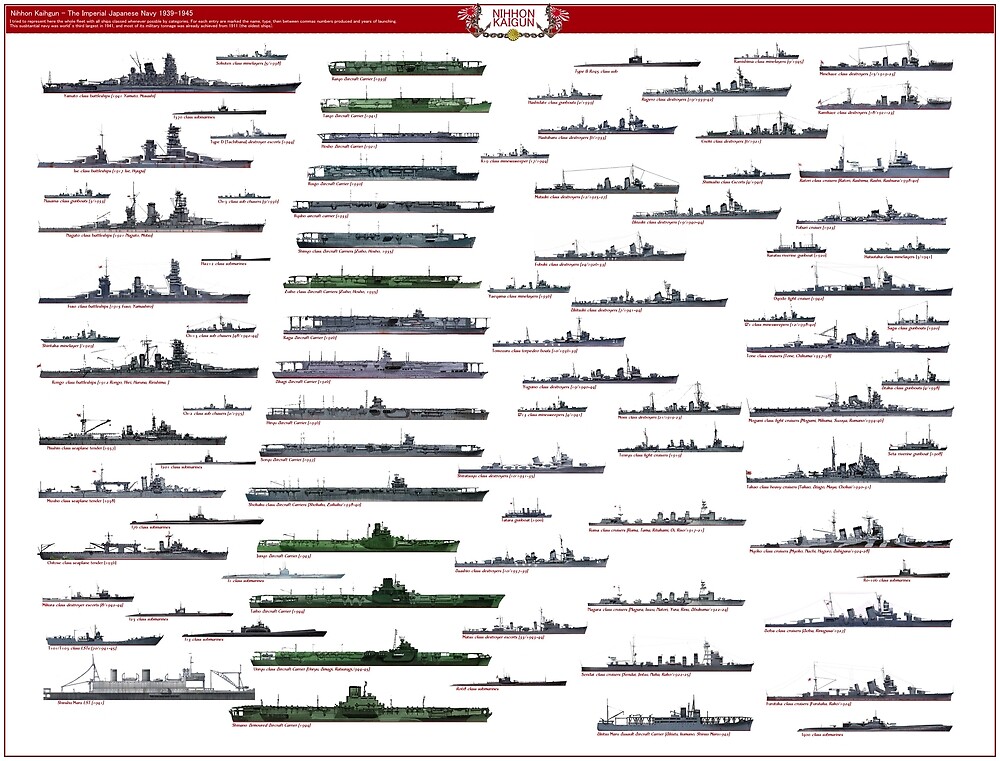

Imperial Japanese Navy

Imperial Japanese Navy

The turning point of the Pacific

The Battle of Midway was one of these moments in history that acts a bit as a hinge, or a crest between two slopes. A downward slope for Japan in this occurence. Until then, never had the USN in such bad position in the Pacific, with its battlefleet sank and left with less aicraft carriers than Japan, which until this summer of 1942 looked unstoppable. But this year 1942 was full of surprises and situation degraded fast for the axis on all fronts, which by caricaturing, lost initiative and went into the defensive for the remainder of the war. Midway was not a “decisive” battle in the sense it did not saw the total destruction of the IJN, but the disappearance of four first-line fleet carriers and elite pilots for the IJN, while boosting the morale of the USN, showing overall the Japanese were not invincible. And yet if this victory was not certain, intelligence, ruse, luck, but also reckless bravery had their part…

One of the ten most decisive naval battles in History

Few naval battles has been really decisive. Back in the past, Salamine saw the destruction of the Persian fleet in the hands of Athenian triremes, probably saving ancient Greece, the cradle of Western civilization and democracy. In 1279 at Yamen off China, the Yuan mongols defeated the Song’s fleet, securing their rule over the middle empire for a century. These years a famous “kamikaze” saved Japan for Centuries to come, also from the Mongols. In 1571 at Lepanto, a Christian states coalition decisively defeated the Ottoman Turks, also securing the Mediterranean northwestern shores of Islamic conquest (This was notably due to innovation, with the Galeasses).

In 1588, the tiny, young and untested Royal Navy faced the Spanish Armada and won, saving Great Britain from certain defeat over the Catholic Spanish Empire. In 1598, at the Battle of Noryang, the Joseon/Ming fleet under legendary amiral Yi Sun-sin decisively defeated the last Japanese invasion, leaving Korea “free” for centuries (notably thanks to Turtle ships, early ironclads). At Quiberon Bay in 1759, the Royal Navy crippled the French Navy, preventing reinforcements to New France (Canada) and helping to win the seven years war, whereas the return match at Chesapeake Bay, by 3 September 1781, helped to win at Yorktown, ending the revolutionary war and securing the very existence of the USA. In 1805 at Trafalgar, the French invasion fleet was virtually unable to sail, deprived of the fleet it needed and Napoleon dropped his invasion plans. At Navarino in 1827, Russia crushed the Ottoman fleet and secured independence for Greece, and in 1853 at Sinope, freed the whole Balkanic peninsula.

In 1894 at Yalu, the Chinese were decisively defeated by the Japanese, never to have any naval ambitions again and in 1905 at Tsushima, the same IJN inflicted a dramatic defeat to Russia which incidental consequences feed the 1917 revolution. In 1916 Jutland was also a gigantic battle, but certainly not decisive: It was a draw with some losses on both sides. However three naval battles were really decisive during WW2: The “battle” of the Atlantic, an ongoing campaign from 1940 to 1944 which allowed Great Britain to survive and the USA to land in Europe and supply the Soviets, and the largest naval clashed ocurred in the Pacific: Midway and Leyte. The second dealt a crippling blow to the already weakened IJN, which was never capable to mount any operation afterwards, but far more decisive was Midway.

This was literraly the hinge of the whole Pacific campaign. Until then a weakened US Navy fought desperate battles, only managing to win a pyrrhic victory prior. Midway was really the battle that turn the table over. Deprived of four aircraft carriers and hundreds of veteran pilots, the IJN was never able to fully regain the initiative, loosing assets the USA was easily capable of compensating. So as we are about to see, Midway was indeed decisive, and althought it was not the total destruction of the IJN, its dividends were many, tactical, strategic, material but also psychologic.

Context: The USN hanging by the nails

Naval Heritage | Jonathan Parshall: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (US War Naval college)

After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the US Navy was in a precarious situation. Now fully engaged with the allies, and deprived of its “Pacific fleet” (of its most visible asset, the battleship row), the United States under the voice of its President FD Roosevelt, decided to fight back and mobilize, but also to prioritize: The West will have priority, and the US Marines were left alone with the assets they can muster to face the IJN unstoppable rampage over the Pacific. Nothing was clearer than the epic struggle of Guadalcanal to illustrate these crucial years of 1942-43.

From December 1941 it looks like a straw of bad news for the USN: The loss of Pearl Harbor was not that complete (fuel tanks were spared as well as the three carriers), but the Philippines soon fell, Guam, Wake, while the Dutch and British lost all their colonies of the South Pacific and the sea of China. Soon Australia itself was threatened. Meanwhile, the USN prepared to fight back and the largest naval battle to this point erupted on the “Coral Sea”, 4–8 May 1942. It is difficult to assess the importance of Midway without having a look on this crucial but Pyrrhic victory.

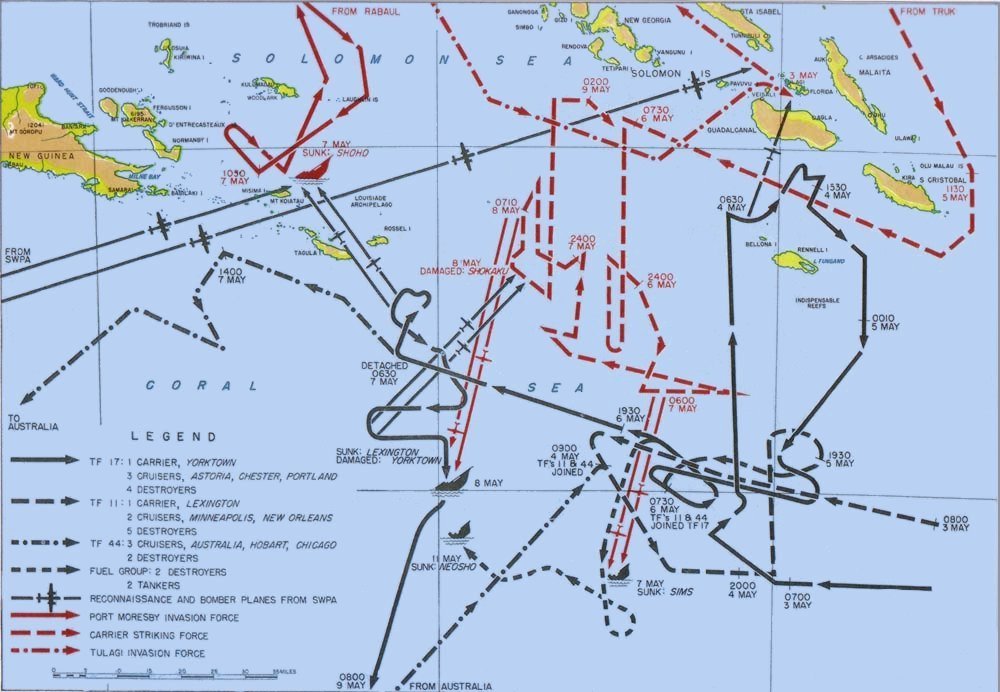

A Pyrrhic Victory: Coral Sea Battle – May 1942

One month before Midway, the Coral Sea saw the largest naval battle of the Pacific so far. This epic clash combined more than 50 ships, including carriers, cruisers and destroyers, on 4–8 May 1942. This battle was quite significant as for the first time in history, both opponents never saw each others. It was the first air-sea battle, fought over the horizon. At the origin, there was the will of the Japanese to secure the southern flank of their Pacific possessions, in what was called Operation Mo, for Port Moresby, one of the IJN targets, in New Guinea the other being Tulagi in the southeastern Solomon Islands.

