Confederate Navy (1863) Single prototype, following Pioneer and American Diver 1861-63

Confederate Navy (1863) Single prototype, following Pioneer and American Diver 1861-63

So many books and documentaries, even featured films were made about this particular Confederate vessel. HL Hunley was indeed an early precursor, and although human-propelled, born from desperation, she was the first to sink a warship in operation. “the Hunley” was also a vicious and unforgiving machine, killing three crews, including its own creator. It was designed to lift the blockade and managed nit by the Navy but the Army in Mobile under general P.T. Beauregard. Rediscovered in 1970 and refloated, she broughty nw light on her demise and is now in long term preservation, with a replica displayed at Mobile’s Battleship park. #csshunley #hlhunley #submarine #confederatenavy

Genesis of the first and only Operational Confederate submarine

A pioneering story (1620-1860)

The “invention of the submarine” has many entries way going back in time, starting perhaps with Alexander (the great)’s bell, as an early diving apparatus, but to progress to a self-propelled craft, it needed sciences to really quick off in the XVI-XVIIth centuries. There was Cornelis Drebbel’s vessel of 1620, first navigable submarine and proposed to the British Royal Navy already, steerable with a leather-covered wooden frame. However, if it was already intended for military application, the admiralty was less impressed than King James I, first king to make a test dive in the Thames.

The “invention of the submarine” has many entries way going back in time, starting perhaps with Alexander (the great)’s bell, as an early diving apparatus, but to progress to a self-propelled craft, it needed sciences to really quick off in the XVI-XVIIth centuries. There was Cornelis Drebbel’s vessel of 1620, first navigable submarine and proposed to the British Royal Navy already, steerable with a leather-covered wooden frame. However, if it was already intended for military application, the admiralty was less impressed than King James I, first king to make a test dive in the Thames.

There was the 1653 72-foot-long Rotterdam Boat, an underpowered semi-submerged ram made by De Son for the Belgians against RN blockade, and Giovanni Borelli’s drawings suggested one theoretical try, in 1696 Denis Papin created two submarines (again on paper) using pressure gages to dive, in 1729 English house-carpenter Nathaniel Symons created a one-man expanding/contracting sinking boat, and by 1773 Wagonmaker J. Day, made another small submarine with detachable ballast.

The next military submarine application that went far enough was pioneered in the Americas when David Bushnell attempted to (again) combat Royal Navy’s blockade with his “Turtle” in 1776. The Revolution could have been won by a revolutionary weapon. It ultimately failed, but this was already quite a remarkable achievement for its time, far more agile and sophisticated, not a mere “riverine covered boats with oars”.

Then again in 1812, as the Royal Navy returned to their ancient colonial holdouts, now independent, and Robert Fulton proposed the same. The process was long. He was one of the foremost pioneer of steam, and after working on a steam tug in Britain he came to France in 1797 and soon proposed the “Nautilus”, for most historians “the first practical submarine”.

Then again in 1812, as the Royal Navy returned to their ancient colonial holdouts, now independent, and Robert Fulton proposed the same. The process was long. He was one of the foremost pioneer of steam, and after working on a steam tug in Britain he came to France in 1797 and soon proposed the “Nautilus”, for most historians “the first practical submarine”.

It was boat-shaped to achieve greater speed but ironically not steam but hand-crank powered. Designed between 1793 and 1797 so not long after Bushnell’s turtle, Fulton proposed it to the Revolutionary French Directory in order to subsidize its construction and allow the French Navy to retake dominance over the RN. He later proposed to be paid after sinking merchant shipping, in prize money. However French politics at the time were just chaotic, and instead he spoke directly to the Minister of Marine, who granted him permission to build his prototype at shipyard Perrier in Rouen and its sailed by July 1800 on the Seine River, then at Le Havre, making many tests and successful dives.

It was then assessed by the Minister and proposed to Napoleon, then Consul, but with no avail. He was offered funding by Britain to create a second Nautilus for them until victory at Trafalgar made it irrelevant. He also invented the “torpedo” (a mine) and in the War of 1812 Fulton’s was the guiding hand behind almost all of the torpedo attacks on the British blockading fleet…

Submarines of the civil war

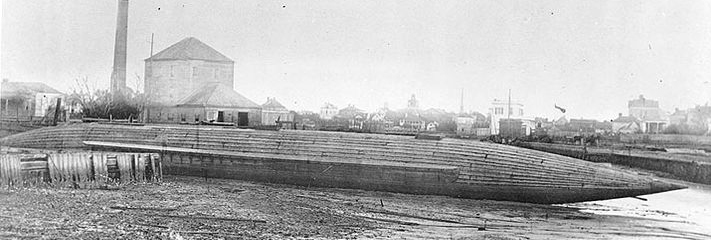

CSS David at Fredericksburg, 1865

As the world’s settled under British dominance in the latter years, the submarine was again considered, missed the Mark in Crimea but found a resurgence during the American civil war. Yet again, a blockade and asymmetric warfare motivated its birth. There were several civil war “submarines”, all human-powered, like the 1850 Brandtaucher (to break the Danish Navy blockade of Kiel) and in 1852 the sea devil for Russia, 1859 Ictineo I (Spanish Narcís Monturiol). In 1863 the French unveiled the first sub powered by its own source, compressed air, but it meant a short range. She was an harbour defence vessel with a mere 5 nautical miles (9 km) range and confederate industry was in no shape to build such model anyway.

However before that the Confederates unveiled two interesting vessels: The CSS David, a semi-submerged steam powered spare torpedo vessel, whereas the CSS Pioneer was developed by Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson as a first practical all-metal military submarine. The HL Hunley was built with already this experience, and the Union went interested in the end to destroy notably confederate barrages on rivers, and notably studied a prototype by French engineer Brutus De Villeroy (developed from 1859 to explore British warship De Braak lost near the mouth of the Delaware River in 1780), leading much later to the USS Alligator in 1862.

Precursor: CSS Pioneer

Well before a team assembled to create the first practical all metal confederate subs, Indiana shoemaker Lodner D. Phillips went to try in at least two submarines, one in 1845 which collapsed under 20 feet and second which reached four knots under 100 feet, offered to the U.S. Navy which declined, and again during the Civil War. In the south, the Confederate government authorized citizens to operate armed warships as “privateers”, but did not precised the type. In New Orleans, a consortium headed by cotton broker H.L. Hunley led to approval for a very unusual vessel, the “Pioneer” 34-foot long and needle-cigar-shaped, but also metal built to sustain pressure. It was designed and built by James McClintock.

This was the result of a team of three visionaries, Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson, albeit Hunley is mostly remembered, he was merely funding it but also assembled the team and went on creating the Pioneer, Pioneer II, and Hunley.

Taking inspiration from previous designs, it was a simple, small craft with a crew of three, one steering, two cranking the propeller. Conceived by Horace Lawson Hunley with engineering assistance, it was unique in 1861 as a way to break the union blockade. Designed at Mobile by John Mc. Clintock it was made of steel, but submerged only at a few feets, made to close its target and deliver a “torpedo” (mine triggered by a pistol-cable or clockwork mechanism, eventually adopted as less risky).

30 feet long, 4 feet in diameter (9 meters x 1,20 meters) it was rather cramped internally, with a pilot and at the start a single man to turn the propeller manually. Tests in February 1862 in the Mississippi River showed it was underpowered and a modified crank for two men installed. In March 1862 there was demonstration on Lake Pontchartrain, and after a few sorties, Pioneer sank a schooner barge with a towed floating torpedo while submerged, proving to all witness the soundness of its concept; It never became operational however.

Replica on display at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center. There is also another at the Maritime Museum Louisiana in Madisonville.

The Union advance towards New Orleans in April 1862 however, and capture had its builders scuttling Pioneer on New Basin Canal on 25 April 1862 for it not to fall in Union’s hands. but it was spotted, raised and examined by Union troops anyway. It was then examined and sketched by Ensign David Stauffer of USS Alexandria. Postwar, Times-Picayune of New Orleans reported by 15 February 1868 it had been sold for scrap. It should be noted that the unidentified “Bayou St. John submarine” (Louisiana State Museum) was for decades reported as CSS Pioneer. They indeed started trials at about the same time but very little is available. Perhaps rediscovered letters would bring some light on this other early confederate submarine.

Mobile: CSS Pioneer II

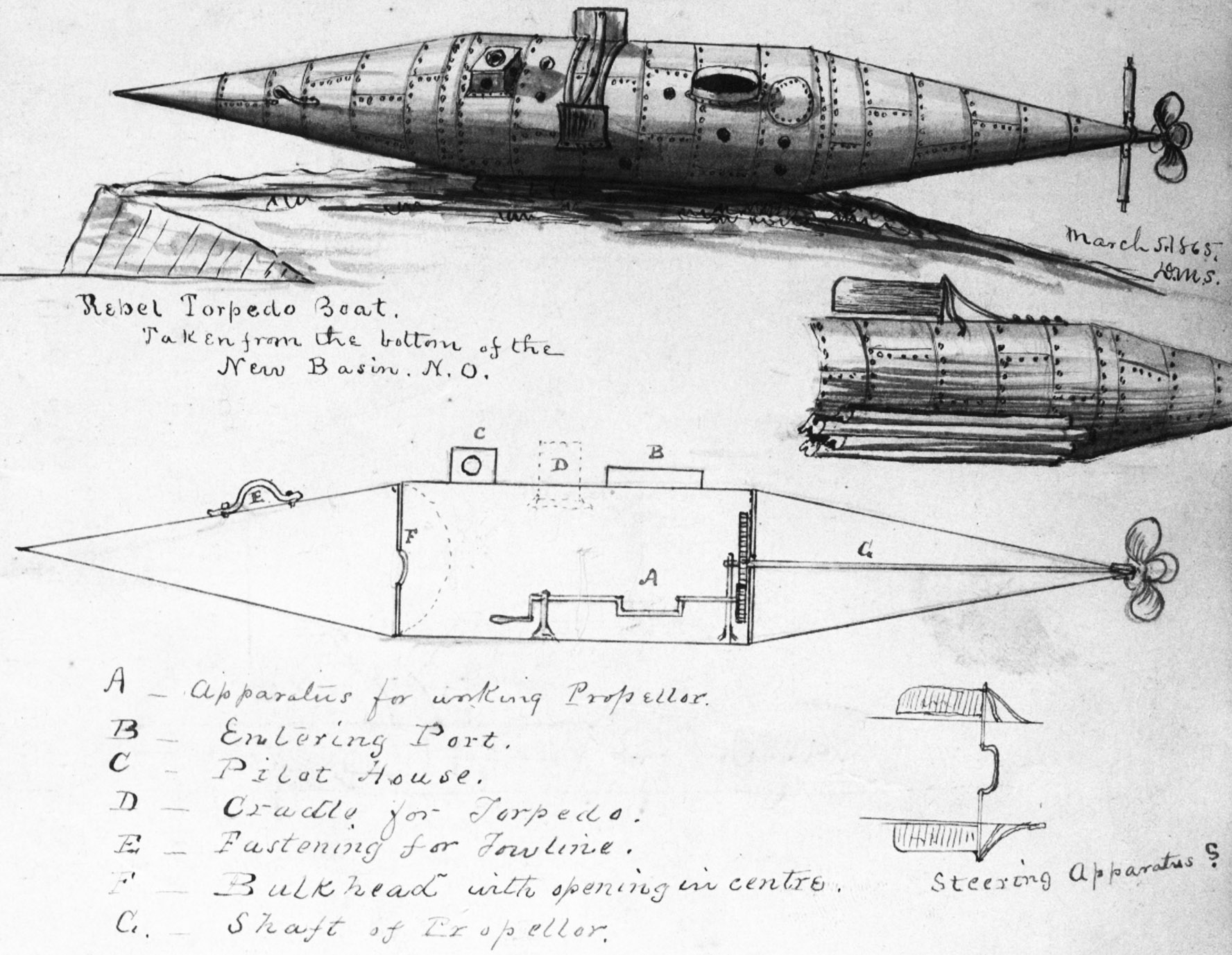

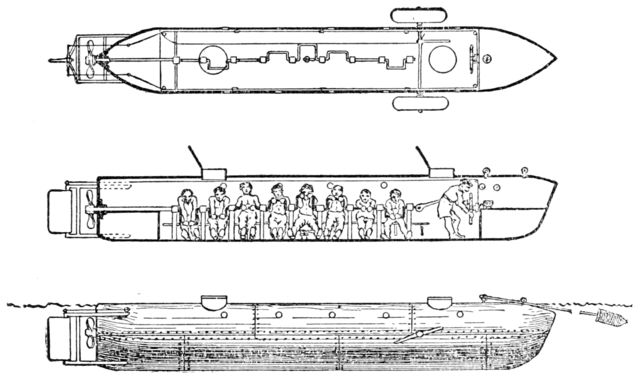

Cross-section of the American Diver. From a sketch drawn by Jame R. McClintock in 1872.

Anyway, the important fact is the experience gained. The team relocated to built the Pioneer II (“American Diver”) in Mobile, Alabama. This new prototype submarine was designed and built by late 1862 but the teal wanted to replace human power and it led to months of unfruitful and costly attempts to have it equipped either with an electrical motor and later steam engine, leading to man failures. The most avant-guard was the electric-magnetic engine teste, unable to produce enough power to propel the submarine and, no documentation exists on how they tested the motor, so we may never know how close they came to succeeding. Technology was just not there yet. Next was tested a small custom built steam engine, building up pressure within its boiler while running surfaced, then the fire was shut and funnel capped before submerging, runing on remaining pressure, but it failed too, perhaps due to the scarcity of materials in wartime Mobile compared to New Oerleans.

The Admiralty which followed the project grew impatient and convinced the team to just fall back to the trusted hand-crak system to have it operational as soon as possible.

The hull was no longer cigar-needle shaped and more practical, more boat-like, at least for its profile, with a constant height from prow to stern, both straight but still flanks and tail sloped downwards aft. It was more prismatic with fine entries, and had two small observation cupolas fore and aft, solid ballast fore and aft. It was 36 ft (11 m) in lenght and 3 ft (0.91 m) in beam. It was steered by two long diving planes on either beam.

Trials started by January 1863 and the longer hull meant four crew members were now turning the propeller crank. This shown the Pioneer II was way too slow. McClintock, reported “She is unable to get a speed sufficient to make the boat of service against the vessels blockading the port.”

Still, by February 1863, she was towed down the bay to Fort Morgan and sent to attack the Union blockade off Mobile anyway. She foundered in heavy chop caused as the weather degraded fast, and currents at the mouth of Mobile Bay conspired against it. Fortunately, she sank slowly enough for the crew to escape. As of now, she is buried in sands, in an unlocated position, and an ongoing expedition was launched after interest was raised with the discovery of the HL Hunley. So far she was never rediscovered.

Design of HF Hunley

Undeterred, the team started work again, trying to improve the concept again, this time stretching the basic hull in order to accomodate more hand-cranking men. By that time the context for the Confederacy somewhat degraded on land, but also at sea, with a coastline still completely controlled by the Union, preventing imports from Europe and Coastal America. The south lacked clothes, food, artillery, medicine, and even reinforcements when needed. Submersibles were thus an even increasingly important asset to defeat the Union blockade. Thus Horace Lawson Hunley financed Designer James McClintock to improve the American Diver in Mobile, at first called even the “pioneer III”.

The South had spies in the Union and thus learned about the submarine USS Alligator unviled late 1861, so the Confederacy needed one urgently. The team in Mobile well understood the need to recoup spendings on this development, via financial gains coming from sinking enemy ships, and during tests with Pioneer I, McClintock noted that the next iteration would need to move freely in any direction and at any depth, but also needed more power and worked on the American Diver. Park & Lyons machine shops (Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons) woukd built and the Confederacy staff sent Lieutenant William Alexander of the 21st Alabama Infantry Regiment to oversee the project.

The self-propulsion type proposed by McClintock’s, an electromagnetic drive, proved way too complex and underpowered, and next the custom steam engine failed to produced enough output. Back to the simple hand-cranked propulsion system it appeared after harbor trials by January 1863 already too slow and it was “spent” in an attempted attack in the bay to Fort Morgan and attempt until foundered. Meanwhile the team worked on an improved design, which goal was essenetially to provide more raw power, meaning, more men on the crank. This meant also elongating the hull while keeping the same general design, roomier and more rationale than the previous torpedo-like Pioneer.

Hull and layout

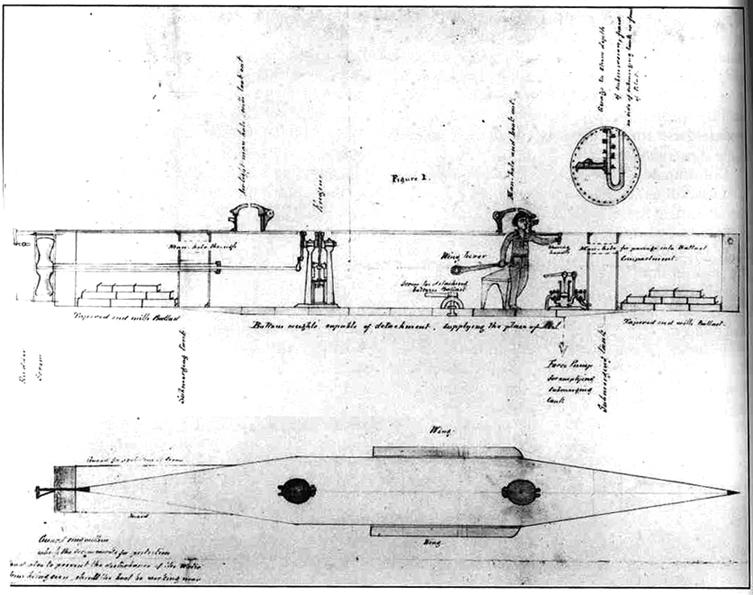

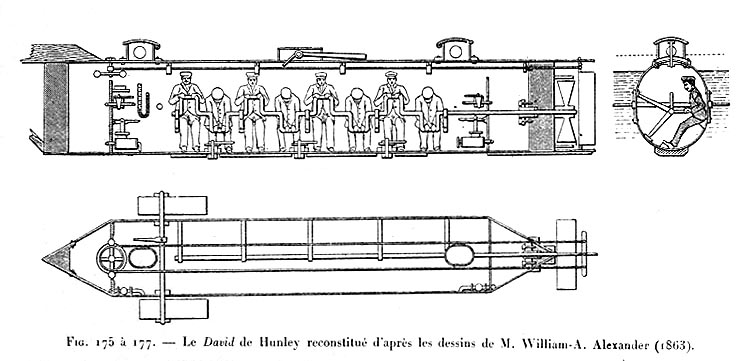

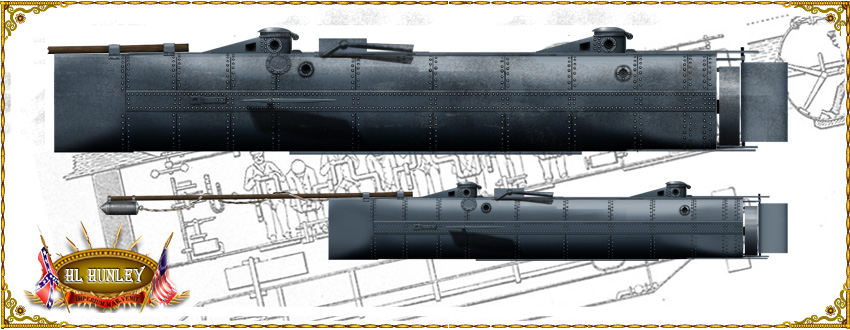

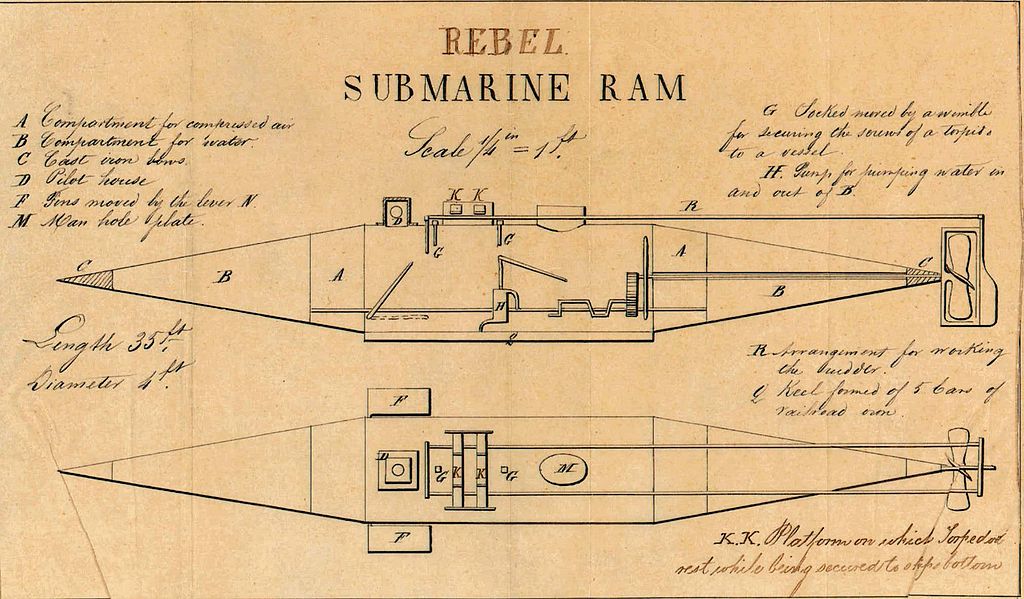

Inboard profile and plan drawings, after sketches by W.A. Alexander (1863)

The “fish boat” or “fish torpedo boat”, or “porpoise” as known in letters and documentation of the time was designed and built as a much imporved American plunger, stretched, and sleek, as rendered in R.G. Skerrett’s 1902 drawing. There were two ballast tanks flooded by valves but pumped dry by hand pumps. Extra ballast consisted in iron weights bolted underside. For an emergency rise, they could be quickly dropped by unscrewing the heads of the bolts from inside, however it was never tested.

The hull length was never noted in documentation, at least surviving, but was at first estimated 39.5 feet or 12 meters, quite an increase compared to the Pioneer II, for a beam estimated at 4 feet 3 inches (1.30) in diameter at first, then after she was recuperated in 2017, confirmed at 3.83 ft (1.17 m).

There were two hatches also acting as conning towers like for the older design, placed forward and aft, with enough space for a single operator so see through the thick glass bricks all around. Each hatch was quite small, about 16.5 inches (420 mm) in width, 21 inches (530 mm) in length and the impression did not ended there. The boat was extremely cramped and well below human size inside, so everybody had to move carefully and stay seated at all times. Up to a crew of eight could fit inside, seven around a single crank shaft and turning a ducted propeller for an outout estimated at just 3.5 horsepower (2.6 kW). One man could stand aft to steer the submersible using the rudder handle. During trials, the yet unnammed (at least officially) submersible managed to reach 4 knots (7.4 kph or 4.6 mph). Meaning that if there was a distance of a mere 10 nautical miles to the target, 18 km, so around 2h40 to reach the target, and at night to avoid being spotted. So the crew needed a lot of stamina.

Armament

The question remained open although the base system agreed upon from the start was a spar topredo. It was never well studied before as previous submersibles were proven underpowered and never reach the armament stage as concepts. Hunley was initially to carry a floating explosive charge with contact fuse (“torpedo”) and that obliged the submersible to dive beneath the keel of the target, then manage to attach the charge on hull, then re-emerging ou of blast range. This was later cancelled due to the risk of becoming entangled in the rope or it drifting away from the ship, or even the chargenot attaching or detached in time form the submersible. There were too many hazard for it to succeed.

The spar torpedo then was adopted as a far more secured and simpler experient. It consisted in a spar, attached forward of the submarine and detachable, carrying at its tip, a copper cylinder containing 135 pounds (61 kilograms) of black powde. The spar in wood made 22-foot (6.7 m) long and ideal usage depht was 6 ft (1.8 m) underwater.

Reaching the hull with the tip of the spar was not a problem, so a simple contacter to ignite the charge was the simplest way, however the carrier submersible would be only 22 feet away from the blast, so way too close to survive it. Lowering the charge would make it impotent against a ship (sinking it was the goal, not just scratching the paint) and having even a twice as longer spar would made it unwieldy while not still procuring enough distance.

One solution was a barbed point to have it attached onto the hull’s side, while retreating at a safe place, but there was no easy way to trigger the charge. A clock activated underwater being out of the question, a fuse being also too uncertain to setup if anything happened, detonation by a direct mechanical trigger attached to the submarine ws the best solution.

Drawings of H. L. Hunley from 1900.

This was done by securing a line along the spar, going from the charge to the submersibles, with enough distance to be safe when backing away from her target. Unlike trying to go underneath the ship, in that case, the cable wuld simply reach its maximal distance and rupture, setting off the charge via a pistol mechanism inside the charge. But it was never reconsitututed and foggy in its realization.

In 2017 and following years, Archaeologists discovered new evidence: A spool of copper wire and battery components. They deduced that it was to be electrically detonated, quite a revelation. It seems that system was retained when attacking USS Housatonic. In that case, there were no barbs, the charge was to explode on contact if pushed against a ship at close range, but after Horace Hunley’s death ‘thus naming the submarine), General Beauregard ordered a new delivery system. There was to be an iron pipe attached to the bow, angled downwards to have the explosive chargemoved deeper underwater for effectiveness, same method as on CSS David, which worked wonders against USS New Ironsides. It seems the system was designed by Battery Marshall’s engineer with a colleague, adjusting the iron pipe mechanism for Hunley, just before the fatal attack on 17 February 1864.

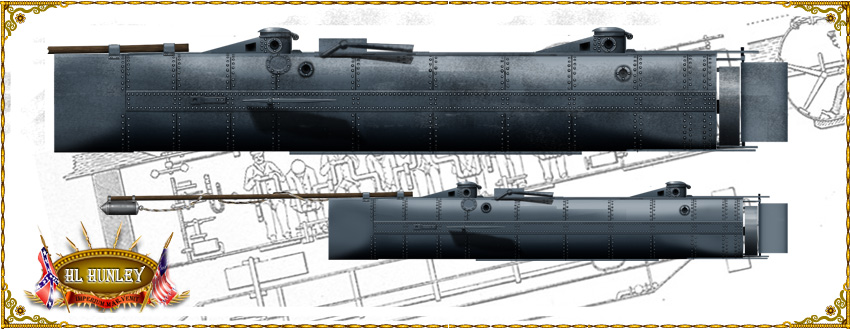

Author’s illustration of the CSS HL Hunley

Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | Length 39.5 ft (12 m) x 3.83 ft (1.17 m) |

| Displacement | 7.5 short tons (6.8 t) |

| Crew | 2 officer, 6 enlisted |

| Propulsion | Hand-cranked ducted propeller |

| Speed | 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) (surface) |

| Range | Depending on speed and stamina, 20 nm max |

| Armament | 1 spar torpedo |

Career: A deadly trap ?

By July 1863, “fish boat” was ready for a demonstration under supervision by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan. After several trials without spar, one was installed for an attack of a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay (which failed) but she was shipped by rail nevertheless to Charleston, South Carolina on 12 August 1863. Upon arrival, the Confederate military seized the submarine to turn it over to the Confederate Army and served under its command, never gaining thus the “CSS” label. However Horace Hunley and partners remained involved in later testing and operation.

By July 1863, “fish boat” was ready for a demonstration under supervision by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan. After several trials without spar, one was installed for an attack of a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay (which failed) but she was shipped by rail nevertheless to Charleston, South Carolina on 12 August 1863. Upon arrival, the Confederate military seized the submarine to turn it over to the Confederate Army and served under its command, never gaining thus the “CSS” label. However Horace Hunley and partners remained involved in later testing and operation.

CSS Chicora and Palmetto State in Charleston

First and second losses

First captain of the fish boat became Confederate Navy Lieutenant John A. Payne detached from CSS Chicora, which volunteered as well as seven men from Chicora and Palmetto State, both river ironclads, so these were already picked up men. On 29 August 1863, there was a first test dive. Lieutenant Payne however accidentally stepped on the lever turning the diving planes as she was running surfaced, and since the forward hatch was still open, water gushed in as the started to dive deep. Despite the pressure, the closest to the hatch managed to sally out and survive, but the five man trapped close to the shaft never had thi chance (Michael Canen, Nicholas Davis, Frank Doyle, John Kelly, Absolum Williams).

Payne reported the incident and was dimissed by General P. G. T. Beauregard which directly took copmand of the programm, replacing him with protégé Lt. George E. Dixon. The submarine was refloated, cleaned, and prepare for a new dive, Dixon managing to find without issue a new volunteer crew, despite the risks. He made a few more test dives, but by 15 October 1863, Dixon was replaced by HL Hunley himself, which wanted to oversee the training. When he failed to surface after a mock attack, the submarine just ran out of air and the whole crew suffocated, including Hunley himself, just there for the exercise. In addition to Hunley (which gave his name to the boat as a tribute) the corpses of Thomas S. Parks, Henry Beard, R. Brookbanks, John Marshall, Charles McHugh, Joseph Patterson, and Charles L. Sprague were retired from the submarine after being recovered a second time.

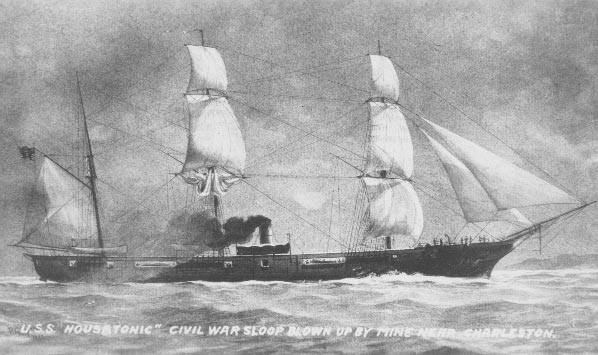

The attack on Housatonic

By that point the new Confederate “secret weapon” seemed cursed. Nevertheless, Dixon retook command and manage to find despite all odds, another volunteer crew. There were probably one or two test dives without incident, before HL Hunley was prepared and towed to her operating area. This was to be her first and only attack, planned for the night of 17 February 1864. The site and meterololgy seems to favour the attack and the target was the 1,240-long-ton wooden hulled Sloop USS Housatonic, steam-powered (screw) armed with 12 large cannons, wooden hulled. Located at the entrance to Charleston, 5 miles (8.0 kilometres) offshore, her battery thwarted any exit. Detailes of Dixon’s attack are uncertain and open to interperation, but the Confederacy rejoiced at the sinking of Housatonic at that time. The explosion, at 20:45 could be seen from Charleston as most of the population wouls still be awake at the time.

Dixon indeed, probably after a long, gruelling approach, manage to get close enough and ram the hull with its only spar torpedo, detonated. The wooden hulled, uncompartimented, was flooded and sank in three minutes but only five men trapped inside did not survived. However news of this success changed the following day to sadness as Hunley and her crew were reported missing and were never seen again, with the exact circumstances and location lost to history (until 2017).

Battery Marshall commander reported he received the agreed upon signals from the submarine but it seems he saw something else. A postwar correspondent of the Union reported also, after a testimony of one lookout on Housatonic a “blue light” on the water after the ship started sinking, related to the color of the pyrotechnic signal of the U.S. Navy and not the sub’s “blue lantern”. The US signal is what was probably reported 4-mile (6 km) away at Battery Marshall. If still alive at the time, as planned, Dixon would have return to Sullivan’s Island as found in some sources, another stated she was unintentionally rammed by USS Canandaigua, which remains unsubstantiated.

Rediscovery and preservation

It was to need the rediscovery of the submarine to shed light on what happened. In 2017, this is what happened and led to the “find of the century” for some.

H. L. Hunley, suspended from a crane during her recovery from off of Charleston Harbor, August 8, 2000

This was claimed by Underwater archaeologist E. Lee Spence (president of Sea Research Society) in 1970, however the case was dismissed as the wreck was outside the jurisdiction of U.S. Marshals Office. By 13 September 1976, the National Park Service submitted nevertheless the location for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, approved by 29 December 1978. Spence would later write “Treasures of the Confederate Coast” (published January 1995)

But the discovery was also claimed that same year by Diver Ralph Wilbanks. He found the wreck by April 1995 and it was found 100 yd (91 m) away from from the Housatonic’s wreck site, under 27 feet (8.2 m) of water, buried deep under silt, concealing but also protecting it fpr more than 100 years. The divers managed to retire and expose the forward hatch and ventilator box. As later examined, she layed resting on her starboard side at c45° under a thick rust encrustation and seashell particles. Digging, the divers uncovered her bow dive plane and after some time fixed her apparent lenght to 37 feet. On 14 September 1995 E. Lee Spence donated Hunley to the State of South Carolina but the site was only made public in October 2000, after all precaution had been made.

Investigation and excavation culminated with the raising of Hunley on 8 August 2000 and a team from the Naval Historical Center’s Underwater Archaeology Branch of National Park Service working with perosnal from the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology documenting her wreck before final removal from the seabed. She was raised by harnesses slipped underneath, lifted by a crane made and operated by Oceaneering International, then deposed on the recovery barge Karlissa B on 8 August 2000, 08:37, greeted by a cheering crowd and shipped back to Charleston.

She was preserved for treatment in the Warren Lasch Conservation Center (former Charleston Navy Yard). A specially made tank of fresh water hosted her for conservation later replaced by sodium hydroxide. This was all told at the time in the TV documentary of the Sea Hunters serie, “Hunley: First Kill”. Soon after HL Hunley entered pop culture through many books and the 1999 TV movie “The Hunley“.

The whole story was tarnished however by a lawsuite by Clive Cussler in 2002 against E. Lee Spence, and countered by Spence’s own. It was dismissed in 2007 under the Lanham Act and Cussler dropped his suit a year later upon producing clear discovery evidence.

From there, Hunley is opened to tours at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in Charleston with a more accessible replica on display at the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, together with USS Alabama (BB-60) and USS Drum (SS-228).

This discovery and careful investigation led to revise the circumestances of her loss. It all pointed to the instantaneous death of crew when the torpedo made contact with the hull of Housatonic. No crewmembers, still found seated at their stations showed signs of skeletal trauma and the boat’s pump to remove water was nit activated, suggesting they died before HL Hunley was flooded. Also keel blocks were not unbolted. By January 2013, conservator Paul Mardikian find’s indicated the torpedo had been attached directly to the spar instead of a remote system, which explains that at a mere 16 feet (5 m) from detonation point, the concussion probably is what killed instantly the crew. This was confirmed by a later reconstitution by blast trauma specialists from Duke University, published by August 2017 in PLoS One, although this is still debated today.

Src/read more

Books

Keegan, John (2009). The American Civil War: A Military History. Random House.

“American Diver: A New Diver of Destruction”. Friends of the Hunley. September 17, 2011.

John S. Sledge (29 May 2015). The Mobile River. University of South Carolina Press.

“The Birth of Undersea Warfare – H.L. Hunley”. Undersea Warfare. Official Magazine of the U.S. Submarine Force. 2011.

Protasio, John (10 June 2021). “Evolution of the Submarine”. warfarehistorynetwork.com.

Bonnette, Roy. “Technology and Practice in a Historical Context: Building the Civil War Submarine Pioneer”.

Kelln, Albert (1953). “Confederate Submarines”. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Virginia Historical Society.

Protasio, John (10 June 2021). “Evolution of the Submarine”. Military Heritage.

Links

connecticuthistory.org

pbs.org/ nova/lostsub

usnlp.org/

warfarehistorynetwork.com

http://www.navy.mil/n

gilderlehrman.org/

web.archive.org/ hunley.org

The Mobile River, John S. Sledge

American_Diver

Pioneer

wiki H._L._Hunley

3D

Video

Model Kits

Confederate Submarine CSS H.L. Hunle 1/35 35-013 Brand: Micro-Mir

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign