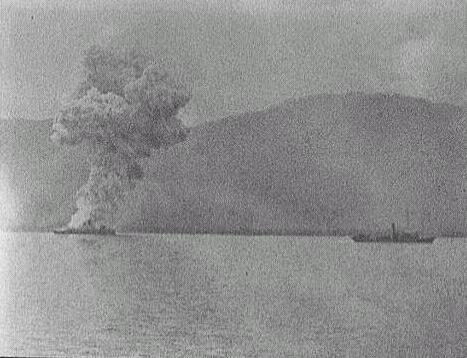

Situation of the cruiser Almirante Oquendo then changed dramatically. The cruiser, just passing the harbour’s mouth and was left alone until then. But because fire subsided on the Maria Teresa, now helpless and burning like a torch, they pointed their sights on the unfortunate cruiser. The Ocquendo fired back, but all her guns were silenced one after the other. After less than half an hour, officers were all killed as more than half of her, and she ran aground in turn, less than a mile from Teresa. But at that precise moment of impact at 10:30, her hull was so battered that she that broke in two in a tremendous explosion.

Spanish Cruiser Almirante Oquendo- Wikipedia

Spanish destroyer’s turn

Finally, the hull was achieved by fire from destroyers Furor, Terror, followed by Pluto. The first two escaped, zig-Zagging between high geysers of large calibers, but the Pluto received an impact of large caliber (330 mm) on its rear deck, destroying its engine room and distorting her rudder. Veering sharply to the coast, she almost immediately struck a reef, destroying its bow. Fortunately her crew jumped out and swam to shore in minutes. The irony of all this was these were the world’s first practical destroyers, due to Captain’s Villaamil vision, but they never went into action as planned.

Furor chased by USS Iowa. The Furor class, creation of Aug. Villaamil was arguably the first purpose-built destroyer worldwide.

Meanwhile for the Furor, situation was not better: First impact on the bridge killed officers and the bar went stuck at its highest incidence just when ordered a tight turn. Like the Bismarck years later, the unfortunate destroyer began to turn around, turning into a sitting duck. Unable to replicate with its inadequate guns, she was quickly evacuated, just before another shell 330 mm landed in the engine room, sending pieces of boilers brought to white into the blue. Water rushed immediately and the Furor sank in an instant. In thirty minutes, two cruisers and two destroyers has been destroyed. Schley could savor his victory by advance.

Vizcaya’s deperate duel

The kill board however was not yet fully completed: The USS Brooklyn, followed by Texas and Oregon were chasing the slow Vizcaya, closing along the coast. Battleship Iowa and the yacht Gloucester fished survivors, leaving Indiana behind, still heating up. A tremendous artillery duel began at close range (900 meters) between the Vizcaya, protecting Colon’s escape, and USS Brooklyn, sandwiching her as in Nelson’s finest hours. At such distance, all guns erupted, even machine guns crackled with rage. For a bit Schley and his crew felt their own finest time has come.

Regular exercises of American gunners began to bear fruit. While reloading slower because the officers asked them to take time before fine-tuning the sights, their hits multiplied to the point that a sailor was baffled not to see any white plumes misses. For their part the Spanish gunners were a little faster, and had the advantage of a thicker hull armor. But 1898 was the only fiscal year where gunnery practices were curtailed, leading to some imprecision in return fire. At one point, the Brooklyn suffered a 280 mm shell that penetrated the hull just below the bridge but did not explode, injuring two sailors superficially. A moment later another shell decapitated a gunnery lookout standing in the sight top.

But the next moment, a hit at the stern of the Vizcaya blew the torpedo tube and the ship began to burn furiously, pouring blinding smoke on the unfortunate gunners. The fate of the vessel was sealed. Slowly but surely all her guns were put out of action, so much so that after a while, there were thoughts of preparing the ship for ramming, or beaching the ship, like the other two. The commander was seriously wounded, the second took over, and after a quick “vote” with the officers and men presents to see if something more could be done for the crown and honor of Spain, it was decided to ground the cruiser onto the beach.

Vizcaya’s men ordeal

Seeing the ship heading towards the coast, the Brooklyn and Texas ceased fire. Texas’s crew was rejoicing, starting a song of victory when Captain Philips ordered them to be quiet, saying “Do not sing, boys, those poor devils are dying”… Indeed, from there they could see small red and white spots in a macabre and sobering picture of scorched and twisted corpses littering the bridges, sometimes emerging from open wounds of the hull. The Vizcaya was transformed into a floating hell, with a continuous rumbling in the background. The fire became so intense masts began to writhe under the heat. Planks of the bridge that did not burn gave way, opening the buckling mess of steel raised to red by pressure. The entire ship’s belly was just a huge boiler vomiting tortured men and parts from all its reddish orifices.

The Vizcaya explodes, hull split in two

But for the survivors ordeal was not over: Jumping to the water knowing what would be the pain of a salty water in contact with their burned flesh and open wounds, they had to remain afterwards immersed intermittently to escape gunfire from Cuban resistant firing from ashore or attending the show passively, capturing those washed ashore. They eventually decided to go after the representatives of the hated regime, swimming painfully to shore, yet inflicting them another horrible death with machetes and guns. The scene was such that Commander Evans, from USS Iowa, who had launched all his boats to pick up survivors, sent one with an officer voicing ahead to discourage Cubans to continue their killing, under the threat of a volley of his large guns.

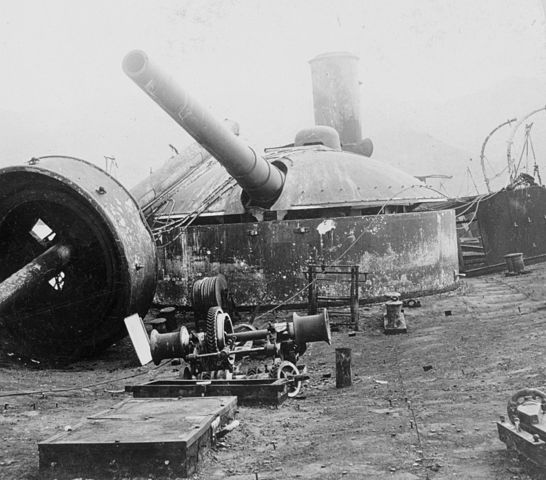

Gun on Vizcaya’s wreck

Spanish sailors seeing the massacre playing ashore began to turn back for the rescuing Americans despite their exhaustion, but had to contend with sharks, attracted and maddened by the smell of blood, barring their way back and striking at random. This horror went to the very doorsteps of the American boats: The first master of Iowa, Jeffrey Davis, recalled giving a hand to an officer, heavily burned and calling for help. As he leaned to grab his forearm, he saw a gray spinning close to the board, and next fell back into the boat, with the trunk of the unfortunate: A shark just took the rest.

Cristobal Colon’s fate

The Cristobal Colon, meanwhile, seemed to left his pursuers. She was now chased by the Brooklyn, whose machines were still not yet fully heated, the Oregon, whose crew redoubled efforts. Finally, Texas, to the rear, continued on her course. The hunt lasted for two hours, to the point the Cuban coast was about 110 Kilometers away. The Colon was making then twenty knots and distances stretched, but soon a fateful decision was made to spare coals stock and reduce consumption.

Schley was jubilant: The Spanish cruiser seemed to put more miles between his own ships and her, but he knew that soon the coast’s shape would oblige the Iberian cruiser to change course, this time closing the gap with her pursuers. On the bridge of Colon, the commander studied his options. He knew full well that in one hour his exhausted drivers, toiling in the hell of the engine room (over 50° at full steam) would have ran off Asturias coal and commence feeding the local low quality coal instead. As expected, at nine in the evening, while the coast was starting to get closer, the smoke plume still visible on the horizon from USS Oregon changed imperceptibly. Slowly but surely, they began to distinguish a shiny black bow with hints of red in the setting sun, until large main guns were ready to bear, and later close enough that the 203 mm from the Spanish ship came also within range. The final duel between the two vessels began.

Wreck of he Almirante Ocquendo

End duel

On the sixth salvo, the Spanish ship was now cornered to the coast which now barring the way. The Captain decided not to be caught: Despite honors commanded, he noticed a group of reefs in order to ran aground her ship, then scuttle her. It was done and sailors and officers quietly gained their boats and aimed to the shore, waiting to surrender to the Americans. When Admiral Sampson arrived at full speed on the USS New York, it was all over. He could only watch the wreck of the Colon marking out the side, ripped, twisted, whence torrents of thick curls. He could also see the bridge crowded with men from the USS Indiana and Iowa, a ballet of boats pulling bodies tossed like puppets on black water.

USS Oregon leaving California to join the Caribbean in 1898, nicknamed “the bulldog of the fleet” she was the fastest and most recent battleship of the US Navy.

In the whole Cervera’s squadron, only the small, but aptly named Terror had survived. The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was over. The Spanish Empire not only had lost the same day his best admiral, taken prisoner along with 1600 men and 70 officers but had to deplore 323 dead or missing and 151 injured, the loss of the best fleet, and its possessions in the Caribbean, this, a few months after the fall of the Philippines. Only a handful of the crews successfully joined the lines defending the city. The Americans had lost one officer and deplored nine minor injuries and one seriously. Santiago will fall on July 17, resisting over two weeks against much superior forces.

Wreck of the Almirante Ocquendo in 1899.

Epilogue

The battle’s lessons were numerous, although the whole affair was very much one-sided, between a cornered admiral with inadequate ships trying to escape a veritable “execution squad” of battleships and armoured cruisers blockading Santiago’s bay. It showed some difference in gunnery practices, but probably the most intriguing fact was the postwar Sampson-Schley Controversy. The whole point among naval officers was to determine which commanding officer deserved credit for the victory. When Sampson’s New York approached Schley’s Brooklyn, the latter singalled by flag “The enemy has surrendered” and “We have gained a great victory”, on which Sampson answered later with a “terse and seemed needlessly brusque” message according to naval Historian Joseph G. Dawson and tension grew between the men, but really exploded when the press decided to choose its champion, Sampson’s Fourth of July Victory, after his cable to Secretary Long. This was heavily resented by many in the fleet, moreover Schley.

On July, 5, Kentucky Congressman Albert S. Berry argued publicly that “Schley is the real hero of the incident” and that his actions deserved much of the credit for the American victory. The controversy gained momentum in the press, sides were chosen, with more credits to Schley be given on the popular opinion though a young cinema, Thomas Edison making an acclaimed film of the battle. Of course this divided the Academy and Officer corps as well, Alfred Thayer Mahan backing Sampson. When Secretary Long proposed the two officers being promoted Vice-admiral, Sampson was promoted first despite his lower rank in the promotions list which was seemed by many as “a great injustice” and the case was eventually ported to a court of inquiry which opened on September 12, 1901 at the Washington Navy Yard, with 14 charges of negligence over Schley, finding he did not “project the right image of a naval officer”. Schley did appealed to Theodore Roosevelt which called for an end to all public disputes but the affair somewhat tarnished what was otherwise a true, legitimate naval victory.

The Reina Mercedes, abandoned in Santiago Bay because of engine troubles. This unprotected cruiser was captured by the U.S. Navy and used as a receiving ship until 1957 as the USS Reina Mercedes. Two other colonial cruisers (Isla de Cuba, Isla de Luzon) were also reclassified as gunboats in US service?

Aftermath

The effects of this victory resonated less in the Spanish Congress as well as the popular press, than on elites who saw the last ships down with a final dream of matching Charles V Empire. In August, deprived of any support from the metropolis, Cuba surrendered and Spain sued for Peace in August. The war was over. Meanwhile a legend was forged on land, on San Juan hill: a stocky, highly energetic officer shouting orders to “Battler Joe” Wheeler (a celebrity of the former Confederate Army), with mustaches and little round glasses, climbed under fire at the head of his dismounted Rough Riders and entered the legend. Former Assistant Secretary of State for the Navy, avid reader of Mahan, Theodore Roosevelt was also an adept of the Monroe doctrine. He was elected 12 years later, President of the United States. A great lover of hunting and nature, he was also the driving force behind a navy that will raise in a matter of 15 years, to a level close to the Royal Navy, making it known worldwide through the acclaim “great white fleet” cruise. See US Navy in ww1.

Bios

Fernando Villaamil: A competent Spanish naval officer, designer of the first destroyer warship in history (Furor) and for the Battle of Santiago de Cuba as the highest ranking Spanish officer killed that day, of an heroic death.

Fernando Villaamil: A competent Spanish naval officer, designer of the first destroyer warship in history (Furor) and for the Battle of Santiago de Cuba as the highest ranking Spanish officer killed that day, of an heroic death.

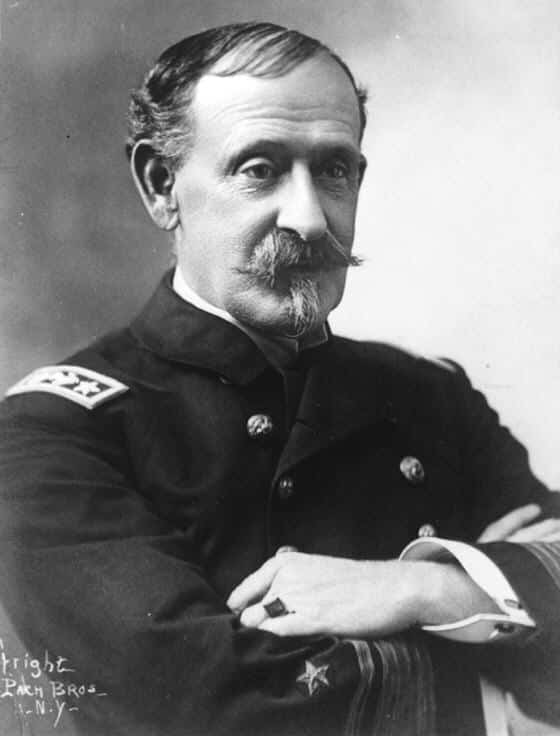

Winfield Scott Schley:

A rear admiral in the United States Navy and the hero of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, Schley was debated over Sampson about who really won the battle. He was put in command of the Flying Squadron, with U.S.S. Brooklyn (CA-3) as his flagship. His ships engaged that day probably the best cruisers of the Spanish Navy, the Teresa, the Vizcaya, and the Colon. His duel with the Vizcaya could have turned more vicious if that was not for the help of the USS Oregon. His maneuvers were later magnified by the press and perhaps gave him more credits that he actually deserved.

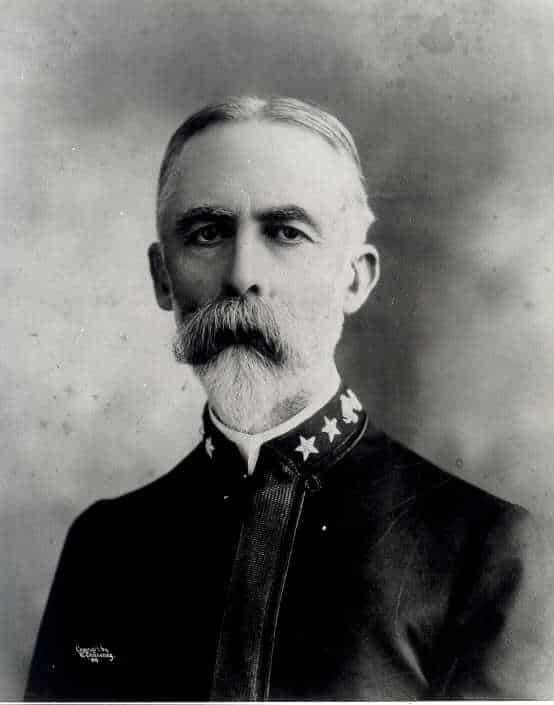

Almirante Pascual Cervera y Topete:

A highly decorated veteran of the Spanish Navy, which also distinguished himself during the Carlist Wars. Later as head of Spain’s Ministry of Navy, he attempted a number of far-reaching reforms but eventually resigned. At Cuba he led a brilliant circumnavigation of U.S. naval forces but did not had the necessary ships to face the US Navy there, his position being betrayed by the governor. Leaving Santiago to try leave the blockade ended in failure, but Cervera was upon his returned cleaned of any competence failings after the trial for the loss of his command, mostly because of the effort of his crew and was honored by the Republican Navy years after, naming a cruiser after him.

Admiral William T. Sampson

. Due to his senior position of command, Sampson was generally given full credits for his victory at Santiago. A New Yorker, pure product of the United States Naval Academy, he served in the Union Navy in 1864 with the monitor Patapsco of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. In the 1880s he was a Superintendent of the Naval Academy, and he became Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance in the 1890s. He was also appointed as commander of the battleship Iowa in 1897 and led the enquiry for the destruction of the Maine. A rear admiral in 1898 his flagship was the armoured cruiser USS New York. He undertook the Cuban blockade and bombarded San Juan before being sent to intercept Cervera’s squadron.

Videos

About the battle

This article is part of a Triptych: The war of 1898.

Links & Sources

http://www.spanamwar.com/spanishf.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Santiago_de_Cuba

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_T._Sampson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winfield_Scott_Schley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pascual_Cervera_y_Topete

Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign