Greek Navy vs

Greek Navy vs  Turkish Ottoman Navy

Turkish Ottoman Navy

The Battles of the Aegean sea, a prelude to the great war at sea

Eight years after Tsushima, and just before the Great war, Mediterranean naval powers clashed upon territorial and sovereignty questions. The Balkans separated from the Turkish Ottoman Empire, already in the XIXth century considered the “sick man of Europe”. There were two wars, one opposing the Greek and Turkish navy, while the other opposed the Regia Marina to the Turkish Navy. In 1912, both the battle of Elli and the battle of Lemnos showed speed was in itself a war-winning recipe.

At Elli, a single armored cruiser, using the relatively new “crossing the T” tactic pummelled the Turkish line and set the fleet packing. At Lemnos, the same story repeated, but this time the main battle line was engaged, showing that an excellent rate of fire (on the Turkish side) was no substitute for a good accuracy (on the Greek side). At the end, it also showed that naval reconnaissance was not superfluous, as shown by the perilous long-range mission of two Greek aviators to locate the Turkish fleet after the battle, and ensure the Greeks they had the mistery of the Aegean.

The Balkan Wars

The Balkan wars in 1912 has been seen by some authors as a template for ww1, at least in some aspects. There were indeed trenches, artillery concentration, air warfare and use of armored cars. The Balkan wars, also called by the Turks Balkan Faciası or “the Balkan Tragedy”, raged on between 8 October 1912 and 18 July 1913 mostly for the control of the Aegean sea, and the coastal areas of Eastern Greece and Western Asia minor, historical a region that has been Hellenized since ancient time. but it mostly happened as Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia took their independence from the Ottoman Empire and formed the Balkan League in 1912. Contrary to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the “sick man of Europe” never succeed in reforming itself and dealing with the rising ethnic nationalism.

Two Balkan Wars would emerge from this, since the league was certain to beat the Ottomans, provoked the eviction of ethnic Turks from these territories, and in the end delineated present-day Turkey’s western border. Needless to say, this psycho-traumatic event accelerated the fall of the Empire and the 1913 Ottoman coup d’état. It however already had been prepared by the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. This even saw Austria-Hungary annexing the Ottoman province of Bosnia-Herzegovina, raising tensions with Serbia. I any case, the Balkans were seen by major powers as a powder cake just waiting for a spark. It would just wait for one more year to explode. The balkan wars became in any case a traumatic event for the Turks, the great national tragedy.

Naval Operations

While independently from the Greeks, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro attacked Turkish positions in the theater of Sandjak, Macedonia and Thrace, and although the Turkish population was important, the issue of these land battles greatly depended from reinforcements from the homeland. So on the long-run, the fate of operations in the Balkans ultimately depended from the good will of the Greeks to intervene. The latter were too happy to oblige, also seeing an opportunity for some land grabbing in the Aegean. Naval battles between the Turkish and Greek navies in the Aegean would ensure this turn of event. The Ottoman fleet twice exited the Dardanelles to create a reinforcement convoy but was twice defeated by the Greek Navy, in the battles of Elli and Lemnos.

This Greek naval domination of the Aegean Sea prevented therefore any of these crucial reinforcements from the Middle East on any fronts and according to E.J. Erickson the Greek Navy indirect role by neutralizing a significant portion of the Ottoman Army in Thrace at the beginning of the war. Now free-handed, the Greek Navy could liberate Aegean Island. Balkans league officers were also not long to recognize the strategic value of this help to secure victory.

Before the battles: Fleets compared

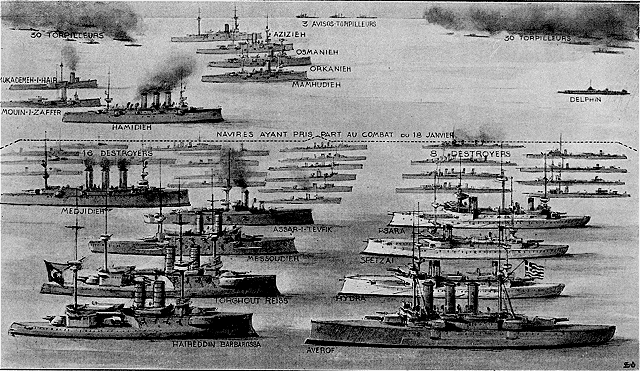

Diagram by French weekly L’Illustration, depicting the Greek and Ottoman fleets and the warships that participated in the Battle of Lemnos

The Asia minor coast, east of the Aegean and the islands themselves under nominal control by the Turks, lacked any facilities for a large fleet and at best only a few patrol boats were present in this sector. The bulk of the Turkish Ottoman fleet was indeed stationed at Constantinople, which only access to the Aegean was through the Dardanelles strait. This was a blessing and a curse, as its narrows and fortifications along the way protected the fleet from any incursion, but it also was a very ominous way off for the Turkish Navy and could be blockaded. That’s basically what the Greeks did. They just waited for the Turkish Navy to exit and came to them in force, thus preventing them to reach the West coast of Turkey and escort or carry reinforcements.

In 1912, the Turkish Ottoman Navy was still impressive on paper:

The consisted of two battleships, two cruisers, five destroyers (anchored in Beirut) while Izmir has been previously sunk by the Italian Navy.

The “Young Turks” tried in 1909 to change Turkey’s attitude towards its fleet, announcing an ambitious 6 years plan including 6 battleships, 12 destroyers, 12 torpedo boats and 6 submersibles. Its realization was delayed until the war broke out in 1911 with Italy, leaving the “old Turkish fleet” completely unprepared. In emergency, two German battleships and 4 destroyers were ordered from Germany and a host of steamers converted as gunboats. British counter-admirals William and Gamble from the Istanbul naval commission at the head of the fleet in 1910 had been instrumental in this decision.

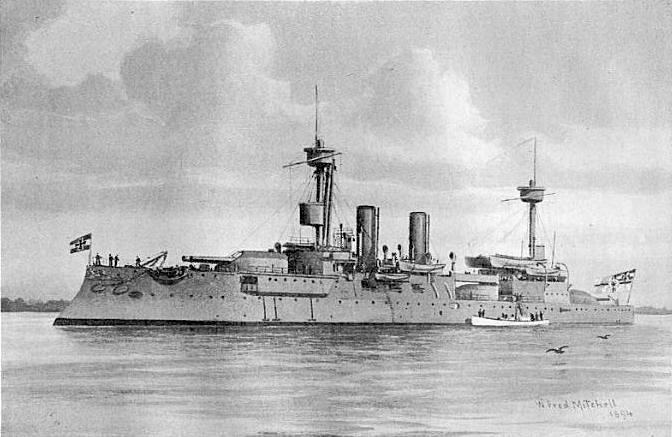

The Greek fleet on the other hand, was not so confident: In 1911, the admiralty was now also advised by British Royal Navy officers. The small navy was “saved” by the initiative of billionaire Giogios Averoff which purchased a ship in Italy, a powerful armoured cruiser loosely based on the Pisa class. She became de facto the Greek Navy flagship. But aside this, the Greeks were left with the three old Hydra class coast guard ships rearmed, 6 destroyers acquired, 2 submersibles and 6 torpedo boats started, while 9 freighters were converted into auxiliary cruisers. Greece lacked any battleship. Agreed, the two recently acquired from Germany were 1st generation Brandenbug class pre-dreadnoughts.

Start of the Operations

In 1912 the first operations by the Greek Navy was to secure several objectives. The capture of the Turkish-held port of Moudros was the first step. Located on the southern coast of the island of Lemnos, it was assaulted on October 8, 1912. The fleet landed Greek marines which progresses quickly in combination with close naval support. They defeated the unique Turkish garrison and occupation of the port followed suite. Moudros became the cornerstone of the Greek fleet for all naval operations in the sector, blocking the Dardanelles, and a launching pad to secure the Aegean islands of Psara, Imbros, Tenedos, Chios, Lesbos and Samothrace.

The Battle of Elli (1912)

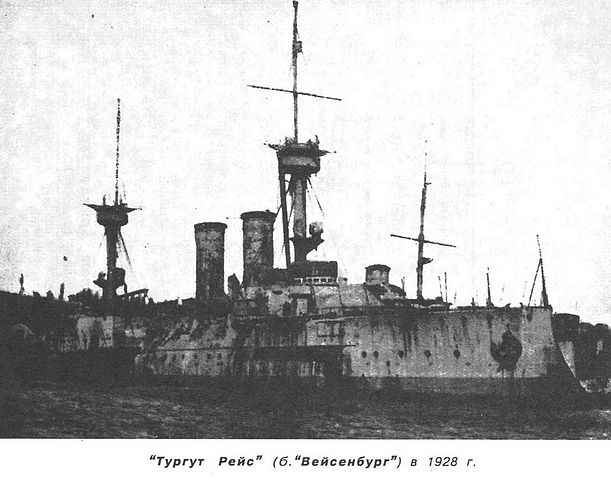

The Royal Hellenic Navy (Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis) onboard flagship Averof comprised in addition to the armoured cruiser the three coastal defence battleships Hydra, Spetsai and Psara and the four destroyers Aetos, Ierax, Panthir and Leon. Meanwhile, Captain Ramiz Bey commanded the Tukish fleet, the two battleships Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis, Mesudiye and Âsâr-ı Tevfik, the protected cruiser Mecidiye and four destroyers Muavenet-i Milliye, Yadigâr-i Millet, Taşoz and Basra.

He sailed just outside the entrance to the Dardanelles when spotting the fleet of Kountouriotis. The latter, frustrated by the poor speed of the coastal battleships hoisted the “Z flag” signalling “Independent Action”, raising his speed to 20 knots towards the Ottoman fleet. He soon closed the gap and placed his ship to cross the Ottoman’s “T”. He concentrated the Averoff’s fire against the lead ship, Hayreddin Barbarossa, which was badly hit, with 7 killed and 14 wounded, while soon the Turgut Reis was hit too (8 killed and 20 wounded) as well as the Mesudiye (3 dead and 7 wounded). The captain ordered to retreat, which was done in disorder. The Averoff tried to pursue them, but soon was distanced by the faster destroyers Aetos, Ierax and Panthir. The latter wen on skirmishing with the Ottoman flee rear-guard and stayed close to the formation from December 13 to December 26.

Turkish battleship Messudieh

The result of this victory was that the Ottoman navy retreated beyond the Straits and left the Aegean Sea to the Greeks. Soon the fleet proceeded to capture Lesbos, Chios, Lemnos and Samos. At the same time it allowed to free reinforcements by sea, which was crucial for the upcoming operations on land in the Balkans.

The Battle of Lemnos (1913)

After the losses of many Aegean Islands during the early phase of the 1912 war and defeat at the battle of Elli, the Ottoman Navy was pressured to act decisively and planned to destroy the Greek fleet anchored in the port of Mudros, on the island of Lemnos. They planned to send their fastest cruiser through Greek patrols, to shell islands in the hope hoping to draw a part of Greek ships including the Georgios Averoff in pursuit. Meanwhile the bulk of the fleet would fall on Mudros. The cruiser Hamidiye was chosen and set sail for the area, passing through the Dardanelles.

Greek preparations

At full speed by night on 13/14 January, she successfully evaded the Greek lookouts and sunk a transport ship at Syros at dawn, shelling the garrison and installations of the harbour. As the Turks planned, the Greek admiralty was ordered to depart with the telegraphic message “sail immediately in pursuit”. Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis however felt this was a possible Turkish rude and refused to obey. He prepared his fleet instead for the following phased against the bulk of the Ottoman Fleet. The Greek fleet’s pride, the 9,960 ton armored cruiser flagship Georgios Averof, already a victorious veteran of the 1912 campaign, was assisted by the three old ironclads Spetsai, Hydra and Psara, with the reinforcement of seven modern destroyers.

Turkish preparations

Meanwhile, behind the safety of the Dardanelles Straits, the Turkish admiralty tried to uplift the morale of the crews. As a symbolic gesture, the old, famous and original banner of the great corsair Hayreddin Barbarossa was raised on the flagship of the same name, greeted with cheers from the whole fleet. The Ottoman flotilla was led by Captain Ramiz Bey, hoisting his mark on the pre-dreadnought Hayreddin Barbarossa, assisted by her sister-ship Turgut Reis and the older Mesûdiye (a modernized ironclad), and the cruiser Mecidiye, plus five destroyers. The ironclad Âsâr-ı Tevfik remained in the Dardanelles as a backup defense in case the Greek would try to sneak in or surge in hot pursuit.

The battle

At 08:20 on January 5, Greek patrols spotted the Ottoman fleet and the signalled was received by the Greek Fleet of Mudros already prepared, all boilers hot and crews on board. Kontouriotis order the fleet to sail at 09:45 from Moudros Bay. The two fleets met off Mudros about 19.3 kilometers (12 miles) outh-east of the istald of Lemnos. Both were sailing southeast in converging columns. Both were led by their respective flagships. On paper, the Turks had the advantage both in firepower and protection. The gunnery exchange started at 11:34, under 8400 meters (9186 yards). The Greek column turned left and further closed the distance to allow its older ironclads to open a broadside fire.

The Mecidiye and destroyers turned northeast, heading back towards the Dardanelles. They were followed by the Mesûdiye which also turned at 11:50. She has been badly hit by both the Hydra and Psara. Five minutes later, the Georgios Averof had some lucky hits on the lead ship Barbaros Hayreddin. The central axial turret was blow off. Her captain decided to withdraw towards the Dardanelles too, quickly followed by the Turgut Reis five minutes later. Soon during the battle the Georgios Averof broke off and signalled “independent action”, and sped up while maneuvering to engage the Turks with her artillery on both sides; Later she chased the retreating Ottoman ships, followed by the rest of the fleet. The chase stopped at 14:30, as the Ottoman Navy closed under the artillery umbrella of the Dardanelles.

Lessons from the battle

After the reports, it was shown the Ottoman ships had an excellent rate of fire, and spent around 800 shells. However accuracy was quite poor. During the whole engagement, Georgios Averof took only two hits for one injury and light damages. She was the only one which suffered. Barbaros Hayreddin on her side was more than twenty times, her artillery and direction was disabled while she suffered 32 dead and 45 wounded. Turgut Reis took a hit in the lower oart of the hull, creating a leaking, and 17 other hits on the superstructure, but suffered less damage. She deplored 9 dead and 49 wounded. Mesûdiye was also hit several times, and a 270mm shell destroyed the central 150mm gun platform which explosed and caused 68 casualties.

The battle forced the Ottoman Navy to retreat beyond the Dardanelles for good, never attempting another sortie, giving free hands to the Greek Navy in the Aegean Sea. To ensure this, 1st Lieutenant Michael Moutoussis and Ensign Aristeidis Moraitinis on January 24, 1913 flew with their Maurice Farman hydroplane over the Nagara naval base. Not only their reported the position of all ships, but also dropped four bombs. Their 40 minutes observation round ended a 140 minutes trip over 180 kilometers (111.8 miles). Both aviators became instant heroes in the Greek and international press.

After the war – epilogue

The Greeks launched an ambitious program, ordering at the Vulkan shipyards a single 20,000-ton dreadnought to be named Salamis, and two 2 other battleships in options which ultimately would be puchased in the US. Also the Averoff left such impression that two sister-ships were started but the armistice of May 1913 put an end to these developments. The head of the British Naval Mission, Sir Mark Kerr, defined a new plan calling for 3 light cruisers, 34 destroyers, 20 submersibles, 2 airships and 12 seaplanes plus support ships. However, new naval Turkish ambitions led to the purchase of the Rio then in constructions for Brazil plus two more 23,000 ton dreadnoughts, 1 cruiser, 4 destroyers and a submarine, which never materialized as the great war broke out.

A Parallel: Italian Naval Operations

Between January and August 1912, the Regia Marina was deployed against the Turks, focusing on the middle east and red sea. Needless to say the Italians enjoyed a clear advantage, with seven times the tonnage of the Ottoman navy and had a better training. The first act was the Battle of Kunfuda Bay where seven Turkish gunboats (Ayintab, Bafra, Gökcedag, Kastamonu, Muha, Ordu and Refahiye) and a yacht (Sipka) were sunk and the Red Sea ports were blockaded in order to support the Emirate of Asir rebellion.

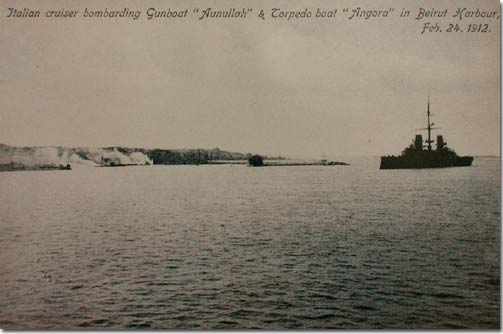

The battle of Beirut

On 24 February in the Battle of Beirut, an Ottoman casemate corvette and six steamers and a torpedo boat were either sunk of force to flee. in both engagements, the Italians suffered no hit nor casualties. The goal was then to secure the Suez Canal. The Ottoman naval presence at Beirut was completely annihilated and casualties on the Ottoman side were heavy.

Complete naval dominance of the southern Mediterranean was achieved and later the Italian fleet shelled ports of the North African coast and gradually secured the 2,000 km of the Libyan coast in April-August 1912. However landings penetrations were limited to the umbrella of the naval artillery. In the summer, the Italians turned to the Aegean Sea in coordination with the Greeks, and occupied twelve islands, including Rhodes, although infuriating Austria-Hungary in the process and the last action was a combined attack of TBs in the Dardanelles in July. Nothing could really be gained of these engagements which were each time one-side, but that training was each time a major advantage.

Read More/ see also:

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1860-1906

On www.usni.org proceedings archives the battle of helles and lemnos

on ageofsteelandcoal

On thomo.coldie.net

The Balkan Wars

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

This article needs some improvements. The Balkan Wars would not have happened were it not for the Young Turk rebellion. Pretty soon, especially after the 1908 elections that were rigged by the regime in a way that the Turks would be the majority of parliament even though they were the minority in the Empire and the failed 1909 counter coup after which the liberals that were never many to begin with were sidelined, it became obvious that the regime was up to no good in regards to its Christian subjects. In the 1911 Committee of Union and Progress it was declared: “Turkey must become a Muslim country, where the Muslim religion and Muslim culture will dominate any other religious propaganda stifled. Sooner or later we must complete full ottomanization of all peoples of Turkey, and it is very obvious that this can not be accomplished by persuasion. Thus we will use armed violence. The right of other nationalities have their own organizations should be denied. Any form of decentralization and self-government will be considered treason to the Turkish Empire”. The Balkan League formed in reaction to this, rather than each Christian country fight each other over the spoils of the whole Ottoman Empire, each would keep whatever they liberated. The expulsion of the Turks was not the original plan, at least of Greece. It mostly took place after the Lausanne Treaty in 1923 as part of the population exchange.

Georgios Averoff had died in 1899 and left money to the Royal Hellenic Navy to buy a training ship. Because of the construction of the HMS Dreadnought the Pisa class armored cruisers had become obsolete which is why Italy was looking to offload them. With the permission of Averoff’s inheritors the money was given as a down payment for the ship and the rest was paid with a French loan, which took some wrangling to get.

The Ottoman islands of the Aegean per the 1909 census had a population that was over 90% Greek. Most had rebelled in the past to join Greece in 1821, and several even later, such as Samos and Crete.

Turkish plans for defense of the Balkans was that an Army from Syria would be shipped to Europe to fight. Without a fleet that was impossible because the Railroads of the Orient lacked steam engines. In the end they did manage to bring sufficient army to stop the Bulgarians at Çatalca but the Bulgarians bottle them there. Another army was raised in the Balkans instead of the Syrian army, but proved problematic. Without the Greek fleet Greece would have never been invited to the Balkan Alliance especially considering the humiliating defeat of the 1897 war. Until Sarandaporo the Balkan Allies were worried the Greek Army might collapse under Turkish attack.

When Imbros was liberated Admiral Kountouriotis actually sent a telegram to Turkish Admiralty in Constantinople “We are awaiting you at the exit of the straights for battle. If you lack coal to move your fleet we will send you”. However the Turkish telegraph operator realized what was about to be sent and cut the line without sending it. The self bottling of the Ottoman fleet at Nagaras was not expected, but it certainly helped and drove Greek morale up and Turkish morale low. The Ottoman government fired the previous admiral and promoted Ramiz Bey when it became obvious his predecessor had no intention of taking out the fleet.

The Greek invasion of Mytilene had actually taken place on November 7. The dates you give for the liberation of the major islands of the North Aegean are the surrender dates of the Ottoman garrisons, not the invasion dates. After the battle of Elli the Ottoman garrisons surrender seeing no reinforcements were to come.

In the battle of Lemnos the Ottoman fleet also had the advantage of having the sun behind them, at an era where only optical means of targeting were available. The Greeks were firing into the sun, a problem the Ottomans did not have.

Accuracy for the battleship Averoff at the Battle of Elli was around 60% and at Lemnos where the distance was longer around 30%. I do not have the numbers on top of my head but you can find them at the official history published by the Hellenic Navy General Staff

Thanks for these points Ioannis !