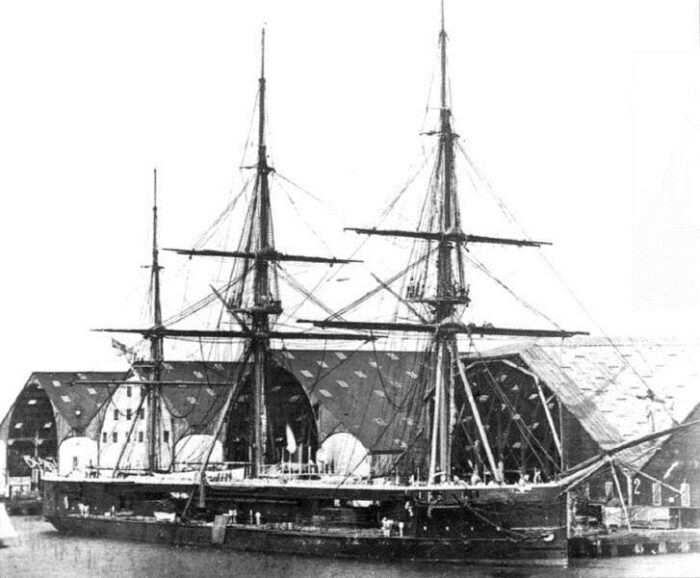

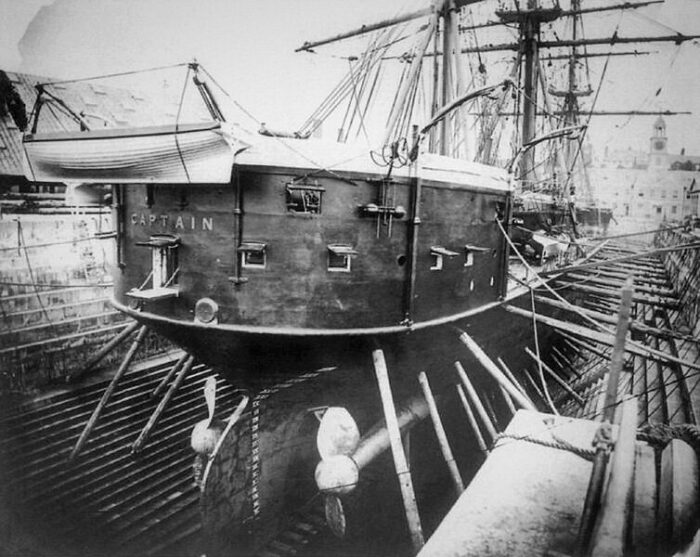

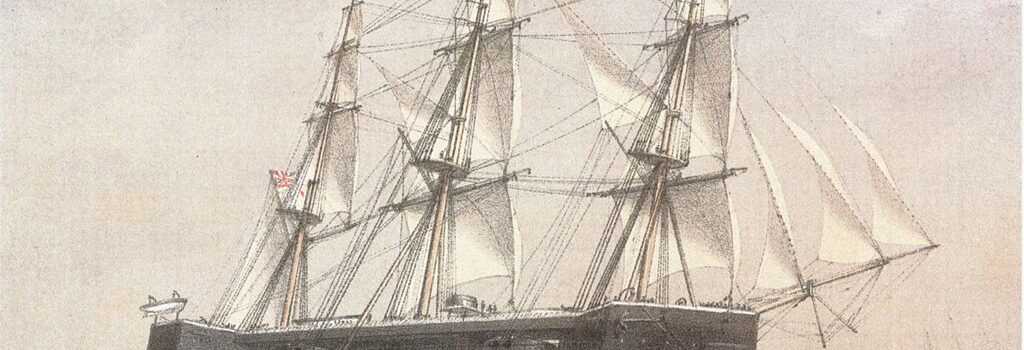

RN oddballs, second entry, HMS Captain. She was probably one of the most infamous ironclads of her era. She was essentially a prototype of new masted turret ironclad, authorized as a semi-private venture despite objections of the admiralty. Coles, inventor of the turrets, thought to create a “prefect battleship” and worked with Laird NyD to design a low freeboard vessel with hurricane deck and tripod masts, plus of course two massive turrets housing two 12-inch MLR each. Objections were raised by the DNC, E.J. Reed over these plans in 1866, but construction proceeded anyway, and she passed her sea and gunnery trials, but famously capsized and sank on 6 September 1870 off Cape Finisterre (Spain) during manoeuvres in a storm, going down with 472 lives. This was high profile tragedy and a court-martial later established her stability was at fault. This came after a heated design debate in 1866 between Coles and the admiralty. HMS Captain became the poster child of stability calculations gone wrong. But did Coles was alone to blame ? The truth was of course more complicated… Her wreck since 2021 had been the subject of explorations and a project to raise her is being financed.

Development

About Cowper Philip Coles

The son of a reverend and a navy cadet in 1846, C.P. Coles in 1853 was already a flag Lieutenant on HMS Agamemnon and later took part in the Crimean war. He was thus no stranger to naval matters, and distinguished himself at the siege of Sevastopol, propoted in November 1854 to commander and in August 1856, Commanding officer of HMS Stromboli in the black sea. During the siege of Taganrog he had the idea of a raft mounting a heavy gun to go into shallow water and proceeding to close shelling.

The son of a reverend and a navy cadet in 1846, C.P. Coles in 1853 was already a flag Lieutenant on HMS Agamemnon and later took part in the Crimean war. He was thus no stranger to naval matters, and distinguished himself at the siege of Sevastopol, propoted in November 1854 to commander and in August 1856, Commanding officer of HMS Stromboli in the black sea. During the siege of Taganrog he had the idea of a raft mounting a heavy gun to go into shallow water and proceeding to close shelling.

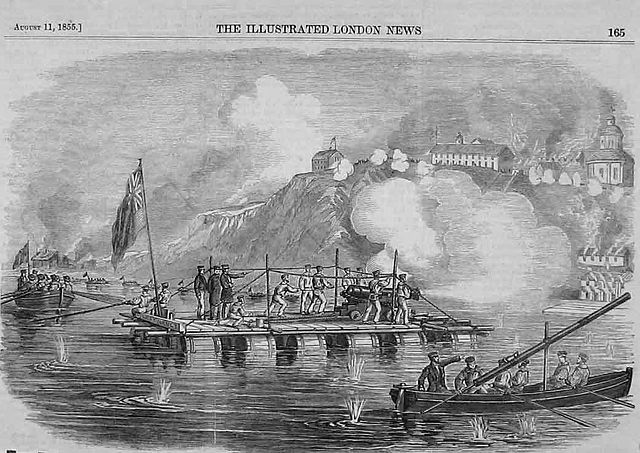

This 45ft raft was named “Lady Nancy”, and closed down to fire a 32 pounder MRL at close range on the fortifications with great effect. But at that range, the exposed crew was subjected to rifle fire and shrapnel. This made however Coles a war hero via the press at the time, noted back in London. A celebrity he exploited to “sell” another idea to the admiralty, a purpose built shallow draught vessels armed with a single heavy gun under a rotating cupola. The war was still raging in Crimea at the time. The plans he proposed were for a 90 x 30 ft (27.4 x 9.1 m) raft with a draught of 3 feet 7 inches (1.09 m) designed to close on the Kronstadt forts, but the war ended in between.

Alas, now a Captain placed in half-pay he started to concentrate on the concept of turreted ships. On 10 March 1859 he patented a revolving turret. The concept was claimed to be old by John Ericsson (which designed USS Monitor in 1861) and it’s possible the idea was suggested to Coles by Marc Isambard Brunel, a bi-national engineer and father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, one of the most famous British engineers ever.

Successive British turret ships

Before Captain was laid down in 1867, after the turret concept had been validated by combat in 1862 at Hampton Road, she was to be the ultimate prototype for a turreted ironclad, spearheaded by the untiring engineer Cowper Philip Coles, inventor in 1855 of the rotating turret. After lady Nancy, then Trusty, Coles convinced the admiralty, which warmed up to the idea enough and ordered the recently completed HMS Royal Sovereign to be converted.

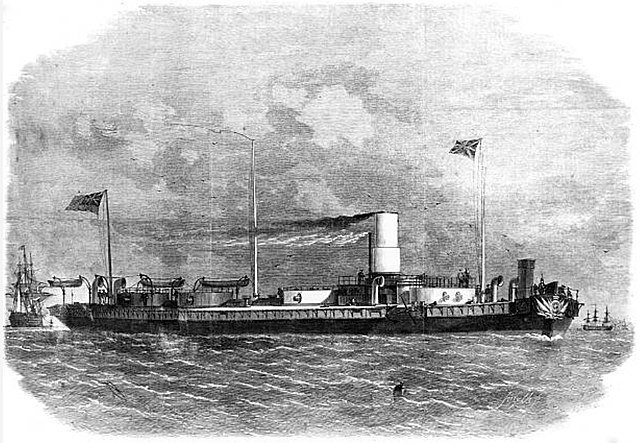

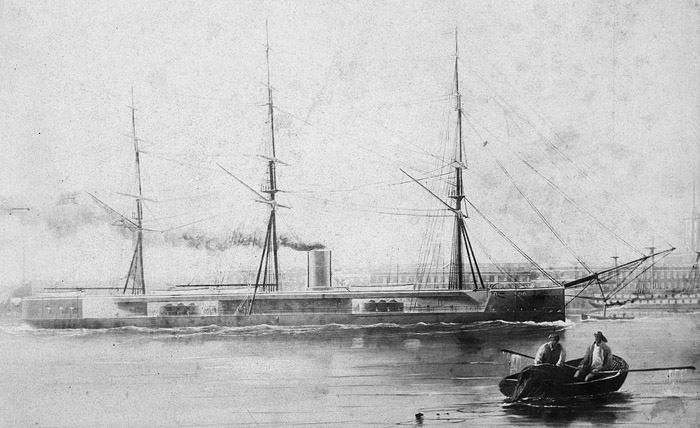

Initially the ship chosen was not the most obvious choice: She was one of the latest RN 121-gun first-rate ship of the line when laid down in 1849. As planned, she was armed with sixteen 8 in (200 mm) cannons at the lowest deck, 114 32-pounder (15 kg) guns on the two upper decks and open deck, and and a 68-pounder (31 kg) pivot gun. But the apperance of steam and screw propulsion changed plans and she was to be reconverted on the stocks to a 131-gun screw ship, starting on 25 January 1855. She was finally launched on 25 April 1857 and placed in “ordinary” straight away, so without crew or assignation planned. She had two engines rated for 780 nhp. But after years of inactivity she was selected for conversion into an experimental turret ship, a steam-only vessel championed by Captain Cowper Coles, quite a radical conversion as seen below:

Initially the ship chosen was not the most obvious choice: She was one of the latest RN 121-gun first-rate ship of the line when laid down in 1849. As planned, she was armed with sixteen 8 in (200 mm) cannons at the lowest deck, 114 32-pounder (15 kg) guns on the two upper decks and open deck, and and a 68-pounder (31 kg) pivot gun. But the apperance of steam and screw propulsion changed plans and she was to be reconverted on the stocks to a 131-gun screw ship, starting on 25 January 1855. She was finally launched on 25 April 1857 and placed in “ordinary” straight away, so without crew or assignation planned. She had two engines rated for 780 nhp. But after years of inactivity she was selected for conversion into an experimental turret ship, a steam-only vessel championed by Captain Cowper Coles, quite a radical conversion as seen below:

The conversion, which started on 4 April 1862 saw the hull being razed all the way down to the lower deck, bulwarks installed for sea keeping and the hip used as a coast-defence ship, a bit like the USS Monitor, with a 7 and 8 feet (2.1 and 2.4 m) of freeboard. The decks were much strenghtened to support the plmanned arlmament, and the sides had to be rebuilt so the conversion ended on 20 August 1864. She became the first British turret-armed ship but still with a wooden hull. She was to carry eight turrets at first, but this was changed for four ones, a 164 long tons (167 t) twin turret, hree 150 long tons (150 t) single turrets armed with 10+1⁄2-inch (270 mm) smoothbores and later 9-inch (230 mm) muzzle-loading rifles. She was fired upon to test the strenght of her turrets and this proved the copcept, however the hull, whatever low, was armoured with a 5+1⁄2 in (140 mm) belt midships, tapered down to 4+1⁄2 in (110 mm) fore and aft. She also had a CT.

She remained from her commission in 1866 in the English channel pais odd already later that year, saw the 1876 naval review, but was attached to the gunnery school until replaced by Glatton and sent to the reserve, sold in 1885. At least she proved the point.

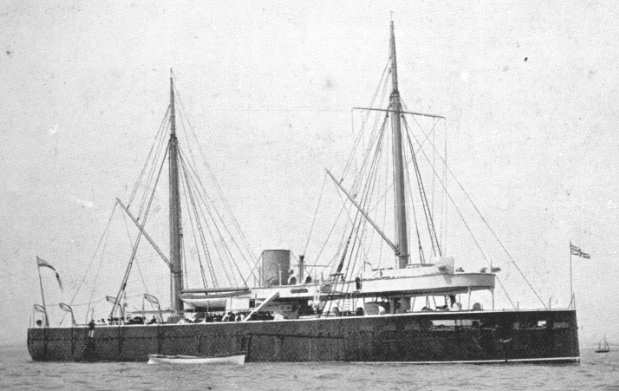

Later Coles reached a new step, by the order of a dedicated 4-turreted, shallow-draught coast-defence ship, HMS Prince Albert. HMS Prince Albert was however not the most successful design, still. She was armed with four turrets on the centerline, armed with a 9-in (229 mm) MRL gun turrets, but they were rotated by hand and required 12 men to turn these turret through 360° in a minute. Plus the low freeboard to keep stability without poop or forecastle meant poor seaworthiness, sending her to the reserve at Devonport, and in 1878 in the Particular Service Squadron. After the 1887 jubilee and 1889 manoeuvers she ended at the Dockyard reserve in 1898, BU a year later.

Coles and Admiraly’s controversy

Coles proved his point

After HMS Prince Albert and Royal Sovereign, Coles proved his point that turrets could be considered as apotent concept alternative to broadsides, resistant to enemy fire, provided special measures should be taken to preserve seawothiness and stability. Royal Sovereign was a razee which had a very low freeboard, while Prince Albert already was closer to a proper seaworthy vessel. However in the 1860s the admiralty still wanted masted vessels as an extra safety and for long crossings, as well as a more decent seaworthiness.

Both previous ships were flush deck with a jury rig and condemned to coastal service and the admiralty express to Coles the need to port his turret concept on properly oceangoing vessels to protect the empire. Engine technology indeed at the time was not trusted and sufficient enough to power his steam-only vessels to battle speed. They were lumbering designs limited to their massive coal consumption. There was no way around having a sailing rig. Of course the issue with a full rigging, was to complicate deck management and impede the turrets’ arcs of fire.

So by early 1863 the Admiralty approached Nathaniel Barnaby, the head of staff of the Department of Naval Construction to work with Coles on a properly rigged vessel with two turrets. In June 1863 however, the design phase was suspended as the Admiralty wanted to see her first Coles conversion, Royal Sovereign, on trials, to judge the path forward. This was not the first time Coles would be infuriated about such decisions.

They were successful enough for Coles to resume work in 1864 on a rigged vessel, but he designed in parallel a smaller design with a single turret, based on the design of HMS Pallas, a wooden-hulled ironclad designed as a private venture by Sir Edward Reed. To proceed forward Coles was attached Joseph Scullard, Chief Draughtsman of Portsmouth Dockyard.

The admiralty’s own design

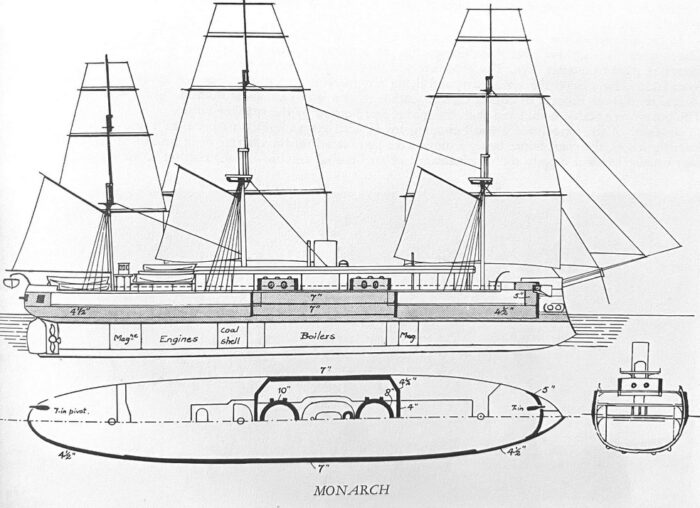

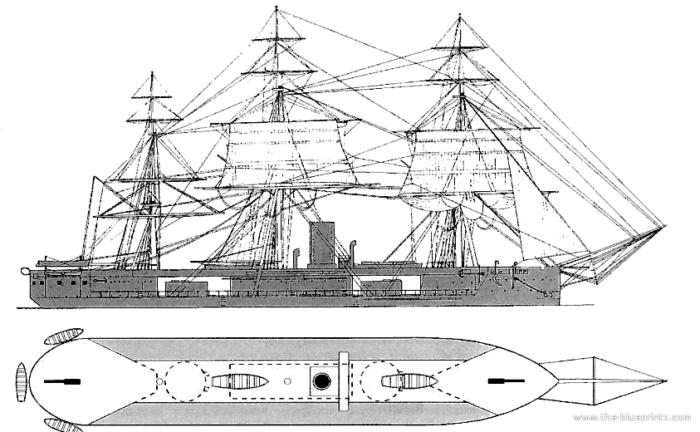

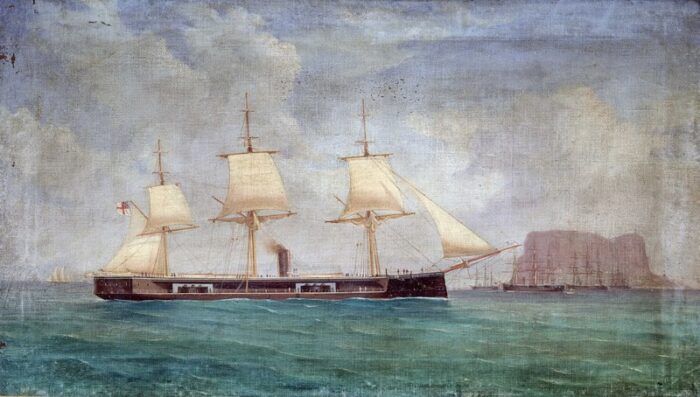

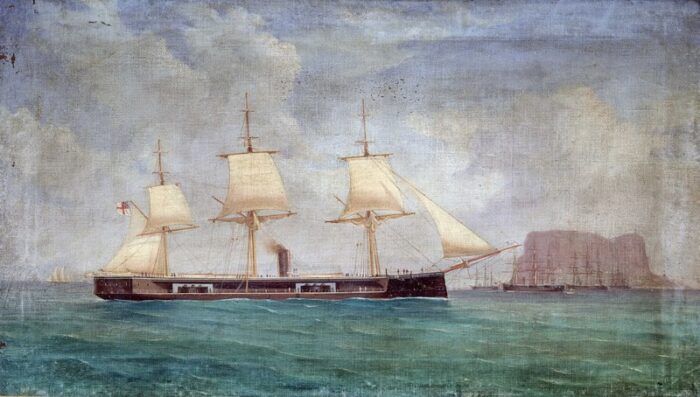

HMS Monarch, completed earlier and showing a completely different approach.

In 1865, the Admiralty established a committee to study the single turret Coles design and concluded it had inadequate fire arcs, and proposed a two-turret design which would use either two 9-inch (12 ton) guns per turret, or a single 12-inch (22 ton) gun per turret, the largest ever designed at the time. The committee’s proposal was accepted by the Admiralty. Construction of HMS Monarch was thus approved. She would have the two 12-inch (25-ton) guns design. Admiral Sir Frederick Grey, the First Naval Lord on 21 April 1866, however, suggesting the Admiralty to let Coles designing his own alternative seagoing turret-ship.

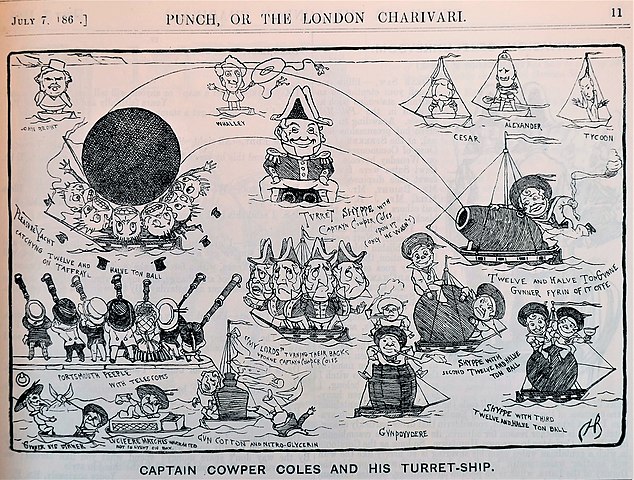

In the meantime, Coles was not pleased to see the commission scrapping his project and even his second design of a two-turret vessel, and deignrated the Monarch’s design, launching a strong campaign and even going so far as attacking Vice Admiral Robert Spencer Robinson in the press, which at the time, was the Controller of the Navy. He also attacked various members of the committee and the Admiralty itself. This encountered some echoes in politicians but obviously did not ended well for his relations with the admiralty which decided in January 1866 to terminate his consultant contract with them.

The controversy

However thanks to internal supports she was re-employed from 1 March 1866 but continued to lobby the press and Parliament, convincing them that the US was creating a massive monitor fleet, including sea going ones that could sail to any point of the globe and threat the British Empire, such as USS Dictator.

He convinced many in Britain that the rush for armoured turreted ships abroard would leave Britain at a disadvantage at sea despite it’s numerous seagoing ironclads already. On 17 April 1866, Coles submitted to the Admiralty his critique of HMS Monarch, yet to be built. Her criticizes many decision made by the designed by the Controller’s department and Chief Constructor and stated he would publicly condemned a ship he saw as making a travesty of his ideas.

This design… completely ignore my views of a sea going Turret-ship, nor can she give my principle a satisfactory and conclusive trial.

Given the heated nature of this debate, always rising exchanges and acrimonious, high-profile argument, flaring up at the commons and at the Lords would only rise, the First Naval Lord, Admiral Sir Frederick Grey, published a minute on 21 April 1866 to express that Coles should at last be allowed to build his “perfect” seagoing turret-ship. This was felt by all in the admiralty a bit ironic in tone, and was accepted. Coles would be made responsible for his own design and this would end a growing press campaign, that started to be a bit too vocal and sensationalist in its rethoric against the admiralty’s apparent resistance to change. Many in the admiralty, which could not stand Coles any more (making a common point with Ericsson on the other side of the pond) were just too happy to see both Monarch and Cole’s own design compete.

Design of the class

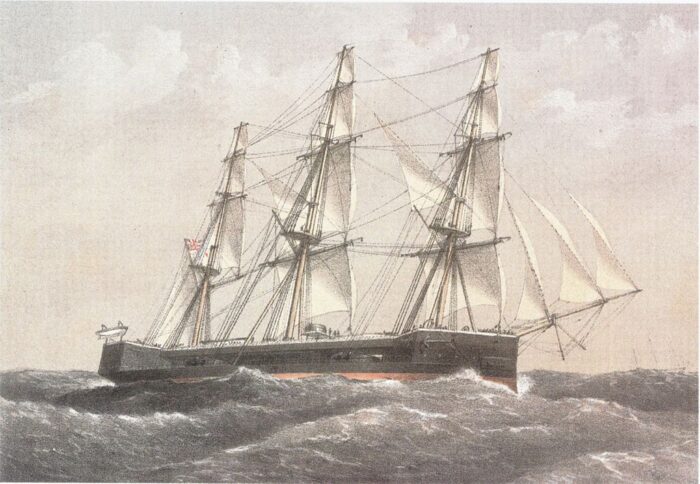

On 8 May 1866, Coles, now greenlighted, informed the Admiralty he selected Laird Brothers’ Cheshire yard as builder, since it was already experienced, having built several successful ironclads. In mid-July, Lairds submitted two designs based on his twin turreted ship draft. The rigging was still a central point in this design, and to avoid damage when the turrets were firing, the rigging was simply relocated entirely on a platform mounted above the gun turrets. This was the unique feature of this design, known as the “hurricane deck”. The usual practice was to have everything base-rigged on the main deck. Tripod masts were also used to minimise in the same idea, standing rigging, replacing extra bracing. It should be noted that the Monarch design, sperheaded by the admiralty was also objected by Reed and a compromise in many aspects.

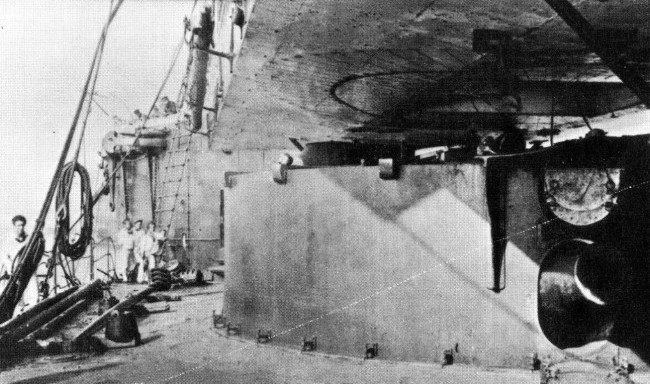

The design called a low freeboard, a trademark of Coles’ designs, and unlike on HMS Monarch. He estimated this freeboard to be raised a but to 8 feet (2.4 m). When known, the Controller and Chief Constructor Edward James Reed (working on Monarch) raised serious concerns on stability straight away. Robinson, the controller, made known a freeboard that low would invite flooding issues on the gun deck. If the force and pressure of seawater was enough in rough weather, hatches could be broken.

Reed on his part estimated Coles and Laird design to be just too top heavy with an unusually high centre of gravity and nothed that it was true especially with the proposed full rig, noting that in case of heavy weather and rain, these canvas surfaced would had many extra tons to the top weight.

Coles brushed aside these critics and proceeded as planned. However as the design neared completion in July the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir John Pakington, wrote on the 23th to Coles, approving and funding the building, but precised this time officially that the responsibility for failure would lie on Coles and the builder alone.

In November, contract was approved, with a completed detailed design and the yard started to purchase the necessary materials. She new ship was laid down 30 January 1867 at Birkenhead, 7 months after Monarch (June 1866). Captain was launched on 27 March 1869 (almost a year after Monarch in June 1868) and completed in March 1870, a year after Monarch. The latter, notably due to her higher freeboard was heavier at 8,322 long tons (8,456 t) versus 6,960 long tons (7,070 t) for Captain as designed. But Captain ended significantly heavier than expected, further aggravating her stability issues.

Hull and general design

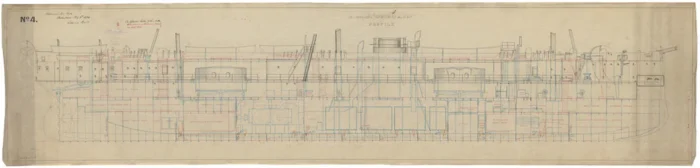

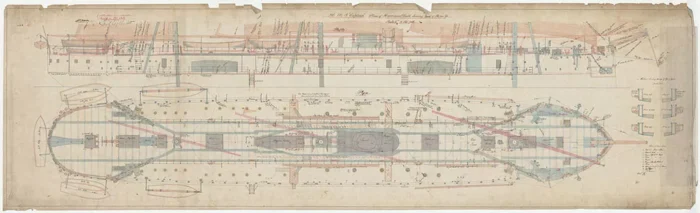

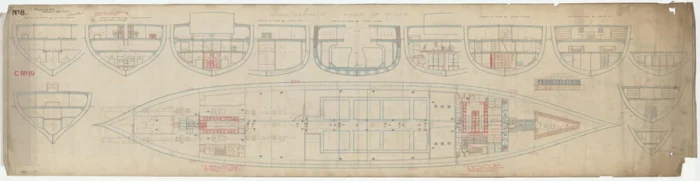

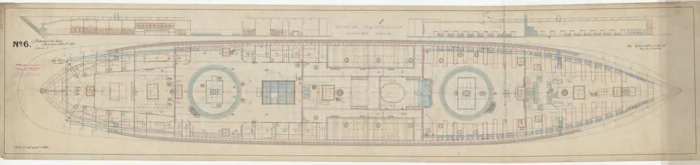

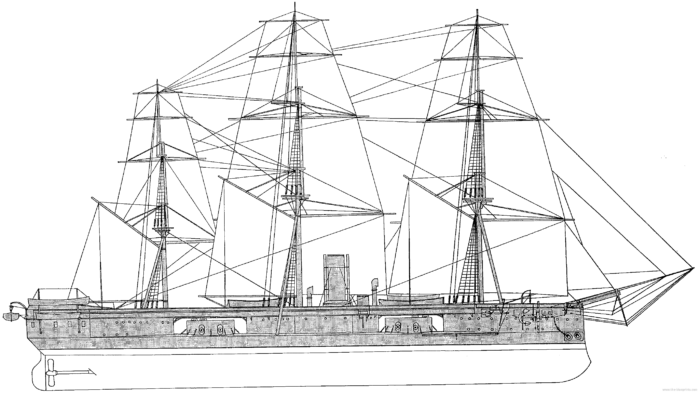

Plans of Laird Bros, Royal Greenwich Coll. src

Perhaps tired after his fight to see his ship built, Coles was rarely on site to supervised the construction, frequently reported ill. Laird completed thus a ship that was no less than 735 long tons (747 t) heavier than planned and thus, negated the planned freeboard already down to 8 feet (2.4 m). This additional weight forced her indeed to float 22 inches (0.56 m) deeper than expected and she ended with a freeboard of just 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m), 14 feet (4.3 m) for Monarch. Her centre of gravity rose by ten inches as well. Reed intervened when informed on the progress, and raised the alarm again, convinced the ship was a disaster in waiting. However of his objections were taken in considerations, Captain performed her trials with success and showed her motions “not worrysome” at the time, helped by the sea state, at the great relief of Coles and Laird.

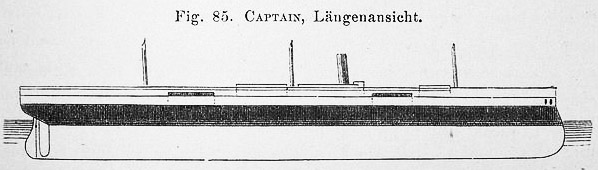

HMS Captain ended as a 7,767 long tons (7,892 t) ship, with forecastle, poop and central island connected on top by the hurricane deck. Still, her battery deck was quite low indeed and measures were taken to minimize points of access under the deck. For her rigging and turrets she had a base crew of around 500, and four boats installed on steps over the upper deck forward and aft of the single funnel plus four boats in double davits aft on the stern plus the captain’s own yawl under davit at the poop axis. there were two anchors resting on a prow cutout.

The intermediate deck, between the battery and hurricane deck was higher than usual and yet not high enough to justify two internal decks. In fact it was a ‘half deck’ with the upper deck hald-way to the level of the battery deck given the location of portholes.

Her hull had a pointy forecastle and ram bow, with a flat section amidship and rounded stern. To clear the arcs of fire, the superstructure was well angled inwards and the one at the funnel level was narrow.

Obviously the turrets were only good for broadside and traverse fire to a limited degree to blast damage and arrestors were included in the turret ring to not reach a certain degree close to the structure. The question of the weather/battery deck being flooded was solved partly by the adoption of a moderate “turtledeck” raised in its axis and sloping down in a gentle slope port and starboard. Waves were belived to flush through one side to the other without staying.

The design of the tripod masts, a first, was peculiar: The foremast’s legs were installed forward, resting on the forecastle, while the mainmast had its left angled aft, resting on the lower deck. The smaller aft mast had its leg also aft on deck and even angled at a steeper angle.

Powerplant

HMS Captain was certainly less innovative in this aspect. She had a two shaft arrangement with 2-bladed propeller screws driven by reciprocating 4 cylinder horizontal trunk engines, fed in turn by eight rectangular boilers for a total of 5,400 ihp (4,000 kW).

Her Sail planwas standard for a masteed ironclad of the time, with a total of 37,990 sq ft (3,529 m2) of sail at best, for a top speed of 15.25 knots (28.24 km/h; 17.55 mph) on steam power alone. Probably around 12 knots at best under sails. The hull had no subdvivisions but counter keels. The drive shafts were anchored by upper and lower struts. The rudder was tall and rounded but did not have a large surface. The clipper poop gave her particular hull lines favourable to speed, whic was estimated good on trials. To compare Monarch had a more conversative single shaft Humphreys & Tennant return connecting rod engine for 7842 hp and 14.94 knots on trials. She was faster under sails at 13 kts.

Protection

If the low freeboard could be seen as an advantage as reducing the target surface, the high structure above was still less protected and an issue. Plus the original design belt ended much lower than expected.

Her main Belt was 8 inches (200 mm) amidships and then tapered down to 4 inches (100 mm) at both ends.

The turrets had walls 9 to 10 in (230–250 mm), thicker forward, thinner back.

There was not armoured deck but a conning tower forward of the funnel, 7 inches (180 mm) thick.

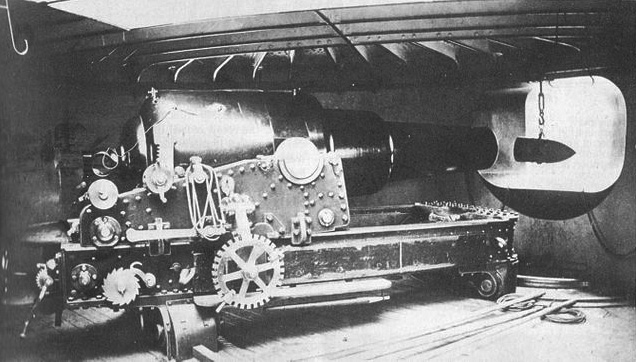

Armament

This was revised and eventually settled on two massive 12-inch 25-ton muzzle-loading rifles (MLR) completed by two single 7-inch 6.5-ton muzzle-loading rifles in the upper hull aft.

12 tons Elswick MLR

23 to 25-ton, 600 to 608.4 pounds (272.2 to 276.0 kg) as Palliser, firing a 497 pounds (225.4 kg) Common & Shrapnel shell of exact caliber 304.8 mm at a muzzle velocity of 1,300 feet per second (400 m/s).

7-inches MLR

These guns were the first to incorporate the new “Woolwich” rifling system, modified from the French system, of from 3–9 broad shallow grooves. First designed in 1865 for the 7 & 6½ ton Mark I-IV it was 126 inches (3,200 mm) long 178 mm caliber, firing a 112 to 115 pounds (51 to 52 kg) Palliser, Common, Shrapnel and 160 pounds (73 kg) double common shell at 1,561 feet per second (476 m/s) and max 5500 yards.

These guns were the first to incorporate the new “Woolwich” rifling system, modified from the French system, of from 3–9 broad shallow grooves. First designed in 1865 for the 7 & 6½ ton Mark I-IV it was 126 inches (3,200 mm) long 178 mm caliber, firing a 112 to 115 pounds (51 to 52 kg) Palliser, Common, Shrapnel and 160 pounds (73 kg) double common shell at 1,561 feet per second (476 m/s) and max 5500 yards.

author’s color profile (in prep)

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 6,960 long tons (7,070 t), 7,767 long tons (7,892 t) |

| Dimensions | 320 ft x 53 ft 3 in x 24 ft 10 in (97.54 x 16.23 x 7.57 m) |

| Propulsion | 2-shaft, rec. 4 cyl. HT engine, 8 rec. boilers 5,400 ihp (4,000 kW) |

| Speed | 15.25 knots (28.24 km/h; 17.55 mph) |

| Range | |

| Armament | 2×2 12-in 25-ton MLR, 2× 7-in 6.5-ton MLR |

| Protection | 4–8 in (100–200 mm), turrets 9–10 in (230–250 mm), 7 in (180 mm) |

| Crew | 500 |

HMS Captain’s Tragedy

Comparative trials: Captain vs Monarch

HMS Captain was commissioned on 30 April 1870. Her first and last CO was Captain Hugh Talbot Burgoyne, VC. She had her sea trials in May and that summer, and Burgoyne only had praised on the way the ship behaved. It seemed everything that Coles had promised. In fact the press, which years before participated in a heated debate went to assist to the trials and even more eager when it was announced she wold have trials versus the Admiralty’s design, HMS Monarch. In these summer comparative trials she performed quite well, even doing far better in agility and being ahead in speed.

HMS Captain was commissioned on 30 April 1870. Her first and last CO was Captain Hugh Talbot Burgoyne, VC. She had her sea trials in May and that summer, and Burgoyne only had praised on the way the ship behaved. It seemed everything that Coles had promised. In fact the press, which years before participated in a heated debate went to assist to the trials and even more eager when it was announced she wold have trials versus the Admiralty’s design, HMS Monarch. In these summer comparative trials she performed quite well, even doing far better in agility and being ahead in speed.

After some fixes, she was again at sea in August, for a shakedown cruise, sailing all the way to Vigo in Spain, and then pushing to Gibraltar in two runs. On the topic of agility in 1870, there was an interesting printed note from Vice Admiral Sir Robert Spencer Robinson, Controller of the Royal Navy and acerb critic of Captain, to the Board of Admiralty on 31 May 1870. For him in the comparative trials of May 1870 he believed Monarch was superior to Captain except when was disconected her single screw which interfered with the helm “in a given position” so this made her “perfectly unmanageable.”

In late August 1870 both her and Monarch returned at sea to compare their accuracy and rate of fire for brand new heavy turret ships with equally heavy guns. They were notably compared to the then new centre-battery ships. Their target was a 600 feet (180 m) long and 60 feet (18 m) high rock, off Vigo, often used by the RN as target practice due to its ideal size and position. Both vessels had to fire underway at 4–5 knots (4.6–5.8 mph; 7.4–9.3 km/h) and they fired for five minutes with text-book, but not rushed loading. Both had the same caliber guns and fired Palliser shells with battering charges, 1,000 yards (0.91 km) away from their target.

Captain had three hits on target at her first salvo, but the recoil made her roll heavily at ±20° while smoke made aiming difficult. The 20° were a worrysome prospect as calculations and trials showed her “non-retuen point” was above 21°. An inclining test at Portsmouth back on 29 July 1870 suggested indeed that her extreme heel could be on a calm sea up to 15°-16°. From there, calculations on 23 August 1870 she may not survived heeling above 21°. It was already predicted by Lairds in January-February 1870. So the yard knew her limitations.

HMS Monarch and the Hercules, also present during the firing test did better with their first salvo but were blinded by smoke. Their roll was however much lower, and remained safe. Hercules showed her gunsights on the guns rather on the turret roof worked better.

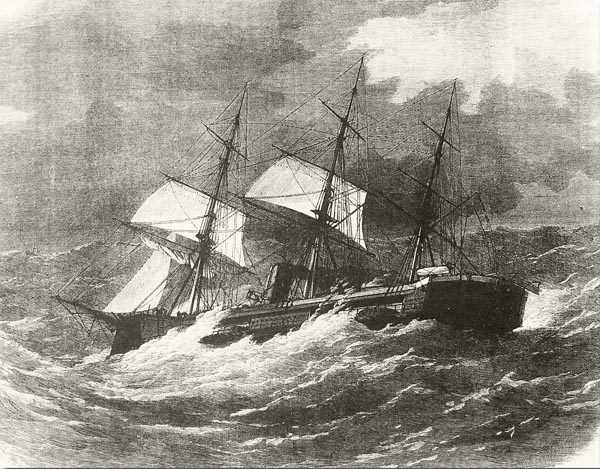

The night of doom

On 6 September 1870, Captain was part of a massive battle fleet combining the Mediterranean and Channel Squadrons (11 capital ships) off Cape Finisterre. Captain was underway at 9.5 knots under sail, as her CO judged safe to raise rigging to capitalize on force 6 winds, making also a rigging trial at high seas, still missing in her record. However the winds only got stronger later that day. CiC Admiral Sir Alexander Milne previous had been rowed on board HMS Captain to assist to her performance under sails. She even managed at some point to reach 11–13 knots at his enjoyment, just before he departed. But before this, he expressed concerned on how her low freeboard deck was constantly washed over by waves.

Burgoyne however ordered to reduce sail not only after the demonstratio but later as the weather worsened, with rain squalls and the obscurity falling. The wind was blowing from the port bow so to avoid being tossed around he ordered to steer her angled to the wind, and speed further was reduced. Still all soon observed as she was pushed sideways as if her angle and steering could not nothing. Then as night fell, the wind morphed into a gale. Burgoyne thus order all the sail to be reduced to just the fore staysail, fore and main topsails. The ship indeed had a 4-stage rigging on each mast.

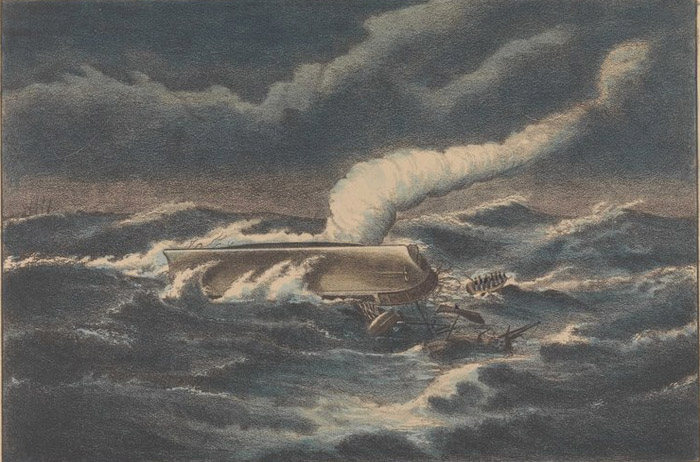

Shortly after midnight, there was a change of watch, most of the crew was fast asleep. The watch officers immediately noted and reported that HMS Captain was heeling over 18 degrees under the wind, and even rolled further starboard twice. The light projectors of nearby ships could still be seen reporting Force 9 to 11 (Beaufort scale: 60 knots) wings and 50-foot (15 m) waves. The officer in charge reported this to the captain, which ordered to reduce the fore topsail, release ropes holding both topsails angled into the wind to negate any wind trap.

But even before this last order could be carried out, her roll increased above 21° and as predicted, she capsized. The two turrets left their enormous ring, and water rushed inside the hull, so she sank rapidly, carrying with her 472 lives, and that included Captain Coles, also onboard. Sons of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Hugh Childers, and Under-Secretary of State for War, Thomas Baring, were also on board and went down, leaving only the 18 men on deck this night alive. They managed to reach a boat which had broken free and sailed to the nearest ship to be rescued and start to tell their nightmare.

Court-martial

The sinking came as a shock the following morning to the combined fleet, notably for the man in charge of the combined exercises, Sir Alexander Milne. He just could not believe it at first, but reminded the scene of waves crashing on Captain’s deck at a time winds were moderate. Back in London, this cause the headlines of all newspapers to print on their frontpage in big characters what was now a national tragedy. As the days passed by, it was decided to raise an investigation into her loss, in the form of a court-martial chaired by Admiral Sir James Hope. There was none to traduce into this court as all senior officers and protagnotists were now lying trapped at the bottom of the Bay of Biscaye. Still, senior engineers of Laird yard and the 18 survivors were auditioned as well as Sir Milne. The matter was of crucial importaance notably to rule out the solutions and shortcuts taken in Captain’s design as new ships were in construction.

The court of enquiry took place on HMS Duke of Wellington, then anchored in Portsmouth Harbour. The court-martial had its auditions day after day, and at first concluded that

“The Captain was built in deference to public opinion expressed in Parliament and through other channels, and in opposition to views and opinions of the Controller and his Department”.

This was in a sense a revenge of the admiralty for a year and more of constant complains and campaign from the British public, asking Coles ship being built to restore confidence in the primacy of the Royal Navy. Coles addition of a full-rig, even under initial request by the admiralty, seemed a curcial misstep as well as trying to reach with this design the same capabilities of a true seagoing vessel like HMS Monarch. The low-freeboard but mastless US monitors being taken in example. USS Miantonomoh for example showed she could cross the Atlantic as she did in June 1866. At the time, the Union wanted to restore finances and a way to achieve this was by selling its numerous and now surplus warships, to foreign navies. Coles and the Board of Admiralty toured Miantonomoh when she entered Spithead and were impressed by the design. But why Coles chosed that combination of low freeboard and full rigging remained to be explained as the man was no longer there to defend himself. Pundits of Laird NyD rejected part of the blame on design choices to Coles, even adding they warned him on the ship being top heavy and prone to excessive roll. Officials warnings from the DNC and others were also shown on signed documents and dated notes.

The court martial did not condemned the yard or anyone present, even Milne, which could have been more vocal about safety measures to be taken on Captain when he toured her. The Admiralty then appointed a new committee to consider all ship designs, past and present instead to to seek scientific advice. Eminent engineers such as William Thomson and William John Macquorn Rankine were still present however. Their own conclusion was that a ship such HMS Captain was insufficiently stable as even at 14 degrees heel, the edge of her deck was already at sea level. Her righting moment depended of her buoyancy and the motion, pushing her upright again was in her case up to 410-foot-tons (1.2 MN·m).

To compare, HMS Monarch had a righting moment of 6,500-foot-tons (20 MN·m) at the same angle. Captain’s maximum righting moment occured at a heel of 21 degrees but it was 40 degrees on Monarch. Survivors also testified she floated upside down for up to ten minutes, confirming she capsized indeed. It was also damning that her inclining test in Portsmouth were performed before she departed on 29 July 1870 and was still not yet published when she made her final voyage. It was thus concluded that if she had delayed this voyage (perhaps under opposition from Coles and others), that crucial, life-saving data could have been made known. Knowing the sea conditions encountered at the Bay of Biscaye specially by late summer when waves were at their highest, it was clear that Captain’s trip should have been forcibly cancelled and measures taken back in drydock to correct these defaults. Instead this was proven by 500 lives.

Another fact was before the new ironclad was received from her contractors, the fact her draught of water was increased of two feet (60 cm) and freeboard further reduced, stability compromised, and original sailing rig unchanged, should have raised further caution. The ill-stricken Coles then was probably more eager to prove his point rather than the humiliation (and cost) of his belove ship to return for extensive modifications in drydock as should have been done.

The Court Martial noted this, as well as none of these facts, known by Coles at the time, were not communicated to CO Burgoyne at the time before she departed. It is not known how much the yard and Coles ommitted these facts, but instead pushed forward to have sea trials in calms seas instead, which revealed nothing of her fatal issues. A memorial to the crew was erected in St Paul’s Cathedral in Westminster Abbey (London) as well as in St Anne’s church in Portsmouth.

A search for her wreck was initiated in 2021 Dr. Howard Fuller, Reader in War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton (“Captain project”) to locate her wreck. He made a book and held conferences on what was for hime the “worst disaster suffered by the Royal Navy in peacetime”. With the help of a Galician-based documentary company, four wrecks were discovered by multibeam echosounder-scan on 30 August 2022 with the 4th matching the configuration and dimensions of HMS Captain. Fuller and Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles (great-grandson) started a fund raising campaign, about 50% complete by June 2023. A story to follow, for a future, undoubtely mediatic underwater exploration.

Read More/Src

Books

Archibald, E.H.H.; Ray Woodward (ill.) (1971). The Metal Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1860–1970. Arco Publishing Co.

Ballard, G. A., Admiral (1980). The Black Battlefleet. Naval Institute Press (NIP).

Brown, David K. (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. Chatham Publishing.

Chesneau, Roger and Eugene M Kolesnik. Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905 page 21.

Friedman, Norman (2018). British Battleships of the Victorian Era. NIP

Fuller, Howard J. Turret versus Broadside: An Anatomy of British Naval Prestige, Revolution and Disaster, 1860-1870. Helion & Co. 2020.

Padfield, Peter, The Battleship Era. London: The military book society, 1972.

Preston, Antony. The World’s Worst Warships. London: Conway Maritime Press, 2002.

Sandler, Stanley “The Emergence of the Modern Capital Ship” London, Newark, Del., 1979.

Links

findthecaptain.co.uk/

The back battlefleet Ballard, G.A. 1862-1948

Macmillan’s Magazine, Volume 22

on en.wikipedia.org/ HMS_Captain

pdavis.nl/Times

on telegraph.co.uk/

commons.wikimedia.org

Videos

Model Kits

detailed model on the greewich coll. rmg.co.uk

on super-hobby.co.uk

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

“The son of a reverend and a navy cadet in 1946…”

He’s a time traveler.

aha well spotted, fixed, thx !