The Japanese fleet gathered for the occasion was under overall command of Shigeyoshi Inoue (4th fleet), and comprised 2 fleet carriers, 1 light carrier, 9 cruisers, 15 destroyers, 5 minesweepers, 2 minelayers, 2 submarine chasers, 3 gunboats, 1 oiler, 1 seaplane tender, 12 transports while the carriers together can launch some 127 aircraft.

USS Yorktown at the Coral Sea battle. Despite extensive damage she would be available for Midway.

On 3–4 May, Tulagi was in effect invaded and conquered, although some supporting warships were either sunk or damaged by air raids from USS Yorktown. The IJN staff became aware of the presence of U.S. carriers in the area, and their fleet carriers advanced towards the Coral Sea to locate and destroy the Allied naval forces, U.S. Task Force 17 under Franck Jack Fletcher. On 7 May, both opposing carrier forces engaged in mutual airstrikes over two days. The USN rapidly claimed the Japanese light carrier Shōhō, the IJN sank a destroyer, badly damaged a fleet oiler and 8 of May, the IJN fleet carrier Shōkaku was hit and badly damaged, wile the USS Lexington was critically damaged as well as USS Yorktown. Both also suffered heavy losses in aircraft so they disengaged and retired from the coral sea.

This was for the US a Pyrrhic strategic victory as without the carrier air cover, admiral Inoue recalled the Port Moresby invasion fleet, which was saved. It also shown the IJN could be stopped, with aircraft carriers. Tactically the Shōkaku and Zuikaku, either damaged and with a depleted aircraft complement could not participate in the upcoming Battle of Midway, which critically helped the US fleet not to be overwhelmed. The latter battle of Midway of course will stop the Japanese to attempt again any operation against Port Moresby and their troops soon were found in a bitter and ill-fated land offensive over the Kokoda Track.

Terrific explosion onboard USS Lexington. The great fleet carrier was no more, leaving only her sister ship USS Saratoga available for Midway, as well as the “Big E”.

This overall helped the allies to regain a solid foothold in the South Pacific, launching from there the Guadalcanal and New Guinea Campaigns, rebuffing more advances and setting up the stage for upcoming operations in the north. On the other hand, this was a tactical IJN victory in the sense the USN lost two large fleet carriers that would be sorely missing afterwards, USS Lexington, badly damaged and later scuttled, and USS Yorktown, badly damaged and in repairs for a while, while both were depleted of planes and aviators.

Strategic situation May-June 1942

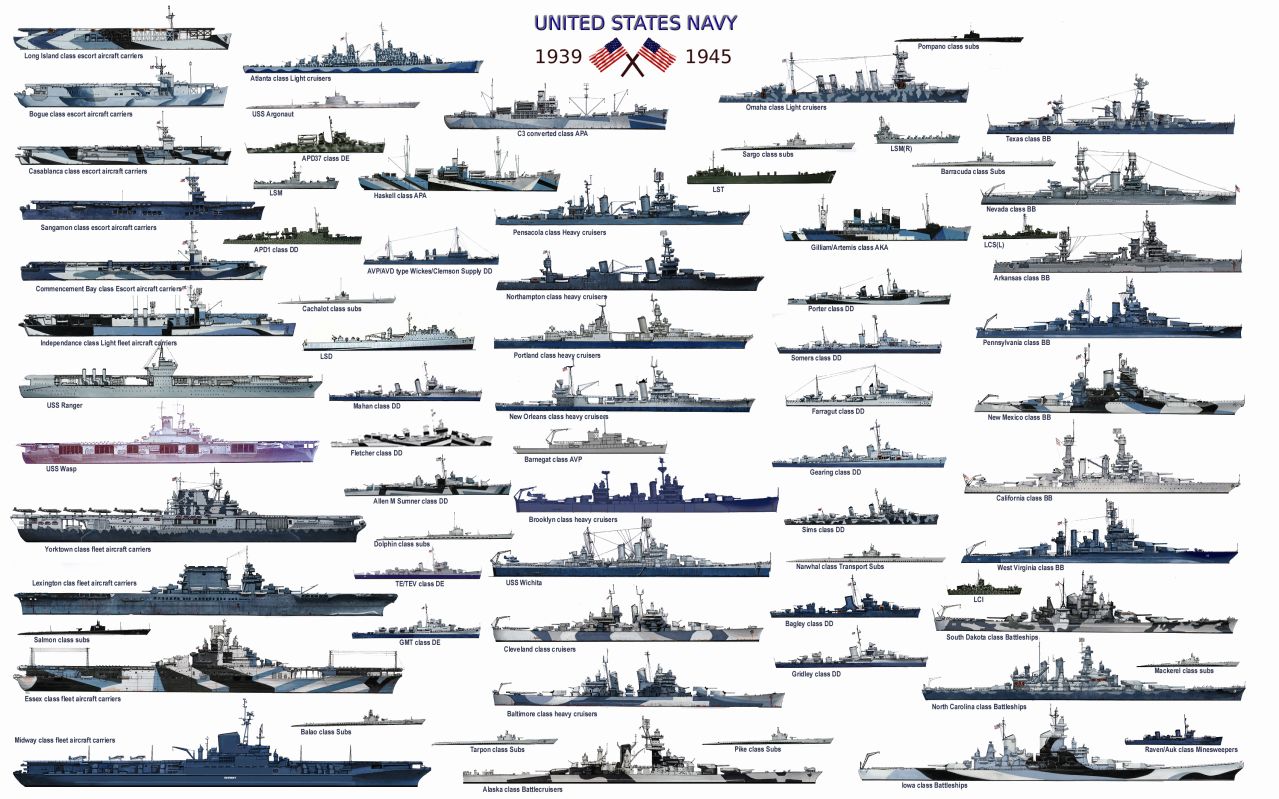

The USN was still in dire straits at this point, with only three fleet carriers available for the operation: USS Enterprise, USS Hornet, and by pure miracle, USS Yorktown (more on this later). USS Saratoga indeed, the only other fleet carrier available in the Pacific (the Ranger was the only USN Carrier in the Atlantic, along with USS Wasp) was delivering planes when between May and June 1942 and would not be available. So all the brunt of the efforts would fell on these three valiant aircraft carriers of the Yorktown class. Together they could muster some 233 planes, fighters, torpedo bombers and dive bombers. Pilots were moderately experienced, but certainly less than the IJN pilots, which for some were war veterans over China since the mid-1930s. We wikk return on this later (see forces in presence).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytk4uG6rpnM

On the American side the strategy was crystal clear: Resisting another attempt by the Japanese to reach their objectives: Taking New Guinea and the Carolines, with the only means left.

On the Japanese side, with forces still largely intact and a morale at its highest, as the general staff attained all its initial strategic goals quickly, the Philippines, Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies and their precious resources for the war effort, the second phase was coming, consolidating the line of defence further on the west and south, and if possible on the long run, neutralizing Australia as a threat.

The second phase started in January 1942. This concerted effort coordinated the IJA and IJN over a wide area of operations but strategic disagreements and in-fighting between the two branches of the Japanese military. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s Combined Fleet won, with a vail threat of resigning, but his strategy was only to start in 18 April 1942, with his plan for the Central Pacific. The idea was to surround and cutoff Australia by advancing westwards, in the Coral sea, securing the Solomons northwards, reaching in the long run New Caledonia to the south and Fiji attoll in the east. Not only this would make a good basis for further attacks on the rich and industrialized west coast of Australia, falling in range of IJA bombers, but also New Zealand was in reach as well.

Yamamoto’s strategy

Beside operations in the souther Pacific the most immediate concern of Admiral Yamamoto was to have free hands was to eliminate as a primary strategic goal America’s carrier forces, namely the Yorktown class and Lexington class. These were only five carriers pitted against a dozen by that time. There was also pressure from the GHQ to do so, especially after the Doolittle Raid on 18 April 1942. This feat was compounded by several successful hit-and-run raids by American carriers in the South Pacific. One of this scenarios was to reiterate an attack of the main U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor, but the now strong presence of bombers at Hawaii made it think it twice.

To draw the USN fleet out of Pearl Harbor and be far away of bombers, he choosed Midway, a tiny atoll at the extreme northwest end of the Hawaiian Island chain. It was i effect 1,300 miles (1,100 nautical miles; 2,100 kilometres) from Oahu and therefore this eliminated the bomber threat. The atoll was not important on a strategic standpoint. It was even too small to be converted as a base. The sole objective was to draw away USN Forces. But it was important enough as he thought for the USN command as a vital outpost of Pearl Harbor, to be defended teeth and nails.

Indeed, the US Command took the locations of Midway very seriously. It was converted after the battle as a U.S. submarine base, allowing them to multiply their range of operation, a seaplane base and a bomber base, able to support operations on Wake Island later. Therefore Yamamoto draw an extensive operational plan, called Operation MI.

Yamamoto’s Operation MI

It was a good example of somewhat overly complex plans the Japanese effectionated, which left a lot of unexpected actions to surge and wreck its realization. As many authors later underlined, it already contained the seeds of its failure: Not only it required a careful and timely coordination of multiple battle groups over hundreds of miles of open sea, but it was also based on an optimistic evaluation of USN forces, notably the presence of only the USS Enterprise and USS Hornet of Task Force 16 to oppose them. This was indeed just after the Yorktown had been considered “eliminated” for months at the Coral Sea. Intelligence also reported the presence of the Saratoga way off this area. Above all, there a gross misjudgment of American morale, especially after what they considered as a crushing victory at the Coral Sea.

The aircraft carrier Akagi, one of the only two converted carriers of the IJN, with Kaga. The others were all purpose-built. She was certainly not optimized at best, but was reconstructed three times and her crews were among the very best of any carriers at sea worlwide at that time.

The whole plan was to lure the U.S. fleet into a trap by using a diversion force. The same plane was repeated in Leyte two years later, also with complicated schemes, and nearly suceeded. Yamamoto dispersed his forces, and his battleships notably, seven of them, out of reach and knowledge of the USN. He created three forces:

> The 1st Carrier Striking Force

Comprising among the best fleet carriers and most experienced airmen the Japan has to offer at that time. Kaga, Akagi, Hiryū and Soryū. Aside these, he still had the two best carriers of the fleet in reserve, those of the Shokaku class. This force was protected by 2 battleships (the two Kongō-class fast battleships), 2 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 12 destroyers and reconnaissance was provided by 16 floatplanes. This force was intended to deliver the fatal blow to the USN force coming from Pearl Harbor, lured by an attack force intended for Midway, the “lure”:

The Midway attack force

This was also called the “Midway Support Force” as they could support the 1st carrier force during the battle, after it was engaged. It comprised four heavy cruisers and two destroyers, with a reconnaissance force of 12 floatplanes.

The Battleship force

This third force was kept in reserve, out of reach, and was to search for and obliterate aby surviving USN ship out the the battle or come sooner in reinforcement. This force comprised two light reconnaissance carriers, 5 battleships, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and the support fleet, aout 35 ships, oilers, tankers, floating workshops, freighters. This dispersion of forces, and the distance between Yamamoto, Kondo’s forces and Nagumo’s carriers was a real problem which was highlighted in the battle. The lack of intelligence in fact doomed operations for the Japanese.

Forces in presence

USN’s Yorktown class

USS Enterprise before the war. A name which became legendary, as its bearer, the “Big E”.

The entire battle, one of the most decisive of WW2 and a turning point in the pacific, rested on the shoulders of a single class of ships: The Yorktown class. These fleet carriers were the second class elaborated on plans after the USS Ranger which was a bit of a prototype in 1933. We should remember that before that, only the USS Langley, considered as an early experimental oddball which formed the first USN aviators, experimented launching and stopping techniques was not frontline and converted battlecruisers were the first true USN fleet carriers, the “lex” and “Sara” as they were affectuously be known. They were conversions, so they left much to be desired in terms of agencement and internal compartmentation. The USS Ranger showed a 23,000 tons carrier was not sufficient to reah the desired speed and this revision led to the 27,000 ton plan of the Yorktown. They were the result of war games by the Naval War College, which highlighted the need for greater flexibility of large air groups, fast speed and better torpedo protection.

The three ships were born in the same drydocks, at Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co. in Virginia. The first two, CV-5 and 6 were laid dow in 1934, launched in 1936, and completed respectively, for the USS Yorktown on 30 September 1937 and for the USS Enterprise on 12 May 1938. The third one, USS Hornet, was laid down with modified plans five years later on 25 September 1939, launched on 14 December 1940 and commissioned therefore on 20 October 1941, not long before the US entry into WW2. They had a large island (much larger than Ranger), were faster at 32.5 knots, and carried more planes, about 90. They set the standard that would be exploited and refined in the large wartime Essex class.

They carried 5 in/38 caliber dual purpose guns while their AA was reinforced considerably and their aviation types evolved also in the span of a few years. USS Enteprise in particular, which survived the battle and the war, operated almost each and every type of USN carrier-borne type since 1938, including the transition from biplanes to cantilever monoplanes, up to helicopters in the 1950. For simplification we will concentrate on the three types on board and avilable at the battle of Midway:

Grumann F4F Wildcat Introduced in 1940 and graually adopted by VFs this was the frst all-metal cantilever fighter of the USN. It maked a great progress but was still inferior in performances to the Mitsubishi A5M. 7,885 were produced overall and it was replaced from 1942 by the Hellcat and Corsair.

Grumann F4F Wildcat Introduced in 1940 and graually adopted by VFs this was the frst all-metal cantilever fighter of the USN. It maked a great progress but was still inferior in performances to the Mitsubishi A5M. 7,885 were produced overall and it was replaced from 1942 by the Hellcat and Corsair.

Douglas SBD Dauntless Certrainly the best known of the three types, as scoring most of the kills in the battle. The idea of a dive bomber came a long way through experimentation. Their deadly efficiency was proved time and again in WW2 notably when seeing the successes of the Luftwaffe’s Ju-87/88 over the Royal Navy. It arrived in units in 1941, and 5,936 were produced until 1945, replaced in practice by the faster Helldiver.

Douglas SBD Dauntless Certrainly the best known of the three types, as scoring most of the kills in the battle. The idea of a dive bomber came a long way through experimentation. Their deadly efficiency was proved time and again in WW2 notably when seeing the successes of the Luftwaffe’s Ju-87/88 over the Royal Navy. It arrived in units in 1941, and 5,936 were produced until 1945, replaced in practice by the faster Helldiver.

Vought SB2U Vindicator The standard USN standard bombers before replacement in 1942 by the TBD Avenger. Only 260 were produced and they saw combat at the Battle of Midway. They were modern cantilever all-metal planes capable of 251 mph (404 km/h) and carrying a 1 × 1,000 lb (454 kg) or a 500 lb (227 kg) bomb.

Vought SB2U Vindicator The standard USN standard bombers before replacement in 1942 by the TBD Avenger. Only 260 were produced and they saw combat at the Battle of Midway. They were modern cantilever all-metal planes capable of 251 mph (404 km/h) and carrying a 1 × 1,000 lb (454 kg) or a 500 lb (227 kg) bomb.

Douglas TBD Devastator: Certainly the oldest planed onboard the Yorktown-class, they were also the only cantilever all-metal torpedo carriers in the USN. Only 130 were built, but they showed poor performances at Midway.

Douglas TBD Devastator: Certainly the oldest planed onboard the Yorktown-class, they were also the only cantilever all-metal torpedo carriers in the USN. Only 130 were built, but they showed poor performances at Midway.

Nagumo’s Kidō Butai

Kidō Butai was the name of the elite fleet carrier squadron of the IJN, the spearhead of the fleet, comprising the best aircraft carriers of the fleet. The squadron already dealt a deadly blow to the USN at Pearl Harbor, attacked and covered all subsequent assaults on various US-held islands and also fought at the Coral sea. However at this battle, the squadron lost one of its scout carriers, Shoho, but more crucially two of its most modern carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, making the Carrier Division 5. The first had been severely damaged and was drydocked for long repairs, while the second lost half its air group. Aicraft Carrier Pilots were not easy to replace, especially with the level of excellence the IJN required.

She was stationed at Kure while intructors worked around the clock to provide these new recruits. Modern historians such as Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully theorized that by combining the remnants of both air groups on the identical Zuikaku alone, the IJN staff could have been better inspired to keep the latter active during the battle. It could have change the outcome. However this was not the Japanese doctrine, for which both the carrier crew and air crew were a single unit and not considered interchangeable, contrary to the USN.

For the battle Nagumo was left with Carrier Division 1 (Kaga and Akagi), and Carrier Division 2 (Hiryū and Sōryū). Crews and ships were subject to fatigue however, as these had been constantly in operation without leave, and ships without proper maintenance since seven months now. Nevertheless, all four carriers combined can deliver 248 attack planes of all types.

Nakajima B5N “Kate” The main IJN torpedo bomber. From 1937, first all-metal cantilever monoplane, the most advanced in the world at that time with folding wings, retractable undercarriage and integral wings fuel tanks. For this role it was designed by engineer Nakamura and produced to an extent of 1,149 planes, replaced by the B6N Tenzan in 1943. It was however also slow and unprotected.

Nakajima B5N “Kate” The main IJN torpedo bomber. From 1937, first all-metal cantilever monoplane, the most advanced in the world at that time with folding wings, retractable undercarriage and integral wings fuel tanks. For this role it was designed by engineer Nakamura and produced to an extent of 1,149 planes, replaced by the B6N Tenzan in 1943. It was however also slow and unprotected.

Aichi D3A “Val” This famous dive bomber had fixed undercarriage like the Stuka, was slow, but dependable, very accurate in the good hands, and agile, capable of hunting down allied fighters. With 1,495 built during their carrier they claimed 16 warships, including a heavy cruiser and an aircraft carrier (Hermes). They were replaced by the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei at the end of the year.

Aichi D3A “Val” This famous dive bomber had fixed undercarriage like the Stuka, was slow, but dependable, very accurate in the good hands, and agile, capable of hunting down allied fighters. With 1,495 built during their carrier they claimed 16 warships, including a heavy cruiser and an aircraft carrier (Hermes). They were replaced by the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei at the end of the year.

Mitsubishi A6M Zero US Intelligence called it the “Zeke”, and it was the most deadly carrier borne fighter until 1942, fast and agile, it surclassed any USN planes. Only by knowing its weak points allied pilots learned to defeat it, notably its lack of protection for the pilot. Despite its radial engine it remained first line until the end of the war and inflicted serious losses to USN attack planes during the battle of Midway.

Mitsubishi A6M Zero US Intelligence called it the “Zeke”, and it was the most deadly carrier borne fighter until 1942, fast and agile, it surclassed any USN planes. Only by knowing its weak points allied pilots learned to defeat it, notably its lack of protection for the pilot. Despite its radial engine it remained first line until the end of the war and inflicted serious losses to USN attack planes during the battle of Midway.

US Intelligence successes

One of the crucial advantages of the US naval staff and Washington was their knowledge of IJN intentions through decyphering their communications. Indeed US codebreakers decyphered JN-25, introduced in 1939, solved in 1941, and by April 1942 JN25 was about 20% readable. U.S. Navy’s signals intelligence command, OP-20-G and Navy’s Combat Intelligence Unit, Station HYPO, also known as COM 14 under Joseph Rochefort. By the time of Midway, the picture was clear for the Americans, unknown to Yamamoto, therefore the emphasis on dispersal and fact that no formations were mutually supportives were known to the Americans, which can choose their target and concentrate on it.

Station HYPO confirmed Midway as the prime target via Captain Wilfred Holmes’s ruse: He told the base at Midway by secure undersea cable to broadcast an uncoded bogus radio message on its water purification being broken, and wait for Japanese interception and traffic within 24 hours. Codbreakers intercepted a Japanese message stating that “AF was short on water”, giving the precious indicative of the target, Midway. No Japanese intelligence officers thought of the apparently uncoded message as a deliberate deception. Thetefore, HYPO could determine 4 or 5 June as the date of the attack, plus the complete IJN order of battle. It happened fortunately also just before the new Japanese codebook was used, delayed.

A diversion Campaign in the north (Operaton AL)

In order to drag attention somewhere else while preparing the attack on Midway, the IJN decided to play o, the scare of a future invasion of the USA by landing troops at the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska, part of the Alaska, on paper an US territory, although far away. This also created a diversion of range for U.S. land-based bombers across Alaska, bound to the Japanese home Islands. Technically this was the first time since 1812 a foreign power landed on “US soil”. This needed a response as many thought a base here for bombers would bring the West Coast of the United States under range. The goal was thought to a feint to draw US forces away, starting one day before the attack on Midway.

https://youtu.be/0pcFpK_mmXw

[Video] Battlefield serie: Midway (1990)

The operations

American preparations

Thanks to USN intelligence, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific fleet made an assessement of all available carriers to be mustered, facing five to six Japanese carriers as expected. Vice Admiral William Halsey’s had at that time a main Task Force of two carriers, Enterprise and Hornet, while USS Yorktown (Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s task force) was in repairs. However tricken with a severe dermatitis he was replaced by Raymond A. Spruance. Yorktown on paper could not be mobilized, but workers of the drydock where she was stationed performed a true miracle, contributing to the final victory:

Thanks to USN intelligence, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific fleet made an assessement of all available carriers to be mustered, facing five to six Japanese carriers as expected. Vice Admiral William Halsey’s had at that time a main Task Force of two carriers, Enterprise and Hornet, while USS Yorktown (Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s task force) was in repairs. However tricken with a severe dermatitis he was replaced by Raymond A. Spruance. Yorktown on paper could not be mobilized, but workers of the drydock where she was stationed performed a true miracle, contributing to the final victory:

Badly damaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea, all realistic estimations gave USS Yorktown a forced immobilization for several months of repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyards. However, as she layed in the Pearl Harnor dockyard to be summarily repaired and sent later to Puget Sound, as assessment was made of her elevators, which were intact and flight deck, still operational. It was decided to concentrate on what could help aviation operations in the shortest time. Therefore Pearl Harbor teams worked around the clock, making the miracle of having the carrier operational within 72 hours. It judged “good enough” by Nimitz for two or three weeks of operations, with a patched flight deck, some internal frames cut out and replaced, and repairs went on with workers on boars assisted by the ship’s team and assisting repair ship USS Vestal (herself a survivor of Pearl Habor, also repaired) at sea.

USS Yorktown’s depleted air group was also resplenished with planes and pilots from several units and scouting unit VS-5 was replaced by a bombing unit (VB-3) from USS Saratoga. VT-5, the torpedo unit, was replaced by VT-3 and Fighting Three (VF-3) entirely reconstituted to replace VF-42. It was made with the sixteen pilots left from VF-42 plus eleven from VF-3 under command of Lieutenant Commander John S. “Jimmy” Thach. Inexperienced pilots soon gave him headaches, like an accident killing Lieutenant Commander Donald Lovelace, Thach’s executive officer. USS Saratoga (under repairs at Puget Sound) was never ready for the coming engagement, and therefore her planes replaced the losses of Yorktown. Nimitz therefore was left with three carriers under potentally the double on the Japanese side.

The base of Midway itself comprised four squadrons of PBY Catalina long range patrol seaplanes (24), six brand-new Grumman TBF Avengers (Hornet’s VT-8). The Marine Corps operated there 19 Douglas SBD Dauntless, seven F4F-3 Wildcats, 17 Vought SB2U Vindicators, and 21 Brewster F2A Buffalos. USAAF forced here had a full 17 B-17 Flying Fortresse squadron plus four Martin B-26 Marauders, also brand new, and fitted with torpedoes. The grand total of the base, seen as a “fourth and insubmersible aicraft carrier” could launch 126 aircraft, includung long-range heavy bombers that can be decisive in the engagement. Thanks to HYPO codebreakers, Nimitz knew this three carriers’s air fleet, plus the one from Midway, gave a rough parity with Yamamoto’s four carriers force, as known to be there.

Japanese preparations

The most cruel discrepancy from the Japanese was the total lack of intelligence towards the strength and position of the USN fleet. Another problems was the lack of industrial resources at large, as decision to cut or stop the production of the “Val” and “Kate” meant there was no replacement for the losses, not to speak about pilots. In addition those who were present accumulated fatigue for constant service since November 1941, and the planese, despite a good maintainance lacked spare parts and were for some, seriously worn out and subjects of more frequent breakdowns. This made the four carriers available not only lacking in quantity but also quality despite the high morale and skills of the pilots.

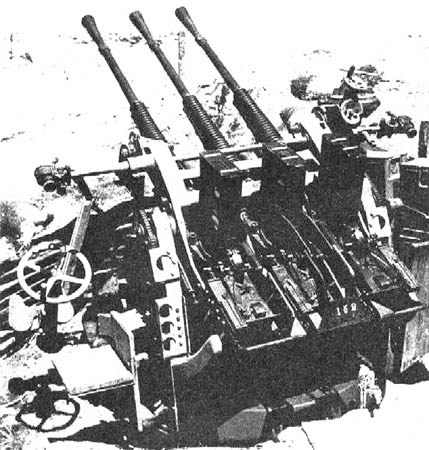

Outside the lack of radars, the most severe limitation of Nagumo’s carrier fleet, as revealed already at the Coral Sea, was the poor AA artillery protecting the ships: Most were ageing 25 mm cannons derived from a French Hotchkiss ww1 design and batteries lacked a good fire control system. Moreover, Japanese C&C was also poor, with difficult radio coordination of the fighter planes. The carriers themselves had several escorting ships, but not only their proper AA suffered from the same limitations, but doctrine and coordination as a defensive battle group was just not developed in the IJN at that time. IJN Cruisers and destroyers were trained for surface combat and agressive manoeuvers, not AA defense. All these factors further diminished the four carrier force efficiency.

Admiral Yamamoto was onboard IJN Yamato in reserve during the battle, too far away to support Nagumo.

Added to these internal factors, preparations for the battle went badly: Yamamoto advised to create a scouting veil prior to the battle, a picket line of Japanese submarines. It was getting too late into position, notably because of Yamamoto’s own haste. Therefore, while moving towards Midway, the American carrier force arrived at their assembly point northeast of Midway (“Point Luck”) undetected. Four-engine H8K “Emily” flying boats also tried to locate the location or departure from Pearl Harbor of the USN carriers (Operation K). This failed as Japanese submarines suppliers stumbled upon American warships at French Frigate Shoals and had to turn back. The “fog of war” applied to Nagumo and Yamamoto that day, whereas the US looked at their game in the mirror. It seemed however Tokyo detected an increase of American submarine activity and message traffic, information transmitted to Yamamoto and apparently also Nagumo, but both did not changed their battle plans.

Read More

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-47

www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/battle-of-midway

www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Midway

www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-battle-midway-180973516/

wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Midway

wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Coral_Sea

historynet.com/joe-rocheforts-war-deciphering-a-code-breaker.htm

history.navy.mil/our-collections/art/exhibits/conflicts-and-operations/wwii/art-of-the-battle-of-midway.html

www.naval-encyclopedia.com/ww2-naval-battles/

www.fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/2e-guerre-mondiale/us-navy-2egm.php#pa

Classic Pictures Entertainment – Battle of Midway

Midway Battle – 2000s documentary

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nf3lQ2DAxpQ 1952′ “flat top” movie

The Battle

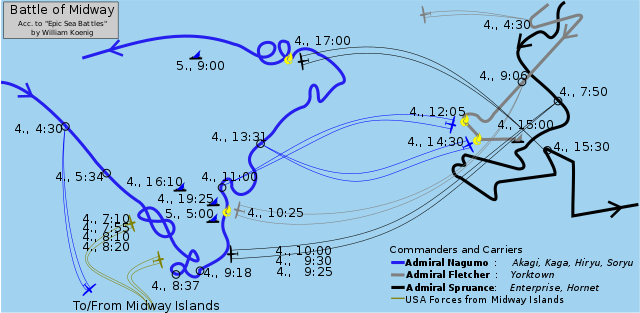

Deployment map of the battle (cc) by William Koenig in Epic Sea Battles

Initial air battle: Midway’s attacks

At 09:00, 3 June, American PBY seaplanes were deployed in the Pacific and Ensign Jack Reid of Navy patrol squadron VP-44, spotted the IJN squadron occupation Force at around 500 nautical miles (930 km) west-southwest of Midway. He mistakenly reported however this was the Main Force. Immediately at Midway, nine B-17s took off at 12:30. Three hours later they spotted Tanaka’s transport group still at 570 nm (1,060 km) westwards, and attacked. Despite Japanese AA fire they dropped their payload, and despite hit reports on four ships, none was. The Japanese only had a few near-misses.

The following morning the Japanese oil tanker Akebono Maru however was spotted and attacked by an armed PBY with torpedoes, around 01:00 the only successful airborne torpedo attack of the whole battle from the USN, an a pitiful restult regarding the entire numbers of torpedo planes deployed.

Consolidated PBY Catalina

At 04:30, before dawn, 4 June, Admiral Nagumo was in range to launch the first attack on Midway, with 36 Aichi D3A dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers, covered by 36 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters. He also launched eight spotter aircraft from his fleet’s cruisers but these were few to cover the assigned search areas. Added to this, the weather was poor to the northeast-east of the Japanese fleet. At the same moment at Midway, 11 PBYs took off for their own search at 05:34, one reported two Japanese carriers. Another also crossed the inbound Japanese airstrike group.

Midway as also equipped by an early radar (the sae system as Pearl Harbor), picking up the carrier-borne strike force at several miles, time to scramble interceptors while the remaining bombers took off to attack Nagumo’s fleet, without escort, defining Midway. At 06:20, the Japanese attacked went through the weak fighter scree (US Marine fighters were led by Major Floyd B. Parks, which can only do what he could with his six F4Fs and 20 F2As) and struck the base, causing heavy damage. Parks squadron only downed four B5Ns and a single A6M Zero for two F4Fs and 13 F2As destroyed. On the ground all remaining U.S. planes not in the air were badly damaged, only two surviving. American AA fire on Midway was however intense, accurate, destroying three more and damaging others.

In total 11 IJN planes never returned, and that included three that ditched on return while 14 returned badly damaged, and 29 other lightly damaged. Midway was not neutralized however. When coming back, the 15 B-17 bombers from 31st, 72nd, and 431st Bomb Squadrons could still use the airfield and refuel for further attacks. Midway’s land-based defenses were also intact, and this was reported by Japanese pilot. Therefore a second aerial attack was decided by Nagumo and prepared before the main assault took place. Nimitz’s “fourth carrier” was still operational and needed to be eliminated if the Japanese wanted to capture it by 7 June.

Meawnhile, Midway’s six Grumman Avengers (From Hornet’s VT-8) and 11 SB2U-3s and 16 SBDs from the Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron 241, plus four B-26s Marauders of the 18th Reconnaissance & 69th Bomb Squadrons with torpedoes all arrived in range of Nagumo’s fleet. The Japanese repelled these attacks, losing three fighters but claiming five TBFs, two SB2Us, eight SBDs, and two B-26s. Major Lofton R. Henderson (VMSB-241) at the head of his inexperienced Dauntless squadron was kill in action and later the famous main airfield at Guadalcanal was named after him. He was one of the many US armen that will be thrown in the furnace during this battle.

Bravery also led to sometimes desperate moves: One B-26 was badly crippled by AA fire without hope of returning. The pilot decided to make a suicide run on Akagi, however he narrowly missed the carrier’s bridge, housing Nagumo and his command staff. We can only imagine what would have been the result othewise. This further bolstered Nagumo’s determination to launch a second attack on Midway despite Yamamoto’s strict order to keep a reserve strike force in case the USN Task Force was attacking. A decision that was to have serious consequences.

Nagumo’s fatal decision

Yamamoto’s orders for Operation MI has been to keep half of the aircraft in reserve, two squadrons of dive bombers and two of torpedo bombers to attack the USN Task Force. Dive bombers in the hangars has yet to be armed on the flight deck as IJN doctrine commanded, just like the torpedo bombers after being all raised on the deck and assigned to preparation spots, if an only if American warships were located. Indeed, in the other case, the narrow decks needed to be kept bare for returning aircraft to land safely.

At 07:15, Nagumo took the decision to have this reserve armed with contact-fused general-purpose bombs for land targets on Midway, including the torpedo bombers. This operation was underway for about 30 minutes when at 07:40 a delayed scout plane that took off 30 min. late from IJN Tone signaled a large American naval force to the east. Nagumo however did not receive this report until 08:00. By then, the admiral quickly reversed his order, and the teams feverishly tried to dismount general-purpose bombs and replaced them by normal payload for a ship attack. Nagumo also asked for the scout to make sure of the composition of the American force, 20–40 minutes elapsed before the scout made the report of a single carrier, one of the Task Force 16 while the other was not spotted.

Armed with new information, Nagumo was now indecisive. Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi (Carrier Division 2, Hiryū and Sōryū), recommended a naval strike immediately with his 18 Aichi D3A1 dive bombers on Sōryū and Hiryū, and cover patrol aircraft. However Nagumo was also informed by the imminent return of his Midway strike force. He therefore was in dire straits, with a bare deck waiting for planes that were not in sight by a far margin, whereas he needed to strike the USN Carrier asap. There were a few permanent fighters on the flight decks in case of an attack, with extra ones on Sōryū to make additional combat air patrol. Nagimo knew that lifting on the deck all his planes and preparing them for launch would have required more than 30 minutes in the best case scenario. Furthermore, he would throw into combat planes still armed with imprper armament, and worts, without a proper air cover and the devastation of the midway’s USN squadron made him think twice about it.

By default, Japanese carrier doctrine imposed the launching of fully constituted strikes. Strict confirmation of the approaching American force’s carriers strenght was not at hand before 08:20 so Nagumo decided y shoft into default mode and wait. The wait allowed him to rearm properly the reserve before launch. Meanwhile however, Fletcher’s carriers, USS Hornet and Enterprise launched their planes at 07:00, completed by 07:55, joined by Yorktown at 09:08. They were already on their way whereas Nagumo stuck to carrier doctrine, and there were little chances a change of mind would have stopped the impending USN attack anyway.

The USN’s finest hour

Fletcher’s management of the air strikes

Admiral Fletcher was in USS Yorktown, fed informations by a PBY on the area since the early morning. He has ordered Spruance to launch as soon as was possible while voluntarily holding Yorktown in reserve, just in case other Japanese carriers were spotted in the meantime. The range was extreme however, but still a strike could succeed and the order was given. Halsey’s Chief of Staff, Captain Miles Browning prepared and and overlooked the launch, into the wind, to use the light southeasterly breeze allowing them to place some distance quicky from the Japanese at high speed in case. Indeed, compounding by Washington, the order of the day was to avoid exposing too much the only remaining USN carrier force in the Pacific.

Miles Browning suggested a launch time of 07:00, to coordinate the carriers, giving one more hour to close on the Japanese. Both carriers were making 25 knots by then (46 km/h; 29 mph) and the launch was supposed to be made at about 155 nautical miles (287 km) from the Japanese fleet, ensuring for the planes a return flight time. However, it was assumed the Japanese force did not change course in between. Yorktown’s commanding officer, Captain Elliott Buckmaster and staff were now proficient and the full strike was ready fast. They have been experience already in the Coral Sea, but Enterprise and Hornet were relatively “green” in this aspect and therefore it’s why they were ordered the first strike. Spruance also ordered this first strike force to not wait for the others to assemble, but proceed immediately on the expected target position. He perfectly knew that striking first was key for the survival of his own task force.

US initial Gamble

Less proficient than the Japanese to prepare and launch a full strike, (The IJN could launch 108 aircraft in just seven minutes), the “green” Enterprise and Hornet too about an hour to launch their 117 planes. The great risk was these planes arrived piecemeal but Spruance wanted them in the air and towards the enemy as soon as possible. That was an important factor as fighters, bombers, and torpedo bombers did not flew at the same speeds and they proceeded to the target different groups, one after the other. This lack of coordination and cover wcould prove disastrous, and indeed nearly caused the strike force to be entirely wiped out.

Less proficient than the Japanese to prepare and launch a full strike, (The IJN could launch 108 aircraft in just seven minutes), the “green” Enterprise and Hornet too about an hour to launch their 117 planes. The great risk was these planes arrived piecemeal but Spruance wanted them in the air and towards the enemy as soon as possible. That was an important factor as fighters, bombers, and torpedo bombers did not flew at the same speeds and they proceeded to the target different groups, one after the other. This lack of coordination and cover wcould prove disastrous, and indeed nearly caused the strike force to be entirely wiped out.

Spruance anyway calculated this was worthwhile. He also knew Japanese doctrine prevented them to launch a counter air strike if it was not fully constituted, and Spruance’s aerial attacks would make the unable to do so. This was clearly a gamble, he hoped to find Nagumo with his flight decks at their most vulnerable, or “pants down” in less official US parlance.

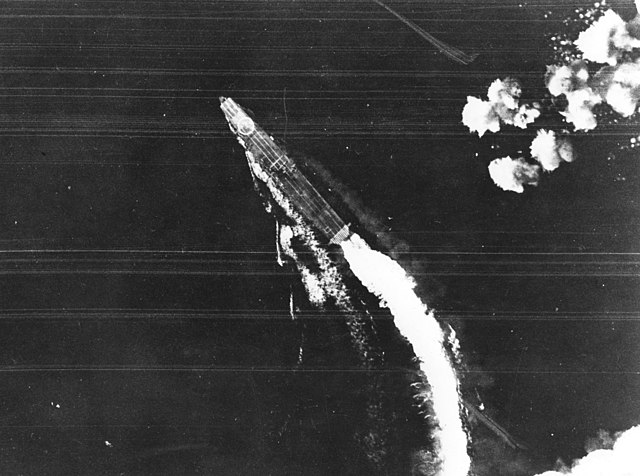

Hiryu manoeuvering to avoid bombs, 4 June 1942

USN disastrous initial attacks

Initially the US strike force did not locating the target where it was supposed to be, despite positions given. Moreover Hornet’s strike group, Air Group Eight (dive bombers) under Stanhope C. Ring was on a heading of 265 degrees (instead of the 240 degrees indicated in the report) resulting in that his dive bombers missed the carrier force. Torpedo Squadron 8 from Hornet (Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron) initially behind Ring broke formation when he guessed it was not the correct heading and eventually spotted the carrier force. They arrived quite vulnerable however, as the ten F4F Wildcats (USS Hornet) which were to bring them cover passed their range, went out of fuel, and ditched.

Waldron’s squadron attacked at 09:20. He was followed at 20 min. interval by dive bombers of VF-6 from USS Enterprise, also without Wildcat escorts, which turned back. Because of this, all fifteen TBD Devastators were shot down without before arriving on range. Ensign George H. Gay, Jr. was the only one to survive. VT-6 lost nine Devastators (out of 14), while Yorktown’s VT-3 (the last arrived, at 10:10) were shot down, loosing 10 of 12 Devastators. Compounded to this, in the rare cases they were able to launch their Mark 13 torpedoes, none hit. Midway would prove to be the final nail in the coffin of the Devastator as a torpedo attack plane. A dozen of so has been launched, taking great risks at ensuring they were very close to the targets. USN pilots knew the Japanese were expert as manoeuvering agressively to avoid them. But if the latter dodged some, most were launched much too close to miss and nobody cared afterwards in the reports why there was such abysmal performance of the torpedoes.

The Dauntless’ finest hour

What started badly had however a few advantages, which perhaps not outwight the scope of the sacrifice made, but ensured anyway the final result: The American torpedo attacks kept the Japanese carriers off balance. As expected by Spruance they did not prepared and launch their own counter attack. Japanese combat air patrol were out of position busy with the incming USN planes, unable to dodge other incoming attacks. Also by that time, Zero fighters were running low on ammunition and fuel. The third torpedo plane attack from the southeast (VT-3, USS Yorktown, 10:00 drew the Japanese CAP there, and Nagumo therefore had no fighter left to be sent at any other quadrant.

The result was all but favourable for three squadrons of Douglas SBD Dauntless from Enterprise and Yorktown were approaching from the southwest and northeast. The Yorktown squadron, VB-3 behind VT-3 fortunately changed course was was now ready to attack, on site, whereas two squadrons from Enterprise VB-6 and VS-6 were running low on fuel while searching for the enemy. Commander C. Wade McClusky, Jr., still searching eventually spotted the wake of the Japanese destroyer Arashi steaming towards Nagumo’s carriers. She was diverted indeed to chse and depht-charge U.S. submarine Nautilus, which just just failed torpedoes IJN Kirishima. It was so desperate before this commenced that several Dauntless ran our of fuel and had to ditch at sea.

The result was all but favourable for three squadrons of Douglas SBD Dauntless from Enterprise and Yorktown were approaching from the southwest and northeast. The Yorktown squadron, VB-3 behind VT-3 fortunately changed course was was now ready to attack, on site, whereas two squadrons from Enterprise VB-6 and VS-6 were running low on fuel while searching for the enemy. Commander C. Wade McClusky, Jr., still searching eventually spotted the wake of the Japanese destroyer Arashi steaming towards Nagumo’s carriers. She was diverted indeed to chse and depht-charge U.S. submarine Nautilus, which just just failed torpedoes IJN Kirishima. It was so desperate before this commenced that several Dauntless ran our of fuel and had to ditch at sea.

McClusky’s decision to continue the search was later parised by Nimitz, as it “decided the fate of our carrier task force and our forces at Midway”. By chance, all three American dive-bomber squadrons arrived almost simultaneously at perfect locations and altitudes to attack whereas Japanese fighters were busy elsewhere. In the meantime, Japanese teams were busy arming Japanese strike aircraft in the hangar decks, with fuel hoses opened, no satefy measures taken to gain time while bombs and torpedoes were stacked around the hangars out in the open. This all prepared the inpending doom.

IJN Kaga

At 10:22, the Enterprise’s air group split up, one to attack Kaga and the other Akagi, but intstead because a communication bug both squadrons concentrated on Kaga. Lieutenant Richard Halsey Best and his two wingmen pulled out of their dives after judging that Kaga was doomed already, recoignising their error and headed for Akagi. Kaga took four or five direct hits and its bridge was blasted, killing Captain Jisaku Okada and his staff, by a bomb from Lieutenant Clarence E. Dickinson. Best and his two wingmen dove on Akagi, to the horror of Mitsuo Fuchida (Pearl Harbor celebrated flight commander).

IJN Akagi took one direct hit, which struck the edge of the mid-ship deck elevator, penetrated to the upper hangar and exploded among the aircraft stored inside, in the middle of fuel and ammunition. Ryūnosuke Kusaka recalled the result, a gigantic ball of fire that streamed inside the hangar, causing cascading explosion and the impossibility to control it. Another miss-hit was very close astern but the geyser apparently was strong eniough to push the flight deck upward while the rudder was torn up.

Yorktown’s VB-3 (Max Leslie) headed meanwhile for Sōryū, which took three hits causing extensive damage. Strangely, a few of these had electrical mishaps wich cause them to accidentally released bombs when using arming switches. But they still dove to strife the carrier decks, providing additional cover against AA guns. VT-3 Dauntless bombers also dove on Hiryū, but missed. Soon Sōryū and Kaga had gigantic fires that the teams were unable to master and which spread rapidly. All three carriers remained afloat despite of this long after they had been evacuated and they were scuttled by destroyers fuiring torpedoes at them. Meanwhile the various USN air groups tried to fly back, but most ditched at sea, out of fuel.

IJN Hiryū at first miraculously escaped the Dauntless attack.

The Japanese counterstrike

Hiryū, sole surviving aicraft carrier soon launch a first attack wave, 18 D3As covered by six fighters. They followed the retreating American aircraft and found the first carrier, USS Yorktown. The latter was soon hit by three bombs. One blew a hole in the deck, and out all but one of her boilers went silent. Admiral Fletcher ha dlater to move his command staff to the cruiser USS Astoria but better American damage control teams soon dealt with fire and temporarily patched the flight deck, also restoring power to several boilers. After oe hour, Yorktown was able to steam at 19 knots and resume air operations. In all, all the 18 dive bombers and three escorting fighters were lost. Earlier, two of the escorting Zero fighters turned back after duelling against followed Enterprise’s SBDs. Their feeble construction did not managed well the bursts of twin 0.3 cal. Brownings of their rear gunners.

One hour later IJN Hiryū launched a second attack wave, consisting of ten B5Ns and six escorting A6Ms, arrived over Yorktown; They were surprised. Instead of finding a burning wreck, the repair efforts has been so effective as to make the Japanese pilots think this was a different carrier. Yorktown was oon hit by two torpedoes, lost all power while taking a 23-degree list to port. Half of the torpedo bombers were lost as well as two Zeros in the attack. The report back to Nagumo sowehwat bolstered morale for the Japanese. They undeed thought having sunk one and badly damaged another carrier, and soon decided to launch a third strike with all the planes they could muste aboard Hiryū. They decided to launch them against the only remaining American carrier.

The American attack on Hiryu

It was laready late in the afternoon when a scout aircraft from USS Yorktown spotted IJN Hiryū. The report back make launch from USS Enterprise a final strike made of 24 dive bombers, all what remaining from survivors of all three carriers, six SBDs from VS-6, four SBDs from VB-6 and 14 SBDs from VB-3. Hiryū as waiting them with more than a dozen A6M Zero fighters. Dsespite of this, the air strake found the Japanese carrier and went through Japanese defenses, hitting the carrier with four or five bombs. Hiryū was soon ablaze, and cannot launch her own aicrafts. The USN Task Force was safe, at least from any carrier-borne threat. USS Hornet also launched a patchwork strike force, but because of miscommunication, the se planes arrived too late, and seeing the already burning carrier, concentrated instead on the remaining escort ships. However the faster cruisers and destroyers were much more nimble and agile targets. None was hit while the air group lost some planes to AA fire.

Meanwhile, in the doomed carrier, attempts of taming the blaze by control crews all but failed as for their intensity soon grew fiercer. Evacuation was ordered soon, and the remaining escort ships headed northeast. The idea was to attempt to catch the American carriers, and engage them with artillery and torpedoes. Before leaving, a Japanese destroyer torpedoed the burning carrier, but did not stayed to see the ship sinking. A crucial assumption that would be probven fallacious, as Hiryū stayed afloat for hours, in fact during the night and the next morning to be spotted by an aircraft from carrier Hōshō. Hopes to save her make Nagumo sending two ships to try to tow her back to Japan. But long before they arrived, Hiryū eventually sank with Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi and captain, Tomeo Kaku on board, two of the best IJN carrer officers at that point.

Hiryū before sinking, as shot by Special Service Ensign Kiyoshi Ōniwa from the carrier Hōshō.

Attempts at a night battle

With darkness falling, both fleet commanders look at their options. Admiral Fletcher had no choice but to leave Yorktown behind. Admiral Fletcher ceded his seat to Spruance at this point. The latter knew that it was a great victory, but not knowing the position of remaining Japanese forces he was determined to safeguard at the same time the island of Midway and his carriers if he can. Although the aviators were ill-prepared for night operations, he started to close the distance with the supposed position of Nagumo, allowing his planes to attack and retreat without running out of fuel.

The fate of Yorktown

Safety teams failed indeed to control the severe gushing of water to make the ship move again, compounded by its total lack of power. But there were still hopes to save her, and at least to try to two her to safety. Salvage efforts were encouraging in the end, enough for she was taken in tow by USS Vireo. However, on the afternoon on 6 June, the Japanese submarine I-168 passed through destroyers deployed around and fired a salvo of torpedoes. Yorktown was struck twice, and this time these were much heavier 533 mm torpedoes, not 450 mm airborne ones. Casualties were few fortunately, near the point of impact, but the carrier was now doomed for good. A third missed the hull to strike the destroyer USS Hammann stationary boarding Yorktown and providing her auxiliary power. The destroyer immediately broke in two, sank with 80 lives, most of which died when her depth charges exploded. Repairs repair crews were evacuated from the carrier sank at dawn around 05:00 on 7 June. Crews had tried to save her for more than 24 hours, as she took four bomb hits, two aerial and now two marine torpedoes.

Spruance retire, Yamamoto attack on midway

However the night fight never happened. Japanese surface forces were still a threat, nearby Yamamoto also, based on a misleading report from submarine USS Tambor. Eventually Spruance decided to change course, withdrawing eastwards around midnight. We can guess at this point, there was still the fear of loosing his precious carriers. Yamamoto meanwhile on his side sent his remaining surface forces eastward in attempt to catch the American carriers. A single cruiser was detached to shell the island of Midway. Eventually, the surface forces never made contact with the Task Force, the lack of radar not helping either. Yamamoto eventually ordered a general retreat westwards. The prudent decision of Spruance was later saluted, as the few escort cruisers of the carriers were an easy prey for battle-hardened Japanese crews well-versed into night fighting (as seen later around Guadalcanal). Above all, the Yamato alone could have made short work of these at long range while her AA could have repelled any air attack.

6-7 June great search and destroy mission

Spruance, which after retreated went back during the early hours of the morning however launched on 5 June several search planes but failed to spot Yamamoto. During all this day he launched a wide search-and-destroy mission to atempt to find any Nagumo’s force remaining vessel in the area. One of Yamamoto’s main fleet Japanese destroyer was spotted and attacked, without success by strike planes. They eventually returned to the carriers after nightfall, while Enterprise and Hornet had all on their lights turned on to help landings.

Failed opportunities

Around 02:15, 6 June, Captain John Murphy of USS Tambor, 90 nautical miles (170 km) west of Midway sighted several ships, but failed to identify them, including knowing if they were friendly or not. He did not dare to approach and instead launched a report of “four large ships” to Admiral Robert English. The latter was at hte head of the Submarine Force of the Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC). It was passed on to Nimitz, and sent to Spruance while the latter was furious of the nature of it. Still unaware of the exact position of Yamamoto and is strenght he was forced to assume the ships reported by Tambor made the bulk of the main invasion force. Staying 100 nautical miles (190 km) northeast of Midway he made ready an air strike.

The ships were in fact a detachment of four cruisers, two destroyers sent in reinforcement to shell Midway. At 02:55, Yamamoto gave them the order to retire, which Tambor sighted and reported, while later being discovered. While maneuvering to avoid a submarine attack, Mogami and Mikuma collided. Mikuma slowed to 12 knots to escort the badly damaged Mogami. Dawn arrived at 04:12 and Murphy surfaced to try to identify the ship, but soon dived to approach for an attack., which failed. Around 06:00 he reported the course of the two Mogami-class cruisers westwards, and dove again, not trying to attack anymore.

This behaviour made Murphy relieved of command after the battle, reassigned to a shore station. Meanwhile Fletcher went on until passing by Wake island, at which point he decided to not attempt his luck anymore and turned back. He would not stop there however, and assumed command by transferring his flag on the USS Saratoga on the afternoon of 8 June, returned to Midway with Hornet and Enteprise and at this point launched more S&D missions on 8-9 June until he was absolutely sure there will be no more attempts of the Japanese on the island. The whole operation was called off on June 10 ad the fleet retired to Pearl Harbor.

Aftermath

Losses assessments

Japanese losses

On 6-7 June 1942, there were additional air strikes from Midway and from Spruance’s carriers. IJN Mikuma was eventually spotted, and sank by SBD Dauntlesses dive bombers. Mogami however despite her severe bow damage made it back home for repairs. Arashio and Asashio were bombed and strafed, but none sank. Nevertheless, the Japanese lost that day around 3000 personal total, four of their six elite carriers, Kaga, Akagi, Hiryu and Soryu, the cruiser Mikuma, the fleet oiler Akebono Maru while other vessels were damaged. But more than that, they lost nearly 200 planes with very experienced, first-rate pilots, including veterans since 1937. Drastic Japanese pilot training process meant they were will not be able to replace them anytime soon. Carrier-side, the Japanese industry (as correctly estimated by Yamato) was no match for the US industry and the lost carriers were only replaced on a per-unit basis by late 1944, which at that point mattered far less.

A battle kept under secret

On 10 June, there was a top meeting conference of the IJN about assessing the results of the battle. Chūichi Nagumo battle report was submitted on 15 June and guarded closely throughout the war, and stayed unknwown of the general public and the army and navy alike which were kept in the dark on this battle. Nagumo’s striking revelations were its estimates of the enemy awareness aware of IJN plans before the 5, or so it was believed at the time, unaware of US Code breaking work. The general opinion in Japan was that the fleet was in good shape and ready for more operations.

Nagumo’s fleet was backe to Hashirajima on 14 June. Wounded transferred to naval hospitals were immediately shut down from other persona under guard as “secret patients”. The poor fellows ended in isolation wards, quarantined from other patients, their own families kept away. Remaining officers and men were dispersed to other units of the fleet and not allowed to see family or friends, quicky sent in the South Pacific, where most were lost without revealing the outcome of the battle. Flag officers or staff were not penalized for their actions, as a trial would have been not a discreete affair. Nagumo was never sacked and instead, soon in command of the rebuilt carrier force.

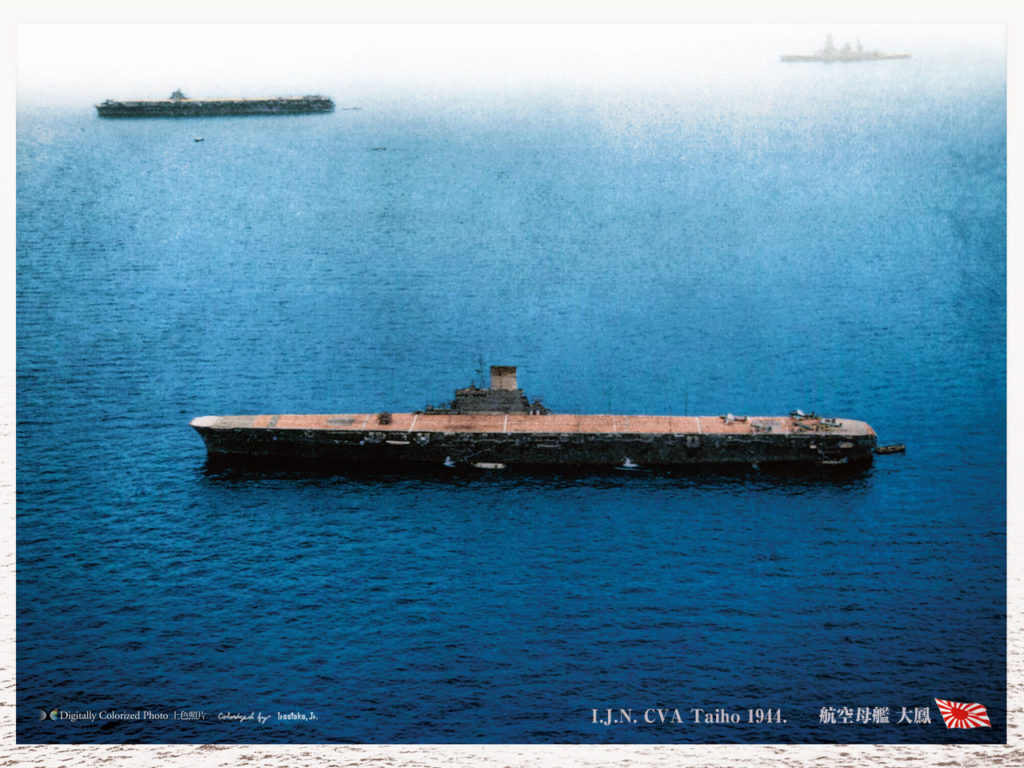

IJN Taihō (Launched April 1943), one of the fleet carriers that were supposed to replace the losses at Midway. She sank after being hit by bombs because of the total inneficience of her control teams as well as design flaws. After Taihō, only Shinano (the third Yamato-class), converted, could be compared, but after Midway, the fleet was left with two carriers of the Zuikaku class with depleted crews and damaged, the Ryūjō and Zuihō light carriers, second-rate, and Jun’yō and Hiyō escort carriers which were not fleet operative.

Reports from the battle however had the merit to trigger doctrinal changes in the IJN: New procedures to refuel and re-armed planes on the flight deck rather than in the hangars, draining all unused fuel lines, whereas the new carriers ordered had a stronger flight deck, only two flight deck elevators and completely redesigned firefighting equipment while crew members were better trained in damage-control and firefighting. Despite of this, for Shōkaku, Hiyō, and Taihō this would not be sufficient. There was no improvements however of an aspect that remained secret on the uS side and proved decisive: The importance of naval cryptanalysis and intelligence-gathering. Staggering Japanese deficiencies in this aspects denied the margins that would have perhaps decided Nagumo to strike first, and win the battle as a result, judging by the performances of Hiryu’s squadrons.

US losses

Outside the many planes and pilot lost, sometimes in futile approaches, poor performances of aerial torpedoes, communication breakdowns that led to errors, the USN escape this battle with no ship loss -that it until the Japanese I-168 stroke. That ship became the most successful in the entire combined fleet that day, claiming in one salvo a precious aircraft carrier and a destroyer. 307 Americans had been killed including Major General Clarence L. Tinker, Commander of the 7th Air Force. His plane crashed when attempting a search and destroy mission from Hawaii on 7 June.

Spruance was criticized later for not having more agressively puruse the retreating Japanese fleet during the 5-6 June night, but if the risk of stumbling upon a potentially far superior night-trained battlefleet was a reason, his air group has been severely depleted at this point, whereas Yamamotos’s remaining ships had an intimidating AA. Moreover, his fleet was about to run out of fuel. There were also unlikely survivors of this battle, wich were made prisoners. Three airmen were picked up by destroyers and cruisers of Nagumo’s fleet and later detained in POWs, or executed. Two survivors from IJN Mikuma were rescued by USS Trout and 35 survivors from Hiryū by USS Ballard.

Between the Stukas in many occasions, the Aichi “Val” at Pearl and other occasions, and the SBD Dauntless, dive bombers proved before the missile era, perhaps to be the best “ships killers”. Indeed, classic high altitude bombings by B-17s proved usueless (a general rule during the war BTW, despite pre-war craze about the concept, by Douhet and others), as well as torpedo-bombings, either because of duds, slow speed, AA defense and air defense. The dive bombers were harder to “kill” ad they had to come from higher up to dive, and were not easier to catch when diving or resourcing either. With just 8-9 bombs, these planes which were replaced one year afterwards, reversed the fate of the USN in the pacific.

Did Midway Battle was decisive ?

Most authors around the world, as well as Japanese themselves tend to see Midway as a decidive battle indeed, or as it is mentioned in history manuals, the “turning point of the Pacific” as was Stalingrad on the other side of the globe this crucial year. It was not “decisive” as meant by famous writer and naval thinker Alfred T Mahan in the sense the IJN was not destroyed this day. But that was a severe blow to the Imperial Japanese Navy in several ways, as we just saw, notably depleting a carrier fleet for further operations and causing a gap in experienced pilots (added to the losses of the Shokaku class) that will durably hamper efforts of the IJN to rebuilt a sizeable carrier force with experienced enough personal.

To be fair, as assessed later by authors, veteran losses represented 25% of the aircrew embarked on the four carriers, still not crippling with a total of 2,000 well-trained carrier pilots. This was more severe however for the 40% of the carriers’ highly trained aircraft mechanics and technicians, plus flight-deck crews and armorers, which were notably more experienced and efficient than USN carrier crews, in all but damage control.

In effect, this also allowed the USN to start operations of its own rather than just defending, with was also a momentous consequence on the strategic standpoint. Moreover, the southern Pacific was saved, Australia was saved, and this was the most important point to ensure a backup for future operations in the Pacific. If the battle would have turned otherwise and the three US carriers sunk instead, the Marines would have an almost impossible task of defending the rest of the South Pacific with just the USS Saratoga, probably kept as a guarantee to save Hawaii.

It is probable that Yamamoto would have resumed operations, starting with the invasion of Fiji and Samoa, capture and occupation of major cities of Australia, Alaska, and Ceylon with a possible further attack on Hawaii. The US Industry would not be able to complete a single new carrier until late 1942, November or December at the earnest, not counting training and trials, whereas several carriers were needed for a suitable task force anyway. This was leaving free hands to the Japanese for another six months at least, if not more, without any serious challenge but marauding US submarines. Parity was achieved after long months of combat as we known in the Carolines, battle fought and won or lost on both sides, and the tide would really turn by mid-1943.

So if Midway was decisive, it was for bringing this gush of fresh air to the US Navy, but it was certainly not sufficient in itself. It was a morale booster for the US public, but remained unknown for the Japanese public and despite archives has been opened recently, there is still some controversy among historians about it, mostly for some details. What really was decisive was the following “grinding match” around Guadalcanal and in the Solomon Campaign, notably the Battle of the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands which devoured at least as many pilots and crews than in Midway, a constant attrition of veterans that really took their toll on the Japanese and started the real downwards spiral.

One sure is absolutely certain though, all agrees on its very special character. The only other “decisive” battle of the Pacific compared to it was the Battle of Leyte, in 1944, which this time, claimed the best remaining part of the IJN.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign