Royal Navy Broadside Ironclads built 1861–1864, service until 1956

Royal Navy Broadside Ironclads built 1861–1864, service until 1956

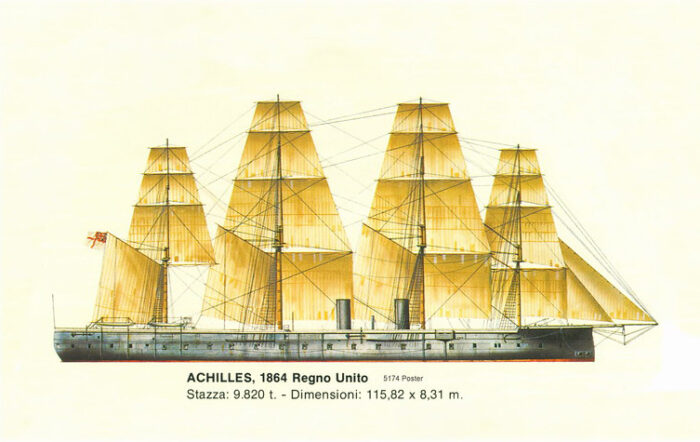

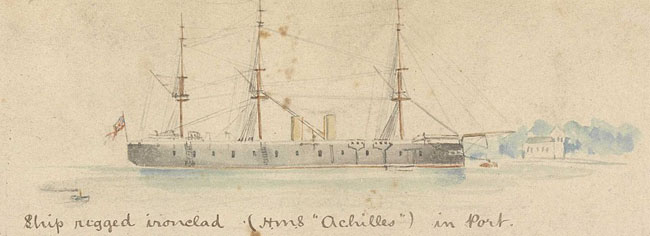

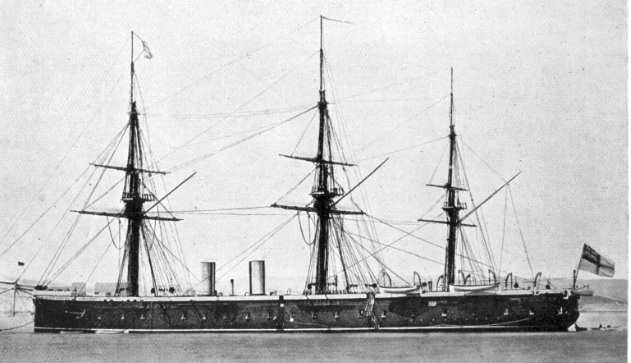

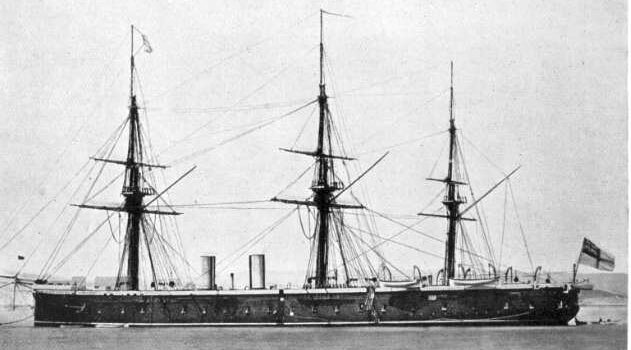

HMS Achilles was an armoured frigate built at Chatham, designed by Oliver Lang and completed in 1864, assigned to the Channel Fleet. At nearly 10,000 tonnes, she was none of the largest warships afloat. She was also the one that had the most changes, in appearance and names in the RN, until her demolition. In 1868, she was refitted and re-armed, became a guard ship of the Fleet Reserve (Portland District) until 1874 and was refitted and re-armed again in 1874, now a guard ship at the Liverpool District, in the Channel Fleet in 1877, and in the Mediterranean in 1878. She was back to the Channel Fleet from 1880 to 1885, paid off but recommissioned in 1901 as a depot ship at Malta (new names) but back at Chatham in 1914, used as such until sold for scrap in 1923.

Design of the class

Achilles was the 3rd ironclad planned in the 1861 Naval Programme. She was designed as an improved Warrior-class armoured frigate, featuring a complete waterline armour belt and a more modern armament, as designed by Oliver Lang. One new aspect compared to the Warriors was that she was slightly smaller, cheaper, and had a straight stem and ram.

Hull and general design

HMS Achilles measured 380 feet 2 inches (115.9 m) long between perpendiculars, for a beam of 58 feet 3 inches (17.8 m) and draft of 27 feet 2 inches (8.3 m), all for a displacement of 9,820 long tons (9,980 t) and tonnage of 6,121 bm (Builder’s Old Measurement or “burthen”). The hull was subdivided underwater, with a series of watertight transverse bulkheads, themselves subdivided in longitudinal compartments making a total of 106 compartments, most filled with coal. She also had a double bottom over all her length. HMS Achilles presented a high centre of gravity however and proved later very stiff at sea. Meaning she rolled little, but abruptly. In a storm she rolled 10 degrees so suddently the shock ripped the main and mizen topgallant masts off, and she lost her topsails. As the Warrior class, she was very long and not very manoeuvrable either.

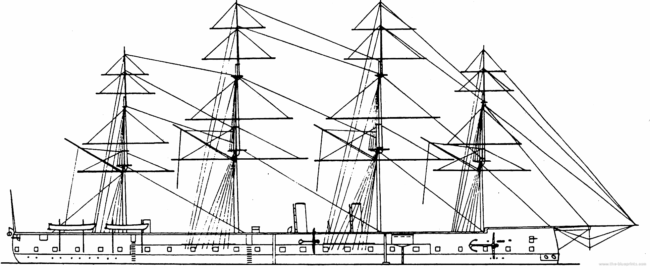

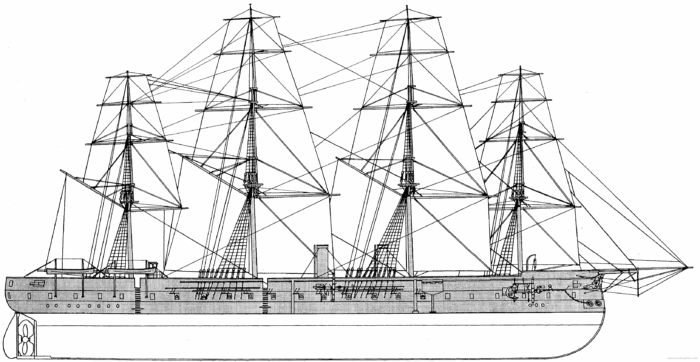

In addition, her hull was a slab-sided mass with short entries at the bow and with a moderate clipper stern, further contributed to this lack of agility. She bled a lot of speed when full steam ahead, hard over. Her appearance was peculiar, as she started service also with four masts. She had a helmsman/flying bridge position at the base of the second mizzenmast mast and high bulwarks. A second one, smaller, was located just in front of the two sponsoned towers (see below). The hull ended with a forecastle for seakeeping. Her ram was peculiar as it made a bulge forward with the down slope starting above the waterline. She also had two small armoured sponsons for observation on either side above the battery deck, behind bulwarks, abaft the mizzenmast. She had a crew of 709 officers and ratings and around ten boats, including four under davits aft. She had her main capstan located between the second mainmast and second funnel, and her funnels were raked.

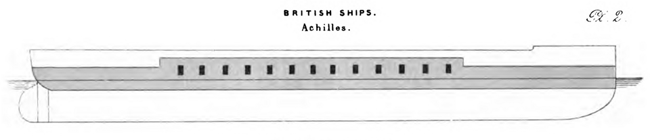

Hull form, Greenwhich coll.

Powerplant

HMS Achilles had a single two-cylinder trunk steam engine. It came from John Penn and Sons. It drove a single 24-foot (7.3 m) span two-bladed propeller, none retractable, aft. The rudder was a classic half-leaf shape directly anchored and hinged below the waterline end of the clipper stern poop. This large engine was fed by ten rectangular boilers, providing steam at a working pressure of 25 psi (172 kPa; 2 kgf/cm2). In sea trials, performed on 15 March 1865, she reached at full speed a measured 14.32 knots (26.52 km/h; 16.48 mph), with 5,722 indicated horsepower (4,267 kW). Her coal capacity, thanks to all her compartments, started at 750 long tons (760 t), enough to steam 1,800 nautical miles (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) at 6.5 knots (12.0 km/h; 7.5 mph), but in wartime it could be pushed further.

HMS Achilles being in this transition phase when steam engine were still relatively weak, coal-hungry and sometimes unreliable, saw her ship-rigged. But unlike the Warrior class, which were “classic” up-scaled steam frigates essentially, she was the first to receive four masts. They were called bow, fore, main and mizzen, from fore to aft. This was a first and remained the only one in that configuration until the Minotaur class came along with their five masts. This was due to her great length and the way the masts were built and structure at the time. The wind force was most severe at higher heights. Still, this combination provided a generous figure of 44,000 square feet (4,088 m2) in area, excluding the stunsails. At the time, it was the greatest area of sail ever on a British warship, larger than the largest steam 4-decker warships such as HMS Wellington.

However this arrangement proved unsatisfactory when the wind was before the beam. In June 1865 already, her bowsprit and bow mast were removed to cure this problem out. But this caused her in turn to have a too much weather helm, and the bowsprit was replaced, the foremast moved forward 25 feet (7.6 m) about a year later by July 1866. This reduced sail down to 30,133 square feet (2,799 m2) but was now a more manageable lot. In 1877, Achilles was rigged again as a barque, the rigging was decreased and simplified. It should be noted that her funnels were retractable to reduce wind resistance while under sail.

Protection

Brasseys 1887

HMS Achilles had a wrought-iron waterline armour belt. It ran over her full length. It should be noted that given her size she was, like the Warrior class, entirely iron-made, with some wooden backing however behind the armour.

Amidships, the armoured battery ws 4.5 inches (114 mm) thick over 212 feet (64.6 m). It tapered down to 2.5 inches (64 mm) to both ends.

This armour extended 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m) below the waterline.

The main deck had a strake of armour 4.5-inch thick over 212 feet (64 m) long.

To protect against raking fire, the upper strake ended with a 4.5-inch (114 mm) transverse bulkheads, at each end, creating a citadel.

Armament

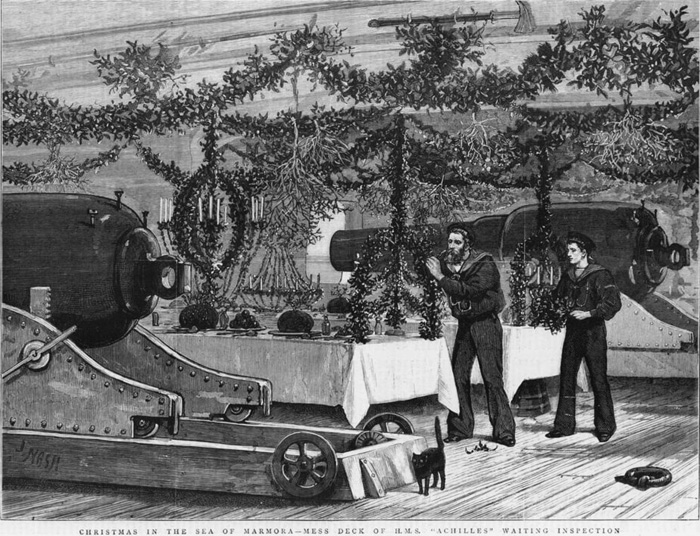

Battery guns being prepared for Xmas 1878-79 in the sea or Marmora.

Apart changes in her rigging, and in names, her armament was the most changed one. Most will be described in detail in her uneventful career.

Originally, she carried a classic battery loking like the one of HMS Warrior, so a combination of Smoothbore muzzle-loading 68-pounder guns, Rifled breechloading 110-pounder guns and Rifled breechloading 40-pounder guns. But it was amended and changed five times before the one was finally mounted.

When completed she had the following:

-Four rifled 110-pdr breech-loading (BLR) guns on the upper deck, two as chase guns, bow and stern

-Sixteen smoothbore, muzzle-loading (SML) 100-pdr Somerset cannon: Eight on either side, main battery deck.

-The breech-loading guns were a new design from Armstrong and great hopes were planced in them to defeat the wrought armor of that time, when armour usually defeated cannons.

Firing tests in September 1861 proved that these 110-pounder were even inferior to the 68-pounder smoothbore guns in armour penetration. Better accuracy but poorer muzzle velocity caused this. There were in addition repeated incidents of breech explosions reported from the Battles for Shimonoseki and Bombardment of Kagoshima in the Boshin war of 1863–1864. The RN withdrew these from service. So bt 1865, six 68-pounder smoothbores were added, three on each side on the battery deck, before the 1868 rearmament.

The 68 Pdr Somerset had no data available, but their 7.9-inch (201 mm) solid shots weighted 68 pounds (30.8 kg), hence their name. The guns weighed 10,640 pounds (4,826 kg) for a muzzle velocity of 1,579 ft/s (481 m/s) and range of 3,200 yards (2,900 m) for an elevation of 12°.

The 7-inch (178 mm) shells for the 110-pounder Armstrong breech-loader weighed 107–110 pounds (48.5–49.9 kg) for a muzzle velocity of 1,150 ft/s (350 m/s) and range of 4,000 yards (3,700 m) at 11.25° elevation. These guns weighed 9,520 pounds (4,318 kg). They could fire eigher solid shot and explosive shells.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 9,820 long tons (9,980 t) |

| Dimensions | 380 x 58 ft 3 in x 27 ft 2 in (115.8 x 17.8 x 8.3 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft, 1 trunk steam engine, 10 boilers: 5,720 ihp (4,270 kW) |

| Sail plan | 4 masts-rig |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Range | 1,800 nmi (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) at 6.5 knots (12.0 km/h; 7.5 mph) |

| Armament | 4 × 7-in (178 mm) Armstrong BLR, 16 × 100-pdr (234 mm) Somerset SB, 6 × 68-pdr SB |

| Protection | Belt 2.5–4.5 in (64–114 mm), Bulkheads 4.5 in (114 mm) |

| Crew | 709 |

Career of HMS Achilles

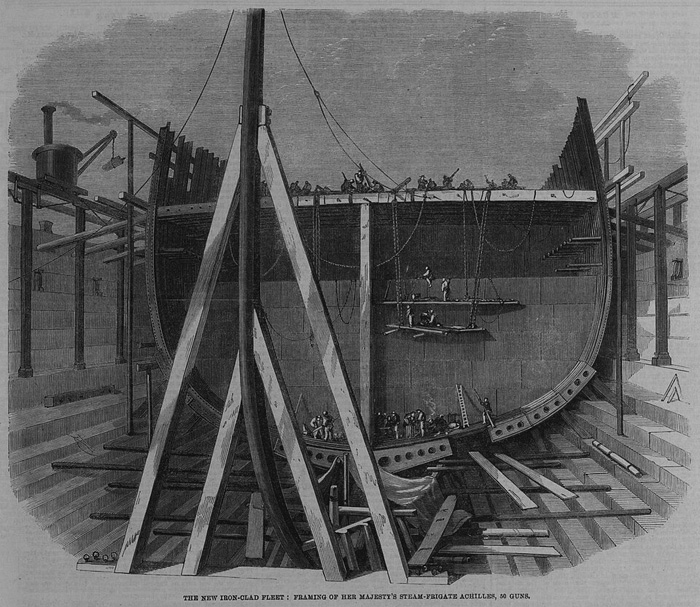

Achilles was of course named after the Greek mythological hero, perfectly in line with the Victorian neo-classical craze, and only fitting name after the Warrior class and a completment to the Hector class, a more austere take on the Ironclad type. She was ordered on 10 April 1861 from Chatham Dockyard and first iron-hulled warship built at a royal dockyard. But her construction was delayed deu to the delivery of a machinery to handle iron and to have skilled workers to work on it. She was eventually was laid down on 1 August 1861 on a new, large drydock, floated out rather than traditionally launched given her enormous size, on 23 December 1863. She was eventally completed on 26 November 1864 at a cost of £469,572. After sea trials and working out, then manoeuvers, she joined the Channel Fleet until 1868. But soon many issues appeared with her general seakeeping, rolling, agility, sail, and armament.

Achilles was rebuilt, starting with a rearmament in 1867–68, with twenty-two 7-inch and eight 8-inch (203 mm) rifled muzzle-loading guns. The 8-inch guns and eighteen of the 7-inch guns were mounted on the main battery deck. The remaining 7-inch guns replaced the 110-pdr on the upper deck, covering the chase and retreat.

The 15-cal. 8-inch shells weighed 175 pounds (79.4 kg) over 9 long tons (9.1 t). It had a muzzle velocity of 1,410 ft/s (430 m/s) and could this time penetrate 9.6 inches (244 mm) of wrought iron armour at short range. The 16-cal. 7-inch guns weighed 6.5 long tons (6.6 t), fired a 112 pounds (50.8 kg) shell capable of penetrating 7.7-inch (196 mm) armour.

The masts were relocated and reduced to three, and other changes were made.

Achilles became the guardship at Portland until 1874 when she was again re-armed: She now obtained sixteen 9-inch rifled muzzle-loaders, replacing the four 8-inch and twenty of the twenty-two 7-inch guns. Fourteen of the 9-inch (229 mm) guns were mounted on the main battery deck, the other two replaced the two 7-inch chase guns. Two more 7-inch guns stayed in their position on the quarterdeck. These new 9-inch guns much larger and heavier, so the needed new, larger gun ports. Their shell, for 14-calibre, weighed 254 pounds (115.2 kg) and the guns weighted 12 long tons (12 t) each. Muzzle velocity of 1,420 ft/s (430 m/s) so to be able to penetrate up to 11.3 inches (287 mm) of wrought iron armour at short range. This pretty much defeated any ironclad at the time. The masts were altered again as well, with a barque rigging.

After completion of this new refit in 1875, HMS Achilles became guardship at Liverpool, until 1877. Captain William Hewett assumed command and in 1878 she was pressed into the “Particular Service Squadron” under Admiral Geoffrey Hornby. She sailed for the Dardanelles at the time of the first “Russian war scare” of June–August 1878, part of the Russo-Turkish War. Achilles accidentally collided with the Mediterranean Fleet flagship HMS Alexandra on 4 October 1879 but damage was only on Alexandra’s propeller. When the situation deflated in the Dardanelles she was sent back home, to the the Channel Fleet in 1880. After five more uneventful years she was paid off in 1885.

In 1889 she was rearmed a last time. She only had two 6-inch (152 mm) 5 ton breech-loaders, fourteen 9-inch (229 mm) 12 ton muzzle-loading rifles left, all obsolete apart for shore bombardment. She however had six landing (boat and field) guns for landing parties, complements by an anti-torpedo boat armament of eight QF 3-pounder (47 mm) guns and no less than sixteen machine guns.

Afterwards she was essentially mothballed and not maintained, to the point of being derelict in the Hamoaze, that is until April 1901. She was then refusrbished, and sent to Malta as a depot ship. Neither the composition of her armement or rigging is known. afterwards.

Her name was changed to HMS Hibernia in 1902, then Egmont in March 1904 while she was posted at Malta until 1914. When she was replaced by the stone frigate Fort St Angelo she was towed back Chatham and used as a depot ship as “Egremont” from 19 June 1916, “Pembroke” from 6 June 1919, until sold for scrap on 26 January 1923, sent to the Granton Shipbreaking Co.

Read More/Src

Construction: Framing of Achilles in 1862. Note the scale of the hull compared to workers.

Books

Ballard, G. A., Admiral (1980). The Black Battlefleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.-3.

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press.

Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Jones, Colin (1996). “Entente Cordiale, 1865”. In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Lambert, Andrew (1987). Warrior: Restoring the World’s First Ironclad. London: Conway.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Brassey, T.A., ed. (1890). The Naval Annual 1890. Portsmouth: J. Griffin and Co.

Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Achilles_(1863)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:HMS_Achilles_(ship,_1863)

https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-66902

Model Kits

None found

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign